Justin Taylor's Blog, page 59

January 21, 2016

Why Reconstructing the Past Is So Hard to Do

Columbia University professor Andrew Delbanco:

If we try to approach history, in R. G. Collingwood’s phrase, by discovering “the outside of events,” we shall never grasp something as elusive as the shape of hope or dread. We shall never get hold of mental states by making inventories of numerable things.

It is possible to chart the acceleration of locomotion and communications since the industrial age, the growing percentage of households with indoor plumbing and central heating since the Second World War, the hump in life expectancy since the discovery of antibiotics.

But it is equally possible to graph rising rates of illegitimacy, divorce, juvenile crime, and the expanding disparity between the incomes of rich and poor.

Such taunting symmetries are what Norman Mailer had in mind when he remarked that the problem in understanding even the recent past is that “history is interior.” Getting at the interior thought of a friend, or a spouse, or one’s own child is hard enough; trying to catch the mood of strangers in the present, even with the help of pollsters, is harder. But retrieving something as fragile and fleeting as thought or feeling from the past is like trying to seize a bubble.

One reason it is hard is that most of the voices still audible to us come from a tiny minority who left written accounts of their experience; and the relation is often mysterious between these few and the many more whom time has rendered silent. . . . .

In the face of such obscurities, the best we can usually manage is to take the scraps left by witnesses and try to assemble them, as if they were fossil fragments, into a reconstructed skeleton. The result will always be incomplete, and we can only guess at the missing parts.

—Andrew Delbanco, The Real American Dream: A Meditation on Hope (Cambridge, Mass./London: Harvard University Press, 1999), 6-8.

January 19, 2016

“Donald Trump Is Not Capable of Serious Moral Reasoning”

John McCormack of The Weekly Standard:

When Ben Carson was rising in the polls, Donald Trump was quick to attack the former neurosurgeon for being “pro-abortion not so long ago.”

The attack was more than a bit hypocritical because Trump himself was “very” pro-abortion not so long ago. In 1999, Tim Russert asked Trump if he would support a ban on “abortion in the third-trimester” or “partial-birth abortion.”

“No,” Trump replied. “I am pro-choice in every respect.” Trump explained his views may be the result of his “New York background.” Now that Ted Cruz has attacked Trump’s “New York values,” Trump’s views on abortion will be getting a second look by many Republican voters.

During the first Republican presidential debate, Trump explained that he “evolved” on the issue at some unknown point in the last 16 years. “Friends of mine years ago were going to have a child, and it was going to be aborted. And it wasn’t aborted. And that child today is a total superstar, a great, great child. And I saw that. And I saw other instances,” Trump said. “I am very, very proud to say that I am pro-life.”

When the Daily Caller‘s Jamie Weinstein asked Trump if he would have become pro-life if that child had been a loser instead of a “total superstar,” Trump replied: “Probably not, but I’ve never thought of it. I would say no, but in this case it was an easy one because he’s such an outstanding person.”

That Trump could go from supporting third-trimester abortion–something indistinguishable from infanticide, something that only 14 percent of Americans think should be legal–to becoming pro-life because of that one experience is a bit hard to believe. If it’s true, the story still indicates at the very least that Trump is not capable of serious moral reasoning.

You can read the whole thing here.

January 15, 2016

What’s Going on at Wheaton? A Modest Proposal for the “Do Christians and Muslims Worship the Same God” Debate

As many readers will know by know, Wheaton College is embroiled in a public controversy over comments made by Larycia Hawkins, the first female African-American tenured professor at Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois.

What’s Going On?

If you need to catch up on the discussion, Joe Carter has a handy “explainer” where he answers the following questions:

What is the Wheaton “same God” controversy about?

Was Hawkins put on leave because she wore a hijab?

How did Hawkins respond to the questions?

What was Wheaton’s response to Hawkins’s letter?

Does this mean that Hawkins has been fired?

How has Hawkins responded to the Notice of Termination?

Mistakes to Avoid

I think there are several mistakes to avoid in trying to process and comment upon this situation.

1. Assuming that we have all the information.

We only have the information that Wheaton has chosen to make public and that Professor Hawkins has chosen to make public. Anyone involved in leading an organization or school likely knows that there is more going on behind the scenes than can be made public, and therefore it is difficult to take limited information and try to form a full and fair judgment.

2. Assuming that this is about one issue.

Many people assume this is merely about one thing, whereas it seems likely that it’s a constellation of complicated and competing factors. Mark Galli of Christianity Today did a nice job of identifying at least some of them:

The theological integrity of a Christian institution

Loving our Muslim neighbors

Academic freedom

Maintaining boundaries

Diversity on Christian campuses

Tenure

Confidentiality

The right to know

So What about the Statement on Muslims and Christians Worshipping the Same God?

I think this remains one of the best opening questions for the discussion:

Discussion of the Q: "Do Christians & Muslims worship the same God?" must begin w/ definitions of "worship," "God," & "Christian." #Wheaton

— Travis Myers (@travismyers71) December 17, 2015

There is a sense in which the answer to this question could be answered in the affirmative and a sense in which it should (in my view) be answered in the negative. (Professor Hawkins has said as much herself.) The problem is that it’s a terribly ambiguous statement, such that two people can affirm it and mean very different things by it.

Catholic philosopher Francis Beckwith provides a list of philosophers and theologians who answer the question in the affirmative:

Edward Feser

Fr. Al Kimel

Dale Tuggy

Miroslav Volf

Michael Rae

Kelly James Clark

John G. Stackhouse

And a list of those who answer it in the negative:

Andrew T. Walker

Albert Mohler, Jr.

Lydia McGrew

Matthew Cochran

Richard B. Davis

Nadeel Qureshi

Kevin Bywater

Scot McKnight

As well as those who offer more of a complicated yes-and-no answer:

Bill Vallicella (with follow-up posts here and here)

Peter J. Leithart (with a follow-up post)

Roger Olson

One defeater offered to the denial that Christians and Muslims worship the same God is that Jews do not hold to a Trinitarian view of God either, and therefore this position seems to entail a denial that Jews worship the one true God or that Christians worship the God of Abraham and Israel. Yale theologian Miroslav Volf has advanced this argument forcefully, arguing that Christians who fall prey to this line of reasoning are being heretical.

The best piece I know of in response to this line of argument is the new piece at TGC today by Lydia McGrew, a homeschooling mother and an analytical philosopher. She writes:

In one sense Christians and modern religious Jews worship the same God; in another sense they don’t.

Old Testament Jews, of course, didn’t reject the Trinity and the incarnation, since those doctrines hadn’t been revealed. If one emphatically rejects these truths about God, however, and explicitly worships God as non-triune and non-incarnate, then this makes a pretty good case that, in one sense, such a person does not worship the same God whom Christians worship.

In another sense, however, Christians can say to modern religious Jews:

The true God who called your forefathers out of the land of Egypt, who gave the law at Sinai, who chose you as his beloved, chosen people, really is the one who sent Yeshua the Messiah to die for our sins. We worship the God who really did found Judaism thousands of years ago, who really did give the Torah. And we are here to tell you more about him.

In this historical sense we can say the God we worship is the God of the Jews, though those who haven’t accepted Jesus don’t (of course) agree. But notice: Nothing like this is true of Islam. God didn’t really reveal himself to Mohammad. Mohammad was not a prophet of God. It isn’t enough that Muslims think the Being who revealed himself to Abraham also spoke to Mohammad. Truth matters, and since that isn’t true, there is no real historical connection—in the acts of God himself—between the Allah of Islam and the one true God. But there is a real historical connection in the acts of God between Judaism and Christianity.

I encourage you to read her whole piece, where she addresses a number of other objections as well.

A Modest Proposal for Both Sides: Can We Agree on This?

Much of this discussion has been in the language of philosophy rather than of exegetical theology.

Here is my proposal: Can we agree that the answer to whether or not Christians and Muslims “worship the same God” has a yes-and-no answer, depending on the meaning, but that Jesus taught that the following is true of all people, whether professing Jews, Christians, or Muslims?

1. If professing Jews, Christians, and Muslims do not honor God the Son, then they do not honor God the Father.

“Whoever does not honor the Son does not honor the Father who sent him.” (John 5:23)

2. If professing Jews, Christians, and Muslims do not receive God the Son, then they do not have the love of God the Father within them.

“I know that you do not have the love of God within you. I have come in my Father’s name, and you do not receive me.” (John 5:42-43)

3. If Jews, Christians, and Muslims do not know God the Son, then they do not know God the Father.

“You know neither me nor my Father. If you knew me, you would know my Father also.” (John 8:19; cf. John 7:28; 14:7)

4. If professing Jews, Christians, and Muslims deny God the Son, then they deny the God the Father.

“No one who denies the Son has the Father. Whoever confesses the Son has the Father also.” (1 John 2:23)

5. If professing Jews, Christians, and Muslims do not come to God the Son, then they have not heard and learned from God the Father.

“Everyone who has heard and learned from the Father comes to me.” (John 6:45)

6. If professing Jews, Christians, and Muslims reject God the Son, then they reject God the Father.

“The one who rejects me rejects him who sent me.” (Luke 10:16)

The virtue of this line of reasoning, it seems to me, is it forces us to reckon with the biblical text where Jesus addressed what we must believe and what we cannot reject.

So if you want to say “Muslims worship the same God as Christians” and you can affirm that “Muslims do not know and honor but rather deny and reject the one true God of Christianity”—then I think we are on the same page (though I also think the former statement will be very confusing to many people).

January 14, 2016

The End of a Remarkable Writing and Speaking Ministry: An Update on J. I. Packer’s Health

We at Crossway learned this week that J. I. Packer (who will, Lord willing, turn 90 years old in July 2016) has developed macular degeneration in his right eye. His left eye has had macular degeneration for over a decade. He consented to let this information be shared publicly.

Age-Related Macular Degeneration is the leading cause of vision loss for those over the age of 65. The macula is a small spot near the center of the retina that helps to focus on objects straight ahead. Degeneration of the macula does not in itself lead to total blindness, but it can make it nearly impossible to read, write, or even recognize faces.

The disease struck Dr. Packer’s right eye over Christmas, which means (at time of writing) he has only been living with this for the past few weeks. He is unable to read, and therefore he will be unable to travel and speak. Because so much of his writing involves initial working with a ballpoint pen and blank paper, he is also unable to write.

You can read Ivan Mesa’s TGC interview with Dr. Packer today on his perspective on these developments.

Two of his final books have had resonance with the challenges he is currently facing: Weakness Is the Way: Life with Christ Our Strength (Crossway, 2013) and Finishing Our Course with Joy: Guidance from God for Engaging with Our Aging (Crossway, 2014).

In the latter volume, he explained the difference between a worldly and a biblical view of aging:

How should we view the onset of old age? The common assumption is that it is mainly a process of loss, whereby strength is drained from both mind and body and the capacity to look forward and move forward in life’s various departments is reduced to nothing. . . .

But here the Bible breaks in, highlighting the further thought that spiritual ripeness is worth far more than material wealth in any form, and that spiritual ripeness should continue to increase as one gets older.

The Bible’s view is that aging, under God and by grace, will bring wisdom, that is, an enlarged capacity for discerning, choosing, and encouraging. In Proverbs 1-7 an evidently elderly father teaches realistic moral and spiritual wisdom to his adult but immature son. In Psalm 71 an elderly preacher who has given the best years of his life to teaching the truth about God in the face of much opposition prays as follows:

You, O LORD, are my hope,

my trust, O LORD, from my youth. . . .

Do not cast me off in the time of old age;

forsake me not when my strength is spent. . . .

But I will hope continually

and will praise you yet more and more.

My mouth will tell of your righteous acts,

of your deeds of salvation all the day,

for their number is past my knowledge.

With the mighty deeds of the Lord GOD I will come;

I will remind them of your righteousness, yours alone.

O God, from my youth you have taught me,

and I still proclaim your wondrous deeds.

So even to old age and gray hairs, O God, do not forsake me,

until I proclaim your might to another generation,

your power to all those to come. (Ps. 71:5, 9, 14-18)

And Psalm 92:12 and 14 declare:

The righteous flourish like the palm tree and grow like a cedar in Lebanon. . . .

They still bear fruit in old age;

they are ever full of sap and green.

This biblical expectation and, indeed, promise of ripeness growing and service of others continuing as we age with God is the substance of the last-lap image of our closing years, in which we finish our course. Runners in a distance race, like jockeys in a horse race, always try to keep something in reserve for a final sprint. And my contention is going to be that, so far as our bodily health allows, we should aim to be found running the last lap of the race of our Christian life, as we would say, flat out. The final sprint, so I urge, should be a sprint indeed.

I thank God tonight that James Innell Packer’s course is not yet finished and that he is still running the race. In accordance with this counsel, I pray it will be a spiritual sprint through the finish line.

J. I. Packer on Three Types of Evangelicals Today—And What the Puritans Can Teach Each Group

The following piece of brilliant analysis is from J. I. Packer, A Quest for Godliness: The Puritan Vision of the Christian Life (Crossway, 1990), 31-34:

The following piece of brilliant analysis is from J. I. Packer, A Quest for Godliness: The Puritan Vision of the Christian Life (Crossway, 1990), 31-34:

Our numbers, it seems, have increased in recent years, and a new interest in the old paths of evangelical theology has grown. For this we should thank God.

But not all evangelical zeal is according to knowledge, nor do the virtues and values of the biblical Christian life always come together as they should, and three groups in particular in today’s evangelical world seem very obviously to need help of a kind that Puritans, as we meet them in their writings, are uniquely qualified to give. These I call restless experientialists, entrenched intellectualists, and disaffected deviationists. They are not, of course, organised bodies of opinion, but individual persons with characteristic mentalities that one meets over and over again.

Take them, now, in order.

[What the Puritans Can Teach Restless Experiential Evangelicals]

Those whom I call restless experientialsts are a familiar breed, so much so that observers are sometimes tempted to define evangelicalism in terms of them.

Their outlook is one of casual haphazardness and fretful impatience, of grasping after novelties, entertainments, and ‘highs’, and of valuing strong feelings above deep thoughts.

They have little taste for solid study, humble self-examination, disciplined meditation, and unspectacular hard work in their callings and their prayers.

They conceive the Christian life as one of exciting extraordinary experiences rather than of resolute rational righteousness.

They dwell continually on the themes of joy, peace, happiness, satisfaction and rest of souls with no balancing reference to the divine discontent of Romans 7, the fight of faith of Psalm 73, or the ‘lows’ of Psalms 42, 88, and 102.

Through their influence the spontaneous jollity of the simple extrovert comes to be equated with healthy Christian living, while saints of less sanguine and more complex temperament get driven almost to distraction because they cannot bubble over in the prescribed manner. In her restlessness these exuberant ones become uncritically credulous, reasoning that the more odd and striking an experience the more divine, supernatural, and spiritual it must be, and they scarcely give the scriptural virtue of steadiness a thought.

It is no counter to these defects to appeal to the specialised counselling techniques that extrovert evangelicals have developed for pastoral purposes in recent years; for spiritual life is fostered, and spiritual maturity engendered, not by techniques but by truth, and if our techniques have been formed in terms of a defective notion of the truth to be conveyed and the goal to be aimed at they cannot make us better pastors or better believers than we were before. The reason why the restless experientialists are lopsided is that they have fallen victim to a form of worldliness, a man-centered, anti-rational individualism, which turns Christian life into a thrill-seeking ego-trip. Such saints need the sort of maturing ministry in which the Puritan tradition has specialised.

What Puritan emphases can establish and settle restless experientialists? These, to start with.

First, the stress on God-centeredness as a divine requirement that is central to the discipline of self-denial.

Second, the insistence on the primacy of the mind, and on the impossibility of obeying biblical truth that one has not yet understood.

Third, the demand for humility, patience, and steadiness at all times, and for an acknowledgement that the Holy Spirit’s main ministry is not to give thrills but to create in us Christlike character.

Fourth, the recognition that feelings go up and down, and that God frequently tries us by leading us through wastes of emotional flatness.

Fifth, the singling out of worship as life’s primary activity.

Sixth, the stress on our need of regular self-examination by Scripture, in terms set by Psalm 139:23-24.

Seventh, the realisation that sanctified suffering bulks large in God’s plan for his children’s growth in grace. No Christian tradition of teaching administers this purging and strengthening medicine with more masterful authority than does that of the Puritans, whose own dispensing of it nurtured a marvellously strong and resilient type of Christian for a century and more, as we have seen.

[What the Puritans Can Teach Entrenched Intellectualist Evangelicals]

Think now of entrenched intellectualists in the evangelical world: a second familiar breed, though not so common as the previous type.

Some of them seem to be victims of an insecure temperament and inferiority feelings, others to be reacting out of pride or pain against the zaniness of experientialism as they have perceived it, but whatever the source of their syndrome the behaviour-pattern in which they express it is distinctive and characteristic.

Constantly they present themselves as rigid, argumentative, critical Christians, champions of God’s truth for whom orthodoxy is all.

Upholding and defending their own view of that truth, whether Calvinist or Arminian, dispensational or Pentecostal, national church reformist or Free Church separatist, or whatever it might be, is their leading interest, and they invest themselves unstintingly in this task.

There is little warmth about them; relationally they are remote; experiences do not mean much to them; winning the battle for mental correctness is their one great purpose.

They see, truly enough, that in our anti-rational, feeling-oriented, instant-gratification culture conceptual knowledge of divine things is undervalued, and they seek with passion to right the balance at this point.

They understand the priority of the intellect well; the trouble is that intellectualism, expressing itself in endless campaigns for their own brand of right thinking, is almost if not quite all that they can offer, for it is almost if not quite all that they have.

They too, so I urge, need exposure to the Puritan heritage for their maturing.

That last statement might sound paradoxical, since it will not have escaped the reader that the above profile corresponds to what many still suppose the typical Puritan to have been. But when we ask what emphases Puritan tradition contains to counter arid intellectualism, a whole series of points springs to view.

First, true religion claims the affections as well as the intellect; it is essentially, in Richard Baxter’s phrase, ‘heart-work’.

Second, theological truth is for practice. William Perkins defined theology as the science of living blessedly for ever; William Ames called it the science of living to God.

Third, conceptual knowledge kills if one does not move on from knowing notions to knowing the realities to which they refer—in this case, from knowing about God to a relational acquaintance with God himself.

Fourth, faith and repentance, issuing in a life of love and holiness, that is, of gratitude expressed in goodwill and good works, are explicitly called for in the gospel.

Fifth, the Spirit is given to lead us into close companionship with others in Christ.

Sixth, the discipline of discursive meditation is meant to keep us ardent and adoring in our love affair with God.

Seventh, it is ungodly and scandalous to become a firebrand and cause division in the church, and it is ordinarily nothing more reputable than spiritual pride in its intellectual form that leads men to create parties and splits.

The great Puritans were as humble-minded and warm-hearted they were clear-headed, as fully oriented to people as they were to Scripture, and as passionate for peace as they were for truth. They would certainly have diagnosed today’s fixated Christian intellectualists as spiritually stunted, not in their zeal for the form of sound words but in their lack of zeal for anything else; and the thrust of Puritan teaching about God’s truth in man’s life is still potent to ripen such souls into whole and mature human beings.

[What the Puritans Can Teach Disaffected Deviationists Evangelicals]

I turn finally to those whom I call disaffected deviationists, the casualties and dropouts of the modern evangelical movement, many of whom have now turned against it to denounce it as a neurotic perversion of Christianity. Here, too, is a breed that we know all too well. It is distressing to think of these folk, both because their experience to date discredits our evangelicalism so deeply and also because there are so many of them. Who are they?

They are people who once saw themselves as evangelicals, either from being evangelically nurtured or from coming to profess conversion with the evangelical sphere of influence, but who have become disillusioned about the evangelical point of view and have turned their back on it, feeling that it let them down.

Some leave it for intellectual reasons, judging that what was taught them was so simplistic as to stifle their minds and so unrealistic and out of touch with facts as to be really if unintentionally dishonest.

Others leave because they were led to expect that as Christians they would enjoy health, wealth, trouble-free circumstances, immunity from relational hurts, betrayals, and failures, and from making mistakes and bad decisions; in short, a flowery bed of ease on which they would be carried happily to heaven—and these great expectations were in due course refuted by events.

Hurt and angry, feeling themselves victims of a confidence trick, they now accuse the evangelicalism they knew of having failed and fooled them, and resentfully give it up; it is a mercy if they do not therewith similarly accuse and abandon God himself.

Modern evangelicalism has much to answer for in the number of casualties of this sort that it has caused in recent years by its naivety of mind and unrealism of expectation.

But here again the soberer, profounder, wiser evangelicalism of the Puritan giants can fulfill a corrective and therapeutic function in our midst, if only we will listen to its message.

What have the Puritans to say to us that might serve to heal the disaffected casualties of modern evangelical goofiness? Anyone who reads the writings of the Puritan authors will find in them much that helps in this way.

Puritan authors regularly tell us, first, of the mystery of God: that our God is too small, that the real God cannot be put without remainder into a man-made conceptual box so as to be fully understood; and that he was, is, and always will be bewilderingly inscrutable in his dealing with those who trust and love him, so that ‘losses and crosses’, that is, bafflement and disappointment in relation to particular hopes one has entertained, must be accepted as a recurring element in one’s life of fellowship with him.

Then they tell us, second, of the love of God: that it is a love that redeems, converts, sanctifies, and ultimately glorifies sinners, and that Calvary was the one place in human history where it was fully and unambiguously revealed, and that in relation to our own situation we may know for certain that nothing can separate us from that love (Rom. 8:38f), although no situation in this world will ever be free from flies in the ointment and thorns in the bed.

Developing the theme of divine love the Puritans tell us, third, of the salvation of God: that the Christ who put away our sins and brought us God’s pardon is leading us through this world to a glory for which we are even now being prepared by the instilling of desire for it and capacity to enjoy it, and that holiness here, in the form of consecrated service and loving obedience through thick and thin, is the high road to happiness hereafter.

Following this they tell us, fourth, about spiritual conflict, the many ways in which the world, the flesh and the devil seek to lay us low;

fifth, about the protection of God, whereby he overrules and sanctifies the conflict, often allowing one evil to touch our lives in order thereby to shield us from greater evils;

and, sixth, about the glory of God, which it becomes our privilege to further by our celebrating of his grace, by our proving of his power under perplexity and pressure, by totally resigning ourselves to his good pleasure, and by making him our joy and delight at all times.

By ministering to us these precious biblical truths the Puritans give us the resources we need to cope with ‘the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune’, and offer the casualties an insight into what has happened to them that can raise them above self-pitying resentment and reaction and restore their spiritual health completely. Puritan sermons show that problems about providence are in now way new; the seventeenth century had its own share of spiritual casualties, saints who had thought simplistically and hoped unrealistically and were now disappointed, disaffected, despondent and despairing, and the Puritans’ ministry to us at this point is simply the spin-off of what they were constantly saying to raise up and encourage wounded spirits among their own people.

[Conclusion]

I think the answer to the question, why do we need the Puritans, is now pretty clear, and I conclude my argument at this point. I, who owe more to the Puritans than to any other theologians I have ever read, and who know that I need them still, have been trying to persuade you that perhaps you need them too. To succeed in this would, I confess, make me overjoyed, and that chiefly for your sake, and the Lord’s. But there, too, is something that I must leave in God’s hands. Meantime, let us continue to explore the Puritan heritage together. There is more gold to be mined here than I have mentioned yet.

January 13, 2016

“This Is One of the Most Important and Definitive Books I Have Read in over Four Decades”

That’s a quote from Derek Thomas. Here is his full statement about Sinclair Ferguson’s new book, The Whole Christ: Legalism, Antinomianism, and Gospel Assurance—Why the Marrow Controversy Still Matters:

It is no exaggeration to insist that the issue dealt with in this book is more important than any other that one might suggest.

For, as Ferguson makes all too clear, the issue is the very definition of the gospel itself. The errors of antinomianism and legalism lie ready to allure unwary hucksters content with mere slogans and rhetoric. I can think of no one I trust more to explore and examine this vital subject than Sinclair Ferguson.

For my part, this is one of the most important and definitive books I have read in over four decades.

Tim Keller, who wrote the foreword to the book (and was the one who suggested Sinclair write the book in the first place), writes that Sinclair

wants to help us understand the character of this perpetual problem—one that bedevils the church today. He does so in the most illuminating and compelling way I’ve seen in recent evangelical literature.

Here are some other folks talking about the importance of this book:

“This book could not come at a better time or from a better source. . . . It is the highest-quality pastoral wisdom and doctrinal reflection on the most central issue in any age.”

Michael Horton

“This may be Sinclair’s best and most important book. Take up and read!”

Alistair Begg

“Without hesitation, this will be the first book I recommend to those who want to understand the history and theology of this most precious doctrine [sanctification].”

Burk Parsons

“It’s hard to imagine a more important book written by a more dependable guide.”

Jeff Purswell

You can read this post for a little bit a background on why Sinclair Ferguson wrote this book.

In fact, you can read Keller’s foreword, the table of contents, the introduction, and the first chapter online for free here.

WTS has the book in stock now—for 45% off the retail price of this hardcover book. If you buy it with the older Marrow book (recently retypeset with helps), you’ll automatically receive 55% off both titles at checkout.

You could also pre-order it from Amazon if you prefer.

January 11, 2016

A Free Bible Study on How to Change the Way You Think, Act, and Experience Life

Read through Acts 16 and the book of Philippians closely.

This study will not proceed verse by verse. Instead it asks questions of all five chapters at once. For example: “Notice Paul’s situation: what are all the varied pressures Paul faces?” and “What do you see and hear about God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit?”

As you gain familiarity with the flow of Acts 16 and Philippians, you can skim more quickly through to assemble your answer to each question. For example, these chapters describe more than a dozen different hardships that Paul faced. Your job is to put yourself in his shoes and notice them.

You will see that each question is put several ways. Don’t necessarily answer every sub-question. Various ways of putting the same basic question help you to look intently at what the Bible is saying.

The study will work through materials familiar to you from the Dynamics of Biblical Change course: the “three trees,” the “eight questions.” The goal is to help you notice things, organize things, sort out things that differ, think clearly and carefully. This study is meant to change the way you think, act, and experience life. It is then meant to change the way you help others.

How can you involve others both in your Scripture study and the self-counseling project? Discussion, accountability, and prayer can greatly contribute to converting ideas into life wisdom.

These same questions can be easily adapted to other books of the Bible, for they are simply a tool to get you to notice what the Bible says to people in real-life situations before God. For example, you could look at 1 Peter, refocusing Question 1 into “Notice particulars of the readers’ situation.” For example, you could study Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles, refocusing Questions 3 and 8 into “What consequences—vicious or gracious circle—do you observe in the stories of people’s lives?”

1. Notice Paul’s situation, all that is swirling around him, both “negative” and “positive.”

What are the varied pressures Paul faces?

Put yourself in Paul’s shoes.

What are Paul’s hardships?

What burdens, temptations, stresses, problems, failures, impotencies, threats and pains—actual and potential—does Paul face?

How are his circumstances difficult?

How are people sinning against Paul?

What are the “positive” parts of Paul’s situation?

What successes, triumphs, vindications, and blessings does Paul experience?

What positive impact is he having on events and people?

How are people responding favorably to him and his efforts?

What is God doing around him and through him?

2. Think about the typical reactions to such circumstances.

Brainstorm: how do you—or people in general—tend to react to the kinds of pressures Paul was under?

What is life like when these things weigh on you?

How do you typically react: thoughts? words? attitudes? emotions? actions?

What temptations would you face in such circumstance? In other words, what does Paul command the Philippians not to do?

How do you—or people in general—tend to react when good things happen?

What temptations come when life abound with good things, when everything’s going your way?

How do you typically react: Thought? Words? Attitudes? Emotions? Actions?

What problem attitudes and actions can arise when you receive success and blessings?

3. Dig for the craving and beliefs that tend to rule the human heart, producing ungodly reactions.

What do Acts 16 and Philippians say, demonstrate, or imply about why people tend to react in ways quite different from Paul?

What beliefs and desires control reactions?

What controls the interpretation of experience?

What motivates the reaction? For example, Philippians 1:17f, 1:28, 2:3f, 2:21, 3:3-7, 3:19, 4:6, and 4:12 and Acts 16:16, 16:19, and 16:27 directly describe some of the false masters that create bad fruit in our lives. Other times more subtle connections are drawn. For example, Philippians 2:12, 13, 15 have implications regarding the causes that underlie “grumbling and disputing” in 2:14.

How do particular sins flow directly from these motives? For example, how might grumbling or anger or worry or compulsive eating or manipulating others flow from the “god” and “mindset” Philippians 3:19 describes? Draw specific links, and explain the logic of the link.

Why don’t positive experiences, behavioral reformation, and positive thinking really change us?

What happens when people experience blessings without dealing with their heart’s motives?

What happens when people try to change their feelings directly, without addressing reigning desires and beliefs?

What happens when people try to act righteously and lovingly, without dealing with the motives that underlie behavior?

What happens when people try to discipline their minds by positive thinking, without changing what rules them?

4. What are the consequences of instinctive sinful reactions?

What “vicious circles” do you see threatening the Philippians?

What negative consequences might arise from sin?

How would bad reactions compound hardships or create new problems or spoil blessings?

What do you reap when you respond to circumstances by instinct?

What possible consequences can you envision if Paul had reacted out of the flesh

to the rigors of itinerant life,

to the honor of apostleship,

to being jailed,

to the jailer’s conversion,

to Epaphroditus’s illness,

to the sins of Euodia & Syntyche,

to poverty and riches,

etc.?

5. Notice what changes lives, inside and out.

What specifically does God reveal of himself in Philippians?

Who is he?

What is he like?

What does he promise?

How does he work?

What has he done?

What do you see him doing?

What will he do?

What truth do you see and hear about the God who is your true environment?

What is the power at work within you?

Philippians does not reveal everything about God, but several well-chosen things. What particular needs are addressed by what God chooses to promise and to reveal of himself?

What resources are tailored to the struggle between sin and godliness?

What resources are brought to bear on the particular hardships of the situation?

How does God work through other people?

You don’t understand God in a vacuum. You don’t grow to change in isolation. How do Acts 16 and Philippians portray godly people influencing and helping one another grow in faith and obedience?

How do you see Paul acting?

What impact do the lives of Timothy and Epaphroditus have?

6. What rules the heart in godly responders?

What rules Paul?

How is Paul’s life determined by faith?

What do Acts 16 and Philippians tell or imply about why Paul responds in such an unusual, “unnatural” way to the things he experiences in life?

What ruled Paul?

What controlled both his interpretation of circumstances and his response?

What is his secret of contentment, the source of his peace, thankfulness and joy?

What did Paul believe, trust, fear, hope in, love, seek, obey?

How does faith make the whole world look different?

How does faith as a ruling motive reinterpret our circumstances for us, even when we are in the midst of suffering or success?

How does genuine faith change people in practical ways?

How does faith change Paul’s desires and directly produce Paul’s outward responses? For example, how do thankfulness, peacemaking and contentment flow directly from believing, trusting and fearing God in Paul’s exact circumstances? Draw the links specifically.

How is turning, repentance, change portrayed? How does faith in God’s message enable us to cross the line? How do we move from our natural reactions to a response of faith like Paul’s? How do we move

from compulsive self-interest (1:17f, 2:3f & 2:21),

from confidence in ourselves (3:3-7),

from making our desires into our gods (3:19),

from living for what is before our eyes and all around us (3:19),

from preoccupation with our anxieties of comforts or riches (4:6 & 4:12, and Acts 16:19),

from fear of what people will do to us (1:28 and Acts 16:27),

from willing and doing my own good pleasure (2:13-15), and

to faith in the living, loving and powerful Savior, Jesus Christ,

to willing and doing God’s good pleasure?

In other words, what happened to Lydia the Philippian jailer, Paul, Silas, Timothy, and the other Philippian Christians Paul writes to?

How is turning to God a once-for-all-act?

How is turning to God a daily, ongoing process, a way of life?

What happens once for all at conversion is a picture of what happens daily in Christian growth. How do Philippians 1:6, 1:9, 1:14, 1:25, 2:12, 2:15, 3:12-16, 4:2, and 4:12 describe this ongoing process of becoming different? True Christians are “disciple” of Jesus, who are in process (Luke 9:23).

What do Euodia and Syntyche need?

7. Look for the specific good fruit.

How does Paul respond?

What does he command readers to do?

How does Paul respond to positive and to negative circumstances?

How does he interpret his world?

How does he act?

What does he say, do and feel in the midst of both trails and victories?

How does he tell you to respond?

What are concrete ways you are told to obey God?

8. What good effects result from the way Paul handled his situation?

What “gracious circles” does he create?

How do Paul, Silas, Timothy, and Epaphroditus affect and influence people and events?

What positive consequences do you see or can you envision happening because of how Paul handles things?

What do you imagine was the impact of obedient Philippians on other people in Philippi?

How do faith and obedience affect others and the world around you?

Personal reflection: What have you learned?

Stop and think. Go back and read what you have written in this study of Paul and the Philippians. Think about your walk with God, your self-counseling project, and your ministry to others. What would it be like if/as the message of Philippians became written on your heart, became the way you instinctively processed life?

Write a paragraph to a page about what made the biggest impression on you personally as you did this study, and what might have the most significant impact as you make it your own.

January 8, 2016

How to Read Calvin’s Institutes and Why You Should Seriously Consider It

If you haven’t yet read C. S. Lewis’s introduction to Athanasius’s On the Incarnation, I’d highly recommend it.

He wants to refute the “strange idea” “that in every subject the ancient books should be read only by the professionals, and that the amateur should content himself with the modern books.”

Lewis finds the impulse humble and understandable: the layman looks at the class author and “feels himself inadequate and thinks he will not understand him.”

“But,” Lewis explains, “if he only knew, the great man, just because of his greatness, is much more intelligible than his modern commentator.”

Lewis therefore made it a goal to convince students that “firsthand knowledge is not only more worth acquiring than secondhand knowledge, but is usually much easier and more delightful to acquire.”

I suspect this holds true with respect to evangelical Calvinists and one of the great theological classics: Calvin’s Institutes. Are we in danger of being a generation of secondhanders?

Let me forestall the “I don’t have time” objection. If you have 15 minutes a day and a bit of self-discipline, you can get through the whole of the Institutes faster than you think. Listen to John Piper:

Most of us don’t aspire very high in our reading because we don’t feel like there is any hope. But listen to this. Suppose you read about 250 words a minute and that you resolve to devote just 15 minutes a day to serious theological reading to deepen your grasp of biblical truth. In one year (365 days) you would read for 5,475 minutes. Multiply that times 250 words per minute and you get 1,368,750 words per year. Now most books have between 300 and 400 words per page. So if we take 350 words per page and divide that into 1,368,750 words per year, we get 3,910 pages per year.

The McNeill-Battles two-volume edition (for now the generally accepted authoritative standard) runs about 1800 pages total—so you could technically read it twice in one year at just 15 minutes a day!

Three reasons why this book in particular should be a particular object of serious study:

1. The Institutes may be easier to read than you think.

J. I. Packer writes, “The readability of the Institutio, considering its size, is remarkable.”

Level of difficulty should not determine a book’s importance; some simple books are profound; some difficult books are simply muddled. What we want are books that make us think and worship, even if that requires some hard work. As Piper wrote in Future Grace, “When my sons complain that a good book is hard to read, I say, ‘Raking is easy, but all you get is leaves; digging is hard, but you might find diamonds.'”

2. The Institutes is one of the wonders of the world.

Karl Barth, the most influential theologian of the 20th century, once wrote: “I could gladly and profitably set myself down and spend all the rest of my life just with Calvin.”

Packer explains that Calvin’s magnum opus is one of the great wonders of the world:

Calvin’s Institutes (5th edition, 1559) is one of the wonders of the literary world—the world, that is, of writers and writing, of digesting and arranging heaps of diverse materials, of skillful proportioning and gripping presentation; the world . . . of the Idea, the Word, and the Power. . . .

The Institutio is also one of the wonders of the spiritual world—the world of doxology and devotion, of discipleship and discipline, of Word-through-Spirit illumination and transformation of individuals, of the Christ-centered mind and the Christ-honoring heart. . . .

Calvin’s Institutio is one of the wonders of the theological world, too—that is, the world of truth, faithfulness, and coherence in the mind regarding God; of combat, regrettable but inescapable, with intellectual insufficiency and error in believers and unbelievers alike; and of vision, valuation, and vindication of God as he presents himself through his Word to our fallen and disordered minds. . . .

3. The Institutes has relevance for your life and ministry.

It can be read as simply an exercise in historical theology, but it should also be read to further your understanding of God’s Word, God’s work, and God’s ways. Packer writes:

The 1559 Institutio is great theology, and it is uncanny how often, as we read and re-read it, we come across passages that seem to speak directly across the centuries to our own hearts and our own present-day theological debates. You never seem to get to the book’s bottom; it keeps opening up as a veritable treasure trove of biblical wisdom on all the main themes of the Christian faith.

Do you, I wonder, know what I am talking about? Dig into the Institutio, and you soon will.

Some Recommended Helps

If you are persuaded, here are a few resources you might want to consider:

As mentioned above, the McNeill-Battles two-volume edition is the most referenced standard edition. The one-volume Beveridge translation is much cheaper, and can also be found online. If you want the cheapest print option and want to get a good feel for the Institutes without reading the whole thing, consider this abridged version by Tony Lane and Hilary Osborne.

But I would recommend the full McNeill-Battles version, along with Tony Lane’s reader’s guide to the Institutes. In the introduction he explains the various options for using it:

The Institutes is divided into thirty-two portions, in addition to Calvin’s introductory material. From each of these an average of some eighteen pages has been selected to be read. These selections are designed to cover the whole range of the Institutes, to cover all of Calvin’s positive theology, while missing most of his polemics against his opponents and most of the historical material. My notes concentrate on the sections chosen for reading but also contain brief summaries of the other material.

Readers have four options:

Read only the selected material and my brief summaries of the rest.

Read only the selected material and use Battles’s Analysis of the Institutes as a summary of the rest.

Concentrate on the selected material but skim through the rest.

Read the whole of the Institutes.The notes guide the reader through the text and also draw attention to the most significant footnotes in the Battles edition. At the beginning of each portion is an introduction and a question or questions to focus the mind of the reader.

For those who want to explore certain sections of the Institutes in greater depth, a fine collection of essays can be found in A Theological Guide to Calvin’s Institutes: Essays and Analysis, edited by David Hall and Peter Lillaback.

For those who want a little more context on Calvin’s life and wider teaching on the Christian life, I think Robert Godfrey’s John Calvin: Pilgrim and Pastor and Michael Horton’s Calvin on the Christian Life are very helpful orientations.

Finally, here is a schedule of reading through Calvin’s Institutes in a year.

Tolle lege!

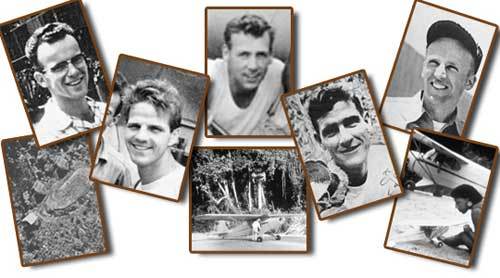

They Were No Fools: 60 Years Ago Today—The Martyrdom of Jim Elliot and Four Other Missionaries

Sixty years ago today—January 8, 1956—28-year-old American missionary Jim Elliot was martyred, along with four missionary partners and friends. He was survived by his wife, Elisabeth, and their 10-month-old daughter Valerie.

Phillip James (“Jim”) Elliot was born in Portland, Oregon, on October 8, 1927. He enrolled at Wheaton College in the fall of 1945 and graduated four years later as a Bible major with highest honors.

The fall of 1949 was a heady season for neo-evangelicalism, seeking to differentiate itself from the fundamentalism of the past, revive the church, win the lost, and gain respect from the culture. 30-year-old Billy Graham—who had graduated from Wheaton six years before Jim Elliot—held his very first crusade, as over 6,000 people came to hear him preach at the Civic Auditorium in Grand Rapids, Michigan (September 13-21). After that he was off to Los Angeles for a two-month campaign that would catapult him to national fame. That December, the first gathering of the Evangelical Theological Society convened, as sixty Bible and theology professor met in Cincinnati to hear an address by Carl Henry, who had published The Uneasy Conscience of Modern Fundamentalism just two years earlier.

It was during this time—October 28, 1949, to be exact—that Jim Elliot penned a journal entry:

He is no fool who gives what he cannot keep to gain that which he cannot lose.

Centuries earlier the 17th century English nonconformist preacher Phillip Henry had said, ”He is no fool who parts with that which he cannot keep, when he is sure to be recompensed with that which he cannot lose.”

In the archives at Wheaton College’s Billy Graham Center you can view Elliot’s journals (published here.) Below is a picture of the page from his journal. (As the Archives note, the underline and asterisk was likely added later after he died.)

A few months later, in 1950, a former missionary to Ecuador told Elliot about the Huaorani (or “Auca”) Indians, a small and fierce unreached people in the jungle. Elliot sensed a call from the Lord to reach this people for Christ.

If you want to hear from Elliot himself around this time, here is a sermon from 1951 delivered in Illinois (or read the transcript):

In 1952, Jim and his friend Pete Fleming set sail for Guayaquil as missionaries, arriving in February. For six months they stayed in Quito (the capital of Ecuador) in order to learn Spanish, before moving deep into jungle, where they lived at Shandia, a mission station.

On January 29, 1953, Jim Elliot proposed to Elisabeth Howard on her 21st birthday, and they were married on October 8 in a civil ceremony in Quito on Jim’s 26th birthday. Their daughter Valerie was born on February 27, 1955.

In the fall of 1955, the missionaries made initial contact with the Huaorani. Nate Saint was able to maneuver his plane in tight circles while lowering a bucket from a rope containing gifts like buttons and rock salt, with more gifts delivered over the next several weeks. Later the missionaries used a loudspeaker to shout simple Huaorani phrases they had learned from a young Huaorani girl who had left the society and befriended Nate Saint’s sister, Rachel. The Huaorani began to reciprocate with gifts of their own.

Nate Saint identified a sandbar on the Curary River, four and a half miles from the main Huaorani location and determined it could be used as a landing strip and camp, calling it “Palm Beach.” The missionaries arrived there on January 3, 1957, flying over the Huaorani settlement to telling them by loudspeaker to meet them there.

The Wikipedia entry for Operation Auca summaries what happened next:

On January 6, after the Americans had spent several days of waiting and shouting basic Huaorani phrases into the jungle, the first Huaorani visitors arrived. A young man and two women emerged on the opposite river bank around 11:15 a.m., and soon joined the missionaries at their encampment. The younger of the two women had come against the wishes of her family, and the man, named Nankiwi, who was romantically interested in her, followed. The older woman (about thirty years old) acted as a self-appointed chaperone. he men gave them several gifts, including a model plane, and the visitors soon relaxed and began conversing freely, apparently not realizing that the men’s language skills were weak. Nankiwi, whom the missionaries nicknamed “George”, showed interest in their aircraft, so Saint took off with him aboard. They first completed a circuit around the camp, but Nankiwi appeared eager for a second trip, so they flew toward Terminal City. Upon reaching a familiar clearing, Nankiwi recognized his neighbors, and leaning out of the plane, wildly waved and shouted to them. Later that afternoon, the younger woman became restless, and though the missionaries offered their visitors sleeping quarters, Nankiwi and the young woman left the beach with little explanation. The older woman apparently had more interest in conversing with the missionaries, and remained there most of the night.

After seeing Nankiwi in the plane, a small group of Huaorani decided to make the trip to Palm Beach, and left the following morning, January 7. On the way, they encountered Nankiwi and the girl, returning unescorted. The girl’s brother, Nampa, was furious at this, and to defuse the situation and divert attention from himself, Nankiwi claimed that the foreigners had attacked them on the beach, and in their haste to flee, they had been separated from their chaperone. Gikita, a senior member of the group whose experience with outsiders had taught him that they could not be trusted, recommended that they kill the foreigners. The return of the older woman and her account of the friendliness of the missionaries was not enough to dissuade them, and they soon continued toward the beach.

On January 8 the missionaries waited, expecting a larger group of Huaorani to arrive sometime that afternoon, if only to get plane rides. Saint made several trips over Huaorani settlements, and on the following morning he noted a group of Huaorani men traveling toward Palm Beach. He excitedly relayed this information to his wife over the radio at 12:30 p.m., promising to make contact again at 4:30 p.m.

The Huaorani arrived at Palm Beach around 3:00 p.m., and in order to divide the foreigners before attacking them, they sent three women to the other side of the river. One, Dawa, remained hidden in the jungle, but the other two showed themselves. Two of the missionaries waded into the water to greet them, but were attacked from behind by Nampa. Apparently attempting to scare him, Elliot, the first missionary to be speared, drew his pistol and began firing. One of these shots mildly injured Dawa, still hidden, and another grazed the missionary’s attacker after he was grabbed from behind by one of the women. . . .

The other missionary in the river, Fleming, before being speared, desperately reiterated friendly overtures and asked the Huaorani why they were killing them. Meanwhile, the other Huaorani warriors, led by Gikita, attacked the three missionaries still on the beach, spearing Saint first, then McCully as he rushed to stop them. Youderian ran to the airplane to get to the radio, but he was speared as he picked up the microphone to report the attack. The Huaorani then threw the men’s bodies and their belongings in the river, and ripped the fabric from their aircraft. They then returned to their village and, anticipating retribution, burned it to the ground and fled into the jungle.

By January 13, four of the bodies had been identified, and one had washed away.

You can watch the story here of what happened afterward in the providence of God:

“They were killed with the sword.

They [were men] of whom the world was not worthy.”

—Hebrews 11:37-38

January 4, 2016

The 8-Point Social-Media Apostasy of Alan Jacobs

Alan Jacobs—Distinguished Professor of the Humanities in the Honors Program at Baylor University and a writer on culture and technology (among many other things)—recently detailed his plans to scale back his use of technology (unfollowing everyone on Twitter, dropping Tumblr and Instagram, writing by hand, listening to music on CDs rather than iTunes, and using a dumb phone instead of a smart phone).

After receiving some pushback on these changes, he wrote a follow-up post that I strongly resonate with, even if I myself am still too slow to implement all of these ideals. In particular, he suggested eight points that cut against the grain of so much thinking today on social media:

I don’t have to say something just because everyone around me is.

I don’t have to speak about things I know little or nothing about.

I don’t have to speak about issues that will be totally forgotten in a few weeks or months by the people who at this moment are most strenuously demanding a response.

I don’t have to spend my time in environments that press me to speak without knowledge.

If I can bring to an issue heat, but no light, it is probably best that I remain silent.

Private communication can be more valuable than public.

Delayed communication, made when people have had time to think and to calm their emotions, is almost always more valuable than immediate reaction.

Some conversations are be more meaningful and effective in living rooms, or at dinner tables, than in the middle of Main Street.

He continues:

In short, peer pressure is always terrible, and social media are a megaphone for peer pressure. And when you use that megaphone all the time you tend to forget that it’s possible to speak at a normal volume. . . .

I spent about seven years reading replies to my tweets, and more than a decade reading comments on my blog posts. I have considered the costs and benefits, and I have firmly decided that I’m not going to be held hostage to that stuff any more. The chief reason is not that people are ill-tempered or dim-witted — though Lord knows one of those descriptors is accurate for a distressingly large number of social-media communications — but that so many of them are blown about by every wind of social-media doctrine, their attention swamped by the tsunamis of the moment, their wills captive to the felt need to respond now to what everyone else is responding to now.

You can read the whole thing here.

I don’t think this requires everyone—or anyone!—to make the exact same choice that Jacobs has made (though perhaps more of us should consider it). But when we do post (or tweet, or update, or what have you), the following questions from Kevin DeYoung are worth keeping in mind:

Is this idea, question, or rant only half baked?

Have I considered that anyone anywhere at anytime could see this?

Do I really know what I’m talking about?

What if I run into this person later today?

Will I feel good about this post later?

Have I sought the counsel of others?

Do I have this person’s phone number?

What is my motivation?

Have I tried to love my neighbor as I love myself?

Have I lost all sense of proportion?

You can read Kevin’s explanation of each point here.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers