Justin Taylor's Blog, page 54

March 30, 2016

Mark Noll on Three Things about Awakenings in Church History

Mark Noll:

As a historian, three things increasingly impress me about awakenings in church history:

First, that they really do occur, and—from medieval, monastic revivals through classic evangelical awakenings to modern Pentecostal renewal—they really have brought great benefit to the church.

Second, revivals tend to exaggerate, so that along with the real benefit often come increased problems like exalted opinions of one’s self in God’s general design.

Third, most of the circumstances that have made a permanent difference in spreading the Gospel and deepening the church’s understanding of the Gospel have taken place in ordinary church settings rather than revivals.

—quoted in “What Christian Leaders Are Saying about Spiritual Renewal,” Vocatio 11, no. 1 (Winter 1999): 6.

HT: John Piper

Why Mark Dever Thinks You Should Use Alec Motyer’s New “Psalms of the Day: A New Devotional Translation”

Here is Mark Dever’s foreword (posted with permission) to Alec Motyer’s Psalms of the Day: A New Devotional Translation (Christian Focus, 2016). [Note that Motyer also has written Isaiah by the Day: A New Devotional Translation (Christian Focus, 2001).]

One of the first—and still perhaps the best—summaries of the Bible in just a few messages that I have heard was given by Alec Motyer about twenty-five years ago. I was a student, speaking to students at the same conference. But when I saw Motyer was speaking on this topic, I could not resist attending all his lectures. And the view of God’s Word he gave me has been a lasting gift ever since.

One of the first—and still perhaps the best—summaries of the Bible in just a few messages that I have heard was given by Alec Motyer about twenty-five years ago. I was a student, speaking to students at the same conference. But when I saw Motyer was speaking on this topic, I could not resist attending all his lectures. And the view of God’s Word he gave me has been a lasting gift ever since.

In your hand you have three gifts.

Translation

First, one of our finest scholars has used his knowledge and long experience as a linguist and a Christian to give us a fresh translation of all 150 Psalms. This in and of itself is a gift of no small value. The translation is fresh in a number of ways-the use of Yah and Yahweh, the word choice, even some modern idioms. But these translations have not been done—as they so often are—by those who are heavy in thinking of communications and light in understanding the text. Alec Motyer has tutored generations of pastors—me among them—in our understanding of God’s Word. His Christ-centered reading of the Old Testament gives a fullness and a resonance to his reading of the Psalms which seems like the way our Lord taught us to read the Psalms. And the reading is reflected even in the translation itself. If you want to know more about the way he has approached translating the Psalms, take a moment and read the introduction. Embedded within the translation, you’ll also find outlines which are suggestive for Bible study leaders and preachers in communicating the information.

Notes

Another gift that Dr Motyer has given us is in the notes. And let me be clear—in preparing to write this foreword—I read every word in the book, and the notes are themselves of great help to the Christian who would understand and appreciate the Psalms. Clear statements that would seem like hyperbole from others come with simple weight from Motyer’s pen. For example, ‘Psalm 51 is the Old Testament’s central text on repentance.’ In his notes he educates the reader on what was and was not done in Hebrew poetry. What causes some commentators to stumble in Psalm 105, he presents as an intentional emphasis by the author on our obedience. The ‘Pause for Th ought’ about Hezekiah’s tunnel on Psalms 123-125 is piercing! Plenty more perspective-giving notes await the reader. In some of them, apparent problems are solved. In others, I’ve been shown better ways to conceive what the Psalmist is saying, sometimes suggesting new avenues for understanding the whole Psalm, and often making Christ clearer in the Psalm. Again and again he reads the Psalms sensitively and persuasively as being centered on Jesus Christ. All together, even in the notes we have a rare combination of textual, grammatical knowledge of the Psalms with wide knowledge of the whole sweep of Scripture—Old and New, together with systematic theology, Christian experience, all with the warmth of a brother in Christ who knows himself to be more student than teacher, to have received more than he could ever give.

Devotions

The ‘Pause for Thoughts’ devotions are a final gift that our author leaves us with. They act as a commentary for the reader who feels intimidated by the specific notes in the margins of the text. They summarize the main contribution the preceding Psalms make. And yet they are more than summary. They help to give us perspective on the significance or importance of what we’ve read, often in such a way that at least I have wanted to go back and re-read the preceding Psalm. Look at his thoughts on Psalm 37 for an example of this. Or those about hope in Psalms 61-63. Reflecting on Psalm 69, Motyer writes ‘Our only escape from the Son of Man, our Judge, is to fl ee to the Son of Man, our Saviour.’ His summary of the Psalms’ teaching on the messianic king in his ‘Pause for Thought’ after Psalm 72 is a tiny, splendid, encouraging tour-de-force! Pithy and learned expressions abound. ‘To abandon prayer is to embrace atheism’ (p. 246). In these concluding ‘Pauses,’ Motyer’s long Christian experience, his knowledge of the New Testament, as well as the Old, act together with the Psalm being considered to serve us. These thoughts are expository without being dry, devotional without being forced. His thoughts flow from an intelligent and careful reading of the Psalms immediately before him. And as we get to look over his shoulder, we learn to read the Psalms better for ourselves, and for those we may be called to teach.

Throughout this work, Motyer’s writing gives us a delicious combination—richly full, concisely put. For generations now, Alec Motyer has been one of the best at combining the smallest of details with the grand sweep of the biblical narrative, and in ways which are not wrongly original or novel, but which are faithful and obvious in the text once we’ve noticed them. Here a master of systematic and biblical theology shows us the artifi cial nature of that very distinction. And he does it while taking us through the church’s hymn-book, the Psalms, and all in seventy-three days ! Read and profit.

—Mark Dever

Senior Pastor, Capitol Hill Baptist Church and President, 9Marks.org, Washington, DC

To read some samples from this devotional commentary, you can go here.

March 29, 2016

David Hackett Fischer’s Complaint about Modern History Writing

Celebrated historian David Hackett Fischer:

Professional historians have shown so little interest in the subject that in two centuries no scholar has published a full-scale history of Paul Revere’s ride. During the 1970s, the event disappeared so completely from academic scholarship that several leading college textbooks in American history made no reference to it at all. One of them could barely bring itself to mention the battles of Lexington and Concord.

The cause of this neglect is complex. One factor is a mutual antipathy that has long existed between professional history and popular memory. Another of more recent vintage is a broad prejudice in American universities against patriotic events of every kind, especially since the troubled years of Vietnam and Watergate. A third and fourth are the popular movements called multicultural-ism and political correctness. As this volume goes to press, the only creature less fashionable in academe than the stereotypical “dead white male,” is a dead white male on horseback.

Perhaps the most powerful factor, among professional historians at least, is an abiding hostility against what is contemptuously called histoire événimentielle [event history] in general. As long ago as 1925, the antiquarian scholar Allen French fairly complained that “modern history burrows so deeply into causes that it scarcely has room for events.” His judgment applies even more forcefully today. Path-breaking scholarship in the 20th century has dealt mainly with social structures, intellectual systems, and material processes. Much has been gained by this enlargement of the historian’s task, but something important has been lost. An entire generation of academic historiography has tended to lose sense of the causal power of particular actions and contingent events.

An important key here is the idea of contingency—not in the sense of chance, but rather of “something that may or may not happen,” as one dictionary defines it. An organizing assumption of this work is that contingency is central to any historical process, and vital to the success of our narrative strategies about the past.

This is not to raise again ill-framed counterfactual questions about what might have happened in the past. It is rather to study historical events as a series of real choices that living people actually made. Only by reconstructing that sort of contingency (in this very particular sense) can we hope to know “what it was like” to have been there; and only through that understanding can we create a narrative tension in the stories we tell about the past.

—David Hackett Fischer, Paul Revere’s Ride (Oxford University Press, 1984), xiv-xv.

In a footnote, Fischer adds: “Any true revival of serious narrative history must rest on two firm premises: first, no narrative without contingency; second, no history without a rigorous respect for fact” (374 n 4).

March 26, 2016

15 Pieces of Writing Advice from C. S. Lewis

In his letters and other sources, C. S. Lewis left various bits of advice on the craft of writing. Below are 15 of the things he said. The bold is my restatement, followed by his actual quote.

1. Avoid distractions.

“Turn off the Radio.”

2. Read all the good books you can.

“Read all the good books you can, and avoid nearly all magazines.”

3. Always write and read with your ear, not your eye.

“Always write (and read) with the ear, not the eye. You shd. hear every sentence you write as if it was being read aloud or spoken. If it does not sound nice, try again.”

4. Write only about what interests you.

“Write about what really interests you, whether it is real things or imaginary things, and nothing else. (Notice this means that if you are interested only in writing you will never be a writer, because you will have nothing to write about . . .)”

5. Work hard at being clear.

“Take great pains to be clear. Remember that though you start by knowing what you mean, the reader doesn’t, and a single ill-chosen word may lead him to a total misunderstanding. In a story it is terribly easy just to forget that you have not told the reader something that he needs to know—the whole picture is so clear in your own mind that you forget that it isn’t the same in his.”

6. Don’t throw away writings projects that you put aside.

“When you give up a bit of work don’t (unless it is hopelessly bad) throw it away. Put it in a drawer. It may come in useful later. Much of my best work, or what I think my best, is the re-writing of things begun and abandoned years earlier.”

7. Write, don’t type.

“Don’t use a typewriter. The noise will destroy your sense of rhythm, which still needs years of training.” (For more on this, go here.)

8. Know the meaning of all the words you use.

“Be sure you know the meaning (or meanings) of every word you use.”

9. Avoid ambiguity.

“The way for a person to develop a style is to know exactly what he wants to say, and to be sure he is saying exactly that. The reader, we must remember, does not start by knowing what we mean. If our words are ambiguous, our meaning will escape him. I sometimes think that writing is like driving sheep down a road. If there is any gate open to the left or the right the reader will most certainly go into it.”

10. Use language to make your meaning clear and make sure it can’t mean anything else.

“Always try to use the language so as to make quite clear what you mean and make sure your sentence couldn’t mean anything else.”

11. Choose the plain and direct word over the long and vague one.

“Always prefer the plain direct word to the long, vague one. Don’t implement promises, but keep them.”

12. Choose the concrete noun over the abstract one.

“Never use abstract nouns when concrete ones will do. If you mean ‘More people died’ don’t say ‘Mortality rose.'”

13. Make the reader feel what you are describing rather than telling the reader what it is with an adjective.

“Don’t use adjectives which merely tell us how you want us to feel about the things you are describing. I mean, instead of telling us the thing is ‘terrible’ describe it so that we’ll be terrified. Don’t say it was ‘delightful'; make us say ‘delightful’ when we’ve read the description. You see, all those words (horrifying, wonderful, hideous, exquisite) are only like saying to your readers ‘Please, will you do my job for me.'”

14. Use words appropriate for the subject.

“Don’t use words too big for the subject. Don’t say ‘infinitely’ when you mean ‘very'; otherwise you’ll have no word left when you want to talk about something really infinite.”

15. Don’t feel obligated to bring explicitly Christian bits to your writing.

“We must not of course write anything that will flatter lust, pride or ambition. But we needn’t all write patently moral or theological work. Indeed, work whose Christianity is latent may do quite as much good and may reach some whom the more obvious religious work would scare away. The first business of a story is to be a good story. When Our Lord made a wheel in the carpenter shop, depend upon it: It was first and foremost a good wheel. Don’t try to ‘bring in’ specifically Christian bits: if God wants you to serve him in that way (He may not: there are different vocations) you will find it coming in of its own accord. If not, well—a good story which will give innocent pleasure is a good thing, just like cooking a good nourishing meal. . . . Any honest workmanship (whether making stories, shoes, or rabbit hutches) can be done to the glory of God.”

Sources:

Numbers 1-8: C. S. Lewis letter to a girl named Thomasine (December 14, 1959), a seventh-grader whose teacher had assigned her students to write to a famous author for writing advice.

Number 9: From C. S. Lewis’s final interview (May 7, 1963), six months before he died. He was responding to a question by Sherwood Wirt (1911-2001), who asked, “How would you suggest a young Christian writer go about developing a style?”

Numbers 10-14: C. S. Lewis letter to Joan Lancaster (June 26, 1956), a young American girl who had written to him for advice on writing.

Number 15: C. S. Lewis letter to Cynthia Donnelly (August 14, 1954).

March 23, 2016

An Interview with John Fea on His New History of the American Bible Society

John Fea (Ph.D, Stony Brook University) is Professor of American History and Chair of the History Department at Messiah College in Grantham, Pennsylvania.

John Fea (Ph.D, Stony Brook University) is Professor of American History and Chair of the History Department at Messiah College in Grantham, Pennsylvania.

He is perhaps best known for his book, Was America Founded as a Christian Nation? A Historical Introduction (a revised edition of which will be published in September 2016). The first edition (2011) was one of three finalists for the George Washington Book Prize, one of the largest literary prizes in the United States. His most popular-level book is Why Study History? Reflecting on the Importance of the Past, an engaging guide and introduction for Christians to the study of history. published by Baker Academic in 2013.

As a blogger and podcaster, Dr. Fea is at the forefront of networking fellow historians and facilitating reflection on the relationship between religion and American history. His latest project, due out next month from Oxford University Press, is along those lines: The Bible Cause: A History of the American Bible Society. (You can read Thomas Kidd’s review of the book in The Weekly Standard.)

He recently answered a few questions I had about the American Bible Society (ABS), its origins, context, translations, and its relationship to Catholics, technology, nationalism, and more—as well as what it’s like to have academic freedom while writing an institutional history.

I suspect many readers don’t know that there is such a thing as the American Bible Society. Can you give us a thumbnail sketch of the organization’s history: when was it started, what does it do, and does it still exist today?

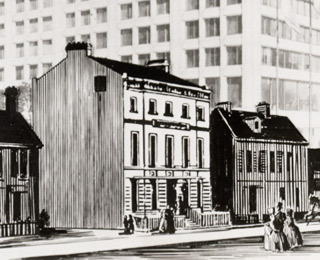

72 Nassau Street, in lower Manhattan: the first permanent home of the ABS beginning in 1822.

The American Bible Society (ABS) was founded in 1816 for the purpose of publishing, translating, and selling Bibles, “without note or comment,” in the United States and, eventually, around the world. Until 2015, the ABS was located in New York City.

Last summer it moved its headquarters to Philadelphia’s Independence Square just in time to celebrate its 200th anniversary in May 2016. Today it is a Christian ministry focused less on publishing and translating and more on what the leaders of the ABS describe as “scripture engagement”—teaching people who to use the Bible in their everyday lives.

Can you put the founding of the ABS in context for us, especially in relationship to other Christian benevolent societies founded after the Revolution and before the Civil War?

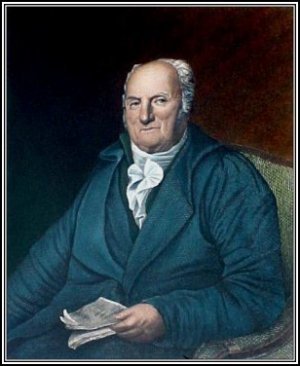

Elias Boudinot (1740-1821)

The ABS was founded by evangelical Christians, many of whom were Federalists and former Federalists. They wanted to distribute the Bible as a way of spreading the good news of the Gospel and strengthening the Christian character of the American republic. Many of these founders, including Elias Boudinot, the first President of the ABS, were concerned about moral decline in the United States.

The ABS emerged out of the evangelical revival described by historians as the ”Second Great Awakening.” It was one of several benevolent societies born during the revival. Some of these societies included the American Sunday School Union, the American Temperance Union, and the American Anti-Slavery Society.

What Bible translations are associated with the ABS?

Until the 20th century, the ABS distributed the King James Version of the Bible because it was the translation, to use the words of the ABS constitution, that was “in common use.” Eventually the ABS sold Bibles in the Revised Version, the American Standard Version, and the Revised Standard Version. (The decision to sell the RSV was a controversial one).

Good News for Modern Man, New Testament, 1st edition (1966)

It was not until the 1960s and 1970s that the ABS produced its own translation–Today’s English Version. The New Testament version of Today’s English Version was finished in 1966 and marketed in a paperback edition titled Good News for Modern Man. This New Testament translation quickly became the bestselling paperback in the American history, surpassing Dr. Spock’s Baby and Child Care. In 1976, the entire Good News Bible (Old Testament and New Testament) was released. Today’s English Version was controversial among some evangelical groups because it employed a method of translation known as “dynamic equivalence.” The brainchild of ABS translator Eugene Nida, dynamic equivalence was less a “word for word” approach to translation, and more of a “meaning for meaning” or “thought for thought” method. Many evangelicals feared that such an approach to translation undermined their belief in the verbal plenary inspiration of the Bible. Nida’s goal was to make the Bible more accessible to readers. The Good News Bible was written in easy-to-understand prose. In this sense, it was unlike any other Bible on the market.

In the 1990s, the ABS published another dynamic equivalence Bible called the Contemporary English Version. It was translated at a lower reading level than the Good News Bible.

As a non-denominational Protestant organization, what has been the relationship of the ABS to the Roman Catholic church, and vice-versa? Has that changed over the past two centuries?

At the New York City meeting in which the ABS was founded in 1816, Catholics were invited to participate in its work. But for much of the 19th and 20th centuries the ABS was a largely Protestant organization. In the 1840s and 1850s it participated in the strident anti-Catholicism that defined American life in these decades. It was not until the 1960s, after Vatican II, that the ABS and the Roman Catholic Church began cooperating on Bible translations. The Catholic Church, for example, endorsed the Good News Bible and the ABS began publishing Bibles with the Apocrypha. Today the ABS works closely with the Catholic Church in Bible distribution and scripture engagement.

We hear presidential candidates talking about “making America great again.” Was that part of the original purpose for ABS? In what ways can this be problematic?

As I write in the introduction to The Bible Cause, the book is both a history of the American Bible Society and a history of theAmerican Bible Society. It is hard to separate the religious work of the ABS from its mission to strengthen the Christian identity of the United States. The ABS never saw this dual agenda as problematic. Its leadership worked closely with American presidents and other political leaders to advance the cause of a Bible-centered nation. The founders of the ABS were much more concerned with the direction that country was moving under the leadership of the “godless” Jeffersonian Republicans than they were with somehow turning back the clock to a Christian golden age. Today the ABS is hesitant to use “Christian nation” language, probably because it is so politically-charged. But the leadership is still interesting in strengthening the American republic with a healthy dose of scriptural teaching.

How did the ABS adapt over the years to changes in technology and to changes in cultural attitude about the Bible?

The American Bible Society has always been at the forefront of innovation, both in American Christianity and the nation as a whole. The ABS was and is cutting-edge. It was the first publisher in the United States to use steam-power presses. It quickly embraced Braille, talking Bibles, direct marketing, postage seals, music videos, and digital scripture products. I think it is fair to say that this spirit of innovation continues today as the ABS staff seeks out new ways to get people engaged with the message of the scriptures.

What is the current role and size of the ABS, both domestically and abroad?

The ABS is a ministry based in Philadelphia with a $300 million endowment and a mission to engage 100 million Americans with the Bible by 2025. Internationally, they work with the United Bible Societies in the distribution of Bibles and the promotion of scriptural engagement.

The ABS asked you to write this history of their organization. As a historian, how do you navigate the waters of independence when writing an official institutional history?

This has been a unique experience. I was not interested in writing an “authorized” or “official” history of the American Bible Society. When I was approached about writing this history I asked for full academic freedom to tell the story in the way that I thought it needed to be told. The ABS leadership agreed and were willing to give me full access to the archives of the organization. As I wrote the book I was ever aware of the fact that the ABS was taking a real risk here. I think The Bible Cause is a largely sympathetic account of the organization, but some in leadership at the ABS were not always pleased with how I told and framed the story. In the end, I am not sure some folks at the ABS understood the difference between a scholarly history and a promotional piece.

Based on your experience, do you have any advice for fellow historians seeking to write an accurate institutional history—a genre not typically thought of as a “page turner”?

The jury is still out on whether or not I am the right person to give advice about how to write a compelling history of an institution. Having said that, I would offer two related pieces of advice.

First, I tried to avoid getting too caught up in the details. I did not try to cover every program and initiative that the ABS sponsored over the last two-hundred years. This is not a comprehensive history of the ABS.

Second, I tried to connect the story of the ABS with the story of the United States and the story of American religious history. I hope that such an approach offers relief to the tedium often associated with institutional history.

March 22, 2016

Who Needs Classical Music? A Meditation on The Shawshank Redemption

Julian Johnson, Regius Chair of Music at Royal Holloway, University of London, writes about this scene:

Anyone who knows The Shawhank Redemption will recall the effect of this iconic moment, when the prisoner, Andy Dufresne, locks himself in the prison office and plays a duet from Mozart’s opera The Marriage of Figaro over the PA system. The entire compound comes to a standstill as the strains of the music drift over the exercise yard and hardened prisoners and guards alike stand open-mouthed, silenced by the arresting beauty of a music from a distant place.

Nothing could sum up better what I have tried to say in this book.

Of course, you might think, any music would have done; music, as a whole, has this capacity to make the imaginary seem palpable, to promise something that exceeds our immediate reality, to recollect the loss of something infinitely valuable.

But I think it’s significant that the director, Frank Darabont, chose to use Mozart at this moment. The disjunction between the world of classical opera and the brutality of the prison in which the film is set, its very strangeness, is the key to its power to stop “every last man” in its tracks. Part of its beauty, and the incomprehensible power of its fragility, derives from this sense of distance—that this music comes from elsewhere and speaks of a better order of things that, for this brief moment, cuts through the hardened surface of everyday reality at Shawshank.

The sense is enhanced by the effect of hearing music from an old vinyl record, played through the tinny speakers of the prison PA system, whose normal function is one of repressive control. The hiss and whirr of the record, the distortion of the speakers, combine to create the effect of a music heard from a great distance, not just in place but also in time. The beauty of these voices, it seems, is brought into the present from another age, as an ephemeral restoration of something lost of the past. For “every last man” this music sounds from a quite different world, yet it enters the mind like a distant, long-forgotten memory and the most fragile of future promises. Allowing it to sound through the bars of this “drab little cage” is a deeply transgressive act, for which Dufresne gets two weeks in solitary confinement, and no doubt a beating too.

Professor Johnson wrote this in the preface to the paperback edition of Who Needs Classical Music? Cultural Choice and Musical Value (Oxford University Press, 2002), xi-xii. He goes on to state the concern, question, and proposal he offers in the first edition of his book:

My sole concern was to restate the claims of classical music for a contemporary world in which they seem to have become almost inaudible.

My question was how classical music might still have a distinctive value in the twenty-first century.

My answer was to suggest that, at its best, this music involves us in tracing out patterns of thought, feeling, and experience that relate to some of our highest ideals as human beings.

March 21, 2016

An Interview with George Marsden on His New Biography of C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity

George M. Marsden, professor of history emeritus at the University of Notre Dame, is one of the most influential historians of Christianity in the twentieth century—particularly when it comes to evangelicalism and fundamentalism and higher education. To name just two of his volumes, Fundamentalism and American Culture (Oxford University Press, 1980; 2nd ed., 2006) is widely considered a landmark contribution to the field, and his biography of Jonathan Edwards: A Life (Yale University Press, 2003) won Columbia University’s prestigious Bancroft Prize.

His latest book, due out next week from Princeton University Press, is C. S. Lewis’s “Mere Christianity”: A Biography, part of their Lives of Great Religious Books series.

Professor Marsden answered some questions about the genre of the book, his background with the works of Lewis, how the BBC came to broadcast religious talks and how they became books, why the book has had such staying power and influence, and what he’s working on next.

What is “reception history,” and how is this work a form of it?

“Reception history” is simply the history of how a book was received over the years. This Princeton University Press series on “the Lives of Great Religious Books” is to present “biographies” of books. So the life of a book involves both its origins and the story of how it has been received and interpreted over the years.

You write in the book that you were not influenced at an early age by Mere Christianity, as so many Christians in the academic world have been. Can you tell us a bit about your own relationship to Lewis’s work?

In the early 1950s, when I was a boy, my father (who was an Orthodox Presbyterian minister) suggested that I read The Screwtape Letters. I enjoyed that and was impressed that such a well-educated writer still believed in the supernatural beings. But I don’t remember encountering Mere Christianity before I was in my twenties. Then I would run into other young Christians who were very enthusiastic about it and others of Lewis’s works. I cannot remember when I first read Mere Christianity and, although I had a good impression of it and others of Lewis’s works, I do not think I read Mere Christianity very carefully. But I was well aware of its soaring reputation. So when, Fred Appel, the Princeton editor, asked me if I wanted to contribute to his series, I suggested writing on that. I had written a couple of books on Jonathan Edwards, and I was looking for a subject that would be similarly inspiring to work on. And I was well rewarded. Almost everything of Lewis is edifying and a pleasure to read.

For Americans in the 21st century, it may be perplexing to know that the origin of this work was as radio addresses for the British Broadcasting Company. How did it come about that a Christian professor was able to give unabashed talks on the truth of Christianity over the public airwaves?

For Americans in the 21st century, it may be perplexing to know that the origin of this work was as radio addresses for the British Broadcasting Company. How did it come about that a Christian professor was able to give unabashed talks on the truth of Christianity over the public airwaves?

That is an interesting aspect of the origins of the book. The BBC was a noncommercial company serving the British people under a royal charter. It included a substantial religious dimension. Great Britain was officially a Christian nation, and the company leadership took that more seriously than did most of the British public. For instance, until World War II, Sunday programming not only included church services and religious programs, but also had to be tasteful, so that there was no jazz or comedy shows on Sundays. During the war, when the BBC had a monopoly on broadcasting, those rules were relaxed a bit for the sake of the troops. But the religion department oversaw quite a few weekday religious programs as well as Sunday broadcasts. Lewis fit their purposes well. Because of the war, they did not want anything controversial. And Lewis’s talks could be of interest to people of all sorts of Christian backgrounds.

If my chronology is correct, there were four series of talks delivered by Lewis over the course of a year: (1) a series of four 15-minute talks (plus a response to listeners’ objections) from August to September of 1941; (2) a series of five 15-minute talks from January to February of 1942; and (3) a series of eight 10-minute talks from September to November of 1942; and (4) a fourth and final series of seven 15-minute talks from February to April 1944. From there, how did they reach publication form, culminating in Mere Christianity? How much did the material change from the original radio manuscript to the final edition?

Lewis had the first two sets of talks published in a little paperback called simply Broadcast Talks [1942]. (In the American edition that soon followed it had the more engaging title, The Case for Christianity [1943].)

Lewis had the first two sets of talks published in a little paperback called simply Broadcast Talks [1942]. (In the American edition that soon followed it had the more engaging title, The Case for Christianity [1943].)

Then he published the third and fourth sets of talks as additional paperbacks, Christian Behaviour [1943] and Beyond Personality [UK: 1944, US: 1945]. He edited the broadcasts for publication and added a number of extra chapters, especially in Christian Behaviour.

When he finally put these together as Mere Christianity in 1952, he did just some minor editing and added a very important new preface that explained what he meant by “Mere Christianity.” I try to identify all the substantial changes in an appendix.

[Note: you can listen below to Lewis’s final BBC recording, the only audio from the entire series to have survived.]

I know that the ultimate answer to the following question is “read the book to find out!” but as a preview, could you tell us why you think this book in particular has such enduring “life” or “vitality” (to use your descriptions)?

One of the most remarkable aspects of the life of this book is that, even though it was not originally designed to be a single book, it had maintained its vitality far better than most other books of its time. Remarkably, it has sold quite a bit better in the twenty-first century than it did in Lewis’s day, when it already sold well. It has sold over three and a half million copies in English alone. So one major question I try to answer in my book is: what accounts for its unusual lasting vitality? It helps that Lewis always looked for timeless truths, as the idea of “Mere Christianity” (or the beliefs that almost all Christians have shared through the ages) illustrates. So the book is less dated than most books. Also Lewis was a brilliant communicator. He listened to how ordinary people talked and then translated his views into language they could understand. And even though he uses lots of arguments he always puts these in imaginative contexts that make them come alive. So he uses many more vivid analogies and metaphors than do most non-fiction writers. And he acts as a friendly companion and guide on a journey that he himself has taken from unbelief to belief. At the same time he does not draw attention to himself but leads the reader to see the challenging beauty of the core Christian message.

Can you tell us any future projects you are working on now?

I have been working on the renaissance of evangelical Christian thought of recent decades. If one goes back to the mid-twentieth century, there was not much in the line of first-rate evangelical thought in most fields. As late as the early 1990s Mark Noll could lament The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind. Today we have one of the richest intellectual communities that there is. So I’m seeing if I can tell the story of that transformation. I’ll have to see how that goes.

March 18, 2016

8 Points from the American College of Pediatricians on Gender Identity in Children

The American College of Pediatricians (ACPeds)—a socially conservative association of pediatricians and healthcare professionals in the United States, founded in 2002—has issued the following statement on gender identity in children. The bold highlighting below is mine.

The American College of Pediatricians urges educators and legislators to reject all policies that condition children to accept as normal a life of chemical and surgical impersonation of the opposite sex. Facts – not ideology – determine reality.

1. Human sexuality is an objective biological binary trait: “XY” and “XX” are genetic markers of health – not genetic markers of a disorder. The norm for human design is to be conceived either male or female. Human sexuality is binary by design with the obvious purpose being the reproduction and flourishing of our species. This principle is self-evident. The exceedingly rare disorders of sexual differentiation (DSDs), including but not limited to testicular feminization and congenital adrenal hyperplasia, are all medically identifiable deviations from the sexual binary norm, and are rightly recognized as disorders of human design. Individuals with DSDs do not constitute a third sex.

2. No one is born with a gender. Everyone is born with a biological sex. Gender (an awareness and sense of oneself as male or female) is a sociological and psychological concept; not an objective biological one. No one is born with an awareness of themselves as male or female; this awareness develops over time and, like all developmental processes, may be derailed by a child’s subjective perceptions, relationships, and adverse experiences from infancy forward. People who identify as “feeling like the opposite sex” or “somewhere in between” do not comprise a third sex. They remain biological men or biological women.

3. A person’s belief that he or she is something they are not is, at best, a sign of confused thinking. When an otherwise healthy biological boy believes he is a girl, or an otherwise healthy biological girl believes she is a boy, an objective psychological problem exists that lies in the mind not the body, and it should be treated as such. These children suffer from gender dysphoria. Gender dysphoria (GD), formerly listed as Gender Identity Disorder (GID), is a recognized mental disorder in the most recent edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association (DSM-V). The psychodynamic and social learning theories of GD/GID have never been disproved.

4. Puberty is not a disease and puberty-blocking hormones can be dangerous. Reversible or not, puberty- blocking hormones induce a state of disease – the absence of puberty – and inhibit growth and fertility in a previously biologically healthy child.

5. According to the DSM-V, as many as 98% of gender confused boys and 88% of gender confused girls eventually accept their biological sex after naturally passing through puberty.

6. Children who use puberty blockers to impersonate the opposite sex will require cross-sex hormones in late adolescence. Cross-sex hormones are associated with dangerous health risks including but not limited to high blood pressure, blood clots, stroke and cancer.

7. Rates of suicide are twenty times greater among adults who use cross-sex hormones and undergo sex reassignment surgery, even in Sweden which is among the most LGBQT – affirming countries. What compassionate and reasonable person would condemn young children to this fate knowing that after puberty as many as 88% of girls and 98% of boys will eventually accept reality and achieve a state of mental and physical health?

8. Conditioning children into believing a lifetime of chemical and surgical impersonation of the opposite sex is normal and healthful is child abuse. Endorsing gender discordance as normal via public education and legal policies will confuse children and parents, leading more children to present to “gender clinics” where they will be given puberty-blocking drugs. This, in turn, virtually ensures that they will “choose” a lifetime of carcinogenic and otherwise toxic cross-sex hormones, and likely consider unnecessary surgical mutilation of their healthy body parts as young adults.

Michelle A. Cretella, M.D.

President of the American College of Pediatricians

Quentin Van Meter, M.D.

Vice President of the American College of Pediatricians

Pediatric Endocrinologist

Paul McHugh, M.D.

University Distinguished Service Professor of Psychiatry at Johns Hopkins Medical School and the former psychiatrist in chief at Johns Hopkins Hospital

An Interview with Mitch Stokes on “How to Be an Atheist”

Mitch Stokes is an impressive thinker. After receiving a master’s degree in mechanical engineering and after securing five patents for turbine engines, he turned his attention to philosophy and religion. He did an MA in religion at Yale under Nicholas Wolterstorff, and then did an MA and a PhD at Notre Dame under Alvin Plantinga.

Mitch Stokes is an impressive thinker. After receiving a master’s degree in mechanical engineering and after securing five patents for turbine engines, he turned his attention to philosophy and religion. He did an MA in religion at Yale under Nicholas Wolterstorff, and then did an MA and a PhD at Notre Dame under Alvin Plantinga.

His new book, now available from Crossway, is entitled How to Be an Atheist: Why Many Skeptics Aren’t Skeptical Enough.

The influential philosopher Peter van Iwagen—the John Cardinal O’Hara Professor of Philosophy at Notre Dame—writes that ”How to Be an Atheist is the best popular discussion of the (alleged) conflict between science and religion that I have ever read.”

J. P. Moreland writes in the foreword:

How to Be an Atheist is a model work in philosophical apologetics in the sense that Stokes painstakingly criticizes atheistic views that are raised against Christianity and responds to objections raised against Christianity. But it would be a grave mistake to think that this is just another apologetics book. No, this book gives the reader an education in a number of important areas and it teaches you how to think. Time and time again, Stokes takes an angle on an issue that is different, insightful and refreshing. And his research is exemplary.

If you are a believer, I urge you to get this book, encourage friends to get it, and form a study group in which you can work through the material slowly and thoughtfully. I promise you, it is well worth the effort. I meet many Christians who wish they could go back to graduate school and get an education relevant to their Christianity, but finances and other commitments present insurmountable obstacles to this move. Well, there is a second alternative: read books like this one and you will get an education.

If you are an atheist who is intellectually open to investigating some of the problems in your worldview, this is the book for you. It has an irenic tone and deals fairly and proportionately with its subject matter.

Dr. Stokes was recently at Crossway where I had the opportunity to ask him some questions, which you can watch below:

00:00 – What is a Christian doing trying to tell atheists how to be better atheists?

01:05 – Are the popular atheists of today different from the ones you first encountered when you were in undergraduate school?

02:31 – Do you view the “new atheists” as writing with a hyper-confidence that wasn’t present among previous generations of atheists?

03:25 – How long have atheists used science to argue against Christianity?

05:56 – How did you come to faith and become interested in apologetics?

09:38 – What do you mean when you say you are a “skeptic”?

10:52 – In what ways do atheists misuse science and skepticism in their attacks against Christianity?

12:15 – In what ways is someone like Richard Dawkins wrong about the black and white nature of science?

16:53 – What’s the difference between science and scientism?

18:40 – How does morality fit into the typical atheistic worldview?

21:10 – How would you respond to an atheist who says, “I have a morality and can behave morally”?

22:04 – What do you hope will happen to the skeptic who decides to read your book?

For endorsements, table of contents, and an excerpt of the book, go here.

March 16, 2016

An Interview with Thomas Kidd on American Colonial History

Thomas Kidd, distinguished professor of history at Baylor University, is a prolific author. He has now written standard works on the religious history of the American revolution and on the Great Awakening, has explored the history of Baptists in America and the history of evangelical interactions with Muslims in America, and has also composed well-received biographies of Patrick Henry and George Whitefield, He is currently working on a religious biography of Benjamin Franklin.

Thomas Kidd, distinguished professor of history at Baylor University, is a prolific author. He has now written standard works on the religious history of the American revolution and on the Great Awakening, has explored the history of Baptists in America and the history of evangelical interactions with Muslims in America, and has also composed well-received biographies of Patrick Henry and George Whitefield, He is currently working on a religious biography of Benjamin Franklin.

His latest book, just published by Yale University Press, is on American Colonial History: Clashing Cultures and Faiths.

He recently answered a few questions I had about the book’s focus and purpose.

What is the timeframe and geographical frame covered in American Colonial History?

What is the timeframe and geographical frame covered in American Colonial History?

The book goes way, way back in time, to the beginning of human settlement in the Americas. But the bulk of it covers the period from the start of European colonization in the Americas (Columbus’s journey in 1492) to the end of the Seven Years’ War in 1763. In the epilogue, I look forward to the imperial crisis that led to the American Revolution.

The geographical frame is mostly the future United States, but I also consider the European and African backgrounds of voluntary and forced immigration to the New World. I also take into account the early American west, which often gets less attention than England’s thirteen Atlantic seaboard colonies. The book concludes, for example, with a comparison of what was happening in Philadelphia, St. Louis, and San Francisco in 1776. From the vantage point of the center of the continent, or the far west, the Revolution looks a lot different.

You are known for writing books that are popular both inside and outside of the classroom. What are the various audiences you envisioned as you wrote this book?

Yale University Press commissioned me to write this book as an overview of American colonial history. So it definitely has relevance to history courses on that topic. But, knowing that many people read my books who are already out of college, I try to tell the kinds of stories that general audiences enjoy. But of course, that style of writing works well with students, too.

At the end of each chapter you reprint selected relevant primary texts. Why is it important for us to hear early Americans in their own voices rather than merely to have a historian quote and interpret them for us? Does a particular example stand out to you among the documents you chose to include?

The documents lead us into the past in raw, unfiltered ways that historians can’t do. Sometimes historical documents seem inaccessible because they use unfamiliar or confusing language, but that’s the point: the past is like a foreign country, as they say.

There are tons of fascinating, and sometime troubling, details in the documents. I love the testimonies of Native American converts from John Eliot’s Tears of Repentance (1653). Eliot was the most influential Puritan missionary to Native Americans, and he recorded the personal accounts of Native Americans who accepted Christ.

One man named Waban said that before he heard of the Christian God, he wanted to be a witch or a shaman. But when he heard the Christian message, he began to realize his sin and need for forgiveness. “Only Christ can help me,” he confessed.

But—and here you see the cultural gulf between Native Americans and the English missionaries—some of the English were not sure that Waban fully understood the gospel. They said his testimony was “not so satisfactory as was desired,” because Waban could not articulate all of the Christian message. Many Puritans were ambivalent about whether to admit such native converts to full church membership.

There are a number of textbooks on the market for those teaching the history of colonial America. What makes your contribution distinct?

There are three features that make my book different.

One is that I use a writing style and compelling stories that will hopefully make the book enjoyable for more readers.

Second, the book is more focused than many sprawling textbooks. I zero in on themes of religion and conflict, showing that all groups brought religious beliefs with them into the colonial clashes, beliefs which helped them to make sense of the unsettled, violent world in which they lived.

Finally, the book is based on my reading of the most up-to-date scholarship in the history of early America, but is presented in such a way that readers don’t have to sift through the scholarly debates (which can be arcane) themselves.

As a historian, what are some of the challenges in reconstructing the religious beliefs of groups like early Native Americans and Africans?

Many of the people living in Native American or African societies before European colonization did not have written languages, or at least they left few documents that have survived. Therefore, we must piece those cultures together through oral traditions and the tools of archaeology and anthropology.

Early Native Americans and Africans lived in pervasively religious worlds. In some ways, their worlds were even more suffused with religion than the Europeans’ were.

For Native Americans, in particular, we might say that they were spiritual, but not doctrinal. They had religious leaders, but their religions were more about interacting with and appeasing spiritual powers than teaching any particular doctrines about God, or the “gods.” They typically did not have a word in their language for”religion.” To them, religion was just the stuff of everyday life.

Native Americans and Africans often believed that the world was teeming with spiritual forces, and that a wise person would be careful to respect and never to offend those forces. Europeans in the Age of Exploration had pervasively religious worldviews, too, but they understood religion as having more to do with institutions, churches, and doctrines.

So how, as a Christian scholar, did you handle the fact that Christian Europeans often treated Native Americans and Africans so badly?

As a Christian, I reject the idea promoted by many secular scholars that the coming of Christianity was an exclusively negative development for Native Americans and Africans. But one of the book’s biggest challenges was to explain how deeply connected Christianity was with the spread of European empires, and with the rise of slavery in America.

Much evil was done in the name of Christianity during the colonial era. (Some Christian critics even said so at the time.) When given the chance, Africans and Native Americans could treat people in awful ways, too. But Europeans had the most power to colonize and conquer. Still, I believe that many Africans and Native Americans in early America genuinely found hope and salvation in the Christian gospel. That reality helps to account for the persistence of Native American, African, and African American Christianity today.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers