Justin Taylor's Blog, page 144

August 6, 2013

Rodney Stark: Membership in Local Churches Is Now at an All-Time High in America

From an interview with Baylor University sociologist Rodney Stark:

We’ve heard a great deal in the past year about the rise of the “Nones.” According to reports, about 20% of Americans, the highest percentage ever, tell surveyors that they have no religious affiliation. Yet in America’s Blessings you note that 70% of Americans, also the highest percentage in our history, belong to religious congregations. What explains these two, apparently contradictory, developments?

First of all, few of the “Nones” aren’t religious. Most of them even pray. What they mean when they say “None” is that they do not belong to a specific church.

As for the increase in their numbers over the past 20 years, that probably is mostly caused by the decline in the percentage of Americans willing to take part in a survey. Those who do are very disproportionately the less affluent and less educated. Believe it or not, repeated studies going back to the 1940s always show that this is the group least likely to belong to a local church—the more educated Americans are the more religious segment (excluding PhDs).

Meanwhile, partly because Americans move less often than they used to, and many more remain in their home towns as adults, membership in local churches has been rising—now estimated at 70 percent, the all-time high.

You can read the whole thing here.

Kevin Vanhoozer on Biblical Scholarship and Communion with God

Kevin Vanhoozer’s stimulating essay, “Interpreting Scripture between the Rock of Biblical Studies and the Hard Place of Systematic Theology: The State of the Evangelical (Dis)union,” can be found in Renewing the Evangelical Mission, ed. Richard Lints (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2013), 201-225.

One of the wonderful things about Vanhoozer is that his writing is both creative and insightful. For example, here is he writing on the frustrations of scholarly specialization:

Scholars know deep down that they can and should do better than stay within the confines of their specializations:

For I have the desire to do what is right, but not the ability to carry it out.

For I do not do the interpretive good I want, but the historical-criticism or proof-texting I do not want is what I keep on doing.

Now if I do what I do not want, it is no longer I who do it, but interpretive habits that have been drilled into me.

Wretched reader that I am!

Who will deliver me from this body of secondary literature?

Thanks be to God, there is a way forward: the way, truth, and life of collaboration in Christ, where sainthood and scholarship coexist, and where theological exegesis and exegetical theology are mutually supportive and equally important. (pp. 218-219)

Other notable and quotable examples include:

The challenge is to read the Bible in such a way that we neither learn merely about it (as in much biblical scholarship) nor merely use it to substantiate our doctrinal claims (as in much systematic theology) but rather learn from it in order to be changed by it. (p. 218)

Or:

Understanding without communion is empty; communion without understanding is blind. (p. 219)

Or:

Biblical reasoning is father to the Christian imagination, the means of viewing our world in terms of the strange new world of the Bible. (p. 219)

Or:

To Sir Edwyn Hoskyn’s rhetorical question, “Can we bury ourselves in a lexicon, and arise in the presence of God?” we may respond with a resounding “Yes!” It begins with a belief that God speaks to us in and through the human words of the Bible. (p. 223)

Or:

What if they laugh at us? So what? Let us continue to uphold standards of research and protocols of argument. Evangelicals, of all scholars, should display the intellectual virtues without which academic debate degenerates into grandstanding or mud-slinging. Intellectual humility, patient study, honest, and consistency: against such things there is no law. (p. 223)

Or:

The pastor-theologian should be evangelicalism’s default public intellectual, with preaching the preferred public mode of theological interpretation of Scripture. (p. 224)

The entire essay is well worth reading. The heart of his proposal includes ten theses on theological interpretation of Scripture. “The ten theses are arrange in five pairs: the first term in each pair is properly theological, focusing on some aspect of God’s communicative agency; the second draws out its implications for hermeneutics and biblical interpretation.”

The nature and function of the Bible are insufficiently grasped unless and until we see the Bible as an element in the economy of triune discourse.

An appreciation of the theological nature of the Bible entails a rejection of a methodological atheism that treats the texts as having a “natural history” only.

The message of the Bible is “finally” about the loving power of God for salvation (Rom. 1:16), the definitive or final gospel Word of God that comes to brightest light in the word’s final form.

Because God acts in space-time (of Israel, Jesus Christ, and the church), theological interpretation requires thick descriptions that plumb the height and depth of history, not only its length.

Theological interpreters view the historical events recounted in Scripture as ingredients in a unified story ordered by an economy of triune providence.

The Old Testament testifies to the same drama of redemption as the New, hence the church rightly reads both Testaments together, two parts of a single authoritative script.

The Spirit who speaks with magisterial authority in the Scripture speaks with ministerial authority in church tradition.

In an era marked by the conflict of interpretations, there is good reason provisionally to acknowledge the superiority of catholic interpretation.

The end of biblical interpretation is not simply communication—the sharing of information—but communion, a sharing in the light, life, and love of God.

The church is that community where good habits of theological interpretation are best formed and where the fruit of these habits are best exhibited. (pp. 211-214)

What a rich essay!

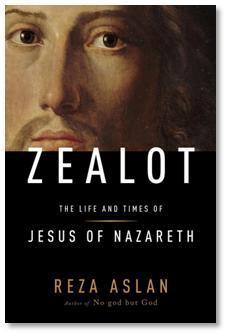

Reviewing Aslan’s “Zealot”

The New Yorks Times #1 bestseller right now is Reza Aslan’s new book, Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth (Random House, 2013).

The New Yorks Times #1 bestseller right now is Reza Aslan’s new book, Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth (Random House, 2013).

It recently recently a publicity boost from an awkward interview, which Joe Carter analyzes here. (But amidst the hub-bub about the interview, which focused on why a Muslim would write a book on Jesus, Joe wonders why people aren’t snickering at Dr. Aslan himself, who seems to be more of an amateur historian—with no teaching experience on, or peer-reviewed academic articles about, historical Jesus research—who is implying that he is an expert in the field. As Alan Jacobs notes, “Reza Aslan’s book is an educated amateur’s summary and synthesis of a particularly skeptical but quite long-established line of New Testament scholarship, presented to us as simple fact. If you like that kind of thing, Zealot will be the kind of thing you like.”)

Ross Douthat has a good post on the book, and Mike Bird will be reviewing the book for TGC.

The Good Book Company Blog also has a review by Gary Manning Jr., associate professor of New Testament at Biola University’s Talbot School of Theology.

Here’s the conclusion:

Finally, despite his generally good understanding of the field, Aslan makes a number of significant errors. I took pages of notes just on historical and linguistic errors in Zealot. Here are only a few examples of significant scholarly errors:

use of Greek definitions not found in any standard Greek lexicon;

using the wrong Greek lexicon for the New Testament;

incorrect definition of the targumim;

unawareness of the evidence for high literacy in ancient Israel;

unawareness of literary approaches to the gospels;

claims that violence against foreigners was the only faithful Jewish response;

claims that Pilate crucified “thousands upon thousands” without trial;

very late, unlikely dates for the writing of the four gospels;

claims that ancient people did not understand the concept of history;

claims that Luke was knowingly writing fiction, not history;

claims that Mark does not describe Jesus’ resurrection;

and on and on.In many cases, I had to come to the conclusion that Aslan was just not familiar enough with modern scholarship related to the New Testament.

There are numerous other problems with Zealot, too numerous to address in an already-too-long blog post. Aslan repeatedly presents highly unlikely interpretations of passages in the New Testament, makes little effort to defend those interpretations, then moves on as if he has made his case. Suffice to say this, as others have said before: there is something a little bizarre about using our only historical documents about Jesus (the New Testament) to come to conclusions quite in opposition to those documents. There is a good reason to believe that Jesus claimed to be a divine king and savior who would die and rise again, and would one day return to judge the world: All four gospels, and indeed the entire New Testament, make this claim. You can deny that this claim is true, but it is scholarly folly to deny that Jesus and the early Christians believed it.

You can read the whole thing here.

August 5, 2013

Two Biblical Images of Spiritual Friendship

Michael Haykin:

The Bible uses two consistent images in its representation of friendship.The first is that of the knitting of souls together.

Deuteronomy provides the earliest mention in this regard when it speaks of a ‘friend who is as your own soul’ (Deut. 13:6), that is, one who is a companion of one’s innermost thoughts and feelings. Prominent in this reflection on friendship is the concept of intimacy. It is well illustrated by Jonathan and David’s friendship. For example, in 1 Samuel 18:1 we read that the ‘soul of Jonathan was knit to the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul.’ This reflection on the meaning of friendship bears with it ideas of strong emotional attachment and loyalty. Not surprisingly, the term ‘friend’ naturally became another name for believers or brothers and sisters in the Lord (see 3 John 14).

The second image that the Bible uses to represent friendship is the face-to-face encounter. This is literally the image used for Moses’ relationship to God. In the tabernacle God spoke to Moses ‘face to face, as a man speaks to his friend’ (Exod. 33:11; see also Num. 12:8). The face-to-face image implies a conversation, a sharing of confidences and consequently a meeting of minds, goals and direction. In the New Testament, we find a similar idea expressed in 2 John 12, where the Elder tells his readers that he wants to speak to them ‘face to face.’ One of the benefits of such face-to-face encounters between friends is the heightened insight that such times of friendship produce. As the famous saying in Proverbs 27:17 puts it, ‘Iron sharpens iron, and one man sharpens another.’

—Michael A. G. Haykin, “Spiritual Friendship as a Means of Grace,” The God Who Draws Near: An Introduction to Biblical Spirituality (Darlington, England: Evangelical Press, 2007), 73.

Noah, Why Is Your Mommy White?

Together for Adoption is extending their early-bird registration ($79) for our October 4-5 national conference at Southern Seminary until 11:59pm (PST), Friday, August 16th.

Check out their new Live in the Story website (with its many free resources) and learn more about this year’s T4A conference.

C.S. Lewis: If You Can’t Contextualize Your Theology, Your Thoughts Are Confused

“Our business is to present that which is timeless (that which is the same yesterday, today, and tomorrow) in the particular language of our own age. . . .

We must learn the language of our audience. And let me say at the outset that it is no use at all laying down a priori what the “plain man” does or does not understand. You have to find out by experience. . .

You must translate every bit of your Theology into the vernacular. This is very troublesome and it means you can say very little in half an hour, but it is essential.

It is also the greatest service to your own thought. I have come to the conviction that if you cannot translate your thoughts into uneducated language, then your thoughts were confused. Power to translate is the test of having really understood one’s own meaning. A passage from some theological work for translation into the vernacular ought to be a compulsory paper in every Ordination examination.”

—C. S. Lewis, “Christian Apologetics” [1945], in God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1970), 96.

August 3, 2013

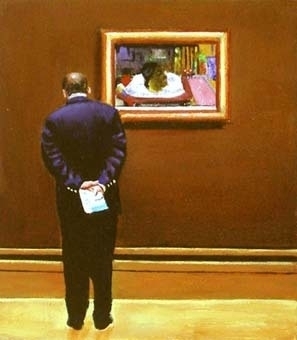

How to Look at a Painting

From a helpful post by Fred Sanders:

From a helpful post by Fred Sanders:

Even more awkward is the moment when you encounter a painting that grips you. For some reason it stands out from the crowd of images you’ve already seen and makes a powerful connection. You like it. It moves you. You’ve seen something new and interesting here. But after about 90 seconds, you have to admit that you don’t really know what to do next.

Other people are standing in front of paintings for five or ten minutes at a stretch, just loooooooking. What are they spending so much time looking at? You really can’t imagine what it is you’re supposed to be doing with your eyes: Blinking? Looking at all four of the corners? Should you hold your thumb up to it? Should you tell yourself a little story about the picture, or pretend you’re a character in it? Count the toes on the people in it to see if the artist messed up? Do I put my hands in my pockets or behind my back while I’m looking? What are the rules? Just what is it that you could be doing if you want to extend this art experience and get more out of a painting that you already like?

A similar question often occurs to me at classical music concerts when I inevitably lose my ability to concentrate on the music and find myself being tossed around on a sea of notes. “Listen more gooder,” I tell my musically illiterate self, but for the life of me, all I can hear is “notes go up, notes go down; notes go up, notes go down.” Over the years, I’ve asked friends and wives (okay, one wife) for helpful hints that can keep me oriented during a long concert.

He continues:

For museum trips, I have tapped into my training as a visual artist and come up with the following eight tips for how to get more insight into a painting. Try these out next time you’re standing in front of a painting wondering how to make the most of it.

The first three tips help you see the things about the painting that are, paradoxically, too obvious for you to notice. To bring these things to your attention, you need to temporarily turn off some of your mind’s habitual tendency to recognize and label what it sees. You didn’t notice it happening, but by the time you’re standing there thinking about an image, your unconscious mind had already run the image through all sorts of perceptual grids and decided to help you ignore a great deal of the information. Your first three steps, therefore, are backward steps, giving your eyes a chance to reclaim some of that information from your necessary habits of rapidly simplifying all visual experience.

Here are the first three:

1. Squint at it.

2. Flip it over.

3. Find the negative space.

Then here are the next three, which “move from recapturing easily ignored information to analyzing what you’re seeing.”

4. Define the moment.

5. Re-Construct it.

6. Let the artist guide your eyes.

Then the final two, which “re-engage your understanding at the level of representation, narration, and interpretation. Notice that the next two steps encourage you to label things, identify them, describe them, and analyze them in light of other knowledge you have. These are great things to do, but frankly they’re the two things you were most likely to do anyway. They’ll mean a lot more after the first six.”

7. Say what you see.

8. Use background knowledge.

You can read the whole thing here.

August 2, 2013

Would You Know a Revival If You Saw One?

J. I. Packer:

Would we recognize a reviving of religion if we were part of one?

I ask myself that question. For more than half a century the need of such reviving in the places where I have lived, worshiped, and worked has weighed me down.

I have read of past revivals. I have learned, through a latter-day revival convert from Wales, that there is a tinc in the air, a kind of moral and spiritual electricity, when God’s close presence is enforcing his Word.

I have sat under the electrifying ministry of the late Martyn Lloyd-Jones, who as it were brought God into the pulpit with him and let him loose on the listeners. Lloyd-Jones’s ministry blessed many, but he never believed he was seeing the revival he sought.

I have witnessed remarkable evangelical advances, not only academic but also pastoral, with churches growing spectacularly through the gospel on both sides of the Atlantic and believers maturing in the life of repentance as well as in the life of joy.

Have I seen revival? I think not—but would I know? From a distance, the difference between the ordinary and extraordinary working of God’s Spirit looks like black and white, a difference of kind; to Edwards, however, at close range, it appeared a matter of degree, as his Narrative and his Brainerd volume (to look no further) make clear.

Some evangelicals need to be asked, Are you not expecting too little from God in the way of moral transformation?

But others need to be asked, Are you not expecting too much from God in the way of situational drama?

Do we always know when we are in a revival situation?

—J. I. Packer, “The Glory of God and the Reviving of Religion: A Study in the Mind of Jonathan Edwards,” in A God-Entranced Vision of All Things: The Legacy of Jonathan Edwards, ed. John Piper and Justin Taylor (Wheaton: Crossway, 2004), 107-108.

When Our Light Obscures God’s Stars

Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855):

When the prosperous man on a dark but starlit night drives comfortably in his carriage and has the lanterns lighted, aye, then he is safe, he fears no difficulty, he carries his light with him, and it is not dark close around him.

But precisely because he has the lanterns lighted, and has a strong light close to him, precisely for this reason, he cannot see the stars. For his lights obscure the stars, which the poor peasant, driving without lights, can see gloriously in the dark but starry night.

So those deceived ones live in the temporal existence: either, occupied with the necessities of life, they are too busy to avail themselves of the view, or in their prosperity and good days they have, as it were, lanterns lighted, and close about them everything is so satisfactory, so pleasant, so comfortable—but the view is lacking, the prospect, the view of the stars.

—Søren Kierkegaard, The Gospel of Suffering, trans. David F. Swenson and Lillian Marvin Swenson (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1948), 123.

August 1, 2013

The Role of the Imagination in Good Preaching

What do we mean by “imagination”? Our dictionaries give a series of definitions. Common to them all seems to be the ability to “think outside of oneself,” “to be able to see or conceive the same thing in a different way.” In some definitions the ideas of the ability to contrive, exercising resourcefulness, the mind’s creative power, are among the nuanced meanings of the word.

Imagination in preaching means being able to understand the truth well enough to translate or transpose it into another kind of language or musical key in order to present the same truth in a way that enables others to see it, understand its significance, feel its power—to do so in a way that gets under the skin, breaks through the barriers, grips the mind, will, and affections so that they not only understand the word used but feel their truth and power.

Luther did this by the sheer dramatic forcefulness of his speech.

Whitefield did it by his use of dramatic expression (overdid it, in the view of some).

Calvin—perhaps surprisingly—did it too by the extraordinarily earthed-in-Geneva-life language in which he expressed himself.

So an overwhelming Luther-personality, a dramatic preacher with Whitefieldian gifts of story-telling and voice (didn’t David Garrick say he’d give anything to be able to say “Mesopotamia” the way George Whitefield did?), a deeply scholarly, retiring, reluctant preacher—all did it, albeit in very different ways. They saw and heard the word of God as it might enter the world of their hearers and convert and edify them.

What is the secret here? It is, surely, learning to preach the word to yourself, from its context into your context, to make concrete in the realities of our lives the truth that came historically to others’ lives. This is why the old masters used to speak about sermons going from their lips with power only when they had first come to their own hearts with power.

. . . Only immersion in Scripture enables us to preach it this way. Therein lies the difference between preaching that is about the Bible and its message and preaching that seems to come right out of the Bible with a “thus says the Lord” ring of authenticity and authority.

—From Ferguson’s article, “A Preacher’s Decalogue,” which contains a great deal of wise advice.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers