Justin Taylor's Blog, page 146

July 26, 2013

The Friendship of Tolkien and Lewis

I am looking forward to the Desiring God National Conference on C.S. Lewis, including the talk by Colin Duriez on “The Friendship of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien.” (Duriez is the author of the book, Tolkien and C.S. Lewis: The Gift of Friendship.) The two gifted friends were uniquely encouraging to each other both professionally and personally (Tolkien played a key role in Lewis’s conversion; Lewis acted as a literary midwife of sorts for The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings)—but sadly, the two men eventually had a falling out.

Christopher Mitchell (of the Torrey Honors Institute of Biola University) has given a lecture on “Lewis and Tolkien: Scholars and Friends”:

What Does “Inerrancy” Mean?

The word inerrant means that something, usually a text, is “without error.” The word infallible—in its lexical meaning, though not necessarily in theological discussions due to Rogers and McKim—is technically a stronger word, meaning that the text is not only “without error” but “incapable of error.” The historic Christian teaching is that the Bible is both inerrant and infallible. It is without error (inerrant) because it is impossible for it to have errors (infallible).

In his chapter on “The Inerrancy of Scripture” in The Doctrine of the Word of God (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2010), John Frame offers some important distinctions and clarifications on the doctrine. He points out that inerrancy suggests to many the idea of precision, rather than its lexical meaning of mere truth.

Frame points out that “precision” and “truth” overlap in meaning but are not synonymous:

A certain amount of precision is often required for truth, but that amount varies from one context to another. In mathematics and science, truth often requires considerable precision. If a student says that 6+5=10, he has not told the truth. He has committed an error. If a scientist makes a measurement varying by .0004 cm of an actual length, he may describe that as an “error,” as in the phrase “margin of error.”

Frame then reminds us that truth and precision are usually more distinct when we move outside the fields of mathematics and science:

If you ask someone’s age, the person’s conventional response (at least if the questioner is entitled to such information!) is to tell how old he was on his most recent birthday. But this is, of course, imprecise. It would be more precise to tell one’s age down to the day, hour, minute, and second. However, would that convey more truth? And, if one fails to give that much precision, has he made an error? I think not, as we use the terms truth and error in ordinary language. If someone seeks to tell his age down to the second, we usually say that he has told us more than we want to know. The question, “What is your age?” does not demand that level of precision. Indeed, when someone gives excess information in an attempt to be more precise, he actually frustrates the process of communication, hindering rather than communicating truth. He buries his real age under a torrent of irrelevant words.

Similarly, when I stand before a class and a student asks me how large the textbook is. Say that I reply “400 pages,” but the actual length is 398. Have I committed an error, or told the truth? I think the latter, for the following reasons: (a) In context, nobody expects more precision than I gave in my answer. I met all the legitimate demands of the questioner. (b) “400,” in this example, actually conveyed more truth than “398″ would have. “398″ most likely would have left the student with the impression of some number around 300, but “400″ presented the size of the book more accurately.

The relationship between “precision” and “error,” Frame says, is actually more complicated than many recognize. “What is an error?” sounds like a simple question with an easy-to-find answer. But “identifying an error requires some understanding of the linguistic context, and that in turn requires an understanding of the cultural context.”

A child who says in his math class that 6+5=10 may not expect the same tolerance as a person who gives a rough estimate of his age or a professor who exaggerates the size of a book by two pages.

We should always remember that Scripture is, for the most part, ordinary language rather than technical language. Certainly, it is not of the modern scientific genre. In Scripture, God intends to speak to everybody. To do that most efficiently, he (through the human writers) engages in all the shortcuts that we commonly use among ourselves to facilitate conversation: imprecisions, metaphors, hyperbole, parables, etc. Not all of these convey literal truth, or truth with a precision expected in specialized contexts; but they all convey truth, and in the Bible there is no reason to charge them with error.

How then does inerrancy relate to precision? Frame suggests “sufficient precision” as opposed to “maximal precision.”

Inerrancy, therefore, means that the Bible is true, not that it is maximally precise. To the extent that precision is necessary for truth, the Bible is sufficiently precise. But it does not always have the amount of precision that some readers demand of it. It has a level of precision sufficient for its own purposes, not for the purposes for which some readers might employ it.

Frame then introduces an important aspect of propositional language: it “makes claims on its hearers”:

When I say that the book is on the table, I am claiming that in fact the book is there. If you look, you will find it, precisely there. But if I say that I am age 24 (do I wish!), I am not claiming that I am precisely 24. I am claiming, rather, that I became 24 on my last birthday. Moreover, if I say, as in the previous example, that there are 400 pages in a textbook, I am not claiming that there is precisely that number of pages, only that the number 400 gives a pretty reliable estimate of the size of the book. Of course, if I worked for a publisher, and gave him an estimate of the size of the book that was two pages off, I could cost him a lot of money and myself a job. In that context, my imprecision would certainly be called an error. However, in the illustration of the professor making an estimate before his class, it would have been inappropriate to say that he was in error. Even though I use the same language in the two situations, I am making a different claim in the first situation from the claim I make in the second. Therefore, the amount of precision demanded and expected in one case is different from what is demanded and expected in the other. In the one case, I have made an error; in the other case not.

Frame points out that a “claim” in this sense can be explicit or implicit.

If someone asks me to quote a Bible passage, and I say “this is inexact,” I am making an explicit claim, namely, “I will give you the gist of it, but not the exact words.” Nevertheless, it is rare in language for someone to make his claims explicit in that way. When a person gives his age, he rarely says, “I am giving you an approximate figure.” Rather, he simply accepts the custom of approximating one’s age by the last birthday, assuming that people will understand that custom and will not be misled into thinking that his answer is absolutely precise. In following this custom, people understand that he is making an implicit claim.

Frame applies this principle to the biblical language and world:

So, in reading the Bible, it is important to know enough about the language and culture of the people to know what claims the original characters and writers were likely making. When Jesus tells parables, he does not always say explicitly that his words are parabolic. But his audience understood what he was doing, and we should as well. A parable does not claim historical accuracy, but it claims to set forth a significant truth by means of a likely nonhistorical narrative.

This leads to Frame’s definition of inerrancy:

So, I think it is helpful to define inerrancy more precisely (!) by saying that inerrant language makes good on its claims. When we say that the Bible is inerrant, we mean that the Bible makes good on its claims.

Now many writers have enumerated what are sometimes called qualifications to inerrancy: inerrancy is compatible with unrefined grammar, non-chronological narrative, round numbers, imprecise quotations, pre-scientific phenomenalistic description (e.g., “the sun rose”), use of figures and symbols, imprecise descriptions (as Mark 1:5, which says that everyone from Judea and Jerusalem went to hear John the Baptist). I agree with these points, but I do not describe them as “qualifications” of inerrancy. These are merely applications of the basic meaning of inerrancy: that it asserts truth, not precision. Inerrant language is language that makes good on its own claims, not on claims that are made for it by thoughtless readers.

The Fear of the Lord Is Still the Beginning of Wisdom (Even Though Evangelicals Almost Never Talk about It)

Jerry Bridges, author of one of the few contemporary books on the fear of the Lord, explains what it means:

July 25, 2013

Tolkien on Video and in His Own Voice

Since I posted on the existing audio of C. S. Lewis, I thought I’d do the same for Tolkien. Except he was also captured on film.

For the full audio, the CD to get is The J.R.R. Tolkien Audio Collection. Here’s a description:

Of historic note, these selections from The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings are based on a tape recording Tolkien made in 1952, which inspired him to continue his own quest to see his vision in print. Also included is a never-published poem, “The Mirror of Galadriel,” originally intended for inclusion in the trilogy, yet edited out. And, finally, Tolkien’s son, Christopher, reads selections from his father’s The Silmarillion, the epic foundation upon which rests the whole of his work.

Below are materials free online. A few clips from interviews, followed by several readings, recitings by Tolkien of his own material.

First broadcast on BBC 2 on March 30, 1968: “John Izzard meets with JRR Tolkien at his home, walking with him through the Oxford locations that he loves while hearing the author’s own views about his wildly successful high-fantasy novels. Tolkien shares his love of nature and beer and his admiration for ‘trenchermen’ in this genial and affectionate programme. The brief interviews with Oxford students that are dotted throughout reveal the full range of opinions elicited by ‘The Lord of the Rings’, from wild enthusiasm to mild contempt”:

A nearly 10-minute audio interview, broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in January 1971:

Tolkien reads from chapter 5 of The Hobbit:

Tolkien reciting the Ring Verse from “The Shadow of the Past” (LOTR):

Tolkien reading from chapter 4 of The Two Towers:

Tolkien singing “Troll Sat Alone On His Seat Of Stone,” the poem recited by Sam Gamgee in “Flight to the Ford” (LOTR):

Tolkien recites an Entish Chant (LOTR):

Tolkien in 1952 reciting the Quenya poem “Namárië,” sung by Galadriel in the chapter “Farewell to Lórien” (LOTR):

Tolkien recites the poem “The Hoard” from The Adventures of Tom Bombadil:

The Message of the Old Testament in One Sermon

Mark Dever—author of The Message of the Old Testament: Promises Made (foreword by Graeme Goldsworthy), which has a chapter per book of the OT—presents his overview of the entire OT in one talk at a Truth & Life Conference (2013):

What Does It Mean to Be Truly Human?

The latest video from Jefferson Bethke:

Pastoral Bullies

The Apostle Peter exhorts his fellow elders to “shepherd the flock of God that is among you, exercising oversight . . . not domineering over those in your charge, but being examples to the flock” (1 Pet. 5:1, 3).

Sam Storms has an important post on what this can look like in the church:

A man can “domineer” or “lord it over” his flock by intimidating them into doing what he wants done by holding over their heads the prospect of loss of stature and position in the church.

A pastor domineers whenever he threatens them with stern warnings of the discipline and judgment of God, even though there is no biblical basis for doing so.

A pastor domineers whenever he threatens them with public exposure of their sin should they not conform to his will and knuckle under to his plans.

A pastor domineers whenever he uses the sheer force of his personality to overwhelm others and coerce their submission.

A pastor domineers whenever he uses slick verbiage or eloquence to humiliate people into feeling ignorant or less competent than they really are.

A pastor domineers whenever he presents himself as super-spiritual (his views came about only as the result of extensive prayer and fasting and seeking God. How could anyone then possibly disagree with him?).

A pastor domineers whenever he exploits the natural tendency people have to elevate their spiritual leaders above the average Christian. That is to say, many Christians mistakenly think that a pastor is closer to God and more in tune with the divine will. The pastor often takes advantage of this false belief to expand his power and influence.

A pastor domineers whenever he gains a following and support against all dissenters by guaranteeing those who stand with him that they will gain from it, either by being brought into his inner circle or by some form of promotion.

A pastor domineers by widening the alleged gap between “clergy” and “laity.” In other words, he reinforces in them the false belief that he has a degree of access to God which they don’t.

Related to the former is the way some pastors will make it appear that they hold sway or power over the extent to which average lay people can experience God’s grace. He presents himself in subtle (not overt) ways as the mediator between the grace of God and the average believer. In this way he can secure their loyalty for his agenda.

He domineers by building into people a greater loyalty to himself than to God. Or he makes it appear that not to support him is to work at cross purposes with God.

He domineers by teaching that he has a gift that enables him to understand Scripture in a way they cannot. They are led to believe they cannot trust their own interpretive conclusions and must yield at all times to his.

He domineers by short circuiting due process, by shutting down dialogue and discussion prematurely, by not giving all concerned an opportunity to voice their opinion.

He domineers by establishing an inviolable barrier between himself and the sheep. He either surrounds himself with staff who insulate him from contact with the people or withdraws from the daily affairs of the church in such a way that he is unavailable and unreachable.

Related to the above is the practice of some in creating a governmental structure in which the senior pastor is accountable to no one, or if he is accountable it is only to a small group of very close friends and fellow elders who stand to profit personally from his tenure as pastor.

Keep reading the whole thing here.

July 24, 2013

Is Jesus God?

I was once at a conference, talking with some colleagues who had a display at a hotel. A Muslim man approached us, demanding that one of us—just one of us—answer just one question, something no one had ever been able to answer for him. “You say that Jesus is God, right?” I answered in the affirmative. “And you say that God is in heaven, right?” I nodded. “And you say there is only one God, not two?” I smiled, knowing where he was going. “Then how is it,” he said, pointing his finger at me, “that God was talking to God?! It makes no sense at all!”

I asked him if I could ask him a question: “Are you a human being?” Yes, he replied. “Am I a human being?” He nodded. “We are both human but we are not the same person. So the Father and the Son share the same nature of God but are distinct persons.” He unleashed a string of expletives and walked away.

Now my reply was not fully adequate, and the analogy has some severe limitations (as Bob Letham explains in his excellent book on The Holy Trinity), but it at least tries to start the conversation with a distinction between nature and person (which I’ve briefly written about here).

So does the New Testament really teach that Jesus is God? The NT often uses “God” (Greek: theos) as synonymous with “God the Father”— and Jesus is not the Father. But the NT also frequently uses “God” as the more generic term for the divine nature. So “God” is not always a reference to the Son in particular, but the Son is always God.

There are several examples where Jesus is explicitly called God. Here are the clearest ones:

John 1:1, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.”

John 1:18, “No one has ever seen God; the only God, who is at the Father’s side, he has made him known.”

John 20:28, ”Thomas answered him, ‘My Lord and my God!’”

Romans 9:5, ”To them belong the patriarchs, and from their race, according to the flesh, is the Christ who is God over all, blessed forever. Amen.”

Titus 2:13, “waiting for our blessed hope, the appearing of the glory of our great God and Savior Jesus Christ”

Hebrews 1:8, ”But of the Son he says, ‘Your throne, O God, is forever and ever, the scepter of uprightness is the scepter of your kingdom.’”

2 Peter 1:1, ”To those who have obtained a faith of equal standing with ours by the righteousness of our God and Savior Jesus Christ”

But the evidence for Jesus’ divinity is hardly limited to these examples where he is explicitly identified as God. Murray Harris, who wrote a definitive treatment on this question (Jesus as God: The New Testament Use of Theos in Reference to Jesus) has a helpful summary of the broader lines of evidence:

Even if the early Church had never applied the title ['God'] to Jesus, his deity would still be apparent in his being

the object of human and angelic worship and of saving faith;

the exerciser of exclusively divine functions such as creatorial agency, the forgiveness of sins, and the final judgment;

the addressee in petitionary prayer;

the possessor of all divine attributes;

the bearer of numerous titles used of Yahweh in the Old Testament; and

the co-author of divine blessing.

Faith in the deity of Christ does not rest on the evidence or validity of a series of ‘proof-texts’ in which Jesus may receive the title θεός but on the general testimony of the New Testament corroborated at the bar of personal experience.

—Murray J. Harris, “Titus 2:13 and the Deity of Christ,” in Pauline Studies: Essays Presented to F. F. Bruce, ed. Donald A. Hagner and Murray J. Harris (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980), 271.

An excellent book that lays out all of the evidence—going beyond just the New Testament to include the Old Testament, the history of the church, the place of contemporary culture, and the role of missions, is The Deity of Christ , part of the Theology in Community series edited by Christopher Morgan and Robert Peterson.

One of the most accessible books on this topic is Robert Bowman and Ed Komoszewski’s Putting Jesus in His Place: The Case for the Deity of Christ . They provide a helpful way to remember the case for Christ’s divinity through the acronym H.A.N.D.S.

Jesus deserves the Honors only due to God,

Jesus shares the Attributes that only God can possess,

Jesus is given Names that can only be given to God,

Jesus performs Deeds that only God can perform

Jesus possesses a Seat on the throne of God

Finally, it’s worth remember the helpful summary of Jaroslav Pelikan:

The oldest surviving sermon of the Christian church after the New Testament opened with the words: “Brethren, we ought so to think of Jesus Christ as of God, as the judge of living and dead. And we ought not to belittle our salvation; for when we belittle him, we expect also to receive little.”

The oldest surviving account of the death of a Christian martyr contained the declaration: “It will be impossible for us to forsake Christ . . . or to worship any other. For him, being the Son of God, we adore, but the martyrs . . . we cherish.”

The oldest surviving pagan report about the church described Christians as gathering before sunrise and “singing a hymn to Christ as to [a] god.”

The oldest surviving liturgical prayer of the church was a prayer addressed to Christ: “Our Lord, come!”

Clearly it was the message of what the church believed and taught that “God” was an appropriate name for Jesus Christ.

—Jaroslav Pelikan, The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine, Vol. 1: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600) (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971), p. 173; emphasis added.

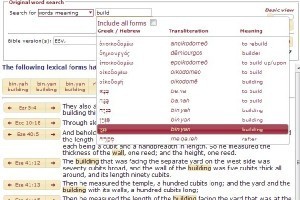

Scripture Tools for Every Person (STEP): A New Free Online Bible Study Resource.

From Tyndale House Cambridge:

From Tyndale House Cambridge:

Today the STEP development team of Tyndale House Cambridge launched the Beta-test version of a new free Bible study resource at www.StepBible.org.

STEP software is designed especially for teachers and preachers who don’t have access to resources such as Tyndale House Library, which specialises in the biblical text, interpretation, languages and biblical historical background and is a leading research institution for Biblical Studies.

The web-based program, which will soon also be downloadable for PCs and Macs, will aid users who lack resources, or who have to rely only on smartphones or outmoded computers.

About STEP

The project began when STEP director Dr David Instone-Brewer created the Tyndale Toolbar for his own use. It became popular among researchers at Tyndale House and is now used by thousands of people across the globe. The Beta launch of STEP invites users to try out the new tools and give suggestions for improvement.

“STEP represents the most comprehensive yet user friendly tool for Bible Study I have seen in over 35 years of research,” said Dr Wesley B. Rose. Tim Bulkeley, a contributor to the project, said “I wish I was just starting to teach in Kinshasa now, with STEP and a smart phone. Students would find learning Hebrew and Greek, to read the Bible directly, so much easier.”

Almost a hundred volunteers worldwide have contributed to this work, including 75 who helped to align the ESV, used with the kind permission of Crossway, with the underlying Greek and Hebrew. All their work will now be freely available for other software projects. There are many exciting features in the pipeline for others to get involved with.

Try it out at www.StepBible.org.

Further information

The special problems of the Majority World have inspired some unique technical solutions. The whole database-driven program is designed to be downloaded onto computers as diverse as decade-old desktops and Android phones. This download, which is still being tested, enables it to continue working when internet access goes down.

Ten language interfaces are available and another 83 are ready for volunteers to work on. Bibles in many languages are already present and agreements are in place with the United Bible Societies and other organisations to add hundreds more. Someone using a Swahili browser can see buttons, menus and Bibles in their own mother-tongue.

Some of the features are unavailable on any other software, and the ease of use belies its extraordinary complexity. Even in Basic View you can get answers to questions like: Which other verses use the same original word found here? This works for every Bible in all the available languages without requiring knowledge of any Hebrew or Greek. In Advanced View one can see multiple interlinear texts with word-by-word alignment in English, Chinese, Hebrew and other languages. Information about grammar and dictionaries is also given at three levels so that someone wanting quick information isn’t overloaded with the complex details, which are also available.

July 23, 2013

A Free Bible App for the Deaf

Faith Comes by Hearing has launched a free Bible app, Deaf Bible.is™ ASL, designed specifically for users whose primary language is American Sign Language. They are also working on other sign languages. Here’s a demo:

Go here for more info on downloading it in the App Store, Google Play, or from Amazon.

HT: John Knight

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers