Justin Taylor's Blog, page 141

August 26, 2013

10 Suggestions for Engaging Our Culture with the Gospel

From Josh Moody of College Church in Wheaton, Illinois:

1. Keep the Main Thing the Main Thing

2. Develop an Ear to Unbiblical Offenses

3. Understand What It Is about the Cross that Offends

4. Realize the Intellectual Shallowness of Most of the Critiques

5. Appreciate, but Don’t Overplay, the Moral Undertone

6. Understand the Rhetorical Power of Love

7. Have a Sanguine, but Realistic, Appreciation of the Limitations of Cultural Change

8. Understand What Is Truly (and What Is Not) Distinct about “Christianity”

9. Read Widely

10. Understand That Our Regular Hearers, Those We Preach to, Are Dealing with This on a Daily Basis Even if We Are Not

Go here to read a brief explanation of each.

How Not to Critique Evangelicalism from Within

Beware lest, even in your description of the problem, your diagnosis fall prey to the very categories of pragmatism that constitute the problem. In other words, don’t bemoan the condition of evangelicalism because it is hollow and therefore weakening—as if the real goal is lasting prominence rather than temporary prominence. Instead, bemoan the condition of evangelicalism because it minimizes the supremacy and centrality of God.

Can You Be a Moral Absolutist If You Think It Sometimes Depends on the Motives and Situation?

Growing up, taking seemingly countless surveys that would provide researchers and pundits with fodder for “What the Youth of America Believe Today,” I never knew how to answer the question, “Do you believe in moral absolutes?” A definition was never provided. And I also wanted to clarifying questions like, “Does belief in absolutism means I can’t acknowledge that the application of moral principles is often person- and situation-specific?”

For some helpful thinking along these lines, here is an excerpt from a transcript of a lecture by Peter Kreeft on moral relativism:

Morality is indeed conditioned, or partly determined, by both situations and motives, but it is not wholly determined by situations or motives.

Traditional common sense morality involves three moral determinants, three factors that influence whether a specific act is morally good or bad. The nature of the act itself, the situation, and the motive. Or, what you do; when, where, and how you do it; and why you do it.

It is true that doing the right thing in the wrong situation, or for the wrong motive, is not good.

Making love to your wife is a good deed, but doing so when it is medically dangerous is not. The deed is good, but not in that situation.

Giving money to the poor is a good deed, but doing it just to show off is not. The deed is good, but the motive is not.

However, there must first be a deed before it can be qualified by subjective motives or relative situations, and that is surely a morally relevant factor too. The good life is like a good work of art. A good work of art requires all its essential elements to be good. For instance, a good story must have a good plot, and good characters, and a good theme. So a good life requires you do the right thing, the act itself; and have a right reason or motive; and that you do it in the right way, the situation.

Furthermore, situations, though relative, are objective, not subjective. And motives, though subjective, come under moral absolutes. They can be recognized as intrinsically and universally good or evil. The will to help is always good, the will to harm is always evil. So even situationism is an objective morality, and even motivationism or subjectivism is a universal morality.

The fact that the same principles must be applied differently to different situations presupposes the validity of those principles. Moral absolutists need not be absolutistic about applications to situations. They can be flexible. But a flexible application of the standard presupposes not just a standard, but a rigid standard. If the standard is as flexible as the situation it is no standard at all. If the yardstick with which to measure the length of a twisting alligator is as twisting as the alligator, you cannot measure with it. Yardsticks have to be rigid.

And moral absolutists need not be judgmental about motives, only about deeds. When Jesus said, “Judge not that ye not be judged,” he surely meant “Do not claim to judge hearts and motives, which only God can know.” He certainly did not mean, “Do not claim to judge deeds. Do not morally discriminate bullying from defending, killing from healing, robbery from charity.” In fact, it is only the moral absolutist, and not the relativist, who can condemn judgmentalism of motive, since he alone can condemn intolerance. The relativist can condemn only moral absolutism.

Why Gray Matters

A book trailer for Brett McCracken’s new book, Gray Matters: Navigating the Space between Legalism and Liberty (Baker, 2013):

Learn more here.

What the the Girl with the Hijab Witnessed in an Anglican Chapel

Carl Trueman recounts an experience of worshipping with his son in the famous Chapel of King’s College, Cambridge, sitting next to a young Spanish woman wearing a hijab.

Yet here is the irony: in this liberal Anglican chapel, the hijabi experienced an hour long service in which most of the time was spent occupied with words drawn directly from scripture. She heard more of the Bible read, said, sung and prayed than in any Protestant evangelical church of which I am aware—than any church, in other words, which actually claims to take the word of God seriously and place it at the centre of its life. Yes, it was probably a good thing that there was no sermon that day: I am confident that, as Carlyle once commented, what we might have witnessed then would have been a priest boring holes in the bottom of the Church of England. But that aside, Cranmer’s liturgy meant that this girl was exposed to biblical Christianity in a remarkably beautiful, scriptural and reverent fashion. I was utterly convicted as a Protestant minister that evangelical Protestantism must do better on this score: for all of my instinctive sneering at Anglicanism and formalism, I had just been shown in a powerful way how far short of taking God’s word seriously in worship I fall.

You can read the whole thing here.

August 23, 2013

A Balanced Word and a Challenge on How We Think about and Use Material Possessions

Craig Blomberg’s Neither Poverty nor Riches: A Biblical Theology of Material Possessions is an invaluable resource for thinking through a theology of what we own and how we are to steward it. I find his exegesis invariably careful and reasonable, though I think he at times imports unwarranted liberal presuppositions into his applications. But one of his concluding words in the book is something all of us should take to heart:

The bottom line is surely one of attitude. Does a discussion of issues like these threaten us, leading to counter-charges about guilt manipulation or to rationalizing our greeds as if they were our needs?

Or are we convicted in a healthy way that leads us to ask what more we can do to divest ourselves of our unused or unnecessary possessions, to make budgets to see where our money is really going, to exercise self-control and delayed gratification out of thanksgiving for all that God has blessed us with that we never deserved?

Are we eager to help others, especially fellow Christians, however undeserving they seem to be?

Are we concerned to expose ourselves widely to news of the world, including news from a distinctively Christian perspective, to have the plight of the impoverished millions not paralyse us but periodically reanimate our commitment to do better and to do more?

We may disagree on models of involvement, on to whom to give and on how much to give, but will we agree to continue to explore possibilities compatible with our economic philosophies and try to determine what really will do the most short-term and long-term good for the most needy?

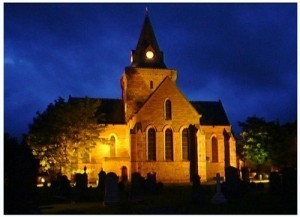

The Hidden Floodlight Ministry of the Holy Spirit

The Holy Spirit’s distinctive new covenant role, then, is to fulfill what we may call a floodlight ministry in relation to the Lord Jesus Christ. So far as this role was concerned, the Spirit “was not yet” (John 7:39, literal Greek) while Jesus was on earth; only when the Father had glorified him (see John 17:1, 5) could the Spirit’s work of making men aware of Jesus’ glory begin.

I remember walking to a church one winter evening to preach on the words “he shall glorify me,” seeing the building floodlit as I turned a corner, and realizing that this was exactly the illustration my message needed.

When floodlighting is well done, the floodlights are so placed that you do not see them; you are not in fact supposed to see where the light is coming from; what you are meant to see is just the building on which the floodlights are trained. The intended effect is to make it visible when otherwise it would not be seen for the darkness, and to maximize its dignity by throwing all its details into relief so that you see it properly. This perfectly illustrates the Spirit’s new covenant role. He is, so to speak, the hidden floodlight shining on the Savior.

Or think of it this way. It is as if the Spirit stands behind us, throwing light over our shoulder, on Jesus, who stands facing us.

The Spirit’s message is never,

“Look at me;

listen to me;

come to me;

get to know me,”

but always

“Look at him, and see his glory;

listen to him, and hear his word;

go to him, and have life;

get to know him, and taste his gift of joy and peace.“

—Keeping in Step with the Spirit: Finding Fullness in Our Walk with God, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2005), p. 57; emphasis original.

August 22, 2013

Colossians 1:15-23

Some Things to Remember about Offering and Receiving Criticism on Twitter (Or Elsewhere)

Here are a few things I try to remember, but am frequently tempted to forget:

Here are a few things I try to remember, but am frequently tempted to forget:

It usually takes very little time to discern whether or not someone is operating as a good-faith critic. Good-faith critics value clarity before agreement (as Dennis Prager has phrased it). They try to understand before they seek to win. Bad-faith critics are like hit-and-run drivers. They play to the crowd—whether conservative or liberal. They can be passive-aggressive—harsh to others but quick to play the victim when challenged.

If the person is not a good-faith critic—humbly open to counter-considerations, striving for fairness, seeking to understand, offering actual arguments—there is little use dialoging. It really is a waste of time, and we are called to be good stewards of the finite amount of time each of us has. Mortimer Adler writes, “You must be able to say, with reasonable certainty, ‘I understand,’ before you can say any one of the following things: ‘I agree,’ or ‘I disagree,’ or ‘I suspend judgment.’” For those who don’t do this, he says: “There is actually no point in answering critics of this sort. The only polite thing to do is to ask them to state your position for you, the position they claim to be challenging. If they cannot do it satisfactorily, if they cannot repeat what you have said in their own words, you know that they do not understand, and you are entirely justified in ignoring their criticisms.”

Even if the person is a good-faith critic, there is little point in trying to have a genuine dialogue 140 characters at a time. Other venues work better. Unless you can point to a longer-form piece that defends your position or offers criticism, it’s often a waste of pixels.

Nevertheless, we should welcome and seriously take to heart good-faith criticism. As Adler says, “When you find the rare person who shows that he understands what you are saying as well as you do, then you can delight in his agreement or be seriously disturbed by his dissent.”

In all of this, Christians should remember to offer and receive criticism Christianly, remembering that our speech should “always be gracious, seasoned with salt” (Col. 4:6), that “by your words you will be justified, and by your words you will be condemned” (Matt. 12:37), that we are to “love one another with brotherly affection; outdo one another in showing honor” (Rom. 12:10); that we are to “let no corrupting talk come out of your mouths, but only such as is good for building up, as fits the occasion, that it may give grace to those who hear” (Eph. 4:29); that we are to “speak the truth in love” (Eph. 4:15, 25); and that we must learn to bridle our tongue so that we do not deceive our heart (James 1:26).

How to Conduct an Interview at a Conference

Matt Regan of Campus Outreach:

Silly Interviews at the Conference! Part II from Campus Outreach on Vimeo.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers