Simon Johnson's Blog, page 6

December 2, 2016

Economics 101, Economism, and Our New Gilded Age

By James Kwak

My new book—Economism: Bad Economics and the Rise of Inequality—is coming out on January 10 (although, of course, you can pre-order it from your local monopoly now). If you’d like more information about the book, the book website is now up at economism.net. (I used Medium instead of WordPress.com this time.) The post below, which is also the top story on the book website, summarizes the main themes of the book.

Income inequality is at levels not seen for a century. Many working families are struggling to get by, only kept afloat by Medicaid and food stamps. The federal minimum wage is just $7.25 per hour—below the poverty line even for a family of two. The bright outlook for corporate profits has driven the S&P 500 to record levels. Surely it makes sense to raise the minimum wage, forcing companies to dip into those profits to pay their workers a bit more.

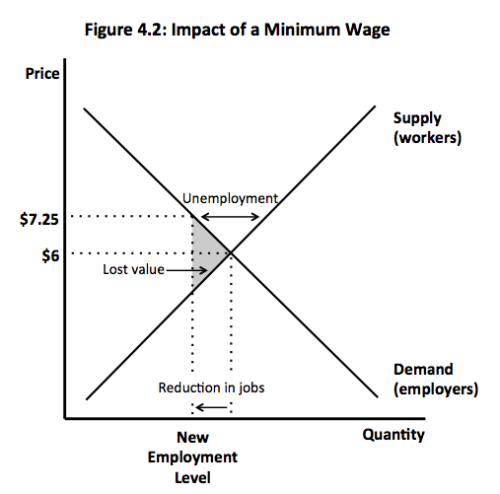

But that’s not what you learn in Economics 101. The impact of a minimum wage is blissfully easy to model using the supply-and-demand diagram that dominates first-year economics courses.

A price floor in the labor market—that’s what a minimum wage is—causes demand to exceed supply. The difference is unemployment, and the reduction in the employment level represents value lost by society. People who want the minimum wage are well-meaning but muddle-headed do-gooders who don’t understand economics. As Milton Friedman wrote in Capitalism and Freedom, “minimum wage laws are about as clear a case as one can find of a measure the effects of which are precisely the opposite of those intended by the men of good will who support it.”

That’s what Economics 101 teaches you—but it’s not what many economists actually think.

Economists polled by the Chicago Booth School of Business are evenly split on whether an increase in the minimum wage to $9—or even $15—would significantly increase unemployment. Professional opinion is divided exists because detailed empirical research is inconclusive, with several recent studies (e.g., Dube, Lester, and Reich 2010 and 2014) and meta-studies (Doucouliagos and Stanley, Belman and Wolfson) showing no significant impact on employment.

In policy debates and public relations campaigns, however, what you are more likely to hear is that a minimum wage must increase unemployment—because that’s what the model says. This conviction that the world must behave the way it does on the blackboard is what I call economism. This style of thinking is influential because it is clear and logical, reducing complex issues to simple, pseudo-mathematical axioms. But it is not simply an innocent mistake made by inattentive undergraduates. Economism is Economics 101 transformed into an ideology—an ideology that is particularly persuasive because it poses as a neutral means of understanding the world.

In the case of low-skilled labor, it’s clear who benefits from a low minimum wage: the restaurant and hotel industries. In their PR campaigns, however, these corporations can hardly come out and say they like their labor as cheap as possible. Instead, armed with the logic of supply and demand, they argue that raising the minimum wage will only increase unemployment and poverty. Similarly, megabanks argue that regulating derivatives will starve the real economy of capital; multinational manufacturing companies argue that new trade agreements will benefit everyone; and the wealthy argue that lower taxes will increase savings and investment, unleashing economic growth.

In each case, economism allows a private interest to pretend that its preferred policies will really benefit society as a whole. The usual result is to increase inequality or to legitimize the widening gulf between rich and poor in contemporary society.

I became aware of the subtle power of economism during the 2009–2010 financial reform debate, when bank lobbyists invoked economic logic to protect their clients’ profits from new regulations. As far as I can recall, I first wrote about it in a 2011 blog post titled “The Smugness of Unintended Consequences.” My new book, Economism: Bad Economics and the Rise of Inequality, offers an intellectual history of the rise of economism in the late twentieth century, case studies of its impact in several different policy domains, and—I hope—the tools to enable readers to understand both the merits and the limitations of arguments based on Economics 101. Because the first step in overcoming an ideology is understanding how it works.

November 30, 2016

The Deduction Fairy

By James Kwak

Incoming Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin promised a big tax cut for corporations and the “middle class,” but not for the rich. “Any tax cuts for the upper class will be offset by less deductions that pay for it,” he said on CNBC.

This is impossible.

The tax cutting mantra comes in two forms. The more extreme one claims that reducing the overall tax burden on the rich will turbocharge the economy because they will save more, increasing investment, and will also work more, starting companies and doing all those other wonderful things that rich people do. The less extreme version is that we should lower tax rates to reduce distortions in the tax code, but we can maintain the current level of taxes paid by the rich by eliminating those famous “loopholes and deductions.” Donald Trump the candidate stuck with the former: his tax proposal, as scored by the Tax Policy Center, gave 47% of its total tax cuts to the top 1%, who also enjoyed by far the largest reduction in their average tax rate.

Mnuchin’s comment implies that he favors the latter version: lowering rates but making it up by “broadening the base.” This math might work for the merely rich—say, families making $200,000–400,000 per year. Take away the mortgage interest tax deduction, the deduction for retirement plan contributions, and the exclusion for employer-provided health care—which together can easily shield $50–75,000 in income—and you could probably fund several percentage points of rate decreases. (Of course, it would be politically impossible to completely eliminate those tax breaks, but that’s another story.)

When it comes to the truly rich, however, there just aren’t enough deductions out there to eliminate. You can only deduct interest on a mortgage up to $1 million. The fanciest employer-provided family health plan isn’t worth more than $30,000 or so. The aggregate limit for employer retirement plan contributions is around $50,000. At the top end of the wealth hierarchy, where people make millions or tens of millions of dollars per year, these are rounding errors; eliminating these deductions wouldn’t even make up for a reduction in tax rates of a single percentage point.

There are some tax breaks that matter for very rich families. Only one is technically a deduction: the deduction for charitable contributions. But obviously that only affects (to a significant degree) a small number of wealthy people in any given year, and those people can work around any limits in this deduction by simply cutting back on donations. (By contrast, if you get rid of the exclusion for employer-provided health care, employees won’t respond by foregoing health care altogether.)

The biggest tax breaks for the very rich (as I’ve written about before) are the preferential tax rate for capital gains, the deferral of taxes on those gains until you sell the assets, and the step-up in basis at death (which means that, if you pass on assets to your children, no one ever pays tax on the appreciation during your lifetime). Given that Republicans have been trying to reduce capital gains tax rates for decades (with Paul Ryan occasionally saying they should be zero), we can be sure that preferential rates aren’t going away. Taxing gains in assets when accrued is also certain not to happen. Trump has in the past supported a version of eliminating step-up in basis at death, but that was along with slashing tax rates and getting rid of the estate tax, which would be a net win for the wealthy.

In short, the idea that you can reduce tax rates without reducing the tax burden at the top end of the income distribution is a fantasy on par with the idea that you can increase tax revenue by raising rates—plausible in theory but impossible given current reality. That Mnuchin is taking this line is simply evidence that the Trump administration will try to reconcile a massive tax cut for the rich with their fake-populist rhetoric for as long as possible. In the end, we know which one will win out.

November 17, 2016

What You Can Do

By James Kwak

Several of my friends, some of whom I haven’t spoken with in a long time, have reached out to me over the past week to discuss what to make of last week’s election. I imagine this is happening with a lot of people.

Although I don’t have any simple answers, I do have some thoughts on what we can do in response to the prospect of Donald Trump and the Republicans controlling the entire federal government, as well as a large majority of states. But first, we need a short detour—for a bit of perspective.

Maurice Walker is a fifty-five-year-old man with schizophrenia whose only income is $530 per month in Social Security disability payments. On September 3, 2015, he was arrested by police in Calhoun, Georgia for being a “pedestrian under the influence”—something many of us have been guilty of at one time or another. If Walker had been able to come up with $160 (something most people reading this blog could do in seconds), he would have walked free. Instead, he was locked up in jail, without his medication.

The City of Calhoun has a fixed bail schedule, in which the amount of bail is set for each offense, without regard for ability to pay. People arrested for misdemeanors cannot see a judge until the next Monday court session (which would have been eleven days for Walker, because the next Monday was Labor Day). This means that, among those arrested on the same charges, poor people are locked up for several days while rich people walk out of jail. This violates the Constitution. In Tate v. Short, 401 U.S. 395 (1971), and Bearden v. Georgia, 461 U.S. 660 (1983), the Supreme Court has held that the Constitution prohibits policies that systematically result in the incarceration of indigent defendants while allowing those with money to go free.

And yet it happens. Of the more than 600,000 people in jail in this country (not counting those in state or federal prison), 70% have not been convicted of anything and hence are legally innocent. Many of them are behind bars solely because they cannot afford to buy their pretrial release.

Being locked up before trial doesn’t just mean you lose a few days of freedom. Will Dobbie, Jacob Goldin, and Crystal Yang are studying the impact of pretrial incarceration on trial results and long-term economic outcomes. They find that people who are released are 27% less likely to be convicted and 28% less likely to plead guilty than people who stay in jail—which makes perfect sense, since you are more likely to plead if it’s your only way to go home and see your family. These effects are even larger for defendants charged with misdemeanors and those with no prior offenses in the previous year. In the long term, pretrial release increases by 27% the likelihood that people will be working three to four years later, with a larger effect for those who were working at the time of arrest. Again, this is obvious: If you miss work because you’re in jail, you could lose your job; and if you plead guilty to get out of jail, the conviction makes it harder for you to find work.

(For those worried about sample selection issues—that is, people who make bail are different from those who don’t—this study takes advantage of the fact that bail judges are quasi-randomly assigned in Philadelphia and Miami. The relative harshness of the judge is the instrument for pre-trial release.)

Maurice Walker was lucky. He got a lawyer. In fact, he got some of the best: Sarah Geraghty and Ryan Primerano of the Southern Center for Human Rights, and Alec Karakatsanis of Equal Justice Under Law. Walker was arrested on a Thursday evening. The next Tuesday, his lawyers filed a class action lawsuit against the City of Calhoun; Walker was released the next day. On January 28, 2016, a federal judge sided with Walker:

Any bail or bond scheme that mandates payment of pre-fixed amounts for different offenses to obtain pretrial release, without any consideration of indigence or other factors, violates the Equal Protection Clause. . . .

The bail policy under which Plaintiff was arrested clearly is unconstitutional.

The city is appealing the case to the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals; the Department of Justice, the American Bar Association, and the Cato Institute have all weighed in on Walker’s side.

What does Maurice Walker have to do with last week’s election?

The sad truth is that many people in the United States already had very tough lives before November 8. Besides Walker and the thousands of people in jail because they are poor, they include Cleopatra Harrison, a domestic violence victim who was threatened with jail because she could not pay a $150 “victim assessment fee” assessed by a court; A.J. and hundreds of other children who face criminal charges in juvenile court without being represented by a lawyer, in violation of the right to counsel; Aron Tuff, Wilmart Martin, Andre Mims, Jeremiah Johnson, and other people sentenced in Georgia to life in prison without the possibility of parole for nonviolent drug offenses (all of whom are African-American); and Tim Foster, who was sentenced to death by an all-white jury after the prosecutor struck every African-American from the jury pool.

There is an ocean of injustice out there. Many of the people harmed by it are poor, minorities, immigrants, or some combination of the above. I only know about the examples above because I’m on the board of the Southern Center for Human Rights, which took all of those cases and was able to help all of those clients. There is no doubt much, much more injustice of which I am unaware.

The perspective is this: Things didn’t suddenly go from wonderful to awful on Tuesday night last week. For many people, they were already pretty bad. A Trump presidency will no doubt make things worse. There will be more hate crime; more deportations of people whose only crime is wanting to work hard and make a better life for their children; more and higher hurdles for women who want an abortion; more people without health insurance; more gun violence; and more hungry children unable to rely on food stamps.

These are all problems that our country had on the morning of November 8, and there are already organizations dedicated to helping the people who face them. As I said, I’m on the board of the Southern Center for Human Rights. We had a board meeting and benefit dinner in Washington last week. And while no one was happy about the national election, it didn’t change what the organization does; it just meant that the struggle will be that much harder for the next four years.

So if you want to “do something” about President Trump, the first thing you can do is donate money to some of the organizations that actively protect people’s civil and human rights. If you’re inspired to give money to the Southern Center, I can assure you that it won’t be wasted; we have some of the best lawyers anywhere, working as hard as they can for remarkably little money. (Today, November 17 is Georgia Gives Day, too, if you prefer to give that way.) But there are many other worthwhile groups out there: the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, the ACLU (perhaps particularly important given Trump’s attempts to intimidate the media), Planned Parenthood, or your local food bank, soup kitchen, or homeless shelter, among many others. At the end of the day, ordinary people will be the victims of the Trump administration, and they will need your help.

That’s the point I wanted to make today, but I imagine that’s not where you expected this post to end. So I’ll add a few words about the other thing that we need to do: take back at least partial control of our government(s). That is a much more difficult issue. You might say that Hillary Clinton lost by only 107,000 votes; by that measure, we only need a slightly better candidate, a slightly better message, or slightly better luck to win in 2020.

More realistically, however, with the small-state bias of the Senate (and the forbidding 2018 electoral map), gerrymandering in the House, and overwhelming Republican dominance of state governments, Clinton’s loss reveals how weak the Democrats already were. This is what I wrote back in June:

Republicans are apoplectic at the idea that Hillary Clinton could appoint the deciding justice to the Supreme Court, but the smart ones realize that she will be able to accomplish little else; even if by some miracle Democrats retake the House, Republican unity will suffice to block anything in the Senate. Democrats, by contrast, are terrified because a Republican president means that they will get virtually everything . . . : not just the Supreme Court, but a flat tax, new abortion restrictions, Medicaid block grants, repeal of Dodd-Frank, repeal of Obamacare, Medicare vouchers, and who knows what else.

The Republicans are dominant not just because of Trump, but because of the decades of work that preceded him: promoting the ideology, cultivating the funders, motivating the base, building the media empire, stocking the judiciary, weakening unions, undermining campaign finance rules, buying state elections, redrawing districts, and suppressing the vote. Yes, Trump was an unlikely leader to take them over the top. (And yes, he is popular among white supremacists.) But even if he hadn’t, the GOP would still be just one election away from a sweep of the White House and Congress.

There is a raging debate right now over the identity of the Democratic Party. I don’t to argue the specifics of that debate right now. But if we want to compete, we need more than a new, focus-grouped brand that can win 51% of the popular vote in a general election. We need an ideology that can mobilize millions of new voters and motivate thousands of people to run in races for school board, town council, state assembly, and state senate, all over the country. We need a long-term political movement, not a quadrennial scramble to demonize the other guy just enough so voters pick our guy.

I don’t know how to create that movement. So all I can recommend, on a personal level, is that you find people whom you believe in—on all levels of politics—give them money or volunteer for their campaigns, and throw your little bit of weight into pushing the party in what you think is the right direction. (Or, if you’re up for it, run for office yourself.) It’s not a great answer, but there is no magic bullet.

November 10, 2016

Narratives

By James Kwak

[Updated to add another headline leading with “white voters.”]

Two days later, some of the world’s leading newspapers—or their headline-writers, at least—are saying it was all or largely about race:

The respective roles of race and class in this year’s election are a highly contentious issue. I’d like to add to that contentiousness as little as possible while pointing out that this race-based framing isn’t really supported by exit poll data. I want to get ahead of the vitriol by stipulating that the exit polls don’t provide conclusive evidence for either side.

The respective roles of race and class in this year’s election are a highly contentious issue. I’d like to add to that contentiousness as little as possible while pointing out that this race-based framing isn’t really supported by exit poll data. I want to get ahead of the vitriol by stipulating that the exit polls don’t provide conclusive evidence for either side.

OK, here’s the data:

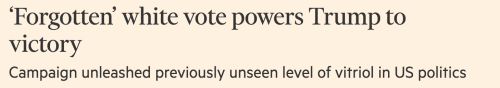

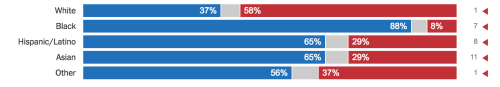

Those are vote shares in the presidential election by racial or ethnic group. The numbers at the right show you the shift from the previous election.* In this case, the Democratic-Republican gap among white voters shifted by 8 points toward the Republican. That’s evidence that the election was about white voters, right?

Except those are the 2012 exit polls. The 8-point shift is relative to the 2008 exit polls.

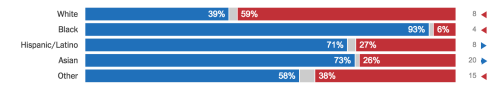

Here’s the equivalent chart for 2016:

As you can see from the right-hand column, Trump did better than Romney among every racial or ethnic group. In fact, if you subtract off how he did among all voters (2 points better than Romney), his performance among whites relative to his overall performance was 1 point worse than Romney’s.

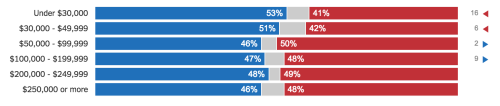

What about income? This is 2016:

There are two factual statements you can make about this picture. One is that Trump lost the “working class” (under $50,000) vote. You will hear a lot of people make that statement. The other is that he did much, much better among the working class than Romney: about 11 points better (the

Looking at these pictures alone, at first glance, the story seems to be more about class than race. In politics, change happens at the margin. Trump is still not the candidate of the working class—Clinton is—but he was able to appeal to them much more successfully than Romney or McCain. As for whites, they have voted for the Republican in every election since at least 1968, and Trump didn’t expand that advantage significantly over where it stood in 2012.

But as I said earlier, I don’t think you can necessarily infer from the exit polls that class was the dominant factor and race was less significant. The problem is that we know a larger proportion of working class people voted for Trump than for Romney, but we don’t know why they voted for Trump, at least not from the data we have. We can make some guesses, but again the exit polls provide support for both stories:

(How each of these two questions provides support for a different story is left as an exercise for the reader.)

At the end of the day, we know that the “white working class” supported Trump much more strongly than it supported Romney, but we can’t tell from polling data if that was because of their judgments about Trump’s policies, their feelings about race, or their feelings about their economic status. In practice, different people in the same demographic group make political choices based on different combinations of those (and other) factors.

I think it’s important to try to understand the relative importance and the interactions of these different motivations, and how those have shifted over time. But if there’s one thing I want you take away, it’s that you can’t answer these questions by looking at aggregate polling data—even though many people will try to do exactly that in the next few days.

* Thanks to the Times for this presentation, and for the ability to switch easily from election to election. When anyone cites a poll number, your first question should be: “Relative to what?” In this case, I think the previous election is the most obvious baseline for interpretive purposes, although it certainly isn’t perfect.

** In 2012, Romney won the >$200K group by 10 points, while Trump won it by 1–2 points; you don’t see that shift in the picture because the 2012 data don’t have a break at $250K.

November 8, 2016

The Biggest Voter Suppression Campaign of All

By James Kwak

This election day, spare a thought for the largest group of citizens who aren’t eligible to vote: children.

My four-year old just learned that he doesn't get to vote tomorrow and he burst into tears and I feel for him.

— Justin Wolfers (@JustinWolfers) November 8, 2016

When I was in high school, I believed strongly that there should be no voting age whatsoever. Anyone should be able to vote, no matter her age. Well, I still feel that way, particularly after watching my ten-year-old daughter knocking on doors and explaining to adults why she doesn’t want her school to be grade-reconfigured. And I feel that way even though I also have a four-year-old son whose vote could be bought for a lollipop. (Whether he would stay bought is another question.)

There are two main arguments against a voting age. The first is that any plausible justification for a minimum voting age could be better served by some other test—which would be illegal. Many people think it is obvious that children shouldn’t be allowed to vote because they are uninformed, irresponsible, lack the necessary cognitive skills, are easily swayed by their parents, or something along those lines. (Note that similar arguments were made about all the other groups that used to be unable to vote.) But if the point of a voting age is to ensure that the electorate is properly informed about the issues and the stakes, we could administer a test, which would do a better job than an arbitrary age cutoff. (Who is the vice president? Which house of Congress approves judicial nominations? Etc.) That test would violate the Voting Rights Act, just like literacy tests.

If the point is to ensure that the electorate has the ability to process information and make rational decisions, again we could come up with a test for that—which would also probably violate the Voting Rights Act. And if we think that children are too easily swayed by their parents, what do we think about the undecided voters who are swayed by the types of television ads that every politician is running right now?

In short, the minimum voting age is supposedly intended to ensure certain characteristics in the voting population. Screening for those characteristics directly would be illegal. So why is OK to use a poor proxy for them?

The second, and more fundamental, argument against a voting age is that it undermines the whole point of our system of government. The reason we have a democracy isn’t that we think everyone is equally capable of making good decisions about who our leaders should be. It’s that we want our leaders to be accountable to ordinary people. This is called government by the consent of the governed. We want our representatives to take their constituents’ interests into account when making decisions; and if they don’t, we want to be able to vote them out of office. Because we want our government to be accountable to everyone, we don’t restrict the suffrage to certain classes of people; we don’t want some types of people to have more political power than others, simply by virtue of who they are.

Except that we do restrict the suffrage. Young people bear the costs of public policy as much as anyone (and arguably more so, since they will be alive for longer), but politicians can safely ignore them because they can’t vote. (Saying their parents will represent their interests is just silly; by that logic, we could simply have one vote per family.) Children live under our government; therefore they should be able to vote. It’s as simple as that.

Politically speaking, a lower voting age would probably help Democrats, since young people tend to be more liberal than old people. (It would probably also eliminate any suspense in the Clinton-Trump contest.) But that’s not the point, just like making election day a holiday isn’t about helping Democrats or increasing turnout. It’s about making sure that everyone has an equal opportunity to hold her representatives accountable.

So I think that if you have the ability to express a preference, you should be able to vote. I recognize that most people won’t agree with that rule. But there’s no reason that states can’t start by reduce the voting age to sixteen. (I’m not a constitutional law scholar, but Nathan Persily is, and he agrees that this is possible.) And do you know what? The world won’t end. And our democracy will be just a little bit stronger.

October 30, 2016

Models of Economic Policymaking

By James Kwak

The evening that he won the Iowa caucus in January 2008, Barack Obama said this:

Hope is the bedrock of this nation. The belief that our destiny will not be written for us, but by us, by all those men and women who are not content to settle for the world as it is, who have the courage to remake the world as it should be… . [the belief that] brick by brick, block by block, callused hand by callused hand, … ordinary people can do extraordinary things.

That speech is at the opening of K. Sabeel Rahman’s new book, Democracy Against Domination. It invoked one of the central mobilizing themes of Obama’s 2008 campaign, which set him clearly apart from Hillary Clinton: the idea that the senator from Illinois would usher in a new kind of politics, a more democratic, more inclusive approach to government as opposed to business as usual inside the Beltway.

Well, that didn’t happen. Whatever you think of President Obama’s policy goals and accomplishments, he had little impact on how our political system works. Plenty of blame for that goes to the Republicans, who set out from Inauguration Day focused exclusively on making him a one-term president. But it’s also true that the new president did not make political reform a priority during those first two years when he had majorities in both houses of Congress.

It can be argued that Obama had other important priorities: stabilizing the financial system, the 2009 stimulus, Obamacare, and the Dodd-Frank Act. But one of the central arguments of Democracy Against Domination is that the president made a conscious choice. When it came to financial regulation, for example, “Obama’s response to the financial crisis evinced a deep-seated … faith in professional, technocratic expertise to solve social problems and transcend the controversies and messiness of ordinary democratic politics” (p. 6).

Let’s step back for a minute. Rahman’s book, on one level, is about how we regulate our economy. Throughout the twentieth century, there were two dominant models of economic policymaking. One, which characterized the New Deal, is technocratic managerialism: the idea that economic regulation is too complex to be left to democratic processes, and therefore must be entrusted to experts who are insulated from day-to-day politics. The other, which became more and more influential as the century wore on, is the ideology of free markets, which dictates that the economy should simply be left to regulate itself.

We all (should) know by now that market self-regulation can lead to catastrophic consequences, such as the financial crisis and Great Recession. But, as Rahman points out, the free marketers developed a pretty powerful critique of technocratic managerialism: the public choice approach to politics and the theory of regulatory capture. So we are left with two main factions—conservatives who want to deregulate everything and moderate Democrats who want to give more authority to to apolitical technocrats (consider the Dodd-Frank Act)—who agree that economic policy has to be insulated from politics. Then we have (some) progressives who think unregulated free markets will produce bad outcomes, but also think that technocracy, at least in areas such as financial regulation, will simply be captured by industry. Simon and I in 13 Bankers fall into that last group.

The question is, if you don’t trust markets and you don’t trust the revolving door, how can you make economic policy? Rahman’s answer is simple, although it raises plenty of other questions: you trust democracy. On a theoretical level, the argument is that if you want economic policies that are responsive to the needs of ordinary people, that will not be captured by elite interest groups, and that are perceived as legitimate, you need to involve ordinary people in the policymaking process.

In the book, Rahman talks about various ways in which democratic participation could be incorporated into the administrative state, such as citizen budgeting or community groups more aggressively engaging with regulators. (Jared Bernstein in The Reconnection Agenda also cites the work of the Center for Popular Democracy, which is trying to encourage Federal Reserve banks to pay more attention to the concerns of the working class.) At present, I would say still there needs to be a fair amount of practice to substantiate the theory. I don’t yet see a way to have non-specialists make substantive contributions to the hundreds of pages of the Volcker Rule. Of course, Paul Volcker himself said the rule should be four pages long, so maybe that’s part of the point. (That was one reason Simon and I argued for simple size caps in 13 Bankers, and why Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig argued for simple capital requirements in The Bankers’ New Clothes.)

At this point, we’re off into questions of democratic theory and political institutional design, in which I am far from an expert. But Rahman’s idea could represent a promising way forward, particularly for people who believe both that the economic playing field is tilted against ordinary people, and that our political system is increasingly deaf to their concerns.

October 29, 2016

The Last Chapter Problem

By James Kwak

Like many analytically minded liberals, I’m good at identifying problems and less good at coming up with solutions—a common disease sometimes called the “last chapter problem.” I recently finished reading The Reconnection Agenda by Jared Bernstein (which you can even download from his blog), which takes the opposite approach.

The problem he addresses is one that we all know about—inequality, stagnant real wages, the divergence between productivity gains and living standards, etc. Bernstein recalls a meeting with a group of insiders in 2014, when a pollster interrupted a discussion of the post-Great Recession economic recovery to say:

If you mention the word “recovery” to people, they don’t know what you’re talking about. And they conclude you don’t know what they’re talking about. It’s not just that they feel disconnected from an economy that’s supposedly growing. It’s that they don’t think anyone understands or knows what to do about their situation.

And he aptly summarizes the state of inside-the-Beltway economic policy debate between “you’re-on-your-own” Republicans and Democrats:

The YOYOs run around arguing, unconvincingly to most, that government is the problem, while most Democrats nibble at the edges with YOYO-light, maybe sprinkling in a minimum wage increase. Everyone treats the private market economy like a delicate vase that mustn’t be bumped.

(That near-consensus on the magic of market forces is also the subject of my new book.)

But Bernstein, to his credit, gets the description of the problem out of the way in the first two chapters. He devotes the rest of the book to solutions: policy tools that can not only increase growth but, just as importantly, ensure that the benefits of growth are widely shared throughout the income distribution. Some are relatively standard Democratic fare, like expanding automatic stabilizers, spending more on infrastructure, universal pre-school, and maintaining a symmetric monetary policy—that is, not pretending you have an inflation target when what you really have is an inflation ceiling.

More generally, however, Bernstein focuses on the importance of using economic policy to change the pre-tax distribution of income—bolstering the bargaining power of workers so they can demand a larger share of the gains from increases in their own productivity. Among other things, that means making it easier for workers to form unions, subsidized jobs and apprenticeship programs to help people gain skills, and ban-the-box rules that help people with “criminal records” (which can mean just an arrest with no conviction) compete fairly for jobs. These are not policies that all Democrats support. But, as Bernstein writes, turnout by Democratic constituencies “may well hinge on whether they believe a candidate will try to implement a set of policies that convincingly relinks growth and their living standards.”

As I’ve written about previously, this presidential election has become a referendum on Donald Trump. But for Democrats to have any chance of maintaining our congressional gains in 2018, we have slightly less than two years to convince the public that we care about something more than fiscal responsibility and overall economic growth.

October 24, 2016

Time to Vote; No on 5

By James Kwak

If you live in Massachusetts, early voting has begun. You can ask for an early ballot by mail, or just find a polling place here. This is what my town hall looks like today:

Not surprisingly, I voted for Hillary Clinton (more about why here). If you don’t live in Amherst, Massachusetts, you may want to stop reading. If you do live in Amherst, I’d like you to consider voting no on Question 5.

Technically speaking, Question 5 allows the town to override Proposition 2-1/2, which ordinarily limits property tax increases, in order to issue bonds to build a new school for all Amherst children in grades 2–6. (The bonds would be issued now, but presumably property tax increases will be necessary to back them.) I ordinarily vote for overrides as a matter of course, but this time I voted no.

The original motivation for this project was that two of our three neighborhood elementary schools for grades K–6, Wildwood and Fort River, are in poor physical condition. To make a long story short, the school district successfully applied for money from the Massachusetts School Building Authority, but that money can only be used at one physical site—hence the plan to build one large school complex instead of building two smaller schools (or renovating both Wildwood and Fort River). According to current estimates, the MSBA will contribute about $33,700,000 to the project, and the town’s share will be $32,700,000.

At the same time, the plan is to completely reconfigure elementary education in the town. The third current school, Crocker Farm, will become a K–1 school. (Crocker also has a small, not-universal pre-K program, which will remain.) The new, $66 million school complex will serve all students in grades 2–6. It will be organized as two separate “schools” with various shared facilities. This is what I am opposed to.

I am opposed for two types of reasons. First, there are several obvious problems with this plan. It significantly increases time on the school bus for both grade K–1 children in North Amherst and grade 2–6 children in South Amherst. Amherst is a tall and skinny town, and it takes a long time to get from one end to the other—considerably longer on a school bus. Our children would be better off if we were to invest the extra ten minutes in the morning and ten minutes in the afternoon in classroom time rather than bus trips.

In addition, the reconfiguration creates an extra school transition for seven-year-old kids, just two years after the wrenching transition of starting kindergarten. It also increases grade cohorts by 200% (or 50% in grades 2–6, to the extent that the two “schools” at the new site will be kept distinct).

Second, and more fundamentally—and this is what I said in last year’s survey of parents—reengineering the entire grade configuration is a solution in search of a problem. The clear problem is that Wildwood and Fort River are in bad physical shape and need to be renovated or replaced. We should solve that problem. But a school is more than a building. We have three of them. And nowhere in all the documents that I saw last year did I even see an argument for why we need to blow them up and start over from a theoretical blueprint.

I saw some claims for why consolidating entire grades in one place would be a good thing, along the lines of greater efficiency using shared resources. (For example, instead of three small libraries, you can have one big one.) I used to be a management consultant. I can make that argument, too.

But there’s a more important principle: Don’t tear apart things that work well just because, in theory, you can put them back together in an even better way. Running any kind of organization is hard enough as it is without creating complications trying to solve problems that don’t exist. There’s a reason why most school districts in the country don’t make all children switch schools between first and second grade. What research and debate there are center around when to switch from elementary to middle school—not whether to split elementary school at age seven. Are we really confident that we—including a superintendent who just resigned—know better than anyone else how to organize a school system?

My daughter goes to Crocker Farm. We think it’s a good school. We have friends who sent their kids to Wildwood. They think it’s a good school—in a bad building. I don’t want to blow up Crocker Farm (the school, not the building), and I don’t see why anyone would want to blow up Wildwood (the school, not the building). I would gladly vote for an override to fix Wildwood and Fort River, or build new buildings for them, or—if necessary—build new buildings for them right next to each other.* But I don’t think it’s right to inflict a vast, unnecessary grade configuration experiment on our children.

* Lest anyone think this is about my property taxes: If anyone can tell me what the actual increase in my property taxes would be under Question 5, and if Question 5 is defeated, I will donate that amount to the schools.

October 21, 2016

Ideas, Interests, and the Challenge for Progressives

By James Kwak

Mike Konczal wrote an article a few days back arguing that various progressive policies aimed at helping poor people would not be able to pry the “white working class” away from Donald Trump and Trumpism. I think the article was insightful and intelligently argued. This was my quick response:

@rortybomb It took 35 years to create the economy we have. It will take 35 years to fix it and create broadly shared prosperity.

— James Kwak (@jamesykwak) October 19, 2016

In other words, it’s the long term that matters. We need policies that create broadly shared prosperity not because they will peel away Trump supporters in the short term, but because they are the right thing to do. And in the long term, if progressives prove that they can deliver the goods—a society with less inequality and less economic insecurity—that will change the political landscape.

Dani Rodrik wrote a longer, better response to Konczal. Rodrik’s perspective, which he’s presented in greater depth in the Journal of Economic Perspectives and a recent paper with Sharun Mukand, is that political outcomes result from the interaction of interests and ideas. As he writes in his recent post, “The politics of ideas is about activating identities that may otherwise remain silent, altering perceptions about how the world works, and enlarging the space of what is politically feasible.” Politicians appeal in part to voters’ interests, but also attempt to make salient identities that they share (or pretend to share) with particular segments of the electorate.

In this framework, Konczal may be correct—progressive economic policies may not appeal to white, working class Trump voters—but that’s because progressives lost the battle of ideas long ago. The implication is that progressives need better ideas, not just more effective policies. In his post, Rodrik cites Konczal’s example of people who “view the federal government as something that is helping people ‘cut in line,'” and continues:

In other words, people dislike and distrust the government. And yes of course, conditional on that belief, the progressives’ agenda of enhanced environmental regulation will not draw the support of the people it tries to help. Same with dealing with the banks, creating more jobs, or progressive taxation.

Clearly, the progressives have lost the war of ideas here – on government as a force for good. Equally clearly, they will not win it by offering detailed policy proposals on each one of these areas.

We progressives tend to be rather smug about the belief that our policies (infrastructure spending, social insurance, expanded family leave, universal pre-K, etc.) will do a better job helping poor people than typical conservative policies (cut taxes and regulations and let the invisible hand do its magic). Where we have generally failed is in convincing ordinary people, not policy wonks, that our vision will create a better society for them and their families—or perhaps that we have a vision at all.

This is hard to do, and I don’t have a simple answer for how to do it. But it is something that the right did extraordinarily well during their decades in the wilderness after World War II. It was an article of faith among Hayek, Friedman, Buckley, and the old conservative warriors that ideas mattered—that they could only gain political power by undermining the intellectual and political near-consensus around the New Deal. Part of their success lay in transforming their economic policy program—small government, low taxes, union-busting—into a powerful ideology that could appeal to people in all classes. Ronald Reagan’s message that government was the problem, and that the solution lay in unleashing the energy of the free American people, was and remains compelling even to people who have been the victims of Reaganite policies. More generally, the idea that markets are the best way to solve all problems has become so completely baked into contemporary discourse that it is no longer seen as an ideology. (This is roughly what I call “economism” in my new book.)

In the battle of ideas, progressives have been on the back foot ever since Reagan, which is probably one reason why we like to retreat to the realm of policy detail, where we can revel in our technocratic superiority. But somehow, as Rodrik points out, “they need to convince the electorate that it is their interests they have at heart – not those of bankers or of large corporations.” That could also take thirty-five years. But we have to begin somewhere.

October 18, 2016

Structure and Superstructure

By James Kwak

Noah Smith begins his latest Bloomberg column this way:

Stanford historian Ian Morris is fond of saying that “each age gets the thought it needs.” According to this maxim, ideas like the Enlightenment, communism or even Christianity are a product of the economic and political circumstances of their times.

This is something I’ve long believed, dating back before my days as a graduate student in intellectual history. It’s also pure Marx. In the “Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy,” the great bearded one wrote:

With the change of the economic foundation the entire immense superstructure is more or less rapidly transformed. In considering such transformations a distinction should always be made between the material transformation of the economic conditions of production . . . and the legal, political, religious, aesthetic or philosophic—in short, ideological forms in which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out.

When I was a junior in college, I underlined that passage in my bright red copy of The Marx-Engels Reader. (As I’ve often said, Harvard social studies majors will probably be the last people on the planet still reading Marx.)

Smith’s point is to situate what he calls libertarianism in its historical context. (He uses “libertarianism” in a relatively narrow, economics-focused sense, which some libertarians might find restrictive, but I’ll stick with his terminology here.) At the end of World War II, government power had reached unprecedented heights in modern history, particular in economic affairs. “It made sense to fight these forces with a philosophy that emphasized individual liberty and limited government,” Smith writes. He continues by arguing that the abstract libertarian model misses out on the complexity of society. In particular, since power can be exercised on multiple levels between individuals and the state, “the neat and tidy universe of classic libertarianism breaks down.” What we need today, then, is a new political philosophy, or philosophies, that reflect this complexity.

I agree with all of that. I just want to add a little more depth to the idea that libertarianism “made sense.” Marx didn’t think that an age “got the thought it needs” by accident; just because ideas make sense doesn’t mean that they will become influential. (Between Occupy Wall Street and the Tea Party, which set of ideas made more sense to you?) Instead, Marx argued in the passage above, the conflict of ideas is the superstructure determined by the fundamental structure of class struggle.

For Marx, of course, class struggle meant the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. I think by now we realize that the world is considerably more complicated than that. But the underlying principle still holds: ideas gain sway because they serve important economic interest groups. That was certainly true of communism, which became the organizing ideology of the working class.

It was also true of libertarian ideas after World War II. In the United States, the political landscape was dominated by the New Deal Democratic coalition and Keynesian economic principles. Corporations that had to contend with powerful labor unions and rich people who had to pay higher taxes were on the defensive. For those interest groups, the theory that competitive markets could maximize social welfare and that government intervention could only make life worse for everyone provided exactly the ideology that they needed. Money from businessmen’s foundations and, later, large corporations that financed the think tanks and networks that cultivated and disseminated the free-market critique of New Deal policies which—to jump ahead—ultimately bore fruit in the Reagan Revolution.

I tell this story in detail in the history chapter my new book, Economism: Bad Economics and the Rise of Inequality, although not in as much detail as some of the historians I draw on, such as Kimberly Phillips-Fein and Gareth Stedman Jones. (I almost wrote “real historians” before remembering that I have a history PhD.) But the key point I want to make here about ideas, interest groups, and ideologies was actually also made by Marx, this time in The German Ideology:

Each new class which puts itself in the place of one ruling before it, is compelled, merely in order to carry through its aim, to represent its interest as the common interest of all the members of society, that is, expressed in ideal form: it has to give its ideas the form of universality, and represent them as the only rational, universally valid ones.

That’s why libertarianism “made sense” to the businessmen and wealthy families who led the postwar reaction against the New Deal—and to their descendants who continue to finance the conservative movement.

Simon Johnson's Blog

- Simon Johnson's profile

- 78 followers