Daniel Orr's Blog, page 80

November 10, 2020

November 10, 1945 – British forces and Indonesian nationalist militias clash in the Battle of Surabaya

On November 10, 1945, British forces and Indonesian nationalist fighters fought the Battle of Surabaya during the Indonesian War of Independence. After World War II ended, the first Allied forces arrived in the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia) in mid-September 1945. When British forces arrived in Surabaya in East Java in late October, they found that the city was fortified by Indonesian nationalist fighters – in all, some 20,000 Indonesian revolutionary troops and 100,000 militia fighters had taken defensive positions. In a skirmish on October 30, 1945, British Brigadier A.W.S. Mallaby was killed, which served as a trigger for the British to initiate full-scale fighting on November 10. Within three days, British forces had largely taken the city, but fierce house-to-house fighting continued for three weeks, with some 30,000 British troops supported with tanks, aircraft, and artillery bombardment from warships finally forcing out the last guerrilla resistance.

The Southeast Asian country of Indonesia was known as the Dutch East Indies during the colonial period.

The Southeast Asian country of Indonesia was known as the Dutch East Indies during the colonial period.(Taken from Indonesian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

BackgroundSukarno’s proclamation of Indonesia’s independence de facto produced a state of war with the Allied powers, which were determined to gain control of the territory and reinstate the pre-war Dutch government. However, one month would pass before the Allied forces would arrive. Meanwhile, the Japanese East Indies command, awaiting the arrival of the Allies to repatriate Japanese forces back to Japan, was ordered by the Allied high command to stand down and carry out policing duties to maintain law and order in the islands. The Japanese stance toward the Indonesian Republic varied: disinterested Japanese commanders withdrew their units to avoid confrontation with Indonesian forces, while those sympathetic to or supportive of the revolution provided weapons to Indonesians, or allowed areas to be occupied by Indonesians. However, other Japanese commanders complied with the Allied orders and fought the Indonesian revolutionaries, thus becoming involved in the independence war.

In the chaotic period immediately after Indonesia’s

independence and continuing for several months, widespread violence and anarchy

prevailed (this period is known as “Bersiap”, an Indonesian word meaning “be

prepared”), with armed bands called “Pemuda” (Indonesian meaning “youth”)

carrying out murders, robberies, abductions, and other criminal acts against

groups associated with the Dutch regime, i.e. local nobilities, civilian

leaders, Christians such as Menadonese and Ambones, ethnic Chinese, Europeans,

and Indo-Europeans. Other armed bands

were composed of local communists or Islamists, who carried out attacks for the

same reasons. Christian and

nobility-aligned militias also were organized, which led to clashes between

pro-Dutch and pro-Indonesian armed groups.

These so-called “social revolutions” by anti-Dutch militias, which

occurred mainly in Java and Sumatra, were

motivated by various reasons, including political, economic, religious, social,

and ethnic causes. Subsequently when the

Indonesian government began to exert greater control, the number of violent

incidents fell, and Bersiap soon came to an end. The number of fatalities during the Bersiap

period runs into the tens of thousands, including some 3,600 identified and

20,000 missing Indo-Europeans.

The first major clashes of the war occurred in late August

1945, when Indonesian revolutionary forces clashed with Japanese Army units,

when the latter tried to regain previously vacated areas. The Japanese would be involved in the early

stages of Indonesia’s

independence war, but were repatriated to Japan by the end of 1946.

In mid-September 1945, the first Allied forces consisting of

Australian units arrived in the eastern regions of Indonesia (where revolutionary

activity was minimal), peacefully taking over authority from the commander of

the Japanese naval forces there. Allied

control also was established in Sulawesi, with

the provincial revolutionary government offering no resistance. These areas were then returned to Dutch

colonial control.

In late September 1945, British forces also arrived in the

islands, the following month taking control of key areas in Sumatra, including Medan, Padang, and Palembang, and in

Java. The British also occupied Jakarta (then still known, until 1949, as Batavia),

with Sukarno and his government moving the Republic’s capital to Yogyakarta in Central Java. In

October 1945, Japanese forces also regained control of Bandung

and Semarang

for the Allies, which they turned over to the British. In Semarang, the intense fighting claimed the

lives of some 500 Japanese and 2,000 Indonesian soldiers.

In late October 1945, the shooting death of British General

Aubertin Mallaby in Surabaya

prompted the British command to launch a land, air, and sea attack on the

city. In this encounter, known as the

Battle of Surabaya, the British met fierce resistance from Pemuda militias but

gained control of the city after three days of fighting. Casualties on both sides were high,

fatalities numbering 6,000-16,000 revolutionaries and 500-2,000 mostly British

Indian soldiers.

In late 1945, the revolutionaries intensified their attacks

in Bandung. Then in March 1946, forced by the British to

withdraw from Bandung,

the revolutionaries set fire to a large section of the city in what is known as

the “Bandung Sea of Fire”. Also that

month, communal violence broke out in East Sumatra,

where elements supporting the revolutionaries attacked groups aligned with the

old colonial order.

The Netherlands

itself was greatly weakened by World War II, and was unable to quickly

reestablish its presence in the Dutch East Indies. However, by April 1946, Dutch troops had

begun to arrive in large numbers, ultimately peaking at 180,000 during the war

(aside from another 60,000 predominantly native colonial troops of the Royal

Dutch East Indies Army). The restored

colonial government, called the Netherlands Indies Civil Administration,

reclaimed Jakarta as its capital, while Dutch

authority also was established in the other major cities in Java and Sumatra,

and in the rest of the original Dutch East Indies.

By late 1946, the British military had completed its mission

in the archipelago, that of repatriating Japanese forces to Japan and freeing the Allied

prisoners of war. By December 1946,

British forces had departed from the islands, but not before setting up

mediation talks between the Dutch government and Indonesian revolutionaries, an

initiative that led the two sides to agree to a ceasefire in October 1946. Earlier in June 1946, the Dutch government

and representatives of ethnic and religious groups and the aristocracy from

Sulawesi, Maluku, West New Guinea, and other eastern states met in South

Sulawesi and agreed to form a federal-type government attached to the

Netherlands. In talks held with the

Indonesian revolutionaries, Dutch authorities presented a similar proposal

which on November 12, 1946, produced the Linggadjati Agreement, where the two

sides agreed to establish a federal system known as the United States of

Indonesia (USI) by January 1, 1949. The Republic of Indonesia

(consisting of Java, Madura, and Sumatra) would comprise one state under USI;

in turn, USI and the Netherlands

would form the Netherlands-Indonesian Union, with each polity being a fully

sovereign state but under the symbolic authority of the Dutch monarchy.

November 9, 2020

November 9, 1938 – A German diplomat is assassinated by a Polish Jew; in response, Hitler initiates “Kristallnacht”

On November 9, 1938 in Paris, German diplomat Ernst vom Rath

was assassinated by a Polish Jew. In response, Hitler’s government carried out “Kristallnacht”

(Crystal Night), where the Nazi SA and civilian mobs in Germany went on a

violent rampage, killing hundreds of Jews, jailing tens of thousands of others,

and looting and destroying Jewish homes, schools, synagogues, hospitals, and

other buildings. Some 1,000 synagogues

were burned, and 7,000 businesses destroyed.

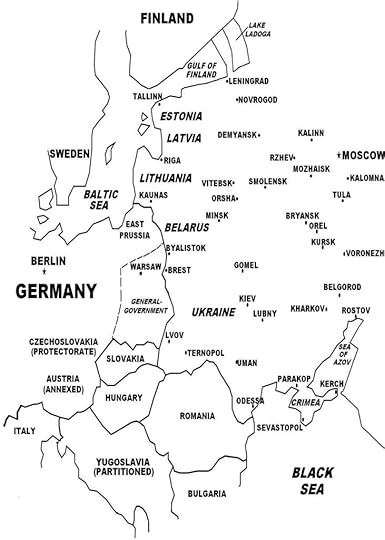

(Taken from Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Hitler and Nazis in

Power In October 1929, the severe economic crisis known as the Great

Depression began in the United

States, and then spread out and affected

many countries around the world. Germany, whose economy was dependent on the United States

for reparations payments and corporate investments, was badly hit, and millions

of workers lost their jobs, many banks closed down, and industrial production

and foreign trade dropped considerably.

The Weimar

government weakened politically, as many Germans turned to radical ideologies,

particularly Hitler’s ultra-right wing nationalist Nazi Party, as well as the

German Communist Party. In the 1930

federal elections, the Nazi Party made spectacular gains and became a major

political party with a platform of improving the economy, restoring political

stability, and raising Germany’s

international standing by dealing with the “unjust” Versailles treaty. Then in two elections held in 1932, the Nazis

became the dominant party in the Reichstag (German parliament), albeit without

gaining a majority. Hitler long sought

the post of German Chancellor, which was the head of government, but he was

rebuffed by the elderly President Paul von Hindenburg , who distrusted

Hitler. At this time, Hitler’s ambitions

were not fully known, and following a political compromise by rival parties, in

January 1933, President Hindenburg appointed Hitler as Chancellor, with few

Nazis initially holding seats in the new Cabinet. The Chancellorship itself had little power,

and the real authority was held by the President (the head of state).

On the night of February 27, 1933, fire broke out at the

Reichstag, which led to the arrest and execution of a Dutch arsonist, a

communist, who was found inside the building.

The next day, Hitler announced that the fire was the signal for German

communists to launch a nationwide revolution.

On February 28, 1933, the German parliament passed the “Reichstag Fire

Decree” which repealed civil liberties, including the right of assembly and freedom

of the press. Also rescinded was the

writ of habeas corpus, allowing authorities to arrest any person without the

need to press charges or a court order.

In the next few weeks, the police and Nazi SA paramilitary carried out a

suppression campaign against communists (and other political enemies) across Germany,

executing communist leaders, jailing tens of thousands of their members, and

effectively ending the German Communist Party.

Then in March 1933, with the communists suppressed and other parties

intimidated, Hitler forced the Reichstag to pass the Enabling Act, which

allowed the government (i.e. Hitler) to enact laws, even those that violated

the constitution, without the approval of parliament or the president. With nearly absolute power, the Nazis gained

control of all aspects of the state. In

July 1933, with the banning of political parties and coercion into closure of

the others, the Nazi Party became the sole legal party, and Germany became

de facto a one-party state.

At this time, Hitler grew increasingly alarmed at the

military power of the SA, particularly distrusting the political ambitions of

its leader, Ernst Rohm. On June 30-July

2, 1934, on Hitler’s orders, the loyalist Nazi SS (Schutzstaffel; English:

Protection Squadron) and Gestapo (Secret Police) purged the SA, killing

hundreds of its leaders including Rohm, and jailing thousands of its members,

violently bringing the SA organization (which had some three million members)

to its knees. The purge benefited Hitler

in two ways: First, he became the undisputed leader of the Nazi apparatus, and

Second and equally important, his standing greatly increased with the upper

class, business and industrial elite, and German military; the latter,

numbering only 100,000 troops because of the Versailles treaty restrictions,

also felt threatened by the enormous size of the SA.

In early August 1934, with the death of President

Hindenburg, Hitler gained absolute power, as his Cabinet passed a law that

abolished the presidency, and its powers were merged with those of the

chancellor. Hitler thus became both

German head of state and head of government, with the dual roles of Fuhrer

(leader) and Chancellor. As head of

state, he also was Supreme Commander of the armed forces, making him absolute

ruler and dictator of Germany.

In domestic matters, the Nazi government made great gains,

improving the economy and industrial production, reducing unemployment,

embarking on ambitious infrastructure projects, and restoring political and

social order. As a result, the Nazis

became extremely popular, and party membership grew enormously. This success was brought about from sound

policies as well as through threat and intimidation, e.g. labor unions and job

actions were suppressed.

Hitler also began to impose Nazi racial policies, which saw

ethnic Germans as the “master race” comprising “super-humans” (Ubermensch),

while certain races such as Slavs, Jews, and Roma (gypsies) were considered

“sub-humans” (Untermenschen); also lumped with the latter were non-ethnic-based

groups, i.e. communists, liberals, and other political enemies, homosexuals,

Freemasons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, etc.

Nazi lebensraum (“living space”) expansionism into Eastern Europe and Russia called

for eliminating the Slavic and other populations there and replacing them with

German farm settlers to help realize Hitler’s dream of a 1,000-year German

Empire.

In Germany

itself, starting in April 1933 until the passing of the Nuremberg Laws in

September 1935 and beyond, Nazi racial policy was directed against the local

Jews, stripping them of civil rights, banning them from employment and

education, revoking their citizenship, excluding them from political and social

life, disallowing inter-marriages with Germans, and essentially declaring them

undesirables in Germany. As a result, tens of thousands of Jews left Germany. Hitler blamed the Jews (and communists) for

the civilian and workers’ unrest and revolution near the end of World War I,

ostensibly that had led to Germany’s

defeat, and for the many social and economic problems currently afflicting the

nation. Following anti-Nazi boycotts in

the United States, Britain, and other countries, Hitler retaliated

with a call to boycott Jewish businesses in Germany, which degenerated into

violent riots by SA mobs that attacked and killed, and jailed hundreds of Jews,

looted and destroyed Jewish properties, and seized Jewish assets. The most notorious of these attacks occurred

in November 1938 in “Kristallnacht” (Crystal Night), where in response to the

assassination of a German diplomat by a Polish Jew in Paris, the Nazi SA and

civilian mobs in Germany went on a violent rampage, killing hundreds of Jews,

jailing tens of thousands of others, and looting and destroying Jewish homes,

schools, synagogues, hospitals, and other buildings. Some 1,000 synagogues were burned, and 7,000

businesses destroyed.

In foreign affairs, Hitler, like most Germans, denounced the

Versailles

treaty, and wanted it rescinded. In

1933, Hitler withdrew Germany

from the World Disarmament Conference in Geneva,

and in October of that year, from the League of Nations, in both cases

denouncing why Germany

was not allowed to re-arm to the level of the other major powers.

In March 1935, Hitler announced that German military

strength would be increased to 550,000 troops, military conscription would be

introduced, and an air force built, which essentially meant repudiation of the

Treaty of Versailles and the start of full-scale rearmament. In response, Britain,

France, and Italy formed

the Stresa Front meant to stop further German violations, but this alliance

quickly broke down because the three parties disagreed on how to deal with

Hitler.

November 8, 2020

November 8, 1940 – World War II: Greek forces repulse an Italian offensive at Elaia-Kalamas

On November 8, 1940, Greek forces repulsed an Italian offensive at the Battle of Elaia-Kalamas during the Greco-Italian War. The Italians launched their invasion of Greece on October 28, 1940. At the coastal flank of the Epirus sector, the Greek main defensive line was located at Elaia-Kalamas, some 30 km south of the Greek-Albanian border. On November 2, Italian forces launched air and artillery strikes on Greek positions, and by November 5, were able to establish a bridgehead over the Kalamas River. However, Greek defenses held despite repeated attempts to break through with infantry and light and medium tanks. The Italian offensive stalled as much as by the tenacity of the defenders and minefields as by the harsh hilly, rugged terrain and muddy ground caused by heavy rains.

(Taken from Greco-Italian War – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

On October 28, 1940, Italian forces in Albania, which were

massed at the Greek-Albanian border, opened their offensive along a 90-mile

(150 km) front in two sectors: in Epirus, which comprised the main attacking

force; and in western Macedonia, where the Italian forces were to hold their

ground and remain inside Albania. A

third force was assigned to guard the Albania-Yugoslavia frontier. The Italian offensive was launched in the

fall season, and would be expected to face extremely difficult weather

conditions in high-altitude mountain terrain, and be subject to snow, sleet,

icy rain, fog, and heavy cloud cover. As

it turned out, the Italians were supplied only with summer clothing, and so

were unprepared for these conditions.

The Italians also had planned to seize Corfu,

which was cancelled due to bad weather.

At the Epirus

sector, the Italians attacked along three points: at the coast for Konispol and

proceeding to the main targets of Igoumenitsa and Preveza; at the center of

Kalpaki; and in the Pindus Mountains separating Epirus

and western Macedonia,

towards Metsovo. The coastal advance

made some progress, gaining 40 miles (60 km) in the first few days without

meeting serious resistance and seizing Igoumenitsa and Margariti. The Italians soon were stalled at the Kalamas River, which was swollen and raging from

recent heavy rains.

Background In

April 1939, Italian forces invaded Albania (previous

article) in what Italian leader Benito Mussolini hoped would be the first

step to founding an Italian Empire (in the style of the ancient Roman Empire)

in southern Europe, which would be added to the colonies that he already

possessed in Africa (Italian East Africa and Libya).

In September 1939, World War II broke out in Europe when Germany attacked Poland,

prompting Britain and France to declare war on Germany. After an eight-month period of combat

inactivity in Europe (called the “Phoney War”), in April 1940, Germany launched the invasions to the north and

west, which ended in the defeat of France on June 25, 1940. In July 1940, Hitler set his sights on

Britain, with the Luftwaffe (German Air Force) launching attacks (lasting until

May 1941) aimed at eliminating the last impediment to his full domination of

Western Europe.

To Mussolini, France’s

defeat and Britain’s

desperate position seemed the perfect time to advance his ambitions in southern

Europe.

Just as France was verging on defeat from the German onslaught, on June

10, 1940, in a brazen act of opportunism[1],

Mussolini entered World War II on Germany’s side by declaring war on France and

Britain, and sending Italian forces that attacked France through the

Italian-French border. Then with Britain grimly fighting for its own survival

from the German air attacks (Battle of Britain, separate article), Mussolini set his sights on British possessions

in Africa, with Italian forces seizing British Somaliland in August 1940, and

advancing into Egypt from Libya

in September 1940.

Mussolini aspired to establish an Italian Empire that would control southern Europe, northern Africa, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Middle East.

Mussolini aspired to establish an Italian Empire that would control southern Europe, northern Africa, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Middle East.At the same time, Mussolini was ready to build an Italian Empire, with

his attention focused on the Balkans which he saw as falling inside the Italian

sphere of influence. He also longed to

gain mastery of the Mediterranean Sea in the Mare Nostrum (“Our Sea”) concept, and turn it into an

“Italian lake”. He chafed at Italy’s geographical location in the middle of

the Mediterranean Sea, likening it to being

shut in and imprisoned by the British and French, who controlled much of the

surrounding regions and possessed more powerful navies. Mussolini was determined to expand his own

navy and gain dominance over southern Europe and northern Africa, and

ultimately build an empire that would stretch from the Strait

of Gibraltar at the western tip of the

Mediterranean Sea to the Strait of Hormuz near the Persian

Gulf.

Meanwhile, Greece had

become alarmed by the Italian invasion of Albania. Greek Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas, who

ironically held fascist views and was pro-German, turned to Britain for assistance. The British Royal Navy, which had bases in

many parts of the Mediterranean, including Gibraltar,

Malta, Cyprus, Egypt,

and Palestine, then made security stops in Crete and other Greek islands.

Italian-Greek relations, which were strained since the late 1920s by

Mussolini’s expansionist agenda, deteriorated further. In 1940, Italy

initiated an anti-Greek propaganda campaign, which included the demand that the

Greek region of Epirus must

be ceded to Albania,

since it contained a large ethnic Albanian population. The Epirus

claim was popular among Albanians, who offered their support for Mussolini’s

ambitions on Greece. Mussolini accused Greece of being a British puppet,

citing the British naval presence in Greek ports and offshore waters. In reality, he was alarmed that the British

Navy lurking nearby posed a direct threat to Italy

and hindered his plans to establish full control of the Adriatic and Ionian Seas.

Italy then launched

armed provocations against Greece,

which included several incidents in July-August 1940, where Italian planes

attacked Greek vessels at Kissamos, Gulf of Corinth, Nafpaktos, and Aegina. On August

15, 1940, an undetected Italian submarine sank the Greek light cruiser Elli.

Greek authorities found evidence that pointed to Italian responsibility

for the Elli sinking, but Prime

Minister Metaxas did not take any retaliatory action, as he wanted to avoid war

with Italy.

Also in August 1940, Mussolini gave secret orders to his military high

command to start preparations for an invasion of Greece. But in a meeting with Hitler, Mussolini was

prevailed upon by the German leader to suspend the invasion in favor of the

Italian Army concentrating on defeating the British in North

Africa. Hitler was

concerned that an Italian incursion in the Balkans would worsen the perennial

state of ethnic tensions in that region and perhaps prompt other major powers,

such as the Soviet Union or Britain,

to intervene there. The Romanian oil

fields at Ploiesti, which were extremely vital

to Germany,

could then be threatened. In August

1940, unbeknown to Mussolini, Hitler had secretly instructed the Germany military high command to draw up plans

for his greatest project of all, the conquest of the Soviet

Union. And for this

monumental undertaking, Hitler wanted no distractions, including one in the

Balkans. In the fall of 1940, Mussolini

deferred his attack on Greece,

and issued an order to demobilize 600,000 Italian troops.

Then on October 7, 1940, Hitler deployed German troops in Romania at the

request of the new pro-Nazi government led by Prime Minister Ion

Antonescu. Mussolini, upon being

informed by Germany four

days later, was livid, as he believed that Romania fell inside his sphere of

influence. More disconcerting for

Mussolini was that Hitler had again initiated a major action without first

notifying him. Hitler had acted alone in

his conquests of Poland, Denmark, Norway,

France, and the Low Countries, and had given notice to the Italians only

after the fact. Mussolini was determined

that Hitler’s latest stunt would be reciprocated with his own move against Greece. Mussolini stated, “Hitler faces me with a

fait accompli. This time I am going to

pay him back in his own coin. He will find out from the papers that I have

occupied Greece.

In this way, the equilibrium will be re-established.”

On October 13, 1940 and succeeding days, Mussolini finalized with his top

military commanders the immediate implementation of the invasion plan for

Greece, codenamed “Contingency G”, with Italian forces setting out from

Albania. A modification was made, where

an initial force of six Italian divisions would attack the Epirus region, to be followed by

the arrival of more Italian troops. The

combined forces would advance to Athens and

beyond, and capture the whole of Greece. The modified plan was opposed by General

Pietro Badoglio, the Italian Chief of Staff, who insisted that the original

plan be carried out: a full-scale twenty-division invasion of Greece with Athens as the immediate objective. Other factors cited by military officers who

were opposed to immediate invasion were the need for more preparation time, the

recent demobilization of 600,000 troops, and the inadequacy of Albanian ports

to meet the expected large volume of men and war supplies that would be brought

in from Italy.

But Mussolini would not be dissuaded.

His decision to invade was greatly influenced by three officials:

Foreign Minister Count Galeazzo Ciano (who was also Mussolini’s son-in-law),

who stated that most Greeks detested their government and would not resist an

Italian invasion; the Italian Governor-General of Albania Francesco Jacomoni,

who told Mussolini that Albanians would support an Italian invasion in return

for Epirus being annexed to Albania; and the commander of Italian forces in

Albania General Sebastiano Prasca, who assured Mussolini that Italian troops in

Albania were sufficient to capture Epirus within two weeks. These three men were motivated by the

potential rewards to their careers that an Italian victory would have; for

example, General Prasca, like most Italian officers, coveted being conferred

the rank of “Field Marshall”.

Mussolini’s order for the invasion had the following objectives,

“Offensive in Epirus,

observation and pressure on Salonika, and in a second phase, march on Athens”.

On October 18, 1940, Mussolini asked King Boris II of Bulgaria to participate in a joint attack on Greece, but the monarch declined, since under

the Balkan Pact of 1934, other Balkan countries would intervene for Greece in a Bulgarian-Greek

war. Deciding that its border with Bulgaria was secure from attack, the Greek

government transferred half of its forces defending the Bulgarian border to Albania;

as well, all Greek reserves were deployed to the Albanian front. With these moves, by the start of the war,

Greek forces in Albania

outnumbered the attacking Italian Army. Greece

also fortified its Albanian frontier.

And because of Mussolini’s increased rhetoric and threats of attack, by

the time of the invasion, the Italians had lost the element of surprise.

[1] Mussolini had stated just five days earlier, on June 5, 1940,

“I only need a few thousand dead so that I can sit at the peace conference

as a man who has fought”.

November 7, 2020

November 7, 1941 – World War II: Joseph Stalin leads the October Revolution celebrations in the midst of the Battle of Moscow

On November 7, 1941, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin led the celebrations for the October Revolution in Moscow’s Red Square. In his speech, Stalin exhorted the parading soldiers as they were about to be sent to battle. Many of them would be killed in the fighting for Moscow. The event took place just as German forces were closing in on the Soviet capital.

In modern-day Russia, November 7th is celebrated as a Day of Military Honour in commemoration of the 1941 parade.

(Taken from Battle of Moscow – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

On October 2, 1941, shortly after the Kiev

campaign ended, on Hitler’s orders, the Wehrmacht launched its offensive on Moscow. For this campaign, codenamed Operation

Typhoon, the Germans assembled an enormous force of 1.9 million troops, 48,000

artillery pieces, 1,400 planes, and 1,000 tanks, the latter involving three

Panzer Groups (now renamed Panzer Armies), the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th (the latter

taken from Army Group North). A series

of spectacular victories followed: German 2nd Panzer Army, moving north from

Kiev, took Oryol on October 3 and Bryansk on October 6, trapping 2 Soviet

armies, while German 3rd and 4th Panzer Armies to the north conducted a pincers

attack around Vyazma, trapping 4 Soviet armies.

The encircled Red Army forces resisted fiercely, requiring 28 divisions

of German Army Group Center and two weeks to eliminate the

pockets. Some 500,000–600,000 Soviet

troops were captured, and the first of three lines of defenses on the approach

to Moscow had

been breached. Hitler and the German

High Command by now were convinced that Moscow

would soon be captured, while in Berlin,

rumors abounded that German troops would be home by Christmas.

Some Red Army elements from the Bryansk-Vyazma sector

avoided encirclement and retreated to the two remaining defense lines near

Mozhaisk. By now, the Soviet military

situation was critical, with only 90,000 troops and 150 tanks left to defend Moscow. Stalin embarked on a massive campaign to

raise new armies and transfer formations from other sectors, and move large

amounts of weapons and military equipment to Moscow.

Martial law was declared in the city, and on Stalin’s orders, the

civilian population was organized into work brigades to construct trenches and

anti-tank traps along Moscow’s

perimeter. As well, consumer industries

in the capital were converted to support the war effort, e.g. an automobile plant

now produced light weapons, a clock factory made mine detonators, and machine

shops repaired tanks and military vehicles.

On October 15, 1941, on Stalin’s orders, the state

government, communist party leadership, and Soviet military high command

evacuated from Moscow, and established (temporary) headquarters at Kuibyshev

(present-day Samara). Stalin and a small

core of officials remained in Moscow,

which somewhat calmed the civilian population that had panicked at the

government evacuation, and initially had also hastened to leave the capital.

On October 13, 1941, while mopping up operations continued

at the Bryansk-Vyazma sector, German armored units thrust into the Soviet

defense lines at Mozhaisk, breaking through after four days of fighting, and

taking Kalinin, Kaluga, and then Naro-Fominsk (October 21) and Volokolamsk

(October 27), with Soviet forces retreating to new lines behind the Nara

River. The way to Moscow now appeared open.

In fact, Operation Typhoon was by now sputtering, with

German forces severely depleted and counting only 30% of operational motor

vehicles and 30-50% available troop strength in most units. Furthermore, since nearly the start of

Operation Typhoon, the weather had deteriorated, with the seasonal cold rains

and wet snow turning the unpaved roads into a virtually impassable clayey

morass (a phenomenon known in Russia as “Rasputitsa”, literally, “time without

roads”) that brought German motorized and horse traffic to a standstill. The stoppage in movement also prevented the delivery

to the frontlines of troop reinforcements, supplies, and munitions. On October 31, 1941, with weather and road

conditions worsening, the German High Command stopped the advance, this pause

eventually lasting over two weeks, until November 15. Temperatures also had begun to drop, and the

Germans were yet without winter clothing and winterization supplies for their

equipment, which also were caught up in the weather-induced logistical delay.

Meanwhile, in Moscow, Stalin and the Soviet High Command took

advantage of this crucial delay by hastily organizing 11 new armies and

transferring 30 divisions from Siberia (together with 1,000 tanks and 1,000

planes) for Moscow, the latter being made available following Soviet

intelligence information indicating that the Japanese did not intend to attack

the Soviet Far East. By mid-November

1941, the Soviets had fortified three defensive lines around Moscow, set up artillery and ambush points

along the expected German routes of advance, and reinforced Soviet frontline

and reserve armies. Ultimately, Soviet

forces in Moscow

would total 2 million troops, 3,200 tanks, 7,600 artillery pieces, and 1,400

planes.

On November 15, 1941, cold, dry weather returned, which

froze and hardened the ground, allowing the Wehrmacht to resume its

offensive. For the final push to Moscow,

three panzer armies were tasked with executing a pincers movement: the 2nd in

the south, and the 3rd and 4th in the north, both pincer arms to link up at Noginsk,

40 miles east of Moscow. Then with

Soviet forces diverted to protect the flanks, German 4th Army would attack from

the west directly into Moscow.

In the southern pincer, German 2nd Panzer Army had reached

the outskirts of Tula

as early as October 26, but was stopped by strong Soviet resistance as well as

supply shortages, bad weather, and destroyed roads and bridges. On November 18, while still suffering from

logistical shortages, 2nd Panzer Army attacked toward Tula and made only slow progress, although it

captured Stalinogorsk on November 22. In

late November 1941, a powerful Soviet counter-attack with two armies and

Siberian units inflicted a decisive defeat on German 2nd Panzer Army at

Kashira, which effectively stopped the southern advance.

To the north, German 3rd and 4th Panzer Armies made more

headway, taking Klin (November 24) and Solnechnogorsk (November 25), and on

November 28, crossed the Moscow-Volga Canal, to begin encirclement of the

capital from the north. Wehrmacht troops

also reached Krasnaya Polyana and possibly also Khimki, 18 miles and 11 miles

from Moscow,

respectively, marking the farthest extent of the German advance and also where

German officers using binoculars were able to make out some of the city’s main

buildings.

With both pincers immobilized, on December 1, 1941, German

4th Army attacked from the west, but encountered the strong defensive lines

fronting Moscow,

and was repulsed. Furthermore, by early

December 1941, snow blizzards prevailed and temperatures plummeted to –30°C

(–22°F) to –40°C (–40°F), and German

Army Group

Center, which was

fighting without winter clothing, suffered 130,000 casualties from

frostbite. German tanks, trucks, and

weapons, still not winterized, suffered operational malfunctions in the wintery

conditions. Furthermore, because of poor

weather prevailing throughout much of Operation Typhoon, the Luftwaffe, which

had proved decisive in earlier battles, had so far played virtually no part in

the Moscow

campaign.

The final German push for Moscow was undertaken with greatly depleted

resources in manpower and logistical support, but the German High Command had

hoped that one final fierce and determined attack might overcome the last enemy

resistance. Then with the offensive

failing, the Germans turned to hold onto their positions, and correctly

assessed that the Soviet frontline forces were just as battered, but unaware

that large numbers of Red Army reserve armies were now in place and poised to

go on the offensive.

On December 6, 1941, Soviet forces comprising the Western,

Southwestern, and Kalinin Fronts, with estimates placing total troop strength

at 500,000 to 1.1 million, launched a powerful counter-attack that took the

Germans completely by surprise. The

Soviets initially made slow progress, but soon recaptured Solnechnogorsk on December

12 and Klin on December 15, and with the German lines crumbling, nearly trapped

the German 2nd and 3rd Panzer Armies in separate encirclement maneuvers.

On December 8, 1941, Hitler ordered German forces to hold

their lines, but on December 14, General Franz Halder, head of the German Army

High Command, believing that the frontline could not be held, ordered a limited

withdrawal behind the Oka

River. On December 20, a furious Hitler met with

frontline commanders and rescinded the withdrawal instruction, and ordered that

present lines be defended at all costs.

A heated argument then ensued, with the generals pointing out the

battered conditions of the troops and that German casualties from the cold were

higher than those from actual combat. On

December 25, Hitler dismissed forty high-ranking officers, including General

Heinz Guderian (2nd Panzer Army), General Erich Hoepner (4th Panzer Army), and

General Fedor von Bock (Army

Group Center),

the latter for “medical reasons”. One

week earlier, Hitler had also fired General Walther von Brauchitsch,

Commander-in-Chief of the German Armed Forces, and took over for himself the

control of all German forces and all military decisions.

By late December 1941 to January 1942, the Red Army

counter-offensive was pushing back the Germans north, south, and west of

Moscow, with the Soviets retaking Naro-Fominsk (December 26), Kaluga (December

28), and Maloyaroslavets (January 10).

But on January 7, 1942, the Red Army, soon experiencing manpower losses

and extended supply lines, and increasing German resistance, halted its

offensive, by then having driven back the Wehrmacht some 60-150 miles from Moscow. The Luftwaffe, which thus far had been a

non-factor, took advantage of a break in the weather and took to the skies,

attacking Soviet positions and evacuating trapped German units, and proved

instrumental in averting the complete collapse of Army

Group Center,

which had established new defense lines, including a section, called the Rzhev

Salient, which potentially could threaten Moscow.

November 6, 2020

November 6, 1956 – Suez Crisis: Britain declares a unilateral ceasefire

On November 6, 1956, Britain,

without consulting its allies France and Israel, announced a unilateral

ceasefire, ending nine days of fighting in the Suez Crisis. The reasons for the

British sudden about-face in the midst of the fighting stem from both domestic

and international pressures. In London and other British

cities, anti-war protests and demonstrations immediately broke out after the

war began. The immense public support

for starting war against Egypt

after Nasser seized the Suez Canal had

subsided by the time of the invasion.

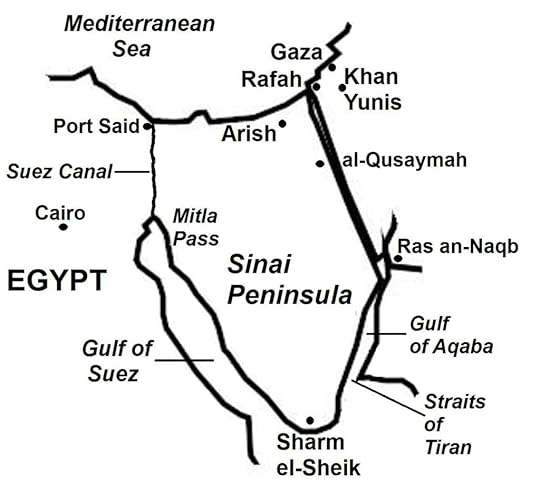

The Suez Crisis was a war between Egypt

against the alliance of Britain,

France, and Israel for control of the politically and

economically vital Suez Canal, a man-modified shipping channel that connects

the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea.

The Suez Crisis was a war between Egypt against the alliance of Britain, France, and Israel for control of the politically and economically vital Suez Canal, a man-modified shipping channel that connects the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea.

The Suez Crisis was a war between Egypt against the alliance of Britain, France, and Israel for control of the politically and economically vital Suez Canal, a man-modified shipping channel that connects the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea.(Taken from Suez Crisis – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background The

Suez Canal in Egypt is a

man-made shipping waterway that connects the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian

Ocean via the Red Sea (Map 7). The Suez Canal was completed by a French

engineering firm in 1869 and thereafter became the preferred shipping and trade

route between Europe and Asia, as it considerably

reduced the travel time and distance from the previous circuitous route around

the African continent. Since 1875, the

facility was operated by an Anglo-French private conglomerate. By the twentieth century, nearly two-thirds

of all oil tanker traffic to Europe passed through the Suez

Canal.

In the late 1940s, a wave of nationalism swept across Egypt,

leading to the overthrow of the ruling monarchy and the establishment of a

republic. In 1951, intense public

pressure forced the Egyptian government to abolish the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of

1936, although the agreement was yet to expire in three years.

With the rise in power of the Egyptian nationalists led by

Gamal Abdel Nasser (who later became president in 1956), Britain agreed to withdraw its military forces

from Egypt

after both countries signed the Anglo-Egyptian Agreement of 1954. The last British troops left Egypt

in June 1956. Nevertheless, the

agreement allowed the British to use its existing military base located near

the Suez Canal for seven years and the possibility of its extension if Egypt

was attacked by a foreign power. The

Anglo-Egyptian Agreement of 1954 and foreign control of the Suez Canal were

resented by many Egyptians, especially the nationalists, who believed that

their country was still under semi-colonial rule and not truly sovereign.

Furthermore, President Nasser was hostile to Israel,

which had dealt the Egyptian Army a crushing defeat in the 1948 Arab-Israeli

War. President Nasser wanted to start

another war with Israel. Conversely, the Israeli government believed

that Egypt was behind the

terrorist activities that were being carried out in Israel. The Israelis also therefore were ready to go

to war against Egypt

to put an end to the terrorism.

Egypt and

Israel sought to increase

their weapons stockpiles through purchases from their main suppliers, the United States, Britain,

and France. The three Western powers, however, had agreed

among themselves to make arms sales equally and only in limited quantities to Egypt and Israel, to prevent an arms race.

Friendly relations between Israel

and France,

however, were moving toward a military alliance. By early 1955, France

was sending large quantities of weapons to Israel. In Egypt,

President Nasser was indignant at the Americans’ conditions to sell him arms:

that the weapons were not to be used against Israel,

and that U.S. advisers were

to be allowed into Egypt. President Nasser, therefore, approached the

Soviet Union, which agreed to support Egypt militarily. In September 1955, large amounts of Soviet

weapons began to arrive in Egypt.

The United States

and Britain

were infuriated. The Americans believed

that Egypt was falling under

the sphere of influence of the Soviet Union,

their Cold War enemy. Adding to this

perception was that Egypt

recognized Red China. Meanwhile, Britain

felt that its historical dominance in the Arab region was being

undermined. The United States and Britain withdrew their earlier

promise to President Nasser to fund his ambitious project, the construction of

the massive Aswan Dam.

Egyptian troops then seized the Suez

Canal, which President Nasser immediately nationalized with the

purpose of using the profits from its operations to help build the Aswan

Dam. President Nasser ordered the

Anglo-French firm operating the Suez Canal to leave; he also terminated the

firm’s contract, even though its 99-year lease with Egypt still was due to

expire in 12 years, in 1968.

The British and French governments were angered by Egypt’s seizure of the Suez

Canal. A few days later, Britain and France

decided to take armed action: their military leaders met and began to prepare

for an invasion of Egypt. In September 1956, France

and Israel also jointly

prepared for war against Egypt.

November 5, 2020

November 5, 1978 – Iranian Revolution: In a TV broadcast, the Shah of Iran acknowledges the ongoing revolution but disapproves of it

On November 5, 1978, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi acknowledged

in a nationwide broadcast the ongoing popular revolution taking place but says

that he disapproved of it. He also pledged to make amends for his mistakes and

work to restore democracy. The following day, he dismissed Prime Minister

Sharif-Emami, replacing him with General Gholam Reza Azhari, a moderate

military officer. The Shah also arrested

and jailed 80 former government officials whom he believed had failed the

country and ultimately were responsible for the current unrest; the loss of his

staunchest supporters, however, further isolated the Shah. Simultaneously, he also released hundreds of

opposition political prisoners.

(Taken from Iranian Revolution – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background Under

the Shah, Iran developed

close political, military, and economic ties with the United States, was firmly West-aligned and

anti-communist, and received military and economic aid, as well as purchased

vast amounts of weapons and military hardware from the United States. The Shah built a powerful military, at its

peak the fifth largest in the world, not only as a deterrent against the Soviet

Union but just as important, as a counter against the Arab countries

(particularly Iraq), Iran’s traditional rival for supremacy in the Persian Gulf

region. Local opposition and dissent

were stifled by SAVAK (Organization of Intelligence and National Security;

Persian: Sāzemān-e Ettelā’āt va Amniyat-e Keshvar), Iran’s CIA-trained intelligence and

security agency that was ruthlessly effective and transformed the country into

a police state.

Iran, the

world’s fourth largest oil producer, achieved phenomenal economic growth in the

1960s and 1970s and more particularly after the 1973 oil crisis when world oil

prices jumped four-fold, generating huge profits for Iran that allowed its government to

embark on massive infrastructure construction projects as well as social

programs such as health care and education.

And in a country where society was both strongly traditionalist and

religious (99% of the population is Muslim), the Shah led a government that was

both secular and western-oriented, and implemented programs and policies that

sought to develop the country based on western technology and some aspects of

western culture. Iran’s push to

westernize and secularize would be major factors in the coming revolution. The initial signs of what ultimately became a

full-blown uprising took place sometime in 1977.

At the core of the Shiite form of Islam in Iran is the

ulama (Islamic scholars) led by ayatollahs (the top clerics) in a religious

hierarchy that includes other orders of preachers, prayer leaders, and cleric

authorities that administered the 9,000 mosques around the country. Traditionally, the ulama was apolitical and

did not interfere with state policies, but occasionally offered counsel or its

opinions on government matters and policies.

In January 1963, the Shah launched sweeping major social and

economic reforms aimed at shedding off the country’s feudal, traditionalist

culture and to modernize society. These

ambitious reforms, known as the “White Revolution”, included programs that

advanced health care and education, and the labor and business sectors. The centerpiece of these reforms, however,

was agrarian reform, where the government broke up the vast agriculture

landholdings owned by the landed few and distributed the divided parcels to

landless peasants who formed the great majority of the rural population. While land reform achieved some measure of

success with about 50% of peasants acquiring land, the program failed to win

over the rural population as the Shah intended; instead, the deeply religious

peasants remained loyal to the clergy.

Agrarian reform also antagonized the clergy, as most clerics belonged to

wealthy landowning families who now were deprived of their lands.

Much of the clergy did not openly oppose these reforms,

except for some clerics in Qom

led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who in January 22, 1963 denounced the Shah

for implementing the White Revolution; this would mark the start of a long

antagonism that would culminate in the clash between secularism and religion

fifteen years later. The clerics also

opposed other aspects of the White Revolution, including extending voting

rights to women and allowing non-Muslims to hold government office, as well as

because the reforms would reduce the cleric’s influence in education and family

law. The Shah responded to Ayatollah

Khomeini’s attacks by rebuking the religious establishment as being old-fashioned

and inward-looking, which drew outrage from even moderate clerics. Then on June 3, 1963, Ayatollah Khomeini

launched personal attacks on the Shah, calling the latter “a wretched,

miserable man” and likening the monarch to the “tyrant” Yazid I (an Islamic

caliph of the 7th century). The

government responded two days later, on June 5, 1963, by arresting and jailing

the cleric.

Ayatollah Khomeini’s arrest sparked strong protests that

degenerated into riots in Tehran, Qom, Shiraz,

and other cities. By the third day, the

violence had been quelled, but not before a disputed number of protesters were

killed, i.e. government cites 32 fatalities, the opposition gives 15,000, and

other sources indicate hundreds.

Ayatollah Khomeini was released a few months later. Then on October 26, 1964, he again denounced

the government, this time for the Iranian parliament’s recent approval of the

so-called “Capitulation” Bill, which stipulated that U.S.

military and civilian personnel in Iran, if charged with committing criminal

offenses, could not be prosecuted in Iranian courts. To Ayatollah Khomeini, the law was evidence

that the Shah and the Iranian government were subservient to the United States. The ayatollah again was arrested and

imprisoned; government and military leaders deliberated on his fate, which

included execution (but rejected out of concerns that it might incite more

unrest), and finally decided to exile the cleric. In November 1964, Ayatollah Khomeini was

forced to leave the country; he eventually settled in Najaf, Iraq,

where he lived for the next 14 years.

While in exile, the cleric refined his absolutist version of

the Islamic concept of the “Wilayat al Faqih” (Guardianship of the

Jurisprudent), which stipulates that an Islamic country’s highest spiritual and

political authority must rest with the best-qualified member (jurisprudent) of

the Shiite clergy, who imposes Sharia (Islamic) Law and ensures that state

policies and decrees conform with this law.

The cleric formerly had accepted the Shah and the monarchy in the

original concept of Wilayat al Faqih; later, however, he viewed all forms of

royalty incompatible with Islamic rule.

In fact, the ayatollah would later reject all other (European) forms of

government, specifically citing democracy and communism, and famously declared

that an Islamic government is “neither east nor west”.

Ayatollah Khomeini’s political vision of clerical rule was

disseminated in religious circles and mosques throughout Iran from audio

recordings that were smuggled into the country by his followers and which was

tolerated or largely ignored by Iranian government authorities. In the later years of his exile, however, the

cleric had become somewhat forgotten in Iran, particularly among the

younger age groups.

Meanwhile in Iran,

the Shah continued to carry out secular programs that alienated most of the

population. In October 1971, to

commemorate 25 centuries since the founding of the Persian Empire, the Shah

organized a lavish program of activities in Persepolis, capital of the First Persian

Empire. Then in March 1976, the Shah

announced that Iran

henceforth would adopt the “imperial” calendar (based on the reign of Persian

king Cyrus the Great) to replace the Islamic calendar. These acts, considered anti-Islamic by the clergy

and many Iranians, would form part of the anti-royalist backlash in the coming

revolution.

November 3, 2020

November 3, 1969 – Vietnam War: President Nixon delivers his “silent majority” speech

On November 3, 1969, U.S. President Richard Nixon addressed the nation on television and radio in what became known as the “silent majority” speech. In his address, Nixon stated “…to you, the great silent majority of my fellow Americans—I ask for your support”, in reference to the ongoing Vietnam War. Nixon was continuing his predecessor President Lyndon B. Johnson’s program of “Vietnamization”, that is, gradual American disengagement from the war, with the South Vietnamese military gradually taking over the fighting after a period of being built up. During his campaign for president, Nixon had stated that he had a “secret plan” to end the war, which anti-war advocates believed was a quick end of American involvement in Vietnam. But once in office, Nixon continued with the United States being involved in the war, stating that a sudden withdrawal “would result in a collapse of confidence in American leadership”, and that “a nation cannot remain great if it betrays its allies and lets down its friends”.

In October 1969, protesters staged a giant rally in Washington, D.C., prompting President Nixon to address the nation on November 3 with his “silent majority” speech. In it, he stated that the United States must continue with gradual disengagement from the war to achieve “peace with honor”. He concluded by appealing to the “great silent majority” for support. A White House official later stated that “silent majority” refers to “a large and normally undemonstrative cross-section of the country that…refrained from articulating its opinions on the war”. Nixon also said that he would not be “dictated by a minority staging demonstrations in the streets”.

Southeast Asia during the 1960s

Southeast Asia during the 1960s(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Nixon and the Vietnam

War In 1969, newly elected U.S.

president, Richard Nixon, who took office in January of that year, continued

with the previous government’s policy of American disengagement and phased

troop withdrawal from Vietnam,

while simultaneously expanding Vietnamization, with U.S. military advice and material

support. He also was determined to

achieve his election campaign promise of securing a peace settlement with North Vietnam under the Paris

peace talks, ironically through the use of force, if North Vietnam refused to negotiate.

In February 1969, the Viet Cong again launched a large-scale

Tet-like coordinated offensive across South Vietnam, attacking villages,

towns, and cities, and American bases.

Two weeks later, the Viet Cong launched another offensive. Because of these attacks, in March 1968, on

President Nixon’s orders, U.S.

planes, including B-52 bombers, attacked Viet Cong/North Vietnamese bases in

eastern Cambodia

(along the Ho Chi Minh Trail). This

bombing campaign, codenamed Operation Menu, lasted 14 months (until May 1970),

and segued into Operation Freedom Deal (May 1970-August 1973), with the latter

targeting a wider insurgent-held territory in eastern Cambodia.

In the 1954 Geneva Accords, Cambodia had declared its

neutrality in regional conflicts, a policy it maintained in the early years of

the Vietnam War. However, by the early

1960s, Cambodia’s reigning

monarch, Norodom Sihanouk, came under great pressure by the escalating war in Vietnam, and especially after 1963, when North

Vietnamese forces occupied sections of eastern Cambodia

as part of the Ho Chi Minh Trail system to South Vietnam. Then in the mid-1960s, Sihanouk signed

security agreements with China

and North Vietnam, where in

exchange for receiving economic incentives, he acquiesced to the North

Vietnamese occupation of eastern Cambodia. He also allowed the use of the port of Sihanoukville

(located in southern Cambodia)

for shipments from communist countries for the Viet Cong/NLF through a newly

opened land route across Cambodia. This new route, called the Sihanouk Trail

(Figure 5) by the Western media, became a major alternative logistical system

by North Vietnam

during the period of intense American air operations over the Laotian side of

the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

In July 1968, under strong local and regional pressures,

Sihanouk re-opened diplomatic relations with the United States, and his government

swung to being pro-West. However, in March

1970, he was overthrown in a coup, and a hard-line pro-U.S. government under

President Lon Nol abolished the monarchy and restructured the country as the Khmer Republic.

For Cambodia, the

spill-over of the Vietnam War into its territory would have disastrous

consequences, as the fledging communist Khmer Rouge insurgents would soon

obtain large North Vietnamese support that would plunge Cambodia into a full-scale civil

war. For the United States (and South

Vietnam), the pro-U.S. Lon Nol government served as a green light for American

(and South Vietnamese) forces to conduct military operations in Cambodia.

The U.S.

bombing operations on Viet Cong/North Vietnamese bases in eastern Cambodia forced North

Vietnam to increase its military presence in other parts

of Cambodia. The North Vietnamese Army seized control

particularly of northeastern Cambodia,

where its forces defeated and expelled the Cambodian Army. Then in response to the Cambodian

government’s request for military assistance, starting in late April to early

May 1970, American and South Vietnamese forces launched a major ground

offensive into eastern Cambodia. The main U.S. objective was to clear the

region of the North Vietnamese/Viet Cong in order to allow the planned American

disengagement from the Vietnam War to proceed smoothly and on schedule. The offensive

also served as a gauge of the progress of Vietnamization, particularly

the performance of the South Vietnamese Army in large-scale operations.

In the nearly three-month successful operation (known as the

Cambodian Campaign) which lasted until July 1970, American and South Vietnamese

forces, which at their peak numbered over 100,000 troops, uncovered several

abandoned major Viet Cong/North Vietnamese bases and dozens of underground storage

bunkers containing huge quantities of materiel and supplies. In all, American and South Vietnamese troops

captured over 20,000 weapons, 6,000 tons of rice, 1,800 tons of ammunition, 29

tons of communications equipment, over 400 vehicles, and 55 tons of medical

supplies. Some 10,000 Viet Cong/North

Vietnamese were killed in the fighting, although the majority of their forces

(some 40,000) fled deeper into Cambodia. However, the campaign failed to achieve one

of its objectives: capturing the Viet Cong/NLF leadership COSVN (Central Office

for South Vietnam). The Nixon administration also came under

domestic political pressure: in December 1970, and U.S. Congress passed a law

that prohibited U.S. ground forces from engaging in combat inside Cambodia and Laos.

Before the Cambodian Campaign began, President Nixon had

announced in a nationwide broadcast that he had committed U.S. ground troops to the

operation. Within days, large

demonstrations of up to 100,000 to 150,000 protesters broke out in the United States,

with the unrest again centered in universities and colleges. On May 4, 1970, at Kent State University, Ohio,

National Guardsmen opened fire on a crowd of protesters, killing four people

and wounding eight others. This incident

sparked even wider, increasingly militant and violent protests across the

country. Anti-war sentiment already was

intense in the United States

following news reports in November 1969 of what became known as the My Lai

Massacre, where U.S. troops

on a search and destroy mission descended on My Lai

and My Khe villages and killed between 347 and 504 civilians, including women

and children.

American public outrage further was fueled when in June

1971, the New York Times began publishing the “Pentagon Papers” (officially

titled: United States

– Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense),

a highly classified study by the U.S. Department of Defense that was leaked to

the press. The Pentagon Papers showed

that successive past administrations, including those of Presidents Truman,

Eisenhower, and Kennedy, but especially of President Johnson, had many times

misled the American people regarding U.S.

involvement in Vietnam. President Nixon sought legal grounds to stop

the document’s publication for national security reasons, but the U.S. Supreme

Court subsequently decided in favor of the New York Times and publication

continued, and which was also later taken up by the Washington Post and other

newspapers.

As in Cambodia,

the U.S. high command had

long desired to launch an offensive into Laos to cut off the logistical

portion of the Ho Chi Minh Trail system located there. But restrained by Laos’ official neutrality,

the U.S. military instead carried out secret bombing campaigns in eastern Laos

and intelligence gathering operations (the latter conducted by the top-secret

Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group, MACV-SOG

that involved units from Special Forces, Navy SEALS, U.S. Marines, U.S. Air

Force, and CIA) there.

The success of the Cambodian Campaign encouraged President

Nixon to authorize a similar ground operation into Laos. But as U.S. Congress had prohibited American

ground troops from entering Laos,

South Vietnamese forces would launch the offensive into Laos with the objective of destroying the Ho Chi

Minh Trail, with U.S. forces

only playing a supporting role (and remaining within the confines of South Vietnam). The operation also would gauge the combat

capability of the South Vietnamese Army in the ongoing Vietnamization program.

November 2, 2020

November 2, 1949 – The Netherlands and Indonesian revolutionary government establish the United States of Indonesia

Indonesia in Southeast Asia. During its colonial period, Indonesia was known as the Dutch East Indies.

Indonesia in Southeast Asia. During its colonial period, Indonesia was known as the Dutch East Indies.(Taken from Indonesian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

By late 1946, the British military had completed its mission in the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia), that of repatriating Japanese forces to Japan and freeing the Allied prisoners of war following the end of World War II. By December 1946, British forces had departed from the islands, but not before setting up mediation talks between the Dutch government (which wanted to restore colonial rule) and the Indonesian revolutionaries (which desired independence), an initiative that led the two sides to agree to a ceasefire in October 1946. Earlier in June 1946, the Dutch government and representatives of ethnic and religious groups and the aristocracy from Sulawesi, Maluku, West New Guinea, and other eastern states met in South Sulawesi and agreed to form a federal-type government attached to the Netherlands. In talks held with the Indonesian revolutionaries, Dutch authorities presented a similar proposal which on November 12, 1946, produced the Linggadjati Agreement, where the two sides agreed to establish a federal system known as the United States of Indonesia (USI) by January 1, 1949. The Republic of Indonesia (consisting of Java, Madura, and Sumatra) would comprise one state under USI; in turn, USI and the Netherlands would form the Netherlands-Indonesian Union, with each polity being a fully sovereign state but under the symbolic authority of the Dutch monarchy.

This Agreement met strong opposition in the Indonesian

government but eventually was ratified in February 1947 with strong pressure

for its passage being exerted by Sukarno and Hatta. In December 1946 in South

Sulawesi, Pemuda fighters who opposed the agreement restarted

hostilities. Dutch forces, led by

Captain Raymond Westerling, used brutal methods to quell the rebellion, killing

some 3,000 Pemuda fighters. The

Agreement also was resisted in the Netherlands, but in March 1947, a

modified version was passed in the House of Representatives of the Dutch

parliament.

Then in July 1947, declaring that the Indonesian government

did not fully comply with the Agreement, Dutch forces launched Operation

Product, a military offensive (which the Dutch government called a “police

action”) in Java and Sumatra, seizing control of the vital economic regions,

including sugar-producing areas in Java, and the rubber plantations in Medan,

and petroleum and coal facilities in Palembang and Padang. Dutch ships also imposed a naval blockade of

the ports, restricting the Indonesian

Republic’s economic

capacity.

In early 1947, acting on the diplomatic initiative of India and Australia, the United Nations

Security Council (UNSC) released Resolution 27, which called on the two sides

to stop fighting and enter into peaceful negotiations. On August 5, 1947, a ceasefire came into

effect. A stipulation in Resolution 27 established the Committee of Good Office

(CGO), a three-person body consisting of representatives, one named by the Netherlands, another by Indonesia, and

a third, mutually agreed by both sides.

In subsequent negotiations, the two sides agreed to form the Van Mook

Line to delineate their respective areas of control which, because of the

fighting, the Dutch-held territories in Java and Sumatra increased, while those

of the Indonesian

Republic decreased.

In January 1948, the two sides signed the Renville Agreement

(named after the USS Renville, a U.S. Navy ship where the negotiations were

held), which confirmed their respective territories in the Van Mook Line, and

in the Dutch-held areas, a referendum would be held to decide whether the

residents there wanted to be under Indonesian or Dutch control. Furthermore, in exchange for Indonesian

forces withdrawing from Dutch-held areas as stipulated in the Van Mook Line,

the Dutch Navy would end its blockade of the ports.

The Indonesian Republic, already weakened politically and

militarily, was undermined further when its Islamic supporters in now

Dutch-controlled West Java objected to the Renville Agreement and broke away to

form Darul Islam (“Islamic State”), with the ultimate aim of turning Indonesia

into an Islamic country. It opposed both

the Indonesian government and Dutch colonial authorities. Darul Islam subsequently would be defeated

only in 1962, some 13 years after the war had ended.

The Indonesian Republic also faced opposition from its other

erstwhile allies, the communists (of the Indonesian Communist Party) and the

socialists (of the Indonesian Socialist Party), who in September 1948, seceded

and formed the “Indonesian Soviet Republic”

in Madiun, East Java. Fighting in September-October and continuing

until December 1948 eventually led to the Indonesian Republic

quelling the Madiun uprising, with tens of thousands of communists killed or

imprisoned and their leaders executed or forced into exile. Furthermore, the Indonesian Army itself was

plagued with internal problems, because the government, suffering from acute

financial difficulties and unable to pay the soldiers’ salaries, had disbanded

a number of military units.

With the Indonesian revolutionary government experiencing

internal problems, on December 19, 1948, Dutch forces launched Operation Kraai

(“Operation Crow”), another “police action” on the contention that Indonesian

guerillas had infiltrated the Van Mook Line and were carrying out subversive

actions inside Dutch-held areas in violation of the Renville Agreement. Operation Kraai caught the revolutionaries

off guard, forcing the Indonesian Army to retreat to the countryside to avoid

being annihilated. As a result, Dutch

forces captured large sections of Indonesian-held areas, including the

Republic’s capital, Yogyakarta. Sukarno, Hatta, and other Republican leaders

were captured without resistance and exiled, this action being deliberate on

their part, as they believed that this latest aggression by the Dutch military

would be condemned by the international community. Before allowing himself to be captured,

Sukarno activated a clandestine “emergency government” in West

Sumatra (to act as a caretaker government), which he had arranged

beforehand as a contingency measure.

On December 24, 1948, the UNSC passed Resolution 63 which

demanded the end of hostilities and the immediate release of Sukarno and other

Indonesian leaders. Also by this time,

the international media had taken hold of the conflict. The United

States also exerted pressure on the Dutch government,

threatening to cut off Marshall Plan aid for the Netherlands’ post-World War II

reconstruction. Operation Kraii also

generated division within USI as the Cabinets of Dutch-controlled states of East Indonesia and Pasundan resigned in protest of the

Dutch military actions. As a result of these pressures, a ceasefire was agreed

by the two sides, which came into effect in Java (on December 31, 1948) and Sumatra (on January 5, 1949).

November 1, 2020

November 1, 1922 – The new nation of Turkey abolishes the Ottoman Sultanate

On October 29, 1923, the Republic of Turkey was established with Ankara as its capital and Mustafa Kemal as first president. This followed the successful Turkish War of Independence. One year earlier, on November 1, 1922, the Grand National Assembly (the Turkish national parliament), abolished the Ottoman Sultanate, forcing the Sultan Mehmed VI to abdicate and leave for exile abroad. The Ottoman Empire ended, and 600 years of Ottoman dynastic rule came to an end. In March 1924, the Caliphate was abolished, and Turkey transitioned into a secular, democratic state, which it is to this day.

The Ottoman Empire at its peak territorial extent

The Ottoman Empire at its peak territorial extent (Taken from The Ottoman Empire – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

History The imperial Islamic power known as the Ottoman Empire has its origin as one of many semi-independent Turkish tribal states (called beyliks) that formed during the breakdown and collapse of the Seljuk Turkish Empire. Founded by Osman I (whose name was anglicized to Ottoman and from whom the empire derived its name), the Ottoman beylik achieved sovereignty from the Seljuk Sultanate in 1299. With the influx of large numbers of Ghazi warriors (both Muslims and Christians) into his beylik, Osman built an army hoping to expand his domain at the expense of the tottering Byzantine Empire* situated to the west of his beylik.

In 1324, the Ottomans captured Bursa,

where they established their new capital; Bursa’s

fall also ended the Byzantine Empire’s presence in Anatolia. On Osman’s death in 1326, the succession of

Ottoman rulers, first by Osman’s son Orhan, continued to expand the emerging

empire. In 1387, Thessalonica was taken,

marking the Ottomans’ first entry into Europe

(via the southeast), a presence that would last, except for a brief pause, for

six centuries. Further expansion into

Balkan Europe continued during the second half of the 1300s with the defeats of

the Serbian and Bulgarian empires, and annexation of sections of what comprise

modern-day Serbia, Bulgaria, Macedonia,

and Albania.

In 1402, Ottoman power was briefly eclipsed when Tamerlane,

the Turkic-Mongol conqueror, invaded Anatolia. Bayezid, the Ottoman ruler, was captured by

Tamerlane in battle, starting a turbulent period in the Ottoman court known as

the Ottoman Interregnum. After an

eleven-year power struggle among Bayezid’s sons for succession to the throne,

Mehmed I prevailed and became the new sultan.

With its leadership crisis resolved, the Ottomans resumed their campaign

in Europe, recapturing parts of the Balkans

that had been lost during the interregnum.

By the mid-fifteenth century, Constantinople, the Byzantine Empire’s capital, had been surrounded by

Ottoman territories. In early April

1453, the Ottomans launched an attack on the city, starting a six-week siege on

the nearly impregnable fortress that was protected by two layers of defensive

stone walls. On May 29, 1453, the walls

were breached, and Constantinople fell. The Ottomans then moved their capital to Constantinople.

Constantinople’s fall sent shock waves across Western Europe, which at that time was made up of many

small rival Christian kingdoms, duchies, and principalities, and which all

feared falling under Muslim rule. The

Ottomans advanced further into Europe with the invasion of lands that comprise

present-day Bulgaria, Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina,

Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro,

and Albania. Other conquests also were made in parts of

modern-day Hungary and Romania. The invasion of Greece

began with the capture of Athens

in 1458; by the end of the century, most of the Greek mainland had been

taken. By the first quarter of the

sixteenth century, nearly all of the Balkans and some sections of eastern and

central Europe were under Ottoman

control. However, two attempts (in 1529

and 1532) to take Vienna failed, which were

resisted by the combined forces of the Habsburg monarchy of Austria and its Christian allies.

Under the rule of Suleiman the Magnificent, the Ottomans

reached the height of their power. In

Anatolia, other Turkish beyliks were defeated, making the Ottoman Sultan the

master of Asia Minor. Suleiman’s forces also advanced into western

Asia and northern Africa, incorporating more

territories to those previously won under the previous rulers, Mehmed II and

Selim I. In the east, Mesopotamia

(present-day Iraq) also was

taken, while in the south, the Ottomans advanced into the Arabian

Peninsula.

Ottoman

expansion continued up to the mid-seventeenth century. By then, the empire extended from Baghdad to Algeria