Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 924

December 13, 2015

They’re just trying to scare you: The GOP’s long history of bizarre, make-believe enemies

In the wake of the Paris terrorist attacks, the entire GOP is following the fear-based pathway Donald Trump first blazed against undocumented immigrants from Mexico, in which all manner of different fears get jumbled together as if they were all just parts of one grand conspiracy against “real Americans.” The idea that Syrian refugees pose a mortal danger that Obama is nefariously ignoring (or possibly even aiding) is symptomatic of a more general tendency to arbitrarily weave together the most unlikely combination of real and imaginary threats into a pseudo-coherent whole whose logic bears no resemblance at all to anything in the real world, while preserving one constant — the central focus on the self-identified victims and their struggle to maintain holy virtue.

But there's nothing new in this. In fact, it taps into a deep foundational aspect of our national psyche, forged in colonial times in Puritan New England, given form specifically by Cotton Mather, building on the early popular narrative form of captivity narratives, as described by historian Richard Slotkin in his 1973 book "Regeneration Through Violence." Captivity narratives were America's first popular literary genre, based on the capture of colonists by warring Native tribes, which claimed more than 1,000 victims in 17th and 18th century Puritan New England. Mather — based on his encounter with Mercy Short, a 17-year-old captivity survivor — took the captivity framework, and used it directly to explain witchcraft-induced demonic possession (“captivity by specters”), as well as a host of other threats facing Puritan New England at the time.

To understand what Mather did, we need to begin with the captivity narratives he generalized from. Mary Rowlandson's "The Soveraignty & Goodness of God...a Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration" (1682) was the first and by far the most widely distributed book devoted to a single captivity,” Slotkin notes, but its cultural potency inevitably led to its narrative appropriation over time. “By the late 1740s the captivities had become so much a part of the New England way of thinking that they provided a symbolic vocabulary to which preachers would refer almost automatically in any attempt at stirring a revival of religious sentiments. Even Jonathan Edward's 'Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,' [text here] the most perfect of the revival sermons, employs images from the captivities.”

The cultural resonance of the narratives has a straightforward explanation: On the one hand, the fear of capture was objectively quite realistic, on the other hand, the interpretive framework deployed throughout profoundly reflected both the broad assumptions of Puritan theology and the specific inflections of spiritual anxieties that developed in the New England Puritan community at the time. These resulted from their experience after having gained a foothold in the New World, establishing a degree of comfort and complacency that leaders like Mather, particularly, found deeply troubling.

“Mrs. Rowlandson's captivity begins typically, with the heroine-victim in a state of relatively complacent ease,” Slotkin wrote. “She is only vaguely troubled by her easy situation, vaguely wondering why God does not 'try' her in some way. Others of her acquaintance have been so tried, and some had fallen, the Bible promises that all will be tried and should be prepared." She knows this in her head, as it were, but not in her heart, she “has forgotten the true meaning of these warnings and portents.” Falling into captivity, she then experiences trials she once vaguely wished for, only to be dramatically traumatized, tested and transformed by them, ending up in a place she was always meant to be, in one sense, yet, at the same time subtly alienated from the bosom of her community, purportedly based on that very worldview she now most fully realizes.

The threat of captivity was more vivid and varied than merely the threat of death:

Indian captivity was almost certain to result in spiritual and physical catastrophe. The captives either vanished forever into the woods, or returned half-Indianized or Romanized, or converted to Catholicism and stayed in Canada, or married some “Canadian half-breed” or “Indian slut,” or went totally savage. In any of these cases, the captive was a soul utterly lost to the tents of the English Israel.

The ease Rowlandson experienced before her captivity represented a falling away from the “very reason that the Puritan emigrants had come to America, seeking a hard way to do the Lord's work,” a falling away that greatly troubled their leaders, more than anyone else. Hence, the captivity narrative was, in its own culturally specific way, a restoration narrative: it articulated a restoration of the state of self-evident risk and peril — entrusting their fate to God's hand — which the Puritans embraced in departing the Old World for New England in the first place. As Slotkin writes, “the captivity experience, with its pains and trials, brings a forced end to comforts and pleasures. The cross is thrust upon the Christian—to love it, accept it, and be saved; or to rail against it and perish.”

The combination of being grounded in a real world threat on the one hand, and in their own shared theology and group psychology on the other, made for the incredibly potency and coherent internal logic of the captivity narrative form. It both made sense of the the real world threat they faced, and demonstrated the proof of their theological outlook at the same time—a self-reinforcing double confirmation. Because of this, it was only logical that the narrative “about” the outside world could then be turned inward as well to make sense of the witchcraft experience, as a form of “captivity by specters,” particularly in the case of Mercy Short, who had already been through the actual captivity experience, two years earlier, at the age of 15. Her parents and siblings were killed in the process, a harrowing experience which could easily give rise to prolonged traumatic episodes afterward, two of which she indeed experienced, and Mather interpreted, after his fashion:

Mather clearly regarded Mercy Short's case as an archetype of New England's condition, and he presented it as such in "A Brand Pluck'd Out of the Burning" [text here]—a narrative of his dealings with the girl that was widely circulated in manuscript. The structural pattern invoked in this account is clearly that of the captivity narrative; but here it is transformed into a ritual exorcism of an Indian-like demon from the body of the white, female “Saint.”

But Mather went even further than this in his systematic integration, which he had been groping toward for some time:

Mather had long been preparing for just such a confrontation with the devil. He was then at work on the gathering and systematizing of historical and theological materials that was to culminate in his masterwork, the Magnalia Chrisi Americana. That massive work was to be the history of New England “under the aspect of Eternity”; it would explicate the New England experience in terms of a total world view in which Puritans and Indians would find their true valuation and be placed in the context of the divine drama of history, as it unfolds from Eden to Calvary to Boston to Apocalypse.

Puritans like Mather were not just confronted by Native Americans, however. They were hemmed in by a whole panoply of enemy others:

His confrontation with Mercy Short's devils clarified issues for him and enabled him to draw connections between the several “assaults” on pious New England that he and his father had resisted for years: the assaults of the Indians and of frontier paganism, the assaults of ministerial frauds and heretics, the assaults of the Quakers, the assaults of the royal governor on colonial prerogatives, and the final assault of the witches and the Invisible Kingdom in 1692. Mercy Short helped Mather discover that the common pattern in each of these assaults was precisely that of the captivity narrative: a devilish visitation, an enforced sojourn in evil climes under the rule of man-devils, and an ultimate redemption of body and soul through the interposition of divine grace and the perseverance of the victim in orthodox belief.

Of course, the Quakers, in particular, really didn't come anywhere close to fitting into this narrative framework in any realistic sense. But given the intensity of captivity experience, the fears it generated, and the relatively straightforward logic of transposing it onto “specters,” who was really going to be in a position to question the logic or point out its flaws when applied more generally, or to Quakers in particular? After all, if you did raise questions, you were probably a hidden Quaker yourself! And so, as Slotkin goes on to say:

In the years following his treatment of Mercy Short, Mather's several books on the witchcraft trials, his study of the Indian wars (Decennium Luctuosum, 1699), and his Magnalia translated the myth-structure inherent in the captivity narrative into a coherent vision of his culture's history.

Although it's objectively true that Quakers didn't really fit his template, that doesn't mean he couldn't craft a compelling and coherent narrative implicating them in a larger web of villainy:

He makes it clear that, for him, the Indian wars are one phase of the continuing war between Satan and Christ. In the strategy of that war Indian attacks, the “visitation” of specters, devils, and witches in 1692, and the growth of “heretical” sects on the frontier are related phenomena, are pieces in Satan's grand design of conquest. Thus he concludes his study of the Indian attacks with a diatribe against the Quakers. He equates them with the Indians, partly because of their opposition to English usurpation of Indian lands, but primarily because of their doctrine of human freedom and the inner light—their tenet that Christ is contained within each man [not to mention woman!] and that pure introspection, without inhibition by books and creeds, can yield personal revelation. This tenet Mather equates with the beliefs of the Mohamedan sect of Assassins, or “Betenists,” “who were the Enthusiasts that followed the Light within, like our Quakers; and on this principle... did such Numberless Villainies.”

Radical Islamic terrorists! As I live and breathe! I told you that there was nothing new in the GOP's current tendency to arbitrarily weave together the most unlikely combination of real and imaginary threats into a pseudo-coherent whole.

In fact, Quakers in that time were actually somewhat analogous to today's secular humanists, at least in regard to matters of religious tolerance—which was part of the reason they had much better relations with Native American tribes than the Puritans had. (They also didn't steal land.) To associate them with Islamic terrorists was thus eerily similar to today's conservatives' efforts to portray American secular liberals as allies of the terrorists who attack us, supporters of secret Sharia law, etc., particularly given that there was zero Muslim presence in New England at the time. But religious intolerance was key to their faith, so open-mindedness was as threatening to it as any other contrary faith, perhaps even moreso.

I've only just touched on certain highlights of Slotkin's account; there's a great deal more from that time of early American terror that seems eerily relevant today. I'd like to mention just four more, to help expand the sense of how much we have in common with them, how little we've changed at some deep level, and how much there is to question in what we've come to take for granted.

First, there are two points made by Susan Faludi in her 2007 book, "The Terror Dream: Myth and Misogyny in an Insecure America." First, Faludi homes in on the blame-shifting dynamic, something particularly apt to keep in mind, given who was in charge on 9/11, and who launched the endless “war on terror” in response:

Associating colonial defeats in the Indian wars with witchcraft served many purposes, notably among them the elision of another, more worldly explanation. The colonial leaders, including a number of judges on the Court of Oyer and Terminer who prosecuted the witches, were themselves complicit in the Second Indian War's disastrous outcome — through unpreparedness, avarice, mistaken strategy of sheer ineptitude. And eager to deflect attention from their own failures and locate the cause of vulnerability elsewhere.

Second, Faludi points out that the blame-shifting is deeply gendered — “the leadership ducking its culpability was entirely male, its newly identified antagonists overwhelmingly female”—and that threats to male supremacy and reactions to them permeate the entire subject of New England witchcraft. First, she notes:

Before the recent onset of feminist scholarship the various speculations [on causes of the witch trials] made little of the overwhelming presence of women among the defendants: 11 of the 18 people accused, 52 of the 59 tried, 26 of the 31 convicted and 14 of the 19 hung were female....

She then goes on to note “there was a definite character to the women singled out for witchcraft accusations in New England,” contrasting the European tendency to target “poor villagers, easy to scapegoat because they were without resources” with the relatively high status of the New England accused, as first documented by Carol Karlsen in "The Devil in the Shape of a Woman." Moreover, “they were beyond the dictates of patriarchal family and society and, especially damning, were inclined to defend their unfettered state. A substantial majority of the accused were older women who had no brothers, sons, or children; of the executed female witches, 89 percent were women from families with no male heirs. That is to say, they stood to inherit and so disrupted male control of the purse strings.”

Faludi has a good deal more to say on the gender dynamics surrounding the warfare/witchcraft connection. The fact that male protection so often failed and female initiative proved vital, even heroic was profoundly unsettling, but hardly surprising given the realities of frontier life. Traditional female role models require a far more secure social setting in order to be even superficially plausible. No matter what century, frontier women have to be brave, resourceful, at times even heroic. It comes with the territory, whether men like it or not.

Third, there's something else Slotkin doesn't mention, but that should be obvious: that the Puritan's captivity fears were in some sense a matter of “envious reversal,” as I've written about recently, a switching of roles of victim and aggressor. It was, after all, the Puritans who were capturing the Native Americans' whole world, the entire continent on which they lived. This is far more obvious to us today, of course. But they were in the early stages of an ongoing genocide of unprecedented proportions, a genocide that America continues to habitually ignore, and so it seems a bit rich, to say the least, that the Puritans built up an entire worldview based on themselves as victims in this situation.

Which isn't to deny the obvious: Puritans often were victims of specific horrific acts. Mercy Short, in particular: “She had been captured by the Indians at her home in Salmon Falls when she was fifteen. Her father and mother and three of their children were murdered before her eyes, and she herself was carried to Canada.” Yet, the Quakers managed to avoid the whole war experience almost entirely, primarily by not waging war themselves.

What's more, this also isn't to say that Native Americans didn't already take one another captive, which brings us to our fourth and final point: They had a profoundly different way of dealing with captivity trauma, which in turn sheds light on the Puritan approach as a form of eliminationist psychoanalytical technique, in turn reflecting seeds of genocidal ideation. Contrasting the two psychological approaches more broadly, Slotkin writes:

Mather entered the wilderness of the human mind bent on extirpating its “Indians,” exorcising its demons. These Indian-demons were the impulses of the unconscious—the sexual impulses, the obscure longings and hatreds that mark parent-child relationships, the proddings of a deep-rooted sense of guilt. The goal of his therapy was to eliminate these impulses, to cleanse the mind of them utterly, to purge it and leave it pure. In much the same way he wished to purge the real wilderness of Indians, to raze it to ashes and build an utterly new world, uncorrupted by a primitive past, on the blank of the old.

The Indian attitude toward the mind likewise resembled their attitude toward the wilderness. Just as they worshiped every aspect of creation and creaturliness, whether it represented what they called good or what they called evil, so they accepted every revelation of the dreaming mind as a message from a god within, a world spirit manifested in the individual. They responded to the dreams of the individuals as a community, seeking to assimilate the dream-message into their own lives and to help the dreamer accept the message of the dream for itself.

Their way of dealing with captivity nightmares was thus a form of psychodrama, an acting out of the traumatic experience, in the safe shared space of consciously engaged-in ritual. Rather than being primitives, they were far more sophisticated in their self-understanding than the Puritans like Mather were. In fact, it's we, today, still trapped in similar patterns of imagining vast conspiracies against us, who are the real primitives, utterly lacking the sophisticated self-understanding we so desperately need.

In colonial times, the tide of historical forces was at the Puritans' backs, although they could not fully know it at the time, or else, perhaps, they might not have been quite so profoundly driven by their fears. As a result, they could afford to believe all manner of foolish things, and yet they would still survive, and even prosper. But now, this time, that may no longer be the case. We may actually need to understand the world, beyond our own inner world of recycled fears, in order to survive, and perhaps even prosper in it. We need to finally confront those demons as our own, not aspects of a shadowy other whom we can utterly annihilate. They are, rather, aspects of ourselves we need to have the courage to face up to. There is no vast conspiracy of diverse deadly enemies out there—only the endless outward reflection of our own unfaced inner fears.

Publicity hound, coward, liar: Whistleblowers are inevitably demonized by their enemies — Edward Snowden is no exception

Religious kids are no angels: Science suggests they’re more selfish — and sadistic

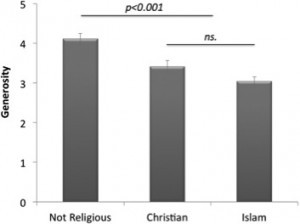

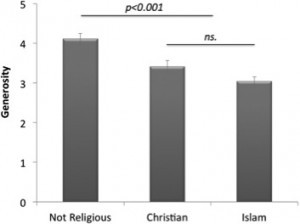

Are kids from more religious families more or less altruistic than their peers from less-religious families? That’s what a high-profile new study from University of Chicago neuroscientist Jean Decety and a global crew of collaborators sought to determine. In the course of the study, published in the journal of Current Biology, the researchers use something called the “children’s dictator game,” a.k.a. stickerpalooza. Here’s how it worked: Step one. Go to an elementary school. Find a child. Place a set of 30 stickers in front of the child. Tell the child to pick her favorite ten. Step two. Introduce a plot twist. Tell the kid that not everyone in school could participate in the sticker bonanza. Fortunately, there is a chance to share: the kid can pick between zero and 10 of her favorite, cream-of-the-crop stickers, and set them aside in an envelope. That envelope will go to another person in the school. Afterward, the kid will walk out with whatever stickers she chose to keep. In order to keep things nice and relaxed, this sharing stage is anonymous. Nobody watches the kid set her stickers aside. She doesn’t know which classmate receives them, and the classmate doesn’t find out who donated them. But, later, the researcher can count the shared stickers, and have some approximation of the child’s moral fiber. In their study, Decety and his colleagues gave the sticker test to 1,170 kids at schools in six cities—Amman, Cape Town, Chicago, Guangzhou, Istanbul, and Toronto. “Altruism was calculated as the number of stickers shared out of 10,” they write. The researchers also gave the kids another test, in which they watched videos of people hurting other people, and then judged (a) how mean the bullies were, and (b) how much punishment the bullies deserved. Then Decety and his collaborators went to the kids’ parents and asked them questions about the religious identity and practices of the family, and about how moral they thought their kids were. Here’s the zinger: according to Decety and his colleagues, kids from more religious households are less altruistic, and more apt to deal out punishment, than kids from non-religious households. Corollary zinger: on the punishment front, Muslim kids are even more vindictive than Christians. “Nonreligious children are more generous,” explained a headline at Science magazine. “It’s not like you have to be highly religious to be a good person,” Decety told Forbes. “Secularity—like having your own laws and rules based on rational thinking, reason rather than holy books—is better for everybody.” Forbes headlined the article “Religion Makes Children More Selfish, Say Scientists.” (Decety tweeted a link to the piece). In the Forbes interview, Decety cautioned that there would be naysayers, at least among the anti-science crowd. “My guess is they’re just going to deny what I did—they don’t want science, they don’t believe in evolution, they don’t want Darwin to be taught in schools.” The Cubit is all for science—and Darwin! In fact, that’s why we feel obligated to point out that Decety’s paper is deaf to interdisciplinary critiques, premised on an obsolete and misleading view of the world, fundamentally unable to acknowledge its own hubristic assumptions, and, consequently, unlikely to produce meaningful insights into reality and the human condition. Making generalizations Sometimes, late at night, drinking in pseudo-seedy college-town hipster dive bars, I’ll start complaining about bad social science, and midway through the rant, friends will adopt kindly, exasperated who-gives-a-shit? expressions. It’s a fair response. But this stuff matters. Western societies have developed specific tools with which to make generalizations about human beings. Some of the more traditional tools here include stereotyping and prejudice. Often, these get ideologized into more potent generalization-generators: racism, anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, sexism, and so on. In many cases, social science—and especially experimental social science—tries to produce generalizations about human beings, too. Sometimes, it seeks to do so about a specific subset of the population (say, Christians or Muslims). I want to be 150% clear here: when researchers seek to find general principles or patterns in human society, that does not make them racist, or anti-Semitic, or Islamophobic, or sexist. It is very possible to seek rules for social interaction without falling into ideological or political traps. At the same time, social scientists run a special kind of risk, because their work does seem, superficially, to share certain goals with the ideological generalizers. Researchers have to be extra-careful to ensure that the biases and preconceptions of the political space don’t bleed into their work. And they have to be sober and realistic about the conclusions they draw from their research. Additionally, it might not hurt to make sure that your methods are something other than totally shitty. For a case study of how this little balancing act might break down, let’s check out the Decety et al.paper. The study is trying to understand certain rules that might govern the relationship between religiosity and prosocial behavior, which is a technical term for stuff you do that benefits other people in your community. Prosocial behaviors range widely, from the dramatic (sacrificing your life for a team) to the mundane (sharing stickers). I’d like to peel apart the methodological issues here with a cool and well-informed eye, except that the methods section of the paper is unusually vague, and Jean Decety isn’t responding to my polite emails. Nor my polite calls. Nor the polite request that I lodged with him through his lab manager, who confirmed that Decety knows that I’m trying to reach him. Frustrated, I asked the editor of Current Biology if he could help me puzzle through some of the gaps in the methods section. He told me to email Decety. Soldiering on through the silence, we can see a few key problem areas with “The Negative Association between Religiousness and Children’s Altruism across the World.” Basically, these problems have to do with the definition of religiousness, the metric for altruism, and the concept ofworld. Let’s take them one by one. Problem 1: “The Negative Association between Religiousness….” Scholars of religion are fond of explaining all the reasons that religion is really, really difficult to define. The more cynical among us might point out that, in a crowded job market, academics distinguish themselves by explaining why everyone else’s categories are wrong, meaning that religion scholars have a strong incentive to expound, at length, about all the reasons that religion is really, really difficult to define. But, look: they have a point. In most of the world, for most of history, cultures had very little notion of a discrete thing called “religion,” as something that you could then choose, reject, or petition forfreedom of. The choice to constellate certain kinds of rituals, stories, propositions and epistemological modes into a single package called “religion” is a fairly recent, European, and Protestant phenomenon. Similarly, the idea that religiousness is separable from the rest of culture, in such a way that you can see it quantifiably motivating certain behaviors, would seem alien and weird to a lot of people, for whom Faith is not so easily distinguished from other strands of culture. In the case of a cross-cultural religiosity study, such as Decety’s paper, this definitional challenge makes the work pretty tough from the start. Religiosity is entangled with all sorts of other cultural markers and experiences. The researchers control for one confounding variable here: socioeconomic status. Number of siblings? The researchers didn’t address that, even though religious engagement can be correlated with family size (thanks to a Reddit commenter for pointing this out). Amount of exposure to other kids outside of school? Ditto. Parents’ education levels? Missing. Heterogeneity of the surrounding community? Also left out. And so on. More slippery, though, is that this kind of works requires some way of measuring religiousness, such that you can get a scale that works the same in mostly-Muslim Amman as it does in mostly-Christian Chicago, and also in Guangzhou, where concepts of ritual and religiousness are wildly different than those held in the Western world. In other words, you have to take this fragile Western construct (religion), put a numerical scale on it, and then apply that scale around the world, as if religion were a solid, universally measurable thing, like the force of gravity or the density of water. Judging by the paper, Decety and his colleagues haven’t even recognized this problem, let alone addressed it. Instead, they just grabbed a handy global-religion-quantifier and went to work. The metric they chose, the Duke University Religiosity Index, or DUREL, is designed for epidemiological studies that take place within a single religious tradition, and for use with Abrahamic religions. In other words, it’s not at all adapted for cross-cultural research that includes East Asia. Problem 2: “…and children’s altruism…” It’s unclear how well something like the sticker test measures the delicate, context-dependent applications of altruism within an individual child’s life. “One potential critique [of the study] is the artificiality of the situation” said Luke Galen, a professor of psychology at Grand Valley State University who reviewed a draft of the paper. But, he added, “that’s true of 90% of the studies in the literature.” In other words, things like the sticker test are comparable to other discipline-approved tools that we have to plumb the dynamics of human kindness. In all fairness, social science is hard. Developing a metric for altruism is tricky work, and you have to start somewhere. In this sense, the sticker test probably isn’t a bad tool. The question is how far you’re willing to generalize about the qualities of billions of people based on its results. Judging by Decety’s comments about the nature of secularity and morality, the answer for some researchers isvery far indeed. As Galen points out, the fact that the researchers did any kind of rigorous altruism test, instead of just asking kids and parents to self-report about their moral feelings and behaviors, sets the Decety study apart from many others in the field. Wisely, Galen adds that the study should be read in the context of a larger set of recent studies finding that religion might not be the magic prosociality-booster-pill that some other generalizers have claimed it to be. These are important caveats to my snark. Problem 3: “…across the World.” There are a few reasons, though, to wonder whether these results can be generalized very far. Does a population of kids from a handful of major urban centers really tell us much about the world as a whole? Additionally, the researchers don’t explain how they recruited the kids. Omitting recruitment data doesn’t invalidate the findings, but it makes it hard to gauge the generalizability of the results, Galen said. Were the kids selected randomly? Did families have to volunteer? It’s not clear. One other, even bigger problem: most of the non-religious kids probably come from China. Not that you would know that from reading the paper. In a strange omission, Decety and his colleagues do not provide any kind of country-by-country breakdown of where the Muslim, Christian, and non-religious kids come from. As a result, when you see a graph like this, which is the linchpin of the paper—

Are kids from more religious families more or less altruistic than their peers from less-religious families? That’s what a high-profile new study from University of Chicago neuroscientist Jean Decety and a global crew of collaborators sought to determine. In the course of the study, published in the journal of Current Biology, the researchers use something called the “children’s dictator game,” a.k.a. stickerpalooza. Here’s how it worked: Step one. Go to an elementary school. Find a child. Place a set of 30 stickers in front of the child. Tell the child to pick her favorite ten. Step two. Introduce a plot twist. Tell the kid that not everyone in school could participate in the sticker bonanza. Fortunately, there is a chance to share: the kid can pick between zero and 10 of her favorite, cream-of-the-crop stickers, and set them aside in an envelope. That envelope will go to another person in the school. Afterward, the kid will walk out with whatever stickers she chose to keep. In order to keep things nice and relaxed, this sharing stage is anonymous. Nobody watches the kid set her stickers aside. She doesn’t know which classmate receives them, and the classmate doesn’t find out who donated them. But, later, the researcher can count the shared stickers, and have some approximation of the child’s moral fiber. In their study, Decety and his colleagues gave the sticker test to 1,170 kids at schools in six cities—Amman, Cape Town, Chicago, Guangzhou, Istanbul, and Toronto. “Altruism was calculated as the number of stickers shared out of 10,” they write. The researchers also gave the kids another test, in which they watched videos of people hurting other people, and then judged (a) how mean the bullies were, and (b) how much punishment the bullies deserved. Then Decety and his collaborators went to the kids’ parents and asked them questions about the religious identity and practices of the family, and about how moral they thought their kids were. Here’s the zinger: according to Decety and his colleagues, kids from more religious households are less altruistic, and more apt to deal out punishment, than kids from non-religious households. Corollary zinger: on the punishment front, Muslim kids are even more vindictive than Christians. “Nonreligious children are more generous,” explained a headline at Science magazine. “It’s not like you have to be highly religious to be a good person,” Decety told Forbes. “Secularity—like having your own laws and rules based on rational thinking, reason rather than holy books—is better for everybody.” Forbes headlined the article “Religion Makes Children More Selfish, Say Scientists.” (Decety tweeted a link to the piece). In the Forbes interview, Decety cautioned that there would be naysayers, at least among the anti-science crowd. “My guess is they’re just going to deny what I did—they don’t want science, they don’t believe in evolution, they don’t want Darwin to be taught in schools.” The Cubit is all for science—and Darwin! In fact, that’s why we feel obligated to point out that Decety’s paper is deaf to interdisciplinary critiques, premised on an obsolete and misleading view of the world, fundamentally unable to acknowledge its own hubristic assumptions, and, consequently, unlikely to produce meaningful insights into reality and the human condition. Making generalizations Sometimes, late at night, drinking in pseudo-seedy college-town hipster dive bars, I’ll start complaining about bad social science, and midway through the rant, friends will adopt kindly, exasperated who-gives-a-shit? expressions. It’s a fair response. But this stuff matters. Western societies have developed specific tools with which to make generalizations about human beings. Some of the more traditional tools here include stereotyping and prejudice. Often, these get ideologized into more potent generalization-generators: racism, anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, sexism, and so on. In many cases, social science—and especially experimental social science—tries to produce generalizations about human beings, too. Sometimes, it seeks to do so about a specific subset of the population (say, Christians or Muslims). I want to be 150% clear here: when researchers seek to find general principles or patterns in human society, that does not make them racist, or anti-Semitic, or Islamophobic, or sexist. It is very possible to seek rules for social interaction without falling into ideological or political traps. At the same time, social scientists run a special kind of risk, because their work does seem, superficially, to share certain goals with the ideological generalizers. Researchers have to be extra-careful to ensure that the biases and preconceptions of the political space don’t bleed into their work. And they have to be sober and realistic about the conclusions they draw from their research. Additionally, it might not hurt to make sure that your methods are something other than totally shitty. For a case study of how this little balancing act might break down, let’s check out the Decety et al.paper. The study is trying to understand certain rules that might govern the relationship between religiosity and prosocial behavior, which is a technical term for stuff you do that benefits other people in your community. Prosocial behaviors range widely, from the dramatic (sacrificing your life for a team) to the mundane (sharing stickers). I’d like to peel apart the methodological issues here with a cool and well-informed eye, except that the methods section of the paper is unusually vague, and Jean Decety isn’t responding to my polite emails. Nor my polite calls. Nor the polite request that I lodged with him through his lab manager, who confirmed that Decety knows that I’m trying to reach him. Frustrated, I asked the editor of Current Biology if he could help me puzzle through some of the gaps in the methods section. He told me to email Decety. Soldiering on through the silence, we can see a few key problem areas with “The Negative Association between Religiousness and Children’s Altruism across the World.” Basically, these problems have to do with the definition of religiousness, the metric for altruism, and the concept ofworld. Let’s take them one by one. Problem 1: “The Negative Association between Religiousness….” Scholars of religion are fond of explaining all the reasons that religion is really, really difficult to define. The more cynical among us might point out that, in a crowded job market, academics distinguish themselves by explaining why everyone else’s categories are wrong, meaning that religion scholars have a strong incentive to expound, at length, about all the reasons that religion is really, really difficult to define. But, look: they have a point. In most of the world, for most of history, cultures had very little notion of a discrete thing called “religion,” as something that you could then choose, reject, or petition forfreedom of. The choice to constellate certain kinds of rituals, stories, propositions and epistemological modes into a single package called “religion” is a fairly recent, European, and Protestant phenomenon. Similarly, the idea that religiousness is separable from the rest of culture, in such a way that you can see it quantifiably motivating certain behaviors, would seem alien and weird to a lot of people, for whom Faith is not so easily distinguished from other strands of culture. In the case of a cross-cultural religiosity study, such as Decety’s paper, this definitional challenge makes the work pretty tough from the start. Religiosity is entangled with all sorts of other cultural markers and experiences. The researchers control for one confounding variable here: socioeconomic status. Number of siblings? The researchers didn’t address that, even though religious engagement can be correlated with family size (thanks to a Reddit commenter for pointing this out). Amount of exposure to other kids outside of school? Ditto. Parents’ education levels? Missing. Heterogeneity of the surrounding community? Also left out. And so on. More slippery, though, is that this kind of works requires some way of measuring religiousness, such that you can get a scale that works the same in mostly-Muslim Amman as it does in mostly-Christian Chicago, and also in Guangzhou, where concepts of ritual and religiousness are wildly different than those held in the Western world. In other words, you have to take this fragile Western construct (religion), put a numerical scale on it, and then apply that scale around the world, as if religion were a solid, universally measurable thing, like the force of gravity or the density of water. Judging by the paper, Decety and his colleagues haven’t even recognized this problem, let alone addressed it. Instead, they just grabbed a handy global-religion-quantifier and went to work. The metric they chose, the Duke University Religiosity Index, or DUREL, is designed for epidemiological studies that take place within a single religious tradition, and for use with Abrahamic religions. In other words, it’s not at all adapted for cross-cultural research that includes East Asia. Problem 2: “…and children’s altruism…” It’s unclear how well something like the sticker test measures the delicate, context-dependent applications of altruism within an individual child’s life. “One potential critique [of the study] is the artificiality of the situation” said Luke Galen, a professor of psychology at Grand Valley State University who reviewed a draft of the paper. But, he added, “that’s true of 90% of the studies in the literature.” In other words, things like the sticker test are comparable to other discipline-approved tools that we have to plumb the dynamics of human kindness. In all fairness, social science is hard. Developing a metric for altruism is tricky work, and you have to start somewhere. In this sense, the sticker test probably isn’t a bad tool. The question is how far you’re willing to generalize about the qualities of billions of people based on its results. Judging by Decety’s comments about the nature of secularity and morality, the answer for some researchers isvery far indeed. As Galen points out, the fact that the researchers did any kind of rigorous altruism test, instead of just asking kids and parents to self-report about their moral feelings and behaviors, sets the Decety study apart from many others in the field. Wisely, Galen adds that the study should be read in the context of a larger set of recent studies finding that religion might not be the magic prosociality-booster-pill that some other generalizers have claimed it to be. These are important caveats to my snark. Problem 3: “…across the World.” There are a few reasons, though, to wonder whether these results can be generalized very far. Does a population of kids from a handful of major urban centers really tell us much about the world as a whole? Additionally, the researchers don’t explain how they recruited the kids. Omitting recruitment data doesn’t invalidate the findings, but it makes it hard to gauge the generalizability of the results, Galen said. Were the kids selected randomly? Did families have to volunteer? It’s not clear. One other, even bigger problem: most of the non-religious kids probably come from China. Not that you would know that from reading the paper. In a strange omission, Decety and his colleagues do not provide any kind of country-by-country breakdown of where the Muslim, Christian, and non-religious kids come from. As a result, when you see a graph like this, which is the linchpin of the paper—

—you can almost imagine that it refers to a robust global sample of non-religious kids, stacked up against their faithier peers, and not a bunch of kids from Guangzhou, getting compared to children from five other cities, all of which lie West of Mecca. How do I know all of this? Educated guesswork. I could be wrong. But here’s how the numbers break down: globally, 323 families in the study identified as non-religious. And 219 kids in the study came from China. It is extremely unlikely that more than a handful of the Chinese families identified themselves as Christian or Muslim, and we know for sure that they mostly avoided identifying as Buddhist, because just 18 families in the whole 1,170 kid dataset did so. Nobody identified as Confucian. Just six families, worldwide, said they were “other.” By elimination, that leaves around 200 Chinese kids for the non-religious side of the ledger, or around 60% of the total non-religious pool. So, how do we know that this study is picking up on something unique to religiosity, instead of the difference between Chinese kids and non-Chinese kids, or Western kids and non-Western kids, or Guangzhou kids and everybody else? Well, you can analyze the stats enough to pick out religiousness as one factor, distinct from country-of-origin, that seems to be driving some of the result. That’s important. But it’s not clear from the numbers provided in the study that non-religious kids, globally, share fewer stickers in a way that’s separable from other ethnic markers. A divergence In the past few decades, there has been a sharp divergence between those who study religion from within sociology and the humanities, and those who approach it from the side of social and evolutionary psychology. The humanists and sociologists have moved toward more and more granular snapshots of religious life, leaving behind the old, sweeping Religion is x, y, and zformulations that defined the good old days, when a dude in an office at Oxford could comfortably sketch out a theory of ritual based on secondhand ethnographies from remote tropical islands. Meanwhile, the social and evolutionary psychologists seem to be flying full-tilt in the direction of more and more grand theories of The Role of Religion in All Humanity. From my semi-neutral post as a journalist who covers both fields, I’d like to suggest that the social and evolutionary psychologists are more full-of-shit than the humanists. The fact that someone like Decety feels comfortable taking his sticker games and making public comments about the fundamental nature of morality and secularity feels slightly surreal. (It’s not just in Forbesinterviews. Here’s the final line of the paper: “More generally, [our findings] call into question whether religion is vital for moral development, supporting the idea that the secularization of moral discourse will not reduce human kindness—in fact, it will do just the opposite.”) The problem is not that Decety and his colleagues’ results aren’t interesting, or even that they’re wrong—for all I know, all the world over, kids who engage more with certain ritual experiences are less kind to their peers. The problem is that, absent robust evidence for his generalizations about the Nature of all Christians and Muslims, it is difficult to tell where Decety’s grand claims emerge from actual evidence, and where they may owe a debt to politicized beliefs about how religion in general, or specific religious traditions (i.e. Islam), motivate people to do bad things.

—you can almost imagine that it refers to a robust global sample of non-religious kids, stacked up against their faithier peers, and not a bunch of kids from Guangzhou, getting compared to children from five other cities, all of which lie West of Mecca. How do I know all of this? Educated guesswork. I could be wrong. But here’s how the numbers break down: globally, 323 families in the study identified as non-religious. And 219 kids in the study came from China. It is extremely unlikely that more than a handful of the Chinese families identified themselves as Christian or Muslim, and we know for sure that they mostly avoided identifying as Buddhist, because just 18 families in the whole 1,170 kid dataset did so. Nobody identified as Confucian. Just six families, worldwide, said they were “other.” By elimination, that leaves around 200 Chinese kids for the non-religious side of the ledger, or around 60% of the total non-religious pool. So, how do we know that this study is picking up on something unique to religiosity, instead of the difference between Chinese kids and non-Chinese kids, or Western kids and non-Western kids, or Guangzhou kids and everybody else? Well, you can analyze the stats enough to pick out religiousness as one factor, distinct from country-of-origin, that seems to be driving some of the result. That’s important. But it’s not clear from the numbers provided in the study that non-religious kids, globally, share fewer stickers in a way that’s separable from other ethnic markers. A divergence In the past few decades, there has been a sharp divergence between those who study religion from within sociology and the humanities, and those who approach it from the side of social and evolutionary psychology. The humanists and sociologists have moved toward more and more granular snapshots of religious life, leaving behind the old, sweeping Religion is x, y, and zformulations that defined the good old days, when a dude in an office at Oxford could comfortably sketch out a theory of ritual based on secondhand ethnographies from remote tropical islands. Meanwhile, the social and evolutionary psychologists seem to be flying full-tilt in the direction of more and more grand theories of The Role of Religion in All Humanity. From my semi-neutral post as a journalist who covers both fields, I’d like to suggest that the social and evolutionary psychologists are more full-of-shit than the humanists. The fact that someone like Decety feels comfortable taking his sticker games and making public comments about the fundamental nature of morality and secularity feels slightly surreal. (It’s not just in Forbesinterviews. Here’s the final line of the paper: “More generally, [our findings] call into question whether religion is vital for moral development, supporting the idea that the secularization of moral discourse will not reduce human kindness—in fact, it will do just the opposite.”) The problem is not that Decety and his colleagues’ results aren’t interesting, or even that they’re wrong—for all I know, all the world over, kids who engage more with certain ritual experiences are less kind to their peers. The problem is that, absent robust evidence for his generalizations about the Nature of all Christians and Muslims, it is difficult to tell where Decety’s grand claims emerge from actual evidence, and where they may owe a debt to politicized beliefs about how religion in general, or specific religious traditions (i.e. Islam), motivate people to do bad things.

Are kids from more religious families more or less altruistic than their peers from less-religious families? That’s what a high-profile new study from University of Chicago neuroscientist Jean Decety and a global crew of collaborators sought to determine. In the course of the study, published in the journal of Current Biology, the researchers use something called the “children’s dictator game,” a.k.a. stickerpalooza. Here’s how it worked: Step one. Go to an elementary school. Find a child. Place a set of 30 stickers in front of the child. Tell the child to pick her favorite ten. Step two. Introduce a plot twist. Tell the kid that not everyone in school could participate in the sticker bonanza. Fortunately, there is a chance to share: the kid can pick between zero and 10 of her favorite, cream-of-the-crop stickers, and set them aside in an envelope. That envelope will go to another person in the school. Afterward, the kid will walk out with whatever stickers she chose to keep. In order to keep things nice and relaxed, this sharing stage is anonymous. Nobody watches the kid set her stickers aside. She doesn’t know which classmate receives them, and the classmate doesn’t find out who donated them. But, later, the researcher can count the shared stickers, and have some approximation of the child’s moral fiber. In their study, Decety and his colleagues gave the sticker test to 1,170 kids at schools in six cities—Amman, Cape Town, Chicago, Guangzhou, Istanbul, and Toronto. “Altruism was calculated as the number of stickers shared out of 10,” they write. The researchers also gave the kids another test, in which they watched videos of people hurting other people, and then judged (a) how mean the bullies were, and (b) how much punishment the bullies deserved. Then Decety and his collaborators went to the kids’ parents and asked them questions about the religious identity and practices of the family, and about how moral they thought their kids were. Here’s the zinger: according to Decety and his colleagues, kids from more religious households are less altruistic, and more apt to deal out punishment, than kids from non-religious households. Corollary zinger: on the punishment front, Muslim kids are even more vindictive than Christians. “Nonreligious children are more generous,” explained a headline at Science magazine. “It’s not like you have to be highly religious to be a good person,” Decety told Forbes. “Secularity—like having your own laws and rules based on rational thinking, reason rather than holy books—is better for everybody.” Forbes headlined the article “Religion Makes Children More Selfish, Say Scientists.” (Decety tweeted a link to the piece). In the Forbes interview, Decety cautioned that there would be naysayers, at least among the anti-science crowd. “My guess is they’re just going to deny what I did—they don’t want science, they don’t believe in evolution, they don’t want Darwin to be taught in schools.” The Cubit is all for science—and Darwin! In fact, that’s why we feel obligated to point out that Decety’s paper is deaf to interdisciplinary critiques, premised on an obsolete and misleading view of the world, fundamentally unable to acknowledge its own hubristic assumptions, and, consequently, unlikely to produce meaningful insights into reality and the human condition. Making generalizations Sometimes, late at night, drinking in pseudo-seedy college-town hipster dive bars, I’ll start complaining about bad social science, and midway through the rant, friends will adopt kindly, exasperated who-gives-a-shit? expressions. It’s a fair response. But this stuff matters. Western societies have developed specific tools with which to make generalizations about human beings. Some of the more traditional tools here include stereotyping and prejudice. Often, these get ideologized into more potent generalization-generators: racism, anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, sexism, and so on. In many cases, social science—and especially experimental social science—tries to produce generalizations about human beings, too. Sometimes, it seeks to do so about a specific subset of the population (say, Christians or Muslims). I want to be 150% clear here: when researchers seek to find general principles or patterns in human society, that does not make them racist, or anti-Semitic, or Islamophobic, or sexist. It is very possible to seek rules for social interaction without falling into ideological or political traps. At the same time, social scientists run a special kind of risk, because their work does seem, superficially, to share certain goals with the ideological generalizers. Researchers have to be extra-careful to ensure that the biases and preconceptions of the political space don’t bleed into their work. And they have to be sober and realistic about the conclusions they draw from their research. Additionally, it might not hurt to make sure that your methods are something other than totally shitty. For a case study of how this little balancing act might break down, let’s check out the Decety et al.paper. The study is trying to understand certain rules that might govern the relationship between religiosity and prosocial behavior, which is a technical term for stuff you do that benefits other people in your community. Prosocial behaviors range widely, from the dramatic (sacrificing your life for a team) to the mundane (sharing stickers). I’d like to peel apart the methodological issues here with a cool and well-informed eye, except that the methods section of the paper is unusually vague, and Jean Decety isn’t responding to my polite emails. Nor my polite calls. Nor the polite request that I lodged with him through his lab manager, who confirmed that Decety knows that I’m trying to reach him. Frustrated, I asked the editor of Current Biology if he could help me puzzle through some of the gaps in the methods section. He told me to email Decety. Soldiering on through the silence, we can see a few key problem areas with “The Negative Association between Religiousness and Children’s Altruism across the World.” Basically, these problems have to do with the definition of religiousness, the metric for altruism, and the concept ofworld. Let’s take them one by one. Problem 1: “The Negative Association between Religiousness….” Scholars of religion are fond of explaining all the reasons that religion is really, really difficult to define. The more cynical among us might point out that, in a crowded job market, academics distinguish themselves by explaining why everyone else’s categories are wrong, meaning that religion scholars have a strong incentive to expound, at length, about all the reasons that religion is really, really difficult to define. But, look: they have a point. In most of the world, for most of history, cultures had very little notion of a discrete thing called “religion,” as something that you could then choose, reject, or petition forfreedom of. The choice to constellate certain kinds of rituals, stories, propositions and epistemological modes into a single package called “religion” is a fairly recent, European, and Protestant phenomenon. Similarly, the idea that religiousness is separable from the rest of culture, in such a way that you can see it quantifiably motivating certain behaviors, would seem alien and weird to a lot of people, for whom Faith is not so easily distinguished from other strands of culture. In the case of a cross-cultural religiosity study, such as Decety’s paper, this definitional challenge makes the work pretty tough from the start. Religiosity is entangled with all sorts of other cultural markers and experiences. The researchers control for one confounding variable here: socioeconomic status. Number of siblings? The researchers didn’t address that, even though religious engagement can be correlated with family size (thanks to a Reddit commenter for pointing this out). Amount of exposure to other kids outside of school? Ditto. Parents’ education levels? Missing. Heterogeneity of the surrounding community? Also left out. And so on. More slippery, though, is that this kind of works requires some way of measuring religiousness, such that you can get a scale that works the same in mostly-Muslim Amman as it does in mostly-Christian Chicago, and also in Guangzhou, where concepts of ritual and religiousness are wildly different than those held in the Western world. In other words, you have to take this fragile Western construct (religion), put a numerical scale on it, and then apply that scale around the world, as if religion were a solid, universally measurable thing, like the force of gravity or the density of water. Judging by the paper, Decety and his colleagues haven’t even recognized this problem, let alone addressed it. Instead, they just grabbed a handy global-religion-quantifier and went to work. The metric they chose, the Duke University Religiosity Index, or DUREL, is designed for epidemiological studies that take place within a single religious tradition, and for use with Abrahamic religions. In other words, it’s not at all adapted for cross-cultural research that includes East Asia. Problem 2: “…and children’s altruism…” It’s unclear how well something like the sticker test measures the delicate, context-dependent applications of altruism within an individual child’s life. “One potential critique [of the study] is the artificiality of the situation” said Luke Galen, a professor of psychology at Grand Valley State University who reviewed a draft of the paper. But, he added, “that’s true of 90% of the studies in the literature.” In other words, things like the sticker test are comparable to other discipline-approved tools that we have to plumb the dynamics of human kindness. In all fairness, social science is hard. Developing a metric for altruism is tricky work, and you have to start somewhere. In this sense, the sticker test probably isn’t a bad tool. The question is how far you’re willing to generalize about the qualities of billions of people based on its results. Judging by Decety’s comments about the nature of secularity and morality, the answer for some researchers isvery far indeed. As Galen points out, the fact that the researchers did any kind of rigorous altruism test, instead of just asking kids and parents to self-report about their moral feelings and behaviors, sets the Decety study apart from many others in the field. Wisely, Galen adds that the study should be read in the context of a larger set of recent studies finding that religion might not be the magic prosociality-booster-pill that some other generalizers have claimed it to be. These are important caveats to my snark. Problem 3: “…across the World.” There are a few reasons, though, to wonder whether these results can be generalized very far. Does a population of kids from a handful of major urban centers really tell us much about the world as a whole? Additionally, the researchers don’t explain how they recruited the kids. Omitting recruitment data doesn’t invalidate the findings, but it makes it hard to gauge the generalizability of the results, Galen said. Were the kids selected randomly? Did families have to volunteer? It’s not clear. One other, even bigger problem: most of the non-religious kids probably come from China. Not that you would know that from reading the paper. In a strange omission, Decety and his colleagues do not provide any kind of country-by-country breakdown of where the Muslim, Christian, and non-religious kids come from. As a result, when you see a graph like this, which is the linchpin of the paper—

Are kids from more religious families more or less altruistic than their peers from less-religious families? That’s what a high-profile new study from University of Chicago neuroscientist Jean Decety and a global crew of collaborators sought to determine. In the course of the study, published in the journal of Current Biology, the researchers use something called the “children’s dictator game,” a.k.a. stickerpalooza. Here’s how it worked: Step one. Go to an elementary school. Find a child. Place a set of 30 stickers in front of the child. Tell the child to pick her favorite ten. Step two. Introduce a plot twist. Tell the kid that not everyone in school could participate in the sticker bonanza. Fortunately, there is a chance to share: the kid can pick between zero and 10 of her favorite, cream-of-the-crop stickers, and set them aside in an envelope. That envelope will go to another person in the school. Afterward, the kid will walk out with whatever stickers she chose to keep. In order to keep things nice and relaxed, this sharing stage is anonymous. Nobody watches the kid set her stickers aside. She doesn’t know which classmate receives them, and the classmate doesn’t find out who donated them. But, later, the researcher can count the shared stickers, and have some approximation of the child’s moral fiber. In their study, Decety and his colleagues gave the sticker test to 1,170 kids at schools in six cities—Amman, Cape Town, Chicago, Guangzhou, Istanbul, and Toronto. “Altruism was calculated as the number of stickers shared out of 10,” they write. The researchers also gave the kids another test, in which they watched videos of people hurting other people, and then judged (a) how mean the bullies were, and (b) how much punishment the bullies deserved. Then Decety and his collaborators went to the kids’ parents and asked them questions about the religious identity and practices of the family, and about how moral they thought their kids were. Here’s the zinger: according to Decety and his colleagues, kids from more religious households are less altruistic, and more apt to deal out punishment, than kids from non-religious households. Corollary zinger: on the punishment front, Muslim kids are even more vindictive than Christians. “Nonreligious children are more generous,” explained a headline at Science magazine. “It’s not like you have to be highly religious to be a good person,” Decety told Forbes. “Secularity—like having your own laws and rules based on rational thinking, reason rather than holy books—is better for everybody.” Forbes headlined the article “Religion Makes Children More Selfish, Say Scientists.” (Decety tweeted a link to the piece). In the Forbes interview, Decety cautioned that there would be naysayers, at least among the anti-science crowd. “My guess is they’re just going to deny what I did—they don’t want science, they don’t believe in evolution, they don’t want Darwin to be taught in schools.” The Cubit is all for science—and Darwin! In fact, that’s why we feel obligated to point out that Decety’s paper is deaf to interdisciplinary critiques, premised on an obsolete and misleading view of the world, fundamentally unable to acknowledge its own hubristic assumptions, and, consequently, unlikely to produce meaningful insights into reality and the human condition. Making generalizations Sometimes, late at night, drinking in pseudo-seedy college-town hipster dive bars, I’ll start complaining about bad social science, and midway through the rant, friends will adopt kindly, exasperated who-gives-a-shit? expressions. It’s a fair response. But this stuff matters. Western societies have developed specific tools with which to make generalizations about human beings. Some of the more traditional tools here include stereotyping and prejudice. Often, these get ideologized into more potent generalization-generators: racism, anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, sexism, and so on. In many cases, social science—and especially experimental social science—tries to produce generalizations about human beings, too. Sometimes, it seeks to do so about a specific subset of the population (say, Christians or Muslims). I want to be 150% clear here: when researchers seek to find general principles or patterns in human society, that does not make them racist, or anti-Semitic, or Islamophobic, or sexist. It is very possible to seek rules for social interaction without falling into ideological or political traps. At the same time, social scientists run a special kind of risk, because their work does seem, superficially, to share certain goals with the ideological generalizers. Researchers have to be extra-careful to ensure that the biases and preconceptions of the political space don’t bleed into their work. And they have to be sober and realistic about the conclusions they draw from their research. Additionally, it might not hurt to make sure that your methods are something other than totally shitty. For a case study of how this little balancing act might break down, let’s check out the Decety et al.paper. The study is trying to understand certain rules that might govern the relationship between religiosity and prosocial behavior, which is a technical term for stuff you do that benefits other people in your community. Prosocial behaviors range widely, from the dramatic (sacrificing your life for a team) to the mundane (sharing stickers). I’d like to peel apart the methodological issues here with a cool and well-informed eye, except that the methods section of the paper is unusually vague, and Jean Decety isn’t responding to my polite emails. Nor my polite calls. Nor the polite request that I lodged with him through his lab manager, who confirmed that Decety knows that I’m trying to reach him. Frustrated, I asked the editor of Current Biology if he could help me puzzle through some of the gaps in the methods section. He told me to email Decety. Soldiering on through the silence, we can see a few key problem areas with “The Negative Association between Religiousness and Children’s Altruism across the World.” Basically, these problems have to do with the definition of religiousness, the metric for altruism, and the concept ofworld. Let’s take them one by one. Problem 1: “The Negative Association between Religiousness….” Scholars of religion are fond of explaining all the reasons that religion is really, really difficult to define. The more cynical among us might point out that, in a crowded job market, academics distinguish themselves by explaining why everyone else’s categories are wrong, meaning that religion scholars have a strong incentive to expound, at length, about all the reasons that religion is really, really difficult to define. But, look: they have a point. In most of the world, for most of history, cultures had very little notion of a discrete thing called “religion,” as something that you could then choose, reject, or petition forfreedom of. The choice to constellate certain kinds of rituals, stories, propositions and epistemological modes into a single package called “religion” is a fairly recent, European, and Protestant phenomenon. Similarly, the idea that religiousness is separable from the rest of culture, in such a way that you can see it quantifiably motivating certain behaviors, would seem alien and weird to a lot of people, for whom Faith is not so easily distinguished from other strands of culture. In the case of a cross-cultural religiosity study, such as Decety’s paper, this definitional challenge makes the work pretty tough from the start. Religiosity is entangled with all sorts of other cultural markers and experiences. The researchers control for one confounding variable here: socioeconomic status. Number of siblings? The researchers didn’t address that, even though religious engagement can be correlated with family size (thanks to a Reddit commenter for pointing this out). Amount of exposure to other kids outside of school? Ditto. Parents’ education levels? Missing. Heterogeneity of the surrounding community? Also left out. And so on. More slippery, though, is that this kind of works requires some way of measuring religiousness, such that you can get a scale that works the same in mostly-Muslim Amman as it does in mostly-Christian Chicago, and also in Guangzhou, where concepts of ritual and religiousness are wildly different than those held in the Western world. In other words, you have to take this fragile Western construct (religion), put a numerical scale on it, and then apply that scale around the world, as if religion were a solid, universally measurable thing, like the force of gravity or the density of water. Judging by the paper, Decety and his colleagues haven’t even recognized this problem, let alone addressed it. Instead, they just grabbed a handy global-religion-quantifier and went to work. The metric they chose, the Duke University Religiosity Index, or DUREL, is designed for epidemiological studies that take place within a single religious tradition, and for use with Abrahamic religions. In other words, it’s not at all adapted for cross-cultural research that includes East Asia. Problem 2: “…and children’s altruism…” It’s unclear how well something like the sticker test measures the delicate, context-dependent applications of altruism within an individual child’s life. “One potential critique [of the study] is the artificiality of the situation” said Luke Galen, a professor of psychology at Grand Valley State University who reviewed a draft of the paper. But, he added, “that’s true of 90% of the studies in the literature.” In other words, things like the sticker test are comparable to other discipline-approved tools that we have to plumb the dynamics of human kindness. In all fairness, social science is hard. Developing a metric for altruism is tricky work, and you have to start somewhere. In this sense, the sticker test probably isn’t a bad tool. The question is how far you’re willing to generalize about the qualities of billions of people based on its results. Judging by Decety’s comments about the nature of secularity and morality, the answer for some researchers isvery far indeed. As Galen points out, the fact that the researchers did any kind of rigorous altruism test, instead of just asking kids and parents to self-report about their moral feelings and behaviors, sets the Decety study apart from many others in the field. Wisely, Galen adds that the study should be read in the context of a larger set of recent studies finding that religion might not be the magic prosociality-booster-pill that some other generalizers have claimed it to be. These are important caveats to my snark. Problem 3: “…across the World.” There are a few reasons, though, to wonder whether these results can be generalized very far. Does a population of kids from a handful of major urban centers really tell us much about the world as a whole? Additionally, the researchers don’t explain how they recruited the kids. Omitting recruitment data doesn’t invalidate the findings, but it makes it hard to gauge the generalizability of the results, Galen said. Were the kids selected randomly? Did families have to volunteer? It’s not clear. One other, even bigger problem: most of the non-religious kids probably come from China. Not that you would know that from reading the paper. In a strange omission, Decety and his colleagues do not provide any kind of country-by-country breakdown of where the Muslim, Christian, and non-religious kids come from. As a result, when you see a graph like this, which is the linchpin of the paper—

—you can almost imagine that it refers to a robust global sample of non-religious kids, stacked up against their faithier peers, and not a bunch of kids from Guangzhou, getting compared to children from five other cities, all of which lie West of Mecca. How do I know all of this? Educated guesswork. I could be wrong. But here’s how the numbers break down: globally, 323 families in the study identified as non-religious. And 219 kids in the study came from China. It is extremely unlikely that more than a handful of the Chinese families identified themselves as Christian or Muslim, and we know for sure that they mostly avoided identifying as Buddhist, because just 18 families in the whole 1,170 kid dataset did so. Nobody identified as Confucian. Just six families, worldwide, said they were “other.” By elimination, that leaves around 200 Chinese kids for the non-religious side of the ledger, or around 60% of the total non-religious pool. So, how do we know that this study is picking up on something unique to religiosity, instead of the difference between Chinese kids and non-Chinese kids, or Western kids and non-Western kids, or Guangzhou kids and everybody else? Well, you can analyze the stats enough to pick out religiousness as one factor, distinct from country-of-origin, that seems to be driving some of the result. That’s important. But it’s not clear from the numbers provided in the study that non-religious kids, globally, share fewer stickers in a way that’s separable from other ethnic markers. A divergence In the past few decades, there has been a sharp divergence between those who study religion from within sociology and the humanities, and those who approach it from the side of social and evolutionary psychology. The humanists and sociologists have moved toward more and more granular snapshots of religious life, leaving behind the old, sweeping Religion is x, y, and zformulations that defined the good old days, when a dude in an office at Oxford could comfortably sketch out a theory of ritual based on secondhand ethnographies from remote tropical islands. Meanwhile, the social and evolutionary psychologists seem to be flying full-tilt in the direction of more and more grand theories of The Role of Religion in All Humanity. From my semi-neutral post as a journalist who covers both fields, I’d like to suggest that the social and evolutionary psychologists are more full-of-shit than the humanists. The fact that someone like Decety feels comfortable taking his sticker games and making public comments about the fundamental nature of morality and secularity feels slightly surreal. (It’s not just in Forbesinterviews. Here’s the final line of the paper: “More generally, [our findings] call into question whether religion is vital for moral development, supporting the idea that the secularization of moral discourse will not reduce human kindness—in fact, it will do just the opposite.”) The problem is not that Decety and his colleagues’ results aren’t interesting, or even that they’re wrong—for all I know, all the world over, kids who engage more with certain ritual experiences are less kind to their peers. The problem is that, absent robust evidence for his generalizations about the Nature of all Christians and Muslims, it is difficult to tell where Decety’s grand claims emerge from actual evidence, and where they may owe a debt to politicized beliefs about how religion in general, or specific religious traditions (i.e. Islam), motivate people to do bad things.

—you can almost imagine that it refers to a robust global sample of non-religious kids, stacked up against their faithier peers, and not a bunch of kids from Guangzhou, getting compared to children from five other cities, all of which lie West of Mecca. How do I know all of this? Educated guesswork. I could be wrong. But here’s how the numbers break down: globally, 323 families in the study identified as non-religious. And 219 kids in the study came from China. It is extremely unlikely that more than a handful of the Chinese families identified themselves as Christian or Muslim, and we know for sure that they mostly avoided identifying as Buddhist, because just 18 families in the whole 1,170 kid dataset did so. Nobody identified as Confucian. Just six families, worldwide, said they were “other.” By elimination, that leaves around 200 Chinese kids for the non-religious side of the ledger, or around 60% of the total non-religious pool. So, how do we know that this study is picking up on something unique to religiosity, instead of the difference between Chinese kids and non-Chinese kids, or Western kids and non-Western kids, or Guangzhou kids and everybody else? Well, you can analyze the stats enough to pick out religiousness as one factor, distinct from country-of-origin, that seems to be driving some of the result. That’s important. But it’s not clear from the numbers provided in the study that non-religious kids, globally, share fewer stickers in a way that’s separable from other ethnic markers. A divergence In the past few decades, there has been a sharp divergence between those who study religion from within sociology and the humanities, and those who approach it from the side of social and evolutionary psychology. The humanists and sociologists have moved toward more and more granular snapshots of religious life, leaving behind the old, sweeping Religion is x, y, and zformulations that defined the good old days, when a dude in an office at Oxford could comfortably sketch out a theory of ritual based on secondhand ethnographies from remote tropical islands. Meanwhile, the social and evolutionary psychologists seem to be flying full-tilt in the direction of more and more grand theories of The Role of Religion in All Humanity. From my semi-neutral post as a journalist who covers both fields, I’d like to suggest that the social and evolutionary psychologists are more full-of-shit than the humanists. The fact that someone like Decety feels comfortable taking his sticker games and making public comments about the fundamental nature of morality and secularity feels slightly surreal. (It’s not just in Forbesinterviews. Here’s the final line of the paper: “More generally, [our findings] call into question whether religion is vital for moral development, supporting the idea that the secularization of moral discourse will not reduce human kindness—in fact, it will do just the opposite.”) The problem is not that Decety and his colleagues’ results aren’t interesting, or even that they’re wrong—for all I know, all the world over, kids who engage more with certain ritual experiences are less kind to their peers. The problem is that, absent robust evidence for his generalizations about the Nature of all Christians and Muslims, it is difficult to tell where Decety’s grand claims emerge from actual evidence, and where they may owe a debt to politicized beliefs about how religion in general, or specific religious traditions (i.e. Islam), motivate people to do bad things.

Donald Trump’s war on political correctness is just an excuse to spew his nonstop hate speech