Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 923

December 14, 2015

“Star Trek Beyond” looks like a corny, frantic mess: This is supposed to distract us from “Star Wars” mania?

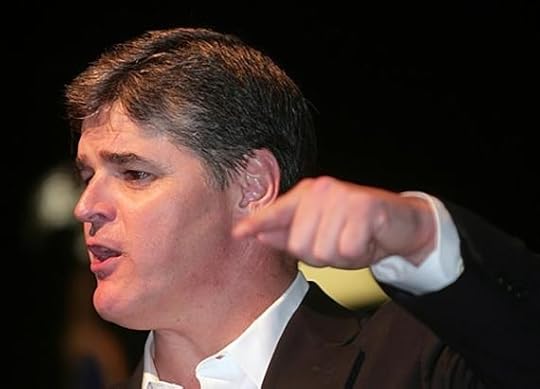

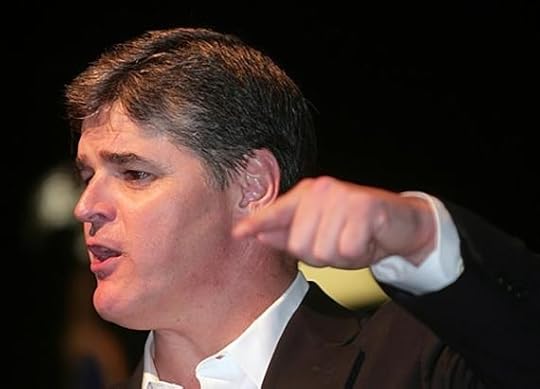

The most disturbing revelations from International Business Times’ new Sean Hannity profile

In a profile for International Business Times, Brendan James sketched a portrait of Sean Hannity decidedly at odds with his combative public persona, and yet somehow just as hypocritical. No matter how heated the conversations are on-set, for example, "I was friends with Alan Colmes. I’m friends with Geraldo [Rivera]. Tamara Holder [a liberal Fox contributor] is a friend of mine. I think they’re wrong, and when we’re debating, we’re debating." He spoke candidly about losing his time slot to Megyn Kelly, claiming that it "was the best thing that ever happened. I was lucky because I was able to get some more flexibility with my schedule" -- a "flexibility" that includes a studio Fox built for him near his home in Long Island. He's clearly not on the ropes with the channel that made him a star, but he's also no longer its golden boy. While Kelly is praised for asking questions tough questions, both in the GOP debates and when they appear on "The Kelly File," Hannity remains committed to lobbing softballs at establishment Republicans. As one GOP operative put it, "[i]f you’re a Republican and you wanna talk to the conservative base, you go on his show." "He wants to be able to get the guests he wants, when he wants them," the operative said. "He wants to have exclusives." Hannity said as much to James, telling him that "I am a conservative, but I consider myself a talk show host. If you ask me, am I a journalist? No. Advocacy journalist, you could say that, but I consider myself a talk show host. And I wear many hats. Sometimes I do straight interviews. Sometimes I do debate. Sometimes I just give monologues on radio that go on for an hour. Y’know, it’s all-encompassing under that banner, meaning a talk show host." He is also an online entrepreneur, who established his "Hannidate" dating service for forlorn conservatives in 2006. While that site has since gone under, Hannity told James that he was willing to resurrect it for the Tinder generatoin. As for how successful it was, he claimed that "many people got married," though he admitted he didn't "know the whole number." Making self-important claims without "know[ing] the whole number" is, in fact, Hannity's modus operandi. He said that on his speaking and book tours, he often pressures couples into getting married. "I’m like, ‘How long you been dating?’ ... ‘OK, why haven’t you asked her?’ And I put him under the gun. Then I say, ‘why don’t you do it now?'" "'Don’t you think he should do it now?’" he asks the crowd, which according to him, "gets into it. I have a success rate of about 90 percent." When James asked how he know that, Hannity said, "I don't know, but it doesn't matter." Unfortunately, he plays similarly fast-and-loose with the facts on "Hannity," frequently citing "a Washington Post poll [that shows] sixty percent of Republicans feel betrayed by Washington Republicans." When James contacted Fox News and requested a link for that poll, James noted parenthically, "[i]t turned out to be an in-house Fox News poll."

In a profile for International Business Times, Brendan James sketched a portrait of Sean Hannity decidedly at odds with his combative public persona, and yet somehow just as hypocritical. No matter how heated the conversations are on-set, for example, "I was friends with Alan Colmes. I’m friends with Geraldo [Rivera]. Tamara Holder [a liberal Fox contributor] is a friend of mine. I think they’re wrong, and when we’re debating, we’re debating." He spoke candidly about losing his time slot to Megyn Kelly, claiming that it "was the best thing that ever happened. I was lucky because I was able to get some more flexibility with my schedule" -- a "flexibility" that includes a studio Fox built for him near his home in Long Island. He's clearly not on the ropes with the channel that made him a star, but he's also no longer its golden boy. While Kelly is praised for asking questions tough questions, both in the GOP debates and when they appear on "The Kelly File," Hannity remains committed to lobbing softballs at establishment Republicans. As one GOP operative put it, "[i]f you’re a Republican and you wanna talk to the conservative base, you go on his show." "He wants to be able to get the guests he wants, when he wants them," the operative said. "He wants to have exclusives." Hannity said as much to James, telling him that "I am a conservative, but I consider myself a talk show host. If you ask me, am I a journalist? No. Advocacy journalist, you could say that, but I consider myself a talk show host. And I wear many hats. Sometimes I do straight interviews. Sometimes I do debate. Sometimes I just give monologues on radio that go on for an hour. Y’know, it’s all-encompassing under that banner, meaning a talk show host." He is also an online entrepreneur, who established his "Hannidate" dating service for forlorn conservatives in 2006. While that site has since gone under, Hannity told James that he was willing to resurrect it for the Tinder generatoin. As for how successful it was, he claimed that "many people got married," though he admitted he didn't "know the whole number." Making self-important claims without "know[ing] the whole number" is, in fact, Hannity's modus operandi. He said that on his speaking and book tours, he often pressures couples into getting married. "I’m like, ‘How long you been dating?’ ... ‘OK, why haven’t you asked her?’ And I put him under the gun. Then I say, ‘why don’t you do it now?'" "'Don’t you think he should do it now?’" he asks the crowd, which according to him, "gets into it. I have a success rate of about 90 percent." When James asked how he know that, Hannity said, "I don't know, but it doesn't matter." Unfortunately, he plays similarly fast-and-loose with the facts on "Hannity," frequently citing "a Washington Post poll [that shows] sixty percent of Republicans feel betrayed by Washington Republicans." When James contacted Fox News and requested a link for that poll, James noted parenthically, "[i]t turned out to be an in-house Fox News poll."

The masters of the GOP universe: How Trump & Cruz have seized the Republican primary by the throat

"You look like the way he's dealt with the Senate, where he goes in there like -- frankly like a little bit of a maniac. You're never going to get things done that way. You can't walk into the Senate and scream and call people liars and not be able to cajole and get along with people. He'll never be able to get anything done, and that's the problem with Ted."It's unnecessary at this point to even point out how ridiculous that sounds coming from Donald Trump, the man who has insulted literally millions of his fellow Americans and most of the world, as well as the entire Republican leadership. But that's him. He's the only presidential candidate in history who actually believes he is the Green Lantern, and will, therefore, be able to rule not by fiat, but by the sheer force of his supernatural abilities to "get things done." All of this comes on the heels of polling that show a big Cruz surge, not just in Iowa, where he's overtaken Trump by a "yuuuge" margin but nationally as well. Cruz is no longer one of the fringe guys. He's for real. Some of us predicted this a while back -- he is a smart politician and he's been positioning himself to take the anti-establishment vote from one or both of the early frontrunners from the beginning. Carson lost altitude when it became obvious that his experience as a neurosurgeon did not prepare him for the rough and tumble world of presidential politics and Cruz was there to catch his followers as they fell. Now he and The Donald are fighting it out for the 50 percent of the party that thinks the biggest problem for the GOP is that it just isn't crazy enough. So Cruz tweeted a rather sweet and gentle response to Trump's taunts, indicating that he is not going to take the bait, but it's pretty clear that Trump is going to go into this week's debate loaded for bear. He does not like being in second place. Meanwhile, the putative "establishment frontrunner," Marco Rubio, whose polling remains mired in the teens at best, made an appearance on "Meet The Press" and demonstrated why that is. When asked about Trump's proposal to ban Muslims from entering the country, instead of explaining that it's both immoral and counterproductive, he chose to emulate a bucket of lukewarm water and said:

"Obviously I don’t agree with everything he says … but we can’t ignore that’s touched on some issues that people are concerned about."If he's trying to make Jeb Bush look tough by comparison, that's a good way to do it. (Indeed, one might assume at this point that any candidate on the so-called establishment track should be showing they are willing to do battle with Trump. If there's one thing that cuts across all the GOP lines, it's a deep and abiding yearning for a manly man to be a man and man-up. If you can't stand up to Trump, how are you going to stand up to all those nannies and busboys lining up at the border to destroy our way of life? How will you be able to assuage the fears of the millions of armed Republicans who eagerly face the dangerous risk of 30,000 gun deaths a year but are cowering in their boots over the prospect of being shot by a Muslim? These are the challenges any establishment Republican has to face in this election and Rubio simply isn't getting the job done. Instead, he seems to be trying to compete on the wingnut track for some reason. Last week he went on the Christian Broadcasting Network and said that he would dispose of all of President Obama's executive orders pertaining to non-discrimination against gay people and work to reverse marriage equality. Chuck Todd pressed him to explain how he would do this asking if he would endorse a constitutional amendment:

MARCO RUBIO: As I’ve said, that would be conceding that the current Constitution is somehow wrong and needs to be fixed.I don’t think the current Constitution gives the federal government the power to regulate marriage. That belongs at the state and local level. And that’s why if you want to change the definition of marriage, which is what this argument is about. It’s not about discrimination. It is about the definition of a very specific, traditional, and age-old institution. If you want to change it, you have a right to petition your state legislature and your elected representatives to do it. What is wrong is that the Supreme Court has found this hidden constitutional right that 200 years of jurisprudence had not discovered and basically overturn the will of voters in Florida where over 60% passed a constitutional amendment that defined marriage in the state constitution as the union of one man and one woman. CHUCK TODD: So are you accepting the idea of same sex marriage in perpetuity? MARCO RUBIO: It is the current law. I don’t believe any case law is settled law. Any future Supreme Court can change it. And ultimately, I will appoint Supreme Court justices that will interpret the Constitution as originally constructed.That's a pretty telling statement. It's true that the Supreme Court does reverse itself sometimes, but this is considered a rare thing that requires a great deal of deliberation. He makes it sound as if stare decisis, the legal principle that says future courts will generally treat decisions of their predecessors as "settled law" unless something very substantial has changed in society, is not something he respects. That has not traditionally been the "establishment" line what with their alleged respect for tradition and all that rot. But then Rubio doesn't seem to know that. Perhaps Rubio thinks the social conservatives will all come his way if he waves his hand at gay marriage and takes the position that all abortion should be banned in all circumstances unless the life of the mother hangs in the balance (a position that used to only be held by the most zealous of anti-abortion activists). But if he thinks he can out-Christian Ted Cruz, he has another thing coming. Cruz is the real thing down to his bones. Rubio doesn't stand a chance with that crowd unless all the others drop out, including Cruz and Trump. Perhaps the most interesting news about Rubio didn't come from either his campaign or any other Republican. Politico reported that John Podesta, Hillary Clinton's campaign chairman, said that he believed Ted Cruz was the likeliest GOP nominee, followed by Trump and then Rubio. This sentiment was echoed by Clinton supporter David Brock who said something similar. He thinks Cruz is going to win the nomination:

He’s where the id of the conservative base is, I believe strongly. He’s got a lot of money, he’s a big super PAC, he’s also got low-dollar donors. He’s playing a very long game organizationally on the ground,” Brock said. “He’s going to win Iowa, I believe, maybe not New Hampshire, but then South Carolina,” Brock said, adding that the party rules that allow for winner-take-all primaries come March will ensure a Cruz victory. Brock said he doesn't dismiss what he characterized as an outside chance that Donald Trump could win his party’s nomination — “You never discount a demagogue” — but said he is not prepared to pour resources into planning for the rise of Sen. Marco Rubio. “I just don’t see it,” he said of the young Florida senator. “He has some critical weaknesses, his absenteeism, weird listlessness on the campaign trail, all the mess with his personal finances — there’s a lot. He hasn’t been vetted.”Matthew Yglesias at Vox was confused by this and laid out a number of reasons why he thinks someone like Brock would say such a thing, ranging from a straightforward belief that Rubio is simply too weak to win to the rumors about some dirt on Rubio they know they're going to unleash that will knock him out of the race. (Maybe it's even some kind of ten dimensional chess move that Brock's playing to mess with Rubio's head.) But the most logical answer is really the simplest: Rubio is a terrible candidate. If you couldn't tell by just watching him, this article by Yglesias's colleague Andrew Prokop fills in the blanks:

Unlike most recent presidential nomination winners, who have invested serious time and effort into campaigning and building organizations in at least one of either Iowa or New Hampshire, Rubio has taken a positively relaxed approach to both. He doesn't show up very often, doesn't do much campaigning when he is around, and doesn't seem to be building very impressive field operations. And it's raising eyebrows. James Pindell of the Boston Globe wrote last week that Rubio's New Hampshire surge was "riddled with doubts," and that GOP insiders are bemoaning his "lack of staff" and "activity." National Review's Tim Alberta and Eliana Johnson reported Wednesday that Rubio's "weak ground game" was angering Iowa Republicans. And the New Hampshire Union Leader wrote an editorial headlined, "Marco? Marco? Where's Rubio?"He isn't in the Senate doing the work he's being paid for, we know that. But he isn't in Iowa or New Hampshire either. The reason for this seems to be that Rubio believes that his big ad spending and face time on Fox is all that's needed to win.

"More people in Iowa see Marco on ‘Fox and Friends’ than see Marco when he is in Iowa," Rubio's campaign manager, Terry Sullivan, told the New York Times. And Alberta and Johnson report that Rubio's team believes "a sprawling operation weighs down a campaign and wastes precious resources that could be spent on TV ads that reach more voters." (Presumably, Rubio isn't making more campaign trips to the early states so he can spend more time raising money that can fund these crucial ads.)Or maybe he's just lazy and thinks he can win by being charming. But then he would have to actually be charming, which he is not. As we get closer to voters actually voting, the parameters of the race are starting to change and nobody really knows where it's going. But if we were to guess right now, we would have a three-way race between Trump, Cruz and an establishment player to be named later. Rubio has always seemed like a good bet on paper but he's underperformed at everything he's done since being the anointed the GOP's answer to Barack Obama. So, there's still a space for Christie or Bush or maybe even Kasich to make a move. One thing we know, however, is that as long as the establishment dithers and is unable to coalesce around somebody, the Trump-Cruz faction gains strength and legitimacy. This whole thing may just come down to the two of them at which point the "establishment" will have to make a choice between the wingnut and the demagogue. You can decide which is which.

Another weekend, another series of Donald Trump interviews in which he runs circles around anchors who are simply flummoxed by the candidate, unable to get him to respond to questions like a normal person. Not that you can blame them. He's one slippery guy. And it has to be tough to keep your concentration when trying to talk to someone who is wearing such an odd color of make-up. So, for the most part, Trump was Trump and they were stumped. But one question did elicit some real news. When asked about Ted Cruz's comments to some donors last week in which he called Trump's qualifications to be Commander in Chief into question, for the first time Trump went on the attack against his little buddy:

Another weekend, another series of Donald Trump interviews in which he runs circles around anchors who are simply flummoxed by the candidate, unable to get him to respond to questions like a normal person. Not that you can blame them. He's one slippery guy. And it has to be tough to keep your concentration when trying to talk to someone who is wearing such an odd color of make-up. So, for the most part, Trump was Trump and they were stumped. But one question did elicit some real news. When asked about Ted Cruz's comments to some donors last week in which he called Trump's qualifications to be Commander in Chief into question, for the first time Trump went on the attack against his little buddy: "You look like the way he's dealt with the Senate, where he goes in there like -- frankly like a little bit of a maniac. You're never going to get things done that way. You can't walk into the Senate and scream and call people liars and not be able to cajole and get along with people. He'll never be able to get anything done, and that's the problem with Ted."It's unnecessary at this point to even point out how ridiculous that sounds coming from Donald Trump, the man who has insulted literally millions of his fellow Americans and most of the world, as well as the entire Republican leadership. But that's him. He's the only presidential candidate in history who actually believes he is the Green Lantern, and will, therefore, be able to rule not by fiat, but by the sheer force of his supernatural abilities to "get things done." All of this comes on the heels of polling that show a big Cruz surge, not just in Iowa, where he's overtaken Trump by a "yuuuge" margin but nationally as well. Cruz is no longer one of the fringe guys. He's for real. Some of us predicted this a while back -- he is a smart politician and he's been positioning himself to take the anti-establishment vote from one or both of the early frontrunners from the beginning. Carson lost altitude when it became obvious that his experience as a neurosurgeon did not prepare him for the rough and tumble world of presidential politics and Cruz was there to catch his followers as they fell. Now he and The Donald are fighting it out for the 50 percent of the party that thinks the biggest problem for the GOP is that it just isn't crazy enough. So Cruz tweeted a rather sweet and gentle response to Trump's taunts, indicating that he is not going to take the bait, but it's pretty clear that Trump is going to go into this week's debate loaded for bear. He does not like being in second place. Meanwhile, the putative "establishment frontrunner," Marco Rubio, whose polling remains mired in the teens at best, made an appearance on "Meet The Press" and demonstrated why that is. When asked about Trump's proposal to ban Muslims from entering the country, instead of explaining that it's both immoral and counterproductive, he chose to emulate a bucket of lukewarm water and said:

"Obviously I don’t agree with everything he says … but we can’t ignore that’s touched on some issues that people are concerned about."If he's trying to make Jeb Bush look tough by comparison, that's a good way to do it. (Indeed, one might assume at this point that any candidate on the so-called establishment track should be showing they are willing to do battle with Trump. If there's one thing that cuts across all the GOP lines, it's a deep and abiding yearning for a manly man to be a man and man-up. If you can't stand up to Trump, how are you going to stand up to all those nannies and busboys lining up at the border to destroy our way of life? How will you be able to assuage the fears of the millions of armed Republicans who eagerly face the dangerous risk of 30,000 gun deaths a year but are cowering in their boots over the prospect of being shot by a Muslim? These are the challenges any establishment Republican has to face in this election and Rubio simply isn't getting the job done. Instead, he seems to be trying to compete on the wingnut track for some reason. Last week he went on the Christian Broadcasting Network and said that he would dispose of all of President Obama's executive orders pertaining to non-discrimination against gay people and work to reverse marriage equality. Chuck Todd pressed him to explain how he would do this asking if he would endorse a constitutional amendment:

MARCO RUBIO: As I’ve said, that would be conceding that the current Constitution is somehow wrong and needs to be fixed.I don’t think the current Constitution gives the federal government the power to regulate marriage. That belongs at the state and local level. And that’s why if you want to change the definition of marriage, which is what this argument is about. It’s not about discrimination. It is about the definition of a very specific, traditional, and age-old institution. If you want to change it, you have a right to petition your state legislature and your elected representatives to do it. What is wrong is that the Supreme Court has found this hidden constitutional right that 200 years of jurisprudence had not discovered and basically overturn the will of voters in Florida where over 60% passed a constitutional amendment that defined marriage in the state constitution as the union of one man and one woman. CHUCK TODD: So are you accepting the idea of same sex marriage in perpetuity? MARCO RUBIO: It is the current law. I don’t believe any case law is settled law. Any future Supreme Court can change it. And ultimately, I will appoint Supreme Court justices that will interpret the Constitution as originally constructed.That's a pretty telling statement. It's true that the Supreme Court does reverse itself sometimes, but this is considered a rare thing that requires a great deal of deliberation. He makes it sound as if stare decisis, the legal principle that says future courts will generally treat decisions of their predecessors as "settled law" unless something very substantial has changed in society, is not something he respects. That has not traditionally been the "establishment" line what with their alleged respect for tradition and all that rot. But then Rubio doesn't seem to know that. Perhaps Rubio thinks the social conservatives will all come his way if he waves his hand at gay marriage and takes the position that all abortion should be banned in all circumstances unless the life of the mother hangs in the balance (a position that used to only be held by the most zealous of anti-abortion activists). But if he thinks he can out-Christian Ted Cruz, he has another thing coming. Cruz is the real thing down to his bones. Rubio doesn't stand a chance with that crowd unless all the others drop out, including Cruz and Trump. Perhaps the most interesting news about Rubio didn't come from either his campaign or any other Republican. Politico reported that John Podesta, Hillary Clinton's campaign chairman, said that he believed Ted Cruz was the likeliest GOP nominee, followed by Trump and then Rubio. This sentiment was echoed by Clinton supporter David Brock who said something similar. He thinks Cruz is going to win the nomination:

He’s where the id of the conservative base is, I believe strongly. He’s got a lot of money, he’s a big super PAC, he’s also got low-dollar donors. He’s playing a very long game organizationally on the ground,” Brock said. “He’s going to win Iowa, I believe, maybe not New Hampshire, but then South Carolina,” Brock said, adding that the party rules that allow for winner-take-all primaries come March will ensure a Cruz victory. Brock said he doesn't dismiss what he characterized as an outside chance that Donald Trump could win his party’s nomination — “You never discount a demagogue” — but said he is not prepared to pour resources into planning for the rise of Sen. Marco Rubio. “I just don’t see it,” he said of the young Florida senator. “He has some critical weaknesses, his absenteeism, weird listlessness on the campaign trail, all the mess with his personal finances — there’s a lot. He hasn’t been vetted.”Matthew Yglesias at Vox was confused by this and laid out a number of reasons why he thinks someone like Brock would say such a thing, ranging from a straightforward belief that Rubio is simply too weak to win to the rumors about some dirt on Rubio they know they're going to unleash that will knock him out of the race. (Maybe it's even some kind of ten dimensional chess move that Brock's playing to mess with Rubio's head.) But the most logical answer is really the simplest: Rubio is a terrible candidate. If you couldn't tell by just watching him, this article by Yglesias's colleague Andrew Prokop fills in the blanks:

Unlike most recent presidential nomination winners, who have invested serious time and effort into campaigning and building organizations in at least one of either Iowa or New Hampshire, Rubio has taken a positively relaxed approach to both. He doesn't show up very often, doesn't do much campaigning when he is around, and doesn't seem to be building very impressive field operations. And it's raising eyebrows. James Pindell of the Boston Globe wrote last week that Rubio's New Hampshire surge was "riddled with doubts," and that GOP insiders are bemoaning his "lack of staff" and "activity." National Review's Tim Alberta and Eliana Johnson reported Wednesday that Rubio's "weak ground game" was angering Iowa Republicans. And the New Hampshire Union Leader wrote an editorial headlined, "Marco? Marco? Where's Rubio?"He isn't in the Senate doing the work he's being paid for, we know that. But he isn't in Iowa or New Hampshire either. The reason for this seems to be that Rubio believes that his big ad spending and face time on Fox is all that's needed to win.

"More people in Iowa see Marco on ‘Fox and Friends’ than see Marco when he is in Iowa," Rubio's campaign manager, Terry Sullivan, told the New York Times. And Alberta and Johnson report that Rubio's team believes "a sprawling operation weighs down a campaign and wastes precious resources that could be spent on TV ads that reach more voters." (Presumably, Rubio isn't making more campaign trips to the early states so he can spend more time raising money that can fund these crucial ads.)Or maybe he's just lazy and thinks he can win by being charming. But then he would have to actually be charming, which he is not. As we get closer to voters actually voting, the parameters of the race are starting to change and nobody really knows where it's going. But if we were to guess right now, we would have a three-way race between Trump, Cruz and an establishment player to be named later. Rubio has always seemed like a good bet on paper but he's underperformed at everything he's done since being the anointed the GOP's answer to Barack Obama. So, there's still a space for Christie or Bush or maybe even Kasich to make a move. One thing we know, however, is that as long as the establishment dithers and is unable to coalesce around somebody, the Trump-Cruz faction gains strength and legitimacy. This whole thing may just come down to the two of them at which point the "establishment" will have to make a choice between the wingnut and the demagogue. You can decide which is which.

Serena Williams earned this: It is 2015, and some people would still rather see a horse named Sportsperson of the Year than a human woman

If you have a “black-sounding” name you are less likely to get a room on Airbnb

Marco Rubio’s desperate move to catch Ted Cruz: Grasping for evangelical votes by vowing to demolish gay rights

December 13, 2015

This is what the female gaze looks like: “Transparent” returns for a thrilling second season

The male gaze is a privilege perpetuator. … a product of growing up other, of growing up as not the subject. You think there’s something wrong with your voice all the time. … Women are shamed for having desire for anything — for food, for sex, for anything. We’re asked to only be the object for other people’s desire. There’s nothing that directing is about more than desire. It’s like, “I want to see this. I want to see it with this person. I want to change it. I want to change it again.”Soloway’s creation, the Golden Globe and Emmy-winning “Transparent,” is a gorgeous exploration of gender, family and sexuality, hinging around the story of the Pfefferman family, in Los Angeles. The second season of “Transparent,” which was released en masse at midnight Thursday night, is easily one of the best shows of the year. But more than that, it is also a five-hour experiment in the female gaze, that visionary perspective that barely exists at all. For all that the phrase is used as the theoretical opposite of the male gaze, it’s not clear what it would really look like. Melissa Silverstein (who quotes the same speech from Soloway that I just did) at Indiewire posits, “ I don't feel that the female gaze is simply the reverse of the male gaze,” adding, “The female gaze to me is not about pleasure or even power; it is about presence. The female gaze is about women storytellers planting their feet down and shouting with a camera: I AM HERE. I AM PRESENT. I MATTER.” There is furthermore a question of equality. Jenna Wortham, in the New York Times, finds artists who challenge the accepted “inoffensive” norms of platforms like Instagram, with either arty nude photo shoots or stains from menstrual blood. And as actress Kat Dennings memorably observed in W Magazine, the MPAA rates films as more “obscene” if they depict a woman orgasming. What is particularly thrilling about “Transparent’s" second season is how it serves as a canvas for Soloway’s broadest imaginings on a feminist and/or progressive process of filmmaking—from casting to script, from breaking stories to cinematography—while also being incredibly, beautifully well done. Ideology and creative vision do not always create brilliant results, when mixed. In Soloway’s hands, the ideology and the vision inform and enhance each other. “Transparent” is not didactic, but it does not pander, either; relatedly, it is both about the most intimate dealings between humans and also the grand ideas that move them. “Transparent’s" second season is a technical tour de force, and one that begins to forge what a cinematic female gaze would look and feel like. The result is not quite as purely id as something like “Magic Mike XXL” (which in addition to being over-the-top is also heteronormative), and not quite as inaccessible as a Marina Abramović show (which are generally in just one art gallery at a time). It’s about more than just flipping the camera around, and about more than including female voices, stories and characters. As Ariel Levy writes in the New Yorker, Soloway recruited writers from well outside the Hollywood industrial-complex for Season 2, and gave them a scriptwriting bootcamp to put them in shape. She called at least some of this mission “transfirmative action,” in an attempt to incorporate a “trans-feminine perspective.” It’s brought the show its first trans writer, Our Lady J, and another trans actor, Hari Nef. Only one writer has worked on a show before, besides Soloway herself, and that’s Bridget Bedard, previously of “Mad Men.” In the terrifically mechanized world of television writing, especially for comedy—especially for a network’s flagship show, as “Transparent” has become—this is unheard of; it’s even more out there than the auteur model adopted frequently by HBO, where one writer churns out every script, because at least that has a basis in film. And Soloway’s process for working with her crew is similarly idiosyncratic. Levy writes:

“We’re taught that the camera is male,” she said, turning to walk uphill, backward, to tone a different part of her legs. “But I’m not forcing everybody to fulfill something in my head and ‘Get it right—now get it more right.’ ” Directing with “the female gaze,” she asserted, is about creating the conditions for inspiration to flourish, and then “discerning-receiving.”Emmy winner Jeffrey Tambor affirmed this sentiment to Levy. “I have never experienced such freedom as an actor before in my life. Often, an actor will walk on a set and do the correct take, the expected take. Then sometimes the director will say, O.K., do one for yourself. That last take, that’s our starting point.” Beyond process, “Transparent” also advances a type of storytelling that doesn’t quite follow narrative convention. The second season offers a circularity that confounds the basic narrative arc, that thing that generally tracks from problem to climax to resolution. Primarily, this is through the show’s sudden, brilliant, historical framing—a semi-real, semi-imagined layer of history that the main characters never quite see clearly, but one that sits on top of and at times even infiltrates the present day. “Kina Hora,” the premiere, and “Man on the Land,” episode 9, are both standout moments of the year in television for me, and it’s because the characters in this bubble of 1933 Berlin somehow leach into Ali Pfefferman (Gaby Hoffman)’s lived experience. Michaela Watkins, who plays the disapproving mother, shuffles past Ali and stares suspiciously after her; then Ali looks down and sees ugly shoes with bells on her own feet, shoes that she read might have been used by some societies to stigmatize and oppress Jewish women, in particular. It’s extraordinarily moving; Soloway uses the same music cue for the end of both episodes, suggesting a circularity of not just the time in the show but even the season we’re watching. In the finale, Maura visits her mother for the first time since her transition, and we are brought back to her painful birth, where her father was convinced they’d have a girl, and the doctors saw it differently. If you hadn’t put it together before, you will by the final scene—the innocent young girl in 1933, whose brother transitioned into a sister, becomes the silent, embittered woman in 2015, who can barely keep her attention on her surroundings. Things come full circle, but also, things are a circle. Soloway told the New Yorker that “the untrustworthy vagina” is “discerning-receiving”; in “Transparent,” time is, too. This circularity comes to play with the arc of Season 2, as well, because nothing exactly happens. There are some shifts and resettlings, but as was the case in Season 1, much of the story of “Transparent” is of a family engaged in the slow process of becoming whatever they already were. It ends somewhat as it begins—a point in the middle of a process—and favors the excavation of moments to the mapping of arcs. Characters revisit old territory and break new ground, but ultimately exist in about the same plot of land—the Pfefferman homestead, as it were. And in that space, certain moments become indelible. Instead of leveraging the action forward, they weave into the fabric of the place—become bricks in the mythos of the Pfefferman family. In a sense, the experience envelops the family, and this enveloping is another distinctly feminine one. The thinker Douglas Rushkoff, just earlier this month, used language to describe the Internet that would work just as well for “Transparent”:

Archetypally speaking, the Internet is a feminine space. The Internet is something you enter into, that you're enveloped by. … The Internet works through a series of connections. There is no ending. There is no finale. There is no climax and sleep, there's just another connection, another connection, another connection and the more and more you connect, the more potentially euphoric it becomes, the more empathic it becomes, the more connected we all are, the more intimate it all is.Indeed, the opposition between male narratives and female narratives are the subject of Camille Paglia’s “Sexual Personae,” including the much-mocked line: “Male urination really is a kind of accomplishment, an arc of transcendance. A woman merely waters the ground she stands on.” The Pfeffermans are mucking up their own ground again and again, but as is demonstrated, it’s not “merely” anything. Even the show’s interest in Judaism is caught up in a female perspective; Soloway cited Andrea Dworkin to Ms. Magazine, observing that “anti-Semitism is really just hatred of the feminine: They’re both rooted in a fear of questions. Womanhood and Jewishness are both experiences that are centered around questions, and we live in a world dominated by perspectives—in terms of both religion and gender—that are overwhelmingly answer-oriented.” “Transparent” is almost intimidatingly well-versed in its feminist theory—but what I appreciate about this season is that it’s not beholden to it. Instead, through storytelling, it is embracing radical acts, and then presenting them—discerning-receiving—to the audience. It boils down to not just how beautifully filmed the season is (or isn’t), or how radically inclusive the cast is (or isn’t), but instead on what Soloway and her team has chosen to focus on. The female gaze of “Transparent” is obvious in what “Transparent” has chosen to be about, and how it has gone about doing those things. There is a welcome transparency here, to a wholly different experience of humanity that still regularly struggles for a place in the spotlight. It feels like the blinds have finally been rolled up, so we can see the world beyond the glass.[Note: This review includes plot details for the entire season of “Transparent,” now streaming on Amazon Prime.] In 2014, Jill Soloway told Ms. Magazine that female showrunners like herself were “essentially inventing the female gaze right now.” This summer, while presenting a lineup of film shorts directed by women, she elaborated:

The male gaze is a privilege perpetuator. … a product of growing up other, of growing up as not the subject. You think there’s something wrong with your voice all the time. … Women are shamed for having desire for anything — for food, for sex, for anything. We’re asked to only be the object for other people’s desire. There’s nothing that directing is about more than desire. It’s like, “I want to see this. I want to see it with this person. I want to change it. I want to change it again.”Soloway’s creation, the Golden Globe and Emmy-winning “Transparent,” is a gorgeous exploration of gender, family and sexuality, hinging around the story of the Pfefferman family, in Los Angeles. The second season of “Transparent,” which was released en masse at midnight Thursday night, is easily one of the best shows of the year. But more than that, it is also a five-hour experiment in the female gaze, that visionary perspective that barely exists at all. For all that the phrase is used as the theoretical opposite of the male gaze, it’s not clear what it would really look like. Melissa Silverstein (who quotes the same speech from Soloway that I just did) at Indiewire posits, “ I don't feel that the female gaze is simply the reverse of the male gaze,” adding, “The female gaze to me is not about pleasure or even power; it is about presence. The female gaze is about women storytellers planting their feet down and shouting with a camera: I AM HERE. I AM PRESENT. I MATTER.” There is furthermore a question of equality. Jenna Wortham, in the New York Times, finds artists who challenge the accepted “inoffensive” norms of platforms like Instagram, with either arty nude photo shoots or stains from menstrual blood. And as actress Kat Dennings memorably observed in W Magazine, the MPAA rates films as more “obscene” if they depict a woman orgasming. What is particularly thrilling about “Transparent’s" second season is how it serves as a canvas for Soloway’s broadest imaginings on a feminist and/or progressive process of filmmaking—from casting to script, from breaking stories to cinematography—while also being incredibly, beautifully well done. Ideology and creative vision do not always create brilliant results, when mixed. In Soloway’s hands, the ideology and the vision inform and enhance each other. “Transparent” is not didactic, but it does not pander, either; relatedly, it is both about the most intimate dealings between humans and also the grand ideas that move them. “Transparent’s" second season is a technical tour de force, and one that begins to forge what a cinematic female gaze would look and feel like. The result is not quite as purely id as something like “Magic Mike XXL” (which in addition to being over-the-top is also heteronormative), and not quite as inaccessible as a Marina Abramović show (which are generally in just one art gallery at a time). It’s about more than just flipping the camera around, and about more than including female voices, stories and characters. As Ariel Levy writes in the New Yorker, Soloway recruited writers from well outside the Hollywood industrial-complex for Season 2, and gave them a scriptwriting bootcamp to put them in shape. She called at least some of this mission “transfirmative action,” in an attempt to incorporate a “trans-feminine perspective.” It’s brought the show its first trans writer, Our Lady J, and another trans actor, Hari Nef. Only one writer has worked on a show before, besides Soloway herself, and that’s Bridget Bedard, previously of “Mad Men.” In the terrifically mechanized world of television writing, especially for comedy—especially for a network’s flagship show, as “Transparent” has become—this is unheard of; it’s even more out there than the auteur model adopted frequently by HBO, where one writer churns out every script, because at least that has a basis in film. And Soloway’s process for working with her crew is similarly idiosyncratic. Levy writes:

“We’re taught that the camera is male,” she said, turning to walk uphill, backward, to tone a different part of her legs. “But I’m not forcing everybody to fulfill something in my head and ‘Get it right—now get it more right.’ ” Directing with “the female gaze,” she asserted, is about creating the conditions for inspiration to flourish, and then “discerning-receiving.”Emmy winner Jeffrey Tambor affirmed this sentiment to Levy. “I have never experienced such freedom as an actor before in my life. Often, an actor will walk on a set and do the correct take, the expected take. Then sometimes the director will say, O.K., do one for yourself. That last take, that’s our starting point.” Beyond process, “Transparent” also advances a type of storytelling that doesn’t quite follow narrative convention. The second season offers a circularity that confounds the basic narrative arc, that thing that generally tracks from problem to climax to resolution. Primarily, this is through the show’s sudden, brilliant, historical framing—a semi-real, semi-imagined layer of history that the main characters never quite see clearly, but one that sits on top of and at times even infiltrates the present day. “Kina Hora,” the premiere, and “Man on the Land,” episode 9, are both standout moments of the year in television for me, and it’s because the characters in this bubble of 1933 Berlin somehow leach into Ali Pfefferman (Gaby Hoffman)’s lived experience. Michaela Watkins, who plays the disapproving mother, shuffles past Ali and stares suspiciously after her; then Ali looks down and sees ugly shoes with bells on her own feet, shoes that she read might have been used by some societies to stigmatize and oppress Jewish women, in particular. It’s extraordinarily moving; Soloway uses the same music cue for the end of both episodes, suggesting a circularity of not just the time in the show but even the season we’re watching. In the finale, Maura visits her mother for the first time since her transition, and we are brought back to her painful birth, where her father was convinced they’d have a girl, and the doctors saw it differently. If you hadn’t put it together before, you will by the final scene—the innocent young girl in 1933, whose brother transitioned into a sister, becomes the silent, embittered woman in 2015, who can barely keep her attention on her surroundings. Things come full circle, but also, things are a circle. Soloway told the New Yorker that “the untrustworthy vagina” is “discerning-receiving”; in “Transparent,” time is, too. This circularity comes to play with the arc of Season 2, as well, because nothing exactly happens. There are some shifts and resettlings, but as was the case in Season 1, much of the story of “Transparent” is of a family engaged in the slow process of becoming whatever they already were. It ends somewhat as it begins—a point in the middle of a process—and favors the excavation of moments to the mapping of arcs. Characters revisit old territory and break new ground, but ultimately exist in about the same plot of land—the Pfefferman homestead, as it were. And in that space, certain moments become indelible. Instead of leveraging the action forward, they weave into the fabric of the place—become bricks in the mythos of the Pfefferman family. In a sense, the experience envelops the family, and this enveloping is another distinctly feminine one. The thinker Douglas Rushkoff, just earlier this month, used language to describe the Internet that would work just as well for “Transparent”:

Archetypally speaking, the Internet is a feminine space. The Internet is something you enter into, that you're enveloped by. … The Internet works through a series of connections. There is no ending. There is no finale. There is no climax and sleep, there's just another connection, another connection, another connection and the more and more you connect, the more potentially euphoric it becomes, the more empathic it becomes, the more connected we all are, the more intimate it all is.Indeed, the opposition between male narratives and female narratives are the subject of Camille Paglia’s “Sexual Personae,” including the much-mocked line: “Male urination really is a kind of accomplishment, an arc of transcendance. A woman merely waters the ground she stands on.” The Pfeffermans are mucking up their own ground again and again, but as is demonstrated, it’s not “merely” anything. Even the show’s interest in Judaism is caught up in a female perspective; Soloway cited Andrea Dworkin to Ms. Magazine, observing that “anti-Semitism is really just hatred of the feminine: They’re both rooted in a fear of questions. Womanhood and Jewishness are both experiences that are centered around questions, and we live in a world dominated by perspectives—in terms of both religion and gender—that are overwhelmingly answer-oriented.” “Transparent” is almost intimidatingly well-versed in its feminist theory—but what I appreciate about this season is that it’s not beholden to it. Instead, through storytelling, it is embracing radical acts, and then presenting them—discerning-receiving—to the audience. It boils down to not just how beautifully filmed the season is (or isn’t), or how radically inclusive the cast is (or isn’t), but instead on what Soloway and her team has chosen to focus on. The female gaze of “Transparent” is obvious in what “Transparent” has chosen to be about, and how it has gone about doing those things. There is a welcome transparency here, to a wholly different experience of humanity that still regularly struggles for a place in the spotlight. It feels like the blinds have finally been rolled up, so we can see the world beyond the glass.[Note: This review includes plot details for the entire season of “Transparent,” now streaming on Amazon Prime.] In 2014, Jill Soloway told Ms. Magazine that female showrunners like herself were “essentially inventing the female gaze right now.” This summer, while presenting a lineup of film shorts directed by women, she elaborated:

The male gaze is a privilege perpetuator. … a product of growing up other, of growing up as not the subject. You think there’s something wrong with your voice all the time. … Women are shamed for having desire for anything — for food, for sex, for anything. We’re asked to only be the object for other people’s desire. There’s nothing that directing is about more than desire. It’s like, “I want to see this. I want to see it with this person. I want to change it. I want to change it again.”Soloway’s creation, the Golden Globe and Emmy-winning “Transparent,” is a gorgeous exploration of gender, family and sexuality, hinging around the story of the Pfefferman family, in Los Angeles. The second season of “Transparent,” which was released en masse at midnight Thursday night, is easily one of the best shows of the year. But more than that, it is also a five-hour experiment in the female gaze, that visionary perspective that barely exists at all. For all that the phrase is used as the theoretical opposite of the male gaze, it’s not clear what it would really look like. Melissa Silverstein (who quotes the same speech from Soloway that I just did) at Indiewire posits, “ I don't feel that the female gaze is simply the reverse of the male gaze,” adding, “The female gaze to me is not about pleasure or even power; it is about presence. The female gaze is about women storytellers planting their feet down and shouting with a camera: I AM HERE. I AM PRESENT. I MATTER.” There is furthermore a question of equality. Jenna Wortham, in the New York Times, finds artists who challenge the accepted “inoffensive” norms of platforms like Instagram, with either arty nude photo shoots or stains from menstrual blood. And as actress Kat Dennings memorably observed in W Magazine, the MPAA rates films as more “obscene” if they depict a woman orgasming. What is particularly thrilling about “Transparent’s" second season is how it serves as a canvas for Soloway’s broadest imaginings on a feminist and/or progressive process of filmmaking—from casting to script, from breaking stories to cinematography—while also being incredibly, beautifully well done. Ideology and creative vision do not always create brilliant results, when mixed. In Soloway’s hands, the ideology and the vision inform and enhance each other. “Transparent” is not didactic, but it does not pander, either; relatedly, it is both about the most intimate dealings between humans and also the grand ideas that move them. “Transparent’s" second season is a technical tour de force, and one that begins to forge what a cinematic female gaze would look and feel like. The result is not quite as purely id as something like “Magic Mike XXL” (which in addition to being over-the-top is also heteronormative), and not quite as inaccessible as a Marina Abramović show (which are generally in just one art gallery at a time). It’s about more than just flipping the camera around, and about more than including female voices, stories and characters. As Ariel Levy writes in the New Yorker, Soloway recruited writers from well outside the Hollywood industrial-complex for Season 2, and gave them a scriptwriting bootcamp to put them in shape. She called at least some of this mission “transfirmative action,” in an attempt to incorporate a “trans-feminine perspective.” It’s brought the show its first trans writer, Our Lady J, and another trans actor, Hari Nef. Only one writer has worked on a show before, besides Soloway herself, and that’s Bridget Bedard, previously of “Mad Men.” In the terrifically mechanized world of television writing, especially for comedy—especially for a network’s flagship show, as “Transparent” has become—this is unheard of; it’s even more out there than the auteur model adopted frequently by HBO, where one writer churns out every script, because at least that has a basis in film. And Soloway’s process for working with her crew is similarly idiosyncratic. Levy writes:

“We’re taught that the camera is male,” she said, turning to walk uphill, backward, to tone a different part of her legs. “But I’m not forcing everybody to fulfill something in my head and ‘Get it right—now get it more right.’ ” Directing with “the female gaze,” she asserted, is about creating the conditions for inspiration to flourish, and then “discerning-receiving.”Emmy winner Jeffrey Tambor affirmed this sentiment to Levy. “I have never experienced such freedom as an actor before in my life. Often, an actor will walk on a set and do the correct take, the expected take. Then sometimes the director will say, O.K., do one for yourself. That last take, that’s our starting point.” Beyond process, “Transparent” also advances a type of storytelling that doesn’t quite follow narrative convention. The second season offers a circularity that confounds the basic narrative arc, that thing that generally tracks from problem to climax to resolution. Primarily, this is through the show’s sudden, brilliant, historical framing—a semi-real, semi-imagined layer of history that the main characters never quite see clearly, but one that sits on top of and at times even infiltrates the present day. “Kina Hora,” the premiere, and “Man on the Land,” episode 9, are both standout moments of the year in television for me, and it’s because the characters in this bubble of 1933 Berlin somehow leach into Ali Pfefferman (Gaby Hoffman)’s lived experience. Michaela Watkins, who plays the disapproving mother, shuffles past Ali and stares suspiciously after her; then Ali looks down and sees ugly shoes with bells on her own feet, shoes that she read might have been used by some societies to stigmatize and oppress Jewish women, in particular. It’s extraordinarily moving; Soloway uses the same music cue for the end of both episodes, suggesting a circularity of not just the time in the show but even the season we’re watching. In the finale, Maura visits her mother for the first time since her transition, and we are brought back to her painful birth, where her father was convinced they’d have a girl, and the doctors saw it differently. If you hadn’t put it together before, you will by the final scene—the innocent young girl in 1933, whose brother transitioned into a sister, becomes the silent, embittered woman in 2015, who can barely keep her attention on her surroundings. Things come full circle, but also, things are a circle. Soloway told the New Yorker that “the untrustworthy vagina” is “discerning-receiving”; in “Transparent,” time is, too. This circularity comes to play with the arc of Season 2, as well, because nothing exactly happens. There are some shifts and resettlings, but as was the case in Season 1, much of the story of “Transparent” is of a family engaged in the slow process of becoming whatever they already were. It ends somewhat as it begins—a point in the middle of a process—and favors the excavation of moments to the mapping of arcs. Characters revisit old territory and break new ground, but ultimately exist in about the same plot of land—the Pfefferman homestead, as it were. And in that space, certain moments become indelible. Instead of leveraging the action forward, they weave into the fabric of the place—become bricks in the mythos of the Pfefferman family. In a sense, the experience envelops the family, and this enveloping is another distinctly feminine one. The thinker Douglas Rushkoff, just earlier this month, used language to describe the Internet that would work just as well for “Transparent”:

Archetypally speaking, the Internet is a feminine space. The Internet is something you enter into, that you're enveloped by. … The Internet works through a series of connections. There is no ending. There is no finale. There is no climax and sleep, there's just another connection, another connection, another connection and the more and more you connect, the more potentially euphoric it becomes, the more empathic it becomes, the more connected we all are, the more intimate it all is.Indeed, the opposition between male narratives and female narratives are the subject of Camille Paglia’s “Sexual Personae,” including the much-mocked line: “Male urination really is a kind of accomplishment, an arc of transcendance. A woman merely waters the ground she stands on.” The Pfeffermans are mucking up their own ground again and again, but as is demonstrated, it’s not “merely” anything. Even the show’s interest in Judaism is caught up in a female perspective; Soloway cited Andrea Dworkin to Ms. Magazine, observing that “anti-Semitism is really just hatred of the feminine: They’re both rooted in a fear of questions. Womanhood and Jewishness are both experiences that are centered around questions, and we live in a world dominated by perspectives—in terms of both religion and gender—that are overwhelmingly answer-oriented.” “Transparent” is almost intimidatingly well-versed in its feminist theory—but what I appreciate about this season is that it’s not beholden to it. Instead, through storytelling, it is embracing radical acts, and then presenting them—discerning-receiving—to the audience. It boils down to not just how beautifully filmed the season is (or isn’t), or how radically inclusive the cast is (or isn’t), but instead on what Soloway and her team has chosen to focus on. The female gaze of “Transparent” is obvious in what “Transparent” has chosen to be about, and how it has gone about doing those things. There is a welcome transparency here, to a wholly different experience of humanity that still regularly struggles for a place in the spotlight. It feels like the blinds have finally been rolled up, so we can see the world beyond the glass.

An open letter to Justice Scalia

Dear Justice Scalia,

On Wednesday, as you heard arguments in the affirmative action case Fisher v. University of Texas, you suggested that black students should enroll at “slower-track school[s],” rather than study alongside white students at the university. “I don’t think it stands to reason that it’s a good thing for the University of Texas to admit as many blacks as possible,” you said. Your words reinforced a panoply of false stereotypes about the intellectual abilities of African Americans and underscored what many Americans fear: that our institutions of higher learning are somehow overrun with minorities who have “taken” white students’ rightful spots. You ignored the fact that the University of Texas’s holistic admissions program isn’t about “admit[ting] as many blacks as possible;” that it’s a tailored procedure designed to ensure diversity in each freshman class, and it follows guidelines endorsed by the Supreme Court in 2003. But your choice of wording telegraphs a message that many Americans are all too willing to believe: that black people can’t compete in academically rigorous environments. This is a message to which I, as an artist and educator of color, feel compelled to respond.

In 1994, I was a high school freshman when a book called The Bell Curve was published to extensive attention. The treatise, authored by Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles Murray, argued that human intelligence is heritable and that various ethnic groups have measurably different levels of intelligence. In a series of now-debunked statistical analyses, the Bell Curve authors suggested that African Americans have lower intelligence (as measured by IQ) than whites or Asians, a factor that supposedly predestines us for a host of social misfortunes, like poverty and teen pregnancy. The book’s conclusions weren’t closely examined prior to publication, but that didn’t stop The Bell Curve from selling 400,000 copies in hardcover or spending fifteen weeks on the New York Times best seller list. Thousands of people were willing to hand over good money to buy into this book’s awful premise.

As a result, I entered high school knowing precisely how low an opinion many Americans had of black students like me. I already knew I’d have to work hard to achieve success, but the praise for that book—author interviews, pundit commentary—made me see what I was up against. While I was lucky to find supportive teachers and friends throughout my education, my mixed-race heritage baffled many of the other adults around me. I recall family friends congratulating me on my academic successes by implying that I “must have gotten that from Dad,” while my singing talent was ascribed to my African American mother. I responded to most of these statements with a healthy eyeroll, but I understood that my achievements continually would be “surprising” to certain observers, and that I’d have to keep proving that I deserved to be exactly where I was. This never ends, by the way.

When I was accepted to the Iowa Writers' Workshop, a friend who’d applied to the same program asked, pointedly, whether the fellowship I’d won was “something for African Americans.” In the moment, I understood his anxiety; he was still waiting for an acceptance letter. But this friend had never talked to me that way before; we’d never drawn asterisks beside each other’s achievements. As it happened, my fellowship from Iowa was for underrepresented students, but of course, you had to meet the highly selective requirements of your program first, and show exceptional talent. No “slower-track” needed, thanks. Even now, as a teacher, my color confounds. A colleague at one of my first teaching jobs once looked me up and down, and asked, “which half of you is black?” as if my body were divided by a secret equator, or dipped in invisible ink. At another moment in my early teaching career, a student who was unhappy with her grade surreptitiously snapped a photo of me at my lectern and tweeted that my afro made it impossible to take me seriously as a professor.

Justice Scalia, I want to remind you that we share this country together. I’m descended from free and enslaved people. Some of them were black Virginians who worked hard to attain literacy and economic mobility in a nation that continually excluded them from the body politic. In fact, I hold a BA from the University of Virginia, where you spent four years as a Professor of Law, and an MA from the University of Chicago, another institution where you taught. And we share more than academics. My European ancestors arrived in America as Italian immigrants, just as yours did. You must know that the privileges of “whiteness” were not automatically bestowed on Italians. It wasn’t that long ago that Creuzé de Lesser wrote, “Europe ends at Naples, and ends badly. Calabria, Sicily, and all the rest belong to Africa.” At the height of the immigration wave, Italian Americans were subject to discrimination and violence, to negative stereotypes and offensive caricatures. In public schools, Italian children were discouraged from speaking their native language, even at home, while in the workplace, their parents often were barred from all but the lowest-paying manual labor jobs. The Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 was authorized, in large part, to curtail immigration from southern and eastern Europe. Today, we recognize how unfair all of this was, and we celebrate the contributions of Italian Americans in every sector of public life.

But as Republican presidential candidates call for sealing our borders to Muslim immigrants, and as increasing numbers of Americans react to world events with fearful xenophobia, your words feed into a stream of ugly “othering” that must end. I think you know that skin color is no predictor of intellectual acuity or future success in school. Students who are admitted to colleges and universities have the right to a rewarding education full of discoveries and challenges. This is the blessing of equal protection in public education. The Court must uphold it. Your comments this week show that you prefer to think of your fellow Americans, and especially African Americans, as points on a graph. But that approach reflects the exact type of one-size-fits-all thinking that you claim to oppose in affirmative action policy. Even worse, because you make no room in your comments for the health of the campus communities that admissions policies are designed to serve. Diversity benefits the whole campus. Every day, I’m thankful for the students I’m privileged to teach. They come from rural and urban areas, they practice Christian and non-Christian religions, they’re young parents and returning veterans and hopeful poets. We need them all.

Allow me to describe something for you: in the mountains of Fumin County, in the southern Chinese province of Yunnan, there’s a slender village road that twists through a landscape of clouds and red earth. At the center of town is a Christian church where young people, dressed in colorful robes, gather to sing the Hallelujah Chorus from Handel’s Messiah in crystalline harmony. They do this each evening, after completing their farm work. The choir is famous. The singers know hundreds of songs and can sing in multiple languages. If you go there, as I did several years ago, they will sing for you. Afterwards, they’ll invite you to ask as many questions as you wish about their culture (the Miao people) and it’s only polite to return their invitation. What would you like to know about my country? You’ll ask. But the singers of Xiaoshuijing will have just one question: Tell us about your choirs.

Justice Scalia, I wish to imagine America as a great chorus of unfolding voices, a massive instrument. When I think of the Xiaoshuijing singers, of the mystery that moved through their question so beautifully asked, I’m nearly undone. But I’m a professor of poetry; I live for beautiful questions. As a Supreme Court Justice, you move in the realm of answers, interpretations, solutions. Sometimes I wonder whose voice you hear. What’s it like to hear the law speaking with a singular voice, immutable from the moment of ratification? Over the years, you’ve sparred with Justice Breyer and others about how the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision was reached. It seems that this vital ruling doesn’t square as neatly as you’d like with your originalist approach to constitutional interpretation. You’ve had to return to the issue in public comments, and you’ve consistently voted to weaken laws and policies, like affirmative action and the Voting Rights Act, designed to remedy the damage caused by our nation’s ongoing romance with structural racism.

Where should black students study? What schools are best for them? These questions already have been settled as a matter of constitutional law and they are not before you in the current case. The problem we must resolve as a society is not where to send students of color, but how to acknowledge the humanity of every American and how to ensure an educated populace for future generations. When I left my hometown for college, I was a black student. So? What else? I was a woman, an Italian American, a singer, a writer, an intellectual. I made good decisions to attend UVA, Chicago, and Iowa, and those institutions made good decisions by accepting me. Just like any other student, it was my responsibility to seek success for myself, to find mentors, to compete in the academic environments where I found myself, and to try to leave the place a little better than I found it. Who were you when you left for college, Your Honor? I’m sure the answer would not fit comfortably into a single sentence, a solitary line of prose. Remember there are 350 million Americans who are just as complex as you are. Imagine the sound we could make with all of our voices.

We’re not beating ISIS like this: America has no easy solution to its Middle Eastern crisis — and maybe none at all

Age of the Fabricating Faker: All the Republican candidates embody this condition — but none so much as Donald Trump