Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 885

January 23, 2016

Let’s make an honest man of Ted Cruz. Here’s how we resolve his “birther” dilemma with integrity

Lissie: “I genuinely want a politician who challenges the corruption of our system”

The GOP’s Trump meltdown hits critical mass — but can the right’s empty suits stop him now?

The Bundy fallacy liberals must reject: Why reforming our broken criminal justice system means less violence, not more

“Why won’t they shoot at armed white fanatics isn’t just the wrong question; it’s a bad one. Not only does it hold lethal violence as a fair response to the Bundy militia, but it opens a path to legitimizing the same violence against more marginalized groups...If we’re outraged, it shouldn’t be because law enforcement isn’t rushing to violently confront Bundy and his group. We should be outraged because that restraint isn’t extended to all Americans.”The Black Lives Matter movement has drawn critical scrutiny to mass incarceration and abusive policing, and made the point that both impact black people in a grossly disproportionate manner. How disproportionate? ProPublica found that young black males were 21 times more likely to be shot dead by police than their white counterparts in recent years. In 2014, black men were 7.6 times more likely to be imprisoned than white men, according to the Marshall Project. Some have also, however, taken that argument a step further and asserted that police and the criminal justice system treat white criminals too kindly. Last June, there was the internet firestorm in response to the news that “Police bought Dylann Storm Roof Burger King after arrest.” That same month, Mic displayed a photo of bikers checking their phones and hanging out after a shootout left nine dead in Waco, Texas as one of multiple “Stunning Images” that “Reveal the Racist Double Standard of Police Responses in America.” In reality, bikers present for that shootout have been subjected to one of the most indiscriminate mass prosecutions (177 people were arrested) in recent history. Before that, in late 2014, the #crimingwhilewhite hashtag exploded. https://twitter.com/grace134/status/5... ThinkProgress dubbed #CrimingWhileWhite “The Only Thing You Need To Read To Understand White Privilege.” White people's confessions of getting away with crimes were intended to highlight the criminal justice system's racism. Some, like Jessica Valenti, criticized the e-movement for highlighting white people's experiences at a time when black suffering needed to be in sharp focus. What was most unfortunate about #CrimingWhileWhite, however, is that it came off like a bunch of affluent white people talking about experiences that poor white people might find entirely unrecognizable. Controlling for class, there is still a major racial disparity in incarceration rates—but far less of one, according to a 2010 study published in Daedalus. The authors looked at men born between 1975 and 1979 and found that, over all, the black men were five times more likely than white counterparts to serve time in prison (27 versus 5 percent) by their early thirties. By contrast, black high school dropouts were two-and-a-half times more likely to enter prison than white dropouts (68 versus 28 percent). Poor blacks are hit much the hardest: the hyperincarceration that governs life in extremely poor and highly segregated black neighborhoods is a unique phenomenon. But poor whites have it bad as well. The black members of the studied cohort with a high school education were less likely to enter prison than a white high school dropout, and far less likely if they had a college degree. Affluent black people share aspects of racial discrimination and disadvantage with poor black people, and poor whites share some white privilege with rich whites. But poor blacks on the South Side of Chicago and poor whites in Appalachia also share an experience of economic marginalization, incarceration included, that is utterly foreign to most well-to-do people of any color.

* * *

Research suggests that when white people are confronted with evidence of the criminal justice systems's racist impact they are actually more likely to support punitive policies. This is because of racism, and because emphasizing racial disparity risks reinforcing racist stereotypes about black criminality. It's also because the American left lacks much in the way of a multiracial working class movement. Anyone who has spent time covering the criminal justice system, or spent time inside of it, is aware of countless stories of white (not to mention Latino) people unjustly jammed up. The majority of the victims of police brutality and unjust imprisonment that I've interviewed and written about, in Philadelphia and elsewhere, are black. But not all. The abusive cops and prison guards I've encountered, contrary to the media's insistent references to certain abusive officers being white, were both black and white. The system is fundamentally racist. But it is also a machine that destroys poor and working class people of all colors. Take Sean Harrington, who I profiled in a Vice investigation last September. Harrington, a white heroin addict, is facing a murder charge and 15 years in prison for providing drugs to a friend who suffered a fatal overdose. North Carolina prosecutor Greg Newman's carceral instincts are mercilessly inclusive: “if you're going to be out peddling the drugs,” he told me, “you're going to have be accountable to what happens on the receiving end of those narcotics.” Rico Moore, a black lawyer representing a poor white man in West Virginia facing similar charges, told me that the system uses the “same playbook” against poor people of all races. "I think, of course, poor defendants get treated like lesser citizens the same as black defendants,” he said. One case that got a bit of national attention was that of Zachary Hammond, a white teen shot dead by Seneca, South Carolina police as he tried to drive away from a drug sting. Most media attention focused on whether he was getting less media attention because he was white. “If Zachary were black, the outpouring of protest and disappointment from the public and the press would be amazing,” Eric Bland, Hammond's lawyer, protested. “You wouldn’t be able to get a hotel room in upstate South Carolina.” In reality, most of the people tweeting about #ZacharyHammond seem to be Black Lives Matters supporters — including after it was announce that the officer who executed the teen would not be charged. It's not the job of black activists to highlight white victims of mass incarceration and police abuse, though they do. The #alllivesmatter camp, to be sure, was not out marching in the street demanding justice for Zachary Hammond. White privilege and white supremacy are very real. But it's also no wonder that white liberal arts graduates have an easier time understanding white privilege than an out of work white miner or factory worker: it's hard to ruminate about one's race advantage when you're getting hammered on the economic margins. The debates pitting race against class are tired and counterproductive (and to poor black people, perhaps entirely ludicrous). More to the point would be a conversation that makes sense of people's different, difficult realities. You can't do that if you belittle poor white people as rednecks, and succumb to a vision of American politics as a cultural phenomenon reflected on Wolf Blitzer's color-coded election maps. In the late 1960s, Black Panthers in Chicago were building a Rainbow Coalition with Puerto Rican Young Lords and Appalachian migrant Young Patriots to take on poverty, police brutality and Mayor Richard Daley before leader Fred Hampton was murdered by police at the age of 21. "There's...people on welfare up here,” said Black Panther Bobby Lee, in a powerful meeting with militant Appalachians. “There's police brutality up here. There's rats and roaches. There's poverty up here. That's the first thing that we...can unite on." [embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=js7SI... Today, it is prisoners who may be leading us out of the rabbit hole of some of the less productive arguments about race and class. Three years ago in California, alleged leaders of rival race-based gangs—the Aryan Brotherhood, the Black Guerrilla Family, the Mexican Mafia and Nuestra Familia—who had spent years locked inside Pelican Bay State Prison's dystopian solitary confinement unit, organized 30,000 prisoners statewide to go on hunger strike. As Sitawa Jamaa, an alleged leader of the Black Guerrilla Family, put it: "We are a prisoner class now." A failure to recognize the fact that mass incarceration poses a threat to Americans of all races misses an opportunity to build the only sort of broad-based coalition that can bring the system down. It also, if history is any lesson, poses a major risk. Liberal criticism of racial sentencing inequities helped pave the way for the 1984 law that created the sentencing guidelines that, alongside mandatory minimums, have helped drive the federal prison system's explosive growth. Sentences are still disparate. And they are much, much longer. Demands that the criminal justice system solve our problems, and that it treat people equally, could once again result in more brutality across the board. The people goading the federal government into a bloodbath in Oregon should be mindful of this history. Black Lives Matter has cast an unprecedented spotlight on the criminal justice system. A rainbow coalition could learn a lot from the brutality they have illuminated.It has been three weeks now since the federal government's cautious approach toward right-wing militants occupying the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge sparked outrage on the left and the bigoted hashtag #YallQaeda (read: white trash ). This is a reminder that when it comes to certain crimes, some on the left reserve the right to a law-and-order response. At Slate, Jamelle Bouie observered:“Why won’t they shoot at armed white fanatics isn’t just the wrong question; it’s a bad one. Not only does it hold lethal violence as a fair response to the Bundy militia, but it opens a path to legitimizing the same violence against more marginalized groups...If we’re outraged, it shouldn’t be because law enforcement isn’t rushing to violently confront Bundy and his group. We should be outraged because that restraint isn’t extended to all Americans.”The Black Lives Matter movement has drawn critical scrutiny to mass incarceration and abusive policing, and made the point that both impact black people in a grossly disproportionate manner. How disproportionate? ProPublica found that young black males were 21 times more likely to be shot dead by police than their white counterparts in recent years. In 2014, black men were 7.6 times more likely to be imprisoned than white men, according to the Marshall Project. Some have also, however, taken that argument a step further and asserted that police and the criminal justice system treat white criminals too kindly. Last June, there was the internet firestorm in response to the news that “Police bought Dylann Storm Roof Burger King after arrest.” That same month, Mic displayed a photo of bikers checking their phones and hanging out after a shootout left nine dead in Waco, Texas as one of multiple “Stunning Images” that “Reveal the Racist Double Standard of Police Responses in America.” In reality, bikers present for that shootout have been subjected to one of the most indiscriminate mass prosecutions (177 people were arrested) in recent history. Before that, in late 2014, the #crimingwhilewhite hashtag exploded. https://twitter.com/grace134/status/5... ThinkProgress dubbed #CrimingWhileWhite “The Only Thing You Need To Read To Understand White Privilege.” White people's confessions of getting away with crimes were intended to highlight the criminal justice system's racism. Some, like Jessica Valenti, criticized the e-movement for highlighting white people's experiences at a time when black suffering needed to be in sharp focus. What was most unfortunate about #CrimingWhileWhite, however, is that it came off like a bunch of affluent white people talking about experiences that poor white people might find entirely unrecognizable. Controlling for class, there is still a major racial disparity in incarceration rates—but far less of one, according to a 2010 study published in Daedalus. The authors looked at men born between 1975 and 1979 and found that, over all, the black men were five times more likely than white counterparts to serve time in prison (27 versus 5 percent) by their early thirties. By contrast, black high school dropouts were two-and-a-half times more likely to enter prison than white dropouts (68 versus 28 percent). Poor blacks are hit much the hardest: the hyperincarceration that governs life in extremely poor and highly segregated black neighborhoods is a unique phenomenon. But poor whites have it bad as well. The black members of the studied cohort with a high school education were less likely to enter prison than a white high school dropout, and far less likely if they had a college degree. Affluent black people share aspects of racial discrimination and disadvantage with poor black people, and poor whites share some white privilege with rich whites. But poor blacks on the South Side of Chicago and poor whites in Appalachia also share an experience of economic marginalization, incarceration included, that is utterly foreign to most well-to-do people of any color.

* * *

Research suggests that when white people are confronted with evidence of the criminal justice systems's racist impact they are actually more likely to support punitive policies. This is because of racism, and because emphasizing racial disparity risks reinforcing racist stereotypes about black criminality. It's also because the American left lacks much in the way of a multiracial working class movement. Anyone who has spent time covering the criminal justice system, or spent time inside of it, is aware of countless stories of white (not to mention Latino) people unjustly jammed up. The majority of the victims of police brutality and unjust imprisonment that I've interviewed and written about, in Philadelphia and elsewhere, are black. But not all. The abusive cops and prison guards I've encountered, contrary to the media's insistent references to certain abusive officers being white, were both black and white. The system is fundamentally racist. But it is also a machine that destroys poor and working class people of all colors. Take Sean Harrington, who I profiled in a Vice investigation last September. Harrington, a white heroin addict, is facing a murder charge and 15 years in prison for providing drugs to a friend who suffered a fatal overdose. North Carolina prosecutor Greg Newman's carceral instincts are mercilessly inclusive: “if you're going to be out peddling the drugs,” he told me, “you're going to have be accountable to what happens on the receiving end of those narcotics.” Rico Moore, a black lawyer representing a poor white man in West Virginia facing similar charges, told me that the system uses the “same playbook” against poor people of all races. "I think, of course, poor defendants get treated like lesser citizens the same as black defendants,” he said. One case that got a bit of national attention was that of Zachary Hammond, a white teen shot dead by Seneca, South Carolina police as he tried to drive away from a drug sting. Most media attention focused on whether he was getting less media attention because he was white. “If Zachary were black, the outpouring of protest and disappointment from the public and the press would be amazing,” Eric Bland, Hammond's lawyer, protested. “You wouldn’t be able to get a hotel room in upstate South Carolina.” In reality, most of the people tweeting about #ZacharyHammond seem to be Black Lives Matters supporters — including after it was announce that the officer who executed the teen would not be charged. It's not the job of black activists to highlight white victims of mass incarceration and police abuse, though they do. The #alllivesmatter camp, to be sure, was not out marching in the street demanding justice for Zachary Hammond. White privilege and white supremacy are very real. But it's also no wonder that white liberal arts graduates have an easier time understanding white privilege than an out of work white miner or factory worker: it's hard to ruminate about one's race advantage when you're getting hammered on the economic margins. The debates pitting race against class are tired and counterproductive (and to poor black people, perhaps entirely ludicrous). More to the point would be a conversation that makes sense of people's different, difficult realities. You can't do that if you belittle poor white people as rednecks, and succumb to a vision of American politics as a cultural phenomenon reflected on Wolf Blitzer's color-coded election maps. In the late 1960s, Black Panthers in Chicago were building a Rainbow Coalition with Puerto Rican Young Lords and Appalachian migrant Young Patriots to take on poverty, police brutality and Mayor Richard Daley before leader Fred Hampton was murdered by police at the age of 21. "There's...people on welfare up here,” said Black Panther Bobby Lee, in a powerful meeting with militant Appalachians. “There's police brutality up here. There's rats and roaches. There's poverty up here. That's the first thing that we...can unite on." [embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=js7SI... Today, it is prisoners who may be leading us out of the rabbit hole of some of the less productive arguments about race and class. Three years ago in California, alleged leaders of rival race-based gangs—the Aryan Brotherhood, the Black Guerrilla Family, the Mexican Mafia and Nuestra Familia—who had spent years locked inside Pelican Bay State Prison's dystopian solitary confinement unit, organized 30,000 prisoners statewide to go on hunger strike. As Sitawa Jamaa, an alleged leader of the Black Guerrilla Family, put it: "We are a prisoner class now." A failure to recognize the fact that mass incarceration poses a threat to Americans of all races misses an opportunity to build the only sort of broad-based coalition that can bring the system down. It also, if history is any lesson, poses a major risk. Liberal criticism of racial sentencing inequities helped pave the way for the 1984 law that created the sentencing guidelines that, alongside mandatory minimums, have helped drive the federal prison system's explosive growth. Sentences are still disparate. And they are much, much longer. Demands that the criminal justice system solve our problems, and that it treat people equally, could once again result in more brutality across the board. The people goading the federal government into a bloodbath in Oregon should be mindful of this history. Black Lives Matter has cast an unprecedented spotlight on the criminal justice system. A rainbow coalition could learn a lot from the brutality they have illuminated.

January 22, 2016

Can cannabis treat epileptic seizures?

Charlotte Figi, an eight-year-old girl from Colorado with Dravet syndrome, a rare and debilitating form of epilepsy, came into the public eye in 2013 when news broke that medical marijuana was able to do what other drugs could not: dramatically reduce her seizures. Now, new scientific research provides evidence that cannabis may be an effective treatment for a third of epilepsy patients who, like Charlotte, have a treatment-resistant form of the disease. Last month Orrin Devinsky, a neurologist at New York University Langone Medical Center, and his colleagues across multiple research centers published the results from the largest study to date of a cannabis-based drug for treatment-resistant epilepsy in

The Lancet Neurology

. The researchers treated 162 patients with an extract of 99 percent cannabidiol (CBD), a nonpsychoactive chemical in marijuana, and monitored them for 12 weeks. This treatment was given as an add-on to the patients’ existing medications and the trial was open-label (everyone knew what they were getting). The researchers reported the intervention reduced motor seizures at a rate similar to existing drugs (a median of 36.5 percent) and 2 percent of patients became completely seizure free. Additionally, 79 percent of patients reported adverse effects such as sleepiness, diarrhea and fatigue, although only 3 percent dropped out of the study due to adverse events. “I was a little surprised that the overall number of side effects was quite high but it seems like most of them were not enough that the patients had to come off the medication,” says Kevin Chapman, a neurology and pediatric professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine who was not involved in the study. “I think that [this study] provides some good data to show that it's relatively safe—the adverse effects were mostly mild and [although] there were serious adverse effects, it's always hard to know in such a refractory population whether that would have occurred anyway.” Stories of cannabis’s abilities to alleviate seizures have been around for about 150 years but interest in medical marijuana has increased sharply in the last decade with the help of legalization campaigns. In particular, both patients and scientists have started to focus on the potential benefits of CBD, one of the main compounds in cannabis. Unlike tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which is responsible for its euphoric effects, CBD does not cause a “high” or pose the same type of risks that researchers have identified for THC, such as addiction and cognitive impairment. Rather, studies have shown that it can act as an anticonvulsant and may even have antipsychotic effects. The trial led by Devinsky is currently the most robust assessment of CBD’s effect on epilepsy (prior studies included less than 20 patients) but many questions remain. In a subsequent commentary published this January, also in The Lancet Neurology, Kamil Detyniecki and Lawrence Hirsch, neurologists at the Yale University School of Medicine who were not involved in the research, outlined the study’s major limitations, which include possible placebo effects and drug interactions. Because the trial was open-label and without a control group, a main concern is the placebo effect, which previous studies have shown might be especially strong with marijuana-based products. For example, an earlier 2015 study carried out by Chapman and his group at the University of Colorado revealed that 47 percent of patients whose families had moved to Colorado for cannabis-based epilepsy treatment reported improvement, compared with 22 percent in people who already lived there. The other major issue is the possibility of drug interactions—because CBD is a potent liver enzyme inhibitor it can increase the concentration of other drugs in the body. This means that when administered with other compounds, consequent effects on patients may be due to the increased exposure to those other drugs rather than the CBD itself. Despite these limitations, both commentary authors agree the study is an important step in establishing CBD as a safe and effective epilepsy treatment. “This is a first step, and it's great,” Detyniecki says. Despite the large number of adverse events, he says that overall “there were no surprising side effects—we can conclude that CBD appears to be safe in the short term.” Evidence suggesting that CBD is effective against treatment-resistant epilepsy may be growing but scientists still know very little about how it works—other than the likelihood that it is “completely different than any other seizure drug we know,” as Devinsky puts it. That’s a good thing, he notes: “One fear is that because of the way that the drugs are tested and screened, we've ended up with a lot of ‘me-too’ drugs that are all very similar.” Researchers, including those who were involved in the study published last December, hope to address these limitations in currently running blind and placebo-controlled clinical trials testing CBD on Dravetsufferers as well as Lennox–Gastaut syndrome, another drug-resistant form of epilepsy. In the meantime most clinicians and researchers, including those involved in the trial, advise “cautious optimism” when considering CBD as an epilepsy treatment. “I think, based on the evidence that we have, if a child has tried multiple standard drugs and the epilepsy is still severe and impairing quality of life, then the risks of trying CBD are low to modest at best,” Devinksy says. “[But] I do feel it is critical for us as a scientific community to get [more] data.” Cannabis may be the much-needed treatment for a handful of people with epilepsy, but for now, patients should wait for scientists to clear the haze.

Charlotte Figi, an eight-year-old girl from Colorado with Dravet syndrome, a rare and debilitating form of epilepsy, came into the public eye in 2013 when news broke that medical marijuana was able to do what other drugs could not: dramatically reduce her seizures. Now, new scientific research provides evidence that cannabis may be an effective treatment for a third of epilepsy patients who, like Charlotte, have a treatment-resistant form of the disease. Last month Orrin Devinsky, a neurologist at New York University Langone Medical Center, and his colleagues across multiple research centers published the results from the largest study to date of a cannabis-based drug for treatment-resistant epilepsy in

The Lancet Neurology

. The researchers treated 162 patients with an extract of 99 percent cannabidiol (CBD), a nonpsychoactive chemical in marijuana, and monitored them for 12 weeks. This treatment was given as an add-on to the patients’ existing medications and the trial was open-label (everyone knew what they were getting). The researchers reported the intervention reduced motor seizures at a rate similar to existing drugs (a median of 36.5 percent) and 2 percent of patients became completely seizure free. Additionally, 79 percent of patients reported adverse effects such as sleepiness, diarrhea and fatigue, although only 3 percent dropped out of the study due to adverse events. “I was a little surprised that the overall number of side effects was quite high but it seems like most of them were not enough that the patients had to come off the medication,” says Kevin Chapman, a neurology and pediatric professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine who was not involved in the study. “I think that [this study] provides some good data to show that it's relatively safe—the adverse effects were mostly mild and [although] there were serious adverse effects, it's always hard to know in such a refractory population whether that would have occurred anyway.” Stories of cannabis’s abilities to alleviate seizures have been around for about 150 years but interest in medical marijuana has increased sharply in the last decade with the help of legalization campaigns. In particular, both patients and scientists have started to focus on the potential benefits of CBD, one of the main compounds in cannabis. Unlike tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which is responsible for its euphoric effects, CBD does not cause a “high” or pose the same type of risks that researchers have identified for THC, such as addiction and cognitive impairment. Rather, studies have shown that it can act as an anticonvulsant and may even have antipsychotic effects. The trial led by Devinsky is currently the most robust assessment of CBD’s effect on epilepsy (prior studies included less than 20 patients) but many questions remain. In a subsequent commentary published this January, also in The Lancet Neurology, Kamil Detyniecki and Lawrence Hirsch, neurologists at the Yale University School of Medicine who were not involved in the research, outlined the study’s major limitations, which include possible placebo effects and drug interactions. Because the trial was open-label and without a control group, a main concern is the placebo effect, which previous studies have shown might be especially strong with marijuana-based products. For example, an earlier 2015 study carried out by Chapman and his group at the University of Colorado revealed that 47 percent of patients whose families had moved to Colorado for cannabis-based epilepsy treatment reported improvement, compared with 22 percent in people who already lived there. The other major issue is the possibility of drug interactions—because CBD is a potent liver enzyme inhibitor it can increase the concentration of other drugs in the body. This means that when administered with other compounds, consequent effects on patients may be due to the increased exposure to those other drugs rather than the CBD itself. Despite these limitations, both commentary authors agree the study is an important step in establishing CBD as a safe and effective epilepsy treatment. “This is a first step, and it's great,” Detyniecki says. Despite the large number of adverse events, he says that overall “there were no surprising side effects—we can conclude that CBD appears to be safe in the short term.” Evidence suggesting that CBD is effective against treatment-resistant epilepsy may be growing but scientists still know very little about how it works—other than the likelihood that it is “completely different than any other seizure drug we know,” as Devinsky puts it. That’s a good thing, he notes: “One fear is that because of the way that the drugs are tested and screened, we've ended up with a lot of ‘me-too’ drugs that are all very similar.” Researchers, including those who were involved in the study published last December, hope to address these limitations in currently running blind and placebo-controlled clinical trials testing CBD on Dravetsufferers as well as Lennox–Gastaut syndrome, another drug-resistant form of epilepsy. In the meantime most clinicians and researchers, including those involved in the trial, advise “cautious optimism” when considering CBD as an epilepsy treatment. “I think, based on the evidence that we have, if a child has tried multiple standard drugs and the epilepsy is still severe and impairing quality of life, then the risks of trying CBD are low to modest at best,” Devinksy says. “[But] I do feel it is critical for us as a scientific community to get [more] data.” Cannabis may be the much-needed treatment for a handful of people with epilepsy, but for now, patients should wait for scientists to clear the haze.

White Hollywood meltdown: Now Julie Delpy says it’s harder to be a woman than to be black in Hollywood

Pro-life fanatics want you to think abortion clinics are terrifying places; here’s what one really looks like

When I hung up the phone after scheduling my abortion, I felt relieved. I knew I had set in motion the necessary steps that would allow me to make the right decision for myself, my future, my body and my (at the time) partner. I knew I was going to have access to an abortion in a relatively safe environment, administered by trained medical healthcare professionals and in a clean, sterile room. My hand was still holding my phone when I let out a large sigh, confident in my decision and thankful for my ability to make it.

But as my hand slid my phone onto the counter so I could continue to go about my day, I felt the very real chill of panic. While I knew where I was going to have my abortion and how my abortion would be administered, I had no idea what an abortion clinic actually looked like. I had never been inside one before, so my only frame of reference was Hollywood representations and manipulated pro-life paraphernalia. Before I knew it, my mind was bombarded with terrifying images of cold operating rooms and intimidating instruments. I felt like I was going into surgery, that I’d be entering a room that was medical and impersonal and nothing short of terrifying.

If only I had known then what I know now. The moments I spent nervous and uneasy, pacing in my living room with a sense of unnecessary anxiety should have been moments of relaxed confidence. An abortion clinic is not a terrifying place of death, like many pro-life advocates would want women to believe. Shouldn’t an abortion clinic be, not an operating room or even a doctor’s office, but a safe, comfortable and welcoming place that makes women feel at ease with their medical decisions and medical procedures?

Carafem, a clinic that provides abortions in Washington, D.C., believes so, and is taking a new approach to abortion services by offering women a calm, soothing and safe abortion experience. Like most other medical procedures, the patient’s comfort level is taken into consideration on every level -- from the moment the patient enters the clinic until well after she leaves. This makes Carafem a clinic of a different color; that doesn't shy away from advertising not only the services it provides women, but the extra steps they take to endure that women feel comfortable and at ease.

These efforts, made by clinics across the country, are stifled by pro-life advocates. In an attempt to shame women for their decisions and the choices they make with their bodies, pro-life advocates insist that having an abortion shouldn’t be a comfortable experience. No, instead a woman should be afraid and in pain and, essentially, punished (physically, emotionally and mentally) for her decision. Not only is this cruel and unusual, it is vindictive and everything abortion clinics and women’s healthcare clinics work tirelessly to combat and avoid.

Fear and a lack of knowledge are the two unbelievably powerful tools that the anti-choice movement has learned to use almost impeccably. Shielding women from factual information or creating false information to further a particular agenda has continued to perpetuate shame, fear and the kind of anxiety that had me pacing back and forth in my living room after scheduling my appointment.

In fact, even the term “abortion clinic” is an attempt to scare and manipulate women. If you go to a physician to have your gall bladder removed, do you call it a “gall bladder clinic”? For a pap smear, do we go to “pap smear clinics”? Anti-choice advocates have used the description “abortion clinic” as a pejorative, deliberately attempting to use language to subtly tarnish or stigmatize the completely legal medical service, and the providers who offer it.

So, in the spirit of factual transparency and open discourse, I took an inside look at a Carafem clinic and documented what it really is like inside this clinic, that provides not only abortions but contraception information and numerous forms of affordable birth control. With permission of the clinic and while there were no visiting patients, I went through the same steps a woman would go through when visiting the clinic, experiencing everything she would experience (except the at-home medication abortion).

I first walked into a relatively small space that felt less like a waiting room and more like a quiet staging area. There were a grand total of three chairs in the waiting room, and I quickly realized how much I would have appreciated that if I was sitting in one of them, waiting to meet with a healthcare professional and start the process of getting an abortion. The patients don’t feel like a number in a long line and they’re given the space to ensure their privacy is protected.

When sitting in one of the chairs, I looked to my left and noticed small cards that were left behind by women who had sat exactly where I was sitting. I read a few of them and became both emotional and (slightly) jealous. I was emotional because it was such a beautiful gift to give a woman, the knowledge that others have been where she is now and the confidence that she made the right decision for her. I was jealous because I didn’t receive such a gift when I had my own abortion, and it would have done wonders for my mental and emotional health if I had known that I wasn’t alone.

I was then taken into a small room and given a tutorial of sorts, about the abortion pill, what to expect, what to look out for, what kind of birth control options were available to me and what kind of birth control I would be the most successful using. The slide show was given on a large screen, so I could see everything that was being told to me on a screen, while simultaneously looking through pamphlets that highlighted the exact same information. I realized that the clinic and its staff were making sure to present their information in a way that would cover all possible learning styles: visual, auditory, verbal, physical and logical.

I felt respected in my ability to obtain knowledge, I felt acutely listened to and acknowledged and I felt like if I was sitting in that chair, about to get an abortion, I would feel like my choice was being treated like nothing more than a legal medical procedure. Because, after all, that is exactly what it is.

Walking out of that clinic I was both hopeful and sad. I was sad because all I could think about was that scared 22-year-old girl, pacing back and forth in her living room, unsure of what kind of environment she was going to be walking into. I’m sad that I spent so much time afraid and anxious, when I didn’t need to be. I’m sad that I wasn’t privy to the kind of information I have today, and that inability perpetuated an unnecessary fear. I’m sad that there are many women who feel the exact same way -- today, right now -- because they haven’t been able to find the necessary information to feel completely confidence in what they know to be necessary. I’m sad that as I type, there is undoubtably a woman pacing back and forth in her living room, nervous about walking into a clinic that provides abortions, not because she is unsure of her decision, but because she is unsure of what that clinic looks like.

I was hopeful because there is an undeniable and notable cultural shift occurring and information is more available than ever before. I’m hopeful because with knowledge is power, and women are feeling more and more empowered to take unapologetic control of their bodies and the choices they make with them.

And I’m still hopeful that, one day, women will not be asked to feel shame and pain and suffering because they had an abortion, but will be treated with respect, and given more and more options -- and safe, secure and comfortable places -- to make their own reproductive choices.

“Boys for Pele” turns 20: Revisiting the year when Tori Amos truly came into her own

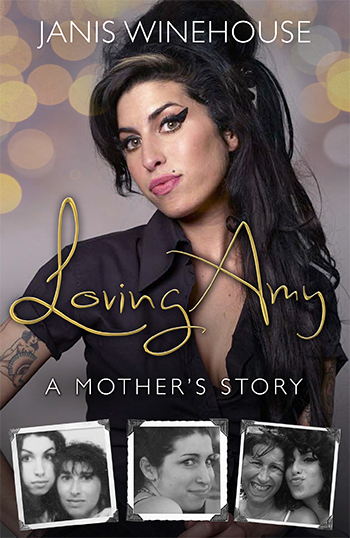

Amy Winehouse’s mom opens up: “I did not expect to lose Amy when I did”

There are times when Amy catches me unawares. She’s right in front of me and in a second I am overwhelmed. This feeling comes with no warning. There is no route map for grief. There are no rules. I can’t predict what might trigger this: her face flashed up on the big screen at the BRIT Awards; a song of hers playing in the airport lounge en route to New York; the Japanese tea set she bought me from a Camden junk shop that I stumble across while sorting through a cupboard at home; the mention of her name. Whether these moments are intensely public or intensely private, they stop me in my tracks, and I am paralysed with emotion. Yet I find them strangely comforting. They are a reminder that I can still feel, that I am not numb. I worry about a day when that might change. I worry about the day when Amy stops being alive in my head and in my heart. I don’t want that day ever to come. I don’t think it ever will. I loved her. I will always love her, and I miss everything about her. Amy, bless her, was larger than life. I find myself saying ‘bless her’ in the same breath as Amy’s name a lot of the time. It’s my way of acknowledging that she was not a straightforward girl. Amy was one of those rare people who made an impact. Right from the very beginning, when she was a toddler, she was loud and boisterous and scared and sensitive. She was a bundle of emotions, at times adorable and at times unbearable. All this is consistent with the struggle she went through to overcome the addictions that eventually robbed her of her life. Amy’s passing did not follow a clear line. It was jumbled, and her life was unfinished – not life’s natural order at all. She left no answers, only questions, and in the years since her death I’ve found myself trying to make sense of the frayed ends of her extraordinary existence. I lost Amy twice: once to drugs and alcohol, and finally on Saturday, 23 July 2011, when her short life ended. I don’t believe any of the endless speculation that Amy wanted to die. There was no doubt that she battled with who she was and what she had become, but she dreamed that one day she’d have children and there was a large part of Amy that had a zest for life and people. But she was a girl who kicked against authority, a person who always took things that bit further than everyone else around her. She used to say to me, ‘Mum, I hate mediocrity. I never want to be mediocre.’ Whatever else Amy was, she was anything but mediocre. She had a phenomenal talent and she pushed it to its limits; she pushed her life to its limits; she pushed her body beyond its limits. In her mind she was invincible, yet she was as vulnerable as any of us are. I have a recurring vision of her, wherever she is, saying to me through that mischievous smile of hers, ‘Oops, Mum, I really didn’t mean to do that. I went too far this time, didn’t I?’ I did not expect to lose Amy when I did. Since the first night I held her in my arms she had always been a constant and close part of my life. But during the worst years of Amy’s drugs dependency there were moments when I truly thought that every time I saw her it would be the last. Amy had become a slave to her drugs and parts of the daughter I’d raised were slowly being wiped away. In the past she’d have gone out of her way to get to me, wherever I was, but as her addictions took hold she became less reliable, less able to organize herself without an army of people clearing a path for her and clearing up after her. She became wildly sentimental and wildly ill-natured. She’d sit in front of me, her short skirt riding up her legs and her sharp bones protruding from her knees. I could see it happening. I could see her tiny body disintegrating, but there was nothing I could do. As her mother, I was completely helpless. I could ring her and I could visit her, but I couldn’t save her. I knew that if I tried to I would lose myself too. For some time, Amy had tried to protect me from the reality of her life. She wanted to keep me as a ‘mummy’ figure, untainted by everything she was experiencing. Amy had looked out for me from a young age, in particular after the breakdown of my marriage to her father Mitchell, and I suspect she didn’t want to upset me. But mothers have a sixth sense and I was busy filling in the blanks. As Amy’s troubles escalated there were certain things that became more and more difficult for her to hide. The ups and downs of those years took their toll on Amy and everyone around her. Loving Amy became a relentless cycle of thinking I would lose her, but not losing her, thinking I would lose her, but not losing her. It was a bit like holding your breath under water and gasping for air every time you reached the surface, then treading water while wondering what the next dive down might involve. Also, by 2006 – the time when Amy’s addictions began to consume her – I had not long been officially diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. I have suffered with the symptoms for more than thirty years, from just after I gave birth to Amy’s older brother Alex, and it is why I now walk with the aid of a stick. Amy’s unpredictability meant I lived constantly on tenterhooks, and my own health had reached crisis point too. I often caught myself thinking, ‘Are all these things really happening to my family?’ But then my own survival instinct kicked in. I have always been a pragmatist, but thinking pragmatically about your own daughter’s addiction is one of the hardest things a mother can do. I worked as a pharmacist until my MS forced me to take early retirement, so my medical background helped me to see Amy’s problems more clearly as an illness. Even armed with that know ledge, however, I desperately struggled to keep myself together. I relied on counselling to make sense of everything that was dis integrating around me. I needed to talk things through with someone who wasn’t emotionally wrapped up in the drama of our lives. Step by step I began to refocus my own life. I took time for myself, and although there were moments when I felt guilty about doing so, I stopped telling myself it was wrong. A new relationship with my now husband Richard, whom I’ve known since I was twelve years old, began to blossom. I am convinced that all those things, combined with my inner resolve, have given me an enormous amount of insight and strength both during Amy’s life and after her passing. Right up until that summer of 2011 I believed she had turned a corner – we all did. She had been clean of drugs for almost three years and we could see glimpses of a future again, even though her life was still punctuated with bouts of heavy drinking. Nevertheless, our expectations had shifted and I felt optimistic about what lay in store for her. Instead of questioning if or when Amy was going to die, I had begun to imagine a time when she would be better. Sadly, that day never came, and I will always feel tortured by a sense of what could have been, even though I have had to accept the reality. Amy came into my life like a whirlwind and changed it forever. Although I lived through it with her, sometimes her story does not feel real. I am a proud mother who watched her daughter achieve the success and recognition she desperately wanted. But soon that private and intense bond between us became public property. Amy’s entire life became public property and I guess, as a family, we were always in tow. Everybody who took an interest in Amy believed they knew her, and everyone wanted a piece of her, in ways we were completely unprepared for. She, herself, walked an endlessly unsteady tightrope between withdrawing from the limelight and needing to be noticed. In that way, Amy and I were different. Throughout her life and even now, the limelight was and is a place in which I feel uneasy. Unlike Mitchell, I struggle with being in the public eye. I have never felt comfortable walking on the red carpet, even though my husband Richard tells me I look as cool as a cucumber. Whether accepting awards on Amy’s behalf or raising money for Amy’s foundation – the charity Mitchell and I set up in the months after her passing – I’ve graced more stages than I ever thought possible. I do everything now with Amy in my heart. And if anything extraordinary happens – and since Amy’s death lots of extraordinary things have happened – I think, ‘Janis, it’s all part of the story.’ I’m just not sure yet whether it’s my story or whether I’m watching the events of my life as if they were someone else’s feature film. So much of what has happened to me and my family has been almost impossible to process. I find myself filing things in a ‘surreal box’ in my mind, to deal with later, just so I can carry on. Telling the story of my life with Amy was first mooted back in 2007 when I was approached by a literary agent and asked whether I would consider writing a book. I wasn’t entirely comfortable with the idea, but I came away from the meeting thinking I might like to, but only when Amy was well again. I called her and asked her what she thought of the proposal. ‘Don’t do it, Mum,’ she told me in no uncertain terms. ‘I don’t want people to know who I am.’ Enough said. Amy was happy to let the beehive and the eyeliner and the car-crash lifestyle become the only side of her the public saw, even though we knew she was a much more complex person than that. Back then, I never considered going against her wishes. Now life has changed. I thought long and hard before finally agreeing to tell our story, but once I made the decision I found that the trepidation I felt at the beginning slowly disappeared. Recalling happy times as well as confronting some uncomfortable truths has helped me in my own journey. It has helped me understand how our ordinary life grew in so many fantastic ways, and self-destructed in so many others. I rediscovered parts of Amy’s life too, the sort of precious memories that fade in the maelstrom of a working mother’s life and get buried by the avalanche of fame and addiction. Over time, memories get eroded, and MS makes that process worse – that loss of sharpness is, regrettably, part of this degenerative condition – so I wanted to put mine on record before they are lost forever. I have read and heard so many false truths about Amy over the years there was also a strong desire to set the record straight. My family and friends, photos and Amy’s own notebooks have all helped me piece our lives back together again. In sorting through the fragments it has struck me how, at various points, Amy’s life closely mirrored aspects of my own in the years before she was born. Physically, Amy has my features. Our school reports are almost identical. We both loved adventure and, in our own ways, we both pushed the boundaries without necessarily thinking of the consequences. I quietly rebelled against a life of domesticity in 1970s and 1980s suburbia. Amy achieved superstardom by rebelling against the manufactured world of pop music. In the end, she rebelled against everything else too, and turned it inwards on herself. Despite the obvious heartbreak, I am uplifted when I am reminded of what Amy achieved – what we achieved. I graduated with two degrees while bringing up Alex and Amy and I wanted to motivate both my children to imagine what it was possible to achieve. Amy grabbed opportunities with both hands and realized her potential early in life. My only hope is that she would approve of this book as a frank account of her life, although I can picture her shrugging her shoulders and saying, ‘Mum, there’s nothing to say about me, honest.’ Today, I wear Amy’s necklace. It’s a gold Star of David that she was given as a baby. I never take it off. I wear her ring too. On some days I even wear her clothes – her T-shirts – and I feel closer to her. As I said, there are no rules for grief. There are days when I feel at peace with Amy and there are nights when I wake up crying. But I try not to dwell on the negative parts of her life, nor on how her death devastated my family. I keep going, as I have always done, busying myself with anything I can. It seems to be the only way I can get through each day. I celebrate Amy’s talent and appreciate the great gift she gave to the world. It will live on well after I and my family have gone. The Amy Winehouse Foundation, too, has already begun to make a difference to the lives of other children who, for whatever reason, are set on a wayward and downward path in life. It means so much to me that all my proceeds from this book will be donated to Amy’s charity. We want to work with many more children in the future and help them realize their potential, and I know Amy is with us every step of the way. I choose not to mourn Amy. I have her albums and a live concert she performed in São Paulo on my iPod. Hers is the only voice that spurs me upstairs and on to my exercise bike to go through the workouts I do to alleviate the discomfort of my MS. I’m not sure I’d get there otherwise. There are moments, though, when I hear the nakedness of her voice and I wonder how much the world under stood of Amy’s vulnerability. She was a singer, a superstar, an addict and a young woman who hurtled towards an untimely death. To me, though, she is simply Amy. She was my daughter and my friend, and she will be with me forever. Excerpted from "LOVING AMY: A Mother’s Story" by Janis Winehouse. Copyright © 2014 by the author and reprinted by permission of Thomas Dunne Books, an imprint of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.

There are times when Amy catches me unawares. She’s right in front of me and in a second I am overwhelmed. This feeling comes with no warning. There is no route map for grief. There are no rules. I can’t predict what might trigger this: her face flashed up on the big screen at the BRIT Awards; a song of hers playing in the airport lounge en route to New York; the Japanese tea set she bought me from a Camden junk shop that I stumble across while sorting through a cupboard at home; the mention of her name. Whether these moments are intensely public or intensely private, they stop me in my tracks, and I am paralysed with emotion. Yet I find them strangely comforting. They are a reminder that I can still feel, that I am not numb. I worry about a day when that might change. I worry about the day when Amy stops being alive in my head and in my heart. I don’t want that day ever to come. I don’t think it ever will. I loved her. I will always love her, and I miss everything about her. Amy, bless her, was larger than life. I find myself saying ‘bless her’ in the same breath as Amy’s name a lot of the time. It’s my way of acknowledging that she was not a straightforward girl. Amy was one of those rare people who made an impact. Right from the very beginning, when she was a toddler, she was loud and boisterous and scared and sensitive. She was a bundle of emotions, at times adorable and at times unbearable. All this is consistent with the struggle she went through to overcome the addictions that eventually robbed her of her life. Amy’s passing did not follow a clear line. It was jumbled, and her life was unfinished – not life’s natural order at all. She left no answers, only questions, and in the years since her death I’ve found myself trying to make sense of the frayed ends of her extraordinary existence. I lost Amy twice: once to drugs and alcohol, and finally on Saturday, 23 July 2011, when her short life ended. I don’t believe any of the endless speculation that Amy wanted to die. There was no doubt that she battled with who she was and what she had become, but she dreamed that one day she’d have children and there was a large part of Amy that had a zest for life and people. But she was a girl who kicked against authority, a person who always took things that bit further than everyone else around her. She used to say to me, ‘Mum, I hate mediocrity. I never want to be mediocre.’ Whatever else Amy was, she was anything but mediocre. She had a phenomenal talent and she pushed it to its limits; she pushed her life to its limits; she pushed her body beyond its limits. In her mind she was invincible, yet she was as vulnerable as any of us are. I have a recurring vision of her, wherever she is, saying to me through that mischievous smile of hers, ‘Oops, Mum, I really didn’t mean to do that. I went too far this time, didn’t I?’ I did not expect to lose Amy when I did. Since the first night I held her in my arms she had always been a constant and close part of my life. But during the worst years of Amy’s drugs dependency there were moments when I truly thought that every time I saw her it would be the last. Amy had become a slave to her drugs and parts of the daughter I’d raised were slowly being wiped away. In the past she’d have gone out of her way to get to me, wherever I was, but as her addictions took hold she became less reliable, less able to organize herself without an army of people clearing a path for her and clearing up after her. She became wildly sentimental and wildly ill-natured. She’d sit in front of me, her short skirt riding up her legs and her sharp bones protruding from her knees. I could see it happening. I could see her tiny body disintegrating, but there was nothing I could do. As her mother, I was completely helpless. I could ring her and I could visit her, but I couldn’t save her. I knew that if I tried to I would lose myself too. For some time, Amy had tried to protect me from the reality of her life. She wanted to keep me as a ‘mummy’ figure, untainted by everything she was experiencing. Amy had looked out for me from a young age, in particular after the breakdown of my marriage to her father Mitchell, and I suspect she didn’t want to upset me. But mothers have a sixth sense and I was busy filling in the blanks. As Amy’s troubles escalated there were certain things that became more and more difficult for her to hide. The ups and downs of those years took their toll on Amy and everyone around her. Loving Amy became a relentless cycle of thinking I would lose her, but not losing her, thinking I would lose her, but not losing her. It was a bit like holding your breath under water and gasping for air every time you reached the surface, then treading water while wondering what the next dive down might involve. Also, by 2006 – the time when Amy’s addictions began to consume her – I had not long been officially diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. I have suffered with the symptoms for more than thirty years, from just after I gave birth to Amy’s older brother Alex, and it is why I now walk with the aid of a stick. Amy’s unpredictability meant I lived constantly on tenterhooks, and my own health had reached crisis point too. I often caught myself thinking, ‘Are all these things really happening to my family?’ But then my own survival instinct kicked in. I have always been a pragmatist, but thinking pragmatically about your own daughter’s addiction is one of the hardest things a mother can do. I worked as a pharmacist until my MS forced me to take early retirement, so my medical background helped me to see Amy’s problems more clearly as an illness. Even armed with that know ledge, however, I desperately struggled to keep myself together. I relied on counselling to make sense of everything that was dis integrating around me. I needed to talk things through with someone who wasn’t emotionally wrapped up in the drama of our lives. Step by step I began to refocus my own life. I took time for myself, and although there were moments when I felt guilty about doing so, I stopped telling myself it was wrong. A new relationship with my now husband Richard, whom I’ve known since I was twelve years old, began to blossom. I am convinced that all those things, combined with my inner resolve, have given me an enormous amount of insight and strength both during Amy’s life and after her passing. Right up until that summer of 2011 I believed she had turned a corner – we all did. She had been clean of drugs for almost three years and we could see glimpses of a future again, even though her life was still punctuated with bouts of heavy drinking. Nevertheless, our expectations had shifted and I felt optimistic about what lay in store for her. Instead of questioning if or when Amy was going to die, I had begun to imagine a time when she would be better. Sadly, that day never came, and I will always feel tortured by a sense of what could have been, even though I have had to accept the reality. Amy came into my life like a whirlwind and changed it forever. Although I lived through it with her, sometimes her story does not feel real. I am a proud mother who watched her daughter achieve the success and recognition she desperately wanted. But soon that private and intense bond between us became public property. Amy’s entire life became public property and I guess, as a family, we were always in tow. Everybody who took an interest in Amy believed they knew her, and everyone wanted a piece of her, in ways we were completely unprepared for. She, herself, walked an endlessly unsteady tightrope between withdrawing from the limelight and needing to be noticed. In that way, Amy and I were different. Throughout her life and even now, the limelight was and is a place in which I feel uneasy. Unlike Mitchell, I struggle with being in the public eye. I have never felt comfortable walking on the red carpet, even though my husband Richard tells me I look as cool as a cucumber. Whether accepting awards on Amy’s behalf or raising money for Amy’s foundation – the charity Mitchell and I set up in the months after her passing – I’ve graced more stages than I ever thought possible. I do everything now with Amy in my heart. And if anything extraordinary happens – and since Amy’s death lots of extraordinary things have happened – I think, ‘Janis, it’s all part of the story.’ I’m just not sure yet whether it’s my story or whether I’m watching the events of my life as if they were someone else’s feature film. So much of what has happened to me and my family has been almost impossible to process. I find myself filing things in a ‘surreal box’ in my mind, to deal with later, just so I can carry on. Telling the story of my life with Amy was first mooted back in 2007 when I was approached by a literary agent and asked whether I would consider writing a book. I wasn’t entirely comfortable with the idea, but I came away from the meeting thinking I might like to, but only when Amy was well again. I called her and asked her what she thought of the proposal. ‘Don’t do it, Mum,’ she told me in no uncertain terms. ‘I don’t want people to know who I am.’ Enough said. Amy was happy to let the beehive and the eyeliner and the car-crash lifestyle become the only side of her the public saw, even though we knew she was a much more complex person than that. Back then, I never considered going against her wishes. Now life has changed. I thought long and hard before finally agreeing to tell our story, but once I made the decision I found that the trepidation I felt at the beginning slowly disappeared. Recalling happy times as well as confronting some uncomfortable truths has helped me in my own journey. It has helped me understand how our ordinary life grew in so many fantastic ways, and self-destructed in so many others. I rediscovered parts of Amy’s life too, the sort of precious memories that fade in the maelstrom of a working mother’s life and get buried by the avalanche of fame and addiction. Over time, memories get eroded, and MS makes that process worse – that loss of sharpness is, regrettably, part of this degenerative condition – so I wanted to put mine on record before they are lost forever. I have read and heard so many false truths about Amy over the years there was also a strong desire to set the record straight. My family and friends, photos and Amy’s own notebooks have all helped me piece our lives back together again. In sorting through the fragments it has struck me how, at various points, Amy’s life closely mirrored aspects of my own in the years before she was born. Physically, Amy has my features. Our school reports are almost identical. We both loved adventure and, in our own ways, we both pushed the boundaries without necessarily thinking of the consequences. I quietly rebelled against a life of domesticity in 1970s and 1980s suburbia. Amy achieved superstardom by rebelling against the manufactured world of pop music. In the end, she rebelled against everything else too, and turned it inwards on herself. Despite the obvious heartbreak, I am uplifted when I am reminded of what Amy achieved – what we achieved. I graduated with two degrees while bringing up Alex and Amy and I wanted to motivate both my children to imagine what it was possible to achieve. Amy grabbed opportunities with both hands and realized her potential early in life. My only hope is that she would approve of this book as a frank account of her life, although I can picture her shrugging her shoulders and saying, ‘Mum, there’s nothing to say about me, honest.’ Today, I wear Amy’s necklace. It’s a gold Star of David that she was given as a baby. I never take it off. I wear her ring too. On some days I even wear her clothes – her T-shirts – and I feel closer to her. As I said, there are no rules for grief. There are days when I feel at peace with Amy and there are nights when I wake up crying. But I try not to dwell on the negative parts of her life, nor on how her death devastated my family. I keep going, as I have always done, busying myself with anything I can. It seems to be the only way I can get through each day. I celebrate Amy’s talent and appreciate the great gift she gave to the world. It will live on well after I and my family have gone. The Amy Winehouse Foundation, too, has already begun to make a difference to the lives of other children who, for whatever reason, are set on a wayward and downward path in life. It means so much to me that all my proceeds from this book will be donated to Amy’s charity. We want to work with many more children in the future and help them realize their potential, and I know Amy is with us every step of the way. I choose not to mourn Amy. I have her albums and a live concert she performed in São Paulo on my iPod. Hers is the only voice that spurs me upstairs and on to my exercise bike to go through the workouts I do to alleviate the discomfort of my MS. I’m not sure I’d get there otherwise. There are moments, though, when I hear the nakedness of her voice and I wonder how much the world under stood of Amy’s vulnerability. She was a singer, a superstar, an addict and a young woman who hurtled towards an untimely death. To me, though, she is simply Amy. She was my daughter and my friend, and she will be with me forever. Excerpted from "LOVING AMY: A Mother’s Story" by Janis Winehouse. Copyright © 2014 by the author and reprinted by permission of Thomas Dunne Books, an imprint of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.

Conservatives in a meltdown: National Review’s confused “Against Trump” issue is an amazing testament to the right’s implosion