Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 843

March 6, 2016

Farewell to my face: I’m middle-aged and I look it — but don’t ask me to like it

A “final girl” who gets to get off: “The Witch” proves nothing’s scarier than an unapologetically liberated young woman

Employers are using credit checks against otherwise qualified workers. Here’s what we can do about it.

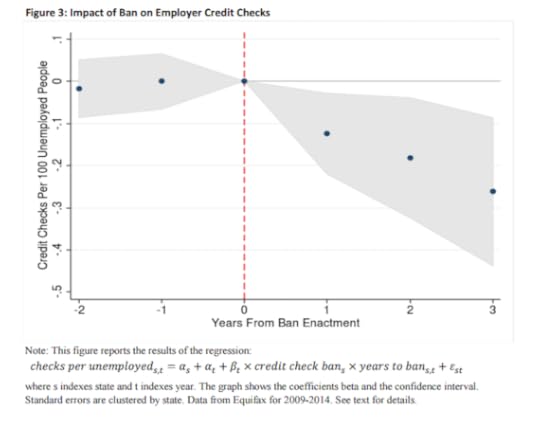

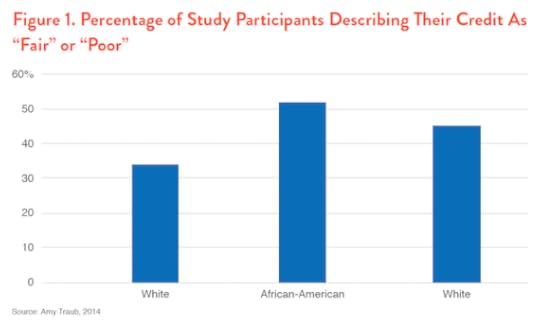

Laws banning credit checks could actually work even better However, in our new Demos report, "Bad Credit Shouldn’t Block Employment: How to Make State Bans on Employment Credit Checks More Effective" we show that while most credit check laws are a key step forward, they can be strengthened in a few ways: Reduce the number of unnecessary exemptions Create robust enforcement mechanisms Increase public awareness of the laws Unnecessary exemptions plague employment credit check bills, as the chart below shows. In Vermont, Helen Head, Chair of the Committee on General, Housing & Military Affairs tells Demos that, “We are concerned that the large number of exceptions may make it more difficult to limit the practice of employer credit checks.” Her concern is well-placed. Legal scholars James Phillips and David Schein note that exemptions have “virtually gutted” the restrictions, because they are often so broad. For instance, seven states allow for credit checks if such information meets the vague standard of being “substantially job related,” and six allow credit checks for positions that involve access to money. These exemptions are unwarranted. TransUnion, a major credit reporting company recently admitted, “we don’t have any research to show any statistical correlation between what’s in somebody’s credit report and their job performance or their likelihood to commit fraud.” In many cases, states were doing very little to enforce the laws, normally because they are required by law to respond to complaints, and receive very few, if any. In Connecticut, after four years there had only been two complaints, and neither were found to have merit. The two complaints Maryland had were both resolved informally (without citations or fines). Oregon provided Demos with data from all cases filed since their law’s passage, which included eight cases, one of which had been settled privately, another withdrawn to court and a final leading to negotiated conciliation. Elizabeth Funk of Colorado’s Department of Labor tells Demos that they had received between 10 and 20 complaints, about half of which had lead to investigations. As of yet, there were no fine levied, but they reported being in the middle of investigations. This is not to fault the government agencies tasked with enforcement - given the wide range of activities they oversee, credit checks are likely to be de-prioritized because there simply aren’t many complaints. Given the deep austerity afflicting state governments, resources are scarce. In addition, credit check laws don’t give the agencies the power to initiate investigations, which means that public awareness is key. But beyond brief press coverage at the passage of the laws and some information on state government websites, there has been very little effort to publicize the laws. New York City shows how to get credit-check laws right In 2015, New York City enacted the most robust employment credit check law on the books. The law was enacted with a diverse coalition including labor, community organizations, civil rights groups, students and consumer groups. While the law still contains exemptions, these are narrower than in many laws in other states. The exemptions were the result of local political compromises and should not be considered a model for future legislation. The law also includes strong penalties - up to $250,000.. In addition, New York City undertook an extensive public awareness campaign, including ads on subways and buses, as well as a social media campaign including the hashtag #CreditCheckLawNYC. The NYC Commission on Human Rights created a webpage clearly explaining the implications of the law. Conclusion: Credit checks are a racially discriminatory and unnecessary qualification for employment. States should implement laws to restrict the practice without unjustified exemptions. New laws should include robust enforcement mechanisms and should be broadly publicized so that workers, job-seekers and employers alike are aware of these important protections.

Laws banning credit checks could actually work even better However, in our new Demos report, "Bad Credit Shouldn’t Block Employment: How to Make State Bans on Employment Credit Checks More Effective" we show that while most credit check laws are a key step forward, they can be strengthened in a few ways: Reduce the number of unnecessary exemptions Create robust enforcement mechanisms Increase public awareness of the laws Unnecessary exemptions plague employment credit check bills, as the chart below shows. In Vermont, Helen Head, Chair of the Committee on General, Housing & Military Affairs tells Demos that, “We are concerned that the large number of exceptions may make it more difficult to limit the practice of employer credit checks.” Her concern is well-placed. Legal scholars James Phillips and David Schein note that exemptions have “virtually gutted” the restrictions, because they are often so broad. For instance, seven states allow for credit checks if such information meets the vague standard of being “substantially job related,” and six allow credit checks for positions that involve access to money. These exemptions are unwarranted. TransUnion, a major credit reporting company recently admitted, “we don’t have any research to show any statistical correlation between what’s in somebody’s credit report and their job performance or their likelihood to commit fraud.” In many cases, states were doing very little to enforce the laws, normally because they are required by law to respond to complaints, and receive very few, if any. In Connecticut, after four years there had only been two complaints, and neither were found to have merit. The two complaints Maryland had were both resolved informally (without citations or fines). Oregon provided Demos with data from all cases filed since their law’s passage, which included eight cases, one of which had been settled privately, another withdrawn to court and a final leading to negotiated conciliation. Elizabeth Funk of Colorado’s Department of Labor tells Demos that they had received between 10 and 20 complaints, about half of which had lead to investigations. As of yet, there were no fine levied, but they reported being in the middle of investigations. This is not to fault the government agencies tasked with enforcement - given the wide range of activities they oversee, credit checks are likely to be de-prioritized because there simply aren’t many complaints. Given the deep austerity afflicting state governments, resources are scarce. In addition, credit check laws don’t give the agencies the power to initiate investigations, which means that public awareness is key. But beyond brief press coverage at the passage of the laws and some information on state government websites, there has been very little effort to publicize the laws. New York City shows how to get credit-check laws right In 2015, New York City enacted the most robust employment credit check law on the books. The law was enacted with a diverse coalition including labor, community organizations, civil rights groups, students and consumer groups. While the law still contains exemptions, these are narrower than in many laws in other states. The exemptions were the result of local political compromises and should not be considered a model for future legislation. The law also includes strong penalties - up to $250,000.. In addition, New York City undertook an extensive public awareness campaign, including ads on subways and buses, as well as a social media campaign including the hashtag #CreditCheckLawNYC. The NYC Commission on Human Rights created a webpage clearly explaining the implications of the law. Conclusion: Credit checks are a racially discriminatory and unnecessary qualification for employment. States should implement laws to restrict the practice without unjustified exemptions. New laws should include robust enforcement mechanisms and should be broadly publicized so that workers, job-seekers and employers alike are aware of these important protections.

Read the full report: "Bad Credit Shouldn’t Block Employment: How to Make State Bans on Employment Credit Checks More Effective."

Read the full report: "Bad Credit Shouldn’t Block Employment: How to Make State Bans on Employment Credit Checks More Effective."

Hillary’s “House of Cards”: What Claire and Frank Underwood tell us about marriage, gender and the White House

“It’s shameless financial strip-mining”: Les Leopold explains how the 1 percent killed the middle class

These are the 20 hardest working cities in America

Americans work a lot. Despite a certain failed GOP presidential contender’s suggestion that we should be putting in more hours at the office, the numbers show we’re already logging plenty. A CNN Money roundup of stats on work habits shows Americans work more than people in other rich countries; that the average working week is actually 47 hours, not 40; and that nearly 40 percent of workers rack up more than 50 working hours each week. Yet our culturally ingrained notions allow for Americans to be constantly asked to work more all the time, without complaint, a system that seems to be holding up nicely. An ABCNews.com poll from 2015 found just 26 percent of Americans say they work too hard. So who’s toiling the hardest among U.S. denizens? The GOP would likely state that those in the heartland are pulling all the weight while coastal elites read the New Yorker, listen to NPR and sip lattes. But WalletHub's look at the labor forces in 116 largest American cities finds the hardest workers are scattered around the country. The assessments are based on a number of factors, including, but not limited to average workweek hours, commute time and number of workers with multiple jobs. I suspect the nature of the work being done, a factor that doesn’t seem to be included, might skew these findings. However subjective work intensity might be, it seems objectively true that eight hours a day of coal-mining or fruit-picking is probably more taxing, in certain critical ways, than eight hours of restaurant reviewing. Not to take potshots or anything. Have a look for yourself at how the top 20 breaks down. To see the full list of 116, visit WalletHub. Anchorage, AK Virginia Beach, VA Plano, TX Sioux Falls, SD Irving, TX Scottsdale, AZ San Francisco, CA Cheyenne, WY Washington, DC Charlotte, NC Gilbert, AZ Corpus Christi, TX Denver, CO Billings, MT Chandler, AZ Jersey City, NJ Chesapeake, VA Garland, TX Oklahoma City, OK Houston, TX (h/t WalletHub)

Americans work a lot. Despite a certain failed GOP presidential contender’s suggestion that we should be putting in more hours at the office, the numbers show we’re already logging plenty. A CNN Money roundup of stats on work habits shows Americans work more than people in other rich countries; that the average working week is actually 47 hours, not 40; and that nearly 40 percent of workers rack up more than 50 working hours each week. Yet our culturally ingrained notions allow for Americans to be constantly asked to work more all the time, without complaint, a system that seems to be holding up nicely. An ABCNews.com poll from 2015 found just 26 percent of Americans say they work too hard. So who’s toiling the hardest among U.S. denizens? The GOP would likely state that those in the heartland are pulling all the weight while coastal elites read the New Yorker, listen to NPR and sip lattes. But WalletHub's look at the labor forces in 116 largest American cities finds the hardest workers are scattered around the country. The assessments are based on a number of factors, including, but not limited to average workweek hours, commute time and number of workers with multiple jobs. I suspect the nature of the work being done, a factor that doesn’t seem to be included, might skew these findings. However subjective work intensity might be, it seems objectively true that eight hours a day of coal-mining or fruit-picking is probably more taxing, in certain critical ways, than eight hours of restaurant reviewing. Not to take potshots or anything. Have a look for yourself at how the top 20 breaks down. To see the full list of 116, visit WalletHub. Anchorage, AK Virginia Beach, VA Plano, TX Sioux Falls, SD Irving, TX Scottsdale, AZ San Francisco, CA Cheyenne, WY Washington, DC Charlotte, NC Gilbert, AZ Corpus Christi, TX Denver, CO Billings, MT Chandler, AZ Jersey City, NJ Chesapeake, VA Garland, TX Oklahoma City, OK Houston, TX (h/t WalletHub)

Former first lady Nancy Reagan dies at 94

March 5, 2016

Cruz, Trump win two states each on Super Saturday; Sanders triumphs in Nebraska and Kansas to stay alive against Clinton

In a split decision, Ted Cruz and Donald Trump each captured two victories in Saturday's four-state round of voting, fresh evidence that there's no quick end in sight to the fractious GOP race for president. On the Democratic side, Bernie Sanders notched wins in Nebraska and Kansas, while front-runner Hillary Clinton snagged Louisiana, another divided verdict from the American people.

Cruz claimed Kansas and Maine, and declared it "a manifestation of a real shift in momentum." Trump, still the front-runner in the hunt for delegates, bagged Louisiana and Kentucky. Despite strong support from the GOP establishment, Florida Sen. Marco Rubio had another disappointing night, raising serious questions about his viability in the race.

Cruz, a tea party favorite, said the results should send a loud message that the GOP contest for the nomination is far from over, and that the status quo is in trouble.

"The scream you hear, the howl that comes from Washington D.C., is utter terror at what we the people are doing together," he declared during a rally in Idaho, which votes in three days.

With the GOP race in chaos, establishment figures frantically are looking for any way to derail Trump, perhaps at a contested convention if no candidate can get enough delegates to lock up the nomination in advance. Party leaders - including 2012 nominee Mitt Romney and 2008 nominee Sen. John McCain - are fearful a Trump victory would lead to a disastrous November election, with losses up and down the GOP ticket.

"Everyone's trying to figure out how to stop Trump," the billionaire marveled at an afternoon rally in Orlando, Florida, where he had supporters raise their hands and swear to vote for him.

Trump prevailed in the home state of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.

Rubio, who finished no better than third anywhere and has only one win so far, insisted the upcoming schedule of primaries is "better for us," and renewed his vow to win his home state of Florida, claiming all 99 delegates there on March 15.

But Cruz suggested it was time for Rubio and Ohio Gov. John Kasich to go.

"As long as the field remains divided, it gives Donald an advantage," he said.

Campaigning in Detroit, Clinton said she was thrilled to add to her delegate count and expected to do well in Michigan's primary on Tuesday.

"No matter who wins this Democratic nomination," she said, "I have not the slightest doubt that on our worst day we will be infinitely better than the Republicans on their best day."

Tara Evans, a 52-year-old quilt maker from Bellevue, Nebraska, said she was caucusing for Clinton, and happy to know that the former first lady could bring her husband back to the White House.

"I like Bernie, but I think Hillary had the best chance of winning," she said.

Sanders won by solid margins in Nebraska and Kansas, giving him seven victories so far in the nominating season, compared to 11 for Clinton, who still maintains a commanding lead in competition for delegates.

Sanders, in an interview with The Associated Press, pointed to his wide margins of victory and called it evidence that his political revolution is coming to pass.

Stressing the important of voter turnout, he said, "when large numbers of people come - working people, young people who have not been involved in the political process - we will do well and I think that is bearing out tonight."

With Republican front-runner Trump yet to win states by the margins he'll need in order to secure the nomination before the GOP convention, every one of the 155 GOP delegates at stake on Saturday was worth fighting for.

Count Wichita's Barb Berry among those who propelled Cruz to victory in Kansas, where GOP officials reported extremely high turnout. Overall, Cruz has won seven states so far, to 12 for Trump.

"I believe that he is a true fighter for conservatives," said Berry, a 67-year-old retired AT&T manager. As for Trump, Berry said, "he is a little too narcissistic."

Like Rubio, Kasich has pinned his hopes on the winner-take-all contest March 15 in his home state.

Clinton picked up at least 51 delegates to Sanders' 45 in Saturday's contests, with delegates yet to be allocated.

Overall, Clinton had at least 1,117 delegates to Sanders' 477, including superdelegates - members of Congress, governors and party officials who can support the candidate of their choice. It takes 2,383 delegates to win the Democratic nomination.

Cruz will collect at least 36 delegates for winning the Republican caucuses in Kansas and Maine, Trump at least 18 and Rubio at least six and Kasich three.

In the overall race for GOP delegates, Trump led with at least 347 and Cruz had at least 267. Rubio had 116 delegates and Kasich had 28.

It takes 1,237 delegates to win the Republican nomination for president.

In a split decision, Ted Cruz and Donald Trump each captured two victories in Saturday's four-state round of voting, fresh evidence that there's no quick end in sight to the fractious GOP race for president. On the Democratic side, Bernie Sanders notched wins in Nebraska and Kansas, while front-runner Hillary Clinton snagged Louisiana, another divided verdict from the American people.

Cruz claimed Kansas and Maine, and declared it "a manifestation of a real shift in momentum." Trump, still the front-runner in the hunt for delegates, bagged Louisiana and Kentucky. Despite strong support from the GOP establishment, Florida Sen. Marco Rubio had another disappointing night, raising serious questions about his viability in the race.

Cruz, a tea party favorite, said the results should send a loud message that the GOP contest for the nomination is far from over, and that the status quo is in trouble.

"The scream you hear, the howl that comes from Washington D.C., is utter terror at what we the people are doing together," he declared during a rally in Idaho, which votes in three days.

With the GOP race in chaos, establishment figures frantically are looking for any way to derail Trump, perhaps at a contested convention if no candidate can get enough delegates to lock up the nomination in advance. Party leaders - including 2012 nominee Mitt Romney and 2008 nominee Sen. John McCain - are fearful a Trump victory would lead to a disastrous November election, with losses up and down the GOP ticket.

"Everyone's trying to figure out how to stop Trump," the billionaire marveled at an afternoon rally in Orlando, Florida, where he had supporters raise their hands and swear to vote for him.

Trump prevailed in the home state of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.

Rubio, who finished no better than third anywhere and has only one win so far, insisted the upcoming schedule of primaries is "better for us," and renewed his vow to win his home state of Florida, claiming all 99 delegates there on March 15.

But Cruz suggested it was time for Rubio and Ohio Gov. John Kasich to go.

"As long as the field remains divided, it gives Donald an advantage," he said.

Campaigning in Detroit, Clinton said she was thrilled to add to her delegate count and expected to do well in Michigan's primary on Tuesday.

"No matter who wins this Democratic nomination," she said, "I have not the slightest doubt that on our worst day we will be infinitely better than the Republicans on their best day."

Tara Evans, a 52-year-old quilt maker from Bellevue, Nebraska, said she was caucusing for Clinton, and happy to know that the former first lady could bring her husband back to the White House.

"I like Bernie, but I think Hillary had the best chance of winning," she said.

Sanders won by solid margins in Nebraska and Kansas, giving him seven victories so far in the nominating season, compared to 11 for Clinton, who still maintains a commanding lead in competition for delegates.

Sanders, in an interview with The Associated Press, pointed to his wide margins of victory and called it evidence that his political revolution is coming to pass.

Stressing the important of voter turnout, he said, "when large numbers of people come - working people, young people who have not been involved in the political process - we will do well and I think that is bearing out tonight."

With Republican front-runner Trump yet to win states by the margins he'll need in order to secure the nomination before the GOP convention, every one of the 155 GOP delegates at stake on Saturday was worth fighting for.

Count Wichita's Barb Berry among those who propelled Cruz to victory in Kansas, where GOP officials reported extremely high turnout. Overall, Cruz has won seven states so far, to 12 for Trump.

"I believe that he is a true fighter for conservatives," said Berry, a 67-year-old retired AT&T manager. As for Trump, Berry said, "he is a little too narcissistic."

Like Rubio, Kasich has pinned his hopes on the winner-take-all contest March 15 in his home state.

Clinton picked up at least 51 delegates to Sanders' 45 in Saturday's contests, with delegates yet to be allocated.

Overall, Clinton had at least 1,117 delegates to Sanders' 477, including superdelegates - members of Congress, governors and party officials who can support the candidate of their choice. It takes 2,383 delegates to win the Democratic nomination.

Cruz will collect at least 36 delegates for winning the Republican caucuses in Kansas and Maine, Trump at least 18 and Rubio at least six and Kasich three.

In the overall race for GOP delegates, Trump led with at least 347 and Cruz had at least 267. Rubio had 116 delegates and Kasich had 28.

It takes 1,237 delegates to win the Republican nomination for president.

In a split decision, Ted Cruz and Donald Trump each captured two victories in Saturday's four-state round of voting, fresh evidence that there's no quick end in sight to the fractious GOP race for president. On the Democratic side, Bernie Sanders notched wins in Nebraska and Kansas, while front-runner Hillary Clinton snagged Louisiana, another divided verdict from the American people.

Cruz claimed Kansas and Maine, and declared it "a manifestation of a real shift in momentum." Trump, still the front-runner in the hunt for delegates, bagged Louisiana and Kentucky. Despite strong support from the GOP establishment, Florida Sen. Marco Rubio had another disappointing night, raising serious questions about his viability in the race.

Cruz, a tea party favorite, said the results should send a loud message that the GOP contest for the nomination is far from over, and that the status quo is in trouble.

"The scream you hear, the howl that comes from Washington D.C., is utter terror at what we the people are doing together," he declared during a rally in Idaho, which votes in three days.

With the GOP race in chaos, establishment figures frantically are looking for any way to derail Trump, perhaps at a contested convention if no candidate can get enough delegates to lock up the nomination in advance. Party leaders - including 2012 nominee Mitt Romney and 2008 nominee Sen. John McCain - are fearful a Trump victory would lead to a disastrous November election, with losses up and down the GOP ticket.

"Everyone's trying to figure out how to stop Trump," the billionaire marveled at an afternoon rally in Orlando, Florida, where he had supporters raise their hands and swear to vote for him.

Trump prevailed in the home state of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.

Rubio, who finished no better than third anywhere and has only one win so far, insisted the upcoming schedule of primaries is "better for us," and renewed his vow to win his home state of Florida, claiming all 99 delegates there on March 15.

But Cruz suggested it was time for Rubio and Ohio Gov. John Kasich to go.

"As long as the field remains divided, it gives Donald an advantage," he said.

Campaigning in Detroit, Clinton said she was thrilled to add to her delegate count and expected to do well in Michigan's primary on Tuesday.

"No matter who wins this Democratic nomination," she said, "I have not the slightest doubt that on our worst day we will be infinitely better than the Republicans on their best day."

Tara Evans, a 52-year-old quilt maker from Bellevue, Nebraska, said she was caucusing for Clinton, and happy to know that the former first lady could bring her husband back to the White House.

"I like Bernie, but I think Hillary had the best chance of winning," she said.

Sanders won by solid margins in Nebraska and Kansas, giving him seven victories so far in the nominating season, compared to 11 for Clinton, who still maintains a commanding lead in competition for delegates.

Sanders, in an interview with The Associated Press, pointed to his wide margins of victory and called it evidence that his political revolution is coming to pass.

Stressing the important of voter turnout, he said, "when large numbers of people come - working people, young people who have not been involved in the political process - we will do well and I think that is bearing out tonight."

With Republican front-runner Trump yet to win states by the margins he'll need in order to secure the nomination before the GOP convention, every one of the 155 GOP delegates at stake on Saturday was worth fighting for.

Count Wichita's Barb Berry among those who propelled Cruz to victory in Kansas, where GOP officials reported extremely high turnout. Overall, Cruz has won seven states so far, to 12 for Trump.

"I believe that he is a true fighter for conservatives," said Berry, a 67-year-old retired AT&T manager. As for Trump, Berry said, "he is a little too narcissistic."

Like Rubio, Kasich has pinned his hopes on the winner-take-all contest March 15 in his home state.

Clinton picked up at least 51 delegates to Sanders' 45 in Saturday's contests, with delegates yet to be allocated.

Overall, Clinton had at least 1,117 delegates to Sanders' 477, including superdelegates - members of Congress, governors and party officials who can support the candidate of their choice. It takes 2,383 delegates to win the Democratic nomination.

Cruz will collect at least 36 delegates for winning the Republican caucuses in Kansas and Maine, Trump at least 18 and Rubio at least six and Kasich three.

In the overall race for GOP delegates, Trump led with at least 347 and Cruz had at least 267. Rubio had 116 delegates and Kasich had 28.

It takes 1,237 delegates to win the Republican nomination for president.

In a split decision, Ted Cruz and Donald Trump each captured two victories in Saturday's four-state round of voting, fresh evidence that there's no quick end in sight to the fractious GOP race for president. On the Democratic side, Bernie Sanders notched wins in Nebraska and Kansas, while front-runner Hillary Clinton snagged Louisiana, another divided verdict from the American people.

Cruz claimed Kansas and Maine, and declared it "a manifestation of a real shift in momentum." Trump, still the front-runner in the hunt for delegates, bagged Louisiana and Kentucky. Despite strong support from the GOP establishment, Florida Sen. Marco Rubio had another disappointing night, raising serious questions about his viability in the race.

Cruz, a tea party favorite, said the results should send a loud message that the GOP contest for the nomination is far from over, and that the status quo is in trouble.

"The scream you hear, the howl that comes from Washington D.C., is utter terror at what we the people are doing together," he declared during a rally in Idaho, which votes in three days.

With the GOP race in chaos, establishment figures frantically are looking for any way to derail Trump, perhaps at a contested convention if no candidate can get enough delegates to lock up the nomination in advance. Party leaders - including 2012 nominee Mitt Romney and 2008 nominee Sen. John McCain - are fearful a Trump victory would lead to a disastrous November election, with losses up and down the GOP ticket.

"Everyone's trying to figure out how to stop Trump," the billionaire marveled at an afternoon rally in Orlando, Florida, where he had supporters raise their hands and swear to vote for him.

Trump prevailed in the home state of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.

Rubio, who finished no better than third anywhere and has only one win so far, insisted the upcoming schedule of primaries is "better for us," and renewed his vow to win his home state of Florida, claiming all 99 delegates there on March 15.

But Cruz suggested it was time for Rubio and Ohio Gov. John Kasich to go.

"As long as the field remains divided, it gives Donald an advantage," he said.

Campaigning in Detroit, Clinton said she was thrilled to add to her delegate count and expected to do well in Michigan's primary on Tuesday.

"No matter who wins this Democratic nomination," she said, "I have not the slightest doubt that on our worst day we will be infinitely better than the Republicans on their best day."

Tara Evans, a 52-year-old quilt maker from Bellevue, Nebraska, said she was caucusing for Clinton, and happy to know that the former first lady could bring her husband back to the White House.

"I like Bernie, but I think Hillary had the best chance of winning," she said.

Sanders won by solid margins in Nebraska and Kansas, giving him seven victories so far in the nominating season, compared to 11 for Clinton, who still maintains a commanding lead in competition for delegates.

Sanders, in an interview with The Associated Press, pointed to his wide margins of victory and called it evidence that his political revolution is coming to pass.

Stressing the important of voter turnout, he said, "when large numbers of people come - working people, young people who have not been involved in the political process - we will do well and I think that is bearing out tonight."

With Republican front-runner Trump yet to win states by the margins he'll need in order to secure the nomination before the GOP convention, every one of the 155 GOP delegates at stake on Saturday was worth fighting for.

Count Wichita's Barb Berry among those who propelled Cruz to victory in Kansas, where GOP officials reported extremely high turnout. Overall, Cruz has won seven states so far, to 12 for Trump.

"I believe that he is a true fighter for conservatives," said Berry, a 67-year-old retired AT&T manager. As for Trump, Berry said, "he is a little too narcissistic."

Like Rubio, Kasich has pinned his hopes on the winner-take-all contest March 15 in his home state.

Clinton picked up at least 51 delegates to Sanders' 45 in Saturday's contests, with delegates yet to be allocated.

Overall, Clinton had at least 1,117 delegates to Sanders' 477, including superdelegates - members of Congress, governors and party officials who can support the candidate of their choice. It takes 2,383 delegates to win the Democratic nomination.

Cruz will collect at least 36 delegates for winning the Republican caucuses in Kansas and Maine, Trump at least 18 and Rubio at least six and Kasich three.

In the overall race for GOP delegates, Trump led with at least 347 and Cruz had at least 267. Rubio had 116 delegates and Kasich had 28.

It takes 1,237 delegates to win the Republican nomination for president.

We’re not meant to do this alone: American individualism is destroying our families

Like many Americans, I'm raising my children far from family. My father is only an hour away, but the rest of us are spread wide across America: my mother in Texas; my sister in Oklahoma; my brother in New York City; my in-laws in Buffalo. Babysitters and after-school programs and summer camps are the village that helps me get the business of life done, and while having more family around would certainly help with the grind, what I miss most is simply time spent with them. The spontaneity of coffee with my mom, how fun it would be for the kids to see a movie with their cousins, enjoying a family barbecue on the weekend.

Nine years ago my husband got a job offer in San Francisco, and without a second thought we left New York City. We loaded the U-Haul covered wagon and did what Americans have been doing since Europeans came to this continent: we said goodbye to loved ones and headed west into the great unknown, forging a future for ourselves alone. Today, it is an American rite of passage to leave your family for college, leave your college for a job, and so on and so on, until opportunities abound but you need Sprint's Unlimited Plan to feel connected to blood. America's modern Manifest Destiny is no longer about physically expanding the boundaries of the continent, it is about self-expansionism.

If you remember high school history at all, Manifest Destiny was the mid-19th-century American belief that settlers were destined to expand throughout the continent, and it was characterized by the virtues of the American people, their mission to remake the West and their destiny to fulfill this duty.

What I find so astounding is that Manifest Destiny is not history at all. It is alive and well, a continued belief pervasive in families everywhere. If John Winthrop's "City Upon a Hill" sermon in 1630 called for this young nation to be an example to the Old World, then it only makes sense that almost 400 years later we look to ourselves to be an example to our parents, to take what they gave us and be even better, to remake our past and achieve individual success. We believe it to be our destiny, just as that job offer in San Francisco was my husband's destiny. It was an essential duty we needed to accomplish for our family, but after almost a decade, one house, two kids, starting a new company, and facing a glowing future, I wonder if there wasn't a way we could have done it differently. To somehow have circled the family wagons, keeping out the savage solitude of this brave new suburban frontier together.

Ironically, it was just this circle of family togetherness from which I was trying to escape as a young adult. Savage solitude was exactly what I was looking for, especially if it would help me write poetry like Sylvia Plath or Anne Sexton. Fleeing what I felt to be the suffocation of Texas and a pattern of the expected -- staying in-state with familiar faces and family close by -- I went to college in upstate New York. I wanted to prove to myself that I could succeed in a wild survival experiment of rigorous academics, mountains of snow and thousands of students. I did not chose a small, intimate, familial institution. I chose a university with almost 20,000 undergrad and grad students. Usually, students create a new “family” in college, a broad social safety net of really good friends, but I did not. Family was overrated. My parents had recently combusted in a hellish fireball of divorce; my sister escaped to college, and my brother was left to survive middle school with a shitload of shrapnel. I had a couple of great friends, but mainly I turned to bad therapists and carbs.

Four years and a diploma later (individual success!), I was ready to continue my self-expansion and conquer New York City. If there’s one place in today’s America that represents the wild, untamed West of the 19th century, this is it -- not necessarily cowboys and Indians, but rather the naked cowboy in Times Square and an Indian cab driver. It was the next step in my survival experiment -- not just to live and work in New York City, but like Sinatra sang, to really make it there. No way in hell would I suffer a forced relocation in a trail of tears (and credit card debt) back to Texas and my family.

Because at this point, I still couldn’t comprehend the full value of family. My work in a big publishing house gave me a paycheck, but it was also fun and vibrant and socially fulfilling. Outside of work, I valued my solitude and sought out connection when I needed it. I called my mom every Sunday, I loved visiting family, but did I miss them? Not really.

No. I couldn’t comprehend the value of family until I had my own, eight years later and 2,905 miles away in San Francisco. I thought I was so prepared to have a child, but raising a baby is perhaps the greatest exploration of all boundaries. The true frontier -- and my destiny, as I saw it. When my husband’s paternity leave ended after two weeks, I sat there on that couch, feeding and burping the baby and not moving until my husband came home 11 hours later. I lived alone for almost a decade, but I never actually felt alone until I had children. And this, for many, is the stay-at-home mother’s plight. Especially the stay-at-home mother who has no family nearby.

America’s cultural glorification of individualism and freedom do not prepare women for the intense need for family after giving birth. We prepare our babies with the softest swaddling cloths, organic diapers and the perfect nursery, but we are not encouraged to anticipate our own needs, especially that of simple connection with others. I equated my own crushing loneliness, my dependency on my husband and phone calls with my mother -- or any adult who listened kindly, for that matter -- to be weakness. Like any good fool with Finnish blood, I stoically buckled under exhaustion, isolation and the anxiety of being a new mother, by myself. I’m ashamed to say that for the first 10 months of my son’s life, I did nothing for myself: no exercise; no dinners out with my husband; no time to myself; no sleep. Why? Because individual success, man! This was the continent I'd timed my ovulation cycle to conquer!

The false assumption that I could parent alone is not just mine. It is societal. In Sebastian Junger’s Vanity Fair piece entitled “PTSD: The War Disorder that Goes Far Beyond the Battlefield,” he talks about the extreme isolationism in America and how soldiers suffer when they come home because they have lost their community. I have never been more profoundly affected by or able to relate to something. Why do people become firemen? Policemen? Join the Coast Guard? There are a lot of reasons, but the simple answer is that being together makes people happy. Combine that with sacrifice for the survival of the group and you get oxytocin. It’s a brain reward system uniquely connected to our evolution. For the rest of us schmucks following the Simon & Garfunkel “I Am an Island” philosophy, Junger says, “personal gain almost completely eclipses collective good.”

All I know is that in the trenches of motherhood, I don’t want to battle alone. And what a shock it was for me to discover that.

My boys are now ages 7 and 4 and my loneliness is both more manageable and more painful at the same time. The kids are in school, I stay active, I have lots of friends, but we are all spinning in different orbits: different carpools, different extracurriculars, different schools, endless errands, endless driving. With no family and only hard-fought playdates or drinks together, the isolation is profound. I miss my friends, who are right next door or down the street, and with each passing year, I miss my family, the missing limb whose phantom pain only increases.

The vast array of choices that make us and our children more successful, more educated, more athletic, is like being at a Thanksgiving table that’s too long: here I am with a goddamn cornucopia of awesomeness, but I can’t see anyone! Yell once if you’re behind the “Guide to 5,000 Essential Summer Camps For Kids”! When I complain, my mom regales me with stories of living on the University of Petroleum and Minerals compound in Saudi Arabia: nothing to do but get together with her 10 neighbors who all had infants the same age as me and do playdates, family meals, and a nanny-share system that gave each woman some alone time. She says it was one of the happiest times in her life.

In my town, just north of San Francisco, transplants from all over America greatly outnumber the native San Franciscans. Missing our families is a common complaint. On the mother’s club forum, we ponder leaving the great jobs and amazing weather for the comfort of a close-knit family, weighing the pros and cons in lengthy debates. We have achieved personal and professional success, we are exceptional employees and exceptional parents. A few hundred years ago, the heart of American exceptionalism was, of course, that we were different than other nations. We were free from the historical forces that impacted other countries, but today, all we are is exceptionally lonely, the Isolated States of America. We are untethered by historical forces all right, free from mom's hugs, dad's homemade chili, and the pillars of extended family.

Talking to my Hispanic dental hygienist over a garbled spew of spearmint tooth polish about my lack of blood-related village, "exceptional" was not the word she used to describe the way white America lives, it was "strange." She explained, "We all live close together and watch each other's kids and cook for each other. I mean, it's crazy but we're together, you know?" Yes, I know. This is true of all my family's international friends, from those in France who live within a 15-mile radius of each other, to those in Saudi Arabia, who live in a family compound by the dozens.

Families are together in the Middle East, Latin America, Europe, Africa and Asia -- all of over the world, except in America, where the premium is not placed on proximity. It's as if Americans must always be Lewis and Clark on a brave embarkation, and if we're not, we are provincial, frightened and uneducated. Unlike our ancestors, young people today are not concerned with America's place in the world. Instead, we ask ourselves, "What is my place in the world?"

We grow up with the belief that self-expansionism -- high school, college, career -- means pushing boundaries toward accomplishment and away from family. So off we go and hey, there's always FaceTime!

What Americans fail to recognize about global family patterns is that children, should they have the means and ability, are encouraged to leave the nest, to seek education outside their homeland, perhaps even to find a life partner, and then -- then! -- to return to their extended family. Living a life near family does not mean sacrificing a life of exploration, travel and learning. Whereas Americans have perfected the art of the rocket, projecting themselves on lonely journeys, the rest of the world practices the boomerang, recognizing the value of leaving and returning.

Manifest Destiny was a contested concept in the 1800s because people didn't feel it reflected the national spirit, and I don't think its modern equivalent is doing us any favors either. The gain of personal enfranchisement doesn't seem to justify a detached form of living.

I don't need to study the research on how a lack of community affects the individual. I am that research. Now if only I could figure out how to turn this rocket around.

The devil’s bargain: Washington is full of people who have prospered thanks to 9/11 — and I was one of them