Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 840

March 9, 2016

The Marco Rubio post-mortem: How a supposedly ready-made GOP nominee crashed and burned

Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears. I come not to praise Marco Rubio – dear God, never, ever that – but to bury him. And then to salt the earth in the hope that he will never come back. The Rubio campaign is on its last legs, stumbling dehydrated and desperate through the Florida Everglades like the heroine in the second act of a Carl Hiaasen novel, trying to stay one step ahead of the bloodhounds who want nothing more than to drag the Florida senator into the swamp and tear his throat out, or at least convince him to join with Ted Cruz on some sort of unity ticket to stop Donald Trump, which might be an even worse fate. The establishment is telling Rubio his dropping out would be for the good of the Republican Party. Which is why he’ll probably at least consider it. He is a party man through and through, and since he gave up his Senate seat to run for president, he’s going to want to come out of this cluster-screw of a campaign with something to show for it besides the humiliation of a crushing defeat in his home state’s primary on Tuesday. Run for vice-president on a ticket with Cruz, the party will whisper in his ear, and when he gets destroyed in the general election in the fall and the country suffers through four years of socialism under a Democrat, you’ll be perfectly positioned to be the 2020 nominee. What’s not to like about that scenario? And why wouldn’t you trust a GOP establishment that has displayed such a sharp political acumen this cycle that it just about handed its nomination over to a jar of orange marmalade in a bad wig before it knew what hit it? Rubio might not be smart, but he’s a politician who can read poll numbers. It must have sunk in by now that his “Baghdad Bob” primary strategy (claim victory even when you came in a distant third/the American military is a block away and roaring towards you unopposed) has been a galactic failure. With even his financial backers and editorial page cheerleaders telling him it’s time, he must feel like Butch Coolidge getting the order to take his ass down in the fifth. The post-mortem on Rubio’s campaign will point to many, many moments that sealed his fate. The base never fully trusted him after his role in the Gang of Eight immigration reform bill in the Senate, which he later had to renounce in the hope of pacifying the conservative mouth-breathers who were inundating his office with hate mail. There was his apparent circuit-breaker malfunction in the New Hampshire debate against Chris Christie. There was his late-in-the-campaign attempt to turn into Don Rickles in order to stand up to Trump, which only seemed to cause his poll numbers to crash. There were his ham-handed attempts to get to the farthest right edge of the Republican field on every issue from abortion to fighting terrorism, the latter of which resulted in his spouting the sorts of fearful, doom-laden paranoia about ISIS terrorists coming ashore in Biscayne Bay that might tickle the GOP base but erased Rubio’s image as the sunny and optimistic young man who could lead America into a booming future. It is that last one that I think comes closest to explaining his flameout. It stems from the 30,000-feet view of Marco Rubio the politician, an ambitious young man with no accomplishments or real-world experience to qualify him, who would don whatever suit – neocon hawk, religious extremist, crazy guy hollering about a war on Christianity from a steam grate – he or his advisers thought the GOP electorate wanted at any given moment, no matter how awkward the fit. He was the best example of a blow-dried establishment candidate this cycle, so perfect he might have been grown in that space station lab in “Alien: Resurrection” where they kept all those malformed Ripley clones, and raised to be the great hope of the Republican Party. In an era where carefully maintaining and presenting a focus group-approved persona to the world is the paramount goal of almost every politician at the national level, Rubio still stood out for how many of his edges had been sanded off. Rubio was the product of personal ambition in overdrive and married to a Republican Party that has bought so fully into the idea that our current president was elected despite being an unaccomplished lightweight, all it had to do was roll out another young, telegenic pol with a non-WASPy last name and the White House would be the GOP’s to lose. Never mind the lack of accomplishments, or the fact he was a career politician who had barely seen a time in his adult life when he wasn’t collecting a government paycheck while dining with lobbyists. Never mind that when he spoke in debates, his talking points, which were mostly warmed-over standard-issue conservative pabulum, all sounded so memorized that you could half-imagine him cramming with flash cards the night before in a dorm room decorated with a Dan Marino poster. Never mind the awkward attempts to connect with young people – did you know that Marco loves the rap music? – while spouting anti-abortion and anti-gay marriage positions that are as out of place in the twenty-first century as a horse and buggy. It would have been much more hilarious, if it hadn’t also felt so desperate. Rubio and his handlers seemed to think he could cruise to the nomination on the strength of an appeal that was as chimerical as a unicorn. To that end, he never really built much of a ground game for his campaign, a fact that observers have been harping on for months. His team seemed to think that it was running some sort of high-tech, futuristic operation where retail politics didn’t matter, where you could, as one adviser infamously put it, save on office rent by having your entire team set up in a Starbucks and use the free wifi. Meanwhile, he seemed to spend as much time huddling with wealthy financial backers behind closed doors as he did getting in front of voters. And while he was flying around being not quite as visible as he needed to be to voters, Rubio missed so much time at his day job, and publicly proclaimed he didn’t care because the Senate bored him anyway, that it became easy to view him as a lazy, entitled dilettante. No amount of repeating the story of his humble beginnings – did you know his dad was a bartender? – was going to overcome that. It’s possible he could still come back and run for statewide office in Florida, but one has to think Rubio’s career in national politics is over. Whatever has been loosed in the electorate that gave rise to Donald Trump is not likely to fade anytime soon. There is no room in that space for a guy so transparent, if you squint hard enough you can see what he ate for lunch. All the image consultants in the world can’t cover that up.Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears. I come not to praise Marco Rubio – dear God, never, ever that – but to bury him. And then to salt the earth in the hope that he will never come back. The Rubio campaign is on its last legs, stumbling dehydrated and desperate through the Florida Everglades like the heroine in the second act of a Carl Hiaasen novel, trying to stay one step ahead of the bloodhounds who want nothing more than to drag the Florida senator into the swamp and tear his throat out, or at least convince him to join with Ted Cruz on some sort of unity ticket to stop Donald Trump, which might be an even worse fate. The establishment is telling Rubio his dropping out would be for the good of the Republican Party. Which is why he’ll probably at least consider it. He is a party man through and through, and since he gave up his Senate seat to run for president, he’s going to want to come out of this cluster-screw of a campaign with something to show for it besides the humiliation of a crushing defeat in his home state’s primary on Tuesday. Run for vice-president on a ticket with Cruz, the party will whisper in his ear, and when he gets destroyed in the general election in the fall and the country suffers through four years of socialism under a Democrat, you’ll be perfectly positioned to be the 2020 nominee. What’s not to like about that scenario? And why wouldn’t you trust a GOP establishment that has displayed such a sharp political acumen this cycle that it just about handed its nomination over to a jar of orange marmalade in a bad wig before it knew what hit it? Rubio might not be smart, but he’s a politician who can read poll numbers. It must have sunk in by now that his “Baghdad Bob” primary strategy (claim victory even when you came in a distant third/the American military is a block away and roaring towards you unopposed) has been a galactic failure. With even his financial backers and editorial page cheerleaders telling him it’s time, he must feel like Butch Coolidge getting the order to take his ass down in the fifth. The post-mortem on Rubio’s campaign will point to many, many moments that sealed his fate. The base never fully trusted him after his role in the Gang of Eight immigration reform bill in the Senate, which he later had to renounce in the hope of pacifying the conservative mouth-breathers who were inundating his office with hate mail. There was his apparent circuit-breaker malfunction in the New Hampshire debate against Chris Christie. There was his late-in-the-campaign attempt to turn into Don Rickles in order to stand up to Trump, which only seemed to cause his poll numbers to crash. There were his ham-handed attempts to get to the farthest right edge of the Republican field on every issue from abortion to fighting terrorism, the latter of which resulted in his spouting the sorts of fearful, doom-laden paranoia about ISIS terrorists coming ashore in Biscayne Bay that might tickle the GOP base but erased Rubio’s image as the sunny and optimistic young man who could lead America into a booming future. It is that last one that I think comes closest to explaining his flameout. It stems from the 30,000-feet view of Marco Rubio the politician, an ambitious young man with no accomplishments or real-world experience to qualify him, who would don whatever suit – neocon hawk, religious extremist, crazy guy hollering about a war on Christianity from a steam grate – he or his advisers thought the GOP electorate wanted at any given moment, no matter how awkward the fit. He was the best example of a blow-dried establishment candidate this cycle, so perfect he might have been grown in that space station lab in “Alien: Resurrection” where they kept all those malformed Ripley clones, and raised to be the great hope of the Republican Party. In an era where carefully maintaining and presenting a focus group-approved persona to the world is the paramount goal of almost every politician at the national level, Rubio still stood out for how many of his edges had been sanded off. Rubio was the product of personal ambition in overdrive and married to a Republican Party that has bought so fully into the idea that our current president was elected despite being an unaccomplished lightweight, all it had to do was roll out another young, telegenic pol with a non-WASPy last name and the White House would be the GOP’s to lose. Never mind the lack of accomplishments, or the fact he was a career politician who had barely seen a time in his adult life when he wasn’t collecting a government paycheck while dining with lobbyists. Never mind that when he spoke in debates, his talking points, which were mostly warmed-over standard-issue conservative pabulum, all sounded so memorized that you could half-imagine him cramming with flash cards the night before in a dorm room decorated with a Dan Marino poster. Never mind the awkward attempts to connect with young people – did you know that Marco loves the rap music? – while spouting anti-abortion and anti-gay marriage positions that are as out of place in the twenty-first century as a horse and buggy. It would have been much more hilarious, if it hadn’t also felt so desperate. Rubio and his handlers seemed to think he could cruise to the nomination on the strength of an appeal that was as chimerical as a unicorn. To that end, he never really built much of a ground game for his campaign, a fact that observers have been harping on for months. His team seemed to think that it was running some sort of high-tech, futuristic operation where retail politics didn’t matter, where you could, as one adviser infamously put it, save on office rent by having your entire team set up in a Starbucks and use the free wifi. Meanwhile, he seemed to spend as much time huddling with wealthy financial backers behind closed doors as he did getting in front of voters. And while he was flying around being not quite as visible as he needed to be to voters, Rubio missed so much time at his day job, and publicly proclaimed he didn’t care because the Senate bored him anyway, that it became easy to view him as a lazy, entitled dilettante. No amount of repeating the story of his humble beginnings – did you know his dad was a bartender? – was going to overcome that. It’s possible he could still come back and run for statewide office in Florida, but one has to think Rubio’s career in national politics is over. Whatever has been loosed in the electorate that gave rise to Donald Trump is not likely to fade anytime soon. There is no room in that space for a guy so transparent, if you squint hard enough you can see what he ate for lunch. All the image consultants in the world can’t cover that up.

Published on March 09, 2016 16:57

“I’m feeling my way through the dark”: Grant-Lee Phillips on writing songs as a reflection of life

Grant-Lee Phillips' songwriting has always been distinguished by two things: its immense curiosity, and an intense yearning for connection. The musician has often used a historical backdrop to try to make sense of the past, present and future, or crafted ornate travelogues where the endgame is trying to conquer—or at least illuminate—the restlessness inherent in those who are always searching for life's elusive answers. Wrestling with the romance of emotional and physical displacement is what made the four albums Phillips released with '90s band Grant Lee Buffalo so appealing and enduring, and it's part of what's made his subsequent solo career so compelling. In fact, the Nashville-via-California singer-songwriter's forthcoming new album, "The Narrows," might be his most accomplished work yet. Recorded at Dan Auerbach’s studio, the LP is both immediate-sounding and intimate: Standout "Smoke and Sparks" boasts fluid, gamboling acoustic guitars and shaded piano, while "Loaded Gun" is hot-rodding honky-tonk and "San Andreas Fault" is gentle, pedal steel-varnished folk. Another highlight, the whispering roots-rocker "No Mercy in July," features evocative bass from one-time Johnny Cash collaborator Dave Roe. Back in February, before the Cleveland stop of his co-headlining tour with fellow singer-songwriter Steve Poltz, Phillips discussed how his move to Nashville and father's death influenced "The Narrows," as well as how his creative process has changed and evolved through the years. (And, of course, he also discussed reprising his role as the town troubadour on "Gilmore Girls.") How has it been being in the Nashville music community? What has it been like for you as a musician? It's been really inspiring. I recorded this new album in Nashville. Jerry Roe, the drummer, he grew up there: His grandfather was Jerry Reed, so he basically grew up around all of these country legends. He's a hard-hitting drummer. I had met him before moving out there, and he was the one who really introduced me to the team put together to make the record. [But] yeah, I'm still meeting folks. There are so many different songwriters and people who live outside of that country mainstream, who are really adventurous musicians. It's great. I find it really inspiring. Have you done any songwriting for other artists yet? I know a lot of people do that. The town is really big on co-writing and all that. Most of my efforts have remained on developing this album in particular. From time to time, I have found myself in one of those little rooms writing with other people. A guy named Graham Colton, who's actually from Oklahoma, he came to town and we did some writing together. And then my friend Donavon Frankenreiter covered that song on his new album. I wrote with Donavon for his record, too. I'm not necessarily plugged in to that same world. My focus is really all on putting out my own records and touring. But I'm open to it—I'm curious about it, how a guy like me fits into that kind of thing. It strikes me as being somewhat regimented. Songwriting works that way sometimes, but not always. You've said that the through-lines and themes for your records tend to reveal themselves organically. After "The Narrows" was completed, what did you discover? What were the themes that stood out to you? Like a lot of my songs, it's about navigating tough waters. Trying to keep your head above the water, and keeping the shore in sight. A lot of these songs are like that. They are moving away from one thing and towards the next, and maybe that destination is unknown at the time, but I'm still moving forward towards it. I'm feeling my way through the dark. Life is that way, and writing is like a reflection of that. I left California after being there for all of my life, so that was a big one. It meant uprooting and going through the whole physical exhaustion of that choice. But it also represented some new adventure. [But] my family—my parents—they were still in California. And no sooner did I arrive in Nashville, maybe a month later or so, my dad—who had suffered bad health for a long time—his health plummeted, and he passed away in the latter part of 2013. That was also something that weighed heavily on my mind, something that I was processing at the same time. The record opens up with "Tennessee Rain," it's kind of me looking towards something hopeful. Somewhere near the end, you hear a song like "San Andreas Fault," which is sort of my violent farewell to the place that I was born in. [Laughs.] It's a road record in that way. It's not exactly a "Road to Bali"—or "Easy Rider"—but it's my kind of travelogue. I did notice that the songs used a sense of place or location—and what that means and how that influences people—maybe more prominently than some of your recent records. I'm frequently moved by the new places that I see. Even with Grant Lee Buffalo, when we first went out on the road, we were driving across Texas for a few days, I wrote "Lone Star Song." A lot of it I trace back to when I was a kid, and I used to travel around with my grandma. My grandma, she would get a wild hair that we had to travel, and my parents would let me go off with her. She'd take me to Montana and Utah, all across that part of the country. My grandpa drove a big rig, so I would travel with him too. I developed that sense of romance for travel, and it does turn up in the songs from time to time. In this case, it's literally rooted in leaving California and moving to the Southeast. You worked with drummer Jerry Roe and multi-instrumentalist Lex Price on the record. How did they influence the way the song on "The Narrows" unfolded when you went to record them? They brought great sensitivity to the songs. They're able to give it some muscle when that's what it called for, and able to step back and just let the song be, as well, let the guitar and the voice be the centerpiece. That's kind of where I begin when I sit down to write, and actually how I perform so much these days. I tour solo acoustically so much, that has become my real baseline. I wouldn't say it's my comfort zone, because it's also a place where there's room to screw it up as well. But there's nothing to hide behind, in other words. And I have increasingly been drawn to that kind of record-making, where there's less and less between me and the song and the end result. That sensitivity—and that sense of knowing when enough was enough. [Laughs.] And making that basic performance be the thing we were after. A little sprinkling, here and there, of overdubs. But not so much that I would've been prone to in the old days. You get in the studio, and it's so easy to be like, "One more thing!" Knowing when to stop is such a gift, and such a talent. It's true. And you can really build yourself a house of cards where, "C'mon, one more card. One more paper-thin wafer!" [Laughs.] It's quite easy for it to topple over, when someone else begins to take it all in. I'm learning about that more and more as I go, the whole "less is more" thing. Jerry Roe's dad, Dave, who played bass with Johnny Cash, played on "No Mercy in July." Did you pump him for information? Did he have any good Johnny Cash stories? Talk about historic. [Laughs.] I was delicate, but yeah, I would love to know some of what he has to convey. We chatted a bit, as I was getting my guitar set up—I played a few licks from "Wreck of the Old 97," just to let him know that I knew that lick. I don't know why. [Laughs.] That was a cool thing: He came in some months after our basic session. It was a cool thing to see Jerry and his dad, Dave, interact and perform on the same track together. And I love the idea of having that energy. My dad, his passing had a great deal to do with how this record turned out. I like the idea of having that energy [of] a father and a son playing on the album. Did your dad's passing have a direct or indirect influence on "The Narrows"? How did it influence what you did? My mom's from Oklahoma, my dad was from Arkansas. Although I was born in California, if you ever visit Stockton, which is very rural, you'll find the people there are a lot like those you would find in Oklahoma or Arkansas, because so many of them made that move in the '40s, '30s. When I went to Nashville, I felt very at home. There's something very familial about it. And, musically speaking, all of that stuff that they listened to affected me when I was growing up. And so part of me has been on that continual quest to find the core of what my musical loves are, where the real raw nerve is, in terms of my inspiration. I like a lot of different types of music, but in some ways that dual desire to be in a place that felt at home—[and] where there was that musical legacy I was connected to—I felt like both of those things were fused in that move to Nashville. As I look back, my desire to create the kind of music I do is some kind of yearning to have a connection with family as well. One could say, "Well, why don't you just stay in the town you grew up with, and have that literal connection?" The fact is, that wasn't in my cards. I had to go out into the world and find my voice this other way. I knew that from a very early age. I don't know: In some ways, I suppose music is a way of trying to stitch up a situation. [Laughs.] It's a hard thing to articulate. But your question was, how did it impact the writing? My dad was sick for a long time. He was suffering from emphysema and other things. The man had to carry around an oxygen tank for the last 10, 15 years. And so it was kind of like you saw death coming like a slow-moving train, you know? I wasn't altogether shocked, [but] when that moment comes, it's still something you can't really prepare yourself for. Some of the songs I had begun to write in anticipation. Like that song "Moccasin Creek," my dad was alive when I was still writing that song. And the idea behind it is kind of trying to go to that place where your ancestors have come from, your family, your grandfathers, grandmothers. But I never played it for him when he was still alive. I recorded it after he had passed. It takes on a deeper meaning in that light. Trying to touch that solid ground that connects you to where you came from. It's a bit like my interest in my ancestry, my Native American ancestry. Same thing. That's what you said in the bio for the record, that you are back in the land of your ancestors, and there's as lot of inspiration there as well. It's true. I mean, the name Grant Lee Buffalo is sort of a hint to my preoccupation with this subject matter. And there were songs that I wrote that may have not got as much attention back when I was with Grant Lee Buffalo that were also touching upon some of these same things that I revisit from time to time—native history and mythology. For me, it's all the same pursuit, trying to understand where we're going as a people, and what I come from as an individual. All of it. And music is such a good indicator of that. We don't really have a lot of recorded music—there are people who have recorded traditional music, but in general, songs tell you so much more about a civilization at a particular point in time than the history books would. They give you a glimpse into the subtext, some other kind of truth about a time. That's what always keeps me interested in listening to records, time and time again. They reveal different things and you find different nuances, and at different times in your life, you resonate with things differently. It's a continual search. Yeah, it is. That's the thing I love about what I do: I can be presented with new challenges in terms of how I go about it, how I write a song. That always happens. Every time I finish writing one record and I begin to make another one, I ask myself, "How did I do that? How do I do that again?" It's like someone goes through and changes all the locks, and you have to find a new way inside the building. [Laughs.] You gotta climb through the window, or through the crawlspace. There's a way, but you have to find some kind of new inroad to get yourself inspired. And that's where it begins. Grant Lee Buffalo's "Copperopolis" turns 20 years old this year, which blew my mind a little bit. Wow. Right? Looking back now, with 20 years of hindsight, what are your thoughts on the songs on that record? Now and then I run into people that tell me that's one of their favorite albums, if not their very favorite. That was an album we really fretted over. I know personally I did, as far as the writing. It wasn't an easy time, you know, to kind of figure out what we were supposed to do next, and [we were] really trying to be as adventurous as we could allow ourselves to be. There are a few songs on that I have rediscovered, like "Arousing Thunder." That is one I seem to play more and more. I haven't gone back and listened to those early albums very much. Only when Grant Lee Buffalo went back out on the road and did a few reunion dates did I sit down and try to learn the songs again, because they had grown new limbs and branches as I played them by myself. It's a strange sensation to listen to my voice from 20 years ago. It's like I'm listening to a wax cylinder or some sort of angry elf. I can't really relate to it in the same way. I don't know what happens, if we get different chemicals in our brains at a certain point, but I feel like I've got a different brain, in some ways. It feels more conscious, believe it or not. Maybe the writing process becomes a little more aware. It doesn't feel like one of those dreams where the steering wheel isn't working. That's how it was a lot when I was younger. I love that sensation, and maybe it's something that maybe it's a different way of approaching it that you only get when you're a younger writer. I like being able to sit with a song and not force it, and know the rest of it will arrive eventually—or it won't. and if it doesn't, then I move on. There was a lot of anxiety that came with the creation of those early albums, the fear that this would be both the first and the last outing. I've got over that anxiety, and that's a really good feeling, to be able to enjoy this process. Or at least enjoy knowing it will, at some point, be done. [Laughs.] I would have to imagine that in the '90s when you were writing songs, there was that whole other layer of major label pressure. The industry was so different. Just being in that pressure cooker environment seems like it would be a nightmare for creativity. You're right—it probably had its pros and cons. I suppose if I would've waited a bit longer then maybe I would've put out a different record at a given time. Or maybe we would've made other choices. What kind of happens is, you got one album when your debut comes out, and then you go out and play it and play it to death onstage. A lot of routine can settle in. That's when it gets tough; that's when it seems like that creative machine gets very gunked up, when you're doing the same thing over and over again. I was always fighting against that, but we had to do a lot of that kind of stuff, playing the same songs. You feel a little trapped in this thing of your own making. And you try to get a handle on it, like, "What is this band about?" Almost as soon as you've got a handle on it, it's become something else, because it's an entity as well. I don't know—it's kind of like when a crowd of people decides to rush for a fire escape. Bands sort of do the same thing, behave in ways that maybe the individuals wouldn't normally do, but as a group we do this other thing. [Laughs.] It's strange. I feel like there's a psychological term for that. It's not exactly groupthink. That is the great thing about a band: Everybody kind of stands back from it and beholds this phenomenon, like, "Look at what we can do! Each of us with our index finger pointed can lift a human off the ground! We can lift the Titanic off the ground if we all concentrate!" It really is amazing in that way. And I think we had a real magic with Grant Lee Buffalo when we came together with that intention. It was flashing before us so quickly that I don't think we could always take it in [or] enjoy it in the way that I wish we could've. I like this pace of things here in the passenger seat of a Chevy Impala with Steve Poltz, down by the river in Cleveland, stopping at a Cracker Barrel now and then. [Laughs.] It's a nice pace. There's something very civil about it.Grant-Lee Phillips' songwriting has always been distinguished by two things: its immense curiosity, and an intense yearning for connection. The musician has often used a historical backdrop to try to make sense of the past, present and future, or crafted ornate travelogues where the endgame is trying to conquer—or at least illuminate—the restlessness inherent in those who are always searching for life's elusive answers. Wrestling with the romance of emotional and physical displacement is what made the four albums Phillips released with '90s band Grant Lee Buffalo so appealing and enduring, and it's part of what's made his subsequent solo career so compelling. In fact, the Nashville-via-California singer-songwriter's forthcoming new album, "The Narrows," might be his most accomplished work yet. Recorded at Dan Auerbach’s studio, the LP is both immediate-sounding and intimate: Standout "Smoke and Sparks" boasts fluid, gamboling acoustic guitars and shaded piano, while "Loaded Gun" is hot-rodding honky-tonk and "San Andreas Fault" is gentle, pedal steel-varnished folk. Another highlight, the whispering roots-rocker "No Mercy in July," features evocative bass from one-time Johnny Cash collaborator Dave Roe. Back in February, before the Cleveland stop of his co-headlining tour with fellow singer-songwriter Steve Poltz, Phillips discussed how his move to Nashville and father's death influenced "The Narrows," as well as how his creative process has changed and evolved through the years. (And, of course, he also discussed reprising his role as the town troubadour on "Gilmore Girls.") How has it been being in the Nashville music community? What has it been like for you as a musician? It's been really inspiring. I recorded this new album in Nashville. Jerry Roe, the drummer, he grew up there: His grandfather was Jerry Reed, so he basically grew up around all of these country legends. He's a hard-hitting drummer. I had met him before moving out there, and he was the one who really introduced me to the team put together to make the record. [But] yeah, I'm still meeting folks. There are so many different songwriters and people who live outside of that country mainstream, who are really adventurous musicians. It's great. I find it really inspiring. Have you done any songwriting for other artists yet? I know a lot of people do that. The town is really big on co-writing and all that. Most of my efforts have remained on developing this album in particular. From time to time, I have found myself in one of those little rooms writing with other people. A guy named Graham Colton, who's actually from Oklahoma, he came to town and we did some writing together. And then my friend Donavon Frankenreiter covered that song on his new album. I wrote with Donavon for his record, too. I'm not necessarily plugged in to that same world. My focus is really all on putting out my own records and touring. But I'm open to it—I'm curious about it, how a guy like me fits into that kind of thing. It strikes me as being somewhat regimented. Songwriting works that way sometimes, but not always. You've said that the through-lines and themes for your records tend to reveal themselves organically. After "The Narrows" was completed, what did you discover? What were the themes that stood out to you? Like a lot of my songs, it's about navigating tough waters. Trying to keep your head above the water, and keeping the shore in sight. A lot of these songs are like that. They are moving away from one thing and towards the next, and maybe that destination is unknown at the time, but I'm still moving forward towards it. I'm feeling my way through the dark. Life is that way, and writing is like a reflection of that. I left California after being there for all of my life, so that was a big one. It meant uprooting and going through the whole physical exhaustion of that choice. But it also represented some new adventure. [But] my family—my parents—they were still in California. And no sooner did I arrive in Nashville, maybe a month later or so, my dad—who had suffered bad health for a long time—his health plummeted, and he passed away in the latter part of 2013. That was also something that weighed heavily on my mind, something that I was processing at the same time. The record opens up with "Tennessee Rain," it's kind of me looking towards something hopeful. Somewhere near the end, you hear a song like "San Andreas Fault," which is sort of my violent farewell to the place that I was born in. [Laughs.] It's a road record in that way. It's not exactly a "Road to Bali"—or "Easy Rider"—but it's my kind of travelogue. I did notice that the songs used a sense of place or location—and what that means and how that influences people—maybe more prominently than some of your recent records. I'm frequently moved by the new places that I see. Even with Grant Lee Buffalo, when we first went out on the road, we were driving across Texas for a few days, I wrote "Lone Star Song." A lot of it I trace back to when I was a kid, and I used to travel around with my grandma. My grandma, she would get a wild hair that we had to travel, and my parents would let me go off with her. She'd take me to Montana and Utah, all across that part of the country. My grandpa drove a big rig, so I would travel with him too. I developed that sense of romance for travel, and it does turn up in the songs from time to time. In this case, it's literally rooted in leaving California and moving to the Southeast. You worked with drummer Jerry Roe and multi-instrumentalist Lex Price on the record. How did they influence the way the song on "The Narrows" unfolded when you went to record them? They brought great sensitivity to the songs. They're able to give it some muscle when that's what it called for, and able to step back and just let the song be, as well, let the guitar and the voice be the centerpiece. That's kind of where I begin when I sit down to write, and actually how I perform so much these days. I tour solo acoustically so much, that has become my real baseline. I wouldn't say it's my comfort zone, because it's also a place where there's room to screw it up as well. But there's nothing to hide behind, in other words. And I have increasingly been drawn to that kind of record-making, where there's less and less between me and the song and the end result. That sensitivity—and that sense of knowing when enough was enough. [Laughs.] And making that basic performance be the thing we were after. A little sprinkling, here and there, of overdubs. But not so much that I would've been prone to in the old days. You get in the studio, and it's so easy to be like, "One more thing!" Knowing when to stop is such a gift, and such a talent. It's true. And you can really build yourself a house of cards where, "C'mon, one more card. One more paper-thin wafer!" [Laughs.] It's quite easy for it to topple over, when someone else begins to take it all in. I'm learning about that more and more as I go, the whole "less is more" thing. Jerry Roe's dad, Dave, who played bass with Johnny Cash, played on "No Mercy in July." Did you pump him for information? Did he have any good Johnny Cash stories? Talk about historic. [Laughs.] I was delicate, but yeah, I would love to know some of what he has to convey. We chatted a bit, as I was getting my guitar set up—I played a few licks from "Wreck of the Old 97," just to let him know that I knew that lick. I don't know why. [Laughs.] That was a cool thing: He came in some months after our basic session. It was a cool thing to see Jerry and his dad, Dave, interact and perform on the same track together. And I love the idea of having that energy. My dad, his passing had a great deal to do with how this record turned out. I like the idea of having that energy [of] a father and a son playing on the album. Did your dad's passing have a direct or indirect influence on "The Narrows"? How did it influence what you did? My mom's from Oklahoma, my dad was from Arkansas. Although I was born in California, if you ever visit Stockton, which is very rural, you'll find the people there are a lot like those you would find in Oklahoma or Arkansas, because so many of them made that move in the '40s, '30s. When I went to Nashville, I felt very at home. There's something very familial about it. And, musically speaking, all of that stuff that they listened to affected me when I was growing up. And so part of me has been on that continual quest to find the core of what my musical loves are, where the real raw nerve is, in terms of my inspiration. I like a lot of different types of music, but in some ways that dual desire to be in a place that felt at home—[and] where there was that musical legacy I was connected to—I felt like both of those things were fused in that move to Nashville. As I look back, my desire to create the kind of music I do is some kind of yearning to have a connection with family as well. One could say, "Well, why don't you just stay in the town you grew up with, and have that literal connection?" The fact is, that wasn't in my cards. I had to go out into the world and find my voice this other way. I knew that from a very early age. I don't know: In some ways, I suppose music is a way of trying to stitch up a situation. [Laughs.] It's a hard thing to articulate. But your question was, how did it impact the writing? My dad was sick for a long time. He was suffering from emphysema and other things. The man had to carry around an oxygen tank for the last 10, 15 years. And so it was kind of like you saw death coming like a slow-moving train, you know? I wasn't altogether shocked, [but] when that moment comes, it's still something you can't really prepare yourself for. Some of the songs I had begun to write in anticipation. Like that song "Moccasin Creek," my dad was alive when I was still writing that song. And the idea behind it is kind of trying to go to that place where your ancestors have come from, your family, your grandfathers, grandmothers. But I never played it for him when he was still alive. I recorded it after he had passed. It takes on a deeper meaning in that light. Trying to touch that solid ground that connects you to where you came from. It's a bit like my interest in my ancestry, my Native American ancestry. Same thing. That's what you said in the bio for the record, that you are back in the land of your ancestors, and there's as lot of inspiration there as well. It's true. I mean, the name Grant Lee Buffalo is sort of a hint to my preoccupation with this subject matter. And there were songs that I wrote that may have not got as much attention back when I was with Grant Lee Buffalo that were also touching upon some of these same things that I revisit from time to time—native history and mythology. For me, it's all the same pursuit, trying to understand where we're going as a people, and what I come from as an individual. All of it. And music is such a good indicator of that. We don't really have a lot of recorded music—there are people who have recorded traditional music, but in general, songs tell you so much more about a civilization at a particular point in time than the history books would. They give you a glimpse into the subtext, some other kind of truth about a time. That's what always keeps me interested in listening to records, time and time again. They reveal different things and you find different nuances, and at different times in your life, you resonate with things differently. It's a continual search. Yeah, it is. That's the thing I love about what I do: I can be presented with new challenges in terms of how I go about it, how I write a song. That always happens. Every time I finish writing one record and I begin to make another one, I ask myself, "How did I do that? How do I do that again?" It's like someone goes through and changes all the locks, and you have to find a new way inside the building. [Laughs.] You gotta climb through the window, or through the crawlspace. There's a way, but you have to find some kind of new inroad to get yourself inspired. And that's where it begins. Grant Lee Buffalo's "Copperopolis" turns 20 years old this year, which blew my mind a little bit. Wow. Right? Looking back now, with 20 years of hindsight, what are your thoughts on the songs on that record? Now and then I run into people that tell me that's one of their favorite albums, if not their very favorite. That was an album we really fretted over. I know personally I did, as far as the writing. It wasn't an easy time, you know, to kind of figure out what we were supposed to do next, and [we were] really trying to be as adventurous as we could allow ourselves to be. There are a few songs on that I have rediscovered, like "Arousing Thunder." That is one I seem to play more and more. I haven't gone back and listened to those early albums very much. Only when Grant Lee Buffalo went back out on the road and did a few reunion dates did I sit down and try to learn the songs again, because they had grown new limbs and branches as I played them by myself. It's a strange sensation to listen to my voice from 20 years ago. It's like I'm listening to a wax cylinder or some sort of angry elf. I can't really relate to it in the same way. I don't know what happens, if we get different chemicals in our brains at a certain point, but I feel like I've got a different brain, in some ways. It feels more conscious, believe it or not. Maybe the writing process becomes a little more aware. It doesn't feel like one of those dreams where the steering wheel isn't working. That's how it was a lot when I was younger. I love that sensation, and maybe it's something that maybe it's a different way of approaching it that you only get when you're a younger writer. I like being able to sit with a song and not force it, and know the rest of it will arrive eventually—or it won't. and if it doesn't, then I move on. There was a lot of anxiety that came with the creation of those early albums, the fear that this would be both the first and the last outing. I've got over that anxiety, and that's a really good feeling, to be able to enjoy this process. Or at least enjoy knowing it will, at some point, be done. [Laughs.] I would have to imagine that in the '90s when you were writing songs, there was that whole other layer of major label pressure. The industry was so different. Just being in that pressure cooker environment seems like it would be a nightmare for creativity. You're right—it probably had its pros and cons. I suppose if I would've waited a bit longer then maybe I would've put out a different record at a given time. Or maybe we would've made other choices. What kind of happens is, you got one album when your debut comes out, and then you go out and play it and play it to death onstage. A lot of routine can settle in. That's when it gets tough; that's when it seems like that creative machine gets very gunked up, when you're doing the same thing over and over again. I was always fighting against that, but we had to do a lot of that kind of stuff, playing the same songs. You feel a little trapped in this thing of your own making. And you try to get a handle on it, like, "What is this band about?" Almost as soon as you've got a handle on it, it's become something else, because it's an entity as well. I don't know—it's kind of like when a crowd of people decides to rush for a fire escape. Bands sort of do the same thing, behave in ways that maybe the individuals wouldn't normally do, but as a group we do this other thing. [Laughs.] It's strange. I feel like there's a psychological term for that. It's not exactly groupthink. That is the great thing about a band: Everybody kind of stands back from it and beholds this phenomenon, like, "Look at what we can do! Each of us with our index finger pointed can lift a human off the ground! We can lift the Titanic off the ground if we all concentrate!" It really is amazing in that way. And I think we had a real magic with Grant Lee Buffalo when we came together with that intention. It was flashing before us so quickly that I don't think we could always take it in [or] enjoy it in the way that I wish we could've. I like this pace of things here in the passenger seat of a Chevy Impala with Steve Poltz, down by the river in Cleveland, stopping at a Cracker Barrel now and then. [Laughs.] It's a nice pace. There's something very civil about it.

Published on March 09, 2016 16:00

The N-word, in terrible context: Period pieces “Hap and Leonard” and “Underground” expose the long roots of racism

It is—or it should be—extremely startling to hear a white person use the N-word in 2016. Weirdly, this month on television, there are a lot of opportunities to hear just that. Last night, for example, on “The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story,” F. Lee Bailey (Nathan Lane) asked Mark Fuhrman (Steven Pasquale) if he’s ever used the slur, and in asking says the word, dispassionately, six separate times. But, of course, that scene comes from the real-life incident where Bailey asked Fuhrman those questions from the staid chambers of a courtroom in 1995, broadcast nationally to audiences everywhere. Sitcoms from “All in the Family” to “Black-ish” have devoted space to exploring the impact of the word, and network dramas have found a way to incorporate the slur into their own Very Special Episodes, as Josh Kurp details. But the preponderance of uncensored cable television has ushered in a new era of televisual profanity, and though shows like “Oz” and “The Wire” have gone whole-hog with every kind of insult, slur and derogatory phrase, there is something different about the language in two new cable shows: “Hap and Leonard,” on SundanceTV, and “Underground,” on WGN. Both shows are period pieces in the South, though of very different eras. “Underground,” which debuts tonight, takes place in plantation-era Georgia, and most of the characters are enslaved. “Hap and Leonard,” which debuted last week, takes place in East Texas in the ‘80s, at the height of the Reagan administration. And in both, the black leads are pointedly subject to racist language, including copious use of the N-word. It’s not pleasant, but it goes a ways toward exposing the long roots of racism in America. That a few assholes in the ‘80s would be fine with throwing the word around while pointing a gun at Leonard (Michael K. Williams) is perhaps not surprising. But watching the look on Leonard’s face as the scene unspools is surprising; the typically brash, shit-talking drifter is stunned into a self-preserving silence, and even his stance seems to diminish, shrinking into himself as the scene continues. “Hap and Leonard” is a type of television show that would be, in many other iterations, not much to comment on. The show is based on the mystery novels of Joe R. Lansdale, and as so many mystery stories do, takes the procedural structure as an excuse to spend a lot of time with its characters and its setting. The six episodes of the first season have the characters trekking through swamplands, encountering gators, skeet shooting, and listening to country-western LPs. It is normal in every way, and also, Leonard is a gay black man. And this willingness to, for lack of a better descriptor, go there is what makes the show strangely addictive and memorable, just in the way a particularly compelling mystery novel is. There’s a degree of formula at work, but at the same time, an enticing wrench thrown into the works. Similarly, “Underground” has a certain degree of formula at work, albeit in what is a far more controversial and revolutionary setting—the Underground Railroad, in the late 1850s, in the shadow of the controversial Dred Scott v. Sanford case that denied citizenship to African-Americans. This is not, exactly, the bleak plantation life of “12 Years a Slave,” but it is not the sunny view of antebellum South depicted in “Point of Honor,” either. Instead, “Underground” approaches overthrowing slavery with a sense of vim and vigor that it is normally denied—infusing the characters’ struggles to escape their oppression with the righteous indignation of any adventurers fleeing their particular dystopia. This is aided by the soundtrack, which incorporates modern hip-hop and period-appropriate spirituals in equal turns. It is the type of cross-genre historical-ish drama that fuels the campy fun of “Sleepy Hollow” and “Reign,” in that it is a bit more invested in the splash of its plot twists than in the resonance. The difference is that “Underground” is the first show to use slavery and the Underground Railroad as its setting; it has available to it an entire resonant system of symbols that have yet to be turned into television. Much like “Hap and Leonard,” the fascinating element of this show is that it is willing to expand its lens of empathy beyond the usual suspects; and indeed, it’s that quality that is the best part of both shows, what makes them stand apart from their formulaic underpinnings. When the N-word is used in “Underground,” it is dropped in the casual invective of the white person; it permeates the landscape and peppers the foreground, re-creating a terrible power structure with mere language. Partly, the N-word is on television more than ever just because it can be said on cable. But partly, it is that there is an expanded slate of programming featuring black characters—characters who, crucially and obviously, encounter racism. It is just a word, but it has broad implications for how to think about the past. And that does make quite a difference when thinking about the future.It is—or it should be—extremely startling to hear a white person use the N-word in 2016. Weirdly, this month on television, there are a lot of opportunities to hear just that. Last night, for example, on “The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story,” F. Lee Bailey (Nathan Lane) asked Mark Fuhrman (Steven Pasquale) if he’s ever used the slur, and in asking says the word, dispassionately, six separate times. But, of course, that scene comes from the real-life incident where Bailey asked Fuhrman those questions from the staid chambers of a courtroom in 1995, broadcast nationally to audiences everywhere. Sitcoms from “All in the Family” to “Black-ish” have devoted space to exploring the impact of the word, and network dramas have found a way to incorporate the slur into their own Very Special Episodes, as Josh Kurp details. But the preponderance of uncensored cable television has ushered in a new era of televisual profanity, and though shows like “Oz” and “The Wire” have gone whole-hog with every kind of insult, slur and derogatory phrase, there is something different about the language in two new cable shows: “Hap and Leonard,” on SundanceTV, and “Underground,” on WGN. Both shows are period pieces in the South, though of very different eras. “Underground,” which debuts tonight, takes place in plantation-era Georgia, and most of the characters are enslaved. “Hap and Leonard,” which debuted last week, takes place in East Texas in the ‘80s, at the height of the Reagan administration. And in both, the black leads are pointedly subject to racist language, including copious use of the N-word. It’s not pleasant, but it goes a ways toward exposing the long roots of racism in America. That a few assholes in the ‘80s would be fine with throwing the word around while pointing a gun at Leonard (Michael K. Williams) is perhaps not surprising. But watching the look on Leonard’s face as the scene unspools is surprising; the typically brash, shit-talking drifter is stunned into a self-preserving silence, and even his stance seems to diminish, shrinking into himself as the scene continues. “Hap and Leonard” is a type of television show that would be, in many other iterations, not much to comment on. The show is based on the mystery novels of Joe R. Lansdale, and as so many mystery stories do, takes the procedural structure as an excuse to spend a lot of time with its characters and its setting. The six episodes of the first season have the characters trekking through swamplands, encountering gators, skeet shooting, and listening to country-western LPs. It is normal in every way, and also, Leonard is a gay black man. And this willingness to, for lack of a better descriptor, go there is what makes the show strangely addictive and memorable, just in the way a particularly compelling mystery novel is. There’s a degree of formula at work, but at the same time, an enticing wrench thrown into the works. Similarly, “Underground” has a certain degree of formula at work, albeit in what is a far more controversial and revolutionary setting—the Underground Railroad, in the late 1850s, in the shadow of the controversial Dred Scott v. Sanford case that denied citizenship to African-Americans. This is not, exactly, the bleak plantation life of “12 Years a Slave,” but it is not the sunny view of antebellum South depicted in “Point of Honor,” either. Instead, “Underground” approaches overthrowing slavery with a sense of vim and vigor that it is normally denied—infusing the characters’ struggles to escape their oppression with the righteous indignation of any adventurers fleeing their particular dystopia. This is aided by the soundtrack, which incorporates modern hip-hop and period-appropriate spirituals in equal turns. It is the type of cross-genre historical-ish drama that fuels the campy fun of “Sleepy Hollow” and “Reign,” in that it is a bit more invested in the splash of its plot twists than in the resonance. The difference is that “Underground” is the first show to use slavery and the Underground Railroad as its setting; it has available to it an entire resonant system of symbols that have yet to be turned into television. Much like “Hap and Leonard,” the fascinating element of this show is that it is willing to expand its lens of empathy beyond the usual suspects; and indeed, it’s that quality that is the best part of both shows, what makes them stand apart from their formulaic underpinnings. When the N-word is used in “Underground,” it is dropped in the casual invective of the white person; it permeates the landscape and peppers the foreground, re-creating a terrible power structure with mere language. Partly, the N-word is on television more than ever just because it can be said on cable. But partly, it is that there is an expanded slate of programming featuring black characters—characters who, crucially and obviously, encounter racism. It is just a word, but it has broad implications for how to think about the past. And that does make quite a difference when thinking about the future.

Published on March 09, 2016 15:59

5 things you should know about methamphetamines — the “all-American” drug

Methamphetamine is a much-maligned drug. Even lots of people sympathetic to drug use or drug law reform scorn it. "I'm for legalizing weed, but meth? Never!" is a commonly heard refrain. There are good reasons for the disdain. Meth can create psychological dependence; people can behave bizarrely and unpredictably under its influence; and it can have deleterious health consequences ranging from dental problems to heart attacks and strokes to paranoia, anxiety and insomnia. Yet people continue to use it. It is an all-American drug, in the sense that people use it to work more. It provides a euphoric initial high, followed by an increase in energy and alertness that can last for up to 12 hours. Meth users feel higher motivation to accomplish goals and greater confidence in intellectual and problem-solving abilities—at least at first. But meth is no more harmful than any other substance taken in proper dosage. And government efforts to repress it have been ineffective at best and counterproductive at worst. Here are five things you need to know about meth.

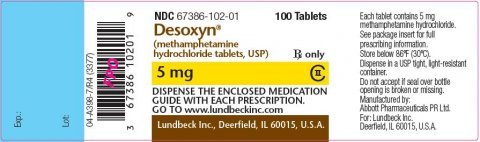

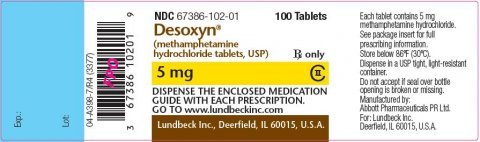

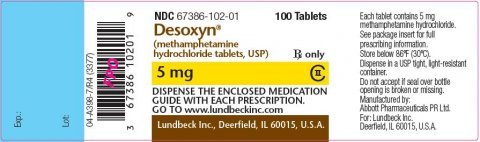

Methamphetamine is a much-maligned drug. Even lots of people sympathetic to drug use or drug law reform scorn it. "I'm for legalizing weed, but meth? Never!" is a commonly heard refrain. There are good reasons for the disdain. Meth can create psychological dependence; people can behave bizarrely and unpredictably under its influence; and it can have deleterious health consequences ranging from dental problems to heart attacks and strokes to paranoia, anxiety and insomnia. Yet people continue to use it. It is an all-American drug, in the sense that people use it to work more. It provides a euphoric initial high, followed by an increase in energy and alertness that can last for up to 12 hours. Meth users feel higher motivation to accomplish goals and greater confidence in intellectual and problem-solving abilities—at least at first. But meth is no more harmful than any other substance taken in proper dosage. And government efforts to repress it have been ineffective at best and counterproductive at worst. Here are five things you need to know about meth.  1. Meth is a prescription drug. Yes, that drug so terrible it should never be legalized is already available from your local doctor. Pharmaceutical-grade methamphetamine is produced by Abbot Laboratories under the brand name Desoxyn. It is a Schedule II controlled substance, like many prescription opioids and amphetamines, not a Schedule I drug with no accepted medical use, like heroin, LSD and even marijuana. It is prescribed for ADD, ADHD, narcolepsy, and obesity, although in small quantities because of fears of abuse and misuse. Still, at least some ADD/ADHD patients swear by it. 2. Meth is very similar to other amphetamine-type drugs. All those people taking Adderall (dextroamphetamine), Adzenys (amphetamine), Dexedrine (dextroamphetamine), Dynavel (amphetamine), Evekeo (amphetamine), Liquadd (dextroamphetamine), and ProCentra (dextroamphetamine) are using drugs very similar in chemical structure and effect to methamphetamine. A related class of drugs, the methylphenidates, which includes drugs such as Ritalin, acts like amphetamines in their dopamine reuptake inhibiting effect, but lack the dopamine releasing quality that amphetamines have. Different subjective experiences from these drugs results more from dosage and means of administration than differences in their chemistry. 3. There are about half a million regular meth users at any given time. According to the most recent survey, the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, there were 569,000 "past month" meth users, or 0.2% of the population. That number has been roughly stable over the past decade. But nearly twice as many people—about a million—were nonmedical users of other stimulants. The number of current meth users is smaller than the current number of nonmedical pain pill users (4.3 million), nonmedical tranquilizer users (1.9 million), cocaine users (1.5 million, including crack cocaine), and ecstasy users (609,000), but greater than the number of current heroin users (435,000), crack users (354,000) and LSD users (287,000). 4. Meth is a multibillion-dollar-a-year industry. The authors of

The Methamphetamine Industry in America

put the size of the illicit meth wholesale trade at $3 billion a year. The authors may overstate the size of the industry—they assume that every "past month" user is actually a daily user, which is certainly not the case—but they also note that they are looking at wholesale, not retail, so even if their wholesale estimate is too high, retail meth sales most definitely account for at least $3 billion in annual revenues. That's not a huge industry by national standards, but it is significant. It's about the same size as the tattoo parlor industry, the tanning salon industry, the online job search industry, or the baby formula industry. 5. And most of the profits now go to Mexican cartels. Thanks to state and federal legislation aimed at disrupting the home meth cooking trade by making crucial ingredients, such as pseudoephedrine, more difficult to obtain, what was once an industry dominated by biker gangs and small-scale, mom-and-pop labs producing relatively small amounts of meth for small numbers of people has now become an industry dominated by high-quality methamphetamine produced by Mexican drug cartels in "super labs" in Mexico, and increasingly, in the Southwestern U.S. As the authors of The Methamphetamine Industry in America note, the DEA estimates that Mexican cartels now account for 80% of meth consumed in the U.S. and they produce it with a stunning 90% or greater purity. These state and federal legislative efforts aimed at home meth labs have not reduced meth consumption, but they have reshaped the industry. They might as well carry the generic name the Mexican Methamphetamine Market Share Enhancement Act. Phillip Smith is editor of the AlterNet Drug Reporter and author of the Drug War Chronicle.

1. Meth is a prescription drug. Yes, that drug so terrible it should never be legalized is already available from your local doctor. Pharmaceutical-grade methamphetamine is produced by Abbot Laboratories under the brand name Desoxyn. It is a Schedule II controlled substance, like many prescription opioids and amphetamines, not a Schedule I drug with no accepted medical use, like heroin, LSD and even marijuana. It is prescribed for ADD, ADHD, narcolepsy, and obesity, although in small quantities because of fears of abuse and misuse. Still, at least some ADD/ADHD patients swear by it. 2. Meth is very similar to other amphetamine-type drugs. All those people taking Adderall (dextroamphetamine), Adzenys (amphetamine), Dexedrine (dextroamphetamine), Dynavel (amphetamine), Evekeo (amphetamine), Liquadd (dextroamphetamine), and ProCentra (dextroamphetamine) are using drugs very similar in chemical structure and effect to methamphetamine. A related class of drugs, the methylphenidates, which includes drugs such as Ritalin, acts like amphetamines in their dopamine reuptake inhibiting effect, but lack the dopamine releasing quality that amphetamines have. Different subjective experiences from these drugs results more from dosage and means of administration than differences in their chemistry. 3. There are about half a million regular meth users at any given time. According to the most recent survey, the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, there were 569,000 "past month" meth users, or 0.2% of the population. That number has been roughly stable over the past decade. But nearly twice as many people—about a million—were nonmedical users of other stimulants. The number of current meth users is smaller than the current number of nonmedical pain pill users (4.3 million), nonmedical tranquilizer users (1.9 million), cocaine users (1.5 million, including crack cocaine), and ecstasy users (609,000), but greater than the number of current heroin users (435,000), crack users (354,000) and LSD users (287,000). 4. Meth is a multibillion-dollar-a-year industry. The authors of

The Methamphetamine Industry in America

put the size of the illicit meth wholesale trade at $3 billion a year. The authors may overstate the size of the industry—they assume that every "past month" user is actually a daily user, which is certainly not the case—but they also note that they are looking at wholesale, not retail, so even if their wholesale estimate is too high, retail meth sales most definitely account for at least $3 billion in annual revenues. That's not a huge industry by national standards, but it is significant. It's about the same size as the tattoo parlor industry, the tanning salon industry, the online job search industry, or the baby formula industry. 5. And most of the profits now go to Mexican cartels. Thanks to state and federal legislation aimed at disrupting the home meth cooking trade by making crucial ingredients, such as pseudoephedrine, more difficult to obtain, what was once an industry dominated by biker gangs and small-scale, mom-and-pop labs producing relatively small amounts of meth for small numbers of people has now become an industry dominated by high-quality methamphetamine produced by Mexican drug cartels in "super labs" in Mexico, and increasingly, in the Southwestern U.S. As the authors of The Methamphetamine Industry in America note, the DEA estimates that Mexican cartels now account for 80% of meth consumed in the U.S. and they produce it with a stunning 90% or greater purity. These state and federal legislative efforts aimed at home meth labs have not reduced meth consumption, but they have reshaped the industry. They might as well carry the generic name the Mexican Methamphetamine Market Share Enhancement Act. Phillip Smith is editor of the AlterNet Drug Reporter and author of the Drug War Chronicle.

Methamphetamine is a much-maligned drug. Even lots of people sympathetic to drug use or drug law reform scorn it. "I'm for legalizing weed, but meth? Never!" is a commonly heard refrain. There are good reasons for the disdain. Meth can create psychological dependence; people can behave bizarrely and unpredictably under its influence; and it can have deleterious health consequences ranging from dental problems to heart attacks and strokes to paranoia, anxiety and insomnia. Yet people continue to use it. It is an all-American drug, in the sense that people use it to work more. It provides a euphoric initial high, followed by an increase in energy and alertness that can last for up to 12 hours. Meth users feel higher motivation to accomplish goals and greater confidence in intellectual and problem-solving abilities—at least at first. But meth is no more harmful than any other substance taken in proper dosage. And government efforts to repress it have been ineffective at best and counterproductive at worst. Here are five things you need to know about meth.

Methamphetamine is a much-maligned drug. Even lots of people sympathetic to drug use or drug law reform scorn it. "I'm for legalizing weed, but meth? Never!" is a commonly heard refrain. There are good reasons for the disdain. Meth can create psychological dependence; people can behave bizarrely and unpredictably under its influence; and it can have deleterious health consequences ranging from dental problems to heart attacks and strokes to paranoia, anxiety and insomnia. Yet people continue to use it. It is an all-American drug, in the sense that people use it to work more. It provides a euphoric initial high, followed by an increase in energy and alertness that can last for up to 12 hours. Meth users feel higher motivation to accomplish goals and greater confidence in intellectual and problem-solving abilities—at least at first. But meth is no more harmful than any other substance taken in proper dosage. And government efforts to repress it have been ineffective at best and counterproductive at worst. Here are five things you need to know about meth.  1. Meth is a prescription drug. Yes, that drug so terrible it should never be legalized is already available from your local doctor. Pharmaceutical-grade methamphetamine is produced by Abbot Laboratories under the brand name Desoxyn. It is a Schedule II controlled substance, like many prescription opioids and amphetamines, not a Schedule I drug with no accepted medical use, like heroin, LSD and even marijuana. It is prescribed for ADD, ADHD, narcolepsy, and obesity, although in small quantities because of fears of abuse and misuse. Still, at least some ADD/ADHD patients swear by it. 2. Meth is very similar to other amphetamine-type drugs. All those people taking Adderall (dextroamphetamine), Adzenys (amphetamine), Dexedrine (dextroamphetamine), Dynavel (amphetamine), Evekeo (amphetamine), Liquadd (dextroamphetamine), and ProCentra (dextroamphetamine) are using drugs very similar in chemical structure and effect to methamphetamine. A related class of drugs, the methylphenidates, which includes drugs such as Ritalin, acts like amphetamines in their dopamine reuptake inhibiting effect, but lack the dopamine releasing quality that amphetamines have. Different subjective experiences from these drugs results more from dosage and means of administration than differences in their chemistry. 3. There are about half a million regular meth users at any given time. According to the most recent survey, the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, there were 569,000 "past month" meth users, or 0.2% of the population. That number has been roughly stable over the past decade. But nearly twice as many people—about a million—were nonmedical users of other stimulants. The number of current meth users is smaller than the current number of nonmedical pain pill users (4.3 million), nonmedical tranquilizer users (1.9 million), cocaine users (1.5 million, including crack cocaine), and ecstasy users (609,000), but greater than the number of current heroin users (435,000), crack users (354,000) and LSD users (287,000). 4. Meth is a multibillion-dollar-a-year industry. The authors of

The Methamphetamine Industry in America

put the size of the illicit meth wholesale trade at $3 billion a year. The authors may overstate the size of the industry—they assume that every "past month" user is actually a daily user, which is certainly not the case—but they also note that they are looking at wholesale, not retail, so even if their wholesale estimate is too high, retail meth sales most definitely account for at least $3 billion in annual revenues. That's not a huge industry by national standards, but it is significant. It's about the same size as the tattoo parlor industry, the tanning salon industry, the online job search industry, or the baby formula industry. 5. And most of the profits now go to Mexican cartels. Thanks to state and federal legislation aimed at disrupting the home meth cooking trade by making crucial ingredients, such as pseudoephedrine, more difficult to obtain, what was once an industry dominated by biker gangs and small-scale, mom-and-pop labs producing relatively small amounts of meth for small numbers of people has now become an industry dominated by high-quality methamphetamine produced by Mexican drug cartels in "super labs" in Mexico, and increasingly, in the Southwestern U.S. As the authors of The Methamphetamine Industry in America note, the DEA estimates that Mexican cartels now account for 80% of meth consumed in the U.S. and they produce it with a stunning 90% or greater purity. These state and federal legislative efforts aimed at home meth labs have not reduced meth consumption, but they have reshaped the industry. They might as well carry the generic name the Mexican Methamphetamine Market Share Enhancement Act. Phillip Smith is editor of the AlterNet Drug Reporter and author of the Drug War Chronicle.

1. Meth is a prescription drug. Yes, that drug so terrible it should never be legalized is already available from your local doctor. Pharmaceutical-grade methamphetamine is produced by Abbot Laboratories under the brand name Desoxyn. It is a Schedule II controlled substance, like many prescription opioids and amphetamines, not a Schedule I drug with no accepted medical use, like heroin, LSD and even marijuana. It is prescribed for ADD, ADHD, narcolepsy, and obesity, although in small quantities because of fears of abuse and misuse. Still, at least some ADD/ADHD patients swear by it. 2. Meth is very similar to other amphetamine-type drugs. All those people taking Adderall (dextroamphetamine), Adzenys (amphetamine), Dexedrine (dextroamphetamine), Dynavel (amphetamine), Evekeo (amphetamine), Liquadd (dextroamphetamine), and ProCentra (dextroamphetamine) are using drugs very similar in chemical structure and effect to methamphetamine. A related class of drugs, the methylphenidates, which includes drugs such as Ritalin, acts like amphetamines in their dopamine reuptake inhibiting effect, but lack the dopamine releasing quality that amphetamines have. Different subjective experiences from these drugs results more from dosage and means of administration than differences in their chemistry. 3. There are about half a million regular meth users at any given time. According to the most recent survey, the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, there were 569,000 "past month" meth users, or 0.2% of the population. That number has been roughly stable over the past decade. But nearly twice as many people—about a million—were nonmedical users of other stimulants. The number of current meth users is smaller than the current number of nonmedical pain pill users (4.3 million), nonmedical tranquilizer users (1.9 million), cocaine users (1.5 million, including crack cocaine), and ecstasy users (609,000), but greater than the number of current heroin users (435,000), crack users (354,000) and LSD users (287,000). 4. Meth is a multibillion-dollar-a-year industry. The authors of

The Methamphetamine Industry in America

put the size of the illicit meth wholesale trade at $3 billion a year. The authors may overstate the size of the industry—they assume that every "past month" user is actually a daily user, which is certainly not the case—but they also note that they are looking at wholesale, not retail, so even if their wholesale estimate is too high, retail meth sales most definitely account for at least $3 billion in annual revenues. That's not a huge industry by national standards, but it is significant. It's about the same size as the tattoo parlor industry, the tanning salon industry, the online job search industry, or the baby formula industry. 5. And most of the profits now go to Mexican cartels. Thanks to state and federal legislation aimed at disrupting the home meth cooking trade by making crucial ingredients, such as pseudoephedrine, more difficult to obtain, what was once an industry dominated by biker gangs and small-scale, mom-and-pop labs producing relatively small amounts of meth for small numbers of people has now become an industry dominated by high-quality methamphetamine produced by Mexican drug cartels in "super labs" in Mexico, and increasingly, in the Southwestern U.S. As the authors of The Methamphetamine Industry in America note, the DEA estimates that Mexican cartels now account for 80% of meth consumed in the U.S. and they produce it with a stunning 90% or greater purity. These state and federal legislative efforts aimed at home meth labs have not reduced meth consumption, but they have reshaped the industry. They might as well carry the generic name the Mexican Methamphetamine Market Share Enhancement Act. Phillip Smith is editor of the AlterNet Drug Reporter and author of the Drug War Chronicle.

Methamphetamine is a much-maligned drug. Even lots of people sympathetic to drug use or drug law reform scorn it. "I'm for legalizing weed, but meth? Never!" is a commonly heard refrain. There are good reasons for the disdain. Meth can create psychological dependence; people can behave bizarrely and unpredictably under its influence; and it can have deleterious health consequences ranging from dental problems to heart attacks and strokes to paranoia, anxiety and insomnia. Yet people continue to use it. It is an all-American drug, in the sense that people use it to work more. It provides a euphoric initial high, followed by an increase in energy and alertness that can last for up to 12 hours. Meth users feel higher motivation to accomplish goals and greater confidence in intellectual and problem-solving abilities—at least at first. But meth is no more harmful than any other substance taken in proper dosage. And government efforts to repress it have been ineffective at best and counterproductive at worst. Here are five things you need to know about meth.