Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 734

June 29, 2016

Scotty Moore’s legacy: Elvis’s first guitarist helped create a signature rock sound

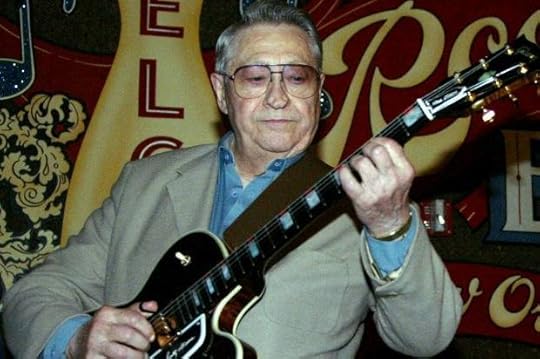

Scotty Moore, original guitarist for Elvis Presley, in 2003 (Credit: Judi Bottoni/AP)

Elvis Presley’s career had its ups and downs, and the contrarian impulse among culture-lovers means that some fans and critics try to reclaim even his worst eras. But during Presley’s greatest periods — his first few years of recording, in the mid-1950s, and his 1968 Las Vegas comeback special – he was accompanied by guitarist Scotty Moore. Before and after, Moore kept a much lower profile, playing low-key sessions with other musicians, managing a recording studio, and recording solo sessions that very few people heard.

It was an appropriate course for a musician who, despite the excess and egomania of many rock guitarists, rarely played an extra note.

Moore’s death on Tuesday — at age 84, at his home in Nashville – means that the original crew that cut Presley’s Sun Sessions, arguably the most important recordings of early rock ‘n’ roll, is now all gone. Some of the genre originators – Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis – are still alive. But rockabilly, that combination of country and western with the blues that became the first rock style, has lost one of its last important pioneers.

Moore’s style came from a simplicity and rhythmic directness combined with a distinctive effect called slapback. He wasn’t the first to use it, but the tape-delay that came from his EchoSonic amplifier in songs like Presley’s “Mystery Train,” from 1955, not only shaped rockabilly, it became the signature sound of revivalists like The Cramps and Chris Isaac, a kind of shorthand of retro-‘50s style.

His admirers included Bruce Springsteen, Jimmy Page, and Keith Richards, who says he knew he wanted to become a rock guitarist after hearing Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel.”

“Everyone else wanted to be Elvis,” Richards said in Moore’s biography. “I wanted to be Scotty.”

Presley’s first recording was “That’s All Right (Mama)” an Arthur Crudup song that Moore recorded with Presley and bassist Bill Black. The three were messing around at Sam Phillips’ Sun Studios one so-far-fruitless night in July 1954 when Presley started nervously strumming a fast version of the Crudup song, with Black and Moore joining in.

As Moore told Guitar Player magazine in 2014: “Sam poked his head out of the door — this was before mixing consoles had a talkback button — and he said, ‘What are you guys doing? That sounds pretty good. Why don’t you keep doing it?’”

“So I got my guitar, ran through it a couple of times, and that was it. That was the beginning of, how do you say it, all hell breaking loose!”

The song, which rivals Ike Turner’s “Rocket 88” in its claim to be the first-ever rock ‘n’ roll recording, was backed with a version of “Blue Moon of Kentucky.” All of the Sun Sessions are indelible — “I Don’t Care if the Sun Don’t Shine,” “Baby, Let’s Play House” — and even a song that Sun never released, “Trying to Get to You,” is a masterpiece, with some perfectly-turned fingerpicking on guitar. Often, Moore’s lead plays against Presley’s rhythm guitar — what Moore called “filling in holes” with sharp blues riffs and country licks.

After a few years with Presley — their songs together included “Jailhouse Rock” and “Hound Dog” — Moore was making only a few thousand dollars a year while the singer became a millionaire. Col. Tom Parker began to block the access Presley’s musicians had to the new star. As Elvis became less of a musician and more of a product, the guitarist dropped out.

Because of his well-timed exit, Moore missed Presley’s drift into bad movies and irrelevance. But he returned at just the right moment – for the NBC special that saw Presley revisiting songs from the Sun years, some early hits, and the gospel songs that served as a musical taproot.

But Presley’s camp paid him very little for the gig – reputedly, not enough for him to cover his expenses — and never asked him to go along on the ensuing tours. Musicians knew Moore, but he never became household name the way some of his inheritors did.

As rock music got more decadent and musicians often disappeared into their own egos, Moore remained an old-school gentleman who carried his own guitar and amp to gigs. His style hardly evolved, and none of his other sessions, either leading a band or playing with other musicians, matched his success with Presley. He avoided the dizzying highs and plummeting lows that defined the careers of many rockers. Instead of leaving behind wild stories, he leaves us with a guitar sound that no one who’s really listened to will ever be able to forget.

June 28, 2016

Sansa Stark has always been a warrior: She’s been fierce all along — and it kept her alive

Sophie Turner in "Game of Thrones" (Credit: HBO)

Until recently, it’s been lonely on Team Sansa. We “Game of Thrones” fans who have seen great potential in the Northern princess have been shouted down by fans who exclusively preferred more conventionally plucky heroines: She’s a frivolous little girl, they said; her dithering devotion to being the belle of the court, the queen to end all queens, helped get Ned Stark killed, they said; she’s always such a victim, they said. Now, Twitter erupts in exuberant cries of “Yes, Queen!” at the young woman who smirks with a well-earned satisfaction after she’s released the man-eating hounds on her rapist. That woman is simultaneously worlds away from the girl who stood in silent rage as another tormentor displayed her father’s head on a spike—and yet, she is still, in some ways, that same girl, the girl who had an uncanny instinct for survival.

Though the remaining Starks have known unfathomable woe, arguably none has endured the breadth and intensity of abuses and humiliations that Sansa has: Held as a hostage by the same wicked family who slaughtered hers; stripped, beaten, and humiliated by the boy-king Joffrey; married off to Tyrion (who does treat her with kindness and dignity—though, make no mistake, his decency is a gift to her, one that, had he been a different man, he could have revoked with impunity); fleeing for her life after she is framed for Joffrey’s murder—by the very man who takes her on as his pupil and ward, the man who kills her aunt (who, admittedly, was trying to kill her) and sells her into marriage with a man who gets his jollies flaying people alive (the scion of yet another family that killed hers), her rapist and most depraved torturer. Sansa’s capacity for endurance certainly rivals that of any of the more literally battle-hardened characters; indeed, her parlay with Jon Snow prior to the “Battle of the Bastards” displays the parallel lines of each character’s power: He has a warrior’s brute strength and fiery heart, and she has the foresight and tactical reserve that comes from constantly anticipating the next blow.

Characters like Jon Snow, or Brienne of Tarth, or Sansa’s sister Arya are so appealing because they possess the traits—bravery, strength (in terms of physicality and fortitude alike), and cunning—that we want for ourselves; and they earn those traits through the feats of honor, derring-do, and unbridled badassery that we fantasize ourselves capable of. Sansa’s resourcefulness is different—she has learned to keenly read her aggressors in the service of her own skin. When Tyrion Lannister intervenes to stop another beating (administered by one of Joffrey’s heavy-hitting Kingsguard), and offers Sansa out of her betrothal, she parrots back a line she said in fervent earnest back when her father tried to flee King’s Landing—that she loves Joffrey and wants to have his babies—only this time, her words are a refutation of the callow princess who believed in fairy tales and courtly lore, and a canny recognition that pretending to be that princess is the only way she has value, and having value is the only way she stays alive.

This is a sadder, more fragile way to be survivor; it doesn’t uphold any veneer of virtue or valor, it simply gets her through another hard night into another cold day. Our culture has very resolute standards about who gets to be heroic. Victims make us uncomfortable. We can’t accept that our continued safety in the world is so largely a matter of happenstance—being born to sane, loving parents, not leaving the party at that particular moment, with that particular person, or getting in the car just a few moments later—so we find ways to blame these people for their own agonies, even if merely getting through those agonies requires a Herculean fortitude. Only now that Sansa has weaponized her resourcefulness—she brings about Ramsay Bolton’s downfall by understanding his modus operandi (and anticipating Jon’s likely reaction to it, charging in with a righteous, yet blind, fury), and by leveraging Littlefinger’s twisted affections for her to procure the cavalry—is she seen as a compelling heroine. The host of the usually delightfully catty video recap series “Gay of Thrones” used to refer to Sansa as “busted redhead” (an ignoble distinction when even a character as reviled as Cersei is dubbed “evil Cher”). He’s recently given her a more Beyoncé-inspired nomenclature: Sansa Fierce.

Though I would argue that Sansa has, in her own quieter, more subtle way, always been fierce, I am heartened to see her become more active in her ferocity. She drives the Stark resurgence, turning the violations against her house and her body into her rallying cry against the Boltons—if she must always remember, in her deepest, most tender places, what was done to her, then the North will remember as well. If Sansa’s previous plot threads focused on the loss of innocence, and the heroism inherent in keeping her head down, now, her story has pivoted into the aftermath of victimhood—what happens when the blood dries and the bruises recede into muscle memory. Sansa is the callused, and at times, callous, survivor.

In a gorgeously written essay that I absolutely disagree with, Sean T. Collins argues that “revenge under any circumstance—even one as justly deserved as Sansa’s over Ramsay’s—is a sword without a hilt … There’s no way to control which way it swings and how deep it cuts.” Not so: Sansa’s blade has a clear, clean arc—killing Ramsay obliterates an evil, and it directly avenges the litany of terrors he inflicted upon her in any given night. Collins makes a very adept observation about Sansa reclaiming her own bodily autonomy by literally dismantling Ramsay’s body—I’d add that this act of dismantling also reflects what Ramsay tried to do to her spirit. Yet he did not break her. And her revenge, vicious as it is, is her ultimate assertion of self. She didn’t deserve what happened to her, but she does deserve to see her captor punished—though Ramsay would likely have been executed for his crimes against the Northern houses, particularly for killing Rickon Stark, he would not have been called to answer for crimes that could sadly be par for the course on any Westerosi wedding night.

In his essay, Collins laments Sansa’s violence because it seems in opposition to her father’s decency. It’s true that Sansa is no longer her father’s daughter—she is someone new, and more her own woman than ever before. Jon’s cleaving to Ned’s kind of honor nearly gets him and his men killed on the battlefield (and in the season six finale, he admits this to Sansa, praising her for recruiting the Knights of the Vale, even if it meant dealing with the decidedly dishonorable Littlefinger). Still, Sansa’s wrath is worth far more than tactical acumen. It is shared by anyone who has ever been brutalized without recourse, who has seen the wicked-doers walk free far too many times, and it builds a fresh dimension to the ways that survivors are portrayed on-screen.

Sansa is neither a martyr or an avenging angel—which are, by and large, the most prevalent kinds of onscreen survivorship. She occupies a space between these opposing modes, a space she shares with so many of us in the real world—a space between our broken places. Her strength feels so satisfying to viewers who have watched her be so mercilessly abused—but it is a many-chambered strength, and some of those rooms hold a deep, unpitying anger. This anger emerges when she kills Ramsay, of course, and it is in her voice when she says that the Umbers who gave Rickon to the Boltons should be hanged; it is in her threat to have her protector, Brienne, kill Littlefinger where he stands (the only reason she spares him, arguably, is to keep the Knights of the Vale in play). If she has, as Littlefinger once told her, been a bystander to tragedy, she has also been a bystander to power—and observed firsthand how it can insulate even a worthless little peon like Joffrey, or make a woman like Cersei’s will the law of the land.

Cersei and Sansa were initially portrayed as opposites—the soft, daydreaming princess and the hard-bitten, bitter-hearted queen—but in this season there was been a kind of alignment between the two. Both women have emerged from captivity determined to make the agents of their violations pay with blood. And both women crave the security and control that can come from a throne—though, admittedly, Sansa’s craving is more nascent, Littlefinger still knows that the way to pique her interest, however slightly, after she quite wisely rejects his offer of marriage, is to suggest that she could be the Queen in the North (and that he could make her that queen). She loves her half-brother and, in one of the sweeter scenes in the series, assures him that, bastard or no, he will always be a Stark to her—he will always share her blood. When he is crowned King in the North, she smiles at him with genuine joy. Then she looks out at Littlefinger, and the smile slips into a more arctic, inscrutable expression. There is a part of her, like a muscular tendril pushing up through unthawed earth, that demands to be honored and respected, that demands tribute. And to know that, with all of these things, she will never again be subject to anyone’s whims but her own.

As “Game of Thrones” enters its final episodes, Sansa Stark remains one of its most dynamic, complex female leads in a show rich with queens. She hasn’t been broken against the rock of her trauma. She is a knife-blade sharpened against the blunt horror of her experience. And she is uniquely positioned as a bracingly human exemplar of surviving trauma: able to love and hope in measured ways, hell-bent on protecting herself, and yes, capable of a fury to match the magnitude of the indignities she’s endured. I hope she doesn’t go full Cersei, though if she does, it will be undeniably compelling (and maybe, if you squint hard enough, just the tiniest bit deserved). If the show serves her well, it will keep her in that fertile ground between her broken places, between the quest for autonomy and the zeal for vengeance. For so long, her greatest feat in the great game has simply been drawing another breath, and then another one after that—in the next seasons, Sansa should do more than survive. Whether she becomes the Queen in the North, Jon Snow’s ruthless advisor, or simply her own woman, no more, no less—she should do what her long-time fans have always wanted for her: Thrive.

Secrets of “Blood Simple”: The devious neo-noir classic is more complicated than it looks

Dan Hedaya and M. Emmet Walsh in "Blood Simple" (Credit: Circle Films)

Here are some delicious nuggets of trivia I did not know about “Blood Simple,” the 1984 Texas neo-noir that marked the feature film debut of Joel and Ethan Coen. Usually I hate this kind of stuff, because most of the time it’s irrelevant. But each of these facts strikes me as integral to the success of the Coens’ epoch-shaping little movie. They are reasons why this devious and imaginative thriller worked as well as it did 32 summers ago, almost as much as the constantly shifting perspectives of Barry Sonnenfeld’s cinematography or Carter Burwell’s subtle, mood-controlling score. (Of the many Motown hits repurposed in ‘80s movies, I’m not sure any is as effective as the Four Tops’ “It’s the Same Old Song” in “Blood Simple.”) They’re reasons why it still works now, in a color-corrected digital restoration from Janus Films with a new 5.1 audio mix.

The phrase “Blood Simple” is never directly used in the film, although M. Emmet Walsh’s character, the sleazy, giggly and profoundly disturbing private detective Loren Visser, keeps hinting at it. (He calls people “money simple” a couple of times.) It comes from the Dashiell Hammett novel “Red Harvest,” when the nameless private detective known as the Continental Op complains about the town he’s supposedly cleaning up: “This damned burg’s getting to me. If I don’t get away soon, I’ll be going blood-simple, like the natives.” As the Coens have said, “Blood Simple” is closer to the sensibility of classic thriller writer James M. Cain than to Hammett, but that sentence comes close to summing up the movie.

Walsh’s ill-fitting leisure suit has peculiar bulges, as seen in the film, because he insisted that the Coens pay him in cash at the beginning of every week of shooting, and carried the money on him at all times. Whether that was method acting or a personality quirk is impossible to say. But it means that the scene when Loren stuffs thousands of dollars into his pockets, after double-crossing and killing Julian (Dan Hedaya), the man who has hired him to document his wife’s infidelity, is both something the character does and something the actor does. Ever since “Blood Simple,” there has been a strain of movie criticism arguing that the Coens are heartless technicians who don’t feel any empathy for their characters. That’s not without foundation, but this anecdote hints at the ways it’s overly simplistic.

Sticking with that theme, the Coens apparently had Loren drive what I believe is a 1968 Volkswagen Beetle in the film — a peculiar and deeply unlikely choice for a low-rent private investigator and/or hit man in central Texas — because they thought Walsh “looked like a bug.” Now, you can decide that’s Kafkaesque brilliance or you can decide that it drives you crazy because it’s manipulative and implausible. I’m not telling you what to think. But however you read it, the Beetle was an aesthetic choice, made while constructing an elaborate artifice.

The Coens denied any art-film intentions while making “Blood Simple,” which Ethan called “a no-bones-about-it entertainment” in a 1985 interview. “If you want something other than that, then you probably have a legitimate complaint,” he joked. OK, I get where he’s going with that, but the Coens aren’t as far away as they like to pretend from the worldview of a director like Michael Haneke, who frequently confronts us with the fact that a movie is a constructed illusion rather than a depiction of the “real world,” and beyond that a shared illusion whose narrative and meaning are created by the viewer as much as by its maker.

These guys went on to make a series of movies, after all, in which naturalism and artificiality are in a constant state of crisis and collision. That breaks through the surface of the story most obviously in “Barton Fink,” but is just as apparent in different ways in “The Big Lebowski” or “A Serious Man” or “Inside Llewyn Davis.” (I’m not going to get involved in defending the Coens’ most recent movie, “Hail, Caesar!” right now, but it’s a work of mischievous genius, however badly miscalculated in marketplace terms.)

In a 2015 interview with Guillermo del Toro, Ethan Coen describes Walsh’s opening monologue in “Blood Simple” this way: “Emmet’s monologue is, like, ‘Let me tell you about the real world,’ and the joke is it’s not exactly the real world, but that’s the proposition.” As del Toro then responds, “I think that’s basically most of the filmography.” If it bugs you too much that Walsh drives a Bug, the Coens would politely suggest that you are likely to find other kinds of movies more to your taste. I’m not saying they wouldn’t say mean stuff about you after you’d left the room.

So what kind of movie did the Coens make, exactly? It seems that Barry Sonnenfeld, the brilliant cinematographer who also made his debut with “Blood Simple,” and would move on to become an A-list Hollywood director with “The Addams Family” and the “Men in Black” series, suggested that the brothers watch three films before starting work on this one. They were Stanley Kubrick’s “Dr. Strangelove,” Bernardo Bertolucci’s “The Conformist” and Carol Reed’s “The Third Man.”

I mean, arguably anyone should see those three movies before doing anything, or at least before assuming that they understand anything about human motivation or politics or the relationship between cause and effect. But all of them are present in “Blood Simple”: the anarchic, apocalyptic black humor of “Strangelove,” the bleak and beautiful fatalism of Bertolucci’s Fascist-era thriller and the devious, cynical philosophy of Harry Lime, Orson Welles’ unforgettable character in “The Third Man.” How a couple of nerdy Jewish guys from suburban Minneapolis, by way of New York City, combined those ingredients into a low-budget B movie made in Texas that both is and is not about its archetypal American setting, and is and is not a series of literary and film-school references — that part defies easy explanation.

Do the Coens, in “Blood Simple” and numerous other films, depict a cruel universe whose moral entropy leads people (normal and decent people, or the other kind) into bad decisions that never go unpunished? Is that a philosophy of life, or just a narrative contrivance gleaned from too many books and movies? Well, the answers are pretty clearly “yes” and “yes,” but watching this beautiful restoration of “Blood Simple” I was actually struck by how non-bleak it is, how much the strength of the film lies in images of beauty, defiance and survival. Even the despicable Loren laughs at fate as he dies; it’s almost an Ingmar Bergman moment, staged under the bathroom sink in a desolate Texas apartment. As in so many subsequent Coen pictures, Frances McDormand (not yet married to Joel Coen) embodies a transcendent female energy in this disordered tale of betrayal and murder, a combination of shrewdness, toughness and intelligence that can absorb many terrible things without being defeated.

In fact, it almost seems relevant that the Coens raised crucial seed money for “Blood Simple” from local members of Hadassah, the international Jewish feminist organization, in St. Louis Park, the middle-class Minnesota suburb where they grew up. That was a mitzvah, for sure, but I can’t help wondering what the do-gooder women of St. Louis Park thought they were contributing to, and what they thought of the final product. Maybe they got paid back decades later in “A Serious Man,” the Coens’ most autobiographical and most overtly Jewish film. And maybe they didn’t need to get paid back. “There’s not a moral to the story, and we’re not moral preceptors,” Joel Coen told del Toro. Not that I claim to understand Talmudic philosophy, or any other kind, but isn’t that pretty close to a moral precept in itself?

The new 4K restoration of “Blood Simple” from Janus Films opens this week at Film Forum in New York and the Alamo New Mission in San Francisco, and opens July 29 at the Nuart Theatre in Los Angeles, with more cities and home video to follow.

Rob Sheffield: “What I love most about David Bowie is that he celebrated the romance of being a fan.”

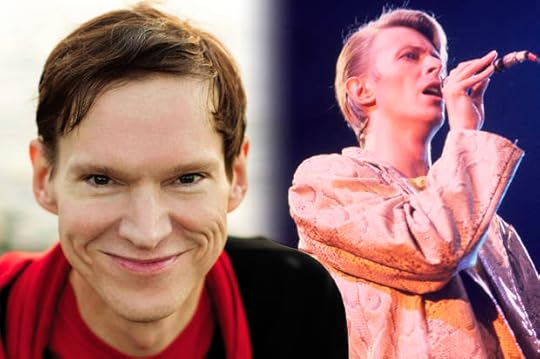

Rob Sheffield, David Bowie (Credit: Marisa Bettencourt/AP/Brian Killigrew/Photo montage by Salon)

When Rob Sheffield learned that David Bowie died, he stayed up all night and the next day writing about his hero. The longtime critic and “Rolling Stone” columnist wrote with no real purpose or goal in mind, but simply tried to get ideas on paper. It was his own personal wake for the man who wrote “Space Oddity” and “Starman,” who embodied so many different roles, who inspired Sheffield and millions of other fans around the world. “Words were just pouring out of me,” he recalls. “It was impossible not to write about David Bowie and listen to David Bowie and mourn for David Bowie.”

In the morning, as others were just waking up to the sad news, Sheffield received a call from his editor, who wanted him to keep writing. He spent all of January 2016 and part of February reconsidering Bowie’s greatest hits and his greatest guises, and the result is “On Bowie,” a book-length eulogy for the mercurial rock star that debuts today. Sheffield takes us through the man’s life and career, from his first fluke hit through his glam ascendancy, from his forays into Philly soul to his Thin White Duke experimentalism, from his early ‘80s highs to his late ‘80s lows, from his disappearance in the 2000s to his comeback in the 2010s.

Bowie, of course, is one of the popular and written-about rock stars in the world, and there are scores of biographies that trace a similar trajectory. What makes “On Bowie” unique—what makes it something other than redundant—is its mix of biography and autobiography. In writing about Bowie’s career, Sheffield cannot help but write about his own life and his own experiences with Bowie’s music. As a teenager growing up in Boston, he found inspiration and consolation in songs like “Heroes” and “Let’s Dance” and “Boys Keep Swinging,” dissecting their lyrics and sequencing them on countless mixtapes for himself and his friends. This kind of close identification with an artist can be indulgent or critically irresponsible, but in “On Bowie,” it’s absolutely crucial in presenting the celebrity through the eyes of a fan and in humanizing an artist who barely appeared human onstage.

This is perhaps Sheffield’s greatest trait as a critic: He writes with the enthusiasm of a true fan, whether he’s extolling A Flock of Seagulls in the “Spin Record Guide” or explaining how music helped him grieve his wife in “Love Is a Mixtape” or examining the impact New Wave had on his life in “Talking to Girls About Duran Duran.” His prose burbles with joy and excitement, which may cloud his judgment (he perhaps overpraises Bowie’s ‘90s output) but makes his books refreshing and relatable. Anyone who has ever carefully planned out a mixtape or listened to the same song ten times in a row or driven hundreds of miles just to a see a band perform will recognize something of themselves in Sheffield’s writing—just as Sheffield recognized something of himself in David Bowie.

Especially after so many quick eulogies and hot takes, the topic of David Bowie still seems inexhaustible. Why do you think that is?

David Bowie is somebody who exists on so many different planes. Every audience has their own David Bowie and every culture and really every fan has their own David Bowie. For me, part of grieving for David Bowie after his death was having so many conversations with my friends about our experiences with him and learning all the different things he meant to people. There are so many different ways to live your Bowie-ness and so many different ways to hear him. It’s funny that is was only after he died that I found out what a huge deal “Labyrinth” is in his canon. When that movie came out, I was already a teenager and was not interested in seeing David Bowie in a kids movie with Muppets, so I didn’t realize that for a huge number of his younger fans “Labyrinth” is the gateway drug that got them into Bowie. That’s an example of the things that I kept learning about David Bowie, who is someone I’ve loved all my life and someone I keep learning more and more about even after he died.

I’m constantly surprised by the love for “Labyrinth.” It definitely seems to be a movie that millennials have embraced.

There was a beautiful tribute at a punk DIY spot in Brooklyn called Silent Barn, where a bunch of bands covered the “Labyrinth” soundtrack all the way through. There were ten bands, and each one would play a different song. That was one of the strangest David Bowie tributes I witnessed, but it was a beautiful thing. It was this different side of David Bowie for people who were born in the ‘80s or ‘90s. For me, though, I barely remember that this movie ever happened. I was a New Wave kid in the ‘80s, so the David Bowie of “Let’s Dance” was huge for me. For a lot of other fans, though, that album is some aberration in his career, where he tried to do something that didn’t hold up very well in retrospect. I’m very much a “Let’s Dance” loyalist, and another thing I took away from the conversations I had with friends about David Bowie was that I was maybe in the minority about that. His New Wave period didn’t mean the same to everybody that it meant to me.

My first Bowie record was “Never Let Me Down,” so I have a weird affection for that era.

You’re definitely in the minority there.

No kidding. But it was the first record he released when I was of record-buying age. You have a completely different experience with Bowie depending on where you enter his story.

For me it was “Lodger.” That was the first one that came out when I was already a David Bowie fan. I had already been listening to FM rock radio and knew “Heroes,” and then “Lodger” came out. I have a massive affection for that one. I’m capable of very long and very tedious arguments in bars defending that record. I love “Lodger.” You can love David Bowie in all these different ways, so there’s always more to discover from him. My theater friends have a totally different Bowie than I do. My fashion friends have a completely different Bowie. My art friends, my film friends, everybody. He dabbled in so many different kinds of stuff and incorporated so many different types of expression into his overall statement, and it’s amazing that people live and die for entire corners of the Bowie universe that I barely even know. Part of the way he saw his journey as an artist was dabbling in everything that interested him, whether he had a deep-rooted talent for it or not. He figured he would do it and if it came out disastrously, he’d have a laugh at it and move on. That meant he was able to participate in so many different worlds and so many different artistic languages.

The book portrays him as a fan in his own right, someone who’s constantly listening to other artists and integrating their ideas into his own music. Sometimes he has great taste, as with Iggy Pop or Lou Reed. Sometimes not, as with the Polyphonic Spree.

It’s amazing and really inspiring how personal a fan he was. That’s something that he never lost even after he had been making music for fifty years. That last album he made—when he knew he was close to the end of his life—was so influenced by Kendrick Lamar and D’Angelo, artists who were so much younger than he was. But he listened to them and got different ideas about how to approach music. He was still so passionate about learning and absorbing new influences. There’s an awful lot of rock stars his age who do not share that trait.

It never sounded like he was retreating into the music of his own adolescence or trying to recapture an older sound. He didn’t seem like he was interested in looking backwards.

That’s a constant throughout his career: He’s always interested in the moment. David Bowie was less interested in nostalgia than any great rock-and-roll artist who ever existed, whether it’s 1965 and he’s doing John Lee Hooker and James Brown songs or it’s 1975 and he’s influenced by the O’Jays and the Stylistics or it’s 2015 and he’s listening to Kendrick and D’Angelo. He’s always interested in what’s going on right now. It’s really weird to think that he was listening to “Black Messiah” and “To Pimp a Butterfly” at the same time we were all listening to those album and getting our minds blown by them. And David Bowie was also getting his mind blown by them. He was willing to learn from it. He was someone who was never satisfied with anything he did before and really reluctant to rest on his laurels. He was definitely not someone who was willing to settle for “legacy artist” status. He always wanted to do something new.

But he’s not always successful. “Blackstar” is amazing, but there were times when he was listening to something but not able to transform it into something that’s new or personal. I’m thinking of “Earthling” in particular, which tried to incorporate some drum ‘n bass elements.

Sometimes he’d try something and it would get the better of him. When he tried to do a reggae song [“Don’t Look Down,” off 1984’s universally-reviled “Tonight”], to his credit he only tried to do one reggae song. He did that one and was like, okay, reggae requires a certain emotional skill set and a certain rhythmic skill set that I do not have. He didn’t make a lot more reggae songs. He tried it once and it didn’t fit his particular toolbox. It’s funny you mention his drum ‘n bass album, which is a good example of him hopping a trend right at the time everybody else is really done with it. So the production was not impressive, but he still managed to write songs that were really impressive. He wasn’t necessarily trying to become a master at any of these styles, but just wanted to see what he could learn from them.

Have you ever read the speech he gave at the Berklee College of Music for its commencement in 1999? It’s a really beautiful and funny speech. He said it was funny to be a songwriter talking to real musicians. He said he figured out his place in music in the ‘60s when he tried playing saxophone. And he was a terrible saxophone player and knew he couldn’t express himself playing that instrument. But he also said something like, I can put together different elements of different music and I had figured out the Englishman’s true place in rock and roll. Which is that there was no way he was going to approach anything from the context of virtuosity or authenticity. All he really had to bring to it was curiosity.

That attitude does so much to humanize him. Here’s a guy playing with all these masks and disguises, yet there does seem to be a curiosity driving every decision.

There’s a continuity through all the different phases. He’s a very musically curious and emotionally curious and sexually curious and artistically curious human presence through it all. There’s a tangible emotional aspect to all these experiments that he does. Some of them turn out to be disasters and some of them turned out to be hugely influential. But he was constantly willing to try things and see what happened.

And part of that was constantly referring back to himself and creating this personal mythology through these various songs. He spent decades exploring that outer space metaphor he introduced on “Space Oddity.”

There’s this great song on “Heathen” from 2002 called “Slip Away,” and it’s about being in Coney Island and riding the ferris wheel with his daughter. At the top of the ferris wheel he looks down and it feels like he’s looking down on his past and all these outer space adventures that he used to contextualize in whatever drug or sex or rock-and-roll extreme he was indulging at that time. There’s this beautiful line in the song where he sings, “Down in space it’s always 1982.” It cracks me up to think that this theme of space exploration is something he started strictly as a gimmick, but it became a lifelong metaphor for self-discovery and transformation. Part of what makes him such an inspiring figure is that he was committed to that transformation his entire life. How insane is it that he was able to actually have a happy marriage for the last couple decades of his life—and with a model! That seems like the ultimate transformation.

And it meant he was able to age with some dignity, as opposed to having to go back and play “Starman” on nostalgia tours. He’s one of those rare artists for whom the narrative didn’t stop. His story kept going as he kept evolving.

Absolutely. He was not willing to concede that the narrative had stopped, and I think he attracted the type of audience that didn’t want him to stop. Nobody wanted to go to a David Bowie show and hear all of his greatest hits from the early ‘70s. That would not have been satisfying. He attracted the kind of audience that wanted him to keep trying new things, whether he was good at them or not. I remember seeing him at Madison Square Garden in 2003 where he did three songs from the album “…Outside.” It’s a terrible album, but he did three of those songs. At one point, he said, I’d like to do another song from “… Outside,” and there were a few assorted whoo’s. And he said, All seventeen people who bought that album are clearly here in this room.

We knew we could trust him to do what seemed interesting to him at the moment. We knew he wasn’t phoning it in. If you went to a David Bowie where it felt like he was trying to give the audience what they wanted, it would have been exactly what the audience didn’t want. He wanted his fans to feel hideously appalled and sometimes feel pity and sometimes feel shock and sometimes feel anger. He wanted that response from his fans and that’s what he got.

One of the things I’ve appreciated about your books is how you write with the enthusiasm of an unabashed fan. This book and especially “Talking to Girls About Duran Duran” are about what it means to be a fan and have such an intense connection with an artist. Is that draws you to David Bowie, who shares that similar sense of fandom?

When I was a kid, that was something that was easy to notice right away. He was a fan of the music around him, and he was someone who didn’t see it as a thing where artists were on this mountaintop and the audience was on the ground accepting whatever thunderbolts were thrown down from the clouds. He was someone who was very engaged with his audience. You remember that greatest hits album, “Changesonebowie,” that came out in ’76? I love that album. It’s a greatest hits album where every song sounds like a different guy who’s a fan of something completely different. Listen to a song like “Diamond Dogs” and it’s a guy saying, My god, the Stones are the best ever! Then you listen to “Fame,” and it’s a guy saying, The O’Jays are where it’s at! You listen to “Golden Years,” and this guy is saying, Disco is a galactic language of communication and language! Then you go back to the first side and listen to “Space Oddity,” and that guy is strumming an acoustic guitar and saying, Bob Dylan taught me so much!

That’s one thing about David Bowie: H e was always upfront about being a fan in a way that was radical and unprecedented for rock stars in the ‘70s. He was very upfront about the fact that he was stealing ideas from everything he liked. In the book I talk about that interview with Dinah Shore on her morning talk show in 1976, where he says, I’m very flirty and very faddy and I get easily saturated by things. I’m a big fan of different artists and I just steal things from them. And Dinah Shore basically says, I can’t believe you’re admitting this on TV. His response was, I steal things. That’s what I do. That’s what it really means to be a fan. We steal pieces of our emotional selves from the music we love. There are aspects of my personality that I have modeled on Bowie and aspects that I based on Aretha Franklin and aspects that I modeled on Janet Jackson and Stevie Wonder and Paul McCartney and Lou Reed—all these different artists who have been so inspiring to me in different ways. That’s the thing about being a fan: You steal things from the artists you love. David Bowie saw that as a lifelong heroic, romantic quest, and he was not at all embarrassed about that aspect of being a fan. To me that’s very moving and inspiring. What I love most about David Bowie is that he celebrated the romance of being a fan.

And that elevates the fan. It allows you to create your own personal Ziggy Stardust out of all of these different people. Listening becomes a creative endeavor rather than something passive.

You don’t just listen to one kind of music and become one kind of persona. You listen to different kinds of music and explore different kinds of art and read different kinds of books and then you combine those ideas in ways that turn out to be who you are. That can be a threatening idea, especially for rock stars in the ‘70s who were more interested in establishing their roots or their authenticity. Whereas David Bowie presented being a fan as a creative adventure. It’s not about being a passive receptacle of pop culture. It’s more about being a creative participant in pop culture. As long as you’re passionate about music, something creative will come of it.

D.C. enacting $15 minimum wage indexed for inflation, in huge victory for labor rights

(Credit: AP/Seth Wenig)

The growing Fight for 15 movement had a huge victory this week.

Washington, D.C. passed legislation on Monday night that will increase the minimum wage to $15 by 2020 and index it for inflation.

Mayor Muriel Bowser signed The Fair Shot Minimum Wage Act in D.C.’s Columbia Heights neighborhood.

Three months ago, I said we would take up the #FightFor15 in DC and I am so excited to sign it into law today! pic.twitter.com/Ps7pkQVk1H

— Mayor Muriel Bowser (@MayorBowser) June 27, 2016

The current minimum wage in D.C. is $10.50 per hour, although it is slated to increase to $11.50 later this week, The Huffington Post reported. In 2017, it will be increased to $12.50.

D.C. is one of the most expensive cities in the U.S.

The new legislation will incrementally increase the minimum wage to $15 in 2020. The minimum wage for tipped workers will rise from $2.77 now to $5 per hour before tips, although employers must pay the difference if the worker does not make more than $15 per hour with tips.

In an even bigger victory for labor rights, the new law will also increase the minimum wage annually based on an inflation index, so the real wage of workers will not diminish over time.

In 2014, the D.C. council voted to permanently tie the minimum wage to inflation, in a decision that was applauded by unions and labor rights groups throughout the country.

Earlier this month, the D.C. council unanimously voted for the $15 minimum wage, although the measure was only just signed into law on June 27.

SEIU local 1199 called the wage boost “a huge victory for DC workers.” It attributed the win to “the tireless fight waged by workers, activists and labor unions.”

The Economic Policy Institute, a left-leaning think tank, estimates the new minimum wage will benefit 114,000 workers, roughly 14 percent of all D.C. workers and more than one-fifth of the district’s private-sector workers.

Washington DC raises its minimum wage to $15 an hour, giving 114,000 working people a boost. https://t.co/3mxc8y0VMx pic.twitter.com/SuWbHazO5h

— Economic Policy Inst (@EconomicPolicy) June 27, 2016

“Far from the stereotype of low-wage workers being teenagers working to earn spending money,” the Economic Policy Institute emphasized, “those who would benefit are overwhelmingly adult workers, most of whom come from families of modest means, and many of whom are supporting families of their own.”

Kate Black, executive director of the women’s rights advocacy group American Women, applauded the wage increase as “a welcome relief for the thousands of minimum-wage workers in the District.”

She noted that the new increase will greatly help women. “Nationally, two-thirds of minimum-wage workers are women and more than half are 25 or older,” Black stressed.

“The reality is that our workforce has changed, with women now making up nearly half of the labor force, and they are primary or co-breadwinners in two-thirds of American households,” she continued.

The wage increase will also greatly benefit Americans of color, who are disproportionately employed in low-wage jobs.

Some of the U.S.’s biggest cities, including Los Angeles and San Francisco, have passed $15 minimum wage laws.

New York state and California will also be implementing $15 minimum wages in the next several years.

These victories have been the culmination of years of organizing by workers, labor unions and activists.

Seattle was the first major U.S. city to pass a $15 minimum wage, after a struggle launched by the group Socialist Alternative. Seattle City Councilmember Kshama Sawant, one of the only elected Marxists in the U.S., helped lead the campaign for a living wage.

Since then, the grassroots Fight for 15 movement has blossomed into a powerful national movement, with the active participation of thousands of low-wage workers.

The federal minimum wage is presently just $7.25 per hour.

Since 2013, 18 states and D.C., along with nearly 50 cities and counties, have raised the minimum wage, benefiting the lives of millions of American workers.

Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton has been ambiguous on the issue. She has called for a $12 federal minimum wage, although she says she supports a $15 minimum wage in certain states.

Her opponent, self-declared democratic socialist Bernie Sanders, called for a $15 federal minimum wage as a national standard that can be increased in more expensive states.

At a hearing of the Democratic National Committee’s platform drafting committee on June 24, the representatives appointed by Clinton voted against a $15 minimum wage amendment that was supported by the representatives appointed by Sanders.

Clinton’s representatives argued the DNC platform already expresses support for a $15 minimum wage, but the language is weak and offers no specific mechanism for getting there. Sanders’ supporters, led by Rep. Keith Ellison, called for the explicit demand of an indexed $15 federal minimum wage to be written into the Democratic Party’s platform. Clinton’s surrogates opposed the measure.

Deborah Parker, a committee member appointed by Sanders, called the present federal minimum wage a “starvation wage” and emphasized that single parents cannot afford to work on the minimum wage and provide for their children.

Rep. Ellison stressed that, if the minimum wage in 1968 had been indexed for inflation, it would be at least $22 today.

“We are going through one of the worst periods of wage stagnation in our nation’s history,” he said. Ellison pointed out that Americans who are working full-time on the federal minimum wage are eligible for food stamps, section 8 housing and Medicaid.

“One of the problems in our economy, and the reason we’ve had slow growth, is because the average working American doesn’t have any money,” he continued. “You can’t spend money that you don’t have.”

Even small business owners are hurt by the low minimum wage, Ellison added, “because their customer base is broke.”

UPDATED: 2 explosions rock Istanbul airport, killing at least 28

Paramedics push a stretcher at Turkey's largest airport, Istanbul Ataturk, Turkey, June 28, 2016. (Credit: Reuters/Osman Orsal)

Several suicide bombers have hit the international terminal of Istanbul’s Ataturk airport, killing at least 28 people and wounding some 60 others, Istanbul’s governor and other officials said Tuesday.

Turkey’s NTV television quoted Istanbul Governor Vasip Sahin as saying authorities believe three suicide bombers carried out the attack.

“According to initial assessments 28 people have lost their lives, some 60 people have been taken to hospitals. Our detailed inspections are continuing in all aspects,” Sahin said.

“The entry and exit of passengers are being returned to normal rapidly and planned flights will resume as soon as possible,” he added.

Roads around the airport were sealed off for regular traffic after the attack and several ambulances could be seen driving back and forth. Hundreds of passengers were flooding out of the airport and others were sitting on the grass, their bodies lit by the flashing lights of the emergency vehicles.

Twelve-year-old Hevin Zini had just arrived from Dusseldorf with her family and was in tears from the shock.

She told The Associated Press that there was blood on the ground and everything was blown up to bits.

South African Judy Favish, who spent two days in Istanbul as a layover on her way home from Dublin, had just checked in when she heard an explosion followed by gunfire and a loud bang.

She says she hid under the counter for some time.

Favish says passengers were ushered to a cafeteria at the basement level where they were kept for more than an hour before being allowed outside.

Turkish Justice Minister Bekir Bozdag earlier said that according to preliminary information, “a terrorist at the international terminal entrance first opened fire with a Kalashnikov and then blew himself up.”

Another official said attackers detonated explosives at the entrance of the international terminal after police fired at them.

The official, who spoke on condition of anonymity in line with government protocol, said the attackers blew themselves up before entering the x-ray security check at the airport entrance.

Turkish airports have security checks at both the entrance of terminal buildings and then later before entry to departure gates.

Two South African tourists, Paul and Susie Roos from Cape Town, were at the airport and due to fly home at the time of the explosions and were shaken by what they witnessed.

“We came up from the arrivals to the departures, up the escalator when we heard these shots going off,” Paul Roos said. “There was this guy going roaming around, he was dressed in black and he had a hand gun.”

The private DHA news agency said the wounded, among them police officers, were being transferred to Bakirkoy State Hospital.

Turkey has suffered several bombings in recent months linked to Kurdish or Islamic State group militants.

The bombings include two in Istanbul targeting tourists – which the authorities have blamed on the Islamic State group.

The attacks have increased in scale and frequency, scaring off tourists and hurting the economy, which relies heavily on tourism revenues.

Istanbul’s Ataturk Airport was the 11th busiest airport in the world last year, with 61.8 million passengers, according to Airports Council International. It is also one of the fastest-growing airports in the world, seeing 9.2 percent more passengers last year than in 2014.

The largest carrier at the airport is Turkish Airlines, which operates a major hub there. Low-cost Turkish carrier Onur Air is the second-largest airline there.

Even Fox News forced to admit — GOP’s two-year, $7 million Benghazi charade revealed “no new evidence”

Fox News' Shepard Smith

South Carolina Congressman and Chairman of the House Select Committee on Benghazi Trey Gowdy was noticeably irritated as he defended the committee’s 800-page report on the 2012 attack on a U.S. consulate in Libya, the eighth such congressional investigation.

The first question Gowdy received hours after releasing the Republicans’ report was a grilling on the historical length and cost of the investigation. Longer than Congress’ inquiry into Watergate, Gowdy’s committee spent two years and $7 million in taxpayer funds to find little information that the seven previous investigations hadn’t already uncovered.

Here is the opening paragraph from the New York Times‘ write-up of the committee’s report released shortly before Gowdy took to the microphones at his press conference:

Ending one of the longest, costliest and most bitterly partisan congressional investigations in history, the House Select Committee on Benghazi issued its final report on Tuesday, finding no new evidence of culpability or wrongdoing by Hillary Clinton in the 2012 attacks in Libya that left four Americans dead.

“My job is to report facts,” Gowdy later told reporters. “You can draw whatever conclusions you want to draw,” he said, repeatedly encouraging them to read the report he had released only hours earlier.

While Gowdy feigned incredulity about Democratic criticism of his committee’s report, telling reporters, “Color me shocked that they are critical of our report,” even some conservatives are apparently unwilling to play along with the GOP’s charade.

“After a two-year, $7 million investigation the eighth investigation to date, the authors of the report make no new accusations and provide no new evidence of wrongdoing against the former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton,” Fox News host Shepard Smith reported to his viewers on Tuesday — refusing to go along with his network’s script of using the report to attack Clinton.

Watch Smith’s reporting, via Media Matters, below:

The Strokes’ energetic return: Play “spot the reference” in this dizzying pastiche video

The Strokes' "Threat of Joy" video. (Credit: YouTube/Cult Records)

For the first time in five years, The Strokes have dropped a new video. “Threat of Joy” – the song appears on their recent EP “Future Present Past” – is like the much-hyped New York band in a nutshell: Both the video and the song are almost dizzyingly derivative of others’ work, and they are also so energetic and winning it’s hard to really mind.

The Strokes, of course, have been criticized for sounding like other groups for a decade and a half now. Their debut album, “Is This It,” contained echoes of Television, The Velvet Underground, Pavement, and various punk bands. Still, it was full of force and a sort of jaded enthusiasm about music, New York, and being young.

“Threat of Joy” distills that early thrill 15 years later. Musically, the song shows the band in glorious riff-driven form, with a gently distorted guitar chopping out a phrase matched with occasional Beatles-esque fills on another. It’s hard to listen to the muffled vocals and not be reminded how much singer Julian Casablancas owes to Pavement’s Stephen Malkmus. (There’s a bit of Modern Lovers-era Jonathan Richman here as well.) Lyrically, it seems to be either a breakup song with drug addiction as its subtext or vice versa – meaning, it’s like a huge number of Lou Reed-shadowed rock songs.

The video has nearly as many references. It starts out showing the supposed making of the video for another song from the same EP, “Oblivius” (sic). Suddenly, terrorists burst in, abduct the director, and steal the film reel footage, and now we’re watching a live performance of “Threat of Joy.”

Over the next few minutes, we get a quick mashup of a caper film (the Beastie Boys’ “Sabotage” without the ‘70s mustaches), lyrics printed on pieces of cardboard and discarded (Bob Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues” segment from “Dont Look Back”), a sexually charged costume ball (shades of Stanley Kubrick’s “Eyes Wide Shut”) and men in suits and pig masks (okay, this last part may have been dreamed up by the Strokes.)

Throughout, the original film reel is stolen, traded, stolen back, and revealed to be empty: This part of the video feels a bit like a James Bond movie directed by Louis Bunuel. And then a SWAT team shows up.

So what does this tell us about the state of the Strokes in 2016? First, they are as derivative as ever. Second, their sound, which seemed to be moving into disco/synth-pop territory with 2013’s “Comedown Machine,” has returned to the mix of guitar fuzz, blurred vocals, and catchy melody from their first recordings. In a period almost twice as the Beatles recorded, The Strokes have not really changed much at all.

Third, and most important, the band sound great and the video, despite its lack of originality, captures some of their spirit, halfway between goofy and too-cool-for-school. In the best of all worlds, the Strokes would also have their own individual musical vision on top of an appealing style, great hooks and tight playing. They’d be able to make a video that seems entirely their own.

But one thing the trial over Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven” and other controversies over song credits have reminded me is that despite the fights over individual riffs and melodies, the key is whether the new song creates its own reality and puts it across with conviction. The video has me wondering exactly what this reality is – the thing is all over the place. But the Strokes, it seems, have their mojo back.

Clinton’s pledge to forgive student debt of entrepreneurs, not average workers, will benefit the elite

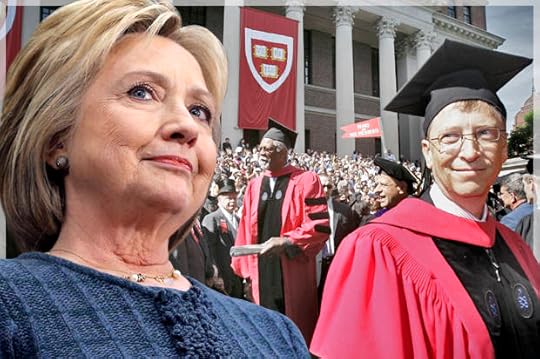

Hillary Clinton; Bill Gates at Harvard University's commencement ceremony, June 7, 2007. (Credit: Reuters/Brian Snyder/AP/Michael Dwyer/Photo montage by Salon)

Democratic presidential front-runner Hillary Clinton has pledged to help forgive the student loans of entrepreneurs and small business owners, yet has not made similar promises to help forgive the student debt of average workers.

Clinton released her Initiative on Technology & Innovation on Tuesday. It reflects her neoliberal, technocratic vision of the economy.

In the initiative, Clinton outlines her plan to “support young entrepreneurs.” As president, she says she would allow entrepreneurs to forgo paying their student student loans for up to three years, “so they can get their ventures off the ground and help drive the innovation economy.”

Moreover, “innovators who start social enterprises or new businesses in distressed communities,” Clinton adds, can apply for forgiveness of up to $17,500 of their student loans after five years.

Clinton has not made similar promises to help average working-class Americans with crippling student debt. In the education platform on her campaign website, she says she will allow Americans to refinance their loans at current rates, but there is no serious discussion of forgiveness.

At first glance, Clinton’s new policy might sound like a good idea, but, simply by virtue of how entrepreneurship works, it will inevitably disproportionately benefit the elite.

Entrepreneurs employ people; business owners have people who work under them. Clinton’s policy will help ease the student loans of these workers’ bosses, while employees are crushed under the enormous weight of their student debt.

At least 43.3 million Americans had student loan debt as of the end of 2014, according to Federal Reserve Bank of New York figures. This number has likely increased since then.

There is approximately $1.2 trillion of student debt in the U.S. today. The average American with student debt has $26,700 in loans to repay.

Furthermore, since the 2008 financial crash, student loans have continued to grow, even while other debts have declined.

Partially forgiving the student loans of small business owners is not going to cut it. It is nowhere near the solution that is needed.

An entire generation has effectively been indentured with voluminous debt that they are unable to declare bankruptcy on. Millions of average workers will fall through the cracks in these policies.

In fact, in the shorter version of Clinton’s technology initiative, she does not even acknowledge the employees of the entrepreneurs she pledges to help.

In the longer version, Clinton mentions employees just once, saying she “will explore a similar deferment incentive not just to founders of enterprises, but to early joiners — such as the first 10 or 20 employees.”

Note: Clinton solely pledged to “explore” a similar initiative for average workers — she made no promises to help them in the way that she has promised to help their bosses.

Clinton claims this entrepreneurship policy can benefit “millions of young Americans.” Yet one must ask: Does she really believe that millions of young people will start businesses?

Anyone who has tried starting a business knows it is very difficult, and it more often leads to failure than success. A staggering 90 percent of startups fail.

It defies reason to expect the more than 43 million Americans who have student loans to become entrepreneurs. This is approximately 13 percent of the total population; they can’t start business with a 90 percent failure rate in hopes of potentially having part of their student loans forgiven.

Elsewhere in her initiative, Clinton is much more modest in her goals. She says she “will support incubators, mentoring, and training for 50,000 entrepreneurs in underserved markets, while expanding access to capital for small businesses and start-ups.” A total of 50,000 is orders of magnitude smaller than hypothetical millions.

A significantly more comprehensive student debt relief program is needed — and desperately so.

Bernie Sanders, the self-declared democratic socialist opponent of Clinton, pledged to make public universities free for Americans — a policy that has long been implemented in many other industrialized countries.

Clinton merely pledged to “make debt free college available to all Americans.” She says she wants out-of-control costs to be contained, but expects students to work 10 hours a week to pay, and wants families to eat into their small savings too — at a time when 63 percent of Americans don’t have enough savings to pay for a $500 emergency.

Under Clinton’s education plan, she says the average American with student debt could save just $2,000 over the life of his or her loans. That’s not very ambitious.

At the heart of it, Clinton’s stategy to cater to the entrepreneurial, business-owning class reflects her neoliberal worldview. Her policies are quite Reaganite in spirit, reminiscent of his supply-side economics policies. Like Reagan, Clinton’s policies focus on the “job creators,” not the working class.

Perhaps this is not surprising, considering how Wall Street has thrown its weight behind Clinton. Financial executives have recognized how she plays ball; accordingly, more than half of Wall Street donations have gone to Clinton’s campaign.

Entrepreneurship itself is a thoroughly privileged field. “The most common shared trait among entrepreneurs is access to financial capital — family money, an inheritance, or a pedigree and connections that allow for access to financial stability,” explained Quartz’s Aimee Groth in a recent report.

University of California, Berkeley economists Ross Levine and Rona Rubenstein found that the majority of entrepreneur are white, male and highly educated. “If one does not have money in the form of a family with money, the chances of becoming an entrepreneur drop quite a bit,” Levine added.

The average cost to launch a startup is around $30,000, Groth reported, and more than 80 percent of funding for new businesses comes from personal savings and friends and family.

“We’re in an era of the cult of the entrepreneur,” she wrote, but “starting a new venture is the ultimate privilege.”

Clinton’s idea that innovators and “job creators” are the bedrock of the economy and need to be incentivized is fundamentally neoliberal and right-wing. It presupposes that there are superior economic minds, and that average working-class people are less valuable.

In recognition that entrepreneurs are overwhelmingly from rich families, and are heavily white and male, Clinton expressed commitment in her initiative to trying to diversify entrepreneurship and to encouraging women and people of color to be entrepreneurs.

Yet this still does nothing about the millions of average workers who struggle to make ends meet, as their wages stagnate, their meager benefits are cut and their debts multiply.

Clinton says she wants to “increase access to capital for growth-oriented small businesses and start-ups, with a focus on minority, women, and young entrepreneurs.” She pledges to “diversify the tech workforce” — but all this does is make the economic elite more diverse.

This does not deal with fundamental, systemic problems of inequality and exploitation — the kinds of inequality and exploitation that are targeted by socialists like Sanders, and by countless other activists around the world.

This is the quintessence of Clinton’s worldview: She wants to strengthen and diversify the technocratic corporate ruling class, while average workers continue to be exploited.

Uncoincidentally, then, much of the language in the rest of Clinton’s technology initiative consists of neoliberal doublespeak.

She pledges to “build the Human Talent Pipeline for 21st century jobs” and to “spur entrepreneurship and innovation clusters like Silicon Valley across the country.” Silicon Valley, a kind of technocratic dystopia, is, for Hillary Clinton, a role model that should be replicated on an even larger scale.

There is constant talk in the initiative of STEM (science, technology, engineering and math). Clinton says her “New College Compact” will dedicate $10 billion in federal funding for students to pursue nanodegrees, computer coding and online learning. But there is virtually no discussion of the importance of the social sciences, yet alone of the humanities.

Technology and innovation, for Clinton, are purely corporate fields, not social ones.

Her policies constitute yet another entrenchment of an age-old strategy: socialism for the rich, and capitalism for the poor.

Writing a novel about Jews set in 1942—without Hitler: “Once you mention Hitler’s name, his mustache is in the room. The stakes change”

Emily Barton (Credit: Penguin Random House/Greg Martin)

Emily Barton’s new novel, “The Book of Esther” (Tim Duggan Books), sounds like a slightly skewed coming of age novel. One day, out riding her mechanical horse, sixteen-year-old Esther sees war planes with foreign insignia swooping low over the refugee camp she is clandestinely visiting. Where are we and what year is it? Who are these refugees? And what is a mechanical horse? As with Barton’s previous novels, “The Testament of Yves Gundron” (2001) and “Brookland” (2006) (about the coming of modern technology to an society untouched since the Middle Ages and the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge in colonial Brooklyn, respectively), this is Barton’s world and we’re all just living in it.

Esther is the daughter of a chief advisor to the leader of Khazaria, a Jewish empire between the Caspian and Black Seas. The refugees are also Jews who have fled a menace in Europe; it is August, 1942, and the Germans are marching to Russia. And mechanical horses are exactly what they seem: an ingenious response to mechanized warfare, invented and designed by tribal warriors used to fighting over great distances on the steppes. Esther takes it upon herself to save her people from the German threat, leaving her father and fiancé, journeying to a legendary village of kabbalists in the dessert, and ultimately leading an army of golems and renegades.

Barton is an Iowa Writers Workshop grad, a Guggenheim winner, and has taught at institutions ranging from Yale to Columbia to Smith. But over lunch, she’s my nice Jewish girlfriend out in Manhattan for the day. Our conversation ranged from second wave feminism to research techniques to the use of scrunchies. The salads were delicious; I cut out our long digression about baby wearing techniques.

You always immerse yourself in these half-real worlds. Do you do that on purpose? Where does that part of your imagination come from?

That may be from wanting to write about the historical past as it connects to the present without being limited by mere fact. Wanting to be in a space that’s at once historical and imaginative.

How is that different from more conventional historical fiction?

It’s exactly the same thing — in a slightly different register. Part of what I’m intrigued by is technologies that never existed, and the ways in which things that did not come to fruition sometime in the past might have come to fruition.

Are you a tech or mechanical geek? Are there a lot of David Macaulay books in your house?

We have many David Macaulay books, and I am a bit of a mechanical geek. I was the kid who took apart all the appliances to figure out how they were wired, and then sweating, afraid of breaking them, put them back together.

Your books always have this meeting of speculative technology and feminist rewriting of history.

You grew up with a second wave feminist mom, too, right?

Hell yeah.

I’m so grateful for everything they did, both for our liberation and for the liberation of humankind. At the same time, I feel that they promulgated a narrow view of what it meant to be a strong woman. In my own work, I try to convey fully realized women characters, and also all kinds of characters who are nevertheless imperfect. People who have odd predilections, people who have flaws, people who do not always make the best decisions for themselves. I want to be clear that a female character — exactly like a female person — can be strong and be herself without being a paragon of virtue.

They are also allowed to be sexual. Esther is a healthfully sexual person, though her that drive theoretically conflicts with her heartfelt religiosity.

In different drafts of the book Esther was different ages. She fell out sixteen because it seemed old enough to have the wherewithal to do the things she wants to do, but young enough to be naive enough to do them. And not to be married off yet, because in this culture she is clearly going to be married by the time she’s seventeen. A sixteen-year-old person, regardless of her cultural milieu, is a sexual being, whether she’s given language for that or permission to explore it. The book is not about Esther as a sexual person, or how her particular sexuality or gender expression takes place, but I wanted that to be a fully integrated part of her character.

I love that she and her bashert (“chosen person” and betrothed) Shimon are so attracted to each other. They want to sleep together and make a married life together. Yet, her attraction for other people — specifically the mysterious and angry kabbalist Amit — doesn’t preclude that.

I worked against that narrative of the chosen spouse being the wrong person. That’s a cliché. Love matches aren’t everything (although I feel lucky to have a nice one). It’s considerably more interesting if Esther really likes her arranged match.

I have to interrupt here to report that the author is putting her hair up in a scrunchie.

I like scrunchies! It’s silk. I buy them on etsy — I’ll send you a link.

They don’t tear your hair if you have curly hair!

Exactly. Let’s see, arranged marriages… One of my friends felt like Shimon is the captain of the football team, but Amit is the rock ‘n roll guy who is different but equally attractive.

Amit drove me crazy.

I’m sorry.

No, I mean, Amit had a lot going on. (Small spoiler alert.) He joins the kabbalists in order to use their magic to work out his own gender and sexuality.

True. Although: magic is magic. The magic is there and exists in the universe of the book.

Esther gets different magic than she asked for. But then, everyone does. The golemin become more sentient than anyone expects, as when they pray, passionately.

Golems are what Jewish people have for magic. Once there were mechanical horses — and there were mechanical horses from day one — there had to be golems, if it’s a Jewish book. Esther and other characters think a lot about what the mechanical horses and the golems and also Nagehan the passenger pigeon are. Where does their being-ness end and their machine-ness begin, or the other way around? I guess I’m asking the same thing I’m always asking: we’ve made all this stuff, what does it do to our souls? How does it harm them? How does it enrich them? How does it help them grow? I don’t believe that technology has a positive or a negative value; we’re just living with it. But we have to think deeply about how it affects us.

You just said, “if this was going to be a Jewish book.” Is this a Jewish book?

Of course it’s a Jewish book! It assumes a Jewish worldview and then provides contextual detail. I want any reader to be able to enter the book and enjoy it, but I didn’t want it to be told from the point of view of a minority religion. Judaism is the majority religion and the worldview in this world. I hope that readers who are not Jewish will also appreciate and relate to it. I’ve spoken to a couple of early Muslim readers, who feel immense kinship with it, because of the environment, and because Judaism and Islam are brother and sister, and there’s a lot that’s recognizable.

The heartbreak of the book for me was that even in this fictional and magical world, the Holocaust was still happening. Our beloved characters – even the golemin, their whole world — were all still doomed.

I don’t see that they’re all doomed. That’s a reading that’s available to you.

I don’t mean to be totally pessimistic, and be like “They’re all gonna die!”

You can be pessimistic.

Okay. Let’s say I’m optimistic. The book could raise the question, what if the Holocaust hadn’t happened? I mean not even questions of population. We would have a world of Yiddish literature. We would probably have been spared “Portnoy’s Complaint.” Would we have gotten Grace Paley? I like to think yes…

[Giggle, subject change.] Would we have right of return to Ashkenaz? Probably. It could be a nation state. We could go live there.

You write a whole book about Jews in 1942 and never mention Hitler’s name.

Once you mention Hitler’s name, his mustache is in the room. The stakes change. In the novel I have written, it’s still possible that whatever gigantic fascist juggernaut is moving across might not be Hitler. That’s very important to me, because Hitler and the Holocaust are so loaded. It’s such a hard thing to write about. Once you really let Khazaria exist in actual Europe in August of 1942, there are many difficult questions that I don’t think a novel is the forum to answer.

Esther’s home is in Europe, not the Fertile Crescent, not the Middle East. Which means you were able to write about Jewish identity without writing about Israel/Palestine.

Yes. Though I do feel that one of the questions the book may raise for readers is that if there had been an autonomous Jewish state in Western Russia for fifteen hundred years, how does that affect the development of the modern state of Israel? I don’t have an answer to that question, but the existence of this nation would have a geopolitical consequence.

Can you tell me about your research process? I know you’re a heavy researcher.

I’m a canny researcher. My aim in research is to come up with enough plausible detail to make it seem real, not to enmesh myself or mire myself in research. Research is such a pleasure that you can just fall down the hole of it for years at a time, and I don’t want to do that. With “Brookland,” what has been funny to me is I get these letters… I got one from a Luquer descendant [there is a Luquer family in the novel], and he said, “We’re all redheaded, and I don’t know where you got that information about our family, but I’m so touched and moved.” I’d made it up! With “Brookland,” I took the 1767 census map, which I do know how to find, and then I took all the names off it and made characters out of them. I read enough to feel comfortable with the names and landscapes and morals of the time, and I knew how many taverns there were and things like that, but I didn’t spend years on it.

The research for “Esther” was a little more complicated, because not that much is known about the historical Khazars. They vanished from history somewhere in the tenth to eleventh century, and they didn’t leave written records. The American scholar, Kevin Alan Brook wrote “The Jews of Khazaria,” which is a definitive history. Arthur Koestler’s book “The Thirteenth Tribe” sent everyone into a tizzy in the ’70s, because he argued that Ashkenazim are actually Khazars, and that we bear no relationship at all to the historic Jews. Realistically, we probably are, but I also feel that I have some connection to the Judeans in the dessert two thousand years ago.

Michael Chabon’s novel “Gentlemen of the Road” has Khazars in it. I wrote to Chabon to ask him if he had any sources I didn’t know about. He wrote back and he said, “That’s what so great about the Khazars, is that you can just make this shit up.”

It’s been contested territory as long as recorded history has existed, and that’s part of the reason I wanted to write about it. This tribe stormed in from this place and then took it over, and then that tribe stormed in and… It’s contested, it’s roiling, it’s busy, it’s polyglot, and that’s interesting to me.

Let’s talk about process a bit more. I had this idea I wanted to talk to you about motherhood and writing and what children do or don’t do to your writing, especially since you and I talk a lot about that privately. Though we also often talk about clogs. You have two children: an eight-year-old and a three-year-old. So…

Well, one thing you might notice is that I published “Brookland” in 2006 and that I’m publishing this book in 2016.

I might notice that, yes.

There is another reason that that happened, which is that from 2006 until the end of 2009 I was writing a different book. In the winter of 2009, I broke my wrist and was unable to type. The book was being written on the computer, and my husband Tom issued me a dare: could I write a 50,000-word potboiler by hand.

It turns out it was a five-year feminist steampunk kind of novel. Ie: one of your books.

When I set out to write it though, thinking I was going to write a 50,000-word potboiler by hand, it was enormously freeing because it didn’t have any pressure on it. But the question you were asking was about children. They are not intrinsically responsible for the first three or four years of how long it took me to get this book out into the world.

Five years seems like a reasonable amount of time to spend on a novel. You’ve also taught at like ten different places in that time.

Yes, it’s been enormously complicated. There have been times where I’m teaching – like this year – on three overlapping academic calendars.

I did two this year and it was insane.