Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 730

July 3, 2016

Behold, Brexit: The greatest political satire of all time

(Credit: Reuters/Reinhard Krause)

Forget “In the Loop.” Forget Michael Ritchie’s “The Candidate,” or Kubrick’s “Dr. Strangelove.” Brexit is the greatest political satire of all time. A jaw-dropping tale of how a powerful few convinced an angry electorate to shoot itself twice in each foot before asking whether or not that was a good idea, Brexit is the ultimate in political farce. And what’s astounding is that nobody seems to be taking credit for it, even though its satirical conceit is so complete. Just who is responsible for Brexit?

We can look to nicotine-fried hard-right fear goblin Nigel Farage as the man who instigated the EU referendum and got the anti-immigrant vote out with some glorious Nazi-inspired propaganda; to (soon to be ex-) Prime Minister David Cameron, who confidently agreed to the referendum to see off Farage’s Eurosceptic UK Independence Party only because he thought he’d win; and to cuddly yet violent former Mayor of London Boris Johnson, who elected to lead the campaign for Britain to leave the EU only because he thought he’d lose, albeit come close enough to a win that he could challenge Cameron for the PM role (when we Brits gamble, only whole nations will do as the wager).

Then there’s Jeremy Corbyn, the leader of the officially pro-EU Labour Party, who – a long-time Eurosceptic himself – deliberately sabotaged the Remain campaign; and apparent malfunctioning android Michael Gove, the Vote Leave campaigner who assured voters there was no need to listen to the experts who accurately predicted the economic crisis Britain now finds itself in. It was Gove who appeared before the press alongside Boris to claim ‘victory’ last Friday. Far from seeming like they’d just won the Westminster lottery, the pair rather looked like two hostages forced at gunpoint to assure their loved ones that everything was going to be fine. Now we know why, as we hear their campaign never even planned for the eventuality of a Brexit. Truly, this is a gallery of incompetents, caricatures that could only exist in comedy, none of whom will now lay claim to the financial and political firestorm that Brexit has left in its wake.

It’s probably difficult for anyone outside of the UK to understand why British voters would trust ones such as Boris and Gove to tear up a glorified trade agreement decades in the making. You really had to be in Britain prior to the vote to get a feel of the anti-immigrant, anti-fact atmosphere created by the most right-wing press in Europe. The likes of the Sun and the Daily Mail – the UK’s two biggest dailies – led the British media’s pro-Brexit charge, forever encouraging anti-EU sentiment and suggesting a barbarian horde of Europeans was coming to Britain to claim financial handouts and have a go on our National Health Service.

Now, having gotten exactly what they wanted, both papers are finally admitting to readers that Brexit isn’t necessarily going to make things better after all. Although, perhaps it’s this very chaos that many Leave voters really wanted. When he agreed to a referendum, David Cameron didn’t get that the British electorate were so disdainful of the powers-that-be that they were willing to explode a system they didn’t feel was working for them. Brexit is the people’s Gunpowder Plot, only this time the perpetrators have succeeded, not just in leaving Parliament in ruins, but in delivering a violent shock to the economy as well.

Not all Leavers are happy with the result. Already, many of those who voted Out are expressing heavy Regrexit, with some admitting they only cast a ballot for Leave in protest. Even those Leavers who felt confident in their decision were soon left wondering what the hell they’d just voted for, as the head Leave campaigners immediately began admitting every one of their key pledges was a lie. Lower immigration? Not really. A radical overhaul of Britain’s relationship with the European Union? Unlikely. More money for the NHS? Nah. By Monday, it seemed that all Leavers had voted for was an economic downturn. The Leave team have now wiped their website of any promises made, hopeful voters are forgetful enough that they don’t now turn to rioting in the streets.

Brexit will no doubt continue to provide apocalyptic entertainment for years to come. Britain’s vote to leave the EU will most likely shrink the nation (goodbye, Scotland! Et tu, Northern Ireland and Wales?), diminish its influence on the world stage and cancel London as a financial centre of the world. With the pound plummeting and $2 trillion in stock value wiped out in a single day, Leave-backing businessmen were regretting their decision from the get-go – like stockbroker Peter Hargreaves, who donated £3.2 million to the Out campaign, only to see his fortune shrunk by 19 percent as a direct result of Brexit by Monday, in what may prove to be one of the poorer investments of the year. More seriously, with many on the far right feeling suddenly legitimised by a vote to flip off Europe, xenophobic and racial abuse in the UK has risen by 57 percent since last Thursday, with US army vets and British-born BBC hosts now being subject to abuse unheard “since the ’80s.” In short, though Brexit may look like a glorious mash-up of “House of Cards” and “The Thick of It” from the outside, for those living through it it’s slightly more unsettling.

But, British as we are, it seems – having deliberately driven it into an iceberg – rather than putting a stop to this madness we’re electing to just go down with the ship instead. There are perfectly good lifeboats offering us a way off, but it seems our captains won’t allow it; it’s too late for that, because David Cameron, Boris Johnson and Michael Gove made promises – even if today they are cursing themselves for ever making them (especially Boris, who was just out-Frank Underwooded by Gove and lost his chance of becoming PM). It’s an absurd carnival. You still suspect that, one day soon, Johnson is going to take to a stage in full view of the British people and, with financial workers fleeing to the continent behind him, he’s going to exclaim: “The Aristocrats!” It would be an apt climax. At least then it will feel like there has been some point to all this.

July 2, 2016

The “struggle” is not real: From tiny houses to my own lunch, poverty chic commodifies working-class life

(Credit: SAYAN MOONGKLANG via Shutterstock/Salon)

I was returning to my desk with my freshly heated lunch when a coworker passed me. “What is that?” she asked, motioning at my food. “Cornbread, pinto beans, collard greens, canned tomatoes, and chow chow,” I replied excitedly. “That looks like a struggle meal,” she said, crinkling her nose in what appeared to be judgment, disgust, or both.

“‘Struggle meal?’” I asked, unfamiliar with the phrase. “Yeah,” she said. “A struggle meal is what you eat when it’s the last day before you get paid and that’s all you can scrape together. You can’t afford to go get Chipotle,” she giggled. “Or if you do,” she continued, “you can’t get the guacamole, because it’s extra.”

It was an innocent exchange with a coworker, but her words stuck in my craw for weeks.

As a working-class woman who’s managed to secure a few white collar jobs, I’ve come to expect some real differences between me and my coworkers, but this one was new to me. I’ve been acknowledged for having a thick Southern accent, using so-called colloquialisms like “y’all” and “yonder,” and for nearly always bringing, rather than buying, my lunch. But this ostensibly innocuous exchange stung. It hurt because these were the foods my parents, especially my mother, worked hard to make for us when I was growing up. It hurt because those are the foods that sustained me as a child, that I still love eating today. They tie me tangibly to the rural land I left behind for a city I’ll never call home so I could have a better chance at making a living for myself than I would have if I’d stayed in my small hometown (one that, at one point over the years, suffered the highest unemployment rate in the state).

Ultimately, though, it hurt most because the term encompasses yet effectively erases what my parents, and to a lesser extent, I, did — and still do — to survive. We struggle.

Interestingly enough, a phrase that includes what we did — financially struggle — actually erases the lived experiences of people like me and my family whose struggles aren’t limited to being able to access our expendable income for frivolous items like takeout food. From the vantage point of someone whose family grew and killed most of what we ate out of financial necessity, the kind of struggle implied in a “struggle meal” is not a real struggle at all, but more of an irritant or inconvenience.

It goes beyond just this term, though.

The term “struggle meal” seems to me to be related to the phrase-turned-hashtag, “The Struggle Is Real.” For anyone unfamiliar, Urban Dictionary defines “the struggle is real” as “a (generally) ironic saying often used in place of the saying, ‘first world problems.’ With irony, it has a comical effect of dramatizing a non-critical, yet undesirable situation.” Popular iterations of this phrase often relay the “struggle” as running out of shampoo before running out of conditioner, or of having to deny oneself a donut because swimsuit season is approaching. With rampant social problems like inaccessible health care, childhood hunger, and homelessness (just to name a few) existing in the developed world, it’s apparent that there is not enough irony to make the incongruence between the phrase and people’s real struggles to survive funny.

A cursory search for the phrase online reveals not only its ubiquity, but its fundamental ties to affluence and financial stability. There are any number of internet memes and items available for sale, such as coffee mugs, iPhone cases, and hand-lettered art pieces to be displayed in people’s home offices that indicate for whom the “struggle” is real. These items belie, of course, the reality that roughly twenty percent of Americans — nearly 60 million people — lack access to the internet and that another 45 million Americans live below the poverty line. The “real struggle,” as explained by this phrase, is one confined to aesthetics and whimsy, not survival.

It’s the linguistic equivalent of the ways mainstream society appropriates and commodifies working class aesthetics, like Mason jars, sweatbands, beards, thrift store clothing, and the like. This troubling trend even spills over into housing, with affluent folks trying on small, mobile houses from the Tiny House Movement as “proof”’ of how enlightened they are, having pared down their possessions to live more simply and happily. The crucial difference in these cases is that those who appropriate the items intrinsic to working class life and survival do so out of choice, rather than necessity.

As accessories, these items symbolize a part of the fend-for-yourself culture — of any race, ethnicity, or region — that has become strangely popular in mainstream society. Using or wearing these working class accessories lends the wearer a kind of can-do credibility that doesn’t come with white collar office attire — a rustic cachet without any of the hassles and struggles that comes with the lifestyle. Likewise, the people who use this language typically appear perfectly self-reliant (yet they are the ones who enjoy class, race, and, in the case of men, gender) privilege that is incongruent with the self-reliance working class people have to utilize in order to survive.

The linguistic appropriation and fetishization of “struggle” and its hashtag is particularly egregious when you stop to think what good it could actually do. Social media is replete with meaningful social activism, yet the terms I’ve identified are a pale facsimile. Utilizing a word that denotes hardship in a way that essentially parodies it is hurtful and offensive to those people whose lives are defined by real struggle; it also functions to neuter the word and divorce it from its power. Herein lies the most dangerous aspect of this linguistic cultural appropriation: it can render words ineffectual and wrest power from the speaker.

Many social theorists have analyzed the relationship between language and social power; perhaps most notably, French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. He argued that language was not only a means of basic communication, but a means of power as well. To this end, his analyses include word choice, accents, and dialects. One of his most well-known treatises on the subject, “Language and Symbolic Power,” explores the implications of the fraught relationship between language and power.

Whenever language is used, Bourdieu argues, speakers utilize their “accumulated linguistic resources” (or accrued knowledge about communication) and adapt their words according to their audience. This means every linguistic exchange, regardless of how minor or major, both relays and reproduces the social structure in which it exists. This is particularly salient in the political realm, because words — written or spoken — help determine action and power.

While hashtags and popular sayings about “struggle” may seem insignificant, they take place in a social context where words both give and deny power to speakers. In this case, taking a word whose very definition is one of difficulty and using it to create a flippant, casual meaning has the cumulative, dangerous effect of altering its original meaning — particularly as this relates to politics and power. This is perhaps most dangerous among the youth, who are most likely to utilize these types of communication and whose accumulated linguistic resources are likely not as sophisticated or fully-developed as older generations.

While cornbread, beans, and collard greens may be considered a “struggle meal” to some, to the people who were raised in families where it was that or not much else, they’re actually considered to be an accomplishment. After all, filling the bellies of you and your family, while consistently struggling to do so, is what helps us make it another day — and that is how many working class people define success.

Every day we’re hustling: Why we love “hustlers” — but not “whores”

Aziz Ansari as Tom Haverford in "Parks and Recreation" (Credit: NBC/Colleen Hayes)

We seem to be in the golden age of hustlers. From tech bros to politicians, everyone’s a hustler these days. The infamous hustle is sprinkled across social media bios, WIRED headlines, and marketing campaigns. WeWork’s office wallpaper is dotted with “the hustle.” This is the same office that houses the self-proclaimed “Voice of Hustlers” (I know this, because I’m co-founder of that company). Chevrolet ran a #FuelYourHustle campaign in April, and even FLOTUS be hustlin’ at SXSW.

Simply put, a hustler is someone who knows how to get shit done. But in the past, a hustler was most often a male sex worker, or anyone (usually a man) who’s a bit of a swindler.

One could say “hustler” bears some semblance to the feminized “whore,” another word loaded with connotations around money, fornication and unsavory business practices. Except, while we’ve been socially conditioned to want to be hustlers, we’re wildly uncomfortable being whores. Imagine if Forbes’ Andy Ellwood wrote articles about mastering the art and science of whoredom, as he does for hustle.

What do our words say about our stigmas? Pejorative ideas yield pejorative words, not the other way around.

Historians have found that “whore” might not have always been a derogatory word. And so our discomfort with “whore” is rooted in the problematic cultural aversion to women having sex outside of the perimeters of “good girl” relationships, particularly in the heavily stigmatized world of sex work. It’s a different story for men.

A look at the history and etymology of both “hustler” and “whore,” along with previous attempts at reclamation, reveals a correlation between our changing (and unchanging) views of sexuality and sex work — and the problematic ways we have, and continue, to view both.

The History of “Hustle”

Despite being a younger word, the meaning of “hustler” is perhaps even more slippery than “whore.” But it holds a pattern of describing distasteful behavior.

It probably originated in the 17th century in the general sense of “shake” or “toss.” By the 19th century, a hustler was a violent thief, or a ruthless businessman. In 1884, it adopted the meaning of “energetic in work or business.” It wasn’t until the 1920s that it adopted the meaning of male sex worker.

At the same time, writers seemed to start using “hustler” more liberally. Its use skyrocketed in the mid-1960s, peaking in the mid-1970s. This was the era that brought us “Midnight Cowboy,” Robert Mapplethorpe, and the gay culture magazine Drummer — which, according to the magazine’s former editor-in-chief, Jack Fritscher, was “the first gay magazine to report on, encourage, and glorify hustler culture as a valid ‘participatory fetish style’” in the pre-Grindr era.

Fritscher says media, art and film continue to be catalysts for change. “Art always drives people forward. It liberates your vocabulary,” he says. “Liberation was caused by our dramatists and our screenwriters, washing these things out in our literature and hanging them up so people get used to them.”

The “hustler” archetype has experienced a steady, exponentially positive, and — despite its deep roots in gay culture — heterosexual treatment in the media. Hustler magazine launched in 1975, as a more graphic version of Playboy. It boasted a circulation of 3.8 million in 1976, and while that number declined significantly in subsequent years, the magazine is arguably the mainstream prototype of heterosexually lensed “hustler” as aspirational, rather than derogatory.

On the big screen, Richard Gere brought male sex work to life in “American Gigolo.” But the film is a departure, not only from how female sex workers are portrayed (read: that other movie starring Gere), but also from the reality of male sex work.

“When we see mass media representations of male prostitution, we see the man who lives the ultimate male fantasy. He’s so good in bed that women will pay to have sex with him,” says Kirsten Pullen, author of “Actresses and Whores: On Stage and in Society.”

Fritscher talks about a segment of straight, married men who hire straight (or straight-acting) men for unemotional “body sex.” But in a heteronormative society, we rarely — if ever — witness this hustler dynamic in the media. Which is perhaps why the word has evaded its stigma. Our collectively-sculpted perception of male sex work matches heterosexual dynamics we not only accept, but often glorify: woman-hires-man or man-pimps-woman.

Our filtered perceptions dilute our vocabulary. In the case of “hustler,” the word was stripped of its negative connotations, leaving it with an exclusively positive and glorified connotation. In hip hop, a hustler went from a drug dealer (Ice T’s “New Jack Hustler” in 1991) to a blanket term for masculine, yacht-life ambition (Rick Ross’ 2006 hit, “Hustlin,’” later sampled in LMFAO’s “Party Rock Anthem”):

Mo’ cars, mo’ hoes, mo’ clothes, mo’ blows.

Everyday I’m Hustlin’

And yet, for whores, little has changed.

The History of “Whore”

The word seems to have originated in the 12th century from the Old English “hore,” meaning dirt or filth.

But this negative connotation might not be representative of the word’s roots. Author Iris J. Stewart points out in her book “Sacred Woman, Sacred Dance: Awakening Spirituality Through Movement and Ritual,” that in ancient Egyptian and Greek religions, several goddesses were called Hor or Horae. According to Stewart, early versions of “whore” also might have referred to dancers or even to “idolatrous practices or pursuits.”

These were times when prostitution was sacred and women’s sexual power was considered to be a channel of divinity. It seems that it wasn’t until patriarchal religions emerged, carrying new taboos against female sexuality, that “whore” was buried in soil.

By the 16th century, “whore” was commonly applied to any unpopular woman, but it also described a women who had sex for money. It remained a general term for contempt through the 19th century.

Thanks to Google’s Ngram function, we can see that the printed use of “whore” peaked in the mid 1700s. After dipping in the Victorian Era, it’s been steadily climbing since the 1920s and is currently peaking again. I’ll point out that the 18th century, the 1920s, and today are all notable periods of sexual liberation for women.

Save for subculture slang, modern colloquial language pegs “whores” as promiscuous women and female sex workers. It’s also used more generally to describe a sell-out, particularly in politics. Dr. Paul Song’s “Democratic whores” comment at an April Bernie Sanders rally was not received well by Hillary supporters and feminists.

There’s no doubt that “hustler” has experienced a more fluid journey than “whore,” at least in recent decades. But again, it goes back to the undercurrents of cultural acceptance.

At times in its history, there have been attempts at reclamation. In “Actresses and Whores,” Pullen discusses the “whore” label that society often projected onto 19th-century performance artists. “This was a way to put a label on them to limit their economic and social power. There weren’t a lot of other jobs,” Pullen says.

But some actresses, like Mae West and Lydia Thompson, embraced the label and played up the hypersexualized “whore” archetype in their performances. In an excerpt from her book, Pullen says, “by turning the accusation on its head, these women provided new images and new words to construct female sexuality.”

A few centuries later, performance artists are again reclaiming the label. The Poetry Brothel is an immersive poetry experience set up like a fin-de-siècle brothel in which patrons receive private readings from the self-proclaimed Poetry Whores. Stephanie Berger, “The Madame” and co-founder of the Brothel, says she finds the whore metaphor empowering.

“By reclaiming ‘whore,’ we are undermining those who try to use it as if it were a dirty word,” Berger says.

Like the Poetry Whores — some of whom, according to Berger, have been sex workers in the past — sex workers themselves have worked to reclaim the word. In fact, many of them wear it proudly.

But the word can never shed its negative connotations until we embrace destigmatization of female sexuality and decriminalization of sex work.

Ultimately, the more comfortable we are with our sexuality — whether in the context of a committed relationship or a profession — the more freedom we will have to put resonance behind a sexually loaded word.

“We need to get to the point where [women] can reject it or embrace it,” Pullen says about “whore.”

This makes the case for what’s really important here: choice. Being a sex worker is not intrinsically empowering. What’s empowering is the act of choosing to not be seen as a victim, of not feeling shame. We can look to ancient religions as an indicator that whoring does not have to be negative.

There are business executives who “hustle” their way to depression. Yet, hustling has grown into a celebrated phenomenon. Man or woman, we’re encouraged to be ruthless, to “lean in,” to work 70-hour weeks, neglect vacations, and ferociously hit the pavement. For some people, the pavement is the bed. And as PJ Harvey says, “the whores hustle, and the hustlers whore.”

The waves of sexual liberation throughout the centuries parallel our comfort with — or at least use of — the “hustler” and “whore” labels. However, the overall perception of sexuality is more important.

“Hustler” has shed much of its negative connotation, because men having sex and men making money are concepts that have always been culturally accepted. This is not yet the case for women, for whom there remains a collective neurosis around sex and slut shaming.

Is there a significant value in redefining “whore” as “hustler” has been redefined? Maybe not. But if there comes a day that whoring is as illustrious as hustling, I think it would be representative of true progress. And certainly there’s value in redefining our legal and emotional standards for whores. Quieting our stigmas quiets the significance of words. Actions speak louder, anyway.

Twin campaigns: My secret mission to get pregnant while covering the presidential election

A photo of the author (lower right), covering Chris Christie's visit to Mexico City, Sept. 4, 2014. (Credit: AP/Rebecca Blackwell)

Presidential campaign coverage is a reporter’s dream and a functioning adult’s nightmare. One 16-hour day fueled by granola bars, airplane peanuts and deadlines leads to the next, while clothes in dire need of laundry are worn again.

“Did you bring your mittens? Do you have enough snacks?” read a memo the Iowa Republican Party sent to reporters this year before its caucuses. “You never bring enough snacks and then you get cranky.”

But as a campaign reporter in a year like no other, I had an extra reason to be cranky: the stress and potential heartbreak of my secret campaign for a kid.

Zany work schedules interfere with family life for countless professional couples — even the youngest and healthiest — but my husband and I needed medical help. Waiting for an entire election cycle to pass would have vastly decreased my already diminishing fertility. Our backs against a wall, we went ahead with what medicine could offer to help facilitate one of life’s very oldest processes.

So, from the ramp-up to Iowa until the early primaries this year, I attempted to schedule assisted reproductive treatments around campaign travel, rolling the dice that my ovulation would sync up with the Republican field’s schedule.

Covering the presidential field and tackling fertility in tandem was mad. It was also funny, exhausting, isolating and strange. And it offered yet another example of how shoehorned parenthood has become into our high-paced careers, leaving science as our crutch after years spent establishing ourselves.

My husband and I first tried the old-fashioned way. Everyone who winds up in this boat does. We had met just before New Year’s Eve in 2013, moved in together the following July, and married last fall (I have fond memories of folding ceremony programs while watching September’s Republican debate). I experienced the thrill of ditching methods used to prevent birth before our wedding, and the sorrow of realizing nature wasn’t going to yield one months later.

This lead to the alt-reality phase. I started in on weekly acupuncture sessions. I went to an herbalist and drank down cups of brown, medicinal mud. An immaculately dressed Manhattan naturopath dispensed comforting advice, along with creams, pills and tinctures that cost $446.65. She told me to sit under a full moon and bathe in its fertile light. I suspended my reporter’s skepticism to do all this — for no tangible results — as the prospects of infertility at 37 years old drove me batty.

Eventually, a fertility clinic and a blood test quickly pinpointed the problem: my estrogen was so low I should be getting hot flashes already. Without hormones flowing, I couldn’t ovulate. Without an egg released, I couldn’t get pregnant.

Dr. Glenn, my affable fertility doctor, who indulged in pastrami from Katz’s Deli during weekend clinic shifts, put me on courses of drugs to try to induce ovulation. If it worked, we could go for Intrauterine Insemination, or IUI. This was a more sophisticated — and costly — turkey baster method, complete with a $350 sperm wash that was supposed to increase potency. If three rounds of that didn’t work, off to In-Vitro Fertilization we would go.

Time ticking, I started in on Clomid, a drug that tricks the body into going into hormone production overdrive, to stimulate follicle production. My first round of drugs in October was a dud, so the clinic tripled the dose. I took the drugs for five days, went to my fertility clinic in the far reaches of the Upper East Side most mornings for blood work and an ultrasound — or “monitoring,” in clinic speak — and hoped Dr. Glenn detected progress. If a sufficient number of follicles bore mature eggs , I’d return the next day to trigger their release with an injection and then get inseminated 24 hours later.

In November, I got the green light. In a sign of things to come, I had to squeeze the trigger shot in before going to cover a two-day politics powwow in New Jersey immediately after. I sat on my wound for two hours on a Greyhound bus to Atlantic City, then took a 6:30 a.m. bus back the next morning for our first IUI attempt.

Having scheduled an appointment for a pregnancy test on Dec. 3, I began the terrible two-week wait to see if sperm met egg and managed to stick around. This is when campaign work was a healthy distraction. The more time covering Republican candidate Chris Christie’s claims he would shoot down Russian planes over Syria, beat Hillary Clinton’s “rear end” in a general election or expel Syrian orphans coming to the U.S., the better.

But by the end of the two weeks, my body let me know there was no need for a pregnancy test. Science was great, but the chance of the IUI method working at my age was 10% a cycle. Carly Fiorina was polling higher than my odds at that point.

Blindly determined, we moved on to the next round. On the up side, the drugs kept stimulating follicle development. Less ideally, they also made me hallucinate. Lights danced around the bathroom mirror in the morning and a blurry computer screen spooked me as I tried to read early-morning campaign news. The visual flickering typically subsided later in the day, but I had several white-knuckle drives on the campaign trail as street lights blurred along narrow, unfamiliar New England roads. I squinted, clung to the steering wheel and collapsed when I finally reached my hotel.

“Are visual problems common on these drugs?” I asked Dr. Glenn.

“They can be,” he said. He offered to discuss other types of drugs down the road.

I never brought it up again. In the hierarchy of needs, getting pregnant took rank over maintaining one of my own five senses.

After the second IUI and another trying two-week wait, we discovered the latest round hadn’t worked. Later that same day, a chatty beautician was applying foundation to my face in MSNBC’s makeup room for an appearance on “Meet the Press Daily.” I managed to smile and say something semi-smart about the state of the race that night.

This was becoming a strain. Day after day I would run to 7:30 a.m. monitoring appointments, only to arrive at my office desk two subways and a Band-Aid later to an inbox overflowing with campaign announcements. My travel was becoming more frequent, making it hard to link up my fertility cycle with the New Hampshire campaign schedule that increasingly determined my whereabouts.

My main candidates this election cycle were Donald Trump and Christie — a focus I came to think of as the loudmouth beat — and New Hampshire was prime territory for both. Christie had basically moved to the Granite State, a smart move, as the New Jersey Republican was one of this year’s best retail politicians. New Hampshire voters are a demanding lot, and the ebullient governor generally enjoyed the back and forth. He took rounds of questions at two-hour town hall meetings at veterans’ halls and working-class bars, tiring out his much younger aides. He sipped a Bud Lite with football fans deep in New England Patriots country while his wife chewed on chickens wings by his side.

Trump did a handful of choreographed diner stops and two town hall meetings, but he had no interest in glad-handing or kissing babies. New Hampshire voters didn’t care. They lined up for his rallies and brought copies of “The Art of the Deal” in the hopes he would sign them. His controversial campaign manager at the time, Corey Lewandowski, was a New Hampshire man, and he’d staked his name on winning the state, at a time when Trump’s nomination wasn’t inevitable.

One bitterly cold New England weekend in January, my highly choreographed pregnancy-and-politics dance went for a spin. It nearly fell flat on its face.

I caught an early flight out of New York after navigating the morning bathroom hallucinations. My travel bag contained enough prenatal vitamins, ovulation monitoring sticks and fertility drugs to get through the weekend. We were on IUI attempt number three, with IVF just around the corner if that failed.

As with all of these trips, you are wired the minute you land, pick up a rental car and orient your GPS. I covered seven events and filed four stories across those two days. My “offices” included a Keno parlor, the back of a smoky civic hall and a basement NFL watching party.

The trail afforded plenty of vignettes to bring home to curious friends. I sat with Christie on his campaign bus with his wife and four children as he confidently assessed his bid in saying, “I am good at this.” I sat with Trump at a booth in the classic Red Arrow Diner in Manchester as he ordered a hamburger covered with fried macaroni and cheese, then devoured it plus fries on the side.

But on it went. Parachute into a town, talk to lots of voters, look for candidate news on the stump, find a cafe with a power outlet and space to work, and drive to the next new town: Epping, Hooksett, Derry, N.H.; Brooklyn, Ankeny, Marion, Iowa; Vienna, Girard, Niles, Ohio.

The pace left little time for food, rest or speed limits. I passed countless curiosities while on the trail — the Cedar Waters Nudist Park in Nottingham, N.H.; the Danish Windmill Museum in Elk Lodge, Iowa; a barn roof emblazoned with a huge confederate flag along Rt. 77 in Ohio. But seeing this campaign circus up close in a year was the real draw. And after a campaign swing, returning to one’s own bed couldn’t be sweeter.

Back to that New Hampshire weekend. I was finishing up my last story over a tall mug of coffee at Cafe Reine in downtown Manchester when an email arrived from my editor. Trump was holding a campaign rally Monday night in Massachusetts, she wrote. Could I extend my trip and cover it?

Absolutely. Trump was speaking in Lowell, Mass., once the cradle of the Industrial Revolution in the U.S. and now a blue-collar backwater. Protests were planned, and even before his rallies in Chicago and San Jose set new bars, for unrest,t, anti-Trump activists were as exciting to cover as his rowdy supporters.

It took a few beats to realize that my flight change wasn’t the biggest headache I had to confront. I had brought one dose of Clomid, not two.

Precision is surely key in all medicine, but assisted reproduction is particularly regimented. Swallowing hormones one night and skipping the next wasn’t an option. As I hustled to a Christie national security speech, I called my nurse. “Could you FedEx me the three pills I need tonight?” I asked, breathing heavily and stalker-like into her voicemail, my hands frozen in fingerless gloves. “Can I skip a night?”

I waited, returned to work and worried.

Those hours in Manchester waiting for my nurse to call were a reminder of the private angst for those struggling to get out of the pregnancy gate. Rather than swapping family stresses in an office cubicle, I was furtively trolling fertility message boards that offer new sources of anxiety as often as comfort. You seek out friends in the same sad boat to whisper about the latest results, but the boat feels comparatively small.

My nurse, Hannah, called back as Christie took thinly veiled swipes at Trump — the candidate he would later endorse — dubbing him “entertainer-in-chief.” We finally connected as I ran to the governor’s next town hall meeting at a school in Concord. “We can call in an order for you at a pharmacy up there,” she said calmly.

An hour later, I was the woman with the wild-eyed look at the Manchester CVS. The line was long, and the woman ahead of me was dropping a mountain of prescription bags into her walker. The Trump rally start time was getting dangerously close, and I nervously scrolled through Twitter as the clerk explained that the Monday after New Year’s Eve was a crazy day for pharmacies.

I made it to Lowell, drugs in hand. It was nine degrees out that night. The Merrimack River had frozen. Regardless, thousands of Trump fans queued up outside, and the college students and other protesters gathered in an improvised “free speech zone” marked by a flashing LED sign. Reporters were pushed into a metal pen that was the hallmark of the campaign’s approach to the press.

A jumbotron at the Tsongas Center arena flashed family pictures of Ivanka, Eric and Don Jr. as Aerosmith’s “Dream On” and “Music of the Night” from The Phantom of the Opera played at ear-shattering levels. I regretted not adding earplugs to my travel kit.

“You are tough up here. There are people standing outside for hours in the cold,” Trump boasted. Fans stomped their feet on the cold floor.

The chase for the presidency and pregnancy share some things in common. They are acts of bigger purpose with strong elements of ego. “Make America Great Again” translates roughly to “My kid will be an awesome gift to society.” Both are fueled by faith and audaciousness, belief and chemistry, money and timing. They are exhausting, humbling and at times humiliating. And one has to ask at times: Why are we throwing so much money after a miracle? Is this how the best president, or child, is conceived?

Perhaps my case of juggling work and conception was extreme. But given the sheer numbers of those seeking help, I doubt it. There were 190,773 assisted reproductive cycles undertaken in 2013, nearly double the number in 2005, according to the Center for Disease Control. Those fertility sessions yielded 54,323 live births in 2013, more than twice the number in 2005.

The crowds assembled at my Manhattan fertility clinic for morning monitoring left few overstuffed chairs free. The reception line stretched to the elevators at times. Brown and black and white women all gathered in various states of anxiety, fatigue, boredom. We clutched our Starbucks cups, hung on to hope for dear life.

Days after returning from that cold January in New Hampshire, I was back among them. Dr. Glenn was amused by what little he’d heard about the most recent Republican debate, and pleased by what the sonogram showed about my follicles.

That Friday, Trump put up his second television ad, drawing on footage from his Lowell rally, where he declared that “we are going to take our country and we are going to fix it.” And I again bent over to receive a shot to trigger the eggs that had grown despite stress, sleeplessness and cold.

These twin campaigns for pregnancy and the presidency had another night in the stadium lights, their outcomes still a work in progress.

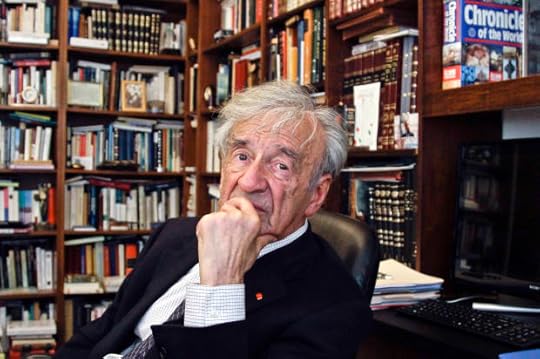

Elie Wiesel, Holocaust survivor and author, dead at 87

Elie Wiesel in 2012 (Credit: AP)

Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel, the Romanian-born Holocaust survivor whose classic “Night” became a landmark testament to the Nazis’ crimes and launched Wiesel’s long career as one of the world’s foremost witnesses and humanitarians, has died at age 87.

His death was announced Saturday by Israel’s Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial. No other details were immediately available.

The short, sad-eyed Wiesel, his face an ongoing reminder of one man’s endurance of a shattering past, summed up his mission in 1986 when accepting the Nobel Peace Prize: “Whenever and wherever human beings endure suffering and humiliation, take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.”

For more than a half-century, he voiced his passionate beliefs to world leaders, celebrities and general audiences in the name of victims of violence and oppression. He wrote more than 40 books, but his most influential by far was “Night,” a classic ranked with Anne Frank’s diary as standard reading about the Holocaust.

“Night” was his first book, and its journey to publication crossed both time and language. It began in the mid-1950s as an 800-page story in Yiddish, was trimmed to under 300 pages for an edition released in Argentina, cut again to under 200 pages for the French market and finally published in the United States, in 1960, at just over 100 pages.

“‘Night’ is the most devastating account of the Holocaust that I have ever read,” wrote Ruth Franklin, a literary critic and author of “A Thousand Darknesses,” a study of Holocaust literature that was published in 2010.

“There are no epiphanies in ‘Night. There is no extraneous detail, no analysis, no speculation. There is only a story: Eliezer’s account of what happened, spoken in his voice.”

Wiesel began working on “Night” just a decade after the end of World War II, when memories were too raw for many survivors to even try telling their stories. Frank’s diary had been an accidental success, a book discovered after her death, and its entries end before Frank and her family was captured and deported. Wiesel’s book was among the first popular accounts written by a witness to the very worst, and it documented what Frank could hardly have imagined.

“Night” was so bleak that publishers doubted it would appeal to readers. In a 2002 interview with the Chicago Tribune, Wiesel recalled that the book attracted little notice at first. “The English translation came out in 1960, and the first printing was 3,000 copies. And it took three years to sell them. Now, I get 100 letters a month from children about the book. And there are many, many million copies in print.”

In one especially haunting passage, Wiesel sums up his feelings upon arrival in Auschwitz:

“Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, which has turned my life into one long night, seven times cursed and seven times sealed. Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget the little faces of the children, whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky. … Never shall I forget these things, even if I am condemned to live as long as God Himself. Never.”

“Night” was based directly on his experiences, but structured like a novel, leading to an ongoing debate over how to categorize it. Alfred Kazin was among the critics who expressed early doubts about the book’s accuracy, doubts that Wiesel denounced as “a mortal sin in the historical sense.” Wiesel’s publisher called the book a memoir even as some reviewers called it fiction. An Amazon editorial review labeled the book “technically a novel,” albeit so close to Wiesel’s life that “it’s generally – and not inaccurately – read as an autobiography.”

In 2006, a new translation returned “Night” to the best-seller lists after it was selected for Oprah Winfrey’s book club. But the choice also revived questions about how to categorize the book. Amazon.com and Barnes & Noble.com, both of which had listed “Night” as fiction, switched it to nonfiction. Wiesel, meanwhile, acknowledged in a new introduction that he had changed the narrator’s age from “not quite 15″ to Wiesel’s real age at the time, 15.

“Unfortunately, ‘Night’ is an imperfect ambassador for the infallibility of the memoir,” Franklin wrote, “owing to the fact that it has been treated very often as a novel.”

Wiesel’s prolific stream of speeches, essays and books, including two sequels to “Night” and more than 40 books overall of fiction and nonfiction, emerged from the helplessness of a teenager deported from Hungary, which had annexed his native Romanian town of Sighet, to Auschwitz. Tattooed with the number A-7713, he was freed in 1945 – but only after his mother, father and one sister had all died in Nazi camps. Two other sisters survived.

After the liberation of Buchenwald, in April 1945, Wiesel spent a few years in a French orphanage, then landed in Paris. He studied literature and philosophy at the Sorbonne, and then became a journalist, writing for the French newspaper L’Arche and Israel’s Yediot Ahronot.

French author Francois Mauriac, winner of the 1952 Nobel in literature, encouraged Wiesel to break his vowed silence about the concentration camps and start sharing his experiences.

In 1956, Wiesel traveled on a journalistic assignment to New York to cover the United Nations. While there, he was struck by a car and confined to a wheelchair for a year. He became a lifetime New Yorker, continuing in journalism writing for the Yiddish-language newspaper, the Forward. His contact with the city’s many Holocaust survivors shored up Wiesel’s resolve to keep telling their stories.

Wiesel became a U.S. citizen in 1963. Six years later, he married Marion Rose, a fellow Holocaust survivor who translated some of his books into English. They had a son, Shlomo. Based in New York, Wiesel commuted to Boston University for almost three decades, teaching philosophy, literature and Judaic studies and giving a popular lecture series in the fall.

Wiesel also taught at Yale University and the City University of New York.

In 1978, he was chosen by President Carter to head the President’s Commission on the Holocaust, and plan an American memorial museum to Holocaust victims. Wiesel wrote in a report to the president that the museum must include denying the Nazis a posthumous victory, honoring the victims’ last wishes to tell their stories. He said that although all the victims of the Holocaust were not Jewish, all Jews were victims. Wiesel advocated that the museum emphasize the annihilation of the Jews, while still remembering the others; today the exhibits and archives reflects that.

Among his most memorable spoken words came in 1985, when he received a Congressional Gold Medal from President Ronald Reagan and asked the president not to make a planned trip to a cemetery in Germany that contained graves of Adolf Hitler’s personal guards.

“We have met four or five times, and each time I came away enriched, for I know of your commitment to humanity,” Wiesel said, as Reagan looked on. “May I, Mr. President, if it’s possible at all, implore you to do something else, to find a way, to find another way, another site. That place, Mr. President, is not your place. Your place is with the victims.”

Reagan visited the cemetery, in Bitburg, despite international protests.

Wiesel also spoke at the dedication of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington in 1993. His words are now carved in stone at its entrance: “For the dead and the living, we must bear witness.”

Wiesel defended Soviet Jews, Nicaragua’s Miskito Indians, Cambodian refugees, the Kurds, victims of African famine and victims of ethnic cleansing in Bosnia. Wiesel was a longtime supporter of Israel although he was criticized at times for his closeness to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanhayu. When Netanhayu gave a highly controversial address to Congress in 2015, denouncing President Obama’s efforts to reach a nuclear treaty with Iran, Wiesel was among the guests of honor.

“What were you doing there, Elie Wiesel?” Haaretz columnist Roger Alpher wrote at the time. “Netanyahu is my prime minister. You are not an Israeli citizen. You do not live here. The Iranian threat to destroy Israel does not apply to you. You are a Jew who lives in America. This is not your problem.”

The Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity, which he established in 1988, explored the problems of hatred and ethnic conflicts around the world. But like a number of other well-known charities in the Jewish community, the foundation fell victim to Bernard Madoff, the financier who was arrested in late 2008 and accused of running a $50 billion Ponzi scheme.

Wiesel said he ended up losing $15.2 million in foundation funds, plus his and his wife’s own personal investments. At a panel discussion in February 2009, Wiesel admitted he bought into the Madoff mystique, “a myth that he created around him that everything was so special, so unique, that it had to be secret.” He called Madoff “a crook, a thief, a scoundrel.”

Despite Wiesel’s mission to remind the world of past mistakes, the greatest disappointment of his life was that “nothing changed,” he said in an interview.

“Human nature remained what it was. Society remained what it was. Too much indifference in the world, to the Other, his pain, and anguish, and hope.”

But personally, he never gave up – as reflected in his novel “The Town Beyond the Wall.”

Wiesel’s Jewish protagonist, Michael, returns to his native town in now-communist Hungary to find out why his neighbors had given him up to the Nazis. Suspected as a Western spy, he lands in prison along with a young man whose insanity has left him catatonic.

The protagonist takes on the challenge of “awakening” the youth by any means, from talking to forcing his mouth open – a task as wrenching as Wiesel’s humanitarian missions.

“The day when the boy suddenly began sketching arabesques in the air was one of the happiest of Michael’s life. … Now he talked more, as if wishing to store ideas and values in the boy for his moments of awakening. Michael compared himself to a farmer: months separated the planting from the harvest. For the moment, he was planting.”

The web poisoned our politics: Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton and America’s digital divide

Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton (Credit: AP/John Locher/Reuters/Carlo Allegri/Photo montage by Salon)

When we talk about the media’s effect on our political discourse, usually we’re referring to the way politics are reported. There are, of course, lots of other ways in which media mediate the political process, from ads to organizing to community building to fundraising, all of which play major roles in our elections. Yet much larger than any of these may be the way the media alter our thinking about politics — purveying not just narratives that often decisively shape our opinions of a Trump or a Clinton or a Sanders, but also the larger psychological context in which we conceptualize our world and ourselves.

Over the past 30 years or so, the divisiveness, the paralysis, the seething anger, the very dissolution of politics as a mechanism for compromise and cooperation, have been the product of an energized right-wing cohort that confuses intransigence for principle. But they’re also the product of a new media ecology that has subtly transformed us in a way that reinforces the things we so lament in our politics today. It’s impossible to say whether the media introduced a new political predicate or reflected and intensified what was already brewing — probably a little of both.

Once, for all our differences, we lived in an American community that was in many ways bound by the media. Today, also in some measure because of the media, we don’t.

I am talking first and foremost about the internet and social media. Most of us know the clichés: Social media contribute to greater superficiality and less intellectual engagement, more impulsiveness, more opinion and less fact, and, perhaps most important, more polarization as the like-minded find one another and stoke one another’s prejudices and grievances, no matter what end of the political spectrum. It’s not that these things are not all true; there’s a good deal of evidence that they are. But there is something else under which they may be subsumed.

While the internet and social media have fueled polarization, the more accurate description might be “segmentation.” Oddly enough, segmentation was a long-standing media dream: that various pockets of America once forced to find commonality in the media could instead find niches. That dream was partly realized on radio, which was niche-programmed (top 40, easy listening, all-news), and then on cable TV, which began as a community “antenna” in underserved communities and quickly evolved into a series of niches — a food channel for foodies, a history channel for history buffs, sports channels for sports fans, etc.

But broadcast television was stuck in a stodgy old paradigm: the paradigm of the happy medium. It was forced to program for a vast common denominator, and that meant broadcast television news as well as entertainment shows.

There was a time, back in the late 1960s, when as many as half of the households in America that owned televisions tuned into the network evening news broadcasts every night — before aggressive talk radio and cable TV news, and long before the internet began peeling away audience. (On average, 24 million watch those broadcasts now — still sizable, but not enough to comprise a fund of national information.)

The ‘60s were a time of shared experiences and even of national conversations, since nearly everyone saw and heard the same things. It also was a time when network news divisions felt and evinced a deep responsibility to inform. After all, that was a primary reason why they had been given the airwaves — the public’s airwaves — in the first place. CBS head Williams S. Paley reassured his news staff, “I have Jack Benny to make money.”

It’s no accident that this occurred at a time when America had what historians have called the “American consensus” or the “liberal consensus,” or a sense of generally shared values. The media consensus and the political consensus, in fact, went hand in hand.

It’s no accident that this occurred at a time when America had what historians have called the ‘American consensus’ — a sense of generally shared values.

It is no accident either that the consensus began cracking at the very time right-wing talk radio and then cable news arrived — a crack to which the end of the Fairness Doctrine, requiring equal time for opposing views, certainly contributed. There were, of course, deep divisions before their arrival: geographical, racial, economic, even ideological, though I don’t remember the last ever being terribly pronounced, in part because we didn’t feel they were insurmountable. Republicans and Democrats saw things differently, sure. But they weren’t enemies in pitched battle. They were something else: opponents, as in the “loyal opposition.”

How long ago those days seem.

Talk radio and cable TV — which wasn’t using public airwaves and had no sense of public responsibility, only a sense of responsibility to shareholders — actively splintered us into audiences instead of uniting us into an audience. Prior to their ascendancy, though we had those old divisions we weren’t as fully aware of them, nor did we want to be. We preferred harmony to discord. But talk radio and cable made us aware. They worked at our wounds. They took disaffected individuals and forged them into an army. And it is that army, or rather, armies, that have declared war on American politics.

But all of this was comparatively benign until the internet, which is the grandest media “segmenter” ever devised. Talk radio and cable news had a few segments, basically right-wing and left-wing, and even the left was pretty thin, because while the right played to the idea of individualization and division, the left always favored community. The internet, however, has thousands of segments, thousands of pockets where individuals could find reinforcement of their feelings. The internet, and with it social media, knocked the American Humpty Dumpty off the wall, and it will never be put together again.

This is not the way adherents of the internet and social media put it. For them, Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, Instagram and all the other apps are ways of connecting, not separating. If so, there seems to be very little evidence of it in our political life, other than those aggrieved clusters I mentioned finding one another. An article by Columbia professor Edward Mendelsohn in the current New York Review of Books, not about the internet and politics but about the internet and connectivity, makes a similar argument. On the one hand, Mendelsohn recognizes the ways in which the digital age has made life “increasingly public, open, external, immediate and exposed.” On the other hand, this exposure comes at the expense of our deepest, most permanent sense of self. Amid the churnings of the digital world with its constant updates, selfies, and news bits focusing on externalities, we are becoming unmoored from the larger world and from our more authentic selves. We are virtual selves, created for public export.

Mendelsohn quotes Virginia Heffernan’s new book, Magic and Loss: The Internet as Art, in which she says the digital connectedness that is so prevalent on social media is “illusory.” When we use social media, it usually seems less a way of connecting to others than of celebrating ourselves, less a dialogue with others than a monologue about us: what we’re eating, who we’re seeing, where we’re shopping, ad nauseam. Social media have helped create an America in which there is not only very little national conversation, common experience, sense of community or even very much desire to cross the boundaries that divide us; they have helped create an America of 300 million separate entities, each chronicling its own individual activities. You don’t have to imagine what this does to our politics. You’re living it.

Under these circumstances, a healthy political system cannot really exist. I am not sure healthy individuals can either. Heffernan goes on to say that in this digital age of non-stop communication, “we’re all more alone than ever.” That may be the most profound and enduring effect of the media on our politics. We are now so divided we may not be able to unite; we are so divided we live within an aching metaphysical malaise of unconnectedness. We have more “friends” than ever, but feel more friendless.

Ours is an extremely discontented country today, and a seemingly discontented world, too. We usually chalk it up to economic stress, inequality, globalization, disempowerment — the usual suspects. But that media-induced malaise that afflicts us, may be the anxiety of loneliness at a time when not only we have lost one another, we’ve lost our sense of self, the one anchor that might root us in the storm. We are adrift — some from the digital world and some within that world — and so are our politics.

Brandy Clark, the Raymond Carver of the Hot Country charts: “I live in a world where we have to tell a whole story in just three minutes”

Brandy Clark (Credit: Pamela Littky)

“Art isn’t easy,” Stephen Sondheim opined, but some artists can make it look that way.

Over the past few years, Nashville-based songwriter Brandy Clark has written a slew of wildly popular songs that defy conventional wisdom of what makes a hit country tune. They have emerged out of what seems to be an effortless assembly line, but Clark’s work is far more than commercial product. Like many Nashville songwriters, Clark often works with collaborators, yet the songs she contributes to always bear the mark of a true auteur, with lyrics that are smart bombs — maybe too smart — of description and narrative detail. “Gotta take a risk, if you want a story. There’s a real fine line between content and boring,” Clark has written, and she definitely practices what she preaches. Her songs are simultaneously harrowing, cynical, uplifting and just plain funny.

Clark’s new album, “Big Day In a Small Town” is the big budget go-for-the-charts follow-up to her sublime first album, 2013’s “12 Stories.” That first record languished in the vaults for a year, becoming a samizdat hand-out from the Nashville elite who loved it, but thought it might be too smart for the room.

Since the release and critical acclaim of “12 Stories,” Clark has continually made that room a bigger, more literate place. She has written hits for country queens like Reba McEntire, Miranda Lambert and fellow traveler Kacey Musgraves, as well as provided CMA fodder for mainstreamers like Keith Urban and The Band Perry. With her new album, Clark is poised to take on the big boys and girls on her own musical terms. But despite her stellar track record, Clark has said that she writes not for the Taylor Swifts of the country world, but for the single moms scraping together the money to take their kids to a Swift concert.

As a performer, Clark may be the best interpreter of her own material, but what goes on behind the closed doors of her personal hit factory is what we talked about at 8.30 a.m. Nashville time. Like the pro she is, Brandy turned up right on time, before heading to the office for another productive day. We talked about her creative process, her musical partners, and two relevant Stephens, King and Sondheim. The interview has been condensed for length.

I’ve rarely seen anyone who’s collaborated so effortlessly with so many people and produced a body of work that has such a distinctive voice.

Well, that’s such a nice compliment, ’cause I’ve never really felt like I was a great collaborator. I’m always in awe of people that I work with that I think really are great collaborators. So that’s really a huge compliment. But Nashville is a collaborative town. I went through a lot of years where I wrote all by myself, and I think that that helped some because I know what I can do all alone. Years ago, a publisher said to me that when you are writing by yourself, you’re throwing a ball against the wall, and you know how hard it’s gonna come back at you. But when you collaborate, you’re throwing the ball with someone else. So you don’t know exactly how it’s gonna bounce back.

Who do you like to play with?

Two of my best collaborators are Shane McAnally and Jessie Jo Dillon. I think part of why that works is that not only do they like what I bring to the table, but I like what they bring to the table. And sometimes, when you’re writing songs every day, your role changes. You can’t always be the lead dog in the room. When the songs are on my record, I was probably the lead dog, or it wouldn’t sound like me. But there’s a lot of other songs that I’ve written, that have been recorded by other people, where maybe I was the cheerleader in the room that day. ’Cause sometimes that’s what you need, is getting in the room with somebody who is on fire and just coax it out of ’em. That’s just as important as being the lead dog, I think.

You mentioned bringing stuff to the table. What do you feel you bring to the process?

I think my biggest gift is storytelling. Somebody might say we’re all strong for storytelling, but I think my gift is to tell a really good story. I had a publisher early on that told me that my strength was neither melody or lyric. They felt my true gift was empathy. That I could tell a story in an empathetic way, where someone else might try to tell that story where it might come across as judgmental.

There is a real novelistic quality to your work. When I describe you to civilians, I tell them Brandy Clark is a reincarnated Raymond Carver who happens to be writing top-ten country songs. There are just so many precise, descriptive details that pop out from your songs….

That’s what I mean by storytelling being my gift. You’re not the first one to use the Raymond Carver reference!

Well, there you go. Obviously, the danger here is listening to pompous critics like me and getting all self-conscious, where you start thinking about what you’re doing. Does that ever worry you, that if you overthink the process the magic will vanish?

Oh, 100 percent. That’s something I worry about a lot. I’m not gonna say that I don’t read reviews, or what people say about me, because that would be a lie. But I try to just read it and forget it. When things started to happen for me as a songwriter, I used to try to write songs that would impress other songwriters. And that’s what a lot of people do. Because we’re in this business where we’re all working together, and we’re all trying to get cuts and trying to matter. But when things started to happen for me is when I quit trying to write songs for other songwriters, and when I started trying to write songs for people who weren’t songwriters. I would often times swing by this bank on the way to my writing appointments to make deposits or get money. And I would think about the girl who was the bank teller. And I would think; ”If she wrote a song, I wonder what it would be about?” And that’s when my songs started to make a difference.

Oddly, I think of your work as the musical doppleganger of Stephen King, another very popular writer whose work is full of blue-collar realism. I’m a huge King fan….

Me too! Sorry to interrupt, but I think of his book “On Writing” almost every day when I’m writing songs. He’s one of my favorite writers. And I’ve studied his writing. He said something in that book that I think about a lot. And I try to bring that into songwriting. Do you remember the part about where he talked about bringing two things together, so, once you’ve written about them, you can’t think about one without thinking about the other? He might have used the example of “Cujo.” I’m not sure. But anyway, you can’t think about a Saint Bernard now without thinking about rabies. And I think that is what a good lyric and melody does. Now, nobody can say, “I beg your pardon,” and not think about that song, “I Never Promised You a Rose Garden….”

In “On Writing” King also says one of the prerequisites for becoming a competent writer is to read all the time. If you read constantly, you’re learning something, even subliminally, every time you read a book. Are there any writers outside the Country songwriter pantheon that get your mojo working?

Well, Stephen King, for sure. The thing I love about him is when I read his stuff is that, with words, somebody can scare me so bad that I can’t make it from my bed to the bathroom without turning all the lights on. And I love writers that do that to me. And he’s so great at describing a scene. And then describing it again and again and again, and you never get bored with it. He’s one of the “go to’s” when I need some inspiration, when I feel like I don’t have an idea, because his language sparks an idea for me.

What about songwriters?

Dolly Parton. Every fall, I listen to Dolly ’cause it just puts me in a “fall” mood. I want to hear her then, and her songwriting definitely inspires me. Strangely, most of the things that really do inspire me aren’t when I’m looking for ideas. It’s usually not songs. Dolly is the only writer I think of that, when I listen to her, other song ideas will come to me. It’s usually a novelist. Rick Bragg, who wrote “Ava’s Man” and “The Prince of Frog Town.” He can really inspire me. Biographies will also do it for me. I’m always reading somebody’s biography and some kind of fiction.

Another writer that comes to mind when I think of your work is believe it or not, Stephen Sondheim. He’s another incredibly precise, detail-oriented, strategic songwriter.

Yeah, he’s great.

Besides sharing a creative gift, you, Shane and Sondheim are also gay. Does that add to a more “outside, looking in” perspective?

You mean like us being gay, looking at and talking about it like heterosexual relationships?

Yes. Or bringing a slightly refined kind of focus to that creative table…

Maybe so. But for me, I grew up where pretty much everything about me was “All American.” I didn’t grow up with money, you know, charmed, but I had a really nice family, and was loved, and was good at things. Good at sports, and good at being smart. The only thing that made me feel like an outsider was when I got a little older. And I discovered that I was gay. So, maybe there is some of that. I’ve never thought about it. I’ve thought about when I write about relationships, I don’t think of homosexual relationships as any different than heterosexual relationships in the complexities of them. When I write, some people have asked me, Wow, how do you write about “What’ll Keep Me Out of Heaven” — which was a song on my first record — how do you write about that, being gay? How do you write about this man and this woman that are about to have an affair? My answer is, well, it’s the same thing. The feelings are the same. At least, I think they are. I only know what I feel, but I think human feelings are all pretty much the same.

Let’s take a song like “Three Kids No Husband,” which is my current favorite song of the year. How did that get written? What came from where?

It’s interesting that you would bring that song up, because that one truly shows off the beauty of collaboration. I wrote it with Lori McKenna. She and I were set up to write in a Nashville songwriting appointment. Publishers get together and they set writers up, and you meet at a in an office at a certain time. And so I walked in that day and Lori suggested we sit down and maybe have some coffee and catch up a little bit. And then, we started talking about ideas and Lori said, “I have an idea and it came from I was watching you on YouTube last night. You were talking about another song of yours that you wrote that’s about a woman who has five kids and no husband.” That was a song from my first record, “Pray to Jesus” which was about a woman I’ve known my whole life. And she does have five kids and no husband. And Lori said that in itself would be a great song. But then she said, “I think that five kids is a little extreme,” which is funny, because Lori has five kids. But then she said, “maybe, three kids and no husband.” And I instantly loved the idea. And we just started writing it. We never really said, “Hey, I know this person who’s in this situation.” We both just knew people who were. I think we all know somebody like that. I think that’s part of why that song resonates.

I’m looking at a title like “Drunk in Heels” or some of your other one-liners that seem to arrive perfectly at their respective destinations. Are there lines that can provide the inspiration for a song?

Every day is different. Those two songs in particular, I can tell you exactly where the ideas came from. You know, “Drunk in Heels,” I’ve always loved that quote about that Ginger Rogers did everything that Fred Astaire did except she did it backwards, in heels. I was just looking at that, and I thought “drunken heel.” For women, if we get drunk, we do it in heels. I didn’t really know what to do with that, but I shared it with Jennifer Nettles, and said you know, I love that title, “Drunk on Heels.” She marinated on it, and then, came to me on fire about an about an idea on how to start it.

What about “The Girl Next Door?”

That was literally something that Jessie Jo said. She called me, and was talking about this guy that she was dating at the time. And, Jessie’s a bit of a wild child, in all the best ways. And when they started dating, he really loved that about her, until he didn’t, and wanted her to be a little more demure. As she was telling me all this, I said, “Jessie, how does that make you feel?” And she said, “I just wanna say, Brother, if you want the girl next door, then go next door.” And that just sounded like a song to me. And I said, “Jessie, that is a song, and we have to write it.”

And the biggest hurdle was figuring out how I was gonna get Jessie, me and Shane together. How do I get the two of us out of this other project, so we can write this song with Jessie, because, if we don’t, she’s gonna write it with someone else. That’s how urgent that idea was to me. And how good I thought it was. There’s no way Jessie’s gonna sit on this for 48 hours. So, both those songs came about very differently, but ended up in the same sort of place.

Arlo Guthrie had a great quote, which I’m sure you’ve heard about. “Songwriting is like fishing. You cast the line and see what you can come up with.” And, Arlo added, “I don’t think anyone fishing downstream from Bob Dylan ever caught much of anything.”

[Laughs.]

Does that describe this process? It’s tough to discuss the ephemeral, but you’ve obviously given so much thought to craft.

Somebody said to me a long time ago about songwriting being God-given, but you had to get up and meet God halfway. I think there’s some truth to that. Harlan Howard is a songwriter that I have looked up to my whole life. His songs were part of what made me want to be be a writer. Harlan said, “I didn’t write the best songs of anybody I knew. I just wrote more of ’em.” And I think that there’s some truth in that. I think that you have to write a lot of bad songs to get to the good ones. The people who are commercially the most successful are usually writing the most songs. At some point, it’s a numbers game. I think for me, not every day is gonna be a day where you’re gonna have a great idea.

It’s practice. I think that every day when I’m writing. And when the great idea comes down the pike, that’s the game. But if you haven’t been going to practice, you’re not gonna play well in the game.

I never stop writing. Lately, it’s been tougher for me because I’ve been on the road so much. But in all that, I’m always writing. Maybe not sitting down and able to hammer it out, but I’m always looking for ideas. I think that for anybody who’s a true songwriter, there’s no turning it off. Every conversation. You’re not purposely looking for songs, but it’s just in you to hear songs in what people say. And I think that is a huge part of the craft. I don’t always study other songwriters but what they do moves me. I really listened to their songs and looked at their songs. I used to do it a lot more than I do now. Maybe I should do it again. What makes them hits? I think that there’s something in all of that.

Outside the Country tradition, are there any songs that you say, “Boy, I wish I had written that?”

Definitely. Carole King. “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow.” That’s one of my favorite songs of all time. This is a strange thing. I love songs that are all about sex — without ever saying that. I think it’s brilliant. You know it never says making love. And I think it’s so vulnerable. I try to write songs that are vulnerable. Will you still love me tomorrow? If we do this tonight, will you still love me tomorrow? I don’t know anything much more vulnerable. Outside of country, Elton John is probably my favorite artist. So many of his songs moved me for a different reason than “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow?” That’s really about the lyrics. Elton John’s songs move me melodically. I went and saw him and Billy Joel a couple years ago. And there’s “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” and that part where it’s like … [She tries to sing it, but —] It’s too early this morning, but I remember crying on that part. And thinking, that’s not even a lyric. But the melody says so much it moves me to tears.

I like a lot of those Linda Ronstadt songs. I don’t even know who wrote all of ’em but those hit me. You know, “Long Long Time” and “Love Is a Rose,” those sorts of songs. To me, they’re rock songs, but they’re really country songs.

Neil Young wrote “Love Is a Rose.”

Did he really?

Yeah. One of the ones he gave away.

I didn’t know that. The Eagles. I think Don Henley’s one of the best — not only with the Eagles but in his solo career. I think Henley’s one of the best songwriters of our time, of any time. Those songs are a great balance to me as American melodies.

What’s interesting here is the artists you’re connecting also happen to be hugely popular artists. But then, I come back to your particular gift of detailing, that kind of literary quality. This is why I can’t understand why “12 Stories” couldn’t get released for so long. You must have spent a lot of time staring at your beer saying, I know this is brilliant, what gives, why don’t people recognize it? Why do you think it took so long for mainstream Nashville to “get it?”

I think all the artists that I’ve talked to you about were huge, but they’re also from another time. And, I think that songs like “Hotel California” are very literary. I think we live in a fast-food society now. And if those sorts of songs were being written today they’d have a harder time finding a home. If that makes any sense.

It does.

And I’m not comparing myself to those artists. I wanna make real sure that I don’t come across as doing that. They just inspire me, as does Dolly Parton. I think there are things about Dolly’s music that would have a hard time finding a home today. Merle Haggard. I think Dolly and Merle are two of the greatest singer-songwriters of all time. I put them up there with James Taylor and Carole King — but they just happen to be Country.

As far as me having a hard time finding a home in Nashville, I think sometimes songs that are a more detailed and literary have a harder time. It was an L.A. guy who signed me. It wasn’t that people in Nashville didn’t like what I did. I definitely felt like they did. I just think they didn’t know what to do with it. I got told that a lot. Like, “Oh I love this, or “Man this is my daughter’s favorite record.” I don’t know what to do with it. That’s all I know how to say.

From the sublime to the maybe ridiculous, tell me about your “Hee Haw” musical. That sounds completely intriguing.

Now, it’s called “Moonshine: That Hee Haw Musical.” And it’s still in development. That was the project we were working on when I told Shane we needed to take a day off and write “Girl Next Door.” He and I were approached based on “Pray to Jesus,” to work on that musical along with a guy named Robert Horn, who wrote the book. It opened in Dallas last summer. Shane and I are kinda taking a break from it right now because the changes everybody feels are necessary are story changes. And so we can’t make any changes to songs until we know what the story changes are gonna be! But it’s taught me a lot. It’s taught me that I can write for a project. I never thought I could do that. That always scared me a little bit to write like, “Oh, now I’m gonna write this record. And this is what it’s gonna be about.” I’ve always shied away from doing that. But after working on “Moonshine” I learned that I could do that, because the producers would come in and say “Hey, we need a different first act closing number.” Shane and I would sit down and do that. He and I live in a world where we have to tell a whole story in just three minutes. But in that world you need to tell little bits of the story and be real careful to not give away too much too soon. But I learned a lot. I was pushed to do things that I never thought I could do.

Gay Talese’s “ethical mess”: Fact-checking lapse raises old questions about New Journalism

Gay Talese (Credit: Reuters/Carlo Allegri)