Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 728

July 5, 2016

No indictment, no scandal: After a year of email chatter, we can finally close the book on another Hillary witchhunt

Hillary Clinton, James Comey (Credit: Reuters/Mike Blake/AP/Charles Rex Arbogast/Photo montage by Salon)

James Comey’s news conference Tuesday, in which the Republican-appointed FBI director announced that his agency would not recommend indictment of Hillary Clinton over using private email servers to discuss State Department business, revealed that the entire email “scandal” was about what most reasonable people expected it would turn out to be: Clinton chose convenience and speed in doing her job as secretary of state over security. Stupid, and as Comey said, careless, but the FBI can’t call it criminal and recommend an indictment over it.

No doubt the Republicans are planning to make a fuss out of this, but without that precious indictment, it will be hard to keep this scandal from joining the lengthy list of Clinton non-scandals, from Benghazi to Whitewater to Monica Lewinsky. The pattern still holds: The right makes a lot of lurid accusations, the mainstream media gets caught up in it, investigations are conducted, and inevitably it turns out the Clintons didn’t do anything illegal and their sins are venial ones committed just as surely by the accusers as the accused.

(How many Republicans pointing a finger at Clinton have blown off security recommendations to update their passwords, because they weren’t willing to put up with inconvenience in the name of security?)

There is a deep irony here, because the last effort at creating a Clinton scandal — Benghazi — swirled around accusations that Clinton wasn’t swift and responsive enough in doing her job. (It was a false accusation, but that was the premise of the accusations.) Now the accusation is that Clinton was too swift and responsive, which made her unwilling to engage with security measures that slow you down. It’s a neat reminder that the two decades-long effort to demonize the Clintons as corrupt has never once, for a single second, been about good faith concerns over corruption, but just about blowing so much smoke that they can convince the gullible among us that there’s fire.

In a normal election cycle, this gambit might just have worked. The mainstream media, which naturally orients towards breathlessness and scandal, is portraying Clinton’s behavior as out of the norm, when in fact it’s sadly all too common for people, whether high-powered executives or average Joes, to get sloppy with security because dealing with all the rigamarole is too much trouble to deal with. Without that context, Comey’s language about Clinton being “extremely careless” could impact voters who don’t quite understand the tech issues at stake here to think that Clinton was motivated by more than impatience with inconvenience.

Sadly for Republicans, however, Clinton’s opponent is Donald Trump, a man who radiates corruption out of every single one of his spray-tanned pores. It’s genuinely difficult to work up a head of steam over Clinton being too lazy to switch to a work email from her regular email to discuss business when she’s running against a guy who literally bilked little old ladies for thousands of dollars in exchange for “get rich quick” classes that did not, unsurprisingly, help anyone get rich at any speed.

While making predictions this election cycle is a somewhat fraught enterprise, on this, it seems that the likeliest outcome will be that this year’s worth of email chatter will not really matter in the end.

People who already hate Clinton will add “emails” to their long list of half-baked conspiracy theories, including accusations that she is secretly a lesbian and a cat murderer.

People who like Clinton will chalk this up to the Clintons’ unfortunate tendency to behave as if they were normal people, instead of accepting that they live in a fishbowl where they are held to much higher standards than everyone else, such as the folks that traded emails with Clinton on similarly unsecured servers.

Everyone else will simply be unconvinced that careless and sloppy email behavior presents nearly the same security risk as letting Trump near the nuclear codes.

And no one will learn anything from this about actually listening to those computer security guys at your job who are always telling you boring stuff like “pick a better password” and “be careful where you send emails from.”

And hopefully, when Clinton gets into the White House, she won’t decline her own security experts when they tell her she has to hand that Blackberry over and they really mean it this time. Yes, even though having to put up with protocol will likely slow her down.

July 4, 2016

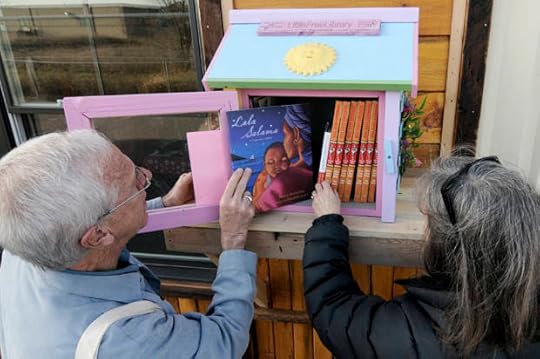

My Little Free Library war: How our suburban front-yard lending box made me hate books and fear my neighbors

A Little Free Library lending box in Hudson, Wis. (Credit: AP/Jim Mone)

Saturday mornings unsettle me. Especially when the weather’s good. There’s a lively farmers’ market just down the street from us, with a bluegrass band, homemade donuts and vegan tamales. It’s great, if you’re into that sort of thing.

But it means floods of the worst kind of foot traffic. Graying gardeners and aging hippies; Bernie-or-Bust types; millennial parents, tatted and pierced, shepherding toddlers with names like Arya — damn near every one of whom stops to check out my Little Free Library.

And after paying $18 for an heirloom tomato and a pair of zucchini, you can’t blame a person for grabbing a free book. Indeed, this kind of neighborly interaction was exactly what my wife Heidi was hoping for when she got me the library for Hanukkah. Heidi’s the sunny and optimistic type, yin to my cranky yang, which made her an easy mark for the Little Free Library Foundation and its stated mission of promoting “the love of reading and to build a sense of community.”

She and the kids did it up right, painting ours lilac to match the color of our Victorian house. The library makes a striking contrast with the verdant green that blankets our block in the spring. But idyllic as that sounds, when the marketeers, wagons in tow, stop to fiddle with the latch and peer inside, all I feel is dread.

***

Little Free Library originated in Hudson, Wisconsin, in 2009, when Todd Bol built a wooden box with a glass door, modeled on a one-room schoolhouse, in honor of his mother’s career as an educator. He nailed the box to a post in his front yard and stuffed it with books. The idea spread and in 2012 Little Free Library incorporated as a non-profit. By January of 2016, there were at least 36,000 Little Free Libraries across the globe.

They seem particularly popular in our town, Oak Park, a progressive suburb just west of Chicago. We’re a bookish community with a thriving independent bookstore, a showpiece library and a proud literary heritage that includes Edgar Rice Burroughs, Jane Hamilton and Ernest Hemingway.

It’s easy to see why Heidi imagined a Little Free Library would be a great gift for me. I’ve always enjoyed checking out other people’s books. Partly this is a party survival strategy. My misanthropy is such that at social gatherings I like to take a respite from small talk to peruse people’s bookshelves and CD cases, which gives me an excuse to turn my back on literally everybody. Sadly Spotify and Kindle have eliminated most of these analog escape hatches. But I’m still genuinely interested in what other people read. So the idea of curating my own selection was immensely appealing. I’m a history teacher and I dabble as a children’s literature critic, so, if I’m being honest, I flatter myself on my taste in books.

Heidi is even more of a book snob than I am. She’s from the librophile equivalent of old money — her late, beloved father Bill was an antiquarian and her childhood home brims with 18th century atlases and first editions of U.S. Grant’s memoirs. So we both turned up our noses at the castoff books that came bundled and shrink-wrapped with our purchase (an oddly eclectic group which included “Screaming Monkeys: Critiques of Asian American Images” and a set of Disney princess-themed board books). As Heidi put it, in what proved to be a wildly optimistic sentiment, “We’re better than that.”

Since our book collection had long outgrown our shelf space, it was easy to find the first offerings for our library. Our bookshelves, end tables and nightstands were stacked with medium-brow novels, chapter books that our kids had outgrown and, my guilty pleasure, Nordic-noir fiction.

I quickly took to the daily ritual of inventorying our stock to see what had gone into circulation. It was fun to see what sorts of title moved and which got passed over. But as the stacks on the nightstand shrank, a realization dawned on me. We were gonna run out of books. The math was daunting. Even before the spring strolling season had begun, we were losing two to three books a day. With warmer weather and the farmers’ market ahead of us, we could expect to bleed a thousand books a year.

***

Little Free Library has a seductive marketing slogan that’s carved into the top of every unit: “Take a Book; Return a Book.” Such a simple equation. And such wishful thinking. Take? Oh, absolutely. People are, in fact, really good at that part. For example there was the young mom who lifted her toddler up to the box, watching uncritically as he scooped up “Imaginary Homelands,” Salman Rushdie’s collection of criticism and essays. Which I’m sure he enjoyed.

When it comes to returning, people mean well. For example, I don’t doubt the sincerity of that young mom when she told her greedy little urchin, “We have to remember to come back soon and give them some books.” The problem is that, to borrow my favorite report card phrase, remembering, for most people, “remains an area of growth.” It’s not that I blame my (mooching) neighbors. Indeed, I, myself, seldom return books to the public library on time. And they fine you if you don’t. But since I don’t punish people (unless you count silent, withering judgment), I’ve got no leverage. The truth is laziness is just part of human nature. It’s what separates us from the beavers.

But the lesson was clear. I wasn’t running a library. Libraries are built around the idea of circulation. And circulation implies a circle. What I had, aside from the contributions of a few kind neighbors on my block, was a one-way street of literary handouts. So it wasn’t long before I concluded that if I was going to stay in business, I had to reduce the outgoing volume.

Luckily I had an ace in the hole. At last year’s public library book sale, our family had, as a joke, played a game of “Find the Boringest Book.” And, not to brag, but we’d kicked some ass.

So imagine my surprise when, within 24 hours, a paper-bound copy of “Study Guide and Reference Material for Commercial Radio Operator’s’ Examination” (1955! edition) had vanished. 1965’s evergreen “Technical Analysis of Stock Trends” was next. “Aircraft Power Plants from Northrop Aeronautical” lasted just a few more days. And the winner of our boringest book contest? “Standard Mathematical Tables,” 22nd Edition, a nearly wordless and entirely incomprehensible collection of graphs, made it a week.

Okay, neighbors, I thought. You gonna troll me? Come correct.

Out with the Chabons, the Franzens and the Morrisons. Goodbye to the Booker and Pulitzer winners. Ruthless pragmatism became my m.o. Grimly, I took to scouring yard sales and recycling bins for dull books, just another soulless middle manager, firming up his supply chain and moving product.

Now fully in transactional mode, I greeted the news of my teaching partner and good friend James’ decision to move his family to Seattle with this question: “You’re not taking all those books, are you?”

James’ classroom was a treasure trove. He’s a germanophile with a peculiar interest in Prussian maritime history. And he had a class-set of books called “Facts About Germany” (even duller than it sounds). I filled the library with them, 18 in all.

And they went.

As did the German Historical Bulletin’s Supplement 7: “East German Material Culture and the Power of Memory.” The eagerness with which my neighbors absconded with dated monographs about Teutonic history got me wondering what the German word is for resentment of freeloading neighbors.

And it drove home another lesson: Not only was I not a librarian, I wasn’t even really dealing in reading material. That the objects in our Little Free Library happened to be books was beside the point. The salient fact was that the items were free. We may as well, I suspected, have been offering plastic spoons, Allen wrenches and facial tissue. I tested this hypothesis by mixing in non-book items including an instructional DVD on how to use an exercise ball, and a few packets of echinacea seeds.

All of it went.

So why do people take things they don’t need, or even really want? Well, it turns out people really, really like free shit. Daniel Ariely, a psychology professor and behavioral economist, has studied how making things free distorts the decision making process for consumers, pushing us to jettison the traditional cost-benefit analysis we bring to purchases. Think of otherwise sane people showing up late for work because they stood for 45 minutes in line to get a “free” donut.

As Ariely puts it, “decisions about free products differ, in that people… perceive the benefits associated with free products as higher.” I got that quote online from a paper Ariely published with Kristina Shampan’er entitled “Zero as a Special Price: The True Value of Free Products.” I’m sure Ariely wrote something similar in his best-selling book, “Predictably Irrational.” But I can’t say for sure because somebody scooped up my copy about an hour after I put it in my Little Free Library.

Toxic masculinity doesn’t just target women: The viciousness and vacuity of modern American manhood is also harmful to the self

(Credit: AP/Andrew Weber)

The late Jim Harrison – one of America’s greatest novelists and poets – acquired an unwanted reputation as a “macho writer.” He was hateful of both the word and the boneheaded behavior it describes, once explaining his objection to a literary critic, “I have always thought of the word ‘macho’ in terms of what it means in Mexico – a particularly ugly peacockery, a conspicuous cruelty to women and animals and children, a gratuitous viciousness.”

Critics with narrow cultural comprehension applied the label to Harrison, because he often wrote about roughneck, working class characters in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan or on the ranches of Montana. Harrison explained that men who live in a perpetual struggle of physical exhaustion and emotional stoicism, developing a spirit of steely resolve in the process, do so not because they are “macho,” but because they suffer from having limited choices and options for self-survival. A man does not help build a dam, like the protagonist of Harrison’s novel “Sundog,” because he wants to construct an image of intimidation, but because he needs to feed himself and his children. The toughest man I’ve ever personally known, and also one of the most sensitive, was my grandfather. He experienced combat in World War II, because he was drafted, and he worked in the Material Service quarry, because hard, manual, and unionized labor was the best guarantee of middle-class stability in small-town Illinois for inhabitants without college degrees. He hoped his daughter and his grandson would have easier, less painful and less onerous lives, and when he died, he was relieved that we did.

Manhood in America has reached a bizarre and bipolar state of incoherence. Despite staggering levels of technological, intellectual, and cultural advancement, there remains an insistence on celebrating the most stupid and destructive forms of “ugly peacockery,” masquerading as strength and courage. Throughout American culture there exists a dangerous nostalgia for a lost, and largely imagined, age of masculine power, where real men got things done without the meddlesome supervision or maternal aid of institutions, regulatory bodies, or women.

The glorification, or at least, tacit acceptance of anti-intellectual and pre-industrial conceptions of masculine virility and potency contribute to the retention of high domestic violence rates and the scandal of routine rape in the military. Feminists have developed a term to attack insensitive and selfish expressions of chauvinism, calling it “toxic masculinity.” The phrase is cumbersome, and it carries the stench of self-pity, but it earns absolution for its rhetorical sins with its substantive veracity. Macho peacocks do develop an infectious form of masculinity that poisons everything it touches, often inflicting the most damage on the host. It is not only an assault, but a slow and steady suicide.

A recent New York Times profile of Kosta Karageorge, an Ohio State wrestler and football player who ended his own life with a bullet to the head while sitting alongside a dumpster, maps the dark world the macho peacock enters, and all of the pitfalls that wait within it.

Karageorge was born into prison cell of macho design, with no chance for parole. His father and uncle embraced an odd ideology that they were born to martyr themselves for the edification of barbaric rituals. His uncle cracked three helmets while playing football in high school, suffering concussions and other injuries, while his father once absorbed such a severe blow to the head, he woke up in a hospital disoriented, barely responsive to stimuli, and unaware of the reason for his hospitalization. He was back on the football field, using his skull as a battering ram, a mere two weeks after his release.

These brothers, with seemingly little input and no intervention from Karageorge’s mother, put Karageorge on a Neanderthal training regimen, leaving little room for childhood enjoyment or healthy intellectual development. Under the watchful and intense eyes of his father and uncle, Karageorge would begin every morning with pushups at the age of 12, and at the age of 14, began a strenuous weight training discipline. Family gatherings would often end with the insanity of Karageorge and his fully grown uncle getting into violent wrestling bouts.

Before eighth-grade graduation, Karageorge began losing hair. His father took him to the barber for a buzz cut so as to disguise the embarrassment of his bald spots. A doctor diagnosed his condition as stress-related alopecia, presumably from the pressure his father and uncle imposed on him to become a world class athlete. It is hard to imagine a more colorful, bold, and big red flag flapping in the wind, but Karageorge’s parents and uncle continued driving straight in the direction of the cliff’s edge.

In high school, Karageorge gorged himself on so much high-protein food that he had no choice but to carry a small trash can with him at all times in preparation for a gag reflex incitement of vomiting. As if puking in the high school cafeteria was not sufficient entertainment, he would jog to the point of delirium, often stopping only to vomit. In addition to regurgitation, Karageorge developed the hobbies of fist fights and firearm collection. It was at the age of 11 that Karageorge’s uncle and father first took him to the shooting range, and began their initiation of the boy into America’s weird gun culture.

As even a concussed child could predict, academics did not receive much emphasis in Karageorge’s household, meaning that in addition to providing life’s only purpose and source of empowerment, violent sports also were his only point of entry into college. A friend remembers finding it alarming that Karageorge once spoke about his disappoint over losing the statewide tournament in wrestling two consecutive years, while cleaning his rifles and handguns.

In the aversion of an even earlier disaster, Karageorge earned acceptance into Ohio State University, where he played football and wrestled. Throughout his higher educational experience, he found it increasingly difficult to function as a cognitive adult. For years he had hid the symptoms of multiple concussions, because he believed that to complain would make him look “unmanly.” When his parents knew of his concussions, they took no action. Karageorge’s father described one of his son’s worst concussions to the New York Times as “getting his bell rung,” using professional football commentators’ preferred euphemism for traumatic brain injury.

At the time, Karageorge could not even bear to look at his cell phone, because the dull light cast from the screen would give him headaches. Meanwhile, his behavior became so erratic, he eventually resembled a maniac. He would force his roommates to lift weights before they left the house, only allowing their exit when they earned what he called “man points.” He was also obsessed with guns, buying and selling them at gun shows and on Craigslist, and fondling them like sexual objects. Women did not have much of a presence in Karageorge’s life, but the lone girlfriend he did manage to have left him when his temper turned to hysterical fits of rage, both frightening and repelling her.

It never fails to fascinate that macho peacocks usually refuse to show interest in women, beyond viewing them as territory to conquer or irritants to eliminate. Typically, these men are the most eager to insult gay men, and the least reticent to express attitudes of extreme homophobia. At the same time, without a sense of irony or inconsistency, they fetishize the masculine, while completely rejecting the feminine; creating a social and recreational world of homoeroticism. Karageorge had a poster of a speedo-wearing Arnold Schwarzenegger in his bedroom, and would often surprise his roommates by wrestling them to the ground, occasionally destroying furniture in the process. One can only speculate about the strange sexual contradictions that occupy the minds of men who hate women, adore cartoon representations of the masculine, but consider homosexuality an anathema.

Karageorge sustained a severe concussion weeks before his suicide. Already unable to concentrate and unable to control his emotions, he must have felt as if his brain was in constant betrayal of him. An examination of his brain, performed after his death, revealed that he had Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, a degenerative brain disease resulting from multiple concussions, and common in football players, wrestlers, boxers, and military veterans. Even at his worst point, his parents encouraged him to play football.

In 2014, at the age of 22, Karageorge ended his own life.

Karageorge’s suicide is a modern American tragedy. Although when he reached the age of reason, he became responsible for his own choices and behavior, he was clearly collateral damage of a war over manhood, and a battle in which meaningless macho symbols — exhibitions of physical strength, brawls without cause — become more important than quality of life.

When considering the suicide of her son and her parenting, The New York Times reports that Karageorge’s mother asked, through tears in her eyes and a crack in her voice, “What did we miss?”

While it is impossible to dismiss the grief of a mourning parent, that question demonstrates a horrific state of self-imposed ignorance, and provokes a sad inquiry into how many other parents idly watch their children suffer trauma for phony athletic glory, just as oblivious to the short term losses and long term consequences.

The father turned his finger and thumb into a gun and held it up to his temple, recreating the suicide to the Times reporter. When commenting on Karageorge’s concealment of his symptoms, he explains, “We raised our son to be a strong man, and maybe that was his downfall. He wasn’t complaining and crying. My wife coddled him, but I was more: ‘One of these days you’re going to be depended upon to step forward.’” He then added, “There’s a ton of guilt there.”

Karageorge had a tattoo of Atlas covering his entire back. He said it symbolized how he “had the weight of the world on his shoulders.” He was not supporting a family. He was not running a business. He was not leading an Army into war. He was a college wrestler.

The burden he felt crushing him into the ground was a stone he placed on his own back, without coercion or threat of penalty, on a daily basis. A single mom, working a full-time job and trying to raise a family, overcomes more obstacles and shoulders a heavier load in a matter of hours than Karageorge had to confront in his entire life. The psychological oppression he fought had no genuine imposition from the outside world. It was a result of his upbringing, and his absolute faith in the value system of the macho lifestyle. With crucial collaboration from his father, uncle, and elements of wider American culture, the monster that murdered him was of his own creation.

The essential truth that purveyors of “toxic masculinity” violate, and what too many feminist critics of it miss, is that among its victims are men themselves. Life becomes much more pleasurable, comfortable, and joyful after emancipation from the macho prison. Releasing the backbreaking weight of macho nonsense makes life much easier, and the arbitrary and often cruel nature of the world is opposition enough without creating hardships and enemies where none need exist.

The heart breaks with the realization that Kosta Karageorge’s ugly demise was preventable beginning in his first moments of childhood, but that no one intervened, and that he himself was even unwilling to advocate for his own health. Millions of other boys, too young to make their own decisions and too immature to discover how to best harvest their own potential, do not have to experience the same sad ending.

“I’m in awe every day”: Virginia Heffernan on technology, virtual reality, and what the Internet means

Virginia Heffernan (Credit: YouTube/Talks at Google)

There’s a highbrow East Coast/West Coast throwdown underway. On one side, you have the techno-utopian designers of Silicon Valley, claiming to save the world one pizza delivery app at a time. And, on the other, you’ve got the New York literati, complaining about corporate surveillance and the death of the book.

It’s the literary critics vs. the programmers. Yale vs. Stanford. Gawker vs. Peter Thiel. Evgeny Morozov vs. the Internet.

Within this little feud, culture critic Virginia Heffernan has been a longtime outlier, peacemaker, and iconoclast. Heffernan has literary East Coast chops—she earned a PhD in English Literature from Harvard, and then worked as a TV and tech critic at the New York Times for close to a decade.

But Heffernan has long celebrated the aesthetic potential of the web’s whackier and more whimsical corners. She may well be the least cranky tech critic east of the Rockies. In her new book, “Magic and Loss,” she argues that “the Internet is a massive and collaborative work of realist art”—a kind of giant role-playing game that demands “a new aesthetics and associated morality,” and, perhaps above all, a sense of wonder.

Over the phone, Heffernan spoke with Salon about personal avatars, virtual reality, and why she wrote an entire book about the Internet that barely mentions surveillance.

The Internet is art? I thought it was a shopping mall.

I love to find out what metaphoric system people already bring to the Internet. You say it’s a shopping mall. Someone who believes that YouTube comments or Facebook are the touchstone for what the internet is might say that it’s a mob or a trash heap, or that it’s this giant college where we all know each other.

I first went on the Internet as a game player. It was the’ 70s, and I was playing a D&D-inspired game on this ARPANET-era computer. I always feel I’m playing a roleplaying game when I go online.

So what’s a good way to talk about experiences of the Internet?

In the book I talk about the sort of spectacle many of us first got when we touched Google, of the “too-muchness” of the Internet. Early in my life I had this grandiose fantasy that maybe one day I would be able to read everything. As soon as I saw Google, I lost the will to read because I was so overmanned.

As soon as I adjusted to the sublimity of the Internet, I could understand that the moral act was no longer reading, but in some ways refraining from reading. We are in a period where we’re all so intoxicated by reading that we risk highway fatalities in order to keep reading and writing on our phone.

Alternately, you could say that Silicon Valley has just gotten really good at engineering compulsive products .

It’s a little bit like social space, or walking through a souk. Anytime you’ve had to learn how to survive in the city, there’s an opportunity to see this as predatory.

But instead of us saying “well the system’s all jinxed. There’s no way to walk around in the market capitalist democratic country public square, without getting mugged,” we don’t take into account that that’s part of the pact. People are welcome not to enter the Internet at all, but to the extent that they enter it, they are at every turn creating an Internet citizen or an avatar who, yes, needs to look out for itself.

I definitely see people making really interesting decisions about how they’re going to resist digitization. That is another way to participate in the Internet: to resist. It’s not a place for terminally vulnerable, innocent people. But what I think I’ve been amazed at is how many billions of people have, to some extent, risen to the occasion and created durable avatars who are doing interesting things.

It’s always hard to draw the line between online and offline life, though. What’s real?

They are real characters, let’s put it that way. The seductiveness of the realist masterpiece that I call the Internet makes some of us lose our orientation around the fact that this is fantasy.

Fantasy or not, when I log in to the account for my online bank, the number I see there has a direct impact on my life. How do you deal with blurred lines between online and offline persona?

We know the rubber hits the road when we’re talking about dollars and cents and bank accounts. You can’t be like, “Well ‘Heffernan8’ on Citibank is like a fanciful invention of me!”

Sometimes I like to think that my avatar takes sniper fire for me while the real me gets to be safe. I feel like my offline life has gained. It’s much richer and more interesting because of all the symbolic business happens without the flesh and blood me being present.

So why are critics so grumpy about the web?

I feel like it’s anxiety about abstraction, because if kids are just sitting staring at something, it just has to be bad for them.

The amount of dollars spent trying to figure out exactly what the toxin is in television…and now screens? Is it something in the jumpcut? Is there something in the advertising? We can’t quite find out why this is poisoning us, but we continue to believe it’s poisoning us. That is definitely an article of faith at many of our newspapers and magazines.

Your book barely mentions pornography, surveillance, or corporate control. Why did you omit topics that seem so central to online experience?

I wanted to talk about the art of the Medicis, not about the tyranny. I was frustrated that most of the writing about the Internet was seemingly still fearful. I didn’t want to touch neuroscience or that kind of heavy political view, because no one had talked about the art.

Are the artistic project and the profit motive incompatible in some ways?

Thing just aren’t produced if money isn’t being made.

Why did poetry suddenly become short when the New Yorker was the gatekeeper for all poetry? If you’re weighing it against a cartoon and columns of text, then suddenly you can’t write like Walt Whitman with long lines. Most great American art forms, including novels, do end up finding a way to make some money. I know some artists don’t like to have to push back on the market, but to a great extent I appreciate the art that finds dynamic tension in that relationship, and not just crushing tyranny.

That New Yorker poetry example is funny. Part of demonizing current technologies and forms is idealizing past ones.

If you think of yourself as anti-technology, you’re probably under the spell of another technology. Nostalgia in the heyday of mechanical reproduction [by printing press] used to fetishize the human hand and the quill, or the single sheet of paper.

Some new tools are actually starting to enter our bodies and minds in a more tangible way, though. Is that a categorical difference from older generations of technology?

We’re fully material. We have time and place. When I want to be out of that time and place, when I want to feel like my life is in the cloud, when I want to shake up my sense of myself as unique and alone, then I love the world of the Internet. When I want that back—when I don’t want to be like Don Quixote, with my head always in the clouds—then I go in the other direction.

When I was playing Dungeons & Dragons as a kid, there was such a terror that we were going to disappear into this world. Like an LSD thing. “From then on, he never was in touch with reality again.” That’s not my experience with even totally impassioned Internet players.

But there’s this fear of tipping over, isn’t there? We’re a society that values shared, public experience. Something like Oculus Rift cuts against that.

I really thought virtual reality was like a hallucinogen that I am interested in taking in very small doses. It’s highly pleasurable, and yet so concentrated and strange that I felt it really would be like doing LSD all the time.

You chose to publish Internet criticism as a book. Why did the format seem appropriate to the task?

When the Wall Street Journal was regularly reporting on Big Tobacco—it was before I came to the Times—I had been thinking, “Why write all this ephemera?” Because I still thought of journalism, as they used to say, as wrapping for fish the next day. You were writing on water. It’s going to be gone.

Spoken like a true academic.

But then I saw what the Journal did with their reporting, and I was like, “Oh, I see. [They are] making an argument over time.” Whether someone connects the dots or not, some themes are going to color everything you write about. There’s a reason that ideologues are good at columns. Because they can always put it through their lens.

There was this Matt Groening comic of academic types on the wall of the faculty lounge [at Harvard], and one of them was something like “The Single Theory Professor.” His single theory was: “He who controls magnesium controls the earth.” And [as a New York Times media columnist] I pretty much was like, I don’t want to quite become a “He who controls magnesium controls the earth” person. But I was getting there until I was able to see the loss that pushed back on the magic.

Do you still feel that there’s a magnesium trap that you’re avoiding?

No, it’s wonderful because the Internet so incredibly diverse that there’s always something new to read. There are these moments where I’ll realize something is sort of ascendant, like Snapchat. I download the app and sort of gear up, like “My brain has to change to take this in.” There’s always this excited panic where I’m just like, “OK, this time I’m just not going to get it.”

That’s the moment that I usually try to double down and say, “It’s my burden to see what this thing is.” Even if it takes me a lot longer than it used to get some followers and get a hold of a new social network, that’s my job as a human.

As a human? Not as a critic?

Right. As a human. We get one chance on this earth, and it’s like, how did this fucking Internet happen? I’m in awe every day. I can’t believe that, sitting in my chair, I can explore all that. It feels like an incredible privilege.

To go back to the idea of finding metaphors for the Internet, what’s the metaphor for your role? How do you understand your critical avatar?

I just feel determined to take the Internet seriously as a cultural paradigm shift. Not like a niche of technology or a business proposition, but a giant new empire that is, frankly, much bigger than any empire we’ve seen before.

I think my role is to take it seriously and also really consider this masterpiece, and to be there right with it—to somehow stay with it.

McDonald’s comes for sriracha: Assimilation, customization and the fast-food American Dream

(Credit: AP/Nick Ut)

Earlier this month, my husband and I were stopped at a red light, on our way to get Thai food, when the McDonald’s advertisement on a bus in the next lane caught my eye. “Awesome sauce?” I blurted, reading the copy beside an image of a succulent burger. “There’s sriracha at McDonald’s?

The so-called awesome, by the way, is a tangy mixture of sriracha and Big Mac sauce. A few days ago, in the name of journalistic integrity, I twisted my husband’s mostly-pescatarian arm and, before we knew it, we were in a drive-thru for the first time in recent memory, ordering Signature Crafted Big Macs with Signature Sriracha Big Mac Sauce. According to Hakeem, who collected our $12 and passed us our burgers, about three out of 10 people were ordering the sriracha Big Mac.

The burger verdict?

“It tastes like Arby’s,” one of us said.

“It tastes like pouring pain on my food,” said another.”

“I hate the potato roll! Who would eat this?”

“Is that arugula?”

“You mean rocket?”

The answer is no, not rocket, but kale, baby kale and spinach — according to a press release from the company, their “different approach to lettuce.” Other features of the Signature Crafted sandwich include white cheddar cheese, onions (I think they were meant to be crispy), and tomato, toppings that can be stacked on a “100 percent pure beef patty, Buttermilk Crispy Chicken or Artisan Grilled Chicken.” All of this, I suppose, adds up to “bold recipes with authentic ingredients” that “[allow] customers to customize each part of their sandwich.”

“Sriracha,” like “customize,” is a buzzy word in the food industry. In 2015, Hillary Dixler of Eater listed both in her article “11 Things Millennials Want, According to Giant Food Companies.” McDonald’s isn’t the first fast-food chain to co-opt jalapeño-garlic-sugar fire, but their adoption (and their verbiage … “Awesome sauce?”) feels a bit like when your parents first began using emojis: a little part of the cool died.

A coolness in which I never really took part. Yes, my husband and I keep a bottle of sriracha in our refrigerator (a preference, not a necessity); yes, I can tell you the non-GMO Ninja Squirrel Sriracha is sweeter than the Sky Valley competitor offered at Whole Foods; indeed, I can even recommend an artisanal, small-batch sriracha maker, The Kitchen Garden, out of Western Massachusetts (beware the caution-cone orange habanero variety). We use it frequently, in pasta and on pizza, with eggs and dumplings, to cut the cloy of macaroni and cheese. When it’s movie time, I melt butter and sriracha together until the mixture sizzles and coat popcorn until the kernels are ominously red. Like several of the aficionados with whom Griffin Hammond speaks in his 2013 documentary “Sriracha,” I have packed a bottle for lunch, the poor man’s acid reflux delight of baby carrots and rice cakes—and packed that lunch in a canvas tote bag from the aforementioned small-batch sriracha maker, emblazoned with their take on the sauce’s American originator’s logo, Huy Fong Foods’ rooster.

I can’t help feeling like the subjects in Hammond’s documentary would score my degree of sriracha gustation low on the Scoville Scale. Hammond shows sriracha T-shirts and sriracha stilettos, sriracha sweaters and sriracha tattoos, sriracha cookbooks and sriracha pilgrimages (to the town of Si Racha in Thailand, where tigers jump through flaming hoops and the sriraja sauce is thought to have its roots) and sriracha festivals (like the Electronic Sriracha Festival that marries hot sauce and EDM, which can be nothing other than sonic equivalent of that Sriracha Signature Big Mac Sauce).

The ephemera and the fan-perpetuated hype made sriracha a cult hit for years. But what happens when the condiment of the cool kids gets foisted through the golden arches and blandly deemed “awesome sauce”? What does the fanaticism it inspires say about our cultural values? As one young woman Hammond interviews in the opening minutes of his documentary puts it, “It’s an obsession, really.”

That obsession, one discovers with not too much research, is borne out of the labors of David Tran, the owner of Hoy Fong Foods in Irwindale, California. An ethnic Chinese who immigrated from Vietnam, Tran began making his take on the spicy hot sauce for Vietnamese restaurants in Southern California. In Hammond’s documentary, Tran recounts the early ’80s, when he painstakingly filled bottles with a single spoon and delivered his product to clients in LA’s Chinatown in a blue pickup.

The American-dream success story of Tran cannot be underestimated in supplying sriracha with its mystique. Since their inception in 1987, Hoy Fong Foods’ (named for the boat by which Tran left Vietnam) sales have been in constant acceleration, growing by 20 percent a year—without an advertising campaign. Unlike McDonald’s, Hoy Fong didn’t declare its sauce “awesome.” And yet the green-capped bottle with writing in “English, Chinese, Vietnamese, French and Spanish” and the drawing of a rooster (Tran was born in the year of the rooster) seems to have entered the stratosphere of icon on its own. Annually, the company sells some 20 million bottles.

But is sriracha the twenty-first century’s Coca-Cola, a food that represents multiculturalism and intensity, a Wunderkind both mainstream and counterculture? Surprisingly, the condiment may soon be cohabitating with the soft drink—on banned food lists. The fast-casual chain Sweetgreen recently announced sriracha would be removed from its menus (along with, less surprisingly, bacon). The problem with the rooster sauce? Likely, sugar, Georgina Gustin writes in National Geographic. Gustin is skeptical about the validity of this concern: “Sure, the second ingredient in Huy Fong’s Sriracha is sugar, the third is salt, and it has some scary-sounding preservatives. But to eat the Food and Drug Administration’s recommended limit for sugar consumption of about 12 teaspoons a day, you’d have to down half a bottle of Sriracha—enough, really, to blow your head off.”

Half a bottle sounds like a lot (unless you’re downing two or maybe three bottles in a Sriracha Challenge, a phenomenon that attracts millions of viewers on YouTube and merits its own examination for the wasteful idiocy it captures and celebrates)—but, then again, maybe it doesn’t. How much sriracha does the average American use? In my two-person household, a bottle is lucky to last a month. Each teaspoon-sized serving of Huy Fong sriracha contains one gram of sugar, which doesn’t seem so bad until you stop and think: When was the last time you put a measly teaspoon of sriracha on top of anything?

I can’t help wondering if Sweetgreen’s ban doesn’t point to something essential and weird about our diets. No, a preference for heat or spice is not inherently American—but the fervency with which we devote ourselves to foods goes beyond preference or even taste. The foods we eat and prepare reveal our identities: where we come from, who we are, who we want to become. What does it mean that we have become “obsessed” with sriracha? That we want to be able to customize all parts of our sandwich?

Perhaps sriracha is just a recent addition to “have it your way” culture. Is that “customization”? I am guilty of wanting that—which I dislike about myself. I don’t like that I can’t eat a piece of pizza without wanting it to have more flavor; I don’t like that I’m not satisfied with a bowl of ramen unless it’s burning my mouth. I’m not anti-seasoning, but I am pro-enjoying a variety of foods, for the gamut of tastes they run. I’m afraid of what we miss out on by habituating ourselves to add—add sriracha, add ketchup, whatever: either way, we’re homogenizing our taste buds.

A popular personality test found in the annals of the Internet is “Are You a Coke or a Pepsi?” These quizzes include questions like:

“You see someone alone….. what would you do?

Wait for them to come to me

Leave them alone

Introduce myself, and invite them over”

This kind of quiz gives me a bad feeling for the way it both downplays and overemphasizes the meaning of one’s soft drink of choice. I know, I know: it’s an Internet quiz. And it’s a soda. And it’s a hot sauce. But, I’ll admit it: After watching Griffin Hammond’s short 2013 documentary, Sriracha, I got a little creeped out. I like sriracha—I like it a lot. But I don’t want to be a hot sauce fangirl.

And whether you’re a fankid or simply a sriracha enthusiast, you probably want to give McDonald’s adoption of the condiment some reflection. With the popularity of the condiment, odds are this menu item is coming to a zip code near you; soon you’ll be able to add Signature Crafted Sriracha Big Mac Sauce to your Signature Crafted Big Mac. What does that mean? No one’s twisting your arm to go to McDonald’s, you might insist. Who even eats fast food anyway?

Well, 68 million people daily, if you’re Mickey D’s.

And yet: Americans value farm-to-table eating more than ever before. Will, if demand for their product continues to surge, Huy Fong Foods continue to use red jalapeños exclusively from Underwood Family Farms? At my grocery store here in LA, Huy Fong’s spot on the shelf is stickered with a starburst that says LOCAL! Will that, too, change? Does some of the little-guy-against-the-Man ethos vanish when sriracha becomes McDonald’s-mainstream?

Yes, and that’s only one cause for concern. (After all, there’s the problem of disambiguation. The name sriracha isn’t trademarked; anyone can grind jalapeños with garlic and sugar and salt, package it and sell it as sriracha. Or whip some up and keep it in their Paleo kitchen.) The corporate assimilation of “awesome sauce” by McDonald’s means the esoteric condiment gets folded into the ubiquitous blandness of Big Mac sauce. And you know what? The zing of the original gets lost, drowned in a tangy blah. There: That’s the sad, normalizing pinnacle of American success—that a trend, a taste, a single food can be engineered and commodified, made palatable enough for us all to be “lovin’ it.”

Republicans want a do-over: The GOP finds itself trapped in the date from hell

Donald Trump (Credit: Reuters/Lucy Nicholson)

Republicans, we know what you’re going through.

Many of us have been in this kind of relationship before: You meet someone new and he or she seems different, exciting, rebellious, maybe even a little dangerous. You get involved. Your friends say, “What do you see in him/her?” And you reply, “Oh, you just don’t know him/her like I do.”

But as the weeks and months go by, you start to realize he/she isn’t just a little dangerous. He/she is a menace. Time to re-evaluate.

As James Hohmann at The Washington Post’s Daily 202 writes, “Many Republicans who initially rallied around Donald Trump after he clinched the nomination are having second thoughts.”

What’s more, Hohmann’s Post colleagues Ed O’Keefe and David Weigel report that, with less than three weeks left before the Republican Party convention, “The candidate, his family and close supporters are expected to play starring roles. So will most top congressional leaders. But many Republicans who want to distance themselves from Trump’s incendiary rhetoric are refusing to attend. Past corporate sponsors such as Ford, General Electric and JPMorgan Chase have declined to participate.”

Bottom line, GOP, your presumptive nominee is the Date from Hell.

Members of the Bush family, including the two ex-presidents, are boycotting. Mitt Romney and John McCain won’t be there and neither will other incumbent senators who are in tough reelection fights this year. So GOP, let’s face facts: A lot of your friends are trying to tell you something about your relationship. In fact, a CNN poll conducted June 16-19 found that 48 percent of Republicans now would prefer a different candidate.

Bottom line, GOP, your presumptive nominee is the Date from Hell. As Republican National Committee Chairman Reince Preibus told Mark Leibovich, chief national correspondent forThe New York Times Magazine, Trump has “carved out this idea that he’s this earthquake in a box.” Unfortunately, that leaves the rest of us teetering on the fault line, just above the abyss.

Like the proverbial bad boyfriend, chaos ensues wherever Trump goes. Now that he’s about to be the party’s standard-bearer, he expects the Republican National Committee to do a lot of the work — “no national committee in recent memory has been called upon to pick up so much operational slack in a general election,” Leibovich writes — and to pick up the check much of the time, too, even though the committee has millions worth of debt and he’s not holding up his end when it comes to fundraising. Trump keeps talking about how much money he has and brags about his get-rich-quick schemes but doesn’t deliver. GOP, before you commit in Cleveland, you really should get a prenup — demand to see his tax returns and his bank statements. Otherwise, trust us, you can’t afford this guy.

And that’s not all. Love has blinded you to his many other faults, GOP. He says one thing, then says the opposite and when he’s called out on it claims he was misrepresented. Never admits a mistake. Makes outrageous accusations. Never seems to read anything that doesn’t have his name in it. Spends too much time with his pals on social media. Constantly and narcissistically talks about himself. Intolerant of others and angry all the time. Never takes responsibility — whenever bad stuff happens it’s always someone else’s fault.

And he keeps wearing that damned baseball cap.

Best to make a clean break, GOP. Run away from this fellow as fast as humanly possible. Leave skidmarks. Maybe you’ll meet someone else. Years from now you’ll be able to laugh about it. And chalk it up as a learning experience.

But you won’t, will you? You wish you knew how to quit him but you keep falling for the con. You think he’s smart because he says he’s rich, hates the same people you hate and makes promises that you love, even though they’ll never be kept and there surely will be tears before bedtime. The “stupid party” that ex-Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal warned about after the 2012 elections, plagued by the nativism, xenophobia and cynicism Trump represents (to slightly paraphrase President Obama’s words in Ottawa this week) has come to pass.

As the great Charlie Pierce recently wrote at Esquire, “Our politics are not supposed to be vulnerable to this kind of abject farce.” But here you are, GOP, stuck in a dead-end relationship with someone who, when all is said and done, may prove to be the very thing that Trump himself so loves to call other people: a loser. You brought it upon yourself through decades of encouraging rage and ignorance, ignoring the realities of economic inequality and social injustice and creating a government and politics of dysfunctional inertia.

And you wonder why you can’t meet a decent guy for once.

How worried do you need to be about early-onset Alzheimer’s?

Former Tennessee women's basketball coach Pat Summitt succumbed to early-onset Alzheimer's this week. (Credit: AP/Wade Payne)

You have forgotten where you put your car keys, or you can’t seem to remember the name of your colleague you saw in the grocery store the other day. You fear the worst, that maybe these are signs of Alzheimer’s disease.

You’re not alone: a recent study asking Americans age 60 or older the condition they were most afraid of getting indicated the number one fear was Alzheimer’s or dementia (35 percent), followed by cancer (23 percent), and stroke (15 percent).

And when we hear of someone like legendary basketball Coach Pat Summitt dying on June 28 from early-onset Alzheimer’s at age 64, fears are heightened.

Alzheimer’s is an irreversible, progressive brain disease that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills, leading to cognitive impairment that severely affects daily living. Often the terms Alzheimer’s and dementia are used interchangeably and although the two are related, they are not the same. Dementia is a general term for the loss of memory or other mental abilities that affect daily life. Alzheimer’s is a cause of dementia, with over 70 percent of all dementia cases occurring as a result of Alzheimer’s.

The majority of Alzheimer’s cases occur in people aged 65 years or older.

Slight memory loss is a normal consequence of aging, and people therefore should not be overly concerned if they lose their keys or forget the name of a neighbor at the grocery store. If these things happen infrequently, there is scant reason to worry. You most likely do not have Alzheimer’s if you simply forgot one time where you parked upon leaving Disneyland or the local mall during the holidays.

How do you know when forgetfulness is part of the normal aging process and when it could be a symptom of Alzheimer’s? Here are 10 early signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease.

A key point to consider is whether these symptoms significantly affect daily living. If so, then Alzheimer’s disease might be the cause.

For every one of these 10 symptoms of Alzheimer’s, there is also a typical age-related change that is not indicative of Alzheimer’s disease. For example, an early symptom of Alzheimer’s is memory loss including forgetting important dates or events and asking for the same information numerous times over. A typical age-related change may be sometimes forgetting names and appointments, but remembering them later.

People frequently ask if they might be afflicted with the disease if a grandparent had Alzheimer’s. The majority of Alzheimer’s cases occur in people aged 65 years or older. These individuals are classified as having what is known as late-onset Alzheimer’s. In late-onset Alzheimer’s, the cause of the disease is unknown (e.g. sporadic), although advancing age and inheriting certain genes may play an important role. Importantly, although there are several known genetic risk factors associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s, inheriting any one of these genes does not assure a prognosis of Alzheimer’s as one advances in age.

Early-onset is rare – but heredity does play an important role

In fact less than 5 percent of the 5 million cases are a direct result of hereditary mutations (e.g. familial form of Alzheimer’s). Inheriting these rare, genetic mutations leads to what is known as early-onset Alzheimer’s, which is characterized by an earlier age of onset, often in the 40s and 50s, and is a more aggressive form of the disease that leads to a more rapid decline in memory impairment and cognition.

In general, most neurologists agree that early-onset and late-onset Alzheimer’s are essentially the same disease, apart from the differences in genetic cause and age of onset. The one exception is the prevalence of a condition called myoclonus (muscle twitching and spasm) that is more commonly observed in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease than in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

In addition, some studies suggest that people with early-onset Alzheimer’s decline at a faster rate than those with late-onset. Even though generally speaking the two forms of Alzheimer’s are medically equivalent, the large burden early-onset poses on the family is quite evident. Often these patients are still in the most productive phases of their life and yet the onset of the disease robs them of brain function at such a young age. These individuals may still be physically fit and active when diagnosed and more often than not still have family and career responsibilities. Therefore, a diagnosis of early-onset may have a greater negative, ripple effect on the patient as well as family members.

Although the genes giving rise to early-onset Alzheimer’s are extremely rare, these inherited mutations do run in families worldwide and the study of these mutations has provided critical knowledge to the molecular underpinnings of the disease. These familial forms of Alzheimer’s result from mutations in genes that are typically defined as being autosomal dominant, meaning that you only need to have one parent pass on the gene to their child. If this happens, there is no escape from an eventual Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

What scientists have learned from these rare mutations that cause early-onset Alzheimer’s is that in every case the gene mutation leads to the overproduction of a rogue, toxic, protein called beta-amyloid. The build up of beta-amyloid in the brain produces plaques that are one of the hallmarks of the disease. Just as plaques in arteries can harm the heart, plaques on the “brain” can have dire consequences for brain function.

By studying families with early-onset Alzheimer’s, scientists now realize that the build up of beta-amyloid can happen decades before the first symptoms of the disease manifest. This gives scientists tremendous hope in terms of a large therapeutic window to intervene and stop the beta-amyloid cascade.

Hope is high for large trial underway of 5,000

Indeed, one of the most anticipated clinical trials under way at this moment involves a large Colombian family of over 5,000 members who may carry an early-onset Alzheimer’s gene. Three hundred family members will participate in this trial in which half of those people who are young and years away from symptoms but who have the Alzheimer’s gene will receive a drug that has been shown to decrease the production of beta-amyloid. The other half will take a placebo and will comprise the control group.

Neither patient nor doctor will know whether they will be receiving the active drug, which helps eliminate any potential biases. The trial will last 5 years and although it will involve a small percentage of people with early-onset Alzheimer’s, the information from the trial could be applied to millions of people worldwide who will develop the more conventional, late-onset form of Alzheimer’s disease.

Currently there are no effective treatments or cure for Alzheimer’s and the only medications available are palliative in nature. What is critically needed are disease-modifying drugs: those drugs that actually stop the beta-amyloid in its tracks. Devastating as early-onset Alzheimer’s is, there is hope that prevention trials as described above could ultimately lead to effective treatments in the near future for this insidious disease.

The convention’s invention: Freemasons and the mysterious dawn of a political instituion

(Credit: AP/Jae C. Hong)

The presidential nominating convention, that quadrennial blend of circus and speechfest, was originated not by the two major parties, but by a little-known and short-lived group who called themselves the Anti-Masons. How did this band of zealots come to found a national institution? The story revolves around a mystery.

In 1826, the Erie Canal corridor across New York state was bringing raging prosperity and not a little anxiety to a land that had recently been a frontier. The patriotic New England Yankees who settled the region were ultra-sensitive to intimations that the American Republic was losing its bearings.

In September of that year, Freemasons along the canal abducted a man named William Morgan. A disgruntled Mason himself, Morgan had written a book exposing Masonic secrets. He imagined a bestseller. Alarmed local Masons took the law into their own hands. They imprisoned Morgan in a disused fort on the Niagara River. A few days later, he disappeared. His fate remains unknown to this day.

It took a public outcry to move the authorities to apprehend Morgan’s abductors and probable killers. Most local magistrates, judges and sheriffs were themselves Masons. Masonic witnesses stonewalled the courts. Those convicted received trivial sentences. Outrage along the canal corridor grew.

Speakers at public meetings suddenly saw Freemasonry as an insidious conspiracy to replace government by the people with an aristocracy. The brotherhood was indeed top-heavy with citizens of means, although there were plenty of working-class members like Morgan himself. It was equally true that many prominent politicians, including New York Governor DeWitt Clinton, the canal’s champion, were Masons. But the notion of a Freemason plot was purely a product of the anxiety that rapid change was bringing to the newly opened lands west of the Appalachians.

The movement gained energy from the settlers’ enthusiasm for militant Christianity. An Anti-Masonic minister declared Freemasonry to be the “darkest and deepest plot that ever was formed in this wicked world against the true God, the true religion.”

Women had long resented husbands who devoted their time to lodge meetings, where liberal drinking was the rule. They helped energize a movement that quickly became a political groundswell. “Reason and religion equally demand [Freemasonry’s] overthrow,” one group of ladies proclaimed.

By 1831, the Anti-Masons had formed a political party and were ready to run a candidate for president. The question was how to choose a standard-bearer. The Constitution had made no provision for the selection of candidates, so parties were free to make up their own rules.

Beginning in 1800, the Congressional caucus of each party met to make the choice. This system was already outdated by the 1830s, and anyway the Anti-Masons had no members in Congress to form a caucus. Having built their movement through public meetings and state conventions, they quite naturally turned to the same means for choosing a candidate.

Not wasting any time, national delegates met more than a year before the election. The first ever presidential nominating convention opened in Baltimore in September 1831. The party selected William Wirt, a respected former attorney general (and a former Mason), to represent them in 1832. They also originated the formal political platform. Their statement of principles included an endorsement of public works spending, support for temperance, and insistence on the suppression of secret societies.

Members of the ailing National Republican party followed suit with their own conclave in December, tapping Henry Clay as their candidate. Although President Andrew Jackson was certain to be selected to run for a second term, the Democrats saw that the other parties had profited from the publicity and morale boost of a national meeting. The Dems held their first convention in March 1832.

William Wirt won only a single state, Vermont. He may have taken some votes from Clay, but it really didn’t matter–Jackson won handily. As more and more Masonic lodges closed their doors, the Anti-Masons suffered from their own success. The hyperbole that had fueled their anger began to ring hollow. Prominent party members, including political heavyweight William Seward, steered them toward other concerns, including the abolition of slavery.

By 1836, the Anti-Masons had become a powerful faction of the Whig Party, whose members joined with anti-slavery Democrats twenty years later to found the new Republican Party. In the contentious nominating convention of 1860, Seward lost out to an Illinois lawyer named Abraham Lincoln. The Anti-Masons disappeared; the convention proved a robust institution.

“We have a right to engage in non-violent action”: Christian leaders refuse to be silenced in struggle for Palestinian rights

A Palestinian woman passes by rescuers inspecting the rubble of destroyed houses following Israeli strikes in Rafah refugee camp, southern Gaza Strip. (Credit: AP/Khalil Hamra)

As is well-known by now, the unilateral decision of New York governor Andrew Cuomo to create a blacklist of businesses and organizations abiding by divestment and boycott campaigns related to Israeli human rights abuses has drawn widespread criticism for both its high-handedness and for its violation of constitutionally guaranteed freedoms. As might be expected, the response from civil liberties groups and groups advocating for Palestinian rights was swift and pointed. However, opposition also took the form of a letter drafted by the Reverend David Gaewski, New York Conference Minister, writing on behalf of the New York Conference of the United Church of Christ, a judicatory with 260 churches in the state of New York.

Noting the Church’s resolution to divest from “companies that profit from or that are complicit in violations of human rights arising from the occupation of the Palestinian Territories by the state of Israel,” and to “boycott goods produced in or using the facilities of illegal settlements located in the West Bank,” the letter actually asks that the church be put on the blacklist:

As a church, we have a right to engage in non-violent action to bring about change, including using economic leverage. All people and organizations have that right, and it is a right we must defend. For this reason, with the full support of the Board of Directors of the New York Conference of the United Church of Christ, I respectfully request that the New York Conference, United Church of Christ be placed on the top of your list of organizations you would like the state of the New York to boycott. Gov. Cuomo – stop denying our rights. Rescind your executive order now!

Gaewski told Salon that he wrote Cuomo because he felt “the executive order limits the rights and freedom of people of faith to enact faith-motivated actions toward peace. I am most concerned that the Governor is diminishing our freedom of expression.” He explained that what drives the Church’s commitment to Palestinian rights is the belief that “a separate society where Palestinians do not enjoy the same rights as any other person living in the region can not result in peace.” Gaewski added, “I think people of all faiths want to see peace in the birthplace of Judaism, Christianity and Islam.”

In fact, the discussion about what position to take with regard to Palestinian rights is taking place in several religious organizations, often as a continuation of many years’ discussion and action. In May the United Methodist General Conference, despite pressure from the State of Israel and even the admonishment of church member Hillary Clinton, passed a number of resolutions for justice of Palestinians. Also, as the New York Times reported in January:

The pension board of the United Methodist Church — one of the largest Protestant denominations in the United States, with more than seven million members — has placed five Israeli banks on a list of companies that it will not invest in for human rights reasons… It appeared to be the first time that a pension fund of a large American church had taken such a step regarding the Israeli banks, which help finance settlement construction in occupied Palestinian territories.

And in April the Alliance of Baptists “affirmed the use of nonviolent boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) strategies and comprehensive education and advocacy programs to end the 49-year Israeli occupation of Palestinian land.”

Most recently, at its General Assembly in Portland last week the Presbyterian Church (USA) debated several measures to address the injustices taking place in Israel-Palestine. This is a continuation of a discussion from the June 2014 meeting, when it narrowly passed a divestment resolution. As the New York Times put it, “The vote, by a count of 310 to 303, was watched closely in Washington and Jerusalem and by Palestinians as a sign of momentum for a movement to pressure Israel to stop building settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem and to end the occupation, with a campaign known as B.D.S., for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions.” What we are seeing now is that that momentum has grown even stronger, and not only amongst Presbyterians.

Several overtures (resolutions) sponsored by the Israel/Palestine Mission Network of the Presbyterian Church were passed, including “Advocating for the Safety and Well-Being of Children of Palestine and Israel,” “Calling for the RE/MAX Corporation to Cease Selling Property in West Bank Settlements,” “On Prayerfully Studying the Palestinian Civil Society Call for Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS)” and “For Human Values in the Absence of a Just Peace in Israel-Palestine.” It also urged Congress to hold hearings into the use of US military and police equipment by the government of Israel.

One other overture worth noting is “On Affirming Nonviolent Means of Resistance Against Human Oppression,” which points out that the PCUSA has a long history of using boycott and divestment as a way to side with those who are oppressed as well as to insure the integrity of its values and investments–the overture passed overwhelmingly in committee and in the plenary.

In its press release, IPMN noted two important aspects of the Assembly’s discussion. First, that CEO and co-founder of RE/MAX sent in a letter declaring, “RE/MAX, LLC will no longer receive any income from the sale of Jewish settlement properties in the West Bank.” Marita A. Mayer, who advocated for the overture, stated, “We’re pleased that RE/MAX is acknowledging that its operations in the occupied territories are problematic from a legal and moral point of view, but we’re waiting to see what this means in practical terms.” And with regard to BDS, IPMN notes, “the plenary of the General Assembly supported by over 70% a continuing study of the global grassroots BDS (Boycott, Divest and Sanctions) movement for Palestinian rights and freedom. Rejecting attempts to categorically reject BDS and choosing instead to engage in prayerful study, the General Assembly recognized the historic commitment of the Presbyterian Church (USA) to nonviolent strategies for social change.”

Geoff Browning, Peacemaking Advocate for the Presbytery of San Jose, told Salon :

We have made tremendous progress. We are working to educate the church about the suffering and injustice that is taking place, sometimes with our complicity of silence. I really believe that in order to advance the goal of divestment, we (the church, universities, etc.) are best served by asking our communities whether we want to profit from the harm caused to others. I sometimes hear opponents say something like, ‘Well, this is a complicated issue and we have no business taking sides or trying to resolve it. Our divestment won’t do anything to advance the cause of peace.’ Rather than trying to explain 60 years of occupation, I have found that it is much easier to simply say, ‘I agree that it’s complex, but can we agree not to profit from the suffering of others?’

And just a few months ago, the Unitarian Universalist Association divested from several companies due to their involvement in Israel’s occupation. As the advocacy group Unitarian Universalists for Justice in the Middle East (UUJME) noted in a press release at the time:

The UUA has adopted a human rights screen focusing on conflict zones that includes human rights violations in the occupied Palestinian territories. The UUA subsequently divested from Hewlett Packard Enterprise, HP Inc., and Motorola Solutions. The UUA has also divested from Caterpillar Inc., due to concerns over its environmental and social practices. These four companies have been the target of boycott and divestment campaigns due to their complicity in violations of Palestinian human rights.

At a time when politicians like Andrew Cuomo are not only not offering moral leadership on this issue, but rather exploiting it to carry out grandstanding (and illegal) acts, it is not surprising that these and other religious organizations are stepping up to fill that void. This is precisely what happened during the Civil Rights movement in the United States and the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa.

In 2014, Archbishop Desmond Tutu made this plea at a demonstration for Palestinian rights in Capetown:

I asked the crowd to chant with me: “We are opposed to the injustice of the illegal occupation of Palestine. We are opposed to the indiscriminate killing in Gaza. We are opposed to the indignity meted out to Palestinians at checkpoints and roadblocks. We are opposed to violence perpetrated by all parties. But we are not opposed to Jews.”

… I appealed to Israeli sisters and brothers present at the conference to actively disassociate themselves and their profession from the design and construction of infrastructure related to perpetuating injustice, including the separation barrier, the security terminals and checkpoints, and the settlements built on occupied Palestinian land.

“I implore you to take this message home: Please turn the tide against violence and hatred by joining the nonviolent movement for justice for all people of the region,” I said.

This act of refusing to be complicit with injustice, of breaking one’s ties to an oppressive regime, is what these religious organizations, and people of faith, are undertaking. And they are part of a much larger coalition of intellectuals, artists, writers, activists, trade unions, and organizations worldwide, appalled by the unfettered violence of the Occupation.

Millennials are ripe for socialism: A generation is rising up against neoliberal oppression

Bernie Sanders (Credit: AP/Craig Ruttle)

Few developments have caused as much recent consternation among advocates of free-market capitalism as various findings that millennials, compared to previous generations, are exceptionally receptive to socialism.

A recent Reason-Rupe survey found that a majority of Americans under 30 have a more favorable view of socialism than of capitalism. Gallup finds that almost 70 percent of young Americans are ready to vote for a “socialist” president. So it has come as no surprise that 70 to 80 percent of young Americans have been voting for Bernie Sanders, the self-declared democratic socialist. Some pundits have been eager to denounce such surveys as momentary aberrations, stemming from the economic crash, or due to lack of knowledge on the part of millennials about the authoritarianism they say is the inevitable result of socialism. They were too young to have been around for Stalin and Mao, they didn’t experience the Cold War, they don’t know to be grateful to capitalism for saving them from global tyranny. The critics dismiss the millennials’ political leanings by repeating Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan’s mantra, “There is no alternative” (TINA), which prompted the extreme form of capitalism we now know as neoliberalism.

But millennials, in the most positive turn of events since the economic collapse, intuitively understand better. Circumstances not of their choosing have forced them to think outside the capitalist paradigm, which reduces human beings to figures of sales and productivity, and to consider if in their immediate lives, and in the organization of larger collectivities, there might not be more cooperative, nonviolent, mutually beneficial arrangements with better measures of human happiness than GDP growth or other statistics that benefit the financial class.

Indeed, the criticism most heard against the millennial generation’s evolving attachment to socialism is that they don’t understand what the term really means, indulging instead in warm fuzzy talk about cooperation and happiness. But this is precisely the larger meaning of socialism, which the millennial generation—as evidenced in the Occupy and Black Lives Matter movements—totally comprehends.

Capitalism has only itself to blame, forcing millennials to look for an alternative.

Let’s recall a bit of recent history before amnesia completely erases it. While banks were bailed out to the tune of trillions of dollars, the government was not interested in offering serious help to homeowners carrying underwater mortgages (the actual commitment of the U.S. government was $16 trillion to corporations and banks worldwide, as revealed in a 2011 audit prompted by Sanders and others). Facing crushing amounts of debt, millennials have been forced to cohabit with their parents and to downshift ambitions. They have had to relearn the habits of communal living, making do with less, and they are bartering necessary skills because of the permanent casualization of jobs. They are questioning the value of a capitalist education that prepares them for an ideology that is vanishing and an economy that doesn’t exist.

After the Great Depression, regulated capitalism did a good enough job keeping people’s ideas of happiness in balance. Because of job stability, wage growth, and opportunities for mobility, primarily driven by progressive taxation and generous government services, regulated capitalism experienced its heyday during 1945-1973, not just in America but around the world. Since then, however, the Keynesian insight that a certain level of equality must be maintained to preserve capitalism has been abandoned in favor of a neoliberal regime that has privatized, deregulated, and “liberalized” to the point where extreme inequality, a new form of serfdom, has come into being.

Millennials perceive that what is on offer in this election cycle on the part of one side (Trump) is a return to a regulated form of capitalism, but with a frightening nationalist overlay and a disregard for the environment that is not sustainable, and on the other side (Clinton) a continuation of the neoliberal ideology of relying exclusively on the market to make the best decisions on behalf of human welfare. They understand that the reforms of the last eight years have been so mild, as with the Dodd-Frank bill, as to keep neoliberalism in its previous form intact, guaranteeing future cycles of debt, insolvency, and immiseration. They haven’t forgotten that the capitalist class embarked on an austerity campaign, of all things, in 2009 in the U.S. and Europe, precisely the opposite of what was needed to alleviate misery.