Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 736

June 27, 2016

“I shouldn’t have responded anyway”: Justin Timberlake apologizes for BET Awards tweet

Singer Justin Timberlake arrives at the 55th annual Grammy Awards in Los Angeles, California February 10, 2013. REUTERS/Mario Anzuoni (UNITED STATES - Tags: ENTERTAINMENT) (GRAMMYS-ARRIVALS) - RTR3DLOW (Credit: Reuters)

“Grey’s Anatomy” star Jesse Williams’ delivered a powerful acceptance speech at the 2016 BET Awards Sunday night after he received the Humanitarian Award.

“We know that police somehow manage to deescalate, disarm and not kill white people every day,” Williams said. “So what’s going to happen is we’re going to have equal rights and justice in our country, or we will restructure their function, and ours.”

Justin Timberlake was so #Inspired by Williams’ speech that he tweeted the following:

@iJesseWilliams tho…#Inspired #BET2016

— Justin Timberlake (@jtimberlake) June 27, 2016

This person voiced his exception to JT’s flimsy sentiment, calling the 35-year-old Grammy-winner a cultural appropriator:

So does this mean you're going to stop appropriating our music and culture? And apologize to Janet too. #BETAwards https://t.co/0FwBOQR24D

— Ernest Owens (@MrErnestOwens) June 27, 2016

To which JT said:

Oh, you sweet soul. The more you realize that we are the same, the more we can have a conversation.

— Justin Timberlake (@jtimberlake) June 27, 2016

Then backtracked:

I feel misunderstood. I responded to a specific tweet that wasn't meant to be a general response. I shouldn't have responded anyway…

— Justin Timberlake (@jtimberlake) June 27, 2016

I forget this forum sometimes… I was truly inspired by @iJesseWilliams speech because I really do feel that we are all one… A human race

— Justin Timberlake (@jtimberlake) June 27, 2016

Then apologized:

I apologize to anyone that felt I was out of turn. I have nothing but LOVE FOR YOU AND ALL OF US.

–JT

— Justin Timberlake (@jtimberlake) June 27, 2016

Watch Williams’ full speech here.

June 26, 2016

Reading Conrad with convicts: What I learned leading a book club inside a men’s prison

The author with the members of the book club

Excerpted from “The Maximum Security Book Club: Reading Literature in a Men’s Prison.”

For the last three years, I’ve been running a book club at a men’s prison. I started volunteering at the prison as a sabbatical project, but it’s become a long-term commitment. My fascination with this place and the men who inhabit it isn’t a new impulse; I’ve long been preoccupied with the lives of people generally considered unworthy of sympathy, especially those who’ve committed crimes with irreversible moral implications, like murder. Such people, more so even than the rest of us, are unable to escape the past.

Jessup Correctional Institution (JCI) was originally constructed as an annex to the huge Maryland House of Correction (better known as “the Cut,” after the path forged through a nearby hill during the construction of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad), a handsome but sinister-looking structure built in 1878 from local brick and stone. Now dismantled, the Cut was notorious for its harsh living conditions, violence among convicts, and frequent assaults on the guards. Most of the men currently incarcerated in JCI arrived there from other prisons, including both the Cut and the Maryland Penitentiary in downtown Baltimore, and they’ve often entertained me with tales of their past lives in these legendary establishments. When the Cut closed down in 2007, most of its inhabitants were moved to North Branch Correctional Institution in Cumberland, Maryland, a new supermax facility, and JCI went from being an annex to the Cut to becoming a prison in its own right.

To get there, I drive south from Baltimore on Interstate 95, take exit 41, and enter a semirural no-man’s-land dotted with administration buildings, truck stops, landfills, and industrial warehouses. These structures are separated by what looks from the highway like pleasant woodland but is in fact a dumping ground for unwanted electrical equipment and rusting industrial trash.

Arriving at JCI, I park next to one of the dark blue prison vehicles, which bear Maryland’s coat of arms and the motto Fatti maschii parole femine (“Manly deeds, womanly words”). I walk over to the front gate and show the correctional officer (CO) my paperwork and ID. If everything’s in order, I pass on to the next obstacle: the metal detector. Once the metal detector has given me the all clear, the CO gives me a full-body pat down and I turn in my driver’s license in exchange for a pink clip-on visitor’s badge. Next, I’m sent to wait by a glass sally port (a double set of mechanically operated steel doors) for a uniformed escort.

In 1994, Congress eliminated Pell grants for prisoners, effectively eliminating all college programs in U.S. prisons, including the one at JCI (In July 2015, the Obama administration announced that it was planning to reinstate a pilot Pell grant program to a limited number of prisoners seeking college degrees). I’m one of a small group of volunteers who continue to teach courses to incarcerated men at the college level (though not for college credit). Vincent, a trusted convict with a high level of responsibility, oversees the college program. JCI has no system of orderlies, but Vincent’s position is a close equivalent.

A slight, young-looking man of 53 with a closely trimmed beard, he has a quiet, casual dignity and speaks with intelligence and authority. Over his 30-plus years in prison, Vincent has earned his GED, and, through the kind of penitentiary extension programs that used to be common, an undergraduate degree in political science and sociology and an MA in humanities. From his cluttered desk in the school office, Vincent negotiates expertly and discreetly between the college program, the principal, the prisoners, and the librarian. It was Vincent who helped me put the book club together once I got my foot in the door, enlisting a group of respectful and literate prisoners, ensuring an appropriate racial balance, and negotiating personality conflicts. I made it clear to him that I wanted discussions in the group to be friendly and as open as possible, given the circumstances; that I wanted everyone to have the chance to speak if they wanted to; and that although we’d be talking about books, we’d also be learning about one another.

Vincent is a member of the book club himself, although his interests are closer to those of the other volunteers who teach in the prison college program, whose classes generally consider broader concerns about race, crime, justice, and similar issues. In fact, virtually all educators who volunteer their time in prisons— and perhaps elsewhere—are based in the humanities and related fields. This is not only because those drawn to these subject areas tend to have a more liberal, idealistic way of thinking—and are seldom paid enough to feel their wisdom is too hard earned to be given away for free—but also because these disciplines require no expensive equipment (unlike, say, classes in engineering, computer science, architecture, or medicine).

My subject is literature. For me, the prison was a new and compelling place for me to talk about books I love with people I wouldn’t otherwise get to know. I had no religious or political agenda, no cause to promote, no desire to liberate or enlighten. Nor was I interested in race, crime, power, or the politics of incarceration, although these subjects, among others, sometimes came up. More so than any of the other professors, I think, my interest in the prisoners was personal.

In Edith Wharton’s novel “The House of Mirth,” clever Lily Bart, in search of a husband, is “discerning enough to know that the inner vanity is generally in proportion to the outer self-depreciation.” At JCI, I learned the converse is also true: muscles can be a sign of sadness, tattoos can cover lack, and underdogs come in all shapes and sizes. I can’t claim a higher motive, a belief in literature as redemptive, as a way of helping the convicts understand the pain they’ve brought their victims. On the contrary, I saw the book club mainly as a way for me to share my love for the books that have come to mean the most to me.

Still, the motives that drive us are always complex, and we seldom have much insight into our own. It’s definitely a boost to my self-esteem to know how important I am to the prisoners, when these days my college students don’t even seem to know my name. But I also ask myself: How much does motive really matter? If even the apparently purest act of altruism—the anonymous donation, for example—has some form of payback, whether a private lift to the ego or a more complex unconscious reward, does it make the act itself any less beneficial to the recipient?

I doubt the men in my reading group would think so. These nine prisoners are smart and thoughtful, but they’re also tough, hard-edged, and practical. For them, the books we read seem to provide a kind of defensive barrier, as well as a bridge. It’s always easier to get to know people when they’re not talking about themselves directly, and I soon came to realize that when the men are talking about books, they’re also talking about their lives. The book club is a place where they can relax their posturing and defensiveness and, in the guise of discussing literature, talk unguardedly about their memories, the disastrous choices they’ve made, their guilt, and their remorse. They can bypass the usual ego games and reveal their affections and ambitions, their current and past dilemmas, the defining moments in their lives.

In talking about books, they can even broach otherwise taboo subjects such as drug use, homosexuality, and prison power plays. The group brings together men from different housing units, gang affiliations, and racial and religious backgrounds who wouldn’t normally spend time together. It’s a place and time that permits them to drop their social masks without exposing themselves completely. It’s a serious space, but one in which they can still joke, chat, act out, and tease one another (and me).

While I feel great sympathy and fondness for these men, at other times their attitudes bother me. They insist they want to learn and say they’re open to new ideas, yet on many subjects they’re already rock-solid in their opinions. Surprisingly, given their own predicament, they rarely have sympathy for those like Melville’s Bartleby—men they dismiss as losers in the battle of life. These prejudices often strike me as an impediment to understanding. I’ve always believed that, to remain open to the surprises and contingencies offered by literature, you have to value ignorance more than self-confidence.

As a result, I’m rarely fully convinced about anything, always able to see both sides of the argument. I try to stay open to the possibilities of not knowing because, in some ways, I think it’s the best frame of mind for reading: every idea, I realize, is open to change. When you believe you know what a book is all about—when a reading becomes fixed and determined—there’s no longer room for slippage, for accidents, for the play of the unconscious. The prisoners, however, see my openness as wishy-washy. If this is what you get from literature, they tell me, maybe it’s better to leave it alone.

Who wants to be uncertain and indecisive? At least they know where they stand.

That may very well be true, I reply, but look where it’s got you.

The ten books I chose to read with the prisoners—works by Conrad, Melville, Bukowski, Burroughs, Braly, Shakespeare, Stevenson, Poe, Kafka, and Nabokov—all deal with outsiders who strike out against society, asserting their individuality, right or wrong, against the blind force of “the system” (often the human condition). They’re all, in some way or another, subversive books that present familiar situations from a new perspective, letting us see the strangeness in the ordinary and everyday (a useful skill, you might think, for those trapped in a monotonous daily routine).

Most important, they’re books that don’t flinch from showing the isolation of the human struggle, the pain of conflict, and the price that must be paid in consequence—a price these men know only too well.

At first, I was surprised to find the prisoners’ responses to be so insightful, thought provoking, and articulate. Then I wondered why I’d been expecting any less from them because they’ve been in prison for most of their lives, or because they murdered another human being. Why do we find it so difficult to believe that men who’ve killed are as capable of literary appreciation as anyone else? Is it because we consider them fundamentally lacking in empathy? If a convicted murderer turns out to have a refined literary sensibility, might it suggest that his crime was caused not by an innate pathology but by the same kind of momentary bad decision anybody could make? If so, is it merely accident of circumstance that separates “the murderer” from “you and me?”

Our group discussions, and my background knowledge, helped place the books and their authors in a historical and cultural context; but to get a fuller understanding of them, the men had to read, reflect, and judge on their own, and in private. This is especially true, I think, of “Heart of Darkness,” a book that, to some degree at least, is a tale of disconnection from the community. Ironically, if anything in this obscure story is made more lucid by words, it’s our inability to make each other understand our experiences—as Conrad puts it elsewhere, to make each other truly see. (He also claims that “words, as is well known, are the great foes of reality.”) Marlow isn’t much of a storyteller (or so he claims), and yet he seems somehow compelled to share his experiences with his listeners—or at least, to make the attempt.

The more deeply he gets involved in his story, however, the more difficult he finds it to express himself. In the end, he begins to realize that we can’t share our experiences, coming to the conclusion that “we live as we dream: alone.”

Outside prison, the accepted, value-neutral word for an incarcerated individual is “inmate,” but within the prison gates, this word is taboo. The men at JCI taught me that in most American prisons, “inmate” is regarded as a euphemism coined by the prison authorities—the equivalent to the average slave of an “Uncle Tom.” “The difference between an inmate and a convict,” one of the men told me, “is respect.” Instead of regarding words like “convict” and “criminal” as demeaning, the prisoners saw them as honest descriptions of their position. In the pages that follow, then, I’ve adhered to this preference, and avoided the word “inmate.”

Jessup Correctional Institution is still officially a maximum security prison. However, its population is no longer made up of lifers with little to lose; in fact, there are only around four hundred lifers remaining. Over the last eight years, the facility has slowly been transitioning to medium security; currently, the prison houses around 1,750 prisoners, of whom around 100 are in the “maximum security” category. The book club contained a number of these men.

I use the term “book club” interchangeably with “reading group,” although I realize the two are rather different. While my group was aligned with all the other college-level courses (its official title was Advanced Literature), it was also different and separate from the other classes in the sense that it was limited to nine men, and has continued with the same members (as far as possible) for more than two years. It wasn’t a book club in the usual sense of the term in that I was the person who chose, purchased, and brought in the books, and I also asked the men to write a one-page weekly response about that week’s reading. Yet, despite the fact that I anchored our discussions by introducing the books and their authors and occasionally asked questions or identified passages for discussion, it wasn’t a “class” in the sense that I didn’t have anything to “teach” the men. I wanted to introduce them to some books they wouldn’t normally have encountered, and I wanted to hear what they had to say about them. As it turned out, most of the time I wasn’t leading the group but following, waiting for the chance to rejoin the discussion.

Given the many obstacles inherent in any prison environment, it would be unnatural if I did not, from time to time, find myself wondering why I’m giving up my free time to subject myself to the guarded and defensive behavior of the officers. Yet, every time I think about quitting, I realize it’s not an option—at least, not yet. The book club is teaching me to see literature in a way I’ve never seen it before. As often as I’ve discussed characters like Macbeth, Mr. Kurtz, Bartleby, and Dr. Jekyll—both as a student myself and as a professor—I’ve never done so with men who actually know what it feels like to kill from ambition, to take pleasure in other people’s pain, to look death in the face, to have nothing left to live for. Our conversations may be “only” about literature, but in them everything is at stake.

When I first read these books, I found them tough, because they made me confront difficult subjects: the inevitability of death, our ultimate aloneness, and the absence of any obvious meaning to life. Although they may not have been much fun to read, they helped me explore some very painful subjects, and allowed me to think about hard truths in a serious way. In time, I learned to appreciate the way books like these could lift the veil of subjectivity and, just for a moment, give me a glimpse into moments of other people’s existence. They helped me to become attuned to the inner life; they taught me to pay more attention to others, and, as a result, to think more deeply about the different dimensions of individual character and the moral consequences of my own behavior.

This, if anything, is what I hoped the book club would do for the prisoners. I also realized, however, that from their perspective these skills were of little use if they didn’t bring the men any nearer to the possibility of release, impress the parole board, or make them more satisfied with their lot. As one man put it to me when I asked why he was leaving the group: “All of what you do is great. However, it will not help me to get out of prison, where I have been for the past 25 years.” The rewards the book club offered these nine men were intangible and inexpressible, and I never lost sight of the fact that they would surely have preferred to spend their time learning something practical: computer skills, car mechanics, or carpentry, perhaps.

But literature was all I had.

The Kim Kardashian exception: Why her empire is constantly questioned—and Donald Trump’s isn’t

Donald Trump, Kim Kardashian (Credit: Reuters/Carlo Allegri/Mario Anzuoni/Photo montage by Salon)

The most recent round of publicity surrounding Kim Kardashian and the popular app of the same name spurred yet another debate about whether such profitable products constitute achievements on her part, and whether she is thus worthy of our professional respect. Those who’d say “no” do themselves no favors in reverting to lazy condemnations of the Kardashians’ best-known products, a series of reality television shows chronicling their lives. “Keeping Up With The Kardashians” is, of course, worthless entertainment. But it is merely the latest in a long line of stupid shows that are easy and somewhat pleasant to have on in the background. The same could be said of any number of other television programs that are not helmed by women, and that are not female-centric in their substance and marketing.

The strange vitriol directed at these particular stars and their fans is undeniably sexist. Football and boxing, say, are also immensely profitable, useless enterprises, enterprises whose fans also obsess to varying degrees of absurdity, which command a stronger emotional hold on their predominantly-male audiences than Kendall and Kylie ever could. And enterprises which, frankly, should face far more skepticism about their toxic effects on our culture from male media figures busy tweeting jokes about Kim’s nude selfies.

People’s amplified exasperation with Kim Kardashian’s fame and wealth stem from a sense that she’s undermined our conception of who gets, or ought, to be wealthy and famous. But this betrays a far more pernicious ideology: that Kim Kardashian is somehow an exception to a general rule that, by and large, good things happen to deserving people. This ideology, is, however, one that wealthy, famous people have a vested interest in promoting. In this sense, it is deeply irresponsible to grant subjects of reality television (or their mothers) producer credits, and thus control over a seemingly objective narrative. For a narrative is just that. It is a story. And stories are, by their very nature, lies.

With respect to Kim Kardashian, such storytelling might be relatively harmless. While it is inaccurate to dub her a successful businesswoman merely because a brand which bears her name has spawned successful businesses, the dangers of doing so are neither immense nor immediate. But for other such figures, the dangers are both vast and very real. A recent, gripping collection of anecdotes from former employees of Donald Trump’s competitive reality show “The Apprentice” highlights these dangers. One midlevel producer describes an overweight contestant who “would fuck up week after week…But Trump kept deciding to fire someone else. The producers had to scramble because of course Trump can never be seen to make a bad call on the show.” (Upon discussing the matter with Trump, he told another producer his reasoning. “Everybody loves a fat guy. People will watch if you have a funny fat guy around,” he allegedly said.)

One named producer noted that he might be violating a non-disclosure agreement in sharing his disturbing tales, but felt responsible for falsely engineering an aura of competence around a man whose presidential candidacy has flourished. “We might have given the guy a platform and created this candidate,” he said. “It’s guys like him, narcissists with dark Machiavellian traits, who dominate in our culture, on TV, and in the political realm.”

Yet somehow, despite every indication to the contrary, many continue to believe that if people are rewarded for behaviors then those behaviors have inherent value to our society. This kind of circular reasoning has pundits tying themselves up in knots to give Trump credit for savvily exploiting our political system, when Trump has never given us any indication that he possesses any savvy at all. This default mode of thought plays right into his tiny, childlike hands.

Instead of viewing wealth and fame with this socially Darwinistic lens, as though they confer a vague sense of moral legitimacy upon those who attain them, we should instead recognize the distinction between benefiting from complex systems and deftly navigating them. Fortune, fame, and power don’t necessarily imply skill. And assuming that traits which our markets, media, and political processes reward are necessarily admirable doesn’t just normalize bad behavior (or no behavior at all). It lends credibility to markets, media, and political processes as arbiters of what makes behavior good. If the systems most fundamental to our society are elevating the hopelessly unqualified, then we must reckon with the fact that those systems are broken. One hopes they aren’t hopelessly so.

Time to end these blood bans: U.S. policy on gay and bi male blood donations is a failure—and Canada is repeating the same mistakes

Justin Trudeau (Credit: Reuters/Chris Wattie)

Canada announced this week that the country plans to significantly reduce the waiting period imposed on gay men who wish to donate blood. The current policy stipulates that any man who has sex with men (MSM) is banned from giving blood if he’s engaged in sexual intercourse in the past five years. But according to officials, that will be lowered to just one year.

The change was approved after Canadian Blood Services and Héma-Québec submitted proposals that would bring the Great White North in line with countries like the United Kingdom, Australia, Sweden, France, New Zealand, and the United States, all of whom mandate 12-month blood bans. “These proposals included scientific data demonstrating that the change would not result in any reduction in safety to recipients of donated blood,” a press release from Health Canada stated.

The U.S. barred gay men from donating blood entirely until December of last year, when the Food and Drug Administration announced that allowing MSMs to donate—just as long as they’ve been abstinent in the past year. While a step in the right direction, that decision has nonetheless been a disaster, a policy as scientifically bogus as it is symbolic. Under the new FDA policy, a vast majority of gay men remain blocked from blood donation, because they remain labeled as a “high-risk” population. Under current guidelines, it’s easier for gay men to buy assault rifles than it is to donate blood.

Although there were reports that the group was reconsidering the policy following the Orlando shooting, those turned out to be false. That heartbreaking scenario—following the shocking deaths of 49 people at Pulse, a gay bar in Florida—has become de rigueur for a community that’s dealt with decades of discrimination from health agencies.

Robert Voss, a 30-year-old teacher in Chicago, was told he was ineligible because he’s in a monogamous relationship with another man, with whom he recently adopted a child. Despite being turned away, the blood donation center continued to call him and send him follow-up emails asking him to give. “I got sick of explaining myself,” he told Salon. LGBT activist Brandon Yan, who has a partner, told the CBC that this is a “huge commitment” to ask of gay men who just want to help those in need. “We would have to forgo being intimate, and having sex, and all those wonderful things … just to give this resource that is apparently so sorely needed,” he said.

If the Pulse shooting has exposed what an embarrassing failure the U.S. blood donation policies are, why would our neighbors to the North make the same mistake?

The case of Canada is extraordinarily unique when it comes to health policy. Over a span of about two decades, tainted blood made it into the general blood supply after thousands of donations were not screened properly by health professionals. This led to as many as 30,000 people, by some reports, becoming infected with Hepatitis C, while 1,100 more contracted the HIV virus as a result of industry malpractice.

Fallout from the crisis was extraordinary. Not only was the Canadian Red Cross—who was blamed for the scandal—fined $5,000 but the group additionally faced multiple counts of criminal negligence for exposing clients to disease, and a class-action lawsuit was filed in 1998. Dr. Roger Perrault, who then served as the director of the Red Cross, was put on trial for his role in the incident, but he would later be acquitted. Charges against the organization would be dropped, but backlash was so severe that the Canadian Blood Services was created to take the responsibilities of handling and testing blood away from the Red Cross.

That fiasco might explain why the country has been so slow to change. Canada first instituted its blood ban in 1977, and it wasn’t until 2013 that Canada allowed finally MSMs to donate. The change was ratified after a high-profile court case in which a sexually active gay man lied on his forms in order to be able to donate. He was sued by the CBS and counter-sued, charging that the policy was discriminatory and scientifically unsound. At the time, the Toronto Observer noted that HIV could be detected in the blood after just six months.

But 18 years later, advances in the health and medical industries that have made blood transfusion safer than ever, reducing the testing window to a period of mere weeks.

Diane Anderson-Mitchell, who serves as the editor in chief for PLUS magazine, told Salon that all donated blood has to be screened for a myriad range of infectious diseases, including Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C. Anderson-Mitchell explained that current technologies have made it simpler to test for HIV in the blood, which goes through a seven-day testing period, than these other viruses, which “take 25 days to screen for.” She said, “There’s this built-in safety factor right now with the testing we already do.”

The testing process for HIV is already extremely rigorous, as Anderson-Mitchell explained. Each blood sample is subjected to more than a dozen tests before it’s accepted. “When we know that blood goes through such long testing periods, you can really see that there’s plenty of time for them to test for all the HIV antibodies and antigens and know that blood is safe,” she said.

Magda Houlberg, who is the the chief clinical officer for Chicago’s Howard Brown Health Center, said that other models can be used to further increase that safety; she suggested waiting to submit the blood of “high-risk” populations to additional screenings. “When people donate sperm, they freeze the sperm and test you again awhile later and they used the sperm that’s been frozen,” Houlberg said. Instead, the current testing process relies on self-reporting, which can be extremely risky for blood donation centers.

“It’s more about the illusion of safety than it is about the reality,” Houlberg said.

Nonetheless, the risk of contracting HIV through a blood donation is already extremely low. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute estimates the odds are just 1 in 2 million, and those are unlikely to increase by shortening the deferral period even further—or doing away with it altogether. Countries like Portugal, Spain, and Italy all assess the risk of donors on individual bases, rather than on blanket policies. Italy did away with its gay blood ban in 2001, as Vice notes, and “has seen no higher incidence of HIV transmissions as a result.”

Even the Canadian Blood Services note on their website that their own 12-month ban isn’t based on recent advances in medical science, stating that the “window period is only nine days.”

According to government officials, Canada’s policy change is designed to be incremental. Jane Philpott, who serves as the country’s Health Minister, called the decision less of a “radical change” than a “step in the right direction.” She told reporters, “There’s an incredible desire and commitment on our part of the government to further to decreasing that donor-deferral period. … The desire is to be able to have those deferrals based on behavior as opposed to sexual orientation.”

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who campaigned on ending the blood ban once and for all, has stated that doing so is a priority for his government. “A Liberal government will work with Health Canada, CBS, and HM-QC to end this stigmatizing donor-screening policy and adopt one that is non-discriminatory and based on science,” he said in an official statement.

Dr. Dana Devine said that—for now, at least—keeping the deferral period in place for gay men was designed to assuage the fears of those giving blood. “The 12 months was where we had data to be still in the comfort zone for the recipients to feel that we were not doing anything that made blood supply unsafe [and] that we also had data to reassure ourselves that we were maintaining safety of the blood system,” she told the Toronto Star.

But until they do so, a compromise plan simply won’t be enough to answer the needs of a community that’s tired of being scapegoated and shamed, even during times of tragedy.

John Paul Brammer, a contributor to The Guardian, explained that policies like the one in place in Canada and the U.S. are a reminder that gay and bisexual men are still looked at like “agents of disease.” Brammer said, “It’s not that different from the Nancy Reagan era of dealing with AIDS. It’s so unfortunate, but it’s being propagated not only among straight people in our society but among gay people, too.”

He pointed to an a recent ad campaign in New York reminding MSMs to “know their status” as unfortunate example of how stigmatized this community is, even in 2016. According to Brammer, one advertisement “shows a gay man having sex with an actual scorpion—like a man-sized scorpion, and the stinger was coming out behind him—about to stab him in the back of the neck.” He continued, “It’s comparing people in our community—people who we cherish and who we love, who might be our brother, and who might be our best friend—to a poisonous bug that might kill you, something lethal.”

If, Brammer argued, a culture of misinformation and a lack of affirming education on HIV helps spread this fear, the most important thing we can do to stop it is to repeal policies that only help to further that stigma.

In the U.S., 24 Senators and 115 House representatives have urged the FDA to strike down its blood ban completely. These legislators include Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT), Rep. Katherine Clark (D-MA), Rep. Keith Ellison (D-MN), Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-NY), Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-CA), Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-CA), and Rep. Jared Polis (D-CO). Polis, who is openly gay, sent a letter to the organization urging them to listen to the LGBT community, who have virulently protested the ban for decades. “They just need to hear the public outcry about this policy and move expeditiously to change it,” he told CNN.

Following the tragic attack on Orlando, gay and bisexual men aren’t just devastated. They’re angry, and they want do something about this horrific attack on LGBT people by giving to those in need. It’s time for countries like Canada and the United States to finally let them.

Sea-cleaning prototype uses huge, floating screen to sift plastic out of the ocean

(Credit: AP/Julio Cortez)

A nonprofit foundation based in the Netherlands has launched a prototype for one of the most ambitious sea-cleaning projects yet. The innovative idea is a floating barrier that will gather the mass of plastic bits from bottles, bags, fishing nets and other trash that sloshes around in the oceans, growing every year. Once deployed, the extremely long barrier could eliminate the need for an army of boats to haul our garbage back to shore.

The 100-meter-long prototype was towed out to the North Sea today, where The Ocean Cleanup foundation plans to perform a yearlong series of tests. If the long boom succeeds, the group plans to deploy a full-scale, 100-kilometer-long version between Hawaii and the U.S. west coast in 2020, a section of the Pacific Ocean that has one of the densest deposits of plastic worldwide. “This is a big step toward cleaner oceans,” says Allard van Hoeken, chief operating officer of The Ocean Cleanup. “We’ve done years of computer modeling and successful simulations, and now we’re ready to test our technology in real ocean conditions.”

The aim is to monitor how the barrier will hold up in rough ocean currents and gale force winds, so that the full-size device can be built to endure challenging conditions and still effectively collect trash in a much larger area. The test barrier is made up of a chain of rectangular pillowlike rubber buoys that keep the barrier afloat, like a traditional boom that cleans up oil slicks, along with a two-meter-deep screen extended below the surface that forms a curtain that will passively collect trash as water washes through it.

The prototype will be arranged in a straight line just 23 kilometers off the coast of The Hague so that researchers can mimic the amount of debris in the Pacific by throwing biodegradable plastic objects into the sea and checking how quickly they are blocked by the barrier. A cable system will moor the eventual barrier so that it forms a long, flat-V shape; that way debris carried by the ocean current will get concentrated at the center of the V. This will allow easy removal and recycling of the accumulated plastic waste, van Hoeken says.

According to a 2015 study by the University of California, Santa Barbara, nearly eight million metric tons of plastic end up in our oceans each year. Debris from North America’s west coast is picked up by swirling ocean currents, called gyres, which carry it away until it becomes trapped in a revolving spiral about the size of Texas that is now known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. The amount of plastic waste keeps accruing because most of it is nonbiodegradable. “Small pieces of plastic can break down over time and become microplastics,” van Hoeken says. “These tiny plastics can easily enter the food chain and will cause harm if we don’t do anything about it.” Turtles, fish, dolphins and others not only become entangled in new plastic waste, they can swallow microplastics believing the refuse is food.

Cleaning up plastic pollution is not easy. Using ships to dredge the debris is extremely expensive and time-consuming. Nets designed to scoop up trash often ensnare marine animals as well. The Ocean Cleanup says its seamless barrier offers a much cheaper and sea life–friendly alternative. If successful, van Hoeken estimates it could halve the size of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in 10 years.

Others remain skeptical of the floating barrier because its effects on the ocean ecosystem have not been studied yet. “It’s two meters deep, so a lot of organisms can swim under it, but you’re basically creating a gigantic floating object that still has the potential to attract and affect the distribution of top predators and other animals,” says Jeffrey Drazen, a marine ecologist at the University of Hawaii at Mnoa.

“It’s great that folks are trying to come up with mechanisms of trying to clean up the ocean,” Drazen says. Yet he notes that the amount of plastic floating at the ocean surface is only a small fraction of what’s in the deeper water column. So in addition to clean up projects like this one, he adds, “we need substantial efforts to curtail the production and use of plastics. That has to be part of the conversation.”

This article was originally published by Scientific American.

“Game of Thrones” needs a new big bad: With Ramsay out of the way, a villainous void must be filled

Emilia Clarke, Pilou Asbæk and Lena Headey in "Game of Thrones" (Credit: HBO)

“Your words will disappear. Your house will disappear. Your name will disappear.” Sansa Stark’s final words to Ramsay Bolton, the man who raped and tormented her—spoken before she sics the dogs he has weaponized through cruelty and starvation upon him—are as sharp and penetrating as the fangs cracking through his jaw: All he has wanted (beyond getting his jollies castrating captives and hunting young women), is the legitimacy and power afforded by a house and a name. So Sansa hasn’t just defeated him, she has erased him. And her final f-you is cathartic in a meta way—it speaks to the relief that viewers feel now that Ramsay Bolton will, at long last, disappear from “Game of Thrones.”

As a big bad, Ramsay had become a little bit boring: In the last two seasons, particularly, he was more like the shark from “Jaws” than a fully-realized character—existing as a dark fin cutting through the water, a set of teeth gnashing up from the depths. His story cycles followed the same downward spiral: Through an ultimately uninteresting confluences of superhuman cunning and plot contrivance, Ramsay captured one of our protagonists and tortured them, or he killed and connived to reach some newer echelon of prominence. Lather. Rinse. Repeat. If these scenes had been more selectively deployed, or been perpetrated by a more deftly rendered villain, they would have retained their power to shock us—instead of becoming a cheap pastiche of grotesquerie, like the opening credits to a show called “That’s So Ramsay!”

Sadly, the erstwhile Bolton bastard had potential to be a truly compelling antagonist—if developed further, his desperate need for his father’s approval, and his recognition that even with that approval, his position was always tenuous, ever-threatened by the arrival of a true-born son; his grinding resentment that a man of his intelligence will always be subordinate to the manor-born, could have woven some gray threads into the tar-dark tapestry of his actions. The failures of the writers and showrunners to vest Ramsay with any complexity is particularly curious, given that “Game of Thrones” has excelled at crafting some of the most deeply-shaded antagonists on television. Take Cersei Lannister’s trial by the Faith Militant: Though fans clamored for the Cleganebowl, that epic final battle between the Mountain and the Hound, there seemed to be sparse speculation about who, exactly, we wanted to win in that trial by combat—since the Mountain would be Cersei’s champion and the Hound would be fighting for the Faith. This ambivalence can be attributed, of course, to the mutual awfulness of Cersei and the High Sparrow—and yet, there are also legitimately compelling reasons to root for each one to emerge victorious.

The High Sparrow is a religious bigot who cloaks his lust for power in a dirty sack cloth; though he talks a good game about equality among the social classes, he holes up in the fortified Sept of Baelor, and for a man who claims to have no need for earthly vestments, he’s sure interested in cozying up to the crown—even to the point that he creepily insinuates that Queen Margaery better to get to that baby makin’. Still, that doesn’t mean that all of his rhetoric is inherently wrong: The ruling elites are truly incompetent and corrupt, and they deserve to be supplanted. Daenerys Targaryen talked of “breaking the wheel” upon which the world of Westeros spun—the same families taking turns as victors and victims, and taking the smallfolk down with them—but the High Sparrow has actually snapped the spokes along his knee. Even Olenna Tyrell, the Queen of Thorns, admits as much when she curses Cersei for causing the ruin of both their houses.

Cersei’s current predicament is a natural consequence of her own actions—after all, she tried to turn the Faith Militant into her own pack of attack dogs, turning them on her son’s new bride, a younger queen, before they reared around to bite her in turn (and there is a bitter irony in Cersei’s son, King Tommen, repeating, in earnest, the same lines about the crown and the faith that she first fed the High Sparrow). And if Cersei’s subsequent imprisonment, walk of shame, and impending trial don’t feel exactly like justice, then her punishments are, at least, the backhand of karma leaving a mark—for giving power to zealots to satisfy a petty grievance, for raising Joffrey to be, well, Joffrey, and for orchestrating the murder of her husband the king (kinslaying and kingslaying, with one drop of poison), tipping the dominoes of horror and war throughout the seven kingdoms. Still, as her brother-lover Jaime points out, the nature of her “penance” is absolutely gendered—he’s guilty of many of the same charges (especially king-slaying and incest), and yet he hasn’t been paraded naked through the streets, his flesh the receptacle of the commoners’ rage.

In this way, Cersei’s blood feud with the High Sparrow is a simulacra of her story as a whole: Her woes originate from her own undercooked schemes, and are compounded by the violent sexism of her times (which reflects the violent sexism of our times). We cheer Sansa Stark’s Straight Outta “I Spit on Your Grave” revenge on Ramsay Bolton, but Robert Baratheon also beat and raped his wife. By this logic, in its coldest, most basic form, can we really begrudge Cersei her own vengeance? Yes, her methods may be sloppy and short-sighted—if she hadn’t chosen violence (however good it felt), and simply met the High Sparrow at the sept, then she’d still have trial-by-combat to save her skin—then again, she never received proper tutelage in the finer arts of trickery. Her father, Tywin Lannister, was a master strategist; however, he wouldn’t deign to mentor a girl, even his own daughter. Sansa may have been sold into marriage by Petyr “Littlefinger” Baelish, but he still managed to teach her a thing or two before she went head-first into the fray.

This season, Tywin’s ignoble death is fodder for (literal) potty humor during a Braavosi play—and the crowd-pleasing howler about Tywin Lannister shitting gold is a wry inversion of his former infamy as the architect of the Red Wedding and, before it, the man for whom “The Rains of Castamere” was written. Though his legend within Westeros is now distilled into the singular image of the most powerful man in the realm (because everyone knew that he was more than the Hand of the King, but the hand that held the nation) dying on a toilet, spurting something that was decidedly not gold as he breathed his last, his absence has created a real void on the show. It’s a fitting punishment for all eternity, perhaps; it doesn’t dilute the truth that Tywin was the rare antagonist with charisma to match his ruthlessness, and an immaculate, almost delicate sense of cruelty. But there’s also a robust pragmatism to that cruelty; he orchestrated the Red Wedding to humiliate his foes, and to, in a perverse way, save lives. “Explain to me why it is more noble to kill 10,000 men in battle than a dozen at dinner,” he quips to his son, Tyrion.

This chess player’s pragmatism is lacking in Littlefinger, (at least in the past two seasons; his endgame in giving Sansa to the Boltons remains too inscrutable to seem like anything other than the gears of plot grinding insensibly into motion), and certainly in Ramsay, who the showrunners wanted to position as another all-pervasive baddie. But Ramsay’s characterization was wildly discordant—he swung from being a random sicko who’d use blunt physical torture to achieve his ends to a brilliant tactician and manipulator whenever it was convenient. Tywin and Cersei and even, in his way, the High Sparrow are realized, and lived-in, enough, to be consistent in their actions and reactions; this consistency breeds familiarity, and even if that familiarity breeds contempt, it still makes them human. And being human—not an automaton of terror—makes them all the more compelling (and frightening).

Temperamentally, Ramsay is closest to Joffrey (I imagine they’d have a lot to talk about, wandering through the seven Hells), although Joffrey was a more watchable villain because his brattish ineptitude coaxed out the very best in the characters around him. That brilliant and oh-so-versatile GIF of Tyrion slapping him comes to mind; however, Joffrey also provided a showcase for the resourcefulness (and delightful deviousness) of the Tyrell women. One could even argue that his unrepentant awfulness gave Cersei a platform to demonstrate her maternal ferocity—she would be devoted, to the death, to the vilest of sons.

Ramsay didn’t inspire anything except fear and dread—and, in the viewer, boredom. As he is humbled before Sansa, bloodied and bound, he tries to get his last licks in, tells her that he is part of her now. That may be true for her (whether you’re a literalist who takes this as a sign that Sansa is pregnant, or believe it to be a metaphoric expression of how she’ll always live with all that he’s done to her), but I highly doubt it’s true for the show. If Tywin’s death created a void, then Ramsay’s is an open field, ready for planting—and the seeds of finer menaces are already available. Cersei’s trial should tender some resolution to her conflict with the High Sparrow, and the aftermath will be compelling. Euron Greyjoy does promise a bawdy swag that, in small doses, could be fun to watch.

Although, perhaps the most tantalizing antagonist-in-waiting is the dragon queen who believes, unquestioningly, in her fundamental rightness—even if proving that rightness means deploying a nuclear blast of dragon-flame upon cities full of innocent people. If the show does go this route—and the numerous references to the character who has been the paterfamilias of Big Bads, Daenerys’ father, Mad King, Aerys, seem to suggest that it will at least flirt with the idea of the breaker of chains breaking bad—it will be one of the most daring, provocative feats of the series. After all, as Harvey “Two Face” Dent, another all-time classic villain (albeit from another universe) once warned us, there’s nothing worse than living to see yourself as the villain.

Cameron Crowe’s living soundtrack: “For my scenes, he would do a Bob Dylan song or an Elvis Costello song”

Peter Cambor as Milo in "Roadies" (Credit: Showtime/Mark Seliger)

Shows set in the music industry can hit you in a visceral, vulnerable place.

Jussie Smollett on “Empire” and Connie Britton on “Nashville” have added layers to their characters in performance scenes that you just can’t get any other way. Even in shows that aren’t musicals, the right song over the right scene — like the “Devil Town” montage on “Friday Night Lights” and Sia’s “Breathe Me” in the “Six Feet Under” finale — can evoke an emotional response than a classical score can’t touch.

(I could go on. Don Draper buying the world a Coke was one of the best series endings in TV history. Jim and Pam’s “Forever” wedding montage reduces me to mush in a good way, and the “Hallelujah” scene on “The West Wing” just reduces me to mush. Also, if Coldplay’s “Lost” doesn’t do something for you when that helicopter takes off on “Ugly Betty,” you’re dead to me.)

You know who likes a good musical cue? Cameron Crowe.

The boombox scene in “Say Anything” is one of the most famous in film history, and it’s no coincidence that his better films — “Singles,” “Jerry Maguire,” “Almost Famous,” “Vanilla Sky” — are the ones with the best use of music. In Crowe and J.J Abrams’s new series “Roadies,” which premieres Sunday night on Showtime, there’s one of those scenes.

Imogen Poots, who plays an aspiring documentary maker and one of the roadies, is making a compilation of film characters running — like Tom Hanks in “Forrest Gump” and Cary Grant in “North by Northwest.” Crowe intercuts that footage into a pivotal scene late in Sunday’s premiere episode with Pearl Jam’s “Given to Fly” crescendoing over it.

Peter Cambor, who co-stars in “Roadies,” sat down with Salon to talk about the role music plays in the series, working with Cameron Crowe, and working on his British accent.

When you don’t have a beard, you’re a dead ringer for B.J. Novak. Have you ever heard that?

My facial structure spawns a lot of comparisons. When I was younger and a little more dashing, I would hear Ben Affleck, Paul Rudd and sometimes Jason Segel. I’ve never heard B.J. Novak, but I’ll take it. He’s a handsome, funny guy!

You have a huge beard on “Roadies.” Was that yours, or did you need a fake to be able to do other work while you were shooting?

The beard got cast before I did. Cameron always had that in mind for Milo. I got the part beardless, and then Cameron said, “Do you mind growing a beard?” I don’t think I’ve ever had a beard for this long and it’s a big lumberjack beard, so I get some looks now when I go audition for other parts.

Your character on “Roadies” is the guitar tech, which is stereotypically the blue-collar, burnout, loner type. Are you inverting that? Playing with parts of that?

The term “roadies” is from a bygone era. They’re called “techs” now. They’re still eccentrics, but they’re thoughtful, intelligent people. A lot of the techs I’ve met have a mastery of the instrument that’s pretty phenomenal. One of our technical advisors can take apart a soundboard, a pedal, a guitar, a bass — they’re like the guys on “Car Talk.”

Did the casting notice say you had to know how to play guitar?

It didn’t, but it helps. I was in “Wedding Band” a few years ago on TBS, and it’s been helpful over and over in my career.

Bad Robot, which is one of the show’s producers, has a reputation for being secretive about scripts. Did you get to see the full script of the pilot before you auditioned?

I did. That is true that they’re pretty secretive, but everyone is so secretive now. The internet has changed things so much. Actors used to get physical scripts, and now they’re all watermarked. There’s something kind of great about that, though. On a show like this with a topic that’s never been done, you really don’t know what’s going to happen as they season unfolds.

My attitude about spoilers has changed a lot over the last few years. If you’re online a lot, you’re going to see things. I’m not watching now to be surprised as much to see things happen.

Here’s my feeling about spoilers: It’s a great way to temper your internet usage. If it’s something you really don’t want to know about like a “Game of Thrones” episode or “Penny Dreadful,” which I really liked, you have to purposefully not scour the internet. I like the notion of binge-watching, but I hate it when I find out about something.

In your last four shows you’ve hit the four big TV platforms. You did “Wedding Band” for cable, “NCIS: L.A” for network, “Grace and Frankie” for streaming, and “Roadies” for premium cable. Have those shows all felt like they were made for their platforms?

There’s so many levels to that. I moved to Los Angeles in 2006, and the way we consume media has changed so much. I did a show on ABC [“Notes From the Underbelly”] that was on for two seasons, and it was the old, old style. You tune in on a certain night, and you watch it. Six million people a week watched that show, and it did a 2.6, 2.7 in the 18-49 demo. Today, that would be a monster hit.

In the pilot-season format, you pick up a bunch of shows and see what works. Shows for Netflix and Showtime spend a great deal of time in development. The networks know that these shows take time. They have to blossom into what they’re going to be. Cameron and J.J. started talking about this project eight or nine years ago, so they’ve spent a lot of time on this.

You have a fake British accent on the show that everyone seems to know is not real, which I’m sure they show will explore. Did you try to learn a good British accent?

When I auditioned for the part, the idea was that it would be the way people like Madonna have taken on a British accent in the past. Milo’s backstory is that he had been on tour with Elvis Costello and is someone who has aspirations to be out there performing himself. He’s a chameleon who takes on personas. For me, I had to really try, like “I’m British now.” I really worked on it to try and make it as real as possible knowing that it would be just OK.

Imogen Poots on the show is British but playing an American on the show. Are there scenes in later episodes where you’re talking to her in a British accent and she’s talking to you in an American accent?

Yeah, and it’s funny. Imogen will ask me how to say things with an American accent, and I’ll ask her how to say things in an English accent.

This morning, I heard Peter Kafka’s interview with Malcolm Gladwell , who has a new podcast series. Gladwell said in the context of podcasts that our eyes are rational but that our ears are emotional. Does that explain how music on a TV series hits you in a different place than plot and characters?

I love Malcolm Gladwell, and I’m a big podcast fan. That makes a lot of sense. If you watch any Cameron Crowe film, you see what an amazing soundtrack he brings. He creates iconic moments — Jerry Maguire driving down the highway to “Free Falling” or “Tiny Dancer” in “Almost Famous.”

When Cameron is directing, he plays music between takes. Depending on what the scene is, he’s have a particular song. He’ll have a song that’s in tune with the scene we’re shooting. For my scenes, he would do a Bob Dylan song or an Elvis Costello song or some obscure Jeff Tweedy cut. He’s putting that into the fabric of the show. The music is ingrained in that.

There’s a montage late in the pilot episode that’s tracked to Pearl Jam’s “Given to Fly.”

It’s sooo good.

I know Cameron Crowe is a big Pearl Jam fan. Is that who the band in “Roadies” is based on?

The band is like Stillwater from “Almost Famous.” It’s an amalgam of a lot of bands, and Pearl Jam is definitely part of that. One of our advisors was with Pearl Jam for a long time. Cameron has described it as being The National, My Morning Jacket, Pearl Jam — indie bands that can sell a place out. In this weird place that the music is in now, you make money by touring and not by selling albums. It’s a brave new world, and the band on the show is confronting that reality.

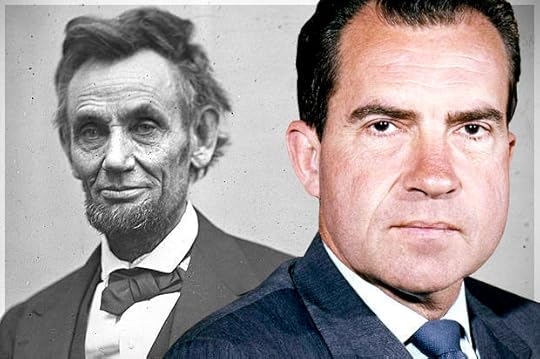

All the president’s friends: A history of close presidential allies, from Lincoln to Nixon to Trump

Abraham Lincoln, Richard Nixon (Credit: AP/Alexander Gardner/Salon)

Jonathan Mahler and Matt Flegenheimer in their New York Times article posted online Monday, June 20, reminded us of Donald Trump’s close friendship with Roy Cohn. Long reviled on the left, Cohn was Senator Joe McCarthy’s “Red-baiting consigliere” in the 1950s, was instrumental in sending the Rosenbergs to the electric chair, and helped get Richard Nixon elected. He later served Trump in many legal and personal capacities. Cohn liked to boast that he made Trump successful. There is probably no more despicable figure in American life from the 1950s to the 1980s. Cohn was justly disbarred shortly before his death in 1986 for “unethical,” “unprofessional,” and “particularly reprehensible” conduct.

Cohn was also Donald Trump’s lawyer and probably his best male friend. For many years Trump kept an enlarged picture of Cohn on his desk. Cohn, who could be equal parts fearsome and outrageous, handled Trump’s difficult legal issues by scaring off potential plaintiffs. The two men went to baseball games, had lunch at “21,” and partied often.

It is a mark of the difference between the primaries and the general election that this kind of good investigative journalism by Mahler and Flegenheimer is now appearing. Why wasn’t Marco Rubio, or Ted Cruz, or any of the other weak and intimidated Trump opponents looking into such things?

Most presidents need someone they can trust with whom to relax and share their real feelings about the extraordinary happenings in their lives. Many, like George W. Bush, Ronald Reagan, Jimmy Carter, or Woodrow Wilson turn inward to their wives to play this role. Who else, they seem to feel, can you really trust? Richard Nixon’s special friendship with Bebe Rebozo, who was also corrupt, stands out as the exception, though Franklin Delano Roosevelt surrounded himself with male and female friends in a social world in which no one, except perhaps his mistress, Lucy Mercer, got close.

Then there is Abraham Lincoln. Always somewhat aloof from his troubled wife, Mary, Lincoln turned for close friendship to a series of men who played a vital role in his life. During the Presidency, no one was more important in this regard than Secretary of State, William Seward. But for many years before that Lincoln had a way of making his male friends all feel they were uniquely significant in his life, from men like Bowling Green or the Clary Grove boys in New Salem; to Orville H. Browning and William Herndon in his Springfield days; and to the shrewd, rotund judge, David Davis, on the 8th Judicial Circuit.

But no one mattered for Lincoln as much as his best male friend, Joshua Speed. The two lived together from 1837 to early 1841, sleeping in the same bed above Speed’s store on the west side of the square in Springfield, Illinois. Such arrangements were hardly uncommon at the time and all the (good) historical evidence suggests both men were heterosexual and sought relationships with women. At the same time, both struggled with issues of intimacy and depression.

This friend helped stabilize Lincoln in his moratorium of delayed identity formation. Speed’s imminent departure from Springfield in early 1842 threw Lincoln into a panic. He was unmoored, alone, lost. In that confused state, which he barely understood himself, Lincoln withdrew from his fiancée, Mary Todd, and broke off the engagement for his marriage that was to be on January 1, 1841. After what he would call his “fatal first,” Lincoln became deeply and clinically depressed and definitely suicidal. He took to his bed at the home of William Butler. His friends—Butler, Anson G. “Doc” Henry, and of course Speed–removed his razor and other sharp objects from the room and set up a kind of suicide watch. Lincoln became wild and unhinged, hallucinated, stopped working, and became “crazy as a loon” in the words of Butler.

A year later, Speed’s own marriage to Fanny Henning elicited Lincoln’s vicarious identification with what emerged as Speed’s own doubts about his capacity to follow through with his marriage. It was all quite dramatic, and the letters Lincoln wrote Speed at the time are by far the most personal and psychologically revealing of anything he ever wrote then or later to anyone.

But in the end Speed did manage to marry Fanny Henning, which seemed to free Lincoln to return to his courtship of Mary Todd, who had graciously waited for him to wrestle his demons to the ground. After his marriage, Lincoln was never again suicidal, though he tended to the melancholy.

It is a remarkable story of a young great man finding himself. He was saved by his smart, kind, honest friend, Joshua Speed. Lincoln had no Roy Cohn whispering in his ear.

It’s a crime: How private prison companies encourage mass incarceration

(Credit: Reuters/Joshua Lott)

In February 2010, falling prisoner numbers caused the country’s largest private prison company, Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), to shutter its only facility in the state of Minnesota. The company knew that every day Prairie Correctional Facility in the rural city of Appleton would sit empty, it would incur operating expenses without generating revenue. Even before the facility officially closed, CCA had begun seeking new people to imprison there.

Ron Ronning, the mayor of Appleton, was “very optimistic” that CCA would find new business by the summer. According to Ronning, who also worked at the prison at the time, the company was “really making an effort to get this place [Prairie Correctional Facility] filled again.”

Later that year, that effort seemed to have paid off. After spending half a million dollars in California on campaign contributions, CCA convinced the state’s officials to send their prisoners over 1,000 miles to Appleton—but the deal fell through before any prisoners were transferred. Today, the company is at it again, this time trying to incarcerate 500 of Minnesota’s prisoners currently held in county jails because the state’s public prisons are full.

By seeking people to imprison in facilities they own, private prison companies contribute to mass incarceration. Currently, CCA and GEO Group — the second largest private prison company in America — own 87 facilities across the country. When these companies, both publicly traded corporations, lose contracts at their prisons, they seek out other people to incarcerate from state corrections departments, the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), sheriffs’ offices, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). In doing so, they encourage decision makers to put people behind bars, diverting attention and resources away from making the criminal justice system more humane. Lobbying disclosure records show that CCA and GEO Group have strong presences in the offices of government officials. In 2014, CCA had 103 lobbyists working in 25 states and 25 lobbyists in Washington, D.C. GEO Group had 68 lobbyists working in 15 states and 14 lobbyists in D.C.

Once CCA or GEO Group secures a new contract, every taxpayer dollar that goes to their profit is a dollar not spent on improving conditions in jails and prisons or pursuing alternatives to incarceration. Private prison companies also pitch their services as short-term solutions to overcrowding, but too often public officials become dependent on the private space and delay addressing the root causes of incarceration.

Despite CCA’s failure so far in Minnesota, private prison companies’ efforts to find people to incarcerate often prove successful. In 2003, when Wisconsin removed all its prisoners from CCA’s facility in Sayre, Oklahoma, the company began searching for people to imprison. In 2004 Steve Owen, a spokesperson for CCA, said, “We have all along, and continue to aggressively market that [Sayre] facility. We’re doing this on a daily basis, and the goal is to definitely refill that facility.” By the end of 2006, CCA’s Sayre facility was housing 800 prisoners from Colorado, Vermont, and Wyoming.

In 2010, GEO Group purchased Cornell Companies, a prison company that owned a vacant prison in Bakersfield, California. In November 2014, GEO Group renovated the prison and announced it was “actively marketing the facility to both state and federal agencies.” Two months later, the company secured a contract with ICE to incarcerate detained immigrants at the prison. Between 2011 and 2014, GEO Group spent $460,000 lobbying on immigrant detention and other issues at the federal level.

Sending prisoners to empty facilities owned by private prison companies is a short-term solution to overcrowding, but the public bears the long-term costs. Doing so impedes meaningful criminal justice reform. In Minnesota, public officials can alleviate overcrowding either by reopening the Appleton prison, as supported by CCA, or finding ways to reduce the number of people incarcerated. They could adopt the guidelines of the state’s Sentencing Guidelines Commission and invest more resources in reducing recidivism and overhauling probation. If Minnesota reopens the Appleton prison instead of investing in these and other reforms, overcrowding will only be exacerbated.

When it comes to tackling mass incarceration, preventing private prison companies from filling their empty beds is a significant part of a broader strategy, especially in places where we should be investing in alternatives to prison. Companies that have a vested interest in incarceration are a powerful impediment to creating a just and safe society. Corrections officials and criminal justice reform advocates should start treating them as such.

Smart country, foolish choice: The U.K.’s Brextremely stupid move

(Credit: AP/Matt Dunham)

I am a professional Anglophile. When I teach modern British literature, part of my mission is evangelizing to my students the eloquence and intelligence of the writers we study in my seminars – Virginia Woolf, W. H. Auden, Philip Larkin, Harold Pinter, Iris Murdoch, Zadie Smith, Ian McEwan, Andrea Levy – and the culture that nurtured them.

Since I was an English major myself (in the 1970s), the position of British literature has shifted in the American curriculum of literary studies. I have no quarrel with this shift, which reflects important cultural and social reconfigurations. American literature, which English departments once considered not quite up to snuff compared to Shakespeare, Austen and Wordsworth, has come into its own. A burst of American diversity and innovation has made British literature seem, by comparison, a bit stuffy.

But as the literary canon has exuberantly expanded and geographically recentered, I continued to enjoy reading, writing about and teaching about British writers. I find them smart, drily funny, incisive. My period of specialization begins at 1900, which is the beginning of the end of England’s glory days. “The sun never sets on the British Empire,” the Victorians boasted. Well, the sun was beginning to set, and by mid-century it had pretty much dipped beneath the horizon. America had supplanted the U.K. as the imperial power (“superpower”). The Brits could keep custody of a quaintly archaic archive – Victorian novelists, romantic poets, Elizabethan playwrights – which we would go visit as tourists traipsing through Stratford-upon-Avon and the Lake Country, but “English” had become American in terms of its power base.

If England was a diminished power (as some whispered, a second-rate has-been) during the twentieth century, still their literature remained indefatigably engaging and admirable. They wrote with a perspective that reflected memories of the recent past when they owned the world, but combined with an awareness that such exploitative tyranny – which is what imperialism really was – was unsustainable and unethical. With thoughtful complexity and grace, their writing confronted all this, trying to figure out how to emerge from a Slough of Despond and create a vital cultural presence for the modern age. Monty Python, the Beatles, Harry Potter and Cool Britannia all helped.

What has been most interesting for me is to see how the country’s writers (and readers) have grappled with Britain’s new situation in the world. They had certainly come down in terms of power and pomp, but I always believed – and this is what sustained my resplendent Anglophilia – that their experience of de-imperialization taught them something valuable, forcing them to make lemonade out of the lemons that they got from history’s wheel of fortune.

A melancholy self-awareness – but engaging, and often empathetic – pervades contemporary British writing. Its creators see keenly what has been lost, but they also take stock (with a stiff upper lip!) of what still remains. They suffered massively throughout the twentieth century – “The war to end all wars,” as World War I was called, was ironically just a coming attraction for the next one, which taunted them with their mistaken assumption that humanity had hit bottom in 1914-1918.

British soliders and citizens fought bravely and endured with a stubborn resilience. They scrimped and rebuilt as Japan and Germany, ironically, surged ahead of them economically, making their military victory seem somewhat Pyrrhic. Through all this, the British preserved and nurtured the eloquence of their cultural heritage. More than once when I visited England, I heard high school students on buses reading Shakespeare – out loud, to each other. Good for them, I thought; they can’t take that away.

The U.K. seemed to have come to terms with the new world, and its place in that world. They had come down but they had adapted, and they determined to go with the flow of twentieth- and twenty-first century Europe, a society primed to be diverse and prosperous. Most importantly, the new Union promised to be more peaceful than Europe had been historically. The E.U. wasn’t perfect, but by and large it managed to do what it was supposed to do, keeping this dynamic but often contentious continent working together for such mutual goals as economic prosperity, military sanity and human rights.

And then comes Brexit. It is too soon for me to process this fiasco and assign blame. I am not sure how the U.K. (a Scot-less U.K., apparently) will recover from the inevitable jolts that lie ahead. I feel sorry for them when they realize that they have made a very bad decision with a great many negative consequences, and I feel sorry for the rest of Europe as well, having to deal with this short-sighted flub that threatens the continent’s long-term stability.

What motivated the 52 percent who chose to Leave? Is there some “excuse” to rebut the presumption that their votes were cast in a xenophobic spasm against immigrants, against cosmopolitan diversity, against cooperation, and against the lessons of historical reality? Were the Leavers trying to recapture some nostalgic fantasy of imperial grandeur? To “Make England Great Again?”

Uh-oh: As unfortunate as Brexit is for the British, does it also portend some comparable political dysfunctional miscalculation “across the pond” when we hold our own elections later this Fall? If so, I propose a word that acknowledges straightforwardly the choice we would be making: Americhaos.

But I am an English professor, not a political scientist, so I will go back to my books. I will find it a little harder, though, to convey to my students my enthusiasm for this eloquent, mannerly, culturally sophisticated literature. My reading will be more troubled, more problematized, as I analyze and excavate these texts trying to determine what went wrong in the U.K.’s cultural consciousness that led them to reject stability. Maybe my students and I can even find, beyond just an explanation, some hint of a path for reform: a way to understand, reconceptualize and repair the current mess. Not infrequently, we do indeed discover answers lurking in our books, between the lines, in places “where executives would never want to tamper” (as Auden described the rich imaginative world of poetry) – insights that everyone else has missed.

We will keep on reading in the hope of finding some such answers.