C.A. Hartman's Blog, page 5

June 23, 2014

Epigenetics II: X-Inactivation and Why Women are “Stripey” (and Calico Cats are Patchy)

In honor of the release of The Refugee, I explained the basics of epigenetics in a recent post. Recently, I came across a video from IFL Science entitled, “Why women are stripy.”

In honor of the release of The Refugee, I explained the basics of epigenetics in a recent post. Recently, I came across a video from IFL Science entitled, “Why women are stripy.”

Stripy?

It turns out women really ARE stripy, and epigenetics is the reason.

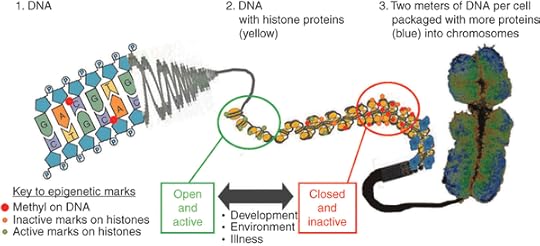

So DNA expression (i.e. gene expression) is dependent upon other factors that control if and when a gene is turned on, turned off, or regulated in its expression in some way. These other factors are what we call epigenetics, which can include how the DNA is coiled and stored in a cell (exposed genes are expressed, hidden ones are not) as well as how and where methyl groups will attach themselves onto the DNA molecule and impact expression.

Humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes, one set from Mom and one from Dad, and each is loaded with genes. The 23rd set are the sex chromosomes: XY for guys, XX for girls. It wouldn’t do for both X’s in each cell to produce gene products, as this would mess everything up. So, one X is inactivated in each cell in your body. This process is done epigenetically very early in fetal development, where the inactivated X DNA is packed very tightly and heavily methylated, telling the body to leave it alone and not let the DNA code for RNA and then proteins.

The thing is, in some cells Mom’s X gets inactivated; in others, Dad’s does. Once the cells decide who “wins,” they then begin to divide and make more cells with an X with the same origin. This creates a “striped” pattern in women’s bodies, where strips of their bodies have cells with Dad’s X and other strips have cells with Mom’s X. Of course, you can’t actually see these stripes in humans. But you CAN see them in calico cats.

Calico cats are patchy in color for the same reason, as the gene for coat color is on the X chromosome. So you get one coat color from Mom and another from Dad, and you get those patches.

Pretty cool.

June 2, 2014

What is Epigenetics?

If you ever want to get involved in something that is intricate, mysterious, and which you will never fully understand in your entire lifetime — even if you study it EVERY DAY — study genetics. The fact that a tiny, double-helical strip of molecules strung together is essentially the MAP OF LIFE boggles the mind. DNA is small enough to fit in the nucleus of a tiny cell, too small to view with the naked eye. Yet, if you unpack it from its supercoiled structure, you can actually see it without a microscope.

More importantly, the idea that your DNA has all that’s needed for a living organism to develop from a single cell to a fully-differentiated, multi-systemic creature that can survive is just… awesome. What’s even more fascinating is that there’s still SO MUCH we don’t know about DNA.

But while most people (and much of science) have focused on standard genetics and the study of DNA, there’s a whole other world to explore, one that’s turning out to be extremely important: Epigenetics.

What is Epigenetics?

With the release of my book The Refugee, it occurred to me that most people aren’t familiar with epigenetics, an important theme throughout the book (and the series). So here’s a little genetics primer:

DNA is the code that creates proteins that make things happen in our body. For example, when we approach puberty, certain genes in our DNA “turn on” and code for proteins that regulate our endocrine systems, allowing for estrogen and testosterone to increase. This is why girls develop breasts and boys get taller and deeper-voiced.

But how does this happen? Who decides what genes get turned on and off, and when? This is where epigenetics comes in.

Epigenetics examines not the DNA and genes themselves, but how the genes are turned on, turned off, or otherwise altered in their expression. In other words, epigenetics examines how genes are regulated without any change in the DNA code itself. Our genes are all there in our cells, but it’s epigenetics that decides what the genes will do. It does this by altering the way the DNA is packaged in the cell as well as with compounds that bind directly to the DNA (e.g. a methyl group can bind to DNA, a process known as methylation).

Photo courtesy of Nature article by Sun et al, Pediatric Research (2013) 73, 523–530

Epigenetics has gained more attention in the last several years. For ages, it was assumed that “code is key,” i.e. that your DNA code determined important aspects of your biology, including your health, your appearance, and the aging process. Now we know that epigenetics plays a big role in these areas. Some examples:

Identical twins, with identical DNA, can turn out differently. One can develop Alzheimer’s while the other does not, or they can look slightly different.

All cells in our body have the same DNA, but epigenetic mechanisms tell a cell whether to become a skin, liver, or pancreatic cell.

An epigenetic change can “turn off” a tumor suppression gene, which can lead to uncontrolled cellular growth (i.e. tumor).

In Fragile X, a genetic disorder that leads to intellectual/developmental disability, one only gets the full disorder if the DNA is methylated, which “turns off” the gene that creates an important and necessary protein. It’s this addition of the methyl group that’s the issue, not the abnormality in the code itself. I actually worked on a Fragile X project many years ago.

Even the aging process itself is considered by some to be an epigenetic process. After all, something tells our cells to stop producing melanin in our hair, for example, resulting in gray hair.

What’s really amazing is that epigenetic states can be passed on to one’s offspring. But that’s a whole other topic.

Here are a few articles on epigenetics, if you’re interested:

LiveScience: Epigenetics: Definition and Examples

May 19, 2014

Different Kinds of Science Fiction

Anyone who’s every read science fiction knows that it can vary considerably. I don’t just mean in terms of quality… I’m talking about the plot, characters, world-building, tone, and ideas.

Anyone who’s every read science fiction knows that it can vary considerably. I don’t just mean in terms of quality… I’m talking about the plot, characters, world-building, tone, and ideas.

For example, look at Isaac Asimov’s Foundation, which had grand ideas about an empire of galactic proportions and a man’s ability to predict its fall and rebuild. Big ideas, but little to no character development and world-building.

Then, look at Frank Herbert’s Dune, which created a fascinating world of different peoples and their lust for power. In addition to its nod to ecology and conservation, it had religious themes and a bit of fantasy. By the way, I love this older cover for the book.

And what about Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, a disturbing dystopian novel about the kind of world where firefighters burn books rather than fight fires and information is considered dangerous: memorable characters, thought-provoking ideas, but simple plot.

There’s also the novels and series of S.L. Viehl, space opera that makes for a fun read but is light on ideas or heavy science.

I could go on and on. Some have attempted to classify science fiction novels into sub-genres. This article on Amazon, entitled “So you’d like to… Explore the Different Types of Science Fiction does a decent job of it and includes well-known examples of each sub-genre. Here are the types, from the article:

Types of Science Fiction

Alternative histories

Cyberpunk

Hard science fiction

Humorous science fiction

Military science fiction

Sociological science fiction

Space opera

Science fantasy

Time travel

Utopias and dystopias

May 17, 2014

“The Refugee” is finally available on Amazon!

After years of toiling and perfecting, my science fiction novel, The Refugee, is finally available for sale. It’s the first in the Korvali Chronicles series.

After years of toiling and perfecting, my science fiction novel, The Refugee, is finally available for sale. It’s the first in the Korvali Chronicles series.

The story has elements of genetics, military, and space opera. I’m told it isn’t similar to any other science fiction writer’s style… but a couple of beta readers did compare it to the work of C.J. Cherryh. I’ve also had women who don’t love sci-fi read chapters from it and tell me they really liked it.

Here’s the synopsis from the back cover:

The Starship Cornelia, barely a few months into a 3-year mission to visit the other inhabited Alliance planets, unexpectedly stumbles upon a disabled ship whose 10 alien passengers are found dead. The ship hails from Korvalis—the mysterious non-Alliance planet whose leadership allows no outsider to visit and no citizen to leave. But the tides shift when Cornelia’s Chief Medical Officer and lead geneticist discover that one of the escapees is alive, having survived only due to his superior skill with genetics… and that he seeks asylum from Korvalis.

The Refugee—the first of the Korvali Chronicles series—tells the story of Eshel, the Korvali refugee, and Dr. Catherine Finnegan, the human geneticist who befriends him, as they face the political, scientific, and interpersonal ramifications of Eshel’s living among humans. From censoring of their scientific work to intolerance for Eshel’s cold arrogance, struggles abound… until an alarming incident changes everything.

Here is the link to the print and Kindle version on Amazon. Enjoy!

May 11, 2014

Why “The Counselor” was a Worthwhile Film

When I first saw the trailer for The Counselor, I was interested. Months passed. When I came across this Word & Film article, I realized I’d missed the film’s release entirely. And after reading the article, I found out why: it didn’t do well in the theaters and critics skewered it.

When I first saw the trailer for The Counselor, I was interested. Months passed. When I came across this Word & Film article, I realized I’d missed the film’s release entirely. And after reading the article, I found out why: it didn’t do well in the theaters and critics skewered it.

The Counselor’s screenplay was written by famed novelist Cormac McCarthy and directed by Ridley Scott. Many question whether a novelist can write a good screenplay, as novels and screenplays vastly differ in terms of structure, format, and goal. Some say novelists can’t let go of control over their story and are unable (or unwilling) to accept the changes that are necessary to turn a novel into a film. Others say moviemakers dislike when the screenwriter shows up on set because they know he/she shares a close bond with the script as written and may not like it when the actors or director don’t reflect his/her dialogue or vision. Overall, McCarthy’s script was one of the major criticisms of the film.

I ordered it on Netflix immediately. And while it had a few flaws, I thought it was, overall, an extremely interesting and well-made film. Here’s why:

It Deviated From the Expected Story

How many movies about drug dealing have we all seen? And how bored are we of the same old story: some greenhorn gets into the drug business to make money, he struggles at first but then tastes success, he lives the high life with girls and cars and clothes, and then it all begins to fall apart as he becomes excessive, addictive, and more careless while the kingpin/cops/Feds inch their way closer. This film took a different approach, much like Soderbergh’s Traffic did when it looked at the drug trade from multiple angles. It focused, rather darkly, on the negative consequences of the protagonist’s choice to involve himself in a dirty business.

It Didn’t Have the Usual Gender Roles

Every drug movie I can think of showcases men in the lead roles. They have all the power, and the women are little more than pretty trophies who benefit from their drug man’s income and pretend they don’t know what’s going on. In The Counselor, Penelope Cruz’s character is actually naive, having no idea of her fiance’s shady dealings… she is a true innocent and a woman her fiance is head over heels for.

On the other end of the spectrum, we have Cameron Diaz’s character Malkina, a formidable woman who turns out to be the real kingpin. Add her pet cheetahs to the mix, and a special performance on a windshield — along with Cruz’s fiance going down on her in the opening scene — and the film gives the phrase “pussy power” a whole new meaning.

Subtext on Top of Subtext

They say subtext separates the veteran screenwriters from the newbs. In most movies, the subtext feels like it’s heaped on with a shovel and so obvious that even a child could get it. Elysium comes to mind, which I’ll discuss in another article sometime. But The Counselor had layers of subtext that took a second screening for me to really appreciate. This is something I imagine a novelist can master with much more ease than can a screenwriter.

For example: In one of the opening scenes, Malkina sends out her cheetahs to hunt down a jackrabbit. They succeed. Malkina has cheetah spots tattooed on her and lined eyes that make her look obviously feline. Supposedly “Malkina” refers to some kind of cat. A cat can symbolize feminine power or treachery. She’s the hunter; the others, including her partner, are the prey. And most of what happens in the film is foreshadowed in this early scene.

Much of the movie is spent in 1-on-1 dialogue that either foreshadows or parallels the protagonist’s increasingly dim situation. It’s heady stuff… see the next section…

Interesting dialogue

This is the kind of dialogue you don’t often see in films. Or if you do, it’s so damned self-conscious that it’s embarrassing to watch. The dialogue was one of the main criticisms of the film. Perhaps too much subtext and philosophizing, and not enough simple English and tough guy aphorisms. I didn’t always like the dialogue, but I liked that it was different.

Was the film perfect? No. But I think, like Lisa Rosman does, that this film will eventually be appreciated.

March 1, 2014

Pre-Oscar Film Analysis: Was 2013 Really “All That”?

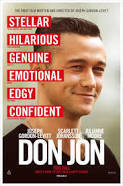

According to many, 2013 was a big year for movies, comparable to other “big years,” such as 1939 (Gone With The Wind, Wizard of Oz, etc). There were many good blockbuster films (Gravity, Man of Steel), indie films (Don Jon, Side Effects), and Oscar fodder films (12 Years a Slave, Blue Jasmine) that succeeded with critics and audiences.

According to many, 2013 was a big year for movies, comparable to other “big years,” such as 1939 (Gone With The Wind, Wizard of Oz, etc). There were many good blockbuster films (Gravity, Man of Steel), indie films (Don Jon, Side Effects), and Oscar fodder films (12 Years a Slave, Blue Jasmine) that succeeded with critics and audiences.

However, The LA Times doesn’t agree, suggesting that the big winners such as Gravity and American Hustle are due more to “grade inflation” resulting from economic concerns and the impact a critic’s pan will have on an industry in flux… and on the critic himself, who may have to contend with backlash and marginalization in social media. Apparently, raves circulate far better than pans do. In other words, reviewing film is a different animal today. I don’t know if I agree with McNulty, but I can see his point about how things have changed and that these changes could impact film criticism.

It’s difficult to weigh a batch of movies, each with greatly varying quality, against another batch of movies (each with greatly varying quality) seen a year ago. You’re only going to notice a difference if there’s a pretty striking effect (i.e. a very good or very bad year compared to previous years). To some extent, you have to treat each batch independently and assume that, when you average all of them together, they’ll generate roughly the same mean score as a previous year would. True, the variance will differ greatly from year to year, as you could have a solid number of decent ones one year, followed by another year with several stellar films along with numerous disappointments.

For myself, I liked 2013. I went to the movies more than I usually do. But this is mostly due its appealing to my own film tastes. I happen to like blockbusters if they’re done well. I don’t go out of my way to see indie films unless they appeal to my personal interests, and some did this year: I thought Don Jon was an interesting film examining the unrealistic expectations people have when entering into relationships, and that Inside Llewin Davis was one of the best films of the year with its great story and direction.

But, most of all, 2013 was a good year for science fiction, the most important of genres as far as I’m concerned. Especially when it’s well done, which it often isn’t. Gravity and Her are Oscar nominees. I loved the second Hunger Games film. Ender’s Game and Man of Steel were decent. Star Trek Into Darkness disappointed — but I knew it would. The JJ Abrams Star Trek movies bear no resemblance to the spirit of the franchise. But their popularity should inspire others to do better, and that’s a good thing.

See you Sunday night at the Oscars…

February 24, 2014

Pre-Oscar Chat: Will Alfonso Cuaron Win Best Director for Gravity?

With the Oscars looming just a few days away, we’re starting to see more and more predictions of who’s going to win. The critics at RogerEbert.com came together and offered up their predictions. To wit:

Best Supporting Actress: Lupita Nyong’o, “12 Years a Slave“—Essay by Glenn Kenny

Best Supporting Actor: Barkhad Abdi, “Captain Phillips“—Essay by Omer M. Mozaffar

Best Original Screenplay: “Her” written by Spike Jonze—Essay by Nell Minow

Best Adapted Screenplay: “Before Midnight” written by Julie Delpy, Ethan Hawke and Richard Linklater—Essay by Brian Tallerico

Best Director: Alfonso Cuaron, “Gravity“—Essay by Peter Sobczynski

Best Documentary: “The Act of Killing“—Essay by Olivia Collette

Best Actress: Cate Blanchett, “Blue Jasmine“—Essay by Susan Wloszczyna

Best Actor: Chiwetel Ejiofor, “12 Years a Slave”—Essay by Odie Henderson

Best Picture: “12 Years a Slave”—Essay by Matt Zoller Seitz

I can get on board with this list. Cuaron for Best Director is an interesting choice, given that the movie got mixed reviews from critics. Everyone loved the visuals, but others displayed considerable disagreement over the screenplay, the plot, and the acting. Yet, from a directorial standpoint, it could, and perhaps should, win. The “visual” aspect of Gravity isn’t just about special effects; it’s not Avatar, reliant only upon special effects (even if extremely innovative ones) to impress people. Gravity’s visual appeal required a lot of directorial decisions that made it unique.

Most obvious was the opening scene, a nearly 20-minute single shot of the characters attempting to make repairs to a satellite while floating in space. Such long shots are no easy feat, as if anything goes wrong — anything at all, even a lightbulb going out — the entire scene must be shot all over again. They’re high pressure and anxiety-provoking for everyone involved in shooting the scene, as no one wants to be the screw up that ruins the shot and makes them have to start again, especially when you have a very limited amount of time in which to get the shot. And when you have numerous things happening, such as people floating around to choreographed moves in “space,” more can go wrong.

Cuaron showed a similar propensity for long shots in Children of Men, a nervewrackingly fantastic film about a dystopian world where the human race has ceased to be fertile and will extinguish entirely in 60-80 years. In the film, the protagonists fight to save a pregnant girl and get her to somewhere safe, away from war, racism, and hopelessness. There is one very long (~20 min) single take scene in which the main characters are in a car, trying to escape their enemies, in which the camera pans around and films everyone in the car as well as all the action going on outside the car. One reviewer called Cuaron’s single takes “boastful” — I say that in a world with lots of cuts and shaky cams that try to make fight scenes look better than they are (yes, I’m talking to you, Bourne), the single take, especially in an action movie, is worth boasting about.

I didn’t find Gravity’s story to be a problem. Was it groundbreaking? No. But it didn’t need to be. The film made us believe we were watching these people in space, even adhering pretty closely to the laws of physics (unlike many sci-fi films). It made us feel the palpable isolation and loneliness of the main character, and offered us something unexpected, unique, and stunning.

February 8, 2014

Don Jon: A Film about Porn… or Relationships?

Don Jon was one of those movies that I thought might be interesting, but I had no strong desire to see it. This was mostly due to the fact that I only saw a trailer for it perhaps once, and it was brief and lightweight, not really giving us a peak into the movie’s real theme. I’ve noticed that many trailers seem to do that these days; instead of showing us key parts (or, in some cases, the entire plot) in the trailer, it shows us very little, as if hoping to surprise us. Her comes to mind. And Silver Linings Playbook. But I suppose good movies don’t need to show us too much in the trailer; word of mouth will do its job.

Don Jon was one of those movies that I thought might be interesting, but I had no strong desire to see it. This was mostly due to the fact that I only saw a trailer for it perhaps once, and it was brief and lightweight, not really giving us a peak into the movie’s real theme. I’ve noticed that many trailers seem to do that these days; instead of showing us key parts (or, in some cases, the entire plot) in the trailer, it shows us very little, as if hoping to surprise us. Her comes to mind. And Silver Linings Playbook. But I suppose good movies don’t need to show us too much in the trailer; word of mouth will do its job.

Synopsis

Don Jon is about Jon, a 20-something bartender in New Jersey (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) who spends his free time hitting on girls in clubs and attempting to sleep with “dimes” (Tens). In many cases he succeeds, as he’s nice looking, very fit due to his Gym Rat status, and confident to the point of hubris. Jon develops an interest in Barbara (Scarlett Johansson), a Dime he meets at the club who won’t sleep with him that night… or any night for the next month or so as he gets pulled into doing “long game” with her. Things go well until Barbara discovers Jon watches porn. Not only does he watch it, it’s a daily habit for him, something that offers him what he needs: the ability to “lose himself” (his words). Real-life sex just doesn’t measure up. It’s when he meets Esther (Julianne Moore), a weed-smoking, free-spirited older woman, that things take an unusual turn.

Porn and Sexual Addiction

Don Jon is a porn addict. He says he can “stop anytime he wants” (the mantra of all addicts), but when he tries, he finds he can’t. He can’t even masturbate with his eyes closed. Many people compare this movie to Shame, a film about a man’s struggle with sexual addiction, but the two movies have very little in common. Shame is about the pain and darkness of sexual addiction and the joylessness of addictive sex. Don Jon, on the other hand, isn’t dark and isn’t really about addiction. It’s not even about sex. The one thing both films have in common: the leading man’s inability to really connect with others in a healthy way.

Don Jon is about relationships and what it is to connect to another human being. Sex is a unique opportunity to do that, but we live in a culture that struggles with this, that on the one hand looks down on sex for fun’s sake, and on the other supports an extremely profitable porn industry.

The Power of Imagery… and Fantasy

Humans are visual creatures. We love imagery, and film offers such powerful imagery at times that it can impact how we think about certain issues, including our expectations about relationships. For Don Jon, porn imagery skewed his expectations about women and relating to them. For Barbara, the imagery of romantic films fueled her unrealistic expectations about perfect love. Barbara wasn’t enough for Jon; he needed the porn. And Jon wasn’t enough for Barbara either; she expected him to get a more impressive career, to hire someone to clean his home rather than do it himself. She also expected him avoid porn, but not for the right reasons. Their relationship hit a crisis when their shallow, unrealistic fantasies and expectations collided with one another. Porn and romance movies aside, isn’t this what many people do?

In some ways, the film explores male/female differences in an obvious way–we’ve all heard the “men like porn, women like romance” thing until it’s become BORING. But, as Don Jon shows in its unique way, men and women seek the same thing, only in different ways.

Don Jon isn’t about porn and whether it’s okay or not okay. It’s about the things that get in the way of really connecting with someone we’re involved with. Those things can include porn or unrealistic romantic expectations, but they can also include focusing too much on how hot someone is, how much money they make, or whether that person fits the mental image you have for the ideal partner. This is what many people do until they learn–often the hard way–that such things won’t make them happy.

Jon didn’t just kick porn; he learned to connect with a woman. He went from chasing the Dime he thought he wanted but with whom he felt no real connection, to forming an unexpected connection with Esther, an older woman who didn’t even come close to his usual type. He found that the sex (and the relationship) was emotionally satisfying as well as physically, which is what he’d wanted all along.

Some didn’t quite get Gordon-Levitt’s choice to take the film in this direction, but I do. Esther, with her grief, her almost-inappropriate honesty, and her hippie-ish laidback-ness represented the emotional piece Jon was missing and the the opportunity to try it on without expectations. Turns out it fit.

January 20, 2014

“Her” — Love Story, or Science Fiction?

Saw Her the other night. Before seeing it, I admit I felt a bit like I did last year when everyone raved about Silver Linings Playbook; my thought was, the premise doesn’t sound exciting and it doesn’t look especially interesting in the previews… how good can it be? It was good. Better than I’d expected. And when I saw Her, I had the same reaction, but even more so.

Her is a story about Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix), a guy recovering from a divorce and very close to — albeit resistant to — signing his divorce papers with Catherine (Rooney Mara). He’s lonely and not especially satisfied with the online (or audio) options for “companionship” available to him in his technologically advanced world. And, based on one of these interactions, my guess is that Spike Jonze isn’t much of a cat person :). Anyway, Theodore, a romantic who writes heartfelt love letters for other people for a living, tries a new operating system (OS) that’s designed to have a more personal, intuitive quality. This OS becomes his friend, and then more.

Science Fiction Features

When I watched this film, I felt, at times, like I was watching science fiction rather than just a love story or a film about relationships. Later, when I read a few reviews, many made this same observation. In many ways, it is science fiction. It’s speculative in nature, taking place in an imaginable near future where humans rely more and more upon technology and less upon people, who are, in many ways, less reliable than technology. It uses a love story between a human and an operating system as an allegory for relationships, love, and connection among humans.

Like Inception (but in a different way), Her takes science fiction away from the classic “hard” science and tech tropes and into the muddier world of psychology. In this case, we explore aspects of what it is to connect to another human being, what it is to love, what it is to collide with another person’s needs, limitations, and programming. Humans also have software, programmed from years of experiences and the (often unconscious) decisions we make about those experiences. And that programming can cause us all sorts of relationship misunderstandings, as it did for Theo and Catherine, and even for his friends Amy and Charles, whose relationship suffers from its own strain.

Early on, I assumed the film would take on the usual man versus machine theme, where falling for an OS is a way to avoid real connection with a human by taking the easy way out. I was reminded of the episode of Star Trek TNG where a female member of the Enterprise crew gets romantically involved with Data after suffering a loss. She finds his lack of emotion attractive and a source of comfort at first; eventually, she feels empty without the emotional connection necessary to make a relationship work. Yes, Her does explore these themes. After all, this is a world where Theo makes a good living writing moving love letters for others. Some of his clients have used his services for many years, apparently because he values (and seeks) the romantic sentimentality they’re too lazy to find in themselves. Yet, the film takes us into unexpected places, forcing us to consider that all connection his its complications and limits.

Other sci-fi features include the futuristic OS system Theo falls for, including its sentience, its evolution, and what happens at the end; this certainly brings up interesting ideas about artificial intelligence and its possible future role in our society. Los Angeles looks interestingly futuristic, with its expanse of modern high rises and its trains (Trains! In L.A.!). I even spotted a rooftop forest on one of these high rises, with multiple large trees. Apparently the city was a mix of LA, Shanghai, and CGI.

Visual Symbology

Her had some unique visuals aspects which, for me, take a movie to a higher level. The office Theo worked in had lots of colored plexiglass and a generally mid-century feel. The costumes had the same effect, where Theo reminded one of Cary Grant with his neat button-downs and high-waisted, narrow-legged woolen trousers. My mom, who was raised in mid-century L.A. by an architect father who loved modern design, hated the overly modern, plastic, non-organic feel of mid-mod. She still does. So, to some extent, the design in the film, while very cool, could represent the somewhat impersonal feel of the world Theo inhabited.

His office also had black-on-white wall illustrations of people that the camera would linger on — a girl reading, a man curled in a ball, a man getting ready to open an umbrella. Much like some directors use songs to emotionally connect us to a scene, Jonze used these images. For example, the umbrella image came just before Theo had to face a “storm” of his own.

Overall, a very good film with a great screenplay that explores what it is to connect to other humans in the Information Age.

January 12, 2014

Film Analysis: “Inception” and the Language of Dreams

Many of you know I love the movie Inception. I love it so much that I believe it has edged out Blade Runner for the #1 spot on my fave science fiction movie list. I love Blade Runner, but the final act with Roy gets a little tedious for me.

Many of you know I love the movie Inception. I love it so much that I believe it has edged out Blade Runner for the #1 spot on my fave science fiction movie list. I love Blade Runner, but the final act with Roy gets a little tedious for me.

Inception’s brilliance is its complexity. It took Christopher Nolan 10 years to write that screenplay, and many will admit that they still glean a little more from it with each viewing. Science fiction is the place for ideas, and this idea is a fascinating one. Plus, most sci-fi sticks to the so-called “hard” sciences, afraid to tackle the more fluid, complex world of psychology. Inception not only tackles psychology, but delves into an even more mysterious realm of psychology: dreams.

Film synopsis

The film is about invading others’ dreams to steal their ideas. Powerful people undergo extensive training to prevent such theft, and Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio’s character) and his band of helpers are trained for this. Inception, on the other hand, is actually implanting an idea in someone’s mind, so deep into their unconscious that they think it’s their own idea. Cobb and his colleagues are hired to hack into a billionaire’s son’s mind to convince him to split up his dying father’s monopolistic business empire, thus making room for others to compete in their trade. To do this, they must get him to sleep and create a dream, within a dream, within a dream, to implant the idea.

As with all big plans, things go awry. For one, Cobb has issues. There’s a reason he’s so skilled at this. [Spoiler Alert]. He once did this to himself and his wife, with disastrous consequences.

Dream Analysis

During the film, much time is spent in people’s dreams. Although the sets were made to look great and add to the film’s visual appeal, certain things were intended as powerful symbols of the story.

Much of the information I’ve learned about dream symbols comes from what is, to my knowledge, the best dream website there is. It’s called Dream Moods, and it has a great Dream Dictionary with every dream symbol you can imagine.

The beach: At the beginning (and end) of the film, Cobb comes to on the beach. A beach can mean a few different things, but here he refers to it as “the shore of his unconscious,” suggesting it is the starting point at which one can only go deeper. It is also the meeting place between the rational (earth) and the emotional (water) of the mind.

Angry mobs and explosions: Early on, they’re in Saito’s dream (which is actually Nash’s dream), attempting to steal Saito’s ideas. Saito is powerful and his mind has been trained to deal with such thefts. In his dream, you see an angry mob and lots of noisy explosions, both of which symbolize repressed anger. In this case, Saito’s mind is angrily defending itself against the invasion. Also, in this dream, the safe is a pretty straightforward symbol of Saito’s hidden secrets.

The elevator in Cobb’s dream: When Ariadne visits Cobb’s dream, she takes an elevator and sees aspects of his unconscious. The top level is at the beach. She then descends, suggesting she is delving deeper into his subconscious, and she finally goes to level B (for basement), which represents the most primal area of the unconscious. Here, she comes across the scene from the night Mal died, and an enraged, terrifying Mal. Death, terror, rage… all primal things. Interestingly, it’s one of those old elevators where you pull the barred door shut, showing us that Cobb’s dream memories are really more like a prison for him.

The spinning top: Mal’s (and eventually Cobb’s) reality test was a spinning top — if it stayed spinning, they were still under. This could be an interesting symbol of the the wasted time and “spinning in circles” that occurred during the massive number of years Mal and Cobb were trapped in their dream state, and the thing that made Cobb want out.

Cities: A lot of this movie takes place in cities, particularly big, sterile cities (e.g. the first level of the inception sequence with Robert Fisher, Cobb’s fake world where he spent decades with Mal…). They represent the isolation Cobb and Mal experienced during their extended dream state and the isolation Cobb experiences every day due to his losing Mal, not seeing his kids, and spending much of his time living in the past (via his dreams). Contrast the coldness of Cobb/Mal’s dreamworld with their real home, which is homey, warm, and comfortable.

Mal: Throughout the movie, Mal is a consistent troublemaker, interfering with Cobb’s dream work. But it isn’t Mal that’s the problem. Mal’s dead. It’s his memory of Mal (and what happened), buried deep in his unconscious mind, that’s the problem. She’s angry and even murderous, symbolizing his own suppressed rage at what happened and his own deeply-seated torn feelings about it that he refuses to deal with.

Psychology

To perform inception, you need an idea “so simple that it will grow naturally in the subject’s mind,” Eames suggests. He recommends getting away from the original idea of monopolies and other business- or political-oriented ideas and getting more fundamental: the billionaire’s difficult relationship with his father. This gets away from the intellectual and deeper into the emotional, where it can be planted into the subconscious and allowed to grow. Why does this concept work? Humans, for all their big brains and intellectual capabilities, are emotional creatures at their cores. The unconscious is a place of emotion, and dreams are the realm of the unconscious.

Science fiction is filled with father issues: Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader, Jean Luc Picard and his father (Star Trek TNG), Lt. Tom Paris and his Admiral dad (Star Trek Voyager). No one has more influence on a man than his father, even if he was never around.

The inceptioneers exploit this father-son relationship to implant the idea for young Robert to split up his father’s monopoly — not because it’s the “right” thing to do or as an act of rebellion to his dad, but because it will offer him some type of resolution and catharsis for him. They decide, very astutely, that motivation to do good always trumps the motivation to punish.

In the end, Robert splits up his father’s company — not to rebel, but because he is shown, through the dream, at the deepest dream level, that his father does love him and and wants him to be a better man than him. What’s more cathartic than that?

And Cobb finally gets his own resolution and catharsis when he confronts Mal in his dream, releasing her (and thus his own grief) from the “prison” they were both in.

C.A. Hartman's Blog

- C.A. Hartman's profile

- 26 followers