Nina MacLaughlin's Blog, page 10

March 2, 2018

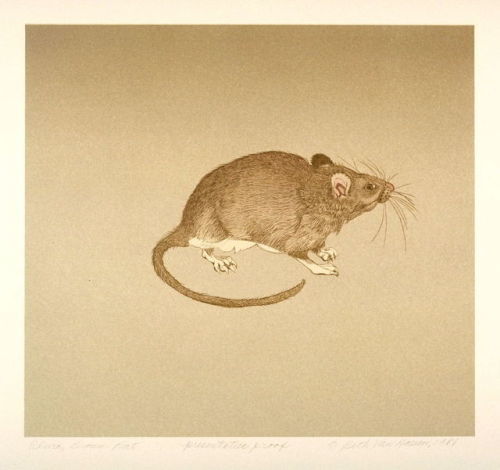

There were mice in the place I used to live. They ate the

poison...

There were mice in the place I used to live. They ate the

poison in the basement and did weird things like walk on their toes into the

walls before they died in the filth below the fridge. Sometimes they didn’t eat

the poison and wandered around the stove. I was alone during a stretch of one

summer when many of them had made themselves comfortable wandering around the

kitchen in the evenings. I set out a trap, one of the old fashioned

neck-snapping traps. I made my way towards bed, shutting the small apartment

down for the night, and a loud snapping rattle came from the kitchen. I walked in to look

and then I walked out because whatever creature had been caught was twitching

still and much larger than a mouse. I waited in the dark of the living room

until the twitching might’ve stopped. When I walked in again, my brain could

not make sense of what I was seeing. Was this a massive mouse? Was this, please

no, a rat? I got closer. Was this a

mouse with two fucking faces? Was this a mouse with two heads and eight legs? A

conjoined Siamese twin mouse mutant? No, it wasn’t that. It was two mice. It

was two mice killed together in the neck-snapping trap. They’re brothers, I

thought. They’re small brothers who didn’t know and just wanted to eat the

marshmallow together. One was round. One was lean. They both looked soft. Their

eyes were open. I sat down on the kitchen floor and leaned against the cabinets

and cried. I didn’t want to be the only one to see. Meg Freitag in a poem

writes of two scorpions in her kitchen:

So, this was loneliness:

Two scorpions fucking each other to death in a glue trap

And no one to share it with.

[Olivia by Beth Van Hoesen, 1979]

January 30, 2018

On the bank across the river, a few guys

fished. They spread...

On the bank across the river, a few guys

fished. They spread themselves across the small eyelid of sand and spoke to

each other now and then. The sun hit the river through the trees and the day

was warm and the shade felt good under the bridge where we sat watching the men

fish, listening to them talk – their voices traveled the underside of the

bridge to us, reached us at an echoey full volume. They didn’t say much, but we

heard each word when they did. When they laughed it sounded like giants

laughing. We spoke quietly. But we didn’t say much either. Instead we watched

water move, watched light move on water, kept an eye out for box turtles,

minnows, dragonflies, water striders skimming on the surface.

It seemed unlikely that these men would catch

anything, and maybe they weren’t that serious about it anyway because there

were no buckets or coolers or anything on the shore across the river that

would’ve taken a fish home if caught. They didn’t look at each other when they

talked; their eyes followed their lines into the water. Saturday afternoon,

summer’s end, the lines tossed, sunk, reeled, and tossed again. Perhaps it is

the sport most deeply linked with hope. Maybe this time. Maybe this time. Maybe

this time. The tug, the bite, the vibration up the line that jolts the heart

and says, got something.

The biggest of the three tossed his backpack

on his back and moved off the bank toward a path up into the woods. He told the

guys good luck, enjoy it. I held a pebble in my palm, considered tossing it

into the river, wanted to, but feared

it would scare the fish and annoy the men on the other shore. I held it,

watched minnows flicker close to land then head upstream into shadow. And then

the man who’d just walked up the path arrived on our side of shore. He was

barefoot, dark haired, twenty years old maybe, a thick guy with a soft face and

a smell that maybe he’d been wearing the same shirt for a few days in the

summer heat, had maybe been barefoot for a few days, too.

“I come over here to look for roaches,” he

said, lowering himself to a spot on the bank. “I can usually get a joint’s

worth on Saturday mornings. The kids come on Friday nights and I come the next

day. Yep. Here’s one. Here’s one. Sundays are good too, but Saturdays are

better.”

“Did you catch anything?”

He pulled himself back up to where we were

sitting.

“Want to see?”

He unzipped his backpack, just a regular

backpack like any kid going to school, and reached in and pulled out a massive

river carp, eighteen inches long and thick as a football. He gripped its thick,

slick body in his hand and it thrashed once. A full body jerk. I leapt back, startled

at seeing so much life.

“It’s okay,” he said. “They do that.”

He kept hold of the fish as its gills moved,

revealing a blood-red interior, the vents opening and closing without rush or

panic, vital remnant of our bodies’ most basic urge. Keep going.

“My dad has a recipe, mostly it’s spices. I’ll

gut it and cut it up and get the spices all over it and put it in a pan. No

problem.” He looked at the fish as he spoke. We all looked at the fish. We said

it was an amazing fish. A beautiful big fish. He put it back into his backpack,

straight in. No bucket, no plastic bag, just a big fish in a backpack and he

would feel it thrash against his back on his walk home.

[Muskellunge (+ Mosquito; 2 works from Under the North Star), 1980, Leonard Baskin]

January 27, 2018

It’s been a while. I sat on a stool in the basement with the...

It’s been a while.

I sat on a stool in the basement with the slab

on my lap. I sanded it and sanded it — 80 grit, 150, 220, 300, 400, 600, a torn off

corner of a soft old T-shirt — and watched things emerge on the wood: swirls, rings, echoes,

spins, pulses, waves. Inside, deep enough, there’s a layer like outer space, a

density of swirl, and I sat on the stool in happy disbelief of it.

The wood tells you when it’s smooth enough. You

feel it with your hand, of course. I moved the flat of my hand over and over

it. Goddammit, I said outloud in the basement dim, amazed at how smooth it was,

the same way I sometimes swear about an especially delicious bite of food. Against

the hand, a feel that seems impossible from what was once rough and splintery

wood, like satin, like skin. The power of the transformation after such a

simple combination: friction, time.

The wood tells your hand when it’s smooth

enough. And the wood tells your eyes. Something happens at a certain layer and a

light begins to reveal itself — the wood seems lit from within. That’s when

you know it’s smooth enough. I felt the smooth and saw the light and the light

is a mystery.

The table was a gift for someone who’d

mentioned once offhand admiring madrone, wood that comes from the other side of

the country. I found a small slab online, did the work to it, and when I

presented it, a tiny table made from this wood, I knew from the face of the

recipient that it wasn’t the wood,

but the tree itself that was loved, the rich colors of its peeling bark, its

twisting, gnarled form. It was as though someone were to say, I like brown dogs and you were to find a

brown dog and murder it and skin it and wire its form the way you wanted it and

presented it to the person and instead of delighted, they would feel horrified and

sad.

But I

love the way the table looks. And it was good to see that light again. It had

been a while and I’d almost forgotten.

January 23, 2018

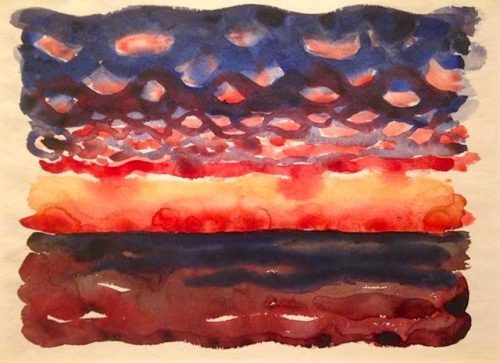

The scarlet ibis stood about twelve inches high, a

round-backed...

The scarlet ibis stood about twelve inches high, a

round-backed bird with a long black beak and feathers a deep and dusky red. As

if a splash of grapefruit juice was added to the glass of cranberry. The ibis

stood behind a glass case in a museum in Salem, Massachusetts in a room with a

whale jaw hanging from the ceiling, and an interactive wind display – move

the small steering wheel, see the way the movement of air shifts the fine white

sand. The height of the wheel prescribed the intended age of its interactors. A

toddler, three feet high, in checkered over-alls and a knit hat with ear flaps,

twisted the wheel this way, that, back forth, and the fan inside flung the sand

into rippled dunes. The toddler’s father crouched behind him and spoke quietly

in the small boy’s ear. “See it move?” he said. “You’re doing that.”

Nearby, the ibis stood with other birds. A snowy egret, a kingfisher,

lots of finches and warblers, all perched on pins against the wall. They were

stuffed and wired, but the mind didn’t have to work hard to imagine them in

movement, in darty flight or beaking dirt for bugs. A flesh-and-bloodness

remained, a sense of muscle twitch, neck about to stretch, wing about to spread.

Brown polka dots, green flares, a blaze of red on wingtip, a glimmery band of

purple. The staggering variety of life on earth.

Other rooms held famous paintings. The dresses Georgia

O’Keefe wore on her body were on display (there was no muscle movement to be

detected there; they hung flat, shed, dead). A digital exhibit explored four

dimensionality. In a dark space walled by translucent screens, letters were projected

falling and spinning. The effect was like falling through an outer space where stars

were made of alphabet. Chaos, infinity, potential.

The sense of limitlessness neared frightening. The birds

provided a more comprehensible sense of time and place and raised questions

there were answers to. How does the scarlet ibis get that color? Does it absorb

the sunsets? No. It eats prawns. It gulps shrimp and the pigment tints the

feathers. O’Keefe’s paintings are saturated with sunsets, sands, skulls, skies,

petals spreading. Her dresses were black and white. She hasn’t filled them,

hasn’t swished the skirts with her legs, in over thirty years. Who knows when

that ibis swallowed its last shrimp.

All our words and work – our search for food, our

migratory action, our entries, exits, our gathering with others in our

quotidian efforts to keep going, the messages we send to try to make ourselves

understood (I want you, I love you, I’m hungry, I’m scared) – will

be pulverized by time. Our letters and the bones that held us up, stardust. We

try to makesense in the meantime, nagged by a feeling of a promise unkept, something

on offer from the start we’ll never be able to find. We end empty handed,

trying to steer the wind.

[Georgia O’Keefe, Sunrise and Little Clouds No. II (1916)]

November 16, 2017

An experiment in 2005 asked forty-eight university students to...

An experiment in 2005 asked forty-eight university students to look at

images of wild nature as well as images of ‘managed nature.’ Prior to

looking at the images, the researchers reminded the members of one group

that someday they would die.

The third installment of my five-part series on November, this time on color and fear and the stages of alchemy, is up on the Paris Review.

Have a look at the whole series here.

[The Return of the Herd, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1565]

November 13, 2017

“November holds the in-between. Between warmth and cold, between...

“November holds the in-between. Between warmth and cold, between light

and dark, between living and dying. The eleventh month, getting darker,

getting colder, echoes our own eventual winding down and gives chance to

live in the richest, deepest way.”

For these extended evenings, on darkness and quiet and the Japanese concept of ma. The second installment of my Novemberance column for the Paris Review.

November 6, 2017

“It’s November now and there’s something different afoot. In...

“It’s November now and there’s something different afoot. In November,

when the nights get long and the days get cold, as we approach the long

dark that is winter, we feel that hand following us down the hall. We

feel death’s presence and are therefore more alert to our own. November

makes us know, at the edges of our mind, that for each of us, looming

winter will one day stretch into eternal darkness. So we welcome the

dead among us, remember them, invite them back, and we eat and drink and

let the boundaries dissolve, and we are more certain that we’re alive.

That’s what’s on offer in November. It makes us know, at the edges of

our mind, that we still cast shadows, that we are still bones and blood,

that for now, for now, our heft is still heated. Feel it?”

Every Wednesday this month, I’ll be writing about the month of November for the Paris Review. Read the first installment here.

September 26, 2017

Certain words you wonder how you could’ve gone

so long not...

Certain words you wonder how you could’ve gone

so long not knowing. One crossed my path this weekend. Spindrift. Do you know

it? It’s the spray blown from the crests of waves by the wind.

Here on the coast of the northeastern United

States, the hurricanes settled themselves at sea and did little else but panic

wind chimes, cause premature leaf detachment, and swell waves. And the spray

blew from the crests of the waves; spindrift gives the wind a shape, a white-grey

speed as waves hurl themselves toward shore. The spray, ripped from its crest,

seems to race the wave toward rock or beach.

The poets must know about spindrift, I

thought. They do.

“I sit listening/To the surf as it falls,”

wrote Galway Kinnell in a poem called “Spindrift” published in the New Yorker in 1964.

The

suck and inner boom

As

a wave tears free and crashes back

In

overlapping thunders going away down the beach.It

is the most we know of time,

And

it is our undermusic of eternity.

So waves’ thunder gives time a sound. And spindrift

gives wind a shape, moving like sparks flying off a fire’s jostled log. And if

waves speak to endlessness, to all time, the spray whistles now.

[Painting: Over the Sea 20 by Randall David Tipton]

September 14, 2017

We’re at work in a hive of shrinks. We’re

gutting two bathrooms...

We’re at work in a hive of shrinks. We’re

gutting two bathrooms in a building which holds the offices of psychiatrists

and psychologists and social workers.

We move among the therapists and their flow of

patients who sit in halls waiting for their session on the couch. They look just the same as any smattering of humanity you might

encounter of a day. Some look so sad. Some look vacant and lost. Some are

chipper and smile wide or scroll on their phones as if waiting for the bus. It

has helped pass the time, imagining what brings these people in, what their

specific species of woe is. Time can be sensed by the doors opening and closing,

the hours of the day passed in fifty-minute intervals.

It’s happened before, when the metaphors come

too apt and too easy. But we have pulled back walls here and torn up floors and

we have put our faces into what’s below the surface. And I will tell you: it is

foul. It is no place you want to be. And behind the doors of these doctors, a

similar excavating is taking place, a peeling back, a peering in, a squinting

into the shadowy parts, to the dark corners we conceal so well with our own

walls. It takes so much time to dig in; it’s scary in there; it’s confusing

and gross. We found a bird’s nest in the joists between the floors. A bird’s

nest, and a dead bird. A sick and snarled tangle of feather, wing, straw,

filth. And behind those doors, on all the couches, in all of our minds, those same strange nests

exist in the shadows.

And I’d like to say: and with sweat and effort

and exhaustion, it can all be cleaned out, leveled, set right! And it can. But

also I am tired of looking behind the walls. And sick of finding what we find

there.

September 7, 2017

The weekend started calm, an ease and optimism...

The weekend started calm, an ease and optimism that floated everyone

through the next days, despite the elevated pace and energy of a wedding taking

place, my young brother’s to his longtime love. Nerves and excitement, a frenzy

of prep: of last-minute seating chart changes, of husking corn, of placing

lanterns, of practicing walking in fancy shoes down a mulched path that would

serve as aisle. The energy shifted – from

the lulled and lapping drift of late summer to a more fevered pace, still

optimistic and fizzing with joy like the sparklers that’d get lit late that

night, but faster, time accelerating, so when the music stopped and the dancing

ended, I said quietly to no one in particular don’t go. A day marking a celebratory moment of change. And change

stirs this time of year, here in September when it’s still warm, an itch for

different, an itch to make things happen, a gold-glow embered sense of possibility. I

woke on the morning of the wedding from a dream. In it, some adult said, ‘first

you’re a child, then you’re fifty. It happens so fast.’ It held the gut-punch

force of truth and jolted me awake. My heart thudded in the sheets as in the

aftermath of nightmare. It happens so fast. There’s so much still to do.