Nina MacLaughlin's Blog, page 7

June 21, 2019

Happy solstice, everyone, happy first day of summer. In the...

Happy solstice, everyone, happy first day of summer. In the finale of this solstice series for the Paris Review, there’s pagan wildness, bonfires, tan lines, D.H. Lawrence, Janis Joplin, blood, time, memory, hot dogs. Dive in.

[Painting: Sonnenuntergeng an der see, 1921 by Max Pechstein]

June 17, 2019

The tension’s tighter this time of year. Yes, there’s license,...

The tension’s tighter this time of year. Yes, there’s license, yes,

there’s freedom, yes, there’s drink and rest and sex. But the days are

about to start getting shorter. Have you prepared for winter? Have you

prepared to die?

Continuing to keep it light for Part Three of my series on the summer solstice for the Paris Review.

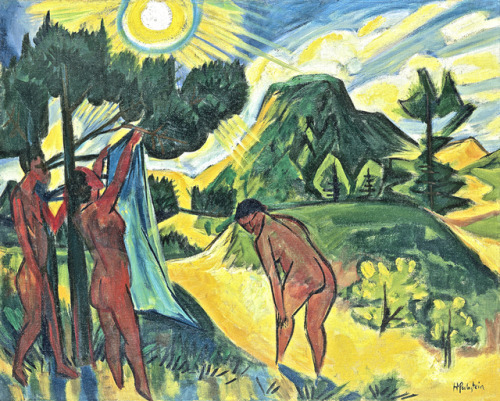

[Painting: Ein Sonntag by Max Pechstein]

June 7, 2019

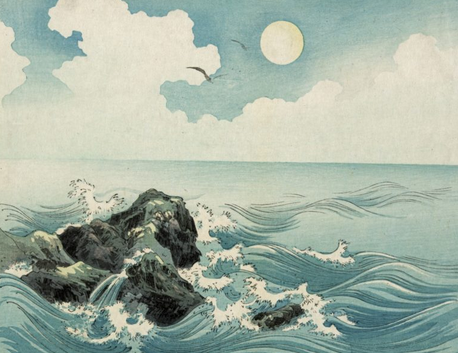

We enter water and we leave ourselves. Gravity loosens and we...

We enter water and we leave ourselves. Gravity loosens and we swim into a

slow trance, we swim into wisdom. And what is the wisdom? It is of

being un-separate. It is a temporary return to the unbroken planet,

where we exist as both whole and dissolved. In the dark-bright of water,

we’re wet at the throat, at the back of the neck, in the ears, on the

eyelids, and the water on the skin gives a literal cleansing. We emerge,

from waves onto beach, up the shining metal ladder off the side of a

pool, onto the twiggy banks of a river, onto a lakeshore surrounded by

pine forest, first smoke of campfires rising on the banks, and the world

is reset. We return to our selves, separate and distinct once again,

severed from the All, with only the memory of that quick glimpse into

the mystery of what was.

Part Two on a series on the summer solstice for the Paris Review Daily. It’s a lot about swimming.

[Painting: Max Pechstein, Frische Brise, 1921]

May 31, 2019

What’s the start of summer for you, the signal that it’s here?...

What’s the start of summer for you, the signal that it’s here? Is it the

last day of school? The lilacs or day lilies? First sleep with the

windows open? Smell of cut grass behind the gasoline of the lawnmower?

The fat red tomato sliced thin and salted? A sunburn? Shins sweating?

The first swim? The first hotdog off the grill? Throbbing light from the

fireflies? Campfire smoke in your hair? Is it the first day of June? Is

it the day when light’s longest? When your midday shadow’s shorter than

any other day? When the sun sets and sets and sets?

As we approach the heated season, I’ll be writing a series of essays on the summer solstice for the Paris Review. Here, the first installment, on what’s in the air this time of year.

May 24, 2019

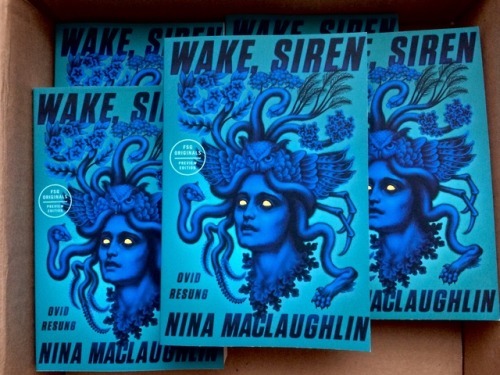

I wrote a book that re-tells stories from Ovid’s Metamorphoses...

I wrote a book that re-tells stories from Ovid’s Metamorphoses from the perspective of the female figures who were transformed. It’s called Wake, Siren and it’s coming out in November. This is what it looks like.

May 15, 2019

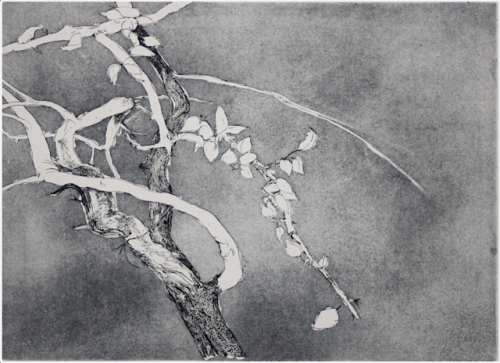

Making spoons teaches one to listen. To listen with the

eyes, to...

Making spoons teaches one to listen. To listen with the

eyes, to listen with the fingertips, to let the wood tell one what to do. Each

time a point comes in the carving when I think, impossible, I do not have the

skill to make this work. I tell myself to keep going, stay patient, and trust

the wood will start speaking, start telling me what I need to know. It’s a

funny act of trust—listening to the wood, respecting what it says, responding

to what it’s saying, and trusting that you’re hearing it in the right spirit,

with the right skill. One listens and responds with intuition (that blood-muscled-feathered voice in

the viscera), and patience, and honesty. It is a full body process, this listening, this giving of

attention.

April 13, 2019

Eight birch blanks—the crude pre-spoon shapes—live right now

in...

Eight birch blanks—the crude pre-spoon shapes—live right now

in my freezer, in there with the ice trays and the collection of vegetable

trimmings in a bag, beet greens, onion layers, scallion roots, cabbage hearts,

that someday maybe will go into a stock, who knows, they’ve been there for a

while now. The birch slabs sit stacked beside it all, the cold holding the

wood’s moisture in. And the feeling that pulses from the freezer every time I

walk by it, and especially when I open it and the cloud of cold escapes and

falls towards my feet and I see those pale pre-spoons, is one of extreme

potential.

“Potentia, like so

many other words, has had its meaning separated out, and has come, in our day,

to be both potency and potentiality,” writes potter M.C. Richards

in her book Centering, “that is to

say, both the power present and the power latent, that can but has not yet come

into being.” And she reminds me of the Latin that I’ve mostly lost, that power

and potential come from the same word, “and this is a wisdom,” she tells us. I

believe her. She writes that potentiality is itself a power, “a condition of

generative potency, a possibility in persons and things, not yet visible in

force but present in seed.”

The seeds go in. A birch builds itself from the soil. It

lives and lives then falls. I take some home, and now have the seeds of spoons,

filling the freezer with their potential energy. I’ll put my hands on one of

those slabs, feel its aliveness, listen to it as it tells me how to move. “The

handcrafts stand to perpetuate the living experience of contact with natural

elements,” Richards writes, “something primal, immediate, personal, material, a

dialogue between our dreams and the forces of nature.”

[Leonard Baskin, Apple Tree, 1962]

March 11, 2019

In the ocean, Katya dives. She attaches a weight around her...

In the ocean, Katya dives. She attaches a weight around her neck, one

pound, and head-first plunges. Treading water by the boat, we watch her

slow her heart, go blank, and slip into the ocean. She kicks like

mermaids do, her lungs packed with air enough to last the journey. It’s

darker where she goes, and colder. The sea was our first home, we know

the history. When we were fishes, its squelch and boil were too much, so

we started our slow haul toward shore, our gooey stagger into life on

land. We’ve forgotten most of what we used to know about the deep. Were

there sharks down there? Octopuses? Can you see the souls of the

drowned, whose lives are marked by stones above bodiless graves on land?

She wouldn’t say.

Pleased and proud to have a short story I wrote called “Life on Land” published on American Short Fiction. It’s very short and a little weird.

March 5, 2019

Every time I finish a spoon, do you know?, I want to put it in...

Every time I finish a spoon, do you know?, I want to put it in your hands so you can feel how smooth it is.

February 23, 2019

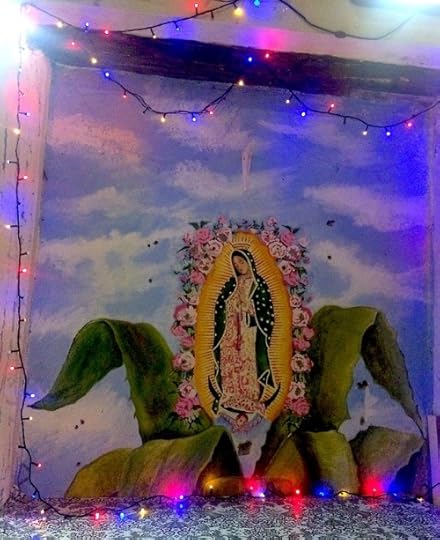

The bar is dingy, just-right dim, on a narrow street in

Mexico...

The bar is dingy, just-right dim, on a narrow street in

Mexico City. Murals of men raising glasses, of a woman rising out of a maguey

plant, shooting liquid from her nipple into the mouth of warrior, the bathroom

wall a smudge of graffiti, booths on one side of the narrow room in the back,

stools along the wall in the front. “Is this my favorite bar in the world?” I

asked on an evening earlier this fall. It might be.

Back again a few weeks ago, an altered mood to the night,

with four men: Alejandro who runs a small publishing house, he with a

high-pitched giggle and a gentle, bearded face; a novelist whose name I forget

in an eggplant-colored shirt (teased for it, what does it match, they laughed); Antonio, he in a Marilyn Manson

T-shirt, he who looked older then twenty-seven, he a writer of haiku; and a dark-eyed

poet. People selling things come into bars—flowers, trays full of candy and

little bags of salted snacks. The night earlier this month, a man came into the

bar with a box that hung from a leather strap around his neck with a cord

attached that looked like a jump rope, handles at each end. He stood by us in

silence. His face was ageless, sad. I am not from here. I did not know what was

going on.

All at once, the five of us stood in circle holding hands.

Antonio held one handle of the jump-rope cord and the poet held the other. I

held his other hand, and the novelist’s beside me. “What’s happening?” I said.

“It is only a game,” said the poet with dark eyes. The silent man flipped a switch on the box

around his neck and it whirred like a refrigerator and a buzzing in my palm and

through my wrist, and I gripped tighter to the men’s hands I held. The charge

got stronger, the men began to shout. I held on, electricity buzzing through my

wrist. “Fuck,” I said quietly. Vibration turning to vibration plus heat, a

teeth-buzzing hum, like lots of tiny creatures made of light biting on the

bones and blinking in the blood. Stronger, stronger. This game of chicken with

electricity, see who lets go first. I gripped the hands of the men on either

side of me, the charge moved through us all. The world slowed down, got silent

like the face of the man with the box around his neck, his eyes sunk deep into

his skull. Palms against palms, tingling all the way up my arms, across my

collar bones, and I knew, with deep and quiet clarity, oh, this is when I die, this

charge will reveal some wrongness in the electricity of my own heart, and it

will stop it all.

Gentle-faced Alejandro let go first, circuit broken. The

buzz in the body lived then faded like dying bugs. The silent man collected

bills and put them in a pouch and walked back into the night with the box

around his neck and he did not say a word. I did not die, not that night. Later,

Antonio broke a glass and recited a haiku. I recognized the words, calle, relámpago,

and perros. Road, lightning, dogs. Who needs more? “Tú eres un poeta,” I said

to him as I left the bar, and he looked shy and kissed my cheek and said things

I did not understand.