Nina MacLaughlin's Blog, page 13

November 13, 2016

What we talk about when we talk about rage

Since Tuesday night, what keeps rising like a burn blister

on the surface of my brain is all the times I’ve been told you’re being sensitive. All the times I’ve been told you’re taking things too seriously, too personally. All the times

I’ve been told, you’ve had every

privilege, what are you complaining about? All the times I’ve been told to shhhhhh. All the times I’ve been told to

take it easy.

I cannot shake these voices and I cannot shake the feeling

they provoke.

There’s a cauldron that exists inside me that starts to

seethe when these sorts of things are said, when I am being dismissed, quieted,

condescended to. And when the fire under this cauldron is lit, to a white

hotness that is nearly blinding, what it takes with it is my ability to be the

articulate and intelligent person I know myself to be. Something else takes

over, a pre-lingual fury, a heat that erases logic and coherent

argument and civility. In these moments, the experience is not just my own self

being demeaned or silenced; it is the entire history of women being demeaned or

silenced. And the weight of that, the condensed and hot feeling of outrage is,

at times, more than I know how to deal with, and certainly, in these moments,

more than I know how to rightly express. What goes is the impulse to kindly and

gently explain something. What comes is a wanting to smash faces. If it were a

sound, it would be a scream so loud it would make birds fall out of the sky.

This is rage. It is a feeling of blood in the cheeks, heart

bumping in the throat, whatever pocket that holds tears getting filled up

behind the eyes ready to spill, it is a stuttering, frenzied horrible, horrible

feeling. It comes from the helplessness of knowing: I cannot make you understand. You will never, never know. Like

approaching a smooth white wall that rises forever that you cannot penetrate,

that you cannot climb over to reach the other side, a maddening, impenetrable

stop.

This is rage, and I am finding myself wanting to admit that

it is in me. It is not attractive. It ranks as one of the very worst things I

know I can feel. It is scary. It frightens

people. It makes them uncomfortable.

But I have been made to feel uncomfortable. Every woman I

know has been made to feel uncomfortable. In ways subtle that grind like a dull

file across a piece of wood, in ways explicit like an unasked for touch from a

stranger. And right now I feel uncomfortable, and that cauldron is simmering

and I do not want it to cool. As ugly and frightening as it is. Because there

are things uglier and more frightening. The poet Mary Ruefle writes “Anger is

an emotion that is produced by fear. There are no exceptions.”

There are no exceptions. This is rage. And this is fear. And

I feel afraid. That suddenly there is increased license for the type of

silencing, demeaning, assaulting that erases a person’s personhood.

For a long time I thought it went without saying that I

support the safety and rights of people of color, of the LGBT community, of

Muslims, of immigrants, of women, of every disenfranchised group trying to stay

safe and have a voice. Doesn’t that just fucking go without saying? No. No. It doesn’t. Not right now. And I was wrong to think it went without saying before. So I say it. I am behind you. I am so

behind you. We have each other’s backs. And I hope I never see anyone being

silenced, insulted, demeaned, assaulted. And if I do I will come to your aid as

I hope you would come to mine.

In a much-read piece from the New York Review of Books, Masha Gessen writes rules for surviving

an autocracy. The whole piece is worth your time, but this section in

particular has been echoing in my head:

Rule #4 Be outraged … In the face

of the impulse to normalize, it is essential to maintain one’s capacity for

shock. This will lead people to call you unreasonable and hysterical, and to

accuse you of overreacting. It is no fun to be the only hysterical person in

the room. Prepare yourself.

Prepare yourself. Prepare yourself. I cannot stop hearing it.

Prepare yourself.

Take it easy. No. I

can’t. And won’t.

Prepare yourself.

September 29, 2016

Up on a ladder, high up on a ladder against a house on a

hill, I...

Up on a ladder, high up on a ladder against a house on a

hill, I was hammering shingles, and the tiny old woman who lives nextdoor,

climbed the stairs to her front door and said to me, “Oh, you are working hard.

Don’t you feel afraid up there?”

She is small with a cloud of blonde-white hair all around

her head. She could be eighty. She could be a hundred and eight.

“I try not to think about it,” I said, a big smile on my

face.

“Are you my new neighbor?” she asked.

“No, no,” I said, “just working here.”

“Well,” she said, “you are working hard, and my name is Lily

if you need anything.”

“Thank you,” I said. “I’m Nina.”

“Nina!,” she said. “You say your name is Nina?”

“Yes,” I said.

She put her hand over her heart. “I have a sister Nina,” she said.

“Well, it’s Ninotchka, but everyone calls her Nina, because who wants to be

Russian.” She had such warmth in her eyes. “Nina,” she said. “If you need

anything, you come. I am always here. You just come, love,” she said.

And I nearly fell off the ladder for joy.

September 20, 2016

A month before this summer started, I drove to my hometown

to...

A month before this summer started, I drove to my hometown

to run on roads I ran on when I was young, to trade my usual route on city

streets for hills, stone walls, wide barns, farmhouses, cows there munching

grass, empty fields. A warm, soft day, and I was feeling fine, air in and out

of my lungs, feeling well carried by the muscles in my legs, ponytail at swish

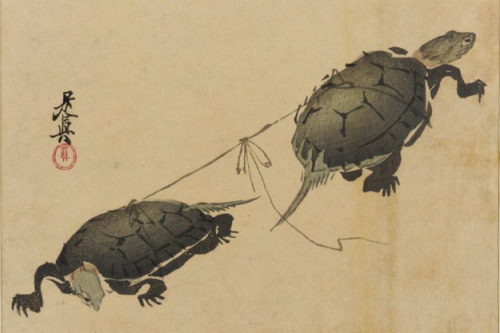

across my shoulders. Some miles in, near a vernal pond, a turtle had been

crushed, freshly so, run over by a car. I stopped to look. Flipped upside down,

the base of its shell was smooth, amber colored, and cracked. The under rim of

its top shell was striped with red, and the red of its blood on the road was a

red shocking in its aliveness. I crouched to get a better look. A small pile of

its guts, propelled out of its body, lay shining a few inches away, coiled like

a little heap of earthworms.

I am no haruspex, no augur. I cannot read the future in the

splay of viscera across the cratered cement of a suburban back road. I crouched

by this small dead thing on a day in the lead up to summer when the world was on

the verge of bursting, emerging in its lush summer dress like a girl coming

down the stairs in a gown. I crouched by the turtle and a car or two sped by

and I wondered, is this what normal people do?

Guts on the road and there’s no telling what will happen,

and here again we’re back to talk of what it is to be at home with question

marks, the struggle of not getting crushed and cracked open by the press of

immediate need. It’s hard knowing what you want because in it there’s the risk

you might not get it.

This morning, at the bottom of my bag, I found a slip of

paper, a fortune from a fortune cookie. You

have both a lot of ideas and the energy to put them into action. I do not

remember seeing this before. I have no idea where it came from. But I am

grateful for the timing of its appearance.

Done examining the turtle, I rose, continued on my run.

Before my heartrate had a chance to rise again, another chance for

prognostication, this time in the form of a frog who’d also been flattened by a

car, the entirety of its guts squeezed out of its mouth. Poor small friends,

crushed when the world was warming again, on the move when the season was new.

The risk of wanting, the risk of waking up to change. There were these two, the

future in the angle of their intestines, and what I can see from it now, what

those guts tell me now: there were others I couldn’t see, ones who’d made it

safe across the street, to live and thrive in the face of all the risks.

[Two Turtles by Shibata Zeshin]

September 13, 2016

In an essay called “Making House” in last Sunday’s New...

In an essay called “Making House” in last Sunday’s New York

Times Magazine, Rachel Cusk admits to be driven to the “brink of mental and

physical collapse” by the renovation of the London flat where she lives with

her daughters. “I caused walls to be knocked down and floors to be ripped up

and rooms to be gutted … with what at times seemed like magic and at others

sheer violence.”

Magic and violence. It’s a combination of conditions that

resonates right now. The magic and violence of a dismantling. The magic and

violence of having the way you’ve understood things get altered, of someone

coming in and shifting things so they are, for a time, unrecognizable, altered,

messy, stirred up, all upside-downed.

We’re at work on two big projects – taking down walls,

ripping up floors, gutting, gutting. It is a trauma, I think, for the house,

for the inhabitants. The physical and psychic disruption is acute. In

Somerville, we’ve destroyed a room to rebuild it into an enormous kitchen. The young

couple and their daughter, five years old, have no kitchen right now. A fridge

is tucked into a hall; there are mugs on the rim of the tub. The home becomes

something else, surrendered, for a time, to chaos, to dust, to horrific noise,

to strangers clomping up the back stairs with tools hanging from their waists.

This winter, we worked extending a small house in Cambridge.

The couple joked the experience nearly ended in divorce. They laughed when they

said it, but there was desperation in the air when we stood in front of the

sink and asked them, which side do you

want the dishwasher on. Not another decision. Not another compromise, pro

and con list, weighing of preferences. Exhaustion was written all over their

faces.

“To all except anguish, the mind soon adjusts,” Emily

Dickinson wrote in a letter. And so maybe one gets used to washing the mugs in the tub,

to the deafening screech of the saws. In between the hammerbangs last

week, in between the ear-pierce of the saw screaming through another plank of

two-by-eight, I could hear, on the other side of the plastic we’d hung from the

door, the mother teaching her five year old the alphabet.

The magic and the violence hold the promise, or, at very

least, the possibility, the potential, that it will, in time, come to feel like

home.

August 23, 2016

The ghosts live behind the walls. They live in the space

between...

The ghosts live behind the walls. They live in the space

between the ceiling and the floor. That’s where some of them live. A place

feels fine, regular, then the walls get bashed. That surface gets removed, tossed

out windows; dust swells, floats, falls, coats everything (floor, throat, stairs,

my hair), and a new space is exposed, dark and splintery, and the energy of the

room shifts. Not every house, of course. But this one, for sure.

I met a cat recently who maybe is actually a witch. I mostly

detest cats, for their haughtiness. This one had a ferocity in her eyes that

made it tricky to be in the same room. I lost a staring contest with her and

felt, in the aftermath, that engaging in it put me under a curse. I should’ve

known better. I admired the creature, and feared it.

There’s power in strange places these days. In between old

joists above the head, in the space between old studs in a stretch of wall

that’s just been opened, light touching places untouched for a century or more.

In the fierce eyes of a cat. On a sand dune which swells and shifts and

presents itself wide to the sky. Do you buy it? That once something is opened

up, things get altered, new energies swirl, enough that it registers as a buzz

in the blood? It’s August and the breeze is drying and the shadows are

shifting. Light finds its way in, even into windowless rooms.

August 22, 2016

The day started badly and got worse. Last week, for no...

The day started badly and got worse. Last week, for no good

reason except sometimes days go wrong, we struggled through each hour. Cuts

were off. Corners were sloppy. Nothing was level, plumb unachievable.

Instructions were misunderstood. Jokes weren’t landing. This summer, we’ve had

the help of a twenty-three-year-old kid from Washington State. He reminds me of

the freshman from Dazed and Confused,

the long-haired one who’s always pinching the bridge of his nose. He and I

stood looking at the landing we were framing outside, feeling tired and mad and

dumb.

“We’re tilting,” he said. I looked at him, thinking maybe he

was talking about the state of our small deck. “Do

you know that phrase?” he asked. I said I did not. “It’s from gaming,” he said.

“It’s when you start to fail, and because you’re failing, you keep failing, and

keep getting more frustrated, and that makes you fail even harder, and mistakes

just bring on other mistakes. That’s tilting.”

It was just the right encapsulation of the day. “Blind

leading the blind here today,” M. said when she joined us outside. “I mean,

what the fuck happened here?” she said, looking at the way four pieces of

two-by-six came together at a corner, none of them flush. We stood at the

corner and looked. And we all started laughing, dying laughing, because sometimes

days go so bad, and sometimes there’s no other reaction to be had, except to

fix it, which we did. “You know tomorrow will be better,” M. said. Which is

always the comfort. The next day is always better. And she was right. In the

first two hours of the next day, we got more done than the whole previous eight, tilting no longer, but upright, and on.

[Image from the Times Tribune Archives, on the building of the Pen-Can Highway, June 3, 1960]

August 16, 2016

Last night, my brother and I played catch in the street for

almost two hours. We hucked the football...

Last night, my brother and I played catch in the street for

almost two hours. We hucked the football back and forth. We talked and laughed.

Last night was my brother’s last night in Cambridge. About

an hour ago, I watched and waved as he and his wife drove away in a loaded U-Haul, headed

towards Missouri and a graduate program in creative writing that his wife will

start this fall.

Last summer, when things had gone so bad, my brother said to

me, ‘there’s an apartment opening up in my building, you should take a look.’ I

did. On a humid morning, I spent eight minutes looking at the place, and with

my hands shaking and tears welling, I wrote a check and signed a lease. It

meant the end of a six-year long relationship. It meant the start of some new

phase. The fact was: I needed rescuing. The fact was: I needed someone to throw

me a life preserver. I didn’t realize how much then, and it’s a hard thing to

admit, but I see it now. I see it now. In saying, hey, there’s this place, maybe you should

live here, my brother saved me.

“Isn’t it strange,” someone said to me recently, an only

child, incidentally, “to live in the same building as your sibling?”

“No,” I said. “It’s not strange. It’s really nice.”

The Mediterranean diet – all that fish and olive oil, all

those eggplants and red wine – has long been credited for the longevity of

Italians. But it turns out it’s only part about the food. They live in

proximity with their family; they take care of each other; they share meals and

conversation. It’s this, too, it’s been shown, that propels them deep into old

age. And it rings true. Weeks would go by when I wouldn’t see my brother, each

of us involved in our own lives and pursuits, but the comfort knowing he was

nearby was profound, and I’m only realizing how much so now, now that his place

has been emptied and he’s on I-90 heading west.

Last night we threw the football back and forth. We talked

about his nerves and his excitement about this move. We talked about our

parents and our great younger brother. We talked about old flames and nostalgias, about Kings

Quest IV, depression, friends, and love. The light began to disintegrate and

the crickets got loud. We tossed the football back and forth on our short

street near the Charles River, trying not to hit the parked cars, the

powerlines. His new river will be the Mississippi. That feels exciting.

I feel excited for him, for them, for the thrilling process

of the unfamiliar becoming familiar. I feel grateful and lucky and sad.

Last month, on the night of the Full Buck Moon, I went

outside to get a look. And at the same time, my brother and his wife appeared

on the sidewalk, and we all looked together at the big white brightness. What a

nice thing, to bump into your brother and his wife on a sidewalk to look at the

moon. What a nice thing, to throw a football in the street as light fades.

“My arm hurts.”

“Mine too.”

“You want to keep playing?”

“Yeah.”

August 13, 2016

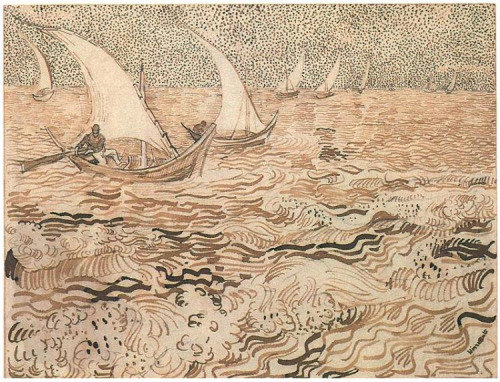

The Eldridge Tide and Pilot Book is like a Farmers’ Almanac

for...

The Eldridge Tide and Pilot Book is like a Farmers’ Almanac

for East Coast sailors. An annual guide, it’s full of tables, charts, and lists

of lighthouses, buoys, currents, tides. Short articles and stories discuss

maritime history, nautical astronomy, fishing tips. Its cover is every year an

unmistakable yellow, a yellow that speaks to a beam of light through fog, of the

first lick of sun rising over the horizon. I’ve heard my friend Jenny, who

recently took helm of the book along with her husband Peter, describe the color of an old farmhouse as

Eldridge yellow.

I spent some hours yesterday helping Jenny with the book. We

sat at her dining room table as fans hummed and a tired air conditioner clicked

and cooled in the window. Her two dogs lay splayed, bellies up, on pillows

nearby, and her small daughter ate cantaloupe in the kitchen with a sitter.

Hottest day of summer so far, and you could feel the heat accumulating outside.

I don’t know much about the ocean. I swim in it, poorly,

enthusiastically. It is, as a close friend said the other night on the phone, a

guaranteed re-setter: impossible to see it, be in it, and not be altered for it.

Last summer, which was so bad, I would go north to the beach and sit and watch the

water move. The waves don’t care, I

thought and felt, and it was one of the few things that helped get me through. The waves don’t care. Sweat, tears, and

the sea: I’m a believer in those cures.

Jenny read times outloud, of moonrises and moonsets, of

sunrises and sunsets, and I verified that what she read from the official

government listings matched up with the version I had in front of me. I felt

the days lengthen and shorten as we moved through the months. I saw the moon swell

and vanish. The way light moves across the year! It felt like secret knowledge,

ancient, sacred. Grounding and thrilling at once. The way it feels to grow a

tomato, maybe, or have a sense of which way the wind blows. To hold this guide

is to feel in possession of something powerful, essential, and true. Shifting

planets, the sun’s sweep across the sky, the rise and fall of seas – it’s

possible to find our way by the stars, this yellow book reminds us. Lie easy

with the tide, and the waves will bring you home.

[Vincent van Gogh, Fishing Boats]

August 10, 2016

On a damp day last week, I spent seven hours digging a hole.

It...

On a damp day last week, I spent seven hours digging a hole.

It was, at the end, eighteen inches wide and four feet down to get below the

frost line so ice won’t pitch the posts of the porch we’re building on the back

of a house on a hill. Typically, it would be a morning’s work, if that. But

there were roots and rocks and the earth was clay, hard-packed, and stubborn.

And I had stayed up late the night before, was blurred

around the edges, feeling calm, dismantled. A hole, for my fuzzed and reeling

head, was the best I could hope for – away from the screams and sharp spinning blades of the

saws. So simple: here is the earth, make some of it go away.

“Nice hole,” one of the demo guys winked at me as he filled

up the doorway before returning to his louder, dirtier work inside chipping

away at a chimney that was being removed from the house in a process like

closing up a throat. I smiled, blushed, he laughed and wiped soot across his

forehead and thumped back to the bricks.

Four feet is a surprising depth, when you stand over the

hole and look down into the earth. It makes you think of:

Treasure

Tunnels

Creatures that burrow

Creatures that see in the dark

Escaping

Darkness

Water

China

Graves

Opening

Opening

Opening

July 25, 2016

Before and after. The back of the house faced the south. We...

Before and after. The back of the house faced the south. We worked daylong in

the sun, sweating as it described its arc across the sky above this

double-decker in Arlington. The tomatoes got fatter during our two weeks

building these decks, and when the woman who owned the place came out to her

gardens, the smell of basil – that dense, licoricey smell of high summer –

lingered in the air and won, temporarily, against the smell of the sunscreen

and sawdust that coated our skin.