Alexandra Louise Uitdenbogerd's Blog, page 2

May 7, 2025

Episode 2: Easy Authentic Sentences from French Classics

On this page are short extracts, titles and sentences which occur in classic French texts and only use the vocabulary of Episode 2 of my Gnomeville comic book series, that is, the twenty most frequently occurring words in French newspapers plus exact cognates and names. Even easier sentences are found on the Episode 1 page. (I may update these lists periodically, when I find more things with my scripts.)

Qui ?

Qui est Agostino ?

Qui est-il ?

Il change de place !

L’Europe !

Au railway !

En route !

Une avalanche ?

Au Louvre.

Du cardinal.

De la patience, Athos.

Il est absent.

Du courage !

Il est saint !

Il est excellent.

En vain.

Il ignore le riche, il ignore le noble.

L’addition finale.

Une simple promenade d’amateur.

Des biscuits !

Des sardines !

Il est dans un milieu abominable.

L’animal !

Des talents !

April 24, 2025

Common One-Word Sentences in the French Classics

While exploring French readability and the fact that sentence length is a key factor for English speakers learning French, I thought I’d take it to the extreme and see what are the most common one-word sentences in French literature. Here is the top 20. Note that it is highly influenced by Les Trois Mousquetaires, which is a sizeable portion of the corpus and responsible for about half the occurrences of “diable”.

AhOhNonHélasOuiQuoiEhCommentPourquoiDiableBahTiensAmenMoiBonVraimentMonsieurJamaisPardieuHéIn a different corpus less dominated by Les Trois Mousquetaires, the following were also found in the top 20:

AllonsBienAdieuRienJamaisIn a modern corpus I think we would find different expletive-like exclamations than “Diable”, “Parbleu”, and “Pardieu”. A common one these days seems to be “Putain!”, or somewhat less extreme “Punaise!”. Maybe I’ll try to process the French movie subtitle corpus at some point to get a more up to date glimpse at one-word sentences in French.

April 8, 2025

A tale of three French picture books: passé simple is not that hard!

One of the weird things about studying French is that we seem to have three levels:

Beginners use present tense, imperatives, infinitives, and future proche; Intermediate learners use passé composé, imparfait, future and conditional tensesAdvanced learners use passé simple and subjonctifYet, if we look at picture books written for French children, many use passé simple straight off.

I remember when I started reading (in English) in Grade 1 of primary school, one thing I had to get used to was constructs like “said Dora”. It doesn’t happen in spoken English, so felt a little weird. But it wasn’t overly difficult. Perhaps people from English-speaking backgrounds who had stories read to them would have been familiar with that already before reading it. The same thing must be true for French children reading or hearing passé simple. It’s a little different but not hard.

I recently read three French picture books. The first (Le Grand Antonio by Élise Gravel) was a fairly easy one with few words, written in present tense. The second (Quel est mon superpouvoir? by Aviaq Johnston) was a translation from English, written in passé simple (and imparfait). It was a comfortable read for me. The third (Dounia by Marya Zarif) was (mostly) written in present tense but was more difficult due to its vocabulary and more descriptive text. It is obvious to me that it is possible for texts in passé simple to be easier than those in the easiest tenses.

The thing is, you don’t need to know how to conjugate passé simple to read it. You just need to recognise the endings of third person singular (3ps) and plural (3pp) for regular verbs plus know a few of the irregular verbs. Here they are.

For -er verbs, 3ps ends in -a and 3pp ends in -èrent.

For -ir and -re verbs, 3ps ends in -it and 3pp in -irent.

You may come across a few -oir verbs, which have -ut and -urent.

The main irregular verbs to watch out for are:

être: fut, furent

faire: fit, firent

avoir: eut, eurent

The regular ones should not pose any problems. The avoir ones are recognisable thanks to already knowing the past participle of avoir (eu). The main difficulty is not mixing up the être and faire words. A simple rule is that faire has an ‘i’ in it, and so does its passé simple conjugation.

I hope that helps. It helps me.

March 31, 2025

French Comic for Beginners Video

A slide show of panels from Episodes 1 to 3 of my Gnomeville comic for beginners learning French with an English-speaking background is now up on Youtube, accompanying the song of the third episode. Note that there are spoilers, if you are wanting to wait until you’ve read the comics.

March 22, 2025

Beginner French Resources

tldr: Easy French sentences from classics here.

Years ago I was tinkering with creating my beginner comic book in French, and then researching what made things easy to read in French for those with English speaking background. I learnt that the two main aspects that characterise text difficulty are grammar and vocabulary, with other aspects usually having a much smaller role to play. Through my own research, inspired by my own frustration and anecdotal experience, I learnt that for French the typical readability measures that use word length or even how common a word is for vocabulary difficulty just don’t work for people with English speaking backgrounds. This is because so many of the longer “difficult” words in French are identical to those in English, or close enough not to matter. My experiment demonstrated that you may as well just use sentence length to decide on difficulty, being the simplest measure of grammatical complexity. Despite this, vocabulary matters. It’s just that the words that are difficult are differently distributed than for languages that don’t have this peculiar French-English relationship.

In another of my experiments, I tried to filter a large collection of French text to find extracts that are easy for English speakers. While the extracts that are very easy are not long, they do exist. It’s a matter of playing around with the constraints to get something sizeable. It should also be noted that the text I used consists of French classics, which can be challenging to read. Anyway, it’s been a while since I looked at this. The other day I created a page on this site that contains all the sentences and extracts I found that restrict themselves to the vocabulary and grammar of Episode 1 of my comic book, (le, la, les, de, du, des, et, est, se, que, and present tense third person singular of -er verbs) plus cognates and names. I hope it is useful. More to come.

March 19, 2025

It’s not too late for your free beginner French comic from Amazon

Episode 2 of the Gnomeville beginner French comic book series is still available for free on Amazon until Friday. Episode 1 is still discounted on Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk in a countdown deal that increases every couple of days. I hope you enjoy it!

March 10, 2025

Freebie French Beginner Comic ebook Soon

Just a heads up. On Monday 17th March, Episode 2 of the Gnomeville beginner French comic book series will be available for free on Amazon for five days. Episode 1 will also be available at the minimum 0.99 price on Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk in a countdown deal that increases every couple of days. Mark the date in your calendar!

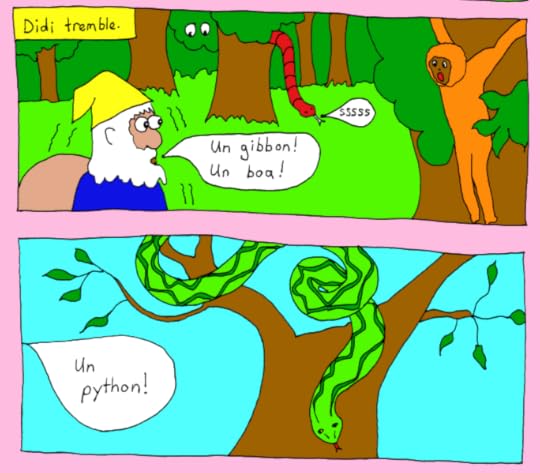

Excerpt from Episode 2 of Gnomeville: Dragon! – a series of comic books written in French for beginners with an English speaking background. Episode 2 only assumes that you know the following words that are covered in Episode 1: le, la, les, et, est, de, du, des, un, une, que, se. The story so far is summarised on the first page of Episode 2.

Excerpt from Episode 2 of Gnomeville: Dragon! – a series of comic books written in French for beginners with an English speaking background. Episode 2 only assumes that you know the following words that are covered in Episode 1: le, la, les, et, est, de, du, des, un, une, que, se. The story so far is summarised on the first page of Episode 2.

February 28, 2025

Comic Books versus Text-Only Books for Language Learning

Recently I have been reading a few comics in French, mainly by French-Canadian authors, or translated by them. The target audience for most of them is children and young adults. It had me thinking again about how best to grade comics in terms of difficulty.

My experience in attempting to read various Japanese books for children or learners showed me that it is possible to read a picture book that is really just an illustrated vocabulary without knowing any of the words beforehand. At the other extreme, it is theoretically possible to read everything in a parallel text, since the translation is right there to refer to, just very slow if every sentence needs to be analysed. That is known as “intensive reading”, which has been shown to be less useful than “extensive reading” for language acquisition. Complete glosses similarly make it possible to read a text without prior knowledge of the language, albeit with lots of interruptions to look things up.

Translations and glosses aside, a comic book will be easier than its text presented without illustration, since the illustrations provide clues to what is happening. It is also easier than text describing the same scenes provided by illustrations – a point that was made elsewhere in favour of learning language from comic books. In other words, “a picture paints a thousand words”.

In general, there is more dialogue and less descriptive text in comics, compared to novels, so the sentences are shorter on average. (This also applies to scripts of plays.) In addition, the pictures give clues as to what the text is about. A further benefit is that it often provides more examples of speech than would be found in a novel – or at least, as a proportion of the text read. This can be useful for absorbing speech patterns, particularly for people who are not exposed to much speech directly.

While the shorter average sentence length means that comic book text will generally be scored as easier than text from novels by readability measures, I think that a measure of difficulty of a comic may need to consider whether concrete nouns are illustrated when used. For example, a picture containing a wild boar with the text clearly indicating that it is “un sanglier” could be almost as easy as reading a French-English cognate, such as “village”. Or perhaps it is roughly equivalent to having a gloss entry, albeit introduced in the story instead of in a footnote.

Either way, comic books should be easier to read than books that have no illustrations. See my list of easy comic books in French for some that are a good starting point for beginners.

April 20, 2024

Review: Kill the French

Today I came across the book Kill the French by Vincent Serrano Guerra in a list of recommendations on Amazon and thought I would have a look. It appears to follow similar principles to others that do strict vocabulary control, pioneered by Michael West in the early years of the 20th century: restrict to cognates, introduce frequently occurring words first, include repetition, and slowly build up the assumed vocabulary. The author has also followed the principle of spaced repetition with the goal that readers will retain vocabulary at optimum levels. So how does it compare to other books and comics that do the same thing? Let’s have a look.

I have analysed approximately the first 100 words, which covers the Day 1 text and the title of the Day 2 text. According to Style, it has an average sentence length of 8.8 words and an average word length of 4.3. Word lengths don’t really tell us much for French, since longer words tend to often be easy for those with an English-speaking background. Sentence lengths do, however, have a stronger impact on readability.

Other stats on the sample: vocabulary is 45 words out of 95 words of text, making a vocabulary density (type-token ratio) of 0.47. Naturally the author has made heavy use of cognates. Some of these are exact cognates, such as “lion”, and in other cases they are more challenging without context, such as “musée”. If we assume that all cognates are known, then the assumed vocabulary size for 95% coverage is 41 (when words are ranked in general frequency order), which is an excellent achievement. The only books in my collection that achieve that level or better are:

RankTitleRequired Vocabulary Size for 95% Coverage1Gnomeville 2: Les pythons et les potions162Gnomeville 1: Introductions253Longman’s Modern French Course Part 1354Gnomeville 3: Les six protections de la potion405Kill the French41

So from the perspective of readability in French for people with an English-speaking background, I put it at the same level as Gnomeville 3 initially, as they both have similar sentence lengths as well as vocabulary coverage.

Unfortunately, like many graded readers out there, the text of Kill the French is quite dull. I checked the 18th day in the sample to see if it was more interesting, having gained extra vocabulary. Sadly, no. I can’t comment on the final stories in the book, which may be more interesting, since I have only examined the sample.

So, here is my conclusion. If you are an absolute beginner in French and are a huge fan of spaced repetition-based learning and willing to put up with texts that are mildly interesting at best, then this is an excellent graded reader for getting you to become familiar with the 500 most frequent French words efficiently. It certainly beats just memorising vocabulary in isolation. The Gnomeville comics may be more exciting and fun, but unfortunately they currently only take you to a frequent vocabulary of about 30, until the author gets cracking with the rest of the series. Perhaps the best approach at this stage is to use both together.

The first day of Kill the French uses frequent words that are introduced in Gnomeville Episodes 1 to 3. All except “avec” are introduced in the first two episodes. Day 2 introduces two words occurring in Episode 1, one from Episode 2, and one that doesn’t feature in the Gnomeville series yet, since it is far less frequent in text. Gnomeville‘s first two episodes introduce the twenty most frequent words occurring in French newspapers, which is a slightly different frequency profile to spoken language, and somewhat different to other text corpora. Kill the French introduces words in an order that doesn’t resemble any specific corpus frequency list but they are still frequent words. For example, the second day includes the word “aussi”, which in movie vocabulary ranks about 91, in books at 78, and in the Minnesota spoken corpus, at 79. But, it is still a frequent word, and I know from personal experience that being a bit flexible about the order of introduced words makes it easier to produce a coherent story.

Given that the order of word introduction varies enough that words will be introduced in one book and not the other, it doesn’t really matter too much which you read first. You could, for example, read Day 1, then reward yourself with Episode 1, then after Day 2, do the same with Episode 2. Day 3 is where the two texts diverge the most in terms of vocabulary, but there is still overlap. After that, you are stuck with Kill the French. But at some point you might be able to switch to Première Étape: Basic French Readings: Alternate Series by Otto Bond (published 1937), if you can locate a copy. According to my stats the expected vocabulary works out to 316, but it is another principled graded reader, using cognates, frequent words, and slowly adding new words as you read. It’s also an entertaining read. However, from memory, it does use more difficult tenses typically found in French literature right from the start, so can be challenging grammatically. The average sentence length is also quite long, making it potentially daunting.

In summary, I recommend using Kill the French in the following manner: for the first three days, read the day’s material and follow it with an episode of Gnomeville. After that, if you can keep going with the spaced repetition from Kill the French for about 100 days, you then might be able to start reading Première Étape: Basic French Readings: Alternate Series, which is interesting right from the start with an initial vocabulary of 97 frequent words and Si Nous Lisions, which starts being interesting from Chapter 6 with a vocabulary of about 100 words. Best of luck!

September 4, 2023

Musing about Ratings

My comics get the full range of ratings and that’s ok. Sure, the first time I got a 1-star rating it hurt, and I did some soul searching to try to figure out why someone would do that. But it is a reader’s right to rate as they will.

A year or two ago I read a BookBub blog written by a successful independent author. He was very passionate in his belief that nobody should give low ratings to books, even if that is a sincere rating. It can have a negative impact on the author, both in their ability and motivation to create, and on their income. In my experience, my motivation to follow my creative spark is easily impacted by both negative and positive comments that I receive. Fortunately the positive comments can counteract the negative ones.

Having gone through the academic life of submitting research papers to be reviewed, I have developed a more philosophical stance regarding ratings. As long as someone is given feedback that they can act on in order to improve, a negative review is ok. Therefore my preference is this. Give a 1-star rating if you honestly feel that way and want to express that for whatever reason, but please give a review with it, so the author has some idea about why you feel that way. It can be just one or two words. Here are some one-word examples:

boringdatedunoriginalclichéedinconsistentblokeygirlykid-litmisleadingplotlesscharacterlesssuspenselessuneditedilliterateungrammaticalGiven one of these one-word reviews, the author will know whether to work on plot, characterisation, writing, or factual content. If the review is “blokey”, “girly”, “kid-lit” or similar, the story may still be ok. Perhaps its nature wasn’t clearly indicated in the blurb for the story, leading to the wrong audience finding the work. The better the blurb gives clues as to the type of work, the greater the chance that reviews received will be higher, since those who are not the intended audience will give it a miss, and its intended audience will be more likely to find it.

Alexandra Louise Uitdenbogerd's Blog