Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 77

March 1, 2017

A Touch Of Paradise

'Kakkathuruthu', an island on the Vembanad lake in Kerala has hit the international spotlight when it was featured in the National Geographic story, 'Around The World In 24 Hours'

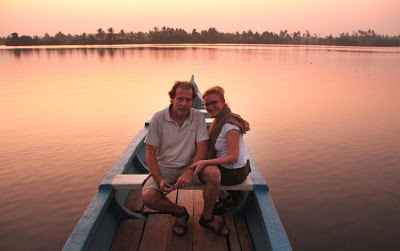

'Kakkathuruthu', an island on the Vembanad lake in Kerala has hit the international spotlight when it was featured in the National Geographic story, 'Around The World In 24 Hours'Photos: Marco and Valerie Ferrand of France. Pics by Albin Mathew

By Shevlin Sebastian

Marco and Valerie Ferrand of France lean back, while sitting on a boat, on 0a recent Wednesday evening. The scene is serene: On the Vembanad lake, 18 kms from Kochi, the water is placid. There is a deep silence, except for the soft sounds of the paddle used by boatman Shaji. The sun has set. But twilight is yet to come in. All around, there are small islands.

“Last week, we were in the Meenakshi Temple at Madurai,” says Valerie. “It was so noisy, but fun: the drum beats, large crowds, and the joyful smiles on the faces. So, this is the perfect environment for my husband and I to recover.”

After an hour's ride, the boat returns to Kakkathuruthu (Island of crows). The place hit the international spotlight when it was featured in the National Geographic feature, 'Around The World in 24 hours': one exotic place is featured for every hour (See link: http://www.nationalgeographic.com/tra...)

And for 6 p.m. National Geographic editor George W Stone wrote:'Sunset in Kerala is greeted by a series of rituals. Here, on Kakkathuruthu, a tiny island in Kerala’s tangled backwaters, children leap into shallow pools. Women in saris head home in skiffs. Fishermen light lamps and cast nets into the lagoon. Bats swoop across the horizon snapping up moths. Shadows lengthen, the sky shifts from pale blue to sapphire, and the emerald-fringed 'island of crows' – the Malayalam name for this sandy spot along the Malabar coast – embraces night.'

In December, 2015, George had stayed, with a couple of friends, at the Kayal Island Retreat, at one end of Kakkathuruthu. “I had no idea George was going to write about the place,” says resort owner Maneesha Panicker. “But once the item appeared, [in October, 2016] it went viral.” And the resort has been house-full ever since.

Kakkathuruthu is similar to many islands in the area. There are numerous coconut trees, wildly growing grass and plants, and, in between, several small houses. Around 350 families or a total of a thousand people live on this 4 km long island, with a width of one km. “They are primarily fishermen, farmers and labourers,” says Shantha Panicker, Maneesha's mother.

There is a government ferry at one end. At the other end, there is a man who runs a boat privately. The charge is Rs 5 one way. “To go to school, hospital, see a film, or get provisions, they have to go to the mainland by boat,” says Shantha.

But the people don't mind. Sindhu Thirumeni, 38, a classical singer, says, “We like it here. There is no pollution, no crowds, no noise. And it is such a healthy place to live.”

And they eat healthy, too. At one side there is an organic farm. “And now, our island has become famous,” says a smiling Sindhu. “We feel good about it.”

(Sunday Magazine, The New Indian Express, South India and Delhi)

Published on March 01, 2017 23:32

February 28, 2017

Praising God In A New Way

Playback singer Franco Simon has brought out a Christian meditation album, 'Moran Amekh', in Sanskrit

Playback singer Franco Simon has brought out a Christian meditation album, 'Moran Amekh', in SanskritPhoto by Albin Mathew By Shevlin Sebastian Every morning, in Orlando, USA, when Poulose Kuyiladan took his five-year-old autistic son, George, to school he faced a problem. “As soon as he got into the car, George jumped up and down,” says Paulose, a businessman. “Once he suddenly opened the door and ran out.” But, inadvertently, one day, Paulose solved the problem. He placed a CD called 'Moran Amekh' in the car stereo. As the music grew in volume, George calmed down. Thereafter, Paulose has always played the CD. And things have been quiet ever since inside the car. 'Moran Amekh' is a Christian meditation album in Sanskrit. It has been produced by Indian playback singer Franco Simon, and will be formally launched in mid-January. Incidentally, the words, 'Moran Amekh', in the Aramaic language used by Jesus Christ, means, 'The Lord Be With You'. Franco wanted to do an album in Sanskrit because there is a texture and divinity in the language. “This cannot be seen in any other language,” he says. “I can say this with certainty because I listen to a lot of world music.” Initially, Franco faced the problem of getting somebody to write Christian lyrics in Sanskrit. After a four-year search, he came across retired Sanskrit professor Dr. K U Chacko who did the job. Thereafter, Franco assembled a team of talented musicians. They included Franco's own uncle, the national award-winning Mollywood composer, Ousepachan (violin), Rajesh Cherthala (flute), Sandeep Anand (guitar), KJ Paulson (sitar), Dr. Bhavya Lakshmi (Carnatic violin), KO Gopi (shehnai), William Francis (keyboard), and Mithun Jayaraj (vocals). In order to create a reverb effect (sound reflection capture), it was done at the Our Lady of Doloures Basilica in Thrissur. This is a Gothic structure, with a very high ceiling. “We worked through the night,” says Franco. Apart from the musicians, there was a group of singers who rendered a hypnotic chant. “The orchestral tones contain theta waves and binaural beats,” says Franco. “This is a frequency where you feel most relaxed. So when listeners, who are stressed out and low in energy, listen to the songs they will calm down.” On the album, there are eight songs, ranging in time from 10 to 30 minutes. “The first one, a wake-up song called 'Yesusuprabhatham', has a faster tempo,” says Franco. “The rest are slow and meditative.” Incidentally, Franco has worked on meditative albums before. As a member of 'Band 7' a Hindi pop group, they brought out eight meditative albums for Cosmic Music, apart from a pop album called 'Yeh Zindagani'.

Meanwhile, he admits that this labour of love, which is available on YouTube, has burnt a hole in his pocket. “My parents, who live in the US, contributed a sizeable sum, apart from my brother,” he says. “But I have no regrets. I believe that as people get more and more stressed, there is an urgent need for meditative music. And this is my gift to the world.”

(Sunday Magazine, The New Indian Express, South India and Delhi)

Published on February 28, 2017 23:25

February 27, 2017

In Pole Position

Jinu Joy talks about his experiences as a pole performer and his foray into Mollywood

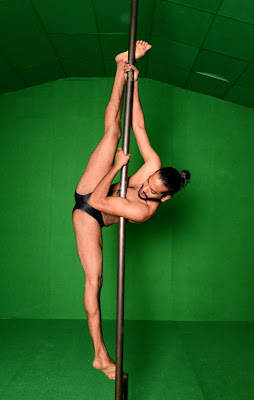

Jinu Joy talks about his experiences as a pole performer and his foray into MollywoodBy Shevlin Sebastian

Photo of Jinu Joy (first pic) by Albin Mathew

During the 'Asia’s Got Talent' audition, at Kuala Lumpur, sometime ago, Jinu Joy stands next to a pole, slightly thicker than a pipe. He is bare-bodied and only wears a tight-fitting brown shorts.

At the nod of the judges - music producer David Foster, and singers Van Ness Wu, Anggun, and Melanie C - Jinu jumps on to the pole, grabs it with both hands, turns his head downwards, his legs stretched upwards from the pole. So sudden is the movement that Melanie opens her mouth in surprise.

Then Jinu speeds up to the top, turns 360 degrees and stares downwards, his legs elongated. Then he holds tightly to the pole, stretches his legs sideways, straight out, almost as if gravity does not exist. He does several twists and turns during his performance.

Later, the judges are locked at two for and one against. And it needed Melanie's decisive nod for Jinu to go to the next round.

Unfortunately, that's when Jinu's luck ran out. When he returned to Kochi, before the shoot of the semi-final, he fractured his leg, while doing a performance and hence could no longer participate.

“It has been a disappointment, but that's part of life,” he says.

Jinu has been a full-time pole dancer for 11 years now. From childhood, he had been very flexible. When he was invited to take part in a reality show on television, Jinu wanted to try something different. That was when he got the idea to do something on a pole. He learnt the correct technique by closely watching pole performances on You Tube.

Incidentally, the length of a pole is 12 feet. It rests on a base which has four legs. “These legs should be eight feet in length,” he says. “That ensures that the pole does not fall, and I am able to maintain my balance.”

Thus far, Jinu has performed in countries, like the United Arab Emirates, the USA, Britain, Kuwait, Muscat, Bahrain, Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand.

“I am always invited by Malayali associations, but I go as part of a troupe,” says Jinu. “There are many other items, apart from my performance.”

Meanwhile, two years ago, Jinu's life changed in a most unexpected manner. He had given a performance at an event in Kochi. In the audience was Mollywood actor Anoop Menon. He had come to receive a 'Young Talent' award. But when he got the award, he said, on stage, “I am grateful to get this award, but I think Jinu Joy deserves it more.” And right in front of everybody Anoop presented the award to Jinu.

Later when Jinu went to thank Anoop, the latter said, “Would you like to act in films?” When Jinu nodded eagerly, Anoop said, “Come to the shoot at Fort Kochi tomorrow.”

The film, 'Beautiful', directed by VK Prakash, starred Jayasurya and Anoop. Jinu played the role of a thief. In one scene, which can be seen on You Tube, he jumped from the second floor to the ground, without any safety equipment, and landed smoothly. "Prakash Sir is my mentor," says Jinu.

Some of the other films he worked in, included, 'To Let Ambadi Talkies', 'Silence' (where he played the villain opposite Mammooty), 'Ormayundo Ee Mukham', 'Sathya', and 'Careful', whose shoot is going on at present.

As for the future, Jinu plans to continue to act in films and perform on the pole. “I also want to start a pole school,” he says.

(The New Indian Express, Kochi and Thiruvananthapuram)

Published on February 27, 2017 01:46

February 22, 2017

A Fake Riot

COLUMN: LOCATION DIARY

COLUMN: LOCATION DIARYDirector Basil Joseph talks about his experiences in the upcoming film, 'Godha' as well as 'Kunjiramayanam'

Photos: Basil Joseph. Photo by Melton Antony. A fan taking a selfie with Dipil Dev in Mohali

By Shevlin Sebastian

In December, 2016, the cast and crew of the upcoming Mollywood film, 'Godha', was shooting at Mohali in Punjab. “The people there were not used to seeing a film shoot,” says director Basil Joseph. “Whenever we placed a camera on the road, a large crowd would gather around us.”

In the film, there is a scene where a police officer (played by Bollywood actor Vineet Sharma), is supposed to move away from a riot situation, and make a call while standing in front of a Gypsy car.

Basil was pondering over how to shoot the scene, without a crowd gathering around. That was when he got an idea. He narrated it to the crew.

Soon, cameraman Bijith Dharmadam, Associate Directors Dipil Dev and Jithin Lal, along with Associate Cameraman Sharath Shaji stood some distance away from the Gypsy. Then Jithin picked up a small camera and said, “Action.” Dipil and the others started fighting.

As expected a crowd gathered around. There were a lot of shouting and yelling. “In the meantime, we placed a camera inside a shop and surreptitiously shot the scene of the police officer speaking on the phone, while the riot was occurring behind him,” says Basil.

So, thanks to a fake shoot, Basil could do his work in peace.

Meanwhile, the crowd mobbed Dipil thinking that he was the hero. Several took selfies. Children ran after him. Basil heard the people say, “South Indian Superstar.”

The crew had a huge laugh later on.

Basil also had fun during the shoot of his debut film, 'Kunjiramayanam'. On the first day, in April, 2015, the crew gathered around at Udumalaipettai, near Pollachi. “All the technicians, including myself, were in the age group of 24-25,” says Basil. “Most of us wore T-shirts and Bermuda shorts.”

Senior actor Dinesh Panicker stepped outside the hotel. He looked at the crowd, and said loudly, “Are these schoolchildren? Has the school bell rung?”

Another senior artiste, Seema G Nair, looked puzzled. She asked, “Who is the director? And the cameraman?” Basil quickly introduced himself and the others.

Meanwhile, the shoot of 'Godha' shifted from Mohali to Palani. It was a single shot of 3 ½ minutes length. “This was the title sequence,” says Basil. “It was a recreation of a wrestling scene from 1990. To convey that it is the past, I wanted it to be like a tableau, with the 600 extras standing without making any movement.”

The plan was like this: On a crane, cameraman Vishnu Sharma would be dangling from a height of 60 feet. Then he would come down to the ground and in a smooth movement run towards the road, where there is a jib (a boom device with a camera at one end). Then Vishnu would mount the camera on the jib and move towards the godha (wrestling pit), all the while moving among the extras. “We started rehearsals in the afternoon,” says Basil. “It took us a long time to make the Tamilians understand what we needed.”

The whole night went past, but the crew could not get the right shot. By dawn, the extras felt frustrated. Despite the crew's pleas, they began moving away. In desperation, the crew tried their last shot at 6 a.m. “There was a blue sky just before dawn,” says Basil. “It looked good in the frame. And it was with this last shot that we managed to get it right, in the nick of time.”

(The New Indian Express, Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kozhikode)

Published on February 22, 2017 22:03

An Artistic Fusion

The New York-based Alexander Gorlizki did a creative collaboration with Indian artistes. The results can be seen at an exhibition, in Fort Kochi

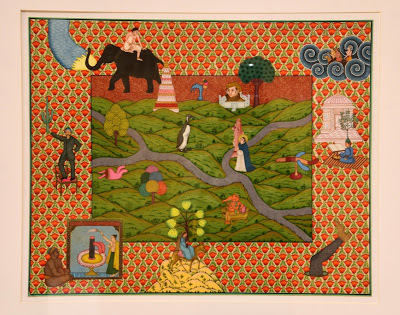

The New York-based Alexander Gorlizki did a creative collaboration with Indian artistes. The results can be seen at an exhibition, in Fort KochiPhotos: Alexander Gorlizki; the miniature painting, 'Wish You Were Here'; the lingam tree. Photos by Albin Mathew

By Shevlin Sebastian

When the US-based artist Alexander Gorlizki wanted to bring a one-foot tall wooden tree, which consisted of 12 lingams, in the form of branches, from Jaipur to Kochi, for security reasons, airport authorities insisted that he had to leave the top uncovered. So, one lingam was sticking out. When it passed through the scanner at the airport, security officials hid their smirks, by turning away from Alexander.

At his exhibition, at the 'Beyond Malabar' Gallery, in Fort Kochi, the tree does stand out. “It is like the tree of life,” he says. “Through the lingam, life moves forward. But the lingam has been designed in the shape of bolsters.”

When Alexander used to look at the paintings of the Kama Sutra, he would imagine the scene without the people. “What if the cushions and the bolsters came to life,” he says. “What will they talk about?”

He says that India has a confused attitude towards the body. “On the one hand, there is an absolute acceptance of sexuality, but, on the other, there is a prudishness.”

He gives an example. “There are people who pour milk on a phallus and worship it, but if you talk to them about naked women, homosexuality or transgender issues, they get embarrassed,” says Alexander.

Meanwhile, some of the eye-catching works are the miniature paintings which adorn the walls. One such work is called 'Wish You Here'. From a distance it looks like a series of rolling green hills with a river bisecting it, all against a backdrop of poppies and tulips. But a closer look reveals interesting elements: a man is sitting sideways, on an elephant, facing the back of the animal. There is a peaceful-looking penguin standing at one side, while the Virgin Mary sits on a donkey carrying a palm tree.

In the middle of the painting is a Franciscan monk holding a large fish, which is looking skywards. At the top right-hand corner Lord Krishna, along with Arjuna, are travelling in a boat on a cloud that looks like a river. “I wanted to develop a new language in miniature painting,” says Alexander.

Interestingly, this work is part of a collaboration with the Jaipur-based master miniature painter Sheikh Riyaz Uddin Bux. “So I send him drawings, consisting of a multi-layered imagery, by e-mail, and Riyazuddin and his assistants implement it.”

Riyazuddin nods, and says, “The images of the work are sent back and forth several times, before a painting gets ready.”

And this partnership has lasted 21 years. “Our creative friendship has lasted longer than many marriages,” says Alexander, with a smile. “I think we have grown together, as adults, with a great respect and admiration for each other.”

Apart from Riyaz Uddin, Alexander has also worked with marble carvers, shoe-makers, sign painters and sculptors, among others.

Alexander has been coming to India often for the past 35 years. He has a studio in Jaipur, which he shares with Riyaz Uddin. That is why he has named his exhibition, which concludes on February 29, as ‘Pink City Studio’. “This is my homage to Jaipur,” he says.

Meanwhile, when asked about his impressions of the country, Alexander says, “In India, unlike most Western countries, life is lived on the streets. There is an astonishing vibrancy and creativity, as well as sickness, death and poverty. We have terrible poverty in America, but it is hidden. In India, you don't hide things. For example, a dead body can be seen. I believe it is better to face the totality of life head-on.”

(The New Indian Express, Kochi and Thiruvananthapuram)

Published on February 22, 2017 02:28

February 20, 2017

Protecting Their Hallowed Ground

Even as the tiny Jewish community in Kochi renovates their cemetery, there are fears that part of the sacred ground will be taken away for road expansion

Even as the tiny Jewish community in Kochi renovates their cemetery, there are fears that part of the sacred ground will be taken away for road expansionBy Shevlin Sebastian

On November 23, 2016, Josephai Abraham (Sam) stood inside the 1.5 acre Jewish cemetery on the Kathrakadavu-Pullepady road, Kochi. It was the burial of his mother-in-law Miriam Joshua, aged 89. “When I looked around, I suddenly realised that the cemetery was in bad shape,” he says. Many tombs could not be seen because of the high grass.

There were more problems. “At one corner, neighbours had thrown their garbage, in plastic packets,” says Sam, the president of the Association of Kerala Jews. “Some inhabitants had pushed their water pipes under the wall, so that all the waste water would flow into the property.”

So Sam decided to do something, with the backing of six families of the association. Workers were hired, grass and weeds were chopped off, and, at one side, where there was a marshy pond, several layers of building waste was put in, to smoothen the surface. “Thereafter, interlocking tiles have been put,” says Sam. “At least, now, we can park our cars inside. Otherwise, we had to do so on the narrow road and it created problems for the other motorists.”

The walls have been painted white and many tombs, which were broken, have been repaired and repainted. And, on the wall, at the opposite end to the entrance, two Star of Davids have been etched, along with the seven candles of the Menorah. The Menorah has been a symbol of Judaism, from ancient times, and is now part of the emblem of the state of Israel.

However, it has not been smooth sailing. One neighbor approached Sam and told him he could not do any renovation, as all construction has been frozen. On being asked how, the neighbor said there are expansion plans for the road and the cemetery will be taken over. “I said no such decision has been taken,” says Sam.

Then, in mid-January, Gracy Joseph, Chairperson, Standing Committee for Development of the Cochin Corporation, came to inquire. “I had received complaints from the local residents that some construction was going on,” she says. “But the members of the Jewish community told me that they were only renovating the place.”

Clearly, the cemetery is under threat. “The Cochin Corporation has plans to broaden the road,” says Association secretary Dr. Susy Elias. But Soumini Jain, the Mayor of the Corporation says that the stretch in front of the cemetery has been handed over to the Public Works Department of the State government. “It is they who will do the road expansion works,” she says. “There are suggestions of building an overbridge, in front of the cemetery. But whether the government has the funds for that, I am not sure.”

Meanwhile, according to Jewish religious law, once a person is buried, the grave cannot be disturbed. It can only be removed if a relative gives permission. But the local Jews have no idea where they are, since many have emigrated to Israel several years ago. So, the Jews are anxious about whether the authorities will insist that they will have to give up a part of their cemetery. “Many tombs will be disturbed,” says Sam.

Sometime ago, the association got in touch with Israeli ambassador Daniel Carmon. Thereafter, last month, the Bengaluru-based Israeli Counsel General Yael Hashavit met Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan and appraised him of the situation. “The CM said that he was aware of it,” says Mordokkayi Shafeer, the treasurer of the association.

Meanwhile, despite these tensions, the Jews come once a month to light candles and to pray at the graves. “We also come on death anniversaries and during the Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) festival,” says Shafeer. “Life has to go on.”

(The New Indian Express, Kerala editions)

Published on February 20, 2017 22:34

Telling Ancient Tales

Mural artist PK Sadanandan's work is one of the more eye-catching ones at the Kochi Muziris Biennale

Mural artist PK Sadanandan's work is one of the more eye-catching ones at the Kochi Muziris BiennalePhoto by Albin Mathew

By Shevlin Sebastian

When Yesomi Umolu, Exhibitions Curator of the Reva and David Logan Centre for the Arts, at Chicago, stepped into a large hall, at Aspinwall House, Fort Kochi, recently, her eyes widened in shock. Then, as she turned her head from one side to the other, she said simply, “This is impressive.”

So impressive that even Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan stopped and spent a few minutes with the artist PK Sadanandan. The work, titled '12 Stories (of the 12 Progeny)' is an ongoing mural art work, 50 ft wide and 10 ¼ ft high.

It tells the stories from the 'Parayi Petta Panthiru Kulam', a Kerala legend, of the 12 kulams (families born to the Parayi, or women of the 'pariah' caste). Here is one story. “Varaduji is a Brahmin scholar,” says Sadanandan. “On a pilgrimage, he stopped near the banks of the Bharatapuzha river, in Kerala, saw a house, and decided to rest there.”

There he came across a smart girl and decided to marry her. But it was after a while he realised that she is not a Brahmin, but a Parayi. When word got around, he was expelled from society.

Of course, there is an underlying message in the many stories which have been depicted. “Too much of attention is being given to caste and religion,” says Sadanandan. “Once we had a society where both these issues were not that important. I also speak about the relevance of fate, the inequality of the caste system, and the role of family and society.”

Sadanandan is one of the leading proponents of Kerala mural art. “I learnt everything at the feet of my guru Mammiyur Krishnan Kutty Nair from Guruvayur,” he says.

One of the unusual aspects of his work is that he uses natural colours. So the colour yellow is got by scraping an arsenic stone brought from Afghanistan. For black, an oil lamp is placed under a clay pot for a week. The ensuing soot is again scraped away, and mixed with water, to create a black paste. As for glue it is from the neem tree.

And all these colours are applied several times. “My assistants – Anish A.K., Joby John, Anish Kuttan – and I start work at 8 a.m. and work till 9 p.m,” says Sadanandan. “It will be completed by the end of the 108-day Biennale.”

And the reason for this painstaking work is simple: it is the only way to ensure that the work will last for centuries. “The paintings at Ajanta and Ellora have lasted for so long because the artistes have used natural colours,” says Sadanandan.

Meanwhile, as visitors stream in, there is a palpable excitement on Sadanandan's face. “For the past 30 years I have been practising this art,” he says. “But I have never got an opportunity to present my work before the international art community. I feel so lucky. I am grateful to curator Sudarshan Shetty for inviting me.”

(Sunday Magazine, The New Indian Express, South India and Delhi)

Published on February 20, 2017 00:17

February 14, 2017

Lights, Camera, 'Hallelujah'

COLUMN: LOCATION DIARY

COLUMN: LOCATION DIARYProducer Vinod Shornur talks about his experiences in the films, 'Achanuragantha Veedu', 'Spanish Masala', and 'Red Wine'

Photos: Vinod Shornur by Albin Mathew. Mohanlal with Safi

By Shevlin Sebastian

During the shoot of 'Achanuragantha Veedu' (2006), at Peermade, an actor, by the name of DC Nair, played the role of a pastor. For the song, 'Zion Manavalan', he was supposed to raise his hands and say, “Hallelujah.”

No matter how many takes were taken, Nair just could not say 'Hallelujah'.“He could say it in rehearsals, but when the shot had to be taken, he could not speak the word,” says then production-controller Vinod Shornur. “Nair said that when he heard the word, 'Action', he felt a great tension within himself.”

So, at the suggestion of a crew member, director Lal Jose said that, instead of the word, 'Action', he would say, 'Hallelujah'. The song was played, and then Lal Jose shouted, “Hallelujah,” and immediately Nair said, “Action.” The crew members, along with the director, burst out laughing.

But on August 31, 2011, the crew of the Mollywood film, 'Spanish Masala', felt very tense. They were in the town of Bunol, 324 kms from Madrid. A shoot was going to be held, during the world-famous 'La Tomatino' festival, where revellers would throw ripe tomatoes at each other.

In the film scene, Kunchacko Boban was supposed to have fun with Austrian actress, Daniela Zacherl, who plays a Spanish diplomat's daughter. “We had put the cameras at four vantage points much earlier,” says Vinod. “At one location, Lal Jose Sir and [cinematographer] L. Lokanathan were waiting.”

There was so much of shouting and jostling that the crew were not able to communicate with each other. Along with a lady Spanish co-ordinator, by the name of Maria, Vinod was supposed to take Daniela to where Kunchacko was waiting. However, in the crowd, they lost touch with each other. But only Maria knew the correct location.

Nevertheless, Vinod kept his cool. “I knew that we would not get another chance like this,” says Vinod. “This festival takes place, for two hours, on this one day of the year. Somehow, I held Daniela's hand, moved forward and, after much struggle, by accident, I reached the spot where Kunchacko was waiting.”

After the shoot was over, Maria finally spotted Vinod. But she looked downcast. “She thought that the shoot had not taken place,” says Vinod. “But her colleague told her in Spanish that everything had worked out well. And she looked so relieved that she gave me a bright smile.”

There were bright smiles, too, on the sets of 'Red Wine' at Kozhikode During the shoot, at a lodge, just behind the reception desk, an advertisement to cure body ailments was put up, by the unit's art department, along with a mobile number. This belonged to Shafi, who was a member of the crew. But he did not know about it.

From the early morning, the crew members called Shafi, from other phones, asking whether he was a doctor. “I could hear him say that it is a wrong number,” says Vinod. “This went on throughout the day. Once I saw him getting angry asking the caller to check the number before calling.”

Soon, Mohanlal came to the set. When he came to know of the prank, he also called Shafi. Mohanlal changed his voice and said that his wife was unwell. Since the number came as 'Private number, not identified', Shafi thought it was an international call. “He came and told me that people were calling him from abroad,” says Vinod. “By this time, he was so distracted, he could not work properly.”

So, finally, it was Mohanlal who revealed the prank to Shafi and the crew had a big laugh once again.

(The New Indian Express, Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kozhikode)

Published on February 14, 2017 20:01

February 13, 2017

Crossed 10 lakh visitors

Dear Friends,

Dear Friends,Through the grace of God Almighty, have reached a milestone.

My blog, 'Shevlin's World', has received over 10 lakh visitors.

Grateful thanks to each and every one of you who visited, to my former and present seniors and colleagues, and the management of The New Indian Express, and my family.

Shevlin

Published on February 13, 2017 01:08

February 10, 2017

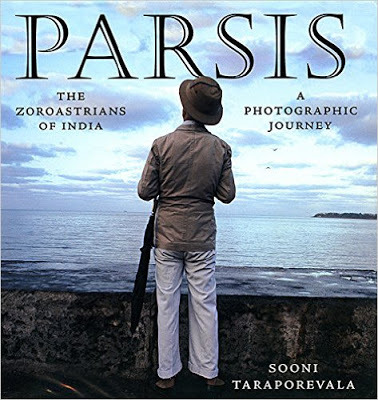

Why Did God Make His Life So Difficult?

(Reminiscences of my Parsi neighbour)

(Reminiscences of my Parsi neighbour)A few years later, Sona got a job, and moved off to Singapore. Navroz felt deeply disappointed.

Navroz climbed on to the parapet, stood undecided for a few moments, and then he jumped. Thankfully, for him, a branch of a tree broke his fall, before he landed on the pavement. Thereafter, he was rushed to the hospital, and, although he survived, his lower back was damaged. He always wore a brace after that.

Is his father alive? If not, how is Navroz managing? Why did God give him such a difficult life? He was a nice human being, always polite and well-mannered. But he was helpless against the hallucinations that ravaged his mind.

Hope you are keeping well, Navroz.

(Published as a middle in The New Indian Express, South India Editions)

Published on February 10, 2017 21:45