Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 50

September 24, 2018

The Kaleidoscope Called Village Life

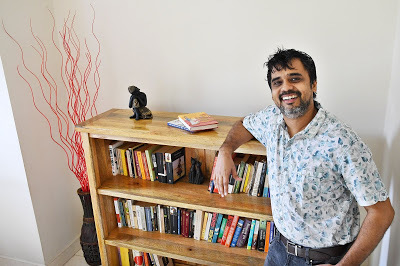

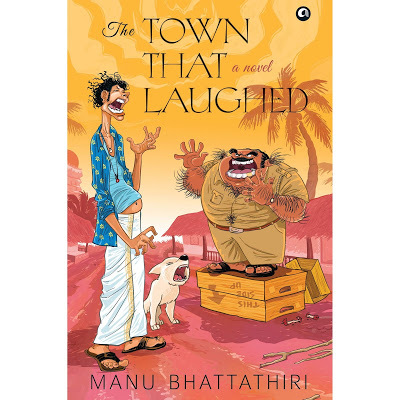

Advertising professional Manu Bhattathiri’s debut novel, ‘The Town That Laughed’ focuses on the fictional village of Karuthupuzha in Kerala

By Shevlin Sebastian

On most days, when he was writing 'The Town That Laughed' (Aleph Book Company), Manu Bhattathiri would awaken with images of the fictional village of Karuthupuzha in Kerala. He would get up, get ready and go for a walk and mull over what he was going to write. Then, at 7.30 a.m. the Bangalore-based author would sit at his desk and write for exactly one hour. “I deliberately did not do more,” he says. “When you stretch it a bit, the sweat shows.”

Eight months later, the 254-page novel was done. And it is a highly engaging one. Written in a relaxed style, Manu, with deft sentences, is able to bring the characters alive and cast a spell on the reader.

These are people, many of them eccentric, who inhabit most small towns and villages in India. In 'The Town', there is the local drunk, Joby, and the just-retired Inspector Paachu Yemaan, who is bleakly suffering the loss of power and prestige, Paachu's long-suffering but inwardly strong wife Sharada, the barber Sureshan, the local cops, Inspector Janardhanan and Constable Chandy, Joby's wife Rosykutty, the love affair between Kannan Maash and Ambili Teacher, among many other interesting people. It is an affectionate and humourous portrait of human beings and their foibles.

But village life is an unusual subject for Manu since he grew up in North India, in places like Boleng in Arunachal Pradesh, Tezpur in Assam, and Udhampur in Jammu and Kashmir. His father worked in the Border Roads Organisation, which builds roads for the Army.

But once every two years, the family would spend the summer vacation at Manu's maternal grandfather's village of Cherupoika in Kollam district, Kerala. “There was an aura to the village as far as I was concerned,” says Manu. “It was so different from our life in the north.”

As a boy, Manu was enamoured of the village folk, and the beauty of Nature. “There were a lot of paddy fields around, a small river, and dense foliage all around,” he says. “You could always get a fresh smell.”

And to top that, his grandfather, M N Vasudevan Bhattathiri, a Sanskrit teacher, was a fount of stories. “They were usually tales from the Mahabharat and Ramayana,” he says. “But it is not that I have been told the stories in exactly the way I have heard it. Instead, I mixed my memories with my imagination and produced some original characters.”

Incidentally, this is Manu's second book. His first book, 'Savithri's Special Room And Other Stories' also dipped into the memories of Cherupoika. And it was well received both by readers and critics. In fact, the book was short-listed for the Crossword Book Award (Fiction) for 2018 and was on the long list of the Tata Literature Live Award for 2016.

In his daily life, Manu runs an advertising firm, ‘Cheers Communications’ with a partner Sudhir PR. But he has regrets regarding his career. “In advertising, your desire to write is falsely fulfilled,” says Manu. “You are only writing headlines and body copy. It set me back by 15 years.”

Asked whether he has more books inside him, Manu smiles and says, “I have a library inside me. If I keep my focus and interest levels, I could write many books. But the publicity that is given to books and authors is a bit disappointing these days.”

Not to forget the intense distraction of readers because of the mobile phone. “I agree,” says Manu. “People read five pages of a book and then they decide that they now need to check their mobile phones. Because of screen addiction, there is a persistent need to look at the mobile, laptop, television or the cinema screen. We need to do something about it. Otherwise, we will become shallow and superficial.”

(Sunday Magazine, The New Indian Express, South India and Delhi)

Published on September 24, 2018 22:44

September 23, 2018

From Bangkok, With Love

Panyawut Kupan, the most famous blind footballer in Thailand, talks about his life and his experiences of playing with Indian players at Kochi

By Shevlin Sebastian

It is a cloudy morning at a football ground in Kochi. A few players step out onto the turf. Among them is Panyawut Kupan, a player from Thailand. Soon, he takes the red and white striped ball and begins to play with it, using his feet. Sometimes, he takes it forward, then backwards, then sideways, left to right, right to left, then he does a back pass, and collects it with the other foot. It was mesmerising. What made this performance so amazing is because the 24-year-old is completely blind. So, he is controlling the ball through feeling and intuition.

“I developed this skill by training for hundreds of hours,” he says. “The ball has to remain stuck to your foot even when you move. Otherwise, you will lose control of it. So you have to develop a feel for the ball.”

Panyawut had come to Kochi recently, with Kong, the captain of Thailand's national football team, coaches Surin Sungsiri and Chaiyaporn Sanidwong, and Tim Suphankomut, the director of the Sports Association for the Blind of Thailand. “The aim was to give exposure to the Indian team as well as gain some experience for ourselves,” says Tim.

The sessions, spread over three days, went off well. And Panyawut was impressed by the Indian players. “They played with dedication and sincerity,” he says. “During a morning training session, one player started bleeding on the forehead because he banged his head against another player. But after putting on a bandage, he was back on the field.”

But Panyawat is honest, too. “India is a newcomer to blind football, so the players may not have the skill level yet to compete at the highest level, but they have the heart,” he says. “The best thing about India is that there is so much talent. But they need to play together more so that they can feel they are all part of a team.”

Adds national coach Sunil Mathew, “The aim of holding a joint training session is to help develop the skills of the Indian team. Currently we are ranked 29th in the world.”

Meanwhile, on his first visit, Panyawat liked Kochi. “It is very similar to the southern part of Thailand, like Surat Thani and Phuket,” says the Bangkok-based player. “We also have the same trees and greenery. Food-wise, both of us eat a lot of rice, and fish and curry meals.”

And although he radiates energy and focus, he admits it has been a tough journey. Punyawat began to lose his eyesight when he was six years old. “I remember how my mother would cry whenever we would go to the hospital,” he says. By the time he was 16, Punyawat was completely blind. It was only then that he became eligible to play blind football. But he does not want to dwell on his blindness. “I want to be a good player and citizen, and not be a burden on society,” says Punyawat, who is a travel guide for the SNP Group of Companies.

And today, he is the most famous blind footballer in Thailand now. “In the past two years, Punyawat has played five tournaments in Singapore, South Korea and Malaysia, and also took part in the World Blind football championships in Madrid (June 7-17), where he scored five goals.” In the end, Thailand came 12th out of 16 nations.

Thanks to his achievements, his parents and his two sisters are happy. “Playing football has changed my life,” he says. “Many people know me. So, I don't want to let them down. I want to become a better player so that I can help Thailand do well in international tournaments.”

(Sunday Magazine, The New Indian Express, South India and Delhi)

Published on September 23, 2018 23:15

September 22, 2018

Eat Right To Feel Happy

Australian dietician Michele Walton, on a recent visit to Kochi, talks about the ways to enjoy food without becoming overweight. She also spoke about the charms of Kerala cuisine

By Shevlin Sebastian

Sometime ago, the Australian dietician Michele Walton went to the hill station of Coonoor with her husband Darren. They were walking down a road admiring the tea gardens on both sides. Suddenly, they saw a man standing on one side. Darren went to speak to him. The man's name was Akbar Ali. He told Darren that he was getting ready to celebrate Id.Akbar immediately said, “You must come to my house. My wife is cooking biriyani.”

Even though they were taken back, Michele said, “Okay, it sounds good.”

So Akbar took them on his motorbike, one by one, to his home in a village.

“And we enjoyed a biriyani meal in an Indian family home,” says Michele. “The generosity and kindness were lovely. And that is why we keep coming back to India all the time. This warm hospitality cannot be seen anywhere else. So, we encourage people from Australia to come to India to enjoy the food as well as the ambience.”

Recently, Michele came to Kochi to give a talk at a seminar conducted by Nutrisolutions, owned by her friend Gayathri Asokan. “I spoke about how India and Australia face similar challenges,” she says. “In both countries, there is a lot of good food now and we have more money to spend on it. And since most of us are in sedentary occupations and do very little physical exercise, we tend to put on a lot of weight.”

Michele also gave tips on how to eat food that you like but in moderation. “In effect, I said that if you love chocolate you should have it, instead of staying away from it. But the trick is to have it in moderation.”

So how do you do that? “We tend to eat our food fast,” she says. “If you eat slowly and mindfully, then you will enjoy it more and eat less. It takes your tummy about twenty minutes to catch up to what you are eating. By eating slowly, you can give the chance for it to tell you that it is getting full. Another method is to have a sip of water in between bites. That can slow you down.”

But Michele has not slowed down when it comes to Kerala cuisine. “From a dietician's perspective, the Kerala dishes are easy to make, but I make small adjustments to suit the Australian palate,” she says. “In Kerala, people love the flavour of the coconut oil but for us, we are not used to it yet.”

She also makes the fish moilee because it is not too spicy. But her favourites are the appams and puttu. “When you dip the appam in a bit of coconut milk, it is heavenly,” says Michele. “I also love the texture and flavour of puttu. It is less oily as compared to other breakfast dishes. It is a good meal to have at the beginning of the day.”

Michele has also enjoyed the cuisine of places like Goa, Rajasthan and Bengal. “In Kolkata, they use a lot of mustard oil,” she says. “So, the flavour and styles are different. But I loved the misthi doi, sandesh and rosagullas. There was the Nolen Gurer ice cream made with jaggery palm syrup which was amazing.”

And then Michele added, with a smile, “But it was a calorie killer. So I had to eat it in small amounts.” In Mumbai, she enjoyed the vada pav and pani puri, while in Goa Michele enjoyed the vindaloo and pork dishes.

“Each cuisine is so different and special,” says Michele. “In fact, each state is like a different country. But the food is an interesting way to know the history and the culture of a particular place. Interestingly, I did notice how the North uses more bread, while the South prefers rice.”

Asked about the ideal diet, Michele says, “80 per cent should be fresh fruits, vegetables, lean meat, seafood, fish, wholegrain bread, cereals and dairy items,” she says. “It is better to avoid cakes and chips, as they tend to be high in salt, oil and sugar. If we have them, it should be in very small amounts.”

Michele says it is important to eat the right food in the correct amounts. Otherwise, you end up becoming overweight. And you will have to pay a heavy price. “When you are overweight, you immediately put yourself at risk to obesity-related ailments,” says Michele. “These include back pain, joint problems, heart disease, and painful knees, apart from diabetes. Eat right and live happily is my mantra.”

(The New Indian Express, Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kozhikode)

Published on September 22, 2018 04:09

September 17, 2018

When The Sun Sets

(Memories of Mollywood actor Captain Raju who died on September 17)

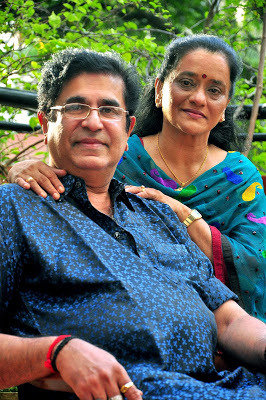

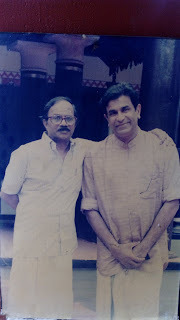

Photos: Captain Raju with his wife Premila. Photo by TP Sooraj. Captain Raju (right) with Jnanpith Award winner MT Vasudevan Nair

By Shevlin Sebastian

The first thing I noticed when I met Captain Raju at his first floor home at Padivattom, Kochi a couple of years ago was how tall he was. At 6'2” and with large, broad shoulders, he looked towering. The second quality was his wide smile. He was so welcoming and gracious. And like a true host, there was a spread, set up by his wife Premila: halwa, a Gujarati dish, chips, pickle, and a cup of coffee. “First eat and then you can do the interview,” said Capt. Raju.

Later, hobbling a bit, he took me out to the spacious balcony. There was a large overhanging tree nearby. The leaves rustled; the sparrows chirped, and the wind blew a little. From the distance, there was the sound of traffic.

“My leg is giving me pain,” he said. “I am getting it massaged daily.”

And it was sad that Capt. Raju was still suffering the effects of what happened on the night of October 12, 2003. He was travelling in a car, with a driver and an assistant, from Thiruvananthapuram to Salem to take part in the shooting of Vinayan’s ‘War and Love’. Just after Thrissur, the car hit a culvert, went over the wall, and fell 40 feet. “There was no tree to stop the vehicle,” says Capt. Raju. “So, the car had another fall of 100 feet.”

Capt. Raju had multiple fractures on his legs, damaged his ribs, and had a head injury. A few months later, he suffered a stroke which numbed the left side of his body. It was only after months of physiotherapy that he recovered. But things were never the same again.

Nevertheless, he has acted in over 500 Malayalam films – Tamil, Telugu, Kannada and Malayalam. And he has so many memories of his career but those at the beginning are always the most memorable for any actor.

In the film, ‘Raktam’ (1981), Capt. Raju had a fight sequence with Madhu at the Rama Varma club at Kochi. The crew had placed small sheets of wood (the pattika) of an old house on the floor. As Madhu hit Capt. Raju, with a shovel, the latter fell on the wood.

Mollyood legends Prem Nazir, Soman and Srividya were watching silently.

Once the shot was over, Prem Nazir said, “Capt. Raju, please come here.”

When the actor went close, Prem Nazir said, “Captain, look carefully at the wood. There are numerous nails sticking out. I understand your anxiety to do well. This is your first film. But you have to be careful. If you fall and a nail enters you, especially if it is your face, then what will happen? Director Joshy will say, ‘Pack up’. Then you will have to be taken to the hospital to be given a tetanus injection because the nails are rusted. And your career might come to a stop before it has started.”

A moved Capt. Raju said, “Which superstar will tell something like this to a newcomer? I have never forgotten it. Prem Nazir Sir was a star with so much of humanity.”

And so was Captain Raju.

We will miss you Sir!

(The New Indian Express, Kochi and Thiruvananthapuram)

Published on September 17, 2018 23:46

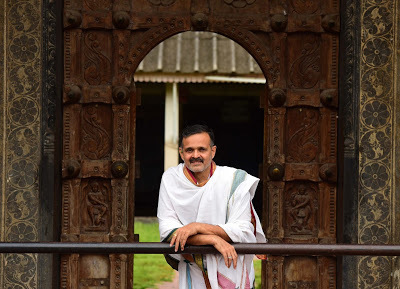

Preserving A Community’s Religious And Artistic Heritage

L. Krishna Bhat, of the Gowda Saraswat Brahmin community, at Mattancherry, Kochi has written and produced 45 plays, as well as penned the lyrics of 300 songs. He is also the head priest of the Cochin Thirumala Devaswom temple

Photos: L. Krishna Bhat standing in front of the Cochin Thirumala Devaswom temple at Mattancherry; playing a mythological hero

By Shevlin Sebastian

It is midnight. L. Krishna Bhat is sitting at a table in his house at Mattancherry. In the deep silence all around, there is only one sound that can be heard: the scratch of a pen’s nib on paper.

Bhat is writing a play. Characters, dialogues and scenes swim around in his imagination. Time passes. Suddenly, he yawns. Then he looks at his watch. It is 12.30 a.m. Reluctantly he closes the notebook, puts the cap on his pen and retires for the night.

But within four-and-a-half hours, the playwright awakens.

Following his morning ablutions, Bhat heads for the 400-year-old Cochin Thirumala Devaswom temple nearby. He has been the head priest for decades. He sits cross-legged on the floor and starts the puja rituals by 5.30 a.m. in front of an idol of Lord Venkateswara.

Around 300 devotees listen raptly to the prayers even though it is a weekday morning.After a while, many leave. But devotees keep coming and going. Bhat remains at the temple till noon. Then he leaves for his home. Following lunch, the reading of the newspapers and watching the TV news, Bhat has a nap. Then by 5.30 p.m., he is back at the temple and says prayers till 10 p.m.

But Bhat is a priest with a difference. He is a short-story writer, a lyricist, an actor, a director of plays as well as a dramatist. So far, he has written, acted and directed 45 plays, mostly on mythological themes from the Puranas.

And they are popular. Says Ramesh Pai, the former chairperson of the Konkani Sahitya Akademi, Kerala: “Bhat’s plays have been written in such an engaging manner that audiences always look forward to the next production.”

So, single-handedly, Bhat is keeping alive the culture of the small Konkani community in Kochi. “At this moment, there are about 18,000 Konkanis in Kochi,” he says. The majority are members of the Gowda Saraswat Brahmin (GSB) community.

Many of the GSBs fled Goa in 1560 AD because they faced religious persecution by the Portuguese. They came to Kochi, which was an important trade and commercial centre at that time. The Brahmins pleaded with King Veera Kerala Varma of the Cochin kingdom, who, in a humanitarian gesture, gave them refuge as well as a large tract of land behind his palace in Mattancherry for them to stay. “We have been living here ever since,” says Bhatt.

Incidentally, Bhat is a tenth-generation priest. His son, Jayadev, 21, will take over the mantle, once Bhat grows old or becomes incapacitated. “He is receiving training,” says Bhat. At the same time, Jayadev is specialising in graphics and art design.

Meanwhile, when asked about how he got interested in art, Bhat says that one of his neighbours, VV Naik, would enact a lot of plays. “Somehow, as a child, I began going to his house,” he says. “Soon, I began acting. Thereafter Naik Sir told me to write plays. I began doing so. I also wrote songs. So far, I have written the lyrics of 300 songs.”

These are mostly devotional as well as lullabies for children. In fact, one lullaby, ‘Rama Bala Jo Krishna Bala’ has been picturised and it can be seen on YouTube. In it, Bhat plays a writer as well as a doting father.

What Bhat is doing is unusual. For centuries, the GSB community had stayed away from art and culture. “They would make others do the performing and enjoyed watching it,” says Bhatt. “As Brahmins, we were not encouraged to sing, play an instrument, or go on stage. The change came only a few decades ago.”

So, when Bhat expressed his desire to write and act in plays, his parents did not object at all. “They only said that whatever work I produced it should bring people together,” says the 58-year-old. At this moment the drama troupe consists of 35 people, comprising professionals like doctors, corporate managers and dancers.

Asked about his future plans, Bhat says, “I want to continue to do plays that will enrich our heritage and also ensure that digital videos are made so that the culture is preserved for future generations.”

(Sunday Magazine, The New Indian Express, South India and Delhi)

Published on September 17, 2018 05:22

September 15, 2018

A Malayali In Tasmania Gets A Rs 75 Lakh Australian Grant to help Dairy Farmers in Kerala

By Shevlin Sebastian

Last week, when Anoop Thankan, project manager of Green Grass Dairy in Cressy, Tasmania, was wandering between the cows in a grassy area, suddenly he heard the 'ping' sound on his smartphone. When he looked he saw that it was an email from the Australia-India Council. When Anoop read the mail, he let out a whoop of joy.

Thanks to his presentation, the Council had just given the company a $150,000 (Rs 75 lakh) grant to help bring Australian farming expertise to dairy farmers in Kerala.

On his annual visits to his home at Kottapaddy, near Kothamangalam, Anoop observed that the dairy farmers were decades behind. “They used outmoded methods of production and feeding,” says Anoop, who looks after 3000 cows.

He says 60 per cent of the daily feed should consist of different varieties of grass. Another 30 per cent should be proteins and mineral-rich legumes and shrubs such as moringa, hibiscus and mulberry leaves. “For the remaining 10 percent, they can have tubers like jackfruit and tapioca, or grains like wheat, barley or maize,” he says.

Anoop and Green Grass director George Rigney are planning to hold one-day workshops in Kasaragod, Wayanad, Kothamangalam, Chengannur and Thiruvananthapuram next month. The topics that will be discussed include farm management, forage production, soil management, animal health and infrastructure design.

Of course, since Anoop is in 17 Whatsapp groups of Kerala dairy farmers, he knows about the devastation caused by the recent floods. “Many farmers in Idukki, Wayanad, Pathanamthitta and Ernakulam have told me they have lost all their livestock,” he says. “A few farmers have got back some of the cows but all the grass has been destroyed. Some farmers have lost their sheds and other buildings. We are trying to figure out how we can help.”

In the meantime, work is going on to develop a Green Grass App in Malayalam and English. “Farmers in Kerala will be able to access Australian videos and modules. They can also ask questions which will be answered,” says Anoop.

He pauses and says, “I just want to do my bit for my homeland.”

(Page I, The New Indian Express, Kerala editions)

Published on September 15, 2018 20:33

Life On The Cutting Edge

Pallavi Singh's recent exhibition, 'Haircut Museum (Under Construction)' focuses on the lives of barbers in and around Fort Kochi, Kochangadi, Jew Town and Mattancherry areas

Photo: Melton Antony

By Shevlin Sebastian

Stepping into a hall of the Pepper House, Fort Kochi, on a sunny afternoon was like stepping into a dark cavern. The warm lights were muted; there were thick black drapes on the windows, which were closed. Added to that, there was a heavy silence. It almost felt as if time had stopped inside the room. Artist Pallavi Singh smiled and says, “I wanted to make it look like a museum.” Not surprisingly, her exhibition on barbers is called, 'Haircut Museum (Under Construction)'.

As she spoke, through a tiny gap in the curtain she saw an elderly man step into the entrance of Pepper House. Her mouth opened ever so slightly. That was Shamsudheen, the oldest barber in the Fort Kochi, Kochangadi, Jew Town and Mattancherry areas of Kochi.

“He looks nervous,” whispered Pallavi, as the silver-haired Shamsudheen, wearing a blue shirt and white dhoti, came forward with hesitating steps. “This must be the first time he is coming for an art exhibition. This community is so far away from art.”

When Shamsudheen stepped into the darkened room, he noticed the old barber's wooden chair. He immediately went and sat on it and looked pensively at the mirror in front. “Shamsudheen is a fourth-generation barber,” says Pallavi. “His son is in another profession. So, after he dies, the shop will close down. He feels sad about it.”

Soon, Shamsudheen got up and went and caressed the combs, trimmers, scissors, shaving brushes, creams, bowls, razors, blades and hair gels which have been placed on the top of square and rectangular boxes. Under each item, Pallavi has pasted the name of the item and the barber who donated it. So, 'Power Brush' has been donated by Nawab of the Belleza Gents Beauty Saloon, while 'Hair Styler – Gatsby' has been given by Thajudheen, Beauty Care.

At one corner, there were photo albums which traced the lives of these barbers accompanied by several photos. In Ramzan's life story, he says, 'This is not my family business. I learned the art of hair cutting for my survival and now it has become my profession.”

Pallavi has focussed on the life of nine barbers. But they were not very welcoming in the beginning. “I can't blame them, because I am from Delhi,” says Pallavi. “And I am a woman. Plus, I could not speak Malayalam.”

But Pallavi went regularly and made small talk through an interpreter. She explained about her two-month long project based on a residency given by the Kochi Biennale. Slowly and steadily, they started opening up.

And she heard some interesting stories. One of them was about Shivan Thakur, who was a farmer in Jharkhand. He works in the Lucky Men's Parlour in Jew Town. He came to Kochi to meet a distant relative and accidentally met the saloon's owner Ramzan. “We clicked,” says Shivan. “When Ramzan invited me to join the saloon, I agreed. But it took me a while to learn and understand Malayalam.” While Shivan stays in Kochi his wife and family remain in Jharkhand.

As for Nawaz Yusuf, 45, he runs the Bombay Saloon. He has five brothers. Soon, they split up. Now, there are two more Bombay Saloons in the same area. “But Nawaz had a look of pride when he said that his son is a sailor,” says Pallavi.

As she conversed with the barbers, she realised that all of them loved the profession. “It is a passion,” she says. “They told me that when a customer presents his head to them, they have the responsibility to do the perfect cut. They said that by just looking at a face, they know the type of haircut that will suit the person.”

Nowadays, more and more young barbers have come into the profession in the area. But when Pallavi asked Shamsuddin whether he felt nervous, he said, “Not at all. I have a loyal customer base and they will always remain with me.”

Not surprisingly, the new barbers have youngsters as their customers. The Mohawk and the Pompadour styles are the most popular styles. Many of the youngsters have been influenced by the haircuts of international footballers that they see on TV.

And the barbers received a never-ending stream of customers on the night before Id, which took place on June 14. “They worked till 1 am,” says Pallavi. “And they did all sorts of styles. I was surprised at the interest that the youngsters showed in grooming.”

Meanwhile, when asked about the reaction of visitors to her exhibition, Pallavi says, “Many told me it reminded them of their childhood and how their fathers would take them to the local barber. They were able to relate to the scissors and combs. Some said the old radio [which had been placed on a window sill], reminded them of the songs they heard at that time. They would sit on a small stool placed on the seat of the chair and get their hair cut.”

It has been an interesting two months for Pallavi. “I got to interact with a community whom I knew nothing at all,” she says. “So, it was an eye-opener.”

(The New Indian Express, Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kozhikode)

Published on September 15, 2018 00:09

September 11, 2018

When The Animals Were Swept Away

Owner Babu Manjally shares his experiences of how the recent floods in Kerala led to the deaths of more than 400 animals on his farm

Photos: The carcass of the animals; Owner Babu Manjally stands in the shed where there were 37 cows. Pics by Shevlin Sebastian

By Shevlin Sebastian

Babu Manjally stood at the cowshed and saw that the water had reached the necks of the animals. It was raining heavily. A fierce wind was blowing. The trees were swaying dangerously. By this time, the sparrows and crows had flown away to higher areas.The 37 cows let out fearful cries and their ears became pricked up. “This happens to all animals when they are very scared,” says Babu.

He decided to cut the ropes around their necks. Because the ropes were wet, it was not an easy thing to do. But time was running out. He looked behind him. In another shed, 300 pigs were grunting wildly. He told his younger brother Mathew to open the doors of the different cages. Meanwhile, 60 goats were bleating along with 11 buffaloes.

Babu’s farm at Ayroor (40 kms from Kochi) is located between the Chalakudy river in the north and the Periyar in the south. As the five shutters of the Idukki Dam were opened on August 9, water began gushing down the rivers.

On August 11, Babu went to the banks of the Periyar, at Aluva, which is 14 kms away to study the level of the water. “I felt there was not much of a problem,” says Babu. But in the succeeding days, the water level rose and rose. And suddenly it became too late to shift the animals elsewhere.

Meanwhile, the freed cows jumped into the water. They swam for a distance, but there was no solid ground anywhere for them to stand. “After a while, they returned to the shed,” says Babu. “The other cows did the same. The water was very cold and the current was fierce. It was heart-breaking. I felt so helpless.”

Mathew said, “Chetta, let’s go. If we stay here any longer, we will have a heart attack.”

So Babu looked at the cows. “They knew they were facing death,” he says. “And they also knew I could not do anything. The look they gave me was one of simply saying goodbye.”

Babu and Mathew climbed on to their canoe and paddled the way back to their house, which was 2 kms away. There, they faced another crisis: the water was rapidly entering the ground floor.

Back in the farm, all the animals were swept away as the water rose to a height of 12 feet.A few days later, when the rain and the floodwaters receded, an astonishing sight greeted Babu. All over his one-and-a-half-acre farm, there were dead cows, goats, buffaloes and pigs. “They were not able to go very far,” he says.

But there was a tiny heart-warming story. “Four pigs got stuck on top of a large haystack and managed to survive. I was able to bring them back,” he says.

As the days went by, Babu began to bury the animals in six-foot pits on the farm and covered it with mud. But the job is yet to be completed. On a recent visit, one could see the carcass of several cows, amidst a couple of skeletons. The stench was unbearable. “Look at their state,” says Babu. “They were so healthy once.”

The sun has been beating down for the past few days. In an astonishing turnaround, the farm looks baked now. There are cracks in the dried mud, and it is difficult to believe that just a few days ago, there was such a large volume of water in the area. But the sheds lie ravaged. Broken cauldrons, torn plastic sheets, silt all over, while tiled roofs and walls had all crashed to the ground. A coconut tree lay fallen to one side, its roots exposed.

A pained Babu says, “My losses amount to Rs 60 lakh. Last year, I had taken a loan from the bank. I will be a defaulter soon.”

There was more heartbreak. A group of men came to the farm one evening when Babu was not around. They grabbed one of the pigs and took it away. People saw them. They identified them as local youths, high on drugs and alcohol. They ended up killing the pig and eating it. Babu has filed an FIR at the local police station.

He is rightfully angry because animals have been a passion for Babu. He grew to love them deeply. “They have a pure heart,” he says. Babu would come to the farm at 6 am and return only at 11 pm. He would help the workers to clean the sheds, oversee the feeding and the milking, and get the animals washed too.

It was not long before his wife would complain to visitors, “Babu is always at the farm.”Not surprisingly, Babu began to understand their language. “The moment I would come to the farm, they would make greeting sounds,” says Babu. “And when the feed time came, all of them would stand up. The pigs went, ‘Krank, krank’, the cows would bang their horns against the poles they were tied to. They were saying, ‘Give us the feed, give us the feed’. The goats nuzzled their noses against my legs.”

And Babu gives an interesting insight. “If you talk to them, they will stand still and stare at you pretending that they understand what you are saying,” says the farmer. “It used to make me laugh at times.”

But he knows that their sudden and unexpected deaths have left a permanent scar in his heart. “In the end, I was their parent,” says Babu, the father of two teenage boys. “You can imagine how painful it is for a parent to lose his children.”But Babu has plans to restart his farm. He is turning to some of his well-off friends and animal lovers for financial assistance. “I will start by buying baby pigs from Mysore and calves from Tamil Nadu,” says Babu. “My 84-year-old father told me there will be setbacks in life but we need to move forward.”

(Published in The New Indian Express, Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kozhikode)

Published on September 11, 2018 22:51

September 9, 2018

Overwhelmed By Cruelty To Animals, She Turns Vegan

By Shevlin Sebastian

Sometime ago, the Kochi-based yoga coach Sudakshna Thampi joined a group which rescued street dogs which had been hit by cars or were deliberately beaten or tortured. There were cases where people were planning to poison dogs or dump their puppies to get rid of them.

Soon, Sudakshna began to do research on the cruelty meted out to animals. “I saw with my own eyes how cows, packed very tightly together, were transported in open trucks,” she says. “They would travel for days without food or water before they were slaughtered.”

She also realised that many hens are egg-making machines. “They are genetically bred to lay between 250 to 300 eggs a year,” she says. “But in the wild, hens only lay eggs during the breeding season – primarily in the spring – and only enough eggs to assure the survival of the species.”

But laying an egg takes a lot of effort. “All the nutrients go into the egg and the hen becomes very weak and diseased,” says Sudakshna. “And finally they are slaughtered.”

All this cruelty made Sudakshna forgo non-vegetarianism and become a vegan. “I have food which has no animal products,” she says. So her diet includes dosa, sambar, wholegrain rice, chappatis, dal, fruits and salads. “By cutting milk out of my diet, my skin tone has improved,” she says. “There is no acne. I have not had skin problems for a long while.”

However, for those who love milk, Sudakshna suggests plant-based milk like soya. “It tastes similar and has no side-effects,” she says.

(An input for a cover story on veganism, Sunday Magazine, South India editions and New Delhi)

Published on September 09, 2018 21:46

September 5, 2018

Reaching Out To The Distressed

Anshu Gupta, the Magsaysay Award winner, talks about the efforts taken by his organisation, ‘Goonj, to help the flood-affected in Kerala

Photo by Albin Mathew

By Shevlin Sebastian

During his travels in Ernakulam district following the massive flooding in Kerala, Magsaysay Award winner Anshu Gupta came across a man feeding a banana to his cow. It was the first time in Kerala that he had seen this scene. “Nobody was bothered about the animals,” says Anshu, at the relief collection hub in the basement of the Gold Souk Mall, Kochi. “Many had died. Because of water everywhere, there was no fodder for the animals.”

In front of the man's house, his paddy field was under water. The man told Anshu, “I know people like you will give us rice and other materials. But the fact is that, after you go, nobody will be there for me. I have lost everything.”

And so have lakhs of people in Kerala. “People have lost financially, emotionally and physically,” he says. “Malayalis are not like the people of Uttar Pradesh, Assam and Bihar, who have, over time, become resilient because floods happen so often in their areas. This is a new experience for the people of Kerala.”

And Anshu questions the assurances that have been given by some senior people in the administration that the flood-affected have received a lot of relief. “If we think that by giving 5 kgs of pulses and 10 kgs of rice, everything is normal, that is not true,” he says. “The people need food for several months before they are able to start earning themselves.”

Anshu runs Goonj (a Hindi word which means the echo of a sound] and, for the past twenty years, they have been working in 22 states including disaster-prone areas like Assam, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand.

In fact, he found a few similarities between Kerala and the Uttarakhand disaster of 2013. “The force of the water in Kerala was similar to the floods at Uttarakhand,” he says. “But since the government machinery in Kerala operated in a far more efficient manner, along with the Army, Navy, the local people as well as the fishermen, there were far fewer deaths. This is highly commendable.”

Asked about the future, Anshu says, “Kerala will recover. Every state ultimately recovers. That is the resilience of the people. Roads and bridges will come back. However, recovery, to me, is whether the people will have the same lifestyle they had before the disaster. I fear the quality of life may go down for some time.”

But he wonders whether Keralites will learn a lesson from this. “Will the people carry on building concrete structures all over the place or will they become environmentally conscious now?” he says. “Instead of agencies and organisations interfering, we should leave it to the people to rebuild the structures in the way they think is suitable, under certain guidelines. Many multi-storied buildings collapsed because they were made on the slopes of hills and it was not on a secure footing. It will be sad if it is rebuilt in the same way.”

Anshu has reasons to be pessimistic. “In Jammu and Kashmir and Uttarakhand, the people rebuild the buildings in the same way it was before the floods,” he says. “The calculation was that these floods will happen once in 50 or 100 years.”

Anshu pauses and says, “But nothing is predictable these days, thanks to climate change and other factors.”

Life and career

Anshu’s turning point happened when at the age of 16, he was travelling pillion on a motorbike, which hit a tractor at Dehra Dun. “Like a Bollywood movie, I sailed over the tractor and landed in a ditch,” he says. “I was unharmed except for my foot.”

However, at the government hospital, the doctor asked for Rs 400 to do the surgery. Anshu’s father, an honest government official, refused. As a result, the surgery was not done properly.

“To this day, I am in continuous pain,” says Anshu. “But I have respect for what my father did. I tell people that if my father had paid Rs 400 I would have been standing on a bribed foot, but today I stand on my own foot.”

Another turning point came when as a college student he went to Uttarkashi in 1991 to help with relief efforts following a massive earthquake. “It was my first exposure to the problems faced by the rural people,” he says.

Seven years later, while working as a corporate manager, in a private firm, Anshu felt the urge to start a social service organisation. And that was how Goonj was born. “I feel my career as a social entrepreneur is a calling from God,” he says.

Today, Goonj has numerous schemes to help the poor and downtrodden. In fact, in their impressive book, ‘100 Stories of Change’ it tells about how Goonj helped communities change their lives by making them build walls, dig wells, clean ponds, make bridges, roofs, sanitary pads, and do disaster relief.

They are paid not by cash but through Goonj’s ‘Cloth for Work’ initiative. Not surprisingly, Anshu’s work, done with the help of his wife Meenakshi, whom he calls his ‘backbone’ and his daughter, has received accolades. In 2015, Anshu was awarded the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award. “When I stood on stage, at Manila, I missed my parents, both of whom have passed away,” he says. “But the award was a reaffirmation of the work we are doing. I felt that we are on the right path.”

But the surprising aspect of the win was how the villagers in many communities across India, where Goonj has worked, celebrated it by distributing sweets. “It was so heart-warming,” he says, with a smile.

(The New Indian Express, Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kozhikode)

Published on September 05, 2018 00:56