Benjamin Dancer's Blog, page 13

June 3, 2014

Sexting at School

Sexting at School is a must-read for mothers of teenage daughters.

Sexting at School is a must-read for mothers of teenage daughters.

Being a mother in the age of smartphones can be an unsettling experience. Sexting at School is about a teenage girl who got in trouble with the law for sexting at school. The ordeal precipitated an identity crisis for the mother, through which she learned to trust herself and to guide her daughter.

The complete ebook is available as a free download on GoodReads.com. Here’s an excerpt:

*****

The police called it child pornography. So I understood Nicole’s concern: she wanted to talk to me about her daughter. Jessica was fourteen and three years younger than her boyfriend. He had been distributing images of Jessica through his phone. Nicole was worried; she was scared, and understandably so.

Jessica still thought she was in love.

“He calls her a bitch,” Nicole told me. “I read the texts. He says horrible things to her.”

“And she still wants to be with him,” the pain I felt for her was communicated in my voice. As a teacher, I see the scenario every year, but Nicole was experiencing this for the first time. Jessica was her daughter. Not long ago she was her baby. I could only begin to imagine the suffering the situation provoked.

Nicole was in no position to hear how common this was. Why do girls throw themselves at boys who treat them badly?

In Jessica’s circumstance there was a tremendous amount of grief. She had barely processed the loss of her dad. He was killed in an accident over the summer.

“I can’t stop her from being with him. I’ve tried. I took away her phone. I grounded her. She sneaks out of the house. I drop her off at school, and she ditches to be with him.” The mascara was now running beneath Nicole’s cheekbones, “Last night, she told me that she wished it was me who was dead. He was waiting for her out front. I saw her get into his car.”

“I can’t imagine what that’s like,” I told her. “I’m sorry.”

“Unless I physically restrain her, she will find a way to get back to him.”

I allowed for a long silence, as I thought there might be more Nicole needed to say.

“What did I do? What did I do wrong?”

I didn’t answer her question. And I didn’t dismiss it. I sat with her in it.

*****

My role with Nicole is not all that different than my role with Jessica. It doesn’t matter whether you’re fourteen or forty, what you need is for someone to listen. What you need is for someone to understand.

Jessica and I talked later the same day.

“She went through my phone,” Jessica was angry. “She read my texts.”

I let her know that I understood her frustration.

“She won’t let me leave the house.”

“Why?”

“She’s trying to keep me from him.”

“Have you told her that you love him?”

“Yes.”

“And…?”

“She hates him. She doesn’t want me to see him.”

“Why does she hate him?”

At this Jessica paused. We had already talked about the pictures. She had told me stories about the boy. The way he had flaunted his sexual conquests. He was in my English class, and I had seen it firsthand: there were countless other girls.

After a long silence, she answered my question, “She thinks he’s not good for me.”

“Is he?”

It was ground we had already covered. In past conversations Jessica told me that she respects her mom for trying to protect her.

I handed Jessica a box of tissues. She wiped the tears and told me, “No. He’s really, really mean.”

I listened to her cry for several minutes. I was thinking about her father. I knew the man well. I liked him. I was thinking about her mother. I was thinking about my own daughter.

It was true for all of us. What we need is empathy.

“I’m sorry,” I told her.

She questioned me with her eyes.

So I answered it, “I’m sorry you’re so alone.”

Jessica’s whole body shook when she sobbed.

*****

The last time Nicole was in my office she asked me if she should return Jessica’s phone. We had a similar conversation the day she asked me if she should call the police.

“What do you think?”

“I think Jessica needs to figure this out for herself. I’ve tried to protect her, but I can’t. I just can’t protect her from everything.”

“Does that mean you’ll give it back?”

“No. She’s not ready for that.”

“I don’t know the answers to the particulars,” I told Nicole, “but I know this. You’re a good mom. Jessica needs you right now. She needs you to be confident in your role.”

I saw the tears washing through the mascara, gave Nicole the box of tissues and kept on going.

“Jessica loves you, and she knows that you love her. This is universal: the teenager wants desperately to have her independence, and she is terrified of it. Jessica is not aware of the fact that she is conflicted about this. She’s just a kid. As much as she pushes you away, she wants you to be strong, to love her.”

*****

I talked to Jessica again a week later.

“Do you still see him?” I asked.

She was embarrassed, “Yeah.”

“Is he good to you?”

“Sometimes.”

“How about last night?”

She hesitated then said, “Last night he left me in a parking lot. I had to borrow a phone and call my mom to come pick me up.”

“Why’d he leave you?”

“To hookup with someone else.”

“Will you see him again?”

“Probably.”

“I have a vision for you,” I said.

Jessica smiled, like she had heard lines like that from me before.

But that didn’t deter me. I have an advantage over most parents of teenagers: I’ve made a career out of the adolescent. Their behavior can be alarming, infuriating and even demoralizing, but after seventeen years of guiding teenagers as they come of age, I have established proven routines.

I have a pretty good idea of how many repetitions it will take, of how many times I’ll have to say it before Jessica can even make sense of the words, of how many more times I’ll have to repeat it before she begins to adopt the language as her own.

So I told her again, “In my vision of your future, you will love yourself too much to let a boy treat you badly.”

*****

Download the complete ebook for free: GoodReads.com

June 2, 2014

What Would Happen if the Lights Went Out?

In a previous post, I wrote about the idea of the technological singularity: the concept that once computers start thinking for themselves, everything will change. In that post I explored what might happen if the singularity took a dark turn.

In a previous post, I wrote about the idea of the technological singularity: the concept that once computers start thinking for themselves, everything will change. In that post I explored what might happen if the singularity took a dark turn.

I first started thinking about the singularity in June 2010. I was doing research for my novel Patriarch Run and ran across Ray Kurzweil’s book The Singularity Is Near : When Humans Transcend Biology.

At the time, I knew the villain in my story wanted to wipe out humanity. I got the idea of using artificial intelligence (AI) as a weapon from Kurzweil’s book. What made my story difficult to write was that I didn’t want it to be easy on the reader’s conscience: I wanted the reader to be compelled to sympathize  with the villain. More on that in a later post.

with the villain. More on that in a later post.

So here’s what I had: I knew that the villain wanted to kill us, and I knew that he was going to use AI to do it. All that was left was to figure out the gory details: what would happen to America once the lights went out.[image error]

Would you believe that a government report published in April 2008 answered that question? The report detailed what would happen in a technical language so precise there was no shying away from its conclusion. It was a rigorous and punctilious vision of the apocalypse.

Report of the Commission to Assess the Threat to the United States from Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) Attack was about the scariest thing I ever read. To get the information to my reader I summarized the 208 page report in a conversation between two characters: the Colonel and Jack.

Jack looked out the cabin window. He could see the Patriarch Run marking the location of his ranch. “Explain to me just how it is that your grandmother survived the first half of her life without electricity.”

“I’ll get to that. Did you know there are three main constituents of the power system? I didn’t either. Not until I was briefed on it by a skinny kid in glasses. That was two days ago. Generation, transmission and distribution. The part of that briefing that kept me up the last two nights was transmission. How long do you think it takes to replace a fried transformer?”

“A week.”

“Two years. That’s without a crisis, when you’re only replacing one. They don’t make them in this country anymore.”

“How many transformers are we talking about?”

“Thousands. They make them to order. Then you got these SCADA systems. Little electronic control boxes spread all over the nation’s power grid and other critical infrastructure. In the wake of a competent attack, at minimum, these devices will have to be rebooted or repaired. Many of them will have to be replaced. You know how many guys in the country know how to do that? They scour all fifty states for skilled workers when there’s a snowstorm in Buffalo.

“Those are just the rural components. Then you have these digital control systems and programmable logic controllers.”

“Sounds like a real goat-fuck.”

“We’re talking about the mother of all goat-fucks. Your typical power outage doesn’t hurt the power plants themselves. But an attack like the one we’re predicting is going to bring down a percentage of the generators. Power generators are sensitive. If the control system fails and the power plant shuts down improperly, that’s all she wrote.

“A competent attack would irreparably damage the vulnerable hardware. You wouldn’t be able to flip a switch and have power again. Even if you could mobilize, transport and feed all the trained workers in the country, it would take years to fully recover.”

“But you wouldn’t be able to mobilize, transport and feed them.”

“That’s right. No electricity to pump oil to the nation’s refineries means there would be very little finished fuel available for transportation. In addition to that, the one hundred twenty-five thousand miles of pipeline used to transport oil across the United States is dependent on the same SCADA systems as the power grid. With an inoperative SCADA system, the pipelines would have to be shutdown.

“Moreover, the process control of an oil refinery is dependent on integrated circuitry. If an attack damaged this circuitry, it would force the refinery to shutdown. As with the power generators, the forced, rapid shutdown of the nation’s refineries would wreak havoc on the hardware. A percentage of the refineries would never recover.

“In short, the quantity of fuel available to the nation would be dependent on the sophistication of the attack. If we lost the refineries, the fuel supply already in the distribution system would be almost immediately exhausted.”

Jack drew the conclusion, “Without the ability to generate power or to produce fuel, the whole country would simply stop.”

“Yes, it would. We’re talking about raw sewage overwhelming the Nation’s waterways, no drinking water, no food in the grocery…”

“Then how’d your grandmother get by without electricity?”

“Eighty years ago you couldn’t have brought about the end of the world by simply turning out the lights. You’re right about that. But times have changed. Today it takes electricity to do just about anything. Starting with food production…It takes electricity to irrigate crops. Electric pumps, valves, and other machinery. Eggs and poultry are produced in dense populations in controlled environments using computerized feeding, watering and air conditioning systems. In the twenty-first century it even takes electricity to milk a cow.

“The list goes on. The processing of food requires electricity: Captain Crunch, a can of soup, sliced bread. Meat packing requires an electrically powered processing line.

“Farm machinery runs on petroleum products. And the food has to be distributed. When my grandmother was a schoolgirl, food was grown around urban centers. Production was more labor intensive and electricity wasn’t very important. Except for your cattle drives, up until the age of railroads and ice, you couldn’t distribute fresh food over long distances on account that it would rot.

“To get food into the supermarkets of our modern cities you need refrigerated warehouses. You need refrigerated trucks and trains, which, once again, run on petroleum. Without electricity and petroleum the whole thing stops.

“My grandmother was born in 1902. At the turn of the century, forty percent of the population lived on farms. Today it’s two percent.

“You know what that kid told me: in the event of an attack like the one we’re predicting, you wouldn’t even be able to mobilize an emergency labor force to work the farms because nobody knows how anymore. The knowledge is lost.

“The population of the United States at the turn of that century was seventy-six million. It’s what…three hundred million today?

“Back when my grandmother was a little girl a power outage carried no threat because civilization wasn’t yet dependent on electricity. We’re feeding two hundred twenty-four million more people today. That’s an increase of four hundred percent, but we have only increased the amount of land we farm by six percent. To make everything work the American farmer has figured out how to increase yield by more than fifty-fold.

“How? Technology. Machines, fertilizers, pesticides. All of which are powered by petroleum. All of which are manufactured with electricity.

“So, yes, food will still grow, but without electricity, we’ll be back to 1902 yields. If everything went perfectly, which it wouldn’t, you’d have enough food for one quarter of the population. That’s best case scenario.

“Food has always been, and may always be, the weak link in the security of a civilization. A typical supermarket carries a one to three day supply of food for its community. So what happens when the power goes out for several years?

“I’m telling you that kid was a scary motherfucker. Most people have never asked themselves these questions. I never did.”

“Are you telling me there are no contingency plans for the production of fuel?”

“There was a push from the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources last fall to secure the refineries from this type of attack.”

“And?”

“The energy lobby raised hell with one hand and donated vast sums to reelection campaigns with the other. The Chairman of the committee flipped. He came to believe that the plan was too expensive, that it would hurt the economy.” The Colonel stood up and stretched. “In effect, the deadline to safeguard the Nation’s critical fuel supply was pushed back twenty-five years.”

He opened the fridge, took out a Coke and offered it to Jack.

“No thanks.”

“You want to hear something bone-chilling?”

Jack leaned forward.

“An attack planned by a super-intelligent computer would be multi-pronged. If a device is connected to the internet, a telephone network or a satellite, it can be hacked. The banking system would collapse. With it, all commerce.

“Worms would be hidden inside the software code of the nation’s critical infrastructure: chemical processing plants, manufacturing facilities, ports–all strategically synchronized for a worse-case-scenario attack. A passive attack would simply shut the facilities down. A more aggressive attack would override the safety protocols. The displays in the control rooms would read system normal. Meanwhile gremlins would be running amuck throughout the plants overloading the machinery, creating dangerous pressures, critical temperatures. By the time the engineers figured it out, there would be fires, explosions, toxic clouds, chemical waste spilling into waterways.

“A computer smart enough could deny us the ability to control some of our weaponized nuclear assets. Any military hardware, vehicle or communications device connected to a network would be at risk of sabotage. Any country who came to our aid would be vulnerable to the same type of attack.”

“That’s an impressive catastrophe.”

“And I’ve only been briefed on the nightmares they’ve thought of so far. A computer smart enough could take over the country’s one hundred and four commercial nuclear reactors simultaneously. At which point, the reactors would run themselves to meltdown or be shutdown manually by the plant operators. Assume, for the moment, all one hundred and four reactors could be safely shut down: there is no shutting down the half-life of a radioactive isotope.

“It takes electrically powered cooling pumps to keep the spent fuel in these facilities from getting over heated. In the wake of such an attack, there would be no deliveries of diesel. Once the emergency generators ran out of fuel, the cooling pumps would shut down. If that happened, the spent fuel would heat up, boil off the water containing them then melt through the reactor cores.

“Even if the nuclear facilities could be shut down properly, without power to circulate water and cool the fuel, you would have Armageddon.

“The President would wakeup to radiation, toxic plumes spewing from chemical manufacturing plants, fires at oil refineries. Using the finite resources available to him, he could communicate by messenger and make strategic choices. Select installations could be saved or, at least, catastrophic failure postponed. But there wouldn’t be enough calculative power in the Federal Government, let alone supplies, to cope with the magnitude of the disaster.

“Here’s the kicker. The conflagrations, the poison clouds, the threat of meltdown would amount to a dazzling distraction. Such a spectacle would captivate the government’s attention, but its purpose would be to keep us from addressing the actual problem.

“The real threat is, and always has been, starvation. If you can’t distribute food, you don’t have a civilization. Forget about the economy. Wall Street went extinct the minute the power went out. Wealth will be counted in canned goods and the guns and ammunition stockpiled to defend them.

“Mass starvation, disease. The conservative number is one hundred fifty-three million casualties by the end of the first year. The middle of the road estimate: two hundred million. Not a bullet fired.”

Jack looked out the window at the city beneath them. “Talk about culling the herd.”

The Colonel cocked his head.

“Doesn’t all this assume the Chinese have a will to destroy us?”

“No, it does not. No rational state would jeopardize its own existence to strike at the United States of America. The country has a formidable nuclear deterrent. A super-intelligent computer would likely be able to neutralize the vulnerable assets of that arsenal. But by design the arsenal is diverse with terrestrial, airborne and maritime assets. Including highly portable tactical warheads. Some of which are so low tech it would be impossible to digitally disarm them.

“In short, if China attacked the United states, it would be obliterated. And the President has another option. A warhead of sufficient size detonated above the Chinese mainland would create a high altitude electromagnetic pulse that would, in effect, put them in the same boat as us.”

“If China’s not the threat, who is?”

“Yan Shi is essentially software. Software that can be sold and distributed to the highest bidder. If you were POTUS, would you take that risk?”

“It doesn’t make sense for the Chinese to sell it. If it were that powerful, they would want control. Besides, the consequences of an attack like the one you described would be catastrophic for everyone.”

“You’re right about that. Aside from the complete loss of China’s investment in American currency and the loss of its customer base for manufactured goods, the total collapse of the United States of America would precipitate a global economic super-depression. There would be unprecedented, planet-wide political instability. That’s a nightmare scenario for any surviving state.”

“But a medieval paradise for an Islamist extremist.”

“Yes, it would be. The Chinese have no interest in giving up control of Yan Shi, but could they prevent the software from being stolen?”

The Colonel looked out his window. The Criterion was banking and descending.

“Why me? Why not abduct the professor and take out the computer?”

“Those details are being handled by whiter agencies.”

May 31, 2014

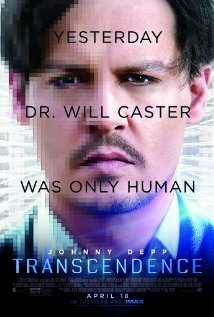

Transcendence

The technological singularity is an event after which, theory says, everything will change. Everything. It is theorized that the singularity will happen once computers can think for themselves. A concept that is beginning to find its place, not only in technological circles, but in the cultural mainstream. Transcendence, a film starring Johnny Depp, takes on this theme.

The technological singularity is an event after which, theory says, everything will change. Everything. It is theorized that the singularity will happen once computers can think for themselves. A concept that is beginning to find its place, not only in technological circles, but in the cultural mainstream. Transcendence, a film starring Johnny Depp, takes on this theme.

In a technological singularity the potential for good is unlimited. So is the potential for evil. According to the dark narrative, the rush toward the development of artificial intelligence (AI) will be humanity’s undoing.

That humans are about to destroy themselves has been in the Zeitgeist for some time. It is the premise behind the rise in popularity of post-apocalyptic stories. When I think back to my adolescence, I remember The Terminator. A generation later came The Matrix. Now we have The Hunger Games and Divergent. All of these stories are relating an anxiety most of us share, that humankind is really messing things up.

The technological singularity borrows its name from astrophysics. A singularity is another name for a black hole. We know that once you cross the event horizon of a black hole, there is no coming back.

What happens once computers start thinking for themselves? It’s a theme I explore in my literary thriller Patriarch Run:

“There are some hair-raising potentialities. First of all, we’re talking about a software that evolves at an exponential rate. So whatever it can do now, it can do exponentially better tomorrow and better the day after that and so on. A software that will eventually design its own hardware, design the machines to build that hardware.”

“There are some hair-raising potentialities. First of all, we’re talking about a software that evolves at an exponential rate. So whatever it can do now, it can do exponentially better tomorrow and better the day after that and so on. A software that will eventually design its own hardware, design the machines to build that hardware.”

“You’re talking about a factory.”

“Eventually, yes. But we are not concerned about a factory in the conventional sense.”

Jack stopped at the gate, waiting for the explanation.

“With access to nanotech manufacturing, a computer like Yan Shi could build anything, do anything. Evolve at a pace never seen before on this planet. In the intelligence community, we call this the Technological Singularity.”

“As in a black hole?”

“Precisely. We are living at the event horizon. They call it the Singularity because, just like with a black hole, nobody knows what happens once you cross this line. Only that everything changes.” The Colonel led him through the gate and across the tarmac to the Cessna’s gangway. “It’s all theory. Theory that is taken very seriously by a heretofore neglected niche of the intelligence community.”

“To be clear,” Jack offered, “we’re talking about Terminator, The Matrix.”

The Colonel stopped at the top of the gangway. “As cautionary tales, yes, we are. But there’s also a best case scenario.”

“Which is?”

“In the right hands, this might be the technology we need to solve the great problems of our age. Unlimited, clean energy. Hunger and disease would be topics of history. We might be talking about the next stage in human evolution.”

They sat facing each other in the cabin.

“You’re saying this computer could usher in a new age?”

“Perhaps. But only the dreamers are looking that far ahead. You and I have a more immediate concern.”

“Which is?”

“How long do you think it would take for a computer brain evolving at an exponential rate to become intelligent enough to make the entire digital security apparatus of the United States obsolete?”

“I don’t know.”

“Neither does anybody else.”

Jack opened the window shade.

“We’ve known that the country has been vulnerable to a cyber attack on its power grid for years. A blackout which would effect everything from tap water to food production. Such an attack wouldn’t require a super-intelligent computer. It could be done from a college dorm.

“Now imagine what a cyber attack planned by Yan Shi might look like. It is the consensus of the heretofore neglected niche of the intelligence community that if an attack with a high enough level of sophistication were executed against the power grid and other critical infrastructure simultaneously, the nation would be unable to recover.”

The Cessna Citation accelerated down the runway, lifted its nose and was airborne.

“That’s a grim prediction.”

“Yes, it is.”

May 28, 2014

Transcendence

The technological singularity is an event after which, theory says, everything will change. Everything. It is theorized that the singularity will happen once computers can think for themselves. A concept that is beginning to find its place, not only in technological circles, but in the cultural mainstream. Transcendence, a film starring Johnny Depp, takes on this theme.

The technological singularity is an event after which, theory says, everything will change. Everything. It is theorized that the singularity will happen once computers can think for themselves. A concept that is beginning to find its place, not only in technological circles, but in the cultural mainstream. Transcendence, a film starring Johnny Depp, takes on this theme.In a technological singularity the potential for good is unlimited. So is the potential for evil. According to the dark narrative, the rush toward the development of artificial intelligence (AI) will be humanity’s undoing.

That humans are about to destroy themselves has been in the Zeitgeist for some time. It is the premise behind the rise in popularity of post-apocalyptic stories. When I think back to my adolescence, I remember The Terminator. A generation later came The Matrix. Now we have The Hunger Games and Divergent. All of these stories are relating an anxiety most of us share, that humankind is really messing things up.

The technological singularity borrows its name from astrophysics. A singularity is another name for a black hole. We know that once you cross the event horizon of a black hole, there is no coming back.

What happens once computers start thinking for themselves? It’s a theme I explore in my literary thriller Patriarch Run:

“There are some hair-raising potentialities. First of all, we’re talking about a software that evolves at an exponential rate. So whatever it can do now, it can do exponentially better tomorrow and better the day after that and so on. A software that will eventually design its own hardware, design the machines to build that hardware.”

“There are some hair-raising potentialities. First of all, we’re talking about a software that evolves at an exponential rate. So whatever it can do now, it can do exponentially better tomorrow and better the day after that and so on. A software that will eventually design its own hardware, design the machines to build that hardware.”“You’re talking about a factory.”

“Eventually, yes. But we are not concerned about a factory in the conventional sense.”

Jack stopped at the gate, waiting for the explanation.

“With access to nanotech manufacturing, a computer like Yan Shi could build anything, do anything. Evolve at a pace never seen before on this planet. In the intelligence community, we call this the Technological Singularity.”

“As in a black hole?”

“Precisely. We are living at the event horizon. They call it the Singularity because, just like with a black hole, nobody knows what happens once you cross this line. Only that everything changes.” The Colonel led him through the gate and across the tarmac to the Cessna’s gangway. “It’s all theory. Theory that is taken very seriously by a heretofore neglected niche of the intelligence community.”

“To be clear,” Jack offered, “we’re talking about Terminator, The Matrix.”

The Colonel stopped at the top of the gangway. “As cautionary tales, yes, we are. But there’s also a best case scenario.”

“Which is?”

“In the right hands, this might be the technology we need to solve the great problems of our age. Unlimited, clean energy. Hunger and disease would be topics of history. We might be talking about the next stage in human evolution.”

They sat facing each other in the cabin.

“You’re saying this computer could usher in a new age?”

“Perhaps. But only the dreamers are looking that far ahead. You and I have a more immediate concern.”

“Which is?”

“How long do you think it would take for a computer brain evolving at an exponential rate to become intelligent enough to make the entire digital security apparatus of the United States obsolete?”

“I don’t know.”

“Neither does anybody else.”

Jack opened the window shade.

“We’ve known that the country has been vulnerable to a cyber attack on its power grid for years. A blackout which would effect everything from tap water to food production. Such an attack wouldn’t require a super-intelligent computer. It could be done from a college dorm.

“Now imagine what a cyber attack planned by Yan Shi might look like. It is the consensus of the heretofore neglected niche of the intelligence community that if an attack with a high enough level of sophistication were executed against the power grid and other critical infrastructure simultaneously, the nation would be unable to recover.”

The Cessna Citation accelerated down the runway, lifted its nose and was airborne.

“That’s a grim prediction.”

“Yes, it is.”

You can find this blog post at: http://its-not-all-gravy.blogspot.com/2014/05/the-technological-singularity.html

May 15, 2014

Bow Making In English Class

I don’t know what everyone else will be teaching next week, but I’ll be flintknapping with my English students. When they prick their fingers, I’ll give them a piece of tape to close the wound. They’ll be making arrowheads–carving them out of obsidian with granite hammerstones and antlers. I don’t know how else to teach them to read.

I’ve been teaching English for seventeen years and feel confident about my technique. Sometimes I look around at the country, the state of affairs in education, and I just don’t understand it. It seems self-evident to me that we ought to test what we want students to learn.

I want my English students to be curious, to rediscover the joy of learning. I want them to be passionate readers, to be critical thinkers. To know when they’re being duped.

So we’ve been making bows. I gave them some oak, a draw knife. Built them a jig so they could make their own bow strings. Then we sewed quivers, built arrows and targets. Now we’re shooting.

Yes, at school.

The first time out half the kids couldn’t nock an arrow without it falling off the string. They’re getting better.

But I never wanted them to become good archers. I wanted them to invest themselves in a difficult project, to persevere, to fail and to overcome that failure: their bows broke; they split their arrows; they cut their nocks too fat, their strings too short.

I wanted them to experience the rewards discipline yields. I worry that that particular type of commitment might be dying in our culture.

We’re reading The Hunger Games trilogy. But I didn’t think that was enough to draw in the kids who never read. The video-game kids. The parents-who-never-read-to-them kids. It’s a rule of mine: no student can hate reading. Because I know that they love it. Some of them just don’t realize it yet. That’s my job, to surprise them.

To tell you the truth: I can’t stand The Hunger Games. But it engages my students. It’s where they’re at. So I meet them there.

This year we’re making bows.

I’ve met them at other places in the past. Last year we studied organized crime. We read The Godfather, Killing Pablo: the Hunt for the World’s Greatest Outlaw and Against all Enemies. The year before that we studied America’s wars: Lone Survivor: The Eyewitness Account of Operation Redwing and the Lost Heroes of SEAL Team 10, Robert’s Ridge: A Story of Courage and Sacrifice on Takur Ghar Mountain, Afghanistan and Generation Kill. The year before war was the year we studied the two Bobs: Catch a Fire: the Life of Bob Marley and Chronicles: Volume One.

I read widely each summer, looking for texts, themes that will both educate and attract kids.

*****

You know the curriculum works when the students want to teach it.

One of my students fell in love with John Muir, an iconic American naturalist. The student wanted to teach a class about the man. He also wanted to lead a trip to Yosemite National Park in order to see, first hand, the landscape that had inspired Muir. It seemed like a good idea to me. So, together with one of my colleagues, I sponsored the student’s class. The student read everything John Muir wrote and lectured these kids for a semester on Muir’s life. The kids in the class became experts on the man: his reading habits, the names and fate of his children, his preference in footwear, the details of his travels.

The itinerary for the trip was detailed and pages long. In short, my colleague and I drove the class in a bus from Colorado to Yosemite, to SanFrancisco, to the Muir Woods and back. We hiked through the mountain valleys Muir fought so assiduously to preserve. We camped along the same rivers, slept under the same trees. We talked to a number of the nation’s leading experts on John Muir. This is no exaggeration: everywhere we stopped, the students on this trip were educating the experts. But that wasn’t because of me. I wasn’t much more than a driver, that and one of the sponsors who made the whole thing legal.

A few weeks ago, the science teacher in the room next to me took his archeology class to Harvard. These high school students have a permit from the Navaho Nation to work in a canyon system in the Four Corners area. The class traveled to Harvard, among other things, in order to be the first to transcribe the original field journals of Alfred V. Kidder and Samuel J. Guernsey, a pair of archeologists who studied the same canyon system in the early part of the last century. When they’re not at Harvard, the students are in the field documenting ancient artifacts.

In January, the teacher across the hall from me took her Spanish class to Nicaragua for three weeks. The students lived with their Nicaraguan host families, learned Spanish and volunteered their labor building a community center.

Trips like this take place every month. It’s what we do at the Open School.

*****

The first thing a new student does when they arrive at our high school is to prepare for the Wilderness Trip: a four day backpacking experience in the Mount Evans Wilderness. The trip is a very effective way to communicate to new students that our school is different–that we are going to educate the whole child.

While we hike, the kids tell me about their lives. They talk about hurts: being bullied, relationships. They share their fears, their hopes. The magic of the trip is this: I become a real person to my students, and my students become real people to me.

When you spend that type of time together: sitting out thunderstorms, hiking under a full moon, eating tortilla sandwiches–there emerges for each kid a theme. That theme tells me who they are. For example, there’s always one looking for the easiest way out. There’s usually one who picks up the slack–a kid who takes care of the needs of the group. I listen as they talk to each other. Their language gives me insight into their passions and the emotional scars they carry. They way they hold themselves tells me how confident they are. I begin to see what makes them tick, what their gifts are, what they’re guarded about. So before we ever meet in the classroom, I know them.

The Wilderness Trip is more than a powerful educational tool, it’s the best pedagogy I’ve ever experienced. The trip puts into practice the secret of quality education: like just about every other human endeavor, it’s about relationships.

Which brings me to my confession.

Although I’m an English teacher, English is not really what I do. I spend hours every week just listening to kids. It’s my job. They tell me their stories. They talk about their girlfriends. About their abortions. About their parents, or the lack thereof. Their family members in prison. The alcoholism in their homes. They share their dreams with me. Their college plans and ambitions. They consult with me in order to layout a path to their future careers. They consult with me about the classes they, themselves, are teaching. About ways they can give back to our school community. They share their research projects. Their photography. Their poetry. They show me the razor scars on their forearms. Their sketch books. They paint murals in my classroom. And talk to me about their addictions.

In that sense, more than I am an English teacher, I am a witness.

Our curriculum provides the time for me to learn who my students are. As a matter of fact, I’ve come to rely on the patterns I see in my students during the course of the Wilderness Trip to guide me. The theme I become aware of on that trip typically unfolds in a student’s life over the years to come.

So I hold a vision for each of my students. My job is to help her to see it, help her to appreciate her strengths and help her to be aware of her weaknesses. To encourage her to write her own story so that it won’t be written for her.

It’s not enough that I hold a vision. The kid needs to hold his own vision. When we talk together about his life–whether it be steeped in a ruin not of his own choosing or love and happiness–I want him to learn to chart a course for his heart. I want him to begin to decide who it is he wants to be. What type of father. What type of partner. I want to hear him make those choices, and if I’m lucky, he will keep me in his life long enough so that I can witness it as he begins to actualize them.

Here’s one for the reformers: at the Open School we formalize the conversations I outlined above into curriculum, self-directed student projects. We call them Passages.

*****

How do you know if a school is any good?

Here’s a test: I wish we’d standardize it. Ask a kid whether or not he likes school. The answer, you’ll find, is depressing. At my first teaching job nobody liked school. They liked seeing their friends. Socializing. But, at best, the students tolerated their classes. Most of them, ninety percent of them, just endured it. There were exceptions, but they were the minority.

Ask any student at my school whether or not they like it. I know the answer. Ninety-nine percent of them do. They hang out in my classroom after the end of the school day. They come back for years after they graduate. Because it’s a safe, loving community, it’s hard for them to leave.

If that sounds unbelievable to you, you need to come and see it for yourself: see what it’s like for kids to be passionate about their education.

*****

Just what is it I’m trying to say about school?

Maybe I can persuade someone of this: humans are curious. We love to learn. It’s in our nature. Pair that fact with the observation I made earlier: most high school students hate school.

Something is wrong.

In Colorado we have a statewide assessment, and it garners too much money, too much attention. Are we really going to focus our worry on a test score when millions of kids who are hardwired to be curious, to love learning, hate being in the classrooms designed to meet that need?

I’m not.

When I conduct my assessments, I’m going to test what I want my students to learn. I want my English students to learn to practice. I want them to learn discipline and perseverance. Since most of them have no experience with that type of ethic, it comes easier, much easier, if they are allowed to enjoy the work they do. I know, even if the kid doesn’t yet, that she likes to read. As soon as she realizes this, she will want more. And once she starts, she cannot be stopped.

So I taught her to make a bow.

*****

This essay can be downloaded for free at this link Bow Making In English Class.

May 5, 2014

The Technological Singularity

"Stephen Hawking is sounding the alarm bell on artificial intelligence, warning that the creation of...successful AI could be the last thing humans ever do."

The villain in my literary thriller PATRIARCH RUN actively seeks a planet-wide collapse through this means.

In my story it's up to Billy to stop him.

Stephen Hawkings Warning About AI

April 20, 2014

Reading Tuesday Evening at the BookBar Denver

-PATRIARCH RUN

I'll be reading from my literary thriller PATRIARCH RUN Tuesday, 22 April, at 7pm, at the BookBar in Denver. If you're in town, it'd be great to see you.

PATRIARCH RUN can be read as a quest for a father, Billy's search for his mother. An Adventure Passage, if you're an Open School Alumni. I'll be highlighting that theme Tuesday evening.

4280 Tennyson St.

Denver, CO. 80212

720-443-2227

The BookBar

PATRIARCH RUN is a thoughtful and character driven literary thriller. Think of it as Jason Bourne meets Good Will Hunting.

All April proceeds from PATRIARCH RUN will be donated to Jefferson County Open School. The school coordinates with Lighthouse Writers Workshop to bring local authors into the classroom. The purpose of the fundraiser is is support that program.

Patriarch Run

April 15, 2014

The sheriff talking to Billy, PATRIARCH RUN

April 14, 2014

Jack's letter to Billy, PATRIARCH RUN

April 13, 2014

HOME by Toni Morrison

Home by Toni Morrison

Home by Toni MorrisonMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Toni Morrison’s HOME is about siblings. It’s about Cee, a young girl who had to be taught her own value. It’s about Frank, a Korean War veteran, who had to learn the hard way, under leaves gone “wild in the glow of a fat cherry-red sun,” what it means to stand as a man.

It’s about honesty.

HOME is about rising above whatever deck of misfortune life has dealt. It’s about claiming yourself. Respecting yourself. Cee learns it through the nursing women who bring her back to health. Through their ministry, she learned to love herself.

HOME is about regret. Dealing honestly with regret. Coming to terms with what it is we’ve done. And standing up and moving on. Frank learns it from a story, in which he played a small part, about a man who loved his son.

View all my reviews