Benjamin Dancer's Blog, page 10

October 14, 2014

Censoring American History

My students walked out on me last week. Just got up, left my classroom and marched right out of the school. I’ve been an English teacher in Jefferson County, Colorado, for eighteen years and I’ve never seen anything like it. I know Julie Williams personally; she’s the School Board member who submitted the controversial proposal to create an additional curriculum review committee for our school district.

My students walked out on me last week. Just got up, left my classroom and marched right out of the school. I’ve been an English teacher in Jefferson County, Colorado, for eighteen years and I’ve never seen anything like it. I know Julie Williams personally; she’s the School Board member who submitted the controversial proposal to create an additional curriculum review committee for our school district.Above is the opening paragraph of the article I published in the Humanist yesterday. The piece gives needed context to this national debate.

You can fidn the article here: http://thehumanist.com/commentary/cen...

October 13, 2014

Censoring American History

I published a piece in the Humanist today about the student walkouts in Jefferson County, Colorado, where I teach.

http://thehumanist.com/commentary/censoring-american-history

The post Censoring American History appeared first on The Old Man.

October 6, 2014

Elizabeth Kolbert, Author of The Sixth Extinction, on the Daily Show

Read my review of Kolbert’s The Sixth Extinction.

Read my review of Kolbert’s The Sixth Extinction.

The post Elizabeth Kolbert, Author of The Sixth Extinction, on the Daily Show appeared first on The Old Man.

October 5, 2014

The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History by Elizabeth Kolbert

Elizabeth Kolbert’s The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History is a walk down memory lane–that is, if you’re the planet. She takes the reader all over the globe, from Iceland to the Great Barrier Reef. Kolbert presents each chapter, in this journalist’s account of life departed, as a multi-facetted story, at the center of which is usually a quirky scientist. She gives us a sense of what it is like for these insatiable truth-seekers to be in the field (the Amazon jungle, One Tree Island, the Uplands of Scotland, etc.). The book is, at its core, a fascinating overview of the ground breaking research that continues to shape our understanding of who we are (evolutionarily speaking) and where we are going.

Elizabeth Kolbert’s The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History is a walk down memory lane–that is, if you’re the planet. She takes the reader all over the globe, from Iceland to the Great Barrier Reef. Kolbert presents each chapter, in this journalist’s account of life departed, as a multi-facetted story, at the center of which is usually a quirky scientist. She gives us a sense of what it is like for these insatiable truth-seekers to be in the field (the Amazon jungle, One Tree Island, the Uplands of Scotland, etc.). The book is, at its core, a fascinating overview of the ground breaking research that continues to shape our understanding of who we are (evolutionarily speaking) and where we are going.

Each chapter in Kolbert’s work shares a somber theme: extinction. We learn about the ancient ammonites and the more recent mastodons. We come to understand the competing theories regarding the asteroid that dispatched the dinosaurs, the economics that doomed the great auk, and we get to participate as Edgardo Griffith tries to understand why amphibians are disappearing from the biosphere.

The title is a reference to the five great extinction events that have occurred in our planet’s history, and it suggests that the sixth extinction is being caused by humans and picking up steam. The book never gets preachy. It is always interesting. Kolbert presents a portfolio of extinctions, many of which are incontrovertibly human caused, and in the end, leaves it to us to draw our own conclusion about where the evidence leads.

I was fascinated by the details: episodes in the life of Charles Darwin, the graffiti contemporary scientists leave at their field stations, the dark humor they share about our eventual fate, and the overwhelming diversity, or strangeness, of the flora and fauna which we call life.

The Sixth Extinction provokes anxiety. I can’t remember a single mention of the word overpopulation in the text, but it kept occurring to me as I read: there are too many people. Too many people to live this haphazardly in such a finite biosphere.

Take the mathematics of extinction, for example. An extinction event does not necessarily have to be sudden and catastrophic. I learned that continual downward pressure, even gentle pressure, on a population will drive a species to extinction over the course of hundreds or thousands of years. What got my attention was that such an extinction would be geologically instantaneous, but “too gradual to be perceived by the people who unleashed it.”

It’d be easy to mistakenly believe that in the age when humans existed alongside the Neanderthal our population was too small, our technology too primitive to have much of an impact on the broader ecological system. But we’d make that mistake only if we studied a few generations. After many generations of contact, the Neanderthals were wiped out.

Looking at the event through the mathematics of continual downward pressure on the population, the Neanderthal was doomed upon our arrival. So were many other species.

The advantages evolution gave humans allowed our ancestors to create agriculture and, in the 1940s, fertilizer. That technology has allowed our population in the last seventy years, or so, to spike from about 2 billion to about 7 billion people.

If, by simply getting by, a few million humans could inadvertently wipe out multiple older, well-adapted species, what will be the effect of 7 billion humans living, in comparison to our ancestors, quite lavishly?

I kept thinking of my most recent story, Patriarch Run, as I read The Sixth Extinction. In my story, the villain or hero, depending on how you view the dilemma, is obsessed with the exponential growth of the human population. Certain that humans are causing the sixth great extinction, he seeks to wipe out his own species, to reduce its population to what it was during the stone age.

What I find interesting is the debate generated by the novel’s readers: many of them are horrified by the thought of killing so many innocent people; others see it as the lesser of two evils.

For those willing to look, great forces have been set in motion, which means there are some big changes coming down the ecological pike. I think I wrote my story for the same reason Kolbert wrote hers: I’d prefer it if we paid attention, if we asked the hard questions.

For those willing to look, great forces have been set in motion, which means there are some big changes coming down the ecological pike. I think I wrote my story for the same reason Kolbert wrote hers: I’d prefer it if we paid attention, if we asked the hard questions.

The post The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History by Elizabeth Kolbert appeared first on The Old Man.

October 2, 2014

Are Preppers Crazy?

For those who haven’t noticed, there is a vibrant survivalist movement alive in America. We appear to be in the third wave of this movement. The first wave could be traced back to Howard Ruff’s 1974 publication of Famine and Survival in America. The second wave peaked at Y2K, and the third wave began after September 11, 2001.

For those who haven’t noticed, there is a vibrant survivalist movement alive in America. We appear to be in the third wave of this movement. The first wave could be traced back to Howard Ruff’s 1974 publication of Famine and Survival in America. The second wave peaked at Y2K, and the third wave began after September 11, 2001.

A prepper can be understood as someone who actively prepares for emergencies and great disruptions in the social and political world order. To many Americans their obsession with catastrophe and preparedness seems crazy.

Which is a question we might want to take seriously.

The movement made it onto most of our radar screens in 2012 after it was revealed that Nancy Lanza was a prepper. Nancy Lanza was shot to death by her son Adam Lanza right before he massacred twenty-six people, most of which were first graders, at Sandy HooK Elementary School.

Although the prepper movement is dismissed by many as fringe, it is doing well today, vibrant enough to support whole industries, from classes in self-defense to a publishing bananza of how-to-guides.

The stereotype of a prepper includes conservatism and a belief in individual responsibility–which, in this context, can be translated into preparedness: large stockpiles of food, water, guns, ammunition, bug-out-bags and well-rehearsed emergency plans.

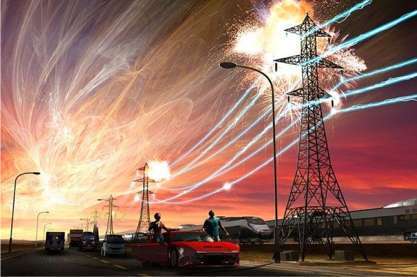

Although there is a strong stereotype, preppers come in many varieties. One of the interesting aspects of so much variety is the glut of doomsday scenarios. There are hundreds of ways for us to die, including: natural disasters, super-viruses, biochemical catastrophes and financial collapse. One doomsday scenario in particular made its way to a subcommittee hearing in the halls of Congress in May of this year. The hearing was titled “Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP): Threat to Critical Infrastructure.”

Although there is a strong stereotype, preppers come in many varieties. One of the interesting aspects of so much variety is the glut of doomsday scenarios. There are hundreds of ways for us to die, including: natural disasters, super-viruses, biochemical catastrophes and financial collapse. One doomsday scenario in particular made its way to a subcommittee hearing in the halls of Congress in May of this year. The hearing was titled “Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP): Threat to Critical Infrastructure.”

So the question any non-prepper should be asking is, “Are these people nuts?” Because if they’re not, maybe the rest of us are.

An EMP attack would be an event in which a nuclear device is detonated in the atmosphere. The electromagnetic pulse generated by such an attack would wreak havoc on electrical equipment, and the results would be disastrous for humans. Computers, cars, anything with electronics is vulnerable, including the power grid. As a matter fact, the point of such an attack would be to take out the power grid. In other words, the attack would decimate the critical infrastructure of the United States. The manner in which this destruction would take place is laid out in scientific detail inside a little-known government report published in April 2008 titled Report of the Commission to Assess the Threat to the United States from Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) Attack.

An EMP attack would be an event in which a nuclear device is detonated in the atmosphere. The electromagnetic pulse generated by such an attack would wreak havoc on electrical equipment, and the results would be disastrous for humans. Computers, cars, anything with electronics is vulnerable, including the power grid. As a matter fact, the point of such an attack would be to take out the power grid. In other words, the attack would decimate the critical infrastructure of the United States. The manner in which this destruction would take place is laid out in scientific detail inside a little-known government report published in April 2008 titled Report of the Commission to Assess the Threat to the United States from Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) Attack.

The report concluded that if an EMP attack were done right, it would be impossible to restore the power grid. No more electricity. The fuel refineries would be shut down, too.

No transportation. No electricity. Think about it. Without electricity, could you, I mean you–the reader and your family–could you eat?

Don’t dismiss the question. Without the grocery store, without refrigeration, without transportation, without irrigation, without fertilizer, without pesticides, without factory farms…could you eat? There are, give or take, about 300 million desperate, starving people in the same situation, hunting, fishing, scavenging, stealing, killing. Could you eat?

Here’s the kicker: you don’t need an EMP attack to create this catastrophe. All you need is for the power to go out. A computer hack. A solar flare.

Our civilization, and this is a factual statement, is dependent on electricity. We are as vulnerable as our appetite. If food production today is dependent on electricity and oil, without power you lose the grocery store.

What then?

I wanted to explore the question further: why are our lives now dependent on electricity? So I fleshed out the government report I cited above as a scene in my new novel PATRIARCH RUN. You can read it below.

Jack looked out the cabin window. He could see the Patriarch Run marking the location of his ranch. “Explain to me just how it is that your grandmother survived the first half of her life without electricity.”

“I’ll get to that. Did you know there are three main constituents of the power system? I didn’t either. Not until I was briefed on it by a skinny kid in glasses. That was two days ago. Generation, transmission and distribution. The part of that briefing that kept me up the last two nights was transmission. How long do you think it takes to replace a fried transformer?”

“A week.”

“Two years. That’s without a crisis, when you’re only replacing one. They don’t make them in this country anymore.”

“How many transformers are we talking about?”

“Thousands. They make them to order. Then you got these SCADA systems. Little electronic control boxes spread all over the nation’s power grid and other critical infrastructure. In the wake of a competent attack, at minimum, these devices will have to be rebooted or repaired. Many of them will have to be replaced. You know how many guys in the country know how to do that? They scour all fifty states for skilled workers when there’s a snowstorm in Buffalo.

“Those are just the rural components. Then you have these digital control systems and programmable logic controllers.”

“Sounds like a real goat-fuck.”

“We’re talking about the mother of all goat-fucks. Your typical power outage doesn’t hurt the power plants themselves. But an attack like the one we’re predicting is going to bring down a percentage of the generators. Power generators are sensitive. If the control system fails and the power plant shuts down improperly, that’s all she wrote.

“A competent attack would irreparably damage the vulnerable hardware. You wouldn’t be able to flip a switch and have power again. Even if you could mobilize, transport and feed all the trained workers in the country, it would take years to fully recover.”

“But you wouldn’t be able to mobilize, transport and feed them.”

“That’s right. No electricity to pump oil to the nation’s refineries means there would be very little finished fuel available for transportation. In addition to that, the one hundred twenty-five thousand miles of pipeline used to transport oil across the United States is dependent on the same SCADA systems as the power grid. With an inoperative SCADA system, the pipelines would have to be shutdown.

“Moreover, the process control of an oil refinery is dependent on integrated circuitry. If an attack damaged this circuitry, it would force the refinery to shutdown. As with the power generators, the forced, rapid shutdown of the nation’s refineries would wreak havoc on the hardware. A percentage of the refineries would never recover.

“In short, the quantity of fuel available to the nation would be dependent on the sophistication of the attack. If we lost the refineries, the fuel supply already in the distribution system would be almost immediately exhausted.”

Jack drew the conclusion, “Without the ability to generate power or to produce fuel, the whole country would simply stop.”

“Yes, it would. We’re talking about raw sewage overwhelming the Nation’s waterways, no drinking water, no food in the grocery…”

“Then how’d your grandmother get by without electricity?”

“Eighty years ago you couldn’t have brought about the end of the world by simply turning out the lights. You’re right about that. But times have changed. Today it takes electricity to do just about anything. Starting with food production…It takes electricity to irrigate crops. Electric pumps, valves, and other machinery. Eggs and poultry are produced in dense populations in controlled environments using computerized feeding, watering and air conditioning systems. In the twenty-first century it even takes electricity to milk a cow.

“The list goes on. The processing of food requires electricity: Captain Crunch, a can of soup, sliced bread. Meat packing requires an electrically powered processing line.

“Farm machinery runs on petroleum products. And the food has to be distributed. When my grandmother was a schoolgirl, food was grown around urban centers. Production was more labor intensive and electricity wasn’t very important. Except for your cattle drives, up until the age of railroads and ice, you couldn’t distribute fresh food over long distances on account that it would rot.

“To get food into the supermarkets of our modern cities you need refrigerated warehouses. You need refrigerated trucks and trains, which, once again, run on petroleum. Without electricity and petroleum the whole thing stops.

“My grandmother was born in 1902. At the turn of the century, forty percent of the population lived on farms. Today it’s two percent.

“You know what that kid told me: in the event of an attack like the one we’re predicting, you wouldn’t even be able to mobilize an emergency labor force to work the farms because nobody knows how anymore. The knowledge is lost.

“The population of the United States at the turn of that century was seventy-six million. It’s what…three hundred million today?

“Back when my grandmother was a little girl a power outage carried no threat because civilization wasn’t yet dependent on electricity. We’re feeding two hundred twenty-four million more people today. That’s an increase of four hundred percent, but we have only increased the amount of land we farm by six percent. To make everything work the American farmer has figured out how to increase yield by more than fifty-fold.

“How? Technology. Machines, fertilizers, pesticides. All of which are powered by petroleum. All of which are manufactured with electricity.

“So, yes, food will still grow, but without electricity, we’ll be back to 1902 yields. If everything went perfectly, which it wouldn’t, you’d have enough food for one quarter of the population. That’s best case scenario.

“Food has always been, and may always be, the weak link in the security of a civilization. A typical supermarket carries a one to three day supply of food for its community. So what happens when the power goes out for several years?

“I’m telling you that kid was a scary motherfucker. Most people have never asked themselves these questions. I never did.”

“Are you telling me there are no contingency plans for the production of fuel?”

“There was a push from the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources last fall to secure the refineries from this type of attack.”

“And?”

“The energy lobby raised hell with one hand and donated vast sums to reelection campaigns with the other. The Chairman of the committee flipped. He came to believe that the plan was too expensive, that it would hurt the economy.” The Colonel stood up and stretched. “In effect, the deadline to safeguard the Nation’s critical fuel supply was pushed back twenty-five years.”

He opened the fridge, took out a Coke and offered it to Jack.

“No thanks.”

“You want to hear something bone-chilling?”

Jack leaned forward.

“An attack planned by a super-intelligent computer would be multi-pronged. If a device is connected to the internet, a telephone network or a satellite, it can be hacked. The banking system would collapse. With it, all commerce.

“Worms would be hidden inside the software code of the nation’s critical infrastructure: chemical processing plants, manufacturing facilities, ports–all strategically synchronized for a worse-case-scenario attack. A passive attack would simply shut the facilities down. A more aggressive attack would override the safety protocols. The displays in the control rooms would read system normal. Meanwhile gremlins would be running amuck throughout the plants overloading the machinery, creating dangerous pressures, critical temperatures. By the time the engineers figured it out, there would be fires, explosions, toxic clouds, chemical waste spilling into waterways.

“A computer smart enough could deny us the ability to control some of our weaponized nuclear assets. Any military hardware, vehicle or communications device connected to a network would be at risk of sabotage. Any country who came to our aid would be vulnerable to the same type of attack.”

“That’s an impressive catastrophe.”

“And I’ve only been briefed on the nightmares they’ve thought of so far. A computer smart enough could take over the country’s one hundred and four commercial nuclear reactors simultaneously. At which point, the reactors would run themselves to meltdown or be shutdown manually by the plant operators. Assume, for the moment, all one hundred and four reactors could be safely shut down: there is no shutting down the half-life of a radioactive isotope.

“It takes electrically powered cooling pumps to keep the spent fuel in these facilities from getting over heated. In the wake of such an attack, there would be no deliveries of diesel. Once the emergency generators ran out of fuel, the cooling pumps would shut down. If that happened, the spent fuel would heat up, boil off the water containing them then melt through the reactor cores.

“Even if the nuclear facilities could be shut down properly, without power to circulate water and cool the fuel, you would have Armageddon.

“The President would wakeup to radiation, toxic plumes spewing from chemical manufacturing plants, fires at oil refineries. Using the finite resources available to him, he could communicate by messenger and make strategic choices. Select installations could be saved or, at least, catastrophic failure postponed. But there wouldn’t be enough calculative power in the Federal Government, let alone supplies, to cope with the magnitude of the disaster.

“Here’s the kicker. The conflagrations, the poison clouds, the threat of meltdown would amount to a dazzling distraction. Such a spectacle would captivate the government’s attention, but its purpose would be to keep us from addressing the actual problem.

“The real threat is, and always has been, starvation. If you can’t distribute food, you don’t have a civilization. Forget about the economy. Wall Street went extinct the minute the power went out. Wealth will be counted in canned goods and the guns and ammunition stockpiled to defend them.

“Mass starvation, disease. The conservative number is one hundred fifty-three million casualties by the end of the first year. The middle of the road estimate: two hundred million. Not a bullet fired.”

Jack looked out the window at the city beneath them. “Talk about culling the herd.”

The Colonel cocked his head.

“Doesn’t all this assume the Chinese have a will to destroy us?”

“No, it does not. No rational state would jeopardize its own existence to strike at the United States of America. The country has a formidable nuclear deterrent. A super-intelligent computer would likely be able to neutralize the vulnerable assets of that arsenal. But by design the arsenal is diverse with terrestrial, airborne and maritime assets. Including highly portable tactical warheads. Some of which are so low tech it would be impossible to digitally disarm them.

“In short, if China attacked the United states, it would be obliterated. And the President has another option. A warhead of sufficient size detonated above the Chinese mainland would create a high altitude electromagnetic pulse that would, in effect, put them in the same boat as us.”

“If China’s not the threat, who is?”

“Yan Shi is essentially software. Software that can be sold and distributed to the highest bidder. If you were POTUS, would you take that risk?”

“It doesn’t make sense for the Chinese to sell it. If it were that powerful, they would want control. Besides, the consequences of an attack like the one you described would be catastrophic for everyone.”

“You’re right about that. Aside from the complete loss of China’s investment in American currency and the loss of its customer base for manufactured goods, the total collapse of the United States of America would precipitate a global economic super-depression. There would be unprecedented, planet-wide political instability. That’s a nightmare scenario for any surviving state.”

“But a medieval paradise for an Islamist extremist.”

“Yes, it would be. The Chinese have no interest in giving up control of Yan Shi, but could they prevent the software from being stolen?”

The Colonel looked out his window. The Criterion was banking and descending.

“Why me? Why not abduct the professor and take out the computer?”

“Those details are being handled by whiter agencies.”

The post Are Preppers Crazy? appeared first on The Old Man.

September 28, 2014

Is it Probable that We Will Voluntarily Bring the Growth Rate of the Human Population to Zero?

Any population that is growing will eventually double. Given the biological and psychological drives of the human species, which is more probable: that humans will voluntarily bring our own population growth rate to zero (or below) or that the eventuality of zero growth will be forced upon the species?

Any population that is growing will eventually double. Given the biological and psychological drives of the human species, which is more probable: that humans will voluntarily bring our own population growth rate to zero (or below) or that the eventuality of zero growth will be forced upon the species?

Let us assume, for the sake of this thought experiment, that the probability of zero growth being forced upon the human species by the natural laws of the biome is so great as to make the voluntary drop in the species’ growth rate seem not only unlikely but quite fantastic.

If we are to assume that humans are unlikely to collectively reduce population growth to a rate below zero, then the following moral problem becomes relevant.

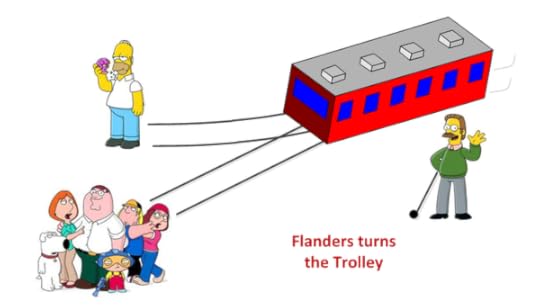

Most of us have heard of the dilemma: You are walking near a trolley-car track when you notice five people tied to it in a row. The next instant, you see a trolley hurtling toward them, out of control. A signal lever is within your reach; if you pull it, you can divert the runaway trolley down a side track, saving the five — but killing another person, who is tied to that spur.*

Which is the correct choice? In surveys, most people, 90%, opt to pull the lever, choosing one death instead of five.

To make the question more interesting philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson presented The Fat Man version:

As before, a trolley is hurtling down a track towards five people. You are on a bridge under which it will pass, and you can stop it by dropping a heavy weight in front of it. As it happens, there is a very fat man next to you–your only way to stop the trolley is to push him over the bridge and onto the track, killing him to save five. Should you proceed?

Although most people are willing to pull the lever in survey questions, very few can see themselves pushing the fat man. The numbers of lives at stake are the same in both scenarios, so why do people feel more comfortable pulling the lever than pushing the man?

The thought experiment is a useful tool in examining our morality. Ethicists tend to boil the dilemma down to this: we can act on a rational and utilitarian calculus, intentionally killing one to save five; or we can respect the subrational instinct that makes us recoil at the thought of pushing a man to his death, choosing not to act, thus allowing the avoidable death of the five.

[image error]Wanting to explore the dilemma further, I fleshed out the trolley problem in my literary thriller Patriarch Run. The story assumes a scenario in which the exponential growth of the human population threatens the extinction of the species. One man, Jack Erikson, has an opportunity to stop the unfolding ecological crisis, but to do so he must sacrifice even his own family. Depending on how you choose to solve the trolley problem, Jack is either the villain or the protagonist of the novel.

Jack tries to explain himself to his son in the letter below:

Billy,

I want you to know that I love humanity. And even more than that I love life. I want to preserve both.

When you were six years old, Billy, you asked me if I hated the elk.

“No,” I told you, “I love them.”

You looked me straight in the eye and said, “Then why do you always want to kill them?”

“I don’t always want to kill them,” I explained. I took you into my arms and I carried you to the window where we could see the forest and I told you, “I hunt them in the fall because it’s good for them and it’s good for our family.”

You didn’t let me off the hook. You asked me to put you down. You wanted to know how it was good for the elk to be killed.

It was a good question. You’ve always had a penetrating mind.

I told you that there were no more wolves in Colorado, only the ones that have snuck back into these mountains, and there weren’t enough of those, not yet, to keep the elk herds in balance.

I asked you who was left to prey on the elk?

You didn’t have an answer. There are no more brown bears in our mountains and the lions here prefer to eat the deer.

That was all you needed. At that point you understood.

But let me write this anyway, let me write it just to see the words on the page, the idea. I’ll write it for me.

Elk reproduce at a robust rate. Without predators to keep them in check the population would swell and the herds would destroy their habitat. Once their habitat was destroyed the elk, in turn, would starve. There simply wouldn’t be enough food to feed them all.

Given our choice to remove their natural predator it would be cruel not to hunt the elk because harvesting a limited number preserves the whole. In the end culling the herd saves lives.

We accept this as a biological truth, I think, that everything has to be kept in balance. The wolves are the keepers of the elk just as the elk are the keepers of the grass. At six years old you understood this. In the absence of the wolf the hunter must keep the elk. The hunter does this to also feed his family and to keep the grass because he understands that without the grass there would be no elk.

That’s what life is. We keep each other.

Our grocery stores, perhaps, have allowed some of us to forget about the simplest of all truths. That we keep each other. People who only eat the meat that is butchered for them have no appreciation for the consequence of that feast. In that sense, they have lost contact with reality.

The chasm between our own understanding of ourselves and biological reality can be illustrated in the following question, where is the wolf?

The wolf is all but exterminated. Why? Those who want to exterminate the wolf want to do so because the wolf competes with humanity for resources.

In the effort to make ourselves more secure we have exterminated our competition, those who would prey on us along with those who would compete with us. Thousands of years ago, on the scale of a few million human beings trying to make it in the world, the strategy made sense for our species because the human population was fragile.

It makes sense to eliminate the competition, to kill the wolf, today only if the lens is focused on the individual. If the harvest of an elk is detrimental to the individual elk but beneficial to the species, how can it be any different with a human being? The truth is that human beings need predators. Because of our birth rate, like the elk, we need strong competition to survive. This is a mathematical fact.

The overwhelming success of our strategy of extermination has dramatically augmented the scale of its implementation, resulting in a lack of balance.

I’ll try not to be pedantic but a little math will help to contextualize what it is I mean by balance. The growth of the human population as I write is estimated to be 1.3% per year. At the current rate of growth the population will double every fifty-three years. Six to twelve, twelve to twenty-four billion human beings in a century. To put those twenty-four billion people in perspective, the world’s population a hundred years ago was one point six billion.

Unfortunately, the resources required to sustain our civilization are not growing at the same rate as the human population. The United Nations estimates that 15% of the population goes hungry today. That’s nearly a billion people. The balance is off.

Although most people accept the concept of ecological balance they are attracted to it only in the abstract, in a Disneyesk, bloodless form.

Balance requires death, killing. This concept is missing from our current understanding of humanity’s place in the world. Our population is kept from growing out of balance as long as those who hunger for us eat. All one has to do is pay attention to understand that is how life works. The failure to understand this is a symptom of our cultural disengagement from reality.

Whereas, reality does not depend on our acknowledgement of it, it won’t deactivate its consequences because we do not recognize them.

What happens as the human population swells? Its hunger swells. And, like every other species, it satiates its hunger.

Because we are more capable than the elk we can exterminate the organisms that compete with us for resources, weeds, fungi, insects, and grow our own food supply. And rather than exhaust our supply of food when faced with a swelling population we can expand food production and satiate the hunger. But that expansion has consequences. The elk feeds by ripping the grass with its teeth. Rather than consume the surrounding habitat with our jaws we consume the habitat with our cities and our farms.

Where is the pressure, the competition, the predator to check human civilization?

Due to our ability to adapt to the radical alterations we ourselves are making to our habitat the human timeline for uncontrolled, exponential population growth is more expansive than that of the elk’s but an expanded timeline is not an infinite timeline. The result of an unchecked, exponential growth in population is always the same.

Starvation. Because we have been so successful at exterminating our competition, a wolf will be provided for us. This wolf will come in the form of our own hunger.

There will be balance.

I’ve heard it argued that technology will change this. That there will be a human exception. That we can think our way out of this natural law. But that denial, the denial of the most fundamental law of biology, will only exacerbate the inevitable consequence. We do have an incredible gift in our ability to create. But as powerful as our minds are they are housed in our animal bodies, bodies that require sustenance to survive, bodies that are hardwired to reproduce. It is true that technology has stretched the breaking point but it has not and it cannot do away with it. The law remains constant. The result of an unchecked, exponential growth in population is always the same.

Nature forces balance.

The only variable to the law is scale. Because the elk’s impact is, in the grand scheme of things, small, if the population of its herds were to swell then collapse today the ecological damage could be repaired within a few generations. The same cannot be said of humanity’s global biological impact. As a matter of fact, with the six billion hungry humans who inhabit it today it is hard to imagine a species affecting the planet on a wider scale. Unless you were to consider the twelve billion who will inhabit it tomorrow or the twenty-four billion after that.

There will be a collapse. I think we all know this. Somehow we sense it. This is true for every part of the world to which I’ve traveled. People see it coming. Yet as a culture we suppress that knowledge, like the knowledge of the inevitability of our own death. Although suppressed the awareness spills out of our cultural-subconscious like a collective nightmare. You see this in the form of our post-apocalyptic art, our entertainment.

I wish it were different. That we could discuss the problem openly. But the subject of ecological balance in the context of human beings remains taboo. So when one does speak the truth, when one speaks about our need for the wolf, it sounds radical.

However, give it time to sink in and the truth of the matter will become inescapable.

I understand that decisive action has the appearance of cruelty. However, history tells us that it is decidedly more cruel to do nothing. The number of deaths from starvation has grown exponentially with the overall population. For example, the number of people without enough to eat in the world today is equal to the entire human population of 1810.

What does the future hold? If the number of hungry people doubles with the overall population, at the current rate of growth, 1.3%, there will be two billion hungry people in fifty-three years, four billion hungry people in a hundred and six years. How long will it take before the number of people suffering from starvation grows larger than the total number of people alive on the earth today?

Moreover, the problem reaches far beyond human suffering. To do nothing is to preside over the next mass extinction.

The growth rate of the human population will drop below zero. That is certain. The remaining question is one of scale. How catastrophic will the collapse be? That is up to us. That is up to me. The sooner the population is restored to balance the gentler, the more humane will be the collapse.

That, in a nutshell, is my job. To save lives. Just as I kept the elk I have been given an opportunity to be humanity’s keeper.

Why are we now comfortable with that ethic in its application to the elk but not in its application to human beings?

Because we have been disengaged from reality.

A paradigm shift, especially for those uninitiated to the trauma, can be unsettling emotionally. And in my experience the human condition does not allow for the intellect to move forward unless the emotional needs of a person are met. That is to say, unless the person feels safe. Which is difficult, or impossible, to achieve when under threat.

I realize that it is difficult to imagine a reality more threatening than the one I am now presenting.

I understand why this is so hard to accept. I’m afraid that when it comes down to it human beings reproduce, eat and starve just like every other animal. The belief of human exceptionalism in this regard is a blinding myth. Perhaps that false belief is why the truth is so painful to us. To be clear, I am not suggesting that an elk’s life is as valuable as a human’s. To me, it is not. I am only stating that humanity is governed by the same biological laws as the elk, the same mathematical equations. Life will grant us no exception in this regard. We are vulnerable to our own appetite.

Before I close this letter, Billy, I want you to know how sorry I am about how difficult reading this must be for you. I wish it were different. I wish I were there to be your father. To walk with you through this. I really do.

I love you more than anything in the world,

Dad

*I harvested this version of the trolley problem from Sarah Bakewell’s article Clang Went the Trolley ‘Would You Kill the Fat Man?’ and ‘The Trolley Problem’, published November 22, 2013, in The New York Times.

The post Is it Probable that We Will Voluntarily Bring the Growth Rate of the Human Population to Zero? appeared first on The Old Man.

Is It Probable That The Human Population Will Stop Doubling Before Collapsing?

Any population that is growing will eventually double. Given the biological and psychological drives of the human species, which is more probable: that humans will voluntarily bring our own population growth rate to zero (or below) or that the eventuality of zero growth will be forced upon the species?

Any population that is growing will eventually double. Given the biological and psychological drives of the human species, which is more probable: that humans will voluntarily bring our own population growth rate to zero (or below) or that the eventuality of zero growth will be forced upon the species?

Let us assume, for the sake of this thought experiment, that the probability of zero growth being forced upon the human species by the natural laws of the biome is so great as to make the voluntary drop in the species’ growth rate seem not only unlikely but quite fantastic.

If we are to assume that humans are unlikely to collectively reduce population growth to a rate below zero, then the following moral problem becomes relevant.

Most of us have heard of the dilemma: You are walking near a trolley-car track when you notice five people tied to it in a row. The next instant, you see a trolley hurtling toward them, out of control. A signal lever is within your reach; if you pull it, you can divert the runaway trolley down a side track, saving the five — but killing another person, who is tied to that spur.*

Which is the correct choice? In surveys, most people, 90%, opt to pull the lever, choosing one death instead of five.

To make the question more interesting philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson presented The Fat Man version:

As before, a trolley is hurtling down a track towards five people. You are on a bridge under which it will pass, and you can stop it by dropping a heavy weight in front of it. As it happens, there is a very fat man next to you–your only way to stop the trolley is to push him over the bridge and onto the track, killing him to save five. Should you proceed?

Although most people are willing to pull the lever in survey questions, very few can see themselves pushing the fat man. The numbers of lives at stake are the same in both scenarios, so why do people feel more comfortable pulling the lever than pushing the man?

The thought experiment is a useful tool in examining our morality. Ethicists tend to boil the dilemma down to this: we can act on a rational and utilitarian calculus, intentionally killing one to save five; or we can respect the subrational instinct that makes us recoil at the thought of pushing a man to his death, choosing not to act, thus allowing the avoidable death of the five.

[image error]Wanting to explore the dilemma further, I fleshed out the trolley problem in my literary thriller Patriarch Run. The story assumes a scenario in which the exponential growth of the human population threatens the extinction of the species. One man, Jack Erikson, has an opportunity to stop the unfolding ecological crisis, but to do so he must sacrifice even his own family. Depending on how you choose to solve the trolley problem, Jack is either the villain or the protagonist of the novel.

Jack tries to explain himself to his son in the letter below:

Billy,

I want you to know that I love humanity. And even more than that I love life. I want to preserve both.

When you were six years old, Billy, you asked me if I hated the elk.

“No,” I told you, “I love them.”

You looked me straight in the eye and said, “Then why do you always want to kill them?”

“I don’t always want to kill them,” I explained. I took you into my arms and I carried you to the window where we could see the forest and I told you, “I hunt them in the fall because it’s good for them and it’s good for our family.”

You didn’t let me off the hook. You asked me to put you down. You wanted to know how it was good for the elk to be killed.

It was a good question. You’ve always had a penetrating mind.

I told you that there were no more wolves in Colorado, only the ones that have snuck back into these mountains, and there weren’t enough of those, not yet, to keep the elk herds in balance.

I asked you who was left to prey on the elk?

You didn’t have an answer. There are no more brown bears in our mountains and the lions here prefer to eat the deer.

That was all you needed. At that point you understood.

But let me write this anyway, let me write it just to see the words on the page, the idea. I’ll write it for me.

Elk reproduce at a robust rate. Without predators to keep them in check the population would swell and the herds would destroy their habitat. Once their habitat was destroyed the elk, in turn, would starve. There simply wouldn’t be enough food to feed them all.

Given our choice to remove their natural predator it would be cruel not to hunt the elk because harvesting a limited number preserves the whole. In the end culling the herd saves lives.

We accept this as a biological truth, I think, that everything has to be kept in balance. The wolves are the keepers of the elk just as the elk are the keepers of the grass. At six years old you understood this. In the absence of the wolf the hunter must keep the elk. The hunter does this to also feed his family and to keep the grass because he understands that without the grass there would be no elk.

That’s what life is. We keep each other.

Our grocery stores, perhaps, have allowed some of us to forget about the simplest of all truths. That we keep each other. People who only eat the meat that is butchered for them have no appreciation for the consequence of that feast. In that sense, they have lost contact with reality.

The chasm between our own understanding of ourselves and biological reality can be illustrated in the following question, where is the wolf?

The wolf is all but exterminated. Why? Those who want to exterminate the wolf want to do so because the wolf competes with humanity for resources.

In the effort to make ourselves more secure we have exterminated our competition, those who would prey on us along with those who would compete with us. Thousands of years ago, on the scale of a few million human beings trying to make it in the world, the strategy made sense for our species because the human population was fragile.

It makes sense to eliminate the competition, to kill the wolf, today only if the lens is focused on the individual. If the harvest of an elk is detrimental to the individual elk but beneficial to the species, how can it be any different with a human being? The truth is that human beings need predators. Because of our birth rate, like the elk, we need strong competition to survive. This is a mathematical fact.

The overwhelming success of our strategy of extermination has dramatically augmented the scale of its implementation, resulting in a lack of balance.

I’ll try not to be pedantic but a little math will help to contextualize what it is I mean by balance. The growth of the human population as I write is estimated to be 1.3% per year. At the current rate of growth the population will double every fifty-three years. Six to twelve, twelve to twenty-four billion human beings in a century. To put those twenty-four billion people in perspective, the world’s population a hundred years ago was one point six billion.

Unfortunately, the resources required to sustain our civilization are not growing at the same rate as the human population. The United Nations estimates that 15% of the population goes hungry today. That’s nearly a billion people. The balance is off.

Although most people accept the concept of ecological balance they are attracted to it only in the abstract, in a Disneyesk, bloodless form.

Balance requires death, killing. This concept is missing from our current understanding of humanity’s place in the world. Our population is kept from growing out of balance as long as those who hunger for us eat. All one has to do is pay attention to understand that is how life works. The failure to understand this is a symptom of our cultural disengagement from reality.

Whereas, reality does not depend on our acknowledgement of it, it won’t deactivate its consequences because we do not recognize them.

What happens as the human population swells? Its hunger swells. And, like every other species, it satiates its hunger.

Because we are more capable than the elk we can exterminate the organisms that compete with us for resources, weeds, fungi, insects, and grow our own food supply. And rather than exhaust our supply of food when faced with a swelling population we can expand food production and satiate the hunger. But that expansion has consequences. The elk feeds by ripping the grass with its teeth. Rather than consume the surrounding habitat with our jaws we consume the habitat with our cities and our farms.

Where is the pressure, the competition, the predator to check human civilization?

Due to our ability to adapt to the radical alterations we ourselves are making to our habitat the human timeline for uncontrolled, exponential population growth is more expansive than that of the elk’s but an expanded timeline is not an infinite timeline. The result of an unchecked, exponential growth in population is always the same.

Starvation. Because we have been so successful at exterminating our competition, a wolf will be provided for us. This wolf will come in the form of our own hunger.

There will be balance.

I’ve heard it argued that technology will change this. That there will be a human exception. That we can think our way out of this natural law. But that denial, the denial of the most fundamental law of biology, will only exacerbate the inevitable consequence. We do have an incredible gift in our ability to create. But as powerful as our minds are they are housed in our animal bodies, bodies that require sustenance to survive, bodies that are hardwired to reproduce. It is true that technology has stretched the breaking point but it has not and it cannot do away with it. The law remains constant. The result of an unchecked, exponential growth in population is always the same.

Nature forces balance.

The only variable to the law is scale. Because the elk’s impact is, in the grand scheme of things, small, if the population of its herds were to swell then collapse today the ecological damage could be repaired within a few generations. The same cannot be said of humanity’s global biological impact. As a matter of fact, with the six billion hungry humans who inhabit it today it is hard to imagine a species affecting the planet on a wider scale. Unless you were to consider the twelve billion who will inhabit it tomorrow or the twenty-four billion after that.

There will be a collapse. I think we all know this. Somehow we sense it. This is true for every part of the world to which I’ve traveled. People see it coming. Yet as a culture we suppress that knowledge, like the knowledge of the inevitability of our own death. Although suppressed the awareness spills out of our cultural-subconscious like a collective nightmare. You see this in the form of our post-apocalyptic art, our entertainment.

I wish it were different. That we could discuss the problem openly. But the subject of ecological balance in the context of human beings remains taboo. So when one does speak the truth, when one speaks about our need for the wolf, it sounds radical.

However, give it time to sink in and the truth of the matter will become inescapable.

I understand that decisive action has the appearance of cruelty. However, history tells us that it is decidedly more cruel to do nothing. The number of deaths from starvation has grown exponentially with the overall population. For example, the number of people without enough to eat in the world today is equal to the entire human population of 1810.

What does the future hold? If the number of hungry people doubles with the overall population, at the current rate of growth, 1.3%, there will be two billion hungry people in fifty-three years, four billion hungry people in a hundred and six years. How long will it take before the number of people suffering from starvation grows larger than the total number of people alive on the earth today?

Moreover, the problem reaches far beyond human suffering. To do nothing is to preside over the next mass extinction.

The growth rate of the human population will drop below zero. That is certain. The remaining question is one of scale. How catastrophic will the collapse be? That is up to us. That is up to me. The sooner the population is restored to balance the gentler, the more humane will be the collapse.

That, in a nutshell, is my job. To save lives. Just as I kept the elk I have been given an opportunity to be humanity’s keeper.

Why are we now comfortable with that ethic in its application to the elk but not in its application to human beings?

Because we have been disengaged from reality.

A paradigm shift, especially for those uninitiated to the trauma, can be unsettling emotionally. And in my experience the human condition does not allow for the intellect to move forward unless the emotional needs of a person are met. That is to say, unless the person feels safe. Which is difficult, or impossible, to achieve when under threat.

I realize that it is difficult to imagine a reality more threatening than the one I am now presenting.

I understand why this is so hard to accept. I’m afraid that when it comes down to it human beings reproduce, eat and starve just like every other animal. The belief of human exceptionalism in this regard is a blinding myth. Perhaps that false belief is why the truth is so painful to us. To be clear, I am not suggesting that an elk’s life is as valuable as a human’s. To me, it is not. I am only stating that humanity is governed by the same biological laws as the elk, the same mathematical equations. Life will grant us no exception in this regard. We are vulnerable to our own appetite.

Before I close this letter, Billy, I want you to know how sorry I am about how difficult reading this must be for you. I wish it were different. I wish I were there to be your father. To walk with you through this. I really do.

I love you more than anything in the world,

Dad

*I harvested this version of the trolley problem from Sarah Bakewell’s article Clang Went the Trolley ‘Would You Kill the Fat Man?’ and ‘The Trolley Problem’, published November 22, 2013, in The New York Times.

The post Is It Probable That The Human Population Will Stop Doubling Before Collapsing? appeared first on The Old Man.

September 21, 2014

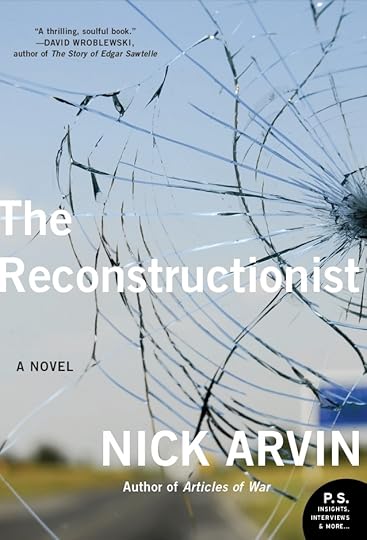

The Reconstructionist by Nick Arvin

THE RECONSTRUCTIONIST by Nick Arvin is an engineer’s thoughtful unfolding of the mundane: through the author’s insight and remarkable attention to detail, the story makes the ordinary extraordinary.

THE RECONSTRUCTIONIST by Nick Arvin is an engineer’s thoughtful unfolding of the mundane: through the author’s insight and remarkable attention to detail, the story makes the ordinary extraordinary.

In a word, it’s a novel about accidents–an examination of choices the average reader takes for granted.

After this story, a car will never look the same to me. As Boggs teaches the young Ellis Barstow how to reconstruct automobile accidents with an engineer’s methodical calculations, the reader learns enough about the physical forces at play on the roadway along with the fragility of the human body, in the face of those forces, to hesitate before turning the ignition.

Boggs also makes it clear that driving is a choice of great philosophical and moral import. A choice most of us take for granted.

I think about this story every time I drive. And not just about the physical danger posed by the nearby semis and texting motorists, but I approach my car now with a curiosity and a wonder I didn’t know before. My car has become a manifestation of something as mystical and as concrete as consequence.

The story reminds us that we are not victims. That we are always making choices. Every time we choose to drive we open an algorithm of probabilities. Those probabilities are eventually actualized into the form of consequence, some of which we expect and some of which surprise us.

It has been said by great thinkers that all there is, that all we are, that the only explanation to anything is simply that: consequence. Every action is final and followed by a perpetuity of unforeseen, unintended consequences.

To turn my ignition switch is to remind myself of that. That I am consequence. That after me, consequence will continue on.

The narrative becomes ironic when Ellis is confronted with the accident he creates for his own life. In the end, he loses a good friend, a hard to find treasure in this world, willingly exchanging that rare friendship for a miserable romance. The reader sees it coming, that accident, and is helpless to protect him.

Are our own lives any different? Aren’t they usually avoidable, the wrecks we make of ourselves and the ones we love?

In this sense, the story is about responsibility. Although I cannot control the eventualities of all my choices, I can live my life more aware of the choices I am making.

The post The Reconstructionist by Nick Arvin appeared first on The Old Man.

Is It Probable That The Human Population Will Stop Doubling Before Collapsing?

Any population that is growing will eventually double. Given the biological and psychological drives of the human species, which is more probable: that humans will voluntarily bring our own population growth rate to zero (or below) or that the eventuality of zero growth will be forced upon the species?

Any population that is growing will eventually double. Given the biological and psychological drives of the human species, which is more probable: that humans will voluntarily bring our own population growth rate to zero (or below) or that the eventuality of zero growth will be forced upon the species?

Let us assume, for the sake of this thought experiment, that the probability of zero growth being forced upon the human species by the natural laws of the biome is so great as to make the voluntary drop in the species’ growth rate seem not only unlikely but quite fantastic.

If we are to assume that humans are unlikely to collectively reduce population growth to a rate below zero, then the following moral problem becomes relevant.

Most of us have heard of the dilemma: You are walking near a trolley-car track when you notice five people tied to it in a row. The next instant, you see a trolley hurtling toward them, out of control. A signal lever is within your reach; if you pull it, you can divert the runaway trolley down a side track, saving the five — but killing another person, who is tied to that spur.*

Which is the correct choice? In surveys, most people, 90%, opt to pull the lever, choosing one death instead of five.

To make the question more interesting philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson presented The Fat Man version:

As before, a trolley is hurtling down a track towards five people. You are on a bridge under which it will pass, and you can stop it by dropping a heavy weight in front of it. As it happens, there is a very fat man next to you–your only way to stop the trolley is to push him over the bridge and onto the track, killing him to save five. Should you proceed?

Although most people are willing to pull the lever in survey questions, very few can see themselves pushing the fat man. The numbers of lives at stake are the same in both scenarios, so why do people feel more comfortable pulling the lever than pushing the man?

The thought experiment is a useful tool in examining our morality. Ethicists tend to boil the dilemma down to this: we can act on a rational and utilitarian calculus, intentionally killing one to save five; or we can respect the subrational instinct that makes us recoil at the thought of pushing a man to his death, choosing not to act, thus allowing the avoidable death of the five.

[image error]Wanting to explore the dilemma further, I fleshed out the trolley problem in my literary thriller Patriarch Run. The story assumes a scenario in which the exponential growth of the human population threatens the extinction of the species. One man, Jack Erikson, has an opportunity to stop the unfolding ecological crisis, but to do so he must sacrifice even his own family. Depending on how you choose to solve the trolley problem, Jack is either the villain or the protagonist of the novel.

Jack tries to explain himself to his son in the letter below:

Billy,

I want you to know that I love humanity. And even more than that I love life. I want to preserve both.

When you were six years old, Billy, you asked me if I hated the elk.

“No,” I told you, “I love them.”

You looked me straight in the eye and said, “Then why do you always want to kill them?”

“I don’t always want to kill them,” I explained. I took you into my arms and I carried you to the window where we could see the forest and I told you, “I hunt them in the fall because it’s good for them and it’s good for our family.”

You didn’t let me off the hook. You asked me to put you down. You wanted to know how it was good for the elk to be killed.

It was a good question. You’ve always had a penetrating mind.

I told you that there were no more wolves in Colorado, only the ones that have snuck back into these mountains, and there weren’t enough of those, not yet, to keep the elk herds in balance.

I asked you who was left to prey on the elk?

You didn’t have an answer. There are no more brown bears in our mountains and the lions here prefer to eat the deer.

That was all you needed. At that point you understood.

But let me write this anyway, let me write it just to see the words on the page, the idea. I’ll write it for me.

Elk reproduce at a robust rate. Without predators to keep them in check the population would swell and the herds would destroy their habitat. Once their habitat was destroyed the elk, in turn, would starve. There simply wouldn’t be enough food to feed them all.

Given our choice to remove their natural predator it would be cruel not to hunt the elk because harvesting a limited number preserves the whole. In the end culling the herd saves lives.

We accept this as a biological truth, I think, that everything has to be kept in balance. The wolves are the keepers of the elk just as the elk are the keepers of the grass. At six years old you understood this. In the absence of the wolf the hunter must keep the elk. The hunter does this to also feed his family and to keep the grass because he understands that without the grass there would be no elk.

That’s what life is. We keep each other.

Our grocery stores, perhaps, have allowed some of us to forget about the simplest of all truths. That we keep each other. People who only eat the meat that is butchered for them have no appreciation for the consequence of that feast. In that sense, they have lost contact with reality.

The chasm between our own understanding of ourselves and biological reality can be illustrated in the following question, where is the wolf?

The wolf is all but exterminated. Why? Those who want to exterminate the wolf want to do so because the wolf competes with humanity for resources.

In the effort to make ourselves more secure we have exterminated our competition, those who would prey on us along with those who would compete with us. Thousands of years ago, on the scale of a few million human beings trying to make it in the world, the strategy made sense for our species because the human population was fragile.

It makes sense to eliminate the competition, to kill the wolf, today only if the lens is focused on the individual. If the harvest of an elk is detrimental to the individual elk but beneficial to the species, how can it be any different with a human being? The truth is that human beings need predators. Because of our birth rate, like the elk, we need strong competition to survive. This is a mathematical fact.

The overwhelming success of our strategy of extermination has dramatically augmented the scale of its implementation, resulting in a lack of balance.

I’ll try not to be pedantic but a little math will help to contextualize what it is I mean by balance. The growth of the human population as I write is estimated to be 1.3% per year. At the current rate of growth the population will double every fifty-three years. Six to twelve, twelve to twenty-four billion human beings in a century. To put those twenty-four billion people in perspective, the world’s population a hundred years ago was one point six billion.

Unfortunately, the resources required to sustain our civilization are not growing at the same rate as the human population. The United Nations estimates that 15% of the population goes hungry today. That’s nearly a billion people. The balance is off.

Although most people accept the concept of ecological balance they are attracted to it only in the abstract, in a Disneyesk, bloodless form.

Balance requires death, killing. This concept is missing from our current understanding of humanity’s place in the world. Our population is kept from growing out of balance as long as those who hunger for us eat. All one has to do is pay attention to understand that is how life works. The failure to understand this is a symptom of our cultural disengagement from reality.

Whereas, reality does not depend on our acknowledgement of it, it won’t deactivate its consequences because we do not recognize them.

What happens as the human population swells? Its hunger swells. And, like every other species, it satiates its hunger.

Because we are more capable than the elk we can exterminate the organisms that compete with us for resources, weeds, fungi, insects, and grow our own food supply. And rather than exhaust our supply of food when faced with a swelling population we can expand food production and satiate the hunger. But that expansion has consequences. The elk feeds by ripping the grass with its teeth. Rather than consume the surrounding habitat with our jaws we consume the habitat with our cities and our farms.

Where is the pressure, the competition, the predator to check human civilization?

Due to our ability to adapt to the radical alterations we ourselves are making to our habitat the human timeline for uncontrolled, exponential population growth is more expansive than that of the elk’s but an expanded timeline is not an infinite timeline. The result of an unchecked, exponential growth in population is always the same.

Starvation. Because we have been so successful at exterminating our competition, a wolf will be provided for us. This wolf will come in the form of our own hunger.

There will be balance.

I’ve heard it argued that technology will change this. That there will be a human exception. That we can think our way out of this natural law. But that denial, the denial of the most fundamental law of biology, will only exacerbate the inevitable consequence. We do have an incredible gift in our ability to create. But as powerful as our minds are they are housed in our animal bodies, bodies that require sustenance to survive, bodies that are hardwired to reproduce. It is true that technology has stretched the breaking point but it has not and it cannot do away with it. The law remains constant. The result of an unchecked, exponential growth in population is always the same.

Nature forces balance.

The only variable to the law is scale. Because the elk’s impact is, in the grand scheme of things, small, if the population of its herds were to swell then collapse today the ecological damage could be repaired within a few generations. The same cannot be said of humanity’s global biological impact. As a matter of fact, with the six billion hungry humans who inhabit it today it is hard to imagine a species affecting the planet on a wider scale. Unless you were to consider the twelve billion who will inhabit it tomorrow or the twenty-four billion after that.

There will be a collapse. I think we all know this. Somehow we sense it. This is true for every part of the world to which I’ve traveled. People see it coming. Yet as a culture we suppress that knowledge, like the knowledge of the inevitability of our own death. Although suppressed the awareness spills out of our cultural-subconscious like a collective nightmare. You see this in the form of our post-apocalyptic art, our entertainment.

I wish it were different. That we could discuss the problem openly. But the subject of ecological balance in the context of human beings remains taboo. So when one does speak the truth, when one speaks about our need for the wolf, it sounds radical.

However, give it time to sink in and the truth of the matter will become inescapable.

I understand that decisive action has the appearance of cruelty. However, history tells us that it is decidedly more cruel to do nothing. The number of deaths from starvation has grown exponentially with the overall population. For example, the number of people without enough to eat in the world today is equal to the entire human population of 1810.

What does the future hold? If the number of hungry people doubles with the overall population, at the current rate of growth, 1.3%, there will be two billion hungry people in fifty-three years, four billion hungry people in a hundred and six years. How long will it take before the number of people suffering from starvation grows larger than the total number of people alive on the earth today?

Moreover, the problem reaches far beyond human suffering. To do nothing is to preside over the next mass extinction.

The growth rate of the human population will drop below zero. That is certain. The remaining question is one of scale. How catastrophic will the collapse be? That is up to us. That is up to me. The sooner the population is restored to balance the gentler, the more humane will be the collapse.

That, in a nutshell, is my job. To save lives. Just as I kept the elk I have been given an opportunity to be humanity’s keeper.

Why are we now comfortable with that ethic in its application to the elk but not in its application to human beings?

Because we have been disengaged from reality.

A paradigm shift, especially for those uninitiated to the trauma, can be unsettling emotionally. And in my experience the human condition does not allow for the intellect to move forward unless the emotional needs of a person are met. That is to say, unless the person feels safe. Which is difficult, or impossible, to achieve when under threat.

I realize that it is difficult to imagine a reality more threatening than the one I am now presenting.

I understand why this is so hard to accept. I’m afraid that when it comes down to it human beings reproduce, eat and starve just like every other animal. The belief of human exceptionalism in this regard is a blinding myth. Perhaps that false belief is why the truth is so painful to us. To be clear, I am not suggesting that an elk’s life is as valuable as a human’s. To me, it is not. I am only stating that humanity is governed by the same biological laws as the elk, the same mathematical equations. Life will grant us no exception in this regard. We are vulnerable to our own appetite.

Before I close this letter, Billy, I want you to know how sorry I am about how difficult reading this must be for you. I wish it were different. I wish I were there to be your father. To walk with you through this. I really do.

I love you more than anything in the world,

Dad

*I harvested this version of the trolley problem from Sarah Bakewell’s article Clang Went the Trolley ‘Would You Kill the Fat Man?’ and ‘The Trolley Problem’, published November 22, 2013, in The New York Times.

The post Is It Probable That The Human Population Will Stop Doubling Before Collapsing? appeared first on The Old Man.

The Trolley Problem: Is It Moral To Kill Billions To Save The Human Species?

Most of us have heard of the dilemma: You are walking near a trolley-car track when you notice five people tied to it in a row. The next instant, you see a trolley hurtling toward them, out of control. A signal lever is within your reach; if you pull it, you can divert the runaway trolley down a side track, saving the five — but killing another person, who is tied to that spur.*

Most of us have heard of the dilemma: You are walking near a trolley-car track when you notice five people tied to it in a row. The next instant, you see a trolley hurtling toward them, out of control. A signal lever is within your reach; if you pull it, you can divert the runaway trolley down a side track, saving the five — but killing another person, who is tied to that spur.*

Which is the correct choice? In surveys, most people, 90%, opt to pull the lever, choosing one death instead of five.

To make the question more interesting philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson presented The Fat Man version:

As before, a trolley is hurtling down a track towards five people. You are on a bridge under which it will pass, and you can stop it by dropping a heavy weight in front of it. As it happens, there is a very fat man next to you–your only way to stop the trolley is to push him over the bridge and onto the track, killing him to save five. Should you proceed?

Although most people are willing to pull the lever in survey questions, very few can see themselves pushing the fat man. The numbers of lives at stake are the same in both scenarios, so why do people feel more comfortable pulling the lever than pushing the man?

The thought experiment is a useful tool in examining our morality. Ethicists tend to boil the dilemma down to this: we can act on a rational and utilitarian calculus, intentionally killing one to save five; or we can respect the subrational instinct that makes us recoil at the thought of pushing a man to his death, choosing not to act, thus allowing the avoidable death of the five.

[image error]Wanting to explore the dilemma further, I fleshed out the trolley problem in my literary thriller Patriarch Run. The story presents a scenario in which the exponential growth of the human population threatens the extinction of the species. One man, Jack Erikson, has an opportunity to stop the unfolding ecological crisis, but to do so he must sacrifice even his own family. Depending on how you choose to solve the trolley problem, Jack is either the villain or the protagonist of the novel.

Jack tries to explain himself to his son in the letter below:

Billy,

I want you to know that I love humanity. And even more than that I love life. I want to preserve both.

When you were six years old, Billy, you asked me if I hated the elk.

“No,” I told you, “I love them.”

You looked me straight in the eye and said, “Then why do you always want to kill them?”

“I don’t always want to kill them,” I explained. I took you into my arms and I carried you to the window where we could see the forest and I told you, “I hunt them in the fall because it’s good for them and it’s good for our family.”

You didn’t let me off the hook. You asked me to put you down. You wanted to know how it was good for the elk to be killed.

It was a good question. You’ve always had a penetrating mind.

I told you that there were no more wolves in Colorado, only the ones that have snuck back into these mountains, and there weren’t enough of those, not yet, to keep the elk herds in balance.

I asked you who was left to prey on the elk?

You didn’t have an answer. There are no more brown bears in our mountains and the lions here prefer to eat the deer.

That was all you needed. At that point you understood.

But let me write this anyway, let me write it just to see the words on the page, the idea. I’ll write it for me.

Elk reproduce at a robust rate. Without predators to keep them in check the population would swell and the herds would destroy their habitat. Once their habitat was destroyed the elk, in turn, would starve. There simply wouldn’t be enough food to feed them all.

Given our choice to remove their natural predator it would be cruel not to hunt the elk because harvesting a limited number preserves the whole. In the end culling the herd saves lives.

We accept this as a biological truth, I think, that everything has to be kept in balance. The wolves are the keepers of the elk just as the elk are the keepers of the grass. At six years old you understood this. In the absence of the wolf the hunter must keep the elk. The hunter does this to also feed his family and to keep the grass because he understands that without the grass there would be no elk.

That’s what life is. We keep each other.

Our grocery stores, perhaps, have allowed some of us to forget about the simplest of all truths. That we keep each other. People who only eat the meat that is butchered for them have no appreciation for the consequence of that feast. In that sense, they have lost contact with reality.

The chasm between our own understanding of ourselves and biological reality can be illustrated in the following question, where is the wolf?

The wolf is all but exterminated. Why? Those who want to exterminate the wolf want to do so because the wolf competes with humanity for resources.

In the effort to make ourselves more secure we have exterminated our competition, those who would prey on us along with those who would compete with us. Thousands of years ago, on the scale of a few million human beings trying to make it in the world, the strategy made sense for our species because the human population was fragile.