Benjamin Dancer's Blog, page 11

August 31, 2014

Theft by BK Loren

THEFT by BK Loren offers the reader several things. A good story. I found myself turning pages, frequently surprised by the way things panned out.

THEFT by BK Loren offers the reader several things. A good story. I found myself turning pages, frequently surprised by the way things panned out.

The story also offers us an insightful point of view on humanity’s role in the ecosystem. The major characters, each in their own way, give their lives to the land–to something bigger than themselves.

THEFT is a thoughtful narrative. The themes of the book, namely conservation, are controversial in our society, as the conversation often pits the needs of human beings against the needs of other species–such as the wolf. THEFT offers a meaningful contribution to the dialogue by suggesting that this framework might be a false dichotomy. The story suggests that without the wolf (that is to say, without the other species), the land cannot be well. And if the land, meaning the ecosystem, is not well, then neither can we be well.

Above all, the story is about healing. The land, yes. But the brokenness that THEFT explores has a much wider lens. It is as if the broken nations, the broken families, the broken selves that are the subject of this narrative are but a symptom of a larger problem: things are out of balance.

The endangered Mexican grey wolf represents that lack of balance. The protagonist, Willa, is desperately trying to save the species from being hunted to extinction. Willa also tries to save her own mother from Parkinson’s disease, she tires to save her estranged brother–and, most importantly, she works to save herself.

The environmental themes of the story are the setting for this larger event: Willa’s attempt to make sense of her traumatic childhood, of her shattered family, of her own need for connection to other human beings. In this sense, the story is resolved not once the fates of those she intended to rescue are settled, but when Willa finally embraces love–represented by Christina. Something, for good reason, she had been afraid of.

The environmental themes of the story are the setting for this larger event: Willa’s attempt to make sense of her traumatic childhood, of her shattered family, of her own need for connection to other human beings. In this sense, the story is resolved not once the fates of those she intended to rescue are settled, but when Willa finally embraces love–represented by Christina. Something, for good reason, she had been afraid of.

The post Theft by BK Loren appeared first on The Old Man.

August 9, 2014

Washington Bombing–Deleted Scene

I always liked this scene–maybe because it was the first scene I wrote for PATRIARCH RUN. Because the scene birthed the rest of the story, it’s special to me. But it didn’t make the final cut.

Washington, D.C., Last Week

When he came to, he shut his eyes to alleviate the nausea.

The silence was ruptured by a horn blast.

Jack opened his eyes and saw the white, fluted columns of a courthouse. Pedestrians on the sidewalk.

His head was ponderous and difficult to turn.

A man in a black suit–a briefcase in his lap–was sitting beside him. The vehicle they were in was at a stoplight in heavy traffic. His tongue was stuck to the roof of his mouth. It felt swollen and chalky, as if he had ingested a narcotic. He sucked his teeth but could not swallow.

The mass of people huddled at the street corner began to cross the intersection. A pale-skinned man in a leather coat stayed behind. They made eye contact.

The left side of Jack’s head pulsed so violently from the drug the vision in that eye went white.

The SUV accelerated. Jack noticed the driver for the first time, the Ford Oval on the steering wheel. Then he bent forward and vomited between his knees. The man beside him in the backseat didn’t respond.

His attention was drawn through the crowd at the next intersection to a man talking on a black phone.

He tried to press his palm against the side of his head, but couldn’t.

A white van slowed to a stop beside him. The driver of the van had the same black phone against his ear. Beads of sweat dripped from the driver’s nose; his jaw muscles were knotted.

Jack leaned forward to get a better look. But the van’s door was now open, the driver gone.

Compelled by decades of training, he shouted, “Bomb.” The warning resonated with an unemotional authority he did not anticipate or comprehend.

The Ford he was in jumped forward, accelerating at full throttle into the heavy cross traffic. Tires screeched in the intersection. A white Civic swerved. He heard metal smashing metal. The Ford kept accelerating and punched the rear quarter panel of a blue Camry, pushed through the lanes and T-boned a silver Tahoe.

He was coughing and tried to sit up–but couldn’t. He couldn’t move his arms. Hit his head on the steering wheel and lay his cheek on the leather-trimmed door panel, in too much pain to curse.

He kept his eyes shut to stop the skewer of light from plunging into his brain.

Bursts of automatic rifle fire punctuated the wailing and screams of terror.

He allowed his right eye to squint–saw jagged glass in a window frame. He closed the eye. Slowly turned his head. Opened the eye again and saw black asphalt and shattered glass beneath him.

The Ford was on its side.

He put one knee on the asphalt, pressed his back against the roof and stooped, his feet in the broken-out window.

His hands were bound behind his back.

Eight rapid, semi-automatic pistol shots fired from close by were followed by the clinking of a steel magazine against the pavement. He heard the familiar snap of supersonic projectiles passing close to his head and saw in the roof three newly created pinholes of light.

He dropped, curled up on the broken glass–still coughing.

He couldn’t recall how it was he came to be in the vehicle. He didn’t know where the two men in suits had gone.

When the automatic rifle fire ceased, he kicked out what remained of the windshield.

He remembered the briefcase and squeezed into the backseat. The pistol shots were slower and more controlled than before. The combination briefcase was lying on the door. He used the sides of his feet to stand it upright between his ankles, dug his elbow into the leather-trimmed seat for balance, squatted–his hands behind his back–and picked it up.

He threw himself into the front seat and stepped out the windshield.

Civilians were calling for help. Others were crouching. A man prone on the asphalt, his hands shielding his head. From every direction came howls of pain. The air was black with smoke. Vehicles on fire.

He found the driver of the Ford Expedition–bullet holes in his face, neck and chest. Gray ashes speckled his cheek and black suit.

The Camry was upside down, on top of another sedan. The windows shattered, paint blackened, three of its tires ablaze like torches over the carnage.

A man thrashed his arms: his hair, back and sleeves on fire. A teenage girl ran out from behind the barricade of an overturned Prius, knocked the burning man down and beat the flames with her cotton trench coat. Another rifle burst drove her to her belly. She lay on him, smothering the flames.

He heard sirens. Everyone was coughing.

By the time he located the source of the rifle fire through the black plumes of soot and smoke, the rifleman was dead, splayed over the yellow hood of a Dodge Charger.

It was the man he saw on the phone at the intersection.

He searched for the suit who was beside him in the Expedition. An old woman, face covered in blood, sat rocking on the curb, hugging her chest. Gray ash fell from the smoke. Another man crawled toward the sidewalk, coughing, dragging his right arm–a splintered, white bone protruding from his pant leg.

He stepped forward to help the man then remembered the handcuffs on his wrists and looked around.

The keys, he was certain, were in the locked briefcase he was holding behind his back.

A fire truck, sounding its air horn, pressed through the clogged street.

Then he found him–the man from the backseat–laying prone in a pool of blood beside the burning Tahoe, a Colt Commander in his hand. By the position of the slide, he knew there was another round in the chamber. The pistol’s thumb safety was off, the hammer cocked, the man’s right hand was wrapped around the grip, his index finger still on the trigger.

He set the briefcase in the street and sat in a pool of the man’s blood. The blood was hot and soaked through his cotton pants. He eased the Colt out of the man’s hand. Stood, brought the weapon to his left side–where he could see the muzzle–held his breath to suppress the coughing and shot the brass lock on the briefcase.

Then he sat down–his back to the briefcase–opened the latch, twisted his neck to look inside and squeezed his eyes against a pulse of white pain.

The key hung against the interior wall.

The man in the black suit was moaning. He rolled him over, unbuttoned the suit jacket, seized the bloody, silk shirt in both fists and pulled the shirt apart. Buttons sprung from their threads. The man was going to die. He pressed his bare hands against the wounds.

The man coughed.

Blood misted his face. Sirens. Howls filled the street. The inconsolable wail of a mother. He wiped the man’s blood from his eyes, tore strips of silk from the shirt, wadded the fabric and plugged the holes in the man’s chest.

But the life–no matter how hard he pressed–welled up through his fingers.

The cries for help grew more insistent with the arrival of the first emergency crews.

The man in the suit was dead for minutes before he took his hands off his chest. He felt confused, stood and pushed a sticky palm into his temple.

Barely visible through the sooty smoke, a uniformed officer, his weapon drawn, was making his way toward the Expedition.

It was time to leave.

He pressed the magazine release, counted the two remaining .45 ACP cartridges, a third in the chamber. Four spent stainless-steel magazines lay in the blood. He slammed the nearly empty magazine home, put the Colt in his waistband, searched the dead man for spare magazines, for identification. Found nothing.

He staggered away from the approaching officer, past the yellow Charger. The OGA had a red hole above his ear. An M4 carbine lay at his feet.

The dizziness nearly overwhelmed him.

Whoever the man in the black suit was, he had known what he was doing. Laying prone in a pool of his own blood, he shot through the Charger’s rear driver’s-side window. The bullet passed through the cabin, exited through the roof–near the passenger-side windshield pillar–and struck the rifleman in the head: a target not in the shooter’s field of vision.

He staggered past the burning vehicles in which sat corpses–charred arms and grimacing faces–past emergency crews delivering aid to the shocked and bleeding, past ambulances and fire trucks, past approaching patrol cars and turned down the first street he came to.

The post Washington Bombing–Deleted Scene appeared first on The Old Man.

August 5, 2014

Stars Go Blue by Laura Pritchett

The novel reads quickly for three reasons: it’s suspenseful (a bit of a thriller), the reader is captivated by the characters and its lean. A number of things impress me about Laura Pritchett’s story. Let’s start with Ben, one of the protagonists.

The novel reads quickly for three reasons: it’s suspenseful (a bit of a thriller), the reader is captivated by the characters and its lean. A number of things impress me about Laura Pritchett’s story. Let’s start with Ben, one of the protagonists.

Ben wouldn’t be a man you’d notice on the street. He’s not somebody that would stand out. But because of the attentive focus of the narrative, the old man gets inside your heart and emerges as a hero, becomes somebody you wish you could know, have as a mentor.

Ben is suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. He has some important things to do before his diseased mind makes the mission impossible. So he’s fighting a superhuman battle. You find yourself pulling for him, against impossible odds. You want him to succeed, and the story draws it out of you, empathy for this old guy.

But here’s the kicker: the two things he is determined to accomplish are illicit. His objectives are firmly categorized as “bad” in our culture’s moral and legal codes. Some would say evil. Yet we pull for him to succeed.

That is a story!

The other protagonist is Ben’s wife, Renny. I should mention that the narrative is told from two points of view, Renny’s and Ben’s. We alternate chapters between them. This technique catalyzes two effects: the suspense of the thriller and the profound relationship the reader develops with each character.

Renny is not somebody most of us would like if we met her. She is as cold as the winter setting of this novel and cruel. Her motivation to be so shuttered is rooted in the past. Stars Go Blue is the third book in a trilogy. In a previous story Ben and Renny lost their daughter, and that tragedy drove the couple apart.

Renny is not somebody most of us would like if we met her. She is as cold as the winter setting of this novel and cruel. Her motivation to be so shuttered is rooted in the past. Stars Go Blue is the third book in a trilogy. In a previous story Ben and Renny lost their daughter, and that tragedy drove the couple apart.

I found myself wishing something for Renny: that she’d let her guard down and just accept and love herself. To her, everything is stupid, which is her favorite word. Renny’s contempt for herself drives her to pour the same emotion into everyone she loves. It’s heart breaking.

I found myself wishing something for Renny: that she’d let her guard down and just accept and love herself. To her, everything is stupid, which is her favorite word. Renny’s contempt for herself drives her to pour the same emotion into everyone she loves. It’s heart breaking.

Yet Pritchett manages to turn the table on the reader by putting Renny’s life in danger, by making her vulnerable, and suddenly we’re pulling for her, too.

There’s a third point of view from which we get to watch these people, the granddaughter’s. Jess is a great character. We’re introduced to her early on. We’re teased in a way, because she’s an instant favorite, but the lens is always a mile away from her. And we’re always wanting more.

You get the sense that Pritchett knew this about us when, in the end, she gives the reader some time with Jess. The novel closes with a satisfying chapter from her point of view.

There are some rich themes Pritchett addresses in this story. It would be impossible to discuss them without introducing spoilers, which are present below.

The setting is a ranch in Colorado. It’s winter. Icy and cold. And the climax takes place in a blizzard. Stars Go Blue is a bold end-of-life narrative. Pritchett does not flinch. Her directness, I think, will make readers squeamish. From the earliest pages, we are witnesses to ranch life. To birthing and killing. We see animals nurtured and we see them compassionately put down.

There is a juxtaposition which serves to compare the compassion with which the rancher offers the suffering animal at the end of its life to the lack of compassion with which we treat our own kind. It’s taboo to put down a suffering human being.

There are scenes presented in the narrative that most Americans have never contemplated. Scenes detailing where our food comes from. What it means to be alive and to eat and to be near the land. The book reveals the consequences of our appetites, of our lives, to the animals which feed us, which is not a commentary on food in this story, but on life itself.

There are wild things living on the ranch: the bald eagle, the owl, the aspens, the willows and the water. Wildness which the old man loves.

The old rancher is protective of the earth around him. It is his dying wish the that land be preserved, healed. It is a subtext, but it is there, like an accusation. There is something amiss in our civilization: that without protection the very thing that sustains us, the land, is in jeopardy.

The old man is no liberal, no environmentalist. The reader gets the sense that he wouldn’t be able to relate with that urban ethic. He’s a rancher who understands where life comes from. The balance necessary to sustain his family. He understands health in a way no one divorced from the land could.

The main thrust of the story is the damaged family. So the old man’s desire to heal the land also serves as a metaphor for another type of healing. There are a lifetime of scars accumulated in this book. Neither Ben nor Renny are very good at intimacy. That is evident in their relationships with their children and grandchildren. They are human beings, as flawed and as afraid as any of us. We get to see the consequences of their lack of development, the fruit it bears over a lifespan.

The theme of self-acceptance is played out through the female characters. Renny is loaded with self-contempt. It is the lens with which she views everyone around her. She sees fault first and protects her heart from further loss by believing that no one will come to a good end. This is played out in her expressed certainty that her granddaughter, Jess, will wind up addicted to drugs and pregnant. Which is ironic because Jess is the character in the story who has learned to love herself. Because she is comfortable with herself, she also loves her grandmother, accepts Renny for who she is.

The resolution to this tale about death (which is to say life), about the land, about family, about love–takes place in the spring, at Ben’s burial. The old man has accomplished his mission. He is a hero.

Ben’s heroism means that he has committed acts thought to be reprehensible by our society. However, the reader was with him when he committed those acts, wanted him to succeeded. In other words, the context of the old man’s life, our empathy for him, changed us, grew our own understanding of what it means to be human. Our own understanding of life and of death.

Jess walks us through all of that in the last chapter. We learn that, just as we suspected, she was protecting her grandfather all along. By being clandestine about it, she gave him his dignity. Jess is the embodiment of grace, of forgiveness and of self-acceptance.

Laura Pritchett

The story is going to make the reader sad. That’s just the way it is. But it would be a mistake to avoid it because of sorrow. Ben, knowing his mind is almost gone, writes a letter to his future self. It’s the most touching scene in the book. An act of compassion, of self-love that brought me to tears.

“You have been a good man. You have Alzheimer’s…Be brave. It’s been a good life…Everyone has to die, Ben. No life without death. And your time is now, and it’s OK.”

We’ve got to put our hearts in order. Stars Go Blue is a good story for that.

The post Stars Go Blue by Laura Pritchett appeared first on The Old Man.

August 3, 2014

Patriarch Run

Amazon is running a sale on my literary thriller PATRIARCH RUN. It's only $0.99! We're running a campaign to boost the book's ranking. Would you please consider purchasing the story? That would go a long way in supporting me as an author. Thank you.

Amazon is running a sale on my literary thriller PATRIARCH RUN. It's only $0.99! We're running a campaign to boost the book's ranking. Would you please consider purchasing the story? That would go a long way in supporting me as an author. Thank you.Here's a review:

5.0 out of 5 stars This World Is Hard On People, June 25, 2014

By

not a natural "Bob Bickel"

This review is from: Patriarch Run (Paperback)

The farther the reader gets into Benjamin Dancer's Patriarch Run the clearer it becomes that the author is not interested in writing just another science fiction suspense thriller that entertains readers but teaches them little or nothing of value. Dancer's novel is written by someone who has thought deeply and seriously about the story he wants to tell, and he's not afraid of taking chances, both stylistically and thematically, in telling it. There is more than enough action, suspense, and brain-taxing mystery to satisfy even readers most demanding of forceful diversion and head-spinning adventure and misadventure. However, from the outset it's abundantly clear that an author with Dancer's deeply tragic sense of life is not going to be satisfied with a novel that provides high-spirited and satisfying enjoyment, leaving the reader maybe a bit drained, but satisfied and untroubled.

Instead, Patriarch Run departs sharply from the usual import of even the most gratifying and well-crafted reader-friendly fiction by forcing us to acknowledge painful truths, as well as the most compelling and important aspects of that which we cannot know. If we're honest with ourselves, when we're at our most deeply introspective we find little that consensus would judge to be noble. We often discover that we have good reason to question our motives and even doubt our fundamental decency. Patriarch Run forces us to see this by lifting the veils of narrow self-interest and perhaps unavoidable naivete. Characters who are unambiguously heroic are hard to find in Patriarch Run, and for the most part they know it. Nevertheless, Dancer shows us that if we had the breadth of knowledge and keenness of vision to see people in the total context that gives rise to their lives, the imperfections that we find in ourselves and others would be explicable as unavoidable outcomes of all that goes into making us distinctive human beings. This kind of vision, however, is not something that comes with living in our mundane world, even if we've briefly experienced a glimpse of a preternatural alternative under extraordinary circumstances.

Patriarch Run is suitably fraught with ambiguity and uncertainty. We meet characters whose commitment to a courageously patriotic life, something to which they give their all and repeatedly risk everything, learn that patriotism, as they have understood it, may set one on a fool's errand, one that causes harm and reinforces injustice rather than benefiting citizens at large. However compelling the evidence, this is a hazardous turn for an author to take in our hyper-politicized environment, especially when he finds a rough equivalence among self-promoting big governments throughout the world. It's to the author's credit that he knows that even good people with the most laudable objectives can't transform an impersonal organizational behemoth into something that we can stand by, proud and protected. Little wonder that deciding what is the right thing to do becomes so muddled in philosophical and practical difficulties in Patriarch Run. Who knows? Maybe the Neo-Malthusian catastrophe so ingeniously pursued by Jack, the father of the novel's protagonist, is the most humane way to go.

We all know that pain is a part of life, but Dancer's novel forces us to acknowledge it in inescapably personal ways that I found unnerving. The killing of a bison for what may or may not be a good reason, is such a commonplace sort of event in our carnivorous world that my almost tearful response to the head-shot death of the leader of the herd seems silly. But in Patriarch Run, death is not a remote abstraction, an unnoticed part of everyday life. It's real, painful, and deeply sad. The exchange of gunfire between Billy, the protagonist, and Jack is perfectly explicable in ways that all can see. But it dramatically emphasizes the heart-rending confusion that is an unavoidable part of life as we live it. It also illustrates the insane predicaments that can both unite and separate a father and son in a contemporary dialectic of kinship.

In a real sense, Billy has two fathers, one thoroughly admirable to the end, and the other a denatured victim of the world he sought to set right. It seems likely that if their roles had been reversed early on, they would have traded places, one becoming a contextually determined approximation of the other. Does Billy see this? And what will he make of it? Questions raised by this truly fine novel.

Source: www.amazon.com/review/R1P1IFRTQC7KXQ/...

August 1, 2014

150 Yard Shot With A Handgun?

A 150 yard shot with a handgun would be a remarkable accomplishment. So much so that one would be justified to be skeptical about such claims.

A 150 yard shot with a handgun would be a remarkable accomplishment. So much so that one would be justified to be skeptical about such claims.

There’s a scene in Patriarch Run in which the sheriff unloads a few cylinders from his Colt Python service revolver into a paper plate at 150 yards.

I thought it’d be worthwhile to describe how it is I came to write such a scene. Many, many moons ago I was reading “Hitting At 200 Yards With A Handgun”, an article written by a couple handloaders, Dan Keisey and Bill McConnell, and posted in the Tech Notes at Beartoothbullets.com.

The quick summary of their achievement is that Dan shoots a 5.25″ five-shot group at 200 yards, a 3.62″ five-shot group at 150 yards and a 1.97″ three-shot group at 100 yards. Dan’s revolver was topped with a 2.5X8 Leopold scope. That type of shooting is extraordinary. However, Bill took a more difficult path. He used iron sights to shoot an 8″ group at 200 yards and a 3.5″ group at 100 yards. Details about the loads and guns they used are available in their article.

I should point out a couple key differences between the article and my story. First, both shooters in the article used the .44 Magnum cartridge; whereas, the sheriff in my story uses the .357 Magnum cartridge. In terms of accuracy, the difference in cartridges is not very significant. Both cartridges are very accurate, especially when handloaded. Furthermore, the shooters in the article used longer barrels than the sheriff, which aids in accuracy. That being said, Bill states that the long-range groups from his 5.5″ barrel were just as good as the groups from his 7.5″ barrel, “With practice though the group fell into roughly the same size as with the longer barrel.”

What’s remarkable is that with a 5.5″ barrel and iron sights, Bill was able to shoot 8″ groups at 200 yards and 3.5″ groups at 100 yards.

Bill’s accomplishment inspired the scene in my story in which the sheriff uses a 4″ Colt Python (a revolver renowned for its accuracy) to shoot a paper plate, which would be about 9″ in diameter, at 150 yards. An easier task, in my estimation, than what Bill was able to accomplish.

Bill’s accomplishment inspired the scene in my story in which the sheriff uses a 4″ Colt Python (a revolver renowned for its accuracy) to shoot a paper plate, which would be about 9″ in diameter, at 150 yards. An easier task, in my estimation, than what Bill was able to accomplish.

The scene serves, among other things, to establish the sheriff as an authority with his firearm.

Here’s the Scene:

Billy, at ten years old, wanted to shoot that Winchester 1894 more than he wanted anything else in the world. He set five cans on five fence posts a full hour before the sheriff was due back. Paced off fifty yards, marked the spot with a line drawn by his boot heel and waited on the porch for the rest of the afternoon, until the sheriff’s car finally came up the drive.

“I take it you want to show me some shootin’.”

Billy loaded five cartridges into the magazine of the .22. “You reckon that’s fifty yards?”

The sheriff thought it was closer to sixty. “Looks like it to me.”

Billy shouldered the rifle and shot the first can off the fence. He levered in another round and did it four more times.

The sheriff put his hand on Billy’s shoulder. “I’d say that settles it.”

The next day he brought him a thousand .30-30 handloads. “This is a starter load. Shoot four cans out of five at seventy-five yards and I’ll heat it up a little.”

A month later, Billy shot another five cans off the fence.

“You think you’re ready for squirrels?”

“If you think so.”

The sheriff gave him a box of another thousand handloads. “This is a good load for squirrels. Just keep it away from the house. And it’s probably best not to talk about it with your mother.”

“Alright.”

“And you leave an Abert’s squirrel alone. He has a right to do as he pleases. Shoot the fox squirrels.”

They walked together behind the house.

“You’ll find, as you get older, people aren’t all that different than squirrels. There are those who sustain their habitat and those whose sole purpose is to destroy it.”

Billy had no idea what the sheriff meant by that, but he remembered the words.

By the time the boy harvested his first mule deer, he was shooting paper plates at a hundred and fifty yards with iron sights. The sheriff would watch his trigger pull, his jaw muscles, his eye lids.

“That’s it. Nice and smooth.”

Billy’d hit the plate with every round in the magazine. And the sheriff would pat him on the shoulder and say it again, “That’s the evidence of a disciplined mind.” Then he’d draw his service revolver, take Billy’s place on the bench and empty a few cylinders into the same paper plate.

The post 150 Yard Shot With A Handgun? appeared first on The Old Man.

July 26, 2014

Mothers and Daughters

I did an interview recently with Colleen O’Grady. Colleen has over 20 years experience as a licensed marriage and family therapist. She is also a mom in the trenches with her own teenage daughter. In order to help other parents, Colleen created the Power Your Parenting program, blog and book: a guide to help parents foster healthy relationships with their teens.

I did an interview recently with Colleen O’Grady. Colleen has over 20 years experience as a licensed marriage and family therapist. She is also a mom in the trenches with her own teenage daughter. In order to help other parents, Colleen created the Power Your Parenting program, blog and book: a guide to help parents foster healthy relationships with their teens.

Being a mother of a teenage daughter can be difficult. Colleen and I work with teenagers professionally. On the other hand, many parents are confronting, for the first time, issues we see every day. Which is why it takes a village. Those of us who work with adolescents have a lot to offer parents.

Our conversation focuses on the pervasive issue of sexting. The behavior starts earlier than most parents want to believe, and it involves many more kids than most people imagine. If you’re the parent of a teenager, you’ll want to listen to the podcast: Could Your Teenager be Sexting?

The issues we discuss in the podcast can be explored more fully in my article Sexting at School and in Colleen’s work. If you need help building honest and open communication with your teen go to poweryourparenting.com and sign up for Colleen‘s free ebook, 7 Ways to Help Your Relationship with Your Teenage Daughter (and Yourself).

The issues we discuss in the podcast can be explored more fully in my article Sexting at School and in Colleen’s work. If you need help building honest and open communication with your teen go to poweryourparenting.com and sign up for Colleen‘s free ebook, 7 Ways to Help Your Relationship with Your Teenage Daughter (and Yourself).

The post Mothers and Daughters appeared first on The Old Man.

July 21, 2014

James Franco’s Blood Meridian Film

I found this today. Thought you might like to see it: James Franco’s Blood Meridian Test

“In honor of Child of God’s release on August 1, I’m posting a 25-minute test I did for the film version of Blood Meridian…by Cormac McCarthy…” -James Franco

The post James Franco’s Blood Meridian Film appeared first on The Old Man.

Happy 81st birthday to Cormac McCarthy!

"He lay in the dark thinking of all the things he did not know about his father and he realised that the father he knew was all the father he would ever know."

--from ALL THE PRETTY HORSES by Cormac McCarthy, born on July 20, 1933

July 19, 2014

50 Coolest Authors of All Time

Cormac McCarthy, author of gag-thin favourites The Road and Blood Meridian used the same typewriter for almost 5o years. He used his Olivetti Lettera 32 to write nearly all of his fiction, screenplays, and correspondence from 1960 to 2009. In 2009 the typewriter was auctioned by Christies to benefit the Santa Fe Institute and sold to an unidentified American collector for $254,500, more than 10 times its estimate. McCarthy paid $20 for a replacement typewriter of the same model, but in newer condition and continues to use that to this day. We offer no more reasons, although there are hundreds, for why he's cool.

Cormac McCarthy, author of gag-thin favourites The Road and Blood Meridian used the same typewriter for almost 5o years. He used his Olivetti Lettera 32 to write nearly all of his fiction, screenplays, and correspondence from 1960 to 2009. In 2009 the typewriter was auctioned by Christies to benefit the Santa Fe Institute and sold to an unidentified American collector for $254,500, more than 10 times its estimate. McCarthy paid $20 for a replacement typewriter of the same model, but in newer condition and continues to use that to this day. We offer no more reasons, although there are hundreds, for why he's cool.From: http://shortlist.com/entertainment/bo...

July 16, 2014

Too Many People

A Goodreads friend just informed me that Dan Brown borrowed my idea for a story then published his a year before me. I guess I’ll forgive him and however many million books he’s sold.

A Goodreads friend just informed me that Dan Brown borrowed my idea for a story then published his a year before me. I guess I’ll forgive him and however many million books he’s sold.

For the record, though, I finished the first draft of PATRIARCH RUN in 2010.

Truth be told, the two stories have very little in common. Where they do intersect is at the premise that we are approaching an avoidable apocalypse.

There are simply too many people.

That fact must be the most underrated crisis of our time. I can’t think of an environmental dilemma that is not a symptom of that simple truth.

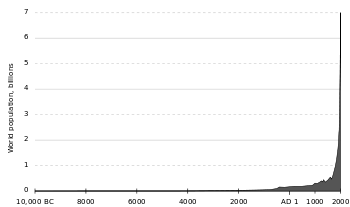

Let’s take a quick look at the math. It is estimated that the human population is growing at a relatively low rate: 1.14% per year. But as long as the population is growing, it doesn’t matter how low the rate is. The math tells us that a growing population will eventually double.

At the current growth rate, that will take about 61 years.

That’s not a liberal statement. It’s not a conservative statement. It’s a statement of fact.

Is there anyone who believes that 14 billion is a good number of people to have? What would it take to feed that many people?

Some might argue that through technology it will eventually become possible to feed 14 billion people, but I’ve yet to hear someone lead the cheer for that size of population.

Today there are about 1 million new people added to the ecosystem every five days. What would be the consequence of 14 billion people to the non-human members of that ecosystem?

It’s true that the growth rate of the human population is declining in some parts of Europe. Some people cite that fact as a dismissal of the overall problem. But it’s the overall problem that we have to face. In other words, it’s the planet-wide growth rate that matters–not a localized subset.

Right now, the planet-wide growth rate of the human population is pretty low: 1.14%. And that, by any scientific measure, is a crisis for just about every species on the planet, including our own.

There are plenty of good scientific studies that discuss the consequences of the growing human population on the ecosystem and how that unfolding catastrophe will eventually wind its way back to us. So I won’t dive into those details.

I’d like to get into this mind bender instead. The human population in 1900 was about 1.6 billion. In 2000 it was about 6 billion. And at the rate we’re growing right now, it’ll be 14 billion in 2075.

I’d like to get into this mind bender instead. The human population in 1900 was about 1.6 billion. In 2000 it was about 6 billion. And at the rate we’re growing right now, it’ll be 14 billion in 2075.

I have a hard time wrapping my mind around that. What get’s me is that the growth rates were low during the last century. The growth rate peaked in the 1960s at 2.2%.

Although the recent rates of growth seem low, they took us from 1.6 to 7 billion people quite quickly.

The takeaway for me is that a growing population always doubles. And that doubling happens a lot faster than people think.

One of my characters takes this math to heart, and his actions are extreme enough to warrant a story.

The post Too Many People appeared first on The Old Man.