Matt Rees's Blog, page 45

April 20, 2009

Krimis, polars, gialli: what crime novels are called around the world

Sometimes people talk about crime novels as though they were all the same. The sheer number of different names for variants of the crime novel proves that isn’t true.

Police procedural. Mystery novel. Thriller. Cosy. Exotic detective. Supernatural. I used to think there was little real difference, but then my UK publisher told me he wanted to change the title of my first novel “The Collaborator of Bethlehem.” He thought it sounded like a thriller (which men typically buy) and he wanted it to be clear that it was a mystery (so that women would buy it.) He changed the title in Britain to “The Bethlehem Murders.” I had to acknowledge that he was right: it sounds more like a mystery, doesn’t it.

And that’s only in English.

As I travel around to promote my books in different countries (I’m published in 22 countries these days), I’ve noticed that there are interesting variations on the names we use in English for crime novels. Some of them are quite entertaining, and some of them tell us something revealing about how the genre developed in that country.

Take Italy. Mystery novels there are called “gialli,” or yellows. That’s because traditionally the genre was published with a yellow cover. Even today the mystery shelves of Italian bookshops are largely yellow.

Color is the theme also in Spain, where crime novels are “novelas negras,” black novels. According to a source of mine on the literary desk of El Pais, the big Spanish newspaper, this harks back to the old “Serie noire” of French publisher Gallimard. That series introduced the crime novel to Spain. So noir, or black, became the identifying color for a crime novel.

A “roman noir,” black novel, is also one of the ways of referring to a crime novel in France, because of that Gallimard series. But the most common slang for a mystery in French is “un polar.” It’s a contraction of “roman policier,” police novel, and was first recorded in 1968. If you ask most French people to explain the origin of the word “polar,” they can’t tell you: the abbreviation has become so common, they’ve forgotten its rather simple derivation.

Germany (as well as the Scandinavian countries) calls a crime novel “ein Krimi,” short for the word Kriminelle, criminal. No surprise there. It’s a catch-all for thrillers and detective stories of all kinds.

There is, however, an amusing sub-genre in German. In English, the “cosy” refers to Miss Marple-type novels in which the detective is an amateur, usually a lady (not just a woman), probably an inhabitant of a quaint village, investigating a murder in a country house or a vicarage.

The Germans call these cosies “Häkel-Krimis“. Miriam Froitzheim, who works at my German publisher C.H. Beck Verlag in Munich, translates this as “Crochet Crime Novels.” Because, as she puts it, the detective “puts her crochet gear away to solve the murder.”

I’ll keep scouting for interesting ways of describing crime novels around the world. But if you know of some others, tell me about them.

Police procedural. Mystery novel. Thriller. Cosy. Exotic detective. Supernatural. I used to think there was little real difference, but then my UK publisher told me he wanted to change the title of my first novel “The Collaborator of Bethlehem.” He thought it sounded like a thriller (which men typically buy) and he wanted it to be clear that it was a mystery (so that women would buy it.) He changed the title in Britain to “The Bethlehem Murders.” I had to acknowledge that he was right: it sounds more like a mystery, doesn’t it.

And that’s only in English.

As I travel around to promote my books in different countries (I’m published in 22 countries these days), I’ve noticed that there are interesting variations on the names we use in English for crime novels. Some of them are quite entertaining, and some of them tell us something revealing about how the genre developed in that country.

Take Italy. Mystery novels there are called “gialli,” or yellows. That’s because traditionally the genre was published with a yellow cover. Even today the mystery shelves of Italian bookshops are largely yellow.

Color is the theme also in Spain, where crime novels are “novelas negras,” black novels. According to a source of mine on the literary desk of El Pais, the big Spanish newspaper, this harks back to the old “Serie noire” of French publisher Gallimard. That series introduced the crime novel to Spain. So noir, or black, became the identifying color for a crime novel.

A “roman noir,” black novel, is also one of the ways of referring to a crime novel in France, because of that Gallimard series. But the most common slang for a mystery in French is “un polar.” It’s a contraction of “roman policier,” police novel, and was first recorded in 1968. If you ask most French people to explain the origin of the word “polar,” they can’t tell you: the abbreviation has become so common, they’ve forgotten its rather simple derivation.

Germany (as well as the Scandinavian countries) calls a crime novel “ein Krimi,” short for the word Kriminelle, criminal. No surprise there. It’s a catch-all for thrillers and detective stories of all kinds.

There is, however, an amusing sub-genre in German. In English, the “cosy” refers to Miss Marple-type novels in which the detective is an amateur, usually a lady (not just a woman), probably an inhabitant of a quaint village, investigating a murder in a country house or a vicarage.

The Germans call these cosies “Häkel-Krimis“. Miriam Froitzheim, who works at my German publisher C.H. Beck Verlag in Munich, translates this as “Crochet Crime Novels.” Because, as she puts it, the detective “puts her crochet gear away to solve the murder.”

I’ll keep scouting for interesting ways of describing crime novels around the world. But if you know of some others, tell me about them.

April 18, 2009

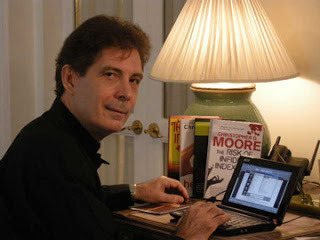

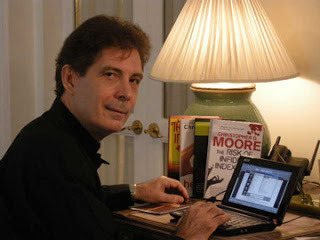

The Writing Life: Christopher G. Moore

Readers love to discover an author whose work suggests they’re a kindred spirit. Novelists, engaged in the often lonely work of writing, enjoy it even more. That’s how I feel about Christopher G. Moore, whose path is in many ways similar to mine (as you’ll see in this interview). Based in Bangkok, he’s the creator of one of the most striking sleuths in crime fiction: Vincent Calvino seems a distillation of all the most intriguing expats you’ll ever meet traveling the world and at the same time utterly unique. Moore's “Spirit House” is one of the most riveting crime novels I’ve read, and I’m delighted that he’s the first fiction writer to participate in “The Writing Life” interview series.

How long did it take you to get published?

My publishing history is a checkered one. My first professional sale was a radio drama to the CBC in 1979, and my first novel (His Lordship’s Arsenal) was published in New York in 1985. After what will soon be 21 novels (The Corruptionist will come out in 2010), I look back and think that I was lucky to start out when I did. It is much tougher now.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

There is a small library full of books on various aspects of writing. Ranging from the mechanics, to the business and legal issues, to self-help. A good web site which includes a page titled Writers Resources which has a lot of useful information about the creative process. Novelist Timothy Hallinan is the brains behind the website. It is hard to disagree with Stephen King’s "On Writing". He says that all writers must be readers. The best education is to read and re-read a diverse range of very good books. I read between 50 to 150 pages a day.

What’s a typical writing day?

The smell of fresh coffee and a long plume of black smoke rising from a burning bus across town. Seriously, there is no “typical” day as any book is a long series of marginally connected events: on the street for research, note making, organizing material, gathering profile information on characters, assembling the cast, selecting an incident that sets off a chain of events much like breaking the rack of ball in pool, fiddling with the outline, working on plot points and structure. Then there is going back to the desk to write the first draft. . .

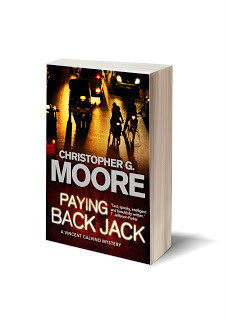

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

Grove Press will release the hardback edition of Paying Back Jack in October 2009 and Atlantic Books will release it in December 2009. This is the 10th novel in the Vincent Calvino crime fiction series.

In Paying Back Jack, Calvino agrees to follow the “minor wife” of a Thai politician and report on her movements. His client is Rick Casey, a shady American whose life has been darkened by the unsolved murder of his idealistic son. But what seems to be a simple surveillance job pulls Calvino into a quest for revenge, as well as a perilous web of political allegiance. Calvino narrowly escapes an attempt on his life and then avoids being framed for a murder only through the calculated lever-pulling of his best friend, Thai police colonel, Pratt. But unknown to our man in Bangkok, in an anonymous apartment tower in the center of the city, a two-man sniper team awaits its shot, a shot that will change everything.

I’ll let a review place Paying Back Jack in the context of contemporary Thai culture. “It's easy to see why Moore's books are popular: While seasoned with a spicy mixture of humor and realism, they stand out as model studies in East-West encounters, as satisfying for their cultural insights as they are for their hard-boiled action.”—Mark Schreiber, The Japan Times

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

I am told there are quite a few rules. But I never bothered to learn what they are. The private eye novel is mainly thought of as the creation of American authors; notably Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. It is an American invention based on crime in American cities and the social and class structure within which the private eye, police, victims and villains live and die. If there is an American location formula, I broke it in 1992 by setting Spirit House, the first of the Vincent Calvino novels set in a foreign location.

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

To bring the reader into a different culture, different rules, expectations, language, and make it meaningful without overwhelming him/her with obscure references or incidents.

The goal is to make Asia accessible without losing the vitality and history of the place.

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

I am fortunate to live in a place (Bangkok) and at a time (political chaos) that provides me with more than enough original material. A third of my fan mail is: Are you safe from the gunfire? Originality can’t be separated from the circumstances in which a writer finds himself/herself. Originality starts at home. If you lead an original life, then by the process of living the material unfolds. I suspect living in Jerusalem that you understand that authors who are living on the edge of where history is moving like tectonic plates, you understand the importance of location, and the challenges to authority, oppression, and inequality. Originality is giving a face to these concepts in real life drama played out where the stakes are high.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

“Is execution done on Cawdor?” Duncan, MacBeth, Act 1, Scene 4.

Treason, repentance, pardon and ability to die well all wrapped up nicely. So much of who we are is contained in the exchange between Duncan and Malcolm.

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

That’s a tall order to fill. Even within crime fiction there are so many compelling images. The opening of the Quiet American by Graham Greene is a wonderful description of French Colonial police and opium smoking in Saigon. But is it the best descriptive image in all literature? Doubtful. If put against the wall, the firing squad awaiting an order for me to answer or die, I’d opt for the opening of MacBeth. It is hard to beat three witches brewing up a storm when facing rifles.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

Research is the heart of any writing project. Research is part of the job. You push yourself into new situations. Meet new people. Take a different order of risk. You assess as you go along, taking notes, talking to people, strangers, friends, colleagues, locals, foreigners, to get a sense of what people are thinking, suffering, wanting, and scheming to get. Research is also the fun part of the process; you are out from behind a computer and mixing with real people. I am big fan of The Collaborator of Bethlehem: An Omar Yussef Mystery and figure you must have spent a lot of time in the back streets to get the atmosphere right. Novelists should have a journalistic instinct in the field, a poet’s instinct distilling the experience, and a surgeon’s instinct in crafting the words.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

Vincent Calvino emerged from my four years of living in New York

City. I spent time as a civilian observer with NYPD. Calvino is half Italian and half Jewish and narrative often draws upon this ethnic background. The Thai characters arose from various people that I’ve known in Thailand and elsewhere in Asia over the last 25 years.

What’s your experience with being translated?

It’s a bit like a heart transplant. You are unconscious when it happens and when you wake up (assuming that you do), you really only have a vague idea what was done. The main thing is someone else’s heart is pumping your blood. That said, I’ve become friends with my German, Japanese, and Italian translators. And from what I can see, they’ve successfully performed the transplant. I have a Hebrew edition coming out this summer. I understand the translator is an excellent surgeon.

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before could make a living at it?

I am fortunate to make a living from my writing. It was about a dozen books into the game that I was able to have sufficient revenue to pay the rent and food bills. Remember, though, where I live (at least in the early years) the cost of living was very little. That is an important factor for any writer. You need to find a place that you can exist with little money. That means places like New York, London, and Paris which once provided such opportunities for artists with meager incomes, now require a law partner’s income to pay the rent.

How many books did you write before you were published?

Three. Lost, gone but not mourned.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

A Russian Mafia thug showed up at a book reading in Pattaya and asked if he could rent one of my books. Guess he didn’t want to lay out the cash investment for a outright sale. It was a public place. I figured he wouldn’t shoot me if I said no.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

A katoey dressed in a Santa Claus outfit on Christmas Eve his small boat washed ashore at Muslim fishing village in Java.

How long did it take you to get published?

My publishing history is a checkered one. My first professional sale was a radio drama to the CBC in 1979, and my first novel (His Lordship’s Arsenal) was published in New York in 1985. After what will soon be 21 novels (The Corruptionist will come out in 2010), I look back and think that I was lucky to start out when I did. It is much tougher now.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

There is a small library full of books on various aspects of writing. Ranging from the mechanics, to the business and legal issues, to self-help. A good web site which includes a page titled Writers Resources which has a lot of useful information about the creative process. Novelist Timothy Hallinan is the brains behind the website. It is hard to disagree with Stephen King’s "On Writing". He says that all writers must be readers. The best education is to read and re-read a diverse range of very good books. I read between 50 to 150 pages a day.

What’s a typical writing day?

The smell of fresh coffee and a long plume of black smoke rising from a burning bus across town. Seriously, there is no “typical” day as any book is a long series of marginally connected events: on the street for research, note making, organizing material, gathering profile information on characters, assembling the cast, selecting an incident that sets off a chain of events much like breaking the rack of ball in pool, fiddling with the outline, working on plot points and structure. Then there is going back to the desk to write the first draft. . .

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

Grove Press will release the hardback edition of Paying Back Jack in October 2009 and Atlantic Books will release it in December 2009. This is the 10th novel in the Vincent Calvino crime fiction series.

In Paying Back Jack, Calvino agrees to follow the “minor wife” of a Thai politician and report on her movements. His client is Rick Casey, a shady American whose life has been darkened by the unsolved murder of his idealistic son. But what seems to be a simple surveillance job pulls Calvino into a quest for revenge, as well as a perilous web of political allegiance. Calvino narrowly escapes an attempt on his life and then avoids being framed for a murder only through the calculated lever-pulling of his best friend, Thai police colonel, Pratt. But unknown to our man in Bangkok, in an anonymous apartment tower in the center of the city, a two-man sniper team awaits its shot, a shot that will change everything.

I’ll let a review place Paying Back Jack in the context of contemporary Thai culture. “It's easy to see why Moore's books are popular: While seasoned with a spicy mixture of humor and realism, they stand out as model studies in East-West encounters, as satisfying for their cultural insights as they are for their hard-boiled action.”—Mark Schreiber, The Japan Times

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

I am told there are quite a few rules. But I never bothered to learn what they are. The private eye novel is mainly thought of as the creation of American authors; notably Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. It is an American invention based on crime in American cities and the social and class structure within which the private eye, police, victims and villains live and die. If there is an American location formula, I broke it in 1992 by setting Spirit House, the first of the Vincent Calvino novels set in a foreign location.

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

To bring the reader into a different culture, different rules, expectations, language, and make it meaningful without overwhelming him/her with obscure references or incidents.

The goal is to make Asia accessible without losing the vitality and history of the place.

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

I am fortunate to live in a place (Bangkok) and at a time (political chaos) that provides me with more than enough original material. A third of my fan mail is: Are you safe from the gunfire? Originality can’t be separated from the circumstances in which a writer finds himself/herself. Originality starts at home. If you lead an original life, then by the process of living the material unfolds. I suspect living in Jerusalem that you understand that authors who are living on the edge of where history is moving like tectonic plates, you understand the importance of location, and the challenges to authority, oppression, and inequality. Originality is giving a face to these concepts in real life drama played out where the stakes are high.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

“Is execution done on Cawdor?” Duncan, MacBeth, Act 1, Scene 4.

Treason, repentance, pardon and ability to die well all wrapped up nicely. So much of who we are is contained in the exchange between Duncan and Malcolm.

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

That’s a tall order to fill. Even within crime fiction there are so many compelling images. The opening of the Quiet American by Graham Greene is a wonderful description of French Colonial police and opium smoking in Saigon. But is it the best descriptive image in all literature? Doubtful. If put against the wall, the firing squad awaiting an order for me to answer or die, I’d opt for the opening of MacBeth. It is hard to beat three witches brewing up a storm when facing rifles.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

Research is the heart of any writing project. Research is part of the job. You push yourself into new situations. Meet new people. Take a different order of risk. You assess as you go along, taking notes, talking to people, strangers, friends, colleagues, locals, foreigners, to get a sense of what people are thinking, suffering, wanting, and scheming to get. Research is also the fun part of the process; you are out from behind a computer and mixing with real people. I am big fan of The Collaborator of Bethlehem: An Omar Yussef Mystery and figure you must have spent a lot of time in the back streets to get the atmosphere right. Novelists should have a journalistic instinct in the field, a poet’s instinct distilling the experience, and a surgeon’s instinct in crafting the words.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

Vincent Calvino emerged from my four years of living in New York

City. I spent time as a civilian observer with NYPD. Calvino is half Italian and half Jewish and narrative often draws upon this ethnic background. The Thai characters arose from various people that I’ve known in Thailand and elsewhere in Asia over the last 25 years.

What’s your experience with being translated?

It’s a bit like a heart transplant. You are unconscious when it happens and when you wake up (assuming that you do), you really only have a vague idea what was done. The main thing is someone else’s heart is pumping your blood. That said, I’ve become friends with my German, Japanese, and Italian translators. And from what I can see, they’ve successfully performed the transplant. I have a Hebrew edition coming out this summer. I understand the translator is an excellent surgeon.

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before could make a living at it?

I am fortunate to make a living from my writing. It was about a dozen books into the game that I was able to have sufficient revenue to pay the rent and food bills. Remember, though, where I live (at least in the early years) the cost of living was very little. That is an important factor for any writer. You need to find a place that you can exist with little money. That means places like New York, London, and Paris which once provided such opportunities for artists with meager incomes, now require a law partner’s income to pay the rent.

How many books did you write before you were published?

Three. Lost, gone but not mourned.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

A Russian Mafia thug showed up at a book reading in Pattaya and asked if he could rent one of my books. Guess he didn’t want to lay out the cash investment for a outright sale. It was a public place. I figured he wouldn’t shoot me if I said no.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

A katoey dressed in a Santa Claus outfit on Christmas Eve his small boat washed ashore at Muslim fishing village in Java.

April 17, 2009

The Best Bookshop in Germany

In the town of Ruesselsheim, near Mainz, I've discovered the best bookshop in Germany. The Buecherhaus Jansen stands in a down-at-heel pedestrian street at the heart of an industrial town (home to Opel cars, a troubled subsidiary of General Motors), surrounded mostly by doner kebab restaurants and discount stores. Hans-Juergen Jansen has built his store into a cultural center for the surrounding towns. He has a busy program of visiting authors, mostly German, and other performers for children, on whom his bookshop has a particular focus. His wife Monika also does seminars about books and performance, and his daughter puts on shows for kids (she travels the country with her Slovakian partner performing an adaptation of The Gruffalo.) I've done three readings for Herr Jansen and each time they're full, because of his efficient publicity operation and because customers know that he brings them something they can't get elsewhere in their area. On my recent visit (photo) Herr Jansen and his assistant Sonja had put up a window display about my book A Grave in Gaza which featured smashed cinder blocks a la Gaza. But inside the bookshop everything is orderly and filled with the welcoming scent of new books. Ruesselsheim isn't the most glamorous spot in Germany, but I can't wait to visit again.

Fiction more real than journalism

I wrote a guest post for A Book Blogger's Diary this week. The post, headlined "Fiction more real than journalism," explains why I turned from journalism about the Middle East to fiction, as a better way of explaining the profound things I had learned in more than a decade here in Jerusalem.

The Wanderlust and Words blog has a post about how my writing, in particular my second novel A Grave in Gaza, has channeled my traumatic experiences as a war correspondent and placed them on the page in the form of shocking moments for my characters.

Murder by the Book Mystery Bookstore blogs about my first novel The Collaborator of Bethlehem, which it calls "a thought-provoking, very different look at a community in crisis."

The Wanderlust and Words blog has a post about how my writing, in particular my second novel A Grave in Gaza, has channeled my traumatic experiences as a war correspondent and placed them on the page in the form of shocking moments for my characters.

Murder by the Book Mystery Bookstore blogs about my first novel The Collaborator of Bethlehem, which it calls "a thought-provoking, very different look at a community in crisis."

April 15, 2009

The Writing Life: Matt McAllester

I’m starting a new feature on my blog today—a series of interviews with authors about what it’s like to be a writer. I’ll be asking them the questions readers often ask me, and I’m intrigued to know how they’ll answer them. Be sure to follow this blog so you’ll see what these fascinating writers have to say in the coming months.

It’s a great pleasure to begin this series with my friend Matt McAllester. A Scot, he’s been one of the most intelligent and adventurous foreign correspondents in the world over the last decade. That earned him an uncomfortable stay in one of Saddam Hussein’s prisons, but it also brought him numerous journalism prizes (including a Pulitzer) and the material for his first two books (on Kosovo and on Iraq). Matt’s new book, out this week, is a stunning departure. “Bittersweet: Lessons from my Mother’s Kitchen” is a highly personal account of his relationship with his troubled mother—and the way his memories of her cooking helped him recover the loving, happy times before he lost her to mental illness.

How long did it take you to get published?

I’ve written three books. The proposal for the first one was rejected by every major publishing house. Finally, the wonderful New York University Press bought my proposal, which was about the war in Kosovo. I remember the moment. It was worth waiting for. Even though I’d have made more working at McDonald’s for a couple of months than I did writing that book.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

I’d mainly recommend reading brilliantly written books and then seeing if you can ever do anything that even gets close. But Orwell is the best, I think, on the process. It’s worth reading his 1946 essay, Politics and the English Language. “One needs rules when instinct fails,” he writes, and begins a short list of rules with the following, which I think is probably all any writer really needs to know: “Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.”

What’s a typical writing day?

I wish I had one. But it depends on what I’m writing – a book, an article or just trying to come up with an idea for either. A good writing day produces about 1,500 words. About three of which will be tolerable.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

It’s called Bittersweet: Lessons from my Mother’s Kitchen, and it’s a memoir of my mother, who died over three years ago. She had been mentally ill for much of her life so I was surprised by the awful power of her death. I scrabbled around for a way to make sense of it, to re-connect with her, and I ended up trying to teach myself to cook using her cookbooks. Along the way I learned a lot, I think. I hope the book is full of hope and laughs and moments of beauty and love, as well as the sadness that comes with illness and death.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

“It was amazing champagne.” The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway. And borrowed, if I remember correctly, by Geoff Dyer in his excellent Paris, Trance. I suppose I could have fallen in love with a sentence of great profundity. But instead I’m mad about these four frivolous, air-light words of joyousness and rarity.

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

There are two snatches in Brideshead Revisited that never leave me. Waugh writes of the “cloistral hush” of Oxford and then this, full of melancholy beauty, with a rhythm that any writer would dream of capturing just once: “Do you remember,” said Julia, in the tranquil, lime-scented evening, “do you remember the storm?”

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

Philip Roth, because he is almost without style these days, which I think is an act of will and humility, and suggests that he doesn’t want anything flash to get in the way of what he has to say before he dies. Which, it seems, he feels will be at any moment. Even if it’s not.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

A lot. With my Kosovo and Iraq books, I found it almost impossible to get writing until the research was nearly done. My current book was different. The book became part of the process, really, the writing and discovering and the cooking blending into each other in a way that was new to me.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

She gave birth to me. I thought she was pretty interesting from that moment on.

What’s your experience with being translated?

It’s only happened once, in French, and was jolly nice but I was a bit surprised when my book, which was written in the past tense, appeared in the present tense in French.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

I was in San Francisco having a bagel for breakfast. Room service had brought it up. My teeth crunched down on a large chunk of metal. I was pretty annoyed. I took it down to the front desk and held it out in my palm and began to complain that I’d found it in my bagel. At which point my tongue flicked across a huge gaping hole in an uppar molar. British dentistry is, I’m afraid, lampooned in the US for a reason. I rushed off to a proper dentist between radio interviews and slurred my way through the afternoon.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

A manifesto about how we should all live and work outside. I write this while sitting in Manhattan, one of the least exterior corners of the planet, and it doesn’t really seem such a weird idea.

Next up in THE WRITING LIFE: Bangkok nightlife and the dark side of Thailand with Christopher G. Moore.

It’s a great pleasure to begin this series with my friend Matt McAllester. A Scot, he’s been one of the most intelligent and adventurous foreign correspondents in the world over the last decade. That earned him an uncomfortable stay in one of Saddam Hussein’s prisons, but it also brought him numerous journalism prizes (including a Pulitzer) and the material for his first two books (on Kosovo and on Iraq). Matt’s new book, out this week, is a stunning departure. “Bittersweet: Lessons from my Mother’s Kitchen” is a highly personal account of his relationship with his troubled mother—and the way his memories of her cooking helped him recover the loving, happy times before he lost her to mental illness.

How long did it take you to get published?

I’ve written three books. The proposal for the first one was rejected by every major publishing house. Finally, the wonderful New York University Press bought my proposal, which was about the war in Kosovo. I remember the moment. It was worth waiting for. Even though I’d have made more working at McDonald’s for a couple of months than I did writing that book.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

I’d mainly recommend reading brilliantly written books and then seeing if you can ever do anything that even gets close. But Orwell is the best, I think, on the process. It’s worth reading his 1946 essay, Politics and the English Language. “One needs rules when instinct fails,” he writes, and begins a short list of rules with the following, which I think is probably all any writer really needs to know: “Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.”

What’s a typical writing day?

I wish I had one. But it depends on what I’m writing – a book, an article or just trying to come up with an idea for either. A good writing day produces about 1,500 words. About three of which will be tolerable.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

It’s called Bittersweet: Lessons from my Mother’s Kitchen, and it’s a memoir of my mother, who died over three years ago. She had been mentally ill for much of her life so I was surprised by the awful power of her death. I scrabbled around for a way to make sense of it, to re-connect with her, and I ended up trying to teach myself to cook using her cookbooks. Along the way I learned a lot, I think. I hope the book is full of hope and laughs and moments of beauty and love, as well as the sadness that comes with illness and death.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

“It was amazing champagne.” The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway. And borrowed, if I remember correctly, by Geoff Dyer in his excellent Paris, Trance. I suppose I could have fallen in love with a sentence of great profundity. But instead I’m mad about these four frivolous, air-light words of joyousness and rarity.

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

There are two snatches in Brideshead Revisited that never leave me. Waugh writes of the “cloistral hush” of Oxford and then this, full of melancholy beauty, with a rhythm that any writer would dream of capturing just once: “Do you remember,” said Julia, in the tranquil, lime-scented evening, “do you remember the storm?”

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

Philip Roth, because he is almost without style these days, which I think is an act of will and humility, and suggests that he doesn’t want anything flash to get in the way of what he has to say before he dies. Which, it seems, he feels will be at any moment. Even if it’s not.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

A lot. With my Kosovo and Iraq books, I found it almost impossible to get writing until the research was nearly done. My current book was different. The book became part of the process, really, the writing and discovering and the cooking blending into each other in a way that was new to me.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

She gave birth to me. I thought she was pretty interesting from that moment on.

What’s your experience with being translated?

It’s only happened once, in French, and was jolly nice but I was a bit surprised when my book, which was written in the past tense, appeared in the present tense in French.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

I was in San Francisco having a bagel for breakfast. Room service had brought it up. My teeth crunched down on a large chunk of metal. I was pretty annoyed. I took it down to the front desk and held it out in my palm and began to complain that I’d found it in my bagel. At which point my tongue flicked across a huge gaping hole in an uppar molar. British dentistry is, I’m afraid, lampooned in the US for a reason. I rushed off to a proper dentist between radio interviews and slurred my way through the afternoon.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

A manifesto about how we should all live and work outside. I write this while sitting in Manhattan, one of the least exterior corners of the planet, and it doesn’t really seem such a weird idea.

Next up in THE WRITING LIFE: Bangkok nightlife and the dark side of Thailand with Christopher G. Moore.

Published on April 15, 2009 21:22

•

Tags:

journalism, life, matt, mcallester, writers, writing

April 14, 2009

Crime Always Pays, Punk

One of my favourite blogs is Declan Burke's excellent Crime Always Pays, which does for Irish crime fiction what the famous toucan does for Guinness. As a Welsh crime writer, I assume I'm the next best thing to an Irish crime writer, so Declan includes me today in his long-running interview series "Ya Wanna Do It Here or Down the Station, Punk." Find out what I'd want in return for strangling puppies and biting the heads off chickens....

April 12, 2009

Tel Aviv at 100

Israel’s hippest, most tolerant city celebrates its centenary

By Matt Beynon Rees on Global Post

TEL AVIV—Purple fireworks sprayed off the roof of Tel Aviv’s City Hall last week to open festivities marking a century since Zionist pioneers began construction of the “first Hebrew city.” Watching among the crowd in Rabin Square, Marko Martin wept.

A German journalist, Martin travels the world to write cultural articles for Die Welt, filing from Myanmar to El Salvador. But he returns again and again to this Mediterranean metropolis, where his Israeli friends call him “Mister Tel Aviv.”

“No other place on earth makes me feel so much at home as this hot and shabby town, built by immigrants from all over the world,” says Martin, whose book “Tel Aviv—A Lifestyle” will be published in Germany this summer. “I was born in Communist East Germany, so I know how to appreciate an island of tolerance in an ocean of bloody fanaticism.”

At its centenary, Tel Avivians have many complaints about their city, from lack of parking to smog to the plain ugliness of most of its architecture. But they all agree with Martin that they’ve built a city that seems almost out of place in the Middle East. Where the rest of the region (including Israel’s capital, Jerusalem) is bigoted and hardline, Tel Aviv mirrors edgy European centers of social liberality like Martin’s native Berlin, even down to a flamboyant Gay Parade and a throbbing nightclub scene that brought you some of the most annoying “trance” music ever recorded.

In 1909, the area that’s now Tel Aviv was “a wilderness of sands,” according to the Zionist mythology. It had been a Canaanite settlement in the third century BC. When Napoleon besieged nearby Jaffa over two hundred years ago, he camped here. The early Zionists who decided to move the short way up the coast from Jaffa wanted to found a “Hebrew city,” unburdened by the biblical past.

They clashed with the Zionist establishment, which favored socialist collective farms and agricultural labor. Tel Aviv was home to tradesmen and shopkeepers. They called their new city “Spring Hill,” which sounds exactly like the bourgeois suburb it originally was. When the British army came through during World War I, it had a population of 2,000, compared to 50,000 in Jaffa.

But the Zionist dream was built around construction as much as agriculture. One of Israel’s national poets, Natan Alterman, immigrated from Warsaw to Tel Aviv in 1925. In his “Song to the Homeland,” he wrote: “We will clothe you in a robe of concrete and cement.”

Alterman might have specified that the robe would be a muumuu, because for a relatively young city Tel Aviv has the girth of a sumo champ.

These days Jaffa, where the Biblical Jonah took ship on his date with the whale, is the minor partner of the Tel Aviv-Jaffa municipality, an Arab slum with a smattering of gentrifying yuppies. Tel Aviv is a town of 390,000, and its greater metropolitan district has swelled to a population of 1.3 million. Not huge, but pretty good going for a city that was an outpost in a British colony until 60 years ago.

Tel Aviv has its detractors. Jerusalem has a more religious, conservative population and is inclined to see the city 40 miles away on the coast as a modern Sodom. (The ancient city which gave us the word “Sodom” is, of course, south of Jerusalem near the Dead Sea.) Certainly the gay community is very much accepted in Tel Aviv and also provides a refuge for Palestinian gays who flee their own intolerant towns. By contrast, Jerusalem grudgingly allows a Gay Parade. But over the last few years Jerusalem’s religious zealots have attacked marchers, including one gay man who was stabbed.

Tel Aviv isn’t the loveliest place to look at, either. “It is shabby, like a neglected old woman,” wrote Yossi Klein in an Israeli magazine earlier this month. (An aside: the same magazine included an interesting article on Israeli sexism.)

Personally, having grown up in a mountainous country, I’m constantly lost in the featureless landscape of Tel Aviv. I’ve been there every couple of weeks for 13 years, but it’s always as though I’m visiting for the first time, clinging to a couple of identically sycamore-lined, grubby streets which I believe will get me to the highway and back up the hill to Jerusalem in the end.

The city has been through a number of attempts to pin a name on its unique character. In the 1990s, the municipality came up with “The City that Never Stops,” which gets a cheer when visiting rock stars parrot it at concerts, but is mainly used tongue in cheek by locals. (They know it’s a third-rate reworking of “The City that Never Sleeps.”)

More recently the central district--built by Bauhaus architects fleeing Nazi persecution in the 1930s--has been somewhat spruced up and Tel Aviv dubbed itself “The White City”. In 2003, UNESCO made it a world heritage site.

It’s undoubtedly among the ugliest of the 878 world heritage sites (If you don’t believe me, check out the list). But one would be churlish to say that this cosmopolitan oasis in a desert of hate didn’t deserve some recognition.

By Matt Beynon Rees on Global Post

TEL AVIV—Purple fireworks sprayed off the roof of Tel Aviv’s City Hall last week to open festivities marking a century since Zionist pioneers began construction of the “first Hebrew city.” Watching among the crowd in Rabin Square, Marko Martin wept.

A German journalist, Martin travels the world to write cultural articles for Die Welt, filing from Myanmar to El Salvador. But he returns again and again to this Mediterranean metropolis, where his Israeli friends call him “Mister Tel Aviv.”

“No other place on earth makes me feel so much at home as this hot and shabby town, built by immigrants from all over the world,” says Martin, whose book “Tel Aviv—A Lifestyle” will be published in Germany this summer. “I was born in Communist East Germany, so I know how to appreciate an island of tolerance in an ocean of bloody fanaticism.”

At its centenary, Tel Avivians have many complaints about their city, from lack of parking to smog to the plain ugliness of most of its architecture. But they all agree with Martin that they’ve built a city that seems almost out of place in the Middle East. Where the rest of the region (including Israel’s capital, Jerusalem) is bigoted and hardline, Tel Aviv mirrors edgy European centers of social liberality like Martin’s native Berlin, even down to a flamboyant Gay Parade and a throbbing nightclub scene that brought you some of the most annoying “trance” music ever recorded.

In 1909, the area that’s now Tel Aviv was “a wilderness of sands,” according to the Zionist mythology. It had been a Canaanite settlement in the third century BC. When Napoleon besieged nearby Jaffa over two hundred years ago, he camped here. The early Zionists who decided to move the short way up the coast from Jaffa wanted to found a “Hebrew city,” unburdened by the biblical past.

They clashed with the Zionist establishment, which favored socialist collective farms and agricultural labor. Tel Aviv was home to tradesmen and shopkeepers. They called their new city “Spring Hill,” which sounds exactly like the bourgeois suburb it originally was. When the British army came through during World War I, it had a population of 2,000, compared to 50,000 in Jaffa.

But the Zionist dream was built around construction as much as agriculture. One of Israel’s national poets, Natan Alterman, immigrated from Warsaw to Tel Aviv in 1925. In his “Song to the Homeland,” he wrote: “We will clothe you in a robe of concrete and cement.”

Alterman might have specified that the robe would be a muumuu, because for a relatively young city Tel Aviv has the girth of a sumo champ.

These days Jaffa, where the Biblical Jonah took ship on his date with the whale, is the minor partner of the Tel Aviv-Jaffa municipality, an Arab slum with a smattering of gentrifying yuppies. Tel Aviv is a town of 390,000, and its greater metropolitan district has swelled to a population of 1.3 million. Not huge, but pretty good going for a city that was an outpost in a British colony until 60 years ago.

Tel Aviv has its detractors. Jerusalem has a more religious, conservative population and is inclined to see the city 40 miles away on the coast as a modern Sodom. (The ancient city which gave us the word “Sodom” is, of course, south of Jerusalem near the Dead Sea.) Certainly the gay community is very much accepted in Tel Aviv and also provides a refuge for Palestinian gays who flee their own intolerant towns. By contrast, Jerusalem grudgingly allows a Gay Parade. But over the last few years Jerusalem’s religious zealots have attacked marchers, including one gay man who was stabbed.

Tel Aviv isn’t the loveliest place to look at, either. “It is shabby, like a neglected old woman,” wrote Yossi Klein in an Israeli magazine earlier this month. (An aside: the same magazine included an interesting article on Israeli sexism.)

Personally, having grown up in a mountainous country, I’m constantly lost in the featureless landscape of Tel Aviv. I’ve been there every couple of weeks for 13 years, but it’s always as though I’m visiting for the first time, clinging to a couple of identically sycamore-lined, grubby streets which I believe will get me to the highway and back up the hill to Jerusalem in the end.

The city has been through a number of attempts to pin a name on its unique character. In the 1990s, the municipality came up with “The City that Never Stops,” which gets a cheer when visiting rock stars parrot it at concerts, but is mainly used tongue in cheek by locals. (They know it’s a third-rate reworking of “The City that Never Sleeps.”)

More recently the central district--built by Bauhaus architects fleeing Nazi persecution in the 1930s--has been somewhat spruced up and Tel Aviv dubbed itself “The White City”. In 2003, UNESCO made it a world heritage site.

It’s undoubtedly among the ugliest of the 878 world heritage sites (If you don’t believe me, check out the list). But one would be churlish to say that this cosmopolitan oasis in a desert of hate didn’t deserve some recognition.

Somali pirates, Sri Lankan slaughter, and capybara meat in a roquefort sauce

I was a guest on the BBC World Service's The World Today programme this morning. It's an eclectic news show which ranges from Somali pirates, to the Sri Lankan government's bloody new assault on the Tamil Tigers, and the taste of capybara meat (a clandestine delicacy in Venezuela apparently, although the BBC's reporter sampled it in a roquefort sauce, which strikes me as a terrible mistake.) You can listen here. The other guest is a most sympathetic fellow, Kenyan journalist Salim Lone.

Published on April 12, 2009 06:16

•

Tags:

bbc, capybara, east, interviews, lanka, middle, palestinians, somlia, sri

April 10, 2009

This is the life, Part 3: Denmark

Where better to send a bunch of crime writers and their fans than a prison? The Horsens Crime Festival in Jutland, the part of Denmark linked to mainland Europe, did just that last month.

Horsens prison was in use until three years ago. By the end it was a fairly humane place – this is Denmark, after all. But the museum set up in its old cells demonstrates how rough it was back in the mid-1800s. There are various implements for punishment, including a table with leather restraints for the waist, wrists and ankles. Walking through the upper galleries on my own, I looked out of the window and watched a car drive by beyond the walls. I felt a sudden pang of such desolating loneliness that I hurried down to the yard, where the crime festival was being held just to be among people.

(Not before I checked out the display of confiscated pornography from different eras and a rather horrifying pair of brown leather mittens to be locked onto the hands of inveterate Onanists.)

Almost all the authors were Scandinavian, which means that many of them were familiar names, as that sub-genre appears to go from strength to strength. (Swede Camilla Läckberg, however, wasn’t there, which was a shame because I’ve been wanting to meet her ever since I saw the picture of her taking a bubble bath on her website – you think I’m kidding? I bet it gets a lot of traffic.) Organized by the Horsens Library, the only other non-Nordic writer was Don Winslow. One to watch, from what I saw was a smooth and rather dapper Swedish writer named Mons Kallentoft.

My Danish publisher Gyldendal brought me to the festival, where I was interviewed by Niels Lillelund, culture correspondent with Jyllands-Posten. That’s certainly the most famous Danish newspaper where I live. You may remember it’s the paper which published the famous cartoons of Muhammad, which sent millions of Muslims into a rage. Niels, I hasten to add, didn’t draw the cartoons, but he did do a fine job of interviewing me at the book festival about my second Palestinian crime novel A Grave in Gaza, which is just out now in Danish.

Horsens is a quiet provincial town with a charming central section where the croci were just in bloom in the lush grass of the city park. We were there long enough for my editor Helle Stavnem to translate the names of some Danish pastries (one which has a large blob of yellow curd at the center is called “the baker’s bad eye.” Yum.)

The visit to Horsens was over quickly, however, and we were off to Copenhagen, where I stayed right beside the University library, around the corner from Tycho Brahe’s observatory. (There are various theories about Brahe’s possible murder by rival astronomer Johannes Kepler, which I was discussing only today with Tel Aviv University optical historian Raz Chen….)

The palace complex in Copenhagen is quite beautiful, particularly in the early morning fog that comes in off the sea smelling of lentil soup. The Royal Library was my favorite building, or more precisely the wide courtyard leading to it, grassy and empty but for a woman smoking a cigarette on a bench and a gardener pruning bushes. The lights from the red brick building were inviting in the overcast day and made me hanker for my university days.

Outside the palace, on the wall of the canal, a warning to boats: “Proceed with caution. Sculpture under water. Merman with seven sons.” Below the freezing water, eight figures, a man and seven boys. Eerily their heads were oxidized turquoise so that they stood out from their bodies. They seemed to be grasping for the surface.

Another highlight: the Frue Kirke, the cathedral of “Kooben-hawn” (as they call it). Very Spartan design and quite striking.

I dropped by my local agent, Eva Haagerup, at Leonhardt & Hoier. The office is in a neighborhood of central Copenhagen called Pisserenden, because – there’s no nice way to put this – it used to be a low-rent area where people would piss in the streets. Now it’s rather nice with a lot of bars and restaurants, but Eva says that at night there’s still some outdoor watersports.

On the way to the airport, I stopped at the national tv channel for an interview with an energetic, intelligent journalist named Adam Holm. Why can’t US tv people be like this? They’re all so blow-dried and empty. Adam and I arranged to meet in Jerusalem some time.

I picked up a couple of books: one by a Dane whose previous books I’ve enjoyed, Peter Hoeg (“The Quiet Girl”), and another a historical novel about Copenhagen by a Swede (“The Royal Physician's Visit”). I’ll blog about them soon.

Horsens prison was in use until three years ago. By the end it was a fairly humane place – this is Denmark, after all. But the museum set up in its old cells demonstrates how rough it was back in the mid-1800s. There are various implements for punishment, including a table with leather restraints for the waist, wrists and ankles. Walking through the upper galleries on my own, I looked out of the window and watched a car drive by beyond the walls. I felt a sudden pang of such desolating loneliness that I hurried down to the yard, where the crime festival was being held just to be among people.

(Not before I checked out the display of confiscated pornography from different eras and a rather horrifying pair of brown leather mittens to be locked onto the hands of inveterate Onanists.)

Almost all the authors were Scandinavian, which means that many of them were familiar names, as that sub-genre appears to go from strength to strength. (Swede Camilla Läckberg, however, wasn’t there, which was a shame because I’ve been wanting to meet her ever since I saw the picture of her taking a bubble bath on her website – you think I’m kidding? I bet it gets a lot of traffic.) Organized by the Horsens Library, the only other non-Nordic writer was Don Winslow. One to watch, from what I saw was a smooth and rather dapper Swedish writer named Mons Kallentoft.

My Danish publisher Gyldendal brought me to the festival, where I was interviewed by Niels Lillelund, culture correspondent with Jyllands-Posten. That’s certainly the most famous Danish newspaper where I live. You may remember it’s the paper which published the famous cartoons of Muhammad, which sent millions of Muslims into a rage. Niels, I hasten to add, didn’t draw the cartoons, but he did do a fine job of interviewing me at the book festival about my second Palestinian crime novel A Grave in Gaza, which is just out now in Danish.

Horsens is a quiet provincial town with a charming central section where the croci were just in bloom in the lush grass of the city park. We were there long enough for my editor Helle Stavnem to translate the names of some Danish pastries (one which has a large blob of yellow curd at the center is called “the baker’s bad eye.” Yum.)

The visit to Horsens was over quickly, however, and we were off to Copenhagen, where I stayed right beside the University library, around the corner from Tycho Brahe’s observatory. (There are various theories about Brahe’s possible murder by rival astronomer Johannes Kepler, which I was discussing only today with Tel Aviv University optical historian Raz Chen….)

The palace complex in Copenhagen is quite beautiful, particularly in the early morning fog that comes in off the sea smelling of lentil soup. The Royal Library was my favorite building, or more precisely the wide courtyard leading to it, grassy and empty but for a woman smoking a cigarette on a bench and a gardener pruning bushes. The lights from the red brick building were inviting in the overcast day and made me hanker for my university days.

Outside the palace, on the wall of the canal, a warning to boats: “Proceed with caution. Sculpture under water. Merman with seven sons.” Below the freezing water, eight figures, a man and seven boys. Eerily their heads were oxidized turquoise so that they stood out from their bodies. They seemed to be grasping for the surface.

Another highlight: the Frue Kirke, the cathedral of “Kooben-hawn” (as they call it). Very Spartan design and quite striking.

I dropped by my local agent, Eva Haagerup, at Leonhardt & Hoier. The office is in a neighborhood of central Copenhagen called Pisserenden, because – there’s no nice way to put this – it used to be a low-rent area where people would piss in the streets. Now it’s rather nice with a lot of bars and restaurants, but Eva says that at night there’s still some outdoor watersports.

On the way to the airport, I stopped at the national tv channel for an interview with an energetic, intelligent journalist named Adam Holm. Why can’t US tv people be like this? They’re all so blow-dried and empty. Adam and I arranged to meet in Jerusalem some time.

I picked up a couple of books: one by a Dane whose previous books I’ve enjoyed, Peter Hoeg (“The Quiet Girl”), and another a historical novel about Copenhagen by a Swede (“The Royal Physician's Visit”). I’ll blog about them soon.

April 9, 2009

Review: the mystery of the new Mankell

Italian Shoes by Henning Mankell

US: New Press. April 1, 2009. Isbn: 1595584366

In his 26th novel, Sweden’s top crime writer has eschewed the genre that has seen him sell 30 million books. Even so, fans of his Inspector Wallander novels will find much of what they love about the Skåne detective in the narrator of “Italian Shoes”—only given even more depth by the constant focus on a man struggling with guilt and emotional silence.

Fredrik is a surgeon who abandoned his career a decade ago because of a mistake he made during an operation. He refused to acknowledge his error and went to live alone on a remote island. One morning he sees a woman standing on the frozen sea. He discovers that she’s the girlfriend he abandoned as a young man.

Harriet’s arrival forces Fredrik to meet a series of people from his past. He thought he could cut himself off on his island. As he realizes he can’t, he finds the allure of companionship attractive, but struggles to manage these new relationships.

This is a devastatingly honest and keenly personal novel. It ranks with Norwegian Per Petterson’s “Out Stealing Horses” for its marvelous portrayal of withdrawal from society—and its consequences. Mankell writes with a measured pace that’s in tune with the frozen weather and the slow body of the aging Fredrik.

Though “Italian Shoes” is a departure for Mankell, he examines a topic common to crime novels—death. But he reverses the crime novel’s way of looking at death. He’s not concerned here with how death occurs. Rather he wants to understand why anyone should care whether they live or die.

Crime writers create a violent death, to show how the remaining characters experience life in extreme circumstances. Here Mankell depicts a man who essentially stopped living and who rediscovers life when faced with the impending death of Harriet.

“Before I die,” Fredrik says, “I must know why I’ve lived.” In his dour, bitter way, Mankell has the answer.