Matt Rees's Blog, page 25

May 9, 2010

Hamas rebuilds in West Bank

Hamas is steadily rebuilding its power in the West Bank, stockpiling weapons and material underground, biding its time for a renewal of the conflict with its Fatah rivals.

Hamas is steadily rebuilding its power in the West Bank, stockpiling weapons and material underground, biding its time for a renewal of the conflict with its Fatah rivals.Palestinian security officials have been telling me this for some time, and they are frankly filled with fear and foreboding. Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas mentioned it again in an interview with the Arabic newspaper al-Sharq al-Awsat during the week, accusing Hamas of smuggling weapons to the West Bank.

The Hamas buildup is one of the reasons Abbas has allowed his independent prime minister, Salaam Fayyad, to stay in his job so long, despite the popularity Fayyad is accruing at the expense of Abbas’s Fatah. Fayyad has managed to reform the Palestinian security forces, persuading the U.S. to give tens of millions of dollars in security aid.

Without those reforms, the Palestinian security forces would either fold in minutes if faced with a Hamas uprising in the West Bank, or would even join Hamas to save themselves.

So it’s significant that after 10 days in which Abbas repeatedly berated Fayyad’s plan to declare a Palestinian state in 2011 — which would convince the world that if Fayyad could create a state, Fatah might’ve become irrelevant and therefore not worth the cash it siphons away — the president also highlighted the urgency of Fayyad’s most important achievement. (He first talked about it in an interview with a Kuwaiti newspaper in January, when he said he had “verified information” that Hamas planned to take over the West Bank by force.)

Of course, U.S. and European security advisers to the Palestinian security forces don’t claim to have made much of their new charges. If Hamas is able to recreate its West Bank network, the Palestinian security forces will hold up their advance for only about a week, they estimate.

That’s not bad, given that two years ago the Palestinian security forces were good for nothing much at all. A week might also buy time for a cease-fire, which might in turn preclude an Israeli invasion of the West Bank — it’s unimaginable that the Israelis would allow the West Bank to come under Hamas control.

Part of Abbas’ accusation against Hamas is that its leadership is allowing radical young military leaders to blow off steam by plotting a West Bank armed takeover. In return, those military leaders aren’t pushing as hard for rocket attacks against Israel from Gaza.

The Hamas leaders in Gaza are keen to avoid such attacks, because they’re barely recovering from the hammering they received a year and a half ago at the hands of the Israeli army. The cause of that war, remember, was rocket attacks from Gaza into Israel.

Hamas kicked Fatah out of the Gaza Strip in 2007. Fatah people were shot and tortured, and a few were tossed from tall buildings. Since then, both sides have engaged in a low-flame civil war which involves lengthy detentions without trial, torture and kneecappings.

The West Bank looks like an attractive playground into which Hamas can shove its angrier military types. After all, if the Fatah cops fail to intercept a Hamas attack against Israelis in or from the West Bank, Israel usually blames Fatah rather than Hamas.

Within the Izzedine al-Qassam Brigades, the Hamas military wing, support has been increasing for more militant action — yes, more militant than the leadership which ultimately wants to eradicate Israel but is prepared to wait a long time to do so. (In Gaza, that counts as dovishness...)

Those military leaders have turned, according to international analysts, to a brand of Islam more commonly called “Salafi.” In short, it’s the extreme Islam favored by many in the Gulf States. It’s quite alien to most Palestinians, who are conservative but not particularly fundamentalist in their religion. Still, once a military type gets stirred up, the hard line often looks appealing.

Abbas better hope he hasn’t leaned too hard on Fayyad. The week of grace his prime minister’s reforms will have bought him in the event of an attempted coup by Hamas might prove to be the difference between a nice retirement at his house in Dubai and the kind of kangaroo justice meted out by the Islamist in Gaza three years ago.

(I posted this on Global Post.)

Published on May 09, 2010 23:09

•

Tags:

abu-mazen, crime-fiction, dubai, fatah, gaza, global-post, hamas, intifada, israel, israeli, izzedine-al-qassam-brigades, mahmoud-abbas, middle-east, palestine, palestinians, plo, salaam-fayyad, salafi, sharq-al-awsat, west-bank

May 6, 2010

What do YOU think of me?

A friend of mine was lunching with a Scandinavian author a while back. At one point, the writer joked: “But that’s enough of me talking about myself. What do YOU think of me?”

A friend of mine was lunching with a Scandinavian author a while back. At one point, the writer joked: “But that’s enough of me talking about myself. What do YOU think of me?”Unlike that writer, I don’t care what you think of me. Don’t be offended – I don’t care what I think about other people, either. The more I write, the more I realize that I’m interested in myself alone.

That, I believe, is the necessary focus of all art – even if its final aim is to turn that inward look out toward the reader, the viewer, the listener. Art is flawed unless it focuses on the artist’s relationship with the world around him – through the narrator’s voice, in the case of a novelist.

I’ve been poring over this for a while, but it came to the fore last week after I spoke to an American group visiting Jerusalem. Mimi Schwartz, a writer of creative nonfiction, approached me after the event. She was kind enough to say that my long tenure here in Jerusalem – next month it’ll be 14 years – gave me a valuable perspective on the place. She suggested I write a memoir, in between my crime novels, because it would allow me “to bear witness.”

When I think of writing nonfiction about my experiences here, I tend to view the likely outcome as being David Sedaris-style essays telling amusing tales or a one-man-show in a similar vein. I don’t think that’s quite what Mimi had in mind. (She seemed like a lady of broad curiosity. I don’t think she’d be upset.)

I don’t want to “bear witness.” What I’ve witnessed in Jerusalem, Nablus, Tel Aviv, Gaza – none of it seems to have any value, frankly, unless I can tell you how I feel about it. Otherwise it’s just a litany of body parts and angry people and failed politics and disappointing lives.

I don’t mean to suggest that art has to be uplifting. But it has to open reality out, spread it wider than the small scope of journalism. That’s why much photography often seems to me to be the sneaky little charlatan of the arts world, because it’s so frequently done for the eye-catching cool beloved of ad-men or with an empty-eyed blandness.

By the same token, art may descend too far beyond the personal. The solipsistic crap that passes for contemporary art is the flipside of the banality of the mediocre photographer.

So all (bearable) art is, in a sense, bearing witness. Because it must be based firmly in something real. If it isn’t based in something real, then it doesn’t come as a reaction on the part of the artist to a real experience – and there’ll be something about it that tips the reader or viewer to the fact that the artist is lieing about or obscuring himself.

My series of four crime novels about Omar Yussef, a Palestinian detective, obviously have an element based in reality, because Omar is a way for me to unfold the scenes and emotions through which I’ve lived these past 14 years. But my next novel, which is to be about the death of Mozart, will just as surely be based in my experience of how people react to a loss and the dirty reality that’s likely to lie behind a sudden death.

To do my bit of bearing witness, I plan to stick to fiction. It’s closer to the real truth.

Published on May 06, 2010 01:23

•

Tags:

art, contemporary-art, creative-nonfiction, crime-fiction, david-sedaris, fiction, gaza, israel, jerusalem, journalism, middle-east, mimi-schwartz, mozart, nablus, nonfiction, omar-yussef, palestine, palestinian-detective, photography, tel-aviv

May 5, 2010

Good times, danger signs in West Bank

BETHLEHEM, West Bank — The good news is that the West Bank is normal — kind of — and that people are content — sort of. The bad news, the Palestine Liberation Organization thinks it’s responsible for the good news.

BETHLEHEM, West Bank — The good news is that the West Bank is normal — kind of — and that people are content — sort of. The bad news, the Palestine Liberation Organization thinks it’s responsible for the good news.Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, who’s also the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) chief, has decided to stamp down on the man who’s actually made life bearable in the West Bank, Prime Minister Salaam Fayyad, and his plan to declare a unilateral Palestinian state in 2011.

At a meeting of the Fatah Revolutionary Council, effectively the PLO’s ruling body, Abbas said last week that only the PLO was allowed to make decisions on behalf of the Palestinian people.

"It’s not the factions or the governments that take ownership of decisions," Abbas said.

Abbas wants to continue on the path that has led the Palestinians and the Israelis nowhere. So-called “proximity talks,” in which they talk via U.S. mediators, are supposed to start again soon. They’re unlikely to change anything.

Fayyad, who’s a political independent appointed to his post by Abbas mainly because the Americans insisted on it, announced his plan last year for the declaration of a state. The idea: truly to ready Palestinian institutions for independence and to dare Israel — and the U.S. — to oppose it.

Fayyad’s ability to clean up the economy and reform the security forces has made him popular among Palestinians. He’s also seen as untainted by the violence and corruption of the two main political parties, Abbas’s Fatah and the Hamas rulers of Gaza.

That makes him a potential rival to Fatah. PLO chiefs fear that if Fayyad declares a Palestinian state and the U.S. cheers, maybe its bankrollers in Washington and Oslo and Brussels will cut the PLO out of the power and money loop. That, after all, is what the PLO is all about. “organization” is the operative word in the name of the PLO, rather than “liberation."

A visit to Bethlehem this week delineates the precise choice on offer between Abbas and Fayyad.

In the Dehaisha Refugee Camp, less than a square mile that’s home to more than 16,000 poor Palestinians, there are bulletholes in the walls of the U.N. girls' school, left over from the second intifada. A reminder of the final bankruptcy of the PLO and its failure to convert itself from an outlaw band into a true government after the signing of the Oslo Peace Accords in 1993.

The casualties of that long descent into destruction are painted all over the walls. On the pedestrian bridge the girls cross to reach their school, there’s a 10-foot graffito of Sa'id Eid, masked and firing a mortar. He was killed by an Israeli Apache helicopter in 2003. As the girls come down on the other side, they pass another big stencil in black paint. This time it’s Ayat Akhras, at 16 the youngest female suicide bomber, who left her home in Dehaisha in 2002 to kill herself, a 17-year-old Israeli girl and an aging supermarket guard. She raises a pistol like a naif Bond girl.

At the corner, a falafel restaurant is decorated with murals of all the martyrs of the Palestinians, from Ghassan Kanafani, writer and Popular Front activist killed by the Israelis in Lebanon in 1972, to a collection of the intifada’s most famous victims, and above them Khalil Wazir, the Arafat lieutenant assassinated by Israel in 1988.

A continuation of that fatal litany is, frankly, what’s offered by the “proximity” talks. Because they’ll lead only to frustration, a sense that nothing can be achieved by negotiation, and a resultant impetus toward violence.

What’s the alternative?

Mike Canawati, one of Bethlehem’s leading businessmen, describes trade in his tourist shop on the road to the Church of the Nativity, the site of Jesus’s birth, as “excellent, really excellent.” That’s the result of Fayyad’s ability to convince the Israeli army that checkpoints can be lifted and his commitment to a higher level of training among Palestinian security forces, so that tourists don’t fear to enter Bethlehem as they did for much of the last decade.

It isn’t a total shift. The dangers are simply less immediately apparent. Canawati still sits at his desk flanked by a screen with 16 different closed-circuit images of the store, the alley behind it, his black Hummer parked at the side of the building.

Only the night before we met, he had welcomed 700 Italian diners in his banquet hall near the church. “We should be thankful to these people for coming to our town,” Canawati said. During the dinner, a group of Fatah people entered and unfurled banners protesting that the Italians would later hold a meeting with Israelis in Jerusalem. “I had a big argument with them,” he said, “and I threw them out.”

Back in Dehaisha, I took my son to a birthday party at a friend’s home. My friend spent nine years in an Israeli jail without charge. He was, in fact, in jail seven years ago when the birthday boy was born. Now he’s studying for a Master’s degree in law.

A clown inflated sausage-balloons and tied them into the shape of swords. I was strangely relieved that they weren’t bent into Kalashnikovs.

When the birthday cake came out, the clown’s assistant emerged dressed as SpongeBob SquarePants. She sang “Happy Birthday” in Arabic with the aid of ear-splitting amplification and did some unexpected SpongeBob belly dancing moves.

Whatever Abbas and his PLO cronies say, that’s the kind of reality we should be wishing on the people of Dehaisha.

Published on May 05, 2010 05:34

•

Tags:

abu-jihad, abu-mazen, ayat-al-akhras, bethlehem, church-of-the-nativity, dehaisha-refugee-camp, fatah-revolutionary-council, gaza, ghassan-kanafani, hamas, hummer, israel, khalil-wazir, mahmoud-abbas, middle-east, palestine, palestinians, peace-talks, plo, refugees, salaam-fayyad, spongebob-squarepants, west-bank

April 29, 2010

Stealing the novel, really

Every couple of days a little alert pops up in my email account letting me know that I can read my books for nothing in Norwegian. My Norwegian’s not so great and I can read my books for nothing any time. But that’s not the point.

Every couple of days a little alert pops up in my email account letting me know that I can read my books for nothing in Norwegian. My Norwegian’s not so great and I can read my books for nothing any time. But that’s not the point.Scandinavia is a major center of so-called Cyberpunks who have willfully misinterpreted an old hacker adage that “information wants to be free” to mean “go ahead and steal things from which someone else expects to earn his livelihood.” Such Cyber types have, among other things, loaded electronic versions of my novels in Norwegian onto the internet so that anyone can take them without paying.

It’s a little odd. Anyone who’s been to Scandinavia will see that the locals are perfectly willing to pay through the nose for things which ought to be cheap. Even if they actually bought my novel, it’d still be cheaper than the train ride from Oslo Airport to downtown Oslo or a sandwich and soda by the fjord. And everyone’s so nice. Maybe that’s the problem–they’re trying to be nice to information. As long as they believe that the information wants to be free, then they’re only helping the information out by taking it for nothing…

It’s all the thin end of a disturbing wedge for creative artists such as yours truly who support their families entirely from their endeavors as authors, artists, musicians – and who for the most part would be somewhat better remunerated were they to choose to drive a bus for a living.

Information wants to be free but, as the original coiner of that phrase noted, information also wants to be expensive. If information is the catalogue of the Library of Congress, make it free. Sure, let’s have free access to recipes from Renaissance Florence and the geology of the Grand Canyon.

But not art. Art doesn’t want to be free. Art wants to be labored over by a person whose mind isn’t distracted by other things. Art wants to be made as good as it can be. Art wants creative dedication, it doesn’t want to be zapped out by people in a hurry who have to do a day-job, too.

Art, needless to say, is not just information.

Of course we can all justify a little theft. When I was a teen, I used to steal books. But only from big chain bookstores and only from authors who were long dead. The one time I broke those self-imposed rules, I nearly got tossed out of university for lifting a copy of a book written by my tutor’s wife from the college library before the librarian had even got around to cataloguing it. Anyhow, I gave that one back, because my education was free, so I was content for that particular bit of information not to be.

Others use Ebay to salve their conscience. For example, some penny-pinching Scot is offering for sale on Ebay Advance Uncorrected Proofs of my novels. These are sent out free to reviewers and booksellers before the books appear on the shelves. They’re clearly marked “Not for Resale” in big letters on the cover.

It could be that this person in Scotland would’ve behaved differently had the words “Nae fer resale” appeared in dialect on the cover. But I suspect that this person thinks that selling something dishonestly on the internet isn’t really dishonest. If that person were to walk into a second-hand bookstore and face a bookseller with his clearly marked “Not for Resale,” he’d feel a little ashamed at asking money for it. In selling just as in the writing of offensive anonymous comments, the internet is a shield for our worst behavior.

Well, as they say in Scotland, dinna fash yersel. I’ll manage, even if there are a few such novel proofs flying about. But think of poor Stephenie Meyer. Her blog mentioned not so long ago that someone had posted an early draft of her next novel on the internet and that hundreds of thousands of people had downloaded it.

(An aside: why on earth would anyone read an early draft of a novel unless they had to do so? Novels aren’t flash fiction. They take a long time and lots of work to make them right and until they’re right the reading of them can be pretty dire.)

Hey, you say, she’s not short of cash. Well, what’re you, a communist? Robin Hood?

Okay, Meyer’s no doubt quite rich as a result of her strange subgenre. But she’s not Goldman Sachs. She isn’t marketing worthless things to people, intending for them to lose millions of dollars and enrich her in return. She’s being paid for the enriching experience of reading for those who buy her books.

When I mentioned to some friends that this sort of thing went on with books, they were surprised. Each of them noted that they had taken music and movies from the internet in just the same way. Each also said that they figured Roman Polanski was rich enough to let them have a free look at “The Ghost Writer.” That Bono would still be able to afford fancy sunglasses if they ripped off his latest album.

But remember, Cyberpunks are anarchists. Do you really want them to define the way you live? When was the last time you read a good book by an anarchist?

As the recently deceased Malcolm McLaren always noted, even The Sex Pistols with their claim to be anarchists were only in it for the money.

Published on April 29, 2010 00:34

•

Tags:

art, bono, crime-fiction, cyberpunks, ebay, goldman-sachs, grand-canyon, internet, library-of-congress, malcolm-mclaren, norway, oslo, roman-polanski, scandinavia, scotland, stephenie-meyer, the-ghost-writer, the-sex-pistols, u2

April 25, 2010

Scribe and Scholar enter world of Hamas

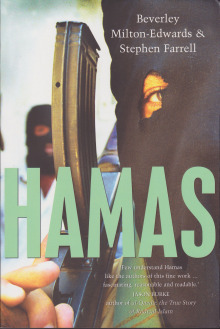

A New York Times correspondent teams up with a Belfast professor to write the story of Islamism among the Palestinians.

A New York Times correspondent teams up with a Belfast professor to write the story of Islamism among the Palestinians.JERUSALEM — Stephen Farrell was sipping coffee in the office of his money changer on Salah ud-Din Street, East Jerusalem’s main commercial strip, four years ago, when Beverley Milton-Edwards entered. From his rucksack, Farrell produced a copy of a book about Islamic militants written by the Queens University Belfast professor.

“Your book saved my life when I was kidnapped in Iraq,” he said, referring to a brief period of captivity by militants in Baghdad in 2004 when working for The Times of London. The dogeared volume had given London-born Farrell, now a New York Times foreign correspondent, the background he needed to convince his kidnappers that he had studied and understood their political and religious concerns. (Money may also have changed hands, of course...)

“That’s quite an endorsement,” Milton-Edwards responded. “Would you write that for the cover of my next book.”

Instead, he wrote an entire book with her. “Hamas: The Islamic Resistance Movement” (Polity Press) is the product of a decade in the Middle East for Farrell — who was kidnapped again, by the Taliban in Afghanistan, last September and freed by British commandos.

Surprisingly, given the amount of ink spilled over Hamas, it’s the first book broadly profiling the Islamic group that’s not written by an Arab or Israeli author. (GlobalPost correspondent Thanassis Cambanis may do the same for another militant group oddly neglected by Western book authors with his "A Privilege to Die: Inside Hezbollah's Legions and Their Endless War Against Israel," to be published September by Free Press.)

It’s certainly an opportune time for a history and analysis of Hamas. The group, which originated in Gaza during the first Palestinian intifada, transformed in recent years, initially killing more Israelis during the second intifada than previously would’ve been imaginable, then reversing its refusal to run in elections. Hamas won the parliamentary elections of 2006 and, in 2007, ran its rival Fatah out of the Gaza Strip, setting up the present quagmire of Palestinian politics.

I’ve known Farrell since he arrived in the Middle East for the London Times, having previously done a spell in Kosovo. He soon acquired a reputation for extreme thoroughness. On one visit to the southern Gaza Strip town of Rafah during the intifada, I ran into Farrell. He wasn’t there to cover a particular story. He said he hadn’t been busy, so he’d gone out to see what he might find. Given the volume of stories required of Jerusalem-based correspondents and the risks involved in getting to Rafah, extra-credit work such as this was rather unheard of.

“It’s very difficult to know something second-hand,” said Farrell, over coffee in a theater cafe in Jerusalem. “When you’re at the scene, things are so much more complex. That’s why you need to examine it in a book.”

Milton-Edwards provided much of the historical background that informs the book’s fascinating sections on the history of Islamism among the Palestinians before the foundation of Israel, and the activism in the 1970s of the men who would later form Hamas. But she, too, participated in much of the research on the ground, having a long-term knowledge of the place. She completed a Ph.D. on Hamas and Islamic Jihad after a media internship in Jerusalem during the first intifada.

That extensive research provides some of the most interesting snippets in the book. Hamas founder Ahmed Yassin was, in fact, an educator, not a religious leader, though he has been almost universally known as “Sheikh Yassin,” an honorific implying great Islamic learning.

The book’s historical perspective also provides surprising statistics. During the five years before the 2006 elections, Hamas had killed 400 Israelis. That’s an enormous toll, but amounts to just a couple of days work for Islamic radicals in Iraq about whom we know much less.

Written in a tone that tends closer to a plain academic style than the more trendy novelistic type of nonfiction book, “Hamas” doesn’t restrict itself to the politics and the violence. There’s a lengthy segment on the group’s approach to women — largely negative, particularly when seen through the eyes of the cosmopolitan leaders of the previous generation, like the chain-smoking Mariam Abu Dugga who wears no headscarf and used to be a member of the “Martyr Guevara” group.

Within Palestinian society, Farrell and Milton-Edwards examine Hamas’ treatment of those it considers collaborators with Israel or merely uncommitted to the Islamic lifestyle. Needless to say, it doesn’t look good.

“We don’t whitewash Hamas,” said Milton-Edwards. “We don’t ignore their cruelties.”

The more recent internal divisions within Hamas are laid out plainly and in a detail not found elsewhere. The book looks at the still burgeoning conflict between the group’s original leadership — no blushing softies, after all — and a new generation of military leaders in Gaza in particular which wants Hamas to adopt a “salafi” line akin to the even more uncompromising Islamists produced by the Gulf states. The less-than-encouraging news is that in the last year the “salafist” wing of Hamas has taken the upper hand over the relative moderates.

Behind all this Farrell and Milton-Edwards identify a failure of leadership on the part of Hamas and its Fatah rivals that’s summed up by Hanan Ashrawi, a former Palestinian peace negotiator quoted in the book: “Hamas had to learn very quickly how to be in power and Fatah has to learn how to be out of power. Both of them haven’t learned, really. Fatah is not used to being in opposition, it doesn’t know how to, and Hamas is not used to being in government, and it behaved like an opposition.”

(I posted this on Global Post. Read more of my dispatches.)

Published on April 25, 2010 02:00

•

Tags:

afghanistan, baghdad, belfast, beverley-milton-edwards, books, fatah, gaza, hamas, hanan-ashrawi, hezbollah, intifada, iraq, islam, jerusalem, middle-east, new-york-times, palestine, palestinians, polity-press, queens-university-belfast, reviews, sheikh-yassin, stephen-farrell, taliban, terrorism, thanassis-cambanis

April 23, 2010

My voice and his voice: first- or third-person narrative in the novel

Robert Harris has been one of my favorite authors since I first laid hands on “Fatherland,” his “what if the Nazis had won” thriller. “Enigma” and “Archangel” were even better. His first two Roman ventures “Pompei” and “Imperium” were by no means the worst books I read in the years of their publication.

Robert Harris has been one of my favorite authors since I first laid hands on “Fatherland,” his “what if the Nazis had won” thriller. “Enigma” and “Archangel” were even better. His first two Roman ventures “Pompei” and “Imperium” were by no means the worst books I read in the years of their publication.Then came “The Ghost.” The story of a hack writer hired to ghost the memoirs of a former British Prime Minister — transparently Tony Blair — was diminished by two things. First, Harris clearly dislikes Blair’s political decisions so much he lost some of the power of empathy that had been important in his earlier books. Second, it was one of those times when the first person narrator simply didn’t work.

Now that the novel has been made into a movie – with Harris co-writing the script with Roman Polanski – the “I” has been dropped. Significantly, the story now works much better. What is it about the change of voice that completely shifted the emphasis of the book, and improved the storytelling?

Voice – “my” voice or “his” voice – is a key element in writing a novel. “I” can give you something quirky or, more significantly, immediacy. “His” gives you detachment.

Harris wanted his narrator to be increasingly compelled, against his better instincts, to investigate something seedy he appeared to be uncovering about the former Prime Minister as he worked on the memoirs with him. In fact, it robbed him of detachment and left the narrative cluttered with the kind of outrage about Iraq and terrorist rendition the Ghostwriter probably wouldn’t have felt – but which Harris clearly did.

By taking the story out of the first person, Polanski and Harris avoided the internal outrage. Instead, they made the unnamed Ghostwriter’s actions almost entirely the result of external events. Only once or twice does he make a choice that takes him deeper into the action – to call a political foe of the Prime Minister whose phone number he finds in a dead man’s effects, for example. That’s far less than in the novel, where he’s constantly talking himself into doing something we all know he shouldn’t…and which a man being paid a quarter of a million pounds for a month’s ghostwriting surely would avoid.

There’s an alternative to the immediacy of “I” and the all-knowing narrator of the Victorian novel, however. Think of point of view. Each chapter – even the entire novel – should be from the point of view of particular character. That way you get the immediacy of first person without sacrificing the detachment of third person. (Third person also gives you more descriptive power as you can use language that might seem verbose in the mouth of your character.)

In other words, stay “with” a single character. See only what he sees. From time to time, let us into his head with a “he thought.” But don’t stay inside that head and, by the same token, don’t switch heads from paragraph to paragraph. Let things happen to the character without the reader seeing it entirely through the character’s eyes.

That’s what Polanski has Harris do in the movie “The Ghost Writer.” Ewan McGregor, who plays the Ghostwriter, is in almost every scene. We see everything unfold from his point of view. We just don’t have to follow every trivial thought or angry impulse. And we end up with a lot more sympathy for the former Prime Minister.

It might seem less hard-hitting as political commentary. But it’s a much better story.

Published on April 23, 2010 03:10

•

Tags:

archangel, crime-fiction, enigma, ewan-mcgregor, fatherland, imperium, pompei, robert-harris, roman-polanski, the-ghost, the-ghost-writer, thrillers, tony-blair, writing

April 16, 2010

Bibi’s Bedtime Book: The Secret Diary of Prime Minister Netanyahu #2

I can’t believe the extent of the corruption being uncovered in Israel’s government.

I can’t believe the extent of the corruption being uncovered in Israel’s government.My predecessor as Prime Minister drifted home from vacation yesterday – without any envelopes stuffed with cash, as far as we know -- and made a mopey statement about yet another investigation into bribery and fraud and breach of trust on his part. He’s alleged to have been in cahoots with a bunch of shady property developers, lawyers and municipal officials, so that a big, tacky building could be put up in southern Jerusalem to provide luxury dwellings for property developers and lawyers. Oh, and the former State Prosecutor, too – apparently she has an apartment there. I don’t draw any conclusions from that, though. I'm not an investigator. I just run the country.

It looks like poor old Champagne Ehud is broken by his long ordeal. Finally. He’s been brazening it out, but there are limits to the shamelessness even of an Israeli politico. If only he’d done what I did – go to the U.S., spin out some waffle about the Middle East strategic outlook, throw in a few phrases of steely determination that the Holocaust shan’t happen again (as if anyone would expect the former Israeli Prime Minister to say, ‘Well, why not? It's been a while. Let’s have another Holocaust.’), and charge them fifty grand to listen to it while they eat their shrimp. Their chicken, I mean.

Who needs corruption, when you have a public speakers’ circuit for former politicians?

By the same token, why does Tony Blair insist on keeping his job as Mideast envoy of the Quartet? It’ll take more than a skeletal smile and a familiar glottal “t” in the middle of the word “wha’ever” to extract a Nobel Peace Prize out of this place, I can tell you. What does he need such grief for? He’s one of the best paid speakers in the world (200,000 pounds for a half-hour speech, and 15 million pounds in two years since leaving Number 10.) Forget the Mideast, Tony. Creep off to the U.S. and stay there. After all, that’s the only place in the world where they think the “Prime Minister of England” is a relative of the Queen. It’s probably why they’re paying you the big money. It certainly can’t be because you were so stupid you allowed George W. Bush to fool you into going to war.

Once you’re at the top in politics, you never have to pay for dinner again. But it’s a mistake to think you don’t have to pay for your house. You just don’t have to WORK to pay for your house. A few dates in Chicago, Los Angeles, New York and Florida and I was well on the way to the cost of my villa in Caesarea. That’s what poor old Champage Ehud forgot.

That reminds me, I must send over a few Cubans to him. He's a big afficionado, but he might be running low. He’ll need them, given how much smoke he’s going to have to blow to cover all this up.

The real speaker’s fees are only for the top guys. The Prime Ministers whose reputations were soiled by Iraq, the Presidents who soiled their intern’s dress, the former US Secretaries of State who were so stupid even George W. Bush could fool them into going to war in Iraq, the …uh, the movie stars (Nicole Kidman got $435,000 to speak to a global business conference) who can teach us how to cry without having our nose-jobs run and still look fabulous.

Maybe I could look up Kidman’s speech on Youtube. I might be able to figure out how to use some of it for next year’s Holocaust Remembrance Day speech – this week at the memorials I feel I was a bit “same same,” having used up my best stuff at Auschwitz a couple of months ago. Nicole was very good in “Moulin Rouge!” Sometimes I dress as a woman and sing “One Day I’ll Fly Away” to my wife Sara, but she doesn’t seem to get the message. The messages, I mean.

Yes, speaking fees are where it’s at. Small fry have to promote themselves by writing blogs and op-eds, and even authoring their own books, as if ghost writers didn't exist. Like that writer Matt Beynon Rees. I heard that sometimes he even speaks to people for nothing, just because they want to hear him and he wants to talk about his books.

Now that’s really corrupt.

Published on April 16, 2010 06:14

•

Tags:

chicago, corruption, crime, crime-fiction, cubans, florida, george-w-bush, holocaust, iraq, israel, los-angeles, matt-beynon-rees, middle-east, moulin-rouge, netanyahu, new-york, nicole-kidman, nobel-peace-prize, olmert, one-day-i-ll-fly-away, tony-blair

April 15, 2010

Stealing the novel

If there’s one thing that authoring a series of novels will teach you, it’s that you can’t wait for inspiration. But you can prompt it, give it little electric shocks that’ll keep it bubbling within you. Here are a few methods I use to do that.

If there’s one thing that authoring a series of novels will teach you, it’s that you can’t wait for inspiration. But you can prompt it, give it little electric shocks that’ll keep it bubbling within you. Here are a few methods I use to do that.I go to the places I’m writing about. I talk to people who might be similar to (or even the basis for) my characters. I read about them and their world. I engage in the same activities in which they specialize. But I also read about entirely different subjects – so long as they’re extremely well-written.

Some of these ideas sound self-evident. I’ve written a series of Palestinian crime novels, so it stands to reason that I’ve spent the last decade and a half in Gaza, Bethlehem, Nablus, Jerusalem, tasting and smelling and talking and looking. I even force myself to read the drivel that gets written about this place in journalism and nonfiction—occasionally I come across something good, but mainly it just gets me down. How many times can you listen to a mediocre pop song? Well, that’s how most Middle East journalism sounds in my ear.

For a novel I have coming out next year about Mozart, I learned to play the piano. I learned that I wasn’t much good at it, but I also saw inside the music in a way I couldn’t have done merely by listening.

Not so obvious, however, might be the wide reading. A number of writers I’ve met or read about say they don’t have time to read anything that isn’t directly related to their research. In other words, if I’m writing about Berlin, it’s goodbye to Raymond Chandler for the next 12 months.

Well, T.S. Eliot wrote that “Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal.” I can look back at my literary efforts as an undergraduate and see what imitation there was throughout all of it. Now I’m mature (I try to fight it; I work out; but I concede, I’m maturing…) and I’ve figured out how to steal.

What Eliot meant was that it takes a while, as a writer, to realize how to make things your own. That means going beyond the plagiaristic imitation of youth, which is humble and filled with homage, to the confident sense that whatever you see another writer do, you can do it better. Then when you read something good, it doesn’t appear in your work as the same thing—it spurs you to develop your own spin on the thought that’s provoked in you by what you’ve read.

Let me give you an example. I challenge any one of you to show me a contemporary writer who can build a character in a fuller, more convincing manner than Hilary Mantel, who won the Booker Prize last year for her masterful “Wolf Hall.” If anything, her 1992 classic “A place of Greater Safety,” a novel about the French Revolution, is even more amazing than her now-famous prize-winner.

“Greater Safety” tells the story of the entire revolution through the characters of Robespierre, Danton and Desmoulins. From their childhoods to (it’s a historical novel so I don’t have to give any spoiler alerts) their executions. Each of them is built slowly, and we see their character arc in a way that even they don’t—watch their idealism tainted with violence, until it turns on them. Because we take that journey with them, we care more deeply for them, even as they become murderous and unjust.

The “stealing” comes in whenever I see a point that Mantel uses to build that empathy. Robespierre, we learn, always carries a tiny copy of Rousseau in his pocket. Some time later it’s on his desk and Desmoulins notices it. Just one sentence. A couple hundred pages later someone quotes Rousseau against him and only his close friends understand that he’s entirely defeated. We know he’s a man who has bent principles for his friend Desmoulins, but he can’t desert them completely. It’s a choice between Desmoulins, whom he loves, or the book that he keeps close to his heart. Books always win in contests like that.

That doesn’t make me want to replicate the exact same thing in my next book – that’s what I might’ve tried when I was 19. Instead, I think of ways in which to send a signal to the reader. To plant an object that inspires a character, that takes them on the path on which we follow them in the novel. Until ultimately it underlies their collision with another character; makes compromise an impossible undermining of everything they believe about themselves.

That’s stealing, and it’s a good thing to do.

You can find such moments in the small factoids of history books, if you’re researching a period, or in nonfiction. It’s in poems, where a phrase about a frieze on an urn (“Thou still unravished bride of quietness”) will spark a thought about your memories of your own wedding or of a sexual exploit which you can use for a character in your book.

A writer whose obvious focus is character would be the most direct place to start. In other words, not the kind of ultra-bland snoozing that appears in the short fiction of The New Yorker, which always seems to be written as though it were designed to mimic a relatively dull person telling you a story in a cocktail party or at the counter of a bodega.

Choose something with sweep, like Mantel. Someone with an eye for a mordant detail, like Graham Greene in “The Honorary Consul.” Someone who shows you an entire, devastated culture through the eyes of one man, like Martin Cruz Smith’s investigator Arkady Renko.

A novel’s like a marathon. Stop and sit down at the side of the road and no amount of sprinting will get you to the finish line. You have to write every day and once you’re started you can’t stop. “Stealing” is a way of warming up for the long run.

Published on April 15, 2010 00:12

•

Tags:

a-place-of-greater-safety, berlin, bethlehem, booker-prize, crime-fiction, danton, desmoulins, gaza, graham-greene, hilary-mantel, historical-fiction, israel, jerusalem, martin-cruz-smith, middle-east, mozart, nablus, novels, palestine, raymond-chandler, robespierre, t-s-eliot, wolf-hall, writing

April 11, 2010

A who's who of Israeli corruption

In a small country you can find all the important decision-makers sweating in one gym.

In a small country you can find all the important decision-makers sweating in one gym. JERUSALEM — The heads of all the crime families in New York used to get together every Wednesday night at the Ravenite Social Club on Mulberry Street in Little Italy. If you were looking for an Israeli parallel, you could do worse than the gym I work out at.

The Cybex Club at the David’s Citadel Hotel has a nice view of the Ottoman walls of Jerusalem’s Old City. It’s also where the legal, political and business elite come to sweat (actually, being Israelis, they spend as much time talking as they do exercising). As I labor through my sit-ups, I’m surrounded by prime ministers, ministers, night club owners and restauranteurs, private detectives — all of them either under investigation, out on parole or formerly the targets of corruption probes.

The latest member of the Cybex cabal to hit the headlines is Uri Messer, who was arrested this week on charges of serving as an intermediary in an alleged bribery scheme. One leg of the alleged scheme is a former Cybex jock, ex-Prime Minister Ehud Olmert. (The manager used to open the gym half an hour early in the morning so Olmert could run 10 kilometers on the treadmill before 7 a.m.)

The gym is instructive, because it puts Israel into perspective. What you see of Israel on the news makes the place seem so central to world politics that it’s easy to forget what a tiny country it is — not just geographically, but also socially. Maybe there’s a gym or a bar in some of the smaller U.S. states where you might see pretty much everyone who counts in the decision-making of that region. But on a national level, there’s no such place. Washington’s just too big.

In Israel, a handful of places provide a social nexus for the elite, funneling the influence and connections that dominate a $200 billion economy, and Cybex is one of them. (Vermont, by contrast, is a $27 billion economy, one of 26 U.S. states with a smaller economy than Israel.)

Messer, a close friend of Olmert, admitted a couple of years ago to keeping a slush fund of hundreds of dollars in cash in a safe for then-Prime Minister Olmert. This time he’s charged with facilitating a bribery scheme to circumvent planning restrictions in Jerusalem.

The judges in Olmert’s corruption trial are currently deciding how to rearrange forthcoming hearings, given the new evidence surrounding Messer. The former prime minister already faces trial on three separate corruption investigations and is charged on counts of aggravated fraud, fraud, falsifying documents and tax evasion.

From my window I look across the valley at the result of this latest alleged bribery scandal: the Holyland complex, a weird Lego creation of apartments strung along a ridge with a 15-story tower beside it. Every committee and planning group in the city hated the idea, but it went ahead.

Now maybe we know why.

Well, Israelis knew all along. They understand the size of their economy is and how a relatively small group of men manages to maintain a hold on the profits. They also know that construction — fueled by rich American and French Jews who buy with their hearts, rather than their heads, for a sentimental foothold in Israel that they occupy for a few weeks a year — has been the easiest source of such profits. And the one most susceptible to corruption.

How pervasive is that corruption? Look at who else is implicated in the probe that snared Messer. The former municipal engineer for Jerusalem, Uri Sheetrit, at first opposed the Holyland project. Then he became a big proponent. What changed his mind? The police think they know. They’ve remanded him for a week.

It all struck me long before these allegations came out against Messer. You might say it’s instinctive to recognize it once you observe how the place works. This is a country where the average wage is $2,000 a month and a BMW costs $300,000 including taxes. The parking lot at the David’s Citadel was always full of BMWs, and I simply assumed such money was unlikely to be entirely licit. There wasn’t even the chance that these were bankers — which would make them unsavory but, grudgingly, legal earners — because Israel’s financial center is in Tel Aviv.

Then one day my Russian personal trainer was stretching my pectorals and whispering about the other people who happened to be in the gym at that moment. Given that it wasn’t very crowded, it was quite a list:

“That guy’s a private detective. He just got out of jail for blackmailing someone. That’s one of the two owners of the club I go to on Fridays. He’s been to jail for tax evasion. That guy owns a restaurant and all his partners went to jail for tax evasion.”

“Who? That guy?”

“No, the one next to him. The one you’re referring to owns a different restaurant. He actually was jailed for tax evasion. That woman was the education minister — clean, as far as I know. That guy’s Uri Messer.”

“The little guy with the gray beard who keeps waving to everyone?”

“Yeah, him. On the treadmill. He’s tight with Olmert.”

My trainer didn’t need to introduce the other man, walking on the treadmill with his half-glasses on the end of his nose and his head bent to a sheaf of papers. It was Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Published on April 11, 2010 05:21

•

Tags:

benjamin-netanyahu, bribery, corruption, crime-fiction, cybex-gym, david-s-citadel-hotel, ehud-olmert, fraud, gym, holyland, israel, jerusalem, little-italy, mafia, middle-east, new-york, ravenite-social-club, uri-messer, vermont

April 8, 2010

Bibi's Bedtime Book: The Secret Diary of Prime Minister Netanyahu

No Palestinian state this week. Don’t really know why not. At this point I’d be happy to sign off on anything at all, just to get it off my hands. I’ve told the Americans that, but they seem convinced I’m some kind of hardliner—they think I’m bluffing when I say “Barry, where do I sign?” I think it’s because of the way I lift my eyebrow in my official photograph. I thought it was sexy and devil-may-care, but apparently it makes me look hawkish and too clever for my own good.

No Palestinian state this week. Don’t really know why not. At this point I’d be happy to sign off on anything at all, just to get it off my hands. I’ve told the Americans that, but they seem convinced I’m some kind of hardliner—they think I’m bluffing when I say “Barry, where do I sign?” I think it’s because of the way I lift my eyebrow in my official photograph. I thought it was sexy and devil-may-care, but apparently it makes me look hawkish and too clever for my own good.It’s been Passover here in Israel. I’ve had to smile and shovel down the usual seasonal foods. I even had to sit through a seder. We were slaves in Egypt, etc., on and on for six hours. You’d have thought we’d be done with all that now. It’s like Zionism never happened.

I gather they had a seder at the White House, too. Without me. Maybe I’ll have Kwanzaa at my villa in Caesarea this year and I pointedly won’t invite Obama. On second thoughts, the rabbis wouldn’t like it. They don’t like holidays where you sing in tune – strictly tuneless, out of time, Jewish mumble-singing is more their thing.

I went down to Shaul’s Shawarma stand to mix with the people. Mofaz insists on meeting there – he set the place up as something to fall back on if he doesn’t get to be Prime Minister instead of me; he could retire, stop wearing his colorless rep ties, and instead bore all his customers with stories of how his political career was a victim of the Ashkenazi establishment. He served me some kind of stinking horsemeat impacted under high pressure into a block so that it looked like an actual cut of meat. I called him “my brother,” which is how Israelis who aren't from the Ashkenazi elite like to refer to each other, and went off to find a breath mint. I suppose he thought the joke was on me.

I’ll eat anything, provided someone else is paying, of course. That’s why I got into politics. Even when I wasn’t in office, at the end of a meal, I’d pat my jacket and say, “Sara, did you bring my wallet?” And some guy from Los Angeles would always reach out and say, “No, no, Mister Prime Minister, let me.”

Why do they say “Mister Prime Minister?” Or Mister President? These are nouns, aren’t they? You don’t call the man who fixes your toilet “Mister Plumber.” On the occasions when I’ve met this Rees fellow I didn’t call him “Mister Writer.” It’s not even necessary for my wife to call me “Mister Big Shot” when she’s upset with me. “Big Shot” would do. I suppose “Mister” adds a grace note to her sarcasm.

Mainly such things are all about self-aggrandizement. Still, just so long as they pick up the tab for my steak and lobster, I’ll let it slide.

Talking of self-aggrandizement, Defense Minister Napoleon puffed out his little chest and humiliated the head of the army this week. Something silly to do with not extending the chief of staff’s term because he didn’t kiss up (figuratively, because in reality everybody would have to bend down to kiss that shortass). Perhaps he’d neglected to call him “Mister Defense Minister.” Or “Mister Bonaparte.” Or “My Emperor.”

Anyway, someone else’s troubles are usually a sign that someone’s too busy elsewhere to ruin my week. So it’s good news. I’ve barely been in the headlines all Passover.

Why am I shy of the press? I keep getting slated for being a hardliner, that’s why. Yet it’s little Napoleon who flattened Gaza and ballsed up the “peace process” a decade ago. I thought we were rid of him once he got onto the $50,000 a night speaking tour in the US. I suppose he had to come back for a while to keep in the public eye, then in a few years he can be President, which isn’t a real job (though I haven’t told Peres that.)

No, I don’t understand the press. Take that fellow Matt Beynon Rees. He came to my office a while back and smoked one of my long Cubans. I told him about my interpretation of the work of Emmanuel Kant, but all he wrote about in the end was a few things I’d said about building in our settlements in Judea and Samaria.

I gather Rees also concluded that journalism is a waste of time. He’s writing fiction now. Crime novels about a Palestinian detective. I must take a look at them. I gather my pal Arafat doesn’t come out too well in one of them called “The Samaritan’s Secret”. A shame. I’m rather fond of the sneaky old “ra’is”, of blessed memory.

Maybe I’ll give it all up and write some fiction myself. About an Israeli Prime Minister who’s misunderstood, who only wants to make people happy and give everyone he talks to exactly what they want. A state for the Palestinians. More ritual baths for the ultra-Orthodox. A free Mazda for the 6 percent of Israelis who don’t already own one. The Legion d’Honneur for the Imperial Defense Minister.

Yes, I might just write a book like that. I think it’d be a good read.

But no one would believe it.

[Prime Minister Netanyahu will be continuing to disclose his most secret thoughts exclusively on this blog].

Published on April 08, 2010 01:12

•

Tags:

barack-obama, benjamin-netanyahu, bibi-s-bedtime-book, crime-fiction, ehud-barak, israel, israeli-politics, israelis, matt-rees, palestine, palestinians, shaul-mofaz, the-samaritan-s-secret