Matt Rees's Blog, page 26

April 6, 2010

The war Israelis and Palestinians plan

I posted this on Global Post. JERUSALEM — There’s an old Arab aphorism: “A man with a plan takes action; a man with two plans gets confused.” Apply that to the Israelis and to the Palestinians, and the nonsensical sequence of recent events in the Middle East starts to fall into a comprehensible pattern.

I posted this on Global Post. JERUSALEM — There’s an old Arab aphorism: “A man with a plan takes action; a man with two plans gets confused.” Apply that to the Israelis and to the Palestinians, and the nonsensical sequence of recent events in the Middle East starts to fall into a comprehensible pattern.It’s not a pleasant pattern, because it leads to war.

First, before we get to the fireworks, let’s recap all the nonsense.

The Palestinians refused to talk to the Israelis from December 2008, when a relatively centrist Israeli government made a peace offer the Palestinians rejected. Since then, small economic reforms and big U.S. security aid have made life in the West Bank fairly free of violence. Better, for sure, than life in Gaza, which is still a mess more than a year after the Hamas-Israel war there.

Israelis elected a center-right-dominated parliament a year ago, and Benjamin Netanyahu formed a rightist cabinet. He refused to halt building in Israel’s West Bank settlements, as President Barack Obama demanded. Even when forced by Washington to put a transparently fake freeze on construction he declined to include East Jerusalem.

The Palestinians wouldn’t restart direct peace talks until there was a freeze on the Israeli neighborhoods of East Jerusalem. So the Americans eventually persuaded them to have indirect talks. Without much enthusiasm, the Palestinians agreed.

Why no enthusiasm? Leading Palestinians, including chief negotiator Saeb Erekat, had already started to talk about a new failed round of talks leading quite simply to a “one-state solution.” That means, no division of the land, just a single state in what’s now Israel, the West Bank and Gaza. One adult, one vote. Soon enough, of course, that means no Jewish majority and the end of Israel as a Jewish state.

Meanwhile, Israel largely escaped the financial crisis of the last two years and its citizens spend little time fretting about the Palestinians. In Tel Aviv, the discovery of old bones by workers building an underground emergency room for a hospital led last month to an attempt by ultra-religious politicians to block the construction, and protests by locals who cried out against religious coercion.

No such mass protests against continued building in the settlements. That proceeds, even to the extent that during the last month announcements of new construction in East Jerusalem have caused a major crisis in relations with Washington. In one case, the planned building of a mere 20 apartments in an Arab neighborhood of East Jerusalem forced Obama to take time out of his undoubtedly busy day to discuss it with Netanyahu.

There’s more nonsense, but let this much suffice for now.

Back to the Arab aphorism. Who has a plan, and who’s confused?

It’s clear that most Israelis and most Palestinians are living in denial — a kind of confusion, because it takes the illusion of current calm for a sustainable and welcome period of peace.

Israelis know the settlements can’t go alongside a two-state solution, but they don’t choose one or the other.

Palestinians know that the way to stop the settlements eating up the hilltops around their towns is to strike a deal now and rule their own state, but they won’t do it so long as life is relatively good and the international pressure is all on Israel. Leaders of Fatah and Hamas have called for a “third intifada” several times in the last four months — not for renewed talks, only for renewed violence. But a mere handful of kids came out to throw rocks and Molotov cocktails.

With no sense of urgency on either side, Western diplomats shake their heads and try to nudge the two nations to the negotiating table. It’s time to realize that neither side wants talks.

While most Israelis live in denial, a sizeable minority pushes for more building in the West Bank and East Jerusalem. They’re not building so that they can later give up that land and see all the money they’ve pumped into their real estate wasted. The purpose is to make the West Bank inseparable from Israel. To kill the two-state solution.

In that scenario, either the Palestinians agree to be second-class inhabitants of the area -- fat chance -- or they leave. Well, with a little nudge.

On the Palestinian side, negotiations seem unlikely to lead to the satisfaction of every single demand. So the one-state solution starts to look good to them, too. However, second-class citizenship isn’t an option, and neither is leaving.

That’s the collision course Western diplomats refuse to countenance. When envoys talk about getting the “peace process on track,” it sounds good. But that process has been trucking along since the early 1990s. Peace has been getting further away. The “process” allows for a sense of activity, while all the time events — settlement construction, terror attacks — make it harder to draw lines on a map and make the populations secure.

It’s time to figure out a new diplomatic strategy to deal with the Israelis and Palestinians. One that’s based on the assumption that, in the longterm, they’re expecting war.

Published on April 06, 2010 02:02

•

Tags:

arab, barack-obama, benjamin-netanyahu, conflict, crime-fiction, east-jerusalem, fatah, gaza, global-post, hamas, intifada, islam, israel, israelis, jerusalem, jews, journalism, middle-east, palestine, palestinians, settlements, tel-aviv, war

April 5, 2010

Times thriller roundup: Omar Yussef 'most beguiling of current sleuths'

Set in a pulsating, multicultural city, Matt Rees’s The Fourth Assassin relocates his Palestinian series hero Omar Yussef to a wintry New York, where a UN conference provides a pretext for visiting his son Ala; but when he reaches Ala’s Brooklyn apartment, he discovers the headless body of one of his roommates. Yussef teams up with a local cop to investigate, and confirms his status as one of the most beguiling of current sleuths as they try to establish whether the victim was killed by a drug dealer, a romantic rival or an Islamist cell intent on a high-profile assassination.

There's also a review of Sophie Hannah's latest. I did a joint reading with her last year in a remote spot in Derbyshire. Her novel was about infidelity. She confessed that she'd probably have an affair with any man who asked her to do it in the afternoon, but complained that such offers usually come late at night when she really just wants to sleep. I thought it was the most refreshing perspective on extramarital affiars I've heard for a long time and probably a good tip for would-be philandering males.

The other reviews include new ones from Nicci French and Lee Child.

Published on April 05, 2010 00:30

•

Tags:

brooklyn, crime-fiction, derbyshire, drugs, islamists, jenny-cooper, joan-brady, john-dugdale, joseph-kanon, lee-child, london, matt-rees, new-york, nicci-french, peter-temple, reviews, sophie-hannah, sunday-times, the-fourth-assassin, thrillers, times-online

April 2, 2010

An Islamic Romeo and Juliet

Since 9/11, journalists and writers have tried to make sense of the extremists committed to the destruction of the West and, often, that of their own societies in the Middle East. Mostly this has meant “going inside” the world of those extremists, giving us the inner life of suicide bombers or of the “American Taliban.”

Since 9/11, journalists and writers have tried to make sense of the extremists committed to the destruction of the West and, often, that of their own societies in the Middle East. Mostly this has meant “going inside” the world of those extremists, giving us the inner life of suicide bombers or of the “American Taliban.”It’s a worthy premise, because it’s aimed at comprehending people who are frequently written off as bestial, bloodthirsty psychopaths, as though they’d been born that way. As a journalist with 14 years experience in the Middle East, I’ve written such stories often enough. But in my new novel I decided to highlight the desperate world of Arabs who struggle against the extremism that drags them toward their inevitable, tragic end. This is the most profound way of humanizing Arabs, because it shows them clinging to the very things that make them just like us, rather than succumbing to the ugliness of a politics that sets them against us.

That’s why I see my new crime novel, “The Fourth Assassin,” as an Islamic “Romeo and Juliet” set in the context of a political assassination plot in New York. I want to put a human face on Arabs, who’re so often seen as stereotypical terrorists. But I want to focus less on the pain and confusion that leads to hatred, and instead to reveal the love that can provide hope for Arab people in the face of so much destruction and division. To illustrate, for Western readers, what they’re up against, too.

“The Fourth Assassin” begins with Omar Yussef, the hero of my previous three Palestinian crime novels, arriving in New York for a UN conference. He uncovers an assassination conspiracy involving some of his former pupils from back home in Bethlehem. It unfolds in the neighborhood of Brooklyn called Bay Ridge. With its growing Palestinian community, Bay Ridge is in fact becoming known as “v”.

As he delves into the background of the plot, Omar looks for political explanations. That’s what journalists and writers typically do when they examine the Middle East. But gradually Omar sees that there’s a love story behind what’s happening. A love story between a young Sunni Muslim who has been sucked into the assassination plot and a Lebanese Shia girl who wants to enjoy the freedoms of American life.

The book’s a crime novel, so I’m not giving anything away when I say that Omar sees these lovers as tragic, somehow doomed by the politics around them. But he acknowledges – as the lovers do – that their human connection is so important that it’s worth any sacrifice. Just as Romeo does when he rails against the family politics that would deny him his Juliet and designate such divisions as fated. “Then I defy you, stars,” he calls out.

With Romeo and Juliet, the doom that surrounds them isn’t the point of the play. It’s their hope and defiance that draws them to us. If Shakespeare had written a three-hour examination of the political conflict between the Montagues and the Capulets, I don’t expect we’d pay it much attention these days. Neither would we be interested in the play had it focused on Tybalt, Juliet’s hot-headed, murderous cousin, or Mercutio, the pal of Romeo who shouts “a plague on both your houses” as he dies. Yet that’s exactly what journalists and writers give us in their attempts to “explain” the Arab world.

Love is what helps us to understand those who seem otherwise to be set against us. That’s what Omar Yussef learns in “The Fourth Assassin.” I hope the novel will help my readers see that love is as much a part of life for Arabs as the violence that dominates their portrayal in the news pages.

Published on April 02, 2010 02:05

•

Tags:

9-11, american-taliban, arabs, bay-ridge, bethlehem, brooklyn, crime-fiction, islam, lebanon, middle-east, montagues-and-capulet, new-york, omar-yussef, palestine, palestinians, romeo-and-juliet, shakespeare, taliban, the-fourth-assassin

March 31, 2010

Israeli settler sect: Messiah is coming

GIVAT ONAN, West Bank—On this windblown outpost in the hills north of Jerusalem, a small group of Israeli settlers strives to bring the day of redemption promised, as they believe, in the Bible.

GIVAT ONAN, West Bank—On this windblown outpost in the hills north of Jerusalem, a small group of Israeli settlers strives to bring the day of redemption promised, as they believe, in the Bible.A controversial sect shunned by nearby Israeli settlements, the Brothers of Onan believe that by “spilling their seed” on the land of the ancient biblical Jewish homeland, they will hasten the coming of the Messiah. With the Israeli communities of the West Bank considered illegal under international law, the Onanists are the outcasts among outcasts. But they’re unperturbed.

“We can never give up this land,” says the group’s leader, Rabbi Meir Gedalia Kaplowitz. “You can ejaculate all you want in Tel Aviv or New York, but the Holy One, blessed be He, wants us to perform the miracle here.”

Kaplowitz sits in a messy caravan on a windy hilltop, taking a brief break from his endless routine of Talmud study and self-abuse. Wild-eyed and gaunt, he is the picture of the stereotypical Israeli settler extremist. Only, if anything, even more wild-eyed and gaunt.

The sect takes its name from the biblical Onan, who was ordered by his father Judah to impregnate Tamar, his brother’s widow, and to pass off the resulting children as belonging to his deceased brother. Not wanting to have children he couldn’t regard as his own, Onan fornicated with Tamar but at the moment of ejaculation he “spilled his seed.” God punished this disobedience by killing Onan.

Onanism has become a term used to describe such coitus interruptus, though it is also used for masturbation. In the Hebrew spoken on Givat Onan, masturbation is “onanut.”

“We’re proud to use that word for what we do,” says Haim Hercz, who occupies the caravan next to Kaplowicz. “But it's not all about Onan. Sometimes we call it flogging the Pharisee or chafing the camel. We have a sense of humor, just like people who have sex with women. But anyone can do that five or six times a day. We know that what we’re doing has a deeper purpose, and that’s what keeps us going.”

The Brothers of Onan celebrated Passover with a traditional Orthodox seder meal this week. (“Frankly it was nice to have something else to keep us occupied for six hours,” says Hercz.) But next week they plan to take their struggle to Tel Aviv, where they will pray and “shoot their short Uzis” outside the Israeli Defense Ministry to protest any restrictions on building in the settlements.

Successive Israeli governments have justified new construction in the West Bank by arguing that they are only satisfying “natural growth,” whereby the growing families of settlers must be accommodated with new homes. “Obviously that’s not fair on us,” says Kaplowitz.

Israelis who oppose the settlements say the Brothers of Onan are more than a dangerous fringe group. Orla Mohel, a Tel Aviv masseuse, founded Wank Watch to combat the influence of the group. “I’m concerned that a lot of people in Tel Aviv will see them as harmless ‘frotteurs,’” she says. “But they celebrate a story from Genesis in which a father forces a brother to have sex with his sister-in-law, tries to get a third son to marry her, then has sex with her himself.”

Harvard Law School professor Alan Dershowitz writes in his book “The Genesis of Justice” that Onan probably had non-penetrative sex with Tamar, or maybe anal sex.

“I didn’t go to Harvard and I’m not a lawyer, so I'm no expert on the Bible or anal sex,” responds Mohel. “But these Onanists also don’t want to give up the West Bank, which prevents a peace deal.”

Rabbi Kaplowitz contends that he’s no extremist. Rather he claims to represent the mainstream in Israel. “There are only a couple of dozen of us here, but there are thousands of others who’d like to join us. We’re out here in the lonely desert hills, doing something important for the redemption of the world. It’s not easy. We have very slow internet and sometimes youporn.com goes down for minutes at a time. Our thing is exhausting without visual aids.”

US Mideast envoy George Mitchell has condemned the Givat Onan outpost as “illegal under international law and pretty skeezy.” Mitchell also cited the 4th Century sage St. Athanasius of Paros as saying that “to have coitus other than to procreate is to do injury to nature.”

Kaplowitz rejected the criticism. “I don’t take sex advice from Greeks,” he said.

Published on March 31, 2010 23:59

•

Tags:

alan-dershowitz, april-fools, bible, book-of-genesis, george-mitchell, givat-onan, israel, judah, new-york, onan, onanism, peace-talks, self-abuse, settlements, talmud, tamar, tel-aviv, the-genesis-of-justice, west-bank

March 30, 2010

Crime fiction with a vengeance

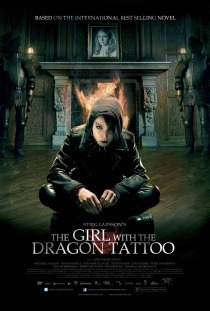

The Swedish title of Part I in Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy was “Men Who Hate Women.” Which shows that you can write a huge international bestseller and not know why people would read your book.

Larsson’s U.K. publisher changed the title to “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo.” With his original title, Larsson would’ve been a posthumous hit (he died in 2004 of a heart attack at the age of 50) in Sweden, where he was well-known as a Communist campaigner against racism and the extreme right. But he probably wouldn’t have beaten the rest of the recently popular pack of Nordic crime writers from Henning Mankell to Jo Nesbo.

It’s the title change and its focus on a character who’s both aide to the sleuth and victim of violent crime that made Larsson the second-biggest selling novelist in the world last year, after Khaled “A Thousand Splendid Suns” Hosseini.

All the other Nordic writers focus on the detective, which is after all the traditional route in crime fiction. We’ve bought 40 million Mankell novels to follow Inspector Wallander as he mopes his way to the villain’s doorstep.

You could read Larsson’s book like that, too: Mikael Blomqvist, magazine editor and irresistible ladies man, is commissioned to unravel an old murder mystery on a remote Swedish island. But it’s his assistant, a rape-victim filled with hate for her persecutors (the men who hate women), who’s really the heart of the book.

While Blomqvist is working the island case — a fairly typical “closed room” mystery, similar to the ones in which Agatha Christie’s sleuths used to inform us that “one of the people in this room is the murderer” — Lisbeth Salander is secretly setting up the vigilante vengeance that provides the book’s smooth twist in the tail.

No one reads beyond page 50 for Blomqvist. Just Salander. Which is why the work of a Swedish Communist is now being taken up by Sony Pictures for a Hollywood version probably to be directed by David Fincher (who made “Zodiac”), produced by Scott Rudin (“No Country for Old Men”) and scripted by Steve Zaillian (who won an Oscar for his adaptation of “Schindler’s List”).

So many readers warmed to Salander — the series has sold 27 million copies in 40 countries so far — that all three novels in the series have been made into movies in Sweden already. The first came out in the U.S. this month and the other two will be released in the summer.

USA Today urged viewers not to wait for the Hollywood version, calling the Swedish flick “indelibly great.” (Indelible, like a dragon tattoo, get it?) In an example of praising the atmosphere while half-overlooking a flaw in the central element of the movie, reviewer Claudia Puig wrote: “Though the relationship between Lisbeth and Mikael isn't fully developed and a few plot coincidences feel contrived, The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo artfully and intelligently fuses a punk sensibility to an epic tale.”

Maybe it’s wise not to wait for Hollywood, if it’s punk sensibility that floats your boat.

Of course, Puig’s quibble is a red alert for likely scriptwriter Zaillian. You have to buy Lisbeth and Mikael, otherwise “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo” is really a drag.

Let’s go back to the novel.

It’s 554 pages in my British softcover version — the first book of three equally bulky volumes, in case you haven't already read them. Much of that is the sort of thing you might read in a campaigning magazine such as Expo, the publication of which Larsson was the editor. It’s written in the chatty simple language that magazine — and, increasingly, thriller — editors like, because it’s direct and lacking in imagery, so you keep turning the pages. You’ll never have to stop and say, “Hey, ‘She gave me a smile I could feel in my hip pocket.’ Nice image, Stieg Larsson.”

(You won’t, because that’s Raymond Chandler. “Farewell, My Lovely,” chapter 18.)

That’s no problem for a screenwriter. Hollywood can do its own wisecracks, and other literary imagery is usually dropped before an actor opens his lips.

Zaillian can surely cut most of the lengthy portions of the book which Larsson probably liked best. There are long disquisitions on rape statistics in Sweden and background segments on the local business scene. Take Lisbeth’s repeated rape by her legal guardian. It leads to a page and a half of this:

“Guardianship is a stricter form of control in which the client is relieved of the authority to handle his or her own money or to make decisions regarding various matters.”

There’s more: “Taking away a person’s control of her own life … is one of the greatest infringements a democracy can impose … For the most part the Guardianship Agency carries out its activities under difficult conditions … Occasionally there are reports that charges have been brought against some trustee or guardian who has…”

If Karl Marx had written “Das Kapital” in the evenings as a thriller, it might’ve had more zip than Larsson’s preachy liberal legalisms. Just so long as Engels had changed the title to “The Guy With the Dialectic Theory.”

Niels Arden Oplev’s Swedish movie version boils down to a 152-minute procedural that’s quite televisual in its look. That’s too long for a Hollywood thriller, so Zaillian will have to pare it even more.

So what’s left when you take out the tedium? (Don’t get me wrong, a lot of readers tell me they love the tedious parts of Larsson. They soothe you when you’re sick in bed or trying to take your mind off work at the beach. You forget your troubles, immersed instead in how rotten it is to be a Swedish woman.)

Which returns us to Lisbeth. She drives the narrative and, perhaps because women fall too easily for Mikael, she’s where all the sexual tension lies, too. (The book is big on titillation and the Swedish movie doesn’t skimp on a graphic rape scene.) It’s Lisbeth who’ll take you beyond the statutory confrontation with the villain. She makes the book memorable.

Better hope Hollywood doesn’t change the title.

(I posted this on GlobalPost.com)

Published on March 30, 2010 04:43

•

Tags:

a-thousand-splendid-suns, claudia-puig, crime-fiction, das-kapital, david-fincher, farewell-my-lovely, henning-mankell, hollywood, inspector-wallander, jo-nesbo, karl-marx, khaled-hosseini, lisbeth-salander, mikael-blomqvist, millennium-trilogy, movies, niels-arden-oplev, no-country-for-old-men, nordic-crime-fiction, raymond-chandler, reviews, schindler-s-list, scott-rudin, steve-zaillian, stieg-larsson, swedish-crime-fiction, the-girl-with-the-dragon-tattoo, usa-today, zodiac

March 25, 2010

Back to Israel: Recall what's foreign

When you live in a foreign place, it can become home. You forget how foreign it is.

When you live in a foreign place, it can become home. You forget how foreign it is.Then you go to another foreign country, only to discover that it doesn’t seem so foreign. And you realize that the place you live actually IS extremely foreign.

That’s what happened to me during the last week, when I toured Germany to read from my third Palestinian rime novel THE SAMARITAN’S SECRET (just published by CH Beck Verlag as “Der Tote von Nablus.”)

I was in Munich station when I noticed in a pastry shop that Germans spell pretzel with a B (“Brezel”). I felt a little blown away, as though I’d been living a lie all these years offering my son “pretzels.” But that’s as foreign as Germany got. Otherwise, this Welshman felt right at home there.

Right off the plane on my return to Israel, however, the country which has been my home since 1996 and where I’ve grown accustomed to the way people behave, the foreignness hit me anew.

Actually even before that. The fellow in the seat next to me on the flight from Frankfurt kept talking to me – Israelis have a way of talking a lot and they can also be rather clueless about my oh-so-subtle signals that I’d rather read my book. While I was eating, he reached over and took part of my bread roll with a smile and gentle touch of my forearm. (Bread is something you share in Middle Eastern meals, although it usually applies to pita and flatbread, not to tiny airline rolls. This was pretty extreme space-invasion, even for a Middle Easterner, but the reassuring friendly gestures while he was taking advantage of me were very familiar.)

Then in the airport, the dimensions of personal space shrank from the yard kept by Germans to an elbow-brushing, back-nudging Middle Eastern minimum. I smiled, because the Tel Aviv airport is very flashy and new – you could be anywhere in the world. But it’s most definitely not the unflustered calm of Dresden airport, where I boarded my first flight of the day.

Arrival in a “foreign” country means a lot of things that’ll sound deeply negative – or at least they’ll sound like I’m being negative. The shoving and noise and the passport lines where people don’t actually wait in line but prefer to edge around you. But I’m not entirely negative about them. I like it (mostly), because I enjoy being an outsider. To be sure, I don’t think I’d like it much if I looked around and thought, “These are my people. This is my culture. This is ME.”

Then, I expect I’d want us to be more organized, more respectful of each other, less suspicious, more…foreign.

As I emerged into the humidity of the plains between Tel Aviv and the Judean Hills, it struck me that “foreign” countries are simply the ones where things aren’t even remotely fair. That’s why everyone at the Tel Aviv airport hovers over the baggage carousel, shifting from foot to foot, edging in front of others closer to the bags. It suggests an absolute fear that the bag never will come and, most of all, that if all the bags happened to arrive all at once you must be the first one to grab yours and get away before the other suckers. Life in a “foreign” country is a zero-sum game, in which someone else’s success or happiness comes somehow at your expense and must be envied, hated, usurped.

That’s not a German quality. Germans have a sense that there’s some degree of fairness in their society and it makes relations between them less devious and Machiavellian, less on the make. They drive fast, but they don’t think someone else driving fast is attacking them on a macho level, signaling superiority and disdain for them, and, thus, respond by semi-subliminally trying to run them off the road.

So here I am, back in Jerusalem, back to being a foreigner.

Though I shouldn’t forget that at least Israelis spell pretzel with a P.

(I posted this on International Crime Authors Reality Check, a joint blog I do with some other crime writers. Check it out.)

Published on March 25, 2010 07:35

•

Tags:

blogs, crime-fiction, der-tote-von-nablus, dresden, frankfurt, germany, israel, israelis, jerusalem, middle-east, munich, tel-aviv, the-samaritan-s-secret

March 16, 2010

In Nablus, the price is right

I was tucking into a slice of qanafi at my favorite vendor in the Nablus casbah yesterday when a gang of Palestinian reporters and officials intruded on my guilty pleasure. This was at Aqsa Sweets, which readers of THE SAMARITAN'S SECRET will know as the place favored by the hero of my Palestinian crime novels Omar Yussef because it has a perfect blend of the cheeses of different Syrian and Palestinian goats in its qanafi (topped by semolina and drenched in syrup.)

I was tucking into a slice of qanafi at my favorite vendor in the Nablus casbah yesterday when a gang of Palestinian reporters and officials intruded on my guilty pleasure. This was at Aqsa Sweets, which readers of THE SAMARITAN'S SECRET will know as the place favored by the hero of my Palestinian crime novels Omar Yussef because it has a perfect blend of the cheeses of different Syrian and Palestinian goats in its qanafi (topped by semolina and drenched in syrup.)Mayor Adly Yaish was among the crowd. As he steamed his way through a plate of qanafi, he informed me that he, the Nablus region's governor, and the city's police chief were touring the casbah to draw attention to a law soon to come into effect that'll make it mandatory for vendors to show their prices. It's one of the economic reforms introduced by Prime Minister Salaam Fayyad, a Nablus native, intended to change the chaotic and often corrupt nature of the Palestinian economy.

A few minutes of jawboning with me about their hopes that my books will show the true Nablus (I think they do, but I didn't remind them that I write crime fiction), a forkful of qanafi raised for the cameras, and then the dignitaries were off into the narrow alleys in search of price tags.

I settled in to complete my lunch -- not a balanced diet, I know, but then my mother doesn't read this blog so I don't have to pretend to be watching what I eat. I washed it down with tea from a fellow who wandered in with an enormous pot and a cup of sugar in his apron.

Nablus is famous throughout the Arab world as the best place for qanafi. And Aqsa Sweets is the best qanafi in Nablus, thus the best in the Arab world and, obviously, in the world. You wouldn't know it. The place is floor to ceiling white ceramic tiles, as though they expected to hose it down at the end of the day. Up front there are two big burners with wide trays of orange qanafi. The surly fat kid who serves you slings it onto the table as though he thought frisbees were made of hot goat's cheese and syrup.

As for price, nothing's marked. For 4 shekels (a bit more than a dollar), you get 125 grams of qanafi. It doesn't look like much, but if you try to eat more than that, you'll either stagger out hoping never to see another piece of the stuff in your life, or you might just curl up and die in the corner of sugar-shock.

I went up Mount Gerizim, one of the two mountains whose steep sides form the valley in which Nablus lies. At the top I found my old pal Hosny Cohen, a Samaritan priest, in exultant mood. He's shifting his Samaritan Museum and Cultural Center to a bigger room.

"I've had two tour groups this morning, each of forty people," he said, leaning on his cane and pushing his fez forward neatly over his brow. "I don't have energy for you."

Then he proceeded to talk for an hour without stopping. When I was about to leave, he came after me and said: "I forgot to show you the 'mezuza' we put above the door..."

Which is why I can't help liking the Middle East.

Published on March 16, 2010 10:54

•

Tags:

adly-yaish, aqsa-sweets, crime-fiction, dessert, food, goats, hosny-cohen, mayor, nablus, palestine, palestinian, prime-minister, qanafi, salaam-fayyad, samaritans, syria, the-samaritan-s-secret

March 11, 2010

Why I love clogged Arab toilets better than Amazon Kindles

As I travel the Middle East to research my Palestinian crime novels, I love to come upon a stinking squatting-toilet, its evacuation hole bubbling with dark, sinister turds and the air strong with the scent of barely digested, unhygienically prepared lamb kebab. I adore such a khazi on sight, because no one cleaned it up for me or tried to create an illusion that it was just like a toilet in Manhattan or Munich or my mother’s house.

As I travel the Middle East to research my Palestinian crime novels, I love to come upon a stinking squatting-toilet, its evacuation hole bubbling with dark, sinister turds and the air strong with the scent of barely digested, unhygienically prepared lamb kebab. I adore such a khazi on sight, because no one cleaned it up for me or tried to create an illusion that it was just like a toilet in Manhattan or Munich or my mother’s house.That toilet is suddenly all around me and it’s real, down to the ragged little cloth and the old watering can for washing myself afterwards. I can even remember the most spectacularly smelly ones, like the reeking mess of my hotel toilet in Wadi Moussa, Jordan, where I paid $1.60 per night for a room, or the delightful filth of the Fatah headquarters in Nablus.

According to Virginia Heffernan, The New York Times television and “media” columnist, the sensuous depth of my experiences with Palestinian toilets is worthless. Every time I crap, I ought to be doing it in a replica of the Tokyo hotels which spray your backside with hand cleansing soap solutions, whether you like it or not.

How did Heffernan get into my toilet habits? Well, she didn’t. Actually she told me that the scent of books not only doesn’t matter but is a subject she finds tedious. The “aria of hypersensual book love is not my favorite performance,” she writes this week. “I sometimes suspect that those who gush about book odor might not like to read. If they did, why would they waste so much time inhaling?”

So if you like food, do you have to choose one sense as the limit of your experience? If you're invited out to eat with Heffernan: Don’t look at the plate and don’t savor the aroma; just eat the bloody thing.

The lady ought to get out more and think about her own senses. Most people only seem to notice smell when it makes them wrinkle their nose in disgust.

Whenever I’m in a Palestinian town, I can hardly breathe for all the sniffing I do. Strong cigarettes, body sweat, dust that seems superheated, donkey dung, cardamom from the coffee vendor and other spices in sacks outside a shop. The connection between scent and memory is in fact much stronger than the link between sight and our memories.

So forgive me if I go home from the Palestinian john and give my library the same attention.

I should add that Heffernan’s weird article posits the arguments of the great philosopher Walter Benjamin in favor of the love of a library, its scents and sense of touch. She then puts forward her argument in favor of e-readers which is that… Well, as far as I can see it’s just that she thinks Benjamin would probably have liked the Kindle, even though all the things he says he likes about books in his essay on collecting books don’t conform to the Kindle experience (except for the actual words you read).

It’d be like me writing that my old college tutor Terry Eagleton (author of “Walter Benjamin, or Toward a Revolutionary Criticism” 1981) wanted to elucidate a way for socialist literary critics to utilize new French deconstructionist techniques (true), only to add that he’d probably think Heffernan was a tasty bit of crumpet (probably true, knowing Terry, but no more than a hunch on my part.)

I’m not against the Kindle or other e-readers. I think it’s quite possible that many people will read more because of the ease with which they can download a range of works onto their little screens. One of my good friends here in Jerusalem loves his Kindle and has noted that, while I have to wait weeks for my books to be delivered, he can be reading whatever he wants in the seconds it takes to download a digital file.

My pal also points out that e-readers might be good for authors in the end (despite the fears of publishers) because he can’t lend my books once they’re bought on his Kindle. He has to buy another copy as a gift. See, I’m all for that.

Heffernan’s argument falls in line with the thoughtless cool accorded often-useless gadgets by people who haven’t looked beyond the sleek design and beeping sounds. (By this I mean the following conversation which I’m sure you’ve all experienced: “It’s cool.” “Why?” “It’s just cool, man.”)

Heffernan bloviates about scrolling through her “odorless dustless Kindle library,” comparing that with a dusty, odoriferous real library. But when she’s scrolling, she oughtn’t to compare herself to people who love books. The best comparison is to people who love card catalogues, because she isn’t looking at the books, only at their titles and some other referents.

“I have literally no memory of opting to get any of these books on Amazon,” she writes as she breezes down the list of contents on her snazzy device. That, Virginia dear, is because though it’s called a “Kindle,” you’re reading a computer. When I look at my computer, I often can’t remember when I wrote any number of blog posts or news stories based on a perusal of their file names. A few words in a digital list are nothing more than that. They have no design, no sensual triggers, no other association at all.

But I remember where and when I bought almost every book I own. (I also have a special place in my heart for the ones I stole as a teenager, but it turns out that might be easier to do with digital devices as well. Another thrill of youth lost to new technology.)

“The Kindle delivers a new kind of bliss,” Heffernan concludes. I’m sure it does, though Heffernan can’t tell us what that bliss might be.

Meantime, don’t forget about books. And, in spite of what I wrote above, don’t forget to flush.

(I posted this on a blog I write with three other international crime authors. Check it out. For more of my own blog post, visit my blog: The Man of Twists and Turns.)

Published on March 11, 2010 06:17

•

Tags:

amazon-kindle, arab, crime-fiction, fatah, gaza, jerusalem, jordan, kebab, media, middle-east, nablus, palestine, palestinian, squatting-toilet, television, terry-eagleton, the-new-york-times, toilet, tokyo, virginia-heffernan, wadi-moussa, walter-benjamin, west-bank

March 7, 2010

Literary reviews: If you can’t say something nice…

That’s not because of any insecurity about my writing. If a review is bad, I know the reviewer got it wrong. It’s the mere existence of negative thoughts about me and my work floating around out there, even if it’s only an aside in an otherwise positive review – that’s what makes my lunchtime hummus taste like cement.

It’s a feeling highlighted by the gratitude of a good review and the sheer love felt for the writer of a really glowing review. Right now, for example, I’m quite in love with Joe Hartlaub, reviewer for Bookreporter.com. A couple of days ago, Joe published a review of THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, my latest Palestinian crime novel. He wrote:

“Matt Beynon Rees, a Welsh journalist living in Jerusalem, writes a series known as the Omar Yussef Mysteries. If you pick up anything at all that is bound between two covers, you should be buying and reading them even if you hate mysteries. If you happen to like mysteries, please read THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, the latest Yussef novel, and recommend it to an unenlightened friend.”

You’re very kind, good sir. But wait, Joe goes on:

“Take a look at the first four pages or so. The book begins with Yussef, newly arrived in the United States, climbing the stairs of the Fourth Avenue subway exit in Brooklyn in the heart of Little Palestine. Much is familiar, and much is different. I may have read better written passages recently, but I don’t think I have read any that I have loved as much as the ones contained in these opening pages. This is classic work that will stand up 20 or 30 years from now when you (maybe) and I (almost certainly) are gone, and the problems that currently exist will still remain. Brilliantly conceived and beautifully written, THE FOURTH ASSASSIN is strongly recommended.”

Thirty years? Joe, may you live to 120.

My delight in this review isn’t the same as kick my two-year-old gets when I tell him he’s the most handsome boy in the world. No, it’s rather that someone has chosen to do exactly what I try so hard to do day by day – to be positive.

And being positive about a book seems strangely hard for people to do.

Many reviews, positive ones in particular, measure out the encouraging phrases as if they were sugar to a diabetic.

Truly negative reviews, of which I’ve only really had one, seem entirely a reflection of an almost psychopathic need to be both right and a little cruel at the same time. (That’s why Alain de Botton famously fumed when he received such a review for his book a year ago. Someone was being a smartass at his expense, and in a forum where he felt he had no comeback. Like being sassed by a cool kid at school when you’re unable to talk back.) There’s also a degree of showing off in a negative review which always makes them deeply suspect, in my opinion – was this a bad book, or simply something about which our reviewer needs to show himself to be the most knowledgeable fellow in the world?

Few writers these days claim to never read reviews. But it’s a dangerous pastime, particularly with the plethora of blogs and even reader reviews on amazon.com. Reviews on amazon are mostly conscientious, but every book seems to have at least one review on that site which begins “I couldn’t get past the first chapter, don’t know why, maybe it was just me, but I gave the whole book only one star anyway.”

A couple of years ago I decided never to write a negative review. I was sure that in a karmic way it’d come back to haunt me. I expressed this view to a literary editor who had sent me a true stinker for review. He twisted my arm; I wrote the review; something mildly unpleasant happened soon after. I know why. It won’t happen again.

Published on March 07, 2010 07:16

•

Tags:

alain-de-botton, amazon-com, blogs, bookreporter-com, brooklyn, crime-fiction, jerusalem, joe-hartlaub, kingsley-amis, literary-reviews, little-palestine, matt-beynon-rees, mysteries, mystery-fiction, omar-yussef, reviews, the-fourth-assassin, united-states, wales

March 6, 2010

The elusive, graceful future of journalism: Nina Burleigh's Writing Life

An NPR foreign correspondent friend used to like to run down a list of seven ways for journalists to grow old gracefully. His premise, which is self-evident to anyone who’s been a reporter, was that daily news was an undignified thing to be doing in your 40s. I can’t remember the whole of the list. It included writing op-eds for your newspaper (which seemed more or less like retirement), teaching journalism at a university (also retirement, but somewhat scorned by other hacks), and maybe the seventh was dieing. Undoubtedly the most prestigious way to proceed, according to that list, was to write nonfiction books. Nina Burleigh has a most graceful career, indeed. A former correspondent for Time and People, she’s written a number of historical nonfiction books, the most recent of which is “Unholy Business: A True Tale of Faith, Greed and Forgery in the Holy Land.” That book focused on a series of biblical archeological finds which the Israeli Antiquities Authority says are fakes and the dealers and archeologists currently on trial for allegedly faking such objects as the burial ossuary of Jesus’s brother James. Sort of “The Da Vinci Code” with subordinate clauses. Since completing “Unholy Business,” Nina’s been working on a book to be published next year about the controversial trial of American Amanda Knox for the ritual murder of a British student with her Italian boyfriend. Pretty gruesome and, when Nina and I chatted about it on my recent New York trip, it also turns out to involve some sinister figures tracking the author. But it also necessitated her taking her family to live in Perugia, Umbria, for most of last year. As I said, it’s the graceful way for a journalist to go. Here’s how she does it:

An NPR foreign correspondent friend used to like to run down a list of seven ways for journalists to grow old gracefully. His premise, which is self-evident to anyone who’s been a reporter, was that daily news was an undignified thing to be doing in your 40s. I can’t remember the whole of the list. It included writing op-eds for your newspaper (which seemed more or less like retirement), teaching journalism at a university (also retirement, but somewhat scorned by other hacks), and maybe the seventh was dieing. Undoubtedly the most prestigious way to proceed, according to that list, was to write nonfiction books. Nina Burleigh has a most graceful career, indeed. A former correspondent for Time and People, she’s written a number of historical nonfiction books, the most recent of which is “Unholy Business: A True Tale of Faith, Greed and Forgery in the Holy Land.” That book focused on a series of biblical archeological finds which the Israeli Antiquities Authority says are fakes and the dealers and archeologists currently on trial for allegedly faking such objects as the burial ossuary of Jesus’s brother James. Sort of “The Da Vinci Code” with subordinate clauses. Since completing “Unholy Business,” Nina’s been working on a book to be published next year about the controversial trial of American Amanda Knox for the ritual murder of a British student with her Italian boyfriend. Pretty gruesome and, when Nina and I chatted about it on my recent New York trip, it also turns out to involve some sinister figures tracking the author. But it also necessitated her taking her family to live in Perugia, Umbria, for most of last year. As I said, it’s the graceful way for a journalist to go. Here’s how she does it:How long did it take you to get published?

First published in sixth grade, I think. A local library in Elgin, Illinois. First paid publishing in journalism, at the AP in Springfield, Illinois. First book published, 1997. I don’t want to say how old I was then, but it happened because my agent was trawling the DC press corps for clients and found me. I had written a novel or two and never got anywhere with them (still haven’t sold any fiction).

Would you recommend any books on writing?

I like Strunk and White “Elements of Style.” And a Roget’s Thesaurus. I prefer my old paperback one, although the one on the web works okay.

What’s a typical writing day?

If I’m in the groove, I get up in the morning, fiddle around on the internet until I feel totally guilty, then quit it and don’t go back on for at least 3 or 4 hours, during which time I am supposedly writing, but may in fact be re-reading, in which case it’s not such a great day. After that, I usually have lunch or kids or other distractions.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

“Unholy Business.” Thrilling, hilarious and fun. Best book I ever put together. I am so depressed that it didn’t sell and that Collins never made a paperback of it. It’s fast and entertaining. But, the next book about Amanda Knox will be even better and maybe people care more about youth, sex drugs and Italy than fake archaeological objects and the Bible they purport to prove.

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

Pretty much, c, if you are talking about structure. In terms of method … probably b.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

Ridiculous question, Matt. I can’t remember the name of the author or book, though.

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

Hmm. In ALL of literature? I can’t remember. I do like a lot of the description in “The Leopard”, which I read in preparation for working in Italy. The author brilliantly, deliciously evokes 19th century Sicily, a place and time I had never given much thought to.

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

I don’t know. There are a lot of smart writers out there. I kind of admire Chris Buckley’s novels about American politics.

Who’s the greatest plotter currently writing?

I wish I knew. I would copy it.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

Too much. I really don’t want to work this hard.

Do you have a pain from childhood that compels you to write? If not, what does?

Yes, and it exists today. Nobody pays attention to me when I speak.

What’s the best idea for marketing a book you can do yourself?

I’ve heard that John Berendt claims you must do 4 things for your book every day for a year in order to get a best-seller. It worked for him, obviously. But I ran out of “things” after a few weeks the last time I tried.

What’s your experience with being translated?

I love looking at my book in Japanese. I have no idea where my name is on it, it could say anything.

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before could make a living at it?

I do live off my writing, but not off my books alone.

How many books did you write before you were published?

I think there was one novel in a drawer. It remains there.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

An autistic-seeming guy at the Jewish book festival in San Francisco followed me all around for an hour and none of the organizers stepped in, I had to hide. And then, I am among the chosen who have had the humiliating experience of speaking at bookstores where only the employees are present.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

I really want to write the amazing life story of my dog, picked up in a gutter in Mexico, now splitting his time between an apartment in Manhattan and house in upstate New York, after a half year frolicking in the olive groves of Umbria. I want to go into his brain and write about the world from his point of view. I think he must have a rather happy outlook. I don’t think this is any less likely to get published than my other ideas, though.

Published on March 06, 2010 04:35

•

Tags:

amanda-knox, archeology, biblical-archeology, christopher-buckley, da-vinci-code, dan-brown, elements-of-style, elgin, faith, forgery, giuseppe-di-lampedusa, history, holy-land, illinois, interviews, israel, italy, john-berendt, journalism, manhattan, mexico, nina-burleigh, nonfiction, people, perugia, ritual-murder, sicily, springfield, strunk-and-white, the-leopard, the-writing-life, time, unholy-business, writers