Sarah Hepola's Blog

February 27, 2024

Meet your new Dallas Morning News Staff Writer

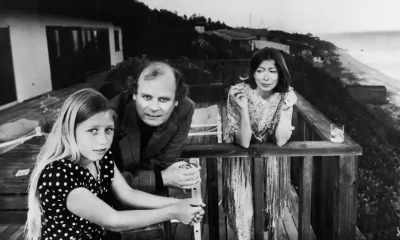

Dallas girl, circa 1979.

Growing up, I never wrote about Dallas. In the bedroom where I felt closest to happy, I scribbled stories on college-ruled notebook paper about a precocious girl in Maine (like Stephen King) or a troubled teen in Los Angeles (like the actresses I hoped to resemble) or a sophisticated woman in New York who probably did drugs (like everyone interesting).

I understood Dallas as the place I launched from, not the place I wrote about. I had imaginary interviews with Rolling Stone and People Magazine where I patiently explained how I’d fled Dallas as soon as I could, because that’s what plucky protagonists did in the movies. A young innocent must forge into the unknown to discover the larger world beyond (let’s say) NorthPark Mall and Pancho’s Mexican Buffet.

Eventually I would come to understand this as the “hero’s journey,” a term coined by Joseph Campbell and made legendary by George Lucas, who used the narrative structure to craft Star Wars, where Luke Skywalker ditched the sand-blasted terrain of Tatooine for those galaxies far far away. I would be next.

Theater dork, 1991, right there in the middle.

I wonder if part of my resistance to seeing Dallas as a place for writers is that, well, I didn’t know any. My friends’ fathers were real-estate developers and lawyers and real-estate developers (our town has a lot), while my own dad worked for the EPA. My mother was a social worker, and other working moms designed interiors and sold houses, though our section of Dallas was quite traditional, and most mothers stayed home, drove carpool, joined the Junior League. The single mother next door wrote a society column for the Dallas Morning News, and her closets filled with designer dresses and high heels (sorry, I snooped) for the galas and charity balls that were the year’s big events. I didn’t care about society. Or, to be more accurate: I didn’t care about that society.

I went to college in Austin, where the most famous writers were musicians, though I couldn’t help thinking half of them sounded like Stevie Ray Vaughn. I came back to Dallas in my late 20s, and I wrote about local music, and the bands I covered seemed to be suffering from chronic low self-esteem, though it’s possible I was projecting. Dallas was not Austin, a city with the chutzpah to name itself the Live Music Capital of the World, and Dallas was not Houston, a place so unique it gave rise to Beyonce. Dallas gave rise to Jessica Simpson and Pantera, but the musicians I loved were in the Wilco vein. I drank too much in smoky bars, sang along to broken-heart ballads, and if that sounds like I was more fan than critic, I probably was. The Old 97s wrote brilliant songs about Dallas, but by the time I got back to town, half of them had moved away. The best of the upstarts struck me as worthy of a national audience: Carter Albrecht (RIP), Trey Johnson (RIP), John Dufilho (thank you for sticking around). But I figured anyone who wanted to matter would have to push off their barstool and leave Dallas — so I did.

2022. Old 97s, thank you for your service.

I spent six years in New York, four more than I’d promised myself. I wrote for big publications, though I’d been doing that in Dallas, too, where rent was much cheaper. But I got to mingle and hob-knob with writers whose names I recognized from book covers and bylines — my kind of society — and though I learned a lot, one lesson I’ve neglected to mention is how it gave me an appreciation for writers back home. I didn’t see that much difference between the high-profile names I edited at Salon and the colleagues I’d joked around with at the Dallas paper. Well, I did see one difference: The high-profile names lived in New York. (Or Los Angeles, or San Francisco, or Chicago, though that was pretty much it.)

In 2011, I returned to Dallas once more, though I promised myself it was temporary. The whole point had been to launch from this place, not come back with my tail between my legs. I was 36, newly sober, lost in the world. I kept talking about moving, but I kept staying in place, though I began to see that Dallas was a town worth writing about after all. I penned a column about the city’s beauty culture for D Magazine called “The Smart Blonde.” I wrote an essay about finally learning to shoot a gun for the Dallas Morning News.

That essay had the same thrust of nearly every essay I would write about Dallas: An outsider who once rejected hometown rituals had become a woman curious what she’d missed along the way. I was trying to find peace — with myself, with my childhood, with the city I did not leave after all, because cheap rent is essential to a creative life, one reason the coastal writers have to hustle so hard or gain access to trust funds and rich spouses. In 2015, my book came out, and I gave phone interviews to journalists who sometimes asked about living in Austin. But I didn’t live in Austin, I explained. I lived in Dallas, and in the awkward silence that followed I filled in the obvious follow-up: But why?

2015, “Blackout” event at Dallas’ Barnes & Noble.

Austin had become the artistic hub, the approved city, assumed home to Texas’ creative class. Richard Linklater, Lawrence Wright, Elizabeth McCracken, Ernest Cline. Dallas did have writers, excellent ones. Ben Fountain was a national book award finalist for Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, an epic that took place at a Dallas Cowboys game. Skip Hollandsworth is the father (or at least benevolent uncle) of Texas true-crime, with an archive that brought us Bernie, the soon-to-be-a-hit Hit Man, and more episodes of My Favorite Murder than I’d care to count. But I wouldn’t be surprised if those two got asked about living in Austin. Why didn’t they live there? As if a creative life would be best-served by caving to stereotype.

I love Austin. I visit often and spend half the time wondering why I don’t live there and the other half wondering what happened to the slacker valhalla that used to feel like home. But my best stories over the past decade came to me because I lived here, not there: A podcast on the Dallas Cowboys cheerleaders, the profile of a woman who lost both children in a fire set by her ex, an essay about real-life cowgirls that told the story of a woman named Mama Sugar who worked the land as a girl, rode a homemade wagon with a mule out front like other kids ride a bike. That last one was nominated for a national magazine award, the kind of brag I desperately wanted in my New York years, but it wasn’t until I left New York, came back, that I got it.

2022. Me and Mama Sugar.

“A hero’s journey” is about launching outward, but it’s also about circling back. People talk less about that part: The return. The path is not an arrow but a circle; you trace your orbit of derring-do till you land in the place where you started with more wisdom, more bruises and, if you’re like me, more credit card debt. But it strikes me as nuts that I once considered Dallas a place you don’t write about. Do you realize who lives in Dallas? Mark Cuban, George W. Bush, Jerry Freaking Jones.

Dallas may not be a literary capital (though props to Will Evans and many others working to make it competitive), but we have the best characters. Stormy Daniels, Harlan Crow, Glen Beck. We have Luka and Dak, sure, but also a trail of Hall of Famers I’ve run into at the gym, back when I could afford a membership: Troy Aikman, Emmitt Smith, Dirk Nowitzski, Michael Irvin. Roger Staubach is kicking around somewhere (real-estate developer). But it’s not just sports. Erykah Badu lives here, God bless her. Robert Jeffress and TD Jakes broadcast to massive audiences from their Dallas megachurches. Conservative firebrand Stephen Crowder lives here, even if the 5.7 million subscribers to his YouTube channel probably don’t know it. I haven’t even mentioned the galas and charity balls where the billionaires (yes, plural) mix and mingle and likely swap funny anecdotes about private jets in line for the bathroom. From a writer’s perspective? What we have here is a land grab.

Darrell “Moose” Johnston, at the 2022 launch of EIGHT beer from Troy Aikman, who told me that night he’d put out a non-alcoholic version. Don’t make me call you a liar, Troy.

2024 is not a peak time for local papers. Pretty much any year this century has not been glorious for the beat reporters and city columnists and art mavens whose role, once upon a time, was to take the pulse of a city, unless that city happened to be New York and that paper happened to be the New York Times. But 2024 has been particularly brutal. The Los Angeles Times, once thick enough to double as a doorstep, has become a slip of thing, shedding 115 journalists in one blood-letting. The Baltimore Sun, once-home to Wire scribe David Simon and legendary satirist HL Mencken, changed hands and cut salaries, leaving its future in question. An average of five local newspapers close every two weeks, according to the New York Times, a statistic that sounds unreasonably high to me, though the drumbeat of doom has gotten so loud that people seem surprised to discover they even have a local paper, like learning that Radio Shack is still in business.

Dallas has a local paper. It used to have two, back in the go-go days of the 80s Newspaper Wars, but the Times Herald folded in 1991, and the Dallas Morning News thrived, going on to win a Pulitzer in 1992 (investigative reporting), 1993 (spot news photography), and 1994 (explanatory journalism). Not bad. The last 20 years brought fewer Pulitzers, more cutbacks, the shuttering of satellite offices, an experiment in cool-young news called Quick that could never punch as hard or as fast as the Internet, which was clobbering all print competition. This is not a local story, it’s a national one, a financial kneecapping that has cratered even the digital upstarts that once posed the biggest threat. Vice, Pitchfork, Jezebel, BuzzFeed news, no more. The Internet gave us the news for free, but it cost us. Unclear, as of this moment, how much we’re willing to pay.

On Tuesday, February 27, I start a gig as a features staff writer for the Dallas Morning News. My beat, according to the job description, is “Dallas’ big personalities, its lively scenes, and the insider stories that get people talking.” No lack of material there. It’s been more than a decade since I’ve been on anyone’s payroll, even longer since I went to an office. I’m excited about the first part, worried about the second. I spend most mornings typing in bed next to the warm and purring cat, still wearing what I slept in. This is a distant planet from “business casual.”

2024. “Office space.”

One cool side note is that I still get to write the occasional piece for other publications. Texas Monthly and Texas Highways have been good to me in these lean-freelance years; I have no plans for exile. In fact, I have two stories in the pipeline at Texas Monthly, one past late deadline at Texas Highways (it’s coming, Mike), and I’ll keep doing my culture podcast with Nancy Rommelmann, Smoke ‘Em If You Got ‘Em, though I’m under strict employee guidelines not to talk about elections or horse-race politics, what a gift. No Trump or Biden rants? You got it, boss.

What I get is to be an explorer in my hometown. To launch into the strip malls and suburbs and the tony parts of Dallas and the neighborhoods where people park their trucks on the lawn, and I get to ask questions. I’m literally paid to do this. I hope to bring news of this world to the subscribers of the Dallas Morning News, because the paper has many, and though subscribing to anything — a newspaper, another Substack, Paramount — has become a modern irritant, the free lunch buffet of the aughts replaced by the annoying pay wall of credit card info and yet one more password to forget — I hope some folks who follow my work might join me. At the least, I hope you’ll watch from afar.

Maybe I can convince skeptics that Dallas is indeed a good place to write about. Maybe I can convince people in Dallas that learning about your city isn’t just a distraction from the clown car of national politics and culture-war divisions, it’s a salve. See, I’m convinced that part of what ails our country right now is the way we argue across state lines, flinging ugly stereotypes and drive-by insults at folks we will never run into at Pancho’s Mexican Buffet (still around, raise the flag). We invest so much rancor in a presidential election whose outcome we have almost zero influence over (at least in Texas) and meanwhile, who’s the mayor? Eric Johnson, by the way, and he’s having quite a month. The over-investment in Washington narratives, the lack of investment in local ones: It’s a problem. I know this, because it’s a problem for me.

One of the great adages of literature is “write what you know.” One of the great adages of journalism is “Ask questions.” I plan to do both.

In summary: Mark Cuban, let’s talk.

2012. Klyde Warren Park.

The post Meet your new Dallas Morning News Staff Writer appeared first on Sarah Hepola.

January 1, 2022

The Impossible Year

I had a hard year. A lot of people had it harder, a fact I reminded myself of constantly. I never got Covid. Nobody in my family got Covid. I had a solid roof, a warm bed, a loyal and outrageously handsome cat, and a series of microwaveable Amy’s frozen dinners that people in other parts of the world might find very luxurious. And yet, the year was hard, and knowing how much worse other people had it never made it better. It made me feel guilty, actually, because here I was — not sick, not forced to home-school my kids while juggling a demanding job, not tirelessly slogging through the bleak corridors of a hospital to tend to one more doomed patient, not even forced to roll the corn tortillas filled with sprinkled cheddar to enjoy a delicious cheese enchilada — and everything still sucked.

“I think I’m having a meltdown,” I told friends during the worst stretch, from August to late October.

“A lot of people are struggling,” they often said, and it was meant to be grounding. It was meant to remind me I was not alone. One more wounded soldier in the vast limping army. But I would start doubling back, embarrassed not to have earned my place. (“I know I’m fortunate,” etc. etc. ) Then my friends would start scrambling to validate my particular suffering. (“Everyone’s challenges are unique,” etc. etc.) And we’d fall into this gentle tug of war that made me sadder, so I didn’t talk to people much. I flaked on lunch dates. I deleted my dating apps. I disappeared from social media.

People only wanted to help. I only wanted to be helped. But such was the poignant disconnect where I found myself stranded in the fall of 2021. It was easier to be alone.

Wallace, a loyal and outrageously handsome cat.

The problem was work. The problem was that I couldn’t sleep, and I woke in the dark hours with an anxiety so full-throated my body was trembling, and it didn’t stop trembling as I trudged from station to station through the afternoon. The problem was that I could spend an entire day writing two sentences, and I know that sounds like an exaggeration, so let me assure you it was not. One day, two sentences. I hadn’t experienced this kind of writer’s block (or whatever you call this) since my mid-twenties, when I’d pace and smoke, trying to shake loose a few strong verbs. Back then, I drank to quiet the anxiety. Now, I was more than ten years sober, and I refused to drink — but what could I do?

People told me it was hormones. People told me it was depression. People told me it was a painful but necessary transition phase — but from what to what? I tried supplements. I tried exercise, until I stopped exercising. I was flat broke by this point, and the specialists and spa trips and vacations that might have helped at another time were out of reach for me. (Also, there was a pandemic.) I borrowed money from my parents. I borrowed money from my brother. I borrowed money from a good friend. Not for indulgences; for rent. I borrowed money the way I used to buy booze, a little bit from a few places so no one one would know how bad things had gotten. I started smoking again. I paid for the cigarettes with a gift card from American Express I found lying around. It was stupid, and I didn’t care.

One low afternoon, I collapsed in the padded chair of a twelve-step meeting and sobbed during my five-minute share. Afterward, a gray-haired woman with a maternal figure took me to dinner, and she told me to pray (thanks), and she handed me a pamphlet like a goddamn newcomer, and I felt a seizing despair that this stranger was spending so much time with me, and I only wanted to flee.

“Would you like a Buddha?” she asked as we parted, pulling out a chubby golden trinket from her purse.

“Yes,” I said, and I rubbed his round belly with my thumb, and I placed the goofy Buddha figurine by my bedside table, and actually, the Buddha helped. I smiled whenever I saw it.

But I was worried I would not make it through this wicked passage. I stopped writing in my journal. I stopped reading books, and then I stopped reading the news. I couldn’t watch Netflix. I didn’t even listen to music. It was a very boring time. I mostly stared and paced. I was starting to retract from job offers, panel offers, I tried to get out of the work I’d already taken on, and if I did this, if I actually quit writing as I fantasized about daily, I had no backup plan, no way to pay my bills, which was equally harrowing. One day I applied to be a Door Dash delivery person. It seemed like a gig I could manage. Almost immediately I got an email that there was a waiting list.

I met my friend Mary in sixth grade. People often mistake us for sisters, and maybe that’s not a mistake.

And so, I did what all of us do when faced with the impossible — I soldiered on. Weekends were particularly rough, because even though I dreaded the Zoom meetings and the knock-knock-swoosh of the Slack channel, those obligations anchored me. The weekends left me drifting in the poison waters of my own worst-case scenarios. My friend Sharon, who knew this about me, made a point to see me each weekend, even though she was a busy columnist. We sat across from each other at burger joints and a Mediterranean restaurant (she picked up the bill), and she helped me strategize the upcoming week. My friend Mary, who also knew this about me, made a point to show up to my place on Saturday mornings, even though she was busy helping her mother move into a retirement home. We took long walks on the tree-lined streets, both of us wearing hoodies, the same height, the same size and coloring and blonde hair, looking like sisters, and sometimes I cried when we got to the part where I was supposed to talk.

“I have total confidence you’re going to get through this,” she told me.

“But what if I don’t?” I asked.

“Then borrow my confidence,” she said, and I squeezed her hand.

These stories make my eyes water, not because they make me feel sad, but because they make me feel lucky. I have always wanted a partner. I have always wanted a husband and kids and the kind of connected domestic life that seemed a birthright to a little girl growing up in the Eighties, and I didn’t have any of those things, which also amplified the sorrow (and relief, depending on the day). But I had these women. Some of my friends are guys, and they helped too, but really? This year? It was the women who saved me.

My friend Jamie, who called on her long walks. My friend Julie, who called on her long drives. Those two know me better than most living humans, and I never had to pretend with them, which was a gift. My friend Sunny, my friend Andrea, my friend Amy, who also happens to be my agent. The legacies: Lisa, Stephanie, Tara, whom circumstance kept far away this year though they still felt close. Victoria, Pia, Carey, Eleanor, Amanda, Tracy, Deborah, Allison, Kim, Nicole, the other Amy, I’m fortunate to have so many friends, I’m certain I’m forgetting someone (and I apologize). But I could not find my way out of this hole.

Austin, TX, 1992. Julie and I were taking selfies before that became a word, back when you had to walk a mile in the snow just to turn a Canon camera toward your face.

One Sunday, as I sat chain-smoking on a couch I’d placed in an outdoor corridor, staring at two fold-out chairs I never used, I texted my friend Pam. “I think I’m having a meltdown. Can you talk?” She could, even though if memory holds, her son was having his birthday party in the other room. I told Pam I wanted to quit. Everything. The creative life I had fought for all my life was proving too much; I was overmatched. Pam is one of those wildly successful journalists who struggles more than outsiders might imagine, and I knew she’d understand. She listened. She shared her thoughts. “I don’t think I’m helping,” she said, but she was. Maybe she meant she couldn’t fix it. But only I could do that.

It’s very scary to have built your life around work, and then watch the work crumble. I wouldn’t recommend this route. I needed a hobby. I needed a purpose. I needed something.

The next weekend, I went to visit my friend Jennifer, who had moved to a ranch near Corsicana, an hour south of Dallas. I sat on her porch staring out at the big tree with its strong, low-swooping branches and the dogs curled on the grass, and I felt something closer to calm. Jennifer and I became friends in eighth grade, two bookish middle-class kids in a rich neighborhood, but she’d made her own sizable income as a veterinarian who co-owned three successful clinics. When I told her I dreamed of quitting but had no idea how to pay my bills, how to survive, she said that was OK, she’d support me. Jennifer has two teenagers, four horses, a handful of goats and donkeys and fat waddling hogs, but she would make space for me. We scoped out the one-room lake-house near the water that she was currently renovating, and we wondered aloud if my cat would fit.

Jennifer and I in a photo booth in ninth grade (top), and Jennifer and I at a fancy hotel on Christmas Eve, 2017.

But I did not move into Jennifer’s place. I did not quit, at least not for long. I got on Zoloft, which is a thing I very much did not want to do, and I did it anyway. I told my colleagues that I needed their help, and they happily gave it to me. The Zoloft was slow to kick in, and for a month I couldn’t tell the difference, but one week I read Jonathan Franzen’s Crossroads in three sittings, which was like slipping underneath the soft weighted blanket of someone else’s struggles, and the next week I listened to the audiobook of My Dark Vanessa (also recommend) as I walked around White Rock Lake, and I could feel the clouds starting to part. This was good. I liked reading again.

I can’t pinpoint the day things got better. It was like recovering from heartbreak, or a nagging cough, everything was miserable and then slowly, almost imperceptibly, I felt released. I wasn’t trembling anymore. I was cracking jokes on my Zoom calls, I was smiling even when I didn’t have to be. I was making deadlines, going to movies, posting pictures of my cat on Instagram. The work I was convinced would be too much for me stopped feeling daunting and started feeling invigorating. One morning, I woke up in the dark hours, opened my laptop, and a thousand-word essay popped out.

And so I end 2021 in a much better place than where I spent much of it, which might be all you can ask. I am grateful for my friends, grateful for my work, grateful for the pharmaceutical intervention I really did not want, but that’s the story with life sometimes, you need things you don’t want, and you want things you don’t need. I am too allergic to sunny optimism to believe the next year will be better simply because it is next, but I know this.

You can always make a new start.

This is a picture of a donkey eating my car at Jennifer’s ranch. May we all find comfort and companionship in 2022. We’re in this together.

The post The Impossible Year appeared first on Sarah Hepola.

December 25, 2021

Things Fall Apart: Thoughts on Joan Didion

My college boyfriend introduced me to Joan Didion. He gave me his dog-eared paperback of Slouching Toward Bethlehem. I remember turning to the picture of Joan on the back, young and pretty and serious. I remember the poetic allusion of the title that was lost on me, because I never read poetry.

“I really think you’ll like her,” he said, and I nodded.

I’d wanted to be a writer since I was eleven. Maybe earlier, but definitely eleven. That’s the year I won a writing contest, and the teachers and the kids swooned in a way that was nearly dangerous, because it instilled a blazing entitlement. Of course I won the English award in eighth grade. Of course I got A’s on my essays in high school English, even though I never read the books, which I considered boring. I was obsessed with Stephen King, and Edgar Allan Poe, and William Faulkner, whose twisted Gothics made me weirdly horny even as they barely made sense.

By the time I got to college, and found myself at long discussion tables with other precociously talented students, I was starting to realize this approach had been a mistake. My friends talked about authors I did not know: Tom Robbins and Franz Kafka and Hunter S. Thompson. Loving Stephen King was such a cliche, painfully middle-brow, and I badly wanted to up my game, but I found the introduction to this new female writer kind of threatening. Was she better than me? Did my boyfriend like her more? Was he sorry he wasn’t dating Joan Didion?

That guy was a wanderer. A chef, who carried knives in his car, and rolled his own cigarettes, and liked going on road trips and stopping at dives where the sad women with coffee pots wore too much blue eyeshadow. I never felt cool enough for him. Once I found a picture of his friend Patricia in his wallet. That was weird. She lived in New York City, a place I’d never been. “I really think you’d like her,” he told me, even after I found her cotton panties in his closet, but I didn’t think I’d like Patricia, and I didn’t think I’d like Joan Didion.

“Thanks,” I told him, placing Slouching Toward Bethlehem on my bookshelf with zero intention to read it.

I was 25 when I first opened that book. I was working at an alt-weekly newspaper in Austin, surrounded by more people whose vast knowledge of art and music intimidated me, and I was trying to finish a big story I badly wanted to write and now badly wanted to quit. It was always this way with me: If I didn’t get the splashy assignment, I’d fume with envy, but if I did get it, I’d become crippled by self-doubt. I’d spent a long weekend staring at a blinking cursor, pushing around two sentences like lima beans on a plate, pacing the backyard as I chain-smoked Camel Lights, or Marlboro Lights, or whatever I was smoking back then. Writing, which had once been exceedingly easy, had become more like running in tar.

I don’t know why I picked up Slouching Toward Bethlehem. Maybe someone mentioned Joan Didion. Maybe nobody had. But I opened to the preface, and this is the part that struck me:

I am not sure what more I could tell you about these pieces. I could tell you that I liked doing some of them more than others, but that all of them were hard for me to do, and took more time than perhaps they were worth; that there is always a point in the writing of a piece when I sit in a room literally papered with false starts and cannot put one word after another and imagine that I have suffered a small stroke, leaving me apparently undamaged but aphasic.

It was starting to sink in that writing was a thing I’d have to work for. It would require me to read everything, even books I did not like, it would require me to sulk and fret and tremble with fear not because writing was hard (though it could be), but because writing mattered. I had to fight for it.

But I’d never seen a writer describe my own particular agony with such a direct hit. I felt the same way I had when that swaggering college boyfriend first drizzled his fingers down my bare back with a stroke so masterful that all I could think was: Yes. Yessss.

I guess falling for a writer isn’t so different than falling for a guy, at least for me, except that guy bailed after six months, and that dog-eared Joan Didion book — well, it’s sitting face-down on my chest I as type this.

I moved to New York City, a place that Joan Didion had captured in her lasso. “It is often said that New York is a city only for the very rich and very poor. It is less often said that New York is also, at least for those of us who came there from somewhere else, a city for only the very young. “

I was 31 years old when I found my first place in Brooklyn, an age that strikes me as dewy with innocence now, but I did feel old among the visual arts students and trust funders of South Williamsburg. But the city was filled with so many cool spots, and being inside them made me feel cool, too.

A dear and very connected friend used to get us reservations at a swank speakeasy in the theater district, with dim lighting and zebra-print chairs and $16 glasses of Malbec. One late night, while smearing brie onto a hunk of rustic bread, I looked over at a leather booth and saw Joan Didion. I recognized her immediately: The pageboy hair, the big sunglasses, a slump that was maybe more like frailty. She was seated next to a distinguished man I would learn was the director David Hare. They’d recently debuted the one-woman show of her memoir The Year of Magical Thinking on Broadway, and even though I was broke all the time, and even though I was homesick for Texas, I thought to myself: This is why I can’t leave New York.

I also thought, “Oh my God, she is TINY.”

Of course I did leave New York. I moved back to Dallas, a rather uncool place though it suited me, and over the past ten years, when people asked my favorite writers, I usually said Joan Didion. That had become a cliche, too. Joan Didion was a style icon, a literary legend, a figure of dignified suffering, who had lost her husband and daughter within the space of two years.

She never did write a classic novel, like so many of her peers. Play It As It Lays is icy and atmospheric, but I don’t remember much of it. Those essays, though. She made personal writing feel journalistic, and journalism feel personal. She made catastrophic events feel survivable, and ordinary events feel momentous. Feminist types liked to quote her in social media posts and stories, even though she hadn’t been so hot on feminism. (“The astral discontent with actual lives, actual men, the denial of the real generative possibilities of adult sexual life, somehow touches beyond words.”) But with her fierce economy of language, and her chic author’s photos, she was Instagram cool long before Instagram ever existed.

A male writer once challenged me. “Who’s your favorite female author? Don’t say Joan Didion.”

The pinwheel in my mind spun, as I cast about for a runner-up. “Janet Malcolm,” I said, and I did love Janet Malcolm, but it was like saying your favorite band was The Who because you didn’t want to say The Beatles. Leslie Jamison, Rachel Cusk, Cheryl Strayed, their words gave me the falling-in-love feeling, but Joan still felt like the original. The taproot.

In 2017, the Joan Didion documentary The Center Will Not Hold came on Netflix, and I watched it several nights in a row for weeks. I was having trouble sleeping, and I would wake up at 2am, and start the film in the dark, with its dazzling opening shot of the San Francisco bridge and those famous lines from Slouching Toward Bethlehem.

I went to San Francisco because I had not been able to work in some months, had been paralyzed by the conviction that writing was an irrelevant act, that the world as I had understood it no longer existed. … It was the first time I had dealt, directly and flatly, with the evidence of atomization. The proof that things fall apart.

But there was this one line I gnawed on for months. She was talking about her husband John Gregory Dunne, also a writer (though I’d never read him), and even though I knew very little of their life except the glimpses I got in her work and her photos, I thought of them as a model couple. Glamorous, brilliant. Partners.

“Falling in love was not in my vocabulary,” she said.

Could that be true? The woman with words at her fingertips said “falling in love” was not in her vocabulary, but in mine, it was a mainstay. I’d been chasing that feeling across so many decades, so many time zones, and I started to wonder (not for the first time) if I’d been doing it wrong.

Joan Didion was practical. She was unsentimental. I was deeply sentimental, terribly impractical. Maybe that’s why I needed her. Not just for the inspiration, but for the corrective.

Once, in a dry season, I gave a Joan Didion book to a man I loved. (Well, actually, it was a link to an essay, but that sentence sounds lame.) He fell for her instantly, as I knew he would.

“There will always be an asterisk next to her name that makes me think of you,” he told me, which made me proud and sad at once. Proud because being roped to Joan Didion was a writer’s dream, and sad because the sentence forecast a time when we would not be in each other’s lives, which proved to be prescient. Things fall apart. I have not spoken to him in years. I couldn’t tell you where he is, what he’s doing, who he loves. But it’s my girlish hope that when he read the news that Joan Didion died at 87, there was an asterisk next to her name that made him think of me.

Is that selfish? Only human? I remember one more line in the preface to Slouching Toward Bethlehem that struck me, one I have quoted over and over these many years.

“That is one last thing to remember: Writers are always selling somebody out.”

The post Things Fall Apart: Thoughts on Joan Didion appeared first on Sarah Hepola.

December 22, 2021

Cheerleaders, cheerleaders everywhere

I hope you get a chance to listen to my “America’s Girls” podcast, or at least rate it five stars, or at least tell a friend, or at least don’t confuse it with the American Girl doll, which would be disheartening.

Over on the Texas Monthly site, I’ve been writing “behind the pod” essays about the women I’ve gotten to know. Apparently a six-hour podcast wasn’t enough for yours truly. The podcast covers more than 50 years, with material drawn from more than 50 interviews, and I found myself wanting to tell smaller stories about people or moments that made an impact on me. Here’s what I’ve got so far. (These essays will continue rolling out through the end of the show’s run in mid-January.)

Meet the First Woman to Wear the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders Uniform: Vonciel Baker was a little girl from South Dallas, who grew up dancing in her living room and bedroom (and sometimes public parks), tried out for high school cheerleader three times but didn’t make it, and in 1972, stepped onto a rocket ship she didn’t know was launching.

Dancing With the Poster Girl of the Cowboys Cheerleaders’ Golden Era: Shannon Baker Werthmann was on posters, playing cards, Frisbees, calendars, and even her own doll. A trained ballet dancer, she elevated dance on the squad, first as the golden girl of its pop-culture late Seventies peak and then as the choreographer. She was unceremoniously fired in 1991 by current director Kelli Finglass, and talks about that for the first time, but what’s special about Shannon is actually everything.

The Cowboys Cheerleader with the Pigtails Shaves Her Head: Seventies cheerleader Tami Barber was “the girl with the pigtails,” but while pop culture remembers her as a cutie pie and a sweetheart (she is both), she was also a bit of a rebel.

In Search of the Cowboys Cheerleaders Who Posed for Playboy: In December 1978, five former Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders showed their breasts to the world. It was the “NFL Bares All” issue of Playboy, but an act intended to leverage money and fame exploded into scandal, shame, and personal repercussions that have lasted decades. Only one of them has ever spoken publicly about it, and I searched tirelessly to reach those women — but did they want to be found?

The post Cheerleaders, cheerleaders everywhere appeared first on Sarah Hepola.

November 28, 2021

Why I’m Doing a Podcast on the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders

I grew up watching women’s bodies. I think it started on movie screens, but it moved to television and locker rooms and swimming pools. I watched their suntanned shoulders in halter tops, I studied the parting waves of their tumbling hair, and I wondered if my body would ever have that kind of magic.

There was this poster I was obsessed with at the age of five. I stared at that image on bedroom walls and 7-11s, where Slurpees were medicine for the Texas heat. It was all these women in a blue and white uniform, but the one I couldn’t take my eyes off was the redhead on the right. She had the mane of a lioness, a look of fire — and I saw in her something like the woman I wanted to be.

This was 1979 in Dallas, Texas, where my bookish family had recently moved from Philadelphia. It was a year after a soapy drama called Dallas debuted on prime time, a year after an NFL highlight reel dubbed the Cowboys America’s Team. You could call this Peak Dallas.

In other towns, at other times, I might have grown up staring at royalty or beauty pageant queens. But in the blackland prairie of North Texas, in the late Seventies, I grew up watching the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders.

The Little Miss Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader pageant launched in 1979, with 10,000 entrants, including this cutie pie (from the Dallas Morning News)

I spent much of my young adulthood living outside Dallas. I let other climates erode my teen habits of shopping and beauty counters. I wore flip-flops and a gray hoodie to the office of a newspaper, my hair pulled back in a sloppy bun. But about ten years ago, I moved back, and things I’d never noticed before began to fluoresce.

I was standing in a parking lot off the roaring highway when I looked up and saw her on a billboard: That same blue and white uniform, hair like Venus on the half shell, one arm casually draped atop her head. A goddess floating above the lumpen masses so painfully earth-bound on Central Expressway.

Forty years had passed since I first fell in love with the cheerleaders. Empires had crumbled, industries had dissolved. How was it possible so much had changed — and the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders were still here?

This is not the billboard I saw, but it’s very similar.

Stories begin like this. You just — notice a thread, and keep tugging. What struck me in that moment is that I knew next to nothing about the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders. How they started. Who those women were, what their names or inner dramas might be. They were just bodies. Images to worship or ignore or disdain, and by the time I stood in that parking lot, I’d done all three.

And so I began tugging. I learned the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders had pioneered the spectacle of sexy sideline dancers. Huh, I didn’t know that. I watched their reality show “Making the Team” on the cable network CMT, expecting to be either annoyed or bored, and I found myself wiping tears when the squad was announced, and practicing my high kicks in my bedroom. The cheerleaders may have started as a way to attract a male audience, but the reality show had reshaped them to attract a female audience. Women like me love this stuff: The artistry of performance and competition and personal styling. I could not get over the marvel of their bodies — the arabesques, the jump splits, the way they danced with their hair, almost as though their hair were a fifth limb.

To be fixated on women’s bodies might sound pervy, but to me it only felt logical. I was a little girl who loved dance, but I’d spent an adulthood hunched over a laptop, locked in my human suit. I still saw in those women something I wanted to be.

In 2014, two cheerleaders with the Oakland Raiders filed a wage-theft law suit. Over the next years, law suits moved like a stadium wave across the NFL cheerleaders. Sexual harassment, verbal abuse, body shaming. In 2018, the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders got a fair-pay law suit of their own. It was filed by a three-year veteran named Erica Wilkins. She’s actually the cheerleader two photos up, who’d been featured on the cover of the swimsuit calendar. Even their golden girl turned against them.

I’d grown up in a media landscape where cheerleading was portrayed as a glossy fantasy, and I found myself in a media landscape where cheerleading was portrayed as a waking nightmare. “A Ponzi scheme in hot pants” according to Deadspin. “What fresh hell is going on with the NFL and its treatment of its cheerleaders?” asked Vogue. There were stories of humiliating “jiggle tests” and rule books lousy with double standards. The pay was terrible, even if hundreds (and sometimes thousands) of women were still lining up for it. Media responses moved in opposite directions: These women were elite performers who should be paid according to their value; and this was a silly, sexist tradition that needed to be shut down.

Squads began folding, going coed, becoming more modest. I could never get my hands around what to say about this. So much of journalism (so much of culture) felt like being shoved into the corner of pro or con. Are you for this, or against this? I didn’t know! What I knew is that I’d grown up wanting to find myself in the macho world of men’s sports, that female beauty and movement is one hell of a tractor beam, that I’d idolized those women once and it felt rather disloyal to turn on them now, and that the entire spectacle felt increasingly phony and outdated. And so my love was quite complicated, although when it comes to real love, an honest brokering — I’m not sure there is any other kind.

One day, about a year ago, I was tossing around ideas for various projects with my editor at Texas Monthly. I was slowly working through a revision of my second memoir, but I needed something completely different. He’s the one who came up with it.

“What about a podcast on the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders?”

This was once my closet, and that uniform is a knock-off I bought from an online depot in China, and those shorts are roughly the size of a hand towel.

I almost didn’t take on this project. Much of my work comes from personal experience, and I had no experience as a cheerleader or dancer, not even in high school. I was only a fan of the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders (when I was five!), but the more I learned, the more convinced I became that they were one of the great stories to come out of my hometown, and not enough of that story was known. I read Joe Nick Patoski’s epic history of the Dallas Cowboys (highly recommend), and I flipped through the 70-plus pages of source articles and books on the football team, and I saw exactly one book about the cheerleaders, Decade of Dreams, which was out of print.

Everyone had opinions on the cheerleaders — pro or con! idolize or disdain! hot or not! — but I wanted to tell the story of their evolution from a sideline experiment to a global phenomenon, moving from a culture very skeptical about the display of women’s bodies, through decades of rampant sexualization, and back to the beginning again, as a new skepticism takes hold. It’s a story about exploding taboos and also reinforcing traditional ideas at the same time. There is a terrific 2018 documentary about the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders called The Daughters of the Sexual Revolution. Directed by Dana Adam Shapiro (who also did Murderball), the movie is a rocket ride through the squad’s golden era, but my biggest gripe about that film is that I wanted it to be about six times longer.

And so, as the narrator says in her smoothest contralto, my journey began. It was a journey that would take me across the past 50 years of history — across changes in women’s lives, in media, in the city of Dallas and the country itself. It would take me to the rubble of Texas Stadium and the consumer coliseum of Cowboys stadium, aka JerryWorld, where the American flag is displayed above the logos for Pepsi and Miller Lite.

Left: The old site of Texas Stadium, longtime home of the Cowboys. Right: The enormous AT&T Stadium built by Jerry Jones, a cathedral to football and corporate sponsorship.

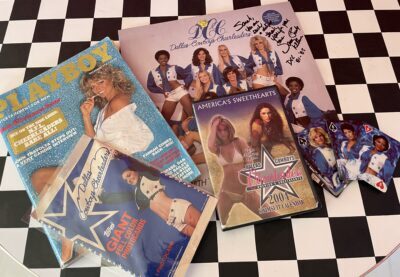

The journey would take me into cheerleaders’ homes, where memorabilia was often spread across a dining room table like a grand buffet. It would take me through lore about strippers, and scandals, and personal sacrifice. It would take me into YouTube rabbit holes and the deep oceans of eBay, where my purchases include: a 1981 deck of playing cards, a 1982 vinyl album of workout routines, a 2005 swimsuit calendar making-of DVD, and a 1978 Playboy.

Artifacts of study.

The Dallas Cowboys politely passed on this project. Those were the words I got in an email. “We are going to politely pass,” and the polite part seemed a matter of opinion, but OK. I did speak to about 30 cheerleaders from the past half century, and about a dozen of them appear in the podcast, alongside historians and cultural critics, but the cheerleaders carry this story. They talk about things many of us face — a search to discover their own talent and feel special, a struggle with their bodies, a hope that they can balance the inevitable frustrations and criticisms of an experience with the enormous gains they got, a frustration when their contribution is not valued (sometimes monetarily, sometimes in the public perception), a craving for the spotlight and the challenge of that scrutiny, a desire to be sexy but not just sexy.

Some of those conversations lasted five and six hours, and over the past months, as I labored to assemble an eight-episode podcast (with much help from my Texas Monthly team), I found myself overwhelmed at how big this project was and also frustrated by how much I had to edit, condense, and skip. Sometimes I feel like I still can’t get my hands around this thing.

But I never got tired of talking to the cheerleaders. There was often this moment, at the start of our interview.

“So is this a video?” they’d ask, watching me assemble the metal cranes of sound equipment.

“No, this is audio only.”

“Oh good.” And I could feel them relax, and they’d sit however they wanted in the chair, and not worry if they were wearing lipstick or their hair was a little messy.

“This,” I’d say, taking a seat across from them, “is about your voice.”

AMERICA’S GIRLS is an eight-part podcast that debuts on December 7, 2021, available on Apple podcasts and wherever the hell else you find podcasts.

The post Why I’m Doing a Podcast on the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders appeared first on Sarah Hepola.

May 1, 2021

How Deep Is Your Love

The first night we spent in each other’s company, I slid into the passenger seat of his car and flipped through the songs on his stereo. He had one of those screens that was probably standard, but I’d never seen it before, having spent the past six years in the backseat of yellow cabs during the era when cars went digital. Ordinary things seemed fancy to me.

“This one,” I said, and touched the play button so the disco twinkle of the opening filled the silent air. And then that blast of three-part harmony, gentle as a sigh. Ahhhhh, the Gibb brothers sang as he rolled the car out of the parking lot and onto the empty street of an unfamiliar neighborhood. He was quiet as he drove, but he seemed to be watching me out of the corner of his eye, my body dipping back into the sound, or maybe I just hoped he did.

“You like some old shit,” he said.

I didn’t know whether this was a compliment or an insult, but I was badly hoping it was the former. I wanted to impress him. I wanted him to want me. This has been true of most men, but especially him.

“Frank Sinatra is old shit,” I told him. “Ella Fitzgerald is old shit.” But a radio hit from 1977? Hardly qualifies. “The Seventies is vintage pop,” I said, and watched his eyes settle into this subtle distinction. I’d spent the past few years re-discovering ELO, Queen, Boston, Fleetwood Mac. That post-Beatles era was a wonderland to me.

I know your eyes in the morning sun

I feel you touch me in the pouring rain

And the moment that you wander far from me

I wanna feel you in my arms again

The song felt like swaying under low lights. The song felt like being the last two people on earth. The song felt like falling in love. And after that night, the song felt like him.

I listened to it over and over as I drove around my home in Dallas. On the way to Whole Foods, in rush-hour traffic, watching the wet blue noodles slap my windshield in a car wash.

And you come to me on a summer breeze

Keep me warm in your love

Then you softly leave

And it’s me you need to show

How deep is your love?

I saw him again. Months had passed, but we were back in his car. He had a habit of changing a song after the first verse, like he’d already lost interest. It was a form of scrolling, and eventually, I’d come to see it as the sign of a distracted world, inflamed by platforms like Twitter and TikTok, where nobody could dream of holding a thought for more than thirty seconds. But at the time, I saw it as an expression of his interest in women, and possibly me. Not this, not this, maybe this — no, not that either.

I tapped his stereo to play “How Deep Is Your Love.” Or maybe he did, I can’t remember now, and I gave him a look that told him we were playing this one till the end. I loved the boldness of the chorus, how it dared to repeat itself, like maybe the second time you asked the question, the answer would be different.

How deep is your love?

How deep is your love?

How deep is your love?

I really mean to learn

“It’s such a weird question,” I said, wanting to extend our time together. He had parked alongside the curb; it was my turn to go. “How deep is your love? It almost sounds like a bad translation. Like someone whose first language isn’t English.”

“Well, they are Australian,” he said.

“They are?” Genuine surprise; I thought they were British.

“That was a joke,” he said.

“Oh,” I said, and laughed weakly. “Of course it was.”

I hated when I couldn’t keep up with another person; I never hated it more than with him.

I kept listening to the song. I’m just this way. I get stuck on a song, and I’m in its grips until it teaches me whatever I need to learn. A friend called this “hopelessly immersive,” and it’s a form of listening that tells you something about how I experience art, but also how I am with men.

This was my favorite part:

‘Cause we’re living in a world of fools

Breakin’ us down

When they all should let us be

We belong to you and me

Usually my fixation on a song has to do with the lyrics, the word puzzles of Tom Waits and Elliott Smith and Lana Del Rey have served me on long drives and lonely nights. But the lyrics to “How Deep Is Your Love” are simple and even saccharine in a way I don’t normally tolerate. Clearly the words were not what I was chasing. In fact, I didn’t even know some of the lyrics until I googled the song to write this piece.

I believe in you

You know the door to my very soul

You’re the light in my deepest, darkest hour

You’re my savior when I fall

I actually thought this last line was “you’re my savior when I’m born,” which makes no sense, but that tells you how little I had tried to unpack the song’s meaning. The song was more of a feeling. The song was an assertion, a wish. A kind of pining. I really mean to learn. (By the way, I always thought the line was, “I really need to know.” Whatever, I was close.)

I kept returning to “How Deep Is Your Love” for the better part of a year. It was replaced by other songs, other wishes. The guy disappeared into his world eventually, and I attached to other men, had familiar longings. It’s unclear to me if other people listen to music this way. Not long ago, helpless in the grip of another pop song, I texted one of my more OCD friends.

“How many times in a row have you listened to one song?”

“Hmm,” he texted back. “Maybe ten?”

Oh God. I had beaten him by degrees of ten. I literally had not listened to any other song for more than a week. This was extreme, even for me. It was yet another song with lyrics that were not the draw, but it had that immaculate Seventies groove that felt branded on my nervous system.

Are we all just chasing our past? I was born in 1974. My mother listened to classical music, and Simon & Garfunkel, and early Beatles albums, the ones “before they got weird.” The songs of my childhood bedroom were the Top 40 hits of the Eighties: Michael, Madonna, Prince. So if this was nostalgia, it was borrowed from someone else’s closet.

“How Deep Is Your Love” came on my stereo this morning while I was driving. I have one of those cars with the digitized song book in the console. I bought the car in 2013, but it’s an outdated system now. The GPS that seemed fancy when I bought the car is so cumbersome I just use my phone.

But the song had maintained its hold on me. I turned it up as I drove the familiar streets, my body dipping back into the sound.

And you may not think I care for you

When you know down inside

That I really do

And it’s me you need to show

How deep is your love?

I watched the Bee-Gees documentary last December when it came on HBO. It was good, although I fell asleep thirty minutes, and later I admitted this to a documentarian, who laughed and said, “Yeah, I probably shouldn’t be able to watch a documentary about a band in the Seventies with my seven-year-old son.”

But this one part of the documentary stayed with me. Noel Gallagher, whose songs have also cast a spell on me, was talking about the power of those three voices knitting together.

“When you’ve got brothers singing, it’s like an instrument that nobody else can buy. You can’t go buy that sound in a shop.”

That was it. That’s what I’d been chasing.

It wasn’t the words. It was harmony.

The post How Deep Is Your Love appeared first on Sarah Hepola.

April 24, 2021

Nostalgia in the key of metal

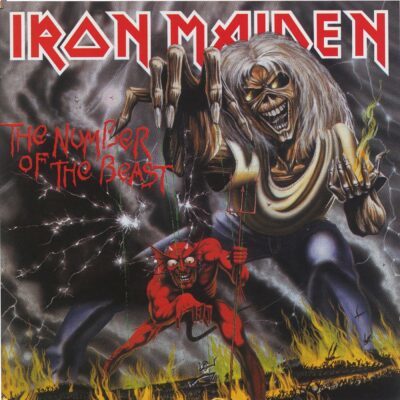

The young woman jangling keys to the dressing room is wearing an Iron Maiden shirt. Three items drape over my right arm, all of them designed for her demographic, but that shirt is straight out of mine. My older brother used to listen to Iron Maiden, a blunt counter-point to my Whitney Houston, and the pummeling sounds drifting from his bedroom were the stuff of aspiration and nightmares. Part “I gotta listen to that,” and part “What is wrong with people?”

The dressing room door swings open, and I pause her. “I have to ask. Do you like Iron Maiden?”

“Oh.” She plucks at the hem of a baseball jersey with a Skeletor figure playing guitar. Iron Maiden album covers were uniquely creepy. I remember shuffling through my brother’s cassette collection, which he kept in a narrow wooden Sound Warehouse crate. Skeletor in a wig, Skeletor with a flag, Skeletor taking a bite of the globe. He had seven or eight Iron Maiden tapes. “No, I haven’t,” she says, looking like she’s been busted.

“My brother loved them.” The angry teen boys of the Eighties would have enjoying seeing a cute girl in the mall in an Iron Maiden shirt. She has that incidental prettiness, ponytail and jeans.

“Cool,” she says, and bounces away.

British artist Derek Riggs did the Iron Maiden album covers. I will confess I love the song “Run to the Hills”

That was the moment I noticed the Eighties metal surge. I hadn’t been shopping much in the past year, go figure, but I began seeing shirts in window displays at mid-range women’s boutiques, folded on the tables next to $140 jeans. For years I’d watched Eighties nostalgia marching into Target, but this was a level beyond Prince and Blondie and Michael Jackson. This was Poison and Led Zeppelin and AC/DC, selling to Taylor Swift fans for $40 a pop. The shirts were soft and intentionally faded, simulating an old iron-on, although nobody ironed anymore.

I had a lot of those albums, back in the day. The record player lived in my room (my brother mostly listened to his Walk-Man), and I filled a white plastic crate with glossy cardboard portraits you could flip through. I dabbled in metal, worshipful little sister that I was, but my passion was Top 40. Lionel Richie with arms folded in a white suit, Madonna with her platinum blonde locks and black licorice bracelets lining her wrist, George Michael with his scruffy beard and black leather jacket, one cross dangling in his ear. They were like Mona Lisas to me.

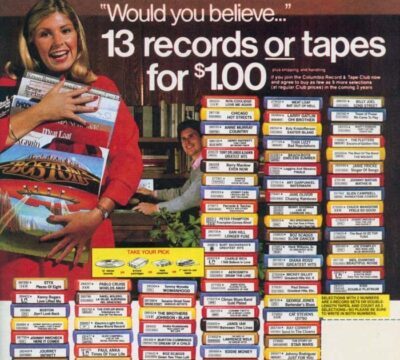

I signed up for the record and tape clubs, because all those albums for a buck were a steal, and then I’d bail on the full-price obligation, the monthly selections that arrived in cardboard. I’d learned your credit erases at 18 (or rather, you have no credit), so I ignored the overdue bills that arrived every other week, omen of the Visa and MasterCard bills to come, and I took out memberships under slightly different names, Sarah Hepla, Sara Hepulah, as albums turned to cassettes turned to CDs turned to VHS. As the teen movies understood, the line between hero and scoundrel was very thin.

The saga of Columbia House: Story for another time.

But the albums became the lost art. Through the Eighties and Nineties, I got swept up in new platforms, the big silver JamBox that could be unplugged from the electrical stream, or the Sanyo stereo system with a five-disc changer, like I was some oligarch. Relax and let the machine change the CDs for you. Those systems came with a remote control, so I could lie in bed with ankles crossed, skip a track, repeat a track. Turn it up.

But somewhere around the turn of the century, music went digital. Music disappeared, even as it became ubiquitous. CDs and cassettes looked suspiciously like landfill. All that plastic. CD towers clustered in second-hand stores, like skyscrapers from a forgotten skyline. And what emerged bright and shiny after the transition was the singular beauty of vinyl.

Almost Famous came out in 2000, a movie of deep nostalgia, and it included a voluptuous scene of the young Cameron Crowe stand-in tracing his fingers along the Bob Dylan and te Beach Boys and Joni Mitchell albums his sister left behind, as Simon and Garfunkel’s “America” plays in the background, a song so critical to the wandering soul of this movie that we hear a full two minutes before the incendiary opening of The Who’s Tommy. The scene is nearly sexual, his fingers moving with wonder and hunger, like a boy who will grow up to graze the hot spots of a woman’s back, searching for the same magic.

I bought a record player around 2013, in my late thirties. I was spending a lot of time in vintage stores, which sold albums on the cheap, and the player was an impulse purchase. It was the portable kind they used in schools, probably Seventies-era, and the guy I was seeing teased me for my lack of consumer discretion. He was an audiophile, who knew tones and speakers and shit, and here I was buying a rinky-dinky record player that announced every song with a high crackle, but that’s the kind of crappy record player I had as a little girl. I was not chasing the best sound. I was chasing the best feeling. I bought the Xanadu soundtrack, that futuristic art-deco cover, and I played it as the two of us lay in bed, losing ourselves in each other.

A place where nobody dared to go / The love that we came to know / They call it Xanadu

It was around 2018 when I bought a fancy Technics system. That guy had been gone for more than a year, but maybe I was trying to summon him, because he would have approved of that system. You could sit back on the couch and feel the music rise around you. The surround speakers were so complicated I had to hire a technician to install them. He kneeled on the brown shag carpet in a yellow polo shirt and khakis, whittling a wire with a pocket knife, first red, then black, and I could see how out-of-my-depths I’d been, trying to figure this out with the YouTube instructional video.

I met another guy around this time. He was the first man I’d been drawn to in so long I was practically covered in cobwebs, and he was much younger than me, which came as a surprise. He sat on my couch flipping through the vinyl albums like they were stone tablets. He picked up ELO’s Out of the Blue, that rainbow neon spaceship that looks like the game of Simon. I was straddling him on the couch, and I plucked the album from his hands.

“See what you missed, child of the Nineties? With your paltry CD collection, and flimsy inserts?” I creaked open the album as though I were spreading my thighs for him, and I watched as his dark sparkling eyes roamed the lyrics, and his fingers touched the glossy cardboard.

“You know they sell these at Urban Outfitters,” he said, his no-big-deal voice, and I smacked the album closed on his fingertips. How I adored a smart-ass.

“Not the same thing,” I said, but mostly it was the same thing. My coy display was meant to illustrate the rare luxury of my youth, but that luxury had been available for purchase next to Japanese cosmetics and “Keep Calm and Carry On” merchandise for well over a decade. I’d hung a James Dean poster on the wall of my childhood bedroom, which I bought before I’d ever seen a James Dean film, so it’s not like I was unfamiliar with this phenomenon. Generations of kids growing up with John Lennon and Marilyn and Jim Belushi shirts, like dead pop-culture versions of the saints.

The younger guy lit up my world for a long time, but things were always tricky with him, and he’d grown scarce, and I’d gone shopping to take my mind off that. A pandemic check arrived, a good excuse for a splurge. I met a buddy at Josey Records, and we wore masks as we dug through rolled-up concert posters of REM and The Smiths and flipped through stacks of vinyl, and my cart filled with a miniature Ms. Pac-Man game, a Star magazine tabloid from 1988 (“George Michael broke my heart, Brooke Shields says”), an original bumper sticker from the Q102 Texxas Jam. I never even went to that concert (I was eleven), but I got a hit of nostalgia from the design I saw on the back of cars for years. That cool ombre coloring, yellow to burnt orange.

Nostalgia is a homesickness, at least according to the Google search I just did, and despite its enormous market, particularly among Gen Xers, nothing about nostalgia sounds healthy: “a wistful or excessively sentimental yearning for return to … some past period or irrecoverable condition.”

An excessively sentimental yearning to return to some irrecoverable condition. Ding-ding-ding. Some people call it an affliction, but it’s more like a job description for me.

A few days later, I was grazing around uptown, and I ducked into a cutesy boutique, and I ran my fingers along the soft cotton shirts on the table, and there was the metal again. Def Leppard, KISS, Ozzy Osbourne.

“Can I help you?” asks a pretty millennial sales clerk in a ruffly sleeveless pantsuit.

“I have a question,” I say, plucking out a Def Leppard T-shirt with the pointy 80s font that reminds me of Gibson Flying V guitars. “Can you name a song by Def Leppard?”

“Umm, no.” She blushes. “But my boyfriend listens to them.”

“It’s weird, because my guess is that every girl who buys this shirt does not listen to this music, and I’m trying to figure out why the shirts are popular.”

A young woman who has been scraping hangers along a nearby rack turns to us. “So I have that shirt, and I couldn’t name a Def Leppard song. I know it’s stupid, but I liked the design.” Faded black, a growling leopard face. Not my deal, but whatever.

“Their early albums are good,” I tell her. “’Photograph‘ is a classic.” I don’t mention that “Pour Some Sugar on Me” is an assault from which we may never recover, but you can hardly blame a band for their success.

“I’m sure all the music is good,” says the pretty millennial sales clerk.

“It’s not,” I assure her. The Iron Maiden shirt is at the far end of the table, but I pick up an Ozzy Osbourne. “This is a very specific taste. I can’t say I’d recommend it. But a lot of the music — yeah, you’d like it.”

“I’m gonna listen to Def Leppard soon,” says the girl who owns the shirt.

“Photograph,” I tell her.

“Photograph,” she says back.

“Well, I consider my work done,” I tell them, and we each go back to what we had been doing. Two women scouring the merchandise for something, anything, and one woman pacing the floor till the moment she can ring them up at the cash register, consumer cycle complete.

The post Nostalgia in the key of metal appeared first on Sarah Hepola.

April 5, 2021

His customary and legendary range: Larry McMurtry, 1936-2021

The Lonesome Dove miniseries rolled into town in 1985, when I was eleven years old. Back in the before-times of the mid-Eighties, computers were clunky green-screened things known to your serious nerd variety, and the television was the center of the household. We built cabinets around our televisions, we kept drawers underneath it, in case anything important fell out. The televisions were enormous and wide as fish tanks (people actually turned them into fish tanks). There were only three channels, so if you didn’t like what was on, you could suck it. But most of the time, you did love what was on, because television was designed for mass consumption and maximum pleasure.The funniest comebacks, the most satisfying storylines, the most attractive humans. And onto this pasture, the Lonesome Dove mini-series galloped, with its squinting cowboys and pretty supporting females, and everybody in my affluent Dallas school was watching it — except for me.

I was a TV junkie, but I did not watch Lonesome Dove, and I’m not sure why. Kids at school enjoyed it with their parents, cross-generational bonding over a mythic landscape, but my parents were Philadelphia do-gooders transplanted to north central Texas, and they had little interest in Texas Rangers and dusty Western romance. My mother thought television rotted your brain (which is probably why I coveted it so much). I remember getting grumpy over that show, because people raved about it for years, like a party to which I had not been invited, but the party kept recurring. By thirteen, I was babysitting in other people’s big two-story homes, and I spotted VHS cassettes of the mini-series lining their shelves. I had no interest. I was obsessed with the TV show Fame, until I became obsessed with the TV show 21 Jump Street. Talented kids at a New York magnet school, undercover cops at a Vancouver high school. Just the thought of grizzled old men in cowboy hats made me yawn.

In my twenties, I learned the name of the author of Lonesome Dove, which apparently began its life as a novel. Larry McMurtry. At the alternative paper in Austin where music and movies and books were sacred texts, people had a respect and even reverence for the guy, although it was easy to skate by without ever reading him, the way you can get an English degree these days (PhD probably) without reading Steinbeck. It just doesn’t come up.

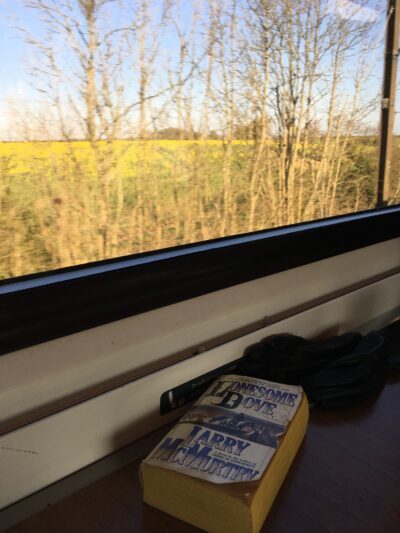

I was in my early forties when I read Lonesome Dove on a friend’s recommendation. Actually I watched the mini-series first, which held up powerfully well, despite some questionable mid-Eighties special effects, and it’s a sign of tremendous storytelling that after experiencing six-plus hours of drama on the trail from South Texas to Montana, I only wanted to take the trip again. I read the nine-hundred-page novel on a family trip to Scotland and then Finland, and I was so enthralled by the experience that I kept taking pictures of the book in various locations, posing it like the child or the boyfriend I did not have.

train from Edinburgh to London

Helsinki, Finland

It’s a mystery why we fall in love with some stories and not others. I can’t tell you the number of much-beloved, critically acclaimed books and TV shows I start and never finish. I just don’t care. I don’t need to take that trip, which is not a judgment on the creator but an expression of something I’m looking for and cannot find.

David Foster Wallace talked about the click you experience with a certain piece of writing, which is as good a description as I could muster. The click happens, or it does not. And as a devoted David Foster Wallace fan, I can assure you many, many people do not feel the click with his work. I’ve stopped telling people Infinite Jest is one of my favorite books, because I’ll be forced to listen to how they didn’t finish it, how their theory is no one actually finishes it (they’re wrong), how pretentious and unwieldy a book it is (did you miss the part where I loved it?). Anyway. I clicked with Lonesome Dove, and I clicked hard. I got mopey near the final chapters, and I wound up in a stupid fight with my brother. I didn’t want the book to end.

Let me flip through my creased paperback and share a few underlined passages at random.

He knew at once that he had forever lost a chance to right himself.

“You know more than you say and I know more than I know.”

The wind was endless and fierce. It renewed itself again and again, curling itself out of the north to take her flowers from her, petal by petal, until nothing remained but the sad stalks.

I loved the characters, even the mean ones. I loved wandering through that pitiless land, how endless the struggle. McMurtry wrote about women with great sensitivity and deep observation. He was not handsome (“he looked like a writer” is probably the kindest description), but I learned from profiles that he dated or was otherwise close to many women. His ability to capture female complication marks him as unusual among the late-20th century giants, many of whom I love but I’d grown accustomed to their clumsy hands. I came of age reading novels by and about men, it never bothered me, and I took it as a given that their portrayals of women were 10-50 percent more pale than the male protagonists. Not McMurtry. Everyone had range.

He co-wrote the screenplay for Brokeback Mountain with his writing partner Diana Ossana. It was a movie of tremendous longing, and maybe tremendous longing is the frequency of the song McMurtry was singing that I heard so crystal-clear. I just can’t quit you: That was the money line quoted so often it became a punchline. But its meaning was profound to me, and many others, in a changing world where the land remained pitiless even as it grew more accommodating. At many junctures, in many contexts, I just can’t quit something or the other.

I started plowing through McMurtry after Lonesome Dove. He wrote more than twenty books. All My Friends Are Going To Be Strangers was an early novel about a young writer coming in to his success and sleeping with a bunch of complicated women. (Huh.) I started Terms of Endearment but never finished it, never got far. The other books didn’t have the click. I didn’t fall for the characters in the same full-bodied way.

I liked his essays about small-town Texas in slim collections like Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen and Roads. The essays captured the migration from farm to city that realigned twentieth-century Texas (and America), from horses to trucks, from open fields to barbed wire. He grew up in the rolling prairies, a reader and a thinker who never much belonged, and he became a writer who never belonged in LA or New York or even Austin, which is why he stayed in small-town Texas, despite being the man who wrote so eloquently about its demise, and some part of me felt understood by this dislocation. A person gets forged by a landscape they never wanted and it shapes you so that you don’t fit anywhere else. I just can’t quit you.

Larry McMurtry died last week. He was 84 years old. He lived in Archer City, about two hours northwest of Dallas, the dying town he immortalized in The Last Picture Show, where he ran a book store, the one and only reason most people visit Archer City. McMurtry grew up in a home without books, but he became a rare-book collector. For years I heard stories of book nerds like me traveling to the place, wandering the endless stacks, hoping to catch a rare glimpse of the man himself. He had a reputation as a crank (maybe he was shy, who knows), and twice over the past years I’ve been on my way to Archer City when plans changed at the last minute. A pandemic struck, maybe you noticed. All the bookstores closed. They closed so long I got to wondering if they’d ever open again.

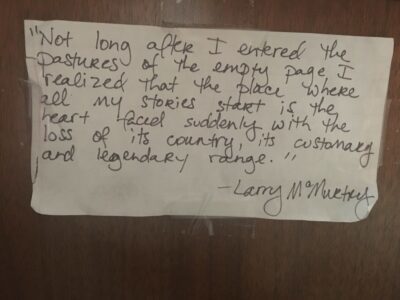

I keep a quote by McMurtry taped on my bedside table. My house is dotted with quotes written on yellow legal paper. They’re meant to inspire me, but often they become invisible, and I forget they’re there until people come over and ask why John Stuart Mill is on my refrigerator, and it’s like: Oh, he is? What did he say? (“He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that.”) But I kept McMurtry beside me as I slept. I never forgot he was there, never. I read the passage from time to time and was swept away by the rhythm of the language, its easy gallop, how it articulated something I needed to hear but had not known how to say about the book I was currently working on, struggling with, but could not quit.

The heart faced suddenly with the loss of its country.

Its customary and legendary range.

I was sad when Larry McMurtry died, but everyone dies, and 84 years is a good long life. His death made me think of lost prairies and empty pastures and things that never came to pass. I felt a stab of regret I didn’t make it to the bookstore while he was still alive, which hardly makes sense, since I almost certainly would not have seen him. But I wanted the hope and wish of knowing he might be lurking there, hidden in the stacks. But here is the magical part about writing: He still is.

The post His customary and legendary range: Larry McMurtry, 1936-2021 appeared first on Sarah Hepola.

February 7, 2021

Can’t Take the Texas Out of the Girl

In my fourth decade in this state, I finally became a real Texan:

You Haven’t Driven in Texas Until You’ve Driven a Pickup Truck

“When I first heard about this “car culture” issue, I knew what I wanted to write: an ode to my Honda Accord, which I’d driven across the country a half-dozen times. For 20 years, I’ve only ever owned a Honda sedan—one after the other, like a woman who keeps marrying and divorcing the same man. I think of those cars as trusty, no-drama companions that have carried me across fearsome interstates and rambling backroads. And my editor liked the pitch, but he had one small adjustment: Could I write about pickup trucks instead? But I’d never driven a truck, I started to respond, but then I realized that was the point.”

Here’s the portrait photographer Sean Fitzgerald took of me in Fair Park.

Aaaand here’s the selfie I took of myself in Fair Park. (It was slightly windy.)

Long live zero-proof cocktails, aka virgin cocktails, aka mocktails, aka the ginormous and untapped market of tasty and nuanced drinks that don’t have booze:

Sophisticated Non-Alcoholic Beverages Are on the Rise in Texas Bars

“In the decade since I quit drinking, something remarkable happened: The nonalcoholic beverage market exploded. In addition to flavored seltzers and surprisingly good nonalcoholic beer, botanicals, shrubs, and sophisticated elixirs have become increasingly available. This was driven in part by healthier lifestyles. At a time when organic, keto, and gluten-free have become common terms, younger generations seem much less enamored with getting hammered. Considering about 30% of American adults didn’t drink at all in the past year, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, acknowledging this demographic only makes sense. Big Booze has scrambled to take advantage of the nonalcoholic trend.”

Justin Lavenue, owner of Austin’s Roosevelt Room, mixing one of the bar’s three N/A cocktails

Like so many viewers on Netflix, I was captivated by the kids on Cheer, the docuseries about cheerleading at Navarro Junior College. Then, I got to know the town that they call home:

How Corsicana Has Captured Hearts by Defying Small-Town Stereotypes:

I used to pass small towns and feel sorry for the people who lived in them. What could you do there? Who could you be? Much of modern life was such a race to be exceptional—the biggest house, the most followers—that I felt a hint of sadness staring at those rusty warehouses and abandoned shacks off the highways of rural Texas, a land that time forgot. But something happened as the technology age unfolded, with all its virtual bustle and ambient anxiety—and I became a woman who sniffed around small towns looking for a hit of what they had. A slow-pour pace, a sense of community, something called affordable rent.

I went to an annual celebration of the 1969 Bonnie & Clyde movie in Pilot Point, Texas, which got me thinking about the duo’s lost legacy in my own hometown:

What Do We Really Know About Bonnie and Clyde

“The best way to characterize the relationship between Dallas and its notorious criminal duo would be to say there isn’t one. No museum, no murals, and certainly no festivals commemorate the fact that two dirt-poor kids from the west side grew up to become a Romeo and Juliet for the “public enemy” age. The only official designation is a historical marker near Clyde’s grave, in an Oak Cliff cemetery. But it’s the gravestone’s epitaph, written by Clyde, that tells the truer story. Etched in black granite are the words “Gone but not forgotten.”

Two poor kids from Dallas who were Instagram-ready.

The post Can’t Take the Texas Out of the Girl appeared first on Sarah Hepola.

November 18, 2020

Bread

On a blustery Saturday, I decided to bake bread. It was 10:30am, and I had never done such a thing before, but I imagined myself in the kitchen kneading the pale powdery squish of the dough with my hands, folding toward and pushing away. I’d recently bought a recipe book from an old hippie commune where the author described home bread-making as a sensuous activity, a spiritual activity. “Something inside felt met,” he wrote about kneading dough for the first time. It was eight months into the pandemic. Something inside me had not been met for a long time.