Sarah Hepola's Blog, page 2

October 21, 2020

Other People’s Postcards

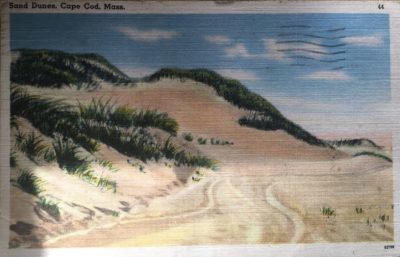

Many years ago I began collecting old postcards. I found them in vintage stores, stacks upon stacks of messages once sent, or never written, and I’d settle into an armchair and leaf through them, wafting with the smell of other people’s basements. I never knew what I was looking for, but then something caught my attention.

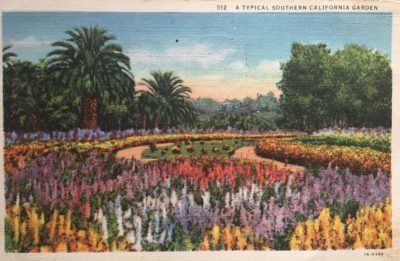

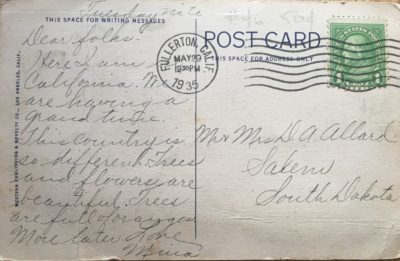

I was drawn to the mid-century postcards with white borders and the clean small font at the top placing a pin in the map. A Typical California Garden: Bit of an oversell for this one, but OK. The pictures looked like photographs that had been painted, usually in pastels more lush than real life (an early Instagram filter, a goosing of reality), on card stock that felt like linen, a gratifying hatching under the fingertips. My eyes scanned for certain details. The delivery stamp marked 1935. A postage stamp that cost a penny. And the unadorned address. No apartment number, no zip code. A world so small that our recipients need only be identified by their name, city, and state, and the resourceful human tasked with delivering this note could find them. (“Oh, the Allards of Salem? Yes, I know the place.”)

I started collecting other people’s postcards around 2002, which was, not coincidentally, also when I began traveling the country alone. I could not have articulated this to myself, but I liked the companionship of the traveler across space and time, that sense of watching someone’s eyes open. This country is so different. I understood the urge to document and share an experience as it passed over your skin. I kept a blog, a platform that was new in 2002 but outdated by 2010, displaced by the social media giants that offered something like postcards sent all day long, to everyone at once, a fusillade of postcards fueled by the same impulse to document and share — this is me now, this is me then, this is what I was thinking, wanna hear? — but maybe it says something about me, or nostalgia, that the old postcards felt special and the real-time social media dispatches felt cheap and performative. It was so easy to post a selfie to Instagram, tap-tap boom, that I had come to admire the mighty odyssey of the humble postcard: A hand plucking the rectangle from a squeaky rotary wheel in a gift store, the dull graphite of a pencil pressed to the glossy white box on the back, the tongue licking the stamp (licking the stamp!), and the arduous cross-country journey — from blue postage drop to flat-bed truck to carrier bag to metal box where a red flag raised to alert the home owner of its presence. All of this work, all of these delivery systems marshaled so that one person could say to another: Trees are full of oranges.

Most messages were mundane. The text limitations of a postcard are punishing (like Twitter’s character count), and many users failed in the face of this challenge. Notes often began by needlessly explaining the picture, as if the card hadn’t done this work, then clarifying the writer did not have time to write, or didn’t have space to write, at which point they were mostly out of room and had to wrap up by announcing their intention to write later. The postcard writers of the Thirties and Forties and Fifties could have used some style pointers.

Every once in a while, I stumbled on a genuine moment.

This one’s hard to read. The money line arrives just prior to that half-way mark.

We were married this morning about 10:30 by Capt. F. D. Anderson of the Salvation Army.

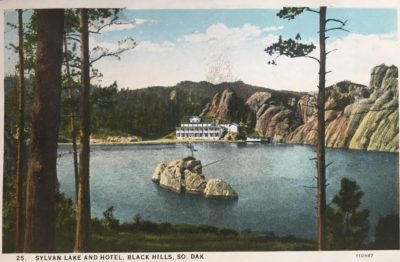

He just pops it in there, like oh right, and another thing. What was going on here? The note cascaded blithely across the address box, leaving the mystery of how the message was sent, and why a postcard had been chosen but its rules not followed, though the front of the postcard offered a clue. It was a fancy hotel on Sylvan Lake in South Dakota, presumably the location of the ceremony and/or honeymoon.

I had so many questions. Who were these newlyweds? Were they still married? Were they still alive? How had I procured two seemingly unrelated postcards from the sparsely populated state of South Dakota? (And who knew South Dakota had a lake?)

Maybe I collected postcards for the same reason I collected stories and books and sepia-toned pictures of strangers. They gave me permission to dream. Permission to step into someone else’s life, or alongside them for a moment. I was seeking the assurance that other people had been here, that other people had wandered and discovered. These were their adventures. These were their announcements (not enough room), their regrets (write more later), their dreams never quite fulfilled. Many of the postcards remained blank on the back.

It was not until writing this blog post that it occurred to me I could Google the author who was married in South Dakota. I could find this mystery man. The internet presented me with a complete narrative arc. Married in South Dakota, died in 1976. He and his wife had six children. I got that tug like maybe the children should have this postcard, but the fact that it was sitting in my hand suggested they did not want it, and so I would hold on to it, never knowing why, or what it delivered to me, but sensing the solemn duty we have to one another, to bear witness, to travel together.

The post Other People’s Postcards appeared first on Sarah Hepola.

October 6, 2020

How I spent my summer

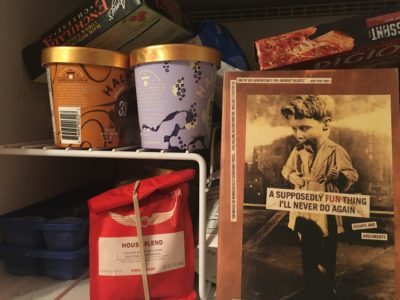

A few months ago, I was writing short posts on my favorite books, and then I stopped. It was late May, I was halfway through the list, which I’d begun thanks to one of those Facebook tag-a-friend schemes, the modern chain letter, and though I usually ignore those directives, I’d reasoned this one might be a bit of pandemic fun. I’d already taken a picture for my #6 choice, the David Foster Wallace essay collection A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, when the George Floyd video hit, followed by the chaos of the summer. I didn’t feel like writing anything.

Rallies, protests, riots. One Saturday morning, I woke up to news that a historic shopping mall had been looted, which turned out to be a shard in a much larger fracture: Smashed glass across downtown, but also many major cities. Trying to figure out what happened over Twitter felt like sitting behind a very tall person in a theater, and I kept craning my neck to the right and to the left, but I could not get a full view.

Frustrated, I drove downtown to see for myself, thinking I’d stay for a minutes; I spent six hours talking to people. Store owners, passersby, cops, construction workers hired to board up windows. I didn’t know if I was writing something, or just curious — this is often true about me — but I liked feeling part of a community. Volunteers walked down the street with brooms and dustpans, moving from one wreckage site to the next. I tried to engage one of them. “How did you learn about this?” I asked, and he shrugged and held up his phone. He was young, and looked vaguely hungover (he was wearing pajama pants), and did not seem terribly interested in speaking with a journalist, or a nosy person, or whatever I turned out to be, but I was moved by his small gesture of good will. He lived in the area, he said, and just decided to come help. All across the country people were waking up to stories of broken storefronts and uncontainable rage, but also true was that all over the country, people like this man were grabbing a broom and walking out their front door.

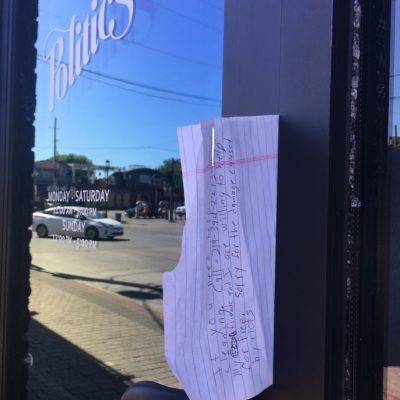

I saw this note tucked in the door of an emptied store in downtown Dallas called Sneaker Politics. It reads: “If you need help cleaning call [phone number] My friends and I are willing to help for free. Sorry about the damage caused by riots.”

There are moments when you sense how much you don’t know, and the summer of 2020 was like that for me. Destabilizing is the word. I read books. I listened to a million podcasts. I had so many “deep-dive stories” open on my laptop — about American history, race, society, policing — that I felt like I was in grad school. But I did not write much.

I did write some things. I wrote a magazine story about Uncertain, Texas, a small and mysterious town on the border of Louisiana that is home to the hauntingly beautiful Caddo Lake. I wrote about the Bonnie and Clyde legacy in Dallas, a dark episode in the city’s past that struck me as both wildly glorified and largely forgotten. I worked on the book I’ve been working on for some time. But the daily and casual act of tossing out words, especially on social media — I just didn’t do it. I wasn’t sure what to say. Stories felt stuck inside me. Every once in a while I came across the photo on my camera roll taken for the #6 entry in the book countdown — a picture of A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again nestled in my freezer — but now the photo struck me as posturing and self-consciously clever, two qualities I mistrust in myself.

A supposedly fun idea (but I do recommend the Halo Top, lightly melted).

I was starting to doubt so many things. I’d find myself staring out the windows of my sun-dappled kitchen into leafy oak trees of the neighbor’s back yard, thinking:

Why do I post on social media? What is the point of social media? What is the point of my life? Why why?

It was a long summer.

I took up gardening. Late in the afternoon, when my brain had turned to sludge, I went into the front yard that had remained untouched since I arrived several years ago, and I raked leaves and pulled up weeds. Some of the weeds turned out to be long deep vines that stretched across the yard, and I would tug in one place and sense the ground yield to my command, rippling across the earth as I yanked the stubborn thing from its roots like I was pulling up a buried cable wire. (Actually, I did that once, too.) I tugged and pulled and yanked and twisted. An act of editing done on the earth. I was nearly sad when the weeding was finished, and the plants were tucked into their beds, but I kneaded the ground around them with with soil and fertilizer, careful not to displace our earth worm friends, who occasionally bobbed up to the surface, grayish and trembling, startled into a ball by the abrupt change of lighting. I watered my plants every morning, and that was too often. (I turned out to be the gardening version of helicopter mom. This does not surprise me.) But in time I found something closer to balance, and despite my fumbling, the yard grew enchanting. Some nights I stepped outside and stood on the pathway and stared up at the moon in the sky. Voluminous, mysterious, bright, then hiding.

It’s October now. Dallas is cool and breezy and the mornings have that brisk shiver that has always signaled a new beginning. Fall feels like possibility. I have worn a sweater several times, I have clicked on my gas heater twice already, and I would like to start writing on this blog again, though I don’t want to write any more about my favorite books. (In case you were wondering, the books I haven’t included are Slouching Toward Bethlehem by Joan Didion, Tiny Beautiful Things by Cheryl Strayed, Lonesome Dove by Larry McMurtry, and Underworld by Don DeLillo, which were only in that order because that’s the way I found them.)

I have learned when you are stuck as a writer, the best way out is through. You have to write more, not less. The more you futz and fiddle, the more you suffer, the less you write, and lately I’ve been in futz-and-fiddle mode. Yesterday I wrote a list of writing prompts on slips of yellow legal pad and placed them in a glass jar in my kitchen to draw from in order to try to get myself going again. Fall has always been my favorite season. In the mornings when I’m taking a break, I stand in the doorway and stare out at the dried and mottled leaves that have given up in their clinging and fluttered to the ground. There is something so encouraging in the transformation. Not because things are dying. Because they are always changing.

The post How I spent my summer appeared first on Sarah Hepola.

May 23, 2020

# 5 White Teeth

part 5 of a 10-part series

I’ve written a lot these past few days, so I will just say this: Zadie Smith might be the perfect woman. At least that’s what I thought as I read “White Teeth,” one of those pyrotechnic multi-character novels about modern polyglot London. She was funny but deep, light but profound. And did you see that author’s photo? Pffft.

Zadie Smith was the first of the “brilliant young novelists” to be younger than me. No, I didn’t have any feelings about that [screams into pillow]. Twenty years later, I still get that “next-level” vibe when I dip into her words, most recently in the collection “Feel Free.” I read that book waiting for my high-lights to take at the salon, the big plastic egg of the dryer humming around my tin-foiled head as I read essays that were so finely observed, so elegantly rendered. “The perfect woman” is fantasy language. No one ever is. So let me say it this way. That imperfect woman sure did raise the bar.

The post # 5 White Teeth appeared first on Sarah Hepola.

May 20, 2020

#4 A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius

part 4 of a 10-part series

Gather round, young Snapchat and TikTok fans, and attend the tale of GEN X IRONY. The year was 2000. We used our phones for talking. Each time you logged on the Internet — which we called the “World Wide Web,” a phrase that was like sprinkling glitter from your palm — the computer made a catastrophic noise, a sound caught between a mechanical clunking and electric guitar screech. Life was hard. Our rock stars were miserable. We had to walk a mile in Birkenstocks just to send a fax.

Into this perilous moment walked the deeply precocious writer Dave Eggers, or as he identified himself on the copyright page of his memoir, David (“Dave”) K. Eggers.

The book was called “A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius.” In case that title didn’t tip you off, this book was clever. Different. The copyright page included such flourishes as the author’s height (5’11”) and Kinsey-scale sexual orientation, which he rated as a 3 out of 10, “1 being perfectly straight and 10 being perfectly gay.” As for his publisher Random House, an imprint you might assume needed no introduction, he had this to say:

“Random House is owned in toto by an absolutely huge German company called Bertelsmann A.G. which owns too many things to count or track. That said, no matter how much money they have or make or control, their influence over the daily lives and hearts of individuals, and thus, like 99 percent of what is done by official people in cities like Washington, or Moscow, or Sao Paulo or Auckland, their effect on the short, fraught lives of human beings who limp around and sleep and dream of flying through bloodstreams, who love the smell of rubber cement and think of space travel while having intercourse, is very very small, and so hardly worth worrying about.”

That was the copyright page. And I was in love.

Dave Effing Eggers. How do I even explain this to you? If you weren’t there. If you didn’t watch this book drop with a lonely whistle from the sky and detonate in the publishing landscape, the plume of mushroom smoke that hung around for years. People loved him. People hated him. Women lined up at readings to pledge their devotion and possibly angle for his sperm. I recall a headline from around that time: “Dave Eggers, No Problem Getting Laid These Days.”

I actually didn’t read the book in the beginning. The hype was unbearable, and I was inclined to take a pass on the Bay Area wunderkind until I stumbled on something he’d posted on the World Wide Web (cue glitter scattering) about the dangers of being a critic — not a professional critic so much as an armchair critic, someone who slumped on their couch in a torn shirt covered in Dorito dust and the shame of not trying, someone who sneered at others as they tripped and fell. (In other words, Twitter.) The post rocketed around the Internet in a way we now call viral and made its way to me, where I printed it out at the office of the cool alternative newspaper where I worked. I neatly folded the pages and carried them in my wallet for the next, oh I dunno, three or four years. I’d just never read anyone who could capture the mind’s voice in all its rumbling glory. The velocity of the prose. The familiarity of the struggle. Even the punctuation was riveting. It was just! So! Sincere — but also? (Maybe.) Sarcastic?

Yesterday, I pulled the book off my shelf where it has lived for many years. This is not a book I re-read. It is a time capsule. It is the year 2000, it is me at twenty-five, it is the world before the Internet swallowed us. I cracked the spine, and I found myself delighted by the author’s cleverness, then exasperated. Was this book ever going to start? There were rules and suggestions for enjoyment (“many of you might want to skip much of the middle, namely pages 239-351”), there was a preface and (because it was the paperback) a preface to the preface, pages upon pages of pirouetting and throat clearing and random shoutouts (“The author would like to acknowledge the brave men and women serving in the United States Armed Forces. He wishes them well, and hopes they come home soon. That is, if they want to.”) There was a contest for readers to send in a picture of their book being rubbed against by a red panda (“the lesser panda”). It was maddening. It was genius. The longest BuzzFeed listicle written by the most exasperating New Yorker contributor and etched in a soothing font on the side of a grain of rice. And yes I was still in love, because I wanted to throw the thing against the wall, which is obviously an act of passion. That’s how much I cared.

Oh, plot. The book is about the death of Eggers’ parents six months apart from each other, and how he raised his younger brother. I read it in one long gulp, similar to how it was written. The book also follows Eggers’ struggle to start a magazine called Might, which (this part isn’t in the book) eventually became a literary journal called McSweeney’s, which became a website and publishing imprint and later hatched a nonprofit writing program for kids called 826, which was also (briefly? always?) a pirate store, which I once visited. The pirate store had an antique curio cabinet vibe. I bought a tiny glass bottle, the kind you might toss into ocean waves, and inside was a curled slip of paper where someone had written, in pencil, “Thanks for finding me.”

This book changed my life. I guess you had to be there.

The post #4 A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius appeared first on Sarah Hepola.

May 18, 2020

#3 Drinking: A Love Story

Part 3 of a 10-part series

I was 22 or 23. I was in Boston visiting my college roommate Tara Copp, who had an internship at the Globe. I was killing an afternoon by myself, and I was hungover, because I was always hungover, so I was wandering through a book store when the title caught my eye. “Drinking: A Love Story.” That sounded familiar.

I’d come to the neighborhood to visit Cheers, the bar from the TV show, but it was closed or I lost my nerve to go to a bar alone, I can’t remember which, so I sat on a soft patch of grass in a park and opened the book. “It happened this way,” the story began. “I fell in love and then, because the love was ruining everything I cared about, I had to fall out.”

Damn. That sounded familiar, too.

All my friends drank. Of course we did. We’d gone to a hard-partying state school at the affluent tail end of the 20th century. But I was starting to suspect there was something darker about the way I drank. I had blackouts. I fell down stairs. This must sound dramatic but what would have struck you about me at the age of 22 or 23 is that I looked like everyone else. I bought a skirt that day at Banana Republic. It was loose and rayon, and made me look thinner than I actually was. I listened to the Counting Crows. I watched “Ally McBeal.” I only meant to dip a toe in the book that afternoon, but I fell right in. From chapter one:

“I drank when I was happy and I drank when I was anxious and I drank when I was bored and I drank when I was depressed, which was often.”

Shit yes, that was familiar. I’d never heard anyone talk like this, with such intimacy and precision, like some expert violinist had tightened the bow strings on my jangly, loose thoughts at 3am. And then I arrived at this:

“There are moments as an active alcoholic where you do know, where in a flash of clarity you grasp that alcohol is the central problem, a kind of liquid glue that gums up all the internal gears and keeps you stuck.”

I put the book face-down. A kind of liquid glue that gums up all the internal gears. Page fucking four, and she’d nailed me.

This was the summer of 1997, the year the book became a bestseller and launched a career for the author Caroline Knapp that would be far too short. The memoir was in a boom time. Book nerds and literary critics should feel free to correct me, but I think of the late-20th-century memoir boom as beginning with the one-two punch of Mary Karr’s “The Liar’s Club” in 1995, followed by Frank McCourt’s “Angela’s Ashes” in 1996, two barnburners that brought us inside the kind of chaotic, hard-drinking families the talk shows were calling “dysfunctional” and the talk therapists were calling “abusive” or “traumatic” but for some folks had just been life. The late Nineties coincided with the rise of Internet, where live journals and “online diaries” and blogs were delving into these kind of domestic battlegrounds, and it’s only in retrospect I see all of these as related, a longing for the first-person voice as technology pushed us farther away.

I read Knapp’s book once, and then again. I gave it to friends. I quit drinking at 25, started up again at 26, read the book at 30, 33, coming back to it like a mountain I did not want to climb but could not leave. Each time I saw more of myself. I’d never been pulled over for drunk driving the first time I read the book. Ten years later, I’d been pulled over twice. Knapp described red dots around her eyes from puking in the morning, broken blood vessels, and the first time I read that, I thought how gruesome, and later I thought how familiar.

I was 35 when I quit drinking. I was 40 when my first book came out, so clearly inspired by her memoir that I might as well have called it, “Blackout: Also a drinking love story.” Knapp died in 2002 at the age of 42. Lung cancer, dammit, the same disease that took her father. I was proud when any review of my book mentioned her. Maybe I was biting her style, but I liked to think I was carrying her torch, that we all were: Mary Karr and Leslie Jamison and Glennon Doyle and Ann Dowsett Johnson and Laura McKowen and Holly Whitaker and Amanda Ward and Jardine Libaire and all of us who stand in the long shadow that stretches out from the woman who placed a book on the shelf that was not about men’s drinking, which had been such an endless preoccupation of 20th century fiction. But this was a memoir. It was a woman’s story. It was a love story.

The post #3 Drinking: A Love Story appeared first on Sarah Hepola.

May 17, 2020

#2 The Things They Carried

part 2 of a 10-part series

In my junior year of college, I took a literature of war class. I’d been drawn in by the late-80s/early-90s Vietnam movies, Oliver Stone and Stanley Kubrick, and “war” sounded exciting, high drama. I didn’t know the class would be all boys, but that was a nice bonus. We read “The Things We Carried,” by Tim O’Brien, and I was sunk. I’d never read a book like this. Was it memoir? Was it fiction? The protagonist’s name was Tim O’Brien, but the author kept moving the goal posts, writing in a way that it couldn’t possibly be true. (Or could it?) The book had style, swagger, tragedy, danger, the book had all the things. The title chapter that opens the book lists the physical items carried by a 17-member troop marching through the swamps of Vietnam, the flashlights and the pocketknives and the letters from home and the dope, but the story moves outward, toward the emotional burden of that phrase, the things they carried. The following passage was taken at random, it comes from a part where the narrator is describing the awful experience of checking tunnels.

“How you found yourself worrying about odd things: Will your flashlight go dead? Do rats carry rabies? If you screamed, how far would the sound carry? Would your buddies hear it? Would they have the courage to drag you out? In some respects, though not many, the waiting was worse than the tunnel itself. Imagination was a killer.”

The writing had a you-are-there quality that rocked me. I was a girl, I lived in the slacker Valhalla of Nineties Austin, I was 20 years old wearing ripped jeans and a giant flannel shirt, but there I was in the jungles of Southeast Asia, lowering myself into the muck to slither inside that tunnel. When I watched war movies, I often wondered how I’d fare in battle. Maybe it’s silly, I would never go to war, but I couldn’t help being curious: Would I be brave? Would I be foolish? Would I be a coward? It’s a reasonable question. When the world tests me, who will I be? And O’Brien’s story was a complicated answer, it suggested that for many people, or for him anyway, the answer would be all of the above.

I dove into war literature after that. “Catch-22,” “Slaughterhouse Five,” Michael Herr’s “Dispatches.” I love them still. Something about the absurdity of war, the valor yes but also the futility of the carnage, created these masterworks of postmodern writing that just rearranged me. They changed the way I read, maybe even how I saw the world. I could never look at a tunnel the same way after that.

The post #2 The Things They Carried appeared first on Sarah Hepola.

#2 The Things They Carried*

In my junior year of college, I took a literature of war class. I’d been drawn in by the late-80s/early-90s Vietnam movies, Oliver Stone and Stanley Kubrick, and “war” sounded exciting, high drama. I didn’t know the class would be all boys, but that was a nice bonus. We read “The Things We Carried,” by Tim O’Brien, and I was sunk. I’d never read a book like this. Was it memoir? Was it fiction? The protagonist’s name was Tim O’Brien, but the author kept moving the goal posts, writing in a way that it couldn’t possibly be true. (Or could it?) The book had style, swagger, tragedy, danger, the book had all the things. The title chapter that opens the book lists the physical items carried by a 17-member troop marching through the swamps of Vietnam, the flashlights and the pocketknives and the letters from home and the dope, but the story moves outward, toward the emotional burden of that phrase, the things they carried. The following passage was taken at random, it comes from a part where the narrator is describing the awful experience of checking tunnels.

“How you found yourself worrying about odd things: Will your flashlight go dead? Do rats carry rabies? If you screamed, how far would the sound carry? Would your buddies hear it? Would they have the courage to drag you out? In some respects, though not many, the waiting was worse than the tunnel itself. Imagination was a killer.”

The writing had a you-are-there quality that spooked me. I was a girl, I lived in the slacker Valhalla of Nineties Austin, I was 20 years old wearing ripped jeans and a giant flannel shirt, but there I was in the Mekong Delta, lowering myself into swampy muck to slither inside that damn tunnel. It was tense, man. When I watched those war movies, I often wondered how I’d fare in battle. Maybe it’s silly, I would never go to war, but I couldn’t help being curious: Would I be brave? Would I be foolish? Would I be a coward? It’s a reasonable question. When the world tests me, who will I be? And O’Brien’s story was a complicated answer, it suggested that for many people, or for him anyway, the answer would be all of the above.

I dove into war literature after that. “Catch-22,” “Slaughterhouse Five,” Michael Herr’s “Dispatches.” I love them still. Something about the absurdity of war, the valor yes but also the futility of the carnage, created these masterworks of postmodern writing that just rearranged me. They changed the way I read, maybe even how I saw the world. I could never look at a tunnel the same way after that.

*part of a ten-part series on my favorite books

The post #2 The Things They Carried* appeared first on Sarah Hepola.

Ten books that changed me, starting with this one

Over on Facebook, a friend tagged me in one of those games where you post your favorite books for ten days. I figured I’d share the posts here, too, in case anyone is interested, and since I can’t seem to write a simple short post like a normal human but end up writing mini-essays like this one.

This task summons queasy feelings of inadequacy, in part because I’m not nearly the reader people expect. I’ve always been slow and fitful with books. I abandon most by the half-way point, and I just don’t care. My brother is a speed reader, but as a girl, I was so hooked on TV and movies that during one rough patch of second grade, my mother paid me a quarter for every book I finished. (A quarter! Ha, the publishing economy.)

It’s not that I didn’t like reading. I lovedlovedloved ten percent of books (Judy Blume, S.E. Hinton, stories about charismatic show dogs), but there was that other 90 percent. The other 90 percent could be a beating. I became a teenager who did not read books assigned in English class, something I considered cool at the time and something I find embarrassing now. I don’t think I’ll ever stop feeling criminally under-read, disappointed about the mind-expanding worlds I have yet to enter, but I will play this game, because a) I love Carey Burres, and b) talking about great books is contagious fun, even if it’s slightly exasperating for the list maker, and c) I suspect the nagging feeling that you can and should read more is one of the fundamental parts of being a reader.

Now that I’ve gotten that out of the way: Top ten books in the order I found them.

#1 DIFFERENT SEASONS

Fall of seventh grade, 1986. I’d read “Skeleton Crew” and “Night Shift”, mind benders, the perverse thrill of adult fiction, and I’d started on King’s novels, which I kept in chronological order on my shelf. Horror didn’t scare me; I wonder if it’s because I already felt so scared. I could freak myself out on a bridge imagining the rickety structure collapsing, so a story about the bogeyman in the closet was like: Right, that. (I also loved Edgar Allan Poe and Clive Barker.)

“Different Seasons” is the least horror-driven of the early King work. The 1982 collection of four novellas would inspire three films: “Shawshank Redemption,” “Apt Pupil,” and “Stand By Me,” the latter of which became my favorite movie that seventh grade year and was something like Playboy for tween girls who don’t like nudity but want to watch cute boys bonding.

The story that inspired “Stand By Me,” “The Body,” was BY FAR by favorite in the collection, four boys on a secret mission to find a dead kid. This is the blueprint for me: Deep friendship, family angst, psychological terror, substance abuse, the joy of storytelling. It’s the closest King got to a memoir, until his actual memoir “On Writing” in 2000.

I read “Different Seasons” so many times the spine split in two. The cover ripped off, and I held the precarious thing together with a rubber band, until I scraped together enough babysitting money for the hardback. No story had ever understood me like this one, and maybe that was the revelation: that I needed a book to get me. I wonder if that’s why so many of the other books weren’t landing. They were escape, but I wanted to be returned back to myself. I wanted a book to explain my thinking, my fears and desires, not whisk me off to another land. (Sidebar: A book can clearly do both.)

Over the next thirty years, I read a lot of books that explained me to myself. They would tug out aspects of my personality and cultural experience I had not fully articulated, and they would whisper things like: You feel this way, because you’re a woman. Or because you’re an American. Or because you’re an alcoholic, or a comedy nerd, or a romantic, or any other label that captures some aspect of me. But “Different Seasons” was the first book that told me something else, something that would prove foundational.

You feel this way, because you are a writer.

The post Ten books that changed me, starting with this one appeared first on Sarah Hepola.

May 12, 2020

Adventure awaits, and awaits, and awaits

Last October, I went rock climbing in Hueco Tanks, an hour north of El Paso in West Texas. I’d never been rock climbing, but it looked fun. This is the kind of questionable analysis that has lead to worlds of trouble, and oceans of fun. My guide was a younger guy named Jacob. We spent the afternoon noticing the sound of the wind in the trees, debating virtual worlds versus actual ones, staring at ancient pictographs on the inside of cave walls, and discussing how we might fare in prehistoric times (Jacob well, me not so well). I also spent plenty of time bouldering. I fell often, laughed a lot, and ripped up my tender pink hands.

This is a picture I posted to Instagram.

I’m not too athletic, but I try to stay teachable. This was the thrust of an essay I wrote about my climbing excursion that wound up on the cover of the magazine, the outdoors issue of Texas Highways. It came out in April. The headline: Adventure Awaits.

I saw the cover for the first time, two weeks into the pandemic. I was in line at Whole Foods, strangers standing a cautious six feet apart, most of us wearing masks. Adventure definitely awaited, but it was not the happy-go-lucky kind. The timing of my rock-climbing story was nearly comic. The opening described how I, as a writer, spent far too much time indoors. Ha. Why would anyone do such a thing? What had once seemed like lifestyle folly had turned to government mandate by the time of the story’s release. The “outdoor issue” piled on the rack, not one magazine taken.

Hueco Tanks at sunset, photo by Sean Fitzgerald

Over the next weeks, I thought about Hueco Tanks. It’s one of those desolate and glorious spots that people should visit, when they feel up to visiting again. Last February, I went there a second time to shoot pictures for the cover story. “I might be slightly nervous about doing this,” I told the photographer, Sean Fitzgerald, as we lingered outside the quonset hut supply store on the morning of the climb, watching scruffy dude-bros in hoodies practicing their chin-ups. This was not exactly a controlled environment in which to make myself vulnerable. No flattering studio lighting, no hair-and-makeup people. Sean told me not to worry. He had the kind of low-key affability that either means he’s a good dude, or he’s a very sneaky one who will kill you in the middle of the night. Well, I didn’t get killed.

My mom said this was one of her favorite photos of me.

Being photographed turns out to be a bit like rock-climbing. You gotta take a trust fall. I want to control the outcome, but the more I worry, the more I flounder. The more I think about my deficits, the more they are on display. I am forced into the moment, which I find a tricky place. It requires focus, and faith. I’m more of a specialist in sarcasm, and doubt.

I was smiling because I had just summited that boulder with Sean Fitzgerald’s camera in my face.

We wound up hiking a lot that day. Jacob was leading us, nimble as ever, and Sean managed these steep climbs with hulking camera bags slinging around him, I have no idea how. We were seeking unusual landscapes, so we wound up traversing a very tricky abyss that left my knees literally knocking together.

Now is when I tell you I’m scared of heights. I don’t like roller coasters. I get nervous on airplanes. I freak out riding the giant ferris wheel at the state fair. The boulders I’d been climbing were no big deal, but this drop-off had to be 100 feet. The plan was to step onto the edge of one boulder and jump onto another. Except the rock face was slippery, because ice was melting in late February. Except the ledge was thin. Except the 100-foot drop-off in between the boulders was so daunting I had to face the rock as I moved out, which left me stuck. Let me show you what I was up against (imagine a hundred-foot drop underneath Jacob):

Photo by Sean Fitzgerald

OK, so. It was a tight spot. I started to wonder if I might die doing a photo shoot for a magazine, and if this was heroic, or the opposite of heroic. I was vaguely aware of Sean taking photos during this time, and I thought: Good, my parents will need them for the criminal trial. Everyone stayed quite calm during this mini-crisis. I was like, “Hey, guys, I’m a little scared right now.” And Jacob was like, “There’s nothing to be scared of.” And Sean was like: *click* *click.*

Eventually, Jacob scooched himself up the rock and straddled the abyss with his feet so he could coax me to the other side. Why? Because his blood runs Viking, and my blood runs writer, and these are our natural states. I made it to the second boulder. My whole body was trembling. I got cold. Adrenaline spiking, then fading. Afterward, I couldn’t stop giggling.

Photo by Sean Fitzgerald

We climbed for a couple hours after that. I was tired. I often complained to Jacob (to anyone who would listen) that I thought my arm strength and my curvy size and my woman-ness were all detriments to my climbing, and he kept saying I was mistaken, the secret was practice, technique, confidence. That afternoon I saw this woman dominate an advanced boulder. It was like watching an ice skater nail a triple lutz; it brought tears to my eyes. That woman had brought her baby into the park, and her husband took turns holding the chubby-cheeked little guy as she climbed, and this made me tear up, too, because I’ve always thought of rugged adventure as a solo pursuit, not one for couples. Not one for moms. Then it was my turn to climb (a much lower) boulder. Jacob was in my ear telling me I could do this, and I know that woman was in my head, telling me the same. This is my favorite shot of the day, because I look so focused. I am in it. (Also, my hair looks really good.)

Photo by Sean Fitzgerald

I’ve spent a lot of time on my own, not because I prefer being on my own but because it’s easier. You don’t get hurt. You don’t get disappointed by other people, who never can meet your outsized expectations. Solitude has been a practical downsizing for me. Easier this way. And I’m glad I can move around the whole like this. But it’s also nice to remember I like being part of a team. I become stronger, I’m pushed farther, and I usually have a better time. I’m a social creature in the end. Aren’t we all?

My heroes: Photographer Sean Fitzgerald and guide Jacob Garza.

We left the park after sunset. A long day had come to an end. But as always: Adventure awaits.

The post Adventure awaits, and awaits, and awaits appeared first on Sarah Hepola.

May 7, 2020

The Moon, She Refuses to Be Captured

I woke up at 4:30am, cat in a C-shape beside me. Last night I finished edits on a magazine story, and I can never sleep long after that. My brain stays in hyper-vigilant mode, too much adrenaline I suspect. As I lay under the covers, I could see rivers of text on the galley proof in my mind’s eye, three neat rows spilling over five pages, but I didn’t want to think about the text, because what if I remembered a typo? A mistake? Too late. The story had shipped.

I made coffee in the red kitchen, cracked open the wet food as the cat scrabbled his paws against the white cabinet in anticipation, our morning ritual. I passed a window, and that’s when I saw her: The moon. A full and luminous moon in a clear sky on a cool May morning near the end of a quarantine. I had the urge to step outside. I normally write first-thing upon waking, but two months of a shelter-in-place mandate, and you start doing strange things.

I tugged on jeans and a flannel shirt in my still-dark bedroom, slid on flip-flops, and headed down the stairs and out to the street with my mug of coffee. I could see the moon teasing me through the tree tops as I wound along the leafy sidewalk to the clearing for the full and unimpeded view. I took a seat on the curb, rested my chin in my hand. The moon, y’all. The moon! I started to take a picture with my iPhone, but the screen showed a long white smear going sideways, and I couldn’t bear to see her like that. I read once why you can’t take a proper picture of the moon, but it never stopped me from trying.

I tapped the playlist I’d been listening to for weeks. Simon & Garfunkel. The songs were short and pristine, a few revved me up and a few calmed me down. Not too long ago, I watched “The Graduate” and found myself newly captivated by the depth of the songbook (also the movie). On my walk last night, I played “The Only Living Boy in New York” over and over again. I’ve been like this with songs as long as I can remember. Again, again. A repetition somewhere between love and need. Little kids are like this, so maybe I just never grew out of it. I tapped the word “America,” and the gentle hum of the opening bars joined me on the street corner.

My mother liked Simon & Garfunkel. I remember the covers of the vinyl albums in the stacks that lived beneath the bookcase in the living room, those two men’s stark faces in the mix alongside Peter Paul & Mary and early Beatles albums. Mom liked folk music, feel-good sing-alongs. I guess I thought Simon & Garfunkel were sweet and light, the equivalent of restorative yoga or a nice chai tea, but they’re actually light and deep AF. Not too many pop songs can rival “America.” I saw the story unfolding each time the music played: Our two young wanderers boarding the Greyhound to Pittsburgh, the countryside turning to a motion blur as the bus barreled through the night, the woman drifting off as the man stared into darkness. I felt something like a gasp each time I reached that one line.

“Cathy, I’m lost,” I said, though I knew she was sleeping.

Goddamn, Paul Simon. I stared up at the moon. The line kept going.

I’m empty and aching and I don’t know why.

It was one of the saddest lines in pop music. I’d spent twenty years wondering if I’d turn on that line, decide it was too literary, too on-the-nose, but it never struck me as less than perfect.

A rustle on the sidewalk, and I tore myself away from the moon to find a woman walking her dog, a pit mix probably, brown with white splotches. I felt slightly busted, and I raised my hand in greeting as I punched down the volume on my phone. I was doing that thing I can’t stand in other people, playing music without ear buds, subjecting everyone else to my song selections, but the street had been empty up to now. The dog sniffed a patch of grass and another as the woman walked patiently behind.

“She’s a handful,” she said to me, looking the other way as the dog did her business. The woman chuckled to herself. “I can’t choose the right man, I can’t choose the right dog.”

It’s funny what a stranger will tell you. “I can’t choose either,” I said.

My coffee was gone now, the song was done. I wanted a second cup, but I knew it was a mistake. Every time I made a second cup of coffee, I regretted the decision. Literally every time, had to be a lesson in that. I walked back into the house, the mug dangling from my fingertips. The big gray cat flopped on the ground, rolled on his back as I rubbed his soft tummy, our front-door ritual.

“You ready?” I asked. “You ready to start the day?” But he was ahead of me, galloping up the stairs again.

The post The Moon, She Refuses to Be Captured appeared first on Sarah Hepola.

Sarah Hepola's Blog

- Sarah Hepola's profile

- 328 followers