Paul Bishop's Blog, page 8

September 18, 2019

TAGGART—SCOTTISH NOIR

TAGGART—SCOTTISH NOIR

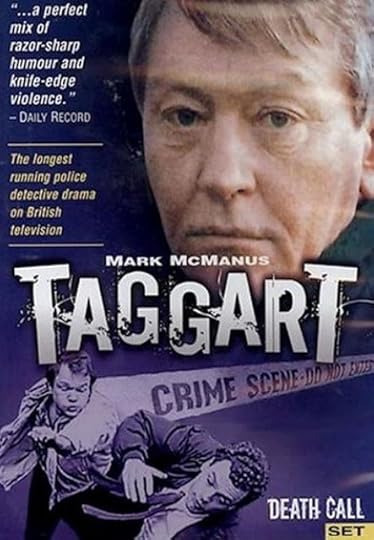

TAGGART—SCOTTISH NOIR Taggart is a Scottish detective TV show shown on Britain’s ITV network. It made its first appearance as a mini-series entitled Killer in 1983. Eventually a full series was commissioned, which ran from July 1985 to November 2010. The actor’s Scottish accents were so thick they were rendered virtually indecipherable, making close captioning essential when viewing.

The series revolved around a group of detectives assigned to the Maryhill Criminal Investigation Division, part of the Strathclyde Police. The team operated out of the fictional John Street police station, but many cases took them to many parts of Greater Glasgow and beyond.

The series revolved around a group of detectives assigned to the Maryhill Criminal Investigation Division, part of the Strathclyde Police. The team operated out of the fictional John Street police station, but many cases took them to many parts of Greater Glasgow and beyond. The main character was Detective Chief Inspector Jim Taggart (Mark McManus), a tough and experienced detective who had worked his way up through the ranks. Taggart’s sidekick was Detective Sergeant Peter Livingstone (Neil Duncan), who represented the new breed of more enlightened cops, which frequently led to clashes with Taggart.

Longtime journeyman scribe, Peter Cave (The New Avengers, etc.) contributed five Taggart tie-in books. I’m fairly certain the last four were novelizations of the show’s scripts, but the first may have been an original. I have no doubt David Spenser will know for sure. TAGGART NOVELS BY PETER CAVE

TAGGART: MURDER IN SEASON Glamorous opera singer, Eleanor Samson, returns to sing with Scottish Opera. While in Glasgow, she hopes to bring about a reconciliation with her estranged husband, John. She is furious to discover that there is a new woman in John's life, blonde ex-secretary, Kirsty King. When Kirsty's body is found in the burnt-out shell of John's boat, Eleanor Samson is the prime suspect...Jim Taggart, tough Glasgow detective, and his smooth young assistant, Peter Livingstone, fall out over the case. Livingstone believes Eleanor is guilty, Taggart cannot believe that a woman like Eleanor could be a murderess. Is Taggart allowing his judgement to be clouded by Eleanor's fame and beauty?

TAGGART: MURDER IN SEASON Glamorous opera singer, Eleanor Samson, returns to sing with Scottish Opera. While in Glasgow, she hopes to bring about a reconciliation with her estranged husband, John. She is furious to discover that there is a new woman in John's life, blonde ex-secretary, Kirsty King. When Kirsty's body is found in the burnt-out shell of John's boat, Eleanor Samson is the prime suspect...Jim Taggart, tough Glasgow detective, and his smooth young assistant, Peter Livingstone, fall out over the case. Livingstone believes Eleanor is guilty, Taggart cannot believe that a woman like Eleanor could be a murderess. Is Taggart allowing his judgement to be clouded by Eleanor's fame and beauty?  TAGGART: NEST OF VIPERS When two skulls are discovered on the site of a new bypass, Jim Taggart is called in to investigate. Could one be that of a girl who disappeared without trace four years earlier? The case takes a deadly turn after poisonous snakes stolen from a pharmaceutical laboratory are used in a series of macabre murders. Taggart needs all his detective skills as he puzzles over the link between the missing girl and a tangle of corporate intrigue involving the lab's owners.

TAGGART: NEST OF VIPERS When two skulls are discovered on the site of a new bypass, Jim Taggart is called in to investigate. Could one be that of a girl who disappeared without trace four years earlier? The case takes a deadly turn after poisonous snakes stolen from a pharmaceutical laboratory are used in a series of macabre murders. Taggart needs all his detective skills as he puzzles over the link between the missing girl and a tangle of corporate intrigue involving the lab's owners.  TAGGART: GINGERBREAD When 12-year-old Simon witnesses the murder of his father by a caped intruder, Jim Taggart is plunged into another mystery. Simon is convinced his father's death is connected to the mysterious cottage in the woods and decides to investigate. His journey moves from fairytale to nightmare.

TAGGART: GINGERBREAD When 12-year-old Simon witnesses the murder of his father by a caped intruder, Jim Taggart is plunged into another mystery. Simon is convinced his father's death is connected to the mysterious cottage in the woods and decides to investigate. His journey moves from fairytale to nightmare.  TAGGART: FORBIDDEN FRUIT When Cathy and Martin Adams decide to have a baby by donor insemination, Cathy's mother, Joan, blames her son-in-law for the 'unnatural' act. Bitter recriminations follow and Joan's subsequent murder would appear to be a clear-cut case. But all is not as it seems: Taggart discovers that Dr Miller of the fertility clinic has been donating his own sperm and that about 60 couples who attended the clinic are now bringing up a 'Miller' child. More creepy discoveries lead the Taggart team on a terrifying hunt for the killer before he strikes again.

TAGGART: FORBIDDEN FRUIT When Cathy and Martin Adams decide to have a baby by donor insemination, Cathy's mother, Joan, blames her son-in-law for the 'unnatural' act. Bitter recriminations follow and Joan's subsequent murder would appear to be a clear-cut case. But all is not as it seems: Taggart discovers that Dr Miller of the fertility clinic has been donating his own sperm and that about 60 couples who attended the clinic are now bringing up a 'Miller' child. More creepy discoveries lead the Taggart team on a terrifying hunt for the killer before he strikes again.  TAGGART: FATAL INHERITANCE When Dr Janet Napier, owner of the Napier Health Farm, on trial for murdering her husband's mistress, is given a 'not-proven' verdict, Taggart is ordered to take a rest. Being Taggart, he promptly books in at the Napier Health Farm. Dr Napier cannot be tried again – but there may be more to discover. Taggart is right. Within days of his arrival, members of Dr Napier's family begin to be murdered by a killer who seems to have a deadly grudge. Does the clue lie in her past, when she destroyed the lives of a family by giving a young girl an accidental overdose of insulin? Taggart's enforced rest at the health farm puts him in just the right place to unearth the killer.

TAGGART: FATAL INHERITANCE When Dr Janet Napier, owner of the Napier Health Farm, on trial for murdering her husband's mistress, is given a 'not-proven' verdict, Taggart is ordered to take a rest. Being Taggart, he promptly books in at the Napier Health Farm. Dr Napier cannot be tried again – but there may be more to discover. Taggart is right. Within days of his arrival, members of Dr Napier's family begin to be murdered by a killer who seems to have a deadly grudge. Does the clue lie in her past, when she destroyed the lives of a family by giving a young girl an accidental overdose of insulin? Taggart's enforced rest at the health farm puts him in just the right place to unearth the killer.

Published on September 18, 2019 18:58

FORGOTTEN TV WESTERNS—THE LAZARUS MAN

FORGOTTEN TV WESTERNS THE LAZARUS MAN

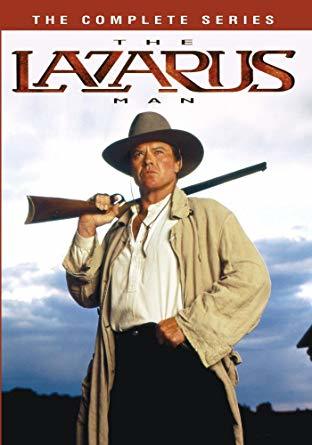

FORGOTTEN TV WESTERNS THE LAZARUS MANSomething has happened to me which I do not understand. All I know for certain is I am alive. How I got here? Who I am? I do not know, but I must've seen or done something, something terrible to be buried alive, to be left for dead. I can remember nothing of my life, my friends or my enemies, but the key to my identity lies somewhere out there. I will search until I find the man I was...and hope to be again.

In the fall of 1865, shortly after the end of the Civil War, an amnesiac claws his way out of a shallow grave outside the town of San Sebastian, Texas. He is wearing a Confederate uniform and carrying a U.S. Army revolver. His one haunted memory is of being attacked by a man wearing a derby. Taking the name Lazarus—after the man Jesus resurrected from the dead—he sets out to discover his true identity and the reason why he was buried alive. Along the he runs into people who still want to kill him, and begins to regain fragments of memory about the night President Lincoln was killed—and the possibility he was in on the plot.

In the fall of 1865, shortly after the end of the Civil War, an amnesiac claws his way out of a shallow grave outside the town of San Sebastian, Texas. He is wearing a Confederate uniform and carrying a U.S. Army revolver. His one haunted memory is of being attacked by a man wearing a derby. Taking the name Lazarus—after the man Jesus resurrected from the dead—he sets out to discover his true identity and the reason why he was buried alive. Along the he runs into people who still want to kill him, and begins to regain fragments of memory about the night President Lincoln was killed—and the possibility he was in on the plot. Near the end of the series, Lazarus is revealed to be James Cathcart, a captain in the US Army and a member of President Abraham Lincoln's personal bodyguard detail. The memories plaguing are from the night of April 14, 1865, when Lincoln was shot at Ford's Theatre. Cathcart, realized the President was in danger and ran to stop the assassin. However, he was attacked from behind by his superior, the treasonous Major Talley, who wanted to see Lincoln dead.

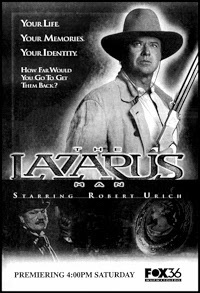

Near the end of the series, Lazarus is revealed to be James Cathcart, a captain in the US Army and a member of President Abraham Lincoln's personal bodyguard detail. The memories plaguing are from the night of April 14, 1865, when Lincoln was shot at Ford's Theatre. Cathcart, realized the President was in danger and ran to stop the assassin. However, he was attacked from behind by his superior, the treasonous Major Talley, who wanted to see Lincoln dead. Starring the eminently likeable Robert Urich, the first season of The Lazarus Man ranked high enough in the ratings for TNT to order a second season. Urich was a veteran of numerous movies and TV series, including starring in the private eye series Spenser based on the bestselling novels by Robert B. Parker. He was also a recipient of a Golden Boot Award for his work in Western television series and films.

Starring the eminently likeable Robert Urich, the first season of The Lazarus Man ranked high enough in the ratings for TNT to order a second season. Urich was a veteran of numerous movies and TV series, including starring in the private eye series Spenser based on the bestselling novels by Robert B. Parker. He was also a recipient of a Golden Boot Award for his work in Western television series and films. In late 1996, before filming resumed for season two, Urich was diagnosed with synovial cell sarcoma, a rare form of cancer. Despite having TNT’s order for the second season in hand, Castle Rock Entertainment (the show’s production company) decided to not to proceed and refused to pay Urich the $1.47 million he was due for the second season. Urich sued for breach of contract, stating he was indeed undergoing cancer treatments, but never informed Castle Rock he would be unable to fulfill his performance contract.

In late 1996, before filming resumed for season two, Urich was diagnosed with synovial cell sarcoma, a rare form of cancer. Despite having TNT’s order for the second season in hand, Castle Rock Entertainment (the show’s production company) decided to not to proceed and refused to pay Urich the $1.47 million he was due for the second season. Urich sued for breach of contract, stating he was indeed undergoing cancer treatments, but never informed Castle Rock he would be unable to fulfill his performance contract. Urich persisted in receiving treatment for his illness while working to raise money for cancer research. In 1998, he was declared cancer and returned to TV in the UPN series, Love Boat: The Next Wave. In 2000, he made his Broadway debut as Billy Flynn in the musical Chicago. His last role was in the NBC sitcom Emeril in 2001, as in the autumn of that year, his cancer returned. He died at age 55. The Lazarus Man had a lot of potential before it was given short shrift by Castle Rock. There was also the interesting parallel of Urich’s own resurrection from his first cancer diagnosis as he truly carried the story of a man raised from the dead on his own shoulders and charisma.

Urich persisted in receiving treatment for his illness while working to raise money for cancer research. In 1998, he was declared cancer and returned to TV in the UPN series, Love Boat: The Next Wave. In 2000, he made his Broadway debut as Billy Flynn in the musical Chicago. His last role was in the NBC sitcom Emeril in 2001, as in the autumn of that year, his cancer returned. He died at age 55. The Lazarus Man had a lot of potential before it was given short shrift by Castle Rock. There was also the interesting parallel of Urich’s own resurrection from his first cancer diagnosis as he truly carried the story of a man raised from the dead on his own shoulders and charisma.In February, 2018, The Lazarus Man: The Complete Series was released on DVD via the Warner Archive Collection.

Published on September 18, 2019 06:33

September 17, 2019

FORGOTTEN TV WESTERNS—SHENANDOAH

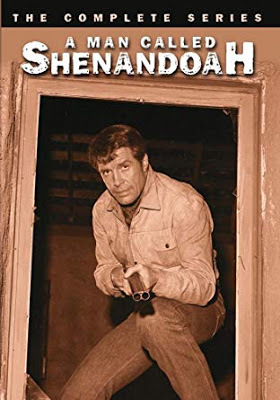

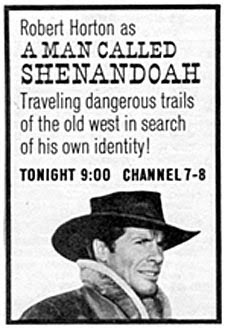

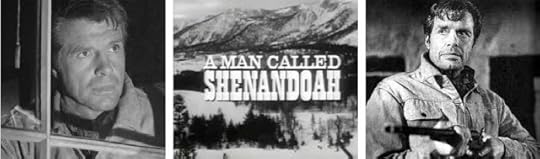

FORGOTTEN TV WESTERNSA MAN CALLED SHENANDOAHAn exceptional thirty minute TV Western, the thirty four episodes of A Man Called Shenandoah graced the network schedule between September 1965 and May 1966. Shenandoah was a sophisticated adult-skewing Western. Featuring tight scripts full of dramatic twists, the show consistently chose cerebral plotlines over simple action.

FORGOTTEN TV WESTERNSA MAN CALLED SHENANDOAHAn exceptional thirty minute TV Western, the thirty four episodes of A Man Called Shenandoah graced the network schedule between September 1965 and May 1966. Shenandoah was a sophisticated adult-skewing Western. Featuring tight scripts full of dramatic twists, the show consistently chose cerebral plotlines over simple action.  Robert Horton plays a gunfighter shot by an old nemesis (Richard Devon) and left for dead, half-naked, on the trail. Thinking there might be a reward, the two saddle bums who discover him drag him to the nearest small town. There, the would-be Samaritansare disappointed when no one knows who he is, nor is his face on any wanted posters. He is nursed back to health, but when he recovers consciousness, he too has no memory of his name, his past, or who shot him.

Robert Horton plays a gunfighter shot by an old nemesis (Richard Devon) and left for dead, half-naked, on the trail. Thinking there might be a reward, the two saddle bums who discover him drag him to the nearest small town. There, the would-be Samaritansare disappointed when no one knows who he is, nor is his face on any wanted posters. He is nursed back to health, but when he recovers consciousness, he too has no memory of his name, his past, or who shot him.  Diagnosed with amnesia by the town doctor, he takes the name Shenandoah before being forced into a gunfight and killing the one man who might have told him who he is. With trouble brewing, Shenandoah leaves the town to roam the West in search of clues to his identity. Along the way, he learns he was a Union officer during the Civil War, and might have been married. In the final episode, Shenandoah has to settle for being told, "It's not always important who you are, but it's always important what you are."

Diagnosed with amnesia by the town doctor, he takes the name Shenandoah before being forced into a gunfight and killing the one man who might have told him who he is. With trouble brewing, Shenandoah leaves the town to roam the West in search of clues to his identity. Along the way, he learns he was a Union officer during the Civil War, and might have been married. In the final episode, Shenandoah has to settle for being told, "It's not always important who you are, but it's always important what you are." Robert Horton previously co-starred on Wagon Train with Ward Bond from 1957 to 1962. When Wagon Train ended, Horton didn’t want to do another Western and initially turned down A Man Called Shenandoah. After a stint in New York doing theater, Horton bumped into the show’s creator E. Jack Neuman, who had previously written scripts for Horton. At Neuman’s urging, Horton reconsidered and signed on.

Robert Horton previously co-starred on Wagon Train with Ward Bond from 1957 to 1962. When Wagon Train ended, Horton didn’t want to do another Western and initially turned down A Man Called Shenandoah. After a stint in New York doing theater, Horton bumped into the show’s creator E. Jack Neuman, who had previously written scripts for Horton. At Neuman’s urging, Horton reconsidered and signed on.  E. Jack Neuman had been involved with many Western TV shows before creating A Man Called Shenandoah. Neuman’s co-producer was William M. Fennelly, who had produced an earlier excellent Western with the same high standards and attention to detail—Trackdown, starring Robert Culp. Unfortunately, viewers used to traditional shoot-em-up Westerns didn’t know what to make of Shenandoah, quickly developing their own version of amnesia and forgetting to watch.

E. Jack Neuman had been involved with many Western TV shows before creating A Man Called Shenandoah. Neuman’s co-producer was William M. Fennelly, who had produced an earlier excellent Western with the same high standards and attention to detail—Trackdown, starring Robert Culp. Unfortunately, viewers used to traditional shoot-em-up Westerns didn’t know what to make of Shenandoah, quickly developing their own version of amnesia and forgetting to watch.  The show was cancelled after two seasons, but I recently watched it on DVD, and found it fascinating. Amnesia was a traditional TV trope in the ‘60s and ‘70s, my favorite example being Coronet Bluestarring Frank Converse. This cliché didn’t matter when it came to Shenandoah as the episodes are so sharply written, directed, and acted. They have an edge, a silent stiletto of social commentary transcending their era.

The show was cancelled after two seasons, but I recently watched it on DVD, and found it fascinating. Amnesia was a traditional TV trope in the ‘60s and ‘70s, my favorite example being Coronet Bluestarring Frank Converse. This cliché didn’t matter when it came to Shenandoah as the episodes are so sharply written, directed, and acted. They have an edge, a silent stiletto of social commentary transcending their era. The stories are as relevant today as when they were filmed. The early episodes of Gunsmoke have much the same impact, as did other early Westerns, but eventually societal censors began to soften the edges of the shows so as not to offend advertisers. The result was generic Pablum for the masses who didn’t want to think about hard problems. The TV Western, like the West itself, would have been better left wild.

The stories are as relevant today as when they were filmed. The early episodes of Gunsmoke have much the same impact, as did other early Westerns, but eventually societal censors began to soften the edges of the shows so as not to offend advertisers. The result was generic Pablum for the masses who didn’t want to think about hard problems. The TV Western, like the West itself, would have been better left wild. On Wagon Train, Horton’s character rode a big, beautiful blanket appaloosa. After several episodes of A Man Called Shenandoah, the same horse became his mount again for the rest of the show’s run. For the show’s theme song, Horton, who had a strong background in musical theatre, re-worked the lyrics to the traditional American folk tune Oh Shenandoah.

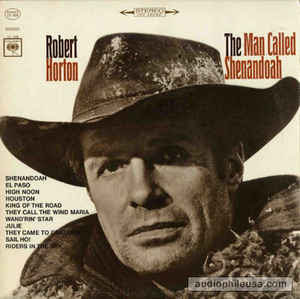

On Wagon Train, Horton’s character rode a big, beautiful blanket appaloosa. After several episodes of A Man Called Shenandoah, the same horse became his mount again for the rest of the show’s run. For the show’s theme song, Horton, who had a strong background in musical theatre, re-worked the lyrics to the traditional American folk tune Oh Shenandoah. In 1967, Columbia Records released an album by Horton of Western standards, including his reworking of Oh, Shenandoah. The other songs on the album included High Noon, Riders In The Sky, King Of The Road, Wand'rin' Star, They Came To Cordura, They Call The Wind Maria, Houston, and El Paso.

Published on September 17, 2019 06:19

September 16, 2019

HAVE GUN WON'T TRAVEL

Published on September 16, 2019 06:32

WILD WEST COMIC ROUNDUP

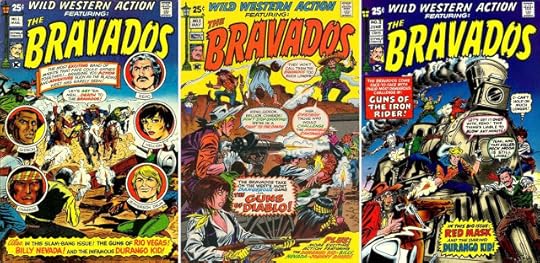

WILD WEST COMICSROUNDUPFounded by Sol Brodsky and Isreal Wadlman, Skywald Publications may be best remembered for their low-budget, brilliantly trashy, black and white horror magazines. In 1971, they branched out by issuing a number of four-color comic titles. While none of the titles lasted more than three issues, there were several intriguing Western specific titles deserving of longer runs.

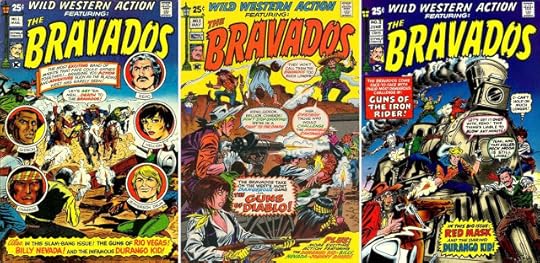

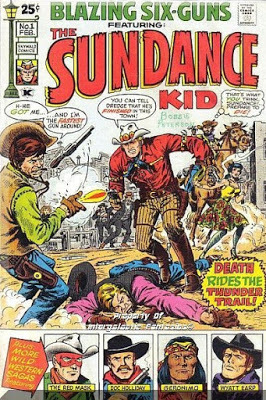

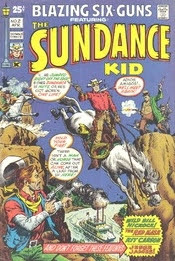

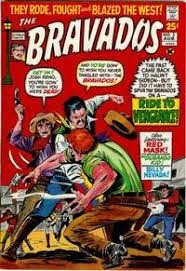

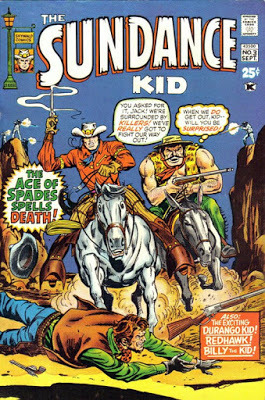

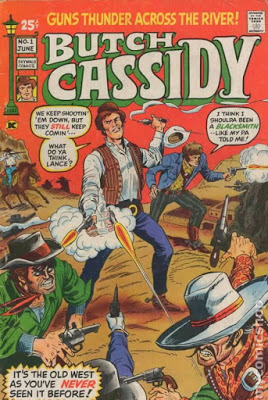

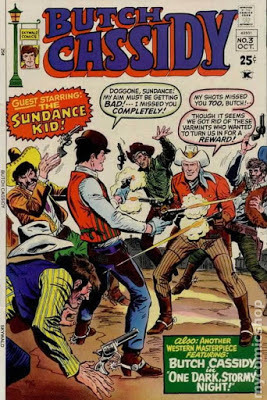

WILD WEST COMICSROUNDUPFounded by Sol Brodsky and Isreal Wadlman, Skywald Publications may be best remembered for their low-budget, brilliantly trashy, black and white horror magazines. In 1971, they branched out by issuing a number of four-color comic titles. While none of the titles lasted more than three issues, there were several intriguing Western specific titles deserving of longer runs. The Bravados, Blazing Six-Guns, Wild Western Action, The Sundance Kid, Butch Cassidy...all the these titles were a mix of new material and reprints, including two issues of The Sundance Kid, which contained Jack Kirby Western tales published in Bullseye.

The Bravados, Blazing Six-Guns, Wild Western Action, The Sundance Kid, Butch Cassidy...all the these titles were a mix of new material and reprints, including two issues of The Sundance Kid, which contained Jack Kirby Western tales published in Bullseye. Attempting to capitalize on the popularity of the movies like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Professionals, The Magnificent Seven, and the rising regard for the Spaghetti Westerns, the new stories were written by Len Wein or Gary Friedrich, and the artwork was provided by Syd Shores, Tom Sutton, and Dick Ayers—all moonlighting from their regular comic gigs. The equal to almost all the other Western comics being published, the covers and, indeed, the stories in all of Skywald’s Western comics make them eminently collectible.

Attempting to capitalize on the popularity of the movies like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Professionals, The Magnificent Seven, and the rising regard for the Spaghetti Westerns, the new stories were written by Len Wein or Gary Friedrich, and the artwork was provided by Syd Shores, Tom Sutton, and Dick Ayers—all moonlighting from their regular comic gigs. The equal to almost all the other Western comics being published, the covers and, indeed, the stories in all of Skywald’s Western comics make them eminently collectible.THE BRAVADOS

The Bravados was the featured story in the three issues of Wild Western Action before getting a one-shot of their own, and then riding off into the comic book sunset. A gang of disparate misfits, The Bravadoswere bound by a thirst for vengeance, but fought together for justice—which would have made a great tag line. It didn’t matter the characters were little more than Western clichés, they were exactly right to ramrod this type of storyline—Reno was the tortured leader; Gideon the angry black cowboy; with a name to give today’s PC police conniptions, Injun Charade was naturally a mute; Drum, the hell-on-wheels good ol' boy had to be included; and the tough, but sexy Hellion was there to keep us reading. With the way they constantly bickered and sniped at each other, The Bravados were a Wild West version of any number of super-teams.

The Bravados was the featured story in the three issues of Wild Western Action before getting a one-shot of their own, and then riding off into the comic book sunset. A gang of disparate misfits, The Bravadoswere bound by a thirst for vengeance, but fought together for justice—which would have made a great tag line. It didn’t matter the characters were little more than Western clichés, they were exactly right to ramrod this type of storyline—Reno was the tortured leader; Gideon the angry black cowboy; with a name to give today’s PC police conniptions, Injun Charade was naturally a mute; Drum, the hell-on-wheels good ol' boy had to be included; and the tough, but sexy Hellion was there to keep us reading. With the way they constantly bickered and sniped at each other, The Bravados were a Wild West version of any number of super-teams. THE SUNDANCE KID

Not at all like the character from the movies, Skywald’s version of The Sundance Kid headlined the two issues of Blazing Six-Guns before getting a three issue run of his own. The Sundance Kid owed enough of his characterization to Kid Colt and Rawhide Kid to be considered kin.

Not at all like the character from the movies, Skywald’s version of The Sundance Kid headlined the two issues of Blazing Six-Guns before getting a three issue run of his own. The Sundance Kid owed enough of his characterization to Kid Colt and Rawhide Kid to be considered kin.

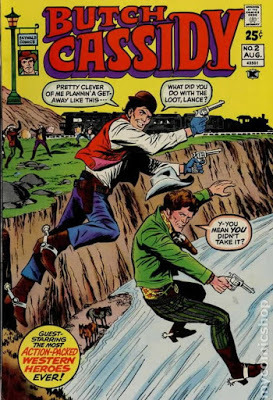

BUTCH CASSIDY

Skywald apparently felt Butch Cassidy was tough enough to handle a series of his own without a need to be given a test run in either Blazing Six-Guns or Wild Western Action, Skywald’s Western anthology comics. While Butch and Sundance never headlined together (they were both given new sidekicks/partners in their separate series), The Sundance Kid did put in an appearance in the third (and final) issue of Butch Cassidy.

Skywald apparently felt Butch Cassidy was tough enough to handle a series of his own without a need to be given a test run in either Blazing Six-Guns or Wild Western Action, Skywald’s Western anthology comics. While Butch and Sundance never headlined together (they were both given new sidekicks/partners in their separate series), The Sundance Kid did put in an appearance in the third (and final) issue of Butch Cassidy. BLAZING SIX-GUNS

Supporting The Sundance Kid in the Blazing Six-Guns comic anthology were Doc Holiday, Geronimo, Wyatt Earp, and The Red Mask (otherwise known as The Crimson Cavalier, and who should have had a series of his own).

WILD WESTERN ACTION

WILD WESTERN ACTIONThe backup features to The Bravados in Wild Western Action included tales spotlighting Rio Vegas, Billy Nevada, and The Durango Kid.

Published on September 16, 2019 06:03

September 15, 2019

FORGOTTEN TV WESTERNS—GUNSLINGER

FORGOTTEN TV WESTERNSGUNSLINGER

FORGOTTEN TV WESTERNSGUNSLINGER

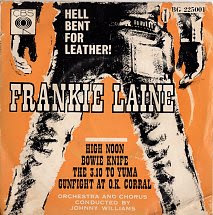

Gunslinger, Gunslinger where do you ride, what do you fight for today? When folks need a hand you’re on their side. Gunslinger ride away. You let someone else be the first one to draw, on your speed you depend. And there are times when your gun’s the only law, fighting to help a friend. Gunslinger, will you return or meet your end. Gunslinger ride on, Gunslinger ride away.

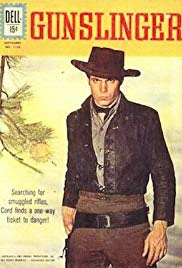

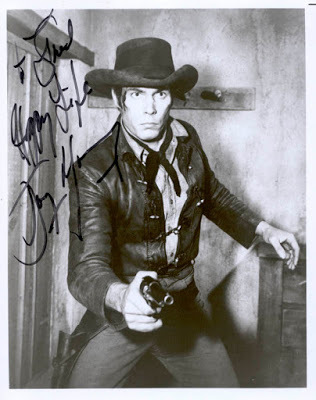

The above theme sung by The Voice of the West, Frankie Laine, introduced the very short-lived TV Western, Gunslinger.A midseason replacement for Dick Powell's Zane Grey Theater, Gunslingerlasted only twelve episodes, airing on CBS Thursday nights at 9 p.m. between February and May 1961. Despite Gunslinger’sshort run, the dark and brooding presence of the loner known only as Cord (Tony Young) proved extremely popular with female viewers. Many a juvenile, and a few middle-aged hearts were broken when show unceremoniously disappeared from the network schedule.

The above theme sung by The Voice of the West, Frankie Laine, introduced the very short-lived TV Western, Gunslinger.A midseason replacement for Dick Powell's Zane Grey Theater, Gunslingerlasted only twelve episodes, airing on CBS Thursday nights at 9 p.m. between February and May 1961. Despite Gunslinger’sshort run, the dark and brooding presence of the loner known only as Cord (Tony Young) proved extremely popular with female viewers. Many a juvenile, and a few middle-aged hearts were broken when show unceremoniously disappeared from the network schedule. The show’s premise was intriguing for its time. The young gunfighter named Cord has a dangerous reputation, which makes him valuable to army garrison commander Captain Zachary Wingate (Preston Foster). Seeing his potential, Wingate recruits Cord to be an undercover troubleshooter for the Cavalry stationed at Fort Scott in Los Flores, NM, during the post-Civil War 1860s. Cord is helped in his assignments by the naïve, but eager Billy Urchin (Dee Pollock) and the Mexican/Irish half-caste Pico McGuire (Charles Gray). Other characters included Sgt. Major John Murdock (John Pickard) and Amby Hollister (Midge Ware) who runs the Fort Scott general store. Director John Ford’s well regarded Cavalry technical advisor, Jack Pennick, was brought in to be the consultant on Gunslinger and also played a small role as a Calvary sergeant.

The show’s premise was intriguing for its time. The young gunfighter named Cord has a dangerous reputation, which makes him valuable to army garrison commander Captain Zachary Wingate (Preston Foster). Seeing his potential, Wingate recruits Cord to be an undercover troubleshooter for the Cavalry stationed at Fort Scott in Los Flores, NM, during the post-Civil War 1860s. Cord is helped in his assignments by the naïve, but eager Billy Urchin (Dee Pollock) and the Mexican/Irish half-caste Pico McGuire (Charles Gray). Other characters included Sgt. Major John Murdock (John Pickard) and Amby Hollister (Midge Ware) who runs the Fort Scott general store. Director John Ford’s well regarded Cavalry technical advisor, Jack Pennick, was brought in to be the consultant on Gunslinger and also played a small role as a Calvary sergeant. The Gunslingerpilot episode was surprisingly effective and broke new ground for Westerns with its dark overtones and conflicting moral underpinnings. The ongoing discovery of atrocities committed during the Civil War remain both shocking and shaming to a nation trying to reunite. The concept of war crimes—prosecution individuals for barbaric actions committed during the conflict—is an unexplored political and penal minefield. When Captain Wingate assigns Cord to capture a Confederate army doctor who performed medical experiments on the Union POWs in the infamous Andersonville prison camp, a gripping social tableau comes into play.

The Gunslingerpilot episode was surprisingly effective and broke new ground for Westerns with its dark overtones and conflicting moral underpinnings. The ongoing discovery of atrocities committed during the Civil War remain both shocking and shaming to a nation trying to reunite. The concept of war crimes—prosecution individuals for barbaric actions committed during the conflict—is an unexplored political and penal minefield. When Captain Wingate assigns Cord to capture a Confederate army doctor who performed medical experiments on the Union POWs in the infamous Andersonville prison camp, a gripping social tableau comes into play. This was strong stuff verging on noir, which held promise for the show becoming something special. Unfortunately, the network balked expecting a backlash from viewers, and the remaining eleven episodes sunk into the mire of traditional Western tropes—rescuing ranchers' daughters, saving towns from gangs, rounding up bad guys. The only thing left to differentiate the show from any other TV oater was Cord, the dark, brooding, and edgy anti-hero (played to the hilt by Tony Young) who made the ladies tingle in their nether regions.

This was strong stuff verging on noir, which held promise for the show becoming something special. Unfortunately, the network balked expecting a backlash from viewers, and the remaining eleven episodes sunk into the mire of traditional Western tropes—rescuing ranchers' daughters, saving towns from gangs, rounding up bad guys. The only thing left to differentiate the show from any other TV oater was Cord, the dark, brooding, and edgy anti-hero (played to the hilt by Tony Young) who made the ladies tingle in their nether regions. CBS network executives also made other egregious decisions. Not wanting to waste film, CBS insisted the actor’s screen tests be inserted into the episodes without regard to plot or storytelling considerations. A fort was built to use as a set, but beyond the first episode there had been no further scripts written , but CBS insisted on getting the show on the air in less than a month. There were occasions when three days of shooting had been completed on an episode, but nobody had any idea how the story was going to be resolved. At one point the writers, actors and directors would sit together on the set and figure out the ending together.

CBS network executives also made other egregious decisions. Not wanting to waste film, CBS insisted the actor’s screen tests be inserted into the episodes without regard to plot or storytelling considerations. A fort was built to use as a set, but beyond the first episode there had been no further scripts written , but CBS insisted on getting the show on the air in less than a month. There were occasions when three days of shooting had been completed on an episode, but nobody had any idea how the story was going to be resolved. At one point the writers, actors and directors would sit together on the set and figure out the ending together. In an interview on the Western Clippings website, Gunslinger’s Tony Young states—I got the role in Gunslinger because I tested for another series, Malibu Run. At the same time, I was asked to walk across the hall and read a speech from Rawhide, wherein Gil Favor roasts Rowdy Yates for something he did. Charles Marquis Warren, who at that time was producing Rawhide for TV and had the responsibility of putting this little interesting western in black and white on the air in 30 days, said, ‘I want him!’ And the other guys said, ‘we want him for Malibu Run.’ Warren said, ‘No, I want him for Cord!’ And he got me. I was 23 years old—thank God for Preston Foster, he was terrific. Really kind to me—patted me on the head when I needed it. At that time I was very green and about as ready to do the lead in a series as the man in the moon.

In an interview on the Western Clippings website, Gunslinger’s Tony Young states—I got the role in Gunslinger because I tested for another series, Malibu Run. At the same time, I was asked to walk across the hall and read a speech from Rawhide, wherein Gil Favor roasts Rowdy Yates for something he did. Charles Marquis Warren, who at that time was producing Rawhide for TV and had the responsibility of putting this little interesting western in black and white on the air in 30 days, said, ‘I want him!’ And the other guys said, ‘we want him for Malibu Run.’ Warren said, ‘No, I want him for Cord!’ And he got me. I was 23 years old—thank God for Preston Foster, he was terrific. Really kind to me—patted me on the head when I needed it. At that time I was very green and about as ready to do the lead in a series as the man in the moon.  We worked 14-16 hours a day to meet our air dates. We were a mid-season replacement and were behind in production, so they had to re-run several episodes within weeks of their original airing. Everyone worked hard and all my co-stars, Charles Gray, Dee Pollock, John Pickard, pitched in to get it done. We had fun working together and there were no egos among us.

We worked 14-16 hours a day to meet our air dates. We were a mid-season replacement and were behind in production, so they had to re-run several episodes within weeks of their original airing. Everyone worked hard and all my co-stars, Charles Gray, Dee Pollock, John Pickard, pitched in to get it done. We had fun working together and there were no egos among us. Gunslinger would unfortunately become the only show produced by Charles Marquis Warren that didn’t become successful. The show has developed something of a cult status—mostly due to the performance of Tony Young as Cord. While four of the show’s episodes can be found on DVD, the other episodes have ridden off into the sunset never to be viewed again.

GUNSLINGER EPISODE GUIDE The Border IncidentThe Hostage FortAppointment in CascabelThe ZoneRampageThe RecruitRoad of the DeadGolden CircleThe DiehardsJohnny SergeantThe Death of Yellow SingerThe New Savannah Story

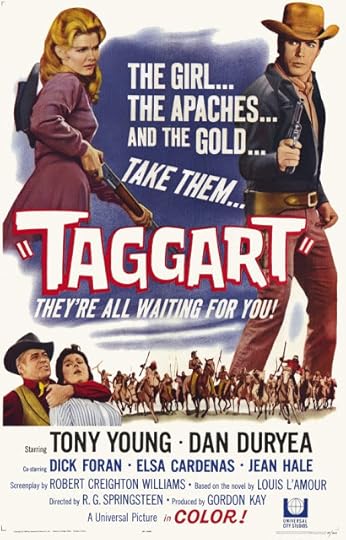

After Gunslinger, Tony Young went on to star in Taggart—a big screen Western opposite Dan Duryea.

Published on September 15, 2019 22:42

September 14, 2019

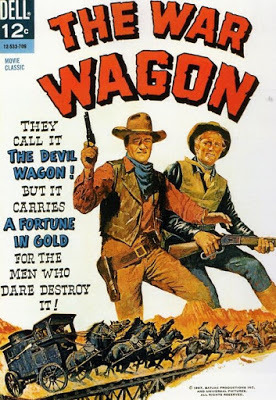

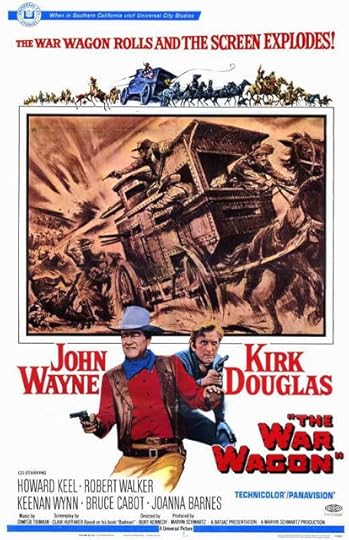

BADMAN/THE WAR WAGON

BADMAN/THE WAR WAGON

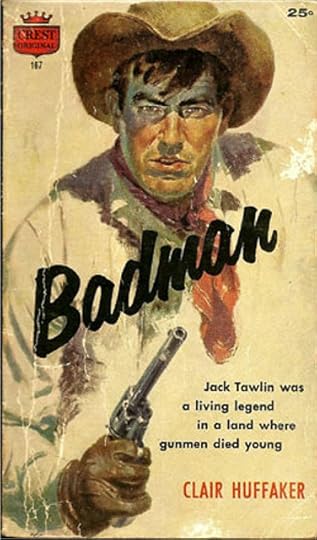

BADMAN/THE WAR WAGON After a stint in Yuma Prison in Arizona, the Badmanof the title, Jack ‘Taw’ Tawlin, returns home to Pawnee Fork, South Dakota, to visit his wild younger brother, Jess. The sheriff and citizens are fearful of Taw’s violent reputation for gunplay and brawling. Reluctantly, as he does not want to return to prison, he agrees to help Jess and his partners rob Old Ironsides—a steel-reinforced stagecoach transporting $300,000 worth of gold dust. What follows is a Western version of a hardboiled crime novel—in particular one of Richard Stark’s Parker novels in which the heist always goes wrong. Throw in Taw’s attraction to Jess’ mistreated wife and you have an ingenious, tense, bolting stagecoach of a novel.

A veteran of World War II, Badman author Clair Huffaker became one of the most prominent and successful writers of Western novels and screenplays for two decades. During the height of the Western’s popularity, he wrote the screenplay adaptations for five of his twelve novels—Flaming Lance(filmed as Flaming Star), Posse from Hell, Guns of Rio Conchos (filmed as Rio Conchos), Badman (filmed as The War Wagon), Seven Ways from Sundown, and Nobody Loves a Drunken Indian (filmed as Flap)—which starred many big name actors including John Wayne, Kirk Douglas and Elvis Presley. He also wrote other successful Western films, such as 100 Rifles (Raquel Welch/Jim Brown), The Devil’s Backbone (Chuck Connors), The Comancheros (John Wayne), and Chino (Charles Bronson). His other major film credits include Hellfighters(John Wayne), Tarzan and the Valley of Gold (Mike Henry), and more. He was a mainstay writer for the Western TV series Riverboat, The Rifleman, Rawhide, Bonanza, Lawman, Colt .45, Outlaws, Destry, The Virginian and Daniel Boone. He even broke away from Westerns long enough to write an episode of Twelve O’Clock High.

A veteran of World War II, Badman author Clair Huffaker became one of the most prominent and successful writers of Western novels and screenplays for two decades. During the height of the Western’s popularity, he wrote the screenplay adaptations for five of his twelve novels—Flaming Lance(filmed as Flaming Star), Posse from Hell, Guns of Rio Conchos (filmed as Rio Conchos), Badman (filmed as The War Wagon), Seven Ways from Sundown, and Nobody Loves a Drunken Indian (filmed as Flap)—which starred many big name actors including John Wayne, Kirk Douglas and Elvis Presley. He also wrote other successful Western films, such as 100 Rifles (Raquel Welch/Jim Brown), The Devil’s Backbone (Chuck Connors), The Comancheros (John Wayne), and Chino (Charles Bronson). His other major film credits include Hellfighters(John Wayne), Tarzan and the Valley of Gold (Mike Henry), and more. He was a mainstay writer for the Western TV series Riverboat, The Rifleman, Rawhide, Bonanza, Lawman, Colt .45, Outlaws, Destry, The Virginian and Daniel Boone. He even broke away from Westerns long enough to write an episode of Twelve O’Clock High. The original source for Badmanwas Huffaker’s short story Holdup at Stony Flat, published in Ranch Romances. Subsequent editions of Badman carried the title The War Wagon to tie in with the movie, though there was only one edition with artwork from the movie on the cover. No matter the title, Badman packs its lean 128 pages with cracking action and deft plotting—a real deal for the twenty-five cent cover price of the original Crest edition.

The original source for Badmanwas Huffaker’s short story Holdup at Stony Flat, published in Ranch Romances. Subsequent editions of Badman carried the title The War Wagon to tie in with the movie, though there was only one edition with artwork from the movie on the cover. No matter the title, Badman packs its lean 128 pages with cracking action and deft plotting—a real deal for the twenty-five cent cover price of the original Crest edition. For the movie, the war wagon was built mostly of plywood painted to look like iron. To complete the illusion, metal clanging sound effects were added when the war wagon’s doors were open or slammed closed. For many years, at least through the 1980s, the deteriorating remains of the war wagon were displayed in The Boneyard—a collection of old outdoor movie props, which was part of Universal Studios’ Backlot Tour.

For the movie, the war wagon was built mostly of plywood painted to look like iron. To complete the illusion, metal clanging sound effects were added when the war wagon’s doors were open or slammed closed. For many years, at least through the 1980s, the deteriorating remains of the war wagon were displayed in The Boneyard—a collection of old outdoor movie props, which was part of Universal Studios’ Backlot Tour. The opening credits for 1967’s The War Wagon mirrors the book’s first pages as the full 47.5 feet, from the lead horse to the back end, of the war wagon flies across the prairie at top speed, horses frothing at the gallop and a troop of outriders racing behind—amazing. However, the film swiftly diverges in nearly every detail. Huffaker’s prose in the novel is edgy and sincere, but his take on the screenplay is much lighter, fitting well with director Burt Kennedy’s tongue-in-cheek style. In another major change in the film, Kirk Douglas plays a high-class killer named Lomax who is hired to kill Taw (John Wayne). The banter and one-upmanship between Lomax and Taw is priceless. After they simultaneously gun down two hapless henchmen, Lomax comments, Mine hit the ground first. Taw immediately responds, Mine was taller.

The opening credits for 1967’s The War Wagon mirrors the book’s first pages as the full 47.5 feet, from the lead horse to the back end, of the war wagon flies across the prairie at top speed, horses frothing at the gallop and a troop of outriders racing behind—amazing. However, the film swiftly diverges in nearly every detail. Huffaker’s prose in the novel is edgy and sincere, but his take on the screenplay is much lighter, fitting well with director Burt Kennedy’s tongue-in-cheek style. In another major change in the film, Kirk Douglas plays a high-class killer named Lomax who is hired to kill Taw (John Wayne). The banter and one-upmanship between Lomax and Taw is priceless. After they simultaneously gun down two hapless henchmen, Lomax comments, Mine hit the ground first. Taw immediately responds, Mine was taller.

Published on September 14, 2019 23:32

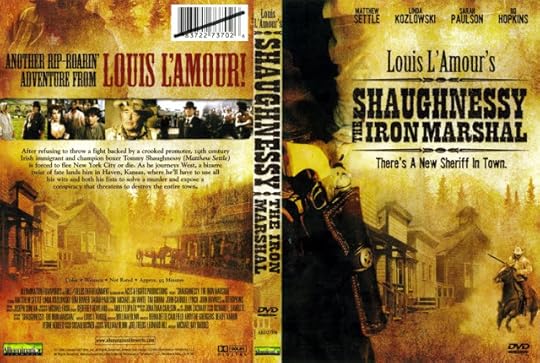

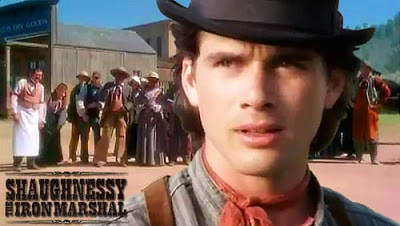

SHAUGHNESSY—THE IRON MARSHAL

SHAUGHNESSY:THE IRON MARSHALAfter picking a copy up in a used bookstore, I read Louis L’Amour’s 1979 novel, The Iron Marshal, for the first time earlier this year. Over the years, I’ve read almost all of L’Amour’s best known works and many of his others, but somehow The Iron Marshal slipped my notice. It was actually a real treat to be able to dive into a top notch, new to me, L’Amour tale—and The Iron Marshal did not disappoint.

SHAUGHNESSY:THE IRON MARSHALAfter picking a copy up in a used bookstore, I read Louis L’Amour’s 1979 novel, The Iron Marshal, for the first time earlier this year. Over the years, I’ve read almost all of L’Amour’s best known works and many of his others, but somehow The Iron Marshal slipped my notice. It was actually a real treat to be able to dive into a top notch, new to me, L’Amour tale—and The Iron Marshal did not disappoint. I mentioned the novel in a post on the very active and knowledgeable Men’s Adventure Paperbacks of the 2oth Century Facebook group, which is my home away from home. The response was immediate as the book was highly rated many in the group who were familiar with it. Other members found themselves intrigued enough to pick up a copy and reported back their agreement with the high praise the book generated in the group.

I mentioned the novel in a post on the very active and knowledgeable Men’s Adventure Paperbacks of the 2oth Century Facebook group, which is my home away from home. The response was immediate as the book was highly rated many in the group who were familiar with it. Other members found themselves intrigued enough to pick up a copy and reported back their agreement with the high praise the book generated in the group. My wife is also a big L’Amour fan, so I downloaded her a copy of the audio book. She listened with rapt attention. Twice I heard her open the garage door and drive in, but didn’t immediately come into the house. When I went to look for her, she was sitting in the car unable to get out until the current chapter she was listening to ended. She raved about the book and couldn’t understand why it hadn’t been made into a movie. I agreed. She even made her own casting selections after disagreeing with my choice of Tom Berenger for the title role.

My wife is also a big L’Amour fan, so I downloaded her a copy of the audio book. She listened with rapt attention. Twice I heard her open the garage door and drive in, but didn’t immediately come into the house. When I went to look for her, she was sitting in the car unable to get out until the current chapter she was listening to ended. She raved about the book and couldn’t understand why it hadn’t been made into a movie. I agreed. She even made her own casting selections after disagreeing with my choice of Tom Berenger for the title role. Imagine my surprise (the more I dig into the history of Westerns and Men’s adventure paperbacks, the more surprises there seem to be) when I came across a listing for a DVD copy of Shaughnessy: The Iron Marshal. I immediately purchased the DVD and began tracking down more information on its origin.

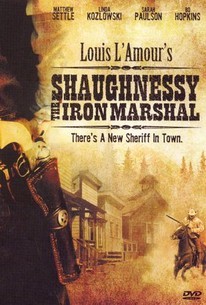

Imagine my surprise (the more I dig into the history of Westerns and Men’s adventure paperbacks, the more surprises there seem to be) when I came across a listing for a DVD copy of Shaughnessy: The Iron Marshal. I immediately purchased the DVD and began tracking down more information on its origin. In 1996, Beau L’Amour took on the role of producer to turn his father’s novel, The Iron Marshal, into a made-for-TV movie. The result was Louis L'Amour's Shaughnessy. Written by the Emmy award winning William Blinn (creator of Starsky and Hutch, among many other films and TV shows), and directed by Michael Rhodes, the movie starred Matthew Settle (in his debut) as Shaughnessy, and featured co-starring roles for Linda Kozlowski, and Michael Jai White.

In 1996, Beau L’Amour took on the role of producer to turn his father’s novel, The Iron Marshal, into a made-for-TV movie. The result was Louis L'Amour's Shaughnessy. Written by the Emmy award winning William Blinn (creator of Starsky and Hutch, among many other films and TV shows), and directed by Michael Rhodes, the movie starred Matthew Settle (in his debut) as Shaughnessy, and featured co-starring roles for Linda Kozlowski, and Michael Jai White. Like many made-for-TV movies of the time, Louis L'Amour's Shaughnessy was clearly designed to act as a pilot for a proposed TV series. However, the pilot did not get picked up by CBS, which left the standalone TV movie riddled with unresolved storylines. If the finished TV movie had run two hours instead of ninety minutes, many of these issues could have been resolved. If this had been done, it would have made for a far more satisfying production and possibly rated as one of the best screen translations of L’Amour’s works. As things remain, viewers are left wanting to turn the DVD over like an old LP looking for part two on the other side.

Like many made-for-TV movies of the time, Louis L'Amour's Shaughnessy was clearly designed to act as a pilot for a proposed TV series. However, the pilot did not get picked up by CBS, which left the standalone TV movie riddled with unresolved storylines. If the finished TV movie had run two hours instead of ninety minutes, many of these issues could have been resolved. If this had been done, it would have made for a far more satisfying production and possibly rated as one of the best screen translations of L’Amour’s works. As things remain, viewers are left wanting to turn the DVD over like an old LP looking for part two on the other side. The plot of the original book was simplified for the movie to focus on young Irish immigrant Tommy Shaughnessy—a champion boxer with a reputation as a ne'er-do-well—who finds himself in the middle of battling Irish gangs in post-Civil War New York. After refusing to throw a fight backed by a crooked promoter, Shaughnessy takes a bullet in the back. Badly injured, he flees New York by hitching a ride in an empty train car like a common hobo.

The plot of the original book was simplified for the movie to focus on young Irish immigrant Tommy Shaughnessy—a champion boxer with a reputation as a ne'er-do-well—who finds himself in the middle of battling Irish gangs in post-Civil War New York. After refusing to throw a fight backed by a crooked promoter, Shaughnessy takes a bullet in the back. Badly injured, he flees New York by hitching a ride in an empty train car like a common hobo.  As he journeys West, a bizarre twist of fate lands him in Haven, Kansas. Further complications ensue—as they do—and he finds himself wearing a marshal’s star while standing between the town and a gang of cattle cowboys fresh off a cattle drive who are riding in to destroy it. As if he doesn’t have enough to deal with, a murder and a deadly conspiracy are also part of what forces him to use all his wits and both of iron fists to stay alive.

As he journeys West, a bizarre twist of fate lands him in Haven, Kansas. Further complications ensue—as they do—and he finds himself wearing a marshal’s star while standing between the town and a gang of cattle cowboys fresh off a cattle drive who are riding in to destroy it. As if he doesn’t have enough to deal with, a murder and a deadly conspiracy are also part of what forces him to use all his wits and both of iron fists to stay alive. Despite its drawbacks, Shaughnessy remains a lighthearted, rip-roaring, and entertaining B-Western. L’Amour fanatics may not like the changes the movie makes to the original novel, but for the rest of us who appreciate L’Amour at a less intense level, it’s worth viewing. Retitled Shaughnessy: The Iron Marshal for DVD, the movie supposedly pops up occasionally on the Western dedicated cable channels—although I have never seen a listing for it. Fortunately, for those interested, an excellent download is readily available on YouTube.

Despite its drawbacks, Shaughnessy remains a lighthearted, rip-roaring, and entertaining B-Western. L’Amour fanatics may not like the changes the movie makes to the original novel, but for the rest of us who appreciate L’Amour at a less intense level, it’s worth viewing. Retitled Shaughnessy: The Iron Marshal for DVD, the movie supposedly pops up occasionally on the Western dedicated cable channels—although I have never seen a listing for it. Fortunately, for those interested, an excellent download is readily available on YouTube.

Published on September 14, 2019 22:59

HOW THE WEST WAS WON

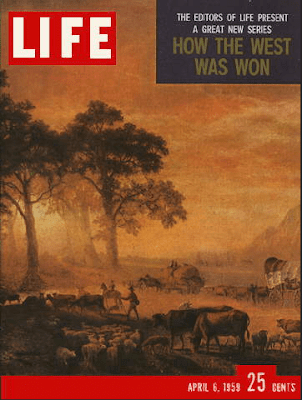

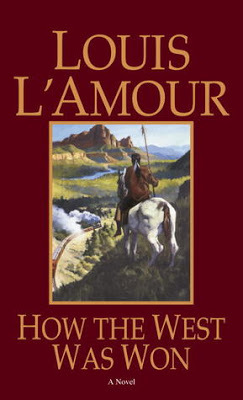

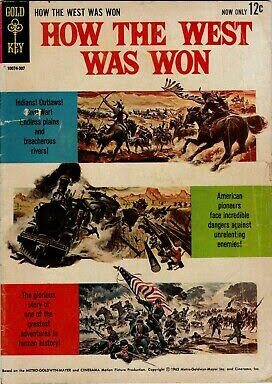

HOW THE WEST WAS WONWhile it is often billed as a novel by Louis L'Amor, the designation is purposely misleading. In reality, How The West Was Won was originally conceived as a series of Life magazine articles published in 1959. Those articles consisted of photos and allegedly true vignettes pertaining to the expansion and settling of the wild west.

HOW THE WEST WAS WONWhile it is often billed as a novel by Louis L'Amor, the designation is purposely misleading. In reality, How The West Was Won was originally conceived as a series of Life magazine articles published in 1959. Those articles consisted of photos and allegedly true vignettes pertaining to the expansion and settling of the wild west. The articles would eventually provide the basis for James R. Webb's screenplay for How The West Was Won. The movie, released in Europe in 1962 and on domestic screens in 1963, was the last of the big screen epic Westerns. Sprawling, multi-generational, and star-studded, the movie was lavishly filmed using the three-strip Cinerama process. Although the picture quality when projected onto curved screens in theaters was stunning, attempts to convert the movie to a smaller screen suffer from the technical shortcomings of the process (in Letterbox, the actor's features are grossly distorted). Despite this technical issue, the film enthralled audiences and snagged three Academy Awards, including Best Screenplay.

The articles would eventually provide the basis for James R. Webb's screenplay for How The West Was Won. The movie, released in Europe in 1962 and on domestic screens in 1963, was the last of the big screen epic Westerns. Sprawling, multi-generational, and star-studded, the movie was lavishly filmed using the three-strip Cinerama process. Although the picture quality when projected onto curved screens in theaters was stunning, attempts to convert the movie to a smaller screen suffer from the technical shortcomings of the process (in Letterbox, the actor's features are grossly distorted). Despite this technical issue, the film enthralled audiences and snagged three Academy Awards, including Best Screenplay.  The film's producers believed they had a potential hit from the beginning . They wanted a novelization of the script commissioned as a promotional tie-in to raise the public awareness of the film. This desire would lead to L'Amour's opportunity to novelize the story—something he had never done before nor would ever do again.* At the time, L'Amour was frustrated with the restrictions being put on him by his publisher. They didn't want to change the successful formula of his traditional paperback Westerns. L'Amour wanted to grow creatively by writing longer, more complex stories, but the publishers stubbornly pushed back.

The film's producers believed they had a potential hit from the beginning . They wanted a novelization of the script commissioned as a promotional tie-in to raise the public awareness of the film. This desire would lead to L'Amour's opportunity to novelize the story—something he had never done before nor would ever do again.* At the time, L'Amour was frustrated with the restrictions being put on him by his publisher. They didn't want to change the successful formula of his traditional paperback Westerns. L'Amour wanted to grow creatively by writing longer, more complex stories, but the publishers stubbornly pushed back. With his son Beau about to be born, L'Amour needed to move out of the adults only apartment where he and his wife were living. Cash was needed, so when his publisher offered him a contract to write the novelization of How The West Was Won, L'Amour saw it as both a financial windfall and an opportunity to expand on what he considered a mundane and lackluster script. He also thought he could do it fast.

With his son Beau about to be born, L'Amour needed to move out of the adults only apartment where he and his wife were living. Cash was needed, so when his publisher offered him a contract to write the novelization of How The West Was Won, L'Amour saw it as both a financial windfall and an opportunity to expand on what he considered a mundane and lackluster script. He also thought he could do it fast. However, How The West Was Won became a millstone around L'Amour's neck. His obsession with portraying the West as it really was came into direct conflict with Hollywood's version of the West as portrayed in the screenplay. There were action scenes (a wagon train trying to outrun marauding Indians while leaden down with a literal tin of supplies and goods), L'Amour saw as ridiculous. Others he knew were physically impossible (crawling from the couplings between train cars to the rails below). And there were relationship connections between western characters that did not and could not exist (mountain men did not live in respectful harmony with most Indian tribes).

However, How The West Was Won became a millstone around L'Amour's neck. His obsession with portraying the West as it really was came into direct conflict with Hollywood's version of the West as portrayed in the screenplay. There were action scenes (a wagon train trying to outrun marauding Indians while leaden down with a literal tin of supplies and goods), L'Amour saw as ridiculous. Others he knew were physically impossible (crawling from the couplings between train cars to the rails below). And there were relationship connections between western characters that did not and could not exist (mountain men did not live in respectful harmony with most Indian tribes). As L'Amour wrote his way around these problems, he was forced time and again to prove his version of the facts to the movie's producers, who frankly didn't care. There were also constant requests for rewrites as the script changed on the fly while filming was underway. L'Amour's irritation with the project grew exponentially with each clash. However, despite its rocky gestation, L'Amour's version of How The West Was Won would become one of the bestselling novelizations of all time.

As L'Amour wrote his way around these problems, he was forced time and again to prove his version of the facts to the movie's producers, who frankly didn't care. There were also constant requests for rewrites as the script changed on the fly while filming was underway. L'Amour's irritation with the project grew exponentially with each clash. However, despite its rocky gestation, L'Amour's version of How The West Was Won would become one of the bestselling novelizations of all time.  The main reason for this was not necessarily because of the rabid love the public developed for the film, but because while L'Amour's efforts remain technically a novelization, the final publication was also much more.

The main reason for this was not necessarily because of the rabid love the public developed for the film, but because while L'Amour's efforts remain technically a novelization, the final publication was also much more. L'Amour succeed against the odds in taking the episodic, uneven, nature of the film and expanded upon every scene (especially in the later chapters of the novelization), imbuing the final product with an epic reality going far beyond the realm of the typical novelization.

Twice as long as any of his previous works, L'Amour's version of How The West Was Won is a true a hybrid—part novelization, part original novel—with a depth of character and story that would easily make the uninformed believe the novelization was actually the source material for the film instead of the other way around. Still in print today and continuing to sell steadily, the success and popularity of the novel version of How The West Was Won has long outlived its celluloid genesis.

Twice as long as any of his previous works, L'Amour's version of How The West Was Won is a true a hybrid—part novelization, part original novel—with a depth of character and story that would easily make the uninformed believe the novelization was actually the source material for the film instead of the other way around. Still in print today and continuing to sell steadily, the success and popularity of the novel version of How The West Was Won has long outlived its celluloid genesis.* While How The West Was Won is L'Amour's only credited novelization, a number of his novels are novelizations of screenplays inspired by his own short stories and film treatments. Hondo is the most (in)famous but Beau L'Amour, in his afterword to the Lost Treasures edition of Kid Rodelo, cites that novel & several others as examples.

Published on September 14, 2019 10:38

September 10, 2019

GUNSMOKE

GUNSMOKE

Commentary via my pal and wordslinger extraordinaire

GUNSMOKE

Commentary via my pal and wordslinger extraordinaire

Mark Ellis

On this date in 1955, what became the gold standard of TV westerns debuted--GUNSMOKE. The show had already been very successful on radio and made an easy transition to TV. The first episode was introduced by John Wayne.

Like STAR TREK a decade later, the GUNSMOKE TV series made icons out of the characters and the actors who played them, particularly James Arness as Matt Dillon.

Unlike a lot of other so-called TV tough guys, James Arness didn't need to posture or swagger to give the impression he was authentic. A wounded combat vet (shot to hell at Anzio), all he had to do was stand there.

I didn't see the half-hour GUNSMOKE episodes until the last ten years when Encore's Western Channel began airing them...for that matter, when the show became an hour long in the early 60s, I don't recall seeing all that many episodes, either.

It either came on too late or my parents thought it was too adult.

GUNSMOKE was definitely adult for the standards of the time...but despite some of the very dark episodes such as "The Cabin", the plot was less important than the very human story of the people caught up in it.

Watching GUNSMOKE now, I'm impressed by the depth of the writing and quality of characterization, as well as the sympathetic and respectful portrayal of Native Americans. Almost always, when an episode dealt with a white man versus Indian conflict, Matt Dillon took the side of the Indians.

In fact, the late Burt Reynolds first came to prominence playing half-Comanche blacksmith Quint Asper for several seasons.

Amanda Blake as hard-edged, independent Kitty Russell was definitely not like any female continuing character in a network TV series at the time.

For the most part, the production values were first-rate, motion-picture quality, especially when the show went to color in 1966.

Just like great music out lives the era in which it was composed, so do great TV series.

Airing until 1975, GUNSMOKE deservedly held the record for the longest running drama in prime time until just recently when it was surpassed by Law & Order...

Published on September 10, 2019 07:43