Paul Bishop's Blog, page 5

October 28, 2019

TONY MASERO WORDS AND PAINTS

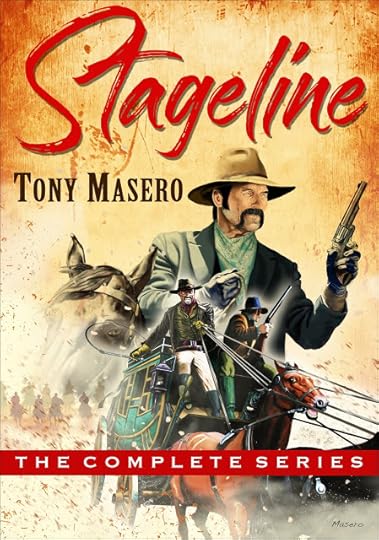

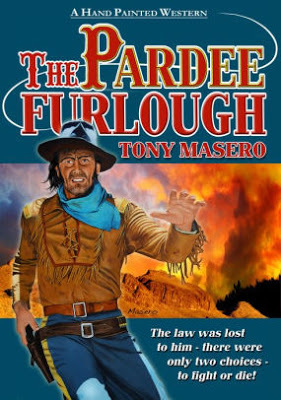

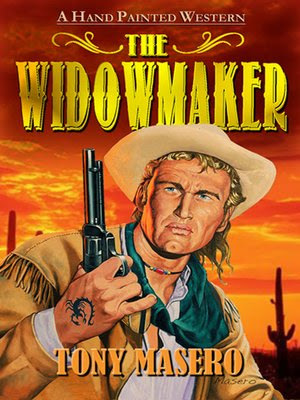

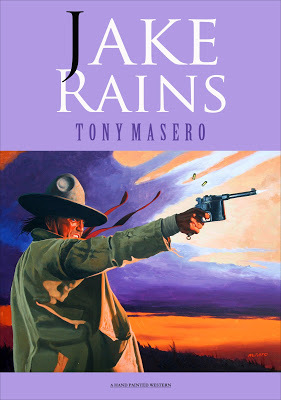

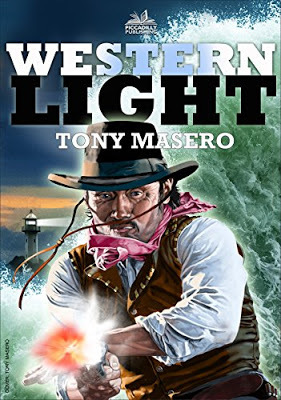

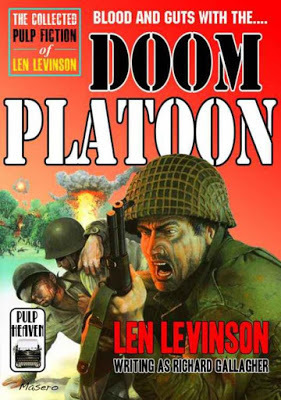

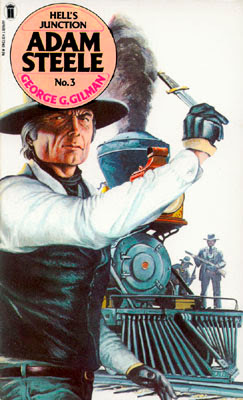

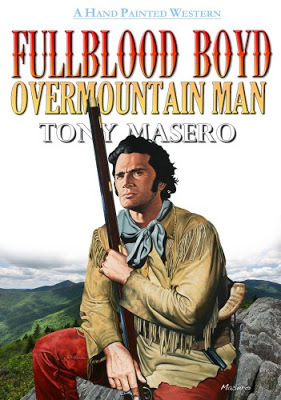

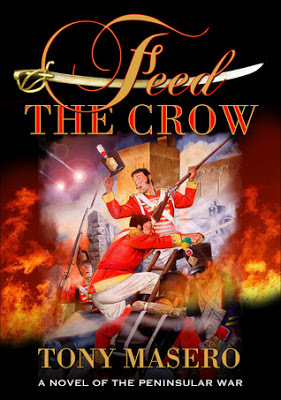

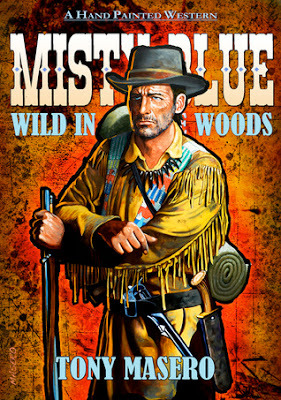

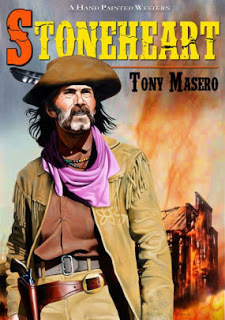

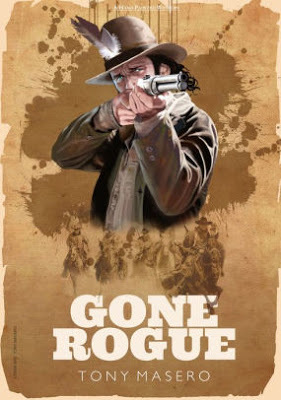

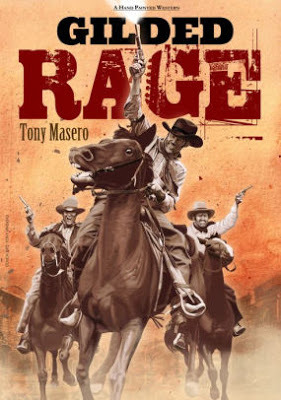

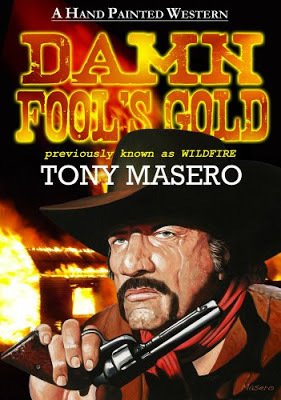

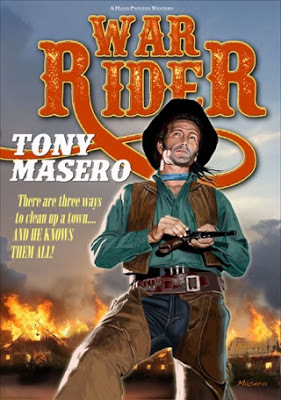

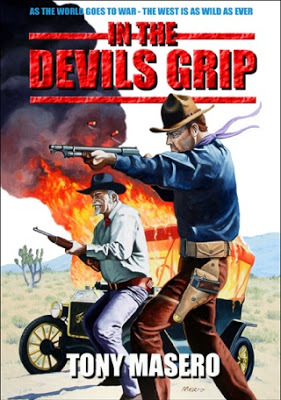

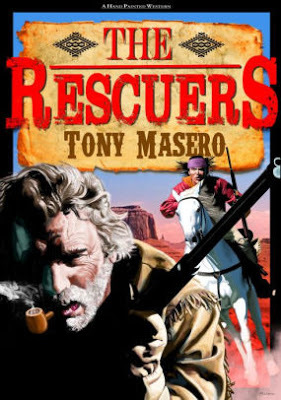

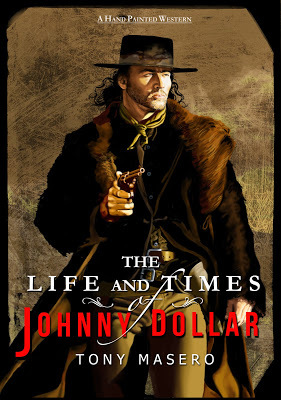

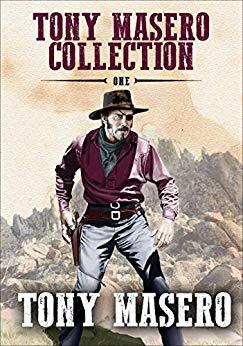

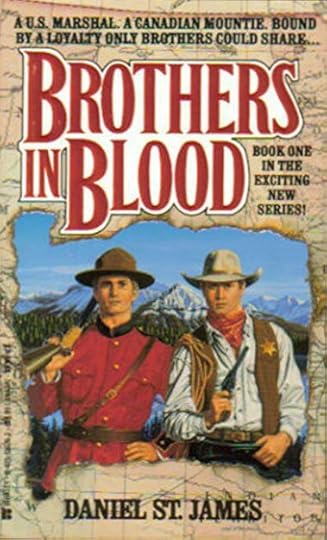

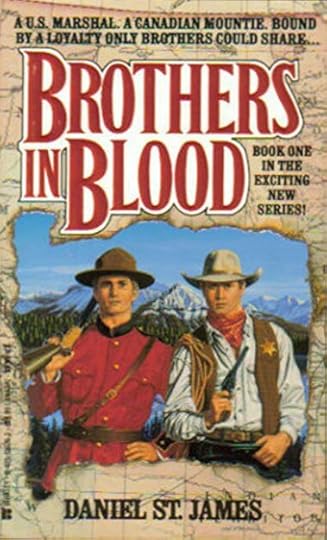

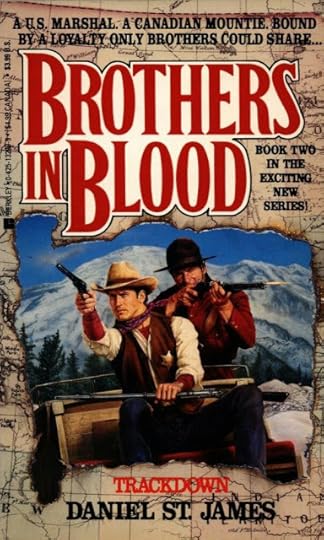

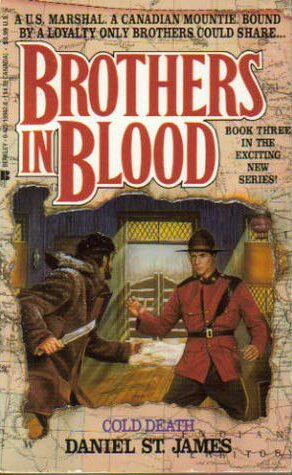

TONY MASERO WORDS AND PAINTS Painted book covers from internationally respected illustrator and author Tony Masero have been in high demand from the 70’s and 80’s through to the present day. A Masero cover immediately stands out because of its bold hand-painted and colorful artwork.

TONY MASERO WORDS AND PAINTS Painted book covers from internationally respected illustrator and author Tony Masero have been in high demand from the 70’s and 80’s through to the present day. A Masero cover immediately stands out because of its bold hand-painted and colorful artwork.  Born in London, Tony attended art school in the UK and then trained as a graphic designer. He segued into full-time illustration when he began receiving commissions from major publishing houses and agencies.

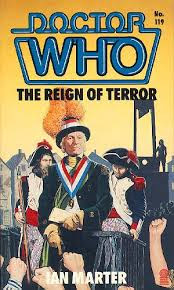

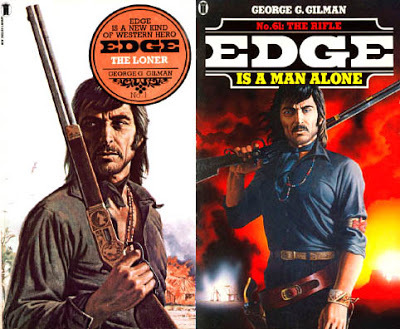

Born in London, Tony attended art school in the UK and then trained as a graphic designer. He segued into full-time illustration when he began receiving commissions from major publishing houses and agencies.  Tony’s illustrations for this period covered a wide field of styles and subject matter, ranging from the popular to the macabre, intriguing and lesser known. From the Sci-Fi fantasies of Dr. Who, to horrifying paperback imagery, the westerns of Edge: The Loner, pulp covers for The Spider, Satan Sleuth,Death Dealer and beyond into the realms of historical fiction and romance.

Tony’s illustrations for this period covered a wide field of styles and subject matter, ranging from the popular to the macabre, intriguing and lesser known. From the Sci-Fi fantasies of Dr. Who, to horrifying paperback imagery, the westerns of Edge: The Loner, pulp covers for The Spider, Satan Sleuth,Death Dealer and beyond into the realms of historical fiction and romance. I’ve long been a fan of his artwork and his Western novels and have been fortunate enough to recently begin corresponding with him and getting to know him better. As a result, Tony was kind enough to allow me to pester him with a series of interview questions...

******

******

What was your personal background leading to your career as an artist? Did you come from a family of creatives?

What was your personal background leading to your career as an artist? Did you come from a family of creatives?

I have my father to thank for that. He was a wood carver who began as a restorer and worked his way up to become a respected master carver in the UK and abroad. His works are mainly of a religious nature and are to be found in many well known London churches—he created the figure of Christ on the cupola above the main altar in St. Paul’s Cathedral during the restoration after Blitz bomb damage, many family coats-of-arms for the College of Arms, The Admiralty as well as many other works around the city and beyond. For those interested: www.gino.masero.co.uk

When did you first start painting? Where did you get your training?

When did you first start painting? Where did you get your training?

I think I was around three years old, at least that’s what they tell me, when my father first put a pencil in my hand—I guess I haven’t stopped since. Subsequently, I went on to train as a graphic designer in art school. It was considered by my parents as a safer career option rather than something as obscure and on the fringe as Illustration.

However, I knew I wanted to Illustrate. So, about halfway through my second year, I attempted to change my course, but sadly I was advised by my rather snobbish headmaster (an Royal Academy watercolorist of some note) that I would never make an illustrator. ‘No never, not a chance, old boy.’ A mark of the times in the UK in those post-war years where nothing was possible and the restrictions of the older generation led us all into the rebellious sixties. That one still burns and I’ve been proving the gentleman wrong ever since—but on the basis of that arbitrary decision I wasted a lot of years struggling in graphics before breaking through into Illustration.

However, I knew I wanted to Illustrate. So, about halfway through my second year, I attempted to change my course, but sadly I was advised by my rather snobbish headmaster (an Royal Academy watercolorist of some note) that I would never make an illustrator. ‘No never, not a chance, old boy.’ A mark of the times in the UK in those post-war years where nothing was possible and the restrictions of the older generation led us all into the rebellious sixties. That one still burns and I’ve been proving the gentleman wrong ever since—but on the basis of that arbitrary decision I wasted a lot of years struggling in graphics before breaking through into Illustration.  Did you always make a living from your art or were there other jobs along the way?

Did you always make a living from your art or were there other jobs along the way?

A great many, mainly of a lowly nature—landscaping, laboring, factory and office work. Later, I worked as a paste-up artist in film poster advertising, then as a designer for various ad agencies, and latterly running a design studio for a print company. In the process, I acquired some knowledge of design and how to use the space on a cover. None of it is was a wasted experience. My time amongst working people was rich and a great source for later representations of tough hardworking guys.

One anecdote: Shift work in the factory, non to midnight one week, then changed around for the next. Exhausting stuff for a meager piece-work pay. Payday meant drinking time. I worked with a big Irishman, full of song and poetry. He would stand on the bar table and sing rebel songs when the drink was on him. He saved me from a knifing one time and took me to meet his older brothers, both solemn souls just back from serving as mercenaries in Biafra. I suspect they served a different army at that time as the only way I was accepted into their company was because of my mother’s Irish origins. All of it grist for the mill when the writing came later.

One anecdote: Shift work in the factory, non to midnight one week, then changed around for the next. Exhausting stuff for a meager piece-work pay. Payday meant drinking time. I worked with a big Irishman, full of song and poetry. He would stand on the bar table and sing rebel songs when the drink was on him. He saved me from a knifing one time and took me to meet his older brothers, both solemn souls just back from serving as mercenaries in Biafra. I suspect they served a different army at that time as the only way I was accepted into their company was because of my mother’s Irish origins. All of it grist for the mill when the writing came later.  When did you start painting book covers. And what were your early assignments?

When did you start painting book covers. And what were your early assignments?

After a while, the designer studio life paled and I quit it all. I made some samples and started hawking them around. In the late sixties/early seventies there were some gracious art directors in the publishing world who would actually meet and interview prospective illustrators. One of them at Pan Books gave me some good advice, which I subsequently took. From the basis of those samples I was accepted and New English Library gave me my first commission—a horror book, The Craft of Terror. My experience grew from there and evolved into getting regular commisions from their art department. It proved to be a great training ground as NEL’s list covered a wide spectrum of pulp fiction, and one never knew what was in the pipeline from one week to the next. Horror, Romance, Adventure, Western—whatever came along one had to turn one’s hand to it.

Was your writing an extension of your painting, or were the two skills developed independently?

Was your writing an extension of your painting, or were the two skills developed independently?

I see little difference between them. To me words are like paint. A subtle shift can be emphasized visually in a character’s demeanor by a highlight that casts a spark of light in the eye. Or lacking visibility, by using the correct term to imply exactly the mood intended in the briefest way possible. Both forms have palettes that create the basis for the complete picture.

Who were your influences both in art and literature?

Who were your influences both in art and literature?

Norman Rockwell, James Bama, Dick Clifton-Dey—too many—there are so many great ones out there. Most profoundly though it was a British comic artist, Frank Hampson, who first starred in my evolution. He drew for the comic Eagle—the first large format bold and colorful comic of my youth—and one of the first artists to use real models as photographic reference in comics. The man was a genius of imagination.

I read widely from a tender age—all of the expected fiction along with classics and philosophy, some of it compulsively. Now it’s mostly historical literature, with Antony Beevor as a favorite. Of modern fiction writers, I greatly admire James Lee Burke who can manage to blend the most lyrical with the most violent in one breath.

Most of your novels have been Westerns, but you've also written in many other genres. What draws you to a story?

Most of your novels have been Westerns, but you've also written in many other genres. What draws you to a story?

Imagination always. Often inspired by a word, a historical note, or a scene in a movie screenplay. Most finds are like a seed in the imagination, which sprout and bloom into a written page. I enjoy History and often read the early writings and journals of ordinary folk, particularly in the Old West. How would I react then becomes the question? Historical research into those times can take one off on many different tacks and into intriguing areas all of which give an air of reality to the writing one is involved in.

Research is very important for me, just as it is in Illustration. How is a saddle made? What would the effect of a .45 caliber bullet make at close range? What distance can a loaded mule cover in a single day? None of these I have experience with and so it must be discovered.

Do you ever start with a painting and write a story based on it?

Do you ever start with a painting and write a story based on it?

Often the two parallel. I’ll begin writing and will be thinking of the cover as I go. The great thing about being in both fields is I can adapt either to suit and change appearance or environment to whichever fits best.

How has your painting and your writing evolved over time?

Writing, being the more latterly, is the most obvious. I had no literary training, and in the beginning it was the old Black Horse publishing company who made me write and re-write my first manuscripts. The work was being honed to suit their particular market, but nevertheless it imposed on me a discipline that stood me well as I progressed. Probably, they were simply trying to get rid of another tiresome amateur. However, as I did when entering Illustration for the first time, I persisted and then persisted again until I received my first copy back in hardcover—Jake Rains—and that felt too good to stop.

Which discipline comes easiest to you, art or writing?

Which discipline comes easiest to you, art or writing?

Obviously, the art. I’ve been at it the longest and a visual way of thinking is now so ingrained that my writing is merely a transposition of the visual images, which play like a movie in my head. Same with the dialogue, which I hope has improved over time and now flows more easily.

You have painted covers for iconic Western series—such as Edge, Sundance, The Searcher, and The Gunsmith to name but a few. You have also done action series covers for such esteemed series as The Sergeant, Dr. Who and many more. How do you creatively approach creating the covers for such high profile series?

You have painted covers for iconic Western series—such as Edge, Sundance, The Searcher, and The Gunsmith to name but a few. You have also done action series covers for such esteemed series as The Sergeant, Dr. Who and many more. How do you creatively approach creating the covers for such high profile series?

The Edge series was a ground-breaker of course, but before that I did the covers for the James Gunn series of Westerns, which may have inspired the publisher’s to let me have a try with Edge. I was following in the footsteps of the great Clifton-Dey who started illustrating the series, but after their initial success I was allowed pretty much to go my own way until the series finished. Basically Edge was a simple design format—a figure in a black shirt against a white background with a compressed circular title and it worked. I always believe covers should tell the buyer what kind of book to expect in the most straightforward manner. Today’s complex covers are full of ambiguity and leave me rather cold. And as for the current trend of a single black silhouette walking off into some obscurity. It’s an image that leaves one wondering, are we dealing with a thriller, a spy story, a romance, or what? It has been done to death and it’s about time art directors come up with something new.

The Edge series was a ground-breaker of course, but before that I did the covers for the James Gunn series of Westerns, which may have inspired the publisher’s to let me have a try with Edge. I was following in the footsteps of the great Clifton-Dey who started illustrating the series, but after their initial success I was allowed pretty much to go my own way until the series finished. Basically Edge was a simple design format—a figure in a black shirt against a white background with a compressed circular title and it worked. I always believe covers should tell the buyer what kind of book to expect in the most straightforward manner. Today’s complex covers are full of ambiguity and leave me rather cold. And as for the current trend of a single black silhouette walking off into some obscurity. It’s an image that leaves one wondering, are we dealing with a thriller, a spy story, a romance, or what? It has been done to death and it’s about time art directors come up with something new.  Your creation of Western covers and novels dominate your portfolio. Does the genre hold a special pull for you? If so, why?

Your creation of Western covers and novels dominate your portfolio. Does the genre hold a special pull for you? If so, why?

I’m a huge movie fan and it was always the Western that attracted me most. Being a city boy the feelings of space and freedom encouraged by the Westerns of the late fifties and sixties expanded horizons in a literal and imaginary way.

Your output of painted covers has been wonderfully prolific. How do you bring a fresh perspective to new commissions?

Your output of painted covers has been wonderfully prolific. How do you bring a fresh perspective to new commissions?

Sometimes criticism can do it. That forces one to look elsewhere and see what is going on in the publishing world and adapt to different approaches. At my age, I’ve had to realize that often I’m steeped in the painterly tradition I was brought up in/ As many covers are now governed by stock photography and computer technology, it calls for finding a way of breaking the mold and combining the two.

As a man with the soul of a creative, do you feel art has a responsibility to the wider world?

As a man with the soul of a creative, do you feel art has a responsibility to the wider world?

In truth I never considered myself more than a commercial artist. I did what I did to make money and put food on the table. To think of any higher perspective would have been out of place and somewhat arrogant in this context. As a commercial artist you supply the image that is asked for, and any expansion into a more esoteric world would be uncalled for and most unlikely result in no payment.

However, in writing the advent of self publishing has been a more liberating experience. Early on, I sent out many manuscripts to publishers with the usual indifferent photocopied rejection slip received in reply. Thankfully those day are over now. Anybody can put what they like out into the ether, and my writing allows me to explore broader avenues, albeit within the strictures of the chosen genre.

However, in writing the advent of self publishing has been a more liberating experience. Early on, I sent out many manuscripts to publishers with the usual indifferent photocopied rejection slip received in reply. Thankfully those day are over now. Anybody can put what they like out into the ether, and my writing allows me to explore broader avenues, albeit within the strictures of the chosen genre.  Should paint or words strive to show the world the way it is, the way it was, or the way it should be?

Should paint or words strive to show the world the way it is, the way it was, or the way it should be?

That’s an interesting question. In writing can we truly show the way the world was? It is difficult to create the old world for the modern reader as the mores, the terminology, and use of language was so different. If a writer wants to communicate with the modern reader, he has to use the language of the present day to some extent. It’s very much down to the abilities of the writer to get across the feelings of the period rather than resorting to any historical tract, which may be accurate, but has about as much impact as a geography lesson. I’m not so pompous as to think my scribbling’s will in any way affect the modern world. In my experience, the average person goes their own way and in the long run one cannot change anyone else.

Should art stand apart from the human experience or attempt to understand and explain it?

Should art stand apart from the human experience or attempt to understand and explain it?

They say that within the heart of every Illustrator there is the soul of a fine artist wanting to get out. I suppose there is some truth in that, but in my case I have struggled so long in the commercial world I find I approach my fine art paintings with all the Illustration techniques I’ve used over the years, which in itself, I find an inhibitor. My own personal work—except for some of the more representational still life paintings—proves to be too obscure and abstract for popular taste.

Within the written word, though, there exists the means to take our modern dilemmas and transpose them into another time and place, and within that disguise, to explore and attempt to rationalize them without offence.

Within the written word, though, there exists the means to take our modern dilemmas and transpose them into another time and place, and within that disguise, to explore and attempt to rationalize them without offence. Furthermore, I’d say there is a fine line now between accepted Fine Art and Illustration. The same commercial values apply, and its still a matter of who-you-know, plus critics who claim to understand what is great and what isn’t. Reproduction techniques have also now vastly undervalued art in its purest sense, so a poster print of a painting that might have taken a year or more for the artist to complete, which is sold for little money, means he is unlikely to regain its worth in time spent once the producer, promoter, and distributor have had their say.

During my time in the illustration world of the UK, it was never treated with the respect it received in the US, where fees represented more of an appreciation of the skills involved. Deadlines and indifference do not make for good bedfellows. After the advent of computers in the mid-eighties, many of my peers lost out as opportunities for work declined, and they were relegated to lesser employment just to survive. Some great illustrators fell by the wayside during that period, and I consider myself lucky to still be going.

During my time in the illustration world of the UK, it was never treated with the respect it received in the US, where fees represented more of an appreciation of the skills involved. Deadlines and indifference do not make for good bedfellows. After the advent of computers in the mid-eighties, many of my peers lost out as opportunities for work declined, and they were relegated to lesser employment just to survive. Some great illustrators fell by the wayside during that period, and I consider myself lucky to still be going.  If you could paint or write whatever you wanted and make a good living from it, what would you paint or write?

If you could paint or write whatever you wanted and make a good living from it, what would you paint or write?

I have two ambitions: to finish a novel I began some twenty years ago about a Templar knight. It’s an unusual work for me and involves a complex plot and, as ever, needs a great deal of research. Needless to say, the cover already exists, but the time for the rest is harder to find. Secondly, I wish to bring into the light, edit, and publish my father’s memoir, including many pictorial images of his work. ****** Thanks to Tony for his thoughtful responses. I look forward to reading much more of his work and to the pleasure of viewing many more of his covers.

Published on October 28, 2019 07:25

October 25, 2019

TV TIE-INS—F TROOP

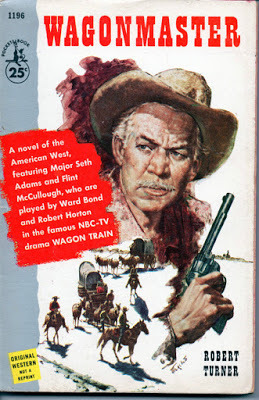

TV TIE-INSF-TROOPRecently, I've been enjoying collecting and reading TV tie-in novels connected to Western TV shows from the fifties and sixties. This was a golden age when Westerns dominated the small screen—one season having a record 39 Westerns on the air scattered among the the three major networks.

TV TIE-INSF-TROOPRecently, I've been enjoying collecting and reading TV tie-in novels connected to Western TV shows from the fifties and sixties. This was a golden age when Westerns dominated the small screen—one season having a record 39 Westerns on the air scattered among the the three major networks.  During this era, toys and lunch boxes associated with popular shows were common. However, tie-in novels were oddities as the commercial draw and advertising benefits were yet to be established. Shows such as Rawhide, Wagon Train, The Deputy, and Have Gun Will Travel were popular enough to justify a publisher taking a chance on an original novel tied to the show, but they were still considered nothing more than a second thought.

During this era, toys and lunch boxes associated with popular shows were common. However, tie-in novels were oddities as the commercial draw and advertising benefits were yet to be established. Shows such as Rawhide, Wagon Train, The Deputy, and Have Gun Will Travel were popular enough to justify a publisher taking a chance on an original novel tied to the show, but they were still considered nothing more than a second thought. Most of the TV tie-ins to the Western shows of the day were original novels incorporating the characters from the associated show. However, in the case of the popular half-hour show Tales of Wells Fargo, the tie-in paperback was a collection of episodes from the show, which were novelized by Frank Gruber, a recognizable name in Western fiction, from scripts he originally created for the show. Novelizing scripts was both the fastest and cheapest way to get the stories into book form.

Most of the TV tie-ins to the Western shows of the day were original novels incorporating the characters from the associated show. However, in the case of the popular half-hour show Tales of Wells Fargo, the tie-in paperback was a collection of episodes from the show, which were novelized by Frank Gruber, a recognizable name in Western fiction, from scripts he originally created for the show. Novelizing scripts was both the fastest and cheapest way to get the stories into book form. The strange thing about these early Western TV tie-ins was the apparent reluctance on the part of the publishers to emphasize or capitalize on their connections to the shows. Instead of sporting photos of the heroes of the shows or dramatic scenes from the shows on their covers, inferior artwork was used. These illustrations did depict the main character or characters from the shows, but in a barely recognizable manner. Cover copy might mention the connection to the TV show, but in small print.

The strange thing about these early Western TV tie-ins was the apparent reluctance on the part of the publishers to emphasize or capitalize on their connections to the shows. Instead of sporting photos of the heroes of the shows or dramatic scenes from the shows on their covers, inferior artwork was used. These illustrations did depict the main character or characters from the shows, but in a barely recognizable manner. Cover copy might mention the connection to the TV show, but in small print. Sometimes the title of the actual show was used, but other times (as in the case of the three Wagon Train tie-in paperbacks) innocuous, non-specific titles were used. It was as if the publishers were hoping if a potential reader didn't like the show, they might pick up the book anyway not realizing the connection.

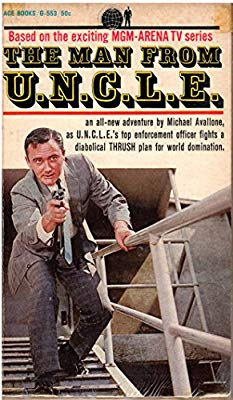

TV tie-ins would become more prominent in the seventies. By this time television had changed it's focus from Westerns to crime and secret agent shows. TV tie-in novels had changed as well. Garish photos from the shows were now pasted across their covers in full color. Big fonts were used to highlight the TV title, making sure potential readers didn't miss the connection to their favorite show.

By this time, tie-in novelizations and original novels connected to TV shows were recognized as a valuable part of raising a show's profile. As a result even mildly successful shows, and sometimes shows that proved to be disasters in the ratings upon airing, had tie-in novels on the spinner racks and bookstore shelves of the day.

Because of the plethora and continued demand for TV tie-in books, the interior prose was often slapdash, produced by hacks looking to make a quick buck in the work-for-hire market, where a one time immediate payment for a manuscript was paid—with no future royalties—and the copyright remaining with the publisher and not the author.

This could result in lopsided returns. One such example is Ace books Man From U.N.C.L.E. tie-in novels. A number of good pros, including solid writers like Michael Avallone and Harry Whittington, were paid a one time work for hire fee of $1,000 for their original novel efforts. However, because of the phenomenal popularity of the show, their books went into numerous printings—selling millions of copies, in multiple languages worldwide—making a substantial fortune for the publisher, but no further income flow for the authors.

This could result in lopsided returns. One such example is Ace books Man From U.N.C.L.E. tie-in novels. A number of good pros, including solid writers like Michael Avallone and Harry Whittington, were paid a one time work for hire fee of $1,000 for their original novel efforts. However, because of the phenomenal popularity of the show, their books went into numerous printings—selling millions of copies, in multiple languages worldwide—making a substantial fortune for the publisher, but no further income flow for the authors. Not all of these TV tie-ins were poorly written. Authors who were reliably able to complete a tie-in manuscript under the pressure of short deadlines where journeymen scribblers—many transitioning from writing for the pulps, where the speedy production of words meant food on the table...

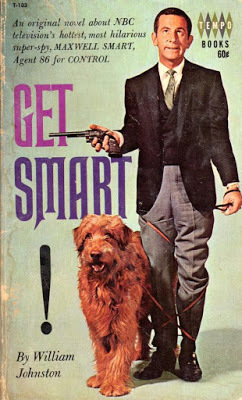

Not all of these TV tie-ins were poorly written. Authors who were reliably able to complete a tie-in manuscript under the pressure of short deadlines where journeymen scribblers—many transitioning from writing for the pulps, where the speedy production of words meant food on the table... I recently found a copy of the F TROOP original tie-in novel The Great Indian Uprising by William Johnston—considered to be not only the king of tie-in writers, but also arguably the best.

I recently found a copy of the F TROOP original tie-in novel The Great Indian Uprising by William Johnston—considered to be not only the king of tie-in writers, but also arguably the best.  He was certainly the most prominent tie-in writer, always managing to catch the nuances of a show's characters and tone. This was certainly true of his seven original tie-ins for the spy spoof show Get Smart.

He was certainly the most prominent tie-in writer, always managing to catch the nuances of a show's characters and tone. This was certainly true of his seven original tie-ins for the spy spoof show Get Smart.The tie-in was published by Whitman in their traditional line of juvenile novels. Physically, the Whitman books were distinctive with their square shape and art or photos directly printed onto the hardboard covers.

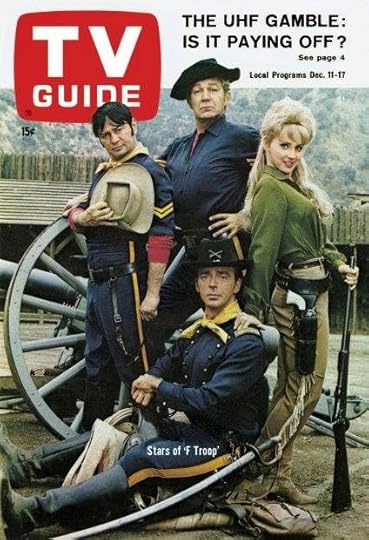

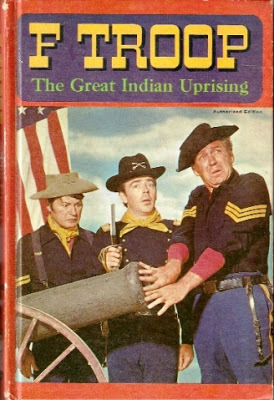

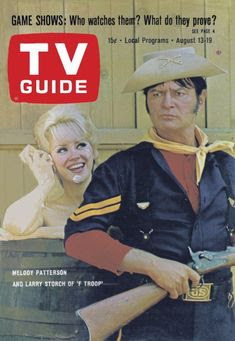

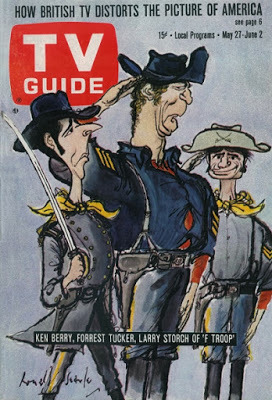

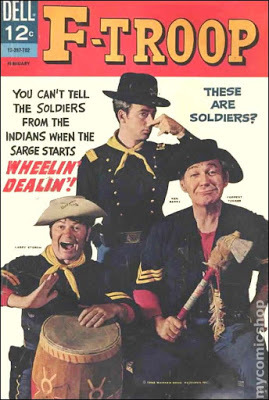

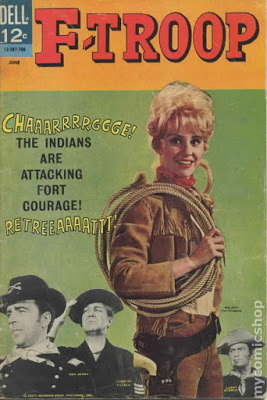

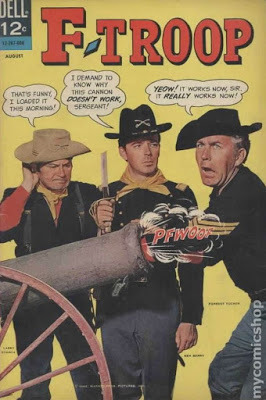

In the case of Whitman's F-Troop, the cover displays a stock publicity shot from the show featuring Sgt. O'Rourke (Forest Tucker), Corporal Argan (Larry Storch), and Captain Parmenter (Ken Berry).

In the case of Whitman's F-Troop, the cover displays a stock publicity shot from the show featuring Sgt. O'Rourke (Forest Tucker), Corporal Argan (Larry Storch), and Captain Parmenter (Ken Berry). Most of the books published by Whitman are considered collectibles today. While nominally aimed at a youthful PG audience, Whitman novels were often solid stories from noted writers, which an adult reader could also enjoy, and Johnston's F-Troop tale is no exception.

Sgt O'Rourke and Corporal Agarn are not making enough money selling Indian-made trinkets through O'Rourke Enterprises. So they decide to re-negotiate their contract with the Hekawis. Meanwhile, Chief Wild Eagle and Crazy Cat have decided they too need to make more money on their souvenirs. With big bucks at stake, the disharmony increases when a general from Washington arrives at Fort Courage determined to send F-Troop into bloody battle against Chief Wild Eagle and the Hekawis.

Sgt O'Rourke and Corporal Agarn are not making enough money selling Indian-made trinkets through O'Rourke Enterprises. So they decide to re-negotiate their contract with the Hekawis. Meanwhile, Chief Wild Eagle and Crazy Cat have decided they too need to make more money on their souvenirs. With big bucks at stake, the disharmony increases when a general from Washington arrives at Fort Courage determined to send F-Troop into bloody battle against Chief Wild Eagle and the Hekawis.  Naturally, the good natured, but goofy Captain Parmenter is stressed out trying to stop the proposed war. However, due to ordered confidentiality, he can't share his problems with his paramour Wrangler Jane. This makes him goofier than ever, and not knowing what is going on, Jane is worried Parmenter is mentally losing it.

Naturally, the good natured, but goofy Captain Parmenter is stressed out trying to stop the proposed war. However, due to ordered confidentiality, he can't share his problems with his paramour Wrangler Jane. This makes him goofier than ever, and not knowing what is going on, Jane is worried Parmenter is mentally losing it. Johnston does a fantastic job of capturing not only the flavor of the show, but also the specific voices of the actors portraying each of the characters. There is not a false note anywhere, so while reading it's easy to visualize the story as a bonus F-Troop episode.

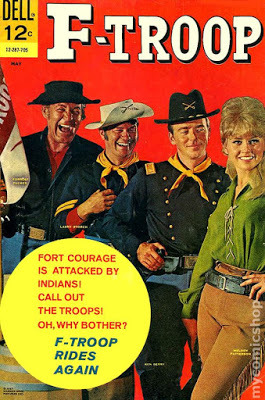

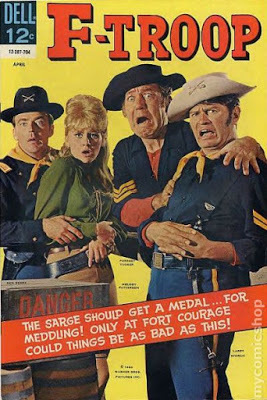

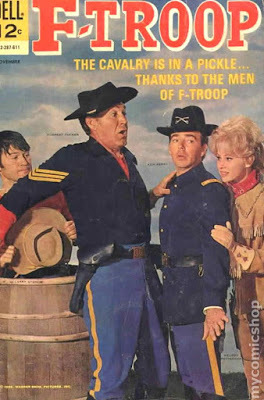

Johnston does a fantastic job of capturing not only the flavor of the show, but also the specific voices of the actors portraying each of the characters. There is not a false note anywhere, so while reading it's easy to visualize the story as a bonus F-Troop episode. Dell Comics (and later Gold Key Comics) also saw the profit potential in TV tie-ins, publishing numerous TV related tie-in comics. Some of these were only single issues while others ran for a number of issues of varying length. These too pull high prices in today's collector's market. Issues with a cover price of 12¢ can go for $40 or $50.

Dell Comics (and later Gold Key Comics) also saw the profit potential in TV tie-ins, publishing numerous TV related tie-in comics. Some of these were only single issues while others ran for a number of issues of varying length. These too pull high prices in today's collector's market. Issues with a cover price of 12¢ can go for $40 or $50.Between 1966 and 1977, Dell published seven F-Troop comics. These were written by D. J. Arneson with art by Tony Tallarico

F-Troop #1

F-Troop #1Don't Cross Your Bridges: In the main story, F-Troop is assigned to test a newly designed, pre-made bridge across the river from the Shug's hunting ground.

The Buffalo Hunter: A buffalo hunter ruins the picture taking business of the Hekawi Indians.

F-Troop #2

F-Troop #2Frantic Fireworks

What Goes Up...

F-Troop #3

Off the Track: F-Troop is assigned to bring a train to a station thru hostile Indian country. The Camel Corps: F-Troop is assigned to test camels for possible reconnaissance and patrol work. The Devilish Divining Rod

F-Troop #4

F-Troop #4The Wind Wagon: F-Troop is assigned to test Wind Wagons, which may serve to move cavalry rapidly. They are wagons with a mast and a sail blown by the wind. The Nightmare Night March: F-Troop goes on a night march to surprise General Withers.

F-Troop #5

F-Troop #5The Hekawi Rent-A-Horse: The Shugs steal F-Troop's horses forcing the Calvary to rent horses from the Hekawi.

Happy Birthday Hekawis: O'Rourke enterprises set up a carnival to honor the Hekawis.

The Captives:The Shugs capture Agarn and O'Rourke.

F-Troop #6

F-Troop #6The Attack

The Salt and Peppered Mine

Survival Course

F-Troop #7

Clown Prince's Visit: Crown Crown Prince Munster visits Fort Courage. Camouflage Dodge: Fort Courage gets camouflage paint and everything turns invisible.

Special Delivery: Carrier pigeons may be the solution to faster official communications with Fort Courage.

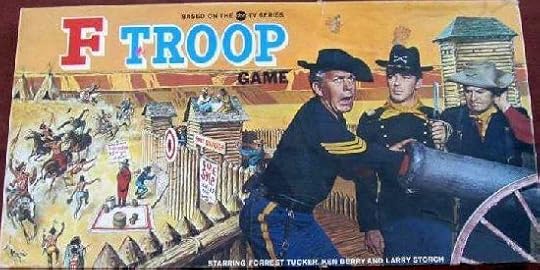

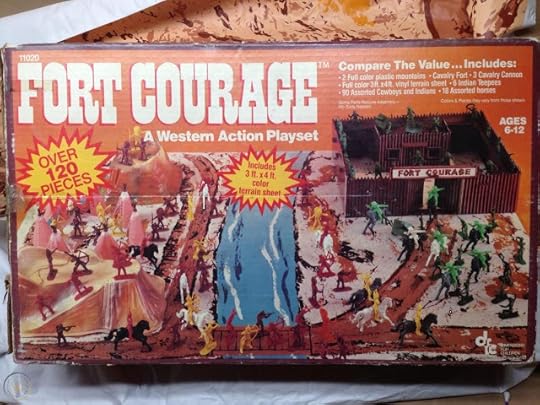

For a short-lived amiable, but ultimately silly show (which would be considered horribly un-PC by today's woke generation), F-Troop generated a number of other tie-ins, including games, figurines, and several iterations of Fort Courage play sets. It also generated more than it's fair share of TV Guide covers.

Some may remember a Fort Courage tourist attraction along Route 66 in Arizona. Today, it is abandoned and dilapidated. During its heyday, however, unsuspecting visitors were not 'discouraged' from believing it was a real U.S. Army fort and the location where F-Troop was filmed.

Some may remember a Fort Courage tourist attraction along Route 66 in Arizona. Today, it is abandoned and dilapidated. During its heyday, however, unsuspecting visitors were not 'discouraged' from believing it was a real U.S. Army fort and the location where F-Troop was filmed.  Visitors were also duped into thinking all of the F-Troop memorabilia sold in the mockup of Wrangler Jane's Trading Post were officially licensed. This was not true in the least. The tourist trap Fort Courage had absolutely no connection to the show. However, it's existence was a scam worthy of O'Rourke Enterprises and the Hekawis.

Visitors were also duped into thinking all of the F-Troop memorabilia sold in the mockup of Wrangler Jane's Trading Post were officially licensed. This was not true in the least. The tourist trap Fort Courage had absolutely no connection to the show. However, it's existence was a scam worthy of O'Rourke Enterprises and the Hekawis.

Published on October 25, 2019 13:05

October 22, 2019

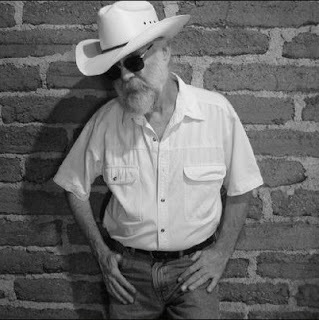

STEPHEN MERTZ—FIGHTING CODY’S WAR

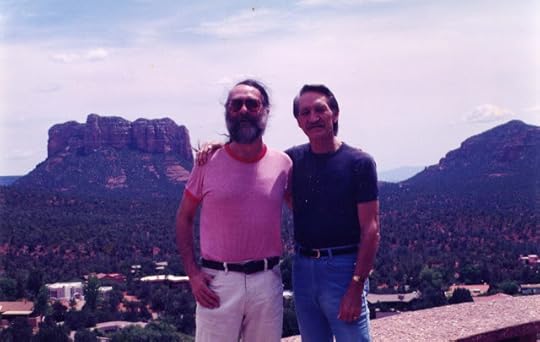

STEPHEN MERTZFIGHTING CODY’S WAR Full disclosure up front. Stephen Mojo Mertz and I have been friends since our early days of mystery fanzines. We both broke into professional fiction writing in the mid-eighties writing men’s adventure series paperbacks published under pseudonyms. Since those days, we’ve continued our friendship through years of publishing successes under our own names, mystery conventions, and marathon used bookstore crawls. We’ve also been through the proverbial hell and high water of being poorly treated as mid-list writers by the major New York legacy publishers who were once the gatekeepers of bestsellerdom. We’ve also been part of the e-book revolution breaking free from those legacy publishers and working with the new breed of smaller independent publishers.

STEPHEN MERTZFIGHTING CODY’S WAR Full disclosure up front. Stephen Mojo Mertz and I have been friends since our early days of mystery fanzines. We both broke into professional fiction writing in the mid-eighties writing men’s adventure series paperbacks published under pseudonyms. Since those days, we’ve continued our friendship through years of publishing successes under our own names, mystery conventions, and marathon used bookstore crawls. We’ve also been through the proverbial hell and high water of being poorly treated as mid-list writers by the major New York legacy publishers who were once the gatekeepers of bestsellerdom. We’ve also been part of the e-book revolution breaking free from those legacy publishers and working with the new breed of smaller independent publishers.  If Steve and I had grown up together, we would have been the terrors of the neighborhood. There would have been countless games of cowboys and outlaws, cops and crooks, and spy vs. spy. We would have saved the world repeatedly by infiltrating supervillains' hidden lairs and thwarting their nefarious plans. And like our heroes, we would have gotten all the hot babes, not that we would have known what to do with them. Still, the likes of Emma Peel, Honey West, Cinnamon Carter, Agent 99, April Dancer, and Charlie’s Angles became our defining definition of juvenile desires.

If Steve and I had grown up together, we would have been the terrors of the neighborhood. There would have been countless games of cowboys and outlaws, cops and crooks, and spy vs. spy. We would have saved the world repeatedly by infiltrating supervillains' hidden lairs and thwarting their nefarious plans. And like our heroes, we would have gotten all the hot babes, not that we would have known what to do with them. Still, the likes of Emma Peel, Honey West, Cinnamon Carter, Agent 99, April Dancer, and Charlie’s Angles became our defining definition of juvenile desires. While we didn't grow up together, the imaginary playgrounds we built, filled with heroes, villains, and hot babes were essentially the same. We watched the same shows and hung out with the same imaginary friends. Calvin and Hobbs had nothing on us.

Because we both read books, lots and lots of books, most beyond our age level, our imaginations thrived and blossomed. The likes of Mike Hammer, Philip Marlowe, and Conan the Barbarian gave us a whole new understanding of manhood, while Modesty Blaze and Mike Hammer's Velda secretly stoked our teen carnal desires.

Because we both read books, lots and lots of books, most beyond our age level, our imaginations thrived and blossomed. The likes of Mike Hammer, Philip Marlowe, and Conan the Barbarian gave us a whole new understanding of manhood, while Modesty Blaze and Mike Hammer's Velda secretly stoked our teen carnal desires. We would have been best pals back then. And once our paths crossed, we did become, and remain, best pals today. We recognized we are brothers from different mothers, who unlike most of our peers, never left our imaginary childhood friends behind. They have stayed with us, leading us both to becoming writers—quick-draw wordslingers firing bullets on the page instead of at high noon on Main Street.

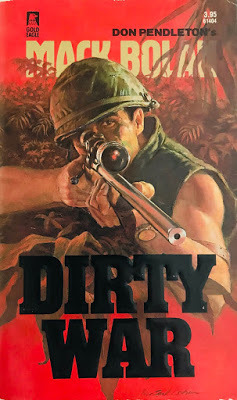

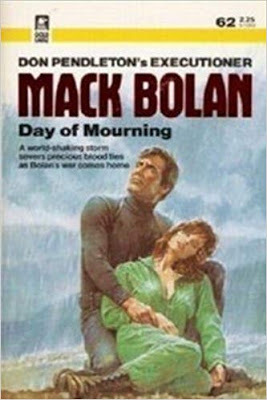

I rode the wild west as Pike Bishop in a series about a character named Diamondback—a wanted man who acted as a judge or go-between to settle disputes among outlaw factions. Steve took a different route, writing Executioner novels under the mentorship of Don Pendleton—the man who singlehandedly began the literary revolution known as the action adventure genre.

Stephen Mertz would go on to create one of the most significant men’s action adventure series in the genre. MIA Hunter, featuring a three-man team of modern day warriors that spawned imitators but none as crackerjack as the adventures Mertz created into which to drop his characters Mark Stone, Hog Wiley and Terrance Loughlin. MIA Hunter has become iconic as it brilliantly tied into our cultural guilt regarding captured service men left behind after the Vietnam War.

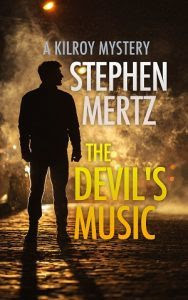

Stephen Mertz would go on to create one of the most significant men’s action adventure series in the genre. MIA Hunter, featuring a three-man team of modern day warriors that spawned imitators but none as crackerjack as the adventures Mertz created into which to drop his characters Mark Stone, Hog Wiley and Terrance Loughlin. MIA Hunter has become iconic as it brilliantly tied into our cultural guilt regarding captured service men left behind after the Vietnam War. The men’s adventure genre wound down in the ‘90s, but Stephen Mertz was only getting started. In the next two decades, Mertz honed his craft writing both cutting edge thrillers and more in depth and personal stories about the music scene of which Steve was a part. Today, having become a master of his craft, his name on a book cover guarantees a riveting read ahead for the reader.

And now it is time to bring things full circle. The action adventure genre has quietly begun a new revolution. New series such as Reaper and Stiletto are garnering wide response from new readers hungry for fast-paced action. While it takes Jack Reacher or Mitch Rapp 400 pages or more to wipe out the bad guys today, the likes of such original men’s adventure heroes as The Executioner or The MIA Hunter did it in two hundred pages. They were lean, mean, and lethal as hell—and now those guys are back.

And now it is time to bring things full circle. The action adventure genre has quietly begun a new revolution. New series such as Reaper and Stiletto are garnering wide response from new readers hungry for fast-paced action. While it takes Jack Reacher or Mitch Rapp 400 pages or more to wipe out the bad guys today, the likes of such original men’s adventure heroes as The Executioner or The MIA Hunter did it in two hundred pages. They were lean, mean, and lethal as hell—and now those guys are back.With the release of the first entry in the new Cody’s War series, Stephen Mertz has returned to his roots, and he’s brought a whole new level of deadly experience with him. Fortunately, I was able to distract him from his blazing keyboard long enough for a quick interrogation: ******

During the early days of your writing career, you found yourself under the mentorship of the man who set the standard for men’s action adventure—the legendary Don Pendleton. How did this evolve and what were the most important lessons you took from the experience?

During the early days of your writing career, you found yourself under the mentorship of the man who set the standard for men’s action adventure—the legendary Don Pendleton. How did this evolve and what were the most important lessons you took from the experience? My friendship with Don began when a wannabe writer guy who’d read a half-dozen Executioner novels wrote a fan letter out of the blue to a best-selling author. Don wrote back two months later, a long and friendly response. A sort of pen-pal friendship grew between us over the years that followed, a few letters per year. This was before cell phones and emails, remember. Don offered to read one of my unsold manuscripts. Hell, they were ALL unsold at that time! He sent me a five-page single-spaced critique of that manuscript! The book eventually sold, incidentally, with Don’s suggestions incorporated into it. I know now that most professional writers are broached often by those wanting a critique of something they’ve written. I didn’t ask; Don freely offered. That’s a mark of the kind of guy he was, generous beyond belief in every way.

We met a few years later during one of my open-end summer road trips. An afternoon visit turned into a layover at Pendle Hill, Don’s spread in Brown County, Indiana. Don treated me to a whirlwind—I should say, death-defying—tour of the area in his new fire engine red ragtop Cad (top down, of course). Through rustic rural towns with names like Gnaw Bone, we pretty much yakked writing non-stop.

We met a few years later during one of my open-end summer road trips. An afternoon visit turned into a layover at Pendle Hill, Don’s spread in Brown County, Indiana. Don treated me to a whirlwind—I should say, death-defying—tour of the area in his new fire engine red ragtop Cad (top down, of course). Through rustic rural towns with names like Gnaw Bone, we pretty much yakked writing non-stop.  I’d been writing like crazy in those days all through high school, the Army and working the road as a musician. It’s a hard business to break into and I hadn’t sold a word. That summer I was 29. Don was 49. As I was also to learn later, turning out four books per year like he was at the time, about the same hero doing more or less the same things, it can drain a guy creatively. For a while after that I served at Don’s request as his assistant on the periphery of some of the Bolan titles while he was still with Pinnacle.

I’d been writing like crazy in those days all through high school, the Army and working the road as a musician. It’s a hard business to break into and I hadn’t sold a word. That summer I was 29. Don was 49. As I was also to learn later, turning out four books per year like he was at the time, about the same hero doing more or less the same things, it can drain a guy creatively. For a while after that I served at Don’s request as his assistant on the periphery of some of the Bolan titles while he was still with Pinnacle.When the franchise was sold to the Harlequin imprint, Gold Eagle, it was only natural that I’d be one of the writers Don recommended for their program. I wrote a dozen books in the GE Mack Bolan series. After Don moved to Arizona our friendship only deepened through the years until his passing. I can honestly say that after my own father, Don Pendleton was the most influential man in my life both as a writer and as a man.

Besides Don, are there other writers who have inspired you?

Besides Don, are there other writers who have inspired you? Ouch, that’s always a tough one. The honest truth is that as a new writer and even today, every really good novel leaves its mark. For the modern action adventure genre that Cody’s War falls into, well, Clive Cussler in his prime, that’s as good as it gets. Cussler is the gold standard. As far as writers I read coming up who are now out of print and mostly forgotten, I’ve always wanted to write as well as Edward S. Aarons. His Assignment series is a personal favorite. But let’s not forget the movies! Cinema has always been a strong influence on my prose going back to action directors like Walter Hill and Jon Woo. Love or hate ol’ Tom Cruise, you’ve got to admit the last couple of his Mission Impossible flicks are totally kickass, delivering at every level of heroic fiction. That’s the vibe of Cody’s War.

You have long lobbied for a change of emphasis from the label of the men’s action adventure genre to simply the action adventure genre. Why do you feel this is important?

Why make a genre gender specific? The gender of my readers does not concern me. My novels are driven by interesting, dynamic men and women. What I have to offer is for everyone, not just half the species. It’s a mistake to limit a genre’s appeal by being so specific in its labeling.

Do you approach a series novel different to a standalone thriller?

Do you approach a series novel different to a standalone thriller? The physical process never changes. Three to five hours a day. Four or five days per week. I’m a creature of habit so the process is well in place no matter what I’m writing. But yeah, it’s different in another way. The challenge of the standalone is that you’re only going to get this one chance to tell these characters’ story so you’d better get it right. Make sure you get everything in while not letting the book become overly long and ponderous. A series provides more room to swing. The characters have more than one book for their story to breathe and unfold. With a series I’m reuniting each book with characters whose company I enjoy and ideally that feeling is shared with the reader.

What draws you to a good story—what do you look for first, character, plot, theme?

What draws you to a good story—what do you look for first, character, plot, theme? All three! The perfect combination is a strong plot with strong characters who have something to say. That’s a hard combination to beat. Works every time. But too much of so-called pulp fiction is populated by static characters that eventually grow stale because they never change. You asked earlier about lessons learned from Don Pendleton. Don’s original Executioner novels relate not merely a series of encounters but a clear progression in character development that connects and transcends the individual episodes. Bolan is not the same guy at the end of Book #38 as he was when going into Book #1. He kept growing and changing as a real person would throughout a series of encounters. That was a lesson learned. A general rule of writing is that memorable fiction stems from great characters. The essence of pulp fiction is rapid plot development. The name of my game is bringing those two elements together the way Don did.

With the resurgence of lean and mean action adventure series reaching a new generation of readers, what is it about the genre you believe speaks to them?

With the resurgence of lean and mean action adventure series reaching a new generation of readers, what is it about the genre you believe speaks to them? Thrillers have over the years become too damn long. It started decades ago with Robert Ludlum and Tom Clancy and is epidemic today. Fat is the only word that comes to mind. Most of these guys are decent writers but even when they start out with an engaging premise . . . too damn long! Sure, every novel should be as long or short as needs to be. But at its best the writing of action adventure is as lean and mean as the characters, without unnecessary padding. When someone tells me they’ve read a good thriller but it could have been cut by 100 pages--and I read that a lot these days in Amazon reviews--well, that’s not a novel I’d care to read. The trend to scale down action adventure back to its basics indicates that I’m not the only reader who feels that way.

When you decided to write the Cody’s War series, what were your goals and aspirations for it?

When you decided to write the Cody’s War series, what were your goals and aspirations for it? I’ve had the good fortune to join forces with Mike Bray and his hardworking crew at Wolfpack Publishing. They’ve repackaged and are successfully marketing the MIA Hunter series, and my entire backlist is available online through them in e-book format with sharp new paperback editions as well. Cody’s War is slanted for a concept in e-book publishing that’s not unlike the trend of binge watching TV shows. The first five novels are dropping as a Rapid Release series: a new novel will appear every three weeks. Dragonfire! and each of the subsequent Cody’s War book is a complete storyline unto itself set against an overreaching arc of plot and character is only resolved in the final volume.

What can readers expect now that Cody’s War has begun?

Not to be too coy about it, but I’m not sure . . . that’s part of the adventure! Could be a beginning of a series that will continue for years. I’ve delivered the first five novels to Wolfpack. I like this guy, Cody. He’s dealing with a world of heavy personal shit but that doesn’t stop him from seriously kicking ass around the world. He only takes on suicide missions. By the second book he’s partnering in the field with his CIA control officer, Sara. They make a great team. Sara’s the yinto Cody’s yang. Wait until you see them team up in Afghanistan in Book #4! Oh, yeah. It’s going to be a hot five-book ride. After that, we’ll see . . .

Thanks to Steve for hanging out. I’ll now release him from custody to get back to writing the next chapter in his thrilling exploits...

Published on October 22, 2019 15:25

October 21, 2019

WESTERN COMICS—KID MONIKER

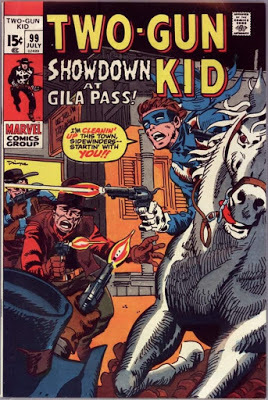

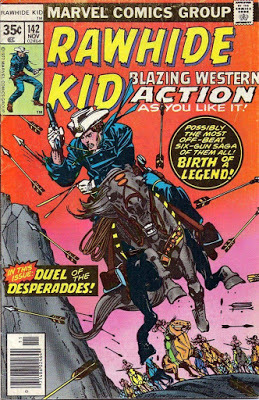

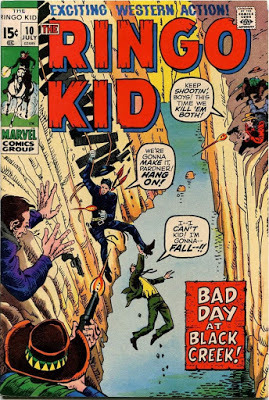

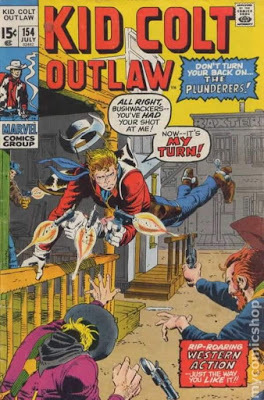

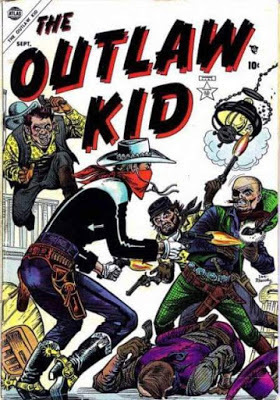

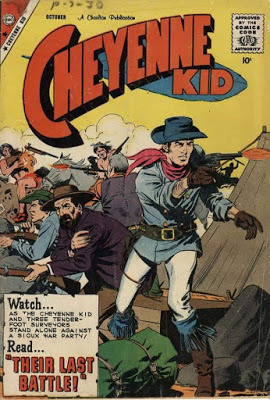

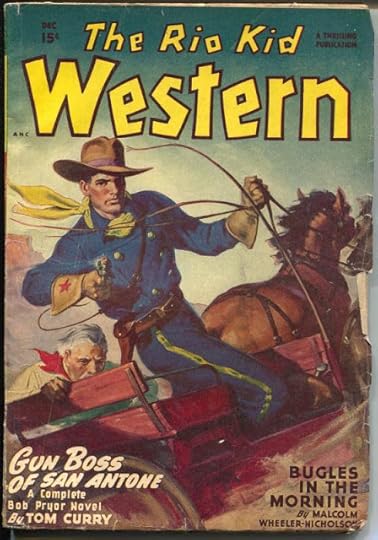

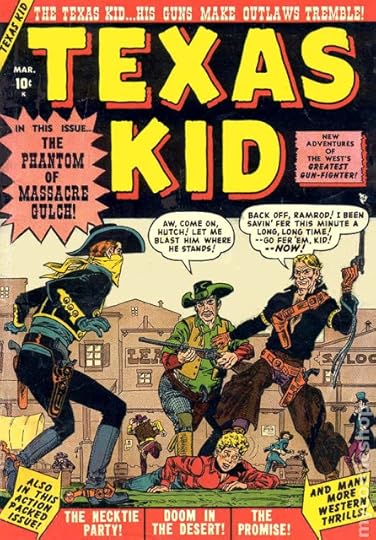

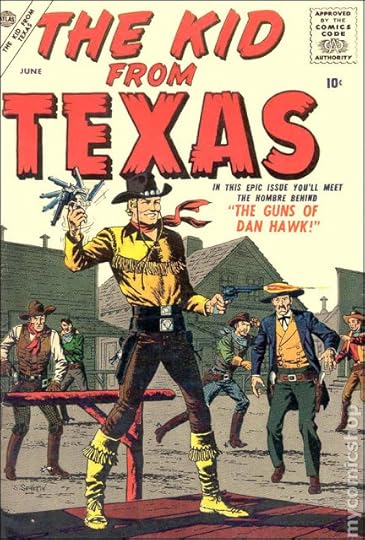

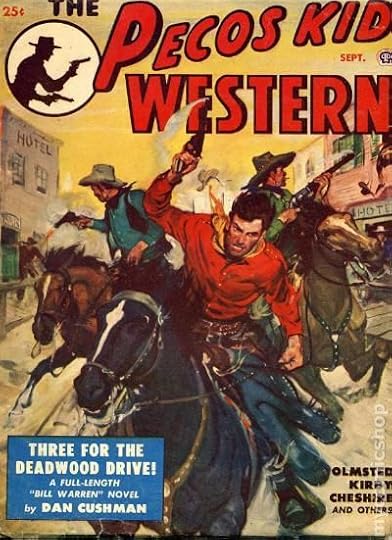

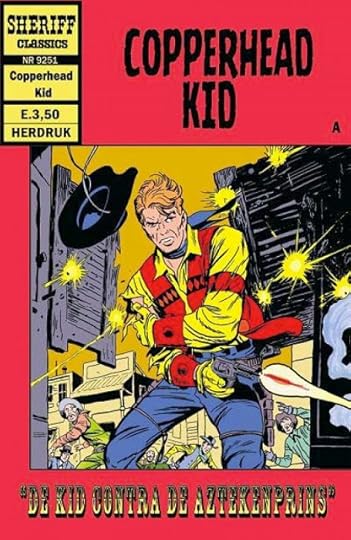

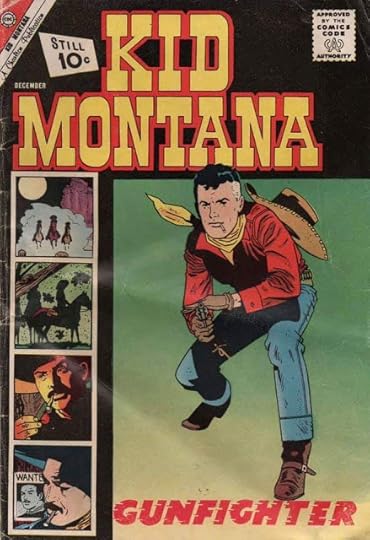

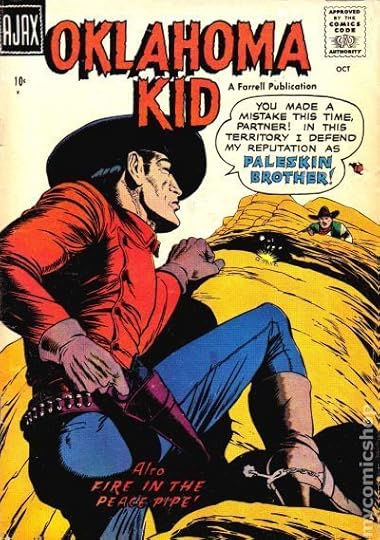

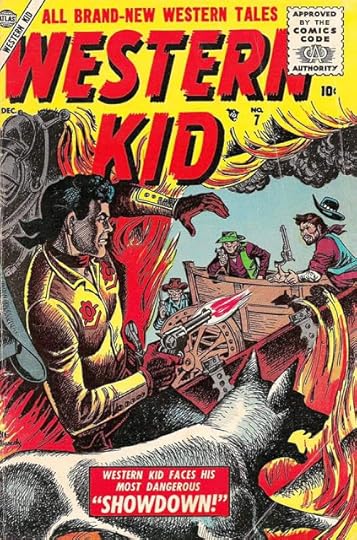

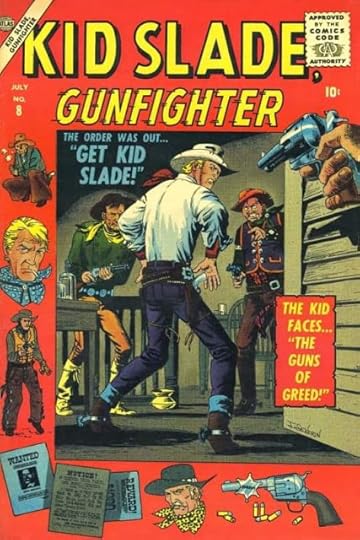

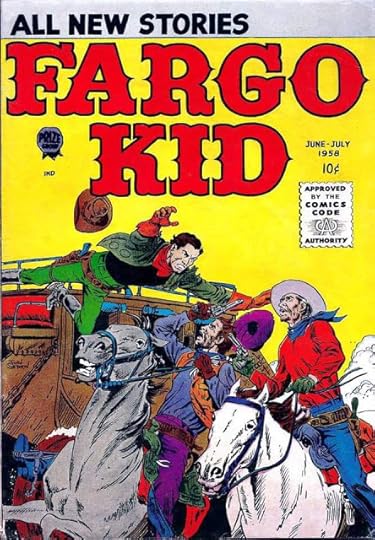

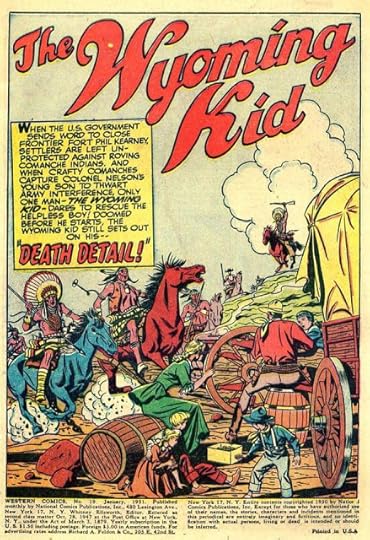

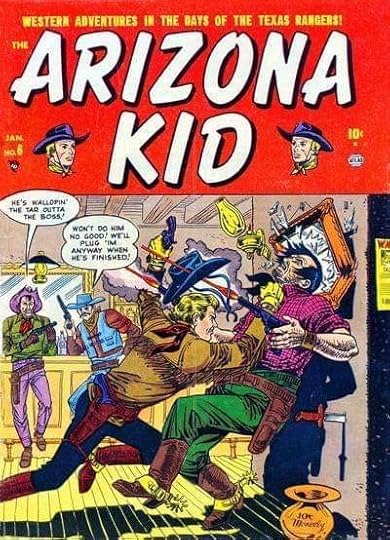

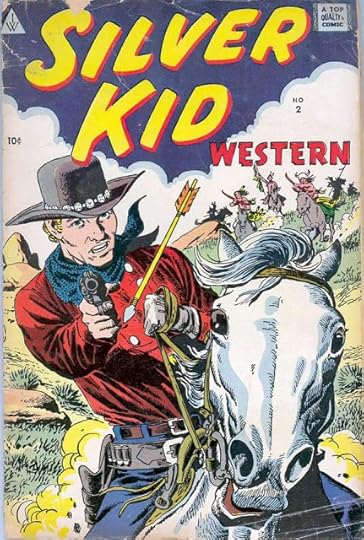

WESTERN COMICSKID MONIKERIf Western genre comics are any type of reliable indicator, the Wild West was overrun with pistol-toting, gunslinging, six-gun shooting, range riding, town taming youngsters.

WESTERN COMICSKID MONIKERIf Western genre comics are any type of reliable indicator, the Wild West was overrun with pistol-toting, gunslinging, six-gun shooting, range riding, town taming youngsters.  The best known of these juvenile delinquents were The Rawhide Kid, Two-Gun Kid, The Outlaw Kid, Ringo Kid, and Kid Colt, but there were a little red school house full of others.

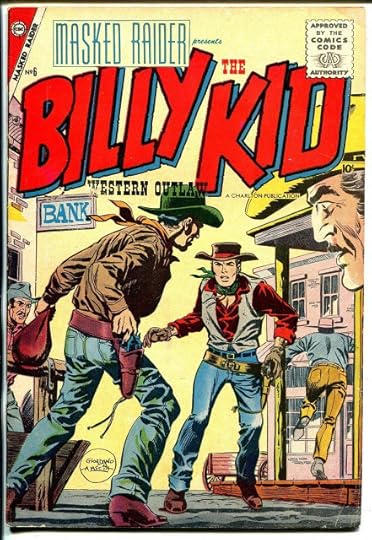

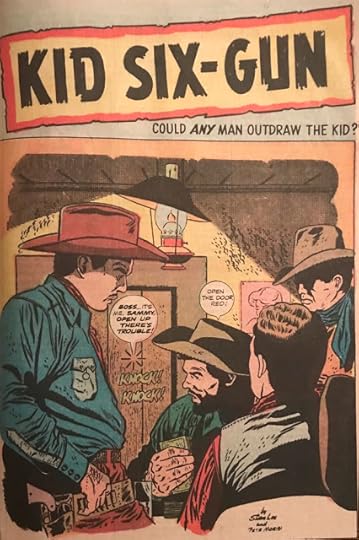

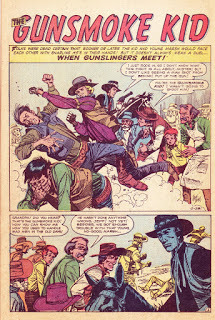

The best known of these juvenile delinquents were The Rawhide Kid, Two-Gun Kid, The Outlaw Kid, Ringo Kid, and Kid Colt, but there were a little red school house full of others. There were, of course, the generics—Kid Cowboy, Kid Six-Gun, Western Kid, The Gunsmoke Kid, and Billy the Kid, but these were the least colorful of the fast shooting Kids.

There were, of course, the generics—Kid Cowboy, Kid Six-Gun, Western Kid, The Gunsmoke Kid, and Billy the Kid, but these were the least colorful of the fast shooting Kids. Many states had their own representatives—Wyoming Kid, Arizona Kid, Oklahoma Kid, The Kansas Kid, Dakota Kid (North or South not specified), Kid Montana, The Colorado Kid, The Texas Kid, and The Kid From Texas (I guess Texas was big enough for two Kids).

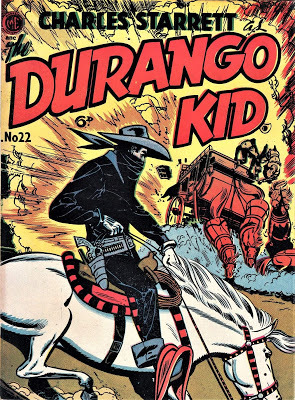

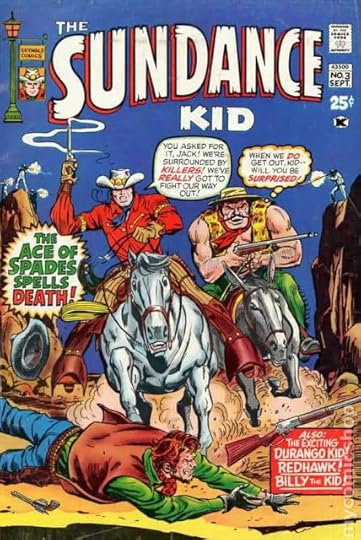

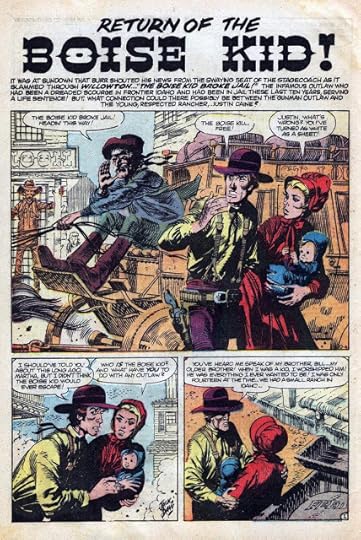

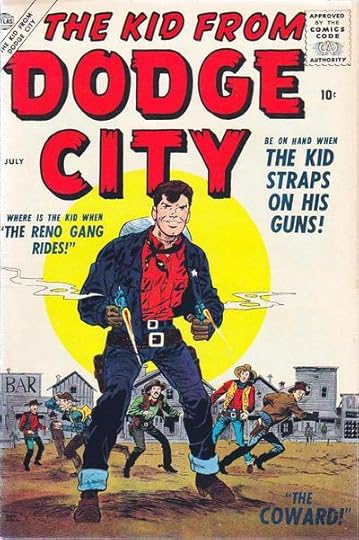

Many states had their own representatives—Wyoming Kid, Arizona Kid, Oklahoma Kid, The Kansas Kid, Dakota Kid (North or South not specified), Kid Montana, The Colorado Kid, The Texas Kid, and The Kid From Texas (I guess Texas was big enough for two Kids). Then there were those underage gunslicks who were named after a city because another Kid was already representing their state—Yuma Kid, The Dodge City Kid, Cheyenne Kid, The Boise Kid, Fargo Kid, The Durango Kid, The Chisholm Kid, The Pecos Kid, and one named after a river, The Rio Kid.

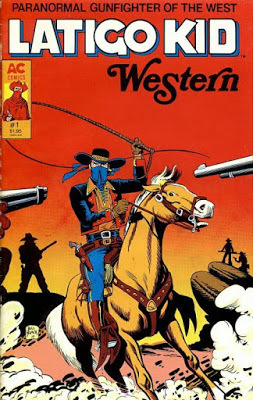

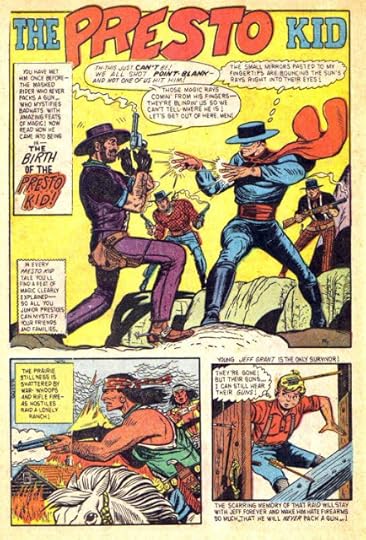

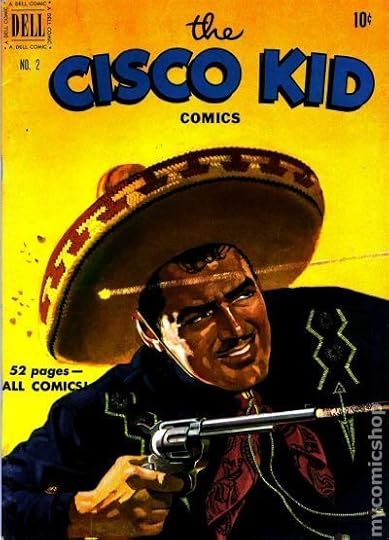

Then there were those underage gunslicks who were named after a city because another Kid was already representing their state—Yuma Kid, The Dodge City Kid, Cheyenne Kid, The Boise Kid, Fargo Kid, The Durango Kid, The Chisholm Kid, The Pecos Kid, and one named after a river, The Rio Kid. A few teen gunhawks drew on other inspirations for their monikers—Kid Dynamite, Kid Slade, Apache Kid, Silver Kid, The Cisco Kid, The Copper Kid, Latigo Kid, The Sundance Kid, The Hell Bent Kid, and my favorite—The Presto Kid (as in prestidigitation).

A few teen gunhawks drew on other inspirations for their monikers—Kid Dynamite, Kid Slade, Apache Kid, Silver Kid, The Cisco Kid, The Copper Kid, Latigo Kid, The Sundance Kid, The Hell Bent Kid, and my favorite—The Presto Kid (as in prestidigitation). The Kids were all deadly, as Ifast with their fists as they were with their guns. They could all shoot accurately while galloping on horseback, and split ropes with bullets fired from their six-guns at distances that would make a modern sniper balk. However, most important of all—they never lost their hats under any conditions.

The Kids were all deadly, as Ifast with their fists as they were with their guns. They could all shoot accurately while galloping on horseback, and split ropes with bullets fired from their six-guns at distances that would make a modern sniper balk. However, most important of all—they never lost their hats under any conditions.

Published on October 21, 2019 10:55

October 19, 2019

FROM THE MANOR TORN

FROM THE MANOR TORN

FROM THE MANOR TORNSTEPHEN MERTZ My friend Stephen Mertz is a prolific wordslinger who always delivers thrills and solid entertainment in every novel he writes. Like me, his early short stories were published in Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine—so we are brothers under the pen. Here in Steve's own words is the low down and dirty story of his first novel and the evil empire known as Manor Books...

******

It is with considerable joy that I introduce this new edition of my very first novel, a private eye thriller seeing new life in a brand new edition from Wolfpack Publishing. Herewith a few words to amuse & elucidate concerning my experience with Manor Books, the original mass market publisher of Some Die Hard. And you may quote me:

Back in the day, Manor Books was a low-end New York publishing house in the 1970s, operated by pack of thieving scuzzballs.

Thank you, and good night.

What’s that?

You want to know more? Well, okay. Here’s the story of how Manor Books tried to screw me and how I screwed them right back, via long distance no less, without spending a penny.

I wrote Some Die Hardin 1975 while I was living in Denver. Private eye Rock Dugan's first and only case. I dedicated the book to my mentor and brother writer, the late Don Pendleton, who was generous and helpful in his critique of the novel in manuscript form.

Writing the book was fun. Finding a home for it with a publisher took another four years. During those four years, I sold a handful of stories to Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine while a New York agent circulated Some Die Hardfor publication consideration. It received a polite round of encouraging words, but no acceptance.

Writing the book was fun. Finding a home for it with a publisher took another four years. During those four years, I sold a handful of stories to Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine while a New York agent circulated Some Die Hardfor publication consideration. It received a polite round of encouraging words, but no acceptance. After eventually quitting the agent and leaving Denver for the rural mountain life, I spotted a market report in Writers Digest. A mass market publisher in New York was looking for previously unpublished novelists who lived outside the New York area. The suggestion was the publisher—Manor Books by name—was reaching beyond the literary and pulp cliques of the Northeast, hunting for new talent in the heartland. Hey, that was me!

At the time, I owned a small second hand bookshop in Durango, Colorado—wall to wall unfinished wooden shelves packed with paperbacks. Actually had an entire room devoted to Harlequin romances. Until about five years earlier, Durango was strictly a cowboy and mining town. Then the hippies discovered it. The tourists came next and, by the time I arrived in the 1970s, Durango’s residents grew to include people drawn from everywhere. Writers. Artists. Musicians. Movie people (parts of Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid, among other films, were shot in the area). Everyone I hung out with was from somewhere else. We preferred the back roads and the pines and peace and quiet to the city life most of us had left behind. We were young, broke and happy. A bohemian, hedonistic, fun lifestyle. Durango was that kind of place.

At the time, I owned a small second hand bookshop in Durango, Colorado—wall to wall unfinished wooden shelves packed with paperbacks. Actually had an entire room devoted to Harlequin romances. Until about five years earlier, Durango was strictly a cowboy and mining town. Then the hippies discovered it. The tourists came next and, by the time I arrived in the 1970s, Durango’s residents grew to include people drawn from everywhere. Writers. Artists. Musicians. Movie people (parts of Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid, among other films, were shot in the area). Everyone I hung out with was from somewhere else. We preferred the back roads and the pines and peace and quiet to the city life most of us had left behind. We were young, broke and happy. A bohemian, hedonistic, fun lifestyle. Durango was that kind of place. So off went Some Die Hard. (The novel’s original title was The Flying Corpse, however it had been suggested a less, uh, spectacular title might stand a better chance of acceptance). Not only did I think Some Die Hard was a serviceable title, but so did writers Marvin H. Albert (under his Nick Quarry pseudonym) and Carroll John Daly—both of whom had used the same title in their day. I snail-mailed Some Die Hard over the transom (unsolicited) to Manor, and it took those slicks all of a New York minute to jump on a guy living way out in the Rockies, without a telephone.

So off went Some Die Hard. (The novel’s original title was The Flying Corpse, however it had been suggested a less, uh, spectacular title might stand a better chance of acceptance). Not only did I think Some Die Hard was a serviceable title, but so did writers Marvin H. Albert (under his Nick Quarry pseudonym) and Carroll John Daly—both of whom had used the same title in their day. I snail-mailed Some Die Hard over the transom (unsolicited) to Manor, and it took those slicks all of a New York minute to jump on a guy living way out in the Rockies, without a telephone.They offered me $750.

Honestly, I was overjoyed. After four years, I felt finally vindicated as a writer. This being my first novel, though, and thinking $750 really wasn’t that much money, I trudged through the snow to a neighbor’s house. I asked to use their phone and called the only three published novelists I knew: Michael Avallone in New Jersey, Don Pendleton in Indiana, and Bill Pronzini in California. The unanimous advice from all three pros was to go for it. Get published. Start building a career—And ask for more money.

So I did, via a collect telephone call. Editor Larry Patterson was the soul of cordiality, promptly boosting the advance up to a thousand dollars without batting an eye. He was probably thinking, What the hell, we’re not going to pay the chump anyway.

I was aware Manor Books was a bottom line concern, so I decided to use a pseudonym to avoid getting boxed in as a low-rent writer. Hence, the original penname Stephen Brett—the surname being a tribute to Brett Halliday(aka: Davis Dresser), a favorite writer of the private eye stories I’d been reading since high school. Manor moved fast. There was money to be made. Within weeks I had a contract in hand for the astronomical sum of one thousand dollars, payment due upon publication.

ONE THOUSAND DOLLARS!

Dang. Where do I sign? My writing journal indicates I had fifty-four cents to my name the day that contract arrived.

The book was printed and bound (cheaply, with a recycled cover photo from an earlier Manor title, Tether’s End by Margery Allingham) and shipped. It was on sale within months, even in remote little ol’ Durango (the nearest cities being Albuquerque—4 hours away—and Denver—8 hours away). Since local friends were buying my book, supposedly so were readers from coast to coast. The book was reviewed in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine. The reviewer thought it was okay.

The book was printed and bound (cheaply, with a recycled cover photo from an earlier Manor title, Tether’s End by Margery Allingham) and shipped. It was on sale within months, even in remote little ol’ Durango (the nearest cities being Albuquerque—4 hours away—and Denver—8 hours away). Since local friends were buying my book, supposedly so were readers from coast to coast. The book was reviewed in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine. The reviewer thought it was okay.However, I hadn’t gotten paid. Hmm. Okay. I’ll call Larry. Quoth Larry, “Sorry, Steve. We’re a little backed up, blah, blah, blah. The check will be in the mail by the end of the week.” Great…Except the check wasn’t in the mail, that week or any of the following weeks.

The months dragged on. I still didn’t have a phone. Sometimes I’d pester my neighbor. Other times, if I was in town, I’d used one of the old-fashioned wooden telephone booths then in the lobby of Durango’s Strater Hotel. I’d think of Louis L’Amour, a local celeb of sorts since he had a summer place three miles north of town. It was known L’Amour had written some of his 1950s pulp westerns while staying at the Strater between jobs working in the area as a wrangler for what were then called dude ranches. I wondered if L’Amour ever sat in the same booth in his hungry days, hustling up New York editors for overdue payment. I’ll bet he had. Now it was my turn. I was young and this was part of the adventure.

But the bastards still didn’t send me my check.

I was beginning to understand. In looking for new novelists outside the New York area, what Manor Books was really doing was trolling the boonies for writers who were good enough to be published, but who wouldn’t have the clout or the resources to collect the money owed them. Manor would essentially be taking on books for free and walking away with 100% of the profits—Like I said—thieving scuzzballs.

I was beginning to understand. In looking for new novelists outside the New York area, what Manor Books was really doing was trolling the boonies for writers who were good enough to be published, but who wouldn’t have the clout or the resources to collect the money owed them. Manor would essentially be taking on books for free and walking away with 100% of the profits—Like I said—thieving scuzzballs.Among my customers at the book exchange was a nice guy with whom I’d become friends. His story was he’d been burned out while being a big city lawyer. At the time, he was on a soul search—holed up in a snowy mountain town in the middle of nowhere, honing his skills as a mime. He was an avid reader. And guess what? He still had his license to practice law in the state of New York.

“How’s about this?” I suggested over beer and pizza down at Farquart’s. “You get me that grand the sons of bitches owe me and you can waltz in and out of my shop anytime you want and take home as many books as you want for as long as the shop exists.” His eyes lit up. Some killer instincts do die hard, even in one who’d rather be a mime than a lawyer.

“How’s about this?” I suggested over beer and pizza down at Farquart’s. “You get me that grand the sons of bitches owe me and you can waltz in and out of my shop anytime you want and take home as many books as you want for as long as the shop exists.” His eyes lit up. Some killer instincts do die hard, even in one who’d rather be a mime than a lawyer.He said, “Here’s what we’ll do. Find out if your publisher has done this to anyone else. Then I’ll fire off a registered letter to them on my New York stationary. We’ll threaten to sue for the thousand and for damages. And if they’re doing this to other writers though the mail, we’ll threaten to charge them under Federal law with conspiracy to defraud using the US Postal System.”

Well, all right.

First thing I did was go down to the local book and magazine store (remember those) that was stocked with Manor titles. I wrote down the names of the authors of those books, and then went about searching for their addresses. My primary resource was the library reference work, Contemporary Authors. I made contact with two writers: Ralph Hayes, an active and not bad pulpist living in Florida (Manor had published his Check Force series) and James Holding, the author of a western.

Around this time, I received a letter from another new writer, James Reasoner, who’d soldhis first novel to Manor, but was having trouble getting paid and was hearing bad things about them. What did I know? I’d been reading and enjoying James’ stories in Mike Shayne, which by then had become a showcase for the emerging talent of my generation.

The following paragraph from my return letter to James (dated 4/4/80) pretty much captures the situation at that point.

All you have heard about Manor is only too true. They currently owe me a grand and the matter is now in the hands of my attorney. They were supposed to pay on publication and that was eight months ago. The lawyer gave them until April 10. But at least they sent me copies of my book! A guy named Jim Holding (not MWA’s James Holding, but his grandson) didn’t even know his book was out until I spotted it on the stands and wrote him about it. Manor has simply clammed up on him totally to keep from being hassled about on-publication payment. I also exchanged letters with Ralph Hayes. His feeling was Larry Patterson is an okay guy who unfortunately has editorial ambitions outstripping the company’s ability to pay promptly. Ralph’s advice (and my and Jim Holding’s experience bears this out) is to badger Patterson regularly (like every week) via collect phone calls, urging for payment.

All you have heard about Manor is only too true. They currently owe me a grand and the matter is now in the hands of my attorney. They were supposed to pay on publication and that was eight months ago. The lawyer gave them until April 10. But at least they sent me copies of my book! A guy named Jim Holding (not MWA’s James Holding, but his grandson) didn’t even know his book was out until I spotted it on the stands and wrote him about it. Manor has simply clammed up on him totally to keep from being hassled about on-publication payment. I also exchanged letters with Ralph Hayes. His feeling was Larry Patterson is an okay guy who unfortunately has editorial ambitions outstripping the company’s ability to pay promptly. Ralph’s advice (and my and Jim Holding’s experience bears this out) is to badger Patterson regularly (like every week) via collect phone calls, urging for payment.The windup: Upon receipt of the mime’s registered letter, Manor Books promptly mailed me a check for one thousand dollars.

Manor Books closed shop a few years later. Word gets around.

The mime? Every book he took out of the book exchange, he brought back after he’d read it so I could sell it again. So the whole deal didn’t really cost me a penny. I knew good people in Durango in those days.

Everyone got what they deserved, and what more can you ask for? Oh, and Some Die Hard remains—available as an e-book, which might just net me another thousand dollars…

Published on October 19, 2019 23:57

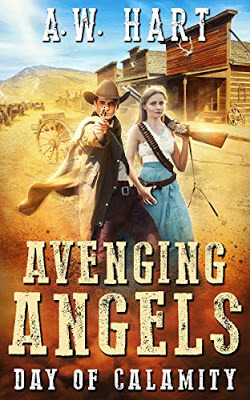

TOP WESTERN ACTION—AVENGING ANGELS/GUNSLINGER

TOP WESTERN ACTIONAVENGING ANGELSGUNSLINGERI'm currently editing and packaging two new Western series for Wolfpack. I worked on developing these series with two bestselling action writers, Peter Brandvold (Avenging Angels) and Mel Odom (Gunslinger).

TOP WESTERN ACTIONAVENGING ANGELSGUNSLINGERI'm currently editing and packaging two new Western series for Wolfpack. I worked on developing these series with two bestselling action writers, Peter Brandvold (Avenging Angels) and Mel Odom (Gunslinger).  Other books in each series are being written by an incredible lineup of wordslingers, all writing under the shared pseudonym of A. W. Hart, with the individual authors given credit on the title page.

Other books in each series are being written by an incredible lineup of wordslingers, all writing under the shared pseudonym of A. W. Hart, with the individual authors given credit on the title page.  The first books in each series are available now. More books are set to follow in rapid succession before beginning an alternating monthly release schedule.

The first books in each series are available now. More books are set to follow in rapid succession before beginning an alternating monthly release schedule. These are action-filled tradition Westerns—PG-13 for violence, sex, and language—So, grab your boots and saddles and ride along with us...

These are action-filled tradition Westerns—PG-13 for violence, sex, and language—So, grab your boots and saddles and ride along with us...

Published on October 19, 2019 06:38

October 18, 2019

NORTHWESTERNS—MOUNTIES IN COMMANDO

Published on October 18, 2019 22:54

October 16, 2019

DICK DARING OF THE MOUNTIES (AKA: JIM CANADA)

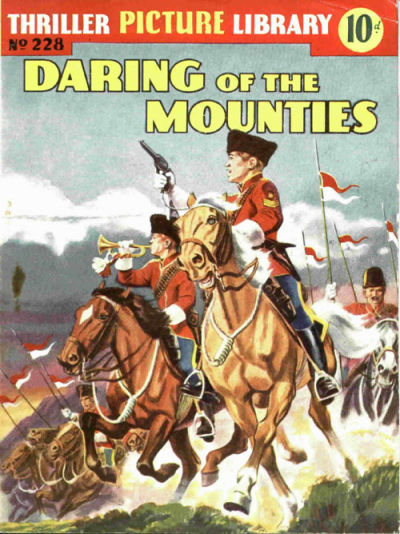

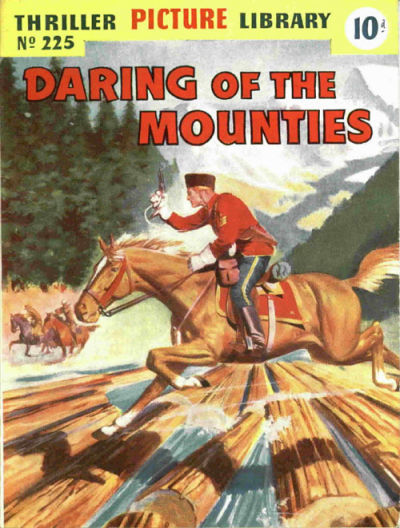

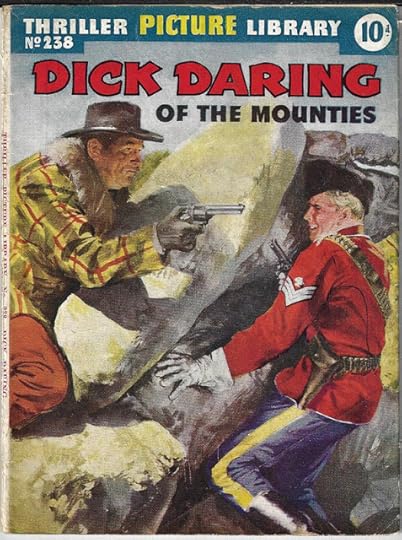

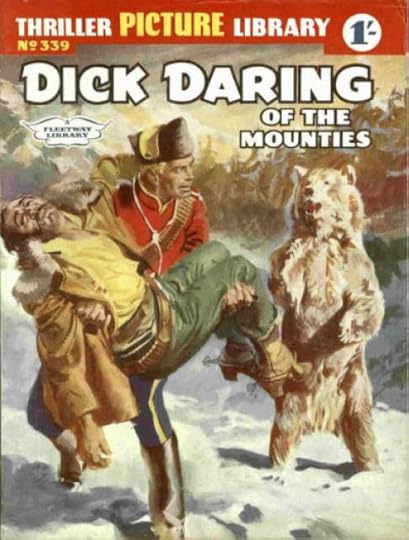

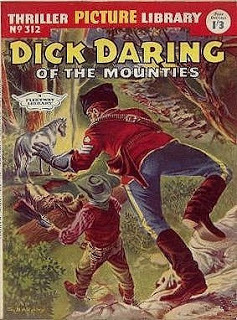

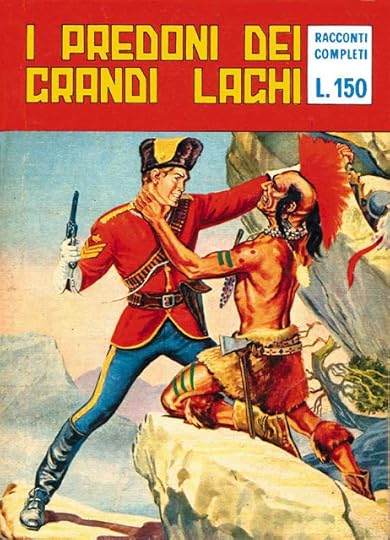

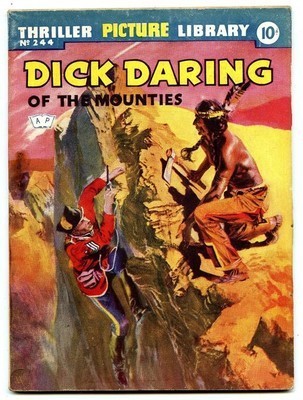

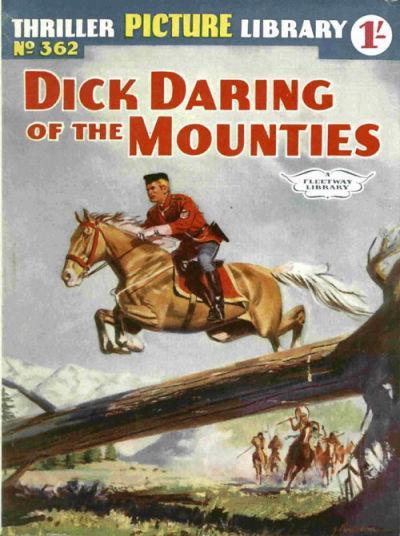

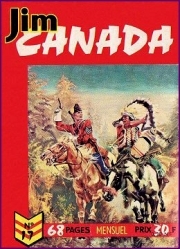

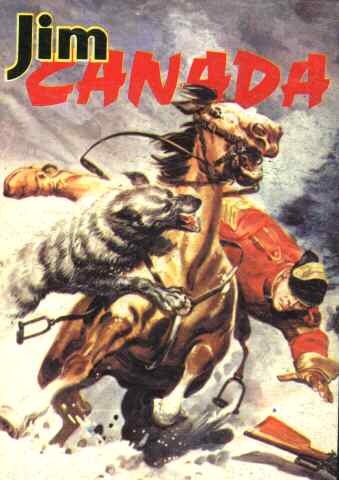

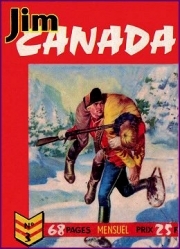

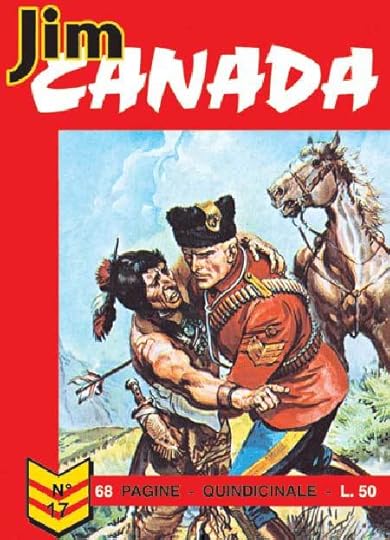

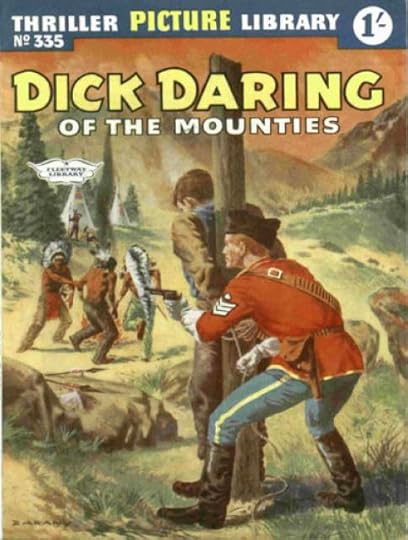

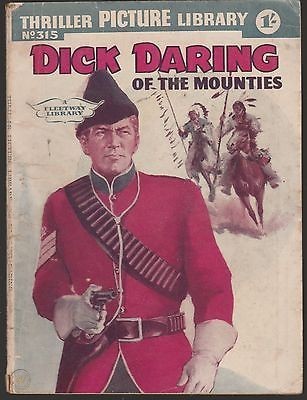

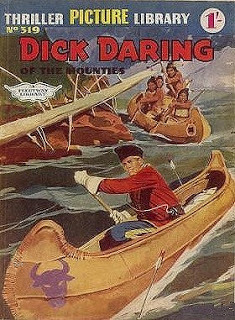

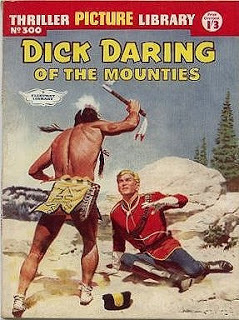

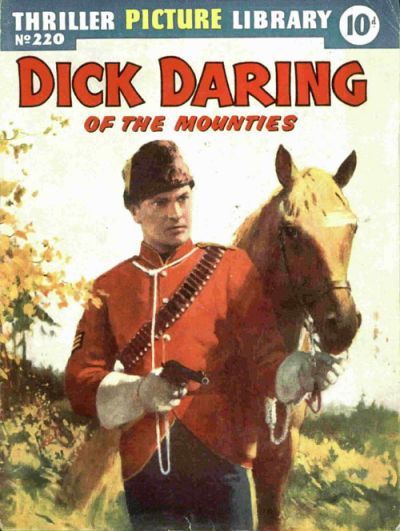

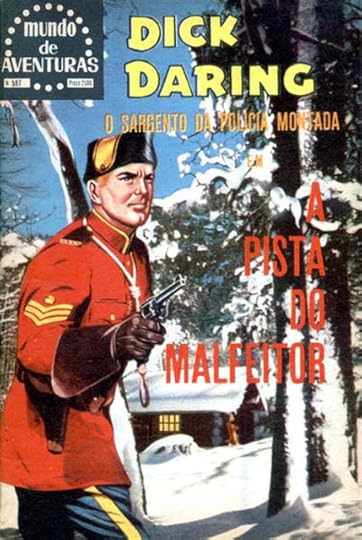

DICK DARINGOF THE MOUNTIES(AKA: JIM CANADA)Thriller Picture Library first appeared in 1951. The 64 page, digest-sized, British comic book began publication on a fortnightly schedule until going weekly in 1955. Like most British comics of the era, Thriller Picture Library sported a color cover with black and white interior art. Originally called Thriller Comics, the zine was later rebranded under its more commonly remembered title, Thriller Picture Library.

DICK DARINGOF THE MOUNTIES(AKA: JIM CANADA)Thriller Picture Library first appeared in 1951. The 64 page, digest-sized, British comic book began publication on a fortnightly schedule until going weekly in 1955. Like most British comics of the era, Thriller Picture Library sported a color cover with black and white interior art. Originally called Thriller Comics, the zine was later rebranded under its more commonly remembered title, Thriller Picture Library. Each issue of Thriller Picture Library told a complete new adventure for a rotating lineup of heroic adventurers. At first, the stories were mainly illustrated versions of classic tales such as The Three Musketeers and The Man In The Iron Mask. Successfully finding a substantial audience, the comic began to feature new original stories based on folk heroes such as Rob Roy, Dick Turpin, Robin Hood and others.

Each issue of Thriller Picture Library told a complete new adventure for a rotating lineup of heroic adventurers. At first, the stories were mainly illustrated versions of classic tales such as The Three Musketeers and The Man In The Iron Mask. Successfully finding a substantial audience, the comic began to feature new original stories based on folk heroes such as Rob Roy, Dick Turpin, Robin Hood and others. During its run its long run, Thriller Picture Library, constantly adjusted its content to mirror changing audience interets. Mysteries, Westerns, sci-fi, and war stories all put in appearances with the pages of Thriller Picture Library. By the time Thriller Picture Library stopped publication with issue #450 in 1963, it was rotating between a list of modern action heroes, secret agents, and pilots.

During its run its long run, Thriller Picture Library, constantly adjusted its content to mirror changing audience interets. Mysteries, Westerns, sci-fi, and war stories all put in appearances with the pages of Thriller Picture Library. By the time Thriller Picture Library stopped publication with issue #450 in 1963, it was rotating between a list of modern action heroes, secret agents, and pilots.

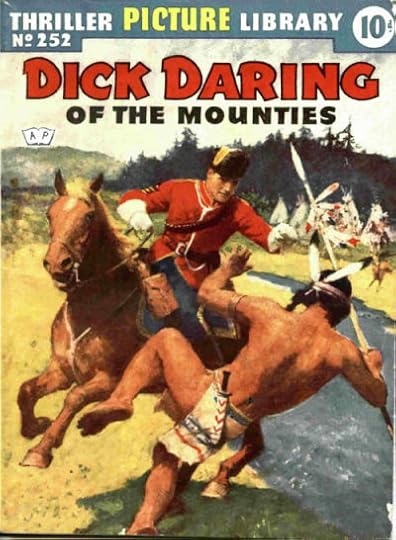

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police had their own Thriller Picture Library hero—Dick Daring of the Mounties. Specifically created for Thriller Picture Library by Reg Bunn, the Scarlet-coated Daring entered the regular rotation of the digest comic's heroes in 1951, starting in Thriller Picture Library's Issue #217. Daring's adventures would continue to run intermittently for over thirty issues through 1961. Michael Moorcock, who would go on to fame as a fantasy and science fiction author, wrote a number of the Dick Daring comic scripts.

RCMP Sergeant Daring was based out of Creek Town in the Yukon Territory. Along with chasing the usual assortment of Northwestern-style criminals, Dick was a friend of the Indians and often help them fight against their oppressors.

RCMP Sergeant Daring was based out of Creek Town in the Yukon Territory. Along with chasing the usual assortment of Northwestern-style criminals, Dick was a friend of the Indians and often help them fight against their oppressors.  Interestingly, Daring is is most often pictured on the covers wearing a muskrat fur Cossack-style wedge hat, which were issued to RCMP troopers along with their traditional and better known wide-brimmed campaign hat.

Interestingly, Daring is is most often pictured on the covers wearing a muskrat fur Cossack-style wedge hat, which were issued to RCMP troopers along with their traditional and better known wide-brimmed campaign hat.

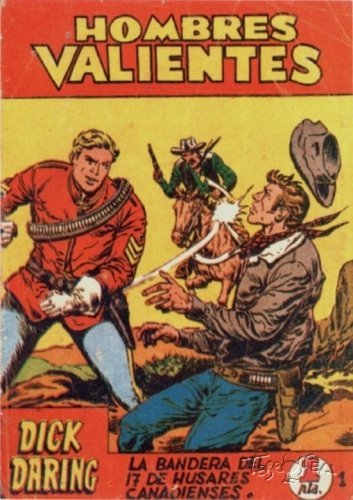

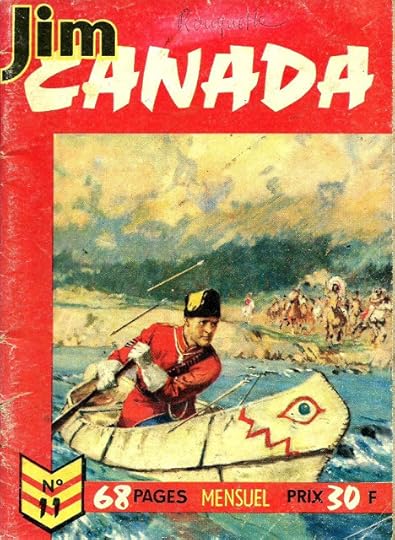

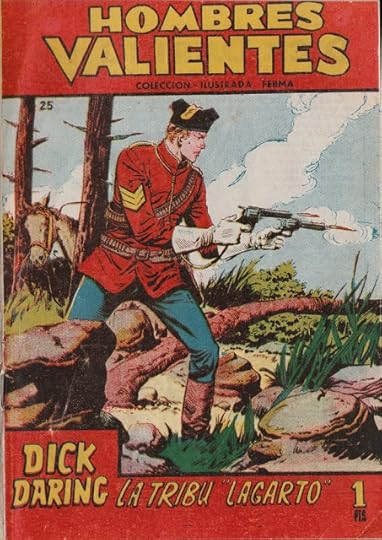

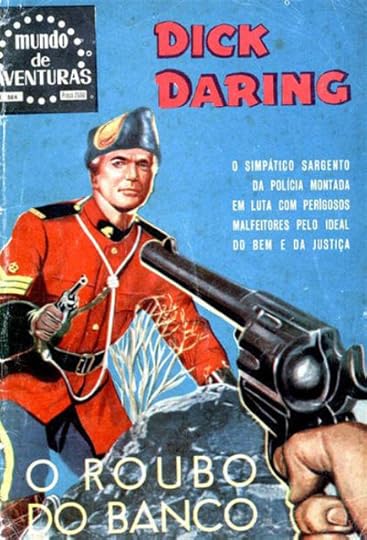

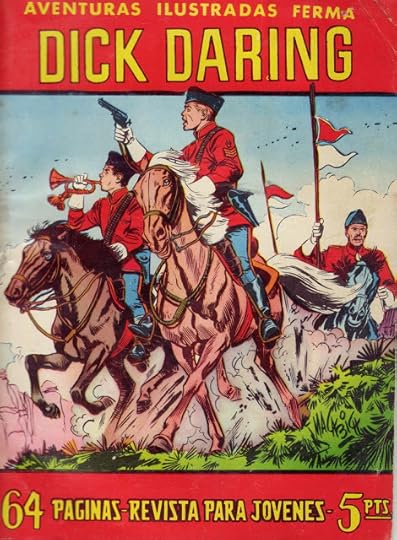

Proving popular with international audiences, Dick Daring of the Mounties found himself translated into a number of European languages, including French, Spanish, and Italian.

Proving popular with international audiences, Dick Daring of the Mounties found himself translated into a number of European languages, including French, Spanish, and Italian. The list of artists on the series reads like an Italian phone book—Sergio Tarquinio, Franco Bignotti, Virgilio Muzzi, Renato Polese, Gallieno Ferri, and Vittorio Cossio. Argentinians Carlos V. Roume and Martin El Salvador also contributed. These artists were instructed to leave the faces of recurring characters blank so Reg Bunn could finish them himself.

The list of artists on the series reads like an Italian phone book—Sergio Tarquinio, Franco Bignotti, Virgilio Muzzi, Renato Polese, Gallieno Ferri, and Vittorio Cossio. Argentinians Carlos V. Roume and Martin El Salvador also contributed. These artists were instructed to leave the faces of recurring characters blank so Reg Bunn could finish them himself. In 1961, Daring was replaced in the pages of Thriller Picture Library by Dogfight Dixon. However, because of a production glitch, a leftover issue of Dick Daring of the Mounties was substituted in, giving the intrepid hero what was supposed to be one last hurrah in issue #362.

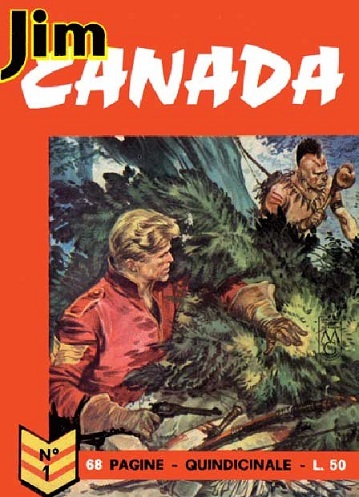

In 1961, Daring was replaced in the pages of Thriller Picture Library by Dogfight Dixon. However, because of a production glitch, a leftover issue of Dick Daring of the Mounties was substituted in, giving the intrepid hero what was supposed to be one last hurrah in issue #362. However, you can't keep a good hero down. When Thriller Picture Library abandoned Daring, his name was changed to Jim Canada when his adventures were picked up by the Italian publishing company Dardo. The new Jim Canada stories were written by Raffaele Garcea with artwork by Giorgio De Gaspari.

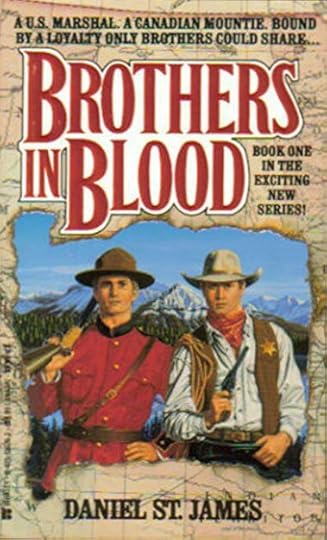

However, you can't keep a good hero down. When Thriller Picture Library abandoned Daring, his name was changed to Jim Canada when his adventures were picked up by the Italian publishing company Dardo. The new Jim Canada stories were written by Raffaele Garcea with artwork by Giorgio De Gaspari. Despite the name change, the character remained a sergeant in the Canadian Royal Mounted Police and continued his quest as a guardian of law and order in the cold and savage Yukon, defending settlers, chasing down dastardly fur thieves and other outlaws, and alternately defending or being chased by indigenous Indians.