Paul Bishop's Blog, page 4

November 29, 2019

THE WORDSLINGER TRAILS—JOHNNY D. BOGGS

THE WORDSLINGER TRAILSJOHNNY D. BOGGS

Johnny D. Boggs is a writer’s writer. He is a professional wordslinger at the top of his trade able to apply his exceptional craft to any literary form. Award winning Western novels, short stories, non-fiction articles, young adult fiction, and more are all within his oeuvre. Since becoming a full-time fiction writer he has won four Spur Awards from the Western Writers of America and a prestigious Western Heritage Wrangler Award.

THE WORDSLINGER TRAILSJOHNNY D. BOGGS

Johnny D. Boggs is a writer’s writer. He is a professional wordslinger at the top of his trade able to apply his exceptional craft to any literary form. Award winning Western novels, short stories, non-fiction articles, young adult fiction, and more are all within his oeuvre. Since becoming a full-time fiction writer he has won four Spur Awards from the Western Writers of America and a prestigious Western Heritage Wrangler Award.

Born in 1962, and growing up on a farm in Timmonsville, South Carolina, Boggs knew he wanted to be a writer at an early age. He also showed an immediate affinity for the business side of writing. Starting in the third grade, Boggs began writing his own stories—featuring archetypical popular characters—and selling them to his classmates. Unexpectedly, his profits outstripped picking peanuts, hanging tobacco, odd-jobs, and other traditional boyhood tasks.

Born in 1962, and growing up on a farm in Timmonsville, South Carolina, Boggs knew he wanted to be a writer at an early age. He also showed an immediate affinity for the business side of writing. Starting in the third grade, Boggs began writing his own stories—featuring archetypical popular characters—and selling them to his classmates. Unexpectedly, his profits outstripped picking peanuts, hanging tobacco, odd-jobs, and other traditional boyhood tasks.

Boggs’ love of the Western genre grew from watching Gunsmoke, The Virginian, and other Western TV shows with his dad. A distant Charleston TV station—which could be watched if his family’s TV antenna was positioned just right—showed a lot of Western movies, including John Wayne Theater on Saturday afternoons. It also enabled him to watch and rewatch Gunfight at the OK Corral uncountable times. The West was also “…a long, long way from the swamps and tobacco fields of South Carolina,” which to its allure.

Boggs’ love of the Western genre grew from watching Gunsmoke, The Virginian, and other Western TV shows with his dad. A distant Charleston TV station—which could be watched if his family’s TV antenna was positioned just right—showed a lot of Western movies, including John Wayne Theater on Saturday afternoons. It also enabled him to watch and rewatch Gunfight at the OK Corral uncountable times. The West was also “…a long, long way from the swamps and tobacco fields of South Carolina,” which to its allure.

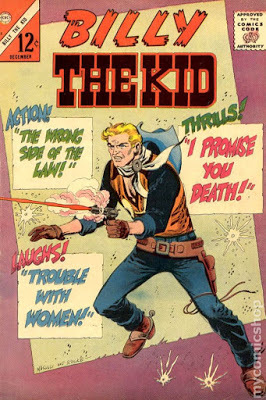

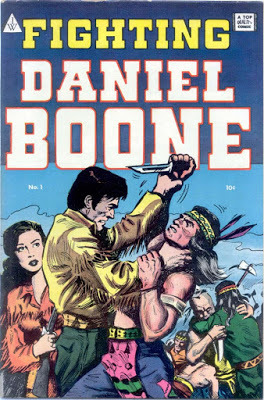

His original love of the six-gun genre was further nurtured by comic books featuring Daniel Boone and Billy the Kid, which he read until they were tattered and frayed. When he was older, the Western section of nearby Ray’s Novel Shop provided fodder for his fertile imagination. The stories stirred something deep in his psyche and he began to see the West as much more than a physical location. For Boggs, the West encompassed an ideal with the power to induce a spiritual connection with readers.

His original love of the six-gun genre was further nurtured by comic books featuring Daniel Boone and Billy the Kid, which he read until they were tattered and frayed. When he was older, the Western section of nearby Ray’s Novel Shop provided fodder for his fertile imagination. The stories stirred something deep in his psyche and he began to see the West as much more than a physical location. For Boggs, the West encompassed an ideal with the power to induce a spiritual connection with readers.

While studying journalism at the University of Carolina, Boggs also immersed himself in film and theatre courses, fueling his passion for film history. Discussing the accuracy of Western movies, Boggs contends, “Films are supposed to entertain…When I watch a movie, I want to be entertained. My Darling Clementine, which got the year of the gunfight at the O.K. Corral wrong, entertains. I have to admit Chisum is a guilty pleasure. I even like They Died With Their Boots On. But Son of the Morning Star and Gods and Generals, which got the history right, failed at entertainment.”

While studying journalism at the University of Carolina, Boggs also immersed himself in film and theatre courses, fueling his passion for film history. Discussing the accuracy of Western movies, Boggs contends, “Films are supposed to entertain…When I watch a movie, I want to be entertained. My Darling Clementine, which got the year of the gunfight at the O.K. Corral wrong, entertains. I have to admit Chisum is a guilty pleasure. I even like They Died With Their Boots On. But Son of the Morning Star and Gods and Generals, which got the history right, failed at entertainment.”

Obtaining his journalism degree in 1984, his literary ambitions guided him to follow Horace Greeley’s oft-quoted advice to go west. He ended up in Texas where he spent fifteen years working for the Dallas Times Herald and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, becoming an assistant sports editor for both publications. Eventually, he burned out on the Texas weather, the Dallas traffic, and big city crime. He joked to his wife about moving to New Mexico to get away from it all. She, however, took him seriously and went all in on the idea. Several months later, the couple packed up and headed for Santa Fe, were they have resided ever since.

Obtaining his journalism degree in 1984, his literary ambitions guided him to follow Horace Greeley’s oft-quoted advice to go west. He ended up in Texas where he spent fifteen years working for the Dallas Times Herald and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, becoming an assistant sports editor for both publications. Eventually, he burned out on the Texas weather, the Dallas traffic, and big city crime. He joked to his wife about moving to New Mexico to get away from it all. She, however, took him seriously and went all in on the idea. Several months later, the couple packed up and headed for Santa Fe, were they have resided ever since.

In moving to Santa Fe, Boggs didn’t just leave Texas behind. He also left behind the daily grind of journalism, turning to writing novels and articles for his livelihood… “I was doing what I want to do and, for the most part, writing what I want to write, even if I might sometimes wonder how I’ll pay the bills.”

In moving to Santa Fe, Boggs didn’t just leave Texas behind. He also left behind the daily grind of journalism, turning to writing novels and articles for his livelihood… “I was doing what I want to do and, for the most part, writing what I want to write, even if I might sometimes wonder how I’ll pay the bills.”

His love for Westerns remained strong, but siren song of the television and movie version of the Wild West began to fade. He replaced it with a fascination for the gritty reality of the American West, its true history and real life characters.

While staking claim to Mark Twain as his favorite writer, Boggs also found inspiration in the works of Jack Schaefer (Shane) and Montana’s most successful Western writer—Dorothy M. Johnson. Boggs considers both authors literary fiction masters who just happened to write about the West.

Johnson was known as a witty, gritty, little bobcat of a woman. Refreshingly, her Western characters were not invincible. In stories like The Hanging Tree, A Man Called Horse, and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (all of which were made into movies), Johnson conceived the narratives by questioning the Western myth of manly bravado—“I asked myself, what if one of these big bold gunmen who are having the traditional walkdown is not fearless, and what if he can’t even shoot. Then what have you got?”

Johnson was known as a witty, gritty, little bobcat of a woman. Refreshingly, her Western characters were not invincible. In stories like The Hanging Tree, A Man Called Horse, and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (all of which were made into movies), Johnson conceived the narratives by questioning the Western myth of manly bravado—“I asked myself, what if one of these big bold gunmen who are having the traditional walkdown is not fearless, and what if he can’t even shoot. Then what have you got?”

Jack Schaefer wrote other novels, but the giant shadow of Shane eclipses them all. In creating the character from his most famous work, Schaefer devises a stone killer who finds himself suffering in anguish over the struggle to do right when his every instinct wants to do otherwise. This explorations of human mortality evokes from the reader admiration, respect, and finally adoration for a man trying to save himself from his own evil. Like the works of Dorothy M. Johnson, Shane is a Western, but it eclipses the genre in a way few other novels can accomplish.

Jack Schaefer wrote other novels, but the giant shadow of Shane eclipses them all. In creating the character from his most famous work, Schaefer devises a stone killer who finds himself suffering in anguish over the struggle to do right when his every instinct wants to do otherwise. This explorations of human mortality evokes from the reader admiration, respect, and finally adoration for a man trying to save himself from his own evil. Like the works of Dorothy M. Johnson, Shane is a Western, but it eclipses the genre in a way few other novels can accomplish.

These strong influences led Boggs to create a West based on reality, but interwoven with a mythical consciousness. Rooted in truth, his Westerns connect to genre readers on an emotional level—speaking loudly to those who are fascinated with the real West, but sill love the traditional tropes of Western fiction. Of his approach, Boggs maintains, “Facts can be confining. In fiction, my imagination can take over…I try to make my novels fairly truthful, but I always say, don’t quote me in your term paper.”

These strong influences led Boggs to create a West based on reality, but interwoven with a mythical consciousness. Rooted in truth, his Westerns connect to genre readers on an emotional level—speaking loudly to those who are fascinated with the real West, but sill love the traditional tropes of Western fiction. Of his approach, Boggs maintains, “Facts can be confining. In fiction, my imagination can take over…I try to make my novels fairly truthful, but I always say, don’t quote me in your term paper.”

Boggs is the arch-enemy of editors who put try to force physical and cultural restrictions on Westerns. “What draws me into writing a novel or short story are the characters and the land…I don’t like fences and I don’t like boundaries. I like to write about what I want to write about.”

One of Boggs most accomplished novels is Northfield. In it, Boggs skillfully weaves twenty-three first-person viewpoints telling the tale of the James-Younger gang’s attempt to rob the First National Bank of Northfield, and the disastrous consequences of the aftermath. Juggling the multiple viewpoints in Northfield proved a major challenge, but one Boggs gladly accepted... ”I’d read and seen so much hogwash about what happened in Northfield, I wanted to tell the story as accurately as possible.”

One of Boggs most accomplished novels is Northfield. In it, Boggs skillfully weaves twenty-three first-person viewpoints telling the tale of the James-Younger gang’s attempt to rob the First National Bank of Northfield, and the disastrous consequences of the aftermath. Juggling the multiple viewpoints in Northfield proved a major challenge, but one Boggs gladly accepted... ”I’d read and seen so much hogwash about what happened in Northfield, I wanted to tell the story as accurately as possible.” To fill in historical gaps, Boggs gives voice not only to the major outlaws, but also to the often overlooked minor characters. The words of these real people—ordinary farmers, business owners, members of the James and Younger families, and the forces of the law—complete the story as accurately as it can be portrayed while still telling a rousing saga of the West.

Boggs has a great appreciation for the history of the West. This extends far beyond Main Street showdowns, crooked poker games, and land disputes. He looks for the uncommon and the overlooked.

In his novel Camp Ford, Boggs interwines the Civil War, the West, and baseball. With its theme of Union soldiers introducing baseball to various parts of the country during the Civil War, Camp Ford is based on historical fact. Chronicling the amazing changes America underwent during the span of one man's life, Camp Ford starts with the 1946 World Series as 99-year-old Win MacNaughton recalls the greatest baseball game of his entire life, and the events leading to that 1865 contest between a ragtag collection of Union prisoners of war against a squad of Confederate prison guards. Camp Ford is a Western, but it is filled with pathos, friendship, honor, betrayal, and a sly humor, which make it so much more than a simple six-gun shoot ‘em up.

In his novel Camp Ford, Boggs interwines the Civil War, the West, and baseball. With its theme of Union soldiers introducing baseball to various parts of the country during the Civil War, Camp Ford is based on historical fact. Chronicling the amazing changes America underwent during the span of one man's life, Camp Ford starts with the 1946 World Series as 99-year-old Win MacNaughton recalls the greatest baseball game of his entire life, and the events leading to that 1865 contest between a ragtag collection of Union prisoners of war against a squad of Confederate prison guards. Camp Ford is a Western, but it is filled with pathos, friendship, honor, betrayal, and a sly humor, which make it so much more than a simple six-gun shoot ‘em up.

While both Northfield and Camp Ford show Boggs’ penchant for historically based storytelling, he also writes excellent straight ahead action/adventure style Westerns. The historical research is still there in the fine details, but the action is front and center.

In the opening scene of Valley of Fire, a nun and an outlaw walk into a jail...Okay, the outlaw walked in before the nun got there, but they definitely leave together in a blaze of violence. Their actions upset a large contingent of unsavory characters, ensuring the relentless action never flags. While not exactly a sister of mercy, the nun is really a nun and she makes sure there is hell to pay before the gold hidden in the Valley of Fire can be recovered.

In the opening scene of Valley of Fire, a nun and an outlaw walk into a jail...Okay, the outlaw walked in before the nun got there, but they definitely leave together in a blaze of violence. Their actions upset a large contingent of unsavory characters, ensuring the relentless action never flags. While not exactly a sister of mercy, the nun is really a nun and she makes sure there is hell to pay before the gold hidden in the Valley of Fire can be recovered.

Boggs and other modern Western wordslingers are ensuring the genre continues to thrive as a vibrant style of storytelling. As Boggs himself puts it, “I think Westerns have always been the ugly stepchild when it comes to genre fiction, but it’s still there despite countless epithets and death songs over the past several decades. People still like those stories...Writing Westerns is keeping me busier than ever...”

Published on November 29, 2019 06:37

November 28, 2019

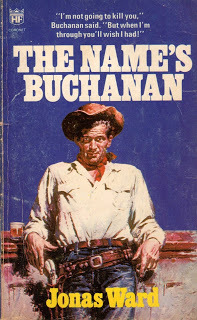

WESTERN NOVELS—THE NAME’S BUCHANAN

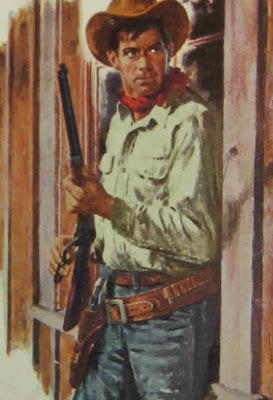

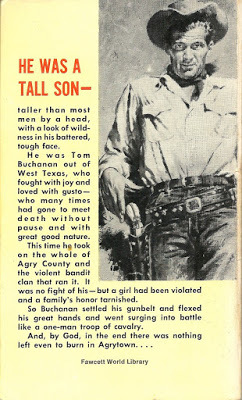

WESTERN NOVELSTHE NAME’S BUCHANAN Drifting back across the Mexican border into Texas, the disillusioned Buchanan (his first name, Tom, is rarely used) is happy to be home. He’s returning after two years of violence working as a hired gun for a man he thought was an idealistic revolutionary, but who turned out to be as corrupt as the brutal forces of the Mexican government they were fighting against.

WESTERN NOVELSTHE NAME’S BUCHANAN Drifting back across the Mexican border into Texas, the disillusioned Buchanan (his first name, Tom, is rarely used) is happy to be home. He’s returning after two years of violence working as a hired gun for a man he thought was an idealistic revolutionary, but who turned out to be as corrupt as the brutal forces of the Mexican government they were fighting against.  All Buchanan wants is a soft bed and a good steak. What he gets is a border town full of trouble—gun trouble. On the trail to the town of Agrytown, run roughshod by the backstabbing Agry family, Buchanan rescues a young girl who has been raped and left for dead.

All Buchanan wants is a soft bed and a good steak. What he gets is a border town full of trouble—gun trouble. On the trail to the town of Agrytown, run roughshod by the backstabbing Agry family, Buchanan rescues a young girl who has been raped and left for dead.Restoring the girl to her family, he finds himself swept up into the middle of a violent clash between two powerful dynasties, one on either side of the U.S./Mexican border. Trying to do the right thing, Buchanan has to rely on his fists and his guns to save the victim’s hell-bent on revenge brother, who has provoked the wrath of the deadly Agrys.

The classic Western anti-hero—a man with a troubled past trying to maintain his dented code of ethics by never turning away from an underdog who needs help—Buchanan won’t sell his guns for any price, will never shoot a man in the back, and will never cheat or be in debt to anyone.

The classic Western anti-hero—a man with a troubled past trying to maintain his dented code of ethics by never turning away from an underdog who needs help—Buchanan won’t sell his guns for any price, will never shoot a man in the back, and will never cheat or be in debt to anyone.Jonas Ward was the pseudonymous byline for the Buchanan series, which was created by William Ard. A bestselling hardboiled writer, Ard’s approach to the Buchanan series was to reinvent his tough urban crime novels as Westerns.

The Name’s Buchanan is essentially a six-guns and spurs rewrite of Ard’s powerful crime novel Hell Is a City. Ard wrote five Buchanan Westerns in the same hardboiled-tinged style. He was working on a sixth when he died of cancer at the age of thirty-seven in 1960. Buchanan, however, survived the death of his creator, with other writers commissioned to keep the series going.

The Name’s Buchanan is essentially a six-guns and spurs rewrite of Ard’s powerful crime novel Hell Is a City. Ard wrote five Buchanan Westerns in the same hardboiled-tinged style. He was working on a sixth when he died of cancer at the age of thirty-seven in 1960. Buchanan, however, survived the death of his creator, with other writers commissioned to keep the series going. The tall, powerful, Western loner known as Buchanan was the original Jack Reacher. Ard plunks his hero down into the middle of violence and trouble—range wars, town takeovers, land grabs, or any other situation quickly leading to gunplay and a chance for Buchanan to unleash his boulder-sized fists.

The tall, powerful, Western loner known as Buchanan was the original Jack Reacher. Ard plunks his hero down into the middle of violence and trouble—range wars, town takeovers, land grabs, or any other situation quickly leading to gunplay and a chance for Buchanan to unleash his boulder-sized fists. There is always an abundance of shapely widows, daughters and dancehall girls to keep Buchanan from getting bored. The mean streets of the city have been replaced by dusty main streets, and the private eye by the itinerant gunslinger, but the code of the white knight remains the same.

Using the Jonas Ward pseudonym, two distinguished novelists contributed books to the Buchanan series during the early days of their careers. Science fiction stalwart Robert Silverberg competed the sixth book in the series—the manuscript Ard was working on when he died—Buchanan on the Prod. Thriller writer Brian Garfield, of Death Wish fame, wrote the seventh book in the series, Buchanan’s Gun. Well-known Western writer William R. Cox would then take over the series for sixteen more Buchanan adventures before the series ended in 1984.

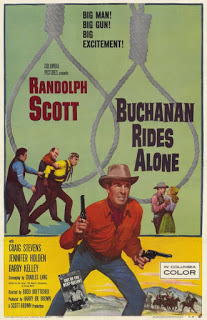

Using the Jonas Ward pseudonym, two distinguished novelists contributed books to the Buchanan series during the early days of their careers. Science fiction stalwart Robert Silverberg competed the sixth book in the series—the manuscript Ard was working on when he died—Buchanan on the Prod. Thriller writer Brian Garfield, of Death Wish fame, wrote the seventh book in the series, Buchanan’s Gun. Well-known Western writer William R. Cox would then take over the series for sixteen more Buchanan adventures before the series ended in 1984. In the movie Buchanan Rides Alone (1958), which was based on The Name’s Buchanan, Randolph Scott is perfectly cast as the hero—rugged, yet laconic. The movie marked the first of a seven-film collaboration between Scott, director Budd Boetticher, producer Harry Joe Brown, and screenwriter Burt Kennedy. This first film is not technically part of what is referred to as the Ranown Cycle as it was produced by a studio, However, it is always included in the series as it was the start of their amazing partnership.

In the movie Buchanan Rides Alone (1958), which was based on The Name’s Buchanan, Randolph Scott is perfectly cast as the hero—rugged, yet laconic. The movie marked the first of a seven-film collaboration between Scott, director Budd Boetticher, producer Harry Joe Brown, and screenwriter Burt Kennedy. This first film is not technically part of what is referred to as the Ranown Cycle as it was produced by a studio, However, it is always included in the series as it was the start of their amazing partnership.

Published on November 28, 2019 22:48

THE COLLECTION FROM U.N.C.L.E.

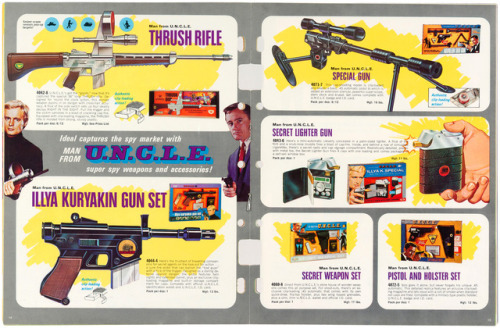

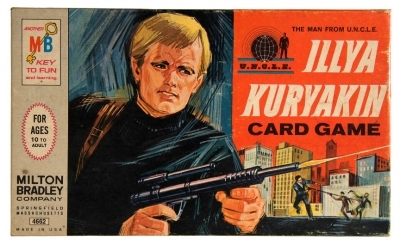

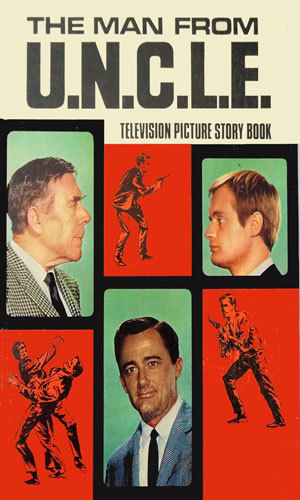

THE COLLECTION FROM U.N.C.L.E.In 1964, The Man From U.N.C.L.E. premiered on NBC and began a worldwide phenomenon. I was ten years old and as swept up in the fervor as anyone else—maybe more than most as there is a direct link between the show and my thirty five year career with the LAPD. Watching the show, I didn’t see myself becoming a spy, but I did feel becoming a police detective was possible. I told my parents then that I was going to become a cop and I never grew out of the notion.

THE COLLECTION FROM U.N.C.L.E.In 1964, The Man From U.N.C.L.E. premiered on NBC and began a worldwide phenomenon. I was ten years old and as swept up in the fervor as anyone else—maybe more than most as there is a direct link between the show and my thirty five year career with the LAPD. Watching the show, I didn’t see myself becoming a spy, but I did feel becoming a police detective was possible. I told my parents then that I was going to become a cop and I never grew out of the notion.  Many years later, I noticed David McCallum sitting with his wife in a small British tea room in Santa Monica where I was having lunch. For the uninitiated, McCallum played Illya Kuryakin—one of the two U.N.C.L.E. (United Network Command for Law and Enforcement) agents who saved the world each week from the threat of the evil organization called T.H.R.U.S.H. (Technological Hierarchy for the Removal of Undesirables and the Subjugation of Humanity).

Many years later, I noticed David McCallum sitting with his wife in a small British tea room in Santa Monica where I was having lunch. For the uninitiated, McCallum played Illya Kuryakin—one of the two U.N.C.L.E. (United Network Command for Law and Enforcement) agents who saved the world each week from the threat of the evil organization called T.H.R.U.S.H. (Technological Hierarchy for the Removal of Undesirables and the Subjugation of Humanity).  As McCallum and his wife were paying their check, I approached respectfully and told McCallum how much he (through his character) had influenced my life and choice of law enforcement as a career. McCallum gave me a shy smile and told me it was something he was often told and was honored his character had been such a positive role model.

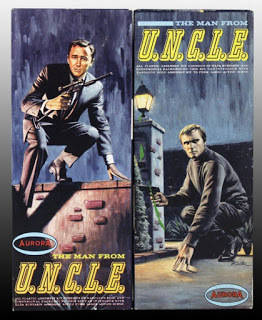

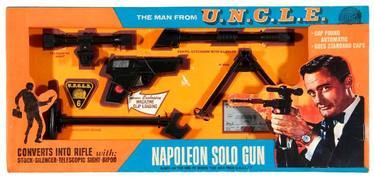

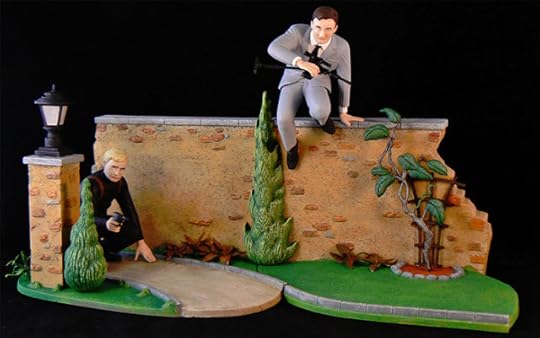

As McCallum and his wife were paying their check, I approached respectfully and told McCallum how much he (through his character) had influenced my life and choice of law enforcement as a career. McCallum gave me a shy smile and told me it was something he was often told and was honored his character had been such a positive role model. Now over fifty years since U.N.C.L.E.’s debut, my collection of the many U.N.C.L.E. novels, magazines, and comics still hold a special place in my library. The show had also spawned an avalanche of tie-in merchandising—everything from multiple guns, to attaché cases filled with spy gear, to board games, puzzles, toy cars, pinball games, action figures, plastic Aurora models, lunch boxes, and uncountable mother items with the uncle logo slapped on them.

Now over fifty years since U.N.C.L.E.’s debut, my collection of the many U.N.C.L.E. novels, magazines, and comics still hold a special place in my library. The show had also spawned an avalanche of tie-in merchandising—everything from multiple guns, to attaché cases filled with spy gear, to board games, puzzles, toy cars, pinball games, action figures, plastic Aurora models, lunch boxes, and uncountable mother items with the uncle logo slapped on them. It is estimated, The Man From U.N.C.L.E. produced far more tie-in products during the sixties than any other television show of its day. At one time or another, I was in possession of many of those items, but eventually the only things I retained were the related publications I mentioned above as still being in my library.

When I saw the pre-order information on Amazon for The Man From U.N.C.L.E. Collectibles by John Buss, I instantly clicked the buy button and sat back in anticipation of its actual publication. I’m definitely the target audience for this type of reference work, but I did have a few reservations. These weren’t enough to stop me from buying the book, but I’d been disappointed before by similar publications.

When I saw the pre-order information on Amazon for The Man From U.N.C.L.E. Collectibles by John Buss, I instantly clicked the buy button and sat back in anticipation of its actual publication. I’m definitely the target audience for this type of reference work, but I did have a few reservations. These weren’t enough to stop me from buying the book, but I’d been disappointed before by similar publications.  Many of these types of publishing efforts suffer from poor production values, poor editing, and poor research. When The publication date for The Man From U.N.C.L.E. Collectibles came and went without the book appearing, and then continued to be delayed, my hopes for the quality of the publication flagged.When the publication finally did arrive in my mailbox, my initial impression was not helped by the unspectacular cover art chosen by the publisher. However, I was soon to reassess my knee jerk reaction and rapidly became delighted with the book and its content.

Many of these types of publishing efforts suffer from poor production values, poor editing, and poor research. When The publication date for The Man From U.N.C.L.E. Collectibles came and went without the book appearing, and then continued to be delayed, my hopes for the quality of the publication flagged.When the publication finally did arrive in my mailbox, my initial impression was not helped by the unspectacular cover art chosen by the publisher. However, I was soon to reassess my knee jerk reaction and rapidly became delighted with the book and its content.

The book itself is tightly bound and produced on heavy quality paper giving a pleasant heft to the books 96 pages. The quality paper is also a bright enough white to make the sharply focused photographs of the tie-in products pop off the page. While the book does not hold itself out as the complete collection of U.N.C.L.E. tie-in merchandising, it goes well beyond the traditional items to provide a satisfying array.

The book itself is tightly bound and produced on heavy quality paper giving a pleasant heft to the books 96 pages. The quality paper is also a bright enough white to make the sharply focused photographs of the tie-in products pop off the page. While the book does not hold itself out as the complete collection of U.N.C.L.E. tie-in merchandising, it goes well beyond the traditional items to provide a satisfying array. The book is well edited with nary a stray typo on display (a prodigious feat) and the writing itself is tight and professional. I found the presented information interesting, informative, and well researched. Author John Buss clearly knows and loves what he is writing about and this is clearly conveyed to the reader.

The book is well edited with nary a stray typo on display (a prodigious feat) and the writing itself is tight and professional. I found the presented information interesting, informative, and well researched. Author John Buss clearly knows and loves what he is writing about and this is clearly conveyed to the reader.I read straight through from start to finish in two happy sessions, able to immerse myself in the nostalgia without being distracted by the flaws of so many similar publications. This is a top notch product, which will be enjoyed by any U.N.C.L.E. fan, and an important historical reference preserving the history of one of the most influential television shows of our time.

The best kudo I can bestow on The Man From U.N.C.L.E. Collectibles is my immediate desire to read a sequel, and another sequel, and another...

THE MAN FROM U.N.C.L.E. COLLECTIBLESJOHN BUSS The Man from U.N.C.L.E. was American television at its best. In the sixties, spy series just didn't come any cooler than this. Almost a direct result of the success of Bond in the cinemas, this series spawned a whole wave of copycat TV shows and its influence is still being felt today. The recent Kingsman films/comics owe more than a passing nod to the show for inspiration. A remarkable array of different products were issued in connection with this series – everything from bubble gum to wristwatches. Few other shows at this time came close to the range of products issued. There were quite possibly more U.N.C.L.E. products issued in America alone, during the sixties, than for any other TV series being produced at that time. In this book you will find a vast array of those items.

THE MAN FROM U.N.C.L.E. COLLECTIBLESJOHN BUSS The Man from U.N.C.L.E. was American television at its best. In the sixties, spy series just didn't come any cooler than this. Almost a direct result of the success of Bond in the cinemas, this series spawned a whole wave of copycat TV shows and its influence is still being felt today. The recent Kingsman films/comics owe more than a passing nod to the show for inspiration. A remarkable array of different products were issued in connection with this series – everything from bubble gum to wristwatches. Few other shows at this time came close to the range of products issued. There were quite possibly more U.N.C.L.E. products issued in America alone, during the sixties, than for any other TV series being produced at that time. In this book you will find a vast array of those items.

Published on November 28, 2019 11:19

November 8, 2019

GOLF NOIR–THE BIG TOUR

GOLF NOIR–THE BIG TOUR Recently, in search of something else (which is usually how these things happen), I found instead my copy of this diamond-hard gem of a novel, which was over due for a reread.

GOLF NOIR–THE BIG TOUR Recently, in search of something else (which is usually how these things happen), I found instead my copy of this diamond-hard gem of a novel, which was over due for a reread.As things would have it, I read about golf far more than I play it. In fact, don’t actually play golf. Instead, I play 'at' golf. Once or twice a year, I wack a ball around eighteen holes with a friend, never keeping score and simply enjoying the beauty of being on a golf course.

However, I have over a hundred sports pulps containing golf stories from the ‘30s and ‘40s, which are all pretty cool, and I have over fifty golf fiction titles on my bookshelves opposite my similar collection of boxing fiction. If there is a new golf novel published, chances are I'll buy it and read it.

That said, golf novels usually fall into three categories–sharp-tongued humor fests featuring wacky characters and wackier situations (usually written by Dan Jenkins or Mike Lupica, both of whom can make me laugh out loud), smalzy, mystical quests seeking to provide salvation through golf (think The Legend Of Bagger Vance), or attempts to cross the golf novel with the mystery genre, which are rarely able to serve both masters (there are a few exceptions, in particular, Keith Miles’ Alan Saxon novels).

When I read Robert Upton’s first golf mystery, Dead On The Stick (the second in his Amos McGuffin private eye tales), I found it mildly amusing, but nothing more than one of the neither fish nor fowl golf mysteries.

When I read Robert Upton’s first golf mystery, Dead On The Stick (the second in his Amos McGuffin private eye tales), I found it mildly amusing, but nothing more than one of the neither fish nor fowl golf mysteries. Fortunately, Upton’s standalone novel, The Big Tour, is something completely different–the first golf noir novel, a cocaine fueled lightening jag into the heart of one man's darkness.

The difference in the two books is remarkable. One is a lightweight, disposable mystery, forgotten immediately upon turning the final page. The other is a classic example of hardboiled literature, which I've thought about often after reading it. It was as if Upton went to bed as Agatha Christie and woke up as Cornell Woolrich.

By never letting his characters take the easy way out, and by forcing them to experience the consequences of their actions, Upton drags us over a crude eighteen hole course of betrayal and despair in a foursome with Jim Thompson, David Goodis, and James M. Cain–you just know bad things are going to happen.

Don't expect sportsmanship and Rockyesque endings here–this is a wild ride through the rough where you bet with you life and and every club shaft in your bag is a serpent in disguise.

THE BIG TOURThis is not your parents' golf game...In the hard-driving world of professional golf, even a golden boy must learn to win...Duff Colhane has just won his first professional golf tournament. It should be the celebration night of his young life. But he'll be spending it in Miami Federal jail.

THE BIG TOURThis is not your parents' golf game...In the hard-driving world of professional golf, even a golden boy must learn to win...Duff Colhane has just won his first professional golf tournament. It should be the celebration night of his young life. But he'll be spending it in Miami Federal jail.

Son of a barroom-brawling Montauk fisherman, Duff came across as a gentleman born to wealth and privilege. A brash, cocky golden boy and darling of the media they compared to Nicklaus. Golf was his greatest pleasure in life, the one thing he did perfectlyly, a poor boy’s ticket out–pure. Until he saw it played like a rigged game on grass where the only rule was not getting caught and big money was for the taking.

But after a golf lesson Vegas Mob-style all but shatters his pro dreams, Duff struggles desperately to regain the old form only he believes he can recapture. An unscrupulous Dr. Feelgood prescribes a witches’ brew of performance-enhancing drugs, and Duff is bankrolled by his high school sweetheart–a model with no portfolio but plenty of cash and cocaine and some very dangerous friends. If drugs don’t put an end to Duff–she and the Feds will...

Published on November 08, 2019 23:17

November 7, 2019

RACING WITH BIKES IN WORDS AND ON FILM

RACING WITH BIKESIN WORDS AND ON FILM Competitive cycling has been the arena for a number of successful sports mysteries. The latest of these is a terrific translation of Mexican author Jorge Zepeda Patterson's The Black Jersey set amidst the Tour de France.

RACING WITH BIKESIN WORDS AND ON FILM Competitive cycling has been the arena for a number of successful sports mysteries. The latest of these is a terrific translation of Mexican author Jorge Zepeda Patterson's The Black Jersey set amidst the Tour de France.With 2019's real Tour de France crowning the first ever Colombian race winner, Egan Bernal, Jorge Zepeda Patterson is not only timely but somewhat prescient with his Agatha Christie style murder mystery played out against the deadly pursuit of the Tour's coveted yellow jersey.

Marc Moreau, a professional cyclist with a military past, is part of a top Tour de France team led by his best friend, an American star favored to win the current Tour. But the competition takes a dark turn when racers begin to drop out in a series of violent accidents. But as the victim count rises, the number of potential murderers–and potential champions–dwindles.

Marc Moreau, a professional cyclist with a military past, is part of a top Tour de France team led by his best friend, an American star favored to win the current Tour. But the competition takes a dark turn when racers begin to drop out in a series of violent accidents. But as the victim count rises, the number of potential murderers–and potential champions–dwindles. By allowing his prodigious knowledge of bike racing to keep the story moving and tie together the non-racing scenes needed to support the mystery, Patterson pulls off the balancing act inherent in the ratio of sport to mystery (and visa-versa) in The Black Jersey, which is the downfall of the majority of sports mysteries.

However, while the central mystery in The Black Jersey is solid (despite the de rigor least likely suspect scenario) and does have a resolution tied directly to the Tour de France, I was far more fascinated by Patterson's insider take on the tour, which raises the novel above the quagmire. The cool stuff I was learning about bike racing and the Tour itself was what kept me turning the pages...actually, hearing to the pages zip by as I listen to the fantastic audio version of the book.

The Black Jersey left me feeling inspired once again by the Tour De France speeding recklessly through the French countryside with all its accompanying hoopla, crashes, and feats of almost inhuman endurance. As a result, I felt prompted to visit my bookshelves and check on my favorite cycling fiction as well as the DVDs of my favorite cycling films.

The Black Jersey left me feeling inspired once again by the Tour De France speeding recklessly through the French countryside with all its accompanying hoopla, crashes, and feats of almost inhuman endurance. As a result, I felt prompted to visit my bookshelves and check on my favorite cycling fiction as well as the DVDs of my favorite cycling films. Not all of these titles revolve around the Tour de France, but each brings out the reality, agony, and determination of cycling’s two-wheeled speed demons.

Taking the movies first, I have to give my top vote to 1985’s American Flyers. The film stars Kevin Costner as a cycling sports physician with a secret who persuades his younger brother to train with him for a three-day bicycle race across the Rocky Mountains known as The Hell of the West. The racing scenes are well shot and the bonding relationship between the two brothers is worth the price of admission. As in most successful sports films, prepare to cheer while shedding a tear.

1979’s Academy Award winning Breaking Away has obviously garnered more than its share of acclaim. However, this tale of a hardscrabble kid obsessed with Italian bike racers, and the small town clash between blue collar cutters and the much more affluent Indiana University students, is still a delight. If you haven’t seen it, or haven’t seen it in a while, it's time to add it to your Netflix’s queue.

1979’s Academy Award winning Breaking Away has obviously garnered more than its share of acclaim. However, this tale of a hardscrabble kid obsessed with Italian bike racers, and the small town clash between blue collar cutters and the much more affluent Indiana University students, is still a delight. If you haven’t seen it, or haven’t seen it in a while, it's time to add it to your Netflix’s queue. My favorite Sherlock, Jonny Lee Miller, gets his cycling groove on in 2006’s The Flying Scotsman. Mentioning Jonny Lee Miller and eccentric in the same paragraph is perhaps redundant, but the film is based on the true story of the eccentric Graham Obree who rose above a severely abusive childhood to become a champion cyclist, by way of designing his own bikes and his innovations in body-position aerodynamics. Miller as Obree does a good line in paranoia, presaging Obree’s revelations after the film premiered, which shed further light on why he tried to commit suicide on three occasions.

My favorite Sherlock, Jonny Lee Miller, gets his cycling groove on in 2006’s The Flying Scotsman. Mentioning Jonny Lee Miller and eccentric in the same paragraph is perhaps redundant, but the film is based on the true story of the eccentric Graham Obree who rose above a severely abusive childhood to become a champion cyclist, by way of designing his own bikes and his innovations in body-position aerodynamics. Miller as Obree does a good line in paranoia, presaging Obree’s revelations after the film premiered, which shed further light on why he tried to commit suicide on three occasions. Bring this post back to the Tour de France, the 2004 documentary Höllentour (Hell On Wheels) goes inside the Tour de France to focuses on the trials and tribulations of the T-Mobile team as they struggle to compete on cycling’s biggest stage. There are some heartbreaking moments which bring the whole scope of the race into focus.

Bring this post back to the Tour de France, the 2004 documentary Höllentour (Hell On Wheels) goes inside the Tour de France to focuses on the trials and tribulations of the T-Mobile team as they struggle to compete on cycling’s biggest stage. There are some heartbreaking moments which bring the whole scope of the race into focus. My first exposure to cycling fiction came via the bookmobile that visited my elementary school. I remember checking out a battered copy of The Big Loop by Claire Huchet Bishop. I don’t remember if it was the cycling or the author’s last name that made me read this, but I was hooked from the first page of the sepia toned world of the 1950s, in which Frenchmen always win their own Tour, and the old school style of teenage fiction, in which heroes are easily distinguished from villains. Perhaps this is outdated by today’s standards, but years later, I tracked down a used copy, reread it delightedly, and have it sitting proudly on my book shelves.

My first exposure to cycling fiction came via the bookmobile that visited my elementary school. I remember checking out a battered copy of The Big Loop by Claire Huchet Bishop. I don’t remember if it was the cycling or the author’s last name that made me read this, but I was hooked from the first page of the sepia toned world of the 1950s, in which Frenchmen always win their own Tour, and the old school style of teenage fiction, in which heroes are easily distinguished from villains. Perhaps this is outdated by today’s standards, but years later, I tracked down a used copy, reread it delightedly, and have it sitting proudly on my book shelves. As noted above, good sports mysteries are hard to come by. Getting the right blend of enough sports action and finding a solid mystery to fit in with the spotlighted sporting endeavor is a very fine balancing act. In Two Wheels, Greg Moody manages to pull off that balancing act without the aid of a net.

As noted above, good sports mysteries are hard to come by. Getting the right blend of enough sports action and finding a solid mystery to fit in with the spotlighted sporting endeavor is a very fine balancing act. In Two Wheels, Greg Moody manages to pull off that balancing act without the aid of a net. Between 1995 and 2002, author Moody produced five cycling murder mysteries featuring bike racer and reluctant sleuth, Will Ross. All are all above average sports mysteries with scalpel-like insights into both cycle racing and the business of cycle racing.

Between 1995 and 2002, author Moody produced five cycling murder mysteries featuring bike racer and reluctant sleuth, Will Ross. All are all above average sports mysteries with scalpel-like insights into both cycle racing and the business of cycle racing. Moody's dive into the bike racing world captures enough of the sport to keep those who are barely aware of the Tour de France each year interested, while also giving enough sporting grist for those for whom bike racing is a commanding passion – and, oh yeah, he also throws in a compelling murder mystery set in the heart of the European peloton.

Moody's dive into the bike racing world captures enough of the sport to keep those who are barely aware of the Tour de France each year interested, while also giving enough sporting grist for those for whom bike racing is a commanding passion – and, oh yeah, he also throws in a compelling murder mystery set in the heart of the European peloton. Jean-Pierre Colgan, the world champion, dies in a horrible toaster explosion. He is replaced on the powerful Haven Cycling Team by Will Ross, an aging American mediocrity. As Ross battles the team prejudice against him and slowly regains his form, he realizes that Colgan's death was no accident, that it is only the first step in a plan to dismantle the entire team, and given that knowledge, that his life isn't worth the tuppence he might find in corners of your mother’s sofa.

Jean-Pierre Colgan, the world champion, dies in a horrible toaster explosion. He is replaced on the powerful Haven Cycling Team by Will Ross, an aging American mediocrity. As Ross battles the team prejudice against him and slowly regains his form, he realizes that Colgan's death was no accident, that it is only the first step in a plan to dismantle the entire team, and given that knowledge, that his life isn't worth the tuppence he might find in corners of your mother’s sofa. Moody five cycling mysteries include Two Wheels, Perfect Circles, Derailleur, Dead Roll, and Dead Air, each of them enjoyable in their own right, each taking on a different aspect of the cycling world.

Moody five cycling mysteries include Two Wheels, Perfect Circles, Derailleur, Dead Roll, and Dead Air, each of them enjoyable in their own right, each taking on a different aspect of the cycling world. Two novels by Dave Shields, The Race and The Tour, are as fast-paced as the sprint legs of the Tour de France on which their stories focus. Troubled American racer Ben Barnes has a chance to redeem his honor, keep his word, and overcome the secrets of his past. Both books contain top notch race scenes from an author who learned his craft in the saddle.

Two novels by Dave Shields, The Race and The Tour, are as fast-paced as the sprint legs of the Tour de France on which their stories focus. Troubled American racer Ben Barnes has a chance to redeem his honor, keep his word, and overcome the secrets of his past. Both books contain top notch race scenes from an author who learned his craft in the saddle. My favorite Tour de France book can most likely be described as two-wheeled chick-lit. Yes, I know, many of you will be turned off by that term, but you'll be missing out on what is a terrific insider story. Cat by Freya North features the requisite Bridget Jones style journalistic heroine who sets out to report the Tour de France, inevitably getting entangled with some shaven legs along the way. That said, North’s research into the race and the personalities who ride in it gradually takes over the story giving the reader vicarious experience not to be missed.

My favorite Tour de France book can most likely be described as two-wheeled chick-lit. Yes, I know, many of you will be turned off by that term, but you'll be missing out on what is a terrific insider story. Cat by Freya North features the requisite Bridget Jones style journalistic heroine who sets out to report the Tour de France, inevitably getting entangled with some shaven legs along the way. That said, North’s research into the race and the personalities who ride in it gradually takes over the story giving the reader vicarious experience not to be missed. As the Tour itself heads out over the Pyrenees, cycle enthusiasts can get out on the road themselves or used the above recommendations to settle back into a visual or literary peloton.

As the Tour itself heads out over the Pyrenees, cycle enthusiasts can get out on the road themselves or used the above recommendations to settle back into a visual or literary peloton.

Published on November 07, 2019 22:36

October 31, 2019

THE CRIME ANTHOLOGIES

THE CRIME ANTHOLOGIES

PAUL BISHOP PRESENTSBANDIT TERRITORYTen New Tales ofMurder and MayhemIn bandit territory, writers can think the unthinkable and then put those thoughts into words on paper—words to chill their readers’ souls...Bandit Territory is a place you don’t go unless you are alert, armed, and have plenty of backup...

PAUL BISHOP PRESENTSBANDIT TERRITORYTen New Tales ofMurder and MayhemIn bandit territory, writers can think the unthinkable and then put those thoughts into words on paper—words to chill their readers’ souls...Bandit Territory is a place you don’t go unless you are alert, armed, and have plenty of backup...There is plenty of bandit territory in corporation boardrooms, political campaigns, or high stakes poker rooms—a place where the rules don’t apply, where the knives come out, and fortunes and lives can be destroyed in a heartbeat. The most dangerous bandit territory, however, is in the mind...This deviant and deadly psychological bandit territory is also where crime and mystery writers thrive. It is here they hatch plots, dare to think the thoughts others would find abhorrent, and ask ugly questions of themselves and their characters.

Includes Stories by Paul Bishop, Nikki Nelson Hicks, Nicholas Cain, Richard Prosch, Wayne D. Dundee, Mel Odom, Ben Boulden, Jeremy Brown, Hock Hochheim, Scott Dennis Parker, and Jason Chirevas.

PAUL BISHOP PRESENTSDISORDERLY CONDUCTAnother Ten Tales of Murder and MayhemDisorderly conduct is the gateway drug to crime. It’s not far from here to yonder—disorderly to uncooperative to resisting, then on to physical assault, assault with a deadly weapon, armed robbery, to wanted dead or alive.

PAUL BISHOP PRESENTSDISORDERLY CONDUCTAnother Ten Tales of Murder and MayhemDisorderly conduct is the gateway drug to crime. It’s not far from here to yonder—disorderly to uncooperative to resisting, then on to physical assault, assault with a deadly weapon, armed robbery, to wanted dead or alive. Disorderly conduct is the rabbit hole of violence. It’s the writing on the wall and it’s the spark of ideas for crime writers everywhere...In Disorderly Conduct, bestselling author and crime fiction maven Paul Bishop has once again locked up the criminally minded among us—Not those who would actually do the crime (most of us couldn’t do the time), but brilliant purveyors of criminal visions. Enjoy these ten tales of murder & mayhem and may the words spur your own inner world of imagination.

Stories by Paul Bishop, O’Neil De Noux, Wayne D. Dundee, Brian Drake, Mike A. Baron, James Hopwood, Bill Craig, Bobby Nash, Jean Rabe, and Nicholas Cain.

PAUL BISHOP PRESENTSCRIMINAL TENDENCIESTen More Tales of Murder and MayhemCriminal tendencies lie dormant within the labyrinth of all our psyches. Most of us keep them firmly repressed. But what about those individuals who choose to follow their darker impulses.

PAUL BISHOP PRESENTSCRIMINAL TENDENCIESTen More Tales of Murder and MayhemCriminal tendencies lie dormant within the labyrinth of all our psyches. Most of us keep them firmly repressed. But what about those individuals who choose to follow their darker impulses.Bestselling author and crime fiction expert Paul Bishop has again brought together top crime fiction writers and rising stars to share ten devious tales about criminal tendencies too powerful to ignore...If the dark side of life is your beat, or if your own criminal tendencies are barely restrained, read on...

Stories by Paul Bishop, Nikki Nelson-Hicks, Richard Prosch, Brian Drake, Mark Allen, Mike Faricy, Michael A. Baron, Jack Badelaire, Ben Boulden, and Eric Beetner...

PAUL BISHOP PRESENTS

PATTERN OF BEHAVIOR

Ten Tales of

Murder and MayhemEvery story is a gem of crime and punishment...Bestselling author and crime fiction expert, Paul Bishop brings together ten tales of murder and mayhem from the devious imaginations of both top crime writers and the genre’s rising stars...Filled with unforeseen twists and turns, these tales range from dark to deadly, each one designed to snatch your breath away.

PAUL BISHOP PRESENTS

PATTERN OF BEHAVIOR

Ten Tales of

Murder and MayhemEvery story is a gem of crime and punishment...Bestselling author and crime fiction expert, Paul Bishop brings together ten tales of murder and mayhem from the devious imaginations of both top crime writers and the genre’s rising stars...Filled with unforeseen twists and turns, these tales range from dark to deadly, each one designed to snatch your breath away.Includes Stories by Paul Bishop, Eric Beetner, Nicholas Cain, Ben Boulden, Brian Drake, Christine Matthews, L.J. Martin, Richard Prosch, Robert Randisi, and Nicole Nelson-Hicks.

Published on October 31, 2019 05:03

October 30, 2019

NEW WEST—GUNSLINGER

GUNSLINGER #1

GUNSLINGER #1KILLER’S CHANCE

Mel Odom writing as A.W. HartFourteen-year-old Connor Mack dreams of a life adventure while stuck plowing, doing all the chores, and being treated as a slave on the half barren family spread in East Texas. He plans to one day flee the beatings delivered by his hulking older brothers and lazy pa. But he knows if he does, he must take his twin sister Abby—who is not always right in the head—with him. He gets his chance when River Hicks, a man wanted for the murder of a policeman in Fort Worth, rides in with a pack of bounty hunters on his trail. When the gun smoke clears, Connor has killed men for the first time, but he also knows this is his and Abby’s time to escape their life of abuse…Knowing the law will soon be on their heels, they follow Hicks—an outlaw driven by his own demons, and by deep secrets which somehow involve the Mack twins…Conner has a lot of learning and growing up to do—and he has to stay alive to do it.

GUNSLINGER #2KILLER’S FUSEEric Beetner writing as A.W. HartWhile waiting for his quarry to arrive in the mining town of Willimet, Hicks joins a pair of outlaws with a scheme to find a lost cache of gold…With Hicks gone, Conner and Abby are welcomed into the home of a local widow—the richest lady in town with a deadly secret agenda. When the widow develops an unnatural attachment to Abby, and her three unbalanced sons turn deadly, the beautiful mansion on the hill turns into a possessed house of horrors. Connor can feel Abby slipping away as the house and the widow put a spell on her. When he uncovers the family’s secrets, he knows he’s in a desperate race to save Abby…The fuse has been lit and it’s burning down fast for both gunslingers. Can they join forces again and get away before it all blows up in their faces?

GUNSLINGER #2KILLER’S FUSEEric Beetner writing as A.W. HartWhile waiting for his quarry to arrive in the mining town of Willimet, Hicks joins a pair of outlaws with a scheme to find a lost cache of gold…With Hicks gone, Conner and Abby are welcomed into the home of a local widow—the richest lady in town with a deadly secret agenda. When the widow develops an unnatural attachment to Abby, and her three unbalanced sons turn deadly, the beautiful mansion on the hill turns into a possessed house of horrors. Connor can feel Abby slipping away as the house and the widow put a spell on her. When he uncovers the family’s secrets, he knows he’s in a desperate race to save Abby…The fuse has been lit and it’s burning down fast for both gunslingers. Can they join forces again and get away before it all blows up in their faces?  GUNSLINGER #3KILLER’S CHOICEMike Black writing as A.W. HartAn ostensibly simple, but hazardous job of delivering some much-needed nitroglycerin components to a burgeoning railroad town in the Arizona Territory proves problematic for the trio of River Hicks, Connor Mack and his twin sister, Abby…Along the way they rescue a Chinese man on the verge of being lynched by a pack of crooked deputies. Moved by the Chinese man’s tale of his quest to free his beautiful fiancée from the savage grip of human traffickers, they are surprised and dismayed to find the girl is being held in the town of Woodman, which is their own destination. The town is run by a brutal, self-aggrandizing strongman who has taken over and renamed the town after himself. This self-anointed Duke also has ties to a mysterious financial backer who, unbeknownst to everyone, has enlisted an unscrupulous Pinkerton detective and a professional killer, known as The Regulator, to track down and kill Hicks, Connor, and Abby…All trails unite in the dusty streets of the small, Arizona town where Hicks, Connor, and Abby come face to face with the vicious array of killers for a final showdown they soon realize has become a killer’s choice.

GUNSLINGER #3KILLER’S CHOICEMike Black writing as A.W. HartAn ostensibly simple, but hazardous job of delivering some much-needed nitroglycerin components to a burgeoning railroad town in the Arizona Territory proves problematic for the trio of River Hicks, Connor Mack and his twin sister, Abby…Along the way they rescue a Chinese man on the verge of being lynched by a pack of crooked deputies. Moved by the Chinese man’s tale of his quest to free his beautiful fiancée from the savage grip of human traffickers, they are surprised and dismayed to find the girl is being held in the town of Woodman, which is their own destination. The town is run by a brutal, self-aggrandizing strongman who has taken over and renamed the town after himself. This self-anointed Duke also has ties to a mysterious financial backer who, unbeknownst to everyone, has enlisted an unscrupulous Pinkerton detective and a professional killer, known as The Regulator, to track down and kill Hicks, Connor, and Abby…All trails unite in the dusty streets of the small, Arizona town where Hicks, Connor, and Abby come face to face with the vicious array of killers for a final showdown they soon realize has become a killer’s choice.

Published on October 30, 2019 07:06

NEW WEST—AVENGING ANGELS

AVENGING ANGELS #1VENGEANCE TRAIL

AVENGING ANGELS #1VENGEANCE TRAILPeter Brandvold writing as A.W. HartSaddle Up For A Heart-Pounding, Bullet-Burning, Bible-Thumping Western Series Like None You’ve Ever Read Before…Reno Bass and his sister Sara are young, blond, blue-eyed twins from western Kansas. Raised right in a good Christian family, they’re pure as the driven snow. But when their family is massacred, they ride the Vengeance Trail to fulfill their father’s dying request—to purge the earth of the Devil’s spawn in the name of God.

In the first book of this shocking new series, Reno and Sara’s farm is burned and their family murdered by a group of ex-Confederate soldiers known as the Devil’s Horde. These ex-Confederates—led by Major Eustace The Bad Old Man Montgomery and Major Black Bob Robert Hobbs—have a chip on their shoulders, and they’re burning a broad swath across the Yankee north, murdering, pillaging, and raping their way to the Colorado Territory…But when they burn the Bass farm, they find out not every follower of God is a sheep. Sworn to vengeance, Reno and Sara become black-winged avenging angels on a mission from God. Hounding the Confederate devils’ every step, these black-winged angels begin efficiently and bloodily killing them—one by one and two by two—reading to them from the Good Book while sending them back to Hell.

AVENGING ANGELS #2SINNER’S GOLDWayne D. Dundee writing as A.W. Hart After avenging the brutal slaughter of their family at the hands of Hell-spawned cutthroats, twins Reno and Sara Bass continue their quest to purge the West of the Devil's minions who prey on the vulnerable and unsuspecting…When they reluctantly accompany the hapless Brenda Walon to Hatchet, Nebraska, it quickly becomes clear Brenda is in deadly danger. The seemingly quiet town of Hatchet has many dark secrets—including the legend of hidden gold and the greedy desires of those willing to kill for it!

AVENGING ANGELS #2SINNER’S GOLDWayne D. Dundee writing as A.W. Hart After avenging the brutal slaughter of their family at the hands of Hell-spawned cutthroats, twins Reno and Sara Bass continue their quest to purge the West of the Devil's minions who prey on the vulnerable and unsuspecting…When they reluctantly accompany the hapless Brenda Walon to Hatchet, Nebraska, it quickly becomes clear Brenda is in deadly danger. The seemingly quiet town of Hatchet has many dark secrets—including the legend of hidden gold and the greedy desires of those willing to kill for it!Sara and Reno realize not all of the Devil's horde ride roughshod and bloody in the open. Now it's up to the Avenging Angels to protect the innocent by flushing out Hatchet's human demons and sending them back to Hell!

AVENGING ANGELS #3DAY OF CALAMITYRichard Prosch writing as A.W. HartHaving survived the massacre of their Kansas home, Reno and Sara Bass now ride the vengeance trail for bloody justice and lucrative bounty. When two stolen angels and a preacher’s dark secret lure them to the violent train town of North Platte, shooting their way out isn’t just an option—it’s the Avenging Angels’ only choice.

AVENGING ANGELS #3DAY OF CALAMITYRichard Prosch writing as A.W. HartHaving survived the massacre of their Kansas home, Reno and Sara Bass now ride the vengeance trail for bloody justice and lucrative bounty. When two stolen angels and a preacher’s dark secret lure them to the violent train town of North Platte, shooting their way out isn’t just an option—it’s the Avenging Angels’ only choice.Hunted by the law, the army, and a shotgun named Pike, Reno and Sara land in a crucible of frontier fire that shakes their faith to the core and tests their gun hands like never before...

Published on October 30, 2019 06:57

October 29, 2019

THE WORDSLINGER TRAILS—RALPH COMPTON

THE WORDSLINGER TRAILS

RIDING TALL

RALPH COMPTON

(April 11, 1934 – September 16, 1998)

THE WORDSLINGER TRAILS

RIDING TALL

RALPH COMPTON

(April 11, 1934 – September 16, 1998)

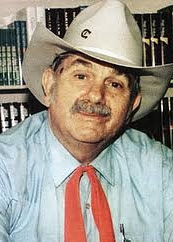

Not many writers stand six-foot-eight-inches tall without their boots. Neither have many written twenty-three books in eight years, with several selling over a million copies and hitting the USA TodayBestseller List. The only wordslinger to hit the mark in both classifications is Western reader’s favorite, Ralph Compton.

Not many writers stand six-foot-eight-inches tall without their boots. Neither have many written twenty-three books in eight years, with several selling over a million copies and hitting the USA TodayBestseller List. The only wordslinger to hit the mark in both classifications is Western reader’s favorite, Ralph Compton.

Wearing his boots and his cowboy hat, the late Compton’s wiry frame rose head and shoulders above the crowd whenever he went. His most amazing accomplishment, however, was not growing tall, but his prolific telling of Western tall tales. At fifty-six-years-old, having little prior writing experience, he sat down and began the opening chapter of his first his first Western—The Goodnight Trail. In the next eight years, he wrote twenty-two more Westerns before cancer took him home at age sixty-four. His canon of work became so popular, his publisher (Signet) used his legacy to build the Ralph Compton Brand. There have since been eight-two Westerns—authored by some of the best writers in the genre—published under the Ralph Comptonbanner.

Wearing his boots and his cowboy hat, the late Compton’s wiry frame rose head and shoulders above the crowd whenever he went. His most amazing accomplishment, however, was not growing tall, but his prolific telling of Western tall tales. At fifty-six-years-old, having little prior writing experience, he sat down and began the opening chapter of his first his first Western—The Goodnight Trail. In the next eight years, he wrote twenty-two more Westerns before cancer took him home at age sixty-four. His canon of work became so popular, his publisher (Signet) used his legacy to build the Ralph Compton Brand. There have since been eight-two Westerns—authored by some of the best writers in the genre—published under the Ralph Comptonbanner.

On US 411, near Odenville, Alabama, drivers pass a sign claiming Home of Ralph Compton. It denotes the beginning of a six mile trek through the woods to the log cabin with the dirt floor where Compton was born. In his autobiography, Compton stated, “You walked three miles along the Seaboard Railroad track, climbed a cut bank and trudged another three miles through the woods.” Born in 1937, at the tail end of the Depression, Compton’s family struggled with the harsh realities of poverty, “It seemed like we all started poor and went downhill from there.”

On US 411, near Odenville, Alabama, drivers pass a sign claiming Home of Ralph Compton. It denotes the beginning of a six mile trek through the woods to the log cabin with the dirt floor where Compton was born. In his autobiography, Compton stated, “You walked three miles along the Seaboard Railroad track, climbed a cut bank and trudged another three miles through the woods.” Born in 1937, at the tail end of the Depression, Compton’s family struggled with the harsh realities of poverty, “It seemed like we all started poor and went downhill from there.”

His mother had a sixth grade education; his father, fifth grade. “By the time FDR’s ‘team of mules, seed and fertilizer’ stake got to us, there were no mules.” His father settled for oxen instead of mules, along with seed and fertilizer. Inexperienced at best when it came to planting a crop, Compton said of his father, “In his best year, he made almost enough to repay what he owed the government.”

His mother had a sixth grade education; his father, fifth grade. “By the time FDR’s ‘team of mules, seed and fertilizer’ stake got to us, there were no mules.” His father settled for oxen instead of mules, along with seed and fertilizer. Inexperienced at best when it came to planting a crop, Compton said of his father, “In his best year, he made almost enough to repay what he owed the government.”

Compton graduated from St. Clair County High School in Odenville, a major accomplishment for a young boy in worn out clothes and rarely a full meal. Compton states, “In those days, welfare families were not looked on with favor. There were four of us, and we received the staggering sum of thirty-nine dollars a month. I owe my high school graduation to understanding teachers who provided odd jobs so I had the bare necessities.”

Compton graduated from St. Clair County High School in Odenville, a major accomplishment for a young boy in worn out clothes and rarely a full meal. Compton states, “In those days, welfare families were not looked on with favor. There were four of us, and we received the staggering sum of thirty-nine dollars a month. I owe my high school graduation to understanding teachers who provided odd jobs so I had the bare necessities.”

He points to his high school principal, Nancy Wilson (to whom he dedicated his first Western, The Goodnight Trail), for his love of reading and his ability to read with comprehension and retention. “Because I did read, she moved me ahead, encouraging me to read literature and history more advanced than my grade required. Before my graduation, I knew I wanted to write, although I wasn’t sure what."

He points to his high school principal, Nancy Wilson (to whom he dedicated his first Western, The Goodnight Trail), for his love of reading and his ability to read with comprehension and retention. “Because I did read, she moved me ahead, encouraging me to read literature and history more advanced than my grade required. Before my graduation, I knew I wanted to write, although I wasn’t sure what."

Compton served in the Army during the Korean War. When he returned home, he was still unsure of his career direction. He joined forces with his brother, Bill, a skilled guitarist with a good voice. They formed a bluegrass group, and set out to play the local circuit of legion halls, armories, and schools. They played live on local radio stations, often racing from station to station to reach the widest audience possible.

Compton served in the Army during the Korean War. When he returned home, he was still unsure of his career direction. He joined forces with his brother, Bill, a skilled guitarist with a good voice. They formed a bluegrass group, and set out to play the local circuit of legion halls, armories, and schools. They played live on local radio stations, often racing from station to station to reach the widest audience possible.  Compton recalled, “Most little stations provided time for free on Saturday afternoon, usually fifteen to thirty minutes for those enthusiastic enough—or dumb enough—to donate their talent for the exposure.” In 1960, Bill moved on to play with Country Boy Eddie (Gordon Edwards Burns), a singer, fiddler and guitarist who hosted the long-running Country Boy Eddie Show on Alabama’s WBRC-TV station.

Compton recalled, “Most little stations provided time for free on Saturday afternoon, usually fifteen to thirty minutes for those enthusiastic enough—or dumb enough—to donate their talent for the exposure.” In 1960, Bill moved on to play with Country Boy Eddie (Gordon Edwards Burns), a singer, fiddler and guitarist who hosted the long-running Country Boy Eddie Show on Alabama’s WBRC-TV station.

Ralph traveled to Nashville where he struggled as a songwriter. He co-founded The Rhinestone Rooster, a tabloid magazine, but quickly went broke. He borrowed money to keep the magazine afloat, but quickly went broke again. Not willing to give up, he turned The Rhinestone Rooster into a record label, but still did not find enough success to make the venture worthwhile.

Ralph traveled to Nashville where he struggled as a songwriter. He co-founded The Rhinestone Rooster, a tabloid magazine, but quickly went broke. He borrowed money to keep the magazine afloat, but quickly went broke again. Not willing to give up, he turned The Rhinestone Rooster into a record label, but still did not find enough success to make the venture worthwhile.

Jobs as a radio announcer, a newspaper columnist, and other odd jobs followed. In the summer of 1988 (“When I was pretty well fed up with the music business...”), the then fifty-four-year-old Compton began writing a novel. He wrote what he knew, “...a Southern novel, a hard times tale of growing up during the depression.”

Jobs as a radio announcer, a newspaper columnist, and other odd jobs followed. In the summer of 1988 (“When I was pretty well fed up with the music business...”), the then fifty-four-year-old Compton began writing a novel. He wrote what he knew, “...a Southern novel, a hard times tale of growing up during the depression.”

Bob Robertson, a literary agent who read the manuscript, felt Compton’s writing showed promise. He didn’t, however, believe he could sell the novel to a publisher as the market was saturated with similar coming of age tales. Robertson was impressed enough with Compton’s writing to ask him a straightforward question...”Can you write a western?” Compton’s reply would ultimately change his life...“I don’t know. I like Westerns, but I’ve never written one. Let me try.”

Bob Robertson, a literary agent who read the manuscript, felt Compton’s writing showed promise. He didn’t, however, believe he could sell the novel to a publisher as the market was saturated with similar coming of age tales. Robertson was impressed enough with Compton’s writing to ask him a straightforward question...”Can you write a western?” Compton’s reply would ultimately change his life...“I don’t know. I like Westerns, but I’ve never written one. Let me try.”

Writing feverishly in every spare moment around his forty-hour a week nighttime work schedule, he completed a shoot-‘em-up 185 page manuscript. However, when he showed it to Robertson, the agent told him it was good, but had nothing to distinguish it from hundreds of other Westerns.

Writing feverishly in every spare moment around his forty-hour a week nighttime work schedule, he completed a shoot-‘em-up 185 page manuscript. However, when he showed it to Robertson, the agent told him it was good, but had nothing to distinguish it from hundreds of other Westerns.  The agent then offered more sage advice, “Write the kind of Western you like. And plan on writing at least three books, a minimum of three-hundred and fifty pages each.” This seemed overwhelming to Compton, who felt he’d already done the best he could. But Robertson continued to encourage him. The agent wanted a potential series, something with a hook that had not been done before.Over the next several weeks Compton and Robertson kicked around ideas. They wanted a concept to embody all the exciting aspects of the Western, yet be unique in its presentation. From their collaboration, the concept of the Trail Drive series was created.

The agent then offered more sage advice, “Write the kind of Western you like. And plan on writing at least three books, a minimum of three-hundred and fifty pages each.” This seemed overwhelming to Compton, who felt he’d already done the best he could. But Robertson continued to encourage him. The agent wanted a potential series, something with a hook that had not been done before.Over the next several weeks Compton and Robertson kicked around ideas. They wanted a concept to embody all the exciting aspects of the Western, yet be unique in its presentation. From their collaboration, the concept of the Trail Drive series was created.

In January of 1990, after much sweat and research, Compton presented Robertson with a detailed synopsis of the first three books in the series—The Goodnight Trail, The Western Trail, and The Chisholm Trail. Robertson enthusiastically approved. Eight months later, Compton finished writing The Goodnight Trail, a rip-roaring western about the cattle drive which established a new route from Texas to Colorado.

In January of 1990, after much sweat and research, Compton presented Robertson with a detailed synopsis of the first three books in the series—The Goodnight Trail, The Western Trail, and The Chisholm Trail. Robertson enthusiastically approved. Eight months later, Compton finished writing The Goodnight Trail, a rip-roaring western about the cattle drive which established a new route from Texas to Colorado.

Compton skillfully mixed fact with fiction as told the tale former Texas Rangers Benton McCaleb, Will Elliot, and Brazos Gifford to ride the trail alongside the real life Charles Goodnight. Compton’s characters were fresh and alive, jumping off the page with the historical background accuracy that would become his trademark.

Compton skillfully mixed fact with fiction as told the tale former Texas Rangers Benton McCaleb, Will Elliot, and Brazos Gifford to ride the trail alongside the real life Charles Goodnight. Compton’s characters were fresh and alive, jumping off the page with the historical background accuracy that would become his trademark.

The rights to The Goodnight Trail sold quickly, establishing a profitable long-term relationship with publishers St. Martin’s Press and Signet. It sold more than 1 million copies and was chosen by the Western Writers of America as a finalist for their Medicine Pipe Bearer Award—given to the best debut Western of the year.

The rights to The Goodnight Trail sold quickly, establishing a profitable long-term relationship with publishers St. Martin’s Press and Signet. It sold more than 1 million copies and was chosen by the Western Writers of America as a finalist for their Medicine Pipe Bearer Award—given to the best debut Western of the year.

Compton had read many of the great Western writers. While believing he had developed his own style, he claimed, “I shamelessly adopted one element, which I admired most in the work of Louis L’Amour. While there was romance in his books, there was no graphic, shocking sex.”Of his writing, Compton also explained, “I depend solely on three elements: (1) a powerful sense of time and place, (2) a strong, fast-paced story, with interesting sub-plots, and (3) powerful, memorable characters.” His inspiration for the strong characters and style of storytelling he brought to his own work was the television series Gunsmoke.

Compton had read many of the great Western writers. While believing he had developed his own style, he claimed, “I shamelessly adopted one element, which I admired most in the work of Louis L’Amour. While there was romance in his books, there was no graphic, shocking sex.”Of his writing, Compton also explained, “I depend solely on three elements: (1) a powerful sense of time and place, (2) a strong, fast-paced story, with interesting sub-plots, and (3) powerful, memorable characters.” His inspiration for the strong characters and style of storytelling he brought to his own work was the television series Gunsmoke.

In a 1993 issue of The Roundup, a publication of the Western Writers of America, Compton returned to the question that started it all...“Can you write a western? I could, and thank God, I did. My one regret is I lacked the confidence and courage to do it sooner.”

In a 1993 issue of The Roundup, a publication of the Western Writers of America, Compton returned to the question that started it all...“Can you write a western? I could, and thank God, I did. My one regret is I lacked the confidence and courage to do it sooner.”

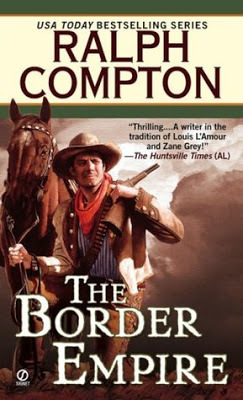

Ten more Westerns in the Trail Seriesfollowed. Books in the Sundown Riderseries and the Border Empire series, along with a dozen other Westerns added to his prolific, fast paced output. Like a man knowing he is running out of time, Compton authored more than two dozen novels during the last decade of his life. Six Guns and Double Eagles, The California Trail, and The Shawnee Trail were all bestsellers in 1997.