Kyle Fitzgibbons's Blog, page 11

July 3, 2016

Capitalism. Communism. Democracy.

My last article was on why I think “competition is stupid” for modern individuals to uphold as a cherished value that benefits individuals and society. One important reason that competition is received as a self-evident benefit is its connection to American capitalism. In

No Contest

, Alfie Kohn states that, “Capitalism can be thought of as the heart of competitiveness in American society” (p. 70).

My last article was on why I think “competition is stupid” for modern individuals to uphold as a cherished value that benefits individuals and society. One important reason that competition is received as a self-evident benefit is its connection to American capitalism. In

No Contest

, Alfie Kohn states that, “Capitalism can be thought of as the heart of competitiveness in American society” (p. 70).This is a reasonable argument to make regarding how the specific circumstances in America have turned out, but should not be taken as true in general. Capitalism does not necessitate competition. Competition is zero-sum by definition. When you win, I can’t. Capitalism is not. Ergo, there is no innate reason for competition to be the sine qua non of capitalism.

So while I agree with Kohn’s overall points in building a case against competition, I don’t view them as a huge strike against capitalism per se. I’d like to reflect in greater detail on:

what I see as the fundamental aspect of capitalism, what separates it from Marxist communism, how communism fell apart in practice, and why capitalism, not communism, is so often found in tandem with democracy.

Warning: This post will be a bit more “classroom lecture-y” than I’m typically like, but you can skip to the conclusion for all the main points if you’d rather not see how I arrived at them.

Capitalism

I can understand why Kohn would make his above statement. American capitalism and the beliefs we hold as a culture do promote competition. We have been sold a belief that competition is what drives capitalism and that “only the strongest shall survive,” which is partly true.

In a market that can only reasonably support one firm, such as natural monopolies like utility services and railroads, often the firm with the cheapest product will capture the entire market and all other firms will go under as a government lends their support to the firm’s efforts to provide some large-scale infrastructure to ensure supply.

The above example does fit with Kohn’s definition of competition as attaining a mutually exclusive goal. If two firms want to remain open and dominate the market, but only one can, then they have mutually exclusive goals of being that firm. This reflects the fact that both firms have the same goal - to remain open - more than it reflects an inherent aspect of capitalism. Americans could simply decide to vote that large-scale natural monopolies be run by the government, which would take away the goal of being the firm in that market.

Another aspect of American capitalism that promotes competition is inherent to our legal system, which mandates that firms maximize profits for shareholders, thereby dictating the goal by which firms measure themselves. This is again not innate to capitalism, but part of our socially constructed legal system and therefore possible to change.

We could legally obligate firms to chase different ends besides maximizing profits, such as maximizing employee and consumer well-being. This is certainly more difficult to quantify and I am not arguing otherwise, only that it is theoretically possible to select different goals. Two examples of projects that look in this direction are the developments of the Human Development Index and Gross National Happiness, which attempt to capture well-being in a more holistic way than simply GDP. Surely if entire countries and the UN can make the effort to measure things such as these, our legal system could figure out a manageable way to set different goals for firms if the desire were there.

So if competition is not the central characteristic of capitalism, what is? The central characteristic of capitalism is individual decision-making and choice, as opposed to any sort of centralized decision-making.

Free markets allow individuals to make their own choices about what is in their best interests and for firms to respond by producing goods and services to match those desires and needs. This should make a connection to well-being quite obvious. It is much easier for me to decide what will contribute most greatly to my own well-being than for some central authority to do so. Capitalism allows this to happen rather efficiently through the use of markets.

Marxism

Karl Marx originally wrote about his economic theory of communism as an endpoint in a trajectory he saw playing out through his analysis of history. It was much more an observation of history, with a prediction for the future, than a prescription.

He observed that humanity initially lived at the subsistence level in a state of equality during the hunter-gatherer era. Everyone was equal because essentially everyone was poor. They had equality through poverty.

This changed over time as technology improved, but led to feudalism where powerful aristocracies could control the labor tied to the land it worked on. With the continual evolution of technology, this situation eventually shifted to capitalism as merchants became rich and uncontrollable by the aristocracies.

Seeing this pattern of shifting political-economic landscapes, Marx predicted that eventually the laborers (proletariat) in a capitalist society would grow tired of having a lower quality of life than the owners of capital, who would become a smaller and smaller percentage of the population with more and more of the total wealth.

This inequality would lead to an overthrowing of the oppressive capitalists by the laborers and result in the formerly oppressed laborers being the oppressors. Marx, however, did not see this “dictatorship of the proletariat” lasting very long and predicted that eventually the new oppressors would do away with institutions because all would decide to live in a state of equality where laws and police weren’t needed.

What’s most important to realize about this economic theory is that it is still largely individualistic. The laborers simply “gain class consciousness” of the unequal situation and realize that they are not benefitting from the capitalist system as much as they could be due to the owners of capital capturing the majority of the wealth. This is almost exactly what happened in the Occupy Movement that chanted, “We are the 99%”.

Individuals in Marxist communism are deciding what best maximizes their well-being. The political will of the majority of the population chooses to live in a state of equality, rather than a state of inequality that benefits only a small percentage of elite capital owners. It is a turn away from competition and inequality toward cooperation and equality by choice. This is not how communism as turned out in practice.

Communism in Practice

While capitalism and its organic evolution into Marxist communism focus on individuals making decisions by cooperative and collective means, communism as it has been historically implemented focuses on collective “equality” through centralized decision-making. In practice, this has consisted of an authoritarian government doing the decision-making, but as will be discussed in the Democracy section does not have to be the case.

In order to reach a state of equality in practice, people like Vladimir Lenin believed it was necessary to create a “vanguard of the proletariat” to push the working class into moving towards and adopting communism. This allowed the “vanguard” to simply become a new set of elites and begin making decisions. Once in power, these vanguards operated as both political and economic decision makers with little accountability from a democratic voting public.

That turns out to be the main problem of communism in practice. Trying to decide what is best for individual well-being that is not your own is very difficult, especially if you are responsible for the individual well-being of millions of individuals in a large nation-state as a central planner. There is simply no way that a central decision-maker can go about that task in an optimal way. They would literally need to know millions of pieces of information in order to figure out how to distribute and utilize a nation’s resources.

Who should get what goods and services? How much should they get? Do any innovations or discoveries need to made in order to produce the goods and services needed? How many researchers are needed? The list of questions that need answers in a large economy are way beyond any central planner once you begin asking them. With all this in mind, it is easier to recognize that centralized planning in communism is a historical byproduct of authoritarian governments more so than Marx originally intending it.

Democracy

All of this brings us to democracy, which is the political theory that favors individuals making decisions instead of an authoritarian figure deciding for them. Rather than trust absolute power to a single person or small group, it is better to decentralize it to as many people as possible. A voting public is able to hold elected officials accountable for their actions with the threat and ability to remove said officials if necessary.

Democracy is a political system, not an economic one like capitalism and communism are. Therefore, it could hypothetically be decided in a democracy to create a central economic authority that could act in a traditionally communist fashion. This isn’t likely to happen, however, as most nation-states that value individual liberty in politics are also likely to value the same thing in economics. The political will of the people just isn’t likely to turn over autonomy to a central economic planner in a democracy.

Instead, it is much more likely that democracy turns to an economic system like the world is seeing in Scandinavian countries. These countries operate as social democracies. These political-economic systems are much more stable and sustainable than the traditionally unequal capitalist societies or historically authoritarian forms of communism.

This is because social democracies allow individuals to make political choices through voting just like traditional democracies, but unlike authoritarian regimes, while also allowing individuals to make economic choices through free markets just like traditional capitalist systems. The difference is that the populace has collectively decided to live with high taxes in order to support socially beneficial programs after the market has already been allowed to create wealth, which as you will remember is much more efficient than a central planner attempting to do so. The population has chosen the taxation and redistribution, not been forced into it.

Conclusion

So there you have it. Capitalism does require competition. Capitalism is about individual economic choice and decision-making. Marxist communism can be viewed as an organic evolution of capitalism towards more equality through the collective will of the individuals within society. Communism in practice has been much more about authoritarian and centralized political and economic decision-making, which is its main problem. Capitalism and democracy both allow maximal individual autonomy over economic and political decisions respectively, which is why they work so well together and allow society to move towards systems such as social democracy found in Scandanavia where people choose to cooperate for the benefit of all members of society.

Published on July 03, 2016 01:00

July 1, 2016

Competition Is Stupid

I’m beginning to ask myself more and more frequently, “What use is competition? Does it really serve any good purpose?”

I’m beginning to ask myself more and more frequently, “What use is competition? Does it really serve any good purpose?”I’ve been going about this question two ways: asking myself and reflecting on it in a subjective manner tied to all of the experience and knowledge I have gained and also by reading on the topic and looking, searching, and questioning whatever I read.

So far, nothing. I cannot currently see a legitimate use.

In fact, I think the biggest revolution in history may come when humans decide collectively that it isn’t a good at all, but something to be overcome and rejected.

Reflections

I’ve asked several classes worth of my economics students what would happen if we gave everyone a basic income and no one had to work for a living. They all initially said that people would have no incentive to work and that nothing would get done.

This took me down the path of incentives, which I currently view as possibly the biggest lie in economics and our modern world in general. The belief that people must have incentives to produce anything is simply not true. I can point you to research on motivation. I can explain the difference between intrinsic and extrinsic rewards. I can point to the research on creativity and the connection between rewards and complex tasks.

But I find it easier to reflect on the individuals in our world like Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg. Jonas Salk, Nikola Tesla, Benjamin Franklin, Leonardo Da Vinci, Aristotle, Friedrich Nietzsche, Claude Shannon, and the list goes on. Or consider revolutionaries, who often suffer through years of violence and discord for a larger purpose that can ultimately bring great satisfaction and meaning to their lives and the lives of others.

Scientists, philosophers, computer programmers, writers, and everyone else that produces something new and novel that requires hours, weeks, months, and years of hard work, dedication, teamwork, and toil simply do not do it for the incentives and external rewards.

Let’s take one very simple example. Name one person involved in creating the internet. I’ll wait. I’m guessing the majority of people cannot. That’s because it was invented as a research and government project to help with communications. It simply let them get on with their work better. On different note, “Fleming's accidental discovery and isolation of penicillin in September 1928 marked the start of modern antibiotics”. Many important discoveries and inventions have happened in exactly these ways: to make our already meaningful work easier or as happy accidents.

Creation and production, especially of complex, world changing ideas, is most often its own reward or done for altruistic purposes (see the revolutionary reference above). Many of the people who have invented scientific breakthroughs have not been the ones to make billions on the ideas. Scientists often toil in somewhat obscurity with the help of basic research grant money and then have to turn over that research and breakthrough to the university they work at, the government that employs them, or a major corporation who can then turn the ideas into profitable products. The creation itself is no product of huge incentives.

On a personal note, I cannot remember the last time I did something for money. Granted, I have a very fortunate life and have been lucky never to have been truly hungry or wanting. However, that only goes to help make my point. Given a life where food, health, and education are not the primary aims needing to be met, I have been completely free to pursue challenges, learning, and development for their own sake. I now work essentially only for whatever growth opportunities a job or task presents with the ultimate goal of being able to give more back to society and world through that process.

This is no coincidence. “A large number of studies have confirmed that humans across cultures have a need for autonomy, competence, relatedness, security, and self-esteem”. These are basic needs that we will search out as humans without the need for external incentives. It is because my needs for security, autonomy, relatedness, and self-esteem have been met that the drive for competence (i.e. growth, learning, development, mastery) can flourish.

So personal reflection and my own knowledge gained through extensive study of human motivation, incentives, rewards, creativity, and complex tasks do not account for our love of competition.

Readings

Instead of reflection, maybe specifically hunting for an answer to these questions would be more fruitful. Maybe there are research articles, blogs, magazines, or books that can help me out.

Not so much.

While a Google search for “why is competition good” turns up 210,000,000 results, the first page contains mostly business and education articles with titles like 20 Proven Reasons Why Competition Is Good | Business Gross and Debate: Is Competition good for kids? - Ineos. A quick read through these articles shows very little critical thinking and almost no reference to any of the literature I hinted at above.

For instance, the first article above has “proven” examples of how competition is good such as these gems:

2. Innovation Is FosteredThat is the entire extent of the article’s explanation on these “proven” reasons. As you might guess from the reflection section, all of these can be done without competition. The other reasons fall into the same bucket. A quippy heading and one paragraph of explanation without any mention of evidence.

Innovation is important to you and your company because competition makes you constantly innovate. When your business is number one or the only one, innovation tends to be ignored. Innovation is incredibly important and is woven into the fabric of what great businesses do.

5. Reminds You to Focus on Your Key Customers

Competition reminds you every now and then to focus on your key customers. After all, they are the reason why there is more cash inflow. By focusing on them you also come up with ways to serve them better.

6. Provides the Opportunity to Serve

Indeed when you have various customers you have a huge task to always serve. Competition makes it very mandatory to keep serving and seeking new ways to serve your customers.

Obviously, a general Google search and survey of the first page isn’t the best way to go about this. The same search on Google Scholar, which comprises research from academics in the form of journal articles and books, returns less enthusiasm on the benefit of competition.

For example, one book on the link between competition and the common good returned the following,

In The Darwin Economy, Robert Frank predicts that within the next century Charles Darwin will unseat Adam Smith as the intellectual founder of economics. The reason, Frank argues, is that Darwin’s understanding of competition describes economic reality far more accurately than Smith’s. Far from creating a perfect world, economic competition often leads to “arms races,” encouraging behaviors that not only cause enormous harm to the group but also provide no lasting advantages for individuals, since any gains tend to be relative and mutually offsetting. The good news is that we have the ability to tame the Darwin economy. The best solution is not to prohibit harmful behaviors but to tax them. By doing so, we could make the economic pie larger, eliminate government debt, and provide better public services, all without requiring painful sacrifices from anyone. That’s a bold claim, Frank concedes, but it follows directly from logic and evidence that most people already accept.A journal article on the link between competition and innovation returned this,

The relation between the intensity of competition and R&D investment has received a lot of attention, both in the theoretical and in the empirical literature. Nevertheless, no consensus on the sign of the effect of competition on innovation has emerged. This survey of the literature identifies sources of confusion in the theoretical debate.So I am unconvinced by anything I am currently reading or finding. That search will continue until I’m fully satisfied, but I don’t foresee any plausible evidence turning up at this point.

Goal Attainment

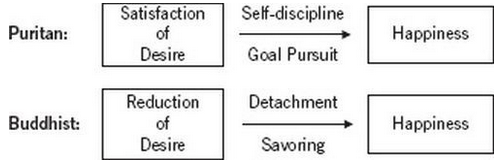

All of this brings us up to goal attainment and the connection that is becoming more and more clear to me as I search for answers to these questions.

If you read up on the human condition and research on overall well-being among humans, a pattern will emerge that paints us as goal-seeking entities. Our brains and bodies are basically set up to allow us to satisfy desires and goals through our actions.

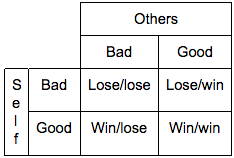

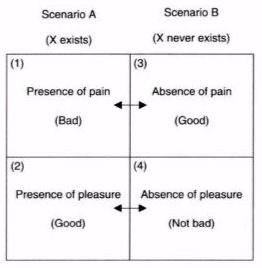

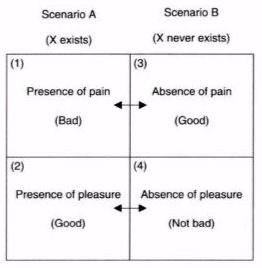

Alfie Kohn in his book No Contest , an extensive review of competition and its lack of benefits, settles on defining competition as “mutually exclusive goal attainment”. This is important to understand relative to the other two options, which are independent goal attainment and cooperative goal attainment in which one is dependent on others to attain a goal.

This definition means that if I attain a goal, another individual is not capable of attaining that same goal. Most sport competitions are set up in this manner. If I win a tennis match, then my competitor is, by the nature of the event, not capable of also winning the match. Our goals are mutually exclusive.

What I take away from this connection is a dramatic reevaluation of goals. This separation of various ways in which to achieve goals does not tell us which goals are valuable or worthwhile. We can achieve goals in a mutually exclusive manner, an independent manner, or dependent manner (cooperation), but this doesn’t tell us whether those goals should be pursued.

But recognizing these different ways of goal attainment immediately begs the question, “Why pursue competitive goals?” If they are mutually exclusive, why not simply choose goals that can be achieved independently or through cooperation?

Many will often fall back and rely on the simple answer, “Competition makes us better. It brings out our best.” This is both an uncritical answer and at the same time shows a shallow and superficial way of thinking about these questions.

Makes us better how, exactly?

If we are talking about athleticism, which is probably the first thought related to betterment through competition, then we can point out that we can all be more athletic (better) without resorting to mutually exclusive goals. If I want run faster, that does not preclude your doing so. If I want to be stronger and lift more weight, that does not preclude your doing so. Those are independent goals, not competitive goals.

If we are talking about intellect and knowledge acquisition in an educational setting, which is probably the second thought that springs to mind with relation to betterment through competition, we run into the same problem. My becoming smarter, more knowledgeable, or more creative does not prevent you from becoming so either.

What is mutually exclusive is any kind of ranking system of who is smartest or who is most knowledgeable. We can set up an education system (we have such a one currently) that decides who is “best” in class through testing and then rank students from one to “n” in order to screen them. My being first in class is then mutually exclusive of your being first in class. This is a different goal than gaining more knowledge or skill, though, and it is very important to recognize that difference.

Worthwhile Goals

So what goals are worth attaining? What does this all point to?

If you read my writing with any regularity you can probably guess.

Goals that benefit yourself and others while not harming anyone intentionally or with any foreseeableness, at least not in a major way, are most worthwhile.

Some of these goals might include hedonistic pleasure, novel experiences, deep connections to others, creative contributions to society through work and the pursuit of mastery, searching for personal meaning and life purpose, flow-state experiences, and a sense of contentedness and life satisfaction.

None of these require competition. All of these can be attained through independent or cooperative means. Examine your goals carefully. Reevaluate if necessary.

I’d like to end with one very clear point on worthwhile goals. Almost all of the truly world changing goals and many “everyday” altruistic goals aimed at bettering others’ lives will necessitate cooperation, not competitive or independent work.

As a very simple example, let’s take my own writing, which largely aims to teach and share knowledge that I feel is valuable to making the world better by increasing everyone’s well-being.

For many, many years, I have written independently. However, as I mature and relinquish this sense self-sufficiency in my writing and work, I am able to realize that writing an article is different goal from writing the best article possible to help the most number of people. In order to do that, I need to cooperate with others.

I simply cannot write the best article possible alone.

I depend on the help of others in the form of editing, revisions, encouragements and injections of ideas and perspectives new and different from my own that often illuminate obvious counterpoints or objections to my thoughts. By cooperating, the most obvious holes and gaps are plugged and any thesis I maintain is made stronger.

This same point about the benefits of cooperation over competition holds true for any worthwhile goal I can think of, which is the central point of this article. In Matt Ridley’s words, “Self-sufficiency is another word for poverty”.

Published on July 01, 2016 02:44

June 25, 2016

Having Children: A Dialogue (Also on Kindle)

Below is about 4,700 words on deciding whether or not having children is a good idea. Because this started as a blog post, but took so long to write and became so long, Rebecca and I have both decided to publish it in its entirety as a blog post while also publishing it as a very short Kindle eBook for $2.99. Whether you read it for free here or decide to purchase it is entirely up to you, but we would obviously appreciate your support if you found anything helpful, useful, or enlightening from this dialogue. Click here to visit the Amazon Kindle page or click the image below.

Preface

Preface

Kyle: I have personally wanted to be married and have kids since I can remember. For most of my life it was simply a want, a desire, not reflected on or thought about in any capacity. It was and still is mostly supported by my family, friends, acquaintances, and society as an expected pursuit and worthwhile desire.

I was raised by parents that did not try to influence me too much in anything related to politics, religion, or family life. As a result, I just went to school, learned those lessons (mostly liberal), and began reading about topics I was uncertain of and wanted to know more about. It was only reasonable to me to ask questions about the large issues in life, with children being one of the largest decisions any of us make.

As I read more about bringing a life into existence and the ethical implications of that choice, I became more and more convinced it could not reasonably be viewed as ethical or the moral thing to do. This belief crystallized more and more over the last couple of years and I suddenly found myself in a position of having to throw off a two-decade-old wish.

It was at this point that I met Rebecca and began to discuss these ideas with her. She was able to listen to and hear all of my reasons and arguments for no longer wanting children and rationally come to a different conclusion on the ethicality of the decision. It was because of this openness to conversation and her obvious use of all aspects in decision making - emotion, empathy, reason, evidence, logic, optimism, expectation - that I decided to explore this particular decision in written form with her.

We have attempted to figure out exactly how the decision to have a child benefits the child itself, the parents, the community and greater world beyond ourselves. In doing so, we primarily rely on a moral system based on the ethics of care and well-being, both of which can be argued against as the most rational basis of morality, but which science, psychology, and philosophy are all mounting more and more evidence in favor of and select as the proper norm.

Rebecca: For me, wanting to be married and have children has never been a question, thought, or consideration. It has been a drive and a focus for as long as I can remember. It is also the only area of my life that had originated and existed largely without question or self-exploration.

In that sense, the intention to raise a family with a partner without asking myself why is largely inconsistent with the rest of my character. I’d grown up in a household where I was always encouraged to read, ask, and seek out answers to my questions. It ultimately struck me as odd that I had no questions about what I had always seen as the pathway to adulthood and happiness.

As an educator, I have always emphasized that my students need to have reasons, explanations, and evidence to support their claims and decisions. I realized that I had not done the same with my own hopes for marriage and children, that I had committed the error of “do as I say, not as I do”.

When Kyle and I started discussing education, improving the world, and our personal rationalizations and goals, I started to ask the questions that I had never quite verbalized previously. This has led me to explore the ideas presented below in written dialogue with him.

We both hope that others find this conversation, in terms of content as well as construction through honest reflection, openness, and communication, helpful and encouraging as a way of engaging in their own dialogues and explorations about other areas of life.

Having Children: A Dialogue

Kyle: Let’s start with the question of the benefit to the actual future child a parent brings into the world. Do you see coming into existence as ever being of benefit to the child itself?

Rebecca: I have to operate on assumptions to answer this question. If we’re assuming that living is better than not living, then yes. If it is better to exist than not exist, coming into existence is better for the life of the child because of the experiences and opportunities that life has to offer. This child can learn and grow and travel and have a positive impact, all of which will benefit the child itself.

Kyle: So many questions. First, why are you starting from the assumption that living is better than not living?

Second, if coming into existence is good for the child itself, many people have considered the idea that we have an obligation to create life. Should we not simply create as many children as possible? If it is a good in itself, we might consider that an obligation exists to simply propagate as many children as we can.

Last, having a positive impact does not necessarily benefit the child. I need more explanation on how that is good for the child itself. Obviously, a “positive” impact by definition would be good for someone or something else, but I don’t see the connection to that being good for the child or a reason to bring it into existence in the first place.

Rebecca: Good questions. From a species perspective, living is better than not living. Obviously humans need to reproduce if the human species is going to survive, so this means that the child’s existence doesn’t inherently benefit the child, but humanity.

However, I wouldn’t say we have an obligation to create life because the benefit to humanity with this child only exists if the parents are making a deliberate choice to raise and rear the child with clear aims of making the world a better place. This would impact parenting and educational decisions about the child. Having children for the sake of having children just increases the world’s population, which is already increasing more quickly than is currently sustainable.

If parents decide to have a child and are raising the child to have a positive impact on the planet and on humanity, that is a good reason to bring a child into existence. The child’s participation in making the world better and then inhabiting a better world is ultimately good for the child.

Kyle: So you mention the benefit to the species, which would be a slightly different discussion altogether relative to the current one on whether bringing the child into existence benefits it at all. You also mention population sustainability, which has the same issue.

What it sounds like is that you are saying the child coming into existence benefits others and is therefore of instrumental use or a means to an end. I don’t actually see the connection between coming into existence versus not existing at all being an overall benefit to the child as you seem to surmise in your very last sentence. Perhaps, the world (of conscious humans) will be better overall as a result and therefore the already existing child will be better off, but that still isn’t the same as saying a non-existent child would be better off by coming into the world, only that once here, it is in the child’s interest to make it better.

Overall, I’d summarize this discussion as concluding that deciding to have a child is ultimately a selfish decision on either the parents’ part or the larger group (community, society, world) in order to benefit themselves. Do you think that is a fair summary and would you agree?

Rebecca: That’s a fair summary and yes, I agree with it. Since you’ve touched on selfishness, is having a child ever not selfish?

Kyle: Definitely, but I think it’s careful to understand the meaning of selfish in this context, because its opposite does not imply good in this case. Having children for selfish reasons just means that you have them for yourself and not for others. We could definitely have children for altruistic purposes, in that we are having children for the sake of others, while still holding to the idea that having children is no benefit to the child itself, but rather other living humans.

Rebecca: Thinking about having children for yourself means talking about the ways adults love children. We love children in the ways that we want to love everyone, but that open, accepting, deep love might be easier with a child. Children, especially young children, are largely devoid of judgment and instead completely accepting of the people around them, which is something that we want with all people in all of our interactions. However, that’s often really difficult to express, unfortunately, and I think there are a lot of sociocultural and perhaps environmental reasons for that. So in this way, having children is a way of loving and being loved in the ways that we truly want to experience.

Kyle: I certainly agree. In that sense, having a child is often a “second best option”, meaning we may feel less compelled to have a child for those reasons if we could experience that child-like loving relation with adults. The fact that we can experience it with children almost gets us out of the work necessary to experience it with adults. We can often get quite hurt or rejected by adult relationships in which we open ourselves up and allow ourselves to be vulnerable. After a couple false starts, it can be seen as easier to seek that relation with a newborn than another potentially painful letdown from an adult. In a way, it is throwing in the towel with adult relationships and choosing the easier option.

I think this point also connects to some of the reasons parents and children often struggle to have genuine relationships as the children age. A newborn can be loved as an “object of affection”, in which the parents lavish all their uncensored love and wishes on the child. This creates a kind of habit or routine way of interacting with their children that can be hard for parents to change as that object of affection transforms and becomes a subject. It is much more difficult to love a “subject of affection” than an object of affection for the very reason that it (he or she once a subject) can choose to receive or reject that affection, respond or not to that affection, and reciprocate or not that affection.

Parents that cannot change their style of loving from that of loving a non-fully conscious object to a fully conscious subject seem to struggle more than others in my experience. These are the parents that you see and hear about that are trying to force their desires and goals onto their children, that love conditionally based on their children’s achievement, and that potentially lose all relations with their children as the children age and decide they no longer wanted to be treated in that manner.

Rebecca: That’s a fair assessment. I think you’re right about the need to transition from loving a child as an object of affection to a subject, especially because the hopes, dreams, and desires of all subjects of affection, whether adults or children, need to be valued and considered in any relationship. That’s where, as you say, adult relationships are difficult. They require dialogue and communication that is often unfortunately neglected when we instead develop relationships with children.

Having children is potentially good for parents struggling in their own relationships, however, because children provide common ground for experiences, activities, and even hopes and dreams that the parents can share with each other. Ultimately, those parents are probably better off working on their own relationship rather than using children as a way of forming a better relationship with each other. In my experience, it’s rather common for couples to end marriages after their children, those subjects or objects of affection, have developed into autonomous individuals who may not fulfill the same need for their parents as they once did. The relationship has changed.

Even though we know that having children is a huge decision, and not only because it completely changes adult relationships, we still expect that young couples want to have children and will choose to do so sooner rather than later. We have clearly been socialized into these beliefs. I don’t think most people want to think about having children as the “default” action, usually after marriage, but it seems to be that way. Why the emphasis on having children and being parents?

Kyle: The obvious answer is clearly that it is for species survival and we have powerful biological drives to do so. This is not a satisfying answer to me though because we have strong, powerful urges to do lots of things as a result of our biology. For one, I would classify the urge to sexually assault in any and all capacities, including rape, to be a powerful urge that many or even most men feel as a result of biology and the drive to reproduce and propagate their genes in offspring. But. That is no longer the default mode of action or seen as acceptable behavior and has dramatic consequences because we have all used reason and empathy to understand that it hurts others after some reflection. This reflection now happens at both the individual level and societal level.

That is exactly what I think needs to happen now. People should be using reason, empathy, and reflection to proactively decide to have kids or not. Continuing to have kids by default is not a responsible choice. Yes, it is the status quo. And yes, society does exert huge pressures. Particularly on married couples and women more specifically, but that is not a valid or good reason to have children.

Instead, we should focus on all three levels of people involved in our decision. The best interests of the future child, our spouse or partner if they will be involved, and society or humanity at large. We’ve already covered the idea that the best interest of the child is simply not to exist at all and that the best interest of the partner or spouse will be dependent on them and you in the relationship you have together.

Some people feel they simply can’t live a rewarding and fulfilling life without children and for them, having a child is an act of “self-care”. That is probably fine or okay when both parents go into the decision recognizing the reasons for it and not under false beliefs about what they are doing and why.

Last, and I would say most importantly, is the impact on society and humanity at large the decision to have children has. The two biggest impacts for me are that having a child is the single largest addition to your carbon footprint you will ever have direct control over and, even more importantly, the amount of money it costs to raise a child in the developed world can be better spent helping hundreds or thousands of people in the developing world, many of whom already have children that exist and whom they deeply care about and would be heartbroken to lose due to preventable causes like malaria, TB, HIV, hunger, dehydration, etc. and which my money can go towards alleviating.

Rebecca: Definitely important to consider society and humanity in the context of this discussion. I think it’s an appropriate time to note that neither of us have children, though I hope to eventually. I don’t disagree that the amount of money it could cost to raise a child in the developed world is badly needed elsewhere and would have incredibly positive impacts on the lives of people in developing countries. At the same time, though, I see it as partially my responsibility, as someone who cares about the world and improving the world, to have children in order to develop more people who care about the world and who will work to create a better and more peaceful world for all those who inhabit it.

As an educator, I have some ability to develop such individuals, but there’s definitely more I could do with my own children than others’ children, particularly because a teacher’s direct influence is often only a year long. Parenting lasts a lifetime. It’s important to me to continue impacting the world in positive ways and I think having a child, for me, is a way to do that. Of course, there are all sorts of parenting implications and discussions to consider, but having children in order to create a better world is a deliberate reason to have children rather than a default response to social pressure and cultural attitudes.

Kyle: I think this is the argument I am most open to be persuaded by, especially as mentioned earlier if the decision is discussed openly between both parents (or reasonably reflected on by a single parent) and agreed on beforehand. The biggest issue here is simply using the child as a means to an end, also mentioned above. This is no small matter. Many people, good reasonable people at that, could find this abhorrent. I personally do not, but there will be much disagreement on this line of reasoning among rational people and it really does seem to be the only rational reason for having children that isn’t selfish or simply a parental need for a fulfilling life.

So while I would be open to persuasion on from this argument by my own wife (or even the personal need argument at the end of the day), I do think it’s worth mentioning and thinking heavily about expected outcomes here. We have a very reasonable idea of what money can do to benefit people who alive now when donated to effective charities and NGOs. Deciding to have children and raise them to benefit the world may or may not be as reasonably expected depending on parental circumstances.

I do think, that as you said, being an educator who thinks and learns about ways of making the world a better, more peaceful place does give someone in your particular situation a very likely chance of cultivating a child who could impact the world in immensely positive ways. However, they would need to impact it more than your potential donations would impact it, which is a large task. Furthermore, there is always the chance that your child could be born with genetic abnormalities that lead to disease, disability, early death, or even psychopathic tendencies that research shows afflict about one percent of the population on average. They could also be a perfectly healthy, normal, and capable child who grows up to the age of 21, graduates university having received hundreds of thousands of dollars in your support, only to be hit by a drunk driver the next day and die before being able to return the time, energy, and finances you essentially invested in them as a future world impactor. There are simply a number of unknowns and uncertainties that could potentially happen even if you are perfectly capable of raising such a child and instilling humanistic and altruistic attitudes and dispositions in them.

I guess what this is getting at is risk aversion. I feel open and accepting of your argument, but feel your “entrepreneurial attitude” as it were is perhaps too optimistic compared to the safe and near certain prospect of charitable donation and immediate alleviation of suffering today versus two decades from now.

Rebecca: I can agree with your point about optimism. There are, of course, a whole number of “what ifs” and “maybes” involved in any major decision like this. There is a lot of uncertainty. I understand and accept that. There’s an element of the “self-care” argument that you mentioned above involved in my thinking, too. The most important aspect of the decision for me, though, is that it is an actual decision. It’s a choice. Your choice not to have children, or to later be persuaded by one argument or another, is an active decision to do X rather than Y. We are both looking at this question with a real consideration for humanity as a whole.

The world can benefit from charitable donations to a wide range of causes, but also from the cultivation and development of people who aim to improve the world. That’s the job of both educators and parents. My goals as an educator are to help children grow into people who work to benefit those around them and increase their well-being; the goal is the same when I consider being a parent. I personally have a difficult time separating my overall professional goals from any other decisions I can make, especially when humanity is concerned.

Having children and raising them in this way certainly does not excuse me from donating money to NGOs or organizations that can make a tangible impact now, today. This is not a case of choosing one over the other as much as it is a case of choosing both, to the extent that anyone can. I am less able to donate money in choosing to raise children simply because of the cost of raising children, but the impact on the world that any child has the potential to make could be extraordinary. Basing a decision to have children on potential impact, rather than the guarantees that we might see elsewhere, does relate to your point about using children as a means to an end. However, it also makes sense to me in terms of an overarching goal of developing a better, more peaceful world.

Kyle: You’ve just touched on balancing between choosing to both have a child and donate, so I can guess at your answers, but I have a couple questions anyway. Given what you just said about the potential for “extraordinary impact” that any child has and a desire to shape children for longer than the one year you often get as a teacher, why not simply invest all your money into having as many children as your finances allow without donating to maximize that extraordinary impact potential or, conversely, have no children at all and invest all your money and time into some kind of experimental school where you could follow the children as teacher from kindergarten through 12th grade and raise anywhere from 10 to 40 children in the process in some sort of cohort type model?

Rebecca: I’m most intrigued by the second idea, so I’ll address that first. I would love to be part of an experimental school like that. However, I definitely don’t have the investment capital right now to fund such a project. By the time I do have that capital, I’m not likely to be a teacher any more! To the first point, there’s the necessity of balance. I don’t think having as many children as possible allows you to be as good of a parent as you would be with fewer children.

Kyle: That seems sensible. I guess in the spirit of bringing this to a close, I can only think of a couple of other things to talk about. The study of happiness or well-being is getting better and better over time. Quite a bit of research reliably shows that parents are less happy on average than non-parents, but married people are more happy than non-married people on average. Do you have any thoughts on this type of research in regards to deciding on kids once married?

Rebecca: I think quite a bit of it has to do with socialization, which I mentioned earlier. We have a view of what we’re expected to do from an early age and that influences the way that we view ourselves. For many people, marriage, home ownership, and having children are probably a very large part of their self-concept. Research also shows that we need congruence between self-concept and our actions in order to feel truly satisfied in our lives.

We can also talk about the aspects of our lives that incentivize having children. Single-family homes are deliberately designed and marketed with families in mind. Even though we desperately need to modernize our view of what constitutes family, I expect most people still carry an image of mother, father, two kids, and a dog. Governments provide tax breaks for having children. Restaurant menus, museum admissions, and movie theatres are all very responsive to a highly traditional idea of family, which means it is part of our lives everywhere we turn. I think it’s easy for people to see themselves and their goals in terms of fitting into a world designed like that, and so they have children without thinking about it any further.

Kyle: Yeah, exactly. It’s my hope people start to think about that stance beyond their own decision as well. It’d be nice to see things like children being incentivized by government programs looked at quite hard. One easy solution to the falling numbers of a nation-state’s population if you take away incentives to have kids is to allow more immigration for people who want to come to a country like the United States. That seems like a “no brainer” to me for a number of reasons. World GDP is estimated to benefit from more migration of human labor than capital and that is no trifling sum.

Being an expat worker for much of my adult life who has moved simply to get a better quality of life, it is easy to understand from my perspective that most people want the same thing. Many families with young children and without would happily move to the developed world to fill the population gap that would be created and bring with them revitalizing ideas and economic growth. It essentially lowers the population at the same time that GDP increases, leading to a massive gain in world GDP per capita.

Anyway, that is getting slightly down a different path, but the point is that the way our states and governments are organized assume that having children is the correct decision for most families. This non-critically established belief may not turn out to be true if some of the points in this dialogue are taken seriously, so the issue to have a child is not just an individual parent’s or parents’ problem, but a state and world problem as well.

In summarizing my viewpoints on this, coming into existence isn’t a benefit to the actual future child, so we are doing them no favors. The parents themselves could be better off through greater life satisfaction due to a sense of congruence that is almost certainly socioculturally created and socialized into us. They will experience less positive affect on average day to day as research shows and could possibly feel greater overall connection in their lives through their relationships with their children, however, that could be at the detriment of more meaningful and deeper adult connection as we looked at earlier. Finally, the world could be better off or not depending on unknown and uncertain variables. I would say the facts point to large, certain benefits to the world if we choose not to have children and also reevaluate certain legal, political, and social pressures, but agree that we could also produce benevolent, impactful, and world changing children if that was indeed our goal as parents and something we legitimately worked hard to achieve.

Anything you want to add or summarize in closing?

Rebecca: Your summary provides an accurate picture of my thoughts, as well. The take-home message from this conversation for me has been the importance of truly evaluating our goals and the ways we try to achieve them, especially when deciding to bring another person into this world (or not). I hope that we begin to see a lot more authentic thinking, communication, and dialogue within society about such an important decision as we work towards developing a better, more peaceful world.

Further Reading

The Age of Sustainable Development

Altruism

Better Never to Have Been

Caring

Doing Good Better

Grit and Authenticity

Money, marriage, kids

Practical steps for self-care

A Primer in Positive Psychology

The Psychology of Desire

Strangers Drowning Thanks for reading. If you found it helpful in deciding to have children of your own (or not), please do leave a comment below and consider purchasing the Kindle version for $2.99 to show support.

Preface

Preface

Kyle: I have personally wanted to be married and have kids since I can remember. For most of my life it was simply a want, a desire, not reflected on or thought about in any capacity. It was and still is mostly supported by my family, friends, acquaintances, and society as an expected pursuit and worthwhile desire.

I was raised by parents that did not try to influence me too much in anything related to politics, religion, or family life. As a result, I just went to school, learned those lessons (mostly liberal), and began reading about topics I was uncertain of and wanted to know more about. It was only reasonable to me to ask questions about the large issues in life, with children being one of the largest decisions any of us make.

As I read more about bringing a life into existence and the ethical implications of that choice, I became more and more convinced it could not reasonably be viewed as ethical or the moral thing to do. This belief crystallized more and more over the last couple of years and I suddenly found myself in a position of having to throw off a two-decade-old wish.

It was at this point that I met Rebecca and began to discuss these ideas with her. She was able to listen to and hear all of my reasons and arguments for no longer wanting children and rationally come to a different conclusion on the ethicality of the decision. It was because of this openness to conversation and her obvious use of all aspects in decision making - emotion, empathy, reason, evidence, logic, optimism, expectation - that I decided to explore this particular decision in written form with her.

We have attempted to figure out exactly how the decision to have a child benefits the child itself, the parents, the community and greater world beyond ourselves. In doing so, we primarily rely on a moral system based on the ethics of care and well-being, both of which can be argued against as the most rational basis of morality, but which science, psychology, and philosophy are all mounting more and more evidence in favor of and select as the proper norm.

Rebecca: For me, wanting to be married and have children has never been a question, thought, or consideration. It has been a drive and a focus for as long as I can remember. It is also the only area of my life that had originated and existed largely without question or self-exploration.

In that sense, the intention to raise a family with a partner without asking myself why is largely inconsistent with the rest of my character. I’d grown up in a household where I was always encouraged to read, ask, and seek out answers to my questions. It ultimately struck me as odd that I had no questions about what I had always seen as the pathway to adulthood and happiness.

As an educator, I have always emphasized that my students need to have reasons, explanations, and evidence to support their claims and decisions. I realized that I had not done the same with my own hopes for marriage and children, that I had committed the error of “do as I say, not as I do”.

When Kyle and I started discussing education, improving the world, and our personal rationalizations and goals, I started to ask the questions that I had never quite verbalized previously. This has led me to explore the ideas presented below in written dialogue with him.

We both hope that others find this conversation, in terms of content as well as construction through honest reflection, openness, and communication, helpful and encouraging as a way of engaging in their own dialogues and explorations about other areas of life.

Having Children: A Dialogue

Kyle: Let’s start with the question of the benefit to the actual future child a parent brings into the world. Do you see coming into existence as ever being of benefit to the child itself?

Rebecca: I have to operate on assumptions to answer this question. If we’re assuming that living is better than not living, then yes. If it is better to exist than not exist, coming into existence is better for the life of the child because of the experiences and opportunities that life has to offer. This child can learn and grow and travel and have a positive impact, all of which will benefit the child itself.

Kyle: So many questions. First, why are you starting from the assumption that living is better than not living?

Second, if coming into existence is good for the child itself, many people have considered the idea that we have an obligation to create life. Should we not simply create as many children as possible? If it is a good in itself, we might consider that an obligation exists to simply propagate as many children as we can.

Last, having a positive impact does not necessarily benefit the child. I need more explanation on how that is good for the child itself. Obviously, a “positive” impact by definition would be good for someone or something else, but I don’t see the connection to that being good for the child or a reason to bring it into existence in the first place.

Rebecca: Good questions. From a species perspective, living is better than not living. Obviously humans need to reproduce if the human species is going to survive, so this means that the child’s existence doesn’t inherently benefit the child, but humanity.

However, I wouldn’t say we have an obligation to create life because the benefit to humanity with this child only exists if the parents are making a deliberate choice to raise and rear the child with clear aims of making the world a better place. This would impact parenting and educational decisions about the child. Having children for the sake of having children just increases the world’s population, which is already increasing more quickly than is currently sustainable.

If parents decide to have a child and are raising the child to have a positive impact on the planet and on humanity, that is a good reason to bring a child into existence. The child’s participation in making the world better and then inhabiting a better world is ultimately good for the child.

Kyle: So you mention the benefit to the species, which would be a slightly different discussion altogether relative to the current one on whether bringing the child into existence benefits it at all. You also mention population sustainability, which has the same issue.

What it sounds like is that you are saying the child coming into existence benefits others and is therefore of instrumental use or a means to an end. I don’t actually see the connection between coming into existence versus not existing at all being an overall benefit to the child as you seem to surmise in your very last sentence. Perhaps, the world (of conscious humans) will be better overall as a result and therefore the already existing child will be better off, but that still isn’t the same as saying a non-existent child would be better off by coming into the world, only that once here, it is in the child’s interest to make it better.

Overall, I’d summarize this discussion as concluding that deciding to have a child is ultimately a selfish decision on either the parents’ part or the larger group (community, society, world) in order to benefit themselves. Do you think that is a fair summary and would you agree?

Rebecca: That’s a fair summary and yes, I agree with it. Since you’ve touched on selfishness, is having a child ever not selfish?

Kyle: Definitely, but I think it’s careful to understand the meaning of selfish in this context, because its opposite does not imply good in this case. Having children for selfish reasons just means that you have them for yourself and not for others. We could definitely have children for altruistic purposes, in that we are having children for the sake of others, while still holding to the idea that having children is no benefit to the child itself, but rather other living humans.

Rebecca: Thinking about having children for yourself means talking about the ways adults love children. We love children in the ways that we want to love everyone, but that open, accepting, deep love might be easier with a child. Children, especially young children, are largely devoid of judgment and instead completely accepting of the people around them, which is something that we want with all people in all of our interactions. However, that’s often really difficult to express, unfortunately, and I think there are a lot of sociocultural and perhaps environmental reasons for that. So in this way, having children is a way of loving and being loved in the ways that we truly want to experience.

Kyle: I certainly agree. In that sense, having a child is often a “second best option”, meaning we may feel less compelled to have a child for those reasons if we could experience that child-like loving relation with adults. The fact that we can experience it with children almost gets us out of the work necessary to experience it with adults. We can often get quite hurt or rejected by adult relationships in which we open ourselves up and allow ourselves to be vulnerable. After a couple false starts, it can be seen as easier to seek that relation with a newborn than another potentially painful letdown from an adult. In a way, it is throwing in the towel with adult relationships and choosing the easier option.

I think this point also connects to some of the reasons parents and children often struggle to have genuine relationships as the children age. A newborn can be loved as an “object of affection”, in which the parents lavish all their uncensored love and wishes on the child. This creates a kind of habit or routine way of interacting with their children that can be hard for parents to change as that object of affection transforms and becomes a subject. It is much more difficult to love a “subject of affection” than an object of affection for the very reason that it (he or she once a subject) can choose to receive or reject that affection, respond or not to that affection, and reciprocate or not that affection.

Parents that cannot change their style of loving from that of loving a non-fully conscious object to a fully conscious subject seem to struggle more than others in my experience. These are the parents that you see and hear about that are trying to force their desires and goals onto their children, that love conditionally based on their children’s achievement, and that potentially lose all relations with their children as the children age and decide they no longer wanted to be treated in that manner.

Rebecca: That’s a fair assessment. I think you’re right about the need to transition from loving a child as an object of affection to a subject, especially because the hopes, dreams, and desires of all subjects of affection, whether adults or children, need to be valued and considered in any relationship. That’s where, as you say, adult relationships are difficult. They require dialogue and communication that is often unfortunately neglected when we instead develop relationships with children.

Having children is potentially good for parents struggling in their own relationships, however, because children provide common ground for experiences, activities, and even hopes and dreams that the parents can share with each other. Ultimately, those parents are probably better off working on their own relationship rather than using children as a way of forming a better relationship with each other. In my experience, it’s rather common for couples to end marriages after their children, those subjects or objects of affection, have developed into autonomous individuals who may not fulfill the same need for their parents as they once did. The relationship has changed.

Even though we know that having children is a huge decision, and not only because it completely changes adult relationships, we still expect that young couples want to have children and will choose to do so sooner rather than later. We have clearly been socialized into these beliefs. I don’t think most people want to think about having children as the “default” action, usually after marriage, but it seems to be that way. Why the emphasis on having children and being parents?

Kyle: The obvious answer is clearly that it is for species survival and we have powerful biological drives to do so. This is not a satisfying answer to me though because we have strong, powerful urges to do lots of things as a result of our biology. For one, I would classify the urge to sexually assault in any and all capacities, including rape, to be a powerful urge that many or even most men feel as a result of biology and the drive to reproduce and propagate their genes in offspring. But. That is no longer the default mode of action or seen as acceptable behavior and has dramatic consequences because we have all used reason and empathy to understand that it hurts others after some reflection. This reflection now happens at both the individual level and societal level.

That is exactly what I think needs to happen now. People should be using reason, empathy, and reflection to proactively decide to have kids or not. Continuing to have kids by default is not a responsible choice. Yes, it is the status quo. And yes, society does exert huge pressures. Particularly on married couples and women more specifically, but that is not a valid or good reason to have children.

Instead, we should focus on all three levels of people involved in our decision. The best interests of the future child, our spouse or partner if they will be involved, and society or humanity at large. We’ve already covered the idea that the best interest of the child is simply not to exist at all and that the best interest of the partner or spouse will be dependent on them and you in the relationship you have together.

Some people feel they simply can’t live a rewarding and fulfilling life without children and for them, having a child is an act of “self-care”. That is probably fine or okay when both parents go into the decision recognizing the reasons for it and not under false beliefs about what they are doing and why.

Last, and I would say most importantly, is the impact on society and humanity at large the decision to have children has. The two biggest impacts for me are that having a child is the single largest addition to your carbon footprint you will ever have direct control over and, even more importantly, the amount of money it costs to raise a child in the developed world can be better spent helping hundreds or thousands of people in the developing world, many of whom already have children that exist and whom they deeply care about and would be heartbroken to lose due to preventable causes like malaria, TB, HIV, hunger, dehydration, etc. and which my money can go towards alleviating.

Rebecca: Definitely important to consider society and humanity in the context of this discussion. I think it’s an appropriate time to note that neither of us have children, though I hope to eventually. I don’t disagree that the amount of money it could cost to raise a child in the developed world is badly needed elsewhere and would have incredibly positive impacts on the lives of people in developing countries. At the same time, though, I see it as partially my responsibility, as someone who cares about the world and improving the world, to have children in order to develop more people who care about the world and who will work to create a better and more peaceful world for all those who inhabit it.

As an educator, I have some ability to develop such individuals, but there’s definitely more I could do with my own children than others’ children, particularly because a teacher’s direct influence is often only a year long. Parenting lasts a lifetime. It’s important to me to continue impacting the world in positive ways and I think having a child, for me, is a way to do that. Of course, there are all sorts of parenting implications and discussions to consider, but having children in order to create a better world is a deliberate reason to have children rather than a default response to social pressure and cultural attitudes.

Kyle: I think this is the argument I am most open to be persuaded by, especially as mentioned earlier if the decision is discussed openly between both parents (or reasonably reflected on by a single parent) and agreed on beforehand. The biggest issue here is simply using the child as a means to an end, also mentioned above. This is no small matter. Many people, good reasonable people at that, could find this abhorrent. I personally do not, but there will be much disagreement on this line of reasoning among rational people and it really does seem to be the only rational reason for having children that isn’t selfish or simply a parental need for a fulfilling life.

So while I would be open to persuasion on from this argument by my own wife (or even the personal need argument at the end of the day), I do think it’s worth mentioning and thinking heavily about expected outcomes here. We have a very reasonable idea of what money can do to benefit people who alive now when donated to effective charities and NGOs. Deciding to have children and raise them to benefit the world may or may not be as reasonably expected depending on parental circumstances.

I do think, that as you said, being an educator who thinks and learns about ways of making the world a better, more peaceful place does give someone in your particular situation a very likely chance of cultivating a child who could impact the world in immensely positive ways. However, they would need to impact it more than your potential donations would impact it, which is a large task. Furthermore, there is always the chance that your child could be born with genetic abnormalities that lead to disease, disability, early death, or even psychopathic tendencies that research shows afflict about one percent of the population on average. They could also be a perfectly healthy, normal, and capable child who grows up to the age of 21, graduates university having received hundreds of thousands of dollars in your support, only to be hit by a drunk driver the next day and die before being able to return the time, energy, and finances you essentially invested in them as a future world impactor. There are simply a number of unknowns and uncertainties that could potentially happen even if you are perfectly capable of raising such a child and instilling humanistic and altruistic attitudes and dispositions in them.

I guess what this is getting at is risk aversion. I feel open and accepting of your argument, but feel your “entrepreneurial attitude” as it were is perhaps too optimistic compared to the safe and near certain prospect of charitable donation and immediate alleviation of suffering today versus two decades from now.

Rebecca: I can agree with your point about optimism. There are, of course, a whole number of “what ifs” and “maybes” involved in any major decision like this. There is a lot of uncertainty. I understand and accept that. There’s an element of the “self-care” argument that you mentioned above involved in my thinking, too. The most important aspect of the decision for me, though, is that it is an actual decision. It’s a choice. Your choice not to have children, or to later be persuaded by one argument or another, is an active decision to do X rather than Y. We are both looking at this question with a real consideration for humanity as a whole.

The world can benefit from charitable donations to a wide range of causes, but also from the cultivation and development of people who aim to improve the world. That’s the job of both educators and parents. My goals as an educator are to help children grow into people who work to benefit those around them and increase their well-being; the goal is the same when I consider being a parent. I personally have a difficult time separating my overall professional goals from any other decisions I can make, especially when humanity is concerned.

Having children and raising them in this way certainly does not excuse me from donating money to NGOs or organizations that can make a tangible impact now, today. This is not a case of choosing one over the other as much as it is a case of choosing both, to the extent that anyone can. I am less able to donate money in choosing to raise children simply because of the cost of raising children, but the impact on the world that any child has the potential to make could be extraordinary. Basing a decision to have children on potential impact, rather than the guarantees that we might see elsewhere, does relate to your point about using children as a means to an end. However, it also makes sense to me in terms of an overarching goal of developing a better, more peaceful world.

Kyle: You’ve just touched on balancing between choosing to both have a child and donate, so I can guess at your answers, but I have a couple questions anyway. Given what you just said about the potential for “extraordinary impact” that any child has and a desire to shape children for longer than the one year you often get as a teacher, why not simply invest all your money into having as many children as your finances allow without donating to maximize that extraordinary impact potential or, conversely, have no children at all and invest all your money and time into some kind of experimental school where you could follow the children as teacher from kindergarten through 12th grade and raise anywhere from 10 to 40 children in the process in some sort of cohort type model?

Rebecca: I’m most intrigued by the second idea, so I’ll address that first. I would love to be part of an experimental school like that. However, I definitely don’t have the investment capital right now to fund such a project. By the time I do have that capital, I’m not likely to be a teacher any more! To the first point, there’s the necessity of balance. I don’t think having as many children as possible allows you to be as good of a parent as you would be with fewer children.

Kyle: That seems sensible. I guess in the spirit of bringing this to a close, I can only think of a couple of other things to talk about. The study of happiness or well-being is getting better and better over time. Quite a bit of research reliably shows that parents are less happy on average than non-parents, but married people are more happy than non-married people on average. Do you have any thoughts on this type of research in regards to deciding on kids once married?

Rebecca: I think quite a bit of it has to do with socialization, which I mentioned earlier. We have a view of what we’re expected to do from an early age and that influences the way that we view ourselves. For many people, marriage, home ownership, and having children are probably a very large part of their self-concept. Research also shows that we need congruence between self-concept and our actions in order to feel truly satisfied in our lives.

We can also talk about the aspects of our lives that incentivize having children. Single-family homes are deliberately designed and marketed with families in mind. Even though we desperately need to modernize our view of what constitutes family, I expect most people still carry an image of mother, father, two kids, and a dog. Governments provide tax breaks for having children. Restaurant menus, museum admissions, and movie theatres are all very responsive to a highly traditional idea of family, which means it is part of our lives everywhere we turn. I think it’s easy for people to see themselves and their goals in terms of fitting into a world designed like that, and so they have children without thinking about it any further.

Kyle: Yeah, exactly. It’s my hope people start to think about that stance beyond their own decision as well. It’d be nice to see things like children being incentivized by government programs looked at quite hard. One easy solution to the falling numbers of a nation-state’s population if you take away incentives to have kids is to allow more immigration for people who want to come to a country like the United States. That seems like a “no brainer” to me for a number of reasons. World GDP is estimated to benefit from more migration of human labor than capital and that is no trifling sum.

Being an expat worker for much of my adult life who has moved simply to get a better quality of life, it is easy to understand from my perspective that most people want the same thing. Many families with young children and without would happily move to the developed world to fill the population gap that would be created and bring with them revitalizing ideas and economic growth. It essentially lowers the population at the same time that GDP increases, leading to a massive gain in world GDP per capita.

Anyway, that is getting slightly down a different path, but the point is that the way our states and governments are organized assume that having children is the correct decision for most families. This non-critically established belief may not turn out to be true if some of the points in this dialogue are taken seriously, so the issue to have a child is not just an individual parent’s or parents’ problem, but a state and world problem as well.