Kyle Fitzgibbons's Blog, page 10

September 4, 2016

The Feudalism of America Today

Living in a modern nation-state requires a complex interplay of state centralization, rule of law, and political accountability. The latter two components are necessary constraints on the former and are often carried out by developing institutions that can be labeled either inclusive or extractive. Inclusive institutions tend to create prosperity, while extractive ones tend to ultimately lead to ever increasing concentrations of wealth among an elite who eventually find themselves having to answer to the majority, either in non-violent or violent events, or by simply draining the state of its prosperity over time.

Living in a modern nation-state requires a complex interplay of state centralization, rule of law, and political accountability. The latter two components are necessary constraints on the former and are often carried out by developing institutions that can be labeled either inclusive or extractive. Inclusive institutions tend to create prosperity, while extractive ones tend to ultimately lead to ever increasing concentrations of wealth among an elite who eventually find themselves having to answer to the majority, either in non-violent or violent events, or by simply draining the state of its prosperity over time.State centralization is important for creating a monopoly on force and violence, which can be used through the rule of law to create inclusive institutions that allow citizens to interact freely in the knowledge that their innovations won’t be stolen or extracted by force by those who have the most might. Extractive institutions are those that essentially embrace the idea that “might makes right” and as result often completely stifle innovation and the creation, propagation, and dissemination of new ideas, which might challenge the extractive process that so enriches the empowered elite.

One form of power that is extractive in nature is that of the medieval form of political and military structure known as feudalism. It is defined below:

Feudalism: The dominant social system in medieval Europe, in which the nobility held lands from the Crown in exchange for military service, and vassals were in turn tenants of the nobles, while the peasants (villeins or serfs) were obliged to live on their lord’s land and give him homage, labour, and a share of the produce, notionally in exchange for military protection.The idea that “peasants are obliged to live on their lord’s land and give homage” is largely what exists in today’s America. This might seem dramatic or hyperbolic, but let’s examine it more closely. There are three major ways in which one might see this as true today: labor mobility, income tax, and debt.

Labor Mobility

Free movement of labor (people as workers) is an essential liberty among free people. In its most extreme negation, you have slavery, where people are viewed as property, and just above that you have feudalism, in which peasants are tied to the land they work in order to pay their lord homage. But are people tied to the land in today’s America in the same manner that they were during feudal Europe? In one major way, yes.

People do not have the freedom to move between nations as they please. Some do not even have the freedom to move between states due to restrictions. Of course, these areas of land are much larger than previously, but the fact remains that a person in America cannot simply buy a ticket and fly to North Korea or vice versa, even if they can afford the cost, because of visa and immigration restrictions created by the state powers of those nations. Even movement from America to prosperous nations such as Singapore or South Korea that America is on good terms with, requires huge amounts of work, red tape, and worker restrictions with all sorts of stipulations on what work can and cannot be done with caveats for deportation at all turns.

This is hugely important when capital is given freedom to move between nations. When capital can move, but people cannot, “a race to the bottom” begins. Corporations are able to move their capital to whatever nation will supply the cheapest labor. In recent history, American companies moved their capital to China so as to capitalize on the lower wages workers were willing to earn compared to their American labor counterparts. As China’s labor becomes more expensive and wages rise, we see capital already moving to other nations in and around Southeast Asia, primarily Bangladesh, Thailand, the Philippines, and parts of India. This primarily happens as the incomes of these nations, such as China, rise over time due to increases in real GDP and workers begin to demand higher wages. Rather than acquiesce to demands from labor over wage increases, capital can simply move to a new location.

Once Southeast Asia becomes too expensive, we are likely to see a larger movement into Africa and parts of South America. Of course, we can say that this would eventually lead to some sort of global equilibrium where wages rise among the nations that capital temporarily stops over in. This would happen in the long-run and as Keynes famously said, “In the long run we are all dead.”

Luckily we don’t have to wait for the long-run equilibrium on world wide wage increases. If people were given the freedom to move their labor to nations that had higher wages, they would surely seize it. This is because people as laborers understand that their geographic location accounts for most of their income (60 percent of variability in global incomes). In fact, we see this even though it is technically not legal in places where poor nations border richer ones. Mexico and America, Eastern Europe and Western Europe, India and the UAE, and the Philippines and Singapore. All of these nations have huge migrations of people trying to escape being tied to their own lands that suffer from poorer working conditions and poverty.

This begs the question on migration from America for a better a life. America is quite rich already, but many Americans would still be better off trading their labor in other nations if given the opportunity. Allowing this to happen more freely would also create “a race to the top” as nations and corporations would be forced to pay labor more in order to attract the best workers available today, rather than tomorrow in some distant global wage equilibrium described above in the “race to the bottom” scenario that currently operates.

Not only would this freer movement of labor benefit Americans, but it would also benefit the entire world. Many economists agree this would increase world GDP somewhere between two and three times what it currently is. Some have even stated that it would be “the world’s best anti-poverty program,” exceeding even the current benefits seen from free trade, which is really just free movement of capital.

Income Tax

A lack of labor mobility keeps people tied to the land in which they are born, creates a “race to the bottom” in wages, and prevents world GDP from increasing as quickly as it could otherwise and therefore hurting efforts to alleviate world poverty. However, one might argue that within a given nation, there isn’t much feudalism happening. That free labor movement is just a larger global issue that needs to be resolved.

That isn’t entirely true. Both income tax and the next section, debt, are ways in which America in particular, but any country with large financial and corporate interests in general, keep the general public in states of servitude. This relates closely to the definitional aspect of feudalism above that refers to “a social system in which the nobility held lands from the Crown in exchange for military service”. In this case, we have financial sector billionaires acting as the Crown by granting “lands” to politicians in the form of campaign fundraising in exchange for government legislation that grants them use of “military services” in the form of militarized police forces who are able to assert laws drafted by lobbyists to extract income tax and debts from the majority of Americans as dictated by the IRS.

Of course, society does in fact have good reason to levy taxes. We need roads, bridges, dams, schools, police, and firefighters. Taxes pay for all of these public goods and we have to raise them from somewhere. This section is in no way an argument against taxes or their societal benefit.

One way to raise taxes is corporate taxes. Another is capital gains taxes. And of course, the main option we rely on today is the income tax. The income tax needs to be quite high today in America because of the fact that other taxes, such as the corporate and capital gains taxes, are kept so low. This is the result of massive lobbying interests writing legislation that benefits the financial sector of America and other countries that follow our precedents. This legislation is then enforced by the tax system through the threat of police force if one fails to comply. Anyone refusing to pay income taxes will quickly get a knock on their door.

So rather than extremely wealthy businesses and individuals who make the majority of their money in assets that are taxed under corporate and capital gains tax codes paying for a large share of taxes, the larger majority of working and middle class individuals are forced to pay higher taxes from income. This means they keep less of the wages they earn and therefore must work a larger number of hours to afford their consumption practices (food, clothing, shelter, transportation, etc.). This is basically a modern day “homage” that is described in the definition of feudalism at the start. If one wants to live on the lord’s land, one must pay the homage, which of course they are obliged to live on because they don’t have freedom to move across borders.

Debt

Finally, we come to debt. This works in tandem with income taxes in many ways. It forces people to work longer and harder in order to service the ever growing proportion of debt that makes up average American incomes. David Graeber, in The Democracy Project , asks:

How much of a proportion of the average American family’s income ends up funneled off to the financial services industry? Figures are simply not available. (This in itself tells you something, since figures are available on just about everything else.) Still, one can get a sense. The Federal Reserve’s “financial obligations ratio” reports that the average American household shelled out roughly 18 percent of its income on servicing loans and similar obligations over the course of the last decade— it’s an inadequate figure in many ways (it includes principal payments and real estate taxes, but excludes penalties and fees) but it gives something like a ballpark sense. (Kindle Locations 1220-1225).Coupled with state and federal income taxes, sales taxes, and the excluded penalties and fees Graeber mentions for financing the debt, it is easy to see that the majority of Americans could be paying as much or more than fifty percent of their income to service debt and pay taxes for the “privilege” of living and working on American soil, which they have relatively few options to leave.

Many might argue that modern Americans do not have to take on debt, but that seems to be a rather un-American statement to make. Here are the figures on American debt composition (also from Graeber):

TOTAL DEBT BALANCE AND ITS COMPOSITIONAmericans are constantly sold the idea of home ownership. It is part of the American dream. It also has very large tax incentives, meaning banks highly encourage it, although some economists are beginning to question the validity of this system of incentives and the adverse effects it can have as demonstrated in the Great Recession of 2009. That “American dream”, turns out to be largely a dream for the financial sector, which is then able to extract interest, fees, penalties, and the like for helping you achieve it and pointing out that you’re wasting money by renting because of the tax code they have written, a problem that largely doesn’t exist in Germany where people get by just fine by renting. Auto loans are nearly a necessity if people wish to get back and forth to work in large sprawling suburban metropolises, another problem that doesn’t exist in many countries that make better use of public transportation like Korea and Singapore. Try getting to work in California without a car. Next to housing, cars are typically the largest purchases Americans make and that typically requires financing with the attendant extractive fees and penalties.

Mortgage 72%

Home Equity Revolving 5%

Auto Loan 6%

Credit Card 6%

Student Loan 8%

Other 3% *2011Q3

Total: 11.656 Trillion (Kindle Locations 1250-1256).

Then we come to student debt. Another financial sector dream. Higher education is no longer about the development of our collective humanity or the exploration of the world and what makes life meaningful. Instead, it is the route that must be taken to enter professional work. In order to work in a field that gives one even the slightest chance to break out of the state of serfdom described so far, one must engage in a professional career. This leaves the average American exiting university with over $30,000 in student debt, that cannot be unsaddled even by bankruptcy, at the start of their working life where the median income in America is currently just over $30,000.

This student debt is the ultimate manner in which the financial nobility are able to keep serfs tied to them. One must pay the student loan fees in order to work because of the degree, licensing, and credential requirements of professional fields or risk very serious likelihood of arrest or police threat of violence as they dispossess you of your house, car, and future pay for defaulting.

There is simply little pragmatic alternative for most people in the United States other than getting a student loan, home loan, and car loan in order to work in a profession, live without throwing money away on rent, and commute back and forth in most major cities so that one can turn around and pay those loans and taxes before keeping the little left over for food, clothing, and a bit of leisure and entertainment.

A Path Forward

Americans work the longest hours of any comparable developed nation. The reason should appear obvious by now. We live in a system where the financial sector can lobby government officials for the rules that most benefit them and give them the greatest opportunity to extract income and wealth from the working and middle classes, not unlike southern elites managed to successfully vote for the secession.

They are able to do this in a few major ways: gaining rights to move their own capital around the world freely, while not allowing labor to do so; keeping corporate and capital gains taxes low, thereby shifting the burden of taxation to income taxes; and ensuring a society that requires the majority to take on debt in the form of home ownership, car ownership, and student loans to meet the requirements of professionalization.

None of these rules that harm the majority of US citizens must exist. They largely exist because of the insecurity that breeds within the system itself. If a person is financially insecure and always worried about the harsh consequences from missing even one debt payment or an inability to pay taxes, they are much more likely to act in conservative manners that attempt to create a sense of stability in their life. Psychology is showing again and again that a feeling of stress caused by scarcity turns people inwards, lessens their thinking capacity, and generally makes them more self-interested.

This can help explain why so many working class people vote directly against their own long-run economic interests. They are much more concerned with the predictability of tomorrow by voting for a conservative than the unpredictability of voting for social change that could harm them in the short-run as various social programs and policies are fleshed out.

How does a society overcome this? Unfortunately, there is no simple or quick answer. Francis Fukuyama summarizes this well:

The proper approach to the problem of middle-class decline is not necessarily the present German system or any other specific set of measures. The only real long-term solution would be an educational system that succeeded in pushing the vast majority of citizens into higher levels of education and skills. The ability to help citizens flexibly adjust to the changing conditions of work requires state and private institutions that are similarly flexible. Yet one of the characteristics of modern developed democracies is that they have accumulated many rigidities over time that make institutional adaptation increasingly difficult. In fact, all political systems— past and present— are liable to decay. The fact that a system once was a successful and stable liberal democracy does not mean that it will remain one in perpetuity. (pp. 428-430)What’s worth adding to his thoughts is that the higher level of education he mentions ought to be made free of the oppressive student loans currently being issued in order to avoid serfdom where people become tied to working any job they can find in order to pay the banks back.

While this is by no means a radical or even new proposal, the reasoning should be clear enough. Higher education levels create citizens that can think, act, and work more productively. In thinking more clearly, they are able to find jobs that pay better, ultimately allowing them to overcome their debt, have more discretionary income post-taxes, feel less financially insecure and thereby be able to vote in ways congruent to their own interests.

Clearly, this is a chicken-or-the-egg scenario. What comes first, the voting for better education or the better education needed for the voting? It’s a bit of a “catch 22”. Hopefully, understanding how America closely resembles a feudal state can help in the education process needed to keep government accountable when voting so that legislation is created that benefits the majority and the corrosive institutions that currently exist can slowly be dismantled.

Published on September 04, 2016 05:12

August 26, 2016

The Future of Work

Driverless taxis are here. I asked my 12th grade economics class yesterday what they would do when they couldn't grow up to be taxi drivers. They pretty much all laughed. That’s to be expected in a school where most students are children of very wealthy professionals. None of them imagine a future for themselves where driving a taxi is a legitimate choice.

Driverless taxis are here. I asked my 12th grade economics class yesterday what they would do when they couldn't grow up to be taxi drivers. They pretty much all laughed. That’s to be expected in a school where most students are children of very wealthy professionals. None of them imagine a future for themselves where driving a taxi is a legitimate choice.I then asked them what they would do for work when they grew up and couldn't work as accountants because programs like TurboTax begin to outperform all accountants except the best in the world, thereby replacing 99% of all future accountants. That got fewer laughs.

Then I asked them what they'd do when IBM's supercomputer Watson, which famously beat all human competition at Jeopardy, was successfully reprogrammed to become the world's best doctor (something currently underway). They pretty much all stopped laughing at this point.

One student, after about 10 seconds of reflection, answered very simply, "Give everyone an allowance." Bingo!

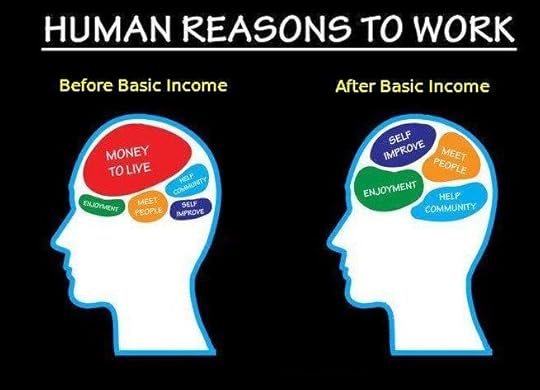

If the industrial revolution replaced muscle power with machine power and the current computing power is replacing brain power and making most service-based knowledge work redundant, the only reasonable answer to come up with is a creation of a universal income. Several nations are already talking and beginning to experiment with that idea. I imagine it will take awhile for America to take it seriously though.

Don't you think there will be new "occupations" created that we cannot comprehend today?

Humans have muscle and brain power to work with. If you strip them of the ability to employ either of those, there are few occupations imaginable. One area, of course, would be in socio-emotional services - something computers are bad at - that don't necessarily require massive levels of muscle or brain power (of the logico-mathematical variety anyway). This would essentially mean teaching people to simply be kind and compassionate towards one another, but it’s hard to see it as an avenue for massive employment. This is essentially the realm that feminism has being attempting to legitimize for the past century, but without any luck in applying it toward paid services.

Innovation is slowing down more generally and it takes more and more expertise, training, and schooling to reach the edge or frontier of complex fields like computer science where most technological breakthroughs happen. This greatly limits the number of people capable of contributing economically in terms of productivity through innovation. This isn't because of inequality either. Even if education were completely free at all levels, there simply aren't that many people capable of having insights at the level needed to create progress in the fields that generate prosperity, such as the STEM subjects.

This is exaggerated by the "winner take all" system that has developed due to mass communication and transportation. The best in the world at accounting can now have a computer programmer create systems like TurboTax and then sell that product to everyone without being limited by geography.

You already see this in fields like music and acting, where celebrity was once confined by geography to the number of people you could perform live in front of. Now, the best musicians and actors in the world can sell their products on iTunes and Amazon to the entire world. The same will be true of just about all service-based knowledge industries given enough time.

Of course, something dramatic could happen that totally upends what we know of history and economics. Right now, we categorize economic output in only four major sectors: agricultural, industrial, service, and creation. Technology is eliminating the first three as secure employment sectors and that leaves us with only the fourth sector centered on creativity, which as pointed out above is essentially unreachable by most people even if they are endowed with unlimited financial backing and equal opportunity. New ideas are just really, really hard to generate.

This is why socio-emotional education based on caring and compassion become even more important. We will almost certainly need "an allowance", what economists call a universal or basic income, as my student put it above for most people. This requires that the majority of the voting public agree to endorse policies that have social welfare and the great mass of people in mind.

Our world is getting richer. Wealth is not the issue here. Technology allows us to produce more goods and services for a greater number of people, giving us more options, prosperity, and a higher quality of life overall. However, we currently believe that the inventors and innovators deserve to capture all of the rewards for themselves. This is just one viewpoint, not the only one.

Another viewpoint is that we can choose to live in a society where we educate all, with the expectation and knowledge that only a small percentage will continue to create wealth through innovation, while at the same time requiring them to share that wealth once it is created. It only requires that we care enough to do it and stop believing that individuals deserve to keep whatever they create all for themselves. After all, they are able to create their innovations only because of the entire system that is in place: state infrastructure, state education, state laws, and state citizenship that leads to state protection.

Instead of seeing people as rightful owners of wealth, we need to view them as stewards of wealth. If they are not stewarding wealth appropriately, meaning using it to make everyone better off, they are not entitled to it. This follows the same vein of thinking as the original idea of a social contract between the populace and government, only now it is extended to a social contract between the populace, the government, and the wealthy.

We can make these changes civilly through education, legislation, and democratic consensus, or we can wait until movements like Occupy Wall Street go from non-violent demonstrations and protests to violent revolutions. The choice is ours.

Published on August 26, 2016 22:49

August 20, 2016

On Learning: Who Not to Listen To

People learn primarily through social interactions of one kind or another. We talk to people, we read, we listen and watch TV, movies, and the news. There really isn’t much variety to how people learn. We take in information in one form or another and that information has to come from somewhere.

People learn primarily through social interactions of one kind or another. We talk to people, we read, we listen and watch TV, movies, and the news. There really isn’t much variety to how people learn. We take in information in one form or another and that information has to come from somewhere.Of course, it is possible that we learn by creating knowledge, either for ourselves without help or for the first time, but that is much more rare. That is essentially what academics do. They create knowledge through their research projects by analyzing, evaluating, and interpreting the data they collect, whether quantitative or qualitative. Assuming you aren’t an academic or some other knowledge creator, you probably learn from others through the methods mentioned above or possibly even direct imitation like a child or athlete does with their parents and coaches, respectively.

This begs the essential question: Who should we get our information from? Who should we listen to, believe, and regard as valid deliverers of knowledge?

Technical Knowledge

The quality of technical knowledge comes in a huge variety of forms. Just like the quality of food we take in daily impacts our physical health and robustness, the quality of information and knowledge we absorb day to day impacts our intellectual health and robustness.

Dilettantes and Charlatans

One of the most important areas of knowledge in today’s world is technical knowledge. This is what we typically rely on experts to generate and disseminate and is considered the “bottleneck of all expertise”. Yet we often don’t get our knowledge from experts.

One example of this is demonstrated by using Amazon to search through books on various topics, something I enjoy doing on a regular basis to try and notice what books have the most reviews, which authors have the highest sales ranks, and what books are topping the bestseller lists in different categories.

For instance, Dan Harris, correspondent for ABC News and the co-anchor for the weekend edition of Good Morning America, has one of the most reviewed and top ranked books in the category of “happiness” on all of Amazon. It has over 2,200 reviews (an astounding number for Amazon) and as of this moment, ranks #9 on the bestseller list in this category.

While happiness might be considered a field that is accessible to anyone with an opinion and open for advice from all parties, there is in fact an entire field of empirical, and therefore non-anecdotal, research devoted to the topic. You would think that anybody serious about learning about happiness would take the time to investigate the preeminent researchers in that field (positive psychology) and begin their reading and learning with them. This is not to say that non-researchers have nothing valuable to say, just that the validity is immediately questionable until proven otherwise.

In continuing a search within the category of happiness by “most reviews” on Amazon, the very next page has a book titled The Happiness Advantage: The Seven Principles of Positive Psychology The Fuel Success and Performance at Work and is written by Shawn Anchor. This would appear to be a better start. After all, the title directly references the field of positive psychology that I just mentioned. His biography also includes working and lecturing at Harvard. Yet, if we dig a little deeper, we can find out that he worked as a dormitory Freshman Proctor at Harvard after receiving a master’s degree in divinity and helped lecture as a teaching assistant for a professor that taught a course on happiness. He is hardly the academic expert on the subject that first glance might convince us that he is.

Mystics and Pop Expertise

Continuing our search, we would stumble upon the The Art of Happiness a few pages deeper into the search results of Amazon. This has about 100 reviews less than Anchor’s book and about 1,500 reviews less than Harris’ book. It is co-written by the Dalai Lama and Howard Cutler, the spiritual and former state leader of the Tibetan people and a psychiatrist respectively.

This is a much better starting place. The Dalai Lama has spent, quite literally, his entire life studying happiness through subjective introspection, argument, and experiential reflection. Cutler has a medical degree and has practiced for years as a psychiatrist, working with actual people who seek his help in becoming happier.

If you don’t like the idea of getting advice from a professed spiritual leader (always a murky area that contains a lot of nonsense and supernatural mysticism), but do like the idea of an MD or PhD who has spent their entire life rigorously studying the subject then the search would have to continue even further.

To get away from dilettantes like Harris, charlatans like Anchor, or spiritual mysticism like the Dalai Lama (someone I do greatly admire), you have to go all the way to the seventh page of search results on Amazon before you come across a book titled, coincidentally enough, Stumbling on Happiness by Daniel Gilbert. This book has a little over 500 reviews on Amazon as of this writing and so would not necessarily show up as the first search result. However, it is written by a social psychologist who received his PhD from Princeton University and now works at Harvard where he does in fact research human happiness and has done so for the length of his career.

Peer-reviewed Expertise

While popular psychology books like Gilbert’s are great, they are still written with sales in mind and try to package material in ways that are palatable to their general public audiences. This can be fine, but it can also put focus on topics that might not be as important as the field of research in general suppose them to be. An even stronger start would be to find a textbook on the subject, even if it is an undergraduate introductory text. This will contain the broadest survey of agreed upon facts, important researchers, and controversies within the research community of the given field and not be filtered through just one researcher’s and his or her publicist’s and publisher’s demands.

These types of books usually won’t even show up in the search results because they have such few reviews on platforms like Amazon. An example textbook, A Primer in Positive Psychology , which is very readable, has only 43 reviews - a far cry from the 2,200 for Harris. In fact, you wouldn’t find it just by searching through the most reviewed books on happiness because it isn’t even labeled under that category. It is labeled in the categories of “social psychology”, “reference”, and “education”.

This is where understanding how key word searches can fail you is important. Sometimes it is worth figuring out the field of research that studies the topic you’re interested in - in this case positive psychology is the field of research that studies the topic of happiness. Searching for just they key word of happiness may not get you to the best source of information as described immediately above.

So generally speaking, people interested in a field of technical knowledge should begin with either a popular book like Gilbert’s or an introductory textbook. Both of these have information that have been evaluated against the entire field of research by professionals who spend their entire careers immersed in the subject. This is a much stronger base than beginning with a book written by someone like Harris, who simply did some investigative journalism and regurgitated it into a book without having a background in the topic himself. It’s his media platform and minor celebrity that earned his reviews, not his credentials to talk about the subject.

Of course, no one is saying that you only have to read one book on a subject and it is always good practice to read multiple sources. However, if you were to read just one book, the textbook is recommended over the journalist every single time.

Procedural Knowledge

Another large area of knowledge is that of procedural knowledge. This is knowledge that requires practice and skill development. Things like learning to play a sport or instrument are good examples. This is the type of knowledge typically studied by the field of expertise under the topic of deliberate practice. Here the advice is much simpler and straightforward.

Find someone with the hat trick.

What’s the hat trick? The hat trick is when a person has three different and specific types of credentials: technical knowledge, personal experience, and coaching experience.

Technical experience. I’ll use examples again, this time from my own life. I recently found and paid an online coach, John Meadows, for help in meeting my physical health goals at the gym. The coach I chose has extensive technical knowledge, having received a degree in exercise science, multiple certifications in personal strength and conditioning training, and has worked with multiple PhD researchers on nutrition. He knows more about anatomy, physiology, endocrinology, and diet than the vast majority of humans.Personal experience. While technical knowledge is something any good coach should have, it is actually the least important when pursuing procedural expertise in most cases. Technical knowledge alone won’t get results. It has to be paired with knowledge of how to apply it. This is more evident in this category and the next. Taking my current coach as an example again, he has 25 years of personal experience as a strength trainee. He has squatted, bench pressed, and deadlifted more than I ever will. Furthermore, he was also able to win his professional card in the top bodybuilding federation in the world after attempting to do so for 20 years. He has personally worked very hard, experimented, and changed strategies to figure out what worked and didn’t while working towards his goals.Coaching experience. This last category is even more important than the previous two. It is great if someone has technical knowledge and was able to apply it to gain success in their own endeavors. However, that is not actually what you are looking for when selecting a teacher, trainer, coach, or mentor. You are looking for them to be able to apply what they know and have done to gain success for you. That is why the ultimate qualification for learning from someone else in the area of procedural knowledge is a proven track record of success in teaching other people the knowledge and skills you are looking for yourself. Again, my coach selection matches this criteria. He has successfully trained multiple professional and amateur enthusiast trainees to reach their selected goals. The latter is important. It is often easier to get results with professionals than amateurs. Amateurs, such as myself, typically don’t have all the extra benefits that professionals have at their disposal and getting results with them is often even more difficult.

Conclusion

If one is going to spend the time to learn something, it is worth getting the best information possible. This often takes very little extra effort on one’s part. The above rules for doing so can help enormously.

For technical knowledge, find technical experts. Read their books. Watch their YouTube lectures. Take their classes. Enroll in their programs.

For procedural knowledge, find somebody with the hat trick. That is, find someone who has a degree of technical knowledge in the procedural knowledge you wish to attain, has personal experience with the procedural knowledge themselves, and has already gained success for others by applying their technical knowledge and personal experience.

The most important aspect in acquiring either of the two types of knowledge outlined in this article is knowing what you are after. Always take the time necessary to focus your goal(s) so that you know what you are really aiming for. If you don’t have a clear target, you’ll never be successful, regardless of the qualifications attached to the knowledge you gain.

Published on August 20, 2016 20:29

August 13, 2016

Democracy's Flaw: Media. Simplicity. Extremism.

Democracy is a difficult form of government to get right. It requires a delicate balancing act of education, non-discrimination, and non-repression. These components make it possible that representatives, policies, and legislation are selected that benefit as many people as possible without tyrannizing over minority groups and individual rights. This requires a nation’s education system to be robust so that individuals learn how to think critically about issues and for the media to provide adequate information on facts for the public to deliberate on.

Democracy is a difficult form of government to get right. It requires a delicate balancing act of education, non-discrimination, and non-repression. These components make it possible that representatives, policies, and legislation are selected that benefit as many people as possible without tyrannizing over minority groups and individual rights. This requires a nation’s education system to be robust so that individuals learn how to think critically about issues and for the media to provide adequate information on facts for the public to deliberate on.This deliberation can become very messy, complex, and nuanced. It’s hard not to in any society that has cultural diversity and pluralistic values. Beliefs will often conflict and create situations in which at least one party will potentially lose. Even when that is true, the public should hope to elect representatives that understand this messiness and make decisions with the greatest benefit in mind.

Democratic Deliberation

The main issue seems to be that democracy requires deliberation among the electorate on how best to organize society. Societal organization can’t hope to land on the best system on the first try. It requires constant change and experimentation. Even if democracy did select the best possible organization for society on the first try, it would need constant updating and change due to fact that new people and needs will enter the system over time and change the balance of what is best.

In order to choose the best organization for this moment in time, the voting public needs to have access to information. If the public doesn’t have access to valid, nuanced information, they can’t deliberate from facts.

Deliberation in a democracy ought to be based on reason, argument, and evidence. If the public is voting on a candidate that is addressing a complex issue like immigration, they ought to be aware of exactly how immigration affects the country in both the short and long term. This requires understanding complex ideas in economics and politics and cannot be boiled down to a simple headline such as, “Immigrants Steal Jobs” or “Everyone Wins with Free Trade”.

The Media

News outlets are our primary source for the information we need in making choices. These news outlets can be either publicly or privately owned and both have negatives. Public ownership of news outlets has the potential to be abused by currently sitting politicians who can manipulate information to their advantage. Private ownership, as the majority of the media system is structured now, obligates companies to maximize profit if they have shareholders and generally compete with firms to remain open and be able to cover their costs.

This latter point often requires getting as many eyeballs on the news outlet’s channel or paper as possible. In order to do this, media sources act much like other companies in that they turn to catchy headlines and soundbites that drive ratings, in essence giving their customers what they want. Many people have written about the “banality of good”, but I like Matthieu Ricard’s short summary from Altruism best when he writes, “everyday good does not make much commotion and people rarely pay attention to it; it doesn’t make the headlines in the media like an arson, a horrible crime, or the sexual habits of a politician” (p. 94).

Complexity versus Simplicity

One way of interpreting the media’s insistent negative press is to view it as a product of “cause and effect” thinking. Most of modern society has been built on the scientific method in some capacity. We use it everyday, even if we aren’t always aware of it, to make our lives better. The roads we drive on, the buildings we inhabit, the food we eat, and just about everything else we can point to is a product of scientists’ and engineers’ thinking very hard about how to improve our lives by searching for cause and effect relationships and isolating variables.

However, this reliance on cause and effect thinking that arises from our societal love of the scientific method creates a problem when situations are complex. We intuitively look for a single cause and try to point to it as the solution of whatever problem we might be facing. This has the typical result of destroying nuance and multidimensionality in problem solving. This destruction of nuance and complexity when it is needed, such as in the political and economic arena of democracy, makes differentiation among candidates difficult without resorting to moving away from the center to more extreme positions.

Partisan Extremism

Now we come to the real problem. Democracy requires information. That information is distributed by news outlets that must maintain ratings to make a profit. This forces the media to focus on simple and direct cause and effect thinking that is easily captured in soundbites and short phrases, or even single words. This simplification of what is needed for positive change by eliminating nuance and complexity promotes extreme positions taken by candidates for a very simple reason - the need to differentiate to win votes.

Think about it this way. If you know that whatever you say will be captured in a headline and that many people will not read the entire story or place it within a larger context, you cannot argue over details and minutia that separate you from another “center” candidate. You have to aim at a headline that will grab attention while avoiding complexity. This necessitates a move outward to further positions on the left or right or you will sound just like every other candidate when broken into center-positioned soundbites by the news.

We see this today on both sides of the political spectrum in America. A good example from the Democratic platform was Obama’s entire 2008 message of “Hope” and “Change”. You literally can’t get anymore simple than single word platforms, but in reality these two words are meaningless outside of complex contexts and it would be genuinely idiotic to endorse him and his party on the basis of these two words.

We ought to immediately ask ourselves, “What kind of change? What specific things do you plan to change, and how?” This obviously involves much more digging into details and specifics with possibly conflicting solutions for multiple problems. But until we know these things, we can’t assume any change is good change. Plenty of change can be bad.

Which takes us to his second message of “Hope”, which is essentially the opposite of what we should be looking for in a candidate. The electorate should not be closing their eyes, crossing their fingers, and hoping for a better tomorrow. They should be digging into the messiness that is political economy with eyes wide open and experimenting with solutions continuously to see what does and does not work.

This requires no hope at all. Just a willingness to do the work. And a willingness to suffer through some failures of experimentation to arrive at a better future.

Getting to the Point

The point is positive improvement for the greatest number. Democracy generally accomplishes this better than other systems we have experimented with as humans trying to organize society, but that doesn’t mean it is perfect.

The system itself pushes potential representatives to extreme positions in their attempt to differentiate and win elections. Occasionally, an extreme position may be just what is called for, especially on issues that entail more socially inclusive policies around human and civil rights for disenfranchised, discriminated against, or oppressed members of a society.

But more often than not, the changes necessary to make daily life better for all require a holistic image of the entire system and how it will be impacted by shifts of its different components. This type of “routine” change doesn’t require flashy language and partisan extremism. It only requires engaged, caring, and knowledgeable representatives who have everyone’s best interests at heart. In cases like these, sometimes (most often) the best candidate will be the boring one who has done the work, not the exciting one who yells the loudest.

Published on August 13, 2016 18:47

August 8, 2016

The Exercise Algorithm

I’ve always exercised for only a couple of reasons: to feel able enough to experience more of life and to avoid preventable diseases and injuries as I age. The latter reason is the primary impetus for me even when I feel unmotivated, but the former is a nice perk, almost a bonus as it were, and what has given me some of my best memories and feelings of accomplishments.

I’ve always exercised for only a couple of reasons: to feel able enough to experience more of life and to avoid preventable diseases and injuries as I age. The latter reason is the primary impetus for me even when I feel unmotivated, but the former is a nice perk, almost a bonus as it were, and what has given me some of my best memories and feelings of accomplishments. Examples of the experiences I’ve had because of physical health include climbing Mount Whitney and Mount Baldy in California with some of my closest friends, squatting 402 pounds, deadlifting 500 pounds, running two half marathons, completing a triathlon, doing 20 pull ups at one time, spearfishing in Malibu, and otherwise enjoying outdoor leisure activities such as camping, hiking, bodysurfing, and various board sports. These memories and accomplishments due to physical health rival every other good memory I have outside this realm of physicality, including earning a Master’s degree, self-publishing Kindle and Audible books on Amazon, getting married, and helping students learn about and fundraise for valuable organizations.

However, as I said above, it is really the prevention of diseases and injury that motivates me to maintain a minimum of physical health. Anyone who doesn’t know me that well won’t know this, but I’ve grown up with a father that has a genetic variation of emphysema. It is a disease that, as he has described it, “takes one new thing away from you each day, week, or year”. It’s progressive and miserable.

He used to be able to lift heavy weights, run trails through the California hills and mountains, and play tennis vigorously as a serious hobby. Now, he is lucky to finish 18 holes of golf while using a cart and oxygen the entire time. Bending over to remove weeds in the garden can make him lightheaded and dizzy. Even showering, dressing, and putting on shoes and socks (bending over again) can be exhausting.

With his ever looming physical presence in my house, I’ve been interested in warding off major surgeries and illnesses via prevention since I was a teenager.

The 10 Leading Causes of Death Worldwide

According to the World Health Organization approximately 56 million people die each year and the leading causes are as follows:

Ischaemic heart disease, stroke, lower respiratory infections and chronic obstructive lung disease have remained the top major killers during the past decade.Leading Causes of Death in the USA

HIV deaths decreased slightly from 1.7 million (3.2%) deaths in 2000 to 1.5 million (2.7%) deaths in 2012. Diarrhoea is no longer among the 5 leading causes of death, but is still among the top 10, killing 1.5 million people in 2012.

Chronic diseases cause increasing numbers of deaths worldwide. Lung cancers (along with trachea and bronchus cancers) caused 1.6 million (2.9%) deaths in 2012, up from 1.2 million (2.2%) deaths in 2000. Similarly, diabetes caused 1.5 million (2.7%) deaths in 2012, up from 1.0 million (2.0%) deaths in 2000.

According to the Center for Disease Control, the leading causes of death of the approximately 2.5 million annual deaths in America are:

Heart disease: 614,348Cancer: 591,699Chronic lower respiratory diseases: 147,101Accidents (unintentional injuries): 136,053Stroke (cerebrovascular diseases): 133,103Alzheimer's disease: 93,541Diabetes: 76,488Influenza and pneumonia: 55,227Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, and nephrosis: 48,146Intentional self-harm (suicide): 42,773

To be even more specific, according to Harvard’s School of Public Health, approximately 2 million (of the 2.5 million total) deaths are preventable each year and are due to “dietary, lifestyle and metabolic risk factors”. The number of deaths annually due to these specifically preventable risk factors are:

Smoking: 467,000High blood pressure: 395,000Overweight-obesity: 216,000Inadequate physical activity and inactivity: 191,000High blood sugar: 190,000High LDL cholesterol: 113,000High dietary salt: 102,000Low dietary omega-3 fatty acids (seafood): 84,000High dietary trans fatty acids: 82,000Alcohol use: 64,000 (alcohol use averted a balance of 26,000 deaths from heart disease, stroke and diabetes, because moderate drinking reduces risk of these diseases. But these deaths were outweighed by 90,000 alcohol-related deaths from traffic and other injuries, violence, cancers and a range of other diseases).Low intake of fruits and vegetables: 58,000Low dietary poly-unsaturated fatty acids: 15,000

And to be even more specific still, according to the CDC again:

Falls are the leading cause of injury-related morbidity and mortality among older adults, with more than one in three older adults falling each year, resulting in direct medical costs of nearly $30 billion. Some of the major consequences of falls among older adults are hip fractures, brain injuries, decline in functional abilities, and reductions in social and physical activities. Although the burden of falls among older adults is well-documented, research suggests that falls and fall injuries are also common among middle-aged adults. One risk factor for falling is poor neuromuscular function (i.e., gait speed and balance), which is common among persons with arthritis. In the United States, the prevalence of arthritis is highest among middle-aged adults (aged 45–64 years) (30.2%) and older adults (aged ≥65 years) (49.7%), and these populations account for 52% of U.S. adults. Moreover, arthritis is the most common cause of disability. (p. 379)What this all points to, if you live in the United States in particular, is a need to address long-run physical issues through prevention. Avoiding smoking, drinking, trans fatty acids, and high dietary salt and sugar aren’t that difficult. Neither are including poly-unsaturated fats, fruits, vegetables, omega-3 fatty acids, and exercise.

Even though diet is clearly very important from reading the above, I find most people understand and know this. Rather, like flossing and other simple things involving willpower, they simply choose not to eat and drink well because of a host of reasons, sometimes individually based, but often social as well.

What I find most people don’t do is make clearer connections to their exercise choices and the long-run prevention strategies that should become obvious as one looks over the data above. Exercise has a clear and robustly supported impact on some of the largest causes of death in the United States.

Causes of death such as heart disease, respiratory disease, Alzheimer’s disease, intentional self-harm, high blood pressure, overweight-obesity, and the number one cause of death in old age, “falls”, are all directly connected to and can be decreased by our choices of exercise. So let’s examine what I believe to be the best overall approach to longevity given what the data above tell us.

The Algorithm EfL = f(M, TS, ES) Exercise for longevity is a function of our mobility, tissue strength, and energy systems.

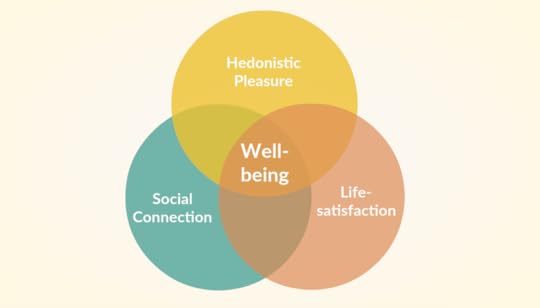

Of course, overall health and well-being will include more than exercise. As mentioned above, diet will be one large aspect. Sleep would be another. Stress yet a fourth. And take a look at my algorithm for subjective well-being for variables regarding your mind, which also have a strong impact on your physical health. PH = f(D, S, E, St) Physical health is a function of diet, sleep, exercise, and overall stress levels.

I won’t go into all the variables in the PH equation directly above, but will spend some time fleshing out the first equation on exercise for longevity.

Mobility

This dimension seems to be the most confusing to people. As physical therapist Charlie Weingroff puts it:

Being fully mobile simply means the ability of a joint system to move through a definable range.This definition is great because it puts mobility into perspective. Mobility’s job is to let you do the tasks you wish to do. Nothing more. Being able to do a full splits may demonstrate extreme mobility of your hips, but if it doesn’t let you perform any other tasks that you deem important, then it is probably a bit silly to spend an inordinate amount of time gaining that ability.

That desired range must be defined first because if you are looking for a quarter squat as your indicator of success (not sure why you would), that is the mobility you need to have “good mobility.” Good or lousy mobility is always related to the movement at hand. It should be a very relative term by definition.

Gray Cook, another physical therapist, states it nicely when he urges us to “manage our minimums”. Our lack of mobility often gets us in trouble when it is asymmetric more so than when it is somewhat limited. What all this means is that you don’t have to take up yoga to become more “flexible”, i.e. mobile. You don’t win points for being more mobile than someone else unless that person can’t live a normal, independent life because of their poor ranges of movement.

In general, once you decide that you do need to improve your mobility, physical therapy work will be the most effective practice, much more so than simply stretching. “You need a trigger point technique, a soft tissue technique, and a joint technique.” A good place to start for self maintenance is on physical therapist Kelly Starrett’s Mobility WOD. If you really do have mobility issues, this will get you much further than yoga or static stretching in much less time and energy.

But again, mobility is relative to what you want to do with yourself. With longevity in mind, you are mostly worried about being able to get up and down off the floor and up and down off the toilet, along with reaching upward or downward to grab or pick up things. Those are really the biggest demands on most people’s mobility as they age. Anything past that will be mostly individual wants and needs.

What improved mobility won’t do is prevent any of the major causes of death described above except perhaps “falls”, but this is more often related to muscle weakness and atrophy and is better addressed in the next dimension of exercise - tissue strength.

Tissue Strength

Human tissues come in two forms: soft and hard. Soft is easier to describe as saying it is everything that isn’t hard tissue, i.e. bone and tooth. That means that soft tissue comprises tendons, ligaments, muscles, fascia, nerves, blood vessels, skin, and a few others.

In strengthening both hard and soft tissue, one can alleviate the chances of several of the risks above, including accidents, diabetes, high blood pressure, overweight-obesity, and inadequate physical activity. The best way to strengthen your bodily tissues is to exert stress on them through external weight.

This means weight training, strength training, bodybuilding, Crossfit, or whatever other form of training you wish that involves weights of moderate load (60-85% of maximum), for moderate repetitions (5-20), and moderate sets (3-10). This is because weight training is the most effective way to increase bone density, tendon/ligament strength, muscle size, and regulate blood pressure, hormones, and hypertension. Basically, “Barbell training is big medicine.”

The three best understood methods for maintaining muscle size and strength according to Brad Schoenfeld, PhD in exercise science, are through mechanical tension, muscle damage, and metabolic stress.

Mechanical tension is created on a muscle, bone, tendon, or ligament any time we use a relatively heavy load. This is generally understood to be 60-100% of our maximal effort. Muscle damage is best elicited through exercises that have not been done recently, by providing a greater than normal stretch or lengthening of a muscle, and the use of heavy or slow eccentrics (lowering of a weight). Lastly, metabolic stress is the buildup of metabolites in a muscle and is best described as the “burn” we feel in our muscles from repeated contractions with little rest. Basically anything that Arnold Schwarzenegger would have described as a “pump” back in the 70’s is likely to induce metabolic stress in a muscle.

A host of interrelated reasons explain why increased tissue strength and size are so effective at combating the above risk factors. Accidents are far less likely when we have strong bones and muscles that we have learned to coordinate through the coordination of our own bodies and external weights. Diabetes, high blood pressure, and obesity have nearly zero chance of occurring with frequent weight training because more muscle means a higher rate of metabolism, as our tissues are where metabolism occurs. The repeated spiking of blood pressure during weight training actually works as a stressor that keeps our blood pressure lower when not exercising, just like raising our heart rate during running keeps our heart rate lower when not running. This type of exercise also has a large and positive impact on our hormones, causing several to be released and regulated in a healthy manner.

Jonathon Sullivan, MD and PhD in physiology, summarizes all of these effects from strength training on longevity perfectly:

And before you ask: at present there is absolutely no solid evidence that strength training—or any other exercise or dietary program—will substantially prolong our life spans. But the preponderance of the scientific evidence, flawed as it is, strongly indicates that we can change the trajectory of decline. We can recover functional years that would otherwise have been lost. There is much talk in the aging studies community about “compression of morbidity,” a shortening of the dysfunctional phase of the death process. Instead of slowly getting weaker and sicker and circling the drain in a protracted, painful descent that can take hellish years or even decades, we can squeeze our dying into a tiny sliver of our life cycle. Instead of slowly dwindling into an atrophic puddle of sick fat, our death can be like a failed last rep at the end of a final set of heavy squats. We can remain strong and vital well into our last years, before succumbing rapidly to whatever kills us. Strong to the end.Energy Systems

That, my friends, is Big Medicine. (p. 6)

Finally we come to energy systems training, which can help prevent the major causes of death, including heart disease, respiratory disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and suicide due to depression.

We actually have three overlapping energy systems. These include the phosphagen system, anaerobic system, and aerobic system. The first two are used for short-term, high-intensity outputs like jumping, sprinting, weight lifting, etc. You can typically sustain the phosphagen system for up to 10 seconds and the anaerobic system for a couple of minutes (think 800 meter run) before you start to feel your lungs and muscles scream and burn. Both of these are easily addressed with whatever weight lifting you do for strengthening your tissues, but interval training can also do the trick.

The third system, aerobic energy, uses oxygen and is what most people think of when they think of “cardio”. Anyone swimming, biking, jogging, or otherwise covering a lot of ground over a long time will be using this energy system. However, people today seem to have gone to extremes with ultramarathons, Ironman triathlons, and century bike rides.

Andrew Hallam, summarizes the research well when it comes to cardio:

Earlier this year, five researchers published a study in the Journal Of The American College of Cardiology. They found that, on average, joggers live about 6 years longer than couch potatoes. But those who run too far, too fast, or too frequently die earlier. They live about as long as a typical T.V. loafer.Putting It All Together

The best survival rate came from those who ran 2 to 3 times per week, at an easy pace. Those who ran more than 2.5 hours per week died earlier. Those who ran faster than 7 miles per hour met the same fate.

Cardiologists Justin E. Trivax and Peter A. McCullough published Phidippides cardiomyopathy: a review and case illustration. They say endurance sports can hurt the heart. “It has been shown that approximately one-third of marathon runners experience dilation of the right atrium and ventricle, have elevations of cardiac troponin and natriuretic peptides, and in a smaller fraction later develop small patches of cardiac fibrosis that are the likely substrate for ventricular tachyarrhythmias and sudden death.”

Researchers from Rome’s Institute of Sports Medicine and Science published equally surprising findings in the European Journal of Preventative Cardiology. They studied 2,354 Olympic-level athletes between 2002 and 2014 to “assess the efficacy of the Olympic pre-participation screening protocol.” Tests determined how the athletes’ hearts performed under stress and whether there were any cardiovascular issues.

They concluded that, “Olympic athletes, regardless of their superior physical performance and astonishing achievements, showed an unexpected large prevalence of CV [cardiovascular] abnormalities, including life-threatening conditions.”

Cardiologist James O’Keefe, however, does give us hope. In his TED talk, he referenced a study on mice. One group ran hard on a treadmill over an 8 week period. Their resulting heart abnormalities were similar to those of humans who run too far, too frequently or too fast. But when researchers took the mice off their tough regimes, their heart muscles recovered.

While all of this seems rather complicated, it’s actually quite simple. To do our most to prevent long-term health problems due to illness, injury, and death when it comes to exercise, we essentially want to physically train much like a bodybuilder. This means:

Weights three to five times a week,Easy, low intensity cardio two to four times a week,And physical therapy style mobility work as necessary.

This will keep our tissues strong and healthy, our cardiovascular system in optimal condition, and our joints and movement patterns capable of the ranges of movement we need so we don’t succumb to dying by “fall” once we get over the age of 65. If we are living up to and beyond our 70’s and 80’s, we must plan accordingly.

I’ve seen my dad suffer from pretty much all of the major risks above, including heart disease, lung disease, overweight-obesity, accidents, depression, and those are just the ones I know about. I do not wish to suffer the same as I age, especially as I don’t have any genetic reason why I would.

None of this needs take any longer than traditional hour long classes at a local gym or the 10K you run 4 times a week either. Thirty minutes of weights, followed by 20-30 minutes of cardio, and zero to 10 minutes of mobility work will still only take an hour out of your day and can be done just two to four times a week like most recreational exercisers do anyway.

Conclusion

While the algorithm best suited for ensuring longevity from exercise is rather short and straight forward, it doesn’t take into account a host of other factors, some of which were touched upon earlier regarding diet, sleep, stress, smoking, drinking, and risky sex practices.

In addition, it’s equally important to point out that on a day to day basis, driving is one of the most dangerous activities that we participate in and anything that you can do to reduce the miles driven on roads, the better. It’s also worth noting that accidents are the number one cause of death in the 25-44 age group and that suicide, homicide, and liver disease are numbers four, five and six.

This implies that living in a country or city like Singapore, where a person typically drives less because of efficient public transport, has access to good psychological health services, is very unlikely to be a victim of homicide, and is forced to pay expensive cigarette and alcohol taxes, can actually be of great service in making it through a person’s midlife and into their later years unscathed by youth.

I also realize that the most popular forms of exercise are not actually included in this algorithm. Yoga, running, biking, and swimming (ultra) long distances, Zumba, Pilates and the like really have almost no use outside of the psychological and social benefits they might provide you, which I think is what most people are actually searching for when they undertake these activities. They are similar in nature to the glass of wine people drink after work “for the health benefits”. The truth is they just make you feel better.

The goal of this algorithm regarding exercise for longevity is ultimately to fill gaps in thinking for people. Many view running as a complete exercise program or something like yoga and Pilates as “all you need” for complete physical health. This is objectively not true. While both of these types of exercise give some narrowly received benefits, they completely miss the tissue strength enhancements that will be your biggest ally in in keeping independence and functioning in old age and do little to ward of the metabolic diseases of modernity.

It isn’t that you can’t do the things you love and enjoy. It’s that by going about designing and thinking about exercise on the basis of what is objectively needed to prevent our leading causes of death and injury, we can also feel subjectively better. There are very few things as subjectively rewarding as being physically fit in all three of the dimensions described above: mobility, tissue strength, and energy systems.

At the end of the day, there is no problem with doing things because they make you feel better psychologically, but it is important to separate facts from the delusions we often tell ourselves and realize that empirically and objectively arrived at choices for exercise can also be enjoyed subjectively while keeping you healthier in the long run. Even if it means learning and doing new things you initially find uncomfortable or possibly even painful, the payoff for both you and society is more than worth it.

Published on August 08, 2016 03:53

July 31, 2016

From Boredom to Joy and Everything in Between

If we accept that most of life is suffering and we are goal seeking entities, then inquiries naturally follow about what sorts of goals and activities let us avoid boredom and suffering while experiencing joy. A recent conversation and extensive bout of reading has driven me to explore these questions in more deeply than I have previously. Below is my attempt to develop answers in which I will find recourse to extensive quotes from my most recent reading.

If we accept that most of life is suffering and we are goal seeking entities, then inquiries naturally follow about what sorts of goals and activities let us avoid boredom and suffering while experiencing joy. A recent conversation and extensive bout of reading has driven me to explore these questions in more deeply than I have previously. Below is my attempt to develop answers in which I will find recourse to extensive quotes from my most recent reading.Boredom

In The Reasons of Love , Harry G. Frankfurt describes boredom and its connection to goals and joy in the most beautiful manner I’ve seen to date. He paints boredom as not just an uncomfortable state of being, but as essentially an attack on our vitality and the death of our self:

It is an interesting question why a life in which activity is locally purposeful but nonetheless fundamentally aimless— having an immediate goal but no final end— should be considered undesirable. What would necessarily be so terrible about a life that is empty of meaning in this sense? The answer is, I think, that without final ends we would find nothing truly important either as an end or as a means. The importance to us of everything would depend upon the importance to us of something else. We would not really care about anything unequivocally and without conditions.Naturally, if we understand accept Frankfurt’s description of boredom, we would want to figure out a way to prevent it and at the same time find a method for selecting a non-local goal (i.e. a final end). Thankfully, he doesn’t make us wait long, as he immediately turns to answering this question:

Insofar as this became clear to us, we would recognize our volitional tendencies and dispositions as pervasively inconclusive. It would then become impossible for us to involve ourselves conscientiously and responsibly in managing the course of our intentions and decisions. We would have no settled interest in designing or in sustaining any particular continuity in the configurations of our will. A major aspect of our reflective connection to ourselves, in which our distinctive character as human beings lies, would thus be severed. Our lives would be passive, fragmented, and thereby drastically impaired. Even if we might perhaps continue to maintain some meager vestige of active self-awareness, we would be dreadfully bored.

Boredom is a serious matter. It is not a condition that we seek to avoid just because we do not find it enjoyable. In fact, the avoidance of boredom is a profound and compelling human need. Our aversion to being bored has considerably greater significance than a mere reluctance to experience a state of consciousness that is more or less unpleasant. The aversion arises out of our sensitivity to a far more portentous threat.

The essence of boredom is that we have no interest in what is going on. We do not care about any of it; none of it is important to us. As a natural consequence of this, our motivation to stay focused weakens; and we undergo a corresponding attenuation of psychic vitality. In its most characteristic and familiar manifestations, being bored involves a radical reduction in the sharpness and steadiness of attention. The level of our mental energy and activity diminishes. Our responsiveness to ordinary stimuli flattens out and shrinks. Within the scope of our awareness, differences are not noticed and distinctions are not made. Thus our conscious field becomes more and more homogeneous. As the boredom expands and becomes increasingly dominant, it entails a progressive diminution of significant differentiation within consciousness.

At the limit, when the field of consciousness has become totally undifferentiated, there is an end to all psychic movement or change. The complete homogenization of consciousness is tantamount to a cessation of conscious experience entirely. In other words, when we are bored we tend to fall asleep.

Any substantial increase in the extent to which we are bored threatens the very continuation of conscious mental life. What our preference for avoiding boredom manifests is therefore not merely a casual resistance to more or less innocuous discomfort. It expresses a quite primitive urge for psychic survival. I think it is appropriate to construe this urge as a variant of the universal and elemental instinct for self-preservation. It is related to what we commonly think of as “self-preservation,” however, only in an unfamiliarly literal sense— that is, in the sense of sustaining not the life of the organism but the persistence and vitality of the self. (p. 53-55)

There must be certain things that we value and that we pursue for their own sakes. Now it is easy enough to understand how something comes to possess instrumental value. That is just a matter of its being causally efficacious in contributing to the fulfillment of a certain goal. But how is it that things may come to have for us a terminal value that is independent of their usefulness for pursuing further goals? In what acceptable way can our need for final ends be met?This too makes a lot of sense, but we should investigate what Frankfurt means by love and the use he applies to it here. He does this most brilliantly in a separate work discussing the value of truth.

It is love, I believe, that meets this need. It is in coming to love certain things— however this may be caused— that we become bound to final ends by more than an adventitious impulse or a deliberate willful choice. Love is the originating source of terminal value. If we loved nothing, then nothing would possess for us any definitive and inherent worth. There would be nothing that we found ourselves in any way constrained to accept as a final end. By its very nature, loving entails both that we regard its objects as valuable in themselves and that we have no choice but to adopt those objects as our final ends. Insofar as love is the creator both of inherent or terminal value and of importance, then, it is the ultimate ground of practical rationality. (p. 55)

Love and Joy

In On Truth , which looks at the nature of truth and why we as humans should value it, Frankfurt finds it useful to build on the work of Spinoza, one of the first humanist philosophers in spirit:

Spinoza explained the nature of love as follows: “Love is nothing but Joy with the accompanying idea of an external cause” (Ethics, part III, proposition 13, scholium). As for the meaning of “joy,” he stipulated that it is “what follows that passion by which the…[individual] passes to a greater perfection” (Ethics, part III, proposition 11, scholium).The above account is perhaps the single best explanation of joy and love that I have come across. I have added emphasis to three points above because the first two resonate deeply with me, but the third point on “necessarily striving to have present and preserve” does not. In fact, this having orientation to life in which we feel possessive towards the things that bring us joy is described in great depth by Erich Fromm in his landmark work, To Have or To Be , as one of the prominent causes of suffering in our world due to the fear and insecurity that it engenders.

I suppose that many readers will find these rather opaque dicta quite uninviting. They do truly seem forbiddingly obscure. Even apart from this barrier to making productive use of Spinoza’s thoughts, moreover, one might not unreasonably question whether he was qualified, in the first place, to speak with any particular authority about love. After all, he had no children, he never married, and it seems that he never even had a steady girlfriend.

Of course, these details concerning his personal life have no plausible relevance except to questions about his authority with respect to romantic, to marital, and to parental love. What Spinoza was actually thinking of when he wrote about love, however, was none of these. In fact, he was not thinking especially of any variety of love that necessarily has a person as its object. Let me try to explain what I believe he did have in mind.

Spinoza was convinced that every individual has an essential nature that it strives, throughout its existence, to realize and to sustain. In other words, he believed that there is in each individual an underlying innate impetus to become, and to remain, what that individual most essentially is. When Spinoza wrote of “that passion by which the…[individual] passes to a greater perfection,” he was referring to an externally caused (hence a “passion”—i.e., a change in the individual that does not come about by his own action, but rather a change with respect to which he is passive) augmentation of the individual’s capacities for surviving and for developing in fulfillment of his essential nature. Whenever the capacities of an individual for attaining these goals are increased, the increase in the individual’s power to attain them is accompanied by a sense of enhanced vitality. The individual is aware of a more vigorously expansive ability to become and to continue as what he most truly is. Thus, he feels more fully himself. He feels more fully alive.

Spinoza supposes (plausibly enough, I think) that this experience of an increase in vitality—this awareness of an expanding ability to realize and to sustain one’s true nature—is inherently exhilarating. The exhilaration may perhaps be comparable to the exhilaration that a person often experiences as an accompaniment to invigorating physical exercise, in which the person’s lungs, heart, and muscular capacities are exerted more strenuously than usual. When working out energetically, people frequently feel more completely and more vividly alive than they do before exercising, when they are less fully and less directly aware of their own capacities, when they are less brimming with a sense of their own vitality. I believe it is an experience something like this that Spinoza has in mind when he speaks of “joy”; joy, as I think he understands it, is a feeling of the enlargement of one’s power to live, and to continue living, in accord with one’s most authentic nature (emphasis added).