Libby Fischer Hellmann's Blog, page 47

August 4, 2013

Reviewing From The Other Side

This is a reprint from CrimeSpree magazine but it appeared back in 2007. So I think it’s safe to say most of you never read it. I’ve updated it.

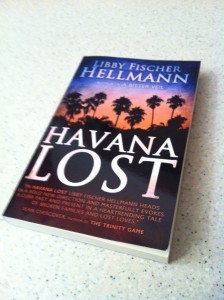

As I wait for the reviews of Havana Lost to come in, I can’t help but remember the first (and only) first professional review I wrote. It was in 2007 for Marcus Sakey’s Good People, (btw, Marcus has a new thriller out called Brilliance , and you really need to read it). My review ran in the August 2007 edition of Chicago Magazine. Happily, I liked the book and said so. But I never want to write another review. Ever.

I don’t know how other authors can write reviews. (I’m not talking about blurbs—they’re a different kettle of fish,). As a writer, I know what a torturous investment I make in my own writing. How I write myself into a corner. And rewrite myself out of it. How I try to stretch to the next level. Create characters that come alive on the page. Avoid contrived plots or resolutions. Weave issues that add depth to the story. And that’s just the writing process.

There’s also the second guessing. The nail-biting when the ARCs go out for review. Was I too heavy-handed? Did the subplot work or fall flat? Was the dialogue natural? What will the trade reviewers say?

Oh, and let’s get real about something else. Some authors claim they don’t care if a review isn’t good. That any review is better than none at all. Some authors even claim that, in some ways, a bad review is better than a good one. I don’t buy it. Having been the recipient of the occasional dunderhead myself (Of course, they totally misunderstood the conceit. And the plot. And the characters), I want to hide for a week in my basement or drown myself in wine.

So, having gone through this many times myself, how could I possibly judge another author’s effort? How do other writers do it? Boston Globe mystery reviewer Hallie Ephron, who is an incredibly successful author herself, understands and says knowing what a writer goes through keeps her from being snarky. “I don’t take it lightly,” she says. “I try to be respectful.” If something doesn’t work for her in a book, she tries to be specific and descriptive rather than judgmental. She also makes a point of telling readers that, as a writer, she might quibble about points that wouldn’t bother a non-writer; for example, an inconsistent point-of-view.

So, having gone through this many times myself, how could I possibly judge another author’s effort? How do other writers do it? Boston Globe mystery reviewer Hallie Ephron, who is an incredibly successful author herself, understands and says knowing what a writer goes through keeps her from being snarky. “I don’t take it lightly,” she says. “I try to be respectful.” If something doesn’t work for her in a book, she tries to be specific and descriptive rather than judgmental. She also makes a point of telling readers that, as a writer, she might quibble about points that wouldn’t bother a non-writer; for example, an inconsistent point-of-view.

Sounds reasonable. But even supposing I could do what she does, how far would I go? The objective of writing a review is to tell potential readers whether they should invest their time and energy and dollars in a new book. Because I’m a wordsmith, I can probably describe all the good points of a book. I could probably even make the book sound like the best thing since the Guttenberg Bible. But because I’m a wordsmith, I choose words carefully. I could easily forego a superlative hear and there. Write around a deficiency in craft or concept. We’ve all read reviews that damn with faint praise. Reviews in which what isn’t said sometimes screams louder than what is.

And what if I truly don’t like a book? Should I review it at all? What good does it do? Carl Brookins, a veteran author who also reviews crime fiction, straddles the line.  He generally finishes a book he’s decided to review, even if the book has problems. He’ll write about the problems, but he’ll make a point of saying something positive as well. “Because I know what writers go through, I think it’s incumbent on me to mention both the good and the bad.”

He generally finishes a book he’s decided to review, even if the book has problems. He’ll write about the problems, but he’ll make a point of saying something positive as well. “Because I know what writers go through, I think it’s incumbent on me to mention both the good and the bad.”

There’s also the problem of knowing the people you’re reviewing. Over the years I’ve met a lot of people in this business, including reviewers. Some are even my friends. How do they stay objective when reviewing me? Don’t get me wrong. A great review makes my day. But sometimes I wonder whether the reviewer might have been going “easy” on me because we know each other.

And what if I like the person, but I don’t like the book? Hallie Ephron avoids the whole issue by not reviewing books written by friends. She also won’t review a book if she’s given it a blurb. But what about subsequent books by the same author? Even she isn’t quite sure about that. “How long is the ‘statute of limitations?’” she asks. “Eight years? More?” In those cases she’s glad for support and counsel from the Globe. Carl feels differently. If he knows the author, he’ll still review the book. If he knows them well, though, he’ll say so in the review and will focus exclusively on the book. However, he acknowledges there might occasionally be a subconscious effect, particularly if he likes the author. (Do you like me Carl? Pretty please?)

Both Hallie and Carl say the dramatic decline in print review space isn’t necessarily a bad thing. They both predict that book bloggers and review websites may ultimately reach more “qualified” readers, i.e., those apt to buy and/or read crime fiction. Still, newspaper reviews, when they do appear, play a critical role. “We owe it to bookstores, libraries, and publishers to use mass market channels when we can,” Hallie says.

Regardless of the venue, authors who review other authors’ work have stores of courage and precision I don’t. After dipping my toe in the water, I don’t intend to dive in, but those who do have my utmost respect and admiration.

.

August 1, 2013

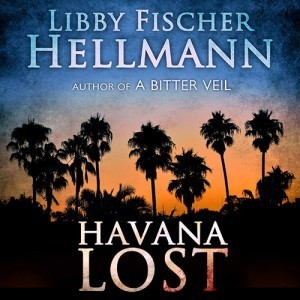

Audio of Havana Lost

Happy to report that you can pre-order the audio of Havana Lost at Audible. It sounds great: James Lewis and Diane Piron Gelman did a fabulous job –

Happy to report that you can pre-order the audio of Havana Lost at Audible. It sounds great: James Lewis and Diane Piron Gelman did a fabulous job –

Listen to a sample of Havana Lost

Play

Enjoy!

.

July 30, 2013

Let’s Hear It for Bitch Reads!

This is a reprint of a column I wrote last month for Women’s Voices Magazine. The August issue is out tomorrow with a new column. I hope you’ll come on over and check it out. There are dozens of smart, articulate, talented women writing about everything you could imagine. You can find it here.

This is a reprint of a column I wrote last month for Women’s Voices Magazine. The August issue is out tomorrow with a new column. I hope you’ll come on over and check it out. There are dozens of smart, articulate, talented women writing about everything you could imagine. You can find it here.

I confess: I’m a wordsmith. And because it’s summer, we’re all looking for beach reads, right? But, like most wordsmiths who enjoy playing around with letters, I decided to transpose a couple of them in the word “beach,” and—voila! A niche genre is born.

Actually, it’s not new. The Bitch has been with us since civilization began. I mean, really, Eve, did you have to go after that apple? Poor Adam was trying to do the right thing, but there you were, tempting him and leading him astray for your own purposes.

Yes, that’s one of the criteria that defines a bitch.

Ambition is another. So is self-centeredness. A devious mind. Spiteful or malicious behavior. And while none of you reading this column could ever be a bitch, we’ve all labeled someone else one at some point or another. I know I have.

There’s even an academic study about bitches, called The Bitch is Back: Wicked Women in Literature by Sarah Appleton Aguiar, in which she divides bitches into four categories that include the domineering shrew, femme fatale, castrating bitch, and more.

But, here’s the thing. With just a few slight adjustments, a bitch can become a bombshell. That’s because the qualities a bitch possesses, if channeled more constructivel, can describe a strong, capable, confident woman. Someone we admire and respect.

Tina Fey and Amy Poehler were the first I remember to explore the upside of being a bitch in their unforgettable Saturday Night Live skit back during the 2008 election:

So in the spirit of letting our hair down, having some fun, and staying cool, I say it’s time to honor our inner bitch. Here are some of my favorites.

[image error]

You cant get much bitchier than Barbara Stanwyck (Phyllis Dietrichson) who seduces Fred MacMurray (Walter Neff) in Double Indemnity so he will help her kill her husband for the insurance money. She is a consummate bitch: fearless, ambitious, focused. She knows what she wants, and God forbid anything or anyone gets in her way.

[image error]

Talk about your domineering mother. Christine Crawford’s memoir about growing up Mother Joan paints Mama as quite an abusive bitch in Mommie Dearest. According to Christine, Crawford neglected her children, cared only about her career, and, of course, couldn’t abide wire coat hangers. Curiously, after the book was published, a number of Crawford’s friends (including Barbara Stanwyck) refuted the events Christine wrote about in the book. That made me wonder: Who is the real bitch here? Is this a case of the apple not falling far from the tree?

[image error]

Keep in mind that a bitch doesn’t have to be an adult. Remember Veruca Salt in the Willy Wonka film Charlie and The Chocolate Factory? “Daddy, I want it all… and I want it now.” We’ve seen teenage girls act bitchy in plenty of YA novels and films, but Roald Dahl takes the concept of a bitch to a much “younger” level in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

And lest we forget rock ‘n roll’s contribution to bitch-dom, there was “Runaround Sue,” immortalized in the early Sixties by Dion. (Okay… yes—I’m dating myself).

[image error]But my favorite bitch is Scarlett O’Hara. Conniving and deceitful, Scarlett is a woman who never loses sight of what she wants and never gives up. Margaret Mitchell throws everything she’s got at Scarlett, including the Civil War. But Scarlett perseveres. And though Rhett leaves her at the end, we know that somehow, some way, Scarlett is going to win him back.

In fact, Scarlett, more than the others above, is a bitch with whom you can identify. And empathize. At least I can, because even when her motives are dishonorable, she accomplishes good things. She takes care of Melanie, she rebuilds Tara, she grows the sawmill business, she dotes on Bonnie. It’s a little like ALL THE KINGS MEN (Another wonderful Southern novel, btw) in which Willy Stark, a scheming Machiavellian politician, still achieves good things for the people. For me Scarlett is almost a bitch by default—she just can’t control her impulses.

[image error]Now, I don’t want to leave you with the wrong impression. Most women in literature are not bitches, and I want to give a shout-out to a debut novel that’s Southern, all about women, with not a bitch in the lot. Well, mostly. In fact, Saving Ceecee Honeycutt is one of the most life-affirming, delightful reads I’ve had the pleasure of losing myself in since The Help. It was written by Beth Hoffman, and the best news is that her second novel, Looking for Me, just came out. I highly recommend you read her! You won’t regret it.

Enjoy Your Bitch Reads!

.

Havana Lost Trailer

Happy to report that the HAVANA LOST video is the Shelf Awareness “Book Trailer of the Day!”

You can find it here.

.

July 27, 2013

Writing Lite #10 — Less is More

This installment of Writing Lite is a wrap-up of some language tips, all under the general umbrella of “Less is More.” It includes how much description and backstory to use, plus adjectives and words to strip out of your fiction.

This installment of Writing Lite is a wrap-up of some language tips, all under the general umbrella of “Less is More.” It includes how much description and backstory to use, plus adjectives and words to strip out of your fiction.

.

July 24, 2013

Lean Where?

Ex-VP of Global Online Sales and Operations at Google and a former Facebook CEO, Sheryl Sandberg is a powerful woman. Her best-selling first book Lean In – Women, Work, and the Will to Lead, deals with the importance for women to ‘lean into’ life to capitalize on both professional and personal opportunities. A heady mix, the book includes a long, hard look at a woman’s role – or the lack of one – in business leadership, development and government, and explores the contemporary role of feminism.

Ex-VP of Global Online Sales and Operations at Google and a former Facebook CEO, Sheryl Sandberg is a powerful woman. Her best-selling first book Lean In – Women, Work, and the Will to Lead, deals with the importance for women to ‘lean into’ life to capitalize on both professional and personal opportunities. A heady mix, the book includes a long, hard look at a woman’s role – or the lack of one – in business leadership, development and government, and explores the contemporary role of feminism.

According to Sandberg, the key to female success isn’t necessarily pushing harder. It’s about being attentive, remaining objective, focusing on emerging life and work opportunities. In Sandberg’s world, women who know and understand their own passions, calculate risks boldly, reject pressure, and say ‘boo’ to fear smooth the rocky paths of life and work better than others.

As a writer who enjoys breaking stereotypes, I get her point. The themes in her book resonate, where against the odds, and sometimes dire circumstances, women take control of their destinies.

Three kinds of women; the good, the bad and the ugly

I write about three kinds of women, none of whom are heroes in the traditional sense (well, maybe a little). All of them, however, are characters who “lean in” on their own. They are women who deal with extraordinary circumstances in unexpected and sometimes extraordinary ways, and I love writing about all of them.

Flawed but honorable

First there are the flawed but honorable women, imperfect in many ways, yet they have high levels of empathy for others. Ellie Foreman and Georgia Davis are both examples, as is Frankie Pacelli, at the beginning of my latest book, HAVANA LOST. Frankie knows her mother and father don’t approve of what she’s doing. She understands why. But she goes her own way anyway, calculating that an honorable, open, honest life with her lover Luis is better than living without him, no matter how hard her defection and disobedience will affect her family. In her own way Carla is another flawed but honorable woman in HAVANA LOST.

We are all flawed; it’s part of the human condition. But we are not all honorable. I find it fascinating to discover how some characters become cowards and lose all sense of honor when they run into difficulties, while others remain true to themselves—even heroic—when obstacles happen.

Women without choices

The second type of women I love writing about are women whose choices have been taken away from them. For example Anna in A Bitter Veil travels to her new husband’s native Iran with high expectations only to find life is at first difficult, and then impossible. Her freedom is restricted and threatened simply because she is female in an oppressive male-dominated society. She’s up against the wall, all her options have vanished, and many would call her a victim. In her darker moments, she might even agree. But not for long. Something—some core inner strength—propels her to endure, perhaps even prevail against her problems. She is a survivor.

The same goes for Arin and Mika in my novel An Image of Death, as well as Lila and Alix in Set The Night on Fire. I put them in desperate situations, force them to cope with the challenges and, like the women championed by Sheryl Sandberg, they all eventually manage. I like to think that, put in a similar situation, I’d react the same way, that I would fight to protect my innermost ‘self’. But what do any of us know, until it actually happens?

The witch bitch

The third type of female I love to write about is the witch-bitch. Take Ricki Feldman, who’s a recurring character in several of my novels, and somewhat of a nemesis for Georgia Davis. She’s sharp, willing to cut corners, and says one thing while doing another. You really want to hate her, and she deserves it, but every once in a while she does something … well, almost noble. So you can’t hate her 100%. She’s flawed and damaged and has more baggage than the carousels at O’Hare, but something human has survived under her hard shell of disappointment and disillusion.

My favorite witch-bitches are Ricki, Frankie Pacelli in HAVANA LOST, and Marian Iverson, who was an important character in my first novel, AN EYE FOR MURDER.

More questions than answers

Women are far from perfect, and creating characters that reflect their flaws and foibles is one of the most enjoyable parts of writing my novels. Who is your favorite strong fictional female character, and why? If you’ve read Lean In – Women, Work, and the Will to Lead, what did you think about it?

Image source: Jaquandor

.

July 21, 2013

I Moved to Chicago for the Weather

This is a reprint of an essay that appears in the current Mystery Readers’ Journal, Fall edition, which is all about Chicago. The magazine also includes essays by nearly two dozen other Chicago authors, including Marcus Sakey, Michael Sherer, Jack Fredrickson, Sheldon Siegel, and others. For more, c

heck it out here.

This is a reprint of an essay that appears in the current Mystery Readers’ Journal, Fall edition, which is all about Chicago. The magazine also includes essays by nearly two dozen other Chicago authors, including Marcus Sakey, Michael Sherer, Jack Fredrickson, Sheldon Siegel, and others. For more, c

heck it out here.

Um… actually that’s a lie.

The truth is I moved to Chicago for a job. However, the weather is never far from Chicagoans’ minds. In a word, it’s frightful, especially from November through March, when the sun rarely shines and snow piles up higher than parked cars (or used to before climate change). It’s also pretty lousy in July when summer punishes the prairie with hot, arid days and nights. Nelson Algren said it best:

“Chicago is an October sort of city even in spring.”

Chicago: City on the Make.

It’s an apt metaphor. Chicago is an inherent paradox: all bluster, business, even bombast on the surface; underneath, though, it’s a place where darkness creeps in around the edges. June may be busting out all over Chicago during the day, but you don’t want to be in the wrong place on a cool June night. Even during Chicago’s fleeting midsummer, there’s an uneasy recognition that as the days get shorter and the nights blacker, the dark can swallow you whole.

I’m not sure I understood the depths of that darkness when I moved here thirty-five years ago. At the time I thought Chicago was the best-kept secret in the country: a city with a stunning lakefront nestled in the shadows of skyscrapers… a terrain so flat you could ride a bike for miles… a place where the Blues poured out of bars as freely as the beer. I loved the city’s beauty, its bluntness, its energy, even its hokey parochialism, seen on TV news via Bill Kurtis’s raised eyebrow, Fahey Flynn’s equanimity, or Walter Jacobsen’s perpetual fury. The city boasted two baseball teams, a decent football team, and Michael Jordan. Second City began here. Work was king, and people got up early. They stood in line, and when you went into Marshall Field’s, someone actually asked, “May I help you?”

It’s one of the few big cities through which it’s easy to drive, and the view of the skyline driving into town from the north or south is still magnificent. For me Chicago was a place of possibilities. Despite the Old Boy’s network, I had the sense that if someone had a good idea and was willing to work for it, they could make it here. And on clear, crisp days with the city spread out before me, it seemed like a sure bet.

It’s one of the few big cities through which it’s easy to drive, and the view of the skyline driving into town from the north or south is still magnificent. For me Chicago was a place of possibilities. Despite the Old Boy’s network, I had the sense that if someone had a good idea and was willing to work for it, they could make it here. And on clear, crisp days with the city spread out before me, it seemed like a sure bet.

It wasn’t until I ventured out of my geographical comfort zone that I began to hear and see the stories Chicagoans don’t like to talk about: the despair and isolation in Uptown where diversity may be king, but most of the people are paupers… the ruthless segregation on the South Side that breaks Chicago into two separate cities… the homeless curling up in cardboard boxes on Lower Wacker Drive… the never-ending cycle of graft and political corruption that, while it has put four governors in jail, still underlies everything that gets done or doesn’t get done in Chicago.

I have felt that hopelessness first-hand, tutoring eight and nine year olds, all the while knowing that a year or two hence, the girls will be selling their bodies and the boys their souls to the gangs. Chicago can break your heart that way. People who arrive here optimistic and eager never get the break they need. Others come seeking refuge but find only terror. People with good intentions see those intentions thwarted and manipulated.

Crime-fighters are supposed to protect the vulnerable, but there’s a thin line between law enforcers and law breakers. Everyone knows someone who can fix a ticket. And most know someone who’s connected. People understand that you can indict a ham sandwich in Chicago if necessary. Everything is political, even the pizza.

Is it unique to Chicago, this struggle between the light and the dark? Of course not. Most urban areas face the same issues. But Chicago is bigger and louder and more brazen than other cities, so its struggle seems more intense, more consequential.

In fact, the noir soul—or should I say soulessness—of Chicago has settled in my soul, and I feel compelled to peel back its layers like the onion for which the city was originally named. Why? Because the struggles that define Chicago make for extraordinary conflict. And conflict is the essential ingredient of good fiction.

So my muses lurk below the surface in the back alleys, blue-collar haunts, and dive bars of Chicago. I gravitate toward settings and time periods where dreams fail, lovers cheat, and money is short. I am drawn to the fear, the despair, the shards and detritus of those who tried and failed, and those who never had a chance. And when I hear about the heartbreak and desolation, or, occasionally, the dazzling redemption, I try to work them into my writing.

Since 2002 I have published ten novels and at least a dozen short stories that are set in Chicago. My first four crime novels, the Ellie Foreman series, are set on the affluent North Shore of Chicago, where darkness hides underneath the soccer fields and manicured lawns. But each of Ellie’s stories also takes place in a Chicago neighborhood you don’t want to end up in after dark. My subsequent three thrillers, featuring PI Georgia Davis, begin in Chicago but one ends up in Wisconsin and Arizona. My three stand-alone thrillers are largely set in Iran and Cuba, as well as Chicago in 1968, but even the foreign-set novels use Chicago as a home base.

It’s strange. I moved here from Washington, DC where I worked in broadcast news. Over the years I would meet transplants from Chicago who invariably told me how much I’d love it here. That I was the kind of person who would appreciate and thrive in the city. At the time I thought they were just full of hometown braggadocio, and I didn’t take them seriously. But it turned out they were right. I know without a doubt that had I not moved here, I would never have become a writer. Chicago has sucked me into its maw. It’s my kind of noir.

.

July 18, 2013

Inside Havana Lost

I’m so pleased to present my first “Glossi.” A Glossi is a short online magazine that you can create (free) about a subject. I did mine, of course, as a short virtual tour of Cuba, using excerpts from HAVANA LOST.

Enjoy!

Click to view Havana Lost on GLOSSI.COM

.

July 17, 2013

Revolutionary talk – Why I set my novels in violent times and places

In fiction, they say, there must be conflict on every page, even if it’s only someone wanting a glass of water that he or she can’t get. I tend to overdo things in general, and creating conflict is no exception. What could provide more conflict than a revolution? When my characters’ lives unfold against an uncertain and potentially violent backdrop, almost anything can—and does—happen.

In fiction, they say, there must be conflict on every page, even if it’s only someone wanting a glass of water that he or she can’t get. I tend to overdo things in general, and creating conflict is no exception. What could provide more conflict than a revolution? When my characters’ lives unfold against an uncertain and potentially violent backdrop, almost anything can—and does—happen.

Extreme times demand extreme survival strategies

I can’t imagine a more extreme conflict than a revolution. It affects everything and everyone: from individuals, to families, to neighborhoods, cities, countries, and regions. A revolution can impact a society’s culture and art, its food supplies, education, income, personal freedoms, literature—the entire Zeitgeist. It affects the way people trust or don’t trust one another. It splits families in two. It makes everyday living dangerous and unpredictable. Essentially, it touches every aspect of life.

When you layer that extreme conflict on top of conflicts that already exist in a person’s life, those people become unpredictable. Some become heroes, some cowards. I love to write about that evolution in a character, and I’m often surprised by what happens. Just when I’m convinced they’re about to behave one way, they take a different direction altogether. When that happens, it makes me feel more like an observer than a creator.

The art of unpredictability

Some readers say they love my novels because they’re unpredictable. I do it on purpose. In too many crime novels the hero or heroine does the right thing, faultless in their judgement, always emerging unharmed at the end. My plots are different. More noir. I let my characters develop the way they want, and if you expect my heroes and heroines to win their battles every time, think again. He or she might not even make it past the first few chapters if that’s the way the revolutionary cookie crumbles.

The ‘revolution trilogy’

An Eye For Murder goes back to World War Two, which, although not technically a revolution, was indeed a period of extreme conflict. An Image of Death deals with the collapse of the Soviet Union. Set the Night on Fire took place during the troubled times of the late 1960s in the US. A Bitter Veil explores a family’s life in Iran during the Iranian revolution. And Havana Lost, my latest release, is set partially during the Cuban revolution and its Special Period. But there’s also action taking place in Angola – which was and still is an incredibly violent and lawless place— and Chicago. In fact, my former publisher has labelled my latest three books my “Revolution Trilogy.”

An Eye For Murder goes back to World War Two, which, although not technically a revolution, was indeed a period of extreme conflict. An Image of Death deals with the collapse of the Soviet Union. Set the Night on Fire took place during the troubled times of the late 1960s in the US. A Bitter Veil explores a family’s life in Iran during the Iranian revolution. And Havana Lost, my latest release, is set partially during the Cuban revolution and its Special Period. But there’s also action taking place in Angola – which was and still is an incredibly violent and lawless place— and Chicago. In fact, my former publisher has labelled my latest three books my “Revolution Trilogy.”

It doesn’t hurt that I’m a history major and I love to read and do research. It’s almost Pavlovian on my part. And I find it curious that although every revolution is different, and has ignited for different ideological reasons, many end up being quite similar.

Revolution 101

Take the Russian revolution in 1917, where Tzar Nicholas and his family were brutally slaughtered, followed by years of suffering for ordinary Russian people. The French revolution, where the aristocracy lost their heads but the poor ultimately suffered most. And the Chinese ‘cultural’ revolution, where innocent people died in the millions. It’s a common theme; people want to be free, but their leaders don’t know what to do with their freedom when they get it. And it’s the ordinary people who seem to suffer most when things don’t turn out as the revolutionaries planned.

[image error]Ironically, the only revolution that was different was the American. We didn’t have a dictator or oppressive political culture. Our revolution was waged for purely economic reasons, ie what the colonists felt were unfair taxes. I wonder what that says about us.

When the only certainty is uncertainty

When I put my characters squarely into a revolution, the only thing that is certain is change… and not usually in a good way. The way my characters face up to that change and handle its challenges is what makes writing so much fun. They all have minds of their own, and like all of us, they are essentially unpredictable, especially under stress. And also like most of us, their instinct for survival is what drives them to survive desperate circumstances.

Pick your weapons… what about you?

If you could choose a revolution for me to write about, which one would it be, and why?

.

July 10, 2013

An Interview with Libby – On Havana Lost and a Writer’s Life

Well, that’s it. My latest novel, Havana Lost, is finally out in the wild, being read by a bunch of fans who have downloaded the Advance Reader Copy. I’ve already been asked a whole load of questions about the writing process, the book, the characters and Cuba itself.

Well, that’s it. My latest novel, Havana Lost, is finally out in the wild, being read by a bunch of fans who have downloaded the Advance Reader Copy. I’ve already been asked a whole load of questions about the writing process, the book, the characters and Cuba itself.

Here are my answers.

What attracted you about a plot set in Cuba? Where did the inspiration come from?

I was talking to my sister on the phone after I’d finished A BITTER VEIL. I knew I wasn’t ready to go back to my Georgia Davis series yet, even though I was already about 60 pages into it. I’d been thinking about doing a World War Two thriller—I’m continually drawn back to that period of time. Unfortunately, I ultimately realized there was probably nothing I could write about the period that hadn’t been done better by someone else.

The conversation turned to other time periods and settings, and my sister brought up Cuba. As soon as she mentioned it, I started to get that itch. It’s the kind of itch that can only be scratched by delving more deeply into the subject. I told her how I remembered my parents flying down to gamble in Havana. This was when Batista was still in power. I must have only been about 6 or 7, but I remember being jealous that they were going to a foreign country and culture. I wanted to go too. Of course, they didn’t take me.

A few years later Fidel took over and Cuba became off limits to Americans. Plus, it turned Communist!  Communism was our enemy. Because of that, Cuba seemed even more mysterious and exotic, and I remember wanting to know more about it. Then, of course, there was the Cuban Missile Crisis, which made Cuba even more impenetrable and distant. So close and yet so far.

Communism was our enemy. Because of that, Cuba seemed even more mysterious and exotic, and I remember wanting to know more about it. Then, of course, there was the Cuban Missile Crisis, which made Cuba even more impenetrable and distant. So close and yet so far.

Finally, and I’m not ashamed to admit it, I recalled one of the Godfather films where Al Pacino (Michael Corleone) and Lee Strasberg (Meyer Lansky) are on a rooftop supposedly in Havana discussing how they’re going to own the island. Shortly after that, Michael sees a rebel willing to die to overthrow Batista and changes his mind about doing business with Lansky.

That clinched it. I realized I had most of the elements for a terrific thriller: revolution, crime, conflict, and an exotic setting.

That clinched it. I realized I had most of the elements for a terrific thriller: revolution, crime, conflict, and an exotic setting.

There was only one other element I needed. I enjoy—actually it’s more than that… it’s probably an obsession—writing about women and the choices they make. I needed a female character who would have been thrown into the middle of the revolution. It would be fascinating to see what she did and how she coped. Once I came up with Frankie Pacelli, the daughter of a Mafia boss who owns a Havana resort, the rest was, as they say, is history.

Are any of the female characters in HL based on you? If so, which aspects of their personalities are inspired by yours?

None of my female characters are based on me. All of my female characters are based on me. I think it’s impossible for an author not to share shades of themselves through their characters. The issue isn’t so much what comes from me, though; it’s their own authenticity. Once they’re on the page, they have to be true to themselves. Consistent. They can’t do one thing on Monday, and the opposite on Wednesday, even if I want to.

Have you been to Cuba? What did you think / feel about it?

Absolutely, I went to Cuba. My daughter and I went in 2012 on a cultural tour that coincided with the Havana International Book Fair. It turns out that the Book Fair is one of the largest in Latin America, and it was packed.  We were there for 9 days. Of course we did a lot of other things and saw other places (Varadero, Cienfuegos, and Trinidad), and one day, we even ditched the tour and went on our own to Regla. I had written most of the book by then, so it was a perfect opportunity to fact-check. I’m glad I did. I got the geography of Regla wrong.

We were there for 9 days. Of course we did a lot of other things and saw other places (Varadero, Cienfuegos, and Trinidad), and one day, we even ditched the tour and went on our own to Regla. I had written most of the book by then, so it was a perfect opportunity to fact-check. I’m glad I did. I got the geography of Regla wrong.

I took hundreds of pictures, and you’ll be able to see some of them in the coming weeks.

How do you go about creating a new persona from scratch?

I write a ‘stream of consciousness’ “backstory” for each major character that includes their motivations, background, experiences and emotions. Each backstory only needs to be a couple of pages but they act like skeletons to hang the details on. Everyone has a history and backstories help me make people real, breathing life into them. You can watch a video about my process here.

How do you plot your books? Beginning to end then fill in the middle? Or plot on the hoof, as you write?

I write chronologically from beginning to end. Probably an anal compulsion, but I can’t switch around like other writers can. For example, in SET THE NIGHT ON FIRE, the middle section takes place in 1968, well before Parts 1 and 3. I thought I could write that first, since it preceded the others. Nope. Couldn’t do it. I had to write Part one, which takes place in the present, then go back to write Part 2, and then fast forward again to the present to write Part 3.

However I don’t outline… well, that’s not entirely true. I know the premise before I start, and I THINK I know who the perpetrator is. Then I start writing. What we call “a seat of the pants” type writer. I prefer that. It keeps my writing fresh, and more important, allows the characters to determine the plot, rather than me getting in their way with a preconceived notion or outline about what I think they would do. Consequently, in almost every book, the person who committed the crime changed from the person I initially thought it would be.

How long did it take you to write HL?

About a year.

Do you treat the creative process like a 9-5 job or do you only write when you feel in the right creative mood?

I used to be a lot more disciplined and wrote every morning for an hour or so. Now, though, my schedule is all over the place. Mostly because of the added responsibilities of marketing and self-publishing. I wish I could get the discipline back.

Have you ever spent a day writing them trashed the lot?

Not really.

Which is your favorite HL character, and why?

Luis and Carla. Because they are noble.

Did the plot take you in unexpected directions or did you know who you wanted to kill off right from the start?

I pretty much knew this was going to be on the noir side from the outset and that it would have a fairly high body count.

What do you think about female authors and gore – are they as good at the gory stuff as male authors?

Absolutely, and I resent the fact that anyone would think differently.

Do you enjoy writing or is it just 100% hard graft?

I hate it. It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done. But I love the notion of “having written.” And I love editing. For me, that’s where the magic happens. Still, I remain somewhat incredulous that I’ve actually published 10 novels. How did that happen?

Are you good at keeping secrets, like Luis?

No. I’m terrible. NEVER tell me a secret you don’t want out.

Where do you get the names for your characters?

I consult a lot of websites for the time and culture I’m writing about. There are also a few websites that randomly generate names. Those are fun.

That’s it for now, but keep the questions coming. I love hearing from you. And don’t forget, you can pre-order the print, ebook, and, within a week or so, even the audio of Havana Lost on Amazon right here.

Map of Cuba Image Source: Moon Travel Guides

.