Adam Tendler's Blog, page 29

September 17, 2015

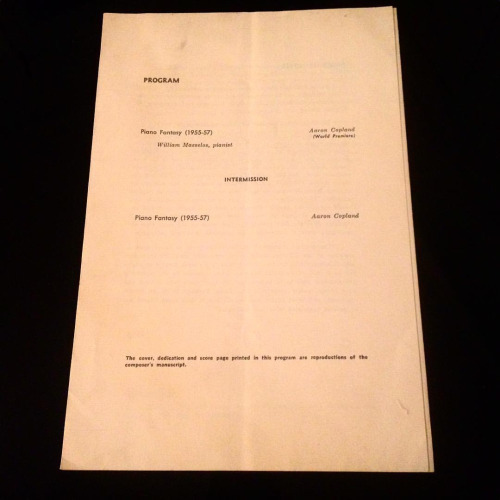

as a piano student in 1957, my friend and colleague edmund arkus...

as a piano student in 1957, my friend and colleague edmund arkus attended the infamous juilliard premiere of copland’s piano fantasy. today at our faculty meeting he slipped me the program and mouthed the words, “it’s yours.”

August 30, 2015

(via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gkBhO...)

August 14, 2015

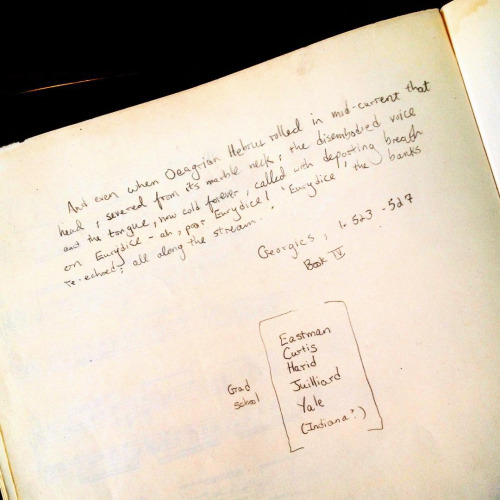

grim and kind of weird discovery in the back of my well-tempered...

grim and kind of weird discovery in the back of my well-tempered clavier book II. the “harid” mention dates me…

August 12, 2015

from two emails in which i complain about learning cage's 34'46.776" for a pianist

[two days ago]

I’m immersed in the incredibly straining activity of trying to physically internalize this nutty John Cage piece, 34'46.776" for a pianist, which no one can or should play, but of course I’ve decided to try to do. Blah blah. A Cage scholar shared the most amazing phrase with me when I wrote him for help… indeed, for inspiration…because I was majorly stalling on this piece after transcribing it note-for-note. He described the approach to the music as akin to hurling sound into silence. “Moments thrown into silence,” he said, and this might be the most helpful thing anyone has ever said to me. Like, really. But the music is still a bitch. In a program that stretches emotion and memory to such beautiful extremes, this piece aims to negate memory, to destroy association, to negate reason and connection. In other words, it wants us to seal the dam on all we [have been taught to] hold essential to music-making, but still to make music. Breathe without air. Run without gravity.

[yesterday]

While I’ve only gnawed on little pieces of 34 since arriving up here in Maine, by the end of the week I hope to have at least created some kind of physical language for the excerpt. Thinking about it tonight, I tried to remind myself (for the millionth time) that Cage was probably most interested in [experiencing a pianist’s] physical and aural problem-solving in the moment of execution, the choreographic and audible solution a pianist might come up with when handed this kind of Sisyphusian score, what the struggle might sound like and look like as the pianist works to honor each event as faithfully as possible. That manic tension, that friction, fuels the piece, so I tell myself, and makes that disconnectedness compelling to anyone bearing witness. I feel most at one with the music when in that kind of “flow” state Csíkszentmihályi writes about, flaying about and barely seeing. It’s a music that invites… in fact, demands a kind of out-of-body execution.

I also wonder if it was a big fat mistake trying to get this part of it ready for September 12th. I’m trying to remember my frame of mind a month before the John Cage Weekend last year [when I performed the companion piece to 34′46.776″, 31′57.9864″]. It was probably just as full of wonder and fear.

[note to self: today]

It occurs to me that I’m good at writing about, talking about, waxing poetically about in the most inspiring prose, how Cage, in his chance-based music, forces a player out of their comfort zone, cuts off the air supply to their habits and conditioning, and invents a music that seems intent, maybe primarily, on erecting and exploring a kind of playground of failure, to make the player live in this world until, like breathing liquid oxygen (I always think of that scene in The Abyss), their panic gives way to surrender and submission—to peace. You can breathe, as it were, once the fear and shame vanish in the face of embracing imperfection. One reaches, perhaps frenetically so, and that’s the music. Selfless. Confidently imperfect.

Yes, it’s so, so much more inspiring to write about it, to think about it, to coach myself on all of this when I don’t actually have the music in front of me, when I’m not practicing, hunched over the instrument and painfully reaching, tearing psychological muscle and feeling my body stiffen and brain freeze and breath shorten and spirits sink. I stop at the end of each passage wanting to quit, thinking about how far there is for it—for me—to go. And then I try again and watch it change.

A lot of suffocation imagery lately.

July 26, 2015

Essays Before a Bach Concert | Part 2: Scrapbook

(journal/sketch from winter/spring of 2005)

…lately I’m not dreaming much, but my brain still goes into this kind of overload, furiously juggling dates both real and imagined, interspersed with nightmare shorts where I’m missing an engagement or losing my directions on the way there. When my brain doesn’t do either of these things, it analyzes scores of music, some of them real and some of them make-believe. Everywhere repeat signs.

I’ve always mistrusted happy endings, and often feel nostalgic for things before they actually happen.

The first time I heard Book One of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier all the way through I felt like I’d just watched a movie. But it didn’t have a happy ending. To my ear, our hero realized in the final reel that his accomplishments amounted to nothing, that he arrived back where he started, never noticing his path led full circle. That’s what I heard. [My professor] facilitated the informal performance in place of our final masterclass. There were 24 of us including him, so each of us would play a prelude and fugue from Book One. I chose the key of a minor, which no one wanted because of the long fugue. The concert, if you could call it that, took a couple hours, and after it finished, in the bright yellowish-green lights of the classroom where we held it, I sat dumbfounded.

Three-and-a-half year’s worth of disenchantment with academia as a whole and the creeping confusion over my eminent and unexceptional departure from conservatory a few days later… all probably contributed to the general sense of disillusionment that I heard, or wanted to hear, in Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier [Book One]. I felt a mixture of betrayal and pure, empathetic connection. It twisted in my stomach. My veins were ice. My face flush with panic. I felt like a kid who finds out at his birthday party that his parents lied to him all these years, and he was actually born a year later than they’d always said, and he suddenly realizes he has to endure another year of being the same age.

Shouldn’t the hero return to the village with a dragon carcass dragging behind him? The end didn’t sound so much triumphant as it did defeated and humbled and weathered and wearied.

I loved how I felt in the moment. Crushed. I wanted to stay in it for as long as I could. That’s probably why I couldn’t move, there under the florescent lights.

At the end of [Herman Hesse’s] Siddhartha, we find the Buddha guiding riverboats, a ferryman smirking to himself, rowing silently when he has so much he can, or could, share with his passengers. That’s admirable?

(photo taken in Bloomington, Indiana, in the summer before senior year, 2003)

______________________________

(a paper on the contested issue of temperament in Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, which I might have called “Tuning in Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier,” from 2001 or 2002)

The term, die gleichschewebende Temperatur, existed in the time of Johann Sebastian Bach, as did the term, wohltemperirte. The first stands for equal tempered, or “equally beating temperament,” and the other means “well-tempered.”[1] That Bach named his monumental two books of forty-eight preludes and fugues in all major and minor keys, Das Wohltemperirte Clavier (The Well-Tempered Clavier), leads us naturally to assume that the composer intended the pieces for performance in the well-tempered system of clavichord tuning. However, three centuries of debate over the above assumption refute the outward simplicity of our deduction’s validity. What does “well-tempered” actually mean in the case of the Well-Tempered Clavier? Have our perceptions of the work and thus the reception of Bach’s creative intention suffered from ages of inaccurate performance? Do sources from the time, or can the music itself, provide indications as to how Bach considered the matter of tuning with reference to his keyboard works and specifically the Well-Tempered Clavier?

In the following, I will provide evidence that Bach intended the Well-Tempered Clavier for any accommodating keyboard instrument; meaning any keyboard able to play suitably in all keys. I will also argue against the claim that within the well-tempered system, Bach composed his keyboard music with a special concern for tuning-related programmatic effects. Ultimately, I will assert that we should make and consider any and all speculations upon the creative process and possible objective within the Well-Tempered Clavier on the expectation that Bach aspired for an equal-sounding system. Subsequently, the composer constructed his epochal two books of preludes and fugues in a fashion that best exemplified and most-subtly demonstrated this wish.

Most every publication arguing either for or against the use of well-temperament in the Well-Tempered Clavier does so with the support of highly intimidating, usually indecipherable mathematical figures and equations. While this paper aims to avoid calculations and graphs, we should approach and articulate certain terms and principles before continuing. While tuning procedures have most certainly benefited from technological advances through the ages, the use of detecting audible beats, the frequency-relationships between intervals, has remained an ever-necessary tool in tuning practice. A beat results when the sound waves between tones differ in frequency to an extent that the human ear can listen to and measure both the coming-together and phasing-out between the waves.[2] The recognition of even beating between tones helps a tuner to regulate the space between intervals on the keyboard. Historical and present-day scholars and theorists have used cents to measure space between intervals in a more scientific and theoretically accurate manner. On an equal-tempered piano of today, 1200 cents lie within one semitone or half-step[3]. In order to break from ancient and restrictive tuning procedures, musicians through the ages have manipulated cents and beat relationships between intervals in order to regulate a discovery made by the Greeks nearly three thousand years ago; what we now call the Pythagorean comma[4]. The Pythagorean comma symbolizes the difference of 23.460 cents which occurs between twelve perfect fifths and seven perfect octaves[5]. In equal and well temperament, tuners rationalize this difference by either equally or subtly distributing the difference among other intervals.

Why the bother? To ignore the fundamental relationships between tones on the keyboard leads to what we know as wolf-tones, or the wolf-fifth. These phenomena occur in relation to other notes; meaning, an E major triad may sound fine, but an A-flat major triad may sound like howling wolves on accord of how one has organized the intervals and relationships between tones (in this case, the double role of G#/Ab stands at stake). When composers like Bach relied on mean tone tuning, which originally functioned within the boundaries of wolf-tones and problem key-areas, they composed in a manner that did not demand an extended key scheme. We see this in Bach’s dance suites for keyboard, whose movements all share the same key and modulate only to closely related keys, and also in the Inventions, whose keys do not require special tuning maneuvers in order to play them all as a set (Major Keys: Eb, Bb, F, C, G, D, A, E Minor Keys: f, c, g, d, a, e, b)[6]. As tuners and composers began to temper certain intervals and hence develop different forms of what we now think of as well temperament, the treatment of wolves changed from avoidance to rationalization. As the theoretical knowledge of intervals and tuning procedures developed, so would grow the theoretically possible number of tones to an octave. While by the mid-seventeenth century, inventors took this concept literally and had designed keyboards with up to thirty-two keys to an octave,[7] others, like influential theorist Andreas Werckmeister and J.S. Bach himself eventually chose to pursue methods which pushed the wolf tones to less-likely key areas (i.e. keys with numerous sharps or flats) in order not to affect the sounds of keys used more often.[8] This usually involved widening the major thirds and tempering the fifths by a certain number of cents per interval as deemed appropriate and least noticeable.[9] Documentation of these methods dates back to the year 1511.[10] Some scholars refer to these procedures as “circular” tuning as well as the more general, ‘well-temperament’.6 The above concepts illustrate in part the technical challenges facing Bach when he composed the Well-Tempered Clavier in 1722 (Book I) and 1742 (Book II), and help to give us an opening perspective as we continue to develop our conclusions concerning the role of well temperament in J.S. Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier.

We should study the keyboard music of Bach, and especially the Well-Tempered Clavier, trusting that he intended them for performances in well temperament and not equal temperament. While equal temperament, as a scientific and musical achievement, began to emerge in the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth century, to actually obtain an equal keyboard temperament required intense theoretical figuring, preparation, tools, and patience.[11] Although the difference in performance between equal-tempered and highly equalized well-tempered keyboards may sound indistinguishable to our ears, or even to the ears of baroque listeners, the philosophical difference between these concepts with respect to the mathematic distinctions and pragmatic methods of acquisition made the distinction very real.[12] Instead of delving into complicated ratios to illustrate the difficult intrinsic characteristics of equal temperament, we should contend rather that Bach would have ignored these theoretical approaches and tuned his instrument in a well-tempered manner.

Scholars recognize fully that Bach tuned his own harpsichords, and most accounts contend that he could do so within fifteen minutes.[13] C.P.E. Bach contended further that “no one could tune and quill his [father’s] instrument to his [father’s] satisfaction.”[14] These accounts suggest that Bach had an efficient manner of tuning which so happened to result in a convincingly equal-sounding system, as when C.P.E. Bach states famously about his father: “he knew how to temper so exactly and correctly that all keys sounded handsome and agreeable.”[15] Lorenz Mizler, eighteenth-century writer and contemporary of J.S. Bach reflected that the composer “did not occupy himself with deep theoretical considerations of music.”[16] Above all, if even C.P.E. Bach did not endorse, or at least bother with, exact equal temperament after the death of his father, but rather stated that a keyboard “must be well-tempered” so that “the ear will hardly notice it and one can well use all twenty-four keys,”[17] why should we insist that his father practiced in an opposite manner? In Bach’s time, every common tuning besides equal temperament (including even mean tone temperament from the fifteenth through eighteenth centuries)[18] tampered with the fifths and thirds and thus rationalized the sounds of particular key areas in order to insure modulatory freedom and safety from highly disagreeable wolf-tones. Our decision remains then between any conceivable circular tuning procedure ranging from those proposed by Werckmeister and the variations upon these that composers, like Bach, most likely pursued, or the one extremely complex and mathematically-based possibility of equal temperament, which has no variation. The evidence presented above supports the previous assumption.

One might consider this whole debate futile in light of the direct reference to well temperament made in the Well-Tempered Clavier’s title. The work clearly aims to equalize the performance and composition of all major and minor keys, so how could he endorse its performance on an unequal instrument? We will understand that Bach uses the term wohltemperirte generally, and does not refer to any specific tuning procedures, but instead to any tuning that allows for inoffensive performance in all 24 keys. The requisite of having to play in every key should not automatically lead one to assume that Das Wohltemperirte Clavier means “the clavichord tuned in equal temperament.”[19] Instead, we may look to Werckmeister, the father of well-temperament, who said that “if we have a well-tempered clavier, we can play all the modes beginning on any note and transpose them will.”[20] Werckmeister later reasoned his avoidance of equal temperament, which he claimed to have invented thirty years prior, to his wish of keeping the purer thirds in frequently used keys and harsher intervals in less-likely keys as opposed to equally distributing the damage as in equal temperament.[21]

While it remains unlikely that Bach used an exact method of tuning proposed by Werckmeister (not even Werckmeister himself tuned his keyboards with literal adherence to his publishings)[22], the term ‘well-tempered’ in the Well-Tempered Clavier’s title expresses the above idea of a ‘good’ temperament in which one can play in all of the keys. Had Bach used the term for “equally beating temperament” in the work’s title, the rarity of and difficulty in achieving this temperament would have tremendously limited the audience and performers of his music, let alone the composer’s own opportunity to hear his music as indicated. Bach claims in the dedication of the original Well-Tempered Clavier that he “composed and noted [the set for] the benefit and exercise of musical young people eager to learn, as well as for a special practice for those who have already achieved proficiency and skill in this study.”[23] The prerequisite of equal temperament would have alienated nearly everyone Bach supposedly intended the set for. The well-tempered clavier Bach specified in the work’s title symbolized, insured, and publicized that one could suitably play the work only on any well-tempered keyboard instrument.

Scholars like John Barnes (in periodical Early Music, 1979), Jack Greenfield (in Piano Technicians Journal, 1984), Mark Lindley (in Musical Times, 1985) have devised convincing proposals for the tuning system Bach probably used; a variation on Werckmeister’s third well-temperament (Werckmeister III), to which they hypothesize that Bach tempered six fifths instead of four in order to further equalize the keyboard’s tones.[24] For our purposes, however, we may choose to bypass present-day theories on account of their inherent speculative nature. As we have discussed previously, within any circular temperament, not just equal temperament, one has unlimited opportunity to modulate enharmonically and by other means to any major or minor key.[25] Having emphasized this enough, we must use the above to understand how little capability we have to prove which of these well-temperaments Bach used or imitated and intended for the Well-Tempered Clavier, despite the strengths of plausibility in methods proposed by theorists and scholars.

Since we have historical evidence but no proof to back any tuning system contrived today for the Well-Tempered Clavier, we therefore cannot feel entirely sure about what certain keys sounded like in relation to each other when Bach tuned his keyboards. Subsequently, this uncertainty nullifies most deductions that Bach’s key choices, modulations, or other compositional decisions had any programmatic intention. For instance, theorist Philip Jones argued in 1980 that both Bach’s final transposition of the French Overture (Partita in B minor) from C minor to B minor and the presence of Picardy thirds in the Well-Tempered Clavier helped to prove the composer’s affinity for equal temperament. The French Overture’s dominant and supertonic areas involve F# and C#, frequently the wolf key-areas in well temperament, and some Picardy thirds in the Well-Tempered Clavier serve enharmonically as wolf-tones, involving intervals that would inherently spoil the endings of otherwise perfectly unfolding pieces.[26] Scholar John Barnes responded that the Overture benefits from circular tuning because of its “fiery dominant” and “clean but serious minor tonic” and claimed that the cents-difference on the Picardy thirds would not offend baroque ears.[27] Similarly, using well temperament as a force for dramatic tension, early-music theorist Mark Lindley claimed in 1985 that Bach’s Toccatas in F# minor and G major “suffer” in equal temperament.28 In the case of the F# minor toccata, where a sequence repeats 24 times, the author interprets this as an exploration of “modulatory nuances” and doubts that Bach would use the opportunity instead as a regression “to aimless wandering in the midst of an otherwise extraordinarily expressive composition.”[28]

As valid as these arguments sound, I assert that we can never know that Bach’s particular tuning allowed for a “fiery” dominant in the French Overture, or that the tuning made the sequential passage more titillating to our ears in the F# minor toccata. Alternately, the argument that many of the Well-Tempered Clavier’s pichardy thirds would sound out-of-tune in well temperament helps us very little simply because we do not and can not know exactly how Bach himself handled these situations when he tuned his keyboards.

The Well-Tempered Clavier’s dedication, discussed earlier, demonstrated Bach’s hope for a widespread application and comprehension of his work. The composer’s decision to treat harmonic style, modulation, and dissonance in the same manner regardless of common or un-common key area supports my idea that Bach avoided gambling with effects in these pieces and instead concerned his composition to more practical matters: accommodating the range of instruments he expected and anticipated his audience to use. [29] All composers in Bach’s time knew not to trust that an effect intended on one keyboard instrument would surface effectively on any other. This would result in “not beauty, but chaos” about the keyboard.[30] Clearly, Bach would not take such chances with the Well Tempered Clavier.

The somewhat popular present-day argument that the Well-Tempered Clavier sounds less-satisfying in equal temperament stands as a moot point of little interest because of Bach’s limited exposure to equal temperament and the clear fact that he did not compose the work for it. Of course it therefore may sound better in a form of well temperament. On the other hand, to argue that Bach intended the Well-Tempered Clavier for equal temperament because of potential out-of-tune phenomena that could occur within the well-tempered scheme remains equally fruitless in that, as we have discussed, we cannot know for sure how Bach tuned his instrument. We only know that, in tuning, the composer clearly sought to balance the relationships between the tones of his keyboard while still using an exclusively unscientific well-tempered approach.

Did Bach have a perfect, personalized well temperament which allowed free reign over any and every harmonic area of the keyboard, extinguishing all possible wolves with the perfect tempering plan? Or did the composer find alternate ways to work within the well-tempered system, assuring to some extent the same results on other well tempered keyboards? To illustrate the latter, we will observe Bach’s use of safe intervals, avoidance of distant modulations, and textural treatments within the Well-Tempered Clavier’s distant keys, accommodating and clearly adhering to the constraints of any well-tempered system.

Some theorize that, despite the original dedication suggestive of the opposite, Bach used the Well-Tempered Clavier as a personal compositional exercise in how to write successfully for keyboard in all keys.[31] As concerns with and advancements of keyboard temperament flourished during the time in which Bach composed the Well-Tempered Clavier, we can safely assume that he “was concerned with problems of keyboard temperament when he wrote it.”31 In the most general sense, Bach triumphed over wolves and dangerous key areas in his keyboard music, including the pieces of the Well-Tempered Clavier, by remaining harmonically within a somewhat conventional scope. In other words, most pieces modulate to the dominant or subdominant tonality via brief sequential passages, return to the tonic by the same means, and do not explore distant keys for the sake of exploration. In fact, 1/3 of Bach’s music does not need a well-tempered system in order to navigate, and this figure grows once we consider that the notes and passages corresponding to distant keys usually appear as passing tones, sevenths of chords, or other momentary dissonances.[32] We owe this to Bach’s generally conservative approach to harmonic scheme in his keyboard writing, which stems ultimately from his desire to avoid obvious clashes on account of well temperament’s innate restrictions.

Of course, the above fails to consider those pieces, like those in the Well-Tempered Clavier, in which Bach had no choice but to use conventionally-avoided keys as tonic. In these cases, Bach had to find a way to work with the wolves. In most well-temperaments, the avoided keys (usually those with many sharps) expose their sour notes most clearly in major thirds. This owes partly to the enharmonic roles of the involved notes with concern to more conventionally-used keys (F-A as opposed to C#-E#, where F does not necessarily equal E#). The rate of different major third occurrences in the Well-Tempered Clavier clearly corresponds to the involvement of wolf-tones within the interval.[33] In the Werckmeister III tuning, as well as those temperaments proposed by present day scholars as possible variations on Werckmeister III that Bach may have used, the number of major thirds on C numbers around one-hundred and forty times, while those on F# and C# occur between thirty and forty times.[34] Regardless of how Bach stretched or tempered these problem intervals, the above figures show that the composer nonetheless either avoided or used them sparingly. In doing so, Bach helped to nullify or at least lessen the possible disturbances to the ear on both his own personally tempered instrument, but also with important consideration to the well temperaments of keyboards belonging to other performers studying the Well-Tempered Clavier.

Still, when major thirds in cumbersome keys do occur, as seen with moderation above, how does Bach treat them? In two clear cases, the C# major and F# major preludes of Book I, Bach works around the awkward sounding thirds by setting the music in fast, two-part counterpoint.[35] Consequently, the ear does not notice the unnatural wideness of the major third intervals. Similarly, in the F# minor prelude of Book II, Bach devotes nearly the entire first measure to the tonic but only devotes an eighth note to the dominant, an awkward C#-E# interval.[36] In these instances, Bach uses textural effects and modifications in order to create an equal tempered illusion for the listener.

Times and trends changed quickly in the time of Bach. By the mid-1700s, theorists viewed Werckmeister’s tuning procedures as obsolete and unrefined, scoffing that “in his day, it was best.”[37] Equal temperament emerged from the cloak of enigma and began to weigh as the new movement of musical progress thanks to its dedicated proponents.[38] Even the heirs of Bach implored German composer and critic Friedrich Wilhelm Mapurg to write a petulant forward to Bach’s Art of Fugue in which he blasted well temperament and its “diversity in the character of the keys,” accusing that they served “only to increase a ‘diversity’ of bad sounds in the performance.”[39]

While we may want to hesitate in assuming that Bach cursed well temperament and wished by all measure to compose in equal tuning, our evidence has nevertheless discouraged the personage of a composer who exalted in distant keys and programmatically inspired out-of-tune moments. If anything, we have observed Bach’s utmost concern with the obliteration and avoidance of the “barbaric entities,” as he called them, lurking within well-temperament .[40] While Bach may have claimed this monumental opus as a set of practice pieces for students, we instead should more-appropriately view it as a multi-faceted and poly-strategic statement attesting to the unrestricted possibilities of tonal composition within an unequal tuning system; a cycle performable on any keyboard capable of playing in all 24 keys, titled under the general guideline: wohltemperirte.

Bibliography

Barbour, J, Murray. Bach and the Art of Temperament, The Musical Quarterly XXXIII, 1947

Barnes, J. Bach’s keyboard temperament: Internal evidence for the Well-Tempered Clavier. Early Music, Vol.7, 1979

Blackwood, Easley. The Structure of Recognizable Diatonic Tunings. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979

Blood, William. ‘Well-Tempering’ the clavier: five methods. Early Music, United Kingdom Vol.7, October 1979

Di Veroli, C. Bach’s Temperament. Early Music, Vol.9, 1981

Isacoff, Stuart. Temperament. New York: Random House, 2001

Jones, Philip. Bach and Werckmeister. Early Music, United Kingdom Vol.VIII/4, October 1980

Lindley, Mark. J.S. Bach’s Tunings. The Musical Times, Vol. 126, December 1985

Lloyd, LL. S. Intervals, Scales, and Temperaments. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1963

editor: Slonimsky, Nicolas. Webster’s New World Dictionary of Music. New York, 1998

Stauffer, Donald W. Piano Tuning for Musicians and Teachers. Birmingham: Stauffer Press, 1989

________________________________

[1] Barbour, J, Murray. Bach and the Art of Temperament, The Musical Quarterly XXXIII (1947) p.67

[2] Stauffer, Donald W. Piano Tuning for Musicians and Teachers. Birmingham: Stauffer Press, (1989) p.15

[3] Blood, William. ‘Well-Tempering’ the clavier: five methods. Early Music, United Kingdom Vol.VII, (October 1979), p.495

[4] Lloyd, LL. S. Intervals, Scales, and Temperaments. New York: St. Martin’s Press, (1963) p.9

[5] Blackwood, Easley. The Structure of Recognizable Diatonic Tunings. Princeton: Princeton University Press, (1979) p.59

[6] Barnes, J. Bach’s keyboard temperament: Internal evidence for the Well-Tempered Clavier. Early Music, Vol.VII, (1979) p.249

[7] Isacoff, Stuart. Temperament. New York: Random House, (2001) p.182

[8] Editor Nicolas Slonimsky. Webster’s New World Dictionary of Music. New York (1998) p.598

[9] Slonimsky, 598

[10] Di Veroli, C. Bach’s Temperament. Early Music, vol.9 (1981) p.220

[11] Barbour, 68

[12] Barbour, 68

[13] Barnes, 236

[14] C.P.E Bach, letter to Forkel, 1774, from Lindley, Mark. J.S. Bach’s tunings. The Musical Times, v. 126 (December, 1985) p.721

[15] Lorenz Mizler (using description by C.P.E. Bach) in Musikalische Bibliotek. Leipzig (1754), from Lindley, Mark. J.S. Bach’s tunings. The Musical Times, v. 126 (December, 1985) p.721

[16] Minzler, 123, from Lindley, 722

[17] C.P.E. Bach. Versuch uber die wahre Art das Clavier zu spilen. Berlin (1753) p.10, from Lindley, Mark. J.S. Bach’s tunings. The Musical Times, v. 126 (December, 1985) p.721

[18] Barbour, 72

[19] Parry, Sir Hubert. The Art of Music. NY (1985) p.203, from Barbour, 67

[20] Werckmeister, Andreas. Musicae mathematicae Hodegus curiosus. Frankfurt and Leipzig (1686) p.120 from Barbour, 69

[21] Werckmeister, Andreas. Hypomnemata musica. Quedlinburg (1697) p.28, from Barbour, 70

[22] Kellner, H.A. J.S. Bach’s well-tempered unequal system for organs. The Tracker, Vol.40. (1996) p.25

[23] Slonimsky, 23

[24] Barnes, 245

[25] Blood, 491

[26] Jones, Philip. Bach and Werckmeister. Early Music, United Kingdom Vol.VIII/4 (October 1980) p.511 -513

[27] Barnes, John: amendment to Jones, Philip. Bach and Werckmeister. Early Music, United Kingdom Vol.VIII/4 (October 1980) p.511-513

[28] Lindley, Mark. J.S. Bach’s Tunings. The Musical Times, Vol. 126 (December 1985) p.721-6

[29] Barbour, 80

[30] Barbour, 73

[31] Barnes, 236

[32] Barbour, 80-81

[33] Barnes, 245

[34] Barnes, 245

[35] Barnes, 237

[36] Barnes, 238

[37] Mitzler, L. Musikalische Bibliothek, iii. Leipzig (1737) p.55, from Lindley 722

[38] Isacoff, 221-3

[39] Isacoff, 217

[40] Mizler quoting Bach, 162:, from Lindley 721: “In the four bad triads there is a rough, wild or, as Maestro Bach in Leipzig says, barbaric entity…”

July 16, 2015

Essays Before a Bach Concert | Part 1: The Last Time

I haven’t performed Bach in public for over ten years. The music has receded into my private practice, a communion that happens strictly behind closed doors, and I’ve cycled through the Bach keyboard output this way several times. Last winter, I learned and memorized the Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue and then put the score back in my bookcase without playing it for with a soul.

It wasn’t always this way.

In conservatory, I acted as more of a public disciple, but then again, one sort of has to play Bach publicly with some regularity as a music school undergraduate. Before my senior year, I’d already studied and performed a number of preludes and fugues, an obscure keyboard suite, a partita, and a Liszt transcription (probably doesn’t count), all while still cycling through Bach repertoire on my own. I diligently analyzed the harmonies, color-coded voices, practiced the counterpoint in various combinations—soprano/ tenor, alto/bass, and so on—and the music would open itself to me, blossoming in all its tangled, tiered, motive-upon-motive-upon-motive genius. I couldn’t go deep enough. I loved it.

And then something happened, and I wish I knew what exactly. For my senior recital I had to prepare Bach’s 2nd Partita in c minor, rather standard fare, not the end of the world. But it also wasn’t a choice. Maybe that was the problem. I had a teacher at the time who sensed my interest—my defensive, protective interest—in musical miscellanea. In my junior recital, for instance, I’d played a Fantasy and Fugue…by Mozart.

So I have a feeling that my teacher wasn’t about to let me slide through a senior recital with any more baroque eccentricities. He needed me to prove myself in a major work—no ifs ands or buts. No fugues by Mozart.

I set to work, going about what had become a routine of analysis and pick-apart practicing. But after 6 months, maybe longer, the piece hadn’t come together. Of course, Bach always feels like a tightrope walk, but my mind seemed to set traps like never before, traps strewn across every melodic line, every harmonic shift. “What’s next?” “What’s next? WHAT’S NEXT!” It was just a matter of time, usually seconds, before I’d inevitably come up short (”I don’t know!!”), something would snag and the piece would come screeching to a halt.

Nevertheless, I had a senior recital to play! I reserved the hall, arranged the program printing, and taped posters all over the school. (I loved making posters. As a sophomore, I’d created a series of posters for my IU debut, fashioning them around giant images from Madonna’s SEX book. The piano faculty commenced a summit to consider expelling me for obscenity.)

The day came for my hearing. Some background: at IU, a student has a “recital hearing” upon which the faculty actually bases their grade. He or she typically passes and then has permission to play the recital, but the recital is actually more of a formality; I don’t even think one’s teacher has to show up.

I remember starting with Bach, but that’s about all I can harvest from that buried memory. Maybe I stopped? Maybe I improvised? Whatever happened on that stage with my Bach, it set the tone for the rest of the hearing, which also included Beethoven’s “Waldstein” Sonata, another of my teacher’s choices. I left the hall in a cold sweat. That, I remember. And I didn’t pass.

Not passing, by the way, happens, but not a lot. It’s somewhat exceptional, I think (or at least have told myself), to actually fail a hearing. The same faculty that once voted to expel me rallied to support, but quizzically so. By then I’d actually studied privately with many of them, and the overall question amongst them seemed to be: “Huh?” One faculty member said—and I’ll never forget it—“We could have passed you, but we just know you can do better.”

I thanked him, and then went about tearing all of my already taped-up posters down from the halls of the music school. My mother cancelled her flight and friends made other plans, and I receded to my little dorm-type apartment, littered with crumpled posters, and didn’t emerge for days. When I finally practiced again, I did so on an upright in a tiny room in the basement of a neighboring dorm, a room that no one in the music school would ever conceive of using and probably didn’t even know existed. I wanted to drop out.

No, really. I thought about it. I’m not cut out for this, I thought, and even though in a matter of days, after my winter exams, I’d have more than enough credits to graduate early, I wanted out right then and there. Fuck it.

But alas, I scheduled another hearing. A friend gave me some beta blockers—the only time I’ve ever taken them, and I noticed very little difference—and I took the stage again. Terrified and wincing through each agonizing note, narrowly escaping every psychological trap, I somehow passed. The recital happened a couple days later. A recording exists, but I’ve still never listened to the whole thing. I have no idea how I sound in the Bach.

I announced to my teacher that I would graduate early and wouldn’t attend any ceremonies. I was pretty much just leaving. “Do you really think you’ve learned all you can learn?” he asked. “Here? Yes,” I said.

There were 23 people in my studio at the time, and with my teacher, that made 24. He had an idea. Instead of our final masterclass, we would all play Bach’s complete Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1, all 24 preludes and fugues with each of us performing one key. What a beautiful idea, I thought, and a nice way to say goodbye.

bit.ly/24pianistswtc

June 22, 2015

kind of teaching a lesson over txt

kind of teaching a lesson over txt

June 12, 2015

Edward T. Cone: Prelude XV (from 21 Little Preludes) …or...

Edward T. Cone: Prelude XV (from 21 Little Preludes)

…or never underestimate what lies inside a simple, ‘slow’ quarter note

(The complete set appears on the forthcoming album, Edward T. Cone: Solo and Chamber Music, from Ebb & Flow Arts)

June 10, 2015

Henry Cowell: The Fairy Bells…

getting there

A video posted by Adam Tendler (@adamtendler) on Jun 10, 2015 at 7:03pm PDT

Henry Cowell: The Fairy Bells…

getting there

May 16, 2015

sugar

a girl on the subway, talking to a friend, just referred to art today as “confectionary intimacy”

or at least that’s what i heard