Adam Tendler's Blog, page 38

November 26, 2013

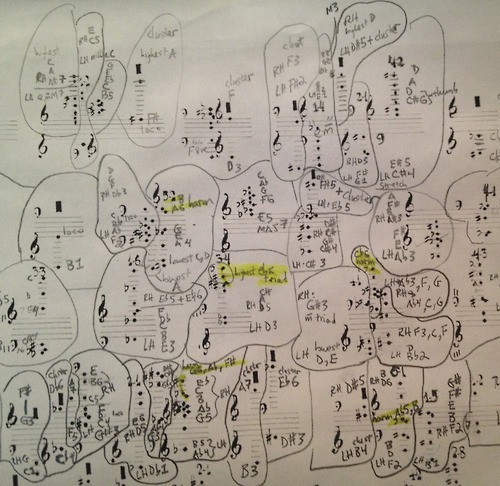

working on Cage’s Winter Music, rainy NYC night, 12:30am

working on Cage’s Winter Music, rainy NYC night, 12:30am

November 21, 2013

On Hurting People, or, Another Version of How I Came Out

My last relationship before coming out was with someone I met over Craigslist. It was summer of 2006, and I’d just finished my fifty-state tour. I was watching my sister’s apartment in Malibu for the summer, working at a veterinary clinic, and Craigslist seemed like the safest playground for cruising. He and I met for lunch after exchanging a couple pictures and chatting over Yahoo, another closet go-to for me in the early-to-mid 2000s. I actually really liked him, and we dated for a little over a month, my remaining time in California before I would move to Texas.

Still, throughout our sex on the beach (better in theory, by the way), our dinner dates, our phone calls and invitations into each other’s non-closet worlds—he met my sister, for instance—I never actually had his phone number. When he called, “Unavailable” flashed across the screen. I met him thinking his name was Jason. Later, he told me it was John.

When I left California, we sort of said we’d keep in touch. Everything with him was sort of. And I felt embarrassed admitting to myself that I would actually miss him, something I’m sure I never confessed out loud.

But we did keep in touch. In Texas, he kept me abreast of his ever-changing email addresses and Yahoo screen names. And when I visited L.A. again that year, we met up and I even almost spent the night. Almost. Sort of. When I told him about how I would make my Houston debut at the Rothko Chapel that spring playing John Cage, he said he would come. I thought he was joking until a week or so before the performance when he sent me his flight information. We still had known each other less than a year, and these days rarely communicated, but I would be hosting him before the week’s end. After some fancy footwork, I had my visiting sister and mother staying in a Houston hotel, and he, who I described to them as a “visiting friend,” staying with me.

He did come to Houston. He did come to the concert. But he didn’t stay with me. Instead, he booked himself into a bed and breakfast nearby. The night of my performance, he almost stayed over, but retreated in the wee hours of the morning to his rented room a few blocks away. The next day, he explored Houston as I went on a trip to Galveston with my sister and mother. I was miserable and they couldn’t understand why. I’d just had a successful concert. They were visiting. I had a friend in town. What did I have to mope about? I couldn’t tell them the truth, which I could barely bring myself to comprehend: I was finally, undeniably, living a double life, and this is precisely when, through the years, I told myself I would come out. I moved to Houston with the personal resolve to no longer lie about my sexuality. That is, to no longer tell people I was straight. Still, I wasn’t necessarily ready to call myself gay. I just wouldn’t answer the question if it came up. But I always told myself that once I started really, truly lying to my family, once I was no longer just hooking up but rather conducting deeper and longer-lasting side-affairs, that’s when I would do it.

And here it was.

Later that night, John and I went to a Greek pizza restaurant and I told him about the crossroads at which I’d arrived. It didn’t go well. “I don’t need to label myself to feel better about myself,” he said. “It’s not such a big deal to me.” And I would argue back, “But you would never tell your family about me, and you would if I was female. So it is a big deal to you.” And on it went. He’d tell me that I was pressuring him to categorize his sexuality, and I would ask him incredulously, “Is this working for you? This kind of secret life? Because it’s not for me. Not anymore.”

It was the first time I’d said such a thing out loud to another person. It also hurt me that this guy, this John, would rather conduct our relationship behind a closed door than even consider joining me in the open. It felt like a personal affront, like I didn’t mean that much to him. “I just flew across the country to see you,” he said. “And you want evidence?”

We didn’t even try to spend that night together. He went back to his room and I returned to my apartment. My sister and mother, banished to their hotel, had no idea a war was being waged in Montrose, Houston’s gay ghetto where I, of course, had opted to live earlier that year.

The next day, John and I awkwardly roamed the city’s parks and attractions. I barely said a word, still infuriated about how he could misunderstand the boiling point it had taken me years to hit and understand myself. He called it a need to label, I called it a need to stop a very tired and tiring masquerade. There was a difference. He couldn’t see it. Finally, I could. He left that afternoon, I think on an earlier flight than he’d originally booked.

That month, I came out to my family.

John and I exchanged a couple sporadic emails—I apologized in one of them for my behavior that weekend—and he even once sent a letter. He called around Christmastime. It had been at least half-a-year since we’d communicated, and we talked as I drove my car down Kirby Drive in Houston. When I told him that I had a boyfriend who would join me in Vermont for Christmas, he fell silent for a nearly-imperceptible moment. It’s a moment frozen in my memory, because after we hung up a few minutes later, he vanished from my life. Emails bounced back, and I’d lost the letter he sent, so I didn’t have an address. I couldn’t find him anywhere on the Internet, and wondered if I was searching for him using what had always been a fake name.

I was puzzled. I mean, had we been dating? Were we exclusive? Did this person, with whom I had such critical differences, still think of me in some way as his companion? How I could I have missed that? Perhaps just as I’d failed to see the depth of his gesture when he’d visited Texas, maybe I’d also assumed too little about our legacy after that rocky but revealing weekend.

Another little part of me actually felt as if, in coming out, I’d somehow failed him. He was strong enough to stay in the closet, so I told myself, and I’d gone and “labeled myself” and was now doing big gay things like having a boyfriend and bringing him home for Christmas. The closet always retains a kind of irrational, exotic appeal, and it never quite loses its contagious power.

He was gone. But I never stopped looking. In L.A., I’d peek into every car looking for his face, and once I joined Facebook, I would look for him every couple months. Always nothing.

Then two winters ago, riding home from a teaching gig near Newark on a PATH train, I saw him. I couldn’t believe my eyes. He was seated, talking to some professor-looking guy. On the opposite end of the train, I paced, I circled, and I contemplated how fucking weird it was to run into my California boyfriend who I’d been searching after for years on a PATH train in New Jersey.

Finally, I interrupted their conversation and said hello. He stared blankly into my greeting, as if he didn’t recognize me, then feigned some kind of familiarity. “Well, good to see you,” I said, resisting the urge to shake him, to remind him that he’d once, only a few years prior, bought a plane ticket to visit me in the Lone Star State, his first and, I can assume, only time there. But I didn’t do that. I didn’t even say his name, still wondering if I was using the real one. I wouldn’t want to embarrass him in front of his friend.

On the Journal Square platform, John and the professor said goodbye, and then he came over to talk to me. He still acted as if the memory of us was too distant to verily recall. He didn’t remember my name? He didn’t remember dating a concert pianist? He didn’t stalk me online like I did him?

"You visited me in Texas," I said bluntly. "You saw me play John Cage at Rotkho Chapel. You can’t tell me you don’t remember that."

"Yeah…" he said, as if still emerging from a fog. "Well, we should get together. Do you have, uh… you know, a boyf—, a boyfr…"

"Yeah, I do," I said. He nodded, again looking a little sad. And again, I felt a little embarrassed.

"Well, yeah let’s meet sometime for lunch," he repeated.

"Absolutely. What’s your number?"

There was silence. He squirmed. “How about you give me yours.”

"Really?" I said in disbelief. "Really?"

"Yeah… just give me your number."

And as I acquiesced and watched him enter my number into his flip phone, I thought a couple things: that either he hadn’t changed and was still in the closet, or that he was protecting himself from me because once upon a time, I had really hurt him. He closed his phone, and I knew I would never hear from him again.

It’s sad. I would have really liked to catch up.

November 19, 2013

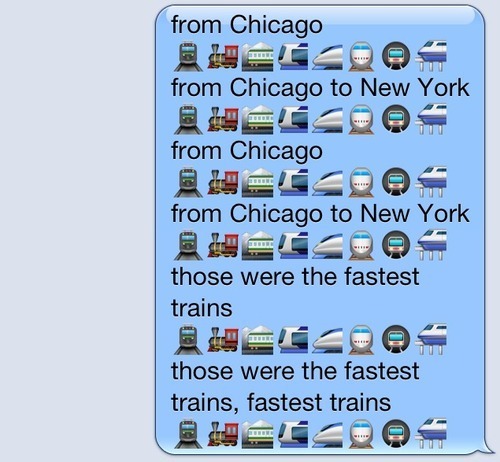

this is my iMessage cover of Steve Reich’s Different...

this is my iMessage cover of Steve Reich’s Different Trains

November 13, 2013

on realizing dreams come true

A little less than twenty years ago, I got my first paying gig playing services at a little white Methodist church in the neighboring village of Williamstown, Vermont. Like most church gigs, I had to prepare some preambulum and postlude music, as well as a number of assigned hymns, usually no more than four or five. The pay was $40 for the hour. Not bad for a twelve-year-old.

I practiced for these services all week, terribly nervous for what felt like a high-stakes performance. My mom, overhearing flubbed chords and wrong notes, would remind me about the seriousness of my new role. “You can’t make any mistakes on Sunday,” she would say. “This isn’t like a lesson.” Knowing she was right, I practiced harder.

All in all, the gig lasted about a month. Though I don’t remember any real disasters, maybe the congregation still sensed my nerves as they manifested in shaky rhythms, unintended dissonances and false starts. I was, after all, learning the ropes. “So I play the last line of the hymn first, and then the congregation sings?”

I distinctly remember one time, maybe my last time, when the minister sprang a new hymn on me at the last minute. I froze. I didn’t know what to do. My piano teacher, who scored me the gig in the first place and who (astonishingly) came to each service I played, swooped in to the rescue. Maybe he came for exactly this reason, to help in the event of an emergency.

He sat at the upright and played the hymn without hesitation. Perfectly. I watched in awe. How did he do that? He played it better at first glance than I could have if I’d had all week.

On the drive home, in a dark-hued state of disbelief, I said to my mom from the passenger seat, “I can’t believe he could just look at the hymn and play it like it was nothing.”

"He’s been playing piano for a long time, Adam," she said with the tender yet unbudging tone she’d no doubt learned to adopt whenever I sank into one of my self-deprecating funks.

"I wish I could sight read a hymn that."

"Well," she said, "someday you will."