Rick Wayne's Blog, page 90

September 3, 2017

Do you know the story of Salamongue Greymouth, Waspkeeper of Hell?

“No? I’m not surprised. His story was left out of the canon of the world religions. It taught the wrong lesson for the priests, you see.

“Salamongue was a minor angel who, in the great conflagration, spoke against patience and understanding, choosing instead to condemn his rebellious brethren with fire and damnation for daring to question the divine. Not openly of course. He spoke only in the quiet spaces, in his home and in the nooks of the cathedrals where he could bend the ears of his comrades and utter snarling, spittle-filled insults. He was seedy. And fractious. And pretended to be noble. And when the fighting was over, he was cast over the battlements with the insurrectionists, despite having only ever spoken against them.

“Oh, Salamongue remembered well that day, when he and his fellows fell aflame through hazy orange clouds, like meteors, to crash upon a land of pus and acid, to stand again, despicable and deformed, on the shores of the Sea of Despair. But where Beelzebub and Azazel and the others were praised by their peers, sitting high and fat as princes of pandemonium, Salamongue—now called Greymouth—was kicked and chided and given naught but the hellwasp farm of Blistermead, on the Venge, for it was a job no others would take.

“Hellwasps, in case you don’t know, sup on the suffering of sinners, which they collect with their bite. When they’ve had their fill, they return to their nests, where they regurgitate it into blister-like sacs before concentrating the vomitus into a thick sap by beating their wings over it and sealing it with secretions from their anal glands. There it reaches potency after a fermentation of three seasons, at which time it’s collected by the Waspkeeper and given to the brewmasters, who turn it into a bitter relish that the Lords of Discord pour over their meals. One drop is said to turn fresh meat foul and a single taste to waste a mortal man’s mind.

“But the long years of tending Blistermead left their mark on Salamongue, who became even more despicable than after the fall. Hellwasps are vicious, needy things, and they bit and stung him constantly. Stray drops of their acrid vomit burned his skin, which swelled into knots and turned callous. Over the centuries, he developed cankerous swellings on his joints and fingers and large humps on his face and back that looked much like the wasps nests right here on earth.

“Of course, his afflictions made a perfect home for his wards, who burrowed into his callouses and laid their young in the very pits of his flesh. It is said that the major demons relished most of all the mead that was fermented from back, fingers, and knees of Salamongue Greymouth, that it was a pustulous brew and tinged with blood, that the brewmasters sealed it in the ash-lined urns of the ancient dead where it aged like fine wine, and that after a century in the cellar it turned the color of charcoal and smelled of sulfurous urine and festering skin.

“So it was, every three seasons, at the time of the harvesting, the Lords of Discord made a sport of the gathering. A great horn would sound and hellhounds would bay and Salamongue would run from Blistermead and across the Venge. He knew that if he could make it to the fells across the Styx, he could disappear into the maze of crypts, where the hounds could not follow, and the Lords of Discord would grow tired of the chase and return disappointed to the hollow halls of pandemonium.

“But if caught, Salamongue would be dragged by hook and chain down to the lowest circles of the Mad Keep and his cankers and mounds would be pierced with needles and he would be placed in a great vise and pressed like a grape, and he would scream, and what dribbled from his open sores would be collected in a fermenting vat tended by the Brewmaster himself, who watched each pressing with lips wet from smacking.

“Such was the suffering of Salamongue Greymouth. Such was how he lived, with the buzzing and squirming of hundreds of tiny larva buried in the humps and hills of his back, in his face, and in his fingers.” The old conjurer wriggled his at me.

“So what happened to him?” I asked.

“Happened? Nothing! He’s still there, just like the rest of those fuckers, right where they ought to be.”

“Then why the hell did you tell me that story?”

“No reason. I just like it. It’s a good one, don’t you think?”

rough cut from my forthcoming occult mystery/urban fantasy, FEAST OF SHADOWS

cover image is “Monster Tower” by Unidcolor

September 1, 2017

The Problem with “The Three-Body Problem”

From a recent review of Cixin Liu’s Nebula Award-nominated and Hugo Award-winning “The Three-Body Problem” on Big Think:

“Why We Should Really Stop Trying to Contact Aliens” by Robby Berman

Cixin’s writing is beyond smart — it’s brilliant — and it’s science fiction of the best kind, with mind-boggling ideas and perceptions, and characters you care about. His concept of the dark forest, though presented in a work of fiction, is chilling, and very real.

In the book, Cixin uses the analogy of hunters in a dark forest, where the hunters are sentient civilizations.

The universe is a dark forest. Every civilization is an armed hunter stalking through the trees like a ghost, gently pushing aside branches that block the path and trying to tread without sound. Even breathing is done with care. The hunter has to be careful, because everywhere in the forest are stealthy hunters like him. If he finds another life — another hunter, angel, or a demon, a delicate infant to tottering old man, a fairy or demigod — there’s only one thing he can do: open fire and eliminate them.

The argument is that failure to do so will lead to the destruction of the pacifist civilization since:

When one civilization becomes aware of another, the most critical thing is to ascertain whether or not the newly found civilization is operating from benevolence — and thus won’t attack and destroy you — or malice. Too much further communication could take you from limited exposure in which the other civilization simply knows you exist, to the strongest: They know where to find you. And so each civilization is left to guess the other’s intent, and the stakes couldn’t be higher.

You can’t assume the other civilization is benevolent, and they can’t assume that about you, either. Nor can you be sure the other correctly comprehends your assessment of their benevolence or maliciousness.

This adaptation of the Prisoner’s Dilemma supposedly explains the Fermi Paradox, proposed by the physicist Enrico Fermi, who wanted to make sense of the disparity between the lack of evidence for alien races and the overwhelming odds that there are some — probably many, if not millions. The reason, we’re told, is that the universe is a dark forest full of silent hunters.

Frankly, as an analogy, submarines work much better. The whole premise of submarine warfare (in the modern age) is to detect the enemy without being detected. If there is near parity, as there was during the Cold War, this is not so much a strategy as an environment-specific tactic between two cultures that are not hiding. They’re very aware of each other. They just don’t want their ships to be seen so that they can maintain a competitive edge in case of open hostilities. The cloaking device of Star Trek fills the same need.

In conditions of near-parity, mutually-assured destruction goes a long way to suspend open war. That isn’t just human culture. It’s game theory. In conditions of disparity, however, where one (or more) civilization is vastly stronger, you wouldn’t have hunters in a forest stalking each other. You’d have something much more like what actually happens in a forest at night: predator species stalking prey species.

But game theory still applies. In nature, prey animals typically aren’t smart enough to play the Prisoner’s Dilemma, but space-faring civilizations are, which means some of the vast numbers of “prey” societies would almost certainly band together to form a large protective hegemony — any that refused would eventually be eliminated by evolution — until conditions of parity were once again met and we’re back to a Cold War model.

In the dark forest hypothesis, we’re to believe that there are millions of civilizations — a number supposedly derived from statistics — and that they’re all aware in some sense that the others are out there, and yet it’s logically impossible for any of them to communicate such that negotiations are never an option, and of those millions of civilizations, none have ever successfully banded together and so gotten more to join by their example, not in millions upon millions of years, because the bad guys trump all.

Of course, in a work of fiction, that works fine and I’m not attacking Mr. Liu or his books. In fact, it’s a standard trope in sci-fi to bend the universe politically and spatiotemporally to fit the needs of your story, where most writers set up a system of technology and transport that more or less mimics earth in the age of ocean-going conquest. But a trope is not “brilliant” or “very real” and suggesting we should shut down SETI “Right. Damn. Now.” is alarmist and anti-rational.

The motive here is the supposed heat death of the universe, where effectively immortal species are already planning ahead for life in a few billion years. (It’s possible, I suppose.) But then, the heat death is either avoidable or it’s not. If it’s not, then everyone is doomed, regardless of who’s left standing. If it is, then there’s no real existential threat. In fact, it may even be worthwhile to bring as many species into the “cleanup effort” as possible.

I suspect the reason the scenario presented in “The Three-Body problem” is so convincing to people is because the conditions it requires appear to be the most plausible in each case, so if each condition is the most plausible, then surely the result is the most plausible, right?

Wrong. Being the single most plausible scenario, a relative measure, doesn’t make anything plausible in absolute terms. (Read up on a heuristic called Representativeness.) For example, we don’t actually know for sure that there will be a heat death of the universe. It’s very possible — and may even be likely — but for the dark forest hypothesis to work, it must be true.

Furthermore, for the heat death to be true, our current understanding of thermodynamics must be more or less complete and unimpeachable. You have to accept that what humans believe now at this point in history will never be trumped by any other discovery (the way Einstein trumped Newton). What’s more, you have to accept that a host of other scientific speculations are NOT the case: the multiverse, for example, or that it’s impossible to trigger a big bang or to make internal changes to the universe that allow it to live on.

To put it in numerical terms (albeit artificial), if you have a series of six necessary conditions that must be met for an outcome to obtain, and all six are individually the most likely outcome — for simplicity, let’s assign a probability of 70% to each — then the odds are:

0.7 x 0.7 x 0.7 x 0.7 x 0.7 x 0.7 = 0.1178

Or about 12%, meaning there’s an 88% chance that some other scenario is the case. Despite that each condition is individually the most likely, it’s still not likely to happen in real terms.

Think of it this way. Cixin Liu presents us a Caveman’s Dilemma: that the only options available to an advanced star-faring civilization are “to club or not to club.” But that requires the “no communication” condition. Civilizations must be forced to act while blindfolded, otherwise they have more than a simple dilemma. So it is removing any one of the necessary conditions produces an entirely different result.

I think it’s far more likely that problems are soluble, even universe-sized ones, and that even if a solution wasn’t ready, advanced species might — like Arthur C. Clarke’s precursors and their monoliths — impose limits on less advanced civilizations while they tried to figure it out, and then explained the problem and asked for help once a species emerged from adolescence.

Altruism appears spontaneously in nature. It can be an evolutionarily stable strategy, conferring adaptive benefits on species that adopt it. For the dark forest hypothesis to work, we have to accept that it’s always shed and/or stamped out, and that in millions of years, the effects of chance were marginal and no civilization ever took a risk that paid off. I suspect at least a few sentient races are far more robust than that.

Of course, local conditions might vary in any number of ways. It could be that humans just happen to have evolved on a planet near a psycho race, and the bad guys get to us before any of the benevolent ones do. That could happen. But that’s not what Cixin Liu writes in the book and it’s not what people are praising. In fact, it’s an argument to INCREASE our search for extraterrestrial life. We need the support!

And that raises another problem with the dark forest analogy: It’s not actually a solution to the Fermi Paradox. The forest would neither be dark nor silent. Space is a vast freezer that keeps a record of every bird call ever chirped. Mankind, for example, has been leaking radio waves for decades. Those don’t go away. They spread out, they get weaker, some get lost, but our cluster of signals will keep spreading through the void for hundreds of thousands of years (millions?) before they’re finally so dispersed that they’re completely lost to the cosmic background and not even a technologically advanced race can make sense of them.

Keep in mind, the earth isn’t simply spinning and orbiting the sun. The sun itself is moving, as is the entire Milky Way galaxy and the local group of galaxies of which it’s a part. We’re leaving a noisy wake fully laden with identifying information. Not only have we left a footprint, it gets bigger with time! The same would have been true of just about any other technologically advanced civilization, even one that went dark later — and especially any that were eventually eaten (since they would have been found).

The more likely scenario, as Bill Nye explains in the video that accompanies the book review, is that we’re just not looking hard enough — for example, that radio is a clunky technology and we should be looking across the full EM spectrum (which we’re not).

While I didn’t tackle the Fermi Paradox in my first novel FANTASMAGORIA, the premise of the book was an answer to the question: Why would aliens bother? Why would they cross such distances, even if it were relatively easy for them? It could only be to satisfy a need that couldn’t be satisfied at home — curiosity, for example. Or in the case of my book, culture.

I proposed that any species capable of the journey would have long-since figured out how to supply all its wants and needs. They would be more like the humans in WALL-E — fat and bored and looking for something to do! (There was also supposed to be a statement in there about the carnival-esque nature of fandom and our own society generally.)

Thus, the aliens in FANTASMAGORIA transmute entire planets into Westworld-like “pleasure worlds” — giant amusement parks — based on the myths and stories of the species they encounter, which was of course a great way to plausibly populate an entire planet full of stuff from classic pulp fiction: unicorns and dinosaurs and cannibal fairies and war dragons and wereninjas and a mechanical gunslinger and a shape-shifting scoundrel and a radioactive assassin — all of which physically existed there, rather than being some complex virtual reality or robot simulation.

That’s not to say my solution is the “correct” one. Nor am I impeaching Cixin Liu or his award-winning trilogy. We can do anything in fiction. We read to escape. I happen to like stories about ninja-monks with laser swords and magical powers that begin with the words “Long, long ago in a galaxy far, far away…” But then, no one is mistaking Star Wars for hard SF.

Find FANTASMAGORIA here.

Cover image is “The Landing” by Henry Ledesma.

August 27, 2017

No such thing as a good ugly woman

I’m sure many of you have seen where the NY Times put together an interactive chart that asked people to rank all the characters in Game of Thrones on a good-evil/ugly-beautiful axis. The results should be of interest to storytellers. There is a clear bi-lobed cluster.

You could argue of course that this is the result of the show’s producers rather than a statement on the culture. But per the article, the producers claimed to have picked actors (and costumed them) based on the books. More importantly, I’m not sure it matters. A movie or TV show is still a “cultural text,” same as a book, and just as open to criticism. And finally, it’s very possible that a “better” casting would have furthered these results rather than contradicted them. In the article, for example, one of the show’s creators mentioned that they were “too kind” with The Hound.

The lesson is clear. Your good characters should always be good-looking, more or less, and your evil characters shouldn’t, with two allowable exceptions:

-Women can be vixens, beautiful but evil (Cersei, Ellaria, The Red Woman, Shae)

-Men can be fat lovable oafs, ugly but true (Samwell, Hodor, possibly Tyrion)

If you take out those two tropes, the graph is pretty much a complete fit to the model.

The converse then, would also seem to be true: that no beautiful man is evil and there’s no such thing as a good ugly woman.

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/08/09/upshot/game-of-thrones-chart.html

[image error]

August 19, 2017

The Strange Uniformity of Madness

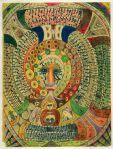

After coming across some references to Posadism, I recently got sucked into the art and philosophy of the ectocultures (my term). I don’t mean the Occupy movement or Anonymous, but the real deviants, people who either were (or maybe should have been) institutionalized. There is almost no coherent categorization, except that they’re all highly conspiratorial, anti-rational, and often invoke alien or demonic powers (or both).

Despite this complete heterogeny of thought, however, the art all has a distinctive style, often blending handwritten words and phrases — which bend and turn with the image — into extremely colorful, often diagram-like visual manifestos designed to convey truths, like the love for one’s parents, that can only be got at secondhand.

I’ll share some examples so you can spot the similarities.

These are works by Adolf Wölfli. From Wikipedia: “Wölfli was born in Bern, Switzerland. He was abused both physically and sexually as a child, and was orphaned at the age of 10. He thereafter grew up in a series of state-run foster homes. He worked as a Verdingbub (indentured child labourer) and briefly joined the army, but was later convicted of attempted child molestation, for which he served prison time. After being freed, he was re-arrested for a similar offense and in 1895 was admitted to the Waldau Clinic, a psychiatric hospital in Bern where he spent the rest of his adult life. He was very disturbed and sometimes violent on admission, leading to him being kept in isolation for his early time at hospital. He suffered from psychosis, which led to intense hallucinations.

At some point after his admission Wölfli began to draw. His first surviving works (a series of 50 pencil drawings) are dated from between 1904 and 1906.

Walter Morgenthaler, a doctor at the Waldau Clinic, took a particular interest in Wölfli’s art and his condition, later publishing Ein Geisteskranker als Künstler (A Psychiatric Patient as Artist) in 1921 which first brought Wölfli to the attention of the art world.”

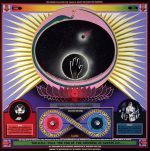

Next are works by Paul Laffoley. Again from Wikipedia: “He attended the progressive Mary Lee Burbank School in Belmont, Massachusetts, where his draftsman’s talent was ridiculed by his abstract expressionist teachers. After attending Boston public schools for a short time, Laffoley matriculated at Brown University, graduating in 1962 with honors in classics, philosophy, and art history. Laffoley has written that he was given eight electroshock treatments after the termination of ‘about a year of weekly sessions with a psychiatrist, who had treated me for a mild state of catatonia’ while at Brown in 1961.

In 1963, he enrolled at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where he apprenticed with the sculptor Mirko Basaldella before being dismissed from the institution. In a search for expanded opportunities, Laffoley came to New York to work with the visionary Frederick Kiesler, and was recruited by Andy Warhol, who wanted someone to watch television for him at all hours of the night. Laffoley watched television in the pre-dawn hours, before programming had actually begun.

By the late 1980s, Laffoley began to move from the spiritual and the intellectual, and evolved to the view of his work as an interactive, physically engaging psychotronic device, perhaps similar to architectural monuments such as Stonehenge or the Cathedral of Notre Dame and their spiritual aura.”

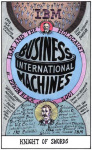

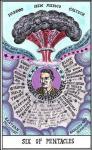

Next we have selections from a tarot deck by author Suzanne Treister created to accompany her book HEXEN 2.0, a sequel to HEXEN 2039, wherein she laid out a vision of the future based on the “interconnected histories of the computer and the Internet, cybernetics and the counterculture, science-fiction and scientific projections of the future, government and military research programmes, social engineering and ideas of the control society; alongside diverse philosophical, literary and political responses to the advance of technology including the claims of anarchoprimitivism, technogaianism, and transhumanism” (Amazon). The deck features, among other things, Timothy Leary as The Magician, Robert Oppenheimer as the Six of Pentacles, and Ada Lovelace as the Queen of Cups.

Interestingly, we seem the same style develop in Liber Novus (also called “The Red Book”) by Carl Jung, a man who was not by any reasonable definition mad but who did spend an inordinate amount of time swimming in his own subconscious.

Perhaps there’s something to it after all…

August 14, 2017

It seemed a shame to break the spell

I don’t know that I believed in magic. But I believed there were people who did, enough to kill for it. I didn’t know what was happening then. In fact, my working theory turned out to be not even close. But a few things seemed obvious enough, like why my best friend was having an affair with my boss.

The details always get messy, but it seems to me most people’s motives are usually pretty simple, and sex and money count for the bulk of them. Add power, status, and revenge and you just might have a complete list. If you could live forever, you’d check every box. Not only would you stay young and appealing, but you could amass wealth, raise armies, learn everything that could be learned, and invent entirely new sciences. You really would be a god. Like the Pharaohs of old. And eventually, you could ascend to heaven.

Sounds like heresy, right? And it is. Which is why these guys ‘The Masters’ have been working for hundreds of years to suppress any investigation into the sacred marriage, which is what produces the lapis. To keep the knowledge from falling into the wrong hands, the steps and ingredients—the recipe, you could say—for combining the male and female principles, sort of like matter and antimatter, were encoded in alchemical codes and ciphers, symbols like the athame and the chalice.

The Taoists were apparently the real masters—yin/yang and all that. Chinese mythology is definitely full of xian, immortal sages like the famous Eight Immortals, each of whom rode a dragon and who could transfer their power to a relic or tool that could be gifted to ordinary men.

Only nobody knows how to do it anymore.

The old man shuffled into the room. At first I thought he was coming to shoo me out. But when I raised my head to defend myself, I saw he had a teacup and saucer in his hand. He set it on the little side table next to me.

“Charles thought you might like some tea.”

I looked at the time on my phone. It was after six. And no messages from Kell.

I looked at the tea. It was hot.

“Ceylon,” he said, turning toward the back. “It’s all I have.”

“I thought you closed at five.”

“We do.” He nodded to the front door.

It was shut.

I scrunched my brow. I hadn’t even noticed.

“It seemed a shame to break the spell,” he said without facing me. “Now, if you’ll excuse me, it’s time for my dinner. You may show yourself out.” There was a sliding wood door in the wall that separated the bookstore at the front from his workshop at the back. He closed it.

I looked at the tea. It was steaming. I took a sip. It was warm, and I realized how safe I felt there, curled up in an old chair with a dust-and-vanilla scented book. My eyes were getting tired though. I’d been reading for hours and I was losing concentration. I flipped through the pages and scanned the “figures,” as they used to call them—text-heavy tables that looked like they had been assembled in old movable type, with strong lines and a highly serifed font. There was a whole section of them at the back, and I turned from one to the next: Schools of Magic, Classical Symbology, Mystical Doctrines, several timelines, including a list of all reigning Masters “From the Fall of the Templars to the Destruction of the Eye of Akkad,” and so on.

But there was one table in particular that caught my eye: The Orders of Practice. It had script titles in the first column and block descriptions in the second, with a third reserved for notable examples, not all of which were filled.

A Magician, it said, is any practitioner of magic. That term, however, tended to be avoided because it didn’t distinguish from the modern professional stage magician, who offers nothing but sleight-of-hand. The title Illusionist is similarly shunned.

Conjurer is the general name for anyone who brings forth that which was not there. A Summoner, then, is a Conjurer that brings forth a creature from another realm, such as a demon.

Diviner is the formal name for fortune teller. This includes the ‘low’ variety like palmists and tarot card readers as well as the more specialized schools: anything with the suffix ‘- mancy’ in the title. Most of what historians know about the ancient Shang dynasty, for example, comes from their widespread practice of plastromancy, where they inscribed questions on turtle shells—in Chinese, of course—and then pierced them with hot irons and interpreted the cracks that ran through the characters.

A Seer is anyone who has visions, which don’t always have to be of the future. Most of your run-of-the-mill psychics fall into this category, although they can be Mediums as well, which is anyone who carries messages from one place to another, such as between the living and the dead.

A Witch is any practitioner of witchcraft, which can be of the light or dark variety. Despite the common misconception, though, a witch isn’t necessarily female. Rather, it’s simply that ‘earth magic’ attracted more women than men because, first, women were historically excluded from the more arcane schools, and second, the Druids, founders of the art, had no such proscriptions.

A Warlock is any master of the dark arts, regardless of other class, and includes both men and women.

Here there was an asterisk pointing to a footnote at the bottom of the page where the author admitted to omitting “the Shamanists and Witch-doctors.” As practitioners of the most ancient form of magic, he said, there was no agreed-upon definition, nor did the shamans themselves adhere to one or another school, preferring instead to borrow from everywhere “like leeches.” The whole note sounded much like a nineteenth-century European would’ve spoken about tribal Africa.

On and on it went: Wizard, Sorcerer, Thaumaturge, Alchemist, Magus . . . What caught my eye, though—what stopped my page-flipping and led me to read the figure in its entirety—was the second entry: Enchanter/Enchantress.

“A master of mind-magic; someone who casts spells over others, often with potions and rites.”

I looked at the heavily printed words on the page. Potions and rites.

I took the last three gulps of the tea, put the cup and saucer in the kitchen, and left out the front. I stopped at the door and shouted “goodbye” and went straight to Cram’s Sour Candy.

———————————————————-

rough cut from Curse of the Red Dagger, the second course of my forthcoming full-course occult mystery, A FEAST OF SHADOWS.

Cover image is “Still Life” by Guang Yi

This is “The Love Potion” by Evelyn de Morgan

[image error]

August 5, 2017

The link between digital art and hegemony

This is “Splash goat” by Zhelong Xu.

[image error]

It’s not pottery. It’s computer generated. It was made by a Chinese artist and it beautifully illustrates how easy it will be to fake just about everything.

I expect forgery will make a comeback, only rather than forging “lost” works of art, talented artists will be paid by nation-states, media outlets, and criminal syndicates to forge reality itself — For example, digital evidence of false events and the like.

Imagine North Korea releases to the UN a jerky video of a covert US attack on their soil. It looks completely real, down to every detail. The images. The sound. The way it cuts off suddenly for no apparent reason. The North Koreans demand retribution. The US of course denies it. But everyone knows they’ve done such things before. Who do you believe?

Whoever you’re already predisposed to.

Technology can thus be used to erode the web of trust that binds us and bring us back to war. Conflicts (in real or cyber space) will rage on and off until a stable efficient equilibrium is reached, either eternally or until a single dominant hegemony suppresses all other histories.

If it’s a benign hegemony, the world will be better for it. If not, it will become an unimpeachable regime. I suspect it will look something like China — a state where people have such enough of the mechanisms of democracy to feel like they have a stake in things but which is run by the bureaucracy and the elites to a greater degree than is typical in the present-day West (but where that is also the case).

So, enjoy the cute little goat.

July 29, 2017

The Original Resistance

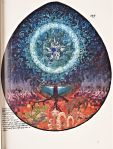

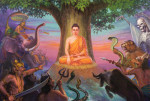

The story of the Buddha’s enlightenment is really one of the most powerful in world literature, and I wish it was as well known in the West as, say, the story of the Exodus or the Crucifixion.

Your average Westerner can look on an image of a bearded man holding a clay tablet and parse the encoded meaning (law, authority, revelation) without thought. With one glance, we are immediately reminded of an entire way of life — rules of behavior encoded in the Ten Commandments, where it’s not necessary that any of us be able to recite them to yet have a keen sense of how we are supposed to behave.

But the meaning of the image of a man sitting cross-legged under a tree, while perhaps identifiable as Buddhist, will be tied up with Western ideology: that it’s a quaint religion, that it shares in an earlier polytheism, that it’s a hippie peacenik faith maladapted to harsh realities of life, and so on, without knowing the significance of the hooded snake, the topknot, the rags, the seated position, and — most importantly — the hand that touches the earth. Everything important the artist intended to communicate is largely lost on us.

The latter, in particular, is an image that still gives me goosebumps. It is, for me, the greatest act of nonviolent resistance in all of world literature. It is Ghandi on the Salt March. It is Rosa Parks on the bus. It is Standing Rock. It’s what Mark Millar was channeling with Cap’s speech in Civil War about planting yourself like a tree.

While the image of Christ on the Cross can be felt just as powerfully, it sends to me a different message: the endurance of suffering. Surely important in an ever-imperfect world (and something I wish the peddlers of rage would heed), but for me, elevating that image as the core of your faith smacks a little too much of passive resignation.

Christians can object, and they’re not wrong. Symbology has no bounds. But it’s hard to argue that the core of Christianity seems to be the Stoicism it borrowed from it’s Graeco-Roman forebears. It’s enshrined in the famous Protestant work ethic — that this life matters less than the hereafter; that since the original sin, it’s the nature of man to suffer; that your job is to shut up and do your work.

The Bible says as much:

18 Servants, be submissive to your masters with all respect, not only to those who are good and gentle, but also to those who are unreasonable. 19 For this finds favor, if for the sake of conscience toward God a man bears up under sorrows when suffering unjustly. 20 For what credit is there if, when you sin and are harshly treated, you endure it with patience? But if when you do what is right and suffer for it you patiently endure it, this finds favor with God. (1 Peter 2)

I prefer the image below, also of a poor man dressed in rags having abandoned the wealth and title due him, with not a single possession to his name and assaulted by the evils and injustices of the world, but where Christ suffers and dies, The Buddha touches the earth and says “I am here, just as deserved as thee. And I will not be moved.”

The following is taken from Joseph Campbell’s description in The Hero with a Thousand Faces:

A majestic representation of the difficulties of the hero—task, and

of its sublime import when it is profoundly conceived and solemnly

undertaken, is presented in the traditional legend of the Great Strug—

gle of the Buddha. The young prince Gautama Sikyamfini set forth

secretly from his father’s palace on the princely steed Kanthaka,

passed miraculously through the guarded gate, rode through the

night attended by the torches of four times sixty thousand divinities,

lightly hurdled a majestic river eleven hundred and twenty-eight

cubits wide, and then with a single sword-Stroke sheared his own

royal locks—whereupon the remaining hair, two finger-breadths in

length, curled to the right and lay close to his head. Assuming the

garments of a monk, he moved as a beggar through the world, and

during these years of apparently aimless wandering acquired and

transcended the eight stages of meditation. He retired to a hermit-

age, bent his powers six more years to the great struggle, carried

austerity to the Uttermost, and collapsed in seeming death, but pres-

ently recovered. Then he returned to the less rigorous life of the

ascetic wanderer.

One day he sat beneath a tree, contemplating the eastern quar—

ter of the world, and the tree was illuminated with his radiance. A

young girl named Sujata came and presented milk—rice to him in

a golden bowl, and when he tossed the empty bowl into a river it

floated upstream. This was the signal that the moment of his triumph

was at hand. He arose and proceeded along a road which the gods

had decked and which was eleven hundred and twenty-eight cubits

wide. The snakes and birds and the divinities of the woods and fields

did him homage with flowers and celestial perfumes, heavenly choirs

poured forth music, the ten thousand worlds were filled with per-

fumes, garlands, harmonies, and shours of acclaim; for he was on his

way to the great Tree of Enlightenment, the Bo Tree, under which

he was to redeem the universe. He placed himself, with a firm resolve,

beneath the Bo Tree, on the Immovable Spot, and straightway was

approached by Kama-Mara, the god of love and death.

The dangerous god appeared mounted on an elephant and carry—

ing weapons in his thousand hands. He was surrounded by his army,

which extended twelve leagues before him, twelve to the right, twelve

to the left, and in the rear as far as to the confines of the world; it was

nine leagues high. The protecting deities of the universe took flight,

but the Future Buddha remained unmoved beneath the Tree. And

the god then assailed him, seeking to break his concentration.

Whirlwind, rocks, thunder and flame, smoking weapons with

keen edges, burning coals, hot ashes, boiling mud, blistering sands

and fourfold darkness, the Antagonist hurled against the Savior,

but the missiles were all transformed into celestial flowers and oint-

ments by the power of Gautama’s ten perfections. Kama-Mara then

deployed his daughters, Desire, Pining, and Lust, surrounded by

voluptuous attendants, but the mind of the Great Being was not

distracted. The god finally challenged his right to be sitting on the

Immovable Spot, Hung his razor-sharp discus angrily, and bid the

towering host of the army to let fly at him with mountain crags.

But the Future Buddha only moved his hand to touch the ground

with his fingertips, and thus bid the goddess Earth bear Witness to

his right to be sitting where he was. She did so with a hundred,

a thousand, a hundred thousand roars, so that the elephant of the

Antagonist fell upon its knees in obeisance to the Future Buddha.

The army was immediately dispersed, and the gods of all the worlds

scattered garlands.

Having won that preliminary victory before sunset, the con—

queror acquired in the first watch of the night knowledge of his pre—

vious existences, in the second watch the divine eye of omniscient

vision, and in the last watch understanding of the chain of causation.

He experienced perfect enlightenment at the break of day.

Then for seven clays Gautama—now the Buddha, the En-

lightened—sat motionless in bliss; for seven days he stood apart and

regarded the spot on which he had received enlightenment; for seven

days he paced between the place of the sitting and the place of the

standing; for seven days he abode in a pavilion furnished by the gods

and reviewed the whole doctrine of causality and release; for seven

days he sat beneath the tree where the girl Sujata had brought him

milk-rice in a golden bowl, and there meditated on the doctrine of

the sweetness of nirvana; he removed to another tree and a great

Storm raged for seven days, but the King of Serpents emerged from

the roots and protected the Buddha with his expanded hood; finally,

the Buddha sat for seven days beneath a fourth tree enjoying still the

sweetness of liberation. Then he doubted whether his message could

be communicated, and he thought to retain the wisdom for himself;

but the god Brahma descended from the zenith to implore that he

should become the teacher of gods and men. The Buddha was thus

persuaded to proclaim the path. And he went back into the cities of

men where he moved among the citizens of the world, bestowing the

inestimable boon of the knowledge of the Way.

The Buddha’s enlightenment is the most important single moment in Oriental mythology, a counterpart of the Crucifixion of the West. The Buddha beneath the Tree of Enlightenment (the Bo Tree) and Christ on Holy Rood (the Tree of Redemption) are analogous figures, incorporating an archetypal World Savior, World Tree motif, which is of immemorial antiquity. Many other variants of the theme will be found among the episodes to come. The lmmovable Spot and Mount Calvary are images of the World Navel, or World Axis (see page 32).

The calling of the Earth to witness is represented in traditional Buddhist art by images of the Buddha, sitting in the classic Buddha posture, with the right hand resting on the right knee and its fingers lightly touching the ground.

The point is that Buddhahood, Enlightenment, cannot be communicated, but only the way to Enlightenment. This doctrine of the incommunicability of the Truth which is beyond names and forms is basic to the great Oriental, as well as to the Platonic, traditions. Whereas the truths of science are communicable, being demonstrable hypotheses rationally founded on observable facts, ritual, mythology, and metaphysics are but guides to the brink of a transcendent illumination, the final step to which must be taken by each in his own silent experience. Hence one of the Sanskrit terms for sage is mdni, “the silent one.” Sdkyamrim’ (one of the titles of Gautama Buddha) means “the silent one or sage (mlim’) of the Sakya clan.” Though he is the founder of a widely taught world religion, the ultimate core of his doctrine remains concealed, necessarily, in silence.

July 14, 2017

A Case Study in Post-Factualism

In case you haven’t heard, The History Channel recently aired a documentary suggesting that Amelia Earhart survived her trek across the Pacific. The evidence was based mostly on a photograph, recently discovered in the National Archives (where it had apparently been misfiled), showing a woman with an appearance similar to Earhart’s sitting on a dock watching a boat haul a plane that also looked a lot like hers.

Almost immediately, a Japanese blogger posted some at-least-as-convincing evidence that the photo was published two years before her disappearance, which rules it out as proof of anything. Of course, there’s always some chance the blogger’s evidence is false — an error or a forgery — which seems doubtful, but if so, would only expand the intricacies of what is already a fascinating reflection on the question of truth in the 21st century.

The first issue is the presentation itself. Much of the information that reaches us comes completely unfiltered. In this case, a check of the Japanese national library would have revealed the photo in question and eliminated the need for a documentary. (But then, that wouldn’t sell advertising!) We spend so much time criticizing social media — and the internet generally — for its counterfactual claims, but it’s a general problem and one that existed before the telecommunications revolution. Yellow journalism has a long history.

If your response to that is something like “Well, The History Channel is hardly a bastion of investigative journalism and I’m smart enough not to rely on it,” then you’re not smart enough to have gotten the point and are very likely over-confident in your own sources (as people are) and your own ability to detect falsehoods (as people also are).

The point is: Exposure is not the same as engagement.

As a director at (what is now a division of) Nielsen for many years, I ran studies that dissected recall-based systems of media measurement. When asked to record what radio stations they heard in a day, for example, people overwhelmingly wrote down those they actively engaged with, often omitting the ten minutes they listened to a country station in the car or the oldies station their office neighbor played for several hours at work that day.

It matters. We can recall an ad — for a big department store sale, for example — and completely misattribute where we heard it. This is especially true where we didn’t consciously select the media, such as the in-store audio at a big box retailer, which most of us hear without realizing. We remember the ad and confabulate an erroneous source that we nevertheless have total confidence in.

So if your response was to dismiss The History Channel as irrelevant, you are almost certainly a victim of this effect, since it’s the over-confident who are most susceptible. We only have limited control over what we’re exposed to, after all. (Don’t worry. Your self-serving brain will invent a reason why you can be excused. The sun was in your eyes. Or you didn’t get enough sleep last night. In fair conditions, which these were not, you totally would’ve given the correct answer. TOTALLY.)

Given how much press the photo initially received, I can’t help but wonder how many exposed persons will be similarly exposed to the debunking, how many of them will believe it, and of those that do, how many of their brains will actually update their long-term memory versus simply remembering the original possibility that Earhart survived without recalling any details, including the later debunking.

Sadly, more information does not always equal more truth. It does at the outset, where we move from little to some, but there are diminishing returns. And past some fictional saturation point, just the opposite seems to be true: the more facts we’re given, the harder it is to know what’s real. If you’ve ever struggled with the counter-intuitiveness of that claim — or if you’ve never heard it before — this episode with Amelia Earhart presents a great thought experiment.

First you have to accept that truth (along with sanity) is socially defined; it is whatever the dominant members of a society think it is. That’s not to say it’s independent of facts, just that it can be — and in cases that threaten the dominant order, often will be.

In a society with relatively modest information density, where people live in small- to medium-sized cities and news is spread slowly by only a handful of outlets (i.e., newspaper and radio), any story can occupy the public consciousness long enough for it to be processed to some kind of resolution. It may not — see previous comment about yellow journalism — but it can. That capacity exists.

That means anyone in the modest-density environment who misremembered the Amelia Earhart story would likely be corrected by their peers. Yes, there were crackpots, even back in the day. Brains are not digital machines. The point is that in such an environment, there is a much higher likelihood of reaching a single socially dominant consensus. (This still left open interpretation of facts, but many of the facts themselves could be reconciled.)

These days, we obviously live in a high-information-density society, although I suspect it will keep getting denser. Someone living a century from now may look back to today as a time of idyllic simplicity, but to my feeling, we’re positively assaulted by information, not all of which comes to us through our active filter of cognitive engagement (which isn’t 100% effective anyway). Much of what we’re passively exposed to — on platforms such as this — is wrong, half-wrong, incomplete, or entirely without context.

If you think of each exposure as a colored dot on a screen, it’s easy to imagine the difference. In a modest-density environment, there are a limited number of dots and thus only so many narratives our brains can manufacture and still comply with the dominant consensus. But in a highly information-dense environment, where the screen is packed with dots of every color, there is ample raw material for out brains to find support for just about every narrative imaginable.

Furthermore, our brain adds meta-level tags to each exposure, tags that are rarely discarded with the rest. For example, there was an air of conspiracy to the Earhart story. (Why had the National Archives, usually such a paragon of organization and indexing, misfiled the photo?) If you’re already suspicious — that the Roosevelt administration knew about the Pearl Harbor attack in advance, for example — then when you heard about the photo, you likely saw further clear evidence of conspiracy. It would just seem obvious.

That subjective sense — that confidence in your beliefs created by the exposure, that snap narrative your brain used to place it into a wider context (See? I’m telling you, it’s racism all the way down!) — isn’t discarded later. Even if you come to accept the debunking, you still retain the sense of being right, that the world supports your point of view. Facts, then, rarely go deep enough to alter our narratives about the world.

So it is Trump supporters — who, despite the caricatures, have the same brain between their ears as the rest of us — will celebrate an erroneous story as true, even when they know it’s factually false, because they don’t trust the dominant media. They see History Channels everywhere! (Which isn’t entirely wrong-headed.)

In days past, serious questions likely would have occupied the public — which weren’t nearly as fractured into social media silos — until some kind of dominant resolution was reached. In this case, that Amelia Earhart did not survive. Or at least, that the photo in question was not evidence that she did.

These days, there are so many competing conversations, and they come so quickly, there’s no time to reach resolution, which is damned hard even in the best of circumstances let alone in an enormous and highly diverse society. Comment-box-sized arguments are thrown out — good and bad, for and against — with both sides claiming they “just want to contribute to a healthy discussion.” And on the sidelines, a cacophony of folks who only want to cause trouble. (Those people were always there, by the way — trolls and crackpots. But in, say, 1920, they just didn’t have a platform, save standing on a soapbox on the street corner, which is of course where we got that phrase.)

In such a world, especially where people believe they’re fighting a war for the soul of the culture, it’s not that truth or falsity doesn’t matter as much as everyone knows there are genuine practical constraints. Whatever we do or say must be done or said quickly, and so what matters most is moral rather than factual rectitude. It’s not really a lie if the moral — the conclusion meant to be drawn — is already known to be true based on “significant other evidence.”

So it is you’ll run into someone someday who’ll say something like: “I thought there was a photo that proved Amelia Earhart survived and was captured by the Japanese.” You’ll provide them a link to the debunking. They’ll check their sources and provide you a link to the debunking of the debunking, complete with annotations. And both of you will roll your eyes and walk away thinking the other is simply deluded, which is just further evidence of how good a handle you have on things, because that guy is an idiot, and thank God you don’t think like him.

http://yamanekobunko.blog52.fc2.com/blog-entry-338.html

July 11, 2017

The Three of Swords

They had a tarot deck alright, but it wasn’t what I expected. It came with a free app download. I guess there really is an app for everything.

I bought it and went to a cafe and waited for my quarry to make an appearance.

While the app was downloading, I unwrapped the deck from the plastic. There was a little instruction manual folded at the front. I perused it quick, then reached for the cards to start shuffling. Right away I noticed there were no pictures. I flipped through the deck. All the cards were all virtually identical, with a classic interlocking design on the back, and on the front, a 2D bar code on a white background with a simple border around the edge.

It was a mechanism to prevent cheating. You had to draw a random card. You had no choice because all the cards looked the same, so there was no way to stack the deck to get the “reading” you wanted.

The cards were crisp and they snapped loudly as I shuffled.

I set the deck face down on the desk. I selected a seven-card reading and tapped the start button. A description box appeared summarizing the first position, the cardinal, also called the House of the World. It’s supposed to tell us something about ourselves—some kind of insight into our overall personality.

I turned the first card and scanned it with my phone. A picture of a tarot card filled the screen.

The Moon.

It shined in full between two flanking towers. A dog and a wolf brayed, while a lobster crawled from the water at the bottom.

I had the option of using the classic Rider Waite deck or two alternate designs. There were also additional, fancier designs—apparently made by famous fortune tellers—available for in-app purchase. I used the first free alternate, which the makers of the app recommended.

I read the description to myself. It told me I was a very creative and intuitive person, which I thought was a nice way of saying I was artsy and flaky. It finished with: “In the first position, The Moon represents mystery, and all that follows will be its unraveling.”

I clicked ‘continue.’

The second position is the House of Water, which flows over the world. It is movement, activity, transition—our life goals and the unexpected changes we encounter.

I drew the second card and scanned it.

The Knight of Wands.

A man in shabby chain armor rode an unsteady horse rising on its back legs. His right hand raised a rood sprouting green leaves.

Impetuosity, it said, and the pursuit of a foolhardy adventure.

I clicked continue and the card moved on a screen to a table, next to The Moon but with a gap between.

The third position is the House of Life, which grows from wet earth. This is the house of family, love, and relationships.

I drew the third card and scanned it.

The Three of Swords.

A red heart was suspended in the air, pierced clean through by three crossing blades. Blood dripped from the bottom as rain fell from storm clouds in the distance. The Three of Swords represents heartbreak, it told me, either mine or one caused by me.

I clicked continue without finishing the explanation. The digital card moved on the screen to the table and took the gap left between the first two, but raised higher.

The fourth position is the House of Animals, which feed on the plants which sprout from the wet earth. This is our passion, our weakness, our foibles and limitations, which can also be our strengths.

I drew the fourth card and scanned it.

The Tower.

Lightning fell from a black cloud and struck a stone tower, like a battlement, which shattered, sending the pair at the top, a man and a woman, tumbling to the ground.

The app told me my foolhardy quest would end in catastrophe, a ruin of the highest order. Possibly even a curse.

I clicked continue and the card moved to a second row on the table.

The fifth position is the House of Man, both saint and sinner, who was given governance of the animals that eat the plants that sprout from the wet earth. This is our rational mind, our hobbies and activities. Work and career also fall here.

I drew the fifth card.

The Eight of Cups.

A lone figure dressed in a red hood and cape and carrying a walking stick followed the course of a river. The traveler moved away from the viewer, toward the dark and distant mountains, so it was impossible to say if it was a man or woman. An eclipsed sun hung in the sky, shining only as a thin halo around an otherwise black disc. A scatter of eight gold cups, all broken, lay in the foreground, as if they’d been smashed and discarded.

This symbolizes abandonment of old plans and aims, but in the fifth house, it was more likely to mean that magic had been used against me, driving me forth against my wishes and sending me on a journey that I would not have otherwise undertaken.

Greeeeat.

I clicked continue and it took the last position on the second row.

The sixth position is the House of the Devil, who plagues all mankind. This represents our enemies—the friends that act against us—as well as the impediments and barriers on our path.

I turned the sixth card and scanned it. I paused when I saw it, for just a moment.

Death.

It was the same reading that Mom got for me before I left. Death in the next-to-last position.

I looked at the image for a long moment. A skeletal figure in black armor rode a pale horse. He dipped a long scythe over the ground, which mowed a garden of men, women, and children. A priest in a high hat knelt before him, hands pressed together in silent entreaty.

I was about to read the explanation when my eyes caught someone approaching the building across the street. I glanced up.

“Shit!”

There he was. I scraped the cards off the counter into my purse and ran for the door.

July 5, 2017

A spell you can touch

I held up the book. “I’m so sorry. I think my friend stole this the other day.”

He scowled. His face was so old, his wrinkles magnified every expression. “Yes. She did.” He had a faint European accent.

“I’d like to pay for it, if that’s okay.”

He walked over to a wood phone stand at the back of the room, next to the last bookcase. He tapped the fat buttons of a calculator. “That will be two hundred and five dollars and nineteen cents.”

Leave it to Kell to steal the most expensive damned book in the store.

It wasn’t really, but that’s what it felt like.

I handed him two hundred and ten.

“I don’t have change,” he said.

“What?” I started to object. I took a breath. “Fine. Whatever.” Call it a theft tax.

He put the money in a drawer and headed for the back.

“I don’t suppose you could help me.”

“Probably not.”

“Dude. Can you at least pretend to be helpful?”

He squinted at me. “It wouldn’t be very convincing.”

I held up The Sacred Marriage. “This is like a history book.”

“It’s not ‘like’ a history book,” he said. “It is a history book.”

“Yeah. Fine. That’s what I said. Do you have any books on alchemy? And—” I stopped. I was going to say ‘like’ again. “The sacred marriage that aren’t history? Something more like a how-to guide.”

“Alchemy isn’t a programming language,” he chided. “There are treatises. Monographs. There are not, as far as I know, any ‘how-to’ guides.”

I waited. I hate people like that.

“Through there.” He pointed to the open archway to his left. “Turn right. Go through the parlor. Turn right again.”

I took a step. I looked to the front of the house. “Won’t that take me right back here?”

He repeated the instructions, louder. “Through there. Turn right. Go through the parlor. Turn right again.”

I sighed. “Fine.” I did as he said, careful to avoid the stacks of books on the floor. The wood slats creaked a few times. And in moments, I was back in the living area.

And there he was. Waiting.

“Go on,” he urged.

I turned my palms up. “Go on with what? Was the room supposed to look different or something?”

“Ah.” He scowled. Deeply. And shuffled back into the kitchen.

I sighed. Jerk. I spun slowly in a circle, glancing over all the books, shelved and not. I sighed and started going through them, one at a time. There had to be something.

After awhile, I heard him step back into the room. I didn’t look. I was squatting next to the bottom shelf, which is where all the large books were. I was hoping for something like an alchemical encyclopedia, maybe with references.

He cleared his throat. “This is a bookstore. NOT a library.”

“I know that. Can’t I just—” I was turning my head to argue my case when my eye caught the title, in between all the others: The Long Vacant Cupboard.

I replaced the big book in my hand and pulled it out.

“Should have done that the first time,” he said.

“Done what?”

He squinted at me for some sign of recognition. “You really don’t know anything? You’re not even a Wiccan or one of those girls who cut themselves to feed the vamps?”

I shook my head.

He harumphed. “A book, young lady, is the most magical thing there is. It is the only spell”—he lifted a faded hardbound from the shelf—“that’s patent.” He slapped the cover as if to show it was real. “A spell you can touch.” He shook it.

“A spell?”

“Yes. A spell. You know what that is, don’t you?”

I rolled my eyes.

“Words,” he said, “that make magic.”

“I know what a spell is.”

“They’re about the only magic left. That regular folks can touch anyway.” He looked at the shelves. “But even they’re going away.” He reshelved the tome in his hand.

“If a book is magic, then how is magic different than anything else?”

“Who said it was?”

He started to speak again but I interrupted him. “She stole the book when you were giving the speech, didn’t she? Turned your back and she was gone.”

He shuffled over and snatched The Long Vacant Cupboard from my hands. “The books are for sale.” He turned to put it back on the shelf.

“Fine. How much is it?”

He checked. “Eighty-nine ninety-nine. Plus tax.” Then he shelved it.

“Jeez, dude. I need to eat.”

“So do I,” he objected. “We buy books as well.”

I looked at the one by my feet. The Sacred Marriage. The one I’d just bought. I handed it to him.

He took it and examined it thoroughly. Like he’d never seen it before. “I’ll give you forty dollars for it.”

“WHAT? I just gave you two hundred!”

“Depreciation,” he said.

What. An. Asshole. “A hundred,” I said.

“No.”

I held out my hand. “Then give it back.”

He looked at it in his. “Fifty.”

“Eighty or I walk.”

He scowled. Then he turned for the back. “Criminal,” he muttered.

“Dude. What. Ever.” I took money out of my purse, added it to what he handed me, and grabbed The Long Vacant Cupboard from the shelf. “I’d like to buy this book,” I said all innocently.

He tapped on the calculator on the phone stand. The wood was old and scuffed. “That will be ninety-seven dollars and twenty cents, please.”

I counted out a hundred dollars in fives and twenties and handed it to him.

He recounted them in front of me. “I don’t have change,” he said.

I rolled my eyes. “Fine. Whatever. Just give me the damned book.”

He scowled again. “Language.” He handed it to me.

“Manners,” I retorted with bug eyes. “Can I sit?” I pointed toward the dining room. “Or are you gonna charge me for that, too?”

“You can use the chair.”

“The chair is covered—” I stopped. The books had been set on the floor.

I looked around. I didn’t see or hear anyone.

“Thank you, Charles,” the old man called. “Always did have a thing for young girls,” he muttered. He turned for his workshop, then snapped back to me. “We close promptly at 5:00,” he said. He looked at his watch. “That’s one hour and forty-seven minutes.”

I flashed the clock on my phone. I waggled it and pursed my lips like ‘Oooooooo, a magic lighted timepiece!’

——————————————————

rough cut from the revisions to Curse of the Red Dagger, second course of my forthcoming five-course occult mystery, A FEAST OF SHADOWS