Esther Crain's Blog, page 30

July 31, 2023

On a changing block in Chelsea, a Broadway set designer’s 1904 studio still stands

The luxury architecture of today’s far West Chelsea is surrounded by ghosts: of former horse stables, converted warehouses, and the steel trestle of the elevated railway that once carried trains and is now traversed by pedestrians.

Some of these ghosts offer mysterious clues about their former residents. Case in point: the blond-brick building on the south side of West 29th Street between 10th and 11th Avenues.

“John H. Young” a terra cotta plaque above the door at Number 536 reads. “Studios 1904.”

Who was John H. Young? His is not a name most contemporary New Yorkers would recognize. But if you were a Broadway theater-goer in the early 1900s, you would know Young as the celebrated set designer for some of the biggest productions in the city’s flourishing theater world.

Born in Grand Rapids, Michigan in 1858, John Hendricks Young moved to Chicago and became a painter of frescoes “dealing almost exclusively in Scriptural figure subjects,” according to askart.com.

He relocated to New York City in 1895, where he served as a scene designer for a play called The White Rat at the People’s Theater, a Yiddish theater on the Bowery.

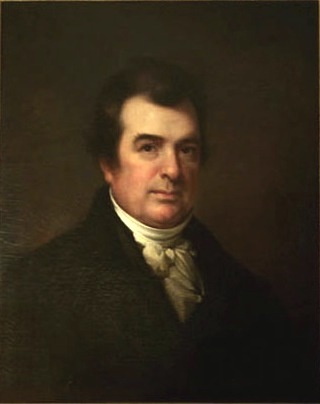

By the early 1900s, Young (above) was a sought-after Broadway set designer, “a favorite of such distinguished producers as David Belasco, George M. Cohan, and Florenz Ziegfeld Jr.,” states the Historical Dictionary of American Theater.

Young was talented and devoted to his craft, and both qualities earned him his stellar rep. “He was particularly known for presenting mechanical displays on stage—in one case, a race between cars and trains,” wrote Michael Pollak in a New York Times FYI column from 2009. “He often commissioned photographs of foreign locations, or paid American Consulates in far-flung places to send him photos and postcards, to ensure that exotic scenes would be accurate onstage.”

Though he was living in the Westchester town of Pelham in 1904, Young chose a studio location in Manhattan. He commissioned architect Arthur C.G. Fletcher, according to Pollak, to design his four-story studio—with its oddly placed oval window on the ground floor and Flemish bond brickwork on the facade.

Why Young chose West 29th Street for his studio isn’t clear. Perhaps it had a certain grit and rawness that appealed to him, so unlike the glamour and dreaminess of early 20th century Broadway—where electric theater marquees blazed from the upper reaches of the Tenderloin past 42nd Street to Columbus Circle.

Here Young created his celebrated sets and scenic paintings. Over his career he worked on more than 70 productions, including three Ziegfeld Follies, Little Nemo, and Babes in Toyland, according to the Internet Broadway Database. The wide stable-like doorway must have made it easier to transport his large set pieces to the theaters 10 to 20 blocks north.

Young’s last credit was for Sinbad in 1918, which opened at the Winter Garden Theater before moving to the Casino Theater on 39th Street and closing at the 44th Street Theater, per the Internet Broadway Database.

I’m not sure when Young left West 29th Street, if he ever did, but he passed away in Pelham in 1944.

For much of the 21st century, his former studio—still marked with his name in terra cotta above the entrance—has been home to another type of creative endeavor: a fashion brand. The studio building went on sale in 2018 for an astounding $18.5 million.

The New York Times has interior shots of this little-known space, where an artist created sets and scenes that delighted and enchanted early 19th century Broadway audiences.

[Third photo: NYC Department of Records & Information Services; fourth photo: Theatre Magazine, 1908]

July 30, 2023

One of the first botanical gardens in America bloomed in 1810 where Rockefeller Center is today

Great cities are founded on great institutions, like banks, schools, and hospitals. New York City, the most populous city in the young United States as of 1790, checked all these boxes.

What New York was missing, however, was a botanical garden—a sweeping green space filled with native and imported plants that could be “one of the genteelest and most beautiful of public improvements,” advocated Samuel Latham Mitchell, a professor of botany at Columbia College, then on Lower Broadway.

Besides elevating New York as a metropolis, a botanical garden could be used for teaching and agricultural experiments, Mitchell argued. Though Mitchell proposed the idea in 1794, it was another Columbia botany professor and physician, David Hosack, who made it reality.

Hosack was a pivotal character in some headline-grabbing events in post-colonial New York City. Born in Manhattan in 1769, he was apprenticing at New York Hospital on Broadway and Pearl Street in 1788 when the “Doctors Riot” broke out: a violent mob, enraged by rumors of physicians stealing bodies from graves for medical experimentation, stormed the building.

After finishing his medical training, he opened a practice in the city and became the personal physician of the Hamilton family. In 1804, it was Hosack (below, in an 1826 portrait by Rembrandt Peale) who tried to save Alexander Hamilton after Hamilton was mortally wounded in his duel with Aaron Burr in 1804.

But back to the botanical garden: Hosack became the leading proponent at the dawn of the 19th century. He sough funds to build it from Columbia and the state legislature, but both turned him down.

“Finally, in 1801, Hosack resolved to take the matter into his own hands, personally financing the purchase of twenty acres of land in the countryside to the north of the city, between what is now 47th and 51st Streets and Fifth and Sixth Avenues,” states the National Gallery of Art.

He named the land, which he paid about $5,000 for, Elgin Garden, after his father’s birthplace in Scotland. (Below, Elgin Garden is marked on an 1897 redrawing of the 1807 version of the Commissioners’ map of the city street grid.)

At the time, this area was part of the bucolic countryside of Manhattan, located a good 3-4 miles from the main city. Today, of course, this is smack in the middle of the concrete and steel of Art Deco Rockefeller Center.

Elgin described the land as “variegated and extensive, and the soil itself of that diversified nature, as to be particularly well adapted to the cultivation of a great variety of vegetable productions,” according to the National Gallery of Art.

After purchasing the property from the city in 1801, Hosack got to work: he asked friends in Europe and the West Indies to send him plants. He built greenhouses and hothouses; he hired gardeners to help with the labor of planting so many specimens.

By 1806, Elgin Garden had 2,000 plants, including a ring of elms, sugar maples, oaks, poplars, and locust trees. The rest of the garden was completed within a few years—one of the first botanical gardens in America.

“Walks on either side of the garden led to compartments of plants laid out according to their scientific order, and beyond them lay a nursery of fruit trees, a pond…and native plants, such as rhododendron, magnolias, and willows, which favored the moist ground adjacent to the pond,” stated the National Gallery. Rocky outcroppings were planted with pine, juniper, yew, and hemlock.”

You would think such loveliness would be maintained and preserved for decades, especially in a city that had yet to build its great public park. But by 1811, Hosack could no longer handle the financial burden.

“Operation of the garden proved too costly for Hosack, who sold the land to New York State,” wrote the New York Daily News in 1982. The state allowed Columbia to use the land for study, but the school let it go into disrepair.

“On a visit in August 1813, Hosack, who continued to collect seeds and plant materials for the garden, was distressed to find that the greenhouse plants had not been set outdoors during the summer, that many of them were missing, that the shrubbery in front of the greenhouse was choked with sunflowers, and that vegetation had overtaken the walks,” wrote the National Gallery of Art.

Columbia bought the garden outright in 1814, according to the Daily News, under an agreement with the state that the school would move its facilities there from Lower Manhattan. Instead, Columbia allowed it to deteriorate.

By the middle of the 19th century, the urban city had arrived on 59th Street and Fifth Avenue, making the land on the former garden was quite valuable. Columbia made money leasing it for residential development, but in the 1920s, “many of the 298 row houses in this once stylish neighborhood had deteriorated into an unseemly collection of boarding houses, nightclubs, and speakeasies on the northern boundary of New York’ s theater district,” wrote the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

The wrecking ball arrived in the early 1930s to make way for Rockefeller Center. Hosack himself passed away almost a century earlier; he had a stroke at age 66 after exhausting himself during the Great Fire of 1835, when a quarter of the city burned to the ground.

Today, a plaque commemorating Elgin Garden exists in this skyscraper mini-city, memorializing David Hosack as a “man of science,” “citizen of the world,” and the developer of a botanical garden “for the knowledge of plants.”

[Top image: From the Archives of The New York Botanical Garden, via Wikipedia; second image: NYPL; third image: Wikipedia; fourth image: Wikipedia; fifth image: Drawing of Elgin by Reinagle, frontispiece of Hosack’s Hortus Elginensis catalogue, via Wikipedia; sixth image: Tabea Hosier, Elgin Botanical Gardens, 1936, National Gallery of Art]

July 24, 2023

What’s on the menu at a Ladies’ Mile department store lunch room?

An astounding 20,000 people waited for the doors to open at the new Siegel-Cooper department store in September 1896.

This was the emporium New York City consumers were waiting for: 80 departments featured everything from the latest fashions to pets to pianos to bicycles. Merchandise was spread out over 15 acres of selling space in a massive building on Sixth Avenue between 18th and 19th Streets.

(Oddly, the above illustration of the store doesn’t show the Sixth Avenue El, which had a special exit at 18th Street that led directly inside the building.)

But shopping can be exhausting, and even with the 20th century on the horizon, there were still few restaurants within the Ladies’ Mile shopping district where it was socially acceptable for a woman or group of women to grab a bite. (This is the Gilded Age, after all, and unescorted ladies weren’t supposed to dine on their own.)

Luckily, Siegel-Cooper had its customers covered. Among the many restaurants at the store was a “lunch room” for “quick light luncheons” geared for the female palate.

So what, exactly, constituted a light lunch? Based on the 1901 menu, that meant coffee, tea, “pure Jersey milk,” and buttermilk, for starters. And a “dairy dishes” category with very un-fancy offerings like oatmeal and (boiled) rice.

Scroll the menu more, and the items become more appealing. Stewed prunes don’t necessarily sound very appetizing, but tea biscuits and Parker House rolls make the cut.

And Fleischmann’s Hot Rolls! Fleischmann’s Vienna Bakery was on Broadway and 10th Street at the time, on the other side of Ladies’ Mile. Not only was it a fashionable place to buy baked goods, but the bakery was the first to come up with the idea of a “breadline” where hungry New Yorkers could queue up at night for free bread and coffee.

Pastry and pies? This is the good stuff. The variety of pies is quite impressive. The sandwiches, too, look appetizing. Except for the lettuce sandwich—doesn’t seem very filling.

The rest of the menu features soups, stews, cheese, and ice cream. Columbian ice cream—this I’ve never heard of. Tortoni, on the other hand, is rum-flavored.

[Menu: NYPL]

July 23, 2023

The freed slave who ran a famous 19th century roadhouse on today’s Second Avenue

Imagine New York in the 1810s: the population almost topped 100,000, City Hall had just been completed, and the northern reaches of the booming young city now extended past Canal Street.

And though slavery wouldn’t be illegal in New York State until 1827, New York City had passed legislation in 1799 that gradually abolished the practice and granted freedom to many enslaved residents.

One of these formerly enslaved residents was Cato Alexander, who was born in the city in 1780, according to a 2015 article in Eater by David Wondrich. Another account has it that Cato was born enslaved in South Carolina, bought his freedom, and then came to Gotham.

Though his origins are unclear, at some point after 1800, Alexander was a free man in New York City.

“Broad-shouldered, sturdy, and about 5 feet 8 inches in height,” according to a 1902 recollection by a writer in the Sun, Alexander worked as a chef at inns and hotels before opening his own roadhouse four miles outside the main city east of the Boston Post Road—today’s Second Avenue and 54th Street (top illustration).

Though a busy corner of Turtle Bay now, in the early 1800s this spot was the hinterlands; one of the nearest houses was the Beekman mansion, at today’s 50th Street beside the East River. The tavern was also located close to the shot tower (above illustration) at 53rd Street and the East River.

“The location was a shrewd one,” wrote Wondrich. “Cato’s Tavern was a ten-minute gallop out of New York City, then occupying just the southern tip of Manhattan, and it soon became the natural resort of all the city’s fast young men.”

“They would race their carriages up there, drink his famous gin cocktails, brandy juleps and punches, eat his famous game and curried oysters, and then race on back (sometimes with disastrous results).”

Cato’s was also near a wooden bridge known as the “kissing bridge” in pre-Civil War New York, seen in the illustration above—it offers a sense of just how bucolic the area was at the time.

Stage Coach and Tavern Days, published in 1900, recalled that Cato’s had a separate ballroom for dancing, “which would let thirty couple swing widely in energetic reels and quadrilles,” wrote author Alice Morse Earle. “When Christmas sleighing set in, the Knickerbocker braves and belles drove out there to dance; and there was always sleighing at Christmas in old New York—all octogenarians will tell you so.”

Though Alexander faced bigotry and racism from some rowdy customers, according to Wondrich, he was by many accounts highly respected, his tavern popular in a town with plenty of taverns and roadhouses at the outer limits of the city. (Below, a tavern on Broadway near Canal Street in 1812)

New Yorkers also raved about his talents with drinks. Irish comedian Tyrone Power (an ancestor of the American actor by the same name) stated that “Cato is a great man, foremost amongst cullers of mint, whether julep or hail-storm, second to no man as a compounder of cock-tail, and such a hand at gin-sling,” according to revolutionarywarjournal.com.

Cato’s continued to operate into the 1840s. By then, the urban city would have begun creeping up to Turtle Bay, marking the beginning of the end of the country roads and trotting lanes that brought sportsmen and travelers to his now-famous establishment. (Below, Second Avenue at 54th Street today.)

Alexander himself was also falling into debt. “He was always polite, kind-hearted, and obliging—too obliging sometimes for his own interest, for some of his customers borrowed considerable sums of money from him and forgot to refund,” wrote historian Benson Lossing, as quoted by the Sun.

He closed his tavern in the 1840s, tried his hand at operating a saloon on Broadway, and ultimately “died in poverty in 1858, aged 77,” wrote Wondrich.

[First, second, third, and fourth images: NYPL]

July 17, 2023

Sun-struck and recovering in the hospital in 19th century New York

Today, we call it heatstroke, hyperthermia, or heat exhaustion. But in the sweltering summertime of 19th century New York City, having a dangerously high body temperature was described as being “sun-struck” or suffering from “heat prostration.”

As this 1892 illustration of men recovering from the condition at the (long defunct) Centre Street Hospital shows, heat prostration was serious. Newspapers regularly listed the names and addresses of New Yorkers who were stricken during heat waves, or the “heated term,” as summer was called.

It looks like treatment involved wrapping a patient’s head with what I imagine to be an ice-packed or ice water towel. The man on the left is pouring something in a glass—ideally water for one of these dehydrated patients.

[Image: NYPL]

An 1850s red schoolhouse hiding in the middle of the Flower District

Imagine being a school-age kid in the New York City of the 1850s. If you were wealthy, your education would be in the hands of private tutors. When you became older, private academies or finishing schools completed your education. You may have even gone to college, perhaps, if you were male.

If you were not rich, you could attend a local free school (or one of the “colored schools” set aside for African American children in the segregated city) until you were old enough to pursue a trade or profession.

Of course, you might not go to school at all—even a minimal amount of schooling was not compulsory until the state passed a law in 1874.

But if getting a basic education was your goal, 1853 would have been a pivotal year. That’s when the New York City Board of Education merged with an older school association called the Public School Society. The invigorated Board began replacing outdated public school buildings with modern facilities to better serve the children of the booming city, whose population was hovering around 600,000.

One of these new schoolhouses still survives. Appropriately painted red and long since empty of students, it sits on the commercial stretch of West 28th Street between Sixth and Seventh Avenues, one of the last vestiges of the Flower District (top photo).

As buildings go, it’s quite a beauty. “One of the three oldest public school buildings in Manhattan, its Italianate design is characteristic of the period, with a symmetrical facade featuring a slightly projecting central section with shallow pediment,” noted the Historic Districts Council of what was called School 48 in Ward 20.

What would it have been like to attend this school on wide-open, almost bucolic West 28th Street in the 1850s? The illustration above (undated, but likely produced soon after the school opened) helps us imagine it.

Newspaper archives fill in the blanks. The New York Times covered the opening ceremonies on January 30, 1856. It was a day heavy with city dignitaries and Ward 20 officials, but the Times took note of the grounds and facilities as well: a playground, library room, teachers’ reception room, and a couple of rooms “for the janitor’s family.”

A girls’ department contained eight classrooms; the boys’ department had six, all of which had bookcases and closets. The classrooms were lit by gas. “A full corps of teachers” was tasked with educating about 750 students. The “beautiful building,” as the Times deemed it, cost $55,000 to build.

Graduation was held every year and even made it into the newspapers. To help wounded Civil War soldiers, schoolkids helped raise funds and donated it to the Ladies’ Home for Sick and Wounded Soldiers on Lexington Avenue and East 51st Street.

In the 1880s, Ward School 48 became Grammar School 48, an all-girls public school in the much more populated Chelsea neighborhood.

The Sixth Avenue corner of the block became home to an elevated train station, lending a rougher edge to the area. (The third photo was taken from the el station; the school can be seen on the left.)

After the turn of the 20th century, Grammar School 48 no longer served as a school, yet the lovely schoolhouse remained mostly intact and untouched (fourth photo, from 1940).

Today, flower companies occupy the converted commercial spaces on the ground floor. Between the truck traffic and the honking of horns, it’s not hard to imagine the school when it rang with the shouts and laughter of young children.

[Second image: NYPL; third image: MCNY F2013.126.19; fourth image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services]

July 16, 2023

The color and drama at a beachside Coney Island fruit stand

When social realist artist William Glackens visited Coney Island in the late 1890s, he had a bounty of kaleidoscopic scenes he could have immortalized in paint: the double-dip chutes of Steeplechase Park, the aquatic animals at Sea Lion Park, or the mass of humanity crowding the boardwalk and bathing pavilions.

But what captured his interest and imagination? A small wooden fruit stand perched on the sand.

It’s a curious choice out of all the attractions at Sodom by the Sea, as Coney was known in its golden era. But Glackens’ “Fruit Stand, Coney Island” manages to draw out much more emotion and drama than seen at first glance.

The bright yellow bananas and red, white, and blue American flags are blasts of color under the white-gray storm clouds looming over the beach. Individual vignettes of the people at the stand tell their own stories: children dip their toes in the water, older girls adjust their appearance, a mother looks down at the baby she cradles. Each vignette represents a different stage of life, particularly women’s lives.

The American flags tell us it might be the Fourth of July. Coney Island would have been packed with thousands of revelers—mostly working-class day trippers who came on ferries and trains with dimes in their pockets to pursue the pleasures, and vices, of Coney’s seaside attractions.

There’s an Old Masters feel to the painting, which may not be accidental. With Robert Henri in 1895, Glackens “made the pilgrimage to Paris, where he soaked up the improvisational brushwork of the French Impressionists as well as the brooding palate of Old Master paintings he saw on a bike trip through the Dutch countryside,” stated a 2007 New York Newsday article on Glackens, above in a 1908 self-portrait.

The influence of his trip to Europe likely rubbed off on the young artist, who was just 28 at the time he painted the fruit stand. The more you look into the painting, the more you see.

[NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale; Wikipedia]

July 10, 2023

The faded remains of a Brooklyn shoe factory

Obscured under a fire escape, it’s not easy to see. But squint hard in front of the four-story, 19th century brick walkup at 74 Greenpoint Avenue, and you’ll make out the faded lettering that marks this address as the one-time home of Walsh’s Shoe Factory.

It’s a phantom sign from perhaps the early decades of the 20th century—when the new borough of Brooklyn was a manufacturing powerhouse. That was especially true in Greenpoint, home of breweries and shipyards, of the Astral Oil Works and countless machine shops.

The faded letters are all that remain of the factory, and information about who Walsh was and when the factory shut its doors is hard to come by.

“In the 1879/1880 Lains Directory, several Walshes are listed as shoemakers, working at 74 Greenpoint Ave and living at 106 India Street (Alvin S. Walsh, Charles A. R. Walsh, Edward Walsh Jr., Everett B. Walsh),” notes the Instagram site Gethookedbrooklyn, in a 2021 post. Which Walsh brother started the factory, if any, isn’t known.

The sign is now a ghost, but 74 Greenpoint Avenue is a hot property; the building was recently renovated as a 13-unit rental. In the small space where factory workers once sewed, assembled, and shipped shoes, renters can now enjoy a two-bedroom unit for $4000 a month, per Streeteasy.

Where tenement dwellers slept during brutal summer heat waves

At the turn of the last century, two out of every three New Yorkers lived in a tenement. Day-to-day life inside most of these overcrowded, shoddily constructed buildings meant navigating dark hallways, communal bathrooms, trash-strewn backyards, and airless rooms.

But perhaps the worst of all was trying to sleep inside a tenement in the summer, when a heat wave could turn interior rooms lacking ventilation into ovens reaching 120 degrees.

Getting a good night’s rest indoors was virtually impossible during scorching days in July and August. New Yorkers with money and means fled the city, while the poor and working class stayed behind.

During the day, city officials gave away blocks of ice; public baths extended their usual hours. But after dark, options were limited. The only recourse many tenement dwellers had was to leave their stifling flats and find another place to bed down—sometimes with tragic results.

One sleep solution was to take a blanket and pillow to the tenement roof. Under the stars six stories in the air, it was possible to catch a breeze cool enough to help you nod off. The danger, unfortunately, was rolling off the roof to the pavement below.

Newspaper headlines every summer told tragic stories. “Rolled Off Roof and Was Killed” read one article from the July 1, 1901 edition of The New York Times. “John Terrell, living at 23 Duane Street, fell from the roof of the four-story building at 104 Park Row yesterday and was instantly killed. Terrell went on the roof on account of the heat, fell asleep, and rolled to his death.”

Dragging a mattress through an open window to the fire escape was another option. But again, sleepers risked falling off. “Eleven-year-old Dennis Brophy, of 57 Kent Avenue, is in a dying condition at Eastern District Hospital as a result of falling 30 feet from a fire escape to the ground,” wrote Brooklyn’s Standard Union on July 11, 1912. “”His mother placed him on the landing last night to get some air.”

A safer place to sleep would be a park. Though it was illegal to sleep in a public space at night, the law was eventually lifted at all city parks during heat emergencies to help sleep-deprived New Yorkers survive. (Below, Battery Park around 1910)

On August 12, 1922, six thousand people slept in Central Park, with the largest crowds beside the East Drive close to 86th Street—perhaps residents temporarily fleeing the tenement districts of Yorkville.

“There were hundreds of babies sleeping in their carriages, while the parents lay on the grass nearby, many of them with newspapers under them and with coats or shawls for pillows,” the New York Times reported. Extra police were on hand all night to protect the sleepers.

The sands of Coney Island were also crowded after sundown with New Yorkers seeking cool air and a bit of peace, as this photo above shows. On July 3, 1911, five thousand people slept on the beach at Coney, guarded by 25 extra cops to make sure “no thieves could rob the sleepers,” the Times wrote.

Where else could a tenement dweller cool off enough to catch some shuteye? One of the many piers that lined the East and Hudson Rivers.

This group of city residents at an unidentified East Side pier are trying to hold out. The two small kids on the right with blankets beneath them, however, have already drifted off to dreamland.

[Top image: NYPL; second image: New York Times; third image: Bettmann/CORBIS; fourth image: Bain Collection/LOC; fifth image: Getty Images; sixth image: Bain Collection/LOC]

July 5, 2023

Join a time-traveling walking tour of Manhattan’s most beautiful avenue!

Imagine Riverside Drive in its Gilded Age heyday: This winding avenue that follows the curves of Riverside Park was home to dozens of spectacular free-standing mansions and Beaux-Arts row houses.

Hudson River views, private carriage roads, and inspiring monuments made the Drive an optimal place for artists, actors, characters, and members of the city’s “millionaire colony” to settle.

This month, join Ephemeral New York and the New York Adventure Club on a walking tour that explores what life was like on Riverside Drive in the late 19th and early 20th century.

This relaxing, breezy tour starts at 83rd Street and ends at 108th Street. In between, we’ll walk up Riverside and delve into the Drive’s deep and storied history. The tours will take a look at the mansions and monuments that still survive as well as the incredible houses lost to the wrecking ball.

Tickets remain for the Riverside Drive tour for Sunday, July 9; tickets can be purchased here.

Tickets for Sunday, July 23 can be bought here. All are welcome! The tour has been a wonderful opportunity to meet Ephemeral readers and New York City history lovers. So far this season we’ve enjoyed great weather and refreshing breezes. I hope to see a great turnout!

[Top image: New York Adventure Club; second and third images: MCNY]