Esther Crain's Blog, page 29

August 28, 2023

A rare vintage wooden phone booth inside a fabled Brooklyn tavern

They used to be everywhere: restaurants and bars, drugstores and soda fountains, libraries, private clubs, schools, and hotel lobbies. But the wood phone booth with a hinged door that closes like an accordion has almost totally vanished from the cityscape.

These relics of 20th century New York City, with their secretive air and noir-ish feel, are dwindling fast. So it’s quite a thrill to find one by accident inside—where else?—an old-school Irish saloon where generations of Brooklynites gathered to drink their troubles away.

The phone booth is in the back room of Farrell’s, opened in 1933 (the year Prohibition was lifted) on Prospect Park West and 16th Street. The phone inside it no longer works; the booth is used to store cleaning products.

But it’s still there, a totem of a pre-cell phone era that forced you to engage with the people around you, none of whom were stealing frequent glances at a handheld device.

Farrell’s earned literary cred when Pete Hamill wrote about this neighborhood bar that his father disappeared into while Hamill was growing up on Seventh Avenue between 11th and 12th Streets.

“The place was always packed, the men three deep at the long polished wooden bar, served by two bartenders in starched white shirts and neat ties,” Hamill wrote in his 1994 memoir, A Drinking Life. “At that bar, where the men made jokes, drank beer and whiskey, placed bets on horses, and put cigarettes out on the tile floors, I felt at home. I was, after all, Billy Hamill’s son.”

Besides its wood phone booth, Farrell’s has other remnants that give it its wonderful time warp vibe. First, there’s the lovely ceiling, with light fixtures almost as old as the establishment itself.

Also, Farrell’s has one of the most glorious neon signs in all of Gotham. A storm years ago knocked an older sign down; now it hangs inside.

A new neon sign, however, is proudly affixed to the building, beckoning drinkers and fans of atmospheric taverns with dimmed lights and wood bars.

Tales of a hidden Brooklyn lane with a row of delightfully unusual 1870s wood houses

The city of Brooklyn came of age in the 19th century, and its houses across this booming metropolis reflect the prevailing design styles of the 1800s—from Federal-style homes with dormer windows to brownstone rows with Italianate and Romanesque Revival touches.

But sometimes you come across a stretch of unusually splendid residences that defy categorization and make you feel like you’ve stepped in an architectural time machine.

That’s what happened when I turned a leafy corner in Park Slope and found myself facing six brightly painted attached houses—each with tall parlor floor windows, fancifully painted cornices, and wide columned front porches that seem more Charleston than the City of Churches.

These country-like houses are on Webster Place, a one-block lane hidden inside 16th Street and Prospect Place and Sixth and Seventh Avenues. Shrouded by billowy tree tops and beautifully symmetric, they’re remnants of a post-Civil War building frenzy that remade many of the rural-ish neighborhoods collectively known as South Brooklyn into sought-after residential enclaves.

The homes are treasures in modern-day Park Slope—a unique blend of Queen Anne style because of the porches and wood trim, as well as Classical thanks to the wood columns. But the story of Webster Place and these six houses also offers a glimpse into what life was like in the rapidly urbanizing Brooklyn of the late 19th and early 20th century.

Numbers 21-31 Webster Place were likely built in the 1870s. Notices in Brooklyn newspapers announcing the sale of land lots on the tiny street began appearing in the late 1860s.

The name of the street is a mystery—why Webster? It could have been the name of a developer; perhaps it was in honor of well-respected New England statesman Daniel Webster, whose 1850 death was commemorated in New York by the closing of businesses on the day of his funeral.

In any case, at about the same time the houses (above, in 1940) were being planned and constructed, Webster Place was joining the cityscape. The secluded lane was paved and graded in the late 1860s. In 1871, the Brooklyn Common Council passed an ordinance that put gas street lamps on Webster Place. A year later, the street was officially opened.

Bits of information on the continuing development of the street emerged from newspaper archives. In the 1880s and 1890s, a grocery store popped up on the corner at 16th Street. Houses traded hands; the going price was around $3000.

But a 1943 Brooklyn Daily Eagle column on the remembrances of the borough’s “old timers” turned up some details that fill in the blanks of daily life on this slender lane at the turn of the century.

“Yes, Webster Place was a fine and clean little street with shade trees on both sides,” recalls a man named George Chevalier, who also mentioned the grocery store and a feed store on the block.

Chevalier remembered Webster Street neighbors who “had a team of billy goats and a patrol wagon and gave us a ride in it. Boy, how us kids did enjoy it!” The owner of the grocery store “would leave his horse sleigh on the sidewalk in front of the store and we would play in it, and I used to go for a ride with him when he would be delivering orders in the neighborhood.”

Another old-timer said his family has lived at 22 Webster Place (across the street from the splendid row of houses) since 1878. “I still remember the white houses with their green shutters and the tall trees lining both sides of the street, forming an arch over the roadway.”

This Webster Street resident recalled the families who lived on the block when he did; he listed a mix of English, Irish, and German last names. He also mentioned that the street was paved with cobblestones, “for I was one of those who swept them off every morning.”

Around the corner was a dairy that offered fresh milk from grazing cows. He further noted the nightly occurrence of “the lamplighter coming along with his ladder and taper to light the gas lamps.”

The cows are long gone, the lamplighter departed for good, and I doubt very much that any of the residents of 21-31 Webster Place get around by horse-drawn sleigh.

But these spectacular houses—with their welcoming stoops and porches, now slightly modified and not always matching their neighbors—reflect the sensibilities of 19th century Brooklyn as the city transitioned from rural county to urban metropolis, and then a borough of the city of New York.

Sometimes they even come up on the real estate listings. Number 23 was for rent earlier this year; take a look at the gorgeous interior shots that allow a peek into the backyard.

[Fourth photo: NYC Department of Records & Information Services]

August 24, 2023

Upcoming talks, tours, and a summer-themed podcast episode with Ephemeral New York!

I’m pleased to let everyone know about some Ephemeral New York events happening now through the next few months. All are open and accessible to the public and will add some Gilded Age enjoyment to your late summer and early fall weeks!

First, September tour dates for Ephemeral New York’s popular Gilded Age Riverside Drive Walking Tour are on the calendar! Tours are scheduled for Sunday, September 10 and Sunday, September 24; they are done in conjunction with the New York Adventure Club.

Sign up via the link for each date! October tours are set for October 15 and October 29; check back for sign up links soon.

Each tour starts at 1 p.m. at 83rd Street and Riverside Drive and ends at 108th Street two hours later. We’ll stroll the gentle curves of the avenue and delve into the history of this beautiful drive born in the Gilded Age, which rivaled Fifth Avenue as the city’s millionaire row.

We’ll explore the mansions that remain, the people who lived there, the houses lost to the wrecking ball, and the stories told by spectacular monuments.

Next up, ever wonder what New Yorkers who couldn’t escape to Newport or Long Branch did to survive the dog days of summer?

If you haven’t listened to it already, check out Ephemeral New York’s guest appearance on the fun and insightful Gilded Gentleman Podcast in an episode titled “In the Good Old Summertime.”

In this episode, The Gilded Gentleman (aka host Carl Raymond) and I take a deep dive into how regular New Yorkers stayed cool and enjoyed the pleasures of the “heated term,” otherwise known as the summer season, in Gilded Age Gotham. Carl and I explored the life and work of Gilded Age servants in an earlier episode from 2022, and this recent summer-themed show was a delight to be part of.

Finally, on October 5, I’ll be giving a Gilded-Age themed talk at the beautiful Old Westbury Gardens on Long Island. Old Westbury Gardens was built in 1906 as the home of financier John S. Phipps and his family. This estate has been magnificently restored on about 200 acres with lovely gardens surrounding a magnificent mansion. Check back for more information soon!

[Top image: MCNY, 26908.1F; second image: MCNY, F2011.33.73; third image: NYPL Digital Collections; fourth image: William Glackens]

August 21, 2023

The glow of the city on a Depression-era summer night

Martin Lewis is the artist behind this film noir-like masterpiece of light and darkness, a drypoint etching simply titled “Glow of the City” and completed in 1929.

It’s a study in contrasts: the dark church steeple of 19th century New York against the illumination of a 20th century skyscraper—the Chanin Building, which would have recently opened on East 42nd Street. This cathedral of commerce radiates light and power amid the everyday dreariness of tenement backyards and laundry on clotheslines.

And what about the woman in the foreground? She may be clad in an ordinary top and skirt, but she’s styled like an Art Deco goddess. She’s looking at the skyscraper, her Art Deco counterpart casting a glow over her world.

More Martin Lewis works of Depression-era New York City can be seen here.

[Smithsonian American Art Museum]

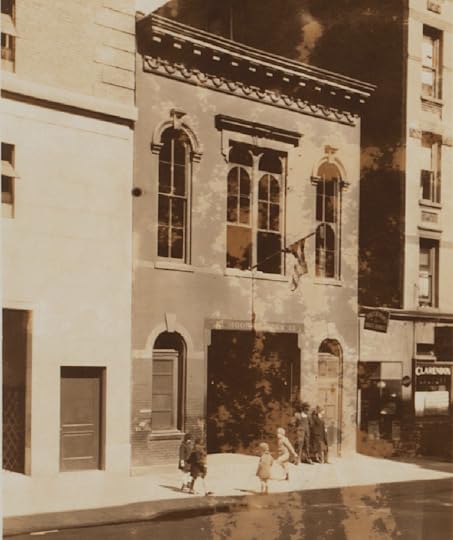

From 1860s firehouse to Andy Warhol’s 1960s studio, the many lives of a Yorkville building

Tall apartment towers, low-rise tenements, a multi-floor parking garage—East 87th Street between Lexington and Third Avenues has them all. It’s an ordinary block in a part-residential, part-commercial stretch of Manhattan.

But hiding on the north side of the street is something special: a two-story carriage house–like structure with elegant arched windows and slender doorways.

Under a coat of gray paint with black trim, 159 East 87th Street seems dwarfed by the modern cityscape. But this little holdout has a fascinating backstory—first as a Civil War-era firehouse, then as a short-lived studio of Pop Art creator Andy Warhol a century later.

The story of the firehouse begins in 1868, three years after New York’s first professional fire department made its debut in 1865. Before then, city firefighters were volunteers with a rough reputation; sometimes they were more interested in fighting each other than putting out the many blazes that plagued Gotham from the colonial era to the mid-1800s.

The same year the fire department formed, a volunteer company based on East 87th Street was reorganized as the Suburban Hook & Ladder Company No. 13. A “suburban” fire company operated more loosely than the full-time units, and the firefighters who belonged to these companies were paid less, states nyfd.com. (Below, the firehouse in 1929)

But the word also gives an idea of what East 87th Street was like in the 1860s: a sparsely populated section of the city dotted with walkup residences and riverfront estates of the wealthy. This was Yorkville, but not yet the Yorkville of tenements, factories, and German immigrants—who would transform the area at the turn of the century.

In 1868, the new firehouse at 159 East 87th Street was completed. The firemen (and their horse-pulled wagons) moved in. Over the next several decades, newspapers would contain numerous tragic stories of the blazes they were summoned to fight when local residents pulled call boxes on street corners.

On the afternoon of June 11, 1906, a terrible fire broke out inside a tenement at 209 East 97th Street. “The men of Engine Company No. 36 and Hook and Ladder Company No. 13 were at work on a ladder directly opposite blazing windows,” wrote the New York Times a day later. “Suddenly flames shot out to the ladder where the firemen were at work.”

Two firemen on the fourth floor, including Victor Cahill of Company No. 13, “were knocked from the ladder, and the crowd saw their bodies turn in the air and fall to the pavement below.” Both men were given last rites and were not expected to survive, per the Times. A woman and three kids also perished.

Company No. 13 remained in the firehouse until the early 1960s, when a roomier, more modern firehouse was built for them on East 85th Street. (Above photo, the firehouse in 1940)

In 1962, the firehouse was vacant—and an emerging artist who had been living with his mother nearby on Lexington Avenue decided to make it his studio. That artist was Andy Warhol, whose Campbell’s Soup Can paintings were now on exhibit. A 2016 article from Artnet News sums up the story:

“The fire house only cost $150 a month, but it was a wreck, with leaks in the roof and holes in the floors, but it was better than trying to make serious paintings in the wood-paneled living-room of his Victorian townhouse, as he’d done for the previous couple of years,” said Artnet News contributor Blake Gopnik in the 2016 article.

Warhol moved in on January 1, 1963, according to Artnet. Five months later, his lease was terminated—but his life as a celebrity artist and trendsetter was just beginning.

In 1965, the 95-year-old firehouse was bought by art dealer Daniel Wildenstein, who transformed it into a sculpture garden with dozens of works for sale by artists from Rodin to Canova.

A New York Times article noted that “not far from where the firemen used to slide down the brass pole hangs a painting by Vuillard that heated up one collector so much that he paid $200,000 for it.” (The fifth photo shows the Firehouse in its sculpture garden era.)

The firehouse remained in the Wildenstein family until 2016, when it was put on the market. (The sixth photo shows the firehouse in 2012, when it was still painted red.) The realtors handling the sale described the building as a “blank canvas” that could be used as a residence, commercial space, or community or medical facility, reported DNAinfo.

That same year, the 5,000-square-foot building sold for $9.9 million, according to The Real Deal. I can’t help but wonder what the firemen of Suburban Hook & Ladder Company No. 13 would think of the astounding price of their firehouse—a modest and functional space built that enabled them to respond to neighborhood fires and save lives.

[Third image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services; fourth image: NYPL Digital Collections; fifth image: Wikipedia; sixth image: New York Times]

August 14, 2023

The colonial-dressed grotesques on an Upper Manhattan apartment house

New York City is rich with grotesques and gargoyles on commercial and residential buildings. Some are scary, others silly or cheeky. Many are shrouded in mystery, the symbolism and meaning intended by the builder lost to the ages.

But these two fellows guarding the entrance to an Upper Manhattan apartment house are the first I’ve ever seen who look like they’re dressed in colonial-era wigs and clothing.

What’s the significance behind their circa-1770 outfits? I think it has to do with the location of the apartment building they adorn, and its proximity to a colonial mansion that played a role in the Revolutionary War.

The building is 432 West 160th Street. Officially, this address is in Washington Heights. But it’s also adjacent to Jumel Terrace, a historic district of 50 Queen Anne and Romanesque Revival row houses built between 1890 and 1902.

The center of Jumel Terrace is the Morris-Jumel Mansion, built around 1765 as a summer home for Roger Morris, a British army officer, and his family, according to the mansion’s website. (The mansion is now a historic site and museum, below).

At the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, the Morris family fled their Georgian mansion and went to London, as many other Loyalists in New York City did. George Washington and the Continental Army then took over the empty house for several weeks in 1776 after the bruising Battle of Brooklyn.

Could these two grotesques in their colonial garb represent the Revolutionary War figures who occupied the house in the early years of the fight for independence?

I’d like to think the architects or developers who built 432 West 160th Street (above) 150 years or so later are giving a subtle nod to the Morris-Jumel Mansion’s place in American history.

[Third photo: Wikipedia]

The once-delightful, now decayed 1892 terra cotta house under the Queensboro Bridge

It’s a startling sight amid a mostly desolate, formerly industrial patch of the Long Island City riverfront in the shadow of the Queensboro Bridge.

At 42-10 Vernon Boulevard on a lawn leading to the East River sits a fairy-tale brick and terra cotta relic: a two-story confection of stepped gables, chimneys styled with spirals, round red roof tiles, and panels carved with floral motifs and grotesque faces.

Considering the boarded-up windows and barbed-wire fence the building crumbles behind, you might disregard this unusual remnant as a hopeless wreck.

But before you do, get to know the story behind the isolation and deterioration of this eccentric holdout—a former jewel of an office headquarters colloquially known today as the Terra Cotta House.

The story of the Terra Cotta House aligns with the story of terra cotta’s popularity in New York City. Amid a Gilded Age construction boom in the 1870s and 1880s, this clay that could be shaped into ornamental forms and then fired in a kiln became an in-demand building material.

Terra cotta was versatile, cheaper than stone, and fireproof. To meet the demand for it, a company called the New York Architectural Terra-Cotta Works opened a manufacturing complex in the rapidly industrializing, recently incorporated municipality of Long Island City.

“Established in 1886, the company was the only major terra cotta manufacturer in New York City, and, when completed, its facilities were the largest in the country for architectural terra cotta,” noted the Historic Districts Council.

The terra cotta wasn’t totally native to Queens, alas. The clay came from New Jersey, though the molding and carving and firing in kilns was done by skilled artisans in the facility.

The original complex burned down three months later. But the company rebuilt quickly, moving its growing manufacturing operation to a new site on the East River waterfront, according to the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) report published in 1982.

“Situated in what was then rural Long Island City, Queens, the great complex had crucial river access to the skyscraper explosion going on across the way in Manhattan,” a 1987 New York Times article reported.

In 1892, the leaders of the New York Architectural Terra-Cotta Works decided to construct a new office headquarters on the site of its manufacturing plant. The two-story building—today’s Terra Cotta House—was to be a showpiece for the company. (Fourth photo, with the Queensboro Bridge still under construction)

“Placed at the easternmost end of a nearly two-acre site with a frontage of over 200 feet on the East River, the headquarters building stood against a backdrop of the company’s entire manufacturing, warehouse, and shipping operation,” stated the LPC report.

With its fanciful headquarters and manufacturing operation at one site, the company made its mark of Gotham’s cityscape. It produced terra cotta ornamentation for Carnegie Hall, the Ansonia Hotel, the Montauk Club in Park Slope, and scores of other buildings, according to the New York Times.

“By 1915, the company was the fourth largest employer in Long Island City,” noted the LPC report. The 1920s saw a boom—and then bankruptcy in 1928. A new company formed and took over the space, but by the 1940s, the manufacturing site was empty.

The Terra Cotta House was still in use as a construction company office until 1968, after which it was sold to Citibank. In 1976, the manufacturing operation was bulldozed.

“Today only the New York Architectural Terra-Cotta Works building survives as a symbol of the material and industry which transformed the construction profession in the late 19th century,” wrote the LPC.

That was in 1982, the year the building was landmarked. In the ensuing 42 years, the Terra Cotta House seems to have remained in a state of decay, its back to the buildings across the East River in Manhattan it may have helped build a century ago.

The future of this delightful monument to Long Island City’s industrial past appears to be a mystery.

[Fourth photo: Greater Astoria Historical Society]

August 7, 2023

A painter depicts the moody early 20th century East River as a “landscape of industry”

For centuries, New York City made its fortunes from its riverfronts. But it’s been a long time since the waterways of Gotham were dominated by industrial use. In contemporary Manhattan, rivers are for pristine parks, not derricks, tugboats, and ship traffic.

Jonas Lie’s “Morning on the River” puts the gritty, smoky East River of old back into view. Lie was a Norwegian immigrant known for his Impressionist paintings of harbors and coastlines in the early 20th century.

In this 1912 depiction of the riverfront—a place bustling with energy but no human faces in view—Lie “captures the new American landscape of industry and technology,” states Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, which owns the painting.

“Jonas Lie’s dramatic portrayal juxtaposes the powerful bulk of the bridge with the brilliant morning light reflecting off the icy East River in a drama of humankind versus nature,” states the University of Rochester in a separate document that goes into greater detail. “The modern cityscape has replaced the untamed wilderness as a symbol of America’s progress.”

It’s a captivating, moody painting, and my eye is drawn to the orange glow in the center, perhaps a furnace burning coal or wood for industrial use or to keep the working men warm.

A tucked-away holdout house built before the Civil War hides on 73rd Street

It’s not a house with a famous pedigree—no Vanderbilts or Astors lived there. It wasn’t the site of a historical event; it didn’t witness a scandalous crime. Tucked away on a quiet Lenox Hill block, it doesn’t steal the spotlight from its converted carriage house neighbors.

What distinguishes the red brick beauty with the curvy cornice and spectacular original iron veranda at 171 East 73rd Street is its astounding longevity.

In an ever-changing Manhattan where row houses are renovated over and over to reflect current design styles—or bulldozed in favor of something taller and shinier—this set-back house still exists much as it did when it made its debut 163 years ago.

Number 171 got its start in 1860. At the time, the Metropolis of just over 800,000 residents was still recovering from the Panic of 1857; the dissolution of the nation was on the horizon. Streetcars pulled by horses plied muddy avenues, cage crinolines were all the rage in ladies’ fashion, and only part of Central Park had opened to the public.

But the urbanization of Manhattan was in full swing, and a row of six low-key brick houses for middle-income owners were constructed on the north side of 73rd Street between Lexington and Third Avenues, according to the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) report from 1980.

Building a row of houses on East 73rd Street at the time was ambitious. The street was far beyond the city center at the time, which hovered between Union Square and Madison Square. Transportation downtown wasn’t always reliable or comfortable.

But no shortage of developers were eager to build and sell. “In the early 1860s a number of streets on the Upper East Side were developed with modest row houses that were sold to lower-middle-class and working-class families,” states the LPC report. “These rows were among the earliest buildings on the Upper East Side and they predate the large scale development of the area.”

By the 1880s and 1890s, those row houses were under threat—thanks to the sudden construction of private carriage houses for the wealthy families now building massive mansions on upper Fifth Avenue.

“With the construction of each new carriage house, the remaining residential buildings became less and less desirable until only a very few remained,” states the LPC report. And now that an elevated railroad roared above Third Avenue day and night, the block—and the row houses still there—lost their middle-class appeal.

In the 1920s, however, number 171 got a reprieve from the wrecking ball. Architect Electus D. Litchfield (below) bought it and moved in with his wife and two children.

A descendent of an old Brooklyn family, Litchfield designed several buildings in New York. Urban renewal and city beautification were some of his interests; he was the architect behind Red Hook’s “slum clearance” in the 1930s and the construction of modern housing project in its place, according to his New York Times obituary.

Litchfield altered Number 171 (below, in 1940) somewhat. He added a vestibule and garden wall, states the LPC report. He also removed the original front stoop and turned the main entrance into a window. He lived the rest of his life here until his death in 1952.

Luckily, he didn’t touch the original iron veranda. It’s an architectural feature common to houses built in the middle of the 19th century, but few remain. “The finest feature of the building is the cast-iron veranda that shades the first floor,” per the LPC report. “Once a common sight in New York City, these verandas are now extremely rare.”

Squished between its carriage house neighbors, Number 171 is a stunner, one of just two surviving houses from the original six in the row. (The other is Number 175, an equally charming house but without the lovely iron veranda.)

According to real estate listings, the interior was “completely reimagined” in 2016. What does that mean? See for yourself with these interior photos. They showcase a modern urban home far from its modest, middle-class beginnings in the exurban wilds of pre-Civil War Manhattan.

[Fifth photo: Findagrave.com; sixth photo: New York City Department of Records & Information Services]

July 31, 2023

A dramatic view from 1916 of the cliffside mansions of Riverside Drive

What would it have been like to live on Riverside Drive in 1916? Based on this aerial image taken that year between about 73rd and 78th Streets, the Drive was all about man-made luxury set against natural incredible beauty.

High above the Hudson River is a spectacular chateau-like mansion taking up an entire block. This is the 86-room Schwab mansion, built in 1906 for steel magnate Charles Schwab. North of the Schwab mansion are dozens of Queen Anne and Beaux-Arts townhouses, separate homes joined together to form a palace—or a fortress.

But nothing ever stays the same in New York. Within a generation, the Riverside Drive born in the Gilded Age and meant to be the city’s new “millionaire colony” would mostly be torn down and replaced by the line of tall apartment buildings still standing today.

In the 1930s, the railroad tracks between Riverside Park and the Hudson River would be sunk underground. Landfill would double the park’s size, changing it from a pastoral English-style park with a bridle path to the kind of playground-packed accessible green space in favor today.

Today’s Riverside Drive is still dramatic and lovely. But this image shows us a moment in time in the early, more exclusive life of Riverside Drive—more than a century old and lost to the ages.

Learn more about the history of Riverside Drive by joining Ephemeral New York on a walking tour of the Drive! Space is still available for the tour on Sunday, August 6 and a second tour on Sunday, August 20.

[Image: Library of Congress]