Brendan Shea's Blog, page 23

July 11, 2024

The Writer’s Dilemma

What a successful writer is up against

I was talking with a friend at church the other day, and he did not operate in the writing space but offered to beta read for me, based on church writings he had critiqued, and I was delighted to find another reader to provide free and potentially helpful input.

When asked if I was published, I showed him my website on Amazon, and it is possible that he was impressed.

I then told him of my difficulties being a successful writer, particularly a self-published one, and will list them briefly in the below bullets:

A writer must have some competency with language, style, theme, grammar and technique, or no one will want to read their workThose who pen books must produce handsome efforts, utilizing good graphics, photos and illustrations, should they lack a traditional publishing house to support them, otherwise, their work will not be taken as seriouslyThe author must have a sense of their audience, so that they produce work that is interesting to them, but also to a fair number of others.The book must be marketed effectively, or no one will know it existsIf you’re a writer like me, and want to comment below on your struggles and concerns, please do so.

Why Be Normal?

Is there value in regular behavior is the question

I went camping this week, and on returning home was exhausted by the journey. This blog is very short. All I have to write is that my dreams can be fitful and bizarre, but this time, my dream was rational and not negative, per se.

I rejoiced that after a fun but somewhat stressful getaway, my nap was sweet and my thoughts not tied up in knots when I lay my head down and let the week go.

There’s a lot to be said for normal thoughts and dreams. Magic could be good, but the mundane can be reassuring.

I hope you can find normalcy when you want to; I found some here today.

July 6, 2024

In the Top 100 on Amazon for Best Sellers in Baseball Essays & Writings

Please view my book at #92 or pick up a copy!

Check out my new book…

White Fences Black Stars

A historical fiction on the Negro Baseball Leagues of old.

Three Black men in the early twentieth century struggle against racism and Jim Crow as they participate, to the best of their ability, in the sport they love. Join Negro League baseball players, Heath, Gooch and Wilkinson, as they triumph over adversity by sticking together through thick and thin, raise their families during a time of bigotry laced with victories and barnstorm their way across the country and around the world.

So I was reading a book called Black Diamond, about the so-called Negro Baseball Leagues of the 1800s and 1900s, I say so-called not because it was illegitimate by any means, but because we don’t use that word anymore. There were many stories and anecdotes about various African-American baseball players, telling of their situations with the plight of racism, the bane of segregation, and other difficulties. The stories were entertaining, but they were not very profound. What I mean is they didn’t plunge deeply into the personal lives of the men in the story. Perhaps they didn’t have adequate information. It occurred to me that I could pen a simple story about these complex and important people as fiction, and reference facts about them at the same time, calling it historical fiction.

I questioned myself as to whether I was the right person for the job since I am Caucasian, but as yet I do not know anyone who is both African-American and a writer, and someone who wanted to write this. I would certainly want to collaborate with someone fitting this description if I did. That way my work would be more authentic. I grew up in a predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhood in Berkeley decades ago, but that doesn’t make me African-American, so I am not entirely qualified. Nonetheless, I am delighted to embark on this journey, and if along the way there is a better way to author this book that means someone else would do some of the writing or would collaborate with me, I would welcome that, but I feel privileged and excited to write it myself! If I put a lot of effort into it I would like to still be connected to it, but the main thing is that it should be entertaining, informative and encouraging.

I am also excited that as I wrapped up the first draft of this book, Major League Baseball announced that Negro League statistics will now be included in the official, MLB record books. This is a coup and a wonderful thing, praise God!

-Brendan Shea , San Francisco Bay Area, 2024

Here’s a link to the book on Amazon.

Enjoy!

June 23, 2024

Getting Back Up

A Manual For Men (but the ladies can benefit too!)

I was doing well for several months but then was judgmental and stumbled. I also overdid something that upset the apple-cart, and in the end, I should have found a better way to cope.

I was angry, frustrated and depressed, so I fell off the wagon. But I’m pressing on to focus on Jesus, and not on my sin. Can I right my ship? Time will tell.

We are to fix our eyes on Jesus, the Author and Perfecter of our faith, who for the joy set before Him, endured the Cross, scorning its shame, and sat down at the Right Hand of the Father.

When men sin, dwelling on that sin is not the way to repentance; grieving the sin might be good, and there will be some consequences, but getting back on the horse is imperative.

As men, we are called to love our wives (and everyone). So what happens when we don’t know where to go with our feelings? We can’t always focus on our wives.

Sometimes friends can help, but if we can recenter our minds on God and also on work, we might be able to reset our paradigm back to the loving, gracious people we are called to be.

Men are called to lay down their lives for their wives. What does that mean? That means that sometimes we have to eat crow. Sometimes, we have to sacrifice our own agenda. Often, we have to swallow our pride and keep our thoughts and emotions to ourselves.

Sometimes we literally die. I think of John Lennon, when Mark David Chapman went to kill the singer songwriter, Lennon flung himself in front of his wife Yoko so she wouldn’t take any bullets.

Lennon died at age forty on October 8th, 1980. He was only forty years old. I remember the day by heart. Yoko is now ninety-one, and has had a long life on her own. Lennon was willing to give up his life for his best friend.

Jesus went further. He died for us when we were shouting, “Crucify Him! Crucify Him!” :-[

I realize all of this is not easy. Nor does knowing it mean I’ve mastered it, but this blog entry is a written attempt to get back on the horse.

I hope you stay in the saddle as well.

June 21, 2024

Dr. Funkentoes

Are you like me and have a set of frankentoes? My toes have been smashed more times than I care to remember, and I’m careful now to protect them.

As a result of all the egregious blows, my toes had terrible ingrown issues; the big digits that is. My awesome doctor Bui removed the issues, but I still had problems.

He then operated on my broken second right digit, and now the back and leg pain I had for years is gone!

But my wife was unhappy because my frankentoes had the funk; they were full of dark, dirty fungus.

We tried all kinds of remedies that failed:

But nothing worked.

Then Dr. Bui removed the big offending toenails and put me on Fluconazole for a year. The issue persisted. So he removed them again, and said to scrub them daily in the shower.

Now, they have grown back clean, and I scrub them with soap and water and a nylon brush in the shower, 6-7 times per week.

Battered as they are, they are still frankentoes, but are nearly grown back, and are 99% clean!

I’d say 100%, but I’m not sure if any dirt is lurking still.

If you have toe fungus, I highly recommend maintaining a clean lifestyle, removal of nails, and then scrubbing daily once the toes have healed.

Then you can put your best foot forward

June 19, 2024

Reblogged: Smithsonian

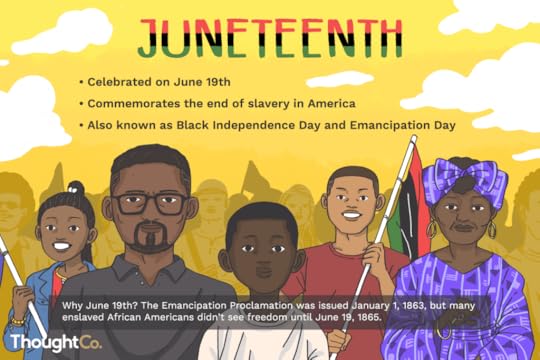

The Historical Legacy of Juneteenth

The Historical Legacy of Juneteenth

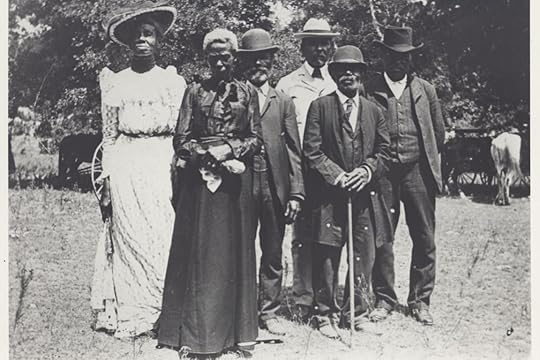

On “Freedom’s Eve,” or the eve of January 1, 1863, the first Watch Night services took place. On that night, enslaved and free African Americans gathered in churches and private homes all across the country awaiting news that the Emancipation Proclamation had taken effect. At the stroke of midnight, prayers were answered as all enslaved people in Confederate States were declared legally free. Union soldiers, many of whom were black, marched onto plantations and across cities in the south reading small copies of the Emancipation Proclamation spreading the news of freedom in Confederate States. Only through the Thirteenth Amendment did emancipation end slavery throughout the United States.

But not everyone in Confederate territory would immediately be free. Even though the Emancipation Proclamation was made effective in 1863, it could not be implemented in places still under Confederate control. As a result, in the westernmost Confederate state of Texas, enslaved people would not be free until much later. Freedom finally came on June 19, 1865, when some 2,000 Union troops arrived in Galveston Bay, Texas. The army announced that the more than 250,000 enslaved black people in the state, were free by executive decree. This day came to be known as “Juneteenth,” by the newly freed people in Texas.

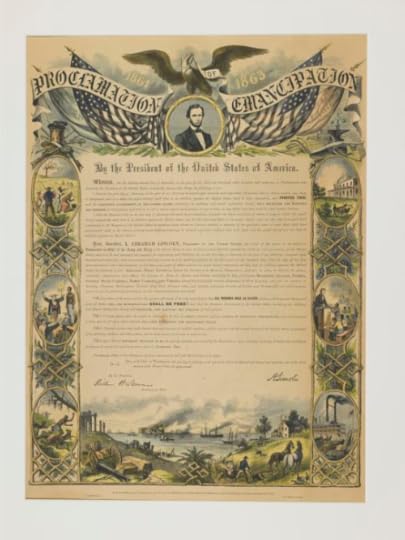

Publishers throughout the North responded to a demand for copies of Lincoln’s proclamation and produced numerous decorative versions, including this engraving by R. A. Dimmick in 1864.

Publishers throughout the North responded to a demand for copies of Lincoln’s proclamation and produced numerous decorative versions, including this engraving by R. A. Dimmick in 1864. The post-emancipation period known as Reconstruction (1865-1877) marked an era of great hope, uncertainty, and struggle for the nation as a whole. Formerly enslaved people immediately sought to reunify families, establish schools, run for political office, push radical legislation and even sue slaveholders for compensation. Given the 200+ years of enslavement, such changes were nothing short of amazing. Not even a generation out of slavery, African Americans were inspired and empowered to transform their lives and their country.

Juneteenth marks our country’s second independence day. Although it has long been celebrated in the African American community, this monumental event remains largely unknown to most Americans.

The historical legacy of Juneteenth shows the value of never giving up hope in uncertain times. The National Museum of African American History and Cultureis a community space where this spirit of hope lives on. A place where historical events like Juneteenth are shared and new stories with equal urgency are told.

June 12, 2024

New David Baldacci Book

If you haven’t yet heard about the new David Baldacci book, A Calamity of Souls, I suggest taking a look to see what you think.

Here is a short video, sharing what it is about.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=UPdXtr0ezTw#bottom-sheet

So, this song ROCKS…

June 2, 2024

What to know about Negro Leagues stats entering MLB record

Reblogged

What to know about Negro Leagues stats entering MLB record

What to know about Negro Leagues stats entering MLB recordMay 29th, 2024

Anthony Castrovince@castrovinceShare

Major League Baseball’s embrace of the Negro Leagues is now recognized in the record book, resulting in new-look leaderboards fronted in several prominent places by Hall of Famer Josh Gibson and an overdue appreciation of many other Black stars.

Following the 2020 announcement that seven different Negro Leagues from 1920-1948 would be recognized as Major Leagues, MLB announced Wednesday that it has followed the recommendations of the independent Negro League Statistical Review Committee in absorbing the available Negro Leagues numbers into the official historical record.

“We are proud that the official historical record now includes the players of the Negro Leagues,” Commissioner Rob Manfred said. “This initiative is focused on ensuring that future generations of fans have access to the statistics and milestones of all those who made the Negro Leagues possible. Their accomplishments on the field will be a gateway to broader learning about this triumph in American history and the path that led to Jackie Robinson’s 1947 Dodger debut.”

Gibson, the legendary catcher and power hitter who played for the Homestead Grays and Pittsburgh Crawfords, is now MLB’s all-time leader in batting average, slugging percentage and OPS and holds the all-time single-season records in each of those categories. Gibson is one of more than 2,300 Negro Leagues players — including three living players who played in the 1920-1948 era in Bill Greason, Ron Teasley and Hall of Famer Willie Mays — included in a newly integrated database at MLB.com that combines the Negro Leagues numbers with the existing data from the American League, National League and other Major Leagues from history.

“The Negro Leagues were a product of segregated America, created to give opportunity where opportunity did not exist,” said Negro Leagues expert and historian Larry Lester. “As Bart Giamatti, former Commissioner of Baseball, once said, ‘We must never lose sight of our history, insofar as it is ugly, never to repeat it, and insofar as it is glorious, to cherish it.’”

Negro Leagues stats enter record

• Everything to know as Negro Leagues stats join MLB record

• Gibson’s incredible talent transcends even his legend

• Here are the top changes to statistical leaderboards

• Stat changes for 8 Hall of Famers who got their start in Negro Leagues

• 10 hits added to Mays’ ledger, but HR total stays at 660

• Baseball’s record books are changing, and that’s nothing new

• Findings from Negro Leagues Statistical Review Committee

• Updated all-time MLB leaderboards: Hitting | Pitching

• Official MLB press release

• Complete Negro Leagues coverage

John Thorn, official MLB historian and chairman of the Negro Leagues Statistical Review Committee, said the new database can be understood “by realizing that stats are shorthand for stories, and that the story of the Negro Leagues is worthy of our study.”

To help fans with that study, here are answers to questions you might have about this historic and unusual (though not unprecedented) development.

What were the Negro Leagues?

Prior to the debut of Jackie Robinson with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, the American and National leagues were, like so much of society, segregated. Unable to pursue playing careers in those leagues, Black players formed leagues of their own, beginning in 1920 with the eight-team Negro National League, founded by Andrew “Rube” Foster.

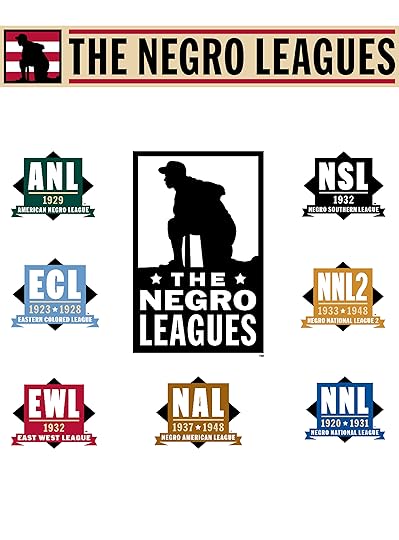

Over the next 30 years, a variety of Negro Leagues came and went. The Negro World Series was held from 1924 to 1927 (featuring the champions of the Negro National League against the champions of the Eastern Colored League) and again from 1942 to 1948 (featuring the champions of the second iteration of the Negro National League against the champions of the Negro American League).

All told, the Negro Leagues produced 37 eventual members of the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Robinson’s integration of MLB marked the beginning of the end for the Negro Leagues.

• History of the Negro Leagues

Why are the Negro Leagues being added to the historical record?

Essentially, to right a wrong. It certainly was not the fault of Black baseball stars such as Gibson, Cool Papa Bell and Oscar Charleston that they were forbidden from participating in the AL or NL, and recognizing the Negro Leagues as Major Leagues is in keeping with long-held beliefs that the quality of the segregation-era Negro Leagues circuits was comparable to the MLB product in that same time period.

“All of us who love baseball have long known that the Negro Leagues produced many of our game’s best players, innovations and triumphs against a backdrop of injustice,” Commissioner Manfred said at the time of the 2020 announcement. “We are now grateful to count the players of the Negro Leagues where they belong: as Major Leaguers within the official historical record.”

In recent decades, the tireless work of researchers combing through newspapers, scorebooks and microfiche led to the expanded availability of Negro League statistics (culminating most notably in the expansive database compiled by Seamheads) and made it viable to include these leagues in the historical record.

The legacy of ‘Cool Papa’ Bell

The legacy of ‘Cool Papa’ BellWhich Negro Leagues will be included in the official record?

There are seven, and they operated between 1920 and 1948. The reason for the starting point is that attempts to develop Negro Leagues prior to 1920 were ultimately unsuccessful and lacked a league structure. And 1948 was deemed to be a reasonable end point because it was the last year of the Negro National League and the segregated World Series. After that point, the Negro League teams and leagues that had endured were stripped of much of their talent.

You may have missed…The seven leagues are as follows:

• Negro National League (I) (1920–1931)

• Eastern Colored League (1923–1928)

• American Negro League (1929)

• East-West League (1932)

• Negro Southern League (1932)

• Negro National League (II) (1933–1948)

• Negro American League (1937–1948)

This first release of the MLB database also includes independent teams that formerly played within a Negro League and subsequently returned. The database includes not only these clubs’ won-lost records as independents, against league opponents, but also their players’ statistics.

Is this the first time leagues have been granted “Major League” status long after they ceased to exist?

No. In 1969, MLB’s Special Committee on Baseball Records determined which past professional leagues should be classified alongside the AL and NL as Major Leagues in the first publication of “The Baseball Encyclopedia.” At that time, the committee concluded that the American Association (1882-91), Union Association (1884), Players’ League (1890) and Federal League (1914-15) all qualified.

Not only did that committee not grant Major League status to the Negro Leagues, but the Negro Leagues weren’t even given consideration in the meetings. MLB’s 2020 decision reflected the evolved attitudes toward and respect for the Negro Leagues.

Why did it take so long to incorporate the Negro Leagues into the statistical record?

Once the 2020 decision was made to include the Negro Leagues, MLB and its official statistician, the Elias Sports Bureau, had to complete a review process of the Seamheads data, and MLB and Seamheads had thorough and detailed discussions over how the data would be utilized.

MLB built upon the Seamheads database with the help of Retrosheet, an organization that computerizes Major League games from prior to 1984, and a 16-member Negro Leagues Statistical Review Committee was formed to determine, among other things, what minimum standards would be put in place for Negro Leagues players to qualify for season or career leaderboards.

Complicating the process was the understandably scattershot nature of the Negro Leagues schedules, which we will cover in a sec.

Negro Leagues 100th Anniversary

Negro Leagues 100th AnniversaryWhat are the minimum standards for inclusion in leaderboards?

For single-season Negro Leagues leaderboards, the minimum standard is 3.1 plate appearances or one inning pitched per scheduled game, consistent with the standard we are familiar with in the AL and NL.

However, because of the inconsistencies of Negro Leagues team schedules (or the available data), the minimum qualifier for each league and season is based upon the average number of games played by each team, multiplied by 3.1 plate appearances for hitters and one inning for pitchers. Those values are subject to change as more data is discovered.

As for career leaderboards, the current standard for career MLB leaders is 5,000 at-bats and 2,000 innings pitched, which roughly equates to 10 full qualifying seasons (5,020 at-bats and 1,620 innings). Therefore, for Negro Leagues players, this standard has been set at 1,800 at-bats and 600 innings — roughly the equivalent of 10 seasons’ worth of 60-game seasons.

What if no players met the minimum in a given league and season?

This is the case in three Negro American League seasons (1944, 1946 and 1948). In these cases, MLB applied the Rule 9.22 (a) exception in which theoretical hitless at-bats are added to non-qualifiers’ totals for the purpose of determining a batting rate stat champion.

For this league in these seasons, only one player is listed on MLB’s database under rate stats (average, on-base percentage, slugging percentage and OPS), while counting stats (home runs, RBIs, etc.) will show all players.

Black History Month: Negro Leagues

Black History Month: Negro LeaguesWhy was a 60-game minimum chosen as the standard?

Because it has precedent in the existing MLB historical record. In addition to the COVID-condensed 2020 season in which each AL and NL team played a 60-game schedule, the National League had also played 60-game seasons in 1877 and 1878.

Why did Negro Leagues teams play so few games?

The short answer is segregation. Because of the times, Negro Leagues teams often had to resort to barnstorming exhibitions to keep the business afloat or cut their seasons short when they were out of contention, leading to erratic league schedules.

Generally speaking, Negro Leagues teams played roughly 60 to 80 games per season. This is why you won’t see Negro Leagues players much near the top of leaderboards for counting stats such as home runs or pitcher wins, but you will see them featured prominently in rate stats such as batting average or ERA.

What changes have been made to single-season records as a result of the Negro Leagues’ inclusion?

There are notable changes in five key categories:

Batting Average: Hall of Famer Josh Gibson’s .466 average for the 1943 Homestead Grays is now the highest mark in Major League history, followed by Charlie “Chino” Smith’s .451 mark for the 1929 New York Lincoln Giants. Both of these averages eclipse the previously recognized record held by Hall of Famer Hugh Duffy (.440, 1894 Boston Beaneaters).

On-Base Percentage: Though Barry Bonds’ .609 mark in 2004 still leads, Gibson (.564, 1943 Grays) and Smith (.551, 1929 Lincoln Giants) enter the top five, with Gibson in third place and Smith fourth.

Slugging Percentage: Four slugging marks now eclipse Bonds’ .863 mark with the 2001 Giants. The top spot now belongs to Gibson (.974, 1937 Homestead Grays), followed by Hall of Famer Mule Suttles (.877, 1926 St. Louis Stars), Gibson (.871, 1943 Grays) and Smith (.870, 1929 Lincoln Giants).

On-Base Plus Slugging (OPS): Gibson also tops Bonds (1.421, 2004 Giants) here, with a 1.474 mark with the 1937 Grays and a 1.435 mark with the 1943 Grays.

Earned Run Average: The single-season best still belongs to Hall of Famer Tim Keefe (0.86), of the 1880 Troy Trojans, but the legendary Satchel Paige now ranks third, with a 1.01 mark for the 1944 Kansas City Monarchs.

• Josh Gibson: A larger-than-life legend

Joel Goldberg on Mule Suttles

Joel Goldberg on Mule SuttlesWhat changes have been made to career records?

Again, there are notable changes to these five key categories:

Batting Average: Gibson’s .372 career mark in 2,255 at-bats takes the top spot, surpassing Hall of Famer Ty Cobb’s .367 career average. Hall of Famers Oscar Charleston (.363), Jud Wilson (.350), Turkey Stearnes (.348) and Buck Leonard (.345) are also in the top 10.

On-Base Percentage: Gibson now ranks third all-time at .459, behind Ted Williams (.482) and Babe Ruth (.474). Negro Leaguers Leonard (.452), Charleston (.449) and Jud Wilson (.434) also join the top 10.

Slugging Percentage: Gibson’s .718 mark eclipses Babe Ruth’s .690 mark for the top spot, with fellow Hall of Famers Suttles (.621), Stearnes (.616) and Charleston (.614) also in the top 10.

On-Base Plus Slugging (OPS): Gibson’s 1.177 mark is now the all-time best, ahead of Ruth’s 1.164 mark. Charleston (1.063), Buck Leonard (1.042), Stearnes (1.033) and Suttles (1.031) also enter the top 10.

Earned Run Average: Left-hander Dave Brown, who posted a 2.24 ERA in 711 innings from 1920 to 1925, now ranks eighth all-time.

Where can the full leaderboards be viewed?

At MLB.com’s newly integrated database.

Didn’t Josh Gibson hit 800 home runs? Why isn’t he the new home run champ?

Gibson is the perfect example of the lines that were drawn in this process.

It may well be true that Gibson hit 800 home runs in his career, as his Hall of Fame plaque estimates. But many of those home runs came in “barnstorming” exhibitions that were not part of the official league season and therefore are not included in MLB’s official record.

Officially, Gibson is credited with 174 career homers in league games.

• The legend of Josh Gibson hitting a baseball from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia

Black History Month: Josh Gibson

Black History Month: Josh GibsonDoes this process update the MLB totals for AL/NL players who also played in the Negro Leagues?

Yes, as long as the league in question is one of the seven listed above and from the relevant time period.

Willie Mays, for example, has 10 hits added to his career total (from 3,283 to 3,293) as a result of the known data from his time with the 1948 Birmingham Black Barons. (Though there are newspaper reports of Mays homering for the Black Barons, there are no accompanying box scores to include in the official record. So Mays remains at 660 career MLB home runs.)

On the other hand, Hank Aaron’s career home run total remains at 755, because his Negro Leagues experience came with the Indianapolis Clowns in 1952 — a time by which MLB had been integrated and the Negro Leagues have been ruled to have not been of Major League quality.

Won’t this affect some milestone dates?

Yes and no. Let’s again use Mays as the example. His 3,000th hit was supposedly swatted and therefore celebrated on July 18, 1970. Now that MLB has added 10 hits to his ledger, we can go back in his game log and see that his 3,000th Major League hit actually occurred 15 days earlier.

But the original milestone is what MLB will continue to celebrate. Baseball history is rife with retroactive adjustments to how players and stats are perceived, and this is no different. July 18 will continue to be recognized as the anniversary of Mays’ 3,000th hit, because that’s what it was understood to be at the time he swatted it.

Jul 18, 1970

Mays joins the 3,000-hit clubIs the Negro Leagues data complete?

No. Researchers estimate that the 1920-1948 Negro Leagues records are about 75% complete.

So what if more statistics are discovered?

Should additional box scores come to light and be verified by MLB’s statistical partners — Agate Type Research (formerly the Seamheads Negro Leagues group), Retrosheet or Elias — they will share them with MLB’s data team. This could ultimately result in additional modifications to the game’s all-time leaderboards.

This is also not without precedent in MLB’s history. The official record has been updated many times as newly discovered data or discrepancies have been brought to the fore, such as when Christy Mathewson was credited with his 373rd victory in 1940 — 15 years after his death — to pull him into a tie with Grover Cleveland Alexander for the all-time National League record.

Why does the MLB data differ in some places from what is presented on other sites?

MLB followed the practice that is customary in the AL/NL by not including barnstorming games, World Series games or All-Star Games in the player and pitcher registries. This accounts for many of the differences you might find between a player’s totals listed in the official database and the data presented by other sources.

Where are the box scores and game logs?

The Statistical Review Committee is dubbing this updated database “Version 1.0.” There are sure to be updates to come.

Will there be asterisks attached to the Negro League numbers because of the relatively smaller statistical samples?

No. Here again, the aforementioned inclusions of the American Association, Union Association, Players’ League and Federal League in the official record provide precedent. The Special Committee on Baseball Records ruling in 1969 stated: “For all-time single season records, no asterisk or official sign shall be used to indicate the number of games scheduled.” The Negro Leagues Statistical Review Committee adhered to that ruling.

Sep 16, 2023

Kendrick on Negro Leagues MuseumBut should these stats and records be viewed differently than AL or NL records?

As with all statistics, this is up to the beholder. We can already consider the context of leagues such as the American Association or Federal League and view their statistics either separately from the AL and NL or jointly with the AL and NL. In this regard, the Negro Leagues are no different.

Furthermore, within the AL and NL, we can understand that certain seasons – be it the “Year of the Pitcher” in 1968 (prior to the alteration of the mound), a strike-shortened season like 1994 or the pandemic-impacted 2020 – are statistically anomalous and therefore worthy of added context in discussion. With the Negro Leagues, the most important context is that these players were ignored by MLB because of their skin color and their leagues were left to fend for themselves financially.

Ultimately, the Special Baseball Records Committee that convened in 1969 ruled that “Major League Baseball shall have one set of records, starting in 1876, without any arbitrary division into nineteenth- and twentieth-century.” The Negro Leagues, at long last, now fold into this record set.

What about postseason records?

Stats for the Negro Leagues World Series and the East-West All-Star Games do not count in the batting and pitching registers, just as postseason and All-Star stats do not count in those registers in the AL and NL. But while these stats are not included in “Version 1.0” of the official Negro League stats, they will be recorded and contemplated for subsequent iterations of this ongoing project.

Who are the members of the Negro Leagues Statistical Review Committee?

Seamheads Negro Leagues database researcher Gary Ashwill; author Phil Dixon; MLB Players Association representative Jeff Fannell; Josh Gibson Foundation executive director Sean Gibson; Kent State professor and author Leslie Heaphy; Seamheads Negro Leagues database researcher Kevin Johnson; Negro Leagues Baseball Museum president Bob Kendrick; Elias Sports Bureau director of research John Labombarda; author and researcher Larry Lester; Jackie Robinson Foundation director Sonya Pankey; MLBBro.com founder Rob Parker; MLB chief baseball development officer Tony Reagins; former Major League pitcher CC Sabathia; National Baseball Hall of Fame senior curator Tom Shieber; journalist Claire Smith and Retrosheet president Tom Thress.

The chairperson is official MLB historian John Thorn.

Did you like this story?

Anthony Castrovince has been a reporter for MLB.com since 2004.