Narrelle M. Harris's Blog, page 45

November 13, 2011

Lessons in Language: Writers who don't read

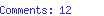

Image from http://bbbsystems.blogspot.com/2011/1...

It seems obvious to me that writers should also be readers, but according to a September 2011 column in Salon, some new writers are apparently finding reading a bore. The columnist is trying to find an equivalent attitude in another field. The only analogy that springs to my mind is "Wanting to write without wanting to read is like wanting to sing without wanting to listen to music."

It's an issue much larger than 'how do you keep up with what's current in literature?'. Reading widely is a vital training ground for all writers, not because of trends in writing, but because of the exposure it gives you to the basic building blocks of writing.

I do not have a degree (in writing or in anything else). I do have a very large vocabulary, though. I have a good, broad general knowledge on a variety of subjects and I'm always picking up bits and pieces of information and concepts, both esoteric and mundane. I read voraciously before becoming qualified to teach English as a second language, and so absorbed vocabulary and grammar by osmosis before I learned how to label the parts of speech.

You may ask what evidence there is that writers are not reading, but sadly, such evidence abounds: mostly in newspapers. News articles are full of the kind of errors that can surely only occur when the writer has only ever heard a phrase and never seen it written down. How else can you explain the following slips?

full-proof instead of foolproof

cries falling on death ears instead of on deaf ears

and my old favourite, changing tact instead of changing tack

Why is it important? (I assume it is the non-reading writers asking this question.)

It's important, dear writer, because words are your business. They are the bricks and mortar, the wood and nails, the paint and canvas of your job, which is to communicate. If you do not know how to construct a sentence that people can understand, you fail to communicate. If you don't know how to punctuate a sentence correctly, you fail to communicate. If you can't think of the exact word to describe your meaning, or you use the completely wrong word because you don't know it *is* the wrong word, you fail to communicate. Or you communicate the wrong thing.

In the instance of 'death ears' mentioned above, it can take power away from your story and, worse, be disrespectful to people in pain. When I first saw the headline 'Woman's cries fall on death ears', I assumed it was a slightly jokey story about some poor woman who had been locked overnight in a morgue or a crypt. But no. It turns out a young girl being raped had cried out for help, but people had walked past without assisting. The writer didn't mean to trivialise her ordeal, but their carelessness and lack of knowledge about a common phrase was awkward, at best.

I don't have a problem with the average person not knowing the right words for the right situation, but writers? Writers who do not understand vocabulary, punctuation and grammar are, to me, like builders who don't understand building and attempt to just slap bricks together without first constructing the foundations and frame.

If you don't know your tools, how can you create the effect you want? How can you communicate your idea clearly if you don't know the right words or how to use them? How can you depart from the rules of grammar and spelling with creative meaning if you don't understand the rules to begin with?

You don't need a writing degree. You don't need to be able to label a past participle or define a secondary object. But you do need to have a feel for a correct sentence and to have an excellent vocabulary. They are both the tools and the building blocks of your craft.

So please, writers, please. Read.

November 6, 2011

Many strings to my bow

A few months ago during the Q&A session of one of my library talks, I mentioned that I had a day job. One of the attendees promptly asked me whether, in that case, my novel writing was just a hobby.

A few months ago during the Q&A session of one of my library talks, I mentioned that I had a day job. One of the attendees promptly asked me whether, in that case, my novel writing was just a hobby.

I have to say, the comment stung a little. I replied that, no, it was not a hobby. That in fact many Australian writers could not afford to write full time and therefore had day jobs as well as writing novels and short stories. Some are lawyers, academics or office workers. We squeeze in our fiction writing around our jobs and families. We get paid, even if it's not always a lot of money. For every writer who also has a day job, writing is not 'just a hobby'.

The fact is, my day job is part of my work as a writer. I'm very lucky that I get to be a writer for my living as well as my vocation. I generally contract my skills out these days, so I have done all kinds of writing: external communications, advertising copy, editing of content for the web, report writing, copyediting.

At present I edit training materials for grammar, punctuation and style. It may sound dull to some of you, but i'm getting paid to be pernickety about grammar, so I enjoy it. I learn a lot too, so it is helping me becoming a better writer in other fields.

Those other fields include writing content for iPhone apps. My app, Melbourne Literary, was done in partnership with the US tech company Sutro Media. They provided the platform (the content management system, basically). I pitched the idea of the app to them and then wrote everything and sourced all the pictures. I've pitched another app idea since then and am in the process of writing that one too. We share the profits of the apps sold through iTunes (and hopefully one day soon through Android). So that's another little bit of income from my writing.

I have my fiction writing, too. So far I've had four novels published, one short fiction story and one non-fiction essay. I wrote a one act play once, and was paid a royalty by the little theatre that performed it in WA a few years ago.

Another writing-related activity I do is public speaking. I talk to libraries and organisations (and very occasionally schools) about different aspects of writing and reading. Of course, being a writer, pretty much everything I do counts as research. Travel, theatre, reading, shopping. It's a good life.

There are so many things to being a writer, especially these days, when diversifying your skills is so important. All writers, these days, also need to be marketers, PR people, public speakers, educators, mentors and more.

I consider myself so lucky to be a professional writer in so many parts of my life. I pay the bills, I nourish my creative self and I have opportunities to meet and encourage other writers and readers. And every different type of writing (or speaking about writing) that I do adds to my knowledge and skills, and makes me a better writer.

Really, I have the best life!

(But I confess, if no-one paid me to write, I'd write anyway.)

October 30, 2011

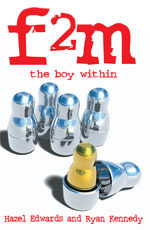

F2M: the boy within – The book that scared libraries

Hazel Edwards and Ryan Kennedy

In mid-2010, I reviewed a fabulous book by Hazel Edwards and Ryan Kennedy called F2M: the boy within. It's a warm, moving coming of age story about transgendered Skye who is becoming his true self, Finn. Co-author Ryan himself transitioned from female to male in his 20s. He brought that experience and courage to the collaboration with his long-time friend and respected children's author, Hazel Edwards. Together they have produced a work that is both an excellent story and an important insight into what life for transgendered people and their family and friends. F2M: the boy within is also about friendship, punk rock, secrets and truth.

Bloggers wrote about it, and psychologists and gender counsellors have picked it up. In talking about the reaction to the book, Edwards and Kennedy noted "We assumed that YA librarians would welcome the fictional opportunity to encourage 'distanced' discussion of gender, including gay issues although our Skye-Finn was not gay. Suicide occurs in trans communities, and maybe we could save a few lives by reducing ignorance and fear of the unknown. Suicides also occur in gay communities, due to family, religious and social pressures. Maybe our book could prevent ignorance contributing to further deaths."

Unfortunately, regardless of how sensitively, intelligently and well written it is, it seems that libraries are frightened of F2M: the boy within. Ford Street Publishing was willing to bring this book to the world, but school and public libraries, spooked by the spectre of controversy, have shunned it. The risk of backlash from conservative groups has kept the book from shelves that would otherwise normally carry Hazel Edwards' books. Literary awards have likewise overlooked it, in spite of Edwards' long association and regular appearance on such lists.

Recently, I spoke to Hazel about the book and its reception.

Narrelle Harris: Hazel, you and Ryan have known each other for a long time. What made you decide to do this project together?

Hazel Edwards: I knew Ryan as a family friend from about age 9 and had kept in touch across his adolescence and early twenties. I enjoy his mind and sense of humour. He is around the age of my adult children. I'd also done some gender research in connection with a medical project about children and was aware that transitioning was a controversial subject about which little had been written in fiction. Even the appropriate vocabulary ( or pronoun) was a challenge.

Since Ryan is NZ- based, I hadn't seen him since his ftm transition, but he came to Melbourne for a computer conference in connection with his work. He looked so much happier. Simultaneously we decided to co-write, via Skype and e-mail , a YA novel utilising his experience, but it was not to be autobiographical.

f2m The Boy Within

Ryan had experienced what it would have taken me years to research. As a published author, I was able to place our book proposal with Ford Street Publishing and gain a contract before we started the intensive year-long writing and about 30 drafts. I knew Ryan was a hard worker. But he was also far more IT skilled than me. It has been an equal collaboration. We were aware that ours might be the first ftm YA novel internationally co-written by an ftm, but we also wanted to write 'a good read' of a 'coming of age' story. Thus, I had to learn punk music, another area in which Ryan is far more skilled.

Fiction provides the opportunity to discuss issues, at a distance, removed from the individual. Family can be given a book like F2M: the boy within as a 'gentle' introduction and an informed way of handling prejudices

Narrelle: F2M: the boy within has received excellent reviews, but it has also met with reluctance from libraries and schools. How do you feel about how the book has been received?

Hazel: We knew the subject would threaten, especially libraries and schools who fear even one parental complaint. Often it is the anticipatory anxiety about potential complaints that cripples possible exposure to a 'mainstream' story where the subject is controversial, but not our handling of it. We have no 'bad' language. But we do have the opportunity to learn a new vocabulary and diplomacy about how gender issues might be phrased. Not just whether you say 'He' or 'She'.

I have been shocked by the 'ignoring' by groups whom I would previously have expected to be open minded. Some of the reactions have been aggressively negative, and they haven't even read the book.

I now realise how courageous Ryan has been in co-writing.

Fan art by Rooster Tails

Narrelle: Given the difficulties you've encountered getting the book to its readership, do you have any regrets?

Hazel: No. If we've saved one life, it's been worthwhile. And if we've enabled readers to view from our 18 year old character's perspective for the length of the novel and beyond, it's been worthwhile.

We knew that some readers would expect F2M: the boy within to be like my picture books for young children like the cake-eating hippo series. It isn't. But I have also co-written a psyche text on Difficult Personalities , including sociopaths, and written of scientific material from an Antarctic expedition. An author can write in multiple fields. What matters is how well they write.

I also have growing admiration for some of the volunteer gender counsellors I've met. My regret is that I haven't known about some of these issues earlier.

Narrelle: What is the best response you've had to F2M: the boy within so far? The worst?

Hazel: Ryan has received poignant e-mails about how significant this book has been to individuals and how they wished it had been available earlier. I've had much favourable contact from parents of gay children (even though our character is not gay) who are grateful for the opportunity to open family discussion via the novel. Being listed for the 2011 White Ravens, top 250 children's and YA books internationally. Word of mouth recommendations are slow but genuine and significant. Being recommended via the Safe Schools Coalition was helpful.

My worst experience was at a literary festival where a student from a Catholic school reported that his teacher had put 'that disgusting' book and the brochure in the bin, in front of all the students. Being ignored or 'left off' lists where my works would normally be included, thus depriving readers of the opportunity to even know the book existed.

Narrelle: Since both public and school libraries have been reluctant to risk controversy by getting it in, what do you think the best way if for people to get hold of it? Would it help if people specifically asked their library for it?

Hazel: Yes to all of the above. And our websites have material and links which are useful for Book Discussion Groups. One soccer parents book discussion group read and recommended it.

I still think this is the most important of all my 200 books, and hope it gets a fair reading in the future. It is not just bibliotherapy about gender, it's a novel novel. At times, Ryan has had to make difficult decisions about refusing some kinds of highly paid magazine interviews which wished to concentrate on his private life rather than the book. That takes courage too. Working with such a courageous man as co-author has been the other bonus of this novel.

**

If you think anyone can benefit from F2M: the boy within, whether they are a transgendered person, their family or friends, or just people you think would enjoy a coming of age story with a difference, you can get F2M: the boy within via the following links.

F2M: the boy within – paperback from Boomerang books

f2m: the boy within

- Amazon paperback

- Amazon paperbackf2m (the boy within)

- Kindle

- KindleF2M: the boy within – Booki.sh

Ask your library to order it in for you or recommend it to your book group.

You can download a study guide here or from Hazel Edwards' website.

Discussion Notes f2m (3MB)

Read more:

Hazel Edwards

Hazel Edwards' F2M page

Ryan Kennedy

Ford Street Publishing

Rooster Tails - blog and fanart (as seen above)

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

October 23, 2011

GaryView: Death and the Spanish Lady by Carolyn Morwood

Lissa: That was a bit of a history lesson. I remember reading about a flu epidemic after the First World War, but I had no idea that it was so bad, or that it shut Melbourne down like that.

Lissa: That was a bit of a history lesson. I remember reading about a flu epidemic after the First World War, but I had no idea that it was so bad, or that it shut Melbourne down like that.

Gary: Yeah. I think one of my dad's uncles died of the flu around when this book is set.

Lissa: This book really brings it home, doesn't it? The historical setting really works, and I liked Eleanor as well. She's working through all this grief, but she really wants justice, whether or not the dead guy deserves it. I like it that the truth was more important to her than staying comfortably out of it.

Gary: You don't think she should have left the murder for someone else to investigate?

Lissa: I think I have amply demonstrated that keeping out of things isn't always an option.

Gary: I guess you have. I liked Sister Jones too, though that might be because she reminded me of my mum. Mum was a nurse too.

Lissa: A nurse detective?

Gary: Not that I know of, but I wouldn't have put it past her. My mum was pretty cool in a crisis. That's how she met Dad, actually. During the war, she was stationed in Greece. Dad had been wounded and she looked after him on the ship during the evacuation from Crete. They kept writing after he was shipped home, and when she got back to Australia they got married.

Lissa: That must have been hard for him, waiting for her.

[image error]Gary: They never talked about it much. Not to me, anyway. Dad had got shot in the leg, though, and they wouldn't let him stay in the army. He went home and did his teaching degree instead, so he'd have a steady job for when Mum got back.

Lissa: Every time you tell me about your folks I think how awesome they were.

Gary: This book made me think of both of them. They both went through a lot. For years as a kid, whenever I saw someone my dad's age, or my grandad's, I wondered whether they had bullet scars too. My mum kept on nursing, too. She used to say the only thing worse than the old air raids was working on the children's wards.

Lissa: I bet.

Gary: Yeah.

Lissa:. So. Death and the Spanish Lady. Did you work out the killer before the end?

Gary: No. I never do, though. Not even when I was alive. I used to try making notes as I read to see if I could work it out, but I never could. Mum said it was because I wasn't devious enough.

Lissa: I guess crime stories aren't really like maths equations. Otherwise all crimes would get solved by the scientists.

Gary: All crimes are solved by the scientists on some TV shows.

Lissa: I like this kind of murder mystery better. And it's not as gritty and realistic as all those Underbelly-type stories, so I like that better too. I have enough gritty realism in my life. But this has a different kind of realism. That sometimes you succeed in something but it's not necessarily a triumph.

Gary: I know all about that, too.

Lissa: You and me both. Hey, how about we cheer ourselves up with a musical. Or a werewolf movie.

Gary: Can I vote for a werewolf movie?

Lissa: Only if it's the original Teen Wolf.

Gary: Teen Wolf it is.

* *

You can get Death and the Spanish Lady in paperback from Readings, or as an ebook from Booki.sh or Amazon.com.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

October 16, 2011

A story in steam

Of all the modes of transport in the world, my favourite is the train. Trains are more spacious and comfortable than either a plane or a bus (or a donkey cart). They lack the equilibrium-disturbing sway and roll of a boat, or the lurch and petrol-stink of a coach. I love the fact that trains are almost exactly the same technology now as when they began operation in the 19th Century. I love catching trains through Europe and feeling the miles role away underneath me, and seeing the landscape slide by. And of all trains, the steam train is my very favourite.

Of all the modes of transport in the world, my favourite is the train. Trains are more spacious and comfortable than either a plane or a bus (or a donkey cart). They lack the equilibrium-disturbing sway and roll of a boat, or the lurch and petrol-stink of a coach. I love the fact that trains are almost exactly the same technology now as when they began operation in the 19th Century. I love catching trains through Europe and feeling the miles role away underneath me, and seeing the landscape slide by. And of all trains, the steam train is my very favourite.

On 1 October, I made my way by suburban rail to Belgrave station to catch the Puffing Billy to Emerald to give a talk at Emerald Library.

Doesn't that sound magical? Belgrave. Puffing Billy. Emerald. Library talk. For me it evokes those wonderful whistle-stop tours undertaken by the likes of Oscar Wilde and Samuel Clements across America. Trains have other literary associations for me, too. Holmes and Watson rattling across the English countryside to investigate some macabre murder; feckless young men in PG Wodehouse comedies fleeing on the milk train from ferocious aunts; the Pevensie children at the station before their last great adventure in Narnia; the Hogwarts Express; the Little Engine that Could.

Doesn't that sound magical? Belgrave. Puffing Billy. Emerald. Library talk. For me it evokes those wonderful whistle-stop tours undertaken by the likes of Oscar Wilde and Samuel Clements across America. Trains have other literary associations for me, too. Holmes and Watson rattling across the English countryside to investigate some macabre murder; feckless young men in PG Wodehouse comedies fleeing on the milk train from ferocious aunts; the Pevensie children at the station before their last great adventure in Narnia; the Hogwarts Express; the Little Engine that Could.

Puffing Billy reminds me of all those things, and has its own special place in the heart of Victorian. I grew up in several states, so I don't think I ever went on the inevitable school trip as a kid, but the same sense of adventure and excitement is still there for adults. Travelling by steam train in the modern day to a local library had a wonderful steampunk sensibility about it.

The Saturday that I travelled was a bit cold and wet, but people still braved the weather to sit with their legs handing out the windows as they hung onto the metal railings. We chugged through bushland, over bridges, through hills, periodically wreathed in smoke and steam. As we rose in altitude, the air got crisper (and chillier). I could see flashes of colour from native parrots darting between trees, and see distant, mist-shrouded hills and lakes. The notes of the whistle as it blows is like a call to adventure on our way to Emerald.

There's another literary association for you. Emerald City. Emerald is actually a lovely little country town, one of the stops on Puffing Billy's route. After recent rain, the town is as green as its name implies. Tim even found a great new café serving excellent coffee just over the road from the library where I delivered my talk on Building Believable Fantasy Worlds. I love those talks. I'm no Clements or Wilde, but I thoroughly enjoy talking to readers and writers and sharing my love of the written word with them. This Oz did not have a man behind the curtain, but it was full of people asking wonderful questions about how to start their own great adventures in writing.

After the talk, we walked back to Emerald Station to catch the Puffing Billy back to Belgrave, this time from the warmth and comfort of the dining car. While pumpkin juice was noticeably lacking, there was lashings of tea, biscuits and fruit cake, the cheerful attentions of the lovely staff and more of those luscious green views before our return to the Big Smoke.

And so ends a day steeped in literary memories, bookish discussion, an appreciation of the Australian countryside and the delights of Victorian-era technology in a hyper-connected cyber world. In other words, a pretty perfect day.

Tim and I travelled as guests of the Puffing Billy Railways.

October 9, 2011

SheKilda Thoughts

The SheKilda Women Crime Writers' Convention is over. Most of us hope it will not be ten years until the next one, though perhaps the convenors may need a longer break. Lindy Cameron, perhaps unwisely, suggested she might be ready to do it all again in five years. We're still waiting to see if she ends up stabbed to death multiple stiletto heels, Murder on the Orient Express-style, by the aghast committee.

The SheKilda Women Crime Writers' Convention is over. Most of us hope it will not be ten years until the next one, though perhaps the convenors may need a longer break. Lindy Cameron, perhaps unwisely, suggested she might be ready to do it all again in five years. We're still waiting to see if she ends up stabbed to death multiple stiletto heels, Murder on the Orient Express-style, by the aghast committee.

The attendees are not aghast at the prospect. In fact, we're rather keen to do it all again next year, no waiting! As I wrote in my previous post, I certainly found the conference rewarding, inspiring and heaps of fun. I also learned a few things and had a few insights.

In the Chills and Thrills: The Why of Crime panel, writers spoke about why that began to write crime and why they chose the kinds of stories they wrote about. Talking about 'chills and thrills' in this context, I realised that, for me, chills referred to the fear experienced when our characters (or we ourselves) become powerless, unable to protect ourselves or our loved ones from harm. Being at the mercy of things we cannot control or evade, especially if those things are unjust and unforgiving, is very chilling. The thrills then come in finding the courage, strength and determination to stand up to the fear. Personally or in our characters, taking on the threat (and hopefully beating it!) definitely provides a sense of thrilling energy to me.

The Bending the Rules panel on crime that crosses with other genres, like SF, fantasy and horror, offered a few other interesting ideas. Mariane Delacourt (who also writes as Marianne de Pierres) pointed out that a crime story provides a natural narrative drive for any genre. I felt that the nature of a crime story, which gives the character an excuse for poking into different levels of society and explores transgression from society's norms, gives a writer a great framework for exploring alien or fantastical societies, their ethics and their social layers.

That panel also veered off onto a discussion on the role of sex and violence in stories and what might be 'too much'. Generally, the panellists felt that as long as the scenes served to explore or extend the story, you wrote what you needed to write. I mentioned my issue of the porn-to-plot ratio too. I'm no prude, but I prefer more plot than porn. If the porn is also plot, it counts as plot, I guess. It was an entertaining discussion, anyway.

Finally, Meg Vann's Just the Facts, Ma'am panel on researching crime novels was a terrific session, providing ideas for the different kinds of crime books and how each type needs different kinds of research. A police procedural needs different types of information and detail than a whodunnit. One insight Vann gave was that for stories involving investigative technology, writers really need to be absolutely on top of all the current developments and then predicting where those will be five years ahead.

Another broad lesson learned was how every writer has a different process. Some plot out a story in very detailed story boards long before they start writing. Others totally wing it from the start. Some research for months before they start writing, others write a first draft and then decide what needs more detail. In the end, it seems there is no 'right way' to write – only the way that is right for each individual author.

Of course, this is just a little taste of what I gleaned from the conference. Thank you again to the organisers, volunteers and guests who made it such a memorable and energising experience.

October 8, 2011

Saturday at SheKilda

It's been a decade in the making, but Sisters in Crime has brought its second SheKilda crime convention to the good – and slightly nefarious – people of Melborne. For two and a half days, women and men (but mostly women) are gathering at Rydges hotel in Carlton to discuss, disect and plot crime and crime writing.

It's been a decade in the making, but Sisters in Crime has brought its second SheKilda crime convention to the good – and slightly nefarious – people of Melborne. For two and a half days, women and men (but mostly women) are gathering at Rydges hotel in Carlton to discuss, disect and plot crime and crime writing.

On this Sunday morning, i am multi-tasking at a panel on Sidekicks and Duos, on the role of partners and helpers in crime fiction. Later today I'll be exploring Crime Travel and something called Just the Facts, Ma'am. I can't recall what that one's about, so it'll be fun to find out. That's aside from all the other fascinating, concurrent panels I can't attend without the assistance of Hermoine's time turner.

Friday night's cocktail part has already thrown me together with fabulous, smart, talented, wise and funny women who are generous with their time and advice. So clearly the convention has started as it means to continue.

Saturday morning's plenary session introduced us to SheKilda's three overseas guests. (SheKilda features a lot of guests – over 70 Australian writers!) Margie Orford (South Africa), Vanda Symon (New Zealand) and Shamini Flint (Singapore) all have different approaches that spring very much from the places they call home and widened my view of the world in a sinle one-hour session. Flint is also so charming and hilarious I've broken my No New Books embargo to pick up the first of her Inspector Singh series.

Actually, I've broken my No New Book embargo for six books so far, inspired by the women I'm meeting and hearing. I have had to construct a psychological time bubble around these books so that they have in my head been purchased before the new book embargo began. I have a lot of time bubbles of that nature, as witnessed by the still-growing pile of books in my book cahe. (See, I still read paperbacks, even though I love my e-reader.)

I have bought The Trojan Dog by Dorothy Johnston, a crime novel set in Canberra. Dorothy spoke on a panel explring how the panelists came to crime writing in the first place. I also bought Scarlet Stiletto: The Second Cut, a collection of previous winners of the Scarlet Stiletto awards. These are the crime writers of tomorrow and I want to see who to look out for. Karen Healey's The Shattering was always on my list, after the marvellous Guardian of the Dead, and seeing her on a YA Crime panel reminded me to grab it quick.

Arabella Candellabra was co-written by a couple of terrific Sisters In Crime, Mandy Wrangles and Kylie Fox, and published by Lindy Cameron's Clandestine Press, so how could i say no? Finally, after being on a panel with Tara Moss, and being utterly charmed by her intelligence, wit, thoughtfulness and general loveliness – and then learning her new book has vampires in it, naturally, I've picked up The Blood Countess.

This blog wasn't supposed to be 'What I bought at Shekilda', but perhaps it best shows how inspired I am by this event. There are so many more books i am adding to my Kindle wish list because these writers all have a unique voice and a textured story to tell. I hear that they go through the same challenges, crises of confidence, oxygen-giving breakthroughts and joy of defeating the tyranny of the blank page that I do.

These shared experiences, leading to such different stories, remind me that persistance, imagination and hard work will see writers through some difficult times. They remind me, too, the important of mentoring and share your own experiences with others. No-one can write your book for you, but they can shine a light on the process. You can see that others have survived those trials of doubt, stealing time from your other responsibilities and inevitable rejection slips.

So, my sisters (and brothers) in crime at SheKilda and in the writing world in general: thank you all for your blogs, your panels, your corridor conversations and your book.

I am looking forward to my Sunday. If you have time, you can slip on over to Rydges and get tickets to individual sessions too. Look up the program at www.shekilda.com.au

October 3, 2011

Authors Suing Libraries. Part Three—The rest of the interview with Sophie Masson

This post follows on from Parts One and Two of Authors Suing Libraries.

This post follows on from Parts One and Two of Authors Suing Libraries.

In the first blog I gave a precis and some opinions about Google Books, the Hathi Trust and whether writers are tacky for suing libraries. The second post was part one of my interview with Sophie Masson, writer and Chair of the Australian Society of Authors, to find out more about the relevant issues.

This is Part Three of the series, the rest of the interview with Sophie Masson. I hope you find it useful

* *

Narrelle: I see that already there are cases of books labelled as 'orphaned' that are not orphaned at all, and the writers are in fact still alive and fairly easy to find. What are the real, practical consequences for the authors of 'orphaned' books if they and their books are not reunited in the relevant database?

Sophie Masson: It is rare indeed that there are real 'orphan works'. Books are either in copyright or they are not. Clearly, when authors are alive, they own the copyright, unless they have assigned the copyright to someone else, ie by way of contract or agreement, as a gift or to a publisher or institution as part of their contract.

In Australia, works come into the public domain 70 years after an author's death. Thus an author's estate (whoever are the author's beneficiaries of the works) own the copyright after the author's death. That can be family, friends, organisations, whoever you've left your copyright to. So even when authors have died, people wishing to do such things as quote from, extract or digitise their works must seek permission from the rights holders. This can be paid or provided free, with acknowledgement, but it must still be requested.

Of course it could be said that sometimes it's very hard to track down who owns the rights in a book published long ago. But it is still incumbent on whoever wants to use it to identify the rights holder. Out of print doesn't mean out of copyright. But where an author is alive, easily identified and is clearly the owner of the copyright, there is simply no excuse that can be made.

What it means for authors if works are abducted in the way those in the Hathi Trust case were, is that not only are you not remunerated for the use of your work, but you have no control over how it is presented. You will get no lending rights if these apply, no reproduction rights payments (CAL), and future legal digitisation of that work will be in jeopardy. And if respectable bodies like university libraries engage in this kind of behaviour, and are allowed to get away with it, what hope is there for any of us to protect our rights as creators?

* *

Narrelle: Many people think a digital repository of all books is a good and noble thing. Is there a model of doing this which the ASA would consider supporting? (One that does not have a commercial aspect, for example? One that was run by the Australian National Library or the Library of Congress in the US?)

Sophie Masson: The ASA is not at all against digitisation per se or a digital respository of books per se, properly constituted. It would be worth investigating whether a national scheme could be devised, perhaps co-ordinated through our own National Library, but with proper consultation with creators, publishers, libraries and readers.

This would also work to ensure that, just as in the 'physical library', authors would be eligible for PLR and ELR on the books in such digital libraries. This is something that would not occur if the standard digital library was based outside Australia, incidentally, as would have been the case with both Google and Hathi Trust.

Readers would not be disadvantaged by such a scheme. Quite the opposite, because it would ensure equity of access throughout the country. Libraries—which have always worked in a happy partnership with creators and publishers—would have a unified system suitable for Australian conditions. And of course it could also be part of an international network of such properly-constituted digital libraries.

What the ASA is dead against is the attempt by some parties to attempt to destroy or dilute copyright. Authors and illustrators depend on copyright for our living. Without it, we would have no royalties, no lending rights, no copying payments, and no way of earning subsidiary rights. Frankly we could not earn a living from our work. And we could not protect its artistic integrity either.

Besides, intellectual property rights are the same as any other property rights. No-one can simply walk into your house and take it over, unless you live in a dictatorship. No-one should be allowed to simply help themselves to your books, either. Whether that is for 'commercial' purposes, as was the case for Google, or supposedly for high-flown 'noble' purposes of access, as was the case with Hathi Trust, doesn't matter. Our rights as creators should be respected, in the world of paper books and in the world of digital books. As I said before, the format makes no difference whatsoever to that. And why on earth should it?

There's this iconoclastic Internet-based movement which claims that 'copyright is theft', rather like the old slogan of 'property is theft'. Authors and publishers have even been characterized as villains for defending rights that these people think shouldn't exist (though of course if it was a question of their own rights it would be a different story!)

Much of this is simply to do with the idea that some people think everything digital ought to be free, because they associate it with the Internet, where things have very often been free. But some of it may also be due to a simple misunderstanding of copyright of books. I think some people may confuse it with a 'patent', whereby you can register an idea as belonging to you and no-one is allowed to even try that idea for at least innovation patent 8 years, standard patent 20 years, unless of course you sell your patent in the meantime.

Patents protect inventors from being ripped off, but they can also lead to situations whereby a company may buy a patent from an inventor and sit on an idea without doing anything about it, purely to stop others developing that particular idea, or to sell it on the highest bidder. This has been claimed by some people to slow progress on worthwhile ideas or to make a grab for things that aren't actually anyone's brainchild (like a wild plant occurring in nature, for instance.)

But copyright such as occurs with literary works isn't about squatting on an idea; it's about protecting the integrity of a creative work. To use a personal example, I have no copyright on the idea of the manhunt for Ned Kelly, and I couldn't and wouldn't want to stop anyone else who wanted to write a novel set against that background. Where I do have copyright is in my actual novel, The Hunt for Ned Kelly, and it is protected by law from piracy, plagiarism and any other unauthorised use.

I mentioned France earlier in regards to these issues. Personally, I think it offers a good model for possible solutions to these issues. The French have always strongly defended their national culture, and literature is a very important part of that. What is less well known is how much they've been anticipating these digital literary issues and working collaboratively with the book industry on solutions for present and future problems.

The successful Google case in France resulted in the Government expanding its already evolving national digitisation program, Gallica, which is run within the Bibliotheque Nationale de France (National Library–http://gallica.bnf.fr/ )

The French Ministry of Culture has been working extensively with authors, publishers, and libraries to make this national scheme into a digital repository of works. They are also working on solutions to the problem of the so-called 'orphan works' by proper research and documentation and by dealing with what they call 'the grey zone'—that is, books published before 1995 where rights holders may or may not be known but where digital rights clauses were not included in contracts.

Digital rights for these books will be established by the Government and Gallica will digitise them—with the permission of authors. Commercial exploitation can remain with the writers, with the publishers if they wish, or instead go to Gallica.

This is potentially a very big and important intervention as it could set the model for e-book commercialisation in France and set national formatting standards, as well as lay the ground for a genuinely collaborative and useful digital repository of books.

**

So there we are. I hope between Part one's summary and opinions and Sophie Masson's detailed responses to my questions, you are no longer as confused as I used to be about Google Books, the Hathi Trust and who, exactly, looks bad when authors feel they have to sue libraries in order to protect their ability to make a living.

Authors suing Libraries. Part One—Just Who Is Being Tacky?

Authors Suing Libraries: Part Two—An Interview with Sophie Masson

Authors Suing Libraries: Part Three—The rest of the interview with Sophie Masson (this post)

September 28, 2011

Authors Suing Libraries. Part Two: An Interview with Sophie Masson

This post follows on from Part One of Authors Suing Libraries: Just Who is Being Tacky? In the first blog I gave a precis and some opinions about Google Books, the Hathi Trust and whether writers are tacky for suing libraries.

This post follows on from Part One of Authors Suing Libraries: Just Who is Being Tacky? In the first blog I gave a precis and some opinions about Google Books, the Hathi Trust and whether writers are tacky for suing libraries.

I wrote to Sophie Masson, writer and Chair of the Australian Society of Authors, about the copyright issues relating to these projects and a few other salient points. The interview got very long, but it's all too useful and informative to edit down, so I will present Sophie's responses in two parts. Here is the first question. The remaining two questions will be addressed next post.

* *

Narrelle: I understand that Project Gutenberg was digitising out-of-copyright books to make them available for posterity and research. What is the difference between them and Google Books/Hathi Trust?

Sophie Masson: Project Gutenberg, as you say, is about digitising truly out of copyright books—books in the public domain, like classics, etc. No-one, least of all the ASA, has a problem with that.

The big difference with the others is that Google Books, initially anyway, was going to digitise every book in the world, in or out of copyright, without reference to rights holders. That was halted in its tracks in the USA in 2005 when authors and publishers sued it for infringement of copyright.

Other countries also followed suit. In France, for instance, Google was separately and successfully sued for attempting to digitise works in a test case relating to books in the holdings of the Lyon public libraries. Google was forced to abandon its proposed digitisation of French books, and instead the French Government stepped up its national digitisation program, known as Gallica.

Google then switched to trying to put together a deal that basically focused only on English-language works, in which the default position would be that rights holders would have to 'opt out' of digitisation by Google, but would be renumerated for it, unlike before. Under that 2008 deal, Google agreed to pay a one-time fee of $125 million (all up) to settle with authors and publishers. Some $34 million-plus of this settlement was to go to the creation of a Book Rights Registry, while the remainder was to go to rightsholders—authors and publishers—whose books Google had already scanned without authorisation.

However, this deal was also struck down this year by Judge Denny Chin because it violated antitrust and copyright law—giving Google "a de facto monopoly over unclaimed works" (also known as 'orphan works', ie works whose rightsholders have not been identified or cannot apparently be tracked down). It thus cut out competition by other possible digital book repositories, including national ones. It also simply assumed that rightsholders agreed because they hadn't opted out, even if they might never have heard of the scheme or met the deadline for 'opting out' that Google had imposed. So it was back to the negotiating table for Google, negotiations which continue today.

The Hathi Trust is a separate but related issue. Once again it is about the issue of so-called 'orphan works.' 'Orphan works' are a contested area and the Hathi Trust, which includes a group of five leading US universities (Indiana, California, Cornell, Wisconsin, Michigan) possibly attempted to exploit the vacuum left by Google by launching its own digital repository of such works.

Trouble was, the Hathi Trust actually identified as 'orphans', many works that are most certainly copyrighted; many by authors who are not only living but active, such as Fay Weldon, James Shapiro, and Angelo Loukakis, the ASA's Executive Director. His 1980s novel, Vernacular Dreams, was copied without his permission and without any attempt to contact him. As he memorably said, this wasn't a case of 'orphaned books—it was a case of abducted books.'

How could the Hathi Trust have thought it could do this? With such blatant mistakes in their publication of wrongly called "orphan' works, what attempt was made to contact copyright holders? What attempt was made to institute a proper process? Was it possibly a unilateral decision to dub as 'orphan' works which most certainly weren't? I would very much like to see the evidence of the extent (if any) of Hathi Trust's attempt to check the ownership and copyright status of the so-called Orphan works.

In blogs and articles, some people have said things like, 'well, these books languished unread on the shelves, authors should be happy their works are being rescued from oblivion!' It's as though a digitised book is seen as somehow different to a physical book; but for heaven's sake, whilst the format of the book is protected by law, usually to the publisher, the main purpose of copyright protection is to protect the content from unauthorized copying!

The Hathi Trust libraries would never have photocopied these works and stuck them on shelves without permission; so why on earth did they imagine they could do it in digital form? Whatever the motive behind it, it was extraordinary behaviour, which is why a lawsuit was brought against them by individual authors and organisational plaintiffs such as the Authors' Guild (USA) and the Australian Society of Authors. And as soon as that happened, suddenly, miraculously, the Hathi Trust discovered that 'mistakes had been made.'

People generally need to realise that there is a huge 'gold rush' going on in the area of e-books and digitised intellectual property. Commercial giants like Google, Amazon, Apple and Overdrive (the world's biggest digital rights management and distribution of e-books to libraries) are, so to speak, pegging out and jumping claims for the mining of the rich goldfields of literature, from creative content to publishing to distribution and library supplies.

They have seen that a digitised future for books leads to immense commercial opportunities for companies canny enough to see the digital writing on the wall, and quick enough to seize control of vast slabs of literature before anyone else cottons on. All of us who love books, whether authors, readers, publishers or libraries, need to be aware of the dangers of the concentration into a few hands of the digital books industry. But apparently it's not only commercial interests that we need to watch out for!

On the positive side, you could say that Google and the Hathi Trust have done us all a favour by bringing these issues out into the open. Maybe what will come out of all this is a workable system that will allow for modern conditions, and provide a fair deal for creators and good access to readers. And I might add that Australian university and other libraries understand our stance and fully support copyright law whilst also wanting better access for readers. So we have a good opportunity here to get together and work towards that.

**

Come back for the final part of the Authors Suing Libraries blogs, the rest of the interview with Sophie Masson, which will look more at the orphaned books issue and a model of preserving Australia's literary heritage in digital format without compromising the rights of authors.

Authors suing Libraries. Part One—Just Who Is Being Tacky?

Authors Suing Libraries: Part Two—An Interview with Sophie Masson (this blog)

September 25, 2011

Authors suing libraries. Part One—Just who is being tacky?

Recently, I retweeted a link to an article about a number of authors and writers' organisations who were suing a group of US libraries for copyright infringement. A discussion ensued with a Twitterer about whether this act made writers look bad.

Recently, I retweeted a link to an article about a number of authors and writers' organisations who were suing a group of US libraries for copyright infringement. A discussion ensued with a Twitterer about whether this act made writers look bad.

My initial response was that I thought it made libraries look bad to be infringing copyright. But as the (very civilised) discussion unfolded I realised I didn't know enough about what these libraries, under the umbrella name of the Hathi Trust, were trying to achieve and why they were being sued.

I figure if I'm going to argue robustly for or against a thing, I should at least understand it. So I started researching.

The first thing I learned was that I'd managed to conflate the issue of the Hathi Trust with the issue of Google Books, whose agreement with authors' groups about how to manage its approach to digitising every book ever has come a cropper in the US Supreme Court. They are two different things, although linked.

Here is my attempt to unravel it all in plain English and offer my opinion as I go.

Google Books

It started when Google decided it wanted to scan every single book ever, including ones that were still under copyright to the original authors. The motive may have been noble—to preserve the world's writing and make it accessible to everyone—but there was an undeniable commercial aspect, to sell books.

Google Books' own FAQ says the following:

Are there any benefits for the general public?

Yes. If the Amended Settlement is approved, United States users will be able to search, preview and buy millions of Out-of-Print books that cannot be found in most bookstores and libraries. In addition, each public library building will have a terminal at which users can search for, read and, if the library is able, print out pages from Books in the Google database.

It does sound good in principle, but it's important to remember that Out of Print is not the same as Out of Copyright, and with the opportunities offered by digital publishing, many rights holders may soon be making out of print books available digitally themselves or through digital publishers without the assistance of Google Books.

However, even those who are not planning to self-reprint digitally have moral and legal rights to what happens to their work, even their out of print work.

To break that down into the personal: the Google Books approach means that Google might scan a digital version of one of my out of print books (like Witch Honour, which was published in the US), without my permission, and then make that available digitally to people who wanted it.

This is despite the fact that I could (and have now) made that book available digitally myself.

I would have had no say in the Google process, though I could (if I knew they'd done it) opt out of it later. Google Books expected to be able to sell copies and send me a cut (if they knew who or where I was) without allowing me to negotiate a price or any other aspect of publication.

Naturally, a whole bunch of people and organisations opposed this model, including non-US authors. The French government, for example, sued to protect the cultural and intellectual property of their citizens. Then they began their own project. More on that later.

Anyway, that idea was challenged in the courts by the Authors Guild (USA). A settlement was reached. The US writers groups were happy enough, but the court has knocked it back as inadequate. The judge felt that the settlement, even though agreed to by all parties, gave Google a monopoly and broke laws pertaining to copyright and anti-competetive behaviour.

At this point in time, no writers groups are suing Google Books, but the Authors Guild and Google Books will have to review their agreement and try it at the courts again.

The Hathi Trust

As part of the earlier Google Books settlement, Google gave up the idea of digitising books they had labelled as 'orphans'.

'Orphaned' books are still subject to copyright law, but Google could not find the official copyright holders. Not being located did not mean the copyright holders were not still out there and entitled to their copyright, of course: only that Google hadn't found them.

This is where the Hathi Trust steps into the story. This group of five US university libraries recently decided to publish those orphaned works, having obtained the relevant digitised files from Google. This means the Hathi Trust could be giving away copies of books, without the writers and copyright holders getting payment they are entitled to, and possibly interfering with actual contracts and agreements currently under negotiation for still-living authors to release e-books.

Overseas writers were particularly horrified by this. How, for example, was a Japanese or French or Eritrean writer to know their book had been scanned, let alone considered orphaned, in order to assert their copyright?

As a result, The Hathi Trust are being sued by several writers and writers' organisations, including the Australian Society of Authors.

It turns out that often, with only a little bit of effort, many copyright holders of those 'orphaned' books can be found quite easily. The ASA and other groups have been finding the parents of these orphans on a fairly regular basis in the last few weeks.

Interestingly, since the I first read about the issue, the Hathi Trust has inched away from elements of it.

Do writers have a right to be paid for their work?

Amazingly, writers are now having to fight in court for their rights to their intellectual property. And they are being called the bad guys for doing so!

To be very clear here: I make my living as a writer and editor. Most of that work is in the corporate sphere, but a growing part of my living is as a writer of books. My intellectual property is how I make my living. If someone's going to try and take my work and my words away from me, without my permission or a negotiated contract of how much I am to be paid for my work, I'm going to be a bit miffed – and less able to pay my bills.

For writers (and publishers), one of the huge concerns is that if this initiative goes ahead without a challenge, the law is paving a path to a destination where writers may not be entitled to royalties. A precedent like that could also affect the intellectual property rights of academics, musicians, software designers and other creative jobs.

Copyright is not the paper and ink

Perhaps many people see digitised information as something that should be free, because so much information on the net is free. It is as though my copyright only exists on paper versions of my work.

My copyright is in the words and the order in which they appear, not in the paper and ink. They start life in digital form on my computer, and go through several transmutations in paper and in digital form until published as a paperback or an e-book. No matter what form it's in, though, it remains my book.

Do people have problems with the intangible nature of intellectual property? If I was a carpenter who made tables and carved beautiful designs in them, people could see the individual item and see that I had made it with my hands. Nobody would think it was okay to just take it away to put in a museum then sell copies of it and give me a tithe of the proceeds, never giving me a say in the process.

But because my words are intangible, and may appear on paper or a screen or in someone saying them aloud, does this mean my right to say those sentences are mine—and to be paid for them—doesn't count? If you make a thing with your brain and a keyboard rather than your hands, don't you still have a say in your work?

But isn't preserving our cultural heritage a good thing?

Of course the preservation of every nation's literary and cultural history is important, but that does not mean the Hathi Trust approach is appropriate.

Even with the purest intentions, libraries are better off asking authors for their permission and collaboration. This is exactly what the French Government has done with its Gallica project. Alerted to the need, and the dangers of not meeting that need, to create digital archives, the French are working in collaboration with authors, illustrators and publishers to create a proper, protected repository of texts.

Another issue, which I haven't yet seen discussed, is whether digital archives will actually last the intended distance. Papyrus has lasted thousands of years; good quality paper hundreds. Paper does deteriorate and a more durable form of record-keeping is needed, but it's not clear to me that digitised data will meet that need in the long term.

What we currently know about digital data is that the tech keeps changing, that data corrupts and that digital data is vulnerable to magnetic fields. The last time I spoke to an archivist about this issue, some years ago, there were concerns about the future of such a relatively young form of retaining texts and images. Even if advances have been made, we haven't had a thousand years yet to see how well the archives last. All of this may end up wasted effort.

Writers are interested in the future too. It would just be nice if our right to earn a living from our work wasn't seen as some kind of vulgar grab for money.

* * *

Come back next time for my interview with Sophie Masson of the Australian Society of Authors about the Hathi Trust, Google Books, Project Gutenberg, the Gallica archiving project and whether patent law is confusing the issue.

Further reading:

http://techland.time.com/2011/03/23/explaining-the-google-books-case-saga/

http://blogs.siliconvalley.com/gmsv/2011/09/the-google-books-story-continues-no-ending-in-sight.html

http://www.artshub.com.au/au/news-article/news/arts/authors-groups-sue-over-copyright-185587