Heather King's Blog, page 7

October 10, 2016

THE ENGLISH COUNTRY HOUSE ~ The Entrance Hall

The carriage draws up in front of the Country House and the visitor alights. The butler opens the door or doors to admit the new arrivals and the first impression of the interior they receive is within the Entrance Hall.

From the Great Halls of medieval times to the formal grandeur of the Georgian mansions, the role of the hall was to welcome the visitor and at the same time be a flag-bearer for the owner’s social standing. The medieval hall had to be large enough to house the lord’s hearth knights, courts of justice, huge gatherings for feast days and bands of travelling minstrels or players. It also had to be lofty enough for the central hearth to give no fear of setting the roof alight. It is from the medieval Great Hall that so many old houses – such as the Elizabethan Hardwick Hall and Palladian Holkham Hall – are thus titled, rather than House or Castle.

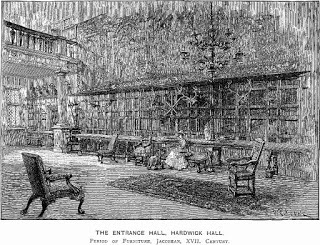

Entrance Hall, Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire

Entrance Hall, Hardwick Hall, DerbyshireRobert Smythson, completed 1597

[image error]Christmas Garland, Entrance Hall, Cotehele

Attribution: Adrian Platt

On a far smaller scale, built in 1709, the Entrance Hall of Hanbury Hall shows a similar style to Hardwick, with the awe-inspiring addition of James Thornhill paintings on the staircase.

Staircase, Hanbuty Hall

Staircase, Hanbuty HallThe early Great Halls were usually built with two rows of pillars or posts to support the roof, with an aisle down the centre. Over time these evolved into wide span roofs, braced initially by arches and later by hammerbeam, which projected from the wall below a main rafter. There was a dais at one end, for the lord’s table and doors at the other, leading, via a long corridor to the kitchen, and also to the pantry and buttery. These huge rooms were decorated with tapestries, to help retain heat where wealth permitted, and hung with armaments, coats-of-arms and martial trophies.

By the sixteen hundreds, the upper servants had followed the family’s desertion of the great hall and begun to eat in a separate parlour. The 1st Earl of Dorset commissioned the King’s plasterer, Richard Dungan, to create a flat, decorated ceiling below the timbers of the medieval roof at Knowle. Economic need then brought about more compact houses for the gentry, with the kitchen and a servants’ hall hidden ‘below stairs’. Slowly the entrance hall was changing towards a more Continental usage, as a reception room for visitors awaiting an interview. Built in 1692, the Marble Hall at Petworth (seat of the Duke of Somerset) is an example of this, boasting huge mouldings, elaborate door and window surrounds, and a view through several doors to a classical bust on a plinth in the North Gallery. This ‘axial vista’ was a popular feature during the Baroque period and can also be witnessed at Chatsworth House. Of the same timescale as Petworth, the Painted Hall at Chatsworth (also in Derbyshire) was created for the 1st Duke of Devonshire by William Talman. There were originally two flights of curving stairs where today there is just the one, straight staircase, but with the gallery adjoining it, the hall is possibly even more imposing. Scenes from the life of Julius Caesar by Louis Laguerre adorn the walls above the fireplace facing the entrance and an assembly of the gods, by the same artist, appropriately decorates the ceiling.

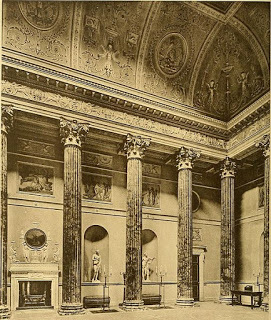

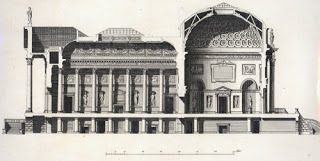

Kedleston Hall, also in Derbyshire, boasts a Marble Hall designed by Robert Adam on the lines of a Roman atrium, with columns and classical statuary so it resembles an open courtyard.

Marble Hall, Kedleston Hall

Marble Hall, Kedleston HallCross-section of the hall and saloon…

…and Kedleston Hall from the outside. You can see the pediment above the domed ceiling of the hall in the picture above.

Attribution: Glen Bowman from Newcastle, England

Attribution: Glen Bowman from Newcastle, EnglandAt Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire, an enormous, church-like lantern was erected sixty-seven feet above the hall, its ceiling showing a painting of Marlborough’s battle victory by Sir James Thornhill, completed before he fell foul of the Duchess and was dismissed for suspected sharp practice over his charges. There is a similar, if less grand, arrangement at Berrington Hall in Herefordshire, designed by Henry Holland. Nevertheless, the lantern in the Staircase Hall still takes the visitor’s breath away when first they see it.

Staircase Hall, Berrington Hall

Staircase Hall, Berrington Hall Skylight, Staircase Hall, Berrington Hall

Skylight, Staircase Hall, Berrington Hall Marble Hall, Berrington Hall

Marble Hall, Berrington HallAt Berrington, the French-influenced Marble Hall leads into the Staircase Hall, as shown by this view through the house.

Through Staircase Hall, Berrington Hall

Through Staircase Hall, Berrington HallThere are tapestries on the walls, but they date only from 1902. This was a country gentleman’s seat and therefore more modest. Some of the grandest houses of the Georgian era have rococo plaster mouldings in elaborate panels, often in the classical designs of urns, wreaths and garlands. This is a picture of some of the plasterwork at Berrington.

Wall detail, Marble Hall

Wall detail, Marble HallBerrington Hall

By contrast, this is the entrance hall of Sutton Scarsdale Hall in Derbyshire.

Entrance Hall, Sutton Scarsdale Hall

Entrance Hall, Sutton Scarsdale HallOriginally, the Hall was part of a Saxon estate mentioned in the Domesday Book as belonging to Roger de Poitou. Knighted by Henry VIII, John Leke passed the property to his son Francis, was created a baronet by James I in 1611. He further advanced to the peerage when made Earl of Scarsdale in 1640 by Charles I. The 4th Earl, Nicholas Leke, commissioned Francis Smith to build a Georgian mansion surrounded by gardens, incorporating some of the existing house. Oak panelling and a mahogany staircase were installed; elaborate plasterwork was designed by Italian Francesco Vassalli, and fireplaces were carved in the style of Adam by brothers Adalberto and Guiseppe Artari. When the Earl died, the Hall was sold in 1740, becoming the property of the Marquis of Ormonde through marriage. In 1824, Richard Arkwright Junior, son of Sir Richard, the inventor of the water frame which revolutionized the cotton industry. In 1805, Robert Arkwright married Frances Crawford Kemble, not only a member of the celebrated acting family but also the niece of Sarah Siddons.

Sutton Scarsdale House

Sutton Scarsdale House Engraving of Sutton Scarsdale Hall, c. 1820

Sadly, as is the case with Witley Court in Worcestershire, the Hall is now a picturesque ruin.

Scarsdale House

Scarsdale HouseAttribution: Stephen G Taylor

The Entrance Hall at Witley Court looked like this in 1882. The entrance doors are to the right of the photo.

Entrance Hall, Witley Court 1882

Entrance Hall, Witley Court 1882Now it looks like this, but the scale and grandeur of the house are still evident. This shot is also taken towards the grand staircase with the entrance doors behind the camera on the right. The support beams beneath the arches on the right show where the gallery was.

Entrance Hall towards grand staircase

Entrance Hall towards grand staircaseThis view shows the Entrance Hall in the other direction and the arched windows of the dining room. A ruin it may be, but Witley Court is an awe-inspiring and inspirational place to visit.

Entrance Hall towards Dining Room

Entrance Hall towards Dining RoomWitley Court

If I have whetted your appetite to visit one of our wonderful stately homes, then I have achieved my aim. The National Trust and English Heritage do a wonderful job of caring for these properties, so if you can, please support them.

Unless otherwise stated, all photographs © Heather King and Public Domain images courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Published on October 10, 2016 15:13

September 12, 2016

HORSES IN ART ~ FROLIC IN THE FOREST

HORSEWOMAN IN THE BOIS DE BOULOGNE

In this, the tenth in my series on equestrian art, I look at another painting I love. It will be familiar to many, since it was painted by no lesser personage than Pierre Auguste Renoir (1841-1919). An oil on canvas, it measures 89” x 102¼” (7’5” x 8’6¼”) or 226 x 261 cm and hangs in the Kuntshalle in Hamburg, Germany.

The portrait, of Renoir’s patron, Madame Darras, was painted in 1873. Madame, a picture of Victorian equestrian gentility in sober-hued riding habit, shirt and tie, is looking somewhat stern as she glances down at her companion, Joseph LeCoeur, on a lively pony. She carries a long whip to replace the absence of the leg on the offside of the horse. I also suspect she may give the pony a tap on the shoulder to remind him of his manners should he attempt to barge in front of her own mount. It is said that when the painting was presented to the Salon jury of 1873, they threw up their hands in horror (perhaps not literally) and refused to accept it. The story goes that Monsieur Darras had foreseen this, saying to Renoir:

“Blue horses! Whoever heard of such a thing?”

Horsewoman in the Bois de Boulogne, Renoir

Horsewoman in the Bois de Boulogne, RenoirCourtesy Wikimedia Commons

This was before the Impressionist Age had truly begun and before that appellation had even been coined. Renoir and Monet were still experimenting with light and colour; this style of painting was quite a shock to the establishment, so it is hardly surprising the picture met with derision.

However, viewing it with a modern eye and loving horses as I do, I can appreciate the skill which has captured the very real blueness that a grey horse’s coat can assume in certain light conditions and from particular angles as well. A grey horse is born dark, sometimes close to black, and the skin is very dark beneath the coat. As the animal ages, the darker hairs (whether ‘dapples’ or merely flecks) lighten until in extreme age the horse becomes white. The pony is a fine example of a dapple-grey, while the horse would appear to be a roan (darker hairs intermingled with the white), although with the tinge of brown on nose and body, it is possible it is a bay that has been clipped out (had the hair removed from its coat to prevent excess sweating). Clipped bays can sometimes appear greyish. Frequently, a dapple-grey will retain his markings on his lower limbs until well into his teens.

One thing I love about the painting is the sheer joy exhibited by both equines. The pony, in particular, is raring to go. His ears are pricked, his head is up and his eyes are bright. He is taking a strong hold on his kind Fulmer snaffle bit, yet his rider is unperturbed by his eagerness and clearly has just checked him back. The boy sits well and is eyeing Madame as if to say, “I’m all right. May we gallop, now?”

By contrast, Madame Darras’ horse is the picture of manners and elegance. The head carriage would not look out of place in a modern dressage arena, while Madame’s hand on the rein is light. The reins of her double bridle loop; there is no tension between the pair. The horse also has its ears pricked and is bounding forward in a springy, willing rhythm. The light catches the gleam of its well-groomed coat and it is evidently a quality animal which receives the best of care. Madame sits proudly on her steed, but if the impression she gives is one of aloofness, bear this in mind. When riding side-saddle, both legs are on the left hand side of the horse. It is therefore essential that the rider sits centrally and erect in the saddle or she will lose her balance. Posture is not just preferable, it is a core requirement of the activity and far more necessary than when riding astride. Madame is the image of a well turned out, skilled equestrienne.

This portrait encapsulates the pleasure of riding for its own sake, the enjoyment derived by both horse and rider when hacking in the countryside. It not only demonstrates the bond between a horseman (or woman) and their steed, it shows how the role of the horse was changing. These two beautiful animals (and mistake me not, little ponies have their own infinite charm!) are not being used for transport, nor for the chase; they are early examples of the horse as a leisure animal, more of a pet than a working beast, and as such, social history at its finest.

Published on September 12, 2016 11:18

August 27, 2016

The English Country House...

A Grand Prospect

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, medieval castles and sprawling manor houses evolved into a more formal residence where gardens were laid out in geometric patterns involving strictly linear paths and clipped hedges. Knot gardens and parterres often fronted the large residence, such as at Wilton House in Wiltshire, which was planned to entertain royalty. At Hanbury Hall in Worcestershire, built at the time of Queen Anne, in 1701, the parterre to the side of the house is still immaculately maintained.

Hanbury Hall, Parterre

Hanbury Hall, ParterreBy the extended Regency period, however, the visitor was likely to approach a country house via a long drive, passing between wrought-iron gates guarded by a lodge, where, no doubt, a lodge-keeper would be on hand to proffer a courteous greeting. The equipage, whether travelling coach or chariot, sporting phaeton or curricle, leisurely barouche or landau, or, indeed, the doctor’s homely gig, would then proceed at a brisk trot through an expansive vista of rolling parkland dotted with ancient oak, horse chestnut and beech trees. Between the gnarled branches covered in lichen, a view of a sparkling lake was almost de rigueur, while various follies and perhaps an ice-house would also be glimpsed in secluded positions around the estate. The periphery of this acreage might be enclosed by carefully crafted iron railings, a high brick wall or even a sweeping stone boundary softened by ribbons of ivy and, in shady spots, the feathery touch of mosses.

At Berrington Hall in Herefordshire, the carriageway (now a tarmac drive) for 'guests from London' snakes across the park to a ‘Triumphal Arch’ or gatehouse, whereby the traveller enters the more formal surroundings of neatly tended shrubs and paths.

[image error]

On the other hand, at Witley Court in Worcestershire, the now long-gone approach, built by Lord Foley in the seventeenth century, was an ambitious causeway across the lake (the Front Pool), to bring the visitor to the imposing North Front. A painting by Edward Dayes (1763 – 1804) is possibly the only surviving image of this approach, as represented here by a print produced by William Angus (1752 – 1821) in 1810.

[image error]Witley Court in Worcestershire, the Seat of Lord Foley

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

This is how the Front Pool looks today. A path follows the dam, to the left of this picture, allowing visitors to walk up to the North Front. What an imposing sight it must have been for those long-ago guests of Lord Foley, to ride in a carriage to this huge mansion!

[image error]

[image error]

The church, seen in the upper photo, adjoins the North Front and West Wing, to the right of the lower picture.

In some of the grander establishments, such as at Stowe House in Buckinghamshire, the main carriage drive passes over a humpback bridge, then to afford the visitor a grand vista across the parkland to the even grander house.

[image error]Oxford Bridge, Stowe

Creative Commons Attribution Share-alike Licence 2.0

Attribution: Nigel Cox

In all probability, the coachman slowed his horses within sight of this imposing residence, where often the sweeping road forked, one arm leading to a gravelled forecourt in front of the house…

[image error]

…while the other arm continued to the sumptuous, pedimented stable block where my lord’s hunters and carriage horses were cared for in palatial stalls by a dozen or more dedicated grooms.

[image error]

Carriages no longer draw through the gates of the Berrington Hall gatehouse, but the approach to the house is still a pleasing prospect.

[image error]

Meanwhile, at Brockhampton House in Herefordshire, the drive is a long, gentle curve to the red-brick Georgian mansion…

[image error]

…and the path to the fifteenth century Manor House at Lower Brockhampton passes beneath a timber-framed gatehouse over a moat.

[image error]

At Hanbury Hall, you can see where the formal approach once stretched across the park, between an avenue of Cedar trees.

[image error]

Many large houses had the parkland landscaped in the current vogue, epitomized by Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown and Sir Humphrey Repton, to name but two, in order to provide a grand prospect, both for the visitor on arrival and my lord’s appreciation of his estate. At Brockhampton House, the mansion stands on the top of the hill, overlooking 1,700 acres of parkland, including the ‘Lawn Pool’, an ornamental lake created as a landscape feature and for the family’s recreation, now being carefully managed by the National Trust. It is a very fine prospect indeed.

[image error]

The landscaper’s intention was to take the eye across sweeping parkland dotted with ‘natural’ groupings of trees to some imposing vista or focal point, such as a monument, folly, pavilion or gothic temple. This Wall Pavilion is at Witley Court, although it wasn’t added until the gardens were redesigned by William Nesfield for the Earl of Dudley between 1854 and 1860.

[image error]

Below is a ruined ‘temple’ on the Stanford Park estate in Worcestershire.

[image error]

I hope you have enjoyed this little taste of how the Georgian gentry and nobility instilled an air of majesty into their parks and a sense of awe into their guests. Over the coming months I plan to lead you on a tour of the magnificent buildings their aristocratic owners thus displayed ~ a legacy we are so fortunate to have and should enjoy and appreciate in equal measure.

A rip-roaring hip-hip-hoorah for the National Trust, English Heritage and the other wonderful institutions which do such sterling work in preserving these houses for this and future generations!

Unless otherwise stated, all images are the property of the copyright holder and must not be copied, shared or otherwise distributed without the expressed permission of the publisher.

Published on August 27, 2016 12:29

July 25, 2016

The English Country House

This an introductory post about the classical Georgian country houses of which Great Britain is so blessed. I intend to look at aspects of these houses in more detail in the coming months.

Lower Brockhampton, Georgian house

Lower Brockhampton, Georgian house(C) Heather King

The medieval castles and sprawling manor houses had already evolved into a more formal residence during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Gardens were laid out in geometric patterns with strictly linear paths and clipped hedges. Knot gardens and parterres often fronted the large residence, such as at Wilton House in Wiltshire, which was planned to entertain royalty.

By the extended Regency period, however, the visitor was likely to approach a country house via a long drive, past a lodge (complete with lodge-keeper) and proceed at a brisk trot through a sweeping vista of rolling parkland dotted with ancient oak, horse chestnut and beech trees. Between the gnarled branches covered in lichen, a view of a sparkling lake was almost de rigueur, while various follies and perhaps an ice-house would also be glimpsed in secluded positions around the estate. Closer to the house, the winding road forks, one arm leading to the sumptuous, pedimented stable block where my lord’s hunters and carriage horses are cared for in palatial stalls by a dozen or more dedicated grooms. The other arm continues to a gravelled forecourt in front of the house.

Built frequently in a quadrangle, for protection from prevailing winds as well as to contain unpleasant odours – so as not to upset the delicate sensibilities of the lady of the house – and keep hidden the plebeian tasks undertaken therein, these vast constructions were usually entered beneath an archway surmounted by a clock tower. Long buildings faced in stone or brick contained lines of stalls, the occasional stallion and/or foaling box, harness rooms, feed rooms and hay barns. When members of the tondescended on an aristocratic country estate, there were a large number of horses and servants to be accommodated and fed. It did not suit a gentleman’s sense of worth if he could not provide stabling for his guests’ cattle.

[image error]Stable Arch, Berrington Hall

(C) Heather King

The Palladian mansions of the eighteenth century were often arranged in a square or rectangle around a central hall. Sometimes, as in Hagley Hall in Worcestershire, towers were constructed at each corner, thus allowing for a porticoed entrance on the front and rear aspects. Rooms led one into another, enabling two overlapping circuits, one of the public apartments and one of the private. The principal floor at Hagley included a gallery stretching the length of the house; hall, saloon, drawing and dining rooms, and two bedrooms with dressing rooms alongside. Staircases led upstairs from both sides of the central hall and saloon (and yes, it was termed saloon rather than salon!), with a servants’ access hidden behind the doorway to a dressing room. There was also a library on this floor, in the private part of the house. Thus Hagley Hall was designed (in about 1752) in the same manner as the earlier, formal house, yet with different purposes in mind. An alternative arrangement was provided by a wide entrance front, with mirroring wings extending out to the rear of the house.

At Berrington Hall in Worcestershire, the Staircase Hall is two storeys, topped by an awe-inspiring domed window, admitting light into what would otherwise be a dark, gloomy space. The balconies around the hallway are fronted by decorative cast-iron balustrades and columns of golden brown scagliola.

[image error]Staircase Hall, Berrington Hall

(C) Heather King

[image error]Skylight, Berrington Hall

(C) Heather King

At Hanbury Hall, also in Worcestershire, James Thornhill painted a glorious series of murals to decorate the staircase. Various scenes from the life of Achilles are depicted in rich colours and flowing lines. The detail, and the fact that they are still there to be enjoyed by the grateful visitor after more than 300 years, is a testament both to the artist and the care of the National Trust. The paintings were completed in 1710.

The Drawing Room was for show rather than relaxing, unlike our lounges and sitting rooms today. They were furnished with delicate, spindle-legged chairs and sofas, often with pie-crust or marquetry-topped occasional tables nearby for the convenience of guests. Side tables (not to be confused with those employed for personal use) were rectangular pieces of mahogany or, in an earlier age, walnut, set against a wall for the displaying of ornaments, silverware or a drinks tray. Often incorporating a pier-glass (large mirror) above, in many cases they are not free standing, having only two legs. Small groups of chairs encouraged diverse conversations among house guests. For more informal use, the lady of the house might well have a smaller parlour for her personal or family use, which, in all likelihood, would contain a desk, armchairs and a cabinet. She might keep her sewing box here, too.

The Dining Room was also intended for ostentatious display. Georgians were not shy about showing off their wealth. Costly furniture, moulded door cases, ornately-mounted pier-glasses and rich paintings were all part of that desire to be seen to be affluent. A large, extendable table of highly-polished wood was centre stage, while a sideboard, wine cooler, cellarette with zinc-lined drawer for the washing of plates, various serving tables and a commode were all considered essential for the diners’ comfort.

Originally a place for exercise when the weather was inclement and often appropriated by the children of the family or young bloods for such games as cricket or hide-and-seek, over time the Gallery became more widely used as a ballroom and area to display pictures, surely the forerunners of modern art galleries and museums.

Many larger establishments, such as Chatsworth and Blenheim, have State apartments, decorated on a grand scale, for visits of nobility and royalty. These rooms occupy the most prestigious position in the house, whereas in the more modest mansion, this is reserved for the master and mistress’ bedchambers. Usually at the front of the house, with extensive views over the parkland, my lord and lady’s chambers were situated next to each other, with a connecting door and often a dressing room in between. The dressing room also had access to the corridor servicing the suite, to enable the servants to enter without disturbing their employers.

In addition to the library and/or a study for his lordship, a country house was likely to have a chapel (sometimes within the house), a smoking room, a billiards room and even an estate office. There would be, of course, a nursery wing with bedrooms for the children, their nursemaids and governess. The main stairs would lead no further than this floor, but the back stairs would continue to the servants’ quarters and the attics above. The butler and housekeeper had private sitting rooms as befitted their elevated status in the servants’ hall.

The kitchens of a country house were situated either at the rear of the house – sometimes within the mansion itself and sometimes in a separate building connected by a passage – or in the basement. In the former arrangement, the dairy, laundry and bake-house would also be housed in the kitchen range or nearby.

In order to be near their charges, the grooms and the coachman were billeted in rooms above the stables, although on occasion, the head groom was provided with a cottage.

This is just a brief look at the English Country House. If it has whetted your appetite, then I have achieved my aim and I hope that those readers domiciled in the United Kingdom will feel enthused to visit one of the many properties open to the public! We must support them or risk losing them forever.

Published on July 25, 2016 12:26

July 24, 2016

Smashwords Summer/Winter Sale

Summer is here at last!

To celebrate, I've put all of my back list books apart from Devil's Hoof in the Smashwords Summer/Winter Sale at 50% off!!!

So, why not go and pick up a bargain for the beach/mountains/lazy afternoon in the garden???!

You've got until midnight on 31st July (Pacific time) to stock up your kindle, e-reader or PC!! The coupon is SSW50

Lots of authors are taking part. Check them out here.

Published on July 24, 2016 14:53

June 25, 2016

HORSES IN ART ~ PRINCE OF PRIVILEGE

PRINCE BALTHASAR CARLOS ON HORSEBACK BY DIEGO VELÁZQUEZ

This is the ninth in my series featuring equestrian portraits and this time I am looking at a pony. There is no better fun for many a child than messing about on their pony and this portrait sums up that excitement and joy, even if the young prince looks rather serious.

The portrait was painted circa 1635-6, measures 82” x 68” (6’10” x 5’8”) or 209 x 173cm and is an oil on canvas. It is currently located at Prado, Madrid in Spain.

[image error]Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Diego Velázquez was a great Baroque artist. When he painted young Prince Balthasar Carlos, son of Philip IV, he had been a favourite of the King and the Spanish court for more than ten years. The portrait was commissioned to hang over a door between paintings of the King and Queen, in the Salon de Reinos at the Buen Retiro Palace.

The prince, all of six years old, is depicted as a military commander, a general’s gold sash adorning his chest, his sword at his hip and his baton raised ready to direct his forces. He is garbed in the finest gold cloth, secure and confident in both his status and his prowess. The pony is also decked out in gold accoutrements; bridle, breastplate, saddle and stirrups all sparkling beneath the artist’s clever use of highlights. This is no common, hairy pony. This is a fiery steed fit for a prince and is shown charging towards the viewer.

In the background, rolling, wooded hills rise away to snow-capped mountains, perhaps in representation of the country around El Pardo in the north of Spain, where the court had hunted since the 1400s.

By modern standards, the pony is fat, his neck appearing short as he arches it. Nevertheless, the prince is riding with a light contact on the mini curb bit, the rein a fine ribbon of gold. Both rider and pony are confident, each with the other; the prince is secure in his saddle, his hand steady on the rein, while the pony’s eye is calm and focussed as he willingly bounds forward. His mane and tail billow with a similar exuberance, no doubt the result of much diligent brushing by his groom.

One cannot help but feel for the young prince. He has the expensive, well-schooled pony and all the trappings of wealth and privilege, yet, unlike the child from less exalted bloodlines, duty and expectation are never far away. One hopes that the joy of messing about with his pony was not denied him, even if the price of such pleasure was the company of grooms, rather than parents, and the heavy burden of achievement. The same could be said of many a budding show ring star of the twenty-first century. Love cannot be bought, but sometimes there are strings of credit and success attached. It may be said that has been the destiny of princes throughout history… and equally, the pampered ‘princesses’ of today.

© Heather King

Published on June 25, 2016 14:04

May 29, 2016

The Gentlemen’s Clubs ~ Part Three

The Macaroni Club

Strictly speaking, the Macaroni Club was not a club for dining, gaming and conversation in the manner of the other gentlemen’s clubs, although they did meet at one of William Almack’s houses in Pall Mall – very likely Number 49, since there was a connection with Edward Boodle who managed Boodle’s. Boodle’s founding members originally met in this house.

The name ‘Macaroni’ comes from the young gentlemen who returned from the Grand Tour with a fondness for the Italian pasta, which was little known on these shores at that time. Horace Walpole, in a letter of 6 February 1764, is deemed to have made the first known comment about the Macaroni Club, when he wrote, it is ‘composed of all the travelled young men who wear long curls and spying-glasses.’ A contemporary magazine, according to one source, states that these travelled and scholarly souls ‘judged that the title of Macaroni was very applicable to a clever fellow; and accordingly, to distinguish themselves as such, they instituted a club under this denomination, the members of which were supposed to be the standards of taste in polite learning, the fine arts, and the genteel sciences; and fashion, amongst the other constituent parts of taste, became an object of their attention.’

[image error]The Macaroni, Philip Dawe

From the Oxford Magazine of 1770 comes this satirical description:

‘There is indeed a kind of animal, neither male nor female, a thing of the neuter gender, lately started up among us. It is called a macaroni. It talks without meaning, it smiles without pleasantry, it eats without appetite, it rides without exercise, it wenches without passion.’

Thus the Macaroni, described rather unkindly in another account ‘as a person who exceeded the ordinary bounds of fashion’ became synonymous with foppery. This encompassed affectation in manner and speech, in addition to the employment of the extremes of fashionable life, including fastidiousness in all matters of dressing, dining and gambling. Cartoonists such as Cruikshank and Gilray took great pleasure in ridiculing the most famous of them.

[image error]What Is This My Son Tom, 1774

The Macaroni Club was but the predecessor of the Corinthian and Dandy set and by 1772 they were outliving their welcome. The beau monde grew tired of their ‘absurdities of dress and manner’ and they were termed ‘coxcombs’. The effeminate air was superseded by the athletic prowess and masculinity of the Corinthian and his well-dressed compatriot, assisted in no small degree by the hounding of the popular press.

The Dilettanti Society and The Hellfire Club

The Society of Dilettanti (literally meaning lovers of the Fine Arts) were a group of men who, having travelled about the Continent and thus discovered an appreciation for the arts, beauty in all its forms and ‘antiquarian remains’, decided to form a club to promote these matters. First formed at Parsloe’s in 1734, they removed to the Thatched House tavern in St. James’s, where, during the London Season, they held dinners on Sunday evenings. In a letter to Sir H. Mann, in connection with a subscription for the opera, Horace Walpole had this to say about being a member:

‘The nominal qualification is having been in Italy, and the real one, being drunk ; the two chiefs are Lord Middlesex and Sir Francis Dashwood, who were seldom sober the whole time they were in Italy.’

The public room at the Thatched House was large and faced St, James’s Street. It was lined with portraits of the Dilettanti members, and when lit by candlelight the paintings could be seen from outside. The ceiling was painted to represent the sky, and ‘crossed by gold cords interlacing each other, and from their knots were hung three large glass chandeliers.’ John Timbs then describes the frontage: ‘Beneath the tavern front was a range of low-built shops, including that of Rowland, or Rouland, the fashionable coiffeur, who charged five shillings for cutting hair, and made a large fortune by his “incomparable Huile Macassar.”’

He goes on to say there was a passage through the hostelry to Thatched House Court and the evocatively-named Catherine-Wheel Alley, where lived ‘the good old widow Delaney’.

The Dilettanti Society were responsible for sending eminent gentlemen abroad in search of antiquities, both to collect measurements, drawings and elevations and purchase artefacts. Various venerable works were produced through the sponsorship of the society. Possibly the most famous acquisition was by the Earl of Elgin, Ambassador in Constantinople, who brought the ‘Elgin Marbles’ to Britain.

Other celebrated members, besides Lord Middlesex and Sir Francis Dashwood (later 11th Baron le Despencer), included Sir Joshua Reynolds, the Dukes of Norfolk, Bedford and Dorset, Charles James Fox, Hon. Stephen Fox (later Lord Holland), David Garrick, George Selwyn, John Towneley, the Marquises of Lansdowne and Northampton, Earl Fitzwilliam and the Earl of Holderness, Lord Robert Spencer, George Colman, Richard Payne Knight, Sir William Hamilton and Sir George Beaumont.

As previously said, their portraits – many painted by Reynolds – adorned the walls of the Thatched House meeting room. Three paintings created by the artist and his master Hudson, after the manner of Paul Veronese states Timbs, portray ‘the Duke of Leeds, Lord Dundas, Constantine Lord Mulgrave, Lord Seaforth, the Hon. Charles Greville, Charles Crowle, Esq., and Sir Joseph Banks.’ A similar, second group show ‘Sir William Hamilton, Sir Watkin W. Wynne, Richard Thomson, Esq., Sir John Taylor, Payne Galway, Esq., John Smythe, Esq., and Spencer S. Stanhope, Esq.’, while a third is of Reynolds, garbed ‘in a loose robe, and in his own hair.’ Some of the members are depicted in familiar Georgian costume, while others wear dress of a Roman or Turkish flavour. Lord Sandwich, represented in ‘a Turkish costume, casts a most unorthodox glance upon a brimming goblet in his left hand, while his right holds a flask of great capacity.’ A common theme is one of conviviality, according to John Timbs, with many of the subjects holding ‘wine-glasses of no small size.’He goes on:

‘Sir Bouchier Wray is seated in the cabin of a ship, mixing punch, and eagerly embracing the bowl, of which a lurch of the sea would seem about to deprive him: the inscription is Dulce est desipere in loco. Here is a curious old portrait of the Earl of Holdernesse, in a red cap, as a gondolier, with the Rialto and Venice in the background; there is Charles Sackville, Duke of Dorset, as a Roman senator, dated 1738; Lord Galloway, in the dress of a cardinal; and a very singular likeness of one of the earliest of the Dilettanti, Lord Le Despencer, as a monk at his devotions: his Lordship is clasping a brimming goblet for his rosary, and his eyes are not very piously fixed on a statue of the Venus de' Medici.’

This leads us nicely into the Hellfire Club, since some of the pictures, as Timbs points out, ‘remind one of the Medmenham orgies, with which some of the Dilettanti were not unfamiliar.’

The original Hell-fire Club was founded by the Duke of Wharton in 1719 – when Sir Francis Dashwood was only eleven – and lasted only two years.

“Wharton, the scorn and wonder of our days,Whose ruling passion was the lust of praise.Born with whate'er could win it from the wise,Women and fools must like him, or he dies.Though wondering senates hung on all he spoke,The club must hail him master of the joke.”Pope.

Perhaps gossip of the club’s activities reached the young Francis’ ears, or perhaps he merely had a natural leaning in that in that direction; we can only speculate. History records that he inherited his father’s title when still only fifteen, and his fortune with it. He travelled on the Continent, ‘roaming from court to court’ and whether by accident or design, achieved notoriety through his escapades and wild exploits. According to Walpole, the story goes that while in Russia he impersonated Charles XII and in that guise tried to seduce the Tsarina Anne. His ‘outrages on religion and morality’ in Italy led to his ‘expulsion from the dominions of the Church.’ He returned to England and joined the household of Frederick, Prince of Wales. When the Earl of Westmorland (his uncle) was dismissed as Colonel of the 1st Troop of Horse Guards, these events made Sir Francis ‘a violent opponent of Walpole's administration’.

He became a prominent member of the Dilettanti Society, succeeded his friend the Earl of Sandwich as archmaster when he was removed from office for ‘his misbehaviour to and contempt of the Society’, and was an active politician, opposing Walpole’s administration. However, he continued to offend and get into trouble, possessing as he did the heart of a rake, and fell foul of Horace Walpole again when having ‘stolen a great fortune, a Miss Bateman’ while the lover of Lady Carteret. Nevertheless, he was married in December 1745, at St. George’s, Hanover Square, to Sarah, the daughter of George Gould from Buckinghamshire. She was already a widow, having been previously married to Sir Richard Ellis, 3rd Baronet of Wyham in Lincolnshire. Described by Walpole as ‘a poor forlorn Presbyterian prude’, Sarah failed to curb Dashwood’s licentiousness.

In 1755 or thereabouts, he founded the Hell-fire Club, although it was much later when it became known by that name. His home being in West Wycombe, the club was variously titled the ‘Order of Knights of West Wycombe’, the ‘Brotherhood of St. Francis of Wycombe’, the ‘Order of the Friars of St. Francis of Wycombe’ and, most famously, the Monks of Medmenham Abbey, a property leased by Dashwood in beautiful countryside by the Thames near Marlow. A former Cistercian monastery, Dashwood rented the property from his friend Francis Duffield (Geoffrey Ashe, The Hell Fire Clubs) and some or all of the twelve members, including Dashwood’s half-brother Sir John Dashwood-King, his cousin Sir Thomas Stapleton, John Wilkes and Paul Whitehead, spent time there during the summer.

Sir Francis commissioned various expensive renovations, including rebuilding work in a Gothic revivalist style by architect Nicholas Revett. An inscription, coined from the Abbey of Theleme, ‘Fais ce que tu voudras’, was added over the grand entrance. None survive, but it is believed William Hogarth may have painted murals for the club. Beneath the abbey, Dashwood discovered an existing cave. This he had extended into an interconnecting network of such caverns and tunnels, decorating them with various symbols, items and images of a phallic, carnal and mythological nature.

Sir Francis himself presided over club rituals in the manner of a high priest, the so-called ‘Franciscans’ (after their leader) indulging in ‘obscene parodies of Franciscan rites, and with orgies of drunkenness and debauchery which even Almon, himself no prude, shrank from describing.’ According to the Dictionary of National Biography entry by Albert Frederick Pollard, Dashwood ‘used a communion cup to pour out libations to heathen deities’.

In Horace Walpole’s opinion, the club’s ‘practice was rigorously pagan: Bacchus and Venus were the deities to whom they almost publicly sacrificed; and the nymphs and the hogsheads that were laid in against the festivals of this new church, sufficiently informed the neighbourhood of the complexion of those hermits.’

Club meetings took place twice each month and lasted a week or more during June or September for club affairs to be discussed. According to Geoffrey Ashe, members are believed to have worn white ritual clothing of jacket, trousers and cap, while the leader, who changed on a regular basis and was referred to as ‘Abbot, wore matching dress in red. Many are the tales ascribed to the Club and their activities, ranging from devil worship, Satanism and Black Masses to whispers of scantily-clad female ‘guests’ (i.e. ladies of the night), who were alluded to as ‘Nuns’. Feasting, drinking and debauchery were the order of the day for Dashwood’s ‘monks’.

All the years spent travelling on the Continent had clearly had a lasting effect on Sir Francis, for at West Wycombe he had installed in the park a number of statues, follies and temples to various Greek and Italian gods, such as Daphne, Priapus and Flor a, besides those of love and wine. Inspired by the Temple of Vesta in Rome, the Temple of Music is situated on an island in the artificially constructed lake. The Temple of Apollo is now known as the Cockpit Arch because of the cockfights which took place there. Dashwood’s love of the Gothic was apparent here, too, in the boathouse beside the lake and a chapel.

Dashwood did finally ‘settle down’ to a quieter life during his later years. He became the first colonel of the Buckinghamshire militia during the Seven Years War with John Wilkes his lieutenant-colonel; he made a good attempt that year of 1757 to rescue Admiral Byng from ‘political murder’ and later was almost the only peer in the House of Lords to go to the Earl of Chatham’s assistance when he swooned. Sir Francis was made Chancellor of the Exchequer by the Earl of Bute, but lasted only a year after putting excise duty on cider which nearly caused a riot. Having inherited the title of Baron le Despencer through his mother, he sat in the House of Lords and was promoted to Lord-lieutenant of Buckinghamshire. He became comparatively respectable, including being joint Post-master General during Lord North’s tenure, but apparently this did not prevent him siding with his old friend the Earl of Sandwich in a libellous attack on John Wilkes over a bawdy book he had printed. Another publication by Charles Johnstone, states Ashe, featuring stories easily associated with Medmenham Abbey, the Earl of Sandwich and the various iniquities practised by the Hell-Fire members, spelled the Club’s doom. Since many of the ‘monks’ had either already met their own demise or were beyond travelling distance, the High Priest’s orgies were at an end.

After a long illness, Sir Francis Dashwood died at West Wycombe in 1781 and was buried there. His gardens there and the Hellfire Caves he created above West Wycombe are now tourist attractions.

The Beefsteak Club and The Sublime Society of Beefsteaks

Various clubs took the name of Beefsteak or Beef-Steak during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but the one believed to be the first was founded by actor Richard Estcourt, possibly about 1705. It is conceivable it originated through defectors of the Whig Kit-Kat Club and perhaps because of that merited a mention in The Spectator in Number 9, dated 10 March 1710-11:

‘The Beef-steak and October Clubs are neither of them averse to eating or drinking, if we may form a judgment of them from their respective titles.’

Popular, merry and witty, Richard (Dick) Estcourt was made the club’s ‘Providore’ (president) and wore a small, gold gridiron on a green silk ribbon as his badge of office, the gridiron being the emblem of the Beef-Steaks. ‘Humbly inscrib’d to the Honourable BEEF STEAK CLUB’ was the poem Art of Cookery by Dr. William King, who wrote these lines:

‘He that of honour, wit, and mirth partakes,May be a fit companion o’er Beef-steaks:His name may be to future times enrolledIn Estcourt's book, whose gridiron’s framed with gold.’ That ‘…this Club was composed of the chief wits and great men of the nation,’in the words of William Chetwood in A General History of the Stage, is a sentiment repeated by various authors, but it gives an insight into the character of the club and its members.

In the First Edition (1709) of Secret History of London Clubs, Ned Ward offers this description of the club.

‘This new Society griliado'd beef eaters first settled their meeting at the sign of the Imperial Phiz, just opposite to a famous conventicle in the Old Jury, a publick-house that has been long eminent for the true British quintessence of malt and hops, and a broiled sliver off the juicy rump of a fat, well-fed bullock… This noted boozing ken, above all others in the City, was chosen out by the Rump-steak admirers, as the fittest mansion to entertain the Society, and to gratify their appetites with that particular dainty they desired to be distinguished by.’

Nevertheless, in spite of a membership consisting of statesmen and artists, before ten years had passed, the club was discontinued. It was not until 1735 that actor and theatre manager John Rich formed the Sublime Society of the Steaks.

The Sublime Society of the Steaks

Following the success of The Beggars’ Opera, John Rich (not Henry as stated by Timbs) left his position as manager of the Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre and joined the Covent Garden Theatre. A comic actor, he did much to popularize pantomimes and would make models of his tricks in his room at the theatre. Such was his appeal, ‘men of rank and wit’ would visit him there, one being the Earl of Peterborough, who happened one day to be present when Rich cooked a beef-steak on a gridiron over the fire in his chamber. Invited to join his host, the Earl was so impressed that after a couple of bottles of wine, he suggested they meet again at the same time the following week. He brought with him three or four friends, gentlemen of wit and fashion, and the occasion being particularly successful, a Saturday club was proposed, to meet during the Season.

However, as John Timbs warns, there was a club established at Covent Garden named for George Lambert, chief scene-painter at the theatre, who ‘received, in his painting room, persons of rank and talent; where, as he could not leave for dinner, he frequently was content with a steak, which he himself broiled upon the fire in his room.’ These meetings grew into the Beef-Steak Society and later were held in a ‘noble room at the top of Covent Garden Theatre’. During the rebuilding of Covent Garden after the fire of 1808, Timbs suggests the club moved to the Shakespeare Tavern. However, later he says they were ‘re-established at the Bedford Coffee House’. It is not beyond the bounds of possibility that one or two meetings were conducted at the former before removing to the latter around 1809.

Historian of the Society, Walter Arnold, is in favour of a third account of ‘The Steaks’’ foundation, which is that Rich and Lambert dined together on steaks cooked by Rich, and washed them down with a bottle of port ‘from the tavern hard by’. This collaboration then led to the creation of the Sublime Society.

[image error]Beefsteak Dining Room, The Lyceum

Manager Samuel Arnold was responsible for accommodation being provided at the Old Lyceum Theatre (home of the English Opera House from 1816-30), where the club met until 1830, when this theatre was destroyed by fire (one cannot help wondering if this is a coincidence!) Back to the Bedford Coffee House the ‘Steaks’ went; the Lyceum Theatre having later been rebuilt, they were given the use of a dining room there. According to Peter Cunningham, the room was ‘most appropriately fitted up – the doors, wainscoting, and roof, of good old English oak, ornamented with gridirons as thick as Henry the Seventh’s Chapel with the portcullis of the founder.’ The gridiron emblem was much in evidence; some items were shaped thus, table cloths were ornamented with ‘gridirons in damask’ and the plates and wine/ale glasses were decorated with them. Peter Cunningham continues, ‘The cook is seen at his office through the bars of a spacious gridiron, and the original gridiron of the Society, (the survivor of two terrific fires) holds a conspicuous position in the centre of the ceiling. Every member has the power of inviting a friend.’

[image error]Beefsteak Badge

Whatever the Society’s origins (they strongly resisted being termed a ‘club’) the members were a creative order of artists, thespians, musicians and writers. William Hogarth and his father-in-law, James Thornhill, were founding members and David Garrick wrote of Rich (as his stage character, Lun, the first Harlequin) in a prologue to the new ‘speaking pantomime’:

‘When Lun appeared, with matchless art and whim,He gave the power of speech to every limb.Though masked and mute conveyed his true intent,And told in frolic gestures what he meant;But now the motley coat and sword of wood,Require a tongue to make them understood.’

This suggests he, too, was a member. John Wilkes was elected in 1754; Samuel Johnson in 1780 and John Philip Kemble in 1805. Royalty, noblemen, celebrated soldiers and politicians soon flocked to join this renowned group of gifted artists. Indeed, the Prince of Wales became a member in 1785 when the membership was increased by one to admit him. This was ‘an event of sufficient moment to find record in the Annual Register of the year.’

“On Saturday, the 14th of May, the Prince of Wales was admitted a member of the Beaf-steak Club. His Royal Highness having signified his wish of belonging to that Society, and there not being a vacancy, it was proposed to make him an honorary member; but that being declined by His Royal Highness, it was agreed to increase the number from twenty-four to twenty-five, in consequence of which His Royal Highness was unanimously elected. The Beaf-steak Club has been instituted just fifty years, and consists of some of the most classical and sprightly wits in the Kingdom.”

It was not long before the Duke of Clarence and the Duke of Sussex, his royal brothers, were also accepted, as was the Duke of Norfolk. Members wore a blue coat and, beneath it, a buff waistcoat with brass buttons embossed with the ubiquitous gridiron, plus the legend ‘Beef and liberty’. Meetings were held each Saturday between November and the following June – i.e. the London Season – and continued until 1867, when the Society closed its doors. Club dinners were always beef steaks, cooked in a variety of ways, and served with onions and baked potatoes, on hot pewter plates. Toasted or stewed cheese completed the meal, the whole being accompanied by arrack punch and ‘port-wine’. With the table cloth removed and the cook paid, the remainder of the evening was passed in merriment and jollity.

The Society of Eccentrics

There were several clubs called the Eccentrics, beginning in the 1780s and continuing through to 1986. The most famous is no doubt the one which closed its doors in the last century, as it is also the longest-lived, being founded in 1890 and spending most of its years at 9-11 Ryder Street, St. James’s. However, it is the first club in which is of interest here.

The Society of Eccentrics was a branch of The Brilliants and from 1781 met in Chandos Street, Covent Garden, at a tavern belonging to a man called Fulham. In due course, they moved to St. Martin’s Lane, to Tom Rees’ in May’s Buildings, and other Covent Garden venues until the club’s demise in 1846. At some stage in the 1820s, the club’s name was changed to The Eccentric Society Club.

It is reported that the Eccentrics boasted 40,000 members and more from its beginnings, many being from the upper echelons of Society and including politicians and literary men. Some of these were Lord Melbourne, Lord Petersham, Lord Brougham, Charles James Fox and Richard Brinsley Sheridan. Theodore Hook was accepted on the same night as Lord Petersham and Sheridan, and it was believed that some of his ‘high connections’ were achieved through his club membership. Author F. W. N. Bayley, ‘sketched with graphic vigour the meetings of the Eccentrics at the old tavern in May’s Buildings’ in a novel ‘published in numbers’.

The club, apparently, was given to night-time revelries, but the authorities indulged the flights of the celebrity membership. When a new member was inaugurated, a ceremony was carried out, ending in ‘a jubilation from the President’.

According to John Timbs, it seems the early books of The Society of Eccentrics passed into the hands of Robert Lloyd, hatter to the nobility, of 71, The Strand. Known for being an eccentric himself, Robert Lloyd was a philosopher, inventor and the author of a ‘small work’ describing fashionable hats of the era, complete with illustrative engravings.

It is possible that the succeeding clubs, including the present day Eccentric Club UK, may have connections with the original Society. A white owl was the crest of the club in the 1800s and was said to have been adopted by the 1890 version. One source claims Sir Charles Wyndham and other founding members made references to a revival of the earlier club.

Pictures Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

© Heather King

Published on May 29, 2016 13:27

May 14, 2016

HORSES IN ART ~ POWER AND PRESENCE

JOHN MANNERS, THE MARQUESS OF GRANBY BY SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS

In this, the eighth in my series looking at horses in art, I am considering this well-known portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-92). It measures 97” x 82.5” (8’1” x 6’10.5”) or 248 x 210 cm and is an oil on canvas. It was painted circa 1763-5 and currently hangs in the Ringling Museum of Art in Florida, USA.

[image error]The Marquess of Granby, by Sir Joshua Reynolds

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Sir Joshua Reynolds was much in demand as a portraitist, not least because of his remarkable ability to make every one he painted as individual as his subjects. He had an uncanny knack of showing his clients in the best possible light, whether they be a society lady, a devoted mother, a politician or, as in this case, a military leader.

The Marquess of Granby, as a general of some considerable stature, is shown in a suitably heroic setting. The Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in Europe is depicted on the battlefield of Vellinghansen, where a major victory was won, in July 1761, against the French. Behind him, smoke rises from the scene of the battle, adding to the air of military prowess alluded to by the Marquess’ breastplate and general’s uniform. The sky is moody and menacing, enhancing the drama of the work, and even the horse, such an important part of the composition, appears to be surveying the field of success.

The ‘engine’ of the horse is located in his hindquarters, thus this pose accentuates, not only the power of the animal, but also that of the man who controls him. John Manners is not a small man, and his horse is therefore no skinny Thoroughbred racehorse, but a charger of bone and substance, with the strength to carry his master all day. However, that is not to suggest he lacks quality – far from it. The strapping bay is of a type horse aficionados will recognize as a gentleman’s hunter – blood crossed with bone, and often produced in show rings all over the country, from the marriage of Thoroughbred with Irish Draught.

The strength and placidity of the Irish Draught perfectly tempers the quickness and fire of the Thoroughbred, and so this horse again adds to his master’s stature by his own eagerness and readiness to rejoin the battle. Perhaps, too, the groom holding the horse looks nervous, as if he fears he might not be able to keep his charge from doing so.

It is this presence, this very edginess on the part of the horse, which adds to the Marquess’ own power. He leans against the bay’s quarters in an almost nonchalant pose, his head turned away in contemplation. Not only can he control this mettlesome steed in the throes of action, a worthy hero of His Majesty’s forces, he is also a man with loftier concerns, a tactician and leader of men given to mature and considered reflection. The vagaries of his horse’s temperament and the demands made upon his own skill were accepted long ago. His thoughts are for the ‘affairs of men’ and keeping the Gallic threat from English soil.

© Heather King

Published on May 14, 2016 13:55

April 27, 2016

Devil's Hoof ~ A Welsh Boys Novel

Well! What a wonderful party it was last night! Thank you to everyone who came to my book launch for Devil’s Hoof, the first novel in my paranormal shape shifter series, and helped it to go with such a swing. I appreciate each and every one of you.

A huge thank you, too, to my guest authors, Wendy Lou Jones, Janice Preston, Susana Ellis, Jolie Byrne, Zara Stoneley, Annie Whitehead, Regan Walker, Ari Thatcher and Cora Lee. Ladies, you were magnificent!!

[image error]

Blurb

Matthew Swift, Special Forces veteran of the Iraq wars and invalided out of the army following an act of heroism, is struggling to adjust to civilian life. Suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, he is a loose cannon ready to explode, beset by horrific flashbacks and images. If that were not enough, Matt has broken up with his girlfriend and his father is fighting a hostile takeover, in the process hiding a heart problem from his family.

Sparks fly when Matt meets alternative therapist Shani Stevens, but then they become stranded in Rhandor Forest by unprecedented storms and have no choice but to help each other.

Both have scars, yet slowly they learn to trust. Mutual sympathy and understanding soon grow into an abiding passion, but Matt has a secret he cannot reveal…

Amazon UK

Amazon US

Thank you if you have bought it – I hope you enjoy Matt and Shani’s story.

Heather

Published on April 27, 2016 03:21

April 18, 2016

Come Join The Party!

The Welsh Boys

[image error]

I am so excited!! At last my first Welsh Boys novel is ready to fly. (I hope it doesn’t crash land instead.)All my lovely readers and followers, please invite your friends to a virtual picnic in Rhandor Forest, where you never know what you might find!This novel (not telling you the title just yet) is a contemporary paranormal story, featuring shape shifters, but I have some fabulous authors coming to help me celebrate and most of them write historical romance and fiction.

[image error]

Short BlurbMatthew Swift, veteran of the Iraq wars and invalided out of the army following an act of heroism, is struggling to adjust to civilian life. Sparks fly when he meets alternative therapist Shani Stevens, but then they are stranded by unprecedented storms and must help each other.Both have scars, yet slowly they learn to trust. Mutual sympathy and understanding soon grow into an abiding passion, but Matt has a secret he cannot reveal…

[image error]

Don’t miss out. It promises to be the crush of the year!

[image error]

Photos Copyright Heather KingThe Welsh Boys

Published on April 18, 2016 05:16