Heather King's Blog, page 2

March 5, 2021

THE ENGLISH COUNTRY HOUSE ~ The Long Gallery

The Palace of Westminster, Public Domain

If you are reading this blog, then I expect you are familiar with the scene in Pride and Prejudicewhen Lizzie has gone to Netherfield in support of Jane, and is taking a turn about the room with Miss Bingley. Much of the Georgian way of life was geared towards display, whether that be of wealth, the fashionable cut of a gown, a neatly turned ankle, the fine lines of a prized hunter or the spacious dimensions of a room (and often the treasures therein).

The sixty-eight foot Long Gallery at Little Moreton Hall in Cheshire dates from the 1570s and is a feast of Elizabethan carpentry, combining practical construction with ingenious architecture and attractive decoration, even if, as one visitor puts it, it is decidedly wonky! After four hundred plus years, it is entitled to be a bit wonky. Its purpose, as with most such rooms, was to provide somewhere for the house’s occupants to exercise in inclement weather.

Little Moreton Hall, Cheshire, Public DomainNote the Long Gallery on the top floor.

Early though it is, the gallery at Little Moreton Hall does not have the kudos of being the earliest such chamber in England. Derived from the cloisters of the former abbeys and monasteries dissolved by Henry VIII, themselves places of exercise, many were incorporated into the design of such houses as Woburn Abbey and Lacock Abbey and adapted in houses such as Burghley in Northamptonshire, home of the Cecil family and the famous Horse Trials. This is a ‘courtyard’ house, where the gallery actually resembles its forebear, the cloister walk, by adjoining the house. At Thornbury Castle, one walk is attached to the building and three more surround an enclosed garden. There was also an upper gallery here.

Thornbury Castle, Public Domain

Originally, it is likely that covered galleries were intended to connect one part of a house with another, whereas many later ones led nowhere and were evidently purely for exercise. Those at Thornbury led to the church. The earliest of such galleries in a country house is said to be at The Vyne in Hampshire, built between 1515 – 1528 for William, Lord Sandys, Lord Chamberlain to Henry VIII. Measuring seventy-four feet by sixteen feet wide, the gallery was not merely a wide corridor, for it leads nowhere and is lined with beautifully carved linenfold panelling, decorated with crests, arms and devices of Lord Sandys’ allies and relations. It was clearly built for the purpose of walking – and the display of powerful connections! Doctors in the sixteenth century were keen to promote the value to good health of such activity.

In contrast with the panelling at The Vyne, Hardwick Hall was hung with tapestries, and as with most rooms in the house, was of vast proportions (166 feet in length). The costly Flemish hangings – bought from Sir Christopher Hatton’s heirs for over £300, which was a fortune – were used as little more than wallpaper on which Bess hung portraits of family and kings and queens of times past. In 1601, furniture in the gallery included tables covered with ‘magnificent Ushak and Shah Abbas table-carpets’in the large bay windows, a state chair or couch and a few other stools/chairs. Embroidered cushion covers adorn the window seats.

Of course, those of us who enjoy historical dramas will be familiar with the custom of walking the raised paths in the formal gardens rather than the gallery, for many a dramatic scene has been enacted in such surroundings. It is not, perhaps a formal garden, yet one of my favourite P&Pscenes is when Lizzie stands up to Lady Catherine: ‘You have insulted me in every possible way, and can have nothing further to say.’ This was, however, only possible in good weather. Lizzie tramping three miles through the mud was hardly typical in fashionable Society.

Galleries evolved into places not only for perambulation but also for communication – discussion, socializing and display. Hangings and paintings were added to give those walking something with which to occupy themselves, and as the fashion for collecting portraits grew apace, so the gallery became the favoured room in which to hang them. Not only members of the family were acquired – making some difficulties for later generations attempting to curate them. Portraits of friends, as well as men of stature and influence, royalty and even the Emperors of Rome were added to the mix, the idea being that those perambulating could consider the virtuous characteristics of such personalities and be inspired by them. Hmm, I wonder how many did...

In the sixteenth century, many galleries had little or no furniture and little or no adornment in the way of paintings or hangings, for their owners rarely hadthe means. Thus, ornately carved panelling is more often to be seen. At Haddon Hall about the turn of the century, Sir John Manners, Bess’ neighbour in Derbyshire, commissioned oak panelling for his Long Gallery to be carved with peacocks in the frieze, the bird a feature of his family coat of arms. The boar’s head emblem of his wife’s family, the Vernons, plus the rose and thistle to symbolize a union of England and Scotland, are also included.

The Long Gallery, Haddon Hall, Public Domain

On the right of the above photograph, deep bay windows overlook the terraced garden to the south, which must have been a pleasant place to sit and read, sew or gossip. With mullioned windows on three sides as well, the room – as can be seen – is both light and airy. The silvery grey hue of the panelling and the lime-washed plaster ceiling only accentuate this. Smaller than Hardwick at 110 feet long and fifteen feet high, with sunlight dappling the oak floorboards it is a perfect setting for a little fencing or, heaven forbid, the shooting of playing cards for penny points!

Although I jest, long galleries were used for such activities and the inventories of some include such items as early billiard tables, exercise chairs, weighted ropes (similar to a church bell-rope but with a soundless, seventeenth century type of ‘dumb-bell’), skipping ropes, battledores and shuttlecocks, tops and spinning wheels. Some even had enormous shovel(‘shuffle’)boards – tables of immense size, perhaps fourteen feet in length andoften hefted from a single length of oak – for a form of ‘shove-halfpenny’ played with solid brass counters rather than coins.

Gentleman’s Exerciser, Croome Court, Worcestershire (Author)

The style of long gallery lit from both sides was ideally suited to narrow-ranged courtyard houses or tall Jacobean manors, yet did not fit so well with more compact architecture of the late sixteenth century and early seventeenth century. To adhere to the love of symmetry in Baroque architecture, some houses placed the long gallery so that it stretched from the front of the house to the back on the main axial circuit on the first floor, thus providing fine views along avenues of trees and over the rolling parkland of the picturesque landscape. At Croome Court in Worcestershire, the Long Gallery, designed by Robert Adam from 1761 – 6, is similarly positioned but on the ground floor. This apartment has the most beautiful plaster ceiling, and unlike earlier galleries, a central fireplace.

As the function of galleries gradually changed to rooms for gathering and socializing, so chairs and sofas began to appear along the walls. In addition, tables were introduced and then pedestals, on which busts and statuary were set. Thus the entitled could display their acquisitions and wealth for the edification (or not) of their guests. Fireplaces were a part of adding comfort to these rooms. The white marble chimney-piece at Croome was carved by Joseph Wilton and boasts life-sized nymph caryatids. Midway along the opposite wall is a large bay window affording views of the river and park.

The Long Gallery, Croome Court (Author)

The arched niches were created to hold examples of classical statuary and there are marble benches, similar to those one would find in a garden temple of the period, to add to the Neoclassical theme. It is a great shame that, due to the Court’s chequered history, many of the original treasures have been lost. It is a wonderful spacious room where one can imagine the Coventry family gathering and holding balls, recitals or grand dinners. As far back as the early seventeenth century, galleries had been used for music, dancing and entertaining on a large scale.

Long Gallery, Croome Court (Author)

Long Gallery, Croome Court: Ceiling (Author)

A few years later, Robert Adam created what is considered to be one of his finest designs, at Syon House in Middlesex. Completed in 1769, the Neoclassical gallery is a former Jacobean long gallery of massive proportions (136 feet long by fourteen feet wide and high). Relishing the task of managing the long, narrow room, Adam used geometric shapes on the ceiling to give the impression of width, placed motifs shaped like triumphal arches on either side of the chimney-pieces and flanked the bookcases with clusters of pilasters to aid the perspective. Full length windows line the opposite wall, and on both sides of the green-grey marble floor, soft pink, green and gilt chairs and sofas alternate with tables. This was always intended ‘for the reception of company before dinner,’and as a retiring room for the ladies, to read, sew, play cards and games, ‘to afford great variety and amusement.’Sewing boxes and other requisites for such pastimes could be found here.

The Gallery at Hagley Hall in Worcestershire (built 1754 – 60 by Sanderson Miller) occupies the same position as at Croome. It was intended as part of a circuit of public rooms which could be fully opened on grand occasions or partly so (drawing and dining rooms)when the family entertained company. When the family dined alone, they could simply cross the hall from the private circuit to enter the dining room. The saloon, set centrally behind the hall at Hagley, as it is at Croome, links the two circuits of the house. Gradually this position for the saloon became less important and the nomenclature of saloon was removed to a grander room, often in a similar position to that of the galleries of Croome and Hagley. One such is at Saltram House in Devon. In the Gallery at Hagley,fluted Corinthian columns screen either end, beneath two of the pavilions which mark the corners of the house. It boasts a remarkable wooden chimney-piece with a central pagoda, and a pretty rococo ceiling withan elegantchandelier surrounded by a floral wreath. Windows line the outside walls and, as at Croome, the fireplace is central with two doors, one at each end, facilitating the circuit of public rooms. Chairs and tables are placed along the walls and rugs cover the floor rather than a single length of carpet.

By contrast, the long corridor adjoining the Great Hall in the west wing at Castle Howard in Yorkshire is littlemore than avaulted passage, lined with busts on carved pedestals. Designed by Vanbrugh, the gallery leads to the chapel; the statues, busts and sarcophagi were collected by the 4thand 5thEarls of Carlisle in the mid-eighteenth century – on their Grand Tours, one supposes!

Sir John Vanbrugh was also responsible for the design of Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire, in the first years of the eighteenth century. Blenheim is particularly opulent and awe-inspiring, yet also functional if one disregards the fancy skyline. Here, again, the Gallery stretches the length of the west wing,from the front to the back of the house, and in keeping with the rest of the building, is on an enormous scale. The room provided space for the Duke of Marlborough’s vast collection of paintings and also a state promenade to the chapel.

Blenheim Palace, Public DomainNote the column-lined gallery, centre left and the niches containing statues.

One of the last galleries to be built in English Country houses was the one at Chatsworth Housefor the 6thDuke of Devonshire, who had a fine interest in modern sculpture. He turned the original long gallery into an enormous, comfortable library and had a Sculpture Gallery added in a new wing, constructed by architect Sir Jeffry Wyattville, on an axis with it. This meant, if the Bachelor Duke chanced to glance up from his reading, he could see through five sets of double doors, through the ante library, Dome Room and State Dining Room into the Sculpture Gallery and thence to the far end of the Orangery. This provided a considerable promenade in bad weather, so the original provision of exercise came to be melded with the more cultural requirements of later ages. Lit by skylights, the Sculpture Gallery contains many pieces, including the seated figures of Napoleon’s mother, Madame Mère, and his sister, Pauline Borghese, facing each other on either side of a large clock. The clock is made of malachite; the Duke had a passion for all types of stone, and various table tops, columns, plinths and pedestals are made of such coloured stuffs as blue-john, alabaster, rosewood and moss-agate.

Chatsworth House, Public Domain

Nonetheless, as the billiard room took over the role as a place for exercise within the house (and a typically male preserve to boot) and children were increasingly filed away in the nursery, the gallery lost its place as a centre of gathering and household activity. Estate business was conducted in the study or Steward’s Room; the ladies now retired to their feminine amusements in the boudoir and thus the daily life of a country house became segmented... perhaps the beginning, indeed, of the kind of life we live today.

All photographs are the property of the author unless otherwise stated and may not be copied or shared without the owner’s expressed permission.

© Heather King

[image error]January 28, 2021

THE ENGLISH COUNTRY HOUSE ~ The Dining Room

At last, I have time to return to my series about England’s great stately homes. Despite the difficulties of the Covid-19 pandemic, the past year has flown by, so if any of my handful of readers are awaiting the next novel (ha ha) please accept my apologies and hopefully I will be able to oblige ere too much longer.

As can be seen in an inventory of 1601, it was actually Bess of Hardwick who began the first departure from dining in a Great Chamber (or the Great Hall of the Middle Ages). At Hardwick Hall there is a Low Great Chamber, and the Paved Room which adjoins it appears in the inventory as ‘The Little Dyning Chamber’. These were situated on the floor below the state rooms, the latter thus being able to be closed off during the cold Derbyshire winters or when there was no requirement for entertaining on a grand scale. The Little Dyning Room was situated above the great kitchen and reached by a flight of steps, so at least Bess’ food should have arrived hot, unlike the remote dining rooms in the great houses of the eighteenth century. But I digress.

In 1553, while domiciled in Wimbledon, Sir William Cecil noted that he and his family were accustomed to eat in a parlour. This could have been with upper servants, perhaps merely with those women who waited on his wife or purely en famille. On special occasions, he further said, they moved up to the Great Chamber. It is likely this was the most common arrangement during the seventeenth century where houses had a parlour. Nevertheless, in some establishments the parlour was considered an eating room for the upper servants. Indeed, in 1652, the Earl of Bridgewater decreed if any of his servants had been so prideful ‘...as to exalt themselves (without directions therein received from me...) from the table in the hall to the table in the parlour, I expect they should withdraw from that place.’

A gradual change from eating in state in the Great Chamber took place during the seventeenth century as gentlemen came to prefer a more informal atmosphere for meals. Where the parlour was set aside for the upper servants, the Great Chamber was sometimes supplemented or replaced by another room for dining on a lesser scale, situated on the first floor. In 1634, at Donnington Park in Leicestershire, the Earl of Huntingdon’s eating chamber was simply appointed, with no tapestry or rich furnishings, and his Great Chamber was refitted as a bedroom. However, it was more generally the case that the switch was made to the parlour. Thus dining rooms gradually became more important and often, by the early decades of the seventeenth century, one of the most important rooms in the house, with chimney-pieces and ceilings almost as elaborately decorated as those of the Great Chamber. By contrast, parlours were rarely decorated apart from plain panelling. They were certainly not part of the state room ‘circuit’ on the first floor. Folding, gateleg tables – usually oval in shape – were used rather than the large dining table left permanently in the centre of the floor of dining and great chambers, as they could be put away after use, facilitating the space for other occupations. At Knowle House, in the early sixteen hundreds, it is recorded that meals were taken simultaneously in three rooms: the family in the Great Chamber, the upper servants in the parlour and the servants in the hall. By contrast, the Countess of Dorset noted that she and her husband sometimes ate in the parlour, when not entertaining and during the winter.

Said to be the first recorded use of the term ‘dining room’, an inventory of 1677 at Ham House (Surrey) lists the ‘Marble Dining Room’, situated between the Duke and Duchess of Lauderdale’s private apartments and centrally placed on the ground floor. It was named for the original black and white marble floor and had practical, as well as gilt-decorated, leather wall hangings. Leather does not absorb food odours, unlike tapestries. Three cedar tables, oval in shape, were augmented by a dozen and a half walnut chairs; these had caned seats but no cushions – not very comfortable for a long dinner of several courses! Other furnishings include two cedar side-tables, a marble cistern and early examples of the sideboard, later to become an indispensable item of dining room furniture. The paintings of satyrs, goats, panpipes and putti were later reflected by Georgian architects and craftsmen.

Despite its name, and just to confuse scholars and authors of blog posts alike, the Marble Dining Room is, to all intents and purposes, a parlour since it was not included in the grand state circuit of rooms on the first floor. Sir Robert Walpole’s Houghton Hall, however, boasts a Marble Parlour, which is claimed as ‘the first proper dining room in an English country house’, being positioned above stairs among the public rooms. Walpole famously entertained local gentry and his Whig compatriots with (according to Lord Hervey) ‘...beef, venison, geese, turkeys etc...’ and ‘...claret, strong beer and punch...’ at Houghton twice a year. As passionate about his hunting as he was his politics, Sir Robert enjoyed a suite of rooms on the ground floor, containing a ‘hunting apartment’ which included his ‘supping parlour’ and a breakfast room. Doubtless though, the grand entertaining took place in William Kent’s magnificent Bacchic dining room on the first floor, where the ceiling is decorated in gilded bunches of grapes entwined with vine leaves, as are the cornice and above the doors, while fluted Ionic columns (marble on the inside wall) march to greet arched marble recesses on either side of the fireplace, itself ornamented with garlands of vines. Secreted directly behind the chimney-piece is a door giving access to the servants’ staircase, thus providing the most discreet service.

Houghton is a Palladian mansion on the grand scale. Of lesser proportions yet still magnificent, Berrington Hall, set in the picturesque Herefordshire countryside, gives the historical author a taste of the opulence and grandeur of eighteenth century living. Regular readers of this blog will already be familiar with my affection for this no-nonsense red sandstone residence and its glorious, undulating parkland. Owned and built by Thomas Harley, younger son of the 3rd Earl of Oxford, in about 1775, Berrington is a blend of prosaic practicality, comfort and ostentation. A banker, Harley was aware of the value of money, yet also wished (this being the Georgian age, after all) his house to impress. Stunning views may be had of the Black Mountains from the imposing front steps.

Unless otherwise stated all photographs © Heather King and may not be copied or reproduced without the expressed permission of the copyright holder.

Marble is to be found here as well, and greets you as you enter the house, into the magnificent Marble Hall. In keeping with the vogue in eighteenth century country houses, this is a formal and grand apartment in which important callers would have been received, and the floor, elegantly patterned from black, white and grey-green marble, reflects that.

The dining room, as we have already seen, was developing in importance, and at Berrington it is the largest room in the house. With a higher ceiling than other rooms, it was here that Harley hung the full-length portraits of Admiral Rodney, his daughter Anne’s father-in-law, and his other daughter Martha with her husband, banker George Drummond. Both portraits were commissioned from Gainsborough. To think that Thomas Harley retired in his mid-forties too—! The old saying is true – you never see a poor accountant or banker! Sadly, these paintings are long gone, although naval battle scenes celebrating Admiral Rodney’s greatest victories remain.

A former wine merchant, Thomas Harley no doubt kept a more than tolerable cellar, and yet, while the basement kitchen was immediately below the dining room, there was no convenient access as at Houghton or Hardwick. Food had to be brought by the servants from kitchen to table via the back stairs on the other side of the house – a roundabout route indeed. Cold chips – ugh! However, there is an urn-shaped plate-warmer, crafted by the famed furniture-maker, Gillow of Lancaster.

In 1774, the walls were flesh coloured, in the words of Lord Torrington who visited at that time. Subsequently, they were painted the current sage green during the Cawley era. Around this time the door-cases – previously trimmed in gilt – were painted white. The ceiling has a roundel, painted after the style of Baggio Rebecca, of a scene of a feast, said to be based on the Banquet of the Gods by Raphael. The two rectangular panels feature Ceres, goddess of corn, and Bacchus, god of wine.

The fireplace is surrounded by a marble chimney-piece, gifted to Harley by a school chum, Bell Lloyd, in gratitude for the former having saved him from financial ruin. The chimney-piece is described by the National Trust as the finest in the house. Dating from between 1801-4, the decoration is also naval in content, depicting a battleship in full sail, a man carrying a crane (a symbol of vigilance) with a stronghold at his feet, Britannia holding an olive branch plus a so-called Cap of Liberty and, lying at her feet, her shield and trident. Vine leaves add to the Bacchus theme.

Sadly, the dining table is ‘only’ Victorian and the dining chairs are probably Portuguese or from the Portuguese part of Goa. Those remaining chairs were brought to Berrington from Heaton Hall in Manchester which became Council offices. The large sideboard, of Grecian mahogany, dates from 1800-5 and is on loan from Finborough Hall in Suffolk. In addition, there is a large side-table with a mahogany and satinwood veneer, two matching ones of smaller stature and a cellaret, companion to the above-mentioned plate-warmer. Hot water was kept in the urn, in which the butler would rinse glasses. The urn contained a zinc-lined drawer which could be pulled out to form a sink. In the bottom drawer there was room for six decanters.

This Dresden service, c 1840, is decorated in hand-painted flowers. On the side-table is a Chinese porcelain punch bowl, which commemorates Admiral Rodney’s triumph at the Battle of the Saints in 1872. It was given to Berrington by ‘the late Lord Croft’ (of nearby Croft Castle), as of 1997. Dimly, at the right-hand top corner of the view of the table, can be seen the plate-warmer. My apologies for the quality of the photo.

During the eighteenth century, the sideboard or the main table would have been loaded with plate, as seen above, and the footmen, dressed in their finest livery, would have waited upon Thomas Harley’s influential guests. At larger establishments, there would have been many footmen to make a bigger impression on the diners. Each course was brought in by the footmen – and the more lavish the dinner, the greater variety of the dishes presented. Demonstration of wealth was everything to the Georgians. The main meat dish was placed in front of the host for him to carve. For individual requirements, the footmen then took the guests’ plates to the dishes to avoid the confusion of tureens and platters being passed about the table. The butler took up a prominent position by the sideboard, where he could oversee and superintend the smooth running of proceedings and fill or refill wine glasses brought to him by the footmen, washing them when required as already mentioned.

As far as ceremony was concerned, it was generally provided by the assembled guests in the form of toasts. These could be either to the company as a whole or to individuals and as before, the glasses were taken to the sideboard. Occasionally, for a particularly sumptuous feast, an orchestra would be commissioned to play music. Sometimes this was in the dining room itself but more often the musicians were in another room beside the eating chamber. A dessert course usually completed the meal, after which the ladies retired, leaving the gentlemen to their port and tobacco. By the mid-eighteenth century, this custom was well established but its origins are unclear. While it was not mentioned by Samuel Pepys, in 1694 William Congreve wrote, in his The Double Dealer that the women were ‘...at the end of the gallery, retired to their tea and scandal, according to their ancient custom, after dinner.’ Tea and coffee drinking had possibly been made fashionable towards the end of the seventeenth century by Catherine of Braganza, wife of Charles II, who would have known tea in her native Portugal. Portuguese traders had brought tea back from the East Indies in the sixteenth century. In the eighteenth century, tea and coffee had long been drunk after dinner and supper, brewed by the lady of the house herself. An Indian furnace for tea garnished with silver was listed in an inventory of items at Ham House in the White closet of the Duchess of Lauderdale. Perhaps, Mark Girouard suggests, what became an aristocratic institution began with a practical purpose – a short space of time in which the ladies could brew the tea and coffee ready for the gentlemen to come and drink. Whatever the initial reason, the length of time gradually increased – even to a matter of several hours. Indeed, Robert Adam was mightily pleased, in 1778, to embrace the ladies’ retirement as the opportunity for the gentlemen to immerse themselves in political discussion. They did eventually join the ladies though – unless they were cup-shot!

Essentially, therefore, dining rooms were masculine apartments and drawing rooms the domain of the ladies.

The alcove permitting servant ingress at Houghton was further developed in the dining room at Holkham Hall. An arched recess, created for a sideboard, has small jib-doors to either side which lead to the servants’ stairs. In addition, there is a mirrored panel facilitating observance of the table by the butler and footmen even when standing beyond the doors. This recess also gave an opportunity to display to greater effect the gold and silver services arranged on the sideboard. Done in the French style, at Holkham this was known as the buffet. Formal arrangements of hot-house fruits, such as peaches, grapes and apricots, were also set out here.

The dining room at Holkham was a rather austere apartment, being set between the great Marble Hall and the statue gallery – wherein the latter there was room to walk off a gargantuan meal in inclement weather? 😉 The decoration is on a grand scale, in keeping with two huge busts of the Roman goddess Juno and Emperor Lucius Verus, set in two oval niches above the fireplaces. The chimney-pieces provide a touch of food-related light relief, being decorated with the Fox and the Wolf, and the Bear and the Bee-hive fables of Aesop. The dining chairs have leather seats, in a favoured style of the seventeen hundreds, yet the backs are plain; they were clearly intended to be placed against the wall except when in use.

A musical theme was quite often employed by craftsmen in their decoration of country houses. Hunting horns, lyres and panpipes were common motifs used, and in the dining room may have reflected the melodies played in the adjoining room. However, hunting horns combined with spears, muskets, bows and creeping foliage such as oak and ivy garlands rather suggest the forest and hunting – reference, perhaps, to the food served in the room.

Large pier-glasses are to be found in the dining rooms of many stately homes. These are the enormous mirrors, often hung between the windows and positioned with an elegant pier-table underneath. The purpose of these mirrors was to reflect the candlelight about the room. At Felbrigg Hall in Norfolk, eight small oval mirrors are set, two upon each wall in the manner of candle sconces, within plasterwork frames. The effect must have been very pretty, if perhaps, to a modern eye, impractical for seeing what one was eating! It certainly is a pretty room, the pelmet-style decoration above the ‘frames’ repeated over the various portraits, and bronze figures on various prominences, including the mantel-piece. Against the pale lilac walls and pastel flowered carpet, these sculptures (which were actually made of plaster especially for the room) lend a contrast that works perfectly. Beside the fireplace, it is fabulous to see a surviving bell-rope.

Hanbury Hall, in Worcestershire, has two pier-glasses and tables flanking a central window. The dining room is not huge but boasts some splendid Regency furniture, including mahogany sideboard, serving table and side-table, as well as an early nineteenth century porcelain dinner service. Made by Chamberlain Worcester (pre Royal Worcester), the service dates from 1827 and is composed of 84 plates in total, 14 oval plates (4 small, 4 medium, 5 large, one huge platter), 7 sauce dishes and 7 vegetable tureens.

The above serving table has a wine cooler beneath it. The table was adapted in the nineteenth century to hold the plate rack rather than the customary rail.

Unfortunately, I cannot use the photo I took of the sideboard, it is too poor. The mahogany dining table was made by Gillow of Lancaster, measures 4’ x 21’ and seats up to 26, yet will condense to merely four. There is also a server dating from the early nineteenth century which has detail in the style of Robert Adam.

Thomas Vernon was a member of the Kit-Kat Club in London and perhaps, on occasion, he entertained some of his fellow members at Hanbury. The club members were wont to feast on mutton ‘pyes’, named ‘Kit-Kat pyes’ after the club and the pie man who made them, one Christopher Catt (more can be read about him in the articles on the Gentlemen’s Clubs). One day at Hanbury I took this picture of some Kit-Kat pies. I wish my pastry came out as neat as this!

The ceiling in the dining room at Hanbury is interesting because if you look carefully, it is in two sections. This is because it was originally the Lobby and Withdrawing Room of the state apartments which occupied the East wing. Beyond the withdrawing room was the Best Bedchamber with Dressing Room, and at the front of the house was the Great Parlour, now the Drawing Room. Originally, the bedroom was used by Thomas Vernon, the owner of Hanbury, which was an unusual arrangement for the master did not generally have a suite on the ground floor. A wall was removed and the ceiling realigned. The alterations were instituted circa 1830 and kept the two separate ceiling paintings (probably by Sir James Thornhill). The first (the lobby) is of the North Wind abducting Oreithyia, and that of the former withdrawing room appears to show Apollo in his chariot, saying goodbye to Clymene. The plaster panels are carved with oak, laurel and acanthus leaves, and the repositioned, original fireplace is ornamented with beautiful wooden carving dated about 1760.

When it is safe again to do so, I will visit Hanbury and try to take a better picture!

Note the leaves on the carved wooden ornamentation of the fireplace.

At Syon House in Middlesex, Robert Adam designed the Great Dining Room to equal its name. A long, thin chamber, he added screens of Corinthian columns at each end, fronting a pair of alcoves, to make the proportions of the room less intimidating. The central area thus becomes almost a three-way cube, measuring a mere 66’ x 21’ x 21’. Created circa 1763 and classically decorated in white and gold, the dining room does not have a permanent full-length dining table since, at this date, as discussed above, footmen would have brought in folding tables when required. The room was a deliberate nod to Classical Rome, with the ceiling a vista of elegant splendour, being composed of panels enclosing complicated circular patterns, and a domed section with a triple fan of swirling vine-like design. Removed at some point to the drawing room, there was originally an exquisite Moorfields carpet, dated 1769, which reflected the ceiling. The Great Dining Room was the third in the public circuit, contrasting to glorious effect with the stone-hued Entrance Hall and blue-green scagliola in the ante chamber before, then the crimson damask in the Drawing Room, followed by the pinks and greens of the Gallery afterwards. Palladian glory at its best!

As befitting the probable conversation, especially following the ladies’ withdrawal after dinner, many country house dining rooms were decorated with a sporting theme. The finest animal painters of the day were commissioned to produce portraits of favourite hunters – such as at Deene Park in Northamptonshire – soldiers with their famous chargers and, as at Croome Park in Worcestershire, the owner’s favourite hounds and racehorses. At Uppark in Sussex, where the Prince Regent was a frequent guest at the races held in front of the house, the Lewes (Prince's) Cup stands in pride of place on the dining table.

http://www.nationaltrustcollections.o...

By the early nineteenth century, dinner was usually served at 6.30 – 7.00 pm rather than the 4.30 – 5.00 pm of the late eighteenth century or the 2.00 pm of an earlier age. To bridge the increasing gap, luncheon began to be served, often only to the ladies at house parties for the gentlemen were generally off shooting, fishing or hunting. Dinner was the one formal meal of the day; one could even call it a ritual. The guests and family assembled in the drawing room prior to the dinner hour, attired formally or in semi-formal dress. They made a procession in order of rank to the dining room, where the various courses were served with some pomp, involving the best plate and footman service and followed by the ladies withdrawing to leave the gentlemen to their port and brandy. Some distance between drawing and dining rooms was incorporated into house design by architects to permit some procession and so the gentlemen did not disturb the ladies with their smoking and – doubtless – ribald discourse. This sometimes can be seen in the organization of rooms, where matching drawing and dining rooms are placed on opposite sides of either a hall or saloon, the outside façade then made symmetrical in order to maintain a measure of formality. This approach is often seen in those houses of a generally sprawling, irregular plan, and was a system much admired by those owners and architects who preferred symmetry.

While large houses often had a breakfast parlour and morning room which, like the drawing room, were used for informal daytime activities, the dining room remained aloof as a room for dining with some ceremony. It would be many more decades before the dining room became a more general room, yet even in these days of rampant informality, most houses, no matter how modest, have a dining room or designated dining area. Have we almost turned full circle, where the household once again dines in the parlour or Great Hall, otherwise known as the open-plan living room?

© Heather King

July 30, 2020

Caring For The Sick Or Elderly Horse

Since I am currently nursing an elderly pony, it occurred to me that this would be a useful article to write. After all, nowadays we have the skills and knowledge of talented veterinary surgeons to turn to, and a variety of especially formulated feeds with which to tempt a fussy feeder or one with poor dentition. Two hundred years ago, this was not the case.

In the Regency, although the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons had come into being in 1791 as The Veterinary College, London, for many horses medical care and treatment came from either a groom or the local farrier. There are many books of ‘Horse Management’ written by farriers and horsemen of the era, and some of the treatments recommended are nothing short of barbaric, at least to a twenty-first century horsewoman’s eye. For all their strength, horses are, in many ways, fragile creatures and subject to various conditions.

The following comes from a Veterinary Pathology volume of 1804 and is less severe than many:

Stomachic Balls.

Take Peruvian bark in fine powder, eight ounces; grains of paradise in fine powder, two ounces; gentian in powder, Columba root in powder, of each three ounces; honey sufficient to form the whole sixteen of a proper consistency, and divide into sixteen balls.

One of these balls may be given every morning, and will be found excellent for indigestion and loss of appetite.Of the above, honey is the only ingredient I would use for a horse with loss of appetite and debility. However, if the Peruvian bark mentioned is Cat’s Claw, that has anti-cancer properties and is of great use where ‘wastage’ or digestion issues occur from such a cause. Grains of paradise, also known as alligator pepper and Guinea grains, among others, was mentioned by Pliny as African pepper. In the Bake of Nurture, John Russell described grains of paradise as ‘hot and moist’. Whilst warming and soothing in small doses, I’m not sure I would want pepper shoved down my throat if my stomach was ‘off’! Purported to be useful in cardiovascular health, nowadays it is more often used as a condiment. Columba root has a bitter taste and is used to combat anaemia. Forget the bright purple colour, Gentian is a herb renowned for its medicinal properties. Digestive problems such as bloating, heartburn, diarrhoea and loss of appetite are all indicated in the use of Gentian. A word of caution though – herbs can be as strong in their effects as modern drugs and I would not advise their usage without the requisite knowledge or supervision.

Honey, on the other hand, is soothing, antiseptic and provides much-needed nutrition in an easily absorbed form, especially if the horse is debilitated through diarrhoea. Mixed with water and a small quantity of salt, it makes a simple electrolyte solution which most horses will readily drink. It is important to remember that while a horse can survive thirty days without food, he can manage only forty-eight hours without water. Thus it is essential that a sick or debilitated horse has access to fresh water at all times. If exhausted, a drink of chilled water may be offered, which, despite the name, is cold water with a little warm water added to take off the chill. Very cold water can be a shock to the system and even cause colic.

The Regency groom would have regularly offered water to his charges from a wooden or steel pail, since they were too easily kicked over where horses were housed in stalls – and automatic watering systems were a long way in the future! A horse will often wash his mouth without taking a drink, so the water must be changed frequently. Were a bucket of water to be placed beneath the manger, feed or hay would soon foul it. Horses are finicky about their feed and water and will starve themselves sooner than ingest anything contaminated.

There are times when, like a sick person, a horse may be so debilitated he may have lost the will to drink as well as eat. What, therefore, can we do? If holding a bucket up to his mouth will not do the trick, we have to be sneaky. Fair means or foul.If something tempting added does not work (and I am always wary of adding anything to water), then water must be introduced by other means – hosepipe, bottle or cup. I used a well-rinsed squeezy bottle to wash out my pony’s mouth. He would not have appreciated the hosepipe! Lacking either of these, the Regency groom would have made use of anything at his disposal – probably a bottle or cup.

If the horse will eat, hydration can be assisted by giving feeds made into a sloppy mash or even a gruel which the horse can slurp or drink. Nowadays, there are many proprietary conditioning feeds on the market, designed for veteran horses and those with poor dentition. Deciding which to choose can be a problem in itself, and then, when you get a 20 kg sack home and your horse turns up his nose, also an expensive one. I do wish manufacturers would offer small bags too, so a new feed may be ‘run by’ the horse before a big sack bought.

Lacking these scientifically formulated feeds, what did the Regency groom do? Firstly, this might be a good place to remind the historical author to beware of giving their characters twenty-first century sentiment with regards their horses. The horse was a tool, a beast of burden, transport and conveyance of sport, not, on the whole, one of man’s best friends. There are, of course, exceptions to every rule. While he was respected and considered with affection in the case of a favourite, for the majority of animals, if they could no longer work or were severely afflicted, they were disposed of. Once a horse could no longer chew effectively, in most cases it signalled the end. That said, there are traditional methods of preparing feeds to tempt the finicky feeder or horse debilitated after illness.

Above, I mentioned gruel. A true gruel is made from oatmeal, something readily available on any country estate. Oats are still considered the main feed for hard-working horses, especially in the worlds of racing and hunting, despite the myriad compound competition mixes now available to the horse owner. Gruel made from oatmeal is refreshing, palatable and easily digestible. Put a double handful of oatmeal in a bucket, add a little cold water (to prevent lumps forming) and stir thoroughly. Add one and a half gallons of hot water and stir once more. Allow to cool before giving to the horse. Do not use boiling water as this produces a compound which is too starchy for an exhausted or weakened digestion. Of course, there will always be the stubborn individual who will turn up his nose, so what then?

The first food of all mammals, milk is useful to stimulate appetite in the horse, but again, beware! Horses cannot assimilate cow’s milk and therefore skimmed milk, watered down further, should be used, and not too much. I gave my pony small quantities of plain yoghurt, as it is a probiotic and easy to digest, to help stimulate his desire to eat. Since he needed energy, and quickly, I also gave him (half a mugful at a time) porridge made with watered skimmed milk and mixed with molasses. Fair means or foul! I had to spoon-feed him like a baby, but by the afternoon he was nibbling at some chaff and sugar beet pulp my other pony had left. The first rule of feeding is Little and Often, so I fed him at hourly intervals and then 1½ – 2 hours apart. Sugar is another good way to give a horse energy, just as it is with humans. A whole packet of extra strong mints, one after the other, went quite a long way towards lessening his apathy too, I suspect! It was the first sign of enthusiasm and it gave me hope. The latter the Regency groom did not have, nor yet polos, but porridge he could well have made use off.

Once the horse’s desire to eat has been triggered, it is important not to overload the system. Feeds should be soft and easy to eat, just as with a baby. This is where the rules can be set aside – No Sudden Changes of Diet, for instance. The important thing is to get food into the starved or debilitated horse, and while he has evolved to process large quantities of fibre in the form of grass, in this instance he needs nutritious feed high in calories. Back to the expensive search of the feed merchant’s shelves for the modern owner, to find one their beloved charger will deign to fancy. For the Georgian, Regency or Victorian horse, this would have meant bran mashes, with an added handful of oats or barley, molasses, boiled barley or linseed, or cooked, mashed peas and beans. These are not the peas and beans you buy from Aldi (other supermarkets are available); they are legumes with hard shells and must be split, crushed or cooked before feeding. They are very rich in protein, heating like oats and fattening. In a healthy horse, either wintered out at grass or in work where fast paces are not required, one part peas/beans can be mixed with two parts oats, by weight, where grain is fed.

Barley is also a very hard grain and must have the outer shell broken in some way to allow the digestive juices to act on the starch inside. Nowadays, the horse owner can buy micronized barley, which looks like cream-coloured cornflakes. It is steam-cooked and then rolled into flakes, so can be fed straight from the sack or soaked to a mash. In the early eighteen hundreds, it would have been rolled or boiled. Huge pans were set on the stove or over a fire and the barley boiled for two to three hours or until it became soft and pulpy. It makes a horrid, sticky mess of the pan! Alternatively, in this modern age, sufficient for one horse can be made in a crock pot. Cover the quantity of barley with about two inches of water and cook on a low setting for six to eight hours. This can then be added to a bran mash or fed as it is. Oats may also be boiled but absorb a lot of water. The digestive juices are then diluted and the horse becomes fat but also soft in condition. While this is not a problem for our elderly or sick horse, it would be detrimental for the animal in hard work. In the latter case, steaming is better.

Barley, Public Domain

Barley, Public DomainA cautionary note regarding barley and the elderly horse:If fed long-term, the starch levels can become hard to digest where the horse cannot ingest sufficient fibre , either through poor dentition or other issues, and may cause diarrhoea. Boiled grain, or one of the many extruded feeds now available, have the advantage of grinding the cereal and steam heating in a technologically advanced version of pressure cooking, which makes the food more digestible. A well-known British manufacturer makes barley rings, which can be hand-fed if necessary. I said we had to be sneaky! Nevertheless, it is important to ensure the fibre content of the horse’s diet. This can be provided by grazing, hay, haylage or, if necessary, soaked fibre pellets, alfalfa, grass pellets etc. Sugar beet is also a good source of fibre.

Linseed, Public Domain

Linseed, Public DomainAnother useful feed to tempt the appetite and improve condition is linseed. Linseed is highly nutritious, being rich in oils and protein, and gives a gloss to the coat; it is also poisonous to horses as it contains prussic acid, but this is destroyed in cooking. The raw seed must be soaked overnight, more water added and then boiled rapidly for a few minutes before being left to simmer until a jelly forms. When cool it must be fed immediately. Most establishments keep an old pan for the purpose because it makes a dreadful mess of the vessel – and the stove if it boils over, so beware! It also burns easily, so an insulated boiler is best. Linseed tea is prepared the same way but with more water. Very nutritious, the ‘tea’ is added to bran to make a linseed mash (see below).

A bran mash is the traditional feed given to a horse the evening after a day’s hunting or other period of intense activity, and has been so since man first ground wheat to make flour. Easily assimilated, it soothes the digestive tract of a tired horse on high levels of grain. While today we consider this a sudden change of diet and that it is better to halve the ‘hard food’ ration, replacing with hay, if it is a case of persuading a horse to eat, the rule may be disregarded. To make a bran mash more appetizing, a handful of oats, some linseed, treacle or molasses may be added after ‘cooking’.

To make a bran mash:

(Note: A wooden bucket is unsuitable.)

To a metal pail add one third of bran and as much boiling water as it will absorb and half an ounce of salt. Stir well and cover to retain steam and allow bran to cook until cool. It should be crumbly, not wet and sloppy or stiff. Add molasses, oats or a few succulents and feed when cool enough.

When fed dampened or as a mash, bran has a gentle laxative effect; fed dry, it has the opposite effect, so can be used in cases of mild diarrhoea or following a dose of physic.

Here is another recipe from the Veterinary Pathology:

Mild Drink for Pains of the Bowels, Looseness, or Difficulty in Staling.

Take gum-arabic in powder two ounces; dissolve it in three quarts of boiling water; when cold, add tincture of opium, half an ounce, and mix them well together.

This mixture may be given every six hours, in violent looseness, pains of the intestines, or where there is great difficulty in staling.

With opium in there, I should think the horse wouldn’t have a care in the world! As with the modern food industry, where it is used as an emulsifier and stabilizer, gum arabic is a thickening and binding agent, so it is the opium which is the medicament here!

One of the best tonics for a sick or debilitated horse is ‘Doctor Green’. This is a horseman’s term, probably dating from the late nineteenth century, for time at grass. Horses have evolved to eat grass and lots of it. Just an hour a day in the field can be enough to sweeten a jaded appetite and refresh the horse’s enthusiasm for work. For centuries we have kept them in stables for our own convenience (particularly so those belonging to the gentry and aristocracy of a bygone age), yet this can be detrimental to the animal’s well-being. If the horse is too ill to go out to pasture, then walking out in hand, allowing him to nibble on herbs and grasses as he wishes, hand feeding freshly picked grass or chopped roots such as carrots, beetroots, turnips, swedes and mangolds will all assist in recovery. Roots are succulent and add interest, variety and bulk.. Beets were also traditionally fed. Although now required for sugar manufacture, sugar beet pulp, cubes and quick-soak flakes are all available in convenient sacks. All must be soaked before feeding, the time and quantity of water varying with the level of concentrate.

Warmth is essential, for if the horse is cold he will use his energy reserves for heat instead of healing or maintaining weight. This cannot be provided at the expense of fresh air, though. Blankets can be too heavy for a frail horse, so a deep, thick bed must be provided and a thin wool blanket for the Regency horse, held in place by a surcingle not too tightly secured, or a light rug for the invalid equine of the twenty-first century. As remarked above, change the water frequently, because it becomes flat in the stable, in addition to being contaminated by dust, feed or saliva/nasal discharge. Keep mangers or feed buckets scrupulously clean and remove rejected feed promptly. Stale food will not encourage him to eat! If the condition is contagious or infectious, the horse will need to be isolated and appropriate actions taken to prevent spread to other inhabitants of the stable.

A stable with two running horses, James Seymour

A stable with two running horses, James SeymourPublic Domain

Much of the above refers to a horse weakened through fasting or illness. Many of these considerations also apply to the elderly horse. As with people, an old horse can lose appetite for a variety of reasons, including ‘going off’ a particular diet. The old adage, The eye of the master maketh the horse fatis never more pertinent than with the aged equine. A horse’s teeth do not wear evenly. Sharp edges are worn on the molars as the horse grinds his food and must be rasped regularly. Since the old horse dealer’s trick of ‘bishoping’, i.e. filing the teeth to make a horse appear younger, was known in the early eighteenth century, it it likely teeth were rasped for non-nefarious purposes too.

Neglecting the worming of the horse can cause damage which can have long-term effects on the internal organs, causing problems for the veteran. Feeding soft, nutritious feeds when the ability to chew is impaired can prolong the useful life (or happy retirement in modern times) of the individual. Health comes from within, yet keeping the coat well groomed stimulates the production of oils, removes dirt and dandruff from the skin, massages, deters parasites and gives the opportunity to detect wounds, rashes and other skin problems. Lice, in particular, can cause loss of condition and irritability through intense itching. Conditions such as Alopecia can cause loss of appetite, as can an impairment of the immune system, which is common in elderly horses. Afflictions of the pituitary gland like Cushings Disease, Lymphoma and other cancers, and systemic illnesses such as liver failure are just a few more hidden horrors. Be prepared therefore – as would have been the groom of yore, if worth his salt – to adjust, re-evaluate and think laterally in order to restore your sick horse to health or keep condition on your veteran. Above all, whether the horse is ill, debilitated, convalescing or elderly, he must be allowed to rest and enjoy peace and quiet. The groom of yesteryear would have mended and/or cleaned saddlery, or some other quiet occupation, so as to be on hand if his charge had need of him.

The Duke of Wellington’s famous charger, Copenhagen, lived a long and happy (as far as a cantankerous old war horse can be) retirement at the Duke’s estate, Stratfield Saye in Hampshire, where he was well cared for, with a palatial stable and his own field near the ice-house. Despite becoming both blind and deaf, he reached the ripe old age of twenty-eight. He was celebrated, and treated with affection by his illustrious owner. I doubt many of his contemporaries were similarly fortunate.

© Heather King

July 16, 2020

General Care of the (Regency) Horse

'Daily Routine'

Basic horse management has changed little over the centuries. Writing in the early seventeenth century, Gervase Markham recommended that following a half-day’s hunting, the horse should be rubbed until dry, then unsaddled and his back rubbed. Having been rugged up with a rug secured by ‘a surcingle well padded with straw’, he should be given ‘a feed of oats and hemp-seed, the gentlest and easiest scouring for a horse’. Then, before retiring, the horse should again be strapped, watered, fed and mucked out. He also advocated, after a longer day’s hunting, a more powerful purging of rosemary and sweet butter, followed by a warm gruel made up of oats, bran and malt. Approaching two hundred years before the Regency, therefore, the importance of resting – after strenuous work and before a day off – the digestive system of a fit horse, eating large quantities of grain, was recognized if perhaps not fully understood. Nowadays we would consider this a ‘sudden change of diet’ and something to be avoided, but for many years a bran mash has successfully been the traditional feed for horses following a hard day’s hunting, because it is easy to digest. Interestingly, Markham’s hunters were also fed garlic – albeit wrapped in butter rather than in the powder or granule form to be found in many modern equine stores – which only goes to prove the validity of the saying ‘what goes around comes around’.A horse’s basic needs are simple. He requires food, water, a comfortable bed, time to rest, and to be kept clean in order to avoid injury and infection. He is a flight animal and so thrives best with quiet handling, a calm atmosphere and well-fitting harness. Ideally, he also needs some time at grass each day. If we remove the natural ability to roll, graze and exercise, we must provide those requirements in other ways. Exercise is provided under saddle or in hand, grass is provided in the form of hand-pulled or cut herbage or succulents such as apples, carrots, swedes and turnips, and the skin must be kept healthy through grooming. (See section on Daily Routine.)In common with many other animals, the horse is prone to internal parasites. These should be treated every few weeks. Nowadays we use drugs such as anthelmintics, yet the practice of worming is nothing new.The following excerpt illustrates that even in the seventeenth century, Markham was aware of the need to remove intestinal parasites:“Take the leaves of bore, and dry them at the fire till you may crush them to pieces, then mingle them with brimstone beaten to powder, and give it to your horse in his provender, yet very discreetly, as by little and little at once, lest your horse take a loathe to it and so refuse it. This purgeth the head, stomach, and entrails of all manner of filthiness, leaving nothing that is unsound or unclean: it cureth the cold, it killeth the worms, grubs or bots in a horse, and it never abaseth, but increaseth courage and flesh. Therefore it is to be given either to a foul horse or clean horse, but chiefly to the clean horse, because it shall preserve him from any foulness.”From this can be seen that by the nineteenth century, and indeed, the twenty-first, while many advances have been made, much to do with the care of horses has remained the same for hundreds and possibly thousands of years. Veterinary surgeon George Skeavington gives a full description of a typical day in the stables of the early nineteenth century which demonstrates the labour involved for the men caring for a gentleman’s cattle. Here is a taster:

THE GROOM’S DUTYStable hours should be kept with strict regularity; all animals appear to have a knowledge of time; and it may be observed, in many instances, they observe the periods as correctly as we, who have recourse to time-pieces; witness the dog, who, if he is accustomed to receive anything from your plate at meals, never fails to attend at the dinner-hour, though in the intervening time he will be roving a great distance; no wonder that the Horse, which, I may aver is not less sensible… …should know his stated hours; and if he is not attended to, particularly to feed and water at the accustomed time, will be watching and fretting with much anxiety, and oftentimes will call and ask for his food, in such manner, as those accustomed to Horses cannot fail to understand. Regular and stated hours should be punctually attended to, with as little variation, as the season or circumstances may require; five o’clock in summer; but as the days shorten a later hour is admissible, unless Horses are to be ready at an early hour for hunting, or otherwise; in such cases, two hours at least before they are wanted, the stable should be visited: if you do not allow yourself sufficient time, things cannot be done as they should.The first thing to be done on going to stable, after casting your eye round to see if any Horses are loose, cast, or the like, is to rack and feed. The judgement in racking is to give the Horse but little at a time, that he may eat it with an appetite, first clearing out his rack, &c. &c. If a Horse leaves hay that is good and sweet, some cause must be assigned for it, and it must be examined into; sometimes cats will foul the hay, and Horses are very nice in their food, when not kept scanty. If the Horse appears to be in health, and the hay has not been blown on by other horses, but is fresh and sweet, I should judge he is too plentifully fed, and leaving hay for the sake of oats...After having racked with hay, you next feed, as it is termed, that is serving the oats. I proceed in the routine that is to be daily observed; for, were I to treat of things out of this regular order, young hands might be studying what they should do, and what ought to be done first, and it is no uncommon thing to see some, that have been in the stable employment for a length of time, not know what thing to do first, and occasion themselves trouble and loss of time, by going wrong about things. Now, in serving the Oats, whatever is deemed a sufficient allowance for the Horse, for the day, whether it may be three quarterns or a peck, one-fourth of the quantity should now be given: as sweet and clean food is most agreeable to the Horse, as well as beneficial...While the Horses are eating this first feed of corn, which you will recollect is to be given immediately on your entering the stable in the morning, prepare your saddles and exercising bridles ready to take them out; which being all ready and placed on for exercise, give your Horses a few go downs of water; then, if it be an establishment of some considerable extent, give orders to the stable boy to make fair the stable during your absence…The stable being made clean, next commence cleaning your Horses; this is a work that requires more knowledge and judgement than at first appears.The morning’s business of the stable being thus completed, the Horse will require nothing until noon.

This, then, is a reduced description of the instructions for just the morning! It is little wonder that grooms of the Georgian era were men, since they had to work incredibly hard and for very long hours. Those of us who revere the horse, however - even to this day - consider it a labour of love and much to be preferred to stacking supermarket shelves or similar!

You can read more about the daily tasks and routine of the Regency groom in The Horse: An Historical Author's and Reader's Guide.

(C) Heather King Images Public Domain

Amazon UKAmazon US

June 28, 2020

THE ENGLISH COUNTRY HOUSE ~ The Saloon

Generally a room for show and display, the eighteenth century saloon (which bears little relation to the drinking establishments of the ‘Wild West’) and nineteenth century picture gallery began life as the medieval solar before being transformed into the Great Chamber of the Elizabethan mansion. This large room was architecturally grand, being intended as a show-piece for large gatherings and semi-public assemblies of mostly masculine company. A good example of this is the High Great Chamber at Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire, where plasterwork friezes and Brussels tapestries telling the story of Ulysses serve to remind the visitor of the insignificance of the human form. Difficult though it might be for a modern mind to comprehend, given its size, Hardwick was originally built as a hunting lodge. There are ‘banqueting houses’ in each tower, from where the spectacle of the chasecould be observed – the fine gentlemen on their equally fine horses, the vociferous hounds, the beaters, yeoman prickers, archers and hawkers. In celebration of what has long been a favourite pastime of the privileged, Diana and her attendants thusgrace a frieze in the High Great Chamber, setting out on the hunt through a magical green and leafy forest.

Hardwick Hall PD

Hardwick Hall PDGreat Chambers were also used for feasting. In addition to the friezes, Hardwick has representations of the seasons of bounty on either side of the bay window: Spring, her flowers and other plants burgeoning into life, and opposite,the abundance of Summer. Between them stands, as it has done since the days of Bess of Hardwick, the heavy, famedeglantinetable, its marquetry surface inlaid with boards for various dice and card games. In many such Great Chambers justice was also dispensed, taxes and rents collected and service orders issued on behalf of the local militia. Interestingly, although the ‘centre’ of the house in terms of formal ceremony and stewardship, the High Great Chamber at Hardwick is not in the centre of the house but to one side. In the Middle Ages such anomalies were overlooked, but alack of order became less acceptable as architects looked for their designs to follow social precepts.

During the early years of the seventeenth century, the influence of Italian architect Andrea Palladio began to be seen in plans for English country houses. Now known as ‘Palladian’, one of his designsfeatured two large chambers, one above the other, in the centre of the house and smaller rooms then arranged in symmetry on either side. English architects immediately translated this as a central hall with a Great Chamber above, since the master would then be dining above his vassals in central dominion. Unfortunately for the lovers of symmetry, the typical English requirement for grand apartments for important guests and lesser accommodations for family did not easily adjust into this arrangement. However, it did adapt quite well for royal households, and once the advantages of symmetrical apartments for His and Her Majesty were recognized, a balanced arrangement of the two households could not but be the result. The Palladian plan was better suited to this end and soon began to be adopted by those lower down the social scale, leading to the decline of the old English style.

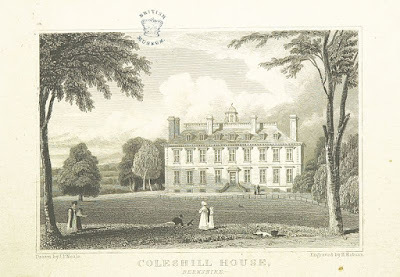

To begin with, the wealthy, with their need for display, could not resist ‘showing off’ the Great Chamber as a state room by the external means of a pediment with carved coat of arms or, better still, a grand portico! However, such conceits came at considerable cost. Around the middle of the sixteen hundreds, gentleman amateur Sir Roger Pratt designed a less ostentatious frontage at Coleshill House in Berkshire for his cousin, Sir George Pratt. Having spent five years on the Continent, he knew how French and Italian architecture was evolving, yet also understood what was required by the English gentry. At Coleshill, he built the house with a basement level. The ground floor then laid symmetrically, with a bedchamber, withdrawing chamber and parlour, all accompanied by inner closets, in three corners and steward’s room in the fourth. This allowed a two-storey Hall with Great Parlour behind, and above that, on the first floor, a Great Dining Chamber. A similar arrangement occupied the four corners, being a withdrawing chamber and three bedchambers with attendant closets. This was an adaptable arrangement, allowing for extra guest accommodation, be it withdrawing room, bedroom or parlour, as required. A long corridor dissected both floors between the Hall and Great Chambers, with back staircases at either end, a simple arrangement which was as yet an innovation. In order to maintain the symmetry, the main staircase was placed in the hall, and thus evolved the change from an eating room to a stately entrance, since it was now unfit for dining. The new style of entrance hallwas also a magnificent ingress for the state chambers behind. Therefore the servants were moved to a servants’ hall beside the kitchen, which, along with the pantry, cellar, stores and offices, was in the basement.Externally, this great central purpose of the housewas shown only by a flight of steps to the front door, a modest pediment and wider spaces between the windows.

Coleshill House, Berkshire PD

Coleshill House, Berkshire PD Staircase, Coleshill House

Staircase, Coleshill HouseCountry Life

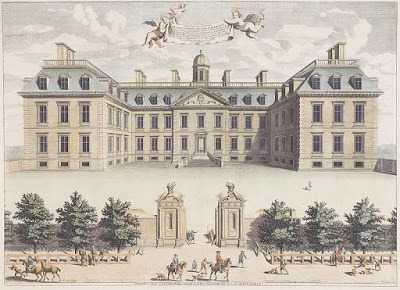

Sir Roger designed three other houses after the Restoration of Charles II. The grandest was in Piccadilly for His Majesty’s first minster, the Earl of Clarendon. Once proclaimed the most magnificent house in England, Clarendon House was built on an H-shaped plan, with projecting wings to each side of a central pedimented bay. Due to the Earl’s position of power and the mansion’s prominent site, the design was imitated a great deal through the remaining decades of the seventeenth century. However, it had more influence on the style of country houses rather than the mansions of London. Belton House in Lincolnshire is perhaps the most celebrated example.

Clarendon House PD

Clarendon House PDMentioned by Sir Roger Pratt in his writings, the saloon evolved from the ‘grand salone’ during thistime. Created by Inigo Jones, the huge Double Cube room at Wilton House in Wiltshire was too gargantuan at thirty feet by sixty feet and thirty feet high to be copied in more than a very few residences, but the carved fruit and flowers on the panelling, the coved ceiling and the framed chimney-piece painting have all become standard fare. Yet, while some Great Chambers – for example, Knowle House in Kent – have elaborate panelling, asthe seventeenth century progressedit became the custom to display large family portraits on the walls in place of the tapestries much used in earlier centuries. (These latterhad a practical as well as decorative purpose, for they helped to protect the occupants from draughts.) Apparently, it was not unknown for peers to have totally imaginary portraits painted of forebears in armour or courtly robes, in the hopes of passing them off as from the Middle Ages.

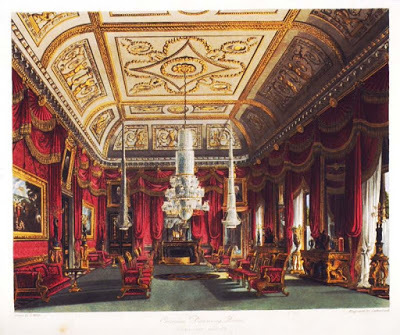

Saloons are not necessarily built on a grand scale. Thelarge chambersofthe end of the sixteen hundreds gradually dwindled insucceeding centuries. As we have seen,, they were often built in the centre of the house, in tandem with the entrance hall, the so-called ‘state centre’ as described by Mark Girouard, withapartments containing bedchamber, dressing room, drawing room and closet occupyingthe house’s four corners. Nevertheless, withthe function of the saloon gradually changingfrom feasting to a picture gallery and reception room forimportant guests, so the panelling and horse-hair covers (chosen for their imperviousness to the odours of food) gave way to rich wall-hangings and upholstery of velvet and silk. Gilt-framed furniture, including pier-glasses, side-tables, chairs and settees, all placed with a nice eye for symmetry, were introduced by William Kent at Houghton Hall for Sir Robert Walpole and very soon were copiedacross England.

At Hanbury Hall in Worcestershire, there is no saloon, but the Great Hall meets the criteria of the Great Chamber. The house bears a nineteenth century stone, with the date 1701, in the centre of its grand Georgian façade, but this could be the date of completion of works most likely carried out for Thomas Vernon, who inherited the estate in 1679. His grandfather, Edward Vernon, acquired the estate in 1631, thus the core of the house is Baroque in style. However, the reconstructed house is built on the E-plan, double-pile or ‘state centre’ arrangement employed by Sir Roger Pratt at Clarendon House. The Great Hall at Hanbury is low and long; the walls arecovered in stained pine panelling arounda wide, black marble fireplace. Opening directly into the hall, on the western side, is adark wooden staircase. Both walls and ceilings above the staircase are painted with scenes (very much in the Baroque style) depicting, respectively, the life of Achilles and an assembly of the gods, the work of Sir James Thornhill. The doorways leading off the hall have arched tops and the ceiling is painted with corner panels representing the Seasons, and trompe l’oeildomes. The eastern circuit of rooms originally formed the ‘State Apartment’ and included the Great Parlour (now the Drawing Room), the Lobby (now the Dining Room), the Withdrawing Room, Bedchamber and Dressing Room.

Staircase, Great Hall, Hanbury Hall

Staircase, Great Hall, Hanbury HallAuthor

Created by Sir Robert Smirke (architect of the British Museum) for the 1stEarl Somers, c. 1812 (opinions vary), Eastnor Castle in Herefordshire is a Gothic revival mansion. Some, not least Charles Locke Eastlake in A History of the Gothic Revival,viewed the house with a jaundiced eye, deeming it ‘a picturesque mistake’as a residence. Indeed, as it was built with ‘exceedingly small and narrow’ windows, the lack of light must have caused considerable inconvenience, especially in the winter months. The castle is large and symmetrical, with ‘round, or rather quatrefoil, angle towers and a boldly raised centre.’(Nikolaus Pevsner) For the purposes of this article, however, the main point of interest lies at the centre of the building. The Great Hall, approached via the main entrance hall, measures up to the proportions of a Great Chamber. Sixty feet long and sixty-five feet high, it reaches up three storeys and has but a single row of windows, high up, decorated with Venetian tracery. On a sunny day, the sunshine blazes down upon carved walnut benches, tables and chairs, designed by Robert Smirke for the house, and the highly decorated walls and furnishings introduced by G. E. Fox in the 1860s. Above the doorway from the entrance hall is a gallery supported on polished columns. Two suits of armour guard the arched doorway into the Octagon Room and, interestingly, given the later function of the Great Chamber as a picture gallery, various portraits also adorn the walls. There is a State Apartment on the first floor, including a bedchamber with walnut canopy bed and wardrobe, and adjoining it, a luxuriously appointed bathroom. It would seem that this variant on the ‘state centre’ was not unusual.

Great Hall. Eastnor Castle

Great Hall. Eastnor CastleAuthor

Great Hall, Eastnor Castle

Great Hall, Eastnor CastleAuthor

Travelling across Herefordshire to the tiny village of Yarpole, we find a real castle that still has connections with the family it was named for. Croft Castle is a large, irregular quadrangle in shape, built in either the late fourteenth or early fifteenth centuries, with some sixteenth or seventeenth century windows, although most are now sashed. The entrance, thought to have originally been a carriage archway into the inner courtyard, is now into a hall, added in about the mid eighteenth century. (The porch is a much later addition of 1914.) While some of the panelling and woodwork is Jacobean and late seventeenth century (notably in the Oak Room) and the Drawing Room has early eighteenth century panelling, most of the furnishings date to the Georgian era, c. 1750-60, when the house was renovated to transform it into a country mansion. It was during this time that the sash windows were added, along with much of the interior decoration, such as the rococo ceiling in the Oak Room, the painted panels in the Blue Room, the painted bookcases in the library and the wonderful Gothic staircase with its stunning plasterwork. The chimney-piece in the Blue Room is also rococo, although the ceiling there is Gothic. There is no Great Hall or Great Chamber, despite the castle’s medieval origins, and although there is a saloon, it is not behind the entrance hall as we have seen before. It is a southern-facing room of fair proportions and adjoins the library, which is situated at the south-east corner of the house. It has a pretty, decorated fireplace, moulded ceiling and frieze, Georgian sofas and chairs as well as gorgeous carpets and furniture. Several paintings – mostly portraits – hang in the saloon, which has doors leading to the Blue Room and the corridor serving the wing. It is certainly a room for entertaining, and it is easy to imagine the carpets being taken up, the chairs pushed back and for dancing to take place on the polished floorboards, as was often the custom in houses of the Georgian era lacking a ballroom or large gallery.

Croft Castle, East Front

Croft Castle, East FrontAuthor

Saloon Fireplace, Croft Castle

Saloon Fireplace, Croft CastleAuthor

Although State Apartments as described above are not in the floor plan of Croome Court in Worcestershire, thepiano nobile(principal floor)constructed by Lancelot Brown does have a state centre. Thesaloon is a light and airy room, set directly behind and leading from the entrance hall via a ‘screen’ of four fluted Doric columns and a cross-corridor that reflects the layout of the seventeenth century. Facingon to the south garden front, where a wide flight of steps are guarded by a pair of Coade stone sphinxes, the saloon has plasterwork painted gold, white and green. The coved ceiling iscomposed of three plain panels (by Francesco Vassalli) and, symmetrically placed on either side of the central doorway, are two fireplaces with fluted Ionic chimney-pieces. Brown was responsible for the understated nature of the decoration, with deep moulded cornices, elaborate mantels generally of Rococo design and, for the most part, unpedimented door-cases also carved on fluted columns. The broken pediment over the saloon door is one exception.

Broken pedimented door-case, Saloon into Hall

Broken pedimented door-case, Saloon into HallCroome Court, Author

Saloon, Croome Court

Saloon, Croome CourtAuthor

Hagley Hall, still home to the Lyttelton family, was also built with a saloon set behind the entrance hall, a corridor crossing between them to east and west staircases (as with Coleshill House), there being two overlapping circuits of rooms, one public and one private. The saloon is now the Crimson Dining Room, but was the start of the public circuit. Owning a fine Rococo ceiling of clouds and cherubs, it also boasted garlands and trophies decorating the walls. Such topics as painting, gardening, drama, music, literature and archery were represented by the trophies. A white and Siena marble chimney-piece surmounted on Ionic columns graced the fireplace and between the windows hung mirrors with stucco frames.