Heather King's Blog, page 3

November 8, 2019

The Draught Horse

Draught horses are heavy horses used for farm work, barge towing and similar tasks. This is a type, covering many breeds, developed from the mighty war-horses, which needed to be strong enough to carry a knight in full armour. The main object in breeding draught horses was ‘…to increase strength, activity, and power, to remove weight, as much as possible, and procure them of the height of sixteen hands, for general utility.’ At the close of the eighteenth century, the finest breeds were considered the Large Black as well as the Suffolk Punch and the Clydesdale. The Cleveland Bay was also viewed as a cart-horse, although it is not so now, being far lighter in build than the ‘heavies’. It is, of course, a superlative carriage horse. Prince Philip used to drive a team of the Queen’s Cleveland Bays, including competing most successfully in driving trials.

Thomas Brown informs us that a Mr. (Robert) Bakewell (of Leicestershire) introduced breeding stock from the Netherlands and produced one of the best horses of the kind which was ever seen, and sent it to Tattersall’s, for the inspection of his Majesty, King George IV.

The head of this individual was light and well set on, his forehand lofty, his shoulder deep, his legs clean and flat-boned, with the general activity of a pony. It was universally acknowledged, that for lightness, cleanness of make, and bulk, he was superlatively excellent. Mr. Bakewell recommended this horse as highly adapted for the purpose of breeding, with appropriate mares, cavalry horses, hunters, and strong hacks. His majesty did not, however, enter into Mr. Bakewell’s views.

The Large BlackThe Large Black was a heavy animal, bred mainly in the Midlands, from Staffordshire to Lincolnshire. There were two types, the Midland or Leicester, and the Lincolnshire or Fen. The Midland was generally a lighter, finer type with greater endurance, while the Fen was commonly heavier with greater bone and ‘feather’ on the legs. Berkshire and Surrey farmers bought them at two years old and worked them lightly to recoup their keep until the age of four, at which time the youngsters were strong enough for sale in the London markets. Retaining sufficient numbers of mares and fillies for work on the farm, the breeders sold the two-year-old colts. Worked in a team of four to the plough by the farmers closer to Town, the youngsters learned to ‘draw’ without suffering exhaustion before being sold for a considerable profit.

These horses in general turn out noble looking creatures; but certainly, from the high feeding and fat produced by the soft food, are not able to compete with the lighter horses used in waggons, which are fed on hard and dry food.

The Irish DraughtThe Irish Draught developed from indigenous stock through imported French and Flemish horses around 1172 when Ireland was invaded by the Anglo-Normans. When crossed with a Thoroughbred, the large, roomy Irish mares produce horses up to weight with strength and bone, good limbs and the ability to gallop and jump over all kinds of country.

The ShireThe Shire, bred in the English Shires, descends from the medieval war-horse known as the Great Horse, which was later named the English Black by Oliver Cromwell. (See the Large Black above.) Flemish and Flanders horses had a big influence on the breed in the sixteenth century when Dutch engineers, involved in draining the fens, brought Friesians with them. This influence continued into the early seventeenth century. The Shire is the greatest of the heavy breeds, both in height and weight, a stallion making as much as eighteen hands and weighing anything over a ton. The name first appeared in the middle of the seventeenth century, with records beginning to be kept, if not fully completed, by the late 1700s. A stallion by the name of the Packington Blind Horse is now accepted as the foundation sire of the Shire Horse breed and is in the initial edition of the Stud Book, published in 1878. He stood in Leicestershire, at Ashby-de-la-Zouch, from 1755 to 1770 as well as travelling about the county as was the common practice in those days. Throughout the nineteenth century, the Shire was in demand for the transport of various commodities from the coast or docks to both city and rural destinations. A commanding, powerful horse, the Shire has a broad, muscular body with a wide chest and legs set well beneath, yet possesses remarkable docility. Colours are generally bay, black or grey.

Suffolk PunchEvery Suffolk Punch can trace its’ descent from one stallion, Horse of Ufford, owned by Thomas Crisp and foaled in 1768. Although it originated in Suffolk, it is now considered native to East Anglia. The earliest reference dates to 1506 and the breed’s forebears may have descended from Viking stock. There are marked similarities between the Suffolk and the Jutland horse. The Suffolk Punch is particularly docile, possesses strength, endurance and longevity, and is a remarkable ‘good doer’. Muscular and powerful, it stands about sixteen hands with a deep, round body. It is short-legged and bears little feather. There are seven accepted shades, but Suffolks are always chestnut.

THE SUFFOLK PUNCH HORSETHIS hardy and excellent breed has become now nearly extinct. They seldom exceeded sixteen hands in height. Their colour was almost invariably chestnut, or sorrel. They had rather large coarse heads, their ears were generally too long for modern taste, and placed very distant from each other, although, in some instances, they were short, pricked, and well-shaped. The carcass was deep, capacious, and compact. The shoulders were wide and thick at top, and somewhat low, with the rump more elevated, from which it is supposed they were enabled to throw so much of their weight into the collar. They were large and strong in the quarters, full in the flanks, and round in the legs, with short pasterns. These horses were celebrated on account of their speedy walking. They also trotted well, and were remarkably sure-footed; and, as draught horses, for steady drawing, and great physical power, might be said to have generally excelled all other horses. In the Sportsman’s Repository, we are told, that “they were the only race of horses which would, collectively, draw repeated dead pulls, namely, draw pull after pull, and down upon their knees against a tree, or any body which they felt could not be moved, to the tune of Jup, Jill and the crack of the whip, (once familiar, but abominable sounds, which even now vibrate on our auditory nerves,) as long as nature supplied the power; and would renew the same exertions to the end of the chapter.” The old Suffolk breed of horses brought very high prices, but of late a larger breed has become fashionable in that county and neighbouring districts, which, for largeness and beauty, certainly excel the old breed. They have been produced from a cross with the Yorkshire half and three-part bred horses of the coach kind, and are particularly beautiful and lofty in the forehand.

The PercheronThe Percheron comes from the region of Le Perche in Normandy. Following the first Crusade in 1096-9, Eastern blood was introduced and by 1760, Arab sires were available at the stud at Le Pin. Mares of the basin around Paris were crossed with Norman, English, German and Danish horses. Sometimes standing over seventeen hands, the Percheron is broad-bodied and very muscular, with a deep chest and strong, hard limbs. The colour is generally dapple-grey or black. No doubt similar horses came to this country with the Normans, for the Percheron has been a war-horse as well as being used for farm work, as a coach horse and for heavy artillery.

The ClydesdaleThe Clydesdale as a breed was not known until the late nineteenth century, when the Clydesdale Horse Society was formed in 1877. It was the first draught horse in Britain to have its’ own society. The first volume of its’ stud book was published the following year, with one thousand stallions listed. However, the breed has its’ origins in the mid-eighteenth century. It is said to have been developed from hardy ‘gig mares’ by the introduction of Belgian and Flemish stallions, the 6th Duke of Hamilton further improving the breed in the 1720s by importing six Flemish Great Horses. At this stage they were known as the Clydesman’s Horses by the local people. The modern Clydesdale stands about seventeen hands, has a kind nature and is active and almost elegant. Dark brown or black, the Clydesdale is renowned for its’ extensive feather, which accentuates the lively paces. It is short-coupled, with legs well set under its’ body and an honest head.

THE CLYDESDALE HORSETHESE horses are strong, active, and steady, generally from fifteen to sixteen hands high, and not unfrequently sixteen and a half hands; and, as horses of husbandry, are perhaps superior to any in the kingdom. The Clydesdale horse is lighter in the body than the Suffolk Punch, and more elegantly formed in every respect, with an equal proportion of bone. His neck is also longer; his head of a finer form, and more corresponding to the bulk of the animal: he has a sparkling and animated eye, and evinces a greater degree of lively playfulness in his general manners than either the Cleveland or Suffolk horses. His limbs are clean, straight, and sinewy. The tread of this horse is firm and nimble: he is capable of great muscular exertion, and in a hilly country is extremely valuable. He is a very hardy animal, and can subsist on almost any kind of food. The equanimity of his temper, and steadiness of his movements, peculiarly adapt him for the plough. Not being too unwieldy in his size, he is no burden to the soil, while a pair are equal to the task of drawing a plough through a full furrow, with great ease. The horses of Clydesdale are not only celebrated on account of their value for agricultural purposes, but are also adapted for the saddle, and useful as carriage horses.

The Dray HorseTHE DRAY HORSETHE Dray Horse should have a broad breast, a low forehand, deep and round barrel, with broad and high loins, and ample quarters, and his shoulders ought to be thick and upright. The forearms and thighs should be thick, the legs short, the hoofs round, with the heels broad, and the soles not too flat. These horses are frequently seventeen hands high, and upwards; and, from the slowness of their movements, are only fit for the drays and slop carts of the metropolis. This variety is better adapted for show than great physical power. With their fine harness, and sleek carcasses, they are particularly qualified to gratify the vanity of their owners. But the plea urged by those who use them is, that their great bulk fits them better for the shafts of a dray, in the ill-paved streets of London. Certainly they are to be pitied, for they suffer sad jolting, and many hard blows against their ribs from the dray shafts; and it must be admitted, that a light horse would be upset in so ponderous a machine, where the streets are so irregular.

Clydesdale Horses (Public Domain)

Clydesdale Horses (Public Domain)Notes from The Horse: An Author's and Reader's Guide, with italicized sections from Captain Thomas Brown's Anecdotes, 1830.

Amazon UK Amazon US

The content of this blog is the property of the author and may not be shared or republished without their expressed permission.

(C) Heather King

Published on November 08, 2019 10:25

October 27, 2019

Points and Conformation

Full of fire, and full of bone,All His line of fathers known;Fine his nose, his nostrils thin,But blown abroad by the pride within!His mane a stormy river flowing,And his eyes, like embers, glowingIn the darkness of the night,And his pace as swift as light.—Look around his straining throatGrace, and shifting beauty float!Sinewy strength is on his reins,And the red blood gallops through his veins.—Barry Cornwall

While it is recommended that study is made of equine points and anatomy in any of the hundreds of excellent text books available, here are a few of the most important for description, along with a brief explanation. The following terms will be understood by the modern equine aficionado and while most have not changed much in centuries, it must be remembered that the horse-masters of yesteryear would have had different phrases.

Gervase Markham, Way to get Wealth, 1695:“Now for the choice of the best Horse, it is divers, according to the use for which you will employ him, if therefore you would have a Horse for the Warrs, you shall chuse him that is of a good tall stature, with a comly lean head, an outswelling forehead, a large sparkling eye, the white whereof is covered with the eyebrows, and not at all discerned, or if at all, yet the least is best; a small thin ear short and pricking; if it be long, well carried and ever moving, it is tolerable; but if dull or hanging, most hateful: a deep neck, large crest broad brest, bending ribs, broad and streight chine, round and full buttock, with his huckle-bones hid, a tayle high and broad, set on neither too thick, nor too thin; for too much hair shews sloath, and too little too much choller and heat: a full swelling thigh, a broad, flat, and lean leg, short pastern’d strong joynted, and hollow bones, of which the long is best, if they be not wier'd, and the broad round the worst.”

Author Note: The above is as published apart from an alteration of the uncrossed f to s for clarity.

Points of the Horse

Points of the Horse Image © Heather King

1. Ears2. Forelock – 17113. Eye4. Nostril5. Muzzle – c14106. Chin Groove – chin OE7. Cheek Bone8. Cheek9. Jugular Groove – jugular 159710. Windpipe – 153011. Shoulder – OE12. Point of Shoulder13. Breast – OE14. Forearm – E1815. Knee – c145016. Cannon Bone – 1834, probably in figurative use prior (see shank, 35)17. Fetlock – c1325; fetterlock 158718. Pastern – 153019. Wall of Hoof – hoof OE20. Heel – OE21. Ergot – horny growth at the back of the fetlock joint, L1922. Splint Bone – 170423. Tendons – 154124. Elbow – 160725. Chest – LME26. Ribs – OE27. Belly – c144028. Flank – LOE29. Sheath – 155530. Stifle – c132031. Thigh – c130032. Gaskin – 165233. Hock – 154034. Chestnut – horny growth on inside of leg below knee, 185035. Shannon or Shank – shank OE36. Coronet – earlier, crown 1611, crownet 1616-35, or cronet 172537. Point of Hock38. Tail39. Point of Buttock40. Dock – 134041. Rump – 153042. Point of Hip – OE43. Croup – c130044. Loins – 139845. Back46. Withers – 158047. Mane – OE48. Crest – 159249. Neck 50. Poll – 1382

Some Useful Words For Describing Horses · Cannon – the main bone of lower legs. It is the circumference of the fore cannon below the knee which determines the weight-carrying ability and strength of the horse. A horse with a measurement of seven to eight inches is said to have good bone.· Coronet– the demarcation point between the hoof and leg, from whence the hoof grows.· Crest – the upper curve of the horse’s neck. In a stallion can be particularly well developed.· Croup – the point just before the highest point of the hindquarters, behind the saddle.· Dock – the bone in the tail; hence the term ‘docking’, whereby a portion of the tail was amputated. It has been illegal since 1948, but was prevalent among harness horses at the beginning of the eighteenth century.· Fetlock– the ‘ankle’ joint, just above hoof.· Forelock– not to be confused with the above. This denotes the section of mane which flops forward between the ears.· Gaskin– the second thigh, the powerful muscle between the hock and the thigh, which joins the leg to the buttocks. Good gaskins mean the ability to gallop and jump – necessary in a good hunter.· Hock – the large, angled joint halfway up the back leg. Good hocks are important as they provide the thrusting power when galloping and jumping. Should be in direct line with outer curve of buttock and thus set beneath the horse’s body.· Knee – the large joint halfway up front leg.· Loins – a weak area of the back, directly behind the saddle and in front of the croup. The kidneys are situated below.· Pastern– a point below the fetlock joint. Should be sloping to provide a comfortable ride, but too much angle makes them weak and prone to strain.· Poll – the point directly behind the ears. Should a horse be struck, or strike himself, hard enough directly on this area, death can be instantaneous.· Rump – the main muscled area of horse’s bottom.· Stifle– the joint at the junction of hind limb with body, equivalent to the knee in humans.· Withers– where the base of the neck joins the shoulder and becomes the back. A hump of bone, more pronounced in Thoroughbred types, marks the place where the saddle fits. Saddles are arched to accommodate the horse’s shape, although in the nineteenth century they were much flatter than they are today. Much pain must have been caused where they failed to fit.

Read more: The Horse: An Historical Author's and Reader's Guide

Amazon UK Amazon US

© Heather King

Published on October 27, 2019 13:01

September 25, 2019

Some Regency Phrases

Greetings, everyone. Apologies for having been quiet lately, but this is why:

In her famous novels, Georgette Heyer employed many cant and lower class expressions, as used by gentlemen of the time. These were culled from the speech of pugilists, coachmen, ostlers, grooms and the racing fraternity. The Regency journalist, Pierce Egan, a fine exponent of sporting cant, was one of Georgette Heyer’s principal sources through the medium of his book Life In London.

Horses · A screw– a very poor quality horse.· A sweet goer– a horse which is responsive to the rider, with a light mouth and smooth way of going.· Beautiful stepper – a quality horse which moves with a smooth, fluent action.· Blood cattle– horses with good breeding. Generally Thoroughbred.· Bone-setter– a commoner or horse of poor quality/action.· Cattle– horses.· Feeling his oats – feeling frisky, full of energy.· High-stepper– horse with a showy action which looks ‘flashy’ but is usually uncomfortable and inefficient.· Prime bits of blood and bone– best quality horses.· Short-stepper– short-striding horse or pony for fast travelling in harness; can jolt the carriage, giving an uncomfortable ride. Equestrianism · Bottom – a horse is described as having this when he has courage and stamina.· Drives to an inch – skilful driver who is very accurate.· Fettling the prads – grooming, tidying or making ready the horses.· Hunt the squirrel– the dubious pastime of following close behind a carriage, then shaving the wheel on the way past. Many a victim’s carriage was overturned by this dangerous practice.· Kick over the traces – when a horse gets its’ leg over the traces (part of harness) it can kick with more freedom.· Likely to throw out a splint– prone to going lame from injury (strain or knock) to the splint bone, a slender bone in the foreleg which runs alongside the main cannon bone.· Neck-or-nothing– from the hunting field, meaning someone who will brave any fence, or take on any challenge. A rider, male or female, who is daring and bold.· Spring ’em – to set the horses quickly into their collars and into a gallop.· [The lady] will give you as good a run as Reynard – the lady will be as brave and wily as a fox on the hunting field.· Throw one’s heart over a fence – to ride with commitment to a fence so the horse will jump.· To part company– to fall off the horse.

This is just one section in my new book on the horse for authors, readers and horse lovers alike - the perfect Christmas gift!

The Horse: An Historical Author’s And Reader’s Guide is mainly aimed at those interested in the Georgian/Regency era, although it covers a wider historical period, including the development of various equine breeds and short histories of equestrianism, racing and racecourses already in existence. It is a fascinating journey through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, packed with information vital to the historical author and of interest to any reader with a passion for horses. Bowling along the major routes, past picturesque coaching inns, we visit racecourses and other places of pleasure whilst meeting a rogue or two along the way.

Volume I will give the reader an insight into the way horses were treated, regarded and worked, their care – including ailments and methods of treatment when ill – and essential terminology.

The Horse: An Historical Author's and Reader's Guide is available in Kindle now and the paperback will be available soon.

Amazon UK Amazon US

It really throws me out of a book when the horse stuff is wrong, so I hope those historical authors who don't know their forelock from their fetlock will find it useful!

All the best,

Heather

Published on September 25, 2019 04:28

June 4, 2019

EAST NOR WEST FOR A DAY OUT

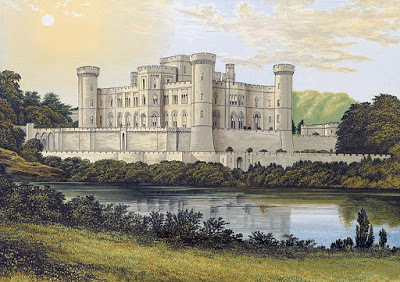

Eastnor Castle c. 1880, Morris

Eastnor Castle c. 1880, MorrisCourtesy Wikipedia Commons

’Twas the start of Half Term and Bank Holiday Monday to boot. Susana, Lady Ellis, and I, escorted by my two faithful hounds and a large picnic, set off for Eastnor Castle in Herefordshire. ’Tis not a real castle, you understand, but a revival or mock Gothic fortress, and lies in the feudal village of Eastnor, two miles outside the market town of Ledbury.

A fortified house in the Norman style, with towers and turrets at each corner around a central keep, it was built by John Cocks, the 2nd Baron Somers (later the 1st Earl) between 1810 and 1824, according to the Castle web site. The date is variously recorded as 1810, 1812 and 1814; one article cites 1812 – 20. Designed by Sir Robert Smirke, the architect of the British Museum, it contains a wealth of historical treasures and artefacts, including paintings, tapestries, armour and carved walnut furniture.

The Cocks family arrived in Herefordshire in the late sixteenth century and bought the Manor of Castleditch, going on to purchase more land round about during the next two hundred years. Marriage between the Cocks family and the Somers family of Worcestershire improved their fortunes further, John Somers, the 1stBaron and Lord Chancellor of England, passing to his descendants a considerable inheritance. Then, at the start of the eighteenth century, the 1stEarl Somers sold his father’s estate near Evesham and the funds from this, in addition to those acquired from the Cocks Biddulph bank (now a part of Barclays) put him in the financial position he needed to build Eastnor Castle early in the Regency. Described as a ‘princely and imposing pile’ when it was built, the mansion cost £85,923 13s 11½d, and took 4,000 tons of stone, 16,000 tons of mortar and 600 tons of wood in the first eighteen months alone! Iron was used for roof trusses and beams to save money. Being a family respected in the fields of politics, the law and the army, an estate in keeping with their social standing was deemed de rigueur. Being a canny individual, the 1st Earl married the daughter of celebrated (and wealthy) historian Rev. Treadway Russell Nash, and thus further increased the family coffers.

The mansion was built as a sign of the family’s status in defiance of the reverses, adversity and concern caused by the war with France. Basically, Lord Somers was cocking a snook at Napoleon and the establishment, although the house possesses a stern symmetry in keeping with the family’s talents rather than the sprawling splendour of the earlier and more romantic Smirke design at Lowther Castle in Cumbria for the Earl of Lonsdale. Nevertheless, it has not been universally approved. In A History of the Gothic Revival, published by Longmans, Green & Co. 1872, Charles Locke Eastlake wrote a somewhat scathing report of the architecture:

“It is a massive and gloomy-looking building, flanked by watch-towers, and enclosing a keep. To preserve the character at which it aimed, the windows were made exceedingly small and narrow. This must have resulted in much inconvenience within...” he said, and went on, “…The building in question might have made a tolerable fort before the invention of gunpowder, but as a residence it was a picturesque mistake.”

Eastnor Castle from the Lake Walk

Eastnor Castle from the Lake WalkThe house has remained in the ownership of the Cocks family since the Regency and is occupied today by descendants of the 6th Baron. As James Hervey-Bathurst and his family reside in the castle, it is only open to the public at certain times during the summer. Perched on the hillside above a shallow valley, the house enjoys wonderful views towards Midsummer Hill and Hollybush Hill, both part of the famous Malvern Hills. Below the castle is a pretty lake (one can easily imagine Mr. Darcy diving into it!) which sparkles in the sun before a backdrop of woodland, set within a three hundred acre deer park. As the visitor faces the front entrance, to the right lies an Arboretum, around which one can walk. There is a tree hunters’ trail, a kind of ‘I Spy’, much enjoyed by children of all ages, as evidenced by the number of eagerly brandished clipboards and pens.

Those of a more mature disposition (and of energetic pooches) can go a little further afield and seek a modicum of peace on a Bank Holiday by walking paths in the woods, circling the Arboretum to visit the Ice House before following the path around the lake. The Arboretum walk takes 20-25 minutes and is moderately hilly, while the lake walk is level and takes 30-40 minutes. A fairly decent walk can thus be found for the sprightlier canine within easy reach of the castle. There is also (joy for the dog owner!) an off lead area to the left of the maze near the entrance from the car parks.

Unlike most country houses, Eastnor Castle welcomes dogs into the castle itself and gains a dozen Brownie points from this author for doing so. Although there is not a lot of space for two large hounds when the whole of Herefordshire seems to have chosen the same day to visit, it is wonderful not to have to miss out or rush back to the one left outside holding the ‘babies’. I did feel, however, a few more signs indicating walks around the grounds would have been helpful, since the plan was not particularly clear – and I am a competent map reader. I resorted to following my nose and it all turned out happily. I daresay it is a question of once you have been a time or two, you know where to go.

As remarked above, the day we visited was Bank Holiday Monday, and there was a traction engine display in the forecourt before the main entrance. This was noisy and there were a lot of people, so it was difficult to linger and properly absorb all the architecture and, within the mansion, the furniture &c. Nevertheless, there was much to see and enjoy.

A flight of steps leads the visitor into the Entrance Hall, where another, red-carpeted staircase rises to the Great Hall. Along with early Gothic style benches and chairs, designed by Robert Smirke for the house, and medieval armour collected by the family in the late nineteenth century, the Entrance Hall contains portraits of John Harrison Cocks Jnr., the 1st Earl Somers, and the 12th Earl of Shrewsbury (later Duke), Sir Godfrey Kneller.

The Great Hall measures 16m x 8m and is three storeys high. Sunlight blazes in from windows high above and reflects on the highly decorated walls and furnishings introduced by G.E. Fox in the 1860s. The marble columns in the gallery were also added at this time. However, carved walnut furniture is still much in evidence in accordance with Smirke’s original plan.

Three doors lead off the Great Hall, to the Staircase Hall, the Red Hall and the Octagon Room. The tour moves into the Red Hall, from which the State Dining Room is situated at the front of the house. Unfortunately, because of the crush of visitors, we were not sure quite which way to turn from here and missed the Dining Room. That would seem an excellent excuse to return!

The Great Hall

The Great HallThe Red Hall is lit by high, leaded windows and is dominated by a fabulous knight on horseback, armour rich in red and gold, and bearing the Italian arms of the Visconti family on his shield. The room also contains an eighteenth century Dutch clock, an Elizabethan sea chest, fourteenth century Austrian pavises (shields used to protect crossbowmen when reloading) and mid-nineteenth century armour from Northern India.

Knight's Armour in the Red Hall

Knight's Armour in the Red HallThe State Dining Room measures 11m x 7m and looks incredible from the picture. It has deep blue walls, covered in gilt-framed portraits with half panelling below, a marble fireplace and a ceiling decorated in gilt panels to reflect the paintings. This was done in the 1850s, the panels containing crests of families with some connection to either the Cocks or Somers lines. A large gilt and glass chandelier hangs in the centre of the room, above a long dining table with at least a dozen carved walnut chairs. The latter, along with benches and fire screens, are part of the original design for the castle. A sideboard graces the end wall and appears also to be walnut. The dining table is original and is made of Cuban mahogany. Robert Smirke designed the room with Gothic arches at each end and over the doors, but these were removed in 1933. The ceiling decoration reflects these in a complicated design in blue and gilt.

Returning to the Red Hall, the circuit continues with the Gothic Drawing Room. An imposing apartment, the drawing room is 11m x 7m and remains much as it was when redecorated in 1849 for the 2nd Earl. A.W.N. Pugin designed the decoration, including the desk, table, chairs and bookcase, the work being executed by the Crace Brothers. A large and highly ornate fireplace by Bernasconi is topped by a colourful representation of the family tree and has tiles by Minton and firedogs by Hardman of Birmingham. The latter was also responsible for the beautiful chandelier, which was put on display at the Great Exhibition in 1851. A grand view of the lake can be obtained from this room.

Gothic Drawing Room

Gothic Drawing RoomThe Octagon Salon comes next, boasting large pier glasses and three fine floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking the Upper and Lower Terraces, with the lake beyond. An octagonal table with a carved edge stands in the centre of the room while rich, red Regency chairs and a sofa grace the walls and sit before the centre window. More portraits adorn the walls, including Lady Henry Somerset, her sister Adeline, later the Duchess of Bedford, and their father, the 3rd Earl Somers. The carpet was made in 1994 to replace one of a similar design to those in the Long and Little Libraries. The ceiling is divided into panels of a geometric design in gilt, cream, black and red lines.

Sofa in The Octagon Salon

Sofa in The Octagon Salon

After this we moved on to the Long Library, which is definitely a room with, in modern parlance, a wow factor. Four windows adorn the right-hand wall and bookcases line the opposite side of the room. The inlaid woodwork and shelves were made in Italy and built in situ by workmen on the estate. Between the bookcases sit two carved fireplaces and above hang tapestries dating from the seventeenth century. These depict scenes from a poem written in honour of Catherine de Medici, while between the windows more tapestries show scenes from Classical Mythology. Two chandeliers are suspended from the ceiling, which is decorated with symbols representing virtue and vice.

Long Library

Long LibraryFrom the Long Library the visitor passes into the Little Library, currently home to a large billiards table (sadly dating only from the twentieth century) and a lovely Regency score ‘board’. Apologies for the photograph; against the light from the window, it is rather less than great, but as few still exist, one hopes it gives the reader of this article some idea of what such scoring systems looked like. Done in shades of blue, the room boasts a large looking-glass above the fireplace and some lovely walnut furniture, including seventeenth century bookcases from Siena. Redecorated in 1990, the walls are covered in a fabric specifically reprinted by Watts of Westminster to a Victorian design. More portraits hang above the bookcases and a bay window opposite the fireplace gives another view over the lake.

Billiards Score Board, 1800s

Billiards Score Board, 1800sThe Staircase Hall may not be to all tastes, for modern sensibilities are often offended by mounted animal horns, an elephant’s foot and stuffed birds in glass cases. However, it is through the Victorian thirst for exploration that we know so much about various species of fauna and flora. It is not the object of this article to discuss the rights or wrongs of such artefacts. The walls are hung with several sixteenth century tapestries, the largest depicting the meeting of Cleopatra and Mark Anthony. There is a set of three tapestries from Bruges, showing biblical scenes of Judith, Susannah, and Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. The benches and chairs date from the seventeenth century, and the chandelier, also of wood, was acquired from the Palazzo Corsini in Florence.

Staircase Hall

Staircase HallAt this point, we went up the Smirke-designed staircase, with its cast-iron banisters and deep red carpet. However, the ground floor tour completes with the State Bedroom, accessed from the Staircase Hall and thence back to the Great Hall. The State Bedroom was the 3rd Earl’s bedchamber and is a very grand apartment. A carved walnut, canopied bed greets the eye immediately one enters the room. Hung with rich red and blue-grey hangings, the bed appears fir for any visiting dignitary, even the King. Of Italian workmanship, it dates from the seventeenth century and belonged to Cardinal Bellarmine, now Saint Robert. A large wardrobe and chest of drawers are also seventeenth century and come from Genoa. Above the fireplace is the motto of the Cocks family, ‘Hope Knows No Defeat’, in Latin. Wall hangings were created by the Royal School of Needlework, while two paintings, The Last Supper and The Birth of Christ were produced by disciples of Jacopo Bassano and Tintoretto respectively.

State Bedroom

State Bedroom State Bedroom

State BedroomAdjoining the State Bedroom is a Victorian-era bathroom, complete with white enamel bath in the centre of the room, the taps on standing pipes through the floorboards!

State Bathroom

State BathroomSeveral rooms are open for viewing on the first floor, most from the doorway. There is a wealth of interesting items, from portraits and clocks to canopied beds of various design, tables and other furnishings. One room contains a small chapel with stained-glass windows and a decorated screen. Another, far smaller bathroom than that pictured above contains a commode fitted against the wall and a free standing child’s version. A gallery of portraits face on to the Great Hall.

Child's Commode

Child's CommodeMuch of what the visitor sees today is due to the hard work of the Hon. Elizabeth Cocks Somers and Benjamin Hervey-Bathurst, parents of James Hervey-Bathurst, the current owner. They came to Eastnor in 1949, inheriting dry rot, empty rooms and a succession of repairs which had been left untended for many years.

Although the family’s fortunes had flourished in spite of the huge expenditure incurred by the building of the castle, their prosperity was not to last. Although owning over 13,000 acres, Reigate Priory in Surrey and Somers Town in London (gifted to Lord Chancellor Somers by William III), the latter years of the nineteenth century proved the family’s downfall. Having an income from agriculture proved almost disastrous when the depression of the 1870s hit the country. The earldom became obsolete in 1883 and by the time the 6thBaron Somers inherited, the castle’s art collection had been divided between he and his cousin, and much of the land sold. The family moved to Australia when he was appointed Governor of Victoria in 1926, and Eastnor Castle was closed up. They returned in 1931 and made use of some rooms, evacuating eight years later so the house was available to the Government during the war. All the contents were removed, although in the end it was never used. Between 1845-9, Lord Somers’ widow returned to live in the servants’ wing after death duties left her almost ‘without a feather to fly with’.

When repairs began in 1949, they were funded partly by income from the estate and partly from the sale of artefacts. Grants from both the Government and English Heritage have restored the battlements of the corner towers following storm damage in 1976 and helped pay for other outdoor renovations. James Hervey-Bathurst and his family continue the work by offering the mansion as a venue for weddings, conferences and corporate entertaining, in addition to opening their heavy wooden doors to the public.

I am sure you will join Lady Ellis and I in wishing them joy of their endeavours and the very best of good fortune for the future.

Heather King

All photographs are the property of Heather King unless otherwise stated and may not be copied or downloaded without the expressed permission of the owner.

Published on June 04, 2019 11:31

April 25, 2019

Easter Sale!

Lovely readers, as a thank you for the support, both of my blog and my books, I have an Easter gift for you.

ALL my digital books are on sale price of £0.99 in the UK and the equivalent elsewhere ($1.29 in the US) so why not pop over to Amazon and give yourself a late Easter treat which won't go straight to your hips or tummy!

Just follow the links or search your usual Amazon for my books. Beware, though! Make sure you get the correct Heather King!

Then sit down with a cup of your favourite brew and enjoy.

This offer is only open until Sunday, so don't delay!

Cheers,

Heather

Published on April 25, 2019 10:07

April 20, 2019

Hidden Treasures

A Day Out at Croome

With my good author friend Susana Ellis due to arrive next month for her annual sojourn in the United Kingdom, I thought it about time I shared last year’s visit to one of my favourite stately homes.

Readers of this blog will be familiar with the glories of Croome Court near Croome d’Abitot in Worcestershire. However, through reasons which will become clear in a moment, this particular visit was even more special.

Susana and I, complete with my Staffie X and newly recruited Labrador, met up with another author friend, Sue Johnson, and Croome Volunteer, Chris Wynne-Davies. Chris had promised us a guided tour of the places not usually open to the public!

Our first port of call (after a cup of tea in the picnic area near the Visitor Centre – thank you, Chris – was the Ice House. Situated in the woods near St. Mary Magdalene Church, the Ice House is an egg-shaped building with a thatched roof. As one might surmise from the name, ice was stored here for the Earl of Coventry’s household. Nearby there is a shallow pond with a brick edge. In winter, when the pond froze, the ice was cut and moved in blocks to the ice house, there to be packed in straw. Eighteen feet tall on the outside, inside the ice chamber is thirty-three feet from top to bottom. Two thirds of it is underground, the base being shaped like a keel, to help the dispersal of melt water.

Ice House Entrance

Susana, Sue, Chris and Hairy Hooligans

A stroll in the glorious sunshine took us down the hill to the Court, which sits in its’ landscaped bowl like a pearl in an oyster. The dogs being somewhat over-excited, I took a rather more circuitous route through the Evergreen Shrubbery, beautifully restored by the National Trust.

Croome Court from the Evergreen Shrubbery

The path took us by the Temple Greenhouse, the Lake and the Sabrina Grotto, as well as the imposing Worcester Gates.

The Worcester Gates

Returning via the Chinese Bridge, the dogs and I met up again with the rest of the ‘gang’. Then, not only did we authors enjoy a personalized tour of the upper floor and the ‘hidden’ treasures of Croome, Chris – the perfect guide and the epitome of gentlemanliness – also escorted us around the Red Wing. The latter is only open by arrangement and with a member of staff; it also a hard hat endeavour! Sadly, the Red Wing was allowed by a previous owner to fall into terrible disrepair – to the point where it is dangerous in places – and has only recently been acquired by the National Trust. The roof has been restored and, hopefully, in time the building will be too. Here are a few of the many pictures I took.

Rotten floorboards in the Red Wing

Artist’s impression of Red Wing during the Earl’s time.

Brick fireplace in (perhaps) the Steward’s Room.

Sue and Chris, fireplace in the kitchen

Servants’ passage

Pastry room

It was enormously exciting and a great privilege to be allowed to see the Red Wing. What it must have been like before the ravages of time, neglect and the various occupants did their worst! As you may have gathered, dear reader, it was the service wing of the Court and if you know where to look on the staircase inside the house, you can see where one of the two connecting doors has been closed off. A two-storey building, it is L-shaped and joins the house on the eastern side. Built of stone as well as the red brick which gives it its name, it has a slate roof and was constructed by Capability Brown between 1751 and 1752. A wall on the far side joins the Red Wing to the stable courtyard. Unfortunately for this horse-loving author, the stables no longer exist, having been sold long ago and converted into human accommodation. Sacrilege!

North Front, showing Red Wing and Stables beyond

Stables with carriage arch and gates leading into service wing

The Red Wing housed the servants’ quarters, kitchens and offices. It also had apartments upstairs for the 6th Earl of Coventry in his later years.

From this scene of dereliction and decay, the glories of furniture and paintings not generally seen by the public gladden the eye even more. Passing through a rope cordon, one climbs to the third floor of the house. Reduced to this ignominious (if historical) position in the stairwell, because of his size and to conserve him from damaging sunlight, hangs the enormous painting of Jack-a-Dandy (The Great Horse), circa 1680-1710 and attributed to John Wootton. Belonging to Sir Henry Coventry, a soldier, ambassador and politician, Jack-a-Dandy was pitted against Sir Henry’s brother-in-law’s horse in a race, the loser to found alms-houses in Droitwich and name them for the winner. Thus the Coventry Charity Alms-houses were founded by Sir John Packington (or Pakington) and named for Sir Henry because Jack-a-Dandy was triumphant. A wide-angled lens is needed to take a full picture, the painting is so large. This is half of it!

Jack-a-Dandy, The Great Horse, c 1680-1710, attributed to John Wootton

Here are some more of the treasures above stairs.

Elizabeth (left) and Maria Gunning, the famous Irish sisters who took London by storm

The 5th Earl and family

The Marquis of Anglesey, who lost a leg at Waterloo

The 9th Earl’s 1863 Grand National Winner, Emblem; her full sister, Emblematic, won the race the following year, the only time that particular double has been achieved.

The Earl of Coventry’s bedside table

A Georgian Commode (nothing to do with bathroom facilities!)

A semicircular table

I hope you have enjoyed this whistle-stop tour of some of Croome Court’s hidden treasures, and if it is at all possible, I encourage you to visit and view them for yourselves. The staff and volunteers at Croome are incredibly helpful and friendly and I can almost guarantee you a wonderful day out!

All photographs © Heather King and may not be reproduced without the expressed permission of the owner.

© Heather King

Published on April 20, 2019 14:47

March 25, 2019

The Earl of Coventry's Celebrated Courtesan

Kitty Fisher

Catherine Maria 'Kitty Fisher', Nathaniel Hone

Catherine Maria 'Kitty Fisher', Nathaniel HoneIn 1758, a young ‘lady’ of nineteen was fast becoming the biggest celebrity across the land. One Tom Bowlby wrote to a friend in Derbyshire, ‘You must come to town to see Kitty Fisher, the most pretty, extravagant, wicked little whore that ever flourished....’ Believed to be the daughter of a German silver-chaser, Catherine Maria Fischer, as she was born, was a renowned courtesan. She is said to have turned down Casanova, at a price of ten guineas for an hour of her company, although he would have it he declined the offer because she spoke only English and he preferred all his senses gratified, including his hearing. The procuress, Mrs. Wells, then told him that earlier in the day Kitty had ‘eaten a bank-note for 1000 guineas on a piece of bread and butter’. According to Casanova, it was a gift from Sir Richard Akins, ‘brother of the fair Mrs. Pitt’. Variously, however, this note was £20, £50 and £100 and the donor the Duke of York. There is another story of the Duke having been invited to tea at Kitty’s house, and after a convivial meeting, he left a £50 note as he departed, no doubt feeling this was largesse enough. Kitty, it seems, had expected more of the royal sibling and ordered her servants not to admit his Grace again. Much like the celebrities of today, Kitty was the subject of gossip-mongering and tittle-tattle; racehorses were named after her, Sir Joshua Reynolds painted her, and she was immortalized in the nursery rhyme ‘Lucy Lockett dropped her pocket, Kitty Fisher found it.’ You must therefore pay your penny and take your choice as to how much truth lies in any of the many tales.

‘From a physical point of view she was a beautiful girl. Though slight, her figure was moulded in graceful curves, and her limbs possessed the roundness and elasticity of perfect health. Her ripe, provoking lips and saucy tilted nose gave her face an expression of roguery, but when she chose the look would soften, and a glance of childish innocence stole into her grey-blue eyes. Dainty to the finger tips, she was always attired with consummate taste, and no woman was more clever in choosing a gown to suit her style of beauty.’

One March day in 1759, she took her morning gallop beside the Serpentine in Hyde Park, dressed in a ‘stylish black habit’ and riding a frisky piebald. Having passed through into the Green Park and enjoyed a steady canter, Kitty’s party were approaching ‘the palings of St. James’s Park’. A rank of soldiers startled the horse, which bolted down the road. Checked by the interception of some gentlemen, the piebald stopped suddenly and reared. With a cry of alarm, Kitty fell to the ground, whereupon a crowd of concerned onlookers surrounded her, helping her up and enquiring if she were injured. The sobs ceased, became merry laughter as ‘officious hands’ dusted off her habit. After a few minutes, a painted and gilded chair was brought from an appointed position nearby. Kitty, laughing a goodbye to her companions, threw herself into it and was borne away down the Mall. Whispers of “It is Kitty Fisher, the famous Kitty Fisher!” began to circulate through the gathering crowd. Then, it seems, a bluff individual declared forthrightly his indignation.

“D—my B—d," he cried, aloud, “if this is not too much. Who would be honest when they may live in this state by turning —? Why, ’tis enough to debauch half the women in London.”

The episode has all the hallmarks of a publicity stunt, does it not? Indeed, very soon the tale of the accident was being talked about, broadcast in the popular press and celebrated in song, so it achieved the desired result. The following appeared in the March issue of the Universal Magazine.

“On K—F—’s Falling from her Horse.”Dear Kitty, had thy only fallBeen that thou met’st with in the Mall,Thou had’st deserved our pity ;But long before that luckless day,With equal justice might we say,Alas! poor fallen Kitty!Then, whilst you may, dear girl, be wise,And though time now in pleasure fliesConsider of hereafter;For know, the wretch that courts thee now,When age has furrowed o’er thy brow.Shall change his sighs to laughter.Reform thy manners, change thy ways:For Virtue’s sake, to merit praiseBe all thy honest strife:So shall the world with pleasure say,“She tasted folly for a day,And then grew wise for life.”

Kitty was purportedly unamused, if not incensed, by the attention her fall had received. Mayhap her youthful beaux had pulled her leg over it; certainly, a handbook was published, entitled The Juvenile Adventures of Miss Kitty F—r, with a second volume promised. This was too much and Kitty wrote a scathing piece to the newspapers, published in the Public Advertiser’s pages two days later. Needless to say, there was a backlash (which only goes to show why one should never answer bad reviews) which served Kitty no good a turn, since the author answered in pithy terms and the second book was still published, the ‘Adventures’ being a scurrilous and rude tale containing little truth. Nevertheless, the sordid occurrence did gain Kitty the sympathy of the public.

Sadly, in the Georgian era, gentlemen were rarely faithful to their wives. Kitty Fisher counted many aristocratic gentlemen among her conquests, not least the 6th Earl of Coventry. Although he married the beautiful Maria Gunning, elder of the two Irish sisters who took London by storm despite their lowly birth, there were many misunderstandings within the marriage and the Earl made Kitty his mistress. In a letter to Andrea Memmo, Giastiniana Wynne – later the Countess of Rosenberg – who was staying in London at the time, wrote:

“The other day they ran into each other in the park and Lady Coventry asked Kitty the name of the dressmaker who had made her dress. Kitty Fisher answered she had better ask Lord Coventry as he had given her the dress as a gift.”

The rivalry was infamous and the exchange drew some notice. The Countess informed the courtesan she was an ‘impertinent woman’. To this Kitty replied – no doubt in a haughty tone – that she “would have to accept this insult because Maria was socially superior since marrying Lord Coventry, but she was going to marry a Lord herself just to be able to answer back.”

Miss Wynne also wrote of Kitty Fisher:

“She lives in the greatest possible splendour, spends twelve thousand pounds a year, and she is the first of her social class to employ liveried servants – she even has liveried chaise porters.”

Catherine ‘Kitty’ Fisher was born, then, in about the year 1738. Her working life began in a milliner’s shop, during which time she was seduced by an army ensign, Anthony George Martin, known by the sobriquet, ‘The Military Cupid’. He was the son of an English merchant by a Portuguese mistress and blessed with a fresh-faced handsomeness. Kitty moved into his lodgings and was much in love, but Martin was sent to the Continent and Kitty was left alone and bereft. Now a Fallen Woman, she was solicited by another patron and this time material gain governed her decision. Once on the path of infamy, she rose, as we have seen, to be the lover, not only of Lord Coventry, but of Admiral Augustus Keppel and General Lord Ligonier. She drove about London in a coach drawn by four of the finest grey horses money could buy, the toast of the ordinary folk and celebrated, not just for her beauty but for her wit as well.

Augustus Keppel

Augustus Keppel“Even had she been wholly plain her cavaliers would have been numerous, for her wit and high spirits made her a fascinating companion. One who should have known speaks of her as ‘…the essence of small talk and the magazine of contemporary anecdote ... it was impossible to be dull in her company.’ Since she was endowed by nature with a distinct personality, her bon mots and repartees had an uncommon zest, and were quoted in the club rooms as frequently as the sallies of Foote, the player.”

Although her origins were lowly, Kitty had “...assumed the ease and politeness of a high-bred gentlewoman and although she could be as wild a madcap as any in the company of devil-may-care admirers, her sprightliness was never tinged with vulgarity.” Despite her immoral occupation, she was clearly both clever and captivating. She had another weapon in her armoury, however, which helped to set her above others of her ilk, both before and since her tenure. Kitty was a skilful horsewoman, taught by Richard Berenger, author of A New System of Horsemanship.

It was a common event for her to be spotted ‘at high noon’, galloping along ‘the Mall’ of St. James’s on a spirited charger. She was, in effect, a woman who liked to be out of doors – no ‘stately promenade once a day’ in order ‘to take the air’ for her. She was given to frequenting the tea gardens and parks throughout the hours of daylight.

That austere publication, the Public Advertiser, was not above printing the following effusive lines from the pen of Mr. Thomas Wilkes, in the sure knowledge of garnering a slew of readers for so fashionable and attractive a subject.

Fair Venus, who oft among Mortals goes ambling,Was lost t’other day; and she somewhere went rambling;It put all the Gods to their trumps, to find out.Her Dress, her Disguise, her Engagement or Route.Apollo and Cupid, who seldom unite(Love and Reason being different as Darkness and Light);Soon jointly agreed to go search for the dame,At high Noon, to the Mall of St. James’s they came.I have found her, says Cupid, see yonder, look there;’Tis my Mother, I know her Deportment and Air;Look again, said Apollo, you blundering calf.Your Mother was never so handsome by half,Look a little more sharply, repining you’ll own.Such beauty can be Kitty Fisher’s alone.

Kitty Fisher and a Parrot, Sir Joshua Reynolds

Kitty Fisher and a Parrot, Sir Joshua ReynoldsSir Joshua Reynolds painted her twice, as Cleopatra Dissolving a Pearl and with a parrot; and Nathaniel Horne also took her portrait, picturing her with a kitten, its paw in a goldfish bowl. This portrait hangs in the National Portrait Gallery. Her name became identifiable with a particular kind of bead used in lace-making, a white bead with blue and red spots decorating it, and, of course, she is immortalized in the nursery rhyme. It is very likely she is the Kitty Fisher referred to, for she was a heroine of the ordinary folk and could well have been added to a popular rhyme – many were written about her, some extremely rude. Lucy Lockett (or Lockit) was a character in The Beggar’s Opera of 1728, by John Gay.

Lucy Locket lost her pocket,Kitty Fisher found it;Not a penny was there in it, Only ribbon round it.

Kitty led a life of fame and fortune in the public eye for ten years. Then she married John Norris Jnr., the son of a landowner in Kent. At last her infatuation for Anthony Martin died and she fell genuinely in love. At Hemsted Park, high above the village of Beneden, she rode her spirited coal-black mare (a wedding gift from her husband) with a renewed passion that stunned the villagers to awe at her grace, dash and courage as she leapt any obstacle in her path. She became beloved for her kindness, liveliness, charity and willingness to listen. For the first time, Kitty was truly happy.

She must have known it could not last, such had been the law of her life. She developed a hollow cough which became harsher, deeper and very painful. Her cheeks began to burn and her strength began to fail. Although her friends whispered she had fallen a victim of lead poisoning, as had her adversary, Lady Coventry, it has been suggested it was not so. The ‘evil-liver’ was said to be the cause and Kitty died in Bath whilst travelling with her husband to the ‘Hotwells’ at Bristol. She was the tragically young age of 29 and had been married less than five months. She was buried at Beneden, in those last months of her life a reformed character.

All pictures public domain.

© Heather King

Published on March 25, 2019 18:40

March 5, 2019

Grab a Bargain!

New Release ~ Fortunes Turn

I'm thrilled to be able to announce the release of an Omnibus of stories including my No 1 Best Seller, Carpet of Snowdrops.

All the stories have connections with horses and Christmas, so if you hanker for a blanket of snow at this time of the year rather than the wave of mild weather the UK has been enjoying recently, then this is for you. The collection also includes a hitherto unpublished magazine-length short story.

Blurb

Fortunes can turn on a person’s whim, the toss of a coin, the spin of a roulette wheel or the back of a horse through a sporting wager. In this collection, which features the Number One Best Seller, Carpet of Snowdrops, a horse is instrumental in the direction taken by the protagonists’ fortunes.

In Carpet of Snowdrops, Eloise loses her poor belongings in a river when Joscelin unknowingly charges upon her in the snow.

In Chains of Fear, Helena finds herself in danger when the horseman entering the gates of Templeton Hall is the one from whom she fled.

Following the Duchess of Richmond’s famous ball, in Copenhagen’s Last Charge, Meg joins forces with a surly lieutenant in a chase through the streets of Brussels – after the Duke of Wellington’s famous charger. Revised edition.

This collection also includes a hitherto unpublished, magazine-length short story, A Contemptible Abduction, in which Amanda becomes embroiled with smugglers.

Amazon UK Amazon US

Published on March 05, 2019 13:49

October 31, 2018

Pumpkin Pie or Apple Pie?

This Hallowe'en seemed a good time to discover which came first, pumpkin pie or apple pie, and whether the latter was really first made by the Americans...

Pumpkin pie of a sort was probably first made by early settlers of Plimoth Plantation in southern New England, the first permanent European settlement, from around 1621. The settlement continued from 1620 to 1692.

It is possible these settlers made stewed pumpkins, or mixed honey, milk and spices into a hollowed pumpkin and then baked it in the hot coals. A modern pumpkin pie consists of a sweetened and spiced pumpkin custard in a pastry case and is traditionally eaten around harvest time in the United States, since it is the symbol of the harvest. It is a staple for Thanksgiving and other special winter occasions.

In the British Isles, pumpkin was made into a pudding. This recipe comes from A New System of Domestic Cookery by A Lady (Maria Rundell), 1814.

Pumpkin Pudding

Take one quart of stewed and strained pumpkin, add

nine beaten eggs, three pints of cream, sugar, mace, nut

meg, and ginger in powder; bake in dishes three quarters

of an hour.

Later in the nineteenth century pumpkins in England were stuffed with apples, sugar and spices before being baked whole. Not a pie as we would recognize it now!

Yet what of the apple pie?

The first recipe written down for apple pie was printed by Geoffrey Chaucer, in 1381. Aside from apples, it included pears, figs and raisins and was baked in a pastry case. Sugar was expensive and rarely used at the time, so is not listed to go in the 'cofyn' of pastry. Saffron, however, was used to colour the filling. This would have been very different from the apple pie we know and love today!

Apples were used for various desserts in Regency England, including puddings, dumplings, Apple Charlotte, tarts and fritters, to name a few. They were also mixed with currants and other fruits. Here are two more recipes from Maria Rundell, for a pudding and a pie.

An Apple Pudding

Boil very tender a handful of small rice in a small

quantity of milk, with a large piece of lemon-peel. Let it

drain; then mix with it a dozen of good-sized apples, boiled

to pulp as dry as possible; add a glass of white wine,

the yolks of five eggs, two ounces of orange and citron cut

thin; make it pretty sweet. Line a mould or basin with a

very good paste; beat the five whites of the eggs to a very

strong froth, and mix with the other ingredients; fill the

mould, and bake it of a fine brown colour. Serve it with

the bottom upward with the following sauce: two glasses

of wine, a spoonful of sugar, the yolks of two eggs, and a

bit of butter as large as a walnut; simmer without boiling,

and pour to and from the saucepan, till of a proper thickness;

and put in the dish.

Apple Pie

Pare and core the fruit, having wiped the outside;

which, with the cores, boil with a little water till it tastes

Well: strain, and put a little sugar, and a bit of bruised

cinnamon, and simmer again. In the mean time place the

apples in a dish, a paste being put round the edge; when

one layer is in, sprinkle half the sugar, and shred lemon peel,

and squeeze some juice, or a glass of cider. If the

apples have lost their spirit, put in the rest of the apples,

sugar, and the liquor that you have boiled. Cover

with paste. You may add some butter when cut, if eaten

hot; or put quince-marmalade, orange-paste or cloves,

to flavour.

Hot Apple Pie—Make with the fruit, sugar, and a

clove, and put a bit of butter in when cut open.

Whatever pie is your choice, have a happy Hallowe'en and 'ware the Witching Hour... You can always stay by the fire with a spiced pumpkin latte!

Published on October 31, 2018 14:21

August 14, 2018

Creative Gold

Recently, I began a new Facebook group for Creative Writing to offer assistance to those who would like to write, for those who need encouragement and support, and for established writers who might just need feedback or brainstorming or some new exercises to stimulate the creative juices.

From an exercise I posted, Sarah Waldock came up with this beautiful poem, and has kindly given me permission to share it here. I have called it, simply:

White Horses

White horses crashing and rolling, white horses that rise on the sea

A single black horse gallops onwards, it carries my sweetheart to me

Galloping on through the shallows, galloping over the sand

White horses fret at the edge of the shore where the water is met by the land

The waves shatter hard on the shoreline, the waves being horses no more

But my lover will ride on regardless, riding onwards across the dark shore

He will gallop across the dark causeway, racing the tide as it floods

And when he has reached my lone island his kisses will sing in my blood.

He will gallop across the dark causeway, revealed by the ebb of the tide

And will gather me into his arms once again, and will ne’er more be reft from my side

Together upon my lone island we will hear all the sounds of the sea

And the white horses race o’er the causeway which carries my lover to me

Oh my lover! Please hurry, please hurry, the waves are encroaching too fast

And the white horses play on the causeway, and the safe time for riding is past

I look out from my lonely island, and in the dark waves I can see

Amidst the white horses one black horse’s head, swept away by the herd from the sea.

In the morning the shoreline is quiet, an exhausted black horse on the sand,

And the white horses born of the ocean just shake soft manes at the land

But the man who was recklessly riding is gone now forever below

For defying the horses of Neptune far under the waters that flow

© Sarah Waldock

Published on August 14, 2018 09:04