Max Haiven's Blog, page 5

May 7, 2022

Is Amazon the Borg? We Asked Their Workers (LA Review of Books)

This essay was published in the Los Angeles Review of Books on May 7, 2022.

Is Amazon the Borg? We Asked Their WorkersBy Max Haiven, Graeme Webb and Xenia Benivolski

Enter, futurekillerIn Everything and Less: The Novel in the Age of Amazon, literary critic Mark McGurl notes that the corporation, which in 25 short years has become the world’s largest retailer and one of its largest private employers, has been guided by a self-aggrandizing science fiction narrative. The firm has in numerous ways been inspired and shaped by the favorite genre of its founder, Jeff Bezos, who has famously used his massive share of its profits to finance his own private space program. Amazon flatters itself as an angel of capitalism’s creative destruction, wielding the flaming sword of digital technology to liberate humanity from the clutches of the past.

The company has transformed how we buy books but also how and what we read. Today it is one of the world’s largest publishers, with a jealous hold over tens of millions of Kindle readers as well as over writers who pen novels (typically genre fiction) on its exclusive platform. Via its subsidiary Audible, Amazon is unrivaled in the realm of audiobooks. Beyond the written and spoken word, Amazon’s digital streaming services are among the most popular, and it has ambitiously sought to finance award-winning films and TV serials to announce itself as a leading studio and media producer. Once a platform to merely buy books, the company has become a content creator across multiple media. It shapes the stories we tell ourselves about our world. It is also quickly becoming the United States’s leading retailer, gobbling up market share in the sale of everything from garments to video games, from household staples to office supplies. Tens of thousands of smaller businesses now compete with one another to use Amazon’s order and fulfillment platforms to sell their goods and services to the giant’s dedicated customers — a kind of walled garden version of the free market.

But the firm has not been content to stop there. It has also leveraged its early success to become the world’s largest provider of web services and data management. Amazon servers are the back-end of a huge proportion of the internet, and they manage the data of many of the world’s top companies, public institutions, governments, and even military and security forces. It has also transformed the logistics industry through its advanced employment of machine learning and revolutionized how warehouses work through its extensive use of robotics. The company has sought to become a ubiquitous presence in our lives: in 2017 it acquired the American grocery giant Whole Foods, and in 2019 it introduced Amazon Care, a digital health-care service aiming to disrupt that industry in the United States as well.

While capitalist firms by their nature compete by predicting the future to capitalize on new markets and manage risk, Amazon is actively seeking to leverage its massive wealth and power to create a future in which it is dominant. Their corporate slogan “work hard, have fun, make history” indicates the kind of relentless, progressivist jouissance that animates the company’s strategy. Communication scholar Alessandro Delfanti and Bronwyn Frey’s recent study of Amazon and its subsidiaries reveals the wide array of patent applications held by the firm and indicates the type of mind-bending future they envision for us all.

Who makes the future?And yet who is building that future? Recent years have seen numerous stories about the horrors endured by workers throughout Amazon’s operations. Workers in the firm’s corporate offices report a culture of overwork, stress, and verbal abuse. But these white-collar workers have it relatively easy. Delivery drivers work punishing schedules, often forced to compete with one another to quicken their pace, at the expense of their own health, safety, and well-being. Even the independent packages endure punishing forms of self-exploitation in the name of the massive corporation’s profits. In what could have been taken directly from Orwell’s cautionary tale of the future in Nineteen Eighty-Four, warehouse workers toil under conditions of staggering surveillance and micromanagement, often at a pace set by robots, and are forced to wear sensors that track their every gesture and vital sign to maximize efficiency. Then there are the gig workers on the firm’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) platform, who compete from home against one another for digital micro-contracts often denominated at cents-per-second ratios and usually taking the form of medial data entry or simple coding tasks. Often this work trains the very algorithms that will eventually replace them or other workers. If Amazon is building the future, it is building it on the backs of its workers. And, indeed, many of its techniques seem the stuff of dystopian fantasy.

Around the world, workers are rebelling, forming trade unions and workers’ organizations. However, the infamous union-busting techniques of the firm in Bessemer, Alabama, indicate its violent and ruthless allergy to this kind of worker activism. To push back against these Pinkerton-esque strategies, efforts are afoot, under the banner of the global Make Amazon Pay coalition and the American Athena coalition, to coordinate efforts of unions, workers’ centers, civil society organizations, and other progressive forces to challenge Amazon’s power — and some of these efforts have recently achieved success.

Even with such preliminary victories, however, these struggles are so deeply in the trenches they have a hard time making space and time to see the horizon. Beyond defending workers’ rights and seeking to halt the relentless advance of Amazon, it is imperative to envision alternate futures. The technology and wealth that, today, Amazon and other “technofeudalist” firms monopolize can and should be used to liberate humanity from toil, not institute an even more punishing and exploitative regime of exploitation.

How might such a future be envisioned, let alone instituted? What role will workers themselves have to play in imagining and stewarding its birth? What do workers themselves have to say? Strangely, few people seem to ask. But we did.

Studying science fiction with Amazon workersIn November and December 2021, we recruited around 24 rank-and-file Amazon workers to watch science fiction shows with us and talk about the future. We met on Zoom once a week and workers were remunerated for their time. Together, we watched films including Snowpiercer, TV shows like Squid Game, Black Mirror, and Star Trek, and played games from radical gamemaker Molleindustria that reflect on the conditions of digital workers. We asked the workers if and how this media content helped them reflect on their work at the corporation. The purpose wasn’t so much to gather data for academic research but to create a space where workers could theorize their experiences for themselves. It was open to both current workers and those who had recently left the company’s workforce, but not to managers. Participants were invited to use false names or no name to protect their identities.

The first thing we learned is that there are a lot of different kinds of workers at Amazon. In our group, we had warehouse workers, delivery drivers, content writers, MTurk workers, and data analysts from all across the United States, and some from Canada. They had vastly different cultural, linguistic, educational, and economic backgrounds, which sometimes made dialogue challenging. Some were huge science fiction fans with encyclopedic knowledge of the genre. Others were casual consumers. While some had clear political views on capitalism, in general they seemed happy to lead respectfully non-partisan discussions framed by the collective desire for a better future. Most were forthcoming about how difficult it was to work at Amazon and how demanding they found the company’s management tactics and relentless surveillance. But many were also happy to have the work, either because it provided a stable income or, in other cases, because it provided flexibility.

Most of the participants tended to identify strongly with the dystopian themes in the films and TV series we watched and the games we played. They almost universally felt that the future looked pretty bleak for workers (not only Amazon workers) and that it was likely that technological changes would serve the interests of the rich. Revealingly, many questioned the relevance of wealth in a crumbling world: would class make much of a difference in the dismal, ecologically ravaged, war-torn future? But others were exasperated this pessimism and encouraged us to think about what could be done today to prevent both a terrible future and continued hyperexploitation.

One contradiction that came up again and again was that, while many workers spoke to the dystopian present and future, they also expressed an abstract optimism about their own personal circumstances. Several participants expressed the sentiment that we should stick together and help each other in facing the oppressor — which was not necessarily Amazon, but systems of inequality at large. Teamwork and working together to overcome challenges were big themes in our conversations, and often reflected in the media we watched together. Most workers also told us that feeling part of a team was the best thing about their job. They were almost all skeptical that Amazon management would ever recognize or appreciate their hard work. They talked a lot about how unfair they found the system of rewards and punishments on the job. In its factories, Amazon brought back the ’80s bastion “employee of the month” to encourage hard work, but the workers we talked with felt this was a largely dystopian gimmick. They also resented the constant technological “nudging” toward reward-seeking behavior. For example, employees with repetitive positions are encouraged to fill out surveys while they work to earn minutes of vacation time.

Many watched or read science fiction, or they played sci-fi-themed games as a way to escape from the demanding world of work itself, and so they were less enthusiastic about taking critical positions on the content we watched together. Compounding this, some reacted so strongly to the dystopian themes (a few even calling it “triggering”) that they admitted to having difficulty watching or playing the games we had selected. And yet, there was a clear sense that sci-fi, especially dark and dystopian science fiction, was appealing to the group. Why would people who already lived and worked in what would probably appear to a time traveler from the past as a dystopian sci-fi scenario enjoy the genres? What interest did these texts offer to workers who are relentlessly surveilled, measured, controlled, and pitted against one another by a huge corporation that literally uses their exploited energies to realize the megalomaniacal fantasies of their CEO to go to space?

In our discussion, it became clear that watching SF film and TV was a form of escapist entertainment, a way of winding down after a hard day (or night, or week) of work. But why not romcoms, or period drama, or soap operas? Or why not more optimistic SF, like Star Trek? Certainly the answer was different for all of the workers we spoke to, but we wonder if, on some level, the dystopian SF was somehow validating.

Toward a futurist workers’ inquiryOur approach was deeply influenced by a new wave of an old method that intellectuals have used to collaborate with working people. What came to be known as Workers’ Inquiry emerged in Northern Italy in the 1960s as the country underwent a rapid postwar industrialization and migrants flooded from the poor agrarian South to cities like Turin and Milan. For radical intellectuals, who were increasingly disappointed with the Italian Communist Party’s slide into compromise and complacency, these new workers represented a revolutionary constituency, but one that was very different from the proletariat of Marx, Lenin, or Antonio Gramsci’s day.

These thinkers, many of whom were renegades from Italy’s highly conservative academic system, set out to study how capitalism was transforming workers and how workers, through their struggles, were forcing capitalism to transform. They did so in part by setting up study groups with workers that placed in their hands the tools for understanding their own conditions as in some sense emblematic of the capitalism of which they were part. Theorizing from the proverbial “shop floor” offered both workers and intellectuals not only an ant’s-eye view of capitalism, it also revealed workers’ power. The goal of this action research was to see how the exploitative machinations of capitalism were not the ingenious orchestrations of the powerful but, in fact, the desperate, rear-guard attempt by capital writ large to contain and combat new forms of worker militancy.

A later generation of radicals who carried forward the spirit and practices of Workers’ Inquiry combined it with a theoretical orientation that built on the “fragment on machines” found in Karl Marx’s Grundrisse, the notebooks the radical philosopher made as he prepared to write his massively influential Kapital. For Marx scholars, the Grundrisse, which was not published until well after his death and decades after the formation of the Soviet Union (and was not even translated into Italian until the 1970s), maintained a more youthful, humanitarian dimension. The text was concerned not only with the way capitalism thrives on the exploitation of workers but also how it foments and depends on their alienation. Alienation from the things they create, from one another, but also from their “species being” (their human capacity to transform the world). Also, importantly, alienation from their capacity to co-create their future. Within those notebooks, the “fragment on machines” offered radical Italian theorists a language to speak of the way that workers under capitalism were part of and also shaped the “general intellect.” Typically understood to be shaped and monopolized by capitalist institutions, this aggregate sum of knowledge, science, technology, and art was also seen to be a product that workers helped to create. The fruits of modernity were the product of the labor of a whole society and shaped that society. But under capitalism, only a handful of individuals, usually of the ruling or middle class, ever have the opportunity to become intellectuals, technologists, and scientists. As such, the ideas and technologies they develop are hoarded by capitalist enterprises where the labor of the masses is used to transform ideas into commodities. Italian Marxist activists and theorists envisioned, by contrast, a form of socialism that included a “mass intellectuality” where the power to imagine and create was democratized.

More recently, scholars, activists, and labor organizers around the world have rekindled the Workers’ Inquiry method. This resurgence stems from a recognition of the necessity to trust and empower workers to become researchers and the way it centers workers as the driving force. Academic work must be done differently and democratized if there is a chance to challenge existing structures of power. But while the original Workers’ Inquiry in Italy focused almost exclusively on male industrial workers and the conditions of exploitation in the factory, we draw from more subsequent updates to this approach that see workers’ relationship to capitalism as occurring in many places and in many ways: the extraction of value through rent, for instance, or the unpaid reproductive labor workers’ must perform in the home (cooking, shopping, cleaning, caring for children and loved ones), work still disproportionately expected of women and, today, often commodified as discounted “services” on transnationalizing markets.

As the investigation of Amazon has become the forefront of research on the intersection of labor and capitalism, there have even been several recent approaches in using workers’ inquiry to understand the changing nature of capitalism through an investigation of Amazon warehouses and work on the Mechanical Turk microtask platform. Our project takes inspiration from these projects and seeks to extend this research. It departs from conventional Workers’ Inquiry in that our project isn’t exactly worker-led and, at this point, it’s more about discovering if it’s possible to think with science fiction about the challenges workers face today, rather than about shop-floor resistance. But our hope is that this research might inspire rank-and-file Amazon and other “platform capitalism” workers to undertake similar initiatives, or that labor organizers might also see some value in using the genre to explore the new dimensions of work and resistance.

Is resistance futile?The career of Amazon and its founder and former CEO, Jeff Bezos, is intimately connected to the science fiction genre. Bezos has at many points identified Star Trek as his single most important inspiration. So much so that he considered naming Amazon makeitso.com after the catch phrase of his hero, Captain Jean-Luc Picard of Star Trek: The Next Generation, which aired new episodes from 1987 until 1994, the year Amazon’s predecessor company was founded. Bezos even styles his appearance on that of Patrick Stewart and is unabashed in his embrace of the thriving and obsessive nerd culture around the franchise. According to his own testimony, and those of other founders and executives, Bezos would regularly make reference to Star Trek episodes in corporate strategy meetings and the series was in some senses pivotal to the internal culture of the company.

In fact, it is strongly suspected that Amazon was really an effort by the former financier to generate the wealth to launch his own private space program. In 2000, these efforts became reality with the creation of Blue Origin, whose mantra is “Earth, in all its beauty, is just our starting place.” When the company was finally successful at launching manned rockets in 2021, one of the first “guests” was the actor William Shatner, famous for playing the maverick Captain Kirk on the original Star Trek series, which a young Bezos watched with an almost religious fervor.

It is, then, both ironic and telling that the empire Bezos created in some ways resembles a kind of dystopian world that his idolized intergalactic explorers might encounter and seek to liberate. In each incarnation of the franchise, Star Trek has dwelled on the social and philosophical issues related to the prospects of freedom, the nature of exploitation, and the possibilities of peace and cooperation across cultures. The noble United Federation of Planets was dreamed up by the series’s founder, Gene Roddenberry, as an antidote to the culture of fear and xenophobia fostered by the Cold War. He envisioned an interstellar alliance of species, including a multiethnic mix of humans, that, together, dedicated themselves to peace and exploration. In the journeys of their flagship Enterprise across multiple different series, the Federation encounters numerous planets and societies that act as allegories for our present-day earthly concerns. Critics have noted that, in the Cold War, Star Trek often appeared as a benevolent fantasy of the American Empire, championing notions of individualist “freedom” in contrast to the collectivist pathologies of alien species. But as the series developed, it would also, at times, come to critique the kind of ruthless and reckless profiteering associated with capitalism. However, the Federation is, ultimately, a postcapitalist fantasy based on the presumption that the development of technology will, by the 24th century, have largely eliminated the need for human toil and create a world of abundance and peace.

If it is Bezos’s dream to create such a world, he seems to be more than willing to sacrifice the lives, health, and well-being of millions of workers to achieve it. A recent leaked memo reveals that Amazon executives worry that, in many of the locales where there warehouses are located, they fear that the grueling pace of work and high rates of workers’ physical and emotional burnout will mean that the company will soon experience profound workers shortages as there are not enough new (and desperate) would-be workers to exploit. The exploitative and abusive practices of the company, combined with the larger-than-life corporate culture and megalomaniacal (former) CEO all feel like they were scripted with a heavy hand in the Star Trek writing room: some producer evidently let the concept slide by, without sending it back with a note saying, “Too on the nose: make the allegory for the evils of capitalism more subtle or we’ll lose the audience.”

If Star Trek has been such a large influence on Amazon’s development, perhaps there are clues within its plot lines and tropes that might help us unpack the firm’s deeper dimensions. In 1997, two years after it started selling books online, Amazon was publicly listed on the New York Stock Exchange. In that same year, Star Trek: Voyager, then in its fourth season of network syndication, introduced the character Seven of Nine. Seven was a cyborg that the ship’s crew rescued from the Borg, a hive-minded alien species that, since their first appearance in the series in 1989, have terrorized the Federation and its heroes. Like her counterparts in The Collective, before being “assimilated” Seven was once an intelligent, independent human. However, upon being abducted as a child by the virus-like horde they were transformed into a powerful robotic drone dedicated to their collective mission of doing the same to all intelligent, independent lifeforms in the universe. Their monotone mantra, “resistance is futile,” has become so stitched into popular culture its origins have been largely forgotten.

Separated from her fellow drones, Seven eventually reclaims some sense of her individuality and morality and joins Voyager as part of its diverse crew. Her humanity recaptured, she becomes an invaluable strategic asset, not only for her superior strength, endurance, and intellectual capacities, but also because, having once been part of the hive mind, she has special insight into and even contact with it. Now part of the resistance to the Borg’s endless, viral growth, her intimate, embodied knowledge becomes a source of hope.

Is Amazon the Borg? In another chilling mantra of this intergalactic horde, will they continue their parasitic advance, seeking to: “Add your biological and technological distinctiveness to our own”? Will our culture be made to “adapt to service us”? As more and more industries fall to its relentless, digitally augmented expansion or recast themselves around its model, the metaphor is tempting. Certainly it resonates with scenes of warehouses where workers wear sensors linked to Amazon servers, measuring and subtly “correcting” their movements to ensure efficiency in the service of profit. Though they retain their individuality and are framed by the company as “entrepreneurs,” the image of thousands of MTurk workers at computer terminals around the world racing to fulfill endless, mundane digital microtasks fed to them by an Amazon proprietary system transforms these workers into something not unlike drones. Amazon’s fleet of delivery drivers, who are constantly being nudged to do their work faster through arcane digital systems, is not altogether foreign. Sure, all these workers are allowed to retain their sense of individual selfhood. Unlike the Borg, they are technically free to quit at any time. But how much does that matter in an economy where increasingly every firm is learning from or being “disrupted” by Amazon’s model?

Worker as futuristWe speculate that, like Seven of Nine, Amazon workers may have some special insight and intuition of how to resist and rebel not only at the level of their conscious intellectual reflections, but also encoded in their very bodies. Workers are, of course, categorically excluded from management decision-making and strategy. The algorithms that govern their bodies and time are opaque. And yet our sci-fi-inspired conjecture is that workers intuit something about the firm and the future it is building by virtue of having been bodily assimilated into spaces and mindsets prescribed by Amazon’s corporate demands. Though their access to and power over Amazon’s “collective intelligence” is limited, they are still in some sense possessed by it and so have some preternatural awareness of it.

If that’s the case, then rank-and-file Amazon workers themselves may have the most important insights about how to challenge the company’s future-making machine. The wager of our project is that, by creating welcoming, convivial, and creative spaces we can work with Amazon workers to awaken their secret insight into the future-making (or future-killing) power of their exploiter. By using the genre of science fiction, so pivotal to Amazon’s foundation and operations, we might be able to labor together to envision a near-future world beyond Amazon’s grasp, where the potential to co-create a future is shared democratically, rather than hoarded by a corporate oligarchy.

In the next phase of our project, we will invite (and pay) 12 rank-and-file Amazon workers to become or hone their skills as writers of science fiction. We will offer a series of writers’ workshops and collaborative study sessions where, together, we can come to understand Amazon and the future it is creating. And beyond this, to develop our own powers to imaginatively seek out and share strange alternate visions of our new world. We will challenge our guests to develop short stories about a world beyond Amazon: utopian, dystopian, optimistic, or pessimistic. Amazon workers will workshop the stories together and we will work with publishing partners, including LARB, to bring them to the public.

We should, of course, not expect that the science fiction texts Amazon workers write will give us a blueprint for a universal future. Rather, their writing might invite generative public conversations and awaken the radical imagination in new ways. Another collective intelligence is possible. Resistance is far from futile.

¤

A version of this essay is forthcoming in Routledge International Handbook for Creative Futures, edited by Alfonso Montuori and Gabrielle Donnelly and due out in late 2022.

¤

¤

Featured image: “Amazon España por dentro (San Fernando de Henares)” by Álvaro Ibáñez is licensed under CC BY 2.0. Image has been cropped.

The post Is Amazon the Borg? We Asked Their Workers (LA Review of Books) appeared first on Max Haiven.

May 2, 2022

The Sacrificial Altar of Extractive Capitalism: Notes on Abolition and Transition (Mediapart/Berliner Gazette)

This text, published in English on Mediapart, is a contribution to the Berliner Gazette’s “After Extractivism” text series; its German version is available on Berliner Gazette. You can find more contents on the English-language “After Extractivism” website.

It is difficult to find a more fitting and terrifying insignia than palm oil of the intersection of capitalism’s economy of exploitation and ecological destruction. For nearly 200 years, this plantation commodity’s development has been marked by sacrificial violence where, in the name of profits and cheap prices, human and non-human beings have been placed on the altar of the market.

Today, palm oil is estimated to be present in some form in at least 50% of supermarket products. It is a cheap oil for the frying and fattening of processed baked goods, a base for soaps, detergents, and cosmetics, and a trace ingredient in the surfactants, preservatives, and stabilizing agents that are increasingly part of our diets. It’s also an important source of biofuels, touted as the key to a “green” transition within capitalism.

But over the past two decades, environmental and human rights groups have sounded the alarm.

Growing markets for palm oil have led to catastrophic tropical deforestation as biodiverse ecosystems are razed to make way for lucrative monoculture plantations, releasing massive quantities of sequestered carbon. On the ever-expanding palm oil frontier, land-grabbing is rampant. In Indonesia and Malaysia, from whom some 70% of the global palm oil demand is exported, as well as, increasingly, Brazil, Columbia, and Honduras, a handful of extremely powerful companies control the market. In spite of two decades of efforts by a roundtable of these corporations, alongside sympathetic governments and wary non-governmental organizations, towards voluntary regulation and auditing schemes, human rights abuses are rampant, including the intimidation and assassination of union organizers, Indigenous activists, and environmental journalists.

The colonial h orror of palm oil

The horrors of the palm oil industry are exhaustively documented and the subject of major campaigns by human rights and environmental groups and many government task forces. But what few of these attend to, and what I want to highlight, is the deeper entanglement of palm oil and extractive capitalism.

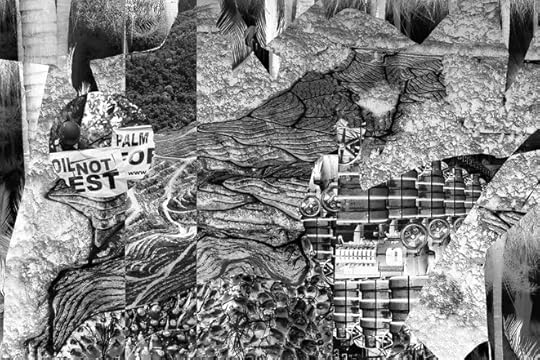

Artwork: Colnate Group (2022) cc by nc

Artwork: Colnate Group (2022) cc by ncThe story of palm oil’s emergence as a global commodity has plenty to teach us. The oil palm has been cultivated and harvested for millennia in it’s native West Africa, where its products played a foundational culinary, spiritual, cultural, political, and economic role. When enslaved people and their allies around the world rose up and forced the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade in the preeminent British Empire in 1807, Liverpool merchants who had made their fortunes in that horrific economy-defining business searched for new, non-human cargo for their ships. They found in palm oil an abundant commodity to extract from Africa that could, in Europe, be transformed into a cheap grease to lubricate the locomotives and steam engines of the dawning industrial revolution.

The same networks of ecological and economic violence that were used to extract and commodify African people were turned towards exploitation and enslavement within Africa itself to secure artificially cheapened palm oil. Industrial chemists in Europe soon found ways to refine the stuff into candles and soap, two of the first mass commodities, which, ironically, were both sold to European publics using racist imagery that encouraged consumers to identify with the allegedly noble ambitions of empire: to bring commerce, Christianity, and civilization to African people painted as barbaric savages.

To this day, the trope persists.

A history of violence hidden in plain sight

The consumer is led to believe that, in partnership with benevolent “green” corporations, they can do their part for the world simply by buying “sustainable” products. Beyond the falsity of claims to “sustainability,” such discourses reiterate a colonial and white supremacist worldview in which the citizen-consumer in the Global North expresses a self-satisfied benevolence through their capitalist transactions. Both in the 19th century and today, this approach abandons any struggle for global solidarity – which we desperately need – for a kind of consumer narcissism.

It also hides something deeper and more perverse. In the 19th century, as Europe’s predatory states expanded ever-deeper into West Africa and aimed at securing more and more palm oil exports, these incursions were often justified in the name of a humanitarian intervention to “liberate Africans from local kings” whose practices included human sacrifice. Gory details of these practices were salaciously depicted in the British press to build support for imperial invasion. But this was a form of misdirection: the goal was always to build an economy of extractivism.

Further, rendered invisible was the fact that the British Empire itself was a society of human sacrifice: whole civilizations were wiped off the face of the earth in the name of its capitalists’ need for palm oil and other basic materials; even in the British factories where those materials were transformed into commodities, workers, many of them children, were sacrificed to the machines as industrial accidents, overwork or chronic poverty took their toll.

The alleged human-sacrificial customs of the non-white, colonized “other” helped distract and deflect attention from the monstrous sacrificial system of capitalism, hidden in plain sight.

Workers, forests, and the world’s poor

Today, such conditions of extractive capitalist human sacrifice persist in new forms. Of course, we can point to the atrocious working conditions on and around oil palm plantations. From Southeast Asian to West African to Latin America, the abuse and exploitation of migrant workers has been a mainstay of the industry, workers often displaced by previous rounds of extractivism that have forced them or their ancestors from traditional land bases and sustainable economies. In the palm oil fields, migrant workers who are often denied protections are exposed to toxic chemicals, dangerous working conditions, conditions of debt-bondage, and sexual exploitation.

Often, these horrific conditions and the burning of forests are perpetrated not by brand-name consumer products companies or even the corporations that supply them with palm oil but sub-contractors and sub-sub-contractors operating at the frontier where auditors and journalists don’t travel and where government officials can be intimidated and bribed, conveniently allowing those capitalists higher up the supply chain to claim ignorance or helplessness.

But palm oil’s economy of sacrifice is not only one that places workers and the forest on the sacrificial altar. While the industry’s defenders brag that they are reforesting the world with fast-growing plantation plants, the net carbon emissions represent a significant contribution to anthropogenic climate change and the destruction of biodiversity, both of which have profound human impacts especially on the world’s poorest people. Ironically, it is precisely the world’s poorest people who have been transformed by sacrificial extractive capitalism into the main consumers of palm oil: it is, today, the fat of the world’s poor.

Middle-class consumers in the Global North may pride themselves on helping save orangutan habitat by forgoing Nutella or other palm oil-laden foods. But for hundreds of millions of people around the world, imported, refined palm oil is a basic foodstuff, having replaced locally-produced plant and animal fats in their diets thanks to its incredible artificial cheapness. The health impacts are significant, not only because palm oil is high in saturated fats which jeopardize heart health, but because it is found in so many cheap, processed and prepackaged foods that have become the staple or poor people’s diets, especially of those poor people who have been displaced from land bases where they can produce their own food.

Feeding surplus populations with palm oil

One demonstrative example is the diet fed to prisoners in the American system of mass incarceration, which disproportionately imprisons working class Black and racialized people. Here, almost every item of a standard prepackaged meal (bread, processed cheese, processed meat, packaged cookie, sugary drink-mix) is heavy in cheap palm oil. Indeed, in the US prison system the prepackaged ramen instant noodle (basically: wheat flour, palm oil, and sodium) has become a significant alternative currency among imprisoned people who, without it, are often denied enough calories to survive.

In her landmark 2007 book “Golden Gulag” geographer and prison abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore takes such prison environments as indicative of a broader shift within capitalism towards what she, instructively, calls an “era of human sacrifice.” Her book focuses on the prison as a capitalist technology for the management of “surplus populations,” people who have been made dependent on wages within a capitalist economy to purchase the necessities of life, but for whom capitalism increasingly has no waged work, forcing them to accept extractive forms of exploitation or survive in the “informal economy.”

Claims that this “surplus population” is due simply to automation – suggesting that capitalist industries require fewer workers – are largely bogus and ahistorical: the reality is that capitalism has always generated large populations of would-be workers that represent two things: a “reserve army” of unemployed people to help depress wages in the broader economy and a hyper-exploitable population on whose backs the broader economy is built. Today, palm oil is chief among the “cheapened” foods that sustains the life of these and other sacrificial victims of the extractive capitalist economy.

Against and beyond the system of human sacrifice

As was the case with the British Empire, today’s global form of extractive capitalism is a system of human sacrifice hidden in plain sight. I am attracted to this term not simply for dramatic effect. Surely, the horrors of the global economy don’t need to be the subject of hyperbole: they’re bad enough on their own. Rather, thinking about human sacrifice invites us to consider the cosmological dimensions of this economic violence. In the name of a god-like “market” we, today, legitimate extreme forms of human and non-human sacrifice and suffering. The high priests of this god insist that, to question or interfere in the will of the market will bring chaos and calamity. But do not the high priests and beneficiaries of all sacrificial societies claim something similar? Were they not to place the victim on the altar and cut out their heart, the gods would starve or be angered and unleash terrible violence on everyone.

Deeper still, framing extractive capitalism as a system of human sacrifice helps us understand the magnitude of the task before us to achieve some horizon after extractivism. Our task will not simply be to abolish the old economy and install a new one. It must necessarily include a radical transformation of belief, of value, and of meaning-making. At stake is the creation or rekindling of other modes of post-capitalist interdependence.

We are already in an interdependent world, but that interdependence is encrypted and managed by capital, a force that is driven by competition and profit compulsion, and that has been exhausting people and the planet in the name of its own reproduction. The past two centuries of palm oil’s history show us how deeply enmeshed we all our, materially and culturally, with an order of capitalism that, today for example, manages to sustain itself by promoting ever more “green consumerism.” Here, the subjecthood of the capitalist consumer is revamped as a solution, even though it is a leading contributor to the problem.

To overcome this system and to pave the way for a transition into a just world, then, requires we not only transform the palm oil industry, not only transform the global food system, but transform ourselves and our communities on a fundamental level. Here, we must dare to dream dangerously of global commoning and global forms of socialism, and new ways of configuring the dynamic triangle between the individual, the collective, and the public.

The post The Sacrificial Altar of Extractive Capitalism: Notes on Abolition and Transition (Mediapart/Berliner Gazette) appeared first on Max Haiven.

April 27, 2022

A reflection on the radical imagination: From finance to social movements to games (Junkyard)

This piece was first published on April 27, 2022 by The Junkyard: A scholarly blog devoted to the study of imagination.

As a child, I was slow to learn, not because of any specific diagnosable developmental delay but because of some deep, abiding and often angry skepticism towards anything that seems to me to be an arbitrary social convention that was presented as an unquestionable truth. For example, I remember being called before the class for some task in school at the age of 7 or 8, only to inadvertently reveal I could not tell my right from my left. Red-faced, I threw a tantrum before my shocked and bemused classmates, explaining that the distinction was purely conventional, calibrated solely by, so far as I could tell, the doctrines of our forebears. Such orientation was a form of guided narcissism, rather than a material point of reference: My left, I ranted from in front of the room, was my classmates’ right, after all. Why do we even use these words? Wasn’t it a matter of arbitrary perception being passed off as an iron law of nature. How many other things had we been taught as truth that were, in fact, habits of collective thought? What made North up and South down? Why did certain letters have to make the sounds we associated with them when they were all funny symbols that exist nowhere in nature?

I relate this anecdote not to impress or terrify the reader with my childish precociousness: credit here really ought to go to my parents and teachers who humored and tolerated this stormy little self-styled philosopher; it can’t have been easy. Rather, I think it’s a revealing place to start an account of what has been a life-long interest–perhaps an obsession–with the power of the imagination to shape our collective life. Just because the distinction between right and left is, ultimately, a figment of the collective imagination, that doesn’t make it any less real. Money is equally an invention of the imagination, but try to survive in a capitalist society without it and you run into very real difficulties. The way the imaginary becomes real, and the way reality shapes the imagination, is a riddle that has sustained my curiosity.

Growing up in a household of activists must have made its contribution to my skpeticial disposition, and it would later lead me, as a young adult around the turn of the millennia, to become an organizer in Canada in what was then called the alter-globalization movement, then, quickly following that, the anti-war and anti-racism struggles surrounding the advent of the War on Terror. I witnessed the power over the imagination of the neoliberal discourse of the End of History, what Mark Fisher would later call “capitalist realism.” In spite of the manifold injustices in the global capitalist order, the abiding belief that this was the best of all possible systems, or that in any case it was impossible to change matters, was profoundly demobilizing. I sensed, in the course of my activism, that, while not without some success, my comrades and I were only ever reaching about 5% of the population with our impassioned calls for global solidarity. Part of the problem, I realized at the time, is that most people had convinced themselves that the reigning order was natural, normal or inevitable. But many more simply had no time, or were denied the opportunity, to imagine the world broadly, and to recognize that much of how the world works is an arbitrary human construction, held in place by convention and unquestioned belief in the status quo. Worse still, capitalism increasingly seemed to find ways to seduce and co-opt the imagination, a trend that has reached a fevered pitch in the gig economy and in influencer culture, where we are told that expressions of our creative imagination can be our ticket to fame, riches or even simply a modicum of material stability in an otherwise unstable world.

This led me to enroll in graduate school, in a then-new program in the then-topical Globalization Studies. It was here that I came first into contact with the theories of Cornelius Castoriadis, the Greek-French philosopher of the radical imagination. Castoriadis, who was a core protagonist in the influential French journal Socialisme ou Barbarie in the late 1950s and early 1960s, sought to merge the insights of Marxism and psychoanalysis while, at the same time, discarding the more conservative dimensions of both traditions. His work would become highly influential on a generation of students and workers who, in 1968, almost brought down the French government through militant protests and strikes. For Castoriadis, the radical imagination was not the property of this or that ideological position but a fundamental force in all human affairs, active underneath society and within each and every social subject. Castoriadis’s ontological claim was that the imagination is the protean stuff out of which both subjects and institutions are made, a magma-like, flowing substance, between liquid and solid, that flows beneath the surface. Like magma, when it erupts it soon solidifies, and we take these solidifications as hard, fast and eternal, forgetting their tectonic origins. But both on the level of the subject and society at large, another eruption awaits, which will either be channeled by the existing crystallizations to reproduce their order or sweep them away to make room for new institutions.

Like Castoriadis, I became fascinated by the way the unique socioeconomic system of capitalism both relied on and shaped the imagination. The highly mediated capitalism of early 21st century Canada was, of course, quite different than 1950s France, and my interest increasingly gravitated towards the way the imagined systems of human categorization organized around the idea of “race” (a pure fiction invented to justify imperialism, but which became and remains deadly real) continued to have such sway and to be one of the key ways that exploitation and inequality was reproduced in the interests of corporations and the extremely wealthy. But I also, starting in 2005, became fixated on another intersection of capitalism and the imagination that was to captivate everyone’s attention a few years later: the financial sector.

In the wake of the 2008 global financial meltdown many commentators and theorists sought to understand how the arcana of finance caused such chaos: credit default swaps, collateralized debt obligations, structured investment vehicles and other derivatives seemed to be figments of the contorted imagination of Wall Street bankers calculated to clothe naked exploitation in the garb of scientific calculation. But I argued that is only part of the story, and the least interesting part at that. More broadly, a process that critics have called “financialization” has not only seen the growing wealth and power of the financial sector around the world, it was leading to profound social and cultural transformations. Here, I drew deeply on the work of New York University’s Randy Martin, who would later host me as a postdoctoral fellow in 2011, shortly before his tragic premature death four years later. For Martin, financialization also meant the way each and every social subject is encouraged to embrace and adopt the dispositions, ideas and value system of finance, even if they have nothing to do with the movement of stocks or bonds. In a neoiliberal age, where forms of public social security have been cut or privatized, we are all instructed, sometimes explicitly, more often implicitly from a million cultural points, to see ourselves as savvy risk-managers, navigating a world of opportunities for personal enrichment and betterment. Education is recast as an investment in one’s human capital; housing is recast as a financial opportunity or liability; in an age of the gig-worker, one’s passions, hobbies, personal networks, friendships and dispositions all become assets to be put in play. The entrepreneurial self theorized by Michel Foucault and Nicholas Rose in the 1970s and 80s is accelerated into a financier of the self.

We witness this imperative in, for instance, the enthusiasm for “financial literacy” education for children and adults which almost always obscures or mystifies the sociological sources of poverty, debt and economic precarity and, instead, instructs individual learners to embrace a world of risk. It can also be observed in the popularity of reality television where house-buyers, antique hunters or junk collectors are celebrated for their quotidian financial skills. In general, for Martin, financialization implies the “profaning” of the future, the narrowing of personal and collective horizons towards an endless “now.” To the extent we are each instructed to turn our imaginations towards mapping out the future as a grid of cost and benefit, risk and reward, any sense that the future of society might be different recedes from individual and collective view.

My contribution to this debate was to draw on the work of Castoriadis, as well as David Graeber, to explicitly insist on the importance of the imagination to this process. Financialization doesn’t kill the imagination, it excites, conscripts and harnesses its power. And, in turn, financialization, as a social process, depends on the imagination. It not only depends on the imagination of financiers who invent highly creative, if diabolical, ways of making money out of money. It also depends on nearly everyone, even the world’s poorest people reimagining themselves as financialized subjects and reimagining their world as one of assets, risks and potential rewards. In later work, I theorized that it is, in fact, this financialized imagination that is fertile ground for the growth of the kinds of reactionary, far-right and (post-)fascist ideological ideology and activism that have recently proven themselves so profoundly dangerous to any truly democratic project.

At the same time as I was developing this theoretical work, I also began what would become a decade-long collaboration with my colleague Alex Khasnabish to mobilize insights from Castoriadis to develop a methodology for studying with social movements. We were also deeply inspired by Robin D.G. Kelley’s phenomenal work on the Black radical imagination. We identified two dominant strategic trends in scholars who seek to work in solidarity with movements: sometimes they simply seek to invoke those movements in their writing, dignifying them with attention and offering outside reflections; other times scholars embrace a strategy of avocation, putting their time, skills and resources at the disposal of those movements. There are merits to both, but we wanted to experiment with a strategy we came to call convocation. How might scholars be active in calling together social movement actors to have conversations or encounters they might not otherwise have, in the name of opening and holding a space for the radical imagination to spark and catch light? For the better part of a decade, we experimented with this approach in the conservative Canadian city of Halifax, where progressive movements were generally far from successful. How did they sustain hope and energy in the face of so little success? We theorized that most movements dwell in a space between success and failure, and that critical scholars, working in solidarity, have a role to play in fostering moments of critical reflection and communion that movements rarely create for themselves.

In 2017 I took up a new position as Canada Research Chair in Culture Media and Social Justice (later Canada Research Chair in the Radical Imagination) at Lakehead University in the small, very remote Canadian city of Thunder Bay, a place plagued by extremely violent anti-Inidgenous racism. There, I took the insights from the Radical Imagination Project to found RiVAL: The ReImagining Value Action Lab as a platform for fostering research and organizing public outreach on topics of social justice, decolonization and the radical imagination. With the support of the Canada Research Chairs program and the Canadian Foundation for Innovation we have, in the past 5 years, offered dozens of workshops, held film screenings and public talks and worked closely with grassroots anti-racist and anti-poverty movements on these themes.

The lab has also been a platform for my international scholarly activities. In addition to fostering my further research into financialization we have been exploring new participatory methods for bringing academics, artists, activists and diverse publics together to “convoke” the radical imagination. For example, we have organized collectively-created walking tours of the financial districts of London and Toronto to explore financialization from new, embodied perspectives. We have begun to integrate podcasting into the way we explore issues and develop communities of common inquiry. And we are in the process of developing a board game lab to explore the way analogue game design can be a method for theorizing and catalyzing a discussion around difficult social issues. Our first game, Clue-Anon, explores why conspiracy theories are both so fun and so dangerous.

The post A reflection on the radical imagination: From finance to social movements to games (Junkyard) appeared first on Max Haiven.

A reflection on the radical imagination: From finance to social movements to games

This piece was first published on April 27, 2022 by The Junkyard: A scholarly blog devoted to the study of imagination.

As a child, I was slow to learn, not because of any specific diagnosable developmental delay but because of some deep, abiding and often angry skepticism towards anything that seems to me to be an arbitrary social convention that was presented as an unquestionable truth. For example, I remember being called before the class for some task in school at the age of 7 or 8, only to inadvertently reveal I could not tell my right from my left. Red-faced, I threw a tantrum before my shocked and bemused classmates, explaining that the distinction was purely conventional, calibrated solely by, so far as I could tell, the doctrines of our forebears. Such orientation was a form of guided narcissism, rather than a material point of reference: My left, I ranted from in front of the room, was my classmates’ right, after all. Why do we even use these words? Wasn’t it a matter of arbitrary perception being passed off as an iron law of nature. How many other things had we been taught as truth that were, in fact, habits of collective thought? What made North up and South down? Why did certain letters have to make the sounds we associated with them when they were all funny symbols that exist nowhere in nature?

I relate this anecdote not to impress or terrify the reader with my childish precociousness: credit here really ought to go to my parents and teachers who humored and tolerated this stormy little self-styled philosopher; it can’t have been easy. Rather, I think it’s a revealing place to start an account of what has been a life-long interest–perhaps an obsession–with the power of the imagination to shape our collective life. Just because the distinction between right and left is, ultimately, a figment of the collective imagination, that doesn’t make it any less real. Money is equally an invention of the imagination, but try to survive in a capitalist society without it and you run into very real difficulties. The way the imaginary becomes real, and the way reality shapes the imagination, is a riddle that has sustained my curiosity.

Growing up in a household of activists must have made its contribution to my skpeticial disposition, and it would later lead me, as a young adult around the turn of the millennia, to become an organizer in Canada in what was then called the alter-globalization movement, then, quickly following that, the anti-war and anti-racism struggles surrounding the advent of the War on Terror. I witnessed the power over the imagination of the neoliberal discourse of the End of History, what Mark Fisher would later call “capitalist realism.” In spite of the manifold injustices in the global capitalist order, the abiding belief that this was the best of all possible systems, or that in any case it was impossible to change matters, was profoundly demobilizing. I sensed, in the course of my activism, that, while not without some success, my comrades and I were only ever reaching about 5% of the population with our impassioned calls for global solidarity. Part of the problem, I realized at the time, is that most people had convinced themselves that the reigning order was natural, normal or inevitable. But many more simply had no time, or were denied the opportunity, to imagine the world broadly, and to recognize that much of how the world works is an arbitrary human construction, held in place by convention and unquestioned belief in the status quo. Worse still, capitalism increasingly seemed to find ways to seduce and co-opt the imagination, a trend that has reached a fevered pitch in the gig economy and in influencer culture, where we are told that expressions of our creative imagination can be our ticket to fame, riches or even simply a modicum of material stability in an otherwise unstable world.

This led me to enroll in graduate school, in a then-new program in the then-topical Globalization Studies. It was here that I came first into contact with the theories of Cornelius Castoriadis, the Greek-French philosopher of the radical imagination. Castoriadis, who was a core protagonist in the influential French journal Socialisme ou Barbarie in the late 1950s and early 1960s, sought to merge the insights of Marxism and psychoanalysis while, at the same time, discarding the more conservative dimensions of both traditions. His work would become highly influential on a generation of students and workers who, in 1968, almost brought down the French government through militant protests and strikes. For Castoriadis, the radical imagination was not the property of this or that ideological position but a fundamental force in all human affairs, active underneath society and within each and every social subject. Castoriadis’s ontological claim was that the imagination is the protean stuff out of which both subjects and institutions are made, a magma-like, flowing substance, between liquid and solid, that flows beneath the surface. Like magma, when it erupts it soon solidifies, and we take these solidifications as hard, fast and eternal, forgetting their tectonic origins. But both on the level of the subject and society at large, another eruption awaits, which will either be channeled by the existing crystallizations to reproduce their order or sweep them away to make room for new institutions.

Like Castoriadis, I became fascinated by the way the unique socioeconomic system of capitalism both relied on and shaped the imagination. The highly mediated capitalism of early 21st century Canada was, of course, quite different than 1950s France, and my interest increasingly gravitated towards the way the imagined systems of human categorization organized around the idea of “race” (a pure fiction invented to justify imperialism, but which became and remains deadly real) continued to have such sway and to be one of the key ways that exploitation and inequality was reproduced in the interests of corporations and the extremely wealthy. But I also, starting in 2005, became fixated on another intersection of capitalism and the imagination that was to captivate everyone’s attention a few years later: the financial sector.

In the wake of the 2008 global financial meltdown many commentators and theorists sought to understand how the arcana of finance caused such chaos: credit default swaps, collateralized debt obligations, structured investment vehicles and other derivatives seemed to be figments of the contorted imagination of Wall Street bankers calculated to clothe naked exploitation in the garb of scientific calculation. But I argued that is only part of the story, and the least interesting part at that. More broadly, a process that critics have called “financialization” has not only seen the growing wealth and power of the financial sector around the world, it was leading to profound social and cultural transformations. Here, I drew deeply on the work of New York University’s Randy Martin, who would later host me as a postdoctoral fellow in 2011, shortly before his tragic premature death four years later. For Martin, financialization also meant the way each and every social subject is encouraged to embrace and adopt the dispositions, ideas and value system of finance, even if they have nothing to do with the movement of stocks or bonds. In a neoiliberal age, where forms of public social security have been cut or privatized, we are all instructed, sometimes explicitly, more often implicitly from a million cultural points, to see ourselves as savvy risk-managers, navigating a world of opportunities for personal enrichment and betterment. Education is recast as an investment in one’s human capital; housing is recast as a financial opportunity or liability; in an age of the gig-worker, one’s passions, hobbies, personal networks, friendships and dispositions all become assets to be put in play. The entrepreneurial self theorized by Michel Foucault and Nicholas Rose in the 1970s and 80s is accelerated into a financier of the self.

We witness this imperative in, for instance, the enthusiasm for “financial literacy” education for children and adults which almost always obscures or mystifies the sociological sources of poverty, debt and economic precarity and, instead, instructs individual learners to embrace a world of risk. It can also be observed in the popularity of reality television where house-buyers, antique hunters or junk collectors are celebrated for their quotidian financial skills. In general, for Martin, financialization implies the “profaning” of the future, the narrowing of personal and collective horizons towards an endless “now.” To the extent we are each instructed to turn our imaginations towards mapping out the future as a grid of cost and benefit, risk and reward, any sense that the future of society might be different recedes from individual and collective view.

My contribution to this debate was to draw on the work of Castoriadis, as well as David Graeber, to explicitly insist on the importance of the imagination to this process. Financialization doesn’t kill the imagination, it excites, conscripts and harnesses its power. And, in turn, financialization, as a social process, depends on the imagination. It not only depends on the imagination of financiers who invent highly creative, if diabolical, ways of making money out of money. It also depends on nearly everyone, even the world’s poorest people reimagining themselves as financialized subjects and reimagining their world as one of assets, risks and potential rewards. In later work, I theorized that it is, in fact, this financialized imagination that is fertile ground for the growth of the kinds of reactionary, far-right and (post-)fascist ideological ideology and activism that have recently proven themselves so profoundly dangerous to any truly democratic project.

At the same time as I was developing this theoretical work, I also began what would become a decade-long collaboration with my colleague Alex Khasnabish to mobilize insights from Castoriadis to develop a methodology for studying with social movements. We were also deeply inspired by Robin D.G. Kelley’s phenomenal work on the Black radical imagination. We identified two dominant strategic trends in scholars who seek to work in solidarity with movements: sometimes they simply seek to invoke those movements in their writing, dignifying them with attention and offering outside reflections; other times scholars embrace a strategy of avocation, putting their time, skills and resources at the disposal of those movements. There are merits to both, but we wanted to experiment with a strategy we came to call convocation. How might scholars be active in calling together social movement actors to have conversations or encounters they might not otherwise have, in the name of opening and holding a space for the radical imagination to spark and catch light? For the better part of a decade, we experimented with this approach in the conservative Canadian city of Halifax, where progressive movements were generally far from successful. How did they sustain hope and energy in the face of so little success? We theorized that most movements dwell in a space between success and failure, and that critical scholars, working in solidarity, have a role to play in fostering moments of critical reflection and communion that movements rarely create for themselves.

In 2017 I took up a new position as Canada Research Chair in Culture Media and Social Justice (later Canada Research Chair in the Radical Imagination) at Lakehead University in the small, very remote Canadian city of Thunder Bay, a place plagued by extremely violent anti-Inidgenous racism. There, I took the insights from the Radical Imagination Project to found RiVAL: The ReImagining Value Action Lab as a platform for fostering research and organizing public outreach on topics of social justice, decolonization and the radical imagination. With the support of the Canada Research Chairs program and the Canadian Foundation for Innovation we have, in the past 5 years, offered dozens of workshops, held film screenings and public talks and worked closely with grassroots anti-racist and anti-poverty movements on these themes.

The lab has also been a platform for my international scholarly activities. In addition to fostering my further research into financialization we have been exploring new participatory methods for bringing academics, artists, activists and diverse publics together to “convoke” the radical imagination. For example, we have organized collectively-created walking tours of the financial districts of London and Toronto to explore financialization from new, embodied perspectives. We have begun to integrate podcasting into the way we explore issues and develop communities of common inquiry. And we are in the process of developing a board game lab to explore the way analogue game design can be a method for theorizing and catalyzing a discussion around difficult social issues. Our first game, Clue-Anon, explores why conspiracy theories are both so fun and so dangerous.

The post A reflection on the radical imagination: From finance to social movements to games appeared first on Max Haiven.

Far from Ukraine, Putin’s War Worsens Palm Oil Crisis (Boston Review)

This article appeared on April 27, 2022 in Boston Review. The title is slightly misleading as the bulk of the article is actually about the long entanglements of war, empire and palm oil, with the ongoing Russian invasion as the jumping-off point.

In the global protests against Vladimir Putin’s “special operation,” the sunflower has become a potent emblem of solidarity with Ukraine, for which it is not only a national symbol but a key export. Native to the Americas, it was established in Eastern Europe by the turn of the nineteenth century, and ever since Ukraine and Russia have cultivated it and prized its oil. Together the two countries now produce at least 70 precent of the globe’s sunflower oil.

Ukraine and Russia produce at least 70 precent of the globe’s sunflower oil. But the invasion has disrupted this export, sending the global price of all cooking oils skyrocketing.

But the invasion has disrupted this export, sending the global price of all cooking oils skyrocketing. This has forced fast and processed food companies to scramble for alternatives. The resulting price hikes on these commodities threaten to put an essential foodstuff, cooking oil, out of reach for many of the world’s poor. And it has caused a dangerous resurgence of palm oil as a substitute, to the great dismay of environmental and human rights campaigners. This demand has so greatly increased the market value of palm oil that Indonesia, which exports 56 percent of the world’s supply, announced this week that it would halt all exports until it could secure its own country’s food supply. This move will certainly only further destabilize markets.

Over the past decades, environmental and human rights organizations have had some measure of success in drawing attention to the dire impacts of palm oil production, notably in Indonesia and Malaysia, which together export 85 percent of the world’s supply, as well as in Latin America, West Africa, and other tropical regions where oil palms are grown. Taking inspiration from earlier consumer-oriented campaigns to associate diamond mining with war and violence, several large global NGOs have used the term “conflict palm oil.” The term seeks to draw attention to the link between the expansion of palm oil plantations deep into tropical forests and the systematic abuse of workers and the environment. The expansion of oil palm farming is often accomplished through violent land-grabs that robs Indigenous people and peasants of their traditional territories. Palm barons are known to employ gangs and death squads to intimidate or murder journalists, trade unionists, and environmentalists.

In the last decade, a number of high-profile brands, including Iceland-brand frozen foods and Barilla (the world’s largest pasta maker), have bowed to pressure and removed palm oil from their products, turning to sunflower, soy, coconut, and other oils as substitutes. Others have pledged to purchase only from suppliers who abide by voluntary (and dubious) “sustainable” benchmarks. But with prices of alternative oils rising as markets rush to compensate for the disruption to Ukraine’s and Russia’s sunflower exports, those modest advances are in jeopardy. Palm oil remains a reliably cheap, readily available alternative. Environmental campaigners fear another wave of land-grabbing and forest-burning for palm oil production will follow, as happened in the wake of decisions in the United States (2007) and EU (2009) to increase the proportion of ethanol in gasoline, leading to a boom in the market for biofuels.

But the link between palm oil and war has a longer history, and that history has a lot to teach us about the capitalist economy of which we are a part.

Palm oil has been used for millennia in West Africa, where it remains not only a staple of the diet but also a substance freighted with cultural, spiritual, and economic significance. The term “palm oil” refers in fact to two separate products: the oil pressed from the fleshy orange seed bunches of the oil palm, and the distinct, harder-to-access oil locked in the kernels. While oil can be extracted from at least three different palm species, Elaeis guineensis, native to West Africa, is the most common cash crop. In its native region, the cultivation, harvest, and refining of its fruits have often constituted the bedrock of economic relations. As oil palm historian Jonathan Robins reports, it was critical to trade relations between the regions’ kingdoms and empires, including during the period of the transatlantic slave trade. But it was only after the British Empire banned the slave trade in 1807 that Liverpool’s merchants, denied their source of wealth, began to take an interest in the substance. Europe’s industrial revolution demanded lubricants for factory machines and the locomotives that brought their goods to market.

What palm oil’s story reveals is that, beyond the episodic disruptions of supply chains by “hot” conflicts, like Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, there is a deeper current of violence.

Soon, industrial chemists learned how to refine the pungent orange oil to manufacture, among other things, soap and candles. It also became vital to the miraculous new technology of preserving food in tin cans. Tinned food enabled the safe transportation of food throughout the empire, a necessity as troops were stationed in tropical zones where supplies easily spoiled and poisoning by locals was feared. All of this was make possible by the artificially cheapened labor of Africans, who cultivated, harvested, processed, and transported palm oil to the coasts, first under local taskmasters and later on European plantations in Africa.

These newly cheap commodities were sold to European consumers by companies like Lever, ancestor of today’s Unilever, still one of the world’s largest consumers of palm oil. They were promoted as the shared bounty of empire, benefiting rich and poor alike. Innovations in advertising driven by the soap, candle, and canned goods industries propounded a repertoire of racist imagery that still haunt us today, depicting Africans as desperate and thankful for European consumers’ largesse. European consumers were told that buying palm oil goods would gently, through the magic of the market, even help to defeat African slavery.

The reality, of course, is that, in the name of free trade, British and other European powers licensed themselves to invade Africa’s civilizations, slaughter military and civilian targets alike with machine guns, depose rulers, and impose exploitative trading relations that were anything but “free.” All this was undertaken in the name of securing the export of cheap palm oil and other commodities. Key to palm oil’s global trade, and to Europeans’ successful push inland into West Africa, was the advent of the steamship, its gears lubricated by palm oil too. For all these reasons and more, I have dubbed palm oil the grease of empire.

A short recounting of the 1897 British invasion and destruction of the Edo Kingdom in present-day Nigeria helps to illustrate how palm oil was central to the machinations of empire. In Edo, the British consul, in service to the empire’s merchant capitalists, orchestrated the conditions where his trade envoy would be attacked for ignoring the travel restrictions of Edo’s oba (king). This in turn justified the mobilization of a “punitive expedition,” complete with rockets and machine guns, a campaign that was celebrated in the English press as a humanitarian mission to save the Edo people from their oba’s (salaciously exaggerated) rituals of human sacrifice. The invasion resulted in the complete destruction of Edo’s magnificent capital city, admired by European visitors since the sixteenth century for its impressive architecture and organization. The oba was tried for crimes by a British tribunal and forced into exile. The upshot: the kingdom’s palm oil was secured for European import. Among the additional spoils of war were thousands of art objects collectively known as the Benin Bronzes. To this day, most are still incarcerated in European collections and museums, though there is a growing global movement to see them returned. That repatriation inspired the opening scene of Black Panther (2018), in which the villain, Killmonger, stages a daring raid on a museum that unmistakably resembles the Sainsbury Wing of the British Museum, where the largest collection of the bronzes is kept.

As the Industrial Revolution and the age of empire proceeded, palm oil found new uses. It was still too stigmatized by its association with Africa, and with industrial application, to be marketed as a source of cheap edible fat in Europe, despite the growing destitute urban proletariat and shortages of butter and lard. It was, however, a cheap and ready source of glycerin which, when combined with nitric acid, produced a volatile explosive substance that promised to revolutionize warfare. When, in 1867, Alfred Nobel discovered a way to fix nitroglycerin to clay in his lab near Hamburg, dynamite was born. Seventy-six years later, in 1943, the British Royal Air Force’s Operation Gomorrah would use the refined fruits of Nobel’s invention to almost completely raze Hamburg and kill 37,000 civilians in the span of a week, only one of many examples of the devastating impact of such explosives when combined with air power.

True: explosives also put a powerful weapon in the hands of working-class and anti-colonial rebels around the world, who could steal it from work sites and use it to target kings, conquerors, and capitalists in their carriages, homes, and clubs. But the myth of the deranged, bomb-hurling anarchist, like today’s myth of the terrorist, in fact helped distract attention from a far greater violence. Around the world, explosives were being used to blast open rockfaces and level terrain for railways and mining, leading nearly everywhere to new frontiers of resource extraction and labor exploitation, with catastrophic environmental and humanitarian consequences that haunt us to this day.

British and other European powers licensed themselves to invade Africa’s civilizations and slaughter military and civilian targets alike, all in the name of securing the export of cheap palm oil.

The “opening” of the American West, for example, and especially the transit of railways through the Rockies to resource-rich California, was accomplished with the help of dynamite, at the horrific expense of debt-bonded Asian workers who were often killed in the explosions or buried alive by the resulting rockslides. The toxic effluent from new mines in those territories was a significant contributor to the genocide waged against Indigenous nations.

Southeast Asia was another such location of rapacious empire-building and resource extraction. Whereas once European empires had been content to dominate coastal entrepots, new technologies including explosives, steamships, and railways allowed entrepreneurs to expand inland, including to establish plantations cut out from the lush tropical forests. With imperial troops (and hired gangs) nearby to put down revolts and a ready supply of displaced, migrant workers at their disposal, European capitalists made vast fortunes growing export-oriented crops, including oil palms. Soon the territories that would, after decolonization, become Indonesia and Malaysia displaced West Africa as the world’s leading exporters of palm oil, and so they remain.

The catalog of violence unleashed by plantation owners and colonial governments is chilling. This horror was abetted by the cunning with which they manipulated preexisting and fabricated ethnoreligious tensions to sabotage worker solidarity. Debt-bonded and enslaved laborers, many of them dispossessed by British imperialism in the Indian subcontinent, were made to try to survive deadly working conditions, pestilent accommodations, and brutal overseers. Plantation managers did not find it untoward to report mortality rates in excess of 10 percent a season due to accidents, disease, and violence. In Sumatra, at least a quarter of workers died as the result of their exploitation in the last decades of the nineteenth century. When workers rose up—and they indeed did—plantation owners were largely free to suppress them with lethal force, or to call on colonial forces to target not only the workers but their communities as well.