Max Haiven's Blog, page 4

July 11, 2023

The Workers’ Speculative Society podcast

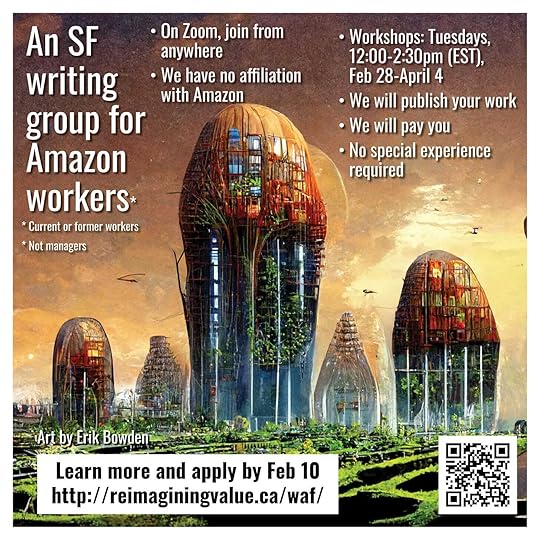

I’m pleased to announce the launch of The Workers’ Speculative Society, an interview-driven podcast about the future Amazon is building and the workers, writers and communities that are fighting for different worlds.

We begin on July 11 with an interview with Marc McGurl, author of Everything and Less: The Novel in the Age of Amazon, about Amazon’s sci-fi narrative and the fate of literature in a moment when one unscrupulous corporate empire controls so much of what we read.

Future guests include:

Charmaine Chua on logistics and workers’ strugglesRobin DG Kelley on workers, writing and the radical imaginationCory Doctorow on Amazon’s “chokepoint capitalism”Syrus Marcus Ware on Black futures and activismDavid A. Robertson on Indigenous speculative fictionAlessandro Delfanti on Amazon’s robots and warehousesLeonika Valcius on the work of literary agentsJamie Woodcock on wrtiting as workers’ inquiryThe podcast is part of the Worker as Futurist project, which supports rank-and-file Amazon workers to write and publish short works of speculative fiction about “The World After Amazon.” You can learn more about that project here and read some of the things we’ve written about it here.

To listen online you can head over to our Soundcloud page. To subscribe in your podcast app, search for “RiVAL radio” and look for the logo of RiVAL: The ReImagining Value Action Lab (below). You can also use this RSS address to subscribe directly. Or find us on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts or Spotify.

The post The Workers’ Speculative Society podcast appeared first on Max Haiven.

May 1, 2023

Climate Workers of the World Unite? (BG)

This text was commissioned by the Berliner Gazette for their 2023 project Allied Grounds. It is in English here and German here.

Climate Workers of the World Unite? The Quest for Affective Connections, Common Enemies, and Shared NarrativesIn their provocation for the 2023 project “Allied Grounds,” the Berliner Gazette challenges ‘us’ to imagine the scope for solidarity and action if ‘we,’ workers of the world, in all ‘our’ diversity and with all ‘our’ divisions, come to see ‘ourselves’ as co-creators of the climate. Here, co-creation is not a voluntary or intentional process, at least not yet. Today, ‘our’ cooperation on a global scale is mediated and largely commanded by capitalism. It is this capitalist world system that shapes ‘our’ scope of action, that provides incentives and punishments that constrain ‘our’ agency and arrange ‘us’ into hierarchies of power and privilege. In so doing, capitalism conditions and even leads ‘us’ to destroy the life support systems of the planet and also the lives of most people.

It is this assemblage of human and non-human life support systems and human socio-economic spheres that the authors of the call have in mind when they speak of the climate. In this sense, the climate is not only the literal gaseous atmosphere that enfolds the planet, where concerns about greenhouse gasses and other pollutants have captured our attention and fear in recent years. Additionally the climate is, seen through a kind of intersectional lens, those shared but segregated spheres that ‘we’ all inhabit and shape through politically and economically interconnected systems of which ‘we’ are each a product, and producer and a part. In this sense, ‘we’ climate workers of the world are producing the climate even when we engage on social media, or go shopping, or build new forms of neighborhood-level mutual aid. This is especially so as capitalism expands to consume ever more of the life-world and seeks to transform nearly all human activity into some form of work: activity mediated or shaped by market forces.

“How can the global proletariat emerge from new class struggles that derive their vitality from the multiplicity of laboring subjects – from gig jobbers in Bucharest, agricultural workers in the eastern region of Ghana, electronics manufacturers in Zhengzhou, coders in Mumbai, illegalized migrants in Berlin, Black and Latinx cleaners in Los Angeles, sex workers in Nairobi, care workers in Barcelona, teachers in Tehran, and no-bodies… managed as a surplus population and disposable labor pool in detention centers, hotspots, and camps around the world.”

I want to hold on to the radical potential of ‘us’ mobilizing around the notion ‘we’ are all, no matter what work ‘we’ do (paid or unpaid, formal or informal) climate workers. I believe this approach has a great deal of potential and so I want to give it close attention. In particular, I would like to constructively challenge this optimism by looking at what has made the labor movements of the past strong and what, in contrast, makes the climate workers of the world look rather weak. This said, I am not nostalgic for the workers’ movements of the past: they had many failings and we are in a very different moment, a moment where we have to truly think and act on a planetary scale. However, in bringing up those qualities that previous ‘workers of the world’ possessed, I want to open the door to future conversations about what we contemporary climate workers of the world might have to do.

Affective connections and common enemiesIn the heyday of the labor movement in Western Europe, during the rise of industrial capitalism, workers had a great deal in common, including their enemies. Unlike today, when many workers sympathize with their bosses or believe that, if they work hard, they too could be a boss, in those earlier days class antagonism was rather sharp. Workers often lived in decrepit tenements owned by the same individuals who owned the factories where they toiled (or to people who belonged to the same private clubs). Class stained almost every aspect of life: not only how people worked or where they lived or where they lived, but also what they ate, how they entertained themselves, how families were organized, what love and sex looked and felt like, how people talked, joked and expressed emotion. Hatred of the owning class was palpable, only tamed by religious indoctrination (usually in churches controlled by the ruling class), a sense of isolation and futility, and racism – e.g., the British working class was not so ‘British’ after all, as Cedric Robinson has shown.

Labor organizers did not need to convince workers they were being oppressed and exploited but, rather that they could do something about it, and that there were millions of other oppressed people just like them around the country who could rise up together. If they did so in unison or in solidarity, they would be unstoppable. If they did so internationally, they would transform the world. There was more than a small element of revenge in these narratives, and justifiably so: most workers had seen friends or family killed or maimed in machines and would have first hand experience of the sneering impunity of bosses and overseers; sexual exploitation was rampant. Workers could literally look across the shop floor at their exhausted co-workers and see their common cause, could witness, first hand, how their creative and cooperative energies were being channelled and drained by factories that operated purely in the interests of private profits.

Can you mobilize a global movement on the basis of a common dread?

Today’s ‘climate workers’ have no such clarity. Certainly, most of the world’s working population continue to labor in factories or extractive operations where hostile relations with bosses and corporations are palpable. However, today, corporations that are owned by thousands of anonymous shareholders do most of capitalism’s dirty work, offering no clear villain. An increasing number of people also work in the formal or informal service sectors, or in public sector jobs where ‘the boss’ is less clear. Further, the global individualistic neoliberal revolution has encouraged most people to see themselves not as an oppressed worker but an entrepreneur. Many workers in the Global North also have pension, bank or other investments, which on some level make them petty owners of capitalist firms, or own houses which they see as investments. Beyond this, given the vast inequalities within the international division of labor, it is difficult for workers in enriched colonial countries and impoverished post-colonial countries to see eye-to-eye, especially given that the labor of those in the Global South in everything from mining to food production to manufacturing to services (like caregiving) tends to enrich the lives of white Northerners, though some benefit much more than others.

Further, while the workers of industrial capitalism in Western Europe, could watch their time and energy transmuted by capitalist institutions into profit, could bear direct witness to the alienation of their own powers, ‘we’ climate workers of the world hardly recognize ‘our’ own powers to collectively produce the climate. It is hard even in theory to make clear that we all possess an abstract alienated cooperative power to generate the climate, let alone to make this power tangible to rank-and-file workers. Older notions of the working class were frequently built on the physical experience of exhaustion, unfairness, and class hatred. What are the shared, embodied experiences of climate workers on which organizers can build? I suspect that what we share is terror at being on the runaway ghost ship of capitalism that, in areas as diverse as inequality, international nuclear conflict, climate chaos and AI development threatens to destroy life on earth. Can you mobilize a global movement on the basis of a common dread?

This brings me to the final point: ‘we’ climate workers have no clear common enemy. Certainly there are convenient climate villains: the CEOs of fossil fuel corporations, for example, or the executives of the banks or the politicians who enable them. But each of these individuals would claim, not without justification, that they are simply following the rules of the globally competitive market and responding to consumer demands. Each knows they are completely and immediately replaceable and thousands of competitors are waiting for their chance to do the same or worse. Further, although it’s clear consumer activism is an utter dead-end, there is a truth to the rejoinder that we all, to different extents, bear some culpability for the climate crisis because we are all enmeshed in a consumer capitalist system that forces us all to participate in our own collective destruction whether we want to or not, often in ways we don’t even know about.

Such a critique rarely rises above the level of moralism, and has also been shaped by a neoliberal culture that sees the individual consumer or economic actor as the only source of meaningful agency. Still, however, it makes the question of responsibility blurry. It presents a considerable challenge for thinkers and organizers who would try and show ‘us’ how all ‘us’ climate workers share a single common struggle. Often we default to naming capitalism itself as the guilty party, but capitalism is not a thing with motivations or beliefs: it is a set of socio-economic relationships, a kind of vicious feedback loop within the circuitry of society, or perhaps a kind of virus that is quickly devouring its host. But how can ‘we’ climate workers of the world be mobilized to rebel together against a system of which we ourselves are a part?

The linchpinFriedrich Engels and Karl Marx provided an influential theoretical framework for understanding the labor movements during the rise of industrial capitalism. And while their primary concern was with workers in the industrialized Global North, their writings became important to various figures in the Black Radical Tradition, such as W. E. B. Du Bois, C. L. R. James, Walter Rodney, Cedric Robinson, who appropriated historical materialism as a theory of decolonization in the Global South. It is not my goal here to rehearse these important discourses, and even less to provide an inventory of the theoretical problems and mistakes. Rather, I am interested what the framework of historical materialism offered with regard to previous ‘workers of the world’ and what in turn could be useful as food for thought for today’s climate workers of the world.

Let us start by asking what it is that makes the class-organized social system, capitalism, so special and so vulnerable. In other class-based systems (for example European feudalism or the medieval Hindu caste system) there was certainly a tiny ruling class that organized and benefited from the work of the vast majority. But there the working class was profoundly geographically divided and had difficulty recognizing itself. Further, these earlier systems were not animated by the same spirit of relentless modernizing capitalism, which was, during Engel’s and Marx’s life, transforming nearly all aspects of life including farming, industrial production, household management, logistics, global trade, communication, and transportation. But in order to be so dynamic, capitalism was forced to rely on its own ‘gravediggers’: industrial workers. Rather than peasants or serfs isolated on estates, millions of industrial workers were crowded in slums and factories, increasingly in metropolitan cities in Western Europe.

Isolated peasant and plantation uprisings have been common around the colonial world, but were relatively easily repressed through brutal violence, leaving the blood-soaked land to be harvested the following year by their replacements. By contrast, uprisings of urban industrial workers not only saw coordinated action among thousands of workers but also often destroyed the technology and infrastructure of capitalist production. Further, capitalism’s relentless economic and technological ‘progress’ meant that large numbers of workers were routinely thrown out of work. It’s economic volatility led to price and wage fluctuations that threatened to starve workers. This led to unprecedented uprisings.

Is there some special power in the strike or riot or refusal of ‘climate workers’ that strikes deep at the heart of capitalism? If so, what is it?

As Harry Cleaver notes in his famous worker-centric “Reading Capital Politically,” Karl Marx wrote “Das Kapital” to place a weapon in the hands of the industrial working class: it explained why capitalism was unique among all class systems in human history, and uniquely vulnerable to the very people it exploited: mass workers. Indeed, at the time Marx and Engels wrote “The Communist Manifesto” they were in the minority even among radicals in seeing any revolutionary potential among mass workers: skilled industrial workers appeared to be the real revolutionary protagonists, at the forefront of strikes, riots, and uprisings in the momentous first half of the 19th century. Marx and Engels were relatively solitary in seeing the mass, deskilled, hyper-exploited, often migrant worker as having truly structural revolutionary potential, even though at the time there were seen by many radicals as a reactionary force, willing and even eager to break the strikes of skilled workers in their desperation for wages.

Attempting to show how the industrial working class had the power already within their hands, Engels and Marx were seeking to demonstrate how capitalism uniquely depended on this class, and therefore how this class’s protagonism could uniquely bring down that system while preserving its technological advances in the name of a future, classless society. In short: From one fundamental contradiction within the system crucial strategic possibilities emerged: capitalism was destined to generate a working class on which it was dependent, and that could destroy it.

Do ‘we’ climate workers of the world have any such narrative or theory? Certainly we can say that climate-chaos capitalism depends on harnessing our creative-cooperative powers as workers to generate shared but segregated spheres that, by and large, deliver profit to capitalists at the expense of everyone and everything else’s well-being. But this is not quite the same, especially at a moment when it capitalism’s technological push threatens to make it possible (though rarely profitable) to replace human workers with robots and artificial intelligence (although one should take such prophesies with a large grain of salt).

In recent years, theorists informed by Marxist feminism have encouraged us to shift our attention to capitalism’s primary reliance on the reproductive labor typically forced onto women, both the caring labor done in the home to reproduce life as well as in the formal and informal labor market as more and more acts of care are commodified and rendered services. Anti-colonial theorists and activists have drawn our attention to the way capitalism has always relied upon racial and geographic hierarchies to render up cheapend labor and resources. These have both been efforts to refocus our attention on what is often framed as the strategic lynchpin of capitalist accumulation, which can inform our priorities in theorizing and organizing against capitalism.

It remains an open question if the climate crisis can provide such a lynchpin, and to what extent the term climate workers names a strategically significant category around which we can mobilize. In “Climate Change as Class War: Building Socialism on a Warming Planet” Matt Huber focuses our attention on the crucial role of highly-unionized energy sector workers. But this is a much more limited notion of both ‘workers’ and ‘climate’ than the Berliner Gazette has in mind.

Is there some special power in the strike or riot or refusal of ‘climate workers’ that strikes deep at the heart of capitalism? If so, what is it? If not, is ‘climate worker’ just one more identity among many to be taken up voluntarily by people (and which people?), and therefore perhaps just as easily cast aside at the end of the day when a new identity feels more appropriate or when a new crisis looms larger on the horizon? Perhaps it is that ‘the climate’ represents one of the truly unified existential threats to the future of all workers. But then we are back at where we started, the problem whether and how climate workers of the world can be mobilized around dread. And, further, there is probably nothing about workers dread that would in and of itself cause capitalism to crumble – probably quite the opposite as such anxieties are easily and tragically mobilized by reactionary and fascist forces promising stability and revenge.

A prophetic narrative?For over a century, Marx and Engels’s theories were appropriated and adapted to inform militant and revolutionary working class agitation (and its reformist rump) as well as strategic analysis. It was not simply that these theories showed the weak points of capitalism, they also promised the near inevitability of proletarian revolution. Capitalism’s industrial workers not only could overturn capitalism, they were, in this view, uniquely situated in world history to liberate humanity from class altogether and create the first truly classless society. It offered theorists and organizers a prophetic narrative that helped create movements capable of tremendous ambition and self-sacrifice. And my concern here is with what such a narrative makes possible in terms of theorizing and organizing, and if the suggested approach to see ourselves as climate workers of the world has or needs any similar prophetic narrative.

Today, the only thing that feels inevitable about the climate catastrophe is that it’s going to get worse. Most projections into the future see life getting harder as crops fail and ‘natural disasters’ plague vulnerable populations, leading to greater migrations and hardships for billions of people. We are asked to take action not for a bright and promising future, but simply to mitigate the worst impacts. Can such a grim narrative mobilize a sufficient number of people around the world, or even in any one jurisdiction, to take the considerable risk of fighting for a revolutionary change? Nothing less than a revolutionary change is needed today, though what form that revolution will take is uncertain.

This gloomy narrative certainly pales in comparison to those of previous ‘workers’ of the world.’ These triumphant prophesies foretold the proletariat’s destiny to seize upon its unique world-historical mission and overthrow capitalism and liberate that system’s technological and productive apparatuses for the common good. In the most mystical reaches of Marxism, including the famous Walter Benjamin, this historic task was nothing less than messianic: the redemption of the dreams of the dead, the arrival of God’s kingdom on earth. Russian cosmism even anticipated a horizon where the liberated sciences of communism would allow the dead to live again alongside the living, among the stars. While these may seem outlandish, they indicate the kind of modernist optimism that was so inspiring not only to workers themselves but intellectuals who saw in the proletarian struggle the only escape from the deadlock of capitalism. Anti-colonial thinkers and organizers took up these ‘scientific’ methods to demonstrate how decolonization was inevitable and thereby inspire a generation of freedom fighters.

For workers themselves, this narrative not only served to justify incredible risks and self-sacrifice, it offered a heroic and triumphant vision of collective action. Even if you were to fall in revolutionary struggle (even if you were to fall to the machinations of your own overzealous comrades), your life would have been part of the redemption of humanity, the world-historical overthrow of exploitation once and for all. When this narrative of sacrifice became folded into Stalinist or Maoist statecraft, it became one of the most oppressive and terrifying weapons in the hands of leaders, who could use it to justify profound injustices. Many people still have resentful memories of being force-fed this dogma.

A triumphant, heroic narrative dignifies itself and its protagonists… It’s less about concrete hope for this or that future. It’s more about embodied feeling in the present, a sense that you have value, that your life has meaning, that the struggle is worth it not because it will deliver a better world but because it fills you and transforms you. Can ‘we’ climate workers of the world ever generate such an empowering narrative? And can we succeed in its absence?

Yet I wonder, aloud, if a new workerist narrative focused on climate protagonism could ever generate such a narrative, and if it should? Can we do without it? The dominant narrative today is tragic, it promises a life of struggle among ruins or, at best, an ambiguous future of degrowth that offers to exchange the unequally distributed material gratifications and ease of capitalism with a more universal and sustainable simplicity. Has any movement in history mobilized around such narrow and grim horizons? It’s not just that the future on offer appears lean and hard, however. That problem is less important than another: A triumphant, heroic narrative dignifies itself and its protagonists. In a world where ‘we’ are systematically devalued, it can give ‘us’ a story that valourizes ‘us.’ This can potentially give ‘us’ incredible courage and conviction, and fill ‘us’ with a spirit of sacrifice and potential. It’s less about concrete hope for this or that future. It’s more about embodied feeling in the present, a sense that you have value, that your life has meaning, that the struggle is worth it not because it will deliver a better world but because it fills you and transforms you. Can ‘we’ climate workers of the world ever generate such an empowering narrative? And can we succeed in its absence?

The post Climate Workers of the World Unite? (BG) appeared first on Max Haiven.

April 19, 2023

Sacrifice (Finance Aesthetics)

An edited version of the following text will be published in 2024 as part of Goldsmiths Press’s Finance Aesthetics: A Critical Glossary, edited by Frederik Tygstrup, Torsten Andreasen, Emma Sofie Brogaard, Mikkel Krause Frantzen and Nick Huber.

SacrificeMax Haiven2023-04-19

In a sense, the conspiracy theorists are right: we do live in a world of hideous human sacrifices, superintended by a financially enriched elite. But whereas the conspiracists hallucinate a coordinated cabal of evildoers, the more complex and the more disturbing truth is that the forms of human sacrifice that characterize financialization do not require (and would, in fact, be imperiled by) any such intentional orchestration of efforts. Rather, financialized capitalism must be reckoned as a system, one that reproduces a set of imperatives, enticements, rewards and punishments for competitive economic behaviour that, in only sum, creates an overall movement of capitalism towards a sacrificial world order. No individual needs to utter the prayers or wield the dagger for this system to enact human sacrifice. And whereas the conspiracist imagination fixates on the purity of the innocent victim, notably children, today’s sacrifices are not only individuals in all their complexity, but messy and entangled entities: the climate, the biosphere, the cultural fabric, the very possibility of the future.

The urge to misimagine systemic violence as the work of wicked individuals is not new; it is both symptomatic and constitutive of capitalism’s development. Marx and later Marxist analyses of anti-Semitism indicate how residual racist myths can furnish an explanation for socioeconomic pain and uncertainty among both elites and the exploited.[1] The recent Q-Anon “conspiracy fantasy,” which has gained terrifying worldwide popularity, rehashes many of these tropes with its seductive participatory narrative about a secret war being waged by the righteous against a cabal of blood-drinking child abusers.[2] Michael Taussig has likewise accounted for in his study of the reappearance of the devil in rural Latin America during periods of seismic economic change and social dislocation.[3] Silvia Federici’s account of the role of the witch trials in the development of capitalism’s phase of “primitive accumulation” likewise details how accusations that specific people (mostly but not exclusively women) were engaged in ritual and conspiratorial human sacrifice was key to the destruction of the commons and the uniquely capitalist renovation of patriarchy.[4] In all these cases, a charismatic narrative of human sacrifice, focusing on the evil intentions of individuals or groups, distracts political attention from the broader sacrificial social order.

The rise of conspiracism is typically the result of a combination of, on the one hand, a genuine effort by suffering people to understand a world that seems to be collapsing all around them and, on the other hand, the efforts of predatory manipulators, grifters and entrepreneurs. The line between the two is rarely sharp. This line is even more blurred in an era of financialization, where each subject is exhorted to recast themselves as a speculator and manipulator. The QAnon phenomenon, for example, sees a fluid movement between true believer and online huckster, thanks in no small part to the opportunities provided to monetize attention by corporate social media platforms.[5] But to focus on the cynicism and opportunism is to lose sight of the reality that such theories in fact take root not in obedience to dogma but in a misaimed critical thinking, in a skepticism towards dominant narratives, in a desire to discover and interrogate the workings of power, and in a more or less genuine humanitarian wish, all gone terribly wrong.

At stake is the poverty of a conspiratorial theory of power, which, in line with dominant neoliberal narratives, sees the world as defined by the intentional actions of powerful individual actors, rather than a more capacious critical theory that can analyze systemic and institutional power and, crucially, their contradictory nature.

Yet on a discursive level, a narrative of sacrifice has important systemic functions within such a system.[6] As Wendy Brown notes, under both the economic and cultural shifts of financialization, the notion of sacrifice has been crucial.[7] Individuals are expected to sacrifice time, energy, pleasure and health on the altar of homo oeconomicus in the hopes that idealized figure of competitive risk taking might offer his dark blessing in the form of a return on investment. On a broader political level, the forms of neoliberal policy and austerity, which might have once been cloaked in a rhetoric that suggested that a sacrifice today might bring better tomorrows, now admits that sacrifice is here to stay. In reaction, resurgent far right and fascist political formations today thrive in the environment of endless sacrifice. They gain traction by claiming only they can clearly see and manage the sacrifices that must be made for security: the restoration of the patriarchal family, murder on the border, expulsion, war.[8] It’s sacrifice or be sacrificed.

And yet behind and beyond these more ideological mobilizations of sacrifice is a deeper truth: the term financialization indicates what can be framed as a vast global order of human sacrifice. Here, thanks to the abstract movements of gamed markets, millions of people are condemned to death from completely preventable diseases or privation, or by the effects of anthropogenic climate chaos derived almost entirely from the past centuries of capitalist accumulation. Encoded in the interlaced digital legers of this financial empire is an authorless, decentalized sacrificial order with a metahuman bloodlust, hidden in plain sight. It’s a truth both obvious to everyone and also somehow unspeakable that the poor will die and suffer to protect the privileges of the rich and the competitive vitality of corporations.

Perhaps, however, while sacrifice offers an evocative and provocative metaphor for financialization’s forms of lethal indifference and unintended humanitarian and ecological catastrophes, it is a poor analytic tool. After all, can it be said to be human sacrifice if it is not intentional and not accompanied by religious ritual? Does the spectre of human sacrifice simply rehearse a longstanding vulgar critique of capitalism that, by calling up the spectre of an allegedly premodern barbarism, seek to cast down a hyper-modern political-economic system?

But maybe we have learned to think of human sacrifice the wrong way. Most of what we know about the practice of human sacrifice is irredeemably clouded by modern colonial prejudices that have sensationalized the violent practices of non-Western human sacrifice while ignoring or rationalizing Western, modern forms of human sacrifice. A vast diversity of civilizations practiced some form of human sacrifice at some time in their history, and for very different reasons.[9] While the practice perhaps seemed normal or at least justified in the eyes of those who practiced it, it has perennially been used by outside observers as evidence of barbarism. More often than not, it has been pointed to by outsiders and rivals as a justification for war or in some sense as a distraction from the accusers’ own sacrificial practices. As Tvetan Todorov noted, the sensational scenes painted by the conquistadors of the Aztec “society of sacrifice” helped justify that empire’s liquidation while at the same time mystifying the Spanish “society of massacre.”[10] I have written elsewhere about how the human sacrifices practiced by the Edo Kingdom (located in what is today Nigeria) was used by the British Empire as a justification to, in 1898, invade and destroy that Kingdom, part of a broader tendency towards a kind of capitalist imperialism that sacrificed millions of lives around the world on the altar of white supremacy Christianization and “free trade,” though of course it never understood itself as such.[11]

It is often assumed that the heinous practice of human sacrifice originated in the dark crypt of prehistoric mysticism. But recent evidence seems to suggest that, more often than not, orders of human sacrifice took form as societies became more stratified and imperialistic.[12] Though it may have been disguised in the trappings of religious necessity to appease fickle gods and ensure the continued vitality of the nation, typically elites used human sacrifice as a dramatic means to intimidate the lower classes, vassals and enemies. It was a convenient method for eliminating potential rivals and usurpers and for disguising state terror as cosmological necessity.

If such arguments are to be believed, human sacrifice was always already about what we, today, might call “risk management” on at least two levels. On the one hand, the elites who practiced it used it as a means to eliminate risks to their continued dominance and enrichment; on the other, they presented it to the world as an act undertaken for the public good, a regrettable necessity to control the uncertainty of supernatural providence. Were the sacrifice not made, the Gods might be angered, or might starve, portending doom for a whole society. It helps that, often, those sacrificed are not even considered fully human at all.

How unfamiliar and exotic to us are these metaphysical justifications, really? Today, defenders of global financialized capitalism legitimate its profound sacrificial violence with recourse to the idea that, somehow, to interrupt or intervene in it would be to jeopardize the spirit of economic growth: progress that is said to be universally beneficial. Few today would earnestly parrot the maxims of turn-of-the-millennium capitalist optimism, (eg. “a rising tide lifts all boats”). Yet in the dominant neoliberal ideological framework the progress of the market (its “creative destruction” and “disruptive innovation”) is said to lead to greater overall economic growth, technological innovation and a higher standard of living. It is even rumoured to lead to a “capitalist peace” and the “end of history,” where humanity’s inherent competitive and acquisitive urges are safely sublimated into market activity which, in aggregate, are universally beneficial.[13]

At stake for me in this comparison is the possibility that the cosmological dimensions of financialized capitalism might come into better view. Of course, financial markets are, in an extreme way, made up of a multitude of competing hyper-rational decisions.[14] Yet, while market philosophers like Hayek predicted that, left to their own devices, such markets would usher in a rational political-economic order, the reality is a largely irrational order where growing gaps in wealth are accompanied by profound ecological sacrifices as well as humanitarian catastrophes.[15] According to those thinkers, the market represented the apotheosis of reason, the emergence, for the first time in human history, of a kind of metahuman intelligence free of prejudice, superstition and bias.

At some level a global market-dominated society justifies the human sacrifices it demands in terms of a kind of regrettable but ultimately providential cosmological necessity: it is indeed terrible that those children died of malnutrition or preventable disease, but to prevent it would be to disrupt the transit of the holy market (by, say, raising taxes or by regulating free trade). Such profane actions would, ultimately, have more catastrophic consequences. Such consequences, we are told, might not only include the stagnation of economic growth but the appearance of the demonic forces of unfreedom.

If we look at the global financialized capitalist system from the right angle, squint and defamiliarize ourselves with the normalized justifications, it appears as an empire built on human sacrifice not unlike any other. But what is perhaps different is how the reigning cosmology of the market is how it shapes our actions and dispositions, whether we believe in the finer points of its theology or not. Financialization encourages each of us to adopt the dispositions of the imagined financier, the risk manager. I have suggested that this contributes to the conditions within which certain far-right and postfasicst ideologies can find footing.[16] The daily experience of uncertainty, insecurity, individualism and competitiveness reinforces a cosmological view of a universe made up of similarly uncertain, competitive, speculative beings.[17]

Within such an imagined world, ever greater human sacrifice can be envisioned and justified. The losers of a competitive system are now recast not as momentarily unlucky but fundamentally flawed, poor imitations of the idealized figure of financialization. Worse still, the dependency of the losers of financialization on the winners is, in a world of increasingly scarce resources and relentless competition, a threat to the continued success (and survival) of the winners. Financialization is in some sense a global order of human sacrifice in which we are all both participants and potential victims. Like the sacrificial empires of old, ours justifies its bloodletting in the name of cosmological necessity: the market demands it, and to fail to heed or feed the market would be to invite both personal and collective doom. In other sacrificial empires elites use mystical theology and gory spectacle to consolidate their rule, and claim that their sacrificial acts are in the public interest. Today, the sacrificial blade and altar are dematerialized and diffused. We are all, to greater or lesser extents, compelled to participate, even those who are destined to be sacrificed. Their sacrifice will typically take the form of invisibilized abandonment, rather than hypervisible ritual. Yet like other orders of sacrifice it stems from a largely unquestioned cosmology, a cosmology no one might actually fully believe in and yet which still structures our imaginations.

For Sylvia Wynter, the cosmology of homo oeconomicus is one whose origins stem from the Euroepan colonial project and transatlantic slave trade at the birth of the capitalist-imperialist system.[18] This cosmology, which I am here associating with sacrificial financialization, is both fundamentally built on racist notions of what it means to be human but also, in a global neoliberal age, suggests that homo oeconomicus is a model that all people can and should strive to emulate and embody. But its success in capturing the imagination and shaping the material world is bound up with the way it vanquishes or delegitimates many other “genres” of being human practiced by other civilizations, which it takes to simply be poor, unreflexive emulations of the truth of homo oeconomicus.If we are to have a chance of surviving cosmology of financialization we must, do nothing less than reimagine what it means to be human. Such a reimagining would be a material practice of rebellion and experimentation and would necessarily imply not the end of sacrifice, but a different mode of sacrifice, perhaps more in line with George Bataille’s theories that understand sacrifice as among the highest purposes for any society.[19]

Notes[1] Postone, “Anti-Semitism and National Socialism.”

[2] Wu Ming 1, La Q Di Qomplotto.

[3] Taussig, The Devil and Commodity Fetishism in South America.

[4] Federici, Caliban and the Witch.

[5] Wu Ming 1, La Q Di Qomplotto.

[6] Wang, Legal and Rhetorical Foundations of Economic Globalization.

[7] Brown, “Sacrificial Citizenship.”

[8] Haiven, “From Financialization to Derivative Fascisms.”

[9] Bremmer, The Strange World of Human Sacrifice.

[10] Todorov, The Conquest of America.

[11] Haiven, Palm Oil: The Grease of Empire.

[12] Watts et al., “Ritual Human Sacrifice Promoted and Sustained the Evolution of Stratified Societies.”

[13] Schneider and Gleditsch, Assessing the Capitalist Peace; Fukayama, The End of History and the Last Man.

[14] LiPuma and Lee, Financial Derivatives and the Globalization of Risk.

[15] see Martin, Knowledge LTD: Towards a Social Logic of the Derivative.

[16] Haiven, “From Financialization to Derivative Fascisms.”

[17] Komprozos-Athanasiou, Speculative Communities.

[18] Wynter and McKittrick, “Unparalleled Catastrophe for Our Species?”

[19] Bataille, The Accursed Share.

Works citedBataille, George. The Accursed Share: An Essay on the General Economy, Volume 1. Translated by Rob Hurley. New York: Zone, 1988.

Bremmer, Jan Nicolaas, ed. The Strange World of Human Sacrifice. Leuven: Peeters, 2007.

Brown, Wendy. “Sacrificial Citizenship: Neoliberalism, Human Capital, and Austerity Politics: Neoliberalism, Human Capital, and Austerity Politics: Wendy Brown.” Constellations 23, no. 1 (March 2016): 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8675.12166.

Federici, Silvia. Caliban and the Witch: Women, Capitalism and Primitive Accumulation. New York: Autonomedia, 2005.

Fukayama, Francis. The End of History and the Last Man. New York: Perennial, 1993.

Haiven, Max. “From Financialization to Derivative Fascisms: Some Cultural Politics of Far-Right Authoritarianism in an Era of Unmanageable Risk.” Social Text 41, no. 2 (2023): 45–73. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-1038....

———. Palm Oil: The Grease of Empire. VAGABONDS 4. London and New York: Pluto, 2022.

Komprozos-Athanasiou, Aris. Speculative Communities. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2022.

LiPuma, Edward, and Benjamin Lee. Financial Derivatives and the Globalization of Risk. Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 2004.

Martin, Randy. Knowledge LTD: Towards a Social Logic of the Derivative. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2015.

Postone, Moishe. “Anti-Semitism and National Socialism.” In Germans and Jews since the Holocaust, edited by Anson Rabinbach and Jack Zipes, 356–61. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1986.

Schneider, Gerald, and Nils Petter Gleditsch, eds. Assessing the Capitalist Peace. London: Routledge, 2013.

Taussig, Michael. The Devil and Commodity Fetishism in South America. 30th anniversary edition. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Todorov, Tzvetan. The Conquest of America : The Question of the Other. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Harper & Row, 1984.

Wang, Keren. Legal and Rhetorical Foundations of Economic Globalization: An Atlas of Ritual Sacrifice in Late-Capitalism. London and New York: Routledge, 2019.

Watts, Joseph, Oliver Sheehan, Quentin D. Atkinson, Joseph Bulbulia, and Russell D. Gray. “Ritual Human Sacrifice Promoted and Sustained the Evolution of Stratified Societies.” Nature 532, no. 7598 (April 2016): 228–31. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature17159.

Wu Ming 1. La Q Di Qomplotto: Come Le Fantasie Di Complotto Difendono Il Sistema. Rome: Alegre, 2021.

Wynter, Sylvia, and Katherine McKittrick. “Unparalleled Catastrophe for Our Species? Or, to Give Humanness a Different Future: Conversations.” In Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis, edited by Katherine McKittrick, 9–89. Durham NC and London: Duke University Press, 2015.

The post Sacrifice (Finance Aesthetics) appeared first on Max Haiven.

March 16, 2023

Board games as social media: Towards an enchanted inquiry of digital capitalism

The following text will appear in a forthcoming issue of South Atlantic Quarterly (SAQ) later in 2023.

AbstractCan board games be part of challenging the dangerous tide of reactionary cultural politics presently washing over the United States and many other countries? We frame this threat to progressive social movements and democracy as entangled with a cultural politics of reenchantment. Thanks in part to the rise of ubiquitous digital media, capitalism is gamified as never before. Yet most people feel trapped in an unwinnable game. Here, a gamified reactionary cultural politics easily takes hold, and we turn to the example of the Q-Anon conspiracy fantasy as a “dangerous game” of creative collective fabulation. We explore how critical scholars and activists might develop forms of “enchanted inquiry” that seek to take seriously the power of games and enchantment. And we share our experience designing Clue-Anon, a board game for 3-4 players that aims to let players explore why conspiracy theories are so much fun… and so dangerous.

KeywordsGames and gamification; digital capitalism; disenchantment; conspiracy theories and conspiracism; board games

Board games as social media within, against and beyond reactionary capitalism: Towards an enchanted inquiryMax Haiven, A.T. Kingsmith and Aris Komporozos-Athanasiou

2023-02-18

This essay argues that, in a moment when capitalism integrates games and gamification, cultural politics are increasingly marked by the appearance of participatory forms of play that seek to re-enchant a disenchanted world. Games have played a significant role in the social, political, and technical reproduction of late capitalism, especially its digital social media platforms. This occurs at the same time that life under neoliberal capitalism is felt by many as if trapped in an unwinnable game in a disenchanted world. This feeling is important to the cultural politics of our current moment. We take up the Q-Anon conspiracy fantasy as an important example of the way people play “dangerous games” together in (reactionary) response to this state of affairs. We also explore some of the ways the urge towards re-enchantment and participatory play elsewhere along the political spectrum. We conclude by previewing an experimental board game we developed, titled CLUE-ANON, which is intended to provide an alternative critical scholarly intervention: a form of play that moves away from the urge to debunk and disenchant by engaging instead with participatory reenchantment head-on.

Games, the first social media?The common use of the term social media refers to the engagement with recent digital platforms. But this approach unfortunately tends to obscure many of the other social activities that the digital revolution has enabled and their consequences for politics and activism (Fuchs 2021). This paper focuses on board games, a social media avant la lettre, and one that has quietly become consequential to an emerging cycle of movement struggles.

The kinds of objects and activities we, today, understand as board games have an ancient lineage (Masukawa 2016). The progenitors of board games may predate written language, and variations are abundant around the world. In another sense, board games as we know them are quite recent, with origins dating back to the commercial printing press (Flanagan 2009). Recent years have seen a massive expansion of the industry and the popularity of board games among a variety of consumers (Lutter and Weidner 2021). This process was well underway even before the Covid-19 pandemic and was spurred by the development of popular new games (notably the blockbuster success of Settlers of Catan) and the ways new digital retail platforms like Amazon circumvented the gatekeeping function of brick-and-mortar stores. User-driven platforms like the dominant Board Game Geek also helped players discover new games and develop a fan-base that encouraged independent designers and publishing companies to develop more specialized products (Wachs and Vedres 2021). The development in the 2010s of online platforms for playing board games remotely amplified this trend. Crowdfunding platforms have allowed independent game-makers and small game companies to produce high-quality games in ways that were not possible before, when the costs of developing, testing, designing, manufacturing and distributing board games placed the industry in the hands of a few dominant companies.

Of the many gaming subcultures to emerge over this period, several oriented themselves towards social movements for collective liberation and struggles for radical progressive social change. Already in the earliest days of commercial board games, the medium was recognized as a platform for efforts to educate players about politics, history, morality and appropriate behavior. It was also widely used as a platform for satirical social commentary (Booth 2015). In 1908, first-wave feminist activists in England published Suffragetto, which simulated the struggle between the London police and militants for women’s right to vote. The most famous example of a board game as a vehicle for social commentary was The Landlords’ Game, a critique of the rapacious greed of property speculators, which was later bastardized into a glorification of economic parasitism and marketed as Monopoly (Donovan 2017, 71–88). In 1978 Marxist philosopher Bertel Olman (2002) notoriously published Class Struggle, a Monopoly-like board game in which players take on the role of bourgeoisie and proletariat who seek to make alliances with other class factions (small business, farmers, students). The game ends either in revolution or nuclear annihilation.

By the 1980s, many social movement-aligned game makers were eschewing the conventional competitive idiom and designing cooperative games that aimed to instill feminist and other social justice values (Ross n.d.). In the 2010s and early 20s social justice and activist oriented companies like TESA and games like Bloc-by-Bloc (which simulates anarchist urban insurgency) or Spirit Island (which reverses the colonial narrative of Settlers of Catan and sees players act cooperatively as Indigenous people working with powerful spirits to clear an island of settlers) were common in North Atlantic activist circles (Fair 2022). At the same time LARPing (Live Action Role-Playing) grew increasingly popular as a means to both have fun and think anew about social justice topics (Torben 2020). We are currently amidst a renaissance of independent game design, partly enabled by digital platforms for playing and sharing games. Independent designers self-publish print-at-home games that profoundly challenge the competitive, individualist, accumulative and heroic idiom that we associate with conventional board games. Their games focus instead on (anti-)colonialism and Global South perspectives on disability, on queerness, and that advance with feminist principles (Fair 2022; Mukherjee and Hammar 2018; Ross n.d.).

Board games appeal to advocates and allies of movements for radical social change for a number of reasons. Successful games are easy to learn, quick to play and, importantly, fun. They promise to convey an underlying message in an attractive and charismatic form. The turn towards board games was motivated in part by the concern of movement organizers for the education of young people, who typically enjoy and learn through games. Further, as game theorist Ian Bogost (2010) suggests, games teach not only through their particular manifest narratives and self-evident design features, but through their “procedural rhetoric”: the way the playing of the game itself, and the strategic thinking it demands of players, implicitly teaches players something relevant about their social world. Particular games are, in some sense, always taking place within bigger social, political and economic “games,” and often it is the broader, unacknowledged “game” that is the real focus of the players attention (Boluk and LeMieux 2017).

Importantly, on a deeper level, games offer their players access to a primordial human passion for seemingly purposeless play, something that pivotal game theorist Johannes Huizinga (1971) sees at the core of society. The ability to draw what he calls a “magic circle” around a group of consenting players and define a mutually pleasurable parallel world may be older than language and is not only evidenced in humans but many other species as well. Education theorists have noted that games offer one of the most effective venues for learning, and indeed structured play is arguably the most important method by which humans learn from infancy onward (Crocco 2011). It should then come as no surprise those involved in struggles for radical social change should gravitate to what might well be considered the first among social media.

Indeed, the first generation of social media as well as its later forms drew implicitly and explicitly from games and gaming (Hristova and Lieberoth 2021). Notoriously, Facebook was first developed in a college dorm room as a game through which male students could rank the attractiveness of their female counterparts. Twitter’s development drew on insights from game design and the company hired game designers to help make their platform more attractive. Instagram continues to advertise itself as a “fun” game-like environment for online play, even though it has become seriously personally and professionally consequential to hundreds of millions of users and the lucrative platform for the careers of “influencers.” And TikTok, most explicitly, fosters a game-like experience of back and forth performative play, a kind of participatory “infinite game,” to draw on James Carse’s (1986) terminology: a game where the primary objective is to keep playing.

Dangerous Games in the reactionary cultural politics of late capitalismIt is not surprising that both establishment-oriented and reactionary forces have gravitated towards the power of games. Over the last four decades, capitalism has become an increasingly gamified force (deWinter, Kocurek, and Nichols 2014; Jagoda 2013; Tulloch and Randell-Moon 2018).

On the one hand, we have seen the explosion of gaming industries, notably the video game industry, which today rivals other major entertainment media like film, television, sports and gambling (Dyer-Witheford and De Peuter 2009). The board game industry is nowhere nearly so large or concentrated, in part because board games require vastly fewer resources to create and bring to market, encouraging more diversification. But it nonetheless cannot be easily separated from the profit-driven pressures that shape the broader games industry of which it is a part.

On the other hand, as digital gaming advances and handheld digital devices become ever more ubiquitous, all manner of corporations and social institutions have gravitated towards using the protocols, methods and idioms of gaming to stimulate particular behaviors and dispositions in consumers, usually in the name of making money (Hon 2022). This builds on a long history of companies advertising their products in games or sponsoring the creation and marketing of games as a means to attract consumers (Terlutter and Capella 2013). But something today is different. The handheld devices that are increasingly ubiquitous, as well as the apps created for them were inspired by a previous generation of gambling machines (Schüll 2014). Based on careful study of neurosciences and usage patterns, these machines aim, among other things, to encourage dependency and sustained focus among users (Zuboff 2019).

But we must also broaden the scope when we think about games, gamification and digital capitalism. As we have argued elsewhere (Haiven, Kingmsith, and Komporozos-Athanasiou 2022), capitalism feels, to many if not most working- and middle-class people, as if it were an unwinnable, compulsory game. The post-war compromise of Fordism suggested that those (in the so-called First World) who obeyed legal and social conventions and “played by the rules” could be relatively certain of some meaningful if modest share of growing prosperity, at least for white male workers. In the neoliberal period, however, social and economic risks were shifted onto consumers and workers, sold as the freedom to compete in an all-powerful market presented as a “level playing field” (Littler 2017). Far from rewarding hard work, cunning and determination, most workers’ real wages declined during this period, as economic life increasingly felt like a rigged game.

Unfortunately, given the state of media and educational institutions, a large number of people affected by these conditions have been deprived of, or are unconvinced by, critical analyses of the political and economic source of these frustrations. Because of this, many were and are seduced by reactionary narratives that insisted the unfairness of the situation was due to specific groups cheating or rigging the game (Hochschild 2016). The far right has made and continues to make considerable gains in the public imaginary by fostering narratives that frame “special interest groups” as sabotaging the field of fair play. In the United States, accusations of welfare fraud, the misappropriation of state assistance, the cynical manipulation of “affirmative action” policies, the cheating of the criminal justice system and the abuse of guilt-inducing social justice rhetoric have renovated anti-Black racism with murderous effect (HoSang and Lowndes 2019). Fears that millions of unregistered migrants are cheating what many erroneously imagine to be a “fair” immigration system have been manipulated with devastating efficacy. Avowed white supremacists fearing a “great replacement” but also many people of non-white migrant backgrounds, have come to resent those assumed to have “cheated” in the game they themselves won by hard work and sacrifice (Brass 2021). Such fears also fuel a resurgence of anti-Semitic conspiracy theories that present Jews as sadistic secret game-masters, pulling the levers of an infernal machine intended to both seduce and cheat honest gentiles (Wu Ming 1 2021).

Within this context, the right-wing and reactionary turn to games and gaming is hardly surprising. Gaming subcultures had long been hostile to women, but this exploded onto the public stage in 2014 with the infamous #GamerGate phenomenon, which saw legions of gaming fans, almost all of whom identified as men, orchestrate a decentralized but highly effective campaign of life-threatening harassment of women and feminist game designers and critics (Massanari 2017). Recognizing the demographic significance of gamers as a constituent base and admiring their vitriol, far-right strategist Steven Bannon pivoted towards courting these communities through the now-infamous Breitbart news enterprise and later mobilized them in the successful presidential campaign of Donald J. Trump (Warzel 2019).

Both these far-right initiatives relied upon game-themed tropes that insisted that good, hard-working, honest people had been cheated out of their right to participate in the economic game of neoliberal capitalism. The implicit feeling was not that they had been derived of their inherent entitlements, but of their right to compete, fairly, for success. They also invited far-right activists to mobilize in game-like formations, including crowd-sourced social media mobbings reminiscent of #GamerGate, where targets were identified from the bully pulpit to be harassed. Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign can fruitfully be seen as a kind of spectacular (and spectacularly dangerous) game. The crass and bombastic candidate constantly “broke the rules” of acceptable politics to court both, on the one hand, far-right stalwarts who agreed with his racist ideology and, on the other, unaffiliated but disaffected voters who generally felt cheated. For both admirers and critics, consuming and reacting to Trump’s atrocious virtuosity had a game-like quality, a vivified, high-stakes version of the “reality TV” game-show The Apprentice that had returned the iconic player to the limelight.

Meanwhile, the same “whitelash” culture of resentment was giving rise to previously unseen monsters. As early as 2017, in the netherregions of the dark-web, a mysterious character who named himself “Q” began to post cryptic messages about current events, building a small subcultural following that quickly went viral as Q claimed to be an insider in the Trump administration, part of a top-secret taskforce helping the then-President uncover and wage war on a secret conspiracy (Rothschild 2022). In this conspiracy, senior members of the Democratic Party, along with seemingly random A-list celebrities, corporate power-holders and other people and institutions were part of a global cabal dedicated to kidnapping, abusing, murdering and harvesting the vital fluids of children.

During the pandemic the Q-anon conspiracy fantasy grew quickly in popularity, perhaps thanks to the support of Trump insiders and sympathizers who saw it as a vehicle to rally support to the embattled President. As it moved from the subcultural margins to the mainstream, numerous game designers noted the unsettling game-like qualities of the phenomenon. Q’s dark-web messages to his followers were profoundly cryptic and suggestive, encouraging online communities to form dedicated to a kind of participatory hermeneutics. A group of derivative social media and video platform celebrities emerged as trusted interpreters. Some crusading fans would take it upon themselves to gather at sites they imagined were soon to be crucial locations in the great war on the pedophile conspiracy, as prophesied by Q. Game designer Reed Berkowitz (2020), who specializes in the design of augmented reality games, presented the term “guided apophenia” to describe how the protagonists behind Q-Anon were taking advantage of the human capacity to see or imagine patterns, even where none exist. For Berkowitz and others, Q-Anon was nothing so much as a massive, largely decentralized participatory online game, with very dangerous consequences (Davies 2022).

Tensions came to a head on January 6, 2020, when supporters of the unseated President stormed the US Capitol building, leading to the deaths of six people and one of the most infamous cases of civil insurgency in living memory. News reports during and after these grave events made much of the strange costumes and playful demeanor of many of the “insurgents,” as well as the prevalence of self-identified Q followers who believed the final confrontation with the evil cabal was finally at hand. In the media and congressional inquiries that followed, much of the discussion focused on to what extent the mob had been orchestrated and encouraged by the Trump administration campaign, and the extent of the involvement of organized white supremacists and other extreme right groups.

What has, however, fallen by the wayside, is a sociological investigation of the playful motivations and subjectivities of not only the particular participants, but the many supporters of the events. To be curious about the ways that the events of January 6 represented, for many, a game gone horribly wrong is not to diminish it as a failed far-right putsch, but to recognize the way that it was also symptomatic of the cultural politics of gamified neoliberal capitalism.

An age of reenchanted cultural politicsOur argument is that such gamified cultural politics has been not only indispensable to the rise and spread of reactionary conspiracism, but also part of a wider set of attempts to re-enchant the world. Adorno and Horkheimer (1997) famously built on Max Weber’s (2001) theory to argue that, while technocratic, scientific and actuarial logics of protestant-led European capitalism had stripped the world of its enchantments, the instrumentalization of life had displaced the need for enchantment to a new level. While a number of theorists have challenged this view (McCarraher 2019; Josephson-Storm 2017), we still find much merit in such a description, especially as it helps us reflect on the cultural politics of the neoliberal age where each individual is intended to adopt the dispositions of the financier, craftily transmuting all aspects of life (relationships, housing, pastimes, talents) into assets to be leveraged under the sign of the indifferent market (Haiven 2014). The neoliberal dream of pursuing peace, prosperity and freedom through universal competition and a market-driven society turned out to be just as enchanted a worldview as any other. Beyond the pretensions of the self-deluding middle classes (who believe that they, too, can be rich, if only they play their cards right) the imposition of an austere market logic affects nearly every person, normalized through “high-functioning” anxieties that internalize the dominant capitalist narrative of productivity above all else (Kingsmith 2022). Even for the poor and economically marginalized, the figure of the hustling petty criminal, or the rags-to-riches reality TV starlet, offer a model for how to transmute life into a series of market plays and puts for “players” who can “game the system.” The fact that, today, a huge proportion of adolescents aspire to be influencers via monetized and gamified social media platforms indicates how deeply a game-like market logic has saturated social life.

It is amidst widespread disenchantment that we contextualize the game-like turn described above and, in particular, the appeal of what at first glance seem like absurd conspiracy fantasies. Part of this has something to do with the narrative tropes and simplified feelings of ideological closure propounded in popular cultural texts (notably Hollywood films), with their stark, manichean depictions of good and evil. The plot line that sees a small band of misfits coming together against insurmountable odds and the skepticism of their fearful compatriots to bring down a cruel regime is now extremely common in film, television and video games, including in children’s content. In a disenchanting world where one’s sense of purpose is reduced to participating in what feels like a rigged economic game, it should not be particularly surprising that individuals take up these tropes to craft immersive and enchanting parallel worlds. When economic reality becomes a near-impossible yet compulsory game, many people escape into or create games that feel empowering, prosocial and at least theoretically winnable.

Here, the Q-Anon participatory fantasy is only the most stark example, relatively easy to recognize because it sits so squarely on the absurd far-right of the political spectrum. Yet those who preen themselves as centrists are no less culpable for creating participatory fantasies. While Trump’s policies were atrocious, and while the fascistic political culture he presided over are extremely dangerous, the “centrist” loathing of him that reduced the problems of late capitalism to his particular evil exemplified a kind of enchanted and enchanting narrative just the same (Bratich 2020). Anti-Trump online politics even included forms of politicized witchcraft (Fine 2021), but this is only the most extreme example of the turn towards game-like re-enchantment.

Meanwhile, we should not ignore the many ways that those on the radical left, those who advocate for radical social change, are also attracted by a cultural politics of re-enchantment. For example, in recent years many young people on the Left have turned towards astrology and divination, including horoscopes, tarot cards and more (Komprozos-Athanasiou 2021; Sparkly Kat 2021). This is part of a wider trend towards a cultural politics that centers healing and “the work” of inward-facing subjectivity transformation, based on the recognition that systems of oppression work, in part, on the level of the subject. It is also based on a growing skepticism of the white-supremacist mobilization of tropes of objectivity and rationality. Critics may be tempted to bemoan the “weird” turn in the Left as a departure from not only reason but also the working class, seeing it as purely a self-indulgent middle-class narcissism. However, we prefer to read it sociologically as emerging from, and as a (dubiously effective) response to, the same political economic circumstances that give rise to the “cosmic right” (Milburn 2020; O’Donovan 2021).

Forms of reenchantment present themselves as resistance, even though in many cases they help perpetuate, reinforce or defend dominant structures and systems of power. We have opted for a language of enchantment, rather than simply fantasy, to signal the way that this tendency is not simply a completely fictitious parallel world but a set of dispositions that incorporate and offer interpretive frames for real-world events to animate a wide diversity of groups and orientations across the political spectrum in ways that rely not simply on the individual fabrication of a “common sense” imaginary, but operate through participatory social frameworks (Haiven and Khasnabish 2014).

There are many critics who, in the face of reenchanting politics, call for a return to a civics of disenchantment. Across the political spectrum we can hear clarions to return to Enlightenment principles that encourage the disinterested adjudication of evidence over fantasy. Stephen Pinker’s (2018) Enlightenment Now is only the starkest of these arguments. More generally, the rise of conspiracy theories and post-truth politics has seen a wide variety of commentators raise the tattered banner of reason against the hydra of reenchantment. Yet as Marcus Gilroy-Ware (2020) argues, such efforts come after years of conspicuous mistruth and fabrication by governments (around, for example, the War on Terror) and the everyday cynical manipulation of truth and perception by the marketing and public relations industry.

In this context, calls to “return to reason” are not only ineffective, they are themselves another example of a game of neoliberal reenchantment: performative speech acts that serve to align the author and his (for it is almost always a man) readers as self-ennobling reasonable subjects, beset on “all sides” by unreasonable, monstrous zealots. In other words, from one angle the advocates of disenchantment invite their audience into a kind of heroic narrative game every bit as enchanting as the game-like enchantments they decry.

Clue-Anon and the promise of enchanted inquiryWhat, then, are critical scholars, working in solidarity with radical movements, to do in such a material context? If even calls to “return to reason” are themselves a kind of re-enchanting game, where do those of us stand who are reproduced by and who are tasked with reproducing the university, that bastion of disenchantment? We have no clear answers, but we have experiments, and these experiments try to inhabit and leverage, rather than condemn and dismiss, the urge towards reenchantment.

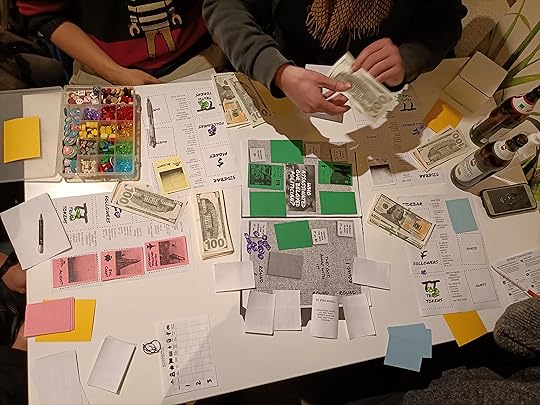

In 2020 our research team began to experiment with creating a board game intended to harness the power of participatory reenchantment. It was motivated in part by testimony from our students that revealed many of them feared visiting their families at holidays to find their loved-ones in the grips of powerful and seemingly unshakable conspiracy fantasies. Several of these students reported that board games offered a collective pastime that avoided inflammatory conversations. Based on these reports, and on our ongoing research, we began to develop a game (designed by Max Haiven and refined collectively with Aris Komporozos-Athanasiou and A.T. Kingsmith) that, after several iterations finally arrived at the name CLUE-ANON.

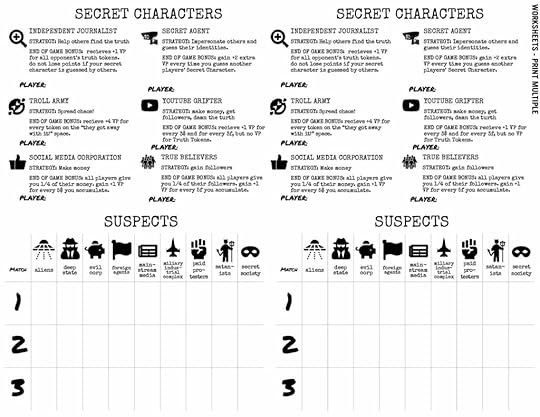

This four-player competitive game is intended to take 90 minutes and is played over three rounds. In each round, the players seek to deduce the identity of three hidden “real conspirators” from a set of nine possible suspects. To do so, they pay in-game resources (money and followers) to look at the remaining six suspects. However, to gain sufficient money and followers, and to fool others, players must prematurely declare their conspiracy theory, well before the evidence warrants it. At first glance, it seems that the objective of the game is to correctly guess the “real” conspirators. However, in a twist, each player is assigned a secret character with a unique motivation. These characters have been drawn from the mediasphere that surround contemporary gamified, digitally-driven conspiracism. While the Independent Journalist gains extra points if their opponents also learn the real conspiracy, the Troll Army gains extra points if they can lead their opponents to guess incorrectly. The Social Media Corporation wins if they accumulate a lot of money, while the YouTube Grifter seeks to accumulate money and followers, the truth be damned.

What results is a fast-paced, somewhat chaotic game of deduction, bluffing and role-playing. In the process of play, the players learn that, in the conspiracy game, the truth is rarely anyone’s first objective. Role-playing characters with different but obscured motivations encourages a creative estrangement from one’s own position. The game is designed to be fun and easy to learn. The conspiracy theories, characters and scenarios in the game are comical, but based on real-world examples (who created the SARS-COV2 virus? Who faked the moon landing?), opening the doorway after the game for stimulating conversation. The experience generated by the game is non-didactic, in the sense that it does not explicitly attempt to teach a message but, rather, to create a space for critical conversation. Yet through the playing of the game, players come to understand that conspiracy theorizing is a fun, prosocial activity, and that one can easily become enchanted with the creative inventiveness of shared, competitive storytelling.

The game has now been played by hundreds of people, including groups at the Athens School of Fine Arts, the Singapore Civil Service College, University College London’s Institute of Advanced Studies, the ephemera journal’s “Games, Inc.” conference and the Copenhagen IT University’s Centre for Digital Play. Many players and designers find the game overly complex: it’s hard to strategize when there are so many motivations, elements and narratives in play; that’s quite the point, we reply.

Our hope is that the game can provide an important tool for educators and activists to catalyze conversations not only about the dangers and seductions of conspiracism, but its lures and emancipatory possibilities too. We see it as the first step towards a methodological orientation we have speculatively named enchanted inquiry, for which we would like to set out some hallmarks.

First, enchanted inquiry does not primarily seek to debunk, disenchant or dispel misinformation. Rather, it begins from the premise that globalizing neoliberal capitalism gives rise to the urge to reenchant the world. Without letting go of a sanguine assessment of the profound dangers such tactics of reenchantment might awaken or exacerbate, enchanted inquiry begins with the question: how might this propensity be redirected or channeled towards more critical, illuminating and generative ends? It aims, in other words, to demonstrate that we are always in the process of reenchanting the disenchanted world and to make this process more democratic, egalitarian, responsible, care-full and non-coercive.

Second, in this regard, enchanted inquiry draws on and helps develop the scholarly dispositions encouraged by Max Haiven and Alex Khasnabish in their 2014 book The Radical Imagination: Social Movement Research in the Age of Austerity. There, they argue it is not sufficient for researchers simply to observe and report on social movements in the name of valourizing them in academic contexts (a strategy they call invocation), nor to simply collapse themselves into social movements in the name of solidarity (a strategy they call avocation). Rather, scholars can adopt a strategy of convocation, “calling together” diverse social movement actors to deepen their conceptual, theoretical and political understandings and practices–the radical imagination–through facilitated discussion, debate and deliberation. Here, the scholar-activists recognize themselves not only as the outside expert or the embedded participant but (also) a third thing: a facilitator of the radical imagination, that tectonic force at the core of all societies and all subjects that arises to challenge the given reality in the name of manifold possibilities for changing society (Castoriadis 1997). Enchanted inquiry is one method (or perhaps an orientation that might inform many methods) for embracing this strategy of convocation with a particular focus on games, mystery, magic, myth and speculative imagination.

Finally, enchanted inquiry is fun, in the nuanced, plural and collaborative sense. Enchanted inquiry draws on theories of play and games in order to create seductive circumstances where participants can learn about the world together and change their minds in non-trivial ways. Fun here does not mean simple, easy or uncritical. The ambivalence of the word speaks to the challenge of making activities that are both challenging and rewarding, prosocial and deeply reflexive, enjoyable and disruptive. Enchanted inquiry aims to mobilize fun as a means to catalyze the radical imagination.

ReferencesAdorno, Theodor W., and Horkheimer, Max. 1997. Dialectic of Enlightenment. London: Verso.

Berkowitz, Reed. 2020. “A Game Designer’s Analysis of QAnon.” The CuriouserInstitute, September. https://medium.com/curiouserinstitute....

Birchall, Clare. 2001. “Conspiracy Theories and Academic Discourses: The Necessary Possibility of Popular (over)Interpretation.” Continuum 15 (1): 67–76.

Bogost, Ian. 2010. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Boluk, Stephanie, and Patrick LeMieux. 2017. Metagaming: Playing, Competing, Spectating, Cheating, Trading, Making, and Breaking Videogames. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Booth, Paul. 2015. Game Play: Paratextuality in Contemporary Board Games. New York and London: Bloomsbury.

Brass, Tom. 2021. “Great Replacement, or Reaping the Capitalist Whirlwind (via Populism/Nationalism).” In Marxism Missing, Missing Marxism: From Marxism to Identity Politics and Beyond, 230–57. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Bratich, Jack. 2020. “Civil Society Must Be Defended: Misinformation, Moral Panics, and Wars of Restoration.” Communication, Culture and Critique 13 (3): 311–32.

Carse, James P. 1986. Finite and Infinite Games: A Vision of Life as Play and Possibility. New York: Free Press.

Castoriadis, Cornelius. 1997. The Castoriadis Reader. Translated by David Ames Curtis. Oxford and Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Crocco, Francesco. 2011. “Critical Gaming Pedagogy.” The Radical Teacher, no. 91 (September): 26–41.

Davies, Hugh. 2022. “The Gamification of Conspiracy: QAnon as Alternate Reality Game.” Acta Ludologica 5 (1): 60–79.

deWinter, Jennifer, Carly A. Kocurek, and Randall Nichols. 2014. “Taylorism 2.0: Gamification, Scientific Management and the Capitalist Appropriation of Play.” Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds 6 (2): 109–27.

Donovan, Tristan. 2017. It’s All a Game: The History of Board Games from Monopoly to Settlers of Catan. New York: St. Martin´s Press.

Dyer-Witheford, Nick, and Greig De Peuter. 2009. Games of Empire: Global Capitalism and Video Games. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Fair, Hannah. 2022. “Playing with the Anthropocene: Board Game Imaginaries of Islands, Nature, and Empire.” Island Studies Journal 17 (1): 85–101.