Max Haiven's Blog, page 3

August 22, 2024

Billionaires and Guillotines

I made a fun and hopefully insightful game about some of the contradictions of capitalism.

This fall, I’ll be working with my publisher Pluto Books to run a crowdfunding campaign to manufacture it.

But meanwhile, this summer, I’ve released a free print-at-home version you can play with your friends and family.

I’d very much appreciate it if you played it and sent me feedback!

Billionaires and Guillotines is a raucous and moderately challenging competitive game for 2-5 players. New players can learn in under an hour. Experienced players can finish a game in less than 30-minutes.

You take on the roles of billionaires, competing to win by claiming

PRIZES before a

REVOLUTION happens and every billionaire loses (almost).

By using cards to

BID at five different

MARKETS, the billionaires can try and grab the five

PRIZEs they need.

But hidden in the deck are

CRISIS cards that penalize players and unleash

REBELS.

Players use

BRIBES to change

GOVERNMENT POLICY to make them richer, or to have the government

AUDIT their opponent.

When the going gets tough, the billionaires can trigger a

PANIC! phase, where they can cooperate to try and distract the public or put down the rebellion before the

GUILLOTINE gets wheeled out and all the billionaires lose (more than their assets).

As the players gain experience, each billionaire gets assigned a secret

ROLE that gives them special powers.

To download the printable game and the manual, please visit https://ourmove.itch.io/billionaires-and-guillotines

If you do play Billionaires and Guillotines, could you send me some feedback? You could…

Write me an email, send me a voice note or record a video.Please tell me how long it took you to learn and play the game and what happened (“it took us about 20-minutes to get the hang of the game, but then things started moving quickly. For most of the game, Karl was in the lead, but near the end Rosa used her gangster power to steal his private island and it looked like she would win. But then Che triggered the revolution and Slavoj won as the celebrity at 48mins in.”)Was the game fun? Was it fun for everyone? If not, why?What was frustrating or confusing?Any suggestions, either for changes to the game or ways we can publicize it?Billionaires and Guillotines will be the first game either I or Pluto have published, so your feedback is especially welcome! If it’s successful, we’re looking forward to collaborating on a new initiative, Pluto Games, which will combine that press’s 50+ year history of publishing radical books with the rising popularity of board, card and other analog games.

A huge thanks not only to the fine folks at Pluto, but also to Stella Lawson and Sam Cousin who worked as graduate assistants to me over the past two years and did invaluable and fascinating research on the politics and political economy of games that helped get this game this far.

The post Billionaires and Guillotines appeared first on Max Haiven.

March 3, 2024

Mayday Movement (anti-)Academy, Berlin April 29 – May 3, 2024

Sense & Solidarity (a project I run with Sarah Stein Lubrano) is pleased to announce the Mayday Movement (anti-)Academy, a four-day workshop for community organizers, radical artists, activists, educators and other practitioners of the radical imagination to learn techniques and theories for changing hearts and minds.

We’re looking to grapple with some of the toughest challenges in left organizing and activism using our signature mix of psychological insight, radical imagination, and strategy.

To learn more and apply, click hereWe’re providing a space for new and established educators, activists, artists, thinkers and organizers to assemble, share resources, and inquire into topics including (but not limited to):

How can use psychological insights to mobilize others, keep up momentum, and build solidarity?How can we see (the good kind of) emancipatory social change within our lifetimes?How can we create arguments and infrastructures to change hearts and minds and overcome fatalism, fear and factionalism?How can we strategize to make the best use of our very limited resources and energies?How can we cultivate the radical imagination in ourselves and those around us?How can we avoid burning out?To do so, we at Sense & Solidarity draw on and combine:

The intergenerational wisdom and best-practices of social movementsCritical theories of ideology that analyze the way power shapes our feelings and imaginationsRecent insights from the cognitive sciences into things like unconscious patterns, cognitive dissonance, the impact of social bonds, social media and moreTogether, we’ll learn how to:

Understand what does and does not change people’s minds (hint: actions over words)Be strategic and selective about whose hearts and minds we want to change (it can’t be everyone)Recognize and work with common fears, anxieties, hesitations and antagonism we might meet in our campaignsThink through if, how and when activism can provide a warm, empowering, welcoming community (and when not to!)Be tactical about disrupting and dividing our opponents, and learn to recognize when they’re doing the same.And much more…To learn more and apply, click hereThe post Mayday Movement (anti-)Academy, Berlin April 29 – May 3, 2024 appeared first on Max Haiven.

February 26, 2024

Exploits of Play: A Podcast about Games and Capitalism

It has been a treat to work with the wonderful Weird Economies project on a new 10-episode podcast, “The Exploits of Play,” which will be launched on 26 February 2024 with new episodes released weekly until May.

This series explores how games and gamification have moved from the margin to the centre of the weird capitalist economy.

It jumps beyond the commonplace and largely uninteresting observation that video games have become a major entertainment industry. It also takes for granted that tech and speculative capital have invested heavily in technologies of gamification as a means to gain and hook new users. Instead, it looks to the deeper sociological roots and effects of these trends and the way they are reshaping many spheres of life, from economics to sexuality. And it meditates on what this means for resistance… the good, the bad and the ugly.

Join us for episodes on the gamification of love, on the playfulness of conspiracism, on the myth of the “cheating other,” on the tyrannical rise and rule of game theory, on the appeal of the Hunger Games… and much more!

The podcast is based on research I’m doing currently for my next book The Player and the Played: Gamification, Financialization and (anti-)Fascism.

Ep01 – Conspiracy Plays – Hugh Davies on the temptations of alternate reality

Ep02 – The Game at War with the World – S. M. Amadae on the powers behind the prisoner’s dilemma

Ep03 – All Against All – Tom Boland on our modern gladiators and the real world hunger games

Ep04 – Frontiers of Play – Mary Flanagan on games, colonialism, and the playful imagination

Ep05 – The Cheating Other – Gargi Bhattacharyya on how racial capitalism scams us twice

Ep06 – Gaming Authority – Thiago Falcẫo on exploitation and far-right politics in the games industry

Ep07 – “It Is What It Is” – Sophie Lewis on Love Island, game shows, and the banality of capitalist eros

Ep08 – Toyed With – Alfie Brown on the gamification of affect and love’s digital futures

Ep09 – The Singularity Bluff – Christian Nagler on Silicon Valley’s dangerous dreams of cheating death

Ep10 – Our Moves and Movements – Jay Jordan and Isa Fremeaux on the playfully subverting capitalism

The post Exploits of Play: A Podcast about Games and Capitalism appeared first on Max Haiven.

February 19, 2024

Color, corporations and other fictions

An edited version of this essay appeared in a catalogue published to accompany Danish artist Hannibal Andersen’s 2022 exhibition The Abstract Expression of Privatization. In that work, an installation and a large mural explored corporate claims to the ownership of certain colours.

Hannibal Andersen, from The Abstract Expression of Privatization, 2022. Installation view, Kunsthal Charlottenborg.Color, corporations and other fictions

Hannibal Andersen, from The Abstract Expression of Privatization, 2022. Installation view, Kunsthal Charlottenborg.Color, corporations and other fictionsMax Haiven

The fact that, today, a corporation – an artificial legal entity intended solely to make money – could declare ownership over a color represents in many ways both the power and the pathology of a system built on the notion of private property, which is to say capitalism. Colors and corporations are both social constructs that become real to the extent that both are enforced through the immaterial infrastructures of convention and law.

As natural as colors seem to us, they are in fact socially constructed categories, unchosen agreements we have entered into that allow us to communicate the experience of reflected waves of light vibrating at a specified frequency hitting our retinas. While the process by which waves of light are sensed by the eye are relatively common to most humans (although many are “colorblind” and neurodivergence is much more common than we tend to imagine), the meaning we give to that sensation is highly culturally variable.

It’s not simply the case that death and mourning is signified by black in some cultures and yellow in others. Across a range of civilizations, the very categories of the color spectrum are organized differently, outside of their particular symbolism.[1] In Japanese, for example, there was not a clear, widely used distinction between blue and green until people there began to communicate extensively with Portuguese traders, in whose language each color was a distinct concept. In Russian and Greek, light blue and dark blue are represented by distinct words and concepts, whereas in English (as this sentence itself demonstrates) the two are the same color that needs to be qualified by an adjective. Some languages and thought-worlds have no distinct words for colors at all and in others there is no abstract idea of color, as distinct and separable from texture, brightness, taste or other sensations.

In seeking to use law (state power) to enforce the exclusive use of a certain range of frequencies, notions of property deconstruct themselves, revealing their dependency on profound contradictions, contradictions that can only be sustained through real or symbolic violence, or the threat of it.

In recent years, advanced technologies have allowed us to specify extremely precise fragments of the color spectrum. The Pantone Matching System is perhaps the most famous, and has had significant consequences for how we perceive the world.[2] It has permitted corporations to make the legal case that they should be granted exclusive use, within specific commercial contexts, of specific segments of the spectrum of visible light.[3] In seeking to use law (state power) to enforce the exclusive use of a certain range of frequencies, notions of property deconstruct themselves, revealing their dependency on profound contradictions, contradictions that can only be sustained through real or symbolic violence, or the threat of it.

To many of our forebears, the idea that one could exclusively possess a color would be tantamount to declaring that an imaginary person owned part of the sun, or that a fictional character owned the sensation of longing. A corporation is, after all, just as artificial as colors are. Emerging in the 1600s, the corporation is a kind of Frankenstein’s monster of capitalism, an artificial lifeform given the breath of life by law and its animating electrical current by an initial investment from those who become its shareholders.[4] The hint is in the name: The corporation assembles many investors’ interests into one body, or corpus. These people buy a share of the enterprise’s profits, but are not liable for the company’s failure. The corporation was established particularly to facilitate expensive and risky oceanic trading voyages, where significant capital was needed up front to outfit the ship and purchase goods for sale and where the potential returns on the investment, while lucrative, were both uncertain and years away.[5] The corporation thus became instrumental to colonialism. The Dutch East India Companies, the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Virginia Company were all instrumental in developing privatized regimes of domination and accumulation around the world. Several such corporations governed the lives and deaths of tens of millions of people. The British East India Company nearly held all of South Asia under martial law for centuries, transforming the territory and its people into a giant facility for the extraction of wealth and exploitation of labor, policed by a completely impune private army or enforced by local elites or warlords.[6]

These early corporations operated under monopolies granted by the sovereigns of their respective empires, but as capitalist modernity progressed (if it can be called progression), corporations became more common and their agents and beneficiaries had their rights enshrined in law. It was long the case that corporations were treated as legal persons, capable of signing and enforcing contracts (that quintessential technology of capitalism), and this was enshrined in US law in 1881.[7] It was recently and disastrously confirmed in the notorious Citizens United case, which permits corporations to make massive donations to influence the outcome of the democratic elections and processes in the name of defending their freedom of speech as legal persons.[8] Similar laws exist around the world, spread either through colonialism or in the name of corporate-led globalization and the harmonization of law to allegedly encourage global trade.

Of course, a corporation is not a person and, as such, cannot be punished (except through fines), cannot feel shame, cannot be executed or imprisoned for its crimes and has no conscience. The people who work for or own it can, but the necromancy of the corporation is that an executive that suddenly develops moral scruples about its behavior can and usually will be replaced as soon as those get in the way of their fiduciary responsibility to shareholders to deliver financial returns.[9] And “shareholder activism” only very rarely implies a coordinated effort to make a corporation act in accordance with social or ecological care; quite the opposite: it refers to the way shareholders try to take control or influence corporate management to put their financial gains first. Sure: shareholders are welcome to “vote with their wallet” and divest from companies that do harm. But most shareholders are not upstanding individuals but, rather, other corporations, including pension funds, asset management funds, private equity firms and institutional investors, who have their own shareholders to please. Even in the rare cases where banks, governments or voluntary regulatory bodies have been able to impose benchmarks for “ethical investment,” these typically depend on measurements and enforcement mechanisms that have proven easy for corporations to circumvent by employing legions of lawyers and “compliance officers”.

The result has been disastrous. Those who fear that artificial intelligence will take control of society and the economy misrecognize the threat, for it has already occurred. Corporations are, essentially, artificially intelligent, autonomous organisms of the market, and they have unrivalled and as yet unstoppable control over the world’s economy.

The result has been disastrous. Those who fear that artificial intelligence will take control of society and the economy misrecognize the threat, for it has already occurred. Corporations are, essentially, artificially intelligent, autonomous organisms of the market, and they have unrivalled and as yet unstoppable control over the world’s economy. As governments around the world must increasingly compete to attract and retain corporations in the name of creating or preserving jobs and investment, any hope of meaningfully regulating corporations dwindles. The political spectrum seems to increasingly be limited to, on the left hand, political parties that want to use whatever vestigial powers the state retains to try desperately to protect some elements of society from all-powerful corporations and, on the right, those that see corporate power as natural, normal and inevitable, or try and wed it to some kind of local ethnonationalism, seeing the state and corporations as natural partners in the global war of all against all. Corporate donations to political parties, acknowledged or secret, are commonplace and the influence of corporate-funded foundations or think tanks over policy is profound. This is to say nothing of the close relationship between corporate management and political elites, which ranges from cronyistic to corrupt.

Color and the corporation, then, reflect one another’s fictiveness. Both are social constructs, held in place by conventions of the imagination. But color is, of course, far less dangerous, in most circumstances.

But not all.

The corporation emerged as a vehicle for capitalist empires to extract wealth and subordinate labor around the world. The history of this vehicle is deeply knotted up with the history of race. Race is itself a pernicious fiction, a bogus method for categorizing human beings whose origins go back to the 17th century but which took on modern, allegedly “scientific” meaning in the 18th and 19th centuries.[10] The ideology of race insists that phenotypical characteristics of a person (notably skin color, body type, facial features and other outwardly visible characteristics) not only reveal differences, but that these differences have a significant bearing on a person’s intellectual or moral disposition or capacities. The modern, scientific ideology of race typically insists that these phenotypical markers are inherited from ancestors who evolved under different circumstances and therefore pass down specific persistent behavioral traits. No such traits have been found to be linked to phenotype, of course. While not all forms of racism are obsessed with the phenotype of skin color, many are and have been. Part of the racist ideology is the hallucination of a single “white” race (variously also understood to be “Caucasian” or “Aryan” due to a prejudicial and discredited theory of racial origins), a term which selectively collects people imagined to have European ancestry into a single highly dubious category, in spite of massive genetic, cultural and linguistic differences between them. The artificial ideological category of whiteness was developed to help normalize and justify the Western European project of colonialism and imperialism. Its hallucinatory form was given power and reified insofar as it could define itself against its “others,” or various non-white peoples. For example, people of diverse African origins, speaking a multitude of languages, practicing a wide variety of religions, emerging from very different cultures, were categorized as “black.” This process was fundamentally shaped by the transatlantic slave trade, of which, as we have discussed, the corporation was a crucial vehicle. Enslaved people became “black” through the racist machinations of the institution of the Euro-American slave system. And it was on the basis of the wealth that these people were made to represent, and that their unfree labor produced, that the modern world was made.

The entanglement of color, corporations and race reveal to us the terrible power of the imagination when it is put to work justifying, normalizing and enabling exploitation, oppression and injustice. It is also, as Rinaldo

Walcott makes clear, at the core of our concepts of property. While private property relations have existed in many societies, a form of global capitalism wrought out of the history of slavery is one in which they are elevated to an all-consuming ideal.[11] It is a system that emerged, materially and in terms of its core institutions and ideas, from the scene of the plantation, where enslaved human beings were transformed into the property of their owners and also compelled to make those owners more property that could be sold, including food (rice, sugar cane), commodities (indigo, tobacco) or, horrifically, more slaves (by bearing children). For Walcott and others, this is the origin of the modern property system, which also helps explain the anti-black violence inherent to modern forms of the protection of private property, notably police forces and prisons. Property is a fiction, an abstract claim to possess the real world. But like race, this fiction is made into reality through enforcement. The fiction serves to justify reigning power relations, and so has the support of dominant groups and the institutions that serve their interests.

This account of the emergence of modern property regimes adds an important anti-racist and anti-colonial dimension to the influential ideas about property from Karl Marx and Karl Polanyi. The former argued that, under capitalism, private property becomes crucial to the cycle of capital’s accumulation: The bourgeoisie maintain ownership of the means of production (factories, agricultural lands, utilities, etc), whereas the proletariat own nothing but their ability to work. Therefore, the bosses can exploit workers in factories, fields or other commercial enterprises and declare the fruits of that labor as their private property, redoubling their power and control. The communist demand for the abolition of private property referred mostly to the means of production, not to fruits of that production.[12] Meanwhile, Polanyi was to associate capitalism with the rise of three “commodity fictions,” three elemental things that became commodities (or private property) under that system that had never before been fully commodified: land, labor and money.[13]

The “fiction” of commodities and private property is connected to the fiction of race.

Walcott’s approach allows us to see how the “fiction” of commodities and private property is connected to the fiction of race. We might also point to the way that, throughout the “evolution” of the modern capitalist system, many “non-white” peoples were denied the right to own property. Indigenous people around the world were seen as subhuman simpletons incapable of responsibly “improving” the lands they occupied and therefore their property rights could be ignored. When Indigenous people were granted such rights (even though they were based on a completely alien European idea of one’s relationship to land and the world), these “rights” were largely awarded as a pretext to robbery and exploitation.[14]

In the 1800s, the efforts of the Qing imperial court to prevent British and other foreign merchants from importing the socially corrosive commodity of opium, including the seizure of the contraband, was reframed in the British parliament and press as evidence that the backwards Chinese couldn’t understand the principle of private property. This justified two highly destructive wars that created a situation in which the world’s largest economy was not only forced to continue to allow the importation of opium (at the expense of its people: some reports suggest 20% of the population became dependent on the drug) but also the massive suction of wealth from the country, including many of its most priceless cultural treasures which remain in Western collections to this day.[15]

Hannibal Andersen’s mural $!?, part of The Abstract Expression of Privatization

Hannibal Andersen’s mural $!?, part of The Abstract Expression of PrivatizationThese dense entanglements of color, property and empire help illuminate Danish artist Hannibal Andersen’s 2022 intervention in Copenhagen: a huge mural painted on the side of a prominent downtown building (that once displayed a Pepsi advertisement) depicting what appears to be a question mark merged with a dollar sign, rendered in a palette of two trademarked colors, owned by two Danish corporations. The powdery light blue “belongs” to Maersk, one of the world’s most prominent shipping and logistics firms. The rosy red is controlled by Grundfos, a world-leading producer of pumps.

Intended to provoke conversation and perhaps a legal response from the corporations in question, Andersen’s intervention aims not only to highlight the absurd fiction that a non-human entity – a corporation – can declare exclusive sovereignty over a section of the commonly visible electromagnetic spectrum. The placement of this mural in a public space where passersby were accustomed to seeing advertising also implicitly begs the question of what kind of infrastructure of power and belief need to be in place in order for us to sustain this fiction?

A casual observer, then, might glance at Andersen’s enigmatic mural and unsee the complex imaginal infrastructure on which it rests, but they could not avoid a sense of being haunted by something beyond the frame.

To ask a question about the infrastructures that sustain these corporations’ fiction of “intellectual property” is to place into critical proximity fiction and infrastructure. It’s perhaps not a coincidence that both Maersk and Grundfos are part of that invisible but essential world of processes and things that make the capitalist economy function. Maersk is not only responsible for moving goods around the world on container ships; it also operates ports, drills for deep sea oil, provides a wide range of clients logistical services and offers a wide range of affiliated horizontal and vertically integrated services. The corporation is a small but significant player in a globalized capitalist system that we depend on every day, even though most of us only rarely catch sight of Maersk’s ships, with their iconically hued hulls, or its identically colored standardized shipping containers in which everything from ramen noodles to plasma TVs to medical equipment to smuggled human beings make their way around our interconnected planet.

Likewise, besides those of us who work in industrial construction or maintenance, most of our eyes have never seen a Grundfos pump, even though it’s not unlikely that one such device is essential to the heating or cooling of the building in which we might be sitting, the water system we depend on, the power grid that electrifies our lives or the agricultural infrastructures that grow our food. In both cases, the corporation’s possessiveness over their proprietary brand color seems inversely proportional to its public visibility. For these companies that have made themselves so profitably pivotal to the logistical and infrastructural underside of today’s global capitalism, the color is itself a kind of infrastructure that signals the deep entanglement of law, belief, enforcement and sheer economic momentum that keeps the whole system running.

It is the infrastructures of the imagination that interest me here, and the way this artwork implies them. We have explored how corporations, race, color and notions of property operate as solidifications of the imagination. They are all fictions held in place and given real power by social convention, the movement of wealth, and regimes of enforcement. And yet, like the infrastructure and logistics that these two corporations represent, this vital process is largely rendered invisible. And the violence and exploitation underneath is also hidden.

As far as global corporations go, both Maersk and Grundfos don’t stand out for their evil. And yet, beyond the fact that both companies keep with the dominant capitalist paradigm and hold essential services for ransom to achieve their profit motives, more too is at stake. Maersk, like any company that operates ships and container ports and oil extraction and logistics, has rightly been targeted for doing business with regimes that abuse human rights.[16] The shipping industry, driven by and profiting from the reckless consumerism that demands goods be transported around the world, is among the world’s leading emitters of greenhouse gasses and huge cargo ships take their toll on the oceans and their life.[17] Maersk’s significant influence on Danish politics is a matter that concerns many who care for the health of that country’s democracy.[18]

At first glance, there is nothing offensive about manufacturing pumps, but when one realizes their importance to the infrastructure of oil and fossil fuel extraction, including fracking, or their usefulness in ejecting water from mining operations around the world, or their use in coal and nuclear power plants, or as part of natural gas or oil pipelines, one might think again.

A casual observer, then, might glance at Andersen’s enigmatic mural and unsee the complex imaginal infrastructure on which it rests, but they could not avoid a sense of being haunted by something beyond the frame. It is not simply the enigmatic symbol, half question mark, half dollar sign, that acts almost like a magical sigil or rune, summoning up something from the folds of our reality. It is also those colors which suggest a forgotten association. After all, if they did not have such evocative power, surely their corporate owners would never have endeavored to make them their property, at considerable expense.

Color, law, belief, race, capital fold in on themselves like origami such that even when one part is hidden inside the newly dimensional object, nonetheless they remain and are implied by the structure of the whole. Capitalism is unseeable in its totality, a sublime system in scope and magnitude. We are destined to only see fragments of it. But each fragment, like a shard of a hologram, contains a reflection of the totality.

In my book Art After Money, Money After Art: Creative Strategies Against Financialization I argued that part of art’s power in a world dominated by money is to offer us new glimpses of the capitalist paradigm of which we are all (artist and spectator, gallery and advertisement) a part. Art’s critical promise doesn’t come from its distance from capitalism but from its proximity.[19] In fact, the category of “art,” like property, like race, like the corporation, is also a fiction, held in place by belief and enforcement. What separates Andersen’s work from the Pepsi advertisement that preceded it is that the advertisement reaffirmed these fictions. It depended on and reinforced the imaginal infrastructures on which our mode of capitalism depends. Andersen’s mural does the opposite. Its charismatic enigma asks us a discomforting question.

We can only hope that Andersen is sued by Grundfos or Maersk, adding the performativity of a courtroom drama to the artistic work. Indeed, the possibility of a scandalous lawsuit is implied in the artwork’s performative breach of trademark laws. Another timeline, in which such a legal case plays out, is a virtual element in the work. But beyond risking opprobrium for targeting an artist, more is at stake that might dissuade these companies from such legal adventures. As it appears today, the work is subtly mischievous. Were its full implications to be spelled out in a court of law and in the newspapers, they might bring to the surface a number of profound questions about our world that such companies might prefer remain submerged.

[1] Bevil R. Conway and Ted Gibson, “Languages Don’t All Have the Same Number of Terms for Colors – Scientists Have a New Theory Why,” The Conversation, accessed December 10, 2022, http://theconversation.com/languages-...

[2] Kevin Yuen Kit Lo, “The Propaganda of Pantone: Colour and Subcultural Sublimation,” Grafik.Net, March 5, 2016,

https://www.lokidesign.net/en/texts/t...

[3] Charlene Elliott, “Color Codification: Law, Culture and the Hue of Communication,” Journal for Cultural Research 7, no. 3 (July 2003): 297–319, https://doi.org/10.1080/1479758032000...

[4] Joel Conrad Bakan, The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Free Press, 2005).

[5] Ian Baucom, Specters of the Atlantic: Finance Capital, Slavery, and Philosophy of History (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005).

[6] Nick Robins, The Corporation That Changed the World: How the East India Company Shaped the Modern Multinational, 2nd ed (London: Pluto Press, 2012).

[7] Adam Winkler, “‘Corporations Are People’ Is Built on an Incredible 19th-Century Lie,” The Atlantic, March 5, 2018,

https://www.theatlantic.com/business/....

[8] Kevin Musgrave, Persons of the Market: Conservatism, Corporate Personhood, and Economic Theology (East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State University Press, 2022).

[9] Max Haiven, Cultures of Financialization: Fictitious Capital in Popular Culture and Everyday Life (London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

[10] For reasons of brevity I am skimming a deep and complex field of knowledge, details of which can be found in Dr. Alana Lentin’s Understanding Race Syllabus as well as her other insightful work: https://www.alanalentin.net/2022/02/2...

[11] Rinaldo Walcott, On Property (Biblioasis, 2022).

[12] For a gloss as well as an insightful engagement with the settler colonial roots of property that Marx misses, see Robert Nichols, Theft Is Property! Dispossession and Critical Theory, Radical Americas (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020).

[13] Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation : The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time, 2nd Beacon Paperback ed.

(Boston MA: Beacon Press, 2001).

[14] See Nichols.

[15] Max Haiven, “Our Opium Wars: The Ghosts of Empire in the Prescription Opioid Nightmare,” Third Text 32, no. 5–6 (November 2, 2018): 662–69.

[16] See https://old.danwatch.dk/en/undersogel... https://wsrw.org/en/archive/4189;

https://www.barrons.com/news/maersk-t...

[17] Laleh Khalili, Sinews of War and Trade: Shipping and Capitalism in the Arabian Peninsula (London; New York: Verso, 2020).

[18] See https://www.information.dk/indland/20...

[19] Max Haiven, Art after Money, Money after Art: Creative Strategies Against Financialization (London: Pluto, 2018).

The post Color, corporations and other fictions appeared first on Max Haiven.

December 12, 2023

Help us fund WHAT DO WE WANT? A podcast about changing hearts and minds…

Hi! I hate to fundraise, but I love this project and I’d like to see it become a reality. I really think it will be useful to our struggles for collectively liberation. We’re trying to raise only about $2,000 by January, so even a small donation helps. If you don’t like Kickstarter, you could also send money via PayPal or another method.

Help us fund…

What do we want?A podcast about the gnarly, difficult, and downright awkward questions of activism, organizing and trying to change the worldA raucous but informative call-in show that’s as entertaining as it is revelatory!Learn more and donate!

Join Sarah (a political theorist of cognitive dissonance) and Max (a cultural theorist of the radical imagination) as we explore what activists, organizers and educators need to know about what changes hearts and minds (and what doesn’t)!

We’re trying to raise about $2,000 in December to help finance this important project! Please consider donating even a small amount.

It’s no secret and no joke: We need radical social change to free ourselves collectively from all types of oppression and prevent ecological collapse, ASAP. To help people focused on this challenge (you know who you are), we’re going to ask the vexing questions that are keeping activists, organizers and educators up at night like:

Is it even possible to change people’s minds about issues they care about?Are we activists actually the most annoying people on earth?Do we all secretly want a strong leader?Do I have a hope in hell of convincing my racist uncle?Can shame be useful?Is leftist infighting actually a good thing?What can we learn from cults?On each episode you’ll hear…

A social movement organizer calls in with a awkward or vexing question about a real-world problem

A social movement organizer calls in with a awkward or vexing question about a real-world problem

Max and Sarah (two friends who met in a dysfunctional commune) take sides and debate the best course of action, calling experts to help

Max and Sarah (two friends who met in a dysfunctional commune) take sides and debate the best course of action, calling experts to help

A panel of OG organizers pass judgment

A panel of OG organizers pass judgment

Learn more and donate!Why do we need it?

Learn more and donate!Why do we need it?We urgently need to convince a lot of people to join movements, campaigns, mobilizations and organizations. But are our tools for changing hearts and minds fit for purpose? Why do we always seem to hit a wall in our organizing and never convince a majority (or even a sizable minority)? Why does the right unite and the left divide? And are we all just doomed to burn out after a few years?

Frankly, a lot of our inherited and common-sense beliefs about how to change people’s hearts and minds are outdated.

What if we admitted that carefully reasoned, evidence-based arguments rarely work? What if we accepted that changing people’s hearts and minds is a process, not an event? What if we recognized how much a radical worldview is threatening to most people? Now we’re ready!

With our academic research, bitter experience and expert guests, we’re here to offer an upgrade! And we’ll do it by challenging taboos, opening up old wounds, and generally asking all the right questions.

In this podcast, we draw on…

Thoughtfully selected recent insights from the cognitive sciences about how social brains work

Thoughtfully selected recent insights from the cognitive sciences about how social brains work

Critical theories of imagination and ideology, without any of the alienating jargon!

Critical theories of imagination and ideology, without any of the alienating jargon!

Generations of wisdom from social movements around the world…and with that we’re going to make an 7-episode podcast that include:Heartbreaking and hilarious testimonials from guest activists, organizers and educatorsAccessible, witty and informative explanations of key concepts and how they apply to real-world problemsUseful tips and tools you can take back to the front-lines to help you mobilize hearts and minds for our collective liberation!What are we making?

Generations of wisdom from social movements around the world…and with that we’re going to make an 7-episode podcast that include:Heartbreaking and hilarious testimonials from guest activists, organizers and educatorsAccessible, witty and informative explanations of key concepts and how they apply to real-world problemsUseful tips and tools you can take back to the front-lines to help you mobilize hearts and minds for our collective liberation!What are we making?We’re going to make a podcast and toolkit about the stuff the left doesn’t like to think about or wishes it could do better.

The Podcast

The PodcastWe are going to make a 7-episode, fun, funny and insightful podcast about why the activists, organizers and educators need to rethink how to persuade, influence and transform. It’s going to be a joy to listen to.

Each episode of the podcast will have the following format:

A special guest will “call in” to tell us about a challenge they are facing changing hearts and minds in their struggles.Max and Sarah will stage a feisty but comradely debate on how to respond to that challenge, calling experts to make the case. A jury we will assemble of three wise movement veterans will pass judgment, with colourful commentary. The Toolkit

The ToolkitThen, based on the themes of the podcast, we will also prepare a concise online toolkit, aimed at giving organizers, activists and other malcontents tools for workshops or follow-up. Materials in the toolkit will include:

Case studiesReading and resource listsCreative exercises and gamesTips, tricks and techniquesInfographics, comics, creative writing and more Don’t want to donate? Sign up for (infrequent) email updates here

Don’t want to donate? Sign up for (infrequent) email updates here

We’re two charming radical nerds obsessed with imagination and cognitive dissonance. We’re both seasoned educators and activists.

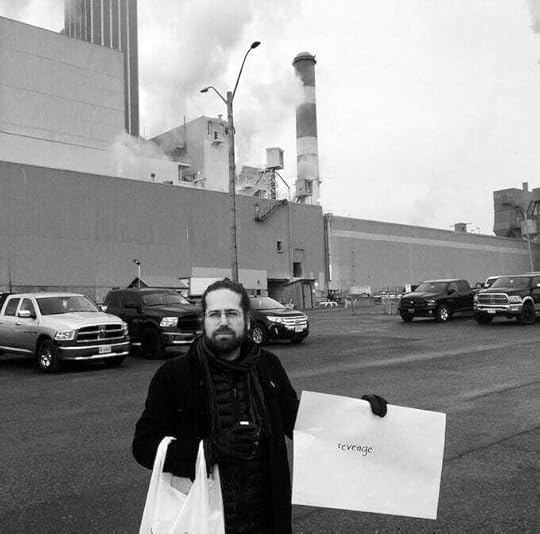

Max HaivenMax has been organizing grassroots movements since he was 12 in anti-capitalist and anti-colonial initiatives. Today works as the Canada Research Chair in the Radical Imagination at Lakehead University and directs RiVAL: The ReImagining Value Action Lab, a platform to bring together social movements and radical ideas. He is the author or editor of 9 books which all focus on the relationship between capitalism and the imagination. Along with Alex Khasnabish, he is the author of The Radical Imagination: Social Movement Research in the Age of Austerity (2014) and is currently working on a book titled The Player and the Played: How Financialization Fosters Fascism. He organizes with the Common Ecologies social movement education project and Berlin Versus Amazon. He also makes board games and podcasts.

Max, with a wholesome message in his natural habitatSarah Stein Lubrano

Max, with a wholesome message in his natural habitatSarah Stein LubranoSarah has been organizing since she was 18, when her college feminist group ran Female Orgasm Day. In the pandemic, she coordinated mutual aid for her ward in London. She is also the Head of Research at the Future Narratives Lab, where she strategises about how to talk about social problems. She’s just finishing a PhD at Oxford in Political Theory, and her research focuses on cognitive dissonance and how it can help explain the gaps in people’s political consciousness. She has a book coming out about why talking about politics is often so ineffective, which will be released by a major publishing house in 2025. She’s been on a lot of other people’s podcasts, including Derren Brown’s audible series, The BBC’s Moral Maze, and Women’s Hour. She frequently speaks to the public.

Sarah, preparing to spill the tea with youThe back story: Mobilizing Hearts and Minds

Sarah, preparing to spill the tea with youThe back story: Mobilizing Hearts and MindsIn the fall of 2023, we hosted a free 12-week online workshop for 25 activists, organizers and educators on the topic “Mobilizing Hearts and Minds: The Arts and Infrastructures of Persuasion.” Based on its huge success, and our new skills at sassy banter, we want to turn what we’ve learned into a podcast and toolkit.

Here’s what some of our participants had to say about our course:

My course with Sarah and Max helped me to become more targeted and effective in my work… I’d recommend it to any activist or visionary; it is the perfect space for imagining alternative futures and considering practical strategies to bring about tangible change in the world.

~ Amelia, doctor and activist, UK

This course has honestly changed my life. Not only has it… given me a sense of how I can mobilise hearts and minds more effectively, given me permission to be pragmatic rather than idealistic or rigid, given me a set of concrete strategies… but it’s also transformed my instinctive relationship to other people… it’s given me so much more hope and optimism.

~ Dr Noreen Masud, Lecturer in Twentieth Century Literature at the University of Bristol, and an AHRC/BBC New Generation Thinker, UK

Max and Sarah’s entertaining style made it much easier to address very complex topics, and the diversity of participants made the exchange very enriching. I would definitely take it again without a doubt.

~ Daniela, activist in culture and feminism, Mexico

Learn more and donate!Who is this podcast for?To be honest, this course taught me more about how to achieve positive social change than any I’ve had in school. The creative exercises, the entertaining and enlightening course material, the wonderful activists of all kinds that I met through the course, it all replenished my faltering hope and gave me back my enthusiasm for the work that has to be done to build better worlds!

~ Melike, economic sociologist, Berlin

THE ACTIVISTS AND ORGANIZERS: In-the-trenches activists and advocates, keen to learn what works to change people’s hearts and minds towards our collective liberation from economic, racial, social and ecological injustice!

THE ACTIVISTS AND ORGANIZERS: In-the-trenches activists and advocates, keen to learn what works to change people’s hearts and minds towards our collective liberation from economic, racial, social and ecological injustice! THE EDUCATORS: People dedicated to helping other people of all ages expand their hearts and minds.

THE EDUCATORS: People dedicated to helping other people of all ages expand their hearts and minds. THE SECRET AGENTS: The patient, hard-working folks, the quiet forces for change, the policy wonks, all working in public institutions, NGOs, companies and other places who want techniques and courage to push for change in the belly of the beast.How and when?

THE SECRET AGENTS: The patient, hard-working folks, the quiet forces for change, the policy wonks, all working in public institutions, NGOs, companies and other places who want techniques and courage to push for change in the belly of the beast.How and when?

We plan to release our podcast and associated toolkit in May/June 2024. Here’s the plan:

December 2023-January 2023: fundraising and pre-production (booking guests; hiring a producer; getting our ducks in a row)February-March 2024: script-writing, show production and interviews (sleepless nights; explosive “creative differences” over theme music, etc.)April 2024: editing, building our website, getting ready for the podcast release (stalking left celebrities for endorsements and mentions; May-June 2024: weekly episode release as well as toolkit launch (getting drunk on newfound celebrity; being brought back to our senses by our long-suffering friends)Learn more and donate!What’s needed?Our project has already secured funding from RiVAL: The ReImagining Value Action Lab that will pay for:

Max’s timeA bit of Sarah’s timeOur website and toolkitThe assistance of researchers and a part-time producerWe’re looking to our communities for support for:

The rest of Sarah’s timeThe services of a professional sound editor!A graphic designer for the podcast, website and toolkitPaying small honouraria to our guests, experts and juryHiring a producer to help us coordinateIf our community is extra generous we aim to:

Pay our guests, experts and jury, all of whom deserve it!Upgrading our production team to make things run more smoothly and sound more professionalPaying for advertising and promotions to help the project reach the people who need it!Learn more and donate!Potential episode topicsHere are the topics, very roughly, that we intend to cover in the podcast. We know people are asking these questions so we are going to hear from people who are facing them directly then try to answer them. And hey, if that’s you, please reach out!

Should activism feel good?Why is trying to change things so hard? Should it feel easier?

(Plus: tips on surviving a horrible meeting and putting up with annoying coalition partners)Are people deluded or apathetic?

Why don’t people get it? Or is it that they don’t care?

(Plus: did somebody say “false consciousness”?)What’s the use of shame?

We’ve all had embarrassing moments, but (when) can they be transformation?

(Plus: we have a call-in show about calling-out, and in…)Are we gonna have to actually talk to people?

Is persuasion part of our job on the left? How do we do it?

(Plus: we address the fantasy of violence on the left)What can we learn from conspiracy theories or a cult?

All the worst people seem great at convincing others. What can we learn from them?

(Plus: tackling loneliness and building “social infrastructure!”)Why are we activists especially annoying?

Maybe activism is hard because the people who do it are…weird.

(Plus: betrayal, division, and other pathologies of the left)Do we just need a strong leader?

Maybe we all secretly crave one? Plus: must we abandon horizontalism?

(Plus: the fall out from the Occupy movement…)Should we abandon hope?

Should we feel hopeful or hopeless? Is despair or hope the right approach?

(Plus: cruel optimism, unruly desire, and more).

The post Help us fund WHAT DO WE WANT? A podcast about changing hearts and minds… appeared first on Max Haiven.

October 24, 2023

10 Years of the Radical Imagination podcast mini-series

Ten years ago, Alex Khansnabish and I were putting the finishing touches on a book that would, in 2014, but published by the venerable Zed Books as The Radical Imagination: Social Movement Research in the Age of Austerity.

The Radical Imagination

The Radical Imagination2014

It was based on four years of ethnographic research with social movements “dwelling between success and failure” in Halifax, Canada and put forward what was then a few key original arguments.

First, that the radical imaginations was not something that individuals possess, but something that people do together, and that sparks in the darkness as they struggle against the powers that be.

Second, that beyond simply reporting on social movements or lending them their time, militant researchers working in alignment with social movements can play the unique role of “convoking” the radical imagination: helping to foster the conditions where it can spark and ignite.

Excerpts from the book:

“Why social movements need the radical imagination” in Open Democracy“Fomenting the radical imagination with movements” in ROAR MagazineOver the last decade, we’ve been extremely gratified to hear from and learn of many movement researchers who have found the book helpful and it continues to be widely cited, although often with a frustrating lack of attention to its actual arguments. Unfortunately, the radical imagination has also become a bit of an academic buzzword and often, frankly, an alibi for researchers not to take a stand. Too many writers who are just gesture to the radical imagination in a vague way as the thing that’s supposed to save us. But the book makes clear: we need to be more rigorous in our concepts and dedicated in our struggles.

In any case, as we approached the decade mark, Alex and I were pleased to collaborate with Cited Media and their flagship podcast, Darts and Letters, to produce a set of pieces to reflect backwards and forwards on the radical imagination. We were supported by the Social Sciences a Humanities Research Council of Canada.

We can begin with this 1h extended interview Gordon Katic of Darts and Letters conducted with Alex and I reflecting on The Radical Imagination a decade on, with particular attention to if we can say the reactionary right also exhibits some kind of “radical imagination.” That interview is hosted by the New Books Network.

Alex and I also supported Gordon and his team to produce a three-episode mini-series of Darts and Letters on the radical imagination now.

The first episode focused on the crisis of masculinity and the success of the far right in recruiting disaffected young men. It featured Annie Kelly of the podcast QAnon Anonymous and its mini-series MANCLAN; streaming sensation VAush, and journalism professor Nicholas Lemann.

The second episode focused on the strange story of how the conspiracist right appropriated anti-corporate rhetoric from the radical left. This episode featured interviews with author and activist Raj Patel; filmmaker and law professor Joel Bakan, director of The Corporation and its recent sequel; and several Swiss organizers against the World Economic Forum.

The final episode explores anti-authoritarian, autonomist and anarchist perspectives in a moment when we are increasingly told only the state can solve our problems. It features conversations with Elif Genc about the influence of anarchist thinker Murray Bookchin’s ideas on the Kurdish feminist struggle; with documentary filmmaker Marc Appolonio about mutual aid struggles accross Turtle Island; and with Alex and I on The Radical Imagination.

And there is even more content, including extended interviews with various guests, on the Darts and Letters YouTube page.

The post 10 Years of the Radical Imagination podcast mini-series appeared first on Max Haiven.

September 26, 2023

Why play games with conspiracies? (ephemera)

The following essay will appear in the journal ephemera in a special issue dedicated to games, accompanied by a print-at-home edition of CLUE-ANON, the game therein described. It emerges from the Conspiracy Games and Countergames project I have pursued with Aris Komporozos-Athanasiou and A.T. Kingsmith.

Why play games with conspiracies? A reflection on the board game CLUE-ANONMax HaivenCLUE-ANON is a board game of deduction and bluffing for 3-to-4 players that fosters a fun, generative environment to discuss why conspiracy theories are so appealing…and so dangerous. It borrows its name and theme not only from the popular commercial murder-mystery board game Clue (marketed as Cluedo in some countries), but also from the wildly popular Q-Anon ‘conspiracy fantasy’, which holds that there is a secret war against a vast global conspiracy of powerful elites and celebrities who are controlling governments in order to kidnap and abuse children.

I developed the game as part of the Conspiracy Games and Countergames project, which I led along with Aris Komporozos-Athanasiou and A.T. Kingsmith, who also offered invaluable feedback and ideas for the game’s development. The motivation to create the game stemmed from students explaining to us that they dreaded returning home at holidays to family members deeply and belligerently enthralled to the reactionary conspiracy fantasy. Indeed, a number of critics have likened Q-Anon to a massive, addictive, participatory ‘alternate reality’ game, with very real consequences, including being a major driver of the storming of the US Capitol on 6 January 2021. We wondered: could we craft a game our students could take home to catalyze critical conversations about how ‘viral’ conspiracy fantasies form? And might it in any way help by capturing or redirecting some of the ludic energy or impulses that otherwise find such problematic expression in reactionary conspiracism?

In CLUE-ANON, players role-play as actors and influencers in the conspiracy media sphere. The game is played across two or three ‘matches’, each of which revolves around a different conventional American conspiracy scenario: who faked the moon landing? Who assassinated the beloved politician? Who rigged the important election? Who unleashed the global pandemic?

At its most basic level, the game is simply one of deduction: there are nine possible ‘suspects’, represented on cards (the Deep State, Space Aliens, an Evil Corporation, Satanists, the Mainstream Media, Foreign Spies, a Secret Society, the Military Industrial Complex, and Paid Protesters). Of these nine suspects, the three ‘real conspirators’ are placed under the board until the end of the match. The remaining six are arranged, face-down, on the board. Players have six turns to pay in-game resources (money and followers) to privately look at those six face-down cards in order to try and deduce the three hidden ‘real conspirators’ and solve the conspiracy.

But wait, here is where things get interesting, in two ways. First, it’s impossible to get enough resources in six turns to look at all six suspect cards…unless one bluffs! Players can gain more money and more followers if they publicly announce they believe one or more of the suspects is involved in the conspiracy, even if they have little or no evidence on which to base this accusation. This, of course, is a parody of our sad reality, where the proponents of bogus, premature, and unsubstantiated conspiracy theories are often richly rewarded in a highly monetized social media landscape. But after six turns the real conspirators are revealed, and players with incorrect accusations on the table might lose points, so they must balance their strategy.

And here’s the real twist: a successful player’s strategy will be influenced by the character they have been randomly assigned at the start of the game and that they keep secret until the very end, after all the conspiracies have been explored. While almost all the characters gain points for correctly guessing the three real-conspirators, each character also has a powerful end-of-game bonus that has a large impact on who wins or loses. The Independent Journalist gains extra points if their opponents also guess correctly, encouraging them to help their adversaries. But all players have an incentive to pretend to be the journalist. For example, the Troll Army gains points if they can misdirect their opponents and cause them to guess incorrectly. The Social Media Corporation gets a big bonus for accumulating money. The True Believers get a bonus for gaining as many followers as possible. The State Agent gains when everyone is so distracted by lies the real conspirators get away with it. At the very end of the game, after all the conspiracies are solved, all players can try and guess one another’s characters for extra points, and so there is an incentive to keep one’s character somewhat secret, even while seeking to maximize its scoring bonus.

In the rest of this paper, I will reflect on some of the motivations and influences for developing CLUE-ANON with special attention to the potential of games as research tools and the their particular usefulness for exploring conspiracism and other disturbing phenomena in an age characterized by the disenchantment of digital capitalism.

Games as research toolsThe Conspiracy Games and Countergames (CGCG) project, of which CLUE-ANON is a part, also included a research podcast and collaborative writing activities. That project evolved in 2021 out of a previous set of inquiries into the nature of the phenomenon of ‘anxiety’ under digital capitalism (see Haiven and Komporozos-Athanasiou, 2022). We began from the idea that, sociologically speaking, conspiracism is a response to capitalist anxieties. But neither anxiety nor conspiracism are inherently pathological: there is plenty to be anxious about in digital capitalism, and real conspiracies are a crucial part of its political economy (Haiven, Kingsmith and Komporozos-Athanasiou, 2022). Further, both the category of ‘anxiety’ and of ‘conspiracism’, while they seek to identify real phenomena, are themselves socially constructed and shaped by the power relations and force fields of digital capitalism, and therefore require reflexive scrutiny (Kingsmith, 2023).

None of the three researchers involved in the project had any prior expertise in conspiracies and conspiracism: I am a cultural theorist of social movements and financialization; Komporozos-Athanasiou is a social theorist who shares with me a specialization in finance and the imagination; and Kingsmith’s dissertation concerns the politics of anxiety and mental health. The CGCG project is part of a wider set of efforts to embrace the insights that come from being a scholarly neophyte, and to make that learning public. For example, we used the project’s interview-driven podcast as a way to learn together, making the vulnerable process of discovery accessible to a wider audience of other scholars as well as artists, activists, and community-members. We triangulated a topic (conspiracies, games, and digital capitalism) and, through our research, found and reached out to diverse guests who we felt might have something to say about two or more of its elements.

CLUE-ANON was also part of this process. When we began our collaboration, I proposed to my colleagues developing a board game whose objective would not simply be to gamify our research conclusions as a means to publicize our conclusions but, rather, to be a reflexive research tool. I wanted to explore how making a game could be part of the research process, rather than an outcome of it. I didn’t simply want the game to communicate our theories and findings; I wanted to see if the process of developing and refining the game could be part of the way we did research, and a way to include others in it. Even more particularly, I wanted to see if such a game could not simply to measure the responses of players (we have never used CLUE-ANON to gather data) but, rather, as a catalyst for conversations that might inform the process of scholarly theorization.

Of course, the use of games as a pedagogical platform is ancient, and the development of ‘serious games’ for the purposes of enhancing military or business strategy, or educational outcomes, fosters a large international industry (see Michael and Chen, 2006). The design of the smaller subset of serious games known as ‘social impact games’, which strive to address injustices or power imbalances in society, requires the designer to distill the relevant sociological information and model down to its more basic elements before operationalizing them (Flanagan, 2009). It’s one (relatively easy) thing to simply layer a thematic ‘skin’ on an existing or even a new game – for example, modifying the graphic design and narrative elements of a well-known game like Monopoly to gesture towards a process like contemporary gentrification. Without disparaging that approach, I have found it more rewarding to try and develop a game from the ground up that explores a social and political topic through the game’s ‘procedural rhetoric’: the game should ‘teach’ the player through the way it invites them to develop their own strategies, beyond the particular graphical and narrative trappings (Bogost, 2010). In CLUE-ANON, players teach themselves to balance the requirements of discovery and deception based on the particular bonuses of their character. They learn, in playing, the seductive exhilaration of conspiracism.

In some sense, I am curious about the way that a game might excite what C. Wright Mills (2000) called ‘the sociological imagination’: the ability to reckon with the dialectic relation between the individual and society, to see how social forces articulate and are articulated by people, bridging the gap between history and biography. There is something unique about the way games (particularly tabletop games) place players in an artificial hiatus, or liminal space, between structure and agency, which I think is particularly well-suited to awakening this kind of imagination (Nguyen, 2019). To this extent, I think that some games can encourage what I might call a proto-theoretical approach. By encouraging players to think in complex, multi-directional, even contradictory ways, to think metaphorically about society, and to think about agency, it might set the stage for them to then do the work of theorizing their society anew. Such a process would be ideological in the counter-hegemonic sense: it might contribute to empowering players to think beyond dominant and conventional explanations for social phenomena and, instead, produce a new cognitive map. Elsewhere, I have written with Alex Khasnabish about the opportunities critical scholars might embrace to ‘convoke’ the radical imagination. Here, convocation names an interventionist research strategy that aims to bring people together to explore how the world could be different and ponder what prevents or might enable change (Haiven and Khasnabish, 2014). Games, I think, can be part of this process. This conviction is fortified by the theories of Hans-Georg Gadamer (1986), Johann Huizinga (1971), Roger Caillois (1961), David Graeber (2014), and others, for whom play is a central dimension of human experience, creativity and politics.

The value of broken gamesSo CLUE-ANON represented, in a sense, a research tool: a supplement to the process of systematic thinking. Since I first developed the game, I have substantively revised it over 15 times based on feedback and information I gained while playtesting it with the assistance of my colleagues A.T. Kingsmith and Aris Komporozos-Athanasiou. Through that iterative process, I have learned a great deal not only about the game in particular and game design in general, but also about the triangulated theme of conspiracism, gamification, and digital capitalism that we three set out to explore. I have also learned a great deal about this theme through my conversations with players after the game, where, typically, they reflect on both the game itself and the sociopolitical theme.

In particular, I have found it helpful to ask players: ‘how could this game be more realistic?’. As a game, rather than a simulation, CLUE-ANON strives not only for some degree of sociological mimesis, but also to be fun. In the gap between what the game pretends to model (the mediascape of conspiracism) and the social reality of gameplay (typically wwith people who don’t consider themselves conspiracists, let alone influencers), a lot can be learned. It’s what we can learn from the dissonance that matters. When I ask the question, many interesting research questions naturally arise. Is CLUE-ANON a game only about American conspiracism, or to what extent can it map onto other, often quite different, contexts? The Independent Journalist is given a rather heroic role in the game, striving to get others to see the truth – but is that realistic or naïve (and what does ‘independent’ even mean)? Does the fact that there is a ‘real conspiracy’ to discover in the game imply that someone did actually fake the moon landing, or intentionally unleash the global pandemic, and with what consequences? Could the game accidentally encourage conspiracism, rather than warn against it? Do such warnings even work? Does the fact that the game includes implausible suspects (satanists, space aliens) make too much of a mockery of conspiracism, when in fact we know that conspiracies (in terms of powerful people working together in secret) do really exist and that supernatural conspiracy theories, while sensational, are relatively harmless compared to their political counterparts? Does the complexity of the game preclude it ever actually being a resource to dissuade would-be conspiracists from descending down the proverbial ‘rabbit hole’? And perhaps most importantly, does the game actually encourage critical thinking, and is that a sufficient end unto itself? Sufficient in what sense? Each question opens onto a profound question that goes well beyond the game itself and touches on topics including the allure and power of conspiracism, the promise and peril of games and gamification, and the sociology of ideology and belief.

It is these kinds of questions that the game, ultimately, aims to convoke. The game is unavoidably didactic in many ways, but ultimately in what I hope are generative ways: players are encouraged to explore and question their frustrations and misgivings. I have playtested the game dozens of times, at academic conferences, in university classrooms, with social justice activists, and at game cafes and other board game-focused spaces. It never fails to generate an interesting conversation, in part because it is slightly frustrating. CLUE-ANON is an imperfect game, made by an amateur designer without (as of yet) the support of a game company that might help improve its internal balancing mathematics, its graphic design, or its playability. It is not fluid or unfrustrating to play. It does not ‘accurately’ model or simulate the world of conspiracism; it is perhaps best seen as an ironic parody that inflates, embellishes, and renders fantastic some elements of conspiracy culture as a means to open the door for critique. But in some senses, the broken-ness of the game in several ways contributes to its usefulness. I often ask playtesters, ‘what would you do to fix this game?’ or ‘what would make for a better game on this theme?’, which invites them to enter into the very thought processes that led me to create it.

Creating CLUE-ANON has convinced me that creating and playing an imperfect game can be an important part of a creative, open-ended social research process, not simply because it offers an avenue to explore scholarly ideas, but also because it brings other people into the process.

Dangerous games and enchanted inquiryAs Komporozos-Athanasiou, Kingsmith, and I have written elsewhere, the CGCG project is motivated in part by a debate currently forming among scholars and commentators about the gamified elements of contemporary conspiracism (Haiven, Kingsmith, and Komporozos-Athanasiou, 2022). The emergence of the Q-Anon phenomenon led a number of game designers and scholars to remark on and explore the game-like qualities of the movement. In a widely cited Medium article published during the height of media attention towards Q-Anon, game designer Reed Berkowitz (2020) observed the way the conspiracy played on its adherents attraction to a collective process of discovery, similar to the mechanics he employed when making augmented reality games. While mainstream American conspiracy journalist Mike Rothschild (2022) largely dismissed the idea that Q-Anon is a huge, malevolent game, the 2021 HBO docu-series Q-Anon: Into the Storm explores the proposition in depth, even linking its emergence to key players in the augmented- and alternate-reality gaming world. In his exceptional exploration of Q-Anon, Wu Ming 1 (the pseudonym of a member of the left-wing Italian writing collective Wu Ming) also explores the game-like aspects of the conspiracy, although he is careful to link it to a much longer history of conspiracism as a kind of dangerous public play, with often terrifying consequences (Wu Ming 1, 2021; Wu Ming 1 et al., 2023). More recently, Hugh Davies (2022) has with greater rigor asked to what extent Q-Anon employs gamified elements.

We may never know the degree to which the Q-Anon conspiracy fantasy was intentionally concocted by far-right political actors, nor the extent to which they may have been inspired by games and game design. However, the associations certainly alert us to the continuity between games and participatory conspiracism, in which the absence (or enigmaticness) of a central authority allows followers/players to concoct their own endless role-playing scenario (Haiven, 2023). In the CGCG project we ask: if so much social imagination is being employed towards the perpetuation of such an ever-evolving collective fantasy, what otherwise unanswered social needs is it fulfilling for its adherents? And to what other ends might this imaginative surpluss be put (Komporozos-Athanasiou, 2022)? Is this energetic field one that can only produce a proverbial storm of destruction, such as the one unleashed on 6 January 2021 when Q-Anon devotees joined thousands of other far-right activists in a blundered coup attempt at the US Capitol? Or could these energies be generated and directed elsewhere?

Inspired by such a question, Komporozos-Athanasiou, Kingsmith, and I have proposed to explore what we are calling, tentatively, enchanted inquiry. Our approach takes as its Weberian starting point the idea that digital capitalism is profoundly disenchanting, in the sense that it compels most social actors to instrumentalize almost all aspects of their life as a means to leverage some measure of success or even stability in a chaotic neoliberalism-ravaged economy without any guarantees. To many, perhaps most, digital capitalism feels like an unwinnable game. While reason, science, and ‘progress’ may have once been seen as the keys to a better life, today many would entertain the notion that they have, in many ways, made the world worse. Of course, both right-wing and left-wing anti-modernism is nothing new, but its articulations in our times of triumphant global capitalism, rising ethno-nationalism and ubiquitous social media are profound. In such a circumstance, it is perhaps unsurprising that people across the political spectrum turn to fantasy and what we frame as tactics of collective re-enchantment.[1] Usually, these re-enchantments appear relatively harmless: the rise of computer and role-playing gaming, for example, or the turn (back) to horoscopes and astrology (see Komporozos-Athanasiou, 2022). But sometimes these forms of collective re-enchantment aim to assert their concocted alternate realities on the broader reality of which they are a part, sometimes violently. The editor of and contributors to the recently published collection Catastrophe Time! (Zhang, 2023) meditate on the weird and disturbing trends that emerge at the intersection of culture, politics and economics in a moment when financialization and the media and sociality it produces ruptures even the dominant capitalist cosmology that gave rise to financialization in the first place. In line with these observations, our conjecture is that games and gaming are important sites of re-enchantment and, even more importantly, they might offer critical scholars a key point of intervention beyond simply trying to distribute better information or offer more reliable analysis.

Many scholars and commentators across the political spectrum have called for a war on disenchantment. Stephen Pinker’s Enlightenment now (2018) is perhaps a singularly popular and cogent example of a genre of writing that insists we return to reason, rationality, evidence, and argumentation in the face of a rising tide of fantasy. Reactionary online celebrities like Ben Shapiro or Jordan Peterson have likewise branded themselves as the voices of reason and the paladins of the embattled Enlightenment. As scholars, we three collaborators at CGCG deeply and profoundly value many principles associated with the Enlightenment and reason, and have dedicated our careers to education based on these principles. However, we are skeptical of this strategy, even when proposed by figures we admire, like linguist and political theorist Noam Chomsky, whose dedication to disenchanted reason stems from his left-wing anarchist beliefs. We have revisited Horkheimer and Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment (1997), for example, to recall how these august virtues have, in the hands of instrumentalist modern regimes (both state-socialist and capitalist), been turned against human needs and used to perpetuate vast and irrational injustices. We also are inspired by several generations of feminist and anti-colonial thought which has demonstrated how the fetish of ‘reason’ and the reification of the Enlightenment worldview have long been instruments of patriarchy and a racial world system (Haraway, 1991; Mies and Shiva, 1993; Wynter and McKittrick, 2015).

Yet our curiosity is drawn towards what possibilities might exist for critical scholars to engage with the turn towards collective re-enchantment on its own grounds. CLUE-ANON is one tentative example. As a social board game, and especially one that requires role-playing, it is a tool of collective enchantment. Games, as Johan Huizinga (1971) famously theorized, create a temporary ‘magic circle’ within which a parallel reality is generated through consensual play. If that’s true, then perhaps we can think about games as mobile laboratories for exploring society, much in the same way physicists are able to – in miniature forms and for (relatively) tiny spans of time – generate antimatter and other theorized phenomena in a controlled laboratory environment. One element of such a process that appeals to me in particular is that it facilitates the collaboration of scholars and theorists with non-specialists. This opens the door to new, unanticipated insights at the same time as it can be a profound learning opportunity for all involved.

Unfortunately, most commentators intuitively believe that the most important element in the fight against the dangerous dimensions of collaborative re-enchantment (of which the Q-anon phenomenon is emblematic) is the debunking of false beliefs through sound argumentation (see Gilroy-Ware, 2020). The idea that conspiracists are self-involved, paranoid idiots is depressingly common, and profoundly wrong. Many people are attracted to conspiracism because it offers them a community of people who want to stand up to or at least understand the world of injustice and lies they find around them. Likewise, the idea that conspiracists simply parrot what they have read online is asinine. In fact, in most cases, conspiracists are highly creative (perhaps to a fault) and do exhaustive, often obsessive research. They are, for the most part, not hypo-critical thinkers by hyper-critical thinkers. While their procedures of that research and creativity can and should be critiqued, the impulse and the dedication are substantial. As Erica Lagalisse (2019) argues, if we are honest, the line between conspiracy theories and the critical theories in which readers of ephemera might trade is by no means clear, although the distinction perhaps begins with the way they respectively frame power as either biographical (this or that person or institution is acting in an evil way) or systemic.

I do not believe CLUE-ANON will convince a dedicated Q-Anon believer to abandon their fantasy. At best, it might help to redirect the urge towards re-enchantment in those not yet in the grips of such a fantasy. It aims to be part of channeling the sociological imagination towards more generative and critical forms of collective inquiry before it can be seduced by conspiracism. At a minimum, the game has been an important part of developing the theoretical paradigm that has informed our collective work in the CGCG project, and indeed this paper itself.

ReferencesAdorno, T.W. and Horkheimer, Max (1997) Dialectic of enlightenment. London and New Rok: Verso.

Berkowitz, R. (2020) ‘A game designer’s analysis of QAnon’, The CuriouserInstitute (Medium.com). [https://medium.com/curiouserinstitute...]

Bogost, I. (2010) Persuasive games: the expressive power of videogames. Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press.

Caillois, R. (1961) Man, Play, and Games. New York: Free Press.

Davies, H. (2022) ‘The Gamification of Conspiracy: QAnon as Alternate Reality Game’, Acta Ludologica, 5(1): 60–79.

Flanagan, M. (2009) Critical Play: Radical Game Design. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gadamer, H. (1986) The Relevance of the Beautiful and Other Essays. Translated by Robert Bernasconi. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gilroy-Ware, M. (2020) After the fact? the truth about fake news. London: Repeater.